High Illiteracy in the Developed World

At various times the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has surveyed thousands of adults across the world to assess their basic skills. Survey questions attempt to assess people’s ability to solve everyday ‘real world’ problems. In 2012 the basic numeracy question in Figure 5.1 was posed to 16–65-year-olds.1

While thinking about the answer, consider a much more surprising statistic. A quarter of British adults got the answer wrong. And the proportion answering incorrectly was the same for those aged under and over 30. (The answer, by the way, is 36 litres.) The same proportion failed the questions on basic literacy. The shocking results prompted the OECD to label British youngsters the ‘most illiterate in the developed world’.2

Mastering maths and English is the most basic requirement for prospering in life. People with improved literacy and numeracy skills are more likely to be employed.3 And in England, this link is particularly strong; not only this, people with stronger literacy and numeracy tend to be more healthy.4

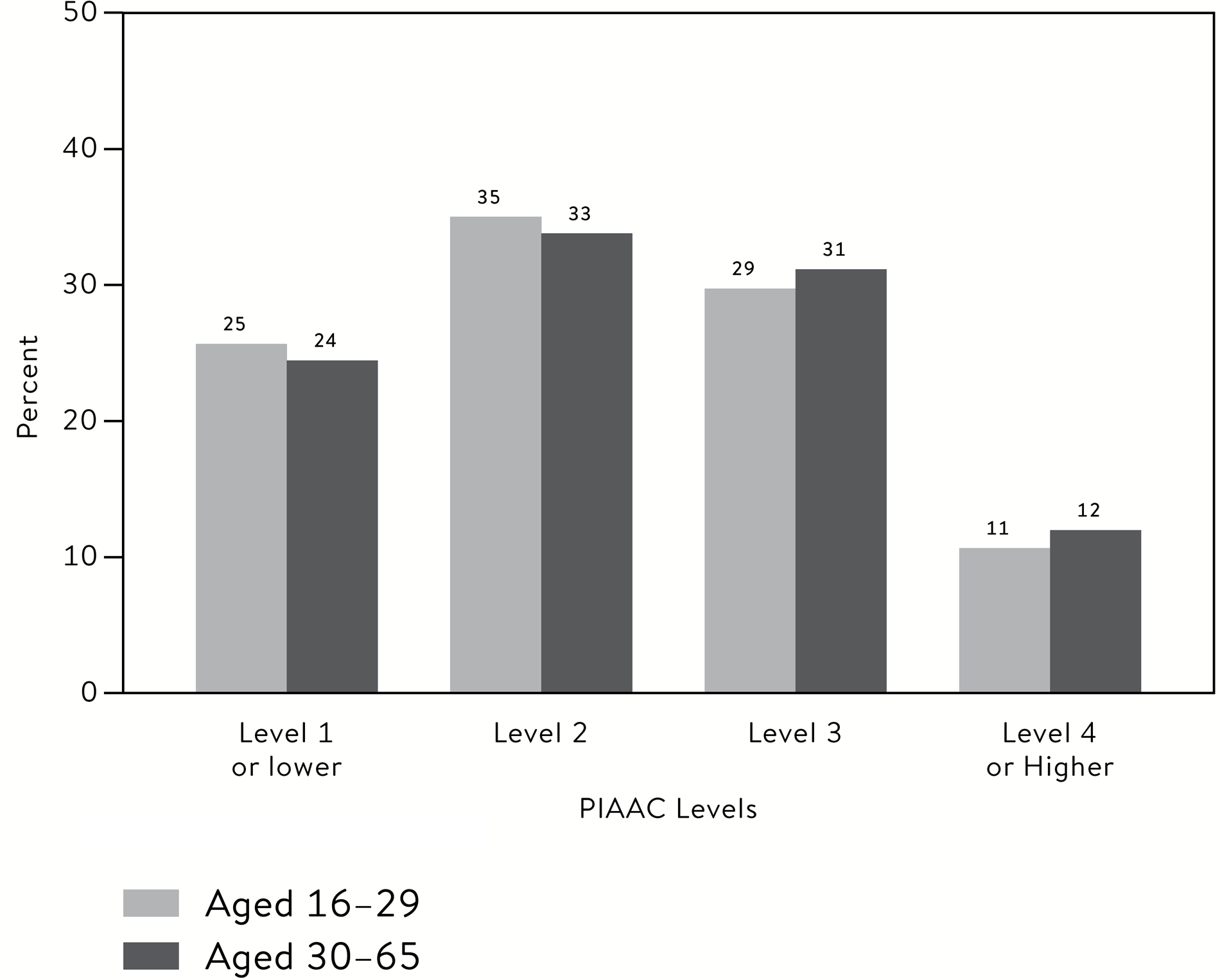

Our own analysis of the OECD data from its Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), an international survey of adult skills in twenty-four countries, is presented in Figure 5.2. Adults were assessed as having one of five proficiency levels in basic skills. People at Level 1 have low skills: they are unable to digest basic figures and words; they find it difficult understanding pay slips or household bills, or working out a household budget. People at Level 3 are secure in the skills that enable them to function perfectly well in everyday life – roughly equivalent to gaining good GCSEs or even A levels at secondary school.

Sample question in the OECD Basic Numeracy Test, 2012.

‘Look at the petrol gauge image. The petrol tank holds 48 litres. How many litres remain in the tank?’

A quarter of 16–65-year-olds in England were found to have substandard numeracy skills: they scored at Level 1 or below. Moreover – and unlike in other countries – the position was the same for 16–29 and 30–65-year-olds in 2012. This extrapolates to around 10 million unskilled adults across Britain. Separate Government surveys have confirmed these alarming patterns, finding the proportion of 16–18-year-olds without basic numeracy skills had gone up from 21 per cent in 2003 to 28 per cent in 2011.5

International Comparisons

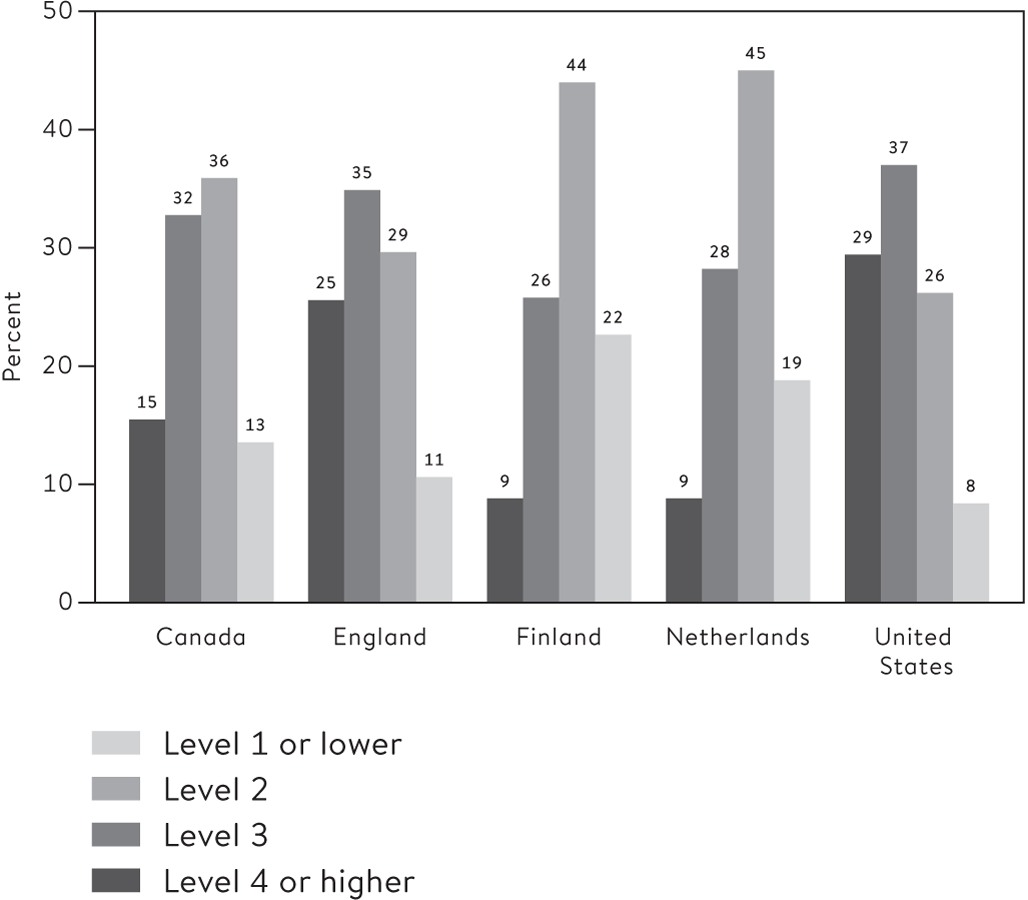

England’s rising illiteracy and innumeracy levels contrast with smaller and declining proportions of younger people with low skills in other countries (Canada, Finland, the Netherlands and the United States) as Figure 5.3 shows. Only the United States has a higher proportion of adults missing basic numeracy skills. Canada, which has high income mobility levels, lies in between the better performing Finland and the Netherlands and the worse performing England and United States.

Numeracy levels by age: England.6

Numeracy levels, 16-29-year-olds, by country.7

The message from these data is sobering. England is losing the international race in basic skills. The position is reasonably good at the top end of the skills distribution, but dire at the bottom. And the figures throw some doubt over the standards of our higher education system. Even one in ten university graduates were classified as having low skills. The OECD suggested the ‘priority of priorities’ for the country should be to improve the standard of basic schooling in England.8

Education’s Never-Ending Story

The summer riots in 2011 prompted much soul-searching among politicians in Britain.9 They tried to draw wider lessons from the sudden explosion of lawlessness that had seen gangs roam openly in inner cities, battling with an over-stretched police force. In the anxious weeks that followed, the Secretary of State for Education, Michael Gove, delivered a speech at the Durand Academy in Stockwell in South London. ‘For all the advances we have made, and are making in education, we still, every year allow thousands more children to join an educational underclass – they are the lost souls our school system has failed,’ he told an invited audience.10

Primary school teachers had spoken about the growing difficulty they faced with children who arrived unprepared to learn. A growing number of children were unable to form letters or even hold a pencil. Many could not sit and listen during lessons. Others could barely speak a full sentence of proper words, let alone frame a question.

When they arrived at secondary school these children were still unable to read or write, often covering up their deficiencies by acting tough and disrupting lessons. Many ended up being placed in ‘Alternative Provision’ or ‘Pupil Referral Units’. Despite the heroic efforts of teachers, the destiny of these pupils was all too predictable: they would become the next generation of street gangs and prison inmates. They faced a world of multidimensional poverty – ‘a poverty of ambition, a poverty of discipline, a poverty of soul’.

Durand was one of the new ‘academy’ schools that were the Coalition Government’s flagship policy.11 In Gove’s eyes it was exactly the type of school that would address low levels of literacy and numeracy. Yet within three years, Gove had been removed as Education Secretary.12 And in 2016 the Department for Education announced that it was withdrawing funds from the Durand Academy Trust following ‘serious concerns about financial management and governance’.13 Meanwhile another cohort of children would leave school lacking basic literacy and numeracy skills.

Ineffectual Education Reforms

The uncomfortable truth is that Gove’s ‘underclass’ of illiterate and innumerate pupils has remained immune to countless education reforms ushered in by successive governments. Policy has swung from market-based reforms to highly prescribed edicts on what teachers should do. School funding has been increased (and then cut). Targets have been set (and then re-cast). Commitments have been made (and then discarded). Yet the numbers of young people without the most basic skills remain as high as ever.

The 1988 Education Reform Act ushered in the publication of school league tables and school inspections, and a national curriculum. But for all these reforms, pupils in the bottom tenth of the class saw their grades deteriorate over the period.14

Before the 1997 general election, Tony Blair presented a sobering analysis of the performance of the country’s school system. ‘We have a major problem at the bottom’, he said.15 A blizzard of education initiatives followed, aiming to close the gap between poorer children and their more privileged peers, underpinned by a big increase in funding for schools.16 It signalled a sea change in education policy, combining market policies and state interventions – the so-called ‘third way’.

These policies ranged from help for schools in urban areas such as the London Challenge, to nationally prescribed ‘literacy hours’ and ‘numeracy hours’ for primary schools.17 Academies – schools independent of local authority control – were created to take over struggling schools.18 But by most measures there was only a tiny reduction in the overall attainment gap between the poorest pupils and other pupils during 1997–2010.19 In 2010 seven in every ten children (68.8 per cent) on free school meals failed to secure the national expectation of five grades of C or more, including English and maths, in their GCSEs at age 16.20 Labour’s record had been disappointing.21

The proportion of young people aged 16–18 who were not in education, employment and training (so-called NEETs) also failed to reduce under Labour’s watch, ‘indicating that a persistent minority of young people remained disaffected with school, achieving little and facing very poor post-school prospects’.22

Coalition Reforms

In 2010 it was the new Coalition Government’s turn to cite the country’s poor performance internationally.23 Its flagship social mobility policy was £2.5 billion of ‘Pupil Premium’ funds every year for children qualifying for free school meals.24 The Pupil Premium was one of a host of major changes. These included a new national curriculum, traditional end-of-year tests and more academies.25 Education policy would lurch back to the laissez-faire market policies of the 1980s.

Against this backdrop of change, a movement to introduce evidence-led practices emerged. The Sutton Trust published a ‘pupil premium toolkit’ to help schools spend funds on ‘best bets’ according to research on what had worked in the classroom.26 The Education Endowment Foundation was established to evaluate effective approaches for improving the results of the poorest pupils.27

But the achievement gap between poorer children and their better-off peers was wider than previously assumed. Driven by the pressure to rank highly in published league tables, schools had encouraged their poorest pupils to take vocational qualifications of dubious quality. This helped to boost the standing of a school, since these qualifications enabled them to record more pupils reaching expected benchmarks. Yet the truth was that most of the qualifications had little benefit for the children themselves.28 In 2014 teenagers on free school meals fell further behind their more privileged peers. Two-thirds failed to achieve five GCSEs with at least C grades including English and maths.29

Reviews of progress on narrowing the gap have adopted an increasingly despairing tone. One report concluded there was ‘currently no prospect’ of the gap being eliminated at secondary school – despite billions of pounds being targeted on the poorest pupils.30 Another estimated that, based on the most optimistic assumptions, it would take another fifty years to reach an equitable school system.31

Basic Skill Gaps

In 2011 a Government report laid bare the extent of the basic skills problem facing the country. The Wolf review, commissioned to overhaul vocational qualifications, found that obtaining at least a grade C in English and Maths GCSEs had become the new universal entry requirement for employers, sixth-form colleges and universities. Just short of half of all students had failed to achieve a C grade in GCSE in English or maths by age 16; at age 18 the figure was still below 50 per cent. Over 300,000 pupils had failed to master the basics in maths or English. ‘These are shocking figures,’ said Alison Wolf, an economist from King’s College London.32

Teenagers were forced to do re-sits in English and maths – many in poorly funded further education colleges. But in 2016 only 29.5 per cent of 17-year-olds (and older) subsequently achieved their grade C in maths; and 26.9 per cent in English.33 The majority of students failing to make the mark yet again were doubtless the same illiterates and innumerates highlighted by the OECD.

To understand how a 16- or 17-year-old can leave education without basic skills, you need look no further than a school register detailing the tough lives of their most troubled pupils. These are deeply harrowing tales involving years of instability, abuse and violence at home as young children. Multiple dimensions of disadvantage build up through the childhood years and have a cumulative impact, leaving few prospects of upward social mobility for these young people.

Their upbringing manifests itself in many ways. If they do attend school, they are unable to control their emotions, with frequent outbursts of anger. They are prone to impulsive behaviour and low moods, and have few friends. Often they are moved from one school to the next. They are at risk of drug addiction and involvement in gangs.34

These testimonies tally with the characteristics revealed from surveys of adult skills. Unskilled adults have relatively poor physical health and mental wellbeing; and they are more likely to receive state benefits.35 They made up half of the 2 million people unemployed in England in 2012.36

The Problem That Can Only Get Worse

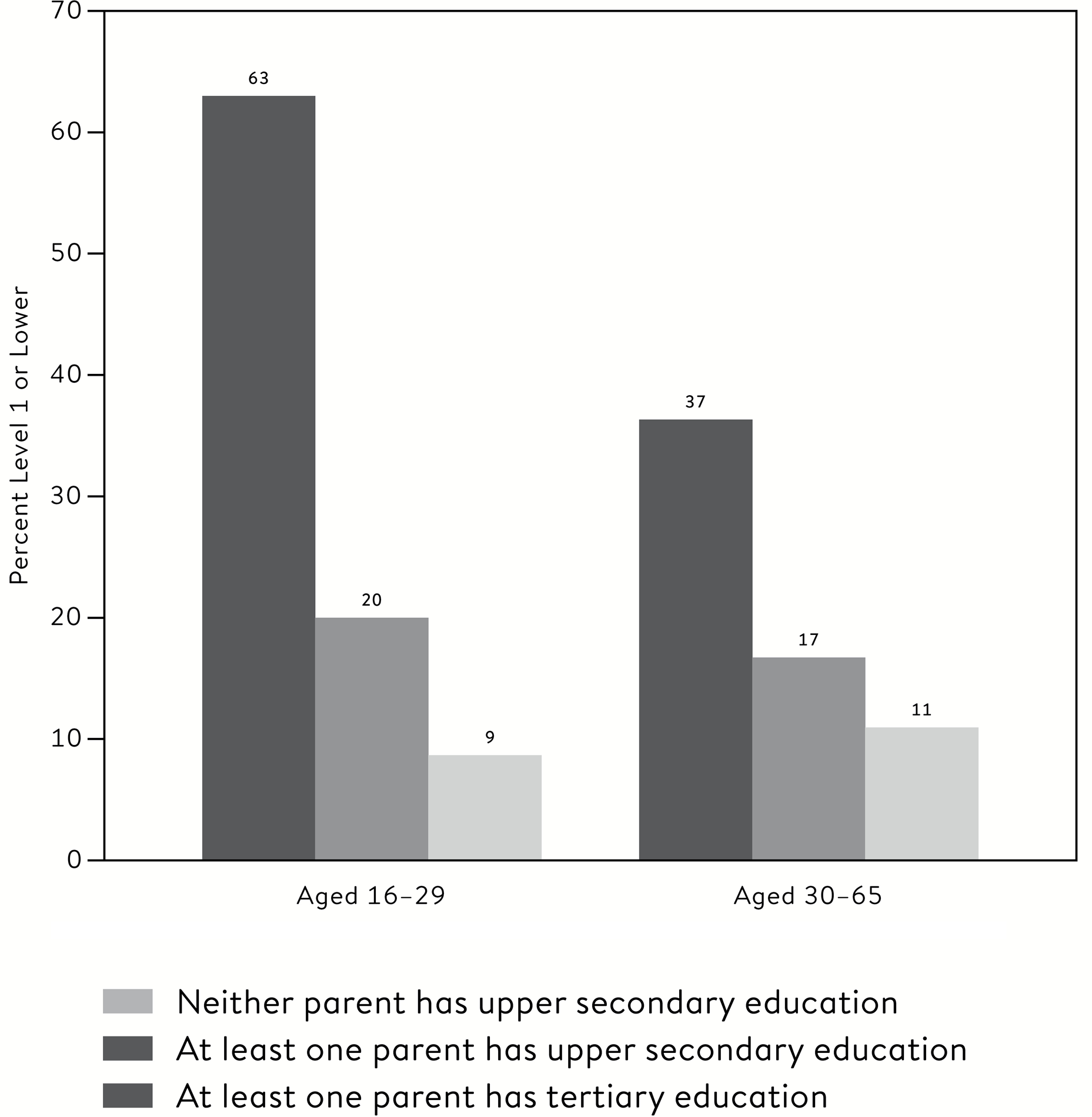

The problem of the low-skilled losers of the education system is set to magnify for future generations. The crippling disability of low skills is passed down from one generation to the next. Our own analysis of the OECD data is summarized in Figure 5.4, showing the proportion of adults with low numeracy skills for the under- and over-30s in England, but now broken down by their parents’ education levels. Over 60 per cent of the under-30s whose parents had failed to gain secondary school qualifications (admittedly by 2012 a relatively small fraction) had lower numeracy skills. This contrasts with the 9 per cent of the same age group who had at least one graduate parent. The intergenerational persistence of substandard education and skills is much stronger for the under-thirties than for the over-thirties.

Numeracy Level 1 or lower in England, by age and parental education.37

These results chime with many others. The link between parental background and adult skills among 16- to 24-year-olds was found to be stronger in England than in all other countries except the Slovak Republic.38 Meanwhile children whose parents had the poorest numeracy skills were twice as likely to perform poorly in a number skills assessment.39 Parents with low skills are more likely to produce offspring who will leave the education system with poor qualifications. Poor education begets poor education. The failure of the education system to address low skills just stores up a bigger problem for future generations.

Costs to the Nation

Gove’s education underclass seem destined to remain the school system’s forgotten children. The post-Brexit Referendum Conservative Government unveiled the creation of new grammar schools as its flagship education policy.40 Whatever the arguments over grammars, no one would claim they are the vehicle to address the country’s basic skills problem. New measures to judge schools meanwhile prompted concerns that children with the poorest exam prospects will be excluded from schools to maximize their headline test scores.41 And the National Audit Office warned that state schools faced the biggest real-terms cuts in a generation.42

Apart from the costs to individuals, the financial costs to the nation are substantial. The annual cost to the UK has been estimated to be around £20.2 billion, or about 1.3 per cent of the country’s GDP – a similar figure to that produced for the consequences of low-income mobility as a whole.43 This is likely to be an underestimate since the study considered only the impact of lower earnings and unemployment on individuals. Poor skills lead to poor health and higher criminality as well.

The most damaging penalty for failing to provide the education basics for 10 million people are the societal divisions this creates. The riots of 2011 were an explosion of the anger and resentment normally simmering just beneath the veneer of an ordered British society.44 Recent political voting patterns suggest a stronger disenfranchisement picking up steam.