David C: ‘It’s where you going to, not where you’re from that counts.’

David B: ‘I know that if I set my mind to do something, even if people are saying I can’t do it, I will achieve it.’

One David was born in a terraced house in East London, his father a kitchen fitter, his mother a hairdresser. The other David grew up in an idyllic village in the English countryside, his father a stockbroker (and the direct descendant of King William IV), his mother the daughter of a baronet. The first David left school at sixteen without any qualifications; the second studied at Eton and Oxford. One married an Essex girl. The other married the daughter of a wealthy aristocrat.

Both Davids have led successful lives and, in their own way, each highlights Britain’s social mobility problem.

David Beckham’s meteoric rise is a rare occurrence in modern Britain. Few children born to poor parents climb the income ladder all the way to the stratospheric heights of global stardom. A shockingly high number leave school without the basic literacy and numeracy skills needed to get on in life, and end up in the same poorly paid jobs as their fathers and mothers.

David Cameron continued a tradition that has seen successive generations of social elites retain their grip on the country’s most influential positions. Every prime minister since the end of the Second World War who has attended an English university has attended just one institution: Oxford. And Eton remains the exclusive breeding ground of Britain’s future elites. Cameron was berated by his own Education Secretary for surrounding himself at the heart of Government with a ‘preposterous’ number of fellow Old Etonians.1

Social mobility tells us how likely we are to climb up (or fall down) the economic or social ladder of life. And whilst some people are upwardly and downwardly mobile, too many of us are destined to end up on the same rungs occupied by our parents.

The tale of the two Davids can be used to illustrate the different ways of measuring social mobility. Each measure highlights a different way of benchmarking ‘success’ in life. Beckham’s rags-to-riches story is defined by how rich he has become compared with his parents. We call this ‘intergenerational income mobility’. Economists like to use income as a metric because it is a reliable way of comparing one generation’s status to the next, or of comparing one country’s mobility levels to another’s. A pound is a pound, and a dollar is a dollar, even if its purchasing power changes over time. They talk in terms of ‘intergenerational income persistence’, the opposite of mobility: it tells us how the incomes of families persist from one generation to the next.

Sticky Ends: The Deepening U-curve

Figures we have compiled reveal that the low levels of income mobility in Britain are due to a stickiness, or immobility, at the bottom and top of the income spectrum. Children born into the highest-earning families are most likely themselves in later life to be among the highest earners; at the other end of the scale children from the lowest-earning families are likely to mirror their forebears as low-earning adults.

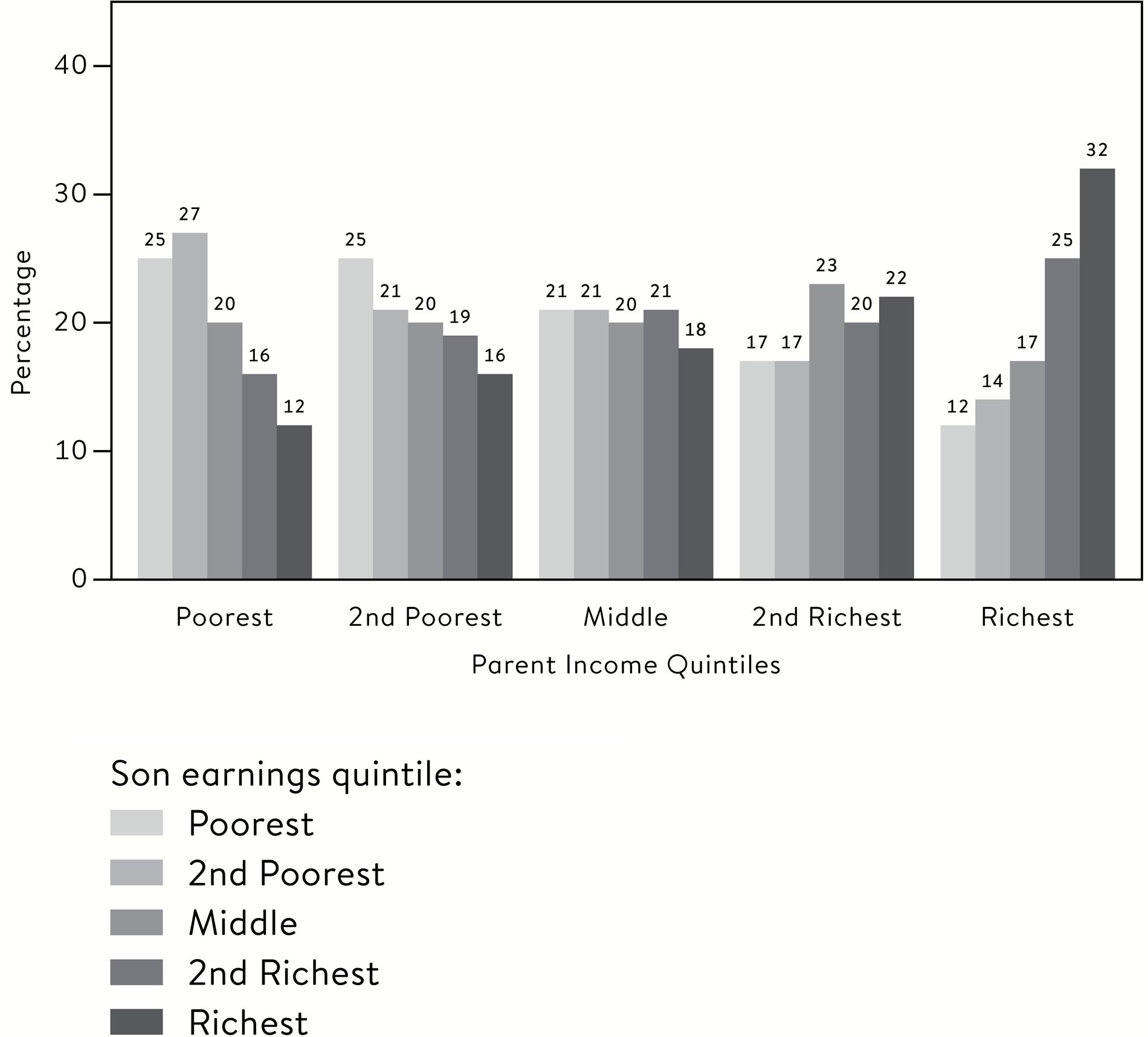

The U-shaped curves in Figures 0.1 and 0.2 show how this stickiness for the richest and poorest in society has increased over recent generations. They are generated using data for children and adults grouped into five earnings categories, from poorest to richest.2 The first graph charts trends from the National Child Development Study, which follows the lives of people born in Britain in one week in March 1958.3

If there was complete mobility, the chart would be a flat line; every bar would be at 20 per cent, reflecting an equal chance of ending up in one of the five quintiles. But there is instead a shallow U-shaped curve. A quarter of the sons from the fifth poorest homes remained in the poorest fifth of incomes as adults. And 32 per cent of children born into the richest top fifth of homes stayed among the richest homes when they grew up.

The second graph reveals a deeper U-shaped curve describing the mobility of the generation born in 1970. Over a third (35 per cent) of the sons born in 1970 from the fifth poorest homes remained in the poorest fifth of incomes as adults. Meanwhile 41 per cent of children born into the richest top fifth of homes stayed among the richest homes as adults. In just one decade, Britain had become less mobile.

Beckham is the exception to the rule – in a generation of lower social mobility. His annual earnings make him one of the most mobile people in Britain.4 He is paid millions of pounds, hundreds of times more than the money made by his father. Born in 1975, Beckham is five years younger than the generation tracked in the 1970 cohort study. But it is fair to say that he would be one of the few leaping from the lowest quintile to the highest quintile if a similar graph could be compiled for his 1975 cohort.7

Intergenerational mobility in the 1958 birth cohort.5

Intergenerational mobility in the 1970 birth cohort.6

David Cameron meanwhile was, in pure income terms at least, a downwardly mobile prime minister. Born in 1966, he is four years older than the cohort summarized above. Earning around £150,000 a year by the time he left office, Cameron would rank comfortably among the top fifth of earners if he featured in these charts. But he was earning far less than his father, who as a successful stockbroker made millions.

The global Beckham brand highlights the huge financial rewards that can be generated in a world economy without national boundaries. But globalization and rapid technological change have created bigger gaps between society’s winners and losers. The middle stem of Britain’s hourglass economy is disappearing. Britain’s rich have been enriched by economic growth. Britain’s poor have inherited greater job insecurity and poorer pay.

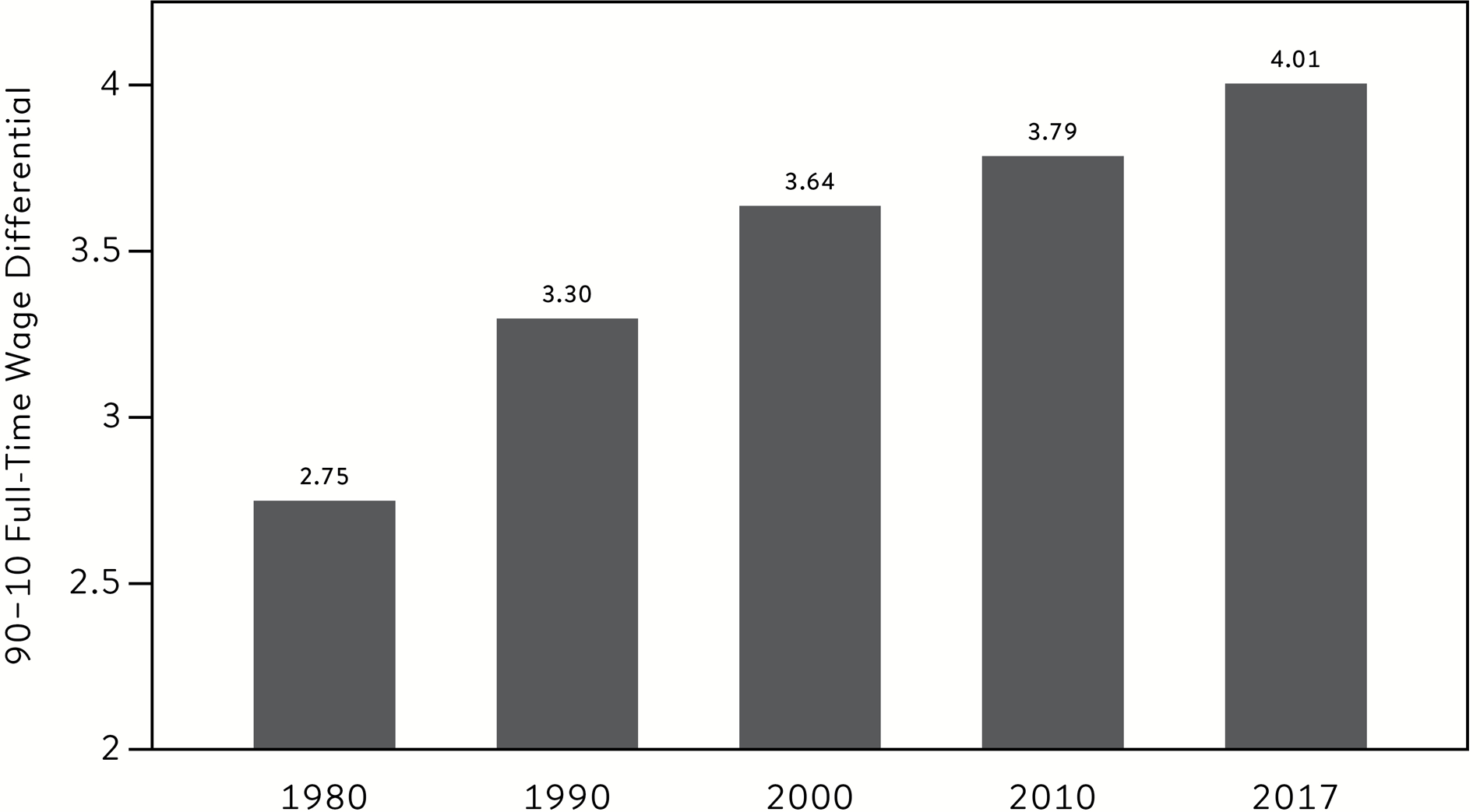

Our analysis confirms that inequality in Britain has widened as income mobility has fallen. The gap between the high- and low-paid can be measured by the ‘90:10 earnings ratio’. If the working population is arranged on a ladder with ten rungs, this ratio compares the earnings of those 10 per cent from the top with those 10 per cent from the bottom.8 It is, broadly speaking, the ratio of what professionals like doctors and lawyers get paid compared with what cleaners and fast-food workers earn. The rungs of the earnings ladder have got wider, as Figure 0.3 shows. In 1980 the worker from the top 10 per cent was earning 2.75 times more than the worker 10 per cent from the bottom. By 2017 the difference was 4 times.

90-10 wage differentials, 1980 to 2017.9

It is not just earnings but total wealth – including financial investments and housing – that sets the moneyed elite apart from the rest of us. Wealth inequality is on a different scale of magnitude to ‘bog standard’ earnings inequality. In 2017 the richest 1,000 people in Britain owned £658 billion – more than the combined wealth of the poorest 40 per cent of the population, made up of 10 million families.10 The broader wealth class is composed of one in ten families with houses and assets valued at over £1 million. At the bottom of the wealth spectrum, meanwhile, many people live with crippling debt.11 Our calculations show people on the top-tenth rung of the wealth ladder are over 80 times wealthier than those on the bottom-tenth rung.12

We are returning to an age where earnings from financial assets far exceed simple wages.13 One reason is that financial elites appear to live by different rules – paying minimal tax to maximize their fortunes. It does not help being in the public spotlight. Beckham was refused a knighthood because of the black mark he received for investing in a tax avoidance scheme.14 Cameron meanwhile was forced to admit that he had benefitted from an offshore trust established by his father to enable wealthy clients to escape paying tax.15

Extreme inequalities of wealth and income are inextricably linked with low income mobility. ‘You need some inequality to grow [economically],’ the economist Thomas Piketty has argued. ‘But extreme inequality is not only useless but can be harmful to [economic] growth because it reduces mobility and can lead to political capture of our democratic institutions.’16

We are still finding out how extreme inequality, particularly experienced in early life, leads to lower mobility throughout the life course. But one chief mechanism is through an increasingly inequitable education system. Far from acting as the great social leveller, education has been commandeered by the middle classes to retain their advantage from one generation to the next. Our social elites will go to ever greater lengths to ensure their offspring stay ahead.

Once again the Camerons and Beckhams are illustrative of national trends, but with some unexpected twists. David and his wife Samantha attended two of the country’s most famous public schools, Eton and Marlborough College.17 On the face of it the Cameron children have taken a downward generational step in education mobility. Much was made of the then Prime Minister’s decision to send his children to a local state primary school. But that would be to misunderstand the range of tactics the privileged deploy to gain the upper hand in the escalating arms race of education. An exclusive faith school in Kensington can be just as good as a private prep school for staying ahead, and away from, the rest.

Beckham bucks British educational traditions. His first steps to success came through on-the-job training rather than academic study.18 Beckham signed up as a Youth Training Scheme participant or ‘YTS’ boy – which had become a derisive label by the 1990s. But then Beckham’s sponsor was Manchester United Football Club, a world famous sporting institution.19 It is unusual for someone so successful, even those in sport or the creative arts, to have progressed through a lower-status vocational pathway – still looked down upon by elites groomed via the ‘royal academic route’.

Befitting the newly gained status of their parents, Beckham’s children meanwhile all attended private schools. The country’s leading fee-charging schools boast an incredible record of producing the country’s elites, generation after generation. But they encapsulate the powerful forces of economic and education inequality that combine and reinforce each other to limit mobility. Only the richest parents are able to invest in an elite education that ensures their children access the highest wages in a job market rewarding the highly educated.

Class Divides

Social class offers an alternative way of measuring mobility across the generations, categorizing people in ways that go beyond pounds or dollars earned. Occupation-based class measures are used, and advocates of using such measures argue it attempts to relay information about what jobs we do, what education we have had, and the traits, behaviours and attitudes that define who we are – including, for example, the way we speak and dress. A teacher may earn less than other professionals such as doctors and lawyers, but in most people’s eyes he or she is quintessentially middle class.

Social class was traditionally broken down into three broad distinctions: working class, middle class and upper class. And when journalists write news stories on social mobility they still turn to an image from a 1966 episode of the BBC’s David Frost show familiar to most British readers over a certain age.20 In the ‘Class sketch’ a tall John Cleese, in a bowler hat, represents the upper classes, Ronnie Barker, the middle classes, and a short Ronnie Corbett, in a cloth cap, the working classes. They each in turn describe their place in society.

Sociologists developed seven new social class groupings to describe the more complex make-up of the population to study mobility across more recent generations.21 Based on the job or occupation a person holds, these social classes can not only gauge a person’s status according to their earnings, but also proxies for their economic security and the degree of autonomy they enjoy in their workplace.

What is striking is that sociologists also observe greater immobility at the top and bottom of the social class hierarchy, despite deploying different measures and methods. One review highlighted ‘the social closure at the upper echelons of society and the isolation of those at the bottom’, contrasting these extremes with comparatively high levels of mobility elsewhere.22

New Order

In 2011 researchers unveiled yet another alternative social-class scheme to better reflect the characteristics that distinguish people in Britain in the early twenty-first century.23 Analysing the results of the BBC’s Great British Class Survey that gathered details on 161,000 people, academics presented a hierarchy of seven new class distinctions. A person’s status was assessed not just by their occupation, but by their combined levels of economic capital (their household income and savings), social capital (the networks of people they knew), and cultural capital (their education, behaviours, traits and attitudes).

At the apex of British society is an ‘elite’ group whose ‘sheer economic advantage’ sets them apart from the rest of the nation. Made up of chief executives and financial managers alongside traditional professionals such as dentists and barristers, they make up 6 per cent of the population. This exclusive group, educated at elite universities and likely to live in the south-east of England, has restricted upward mobility into its ranks.

At the bottom of the class structure is the ‘precariat’. Living precarious lives on a low income and likely to be renting their accommodation and experiencing high levels of insecurity, this group constitutes 15 per cent of the population. It is made up of the unemployed, cleaners, care workers, postal workers and shopkeepers mainly from outside the south-east of England.

Long-range social mobility, rising from the precariat to the elite group, seldom happens. More common is short-range movement between middle-class groupings, enabled by the social and cultural capital accumulated by going to university. These patterns, of particular stickiness at the bottom and top of society, chime with those observed by economists, demonstrated in the U-shaped mobility charts above.

In social-class terms Cameron maintained his family’s position at the very apex of society – a pattern that has persisted for several generations. But the Beckhams are the latest examples of new moneyed elites finding the upper rungs of the class ladder a slippery climb. Their supreme wealth and social connections make them a match for anyone in terms of economic and social capital. And they are catching up culturally. Academics have demonstrated that David and Victoria drop the H sounds at the start of words far less often than they used to.24 The working-class accents that once betrayed their beginnings have been shed. Posh Spice has become Posher Becks.

And yet the denial of Beckham’s knighthood suggested the establishment was not quite ready to accept the tattooed national icon into its uppermost ranks. The honours system remains one of the last bastions controlled by the upper social classes. Journalists often ask the age-old question: is Britain still a class-ridden society? It is. It’s just that what constitutes class is always changing. Economists’ measures of income mobility provide a constant lens to observe an evolving landscape. But class matters.

The Caravan: Relative and Absolute Progress

The tale of the two Davids points to two different social mobility challenges: the millions of adults stuck at the bottom of the social ladder from which Beckham was fortunate to escape; and the retention of social elites at the top of the ladder which Cameron so typifies.

Beckham’s journey might be held up as an example of how with enough talent, determination and hard work (and tireless support from dedicated parents), anyone can make it in modern Britain. But it is the exception, not the rule. Much more than we would imagine, we replicate the footsteps of our forebears. Beckham has joined Cameron among the social elites who are incredibly adept at maintaining their advantage from one generation to the next.

These twin challenges highlight another important feature of social mobility: whether we measure it in absolute or relative terms. To understand the difference, a useful metaphor is to imagine the nation as a caravan travelling through the desert. The pace of the travellers as they walk along their journey represents progress in life whether measured by income, social class or education. An increase in absolute mobility would see everyone – the poor at the rear, and the rich pulling away at the front – quicken their pace and reach a better destination than their forebears. But no one would change their relative position.

An increase in relative mobility would see formerly under-nourished but naturally strong travellers at the back overtake people in front of them. Improving relative mobility without an improvement in absolute mobility is a zero-sum game – one person’s gain is another’s loss in life’s rankings.

Ideally we would want a society that had high levels of mobility in both absolute and relative terms: all people are moving more quickly, but people are leapfrogging others as well. We want the strongest walkers, irrespective of where they started, at the front to lead us on the best possible path forward.

In modern Britain, widening income and wealth inequality makes changing places more difficult. The rich have been pulling further away from the poorer people behind them: as this happens, it is harder for people to catch up. At the same time, a lack of supplies (due to falling median real wages) means that the pace of the caravan for most people has been slowing, and everyone is doing all they can to retain their place.

An obvious improvement for all travellers would be to narrow the lengthening gaps in life’s caravan. But it is difficult to reach consensus on this: those at the front want the freedom to stretch out; they believe others can join them if they make enough effort. Narrowing gaps, they argue, would remove any incentives to strive harder, leading to lazy walkers slowing everyone down.

Improving relative mobility, ensuring the fittest people from all positions in society have the option of getting to the front of the caravan, would produce not only the fittest leaders, but also those who understand the plight of fellow travellers in the distance behind them. What is clear is that walkers require a good education, the nourishment needed to progress, but also a helping hand to traverse a rough terrain.

The lack of movement in who gets where in the world – particularly when people are stuck at the bottom and the top – costs the nation dear in wasted talent. Shrinking opportunities overall, the growing forces of globalization, automation and widening inequality, makes the goal of improving social mobility in Britain tough. Our caravan is walking into a perfect storm.

Failure to do something about this will store up greater social and economic problems for future generations. It will ultimately unravel the cohesive society we all want to live in. Without drawing on talents from all backgrounds our elites become detached from, and disinterested in, the rest of society.

David Beckham’s rise highlights why mobility is so often a one-way street. Britain’s social mobility problem defies normal logic. What goes up doesn’t always come down. David and his wife Victoria have devoted considerable resources to ensure that their four children secure opportunities that are increasingly out of reach for the rest of the population. All three of the Beckhams’ sons, for example, were enrolled into the exclusive Arsenal Football Club academy – an impossible dream for most boys and girls. Fashion, music and modelling careers have been mooted. In Britain’s bleak mobility climate, children outside these elite cliques have little hope of accessing these opportunities, irrespective of how much talent or work ethic they may have.

Cameron’s aides advised him against too much talk about social mobility for fear of attracting attention to his privileged upbringing. But Cameron said the Conservatives were now ‘the party of aspiration’. ‘Britain has the lowest social mobility in the developed world,’ he told the Conservative Party conference in 2015. ‘Here, the salary you earn is more linked to what your father got paid than in any other major country.’25 Yet for all the rhetoric, in office Cameron dismissed concerns about socially selective schools, unpaid internships and low inheritance tax. He will be remembered as the leader of a detached metropolitan elite who misjudged the mood of the people when they voted to leave Europe.

Cameron’s advisers came up with a clever phrase for the Prime Minister. It demonstrated his aspirations for a classless society where background does not matter: ‘It’s where you’re going to, not where you’re from that counts.’ But the mantra was a fallacy. In Britain it has become increasingly the case that where you come from – who you are born to and where you are born – matters more than ever for where you are going to.