CHAPTER 35 NATIVE AMERICAN HEALING

OPENING NOTE

Indian people are understandably wary of the written word. Some may criticize the inclusion of this chapter in this edition. This criticism is understandable, because often the written word objectifies understandings and can be manipulated outside the relationship in which the understanding was shared. This possibility is a concern and a risk in contributing this chapter to the fourth edition of Fundamentals of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. However, not to include a chapter on American Indian views about medicine and health care would also be a concern, because it helps perpetuate the invisibility of Indian people amidst the dominant social, political, and religious factions. The untold history of Native American people is a sobering context in which one must view contemporary concerns. The purpose of this chapter is to honor the continuing journey of understanding between medical science practitioners and traditional Indian medicine practitioners to see how these two pathways can help restore health to people and bring about increased understanding—wo’wa’bleza—among peoples. This chapter is not intended to encourage “mixing” of Indian medicine with mainstream allopathic, or “alternative,” medicine (as yet another example of so-called “integrative medicine”), but rather to emphasize the importance of respecting the integrity of each of these paths in bringing health and help to people in need.

It is this loss of faith that has left a void in Indian life—a void that civilization cannot fill. The old life was attuned to nature’s rhythm—bound by mystical ties to the sun, moon, stars; to the waving grasses, flowing streams and whispering winds. It is not a question (as so many white writers like to state it) of the white man “bringing the Indian up to his plane of thought and action.” It is rather a case where the white man had better grasp some of the Indian’s spiritual strength. I protest against calling my people savages. How can the Indian, sharing all the virtues of the white man, be justly called a savage? The white race today is but half civilized and unable to order his life into ways of peace and righteousness. (Standing Bear, 1931)

These words of Luther Standing Bear provide a sobering orientation toward understanding a pan-Indian perspective of medicine and health. Long before Columbus landed in what he thought was Hindustan, the indigenous peoples of the Americas practiced a highly advanced medicine that was effective in combating diseases then common in the Americas (Iron Shell, 1997; Little Soldier, 1997; Looking Horse, 1997; Red Dog, 1997; Standing Bear, 1933). These medicine ways emphasized the “right order of things” and viewed humans not as some higher intellectual being above lower animal and inanimate beings but as a kindred partner in the universe (creation), reliant on the other beings in creation for life itself.

The worldview of the new European visitors to the Americas, from the beginning, prompted misunderstandings and exploitation of the peoples they called Indios, actually a corruption of the Spanish, derived from Columbus’s perception of the people he encountered in the New World. He described them as “una gente en Dios,” which literally means “a people in with God” (Means, 1995).

Tragically, this early perception of the natural peacefulness, harmony, and ease of temperament of these “Indians” prompted Columbus to conclude that “they would make excellent slaves” (Means, 1995). This set the stage for the subsequent historical events that led to the degradation of the indigenous, or natural, people of the Americas who were called Indians. The “natural” style of these people was to be perceived as “brutish” and “savage”(words that could have been taken from Thomas Hobbes in his description of seventeenth century European society [see Chapter 7]); their attentiveness to primal experience would be perceived as “primitive”; their understanding of the creation (all of the universe) as infused with life and spirit would be seen as “animistic.” In all these assessments, what was “Indian” was evaluated as inferior to the European cultural standards, including advanced technology and “higher” (theistic) religion(s).

The single term Indian was imposed on the indigenous peoples of the Americas erroneously, because they were not a homogeneous group but rather distinct “nations” or “peoples” with different languages, beliefs, customs, social and political structures, and historical rivalries. The term American Indian is used today to talk about common values and a certain shared identity among many Native American people, and it is also used as the legal title of federally recognized tribes holding jurisdiction on reservation lands in the United States. The indigenous people of Canada and the Six Nations’ People (Iroquois) preferred the term Natives, which is the official term used by the Canadian government to identify indigenous people. The terms American Indian, Native American, and Indian people are used interchangeably throughout this chapter, with an awareness of the historical and political complexity associated with these terms (Means, 1995).

HISTORY

To understand American Indian health care and approaches to medicine, one needs to get the history right and take a critical look at the “other” American history that most Americans were never taught, that was never included in their textbooks, and that continues to be glossed over in mainstream American classrooms—the largely invisible history of Native Americans in the United States. Non-Indian people need to learn both sides of American history, to understand the “bad medicine” that has infected relations between Indians and non-Indian people. Recall the interaction between Tosawi, chief of the Comanches, and General Sheridan (who had put the torch to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia during the Civil War) after Tosawi brought in the first band of Comanches to surrender. Addressing Sheridan, Tosawi spoke his own name and two words in English: “Tosawi, good Indian.” Sheridan responded with the now-infamous words: “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead” (Ellis, 1900, cited in Brown, 1970, p. 170).

Beyond the larger cultural-historical context, one also needs to consider the distinctive Indian tribal culture. It is important to know how each tribe dealt with its own survival in the wake of U.S. expansionism, policies of extermination, and level of exposure of each tribe to racial and cultural genocide. It is also important to understand how its tribal leadership related with the U.S. government and to assess the degree of broken trusts and treaties. With this background information, one can then develop an awareness of, and sensitivity to, the issues that have an impact on the consciousness and sense of well-being or disease and distrust of government and other social institutions by many Native American people today. One needs to be informed about the issues of loss of land and culture, repeated broken trusts, and unenforced treaties. One must be sensitive about the forced assimilation policies and programs, and depersonalizing attitudes directed toward Indian people, both formally and informally, by the U.S. government, missionaries, and other social institutions that were embedded in the “progressive American consciousness” and committed to civilizing and incorporating the Indian into this larger consciousness.

Although some Indian people claim to have benefited from their boarding school experience, the greater number of Indian people are beginning to speak out about the cultural trauma of the boarding school systems. Through assimilation programs, what was “natural” and basic to Indian self-identity was suppressed, discouraged, and literally beaten out of Indian people through systematic resocialization. Indian children were separated from their families and their traditional ceremonial practices, which were intimately linked to the extended family and reinforced by social, moral, political, and spiritual life, and introduced to what was perceived as a more civilized (materialistic) view of life, which devastated Indian society (Clark, 1997; M Clifford, 1997; Douville, 1997a; Little Soldier, 1997; Mestheth et al, 1993; White Hat, 1997). For Indian people, all aspects of life were intimately connected to good health and well-being. The interconnections among family, tribe or clan, moral, political, and ceremonial life all contributed to a sense of harmony and balance that was called wicozani (good total health) by the Lakotas and hozhon (harmony, beauty, happiness, and health) by the Navajos.

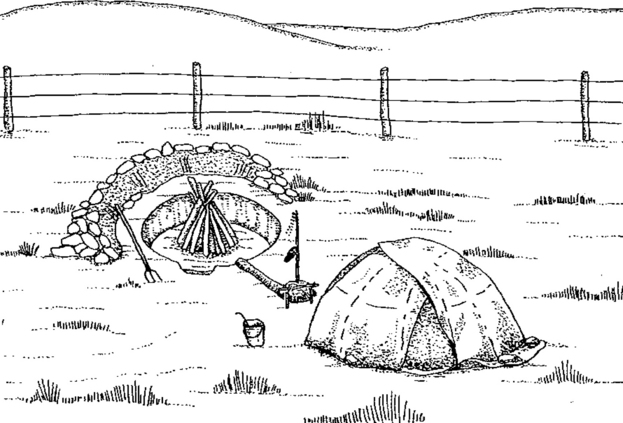

Traditional Navajo healing practices revolve around the notion of hozho, a term that embodies the concepts of balance, harmony, and spirituality. When people achieve a life of hozho, they walk the “Beauty Way,” and their lives are filled with peace, contentment, and positive health—physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. Positive interconnections among family, clan, tribe, nature, all living things, and ceremonial life all contribute to a sense of harmony and balance, which is the achievement of hozho. When a Navajo medicine man performs a healing ceremony, a circle of healing is formed by the interconnection among the sick person, family, relatives, the spirits, and singers who help with ceremonial songs. For traditional Navajo, the world is a dangerous place requiring due caution and respect; there is an emphasis on preventing harm from occurring through prevention-type ceremonies (hozonji) to better meet this dangerous world. Navajo healers (hatalie) use sand painting to cure the sick person. A very stylized sand painting is drawn using various colors of sand; on its completion, the patient is instructed to sit on the painting while the healing ceremony is performed. Healing takes place as the sick person absorbs the power or spirits that exist in the sand painting (Figure 35-1) (Edwards, 2004).

Figure 35-1 Traditional sand painting (Artist: Frank Martin).

(Courtesy Penfield Gallery of Indian Arts, Albuquerque, NM, http://www.penfieldgallery.com.)

Case Study

Robert, a full-blood American Indian, has lived most of his life in a large metropolitan area. He was hospitalized in a residential treatment facility for depression, anxiety, weight loss, verbal and social regression, agitated moods, hysterical behaviors, and night terrors. During his hospitalization, these behaviors worsened, and he was noncompliant with the treatment plan, which included group and individual psychotherapy. Additional background included the following: Robert lived with his mother and two half-siblings; his mother was recently divorced from his stepfather; and Robert’s father died 6 years earlier.

An urban American Indian social worker from Robert’s tribe was called in as a clinical consultant to the hospital staff regarding Robert’s deteriorating mental and physical health status. The clinical consultant met first with staff and then with Robert. In their initial meeting, Robert and the American Indian clinical consultant conversed in their native language regarding their parents, siblings, clans, home reservation areas, and cultural activities in which they both participated. They then talked about Robert’s current situation, including his hospitalization, his separation from his family, and his fears. Robert believed that his father had been hexed (someone had placed an evil spell on him) and died as a result of evil forces associated with this hex. Robert also believed that these evil forces could be unleashed on him, and that he, too, might die.

The clinical consultant talked with Robert about the spiritual ceremonies that could be arranged for him on his home reservation to restore balance and harmony in his life. Robert knew and understood the significance of these healing ceremonies and was willing to participate with the clinical consultant in arranging the ceremony for him. The clinical consultant, an enrolled member of a recognized American Indian tribe, gave Robert an eagle feather and talked to Robert about the power and protective nature of the eagle feather, the value of his cultural healing traditions, and the importance of his native culture in restoring balance and harmony in his life. A healing ceremony was arranged for Robert on his home reservation, where the Indian medicine people were able to provide information and healing to Robert, effectively allaying much of his anxiety, to the point where he was amenable to participating in the recommended clinical treatment available at the hospital. The combined therapies contributed to a positive treatment outcome.

Native American Church and Peyote

The term Peyote religion describes a wide range of spiritual practices primarily of tribes of the American Southwest that have expanded into a kind of pan-Indian movement formally recognized as the Native American Church. Peyote religion incorporates the ritual use of peyote, the small spineless peyote cactus Lophophora williamsii, into its spiritual and healing ceremonies. The peyote ceremony is led by a recognized practitioner who is referred to as a “roadman” and is sponsored by an individual or family requesting a ceremony, usually for some specific need or healing or to recognize some event, such as a birthday or an important life transition.

The term peyote is derived from the Aztec word péyotl. The Peyote Way religions have expanded their spheres of influence from an area around the Rio Grande Valley, along the current U.S.-Mexican border, to indigenous groups throughout Central and North America (Anderson, 1996).

The ritual use of peyote has roots in antiquity. A ritually prepared peyote cactus was discovered at an archeological site that spans the U.S.-Mexican border dated to 5700 years before the present. Other archeological evidence, paintings and ritual paraphernalia, indicates that the indigenous people of that region have been using both peyote and psychoactive mescal beans ritually for over 10,500 years (Bruhn et al, 2002).

The Peyote Way is a complex bio-psycho-social-spiritual phenomenon that encompasses much more than the pharmacologically active plant. The contemporary peyote practice found in the United States and Canada, and among mestizo peoples in Mexico differs significantly from the older rites that continue to be practiced by the Huichol, Cora, and Tarahumar peoples in Mexico (Steinberg et al, 2004). The forebears of the modern Native American Church were the Lipan Apaches, who brought the practice from the Mexican side of the Rio Grande to their Mescalero Apache relatives around 1870. From the Mescaleros it spread to the Comanches and Kiowas in Oklahoma and Texas. It quickly expanded to most of the eastern tribes forcibly relocated to the Oklahoma Territory. The quick spread from the Mescaleros to most of the Oklahoma tribes has been attributed to the loss of traditional religions because of oppression (Anderson, 1996).

The psychedelic properties of peyote are just one part of the whole spiritual package. “This is not to say that peyote does not facilitate visions but rather that it is only one influence in a total religious setting” (Steinmetz, 1990, p. 99). It is important to note that describing peyote as a “psychedelic,” although accurate, is fraught with problems, particularly when the Peyote religion is studied outside its indigenous context. Here, one needs to differentiate the ritual use of peyote by indigenous practitioners, or roadmen, and Native American Church participants from use or abuse of peyote by curiosity seekers and experimenters who are simply seeking a “high” devoid of a ceremonial and cultural context. Peyote has been described as both a psychedelic and an entheogen. Entheogens are chemical or botanical substances that produce the experience of God within an individual, and it has been argued that such drugs must be included as a necessary part of the study of religion (Roberts, 2002). Entheogens have also been defined as psychoactive sacramental plants or chemical substances taken to induce a primary religious experience. In keeping with this understanding, the complementary use of the peyote ceremony within the context of mental health treatment has been viewed as a form of cultural psychiatry (Calabrese, 1997). Other entheogens include psilocybin mushrooms and dimethyltryptamine-containing ayahuasca, which, like peyote, have been used continuously for centuries by indigenous people of the Americas (Tupper, 2002).

Mental health practitioners across several disciplines may view Peyote Religion and the Native American Church with some degree of suspicion, if not with downright skepticism. Mack (1986) discussed the medical dangers of peyote intoxication in the peer-reviewed North Carolina Journal of Medicine. Mack refers to the users of peyote as “the more primitive natives of our hemisphere” (p. 138) and gives repeated attention to details of nausea, vomiting, and bodily reactions which occur at doses that he failed to mention were 150 to 400 times higher than the ceremonial amount reported nearly a century earlier (Anderson, 1996). So there is need for reasoned and open discourse on this important resource and potential partner for the mainstream mental health practitioner.

Psychiatric researchers Blum et al (1977) looked at the mildly psychedelic effects of the peyote coupled with Native American Church ritual and exposure to positive images projected by the skillful use of folklore by the roadman. They found that these components facilitated an effective therapeutic catharsis. Albaugh and Anderson (1974) hypothesized that peyote created a peak psychedelic experience similar to that found when lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) was used as an adjunct to psychotherapy in alcoholics. In a study of a group of lifelong drug- and alcohol-abstaining Navajos, Halpern et al (2005) found no evidence of psychological or cognitive deficits associated with regularly use of peyote in a religious setting. However, the placement of peyote, LSD, and other psychedelics on Schedule I of the federal drug classification has eliminated public funding of research into psychedelic drugs (Strassman, 2001) and has limited scientific inquiry into their effects. The current biomedical opinion on the efficacy of entheogens is that data are inconclusive (Halpern, 2001), but there is limited evidence that further study is warranted. Wright (2002) has suggested that those in the behavioral sciences should once again open their minds to incorporating mind-expanding substances in the psychiatric and psychotherapeutic treatment milieu. As science takes a more benign look at the effects of traditional healing practices on brain chemistry, new pathways for treatment may be opened up for study and discussions about traditional indigenous healing methods may be renewed (see Hwu et al, 2000).

Acknowledgments to Robert Prue, enrolled member of the Lakota Sioux, for his contribution.

This case study illustrates a number of important components of the relationship between traditional healing methods and Western medicine practices relevant to this discussion. First, the clinical consultant was able to speak the native language of the patient and could comprehend the cultural significance of the problems Robert was facing, as well as the corresponding cultural resources available to address these problems in a culturally compatible manner. Second, the consultant was able to explain to the non-Indian hospital staff Robert’s perceptions of his problems and desire to participate in a traditional healing ceremony. Third, the clinical consultant, as an enrolled member of a recognized tribe, was able to give Robert, also an enrolled member, an eagle feather (illegal for non-Indians to possess), which requires considerable generosity on the part of the giver and is a sign of utmost respect for the person to whom the gift is given. Fourth, it is important to note that regardless of the current residence or length of time Native people have lived off the reservation, identification with Native traditions and cultural practices may play a very important role in their construction of meaning in life events, as well as in their understanding of health and well-being. Finally, the case study illustrates well how Western medicine and traditional Indian medicine may complement each other in promoting good health and wellness among traditional American Indians living both on the reservation and off the reservation. (A version of this case study appeared in Social Work: A Profession of Many Faces [Edwards et al, 1998, pp. 477-478].)

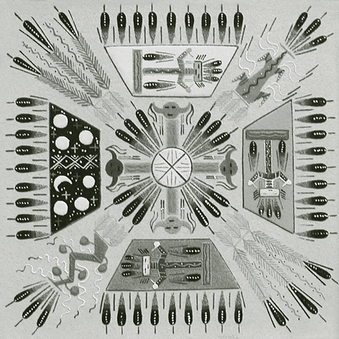

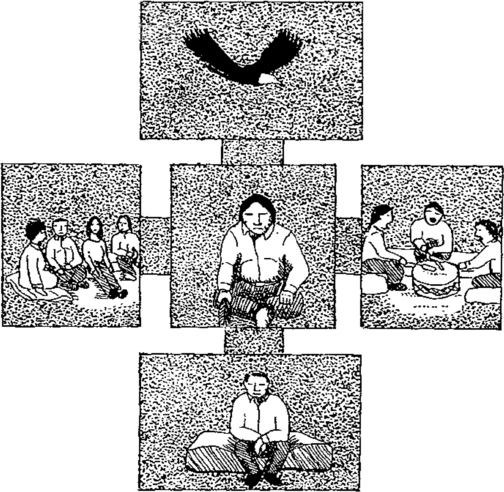

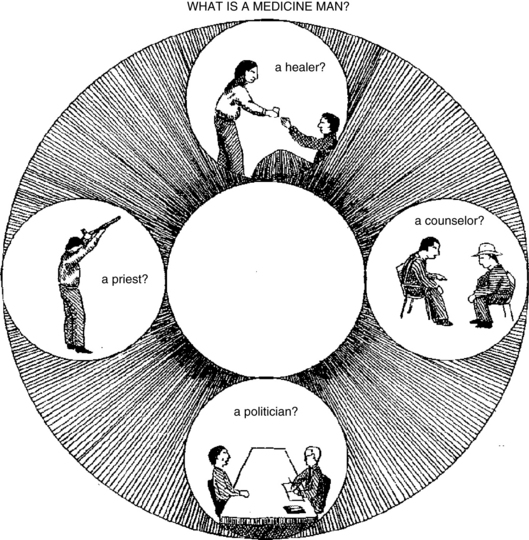

For Indian people, life is like a circle: continuous, harmonious, and cyclical, with no distinctions. Medicine was a coming together of all the elements in this circular pattern of life. The circle of healing was formed by the interconnections among the sick person, his or her extended family or relatives, the spirits, the singers who helped with the ceremonial songs, and the medicine practitioner (Figures 35-2 and 35-3).

Figure 35-2 Spirits, relatives, singers, and sick person in the shape of two intersecting lines.

(Courtesy Sinte Gleska University.)

Figure 35-3 All of the elements from Figure 35-2 are depicted in this ceremony of the extended family in the healing process. The drawing shows a quiet gathering of people in a darkened room.

(Courtesy Sinte Gleska University.)

Therefore, as ceremonial practices were suppressed and as government policies undermined the integrity of traditional Indian practices, the cultural fabric of Indian peoples was also torn. Official U.S. government assimilation policies forced many traditional Indian medicine practitioners underground for risk of being cited for committing actions prohibited by government regulation or being accused of “devil worship” and held up to public ridicule. Archie Fire Lame Deer and Richard Erdoes note, “Between 1890 and 1940, the Sundance, as well as all other native ceremonies, were forbidden under the Indian Offenses Act.” They recall the following:

One could be jailed for just having an Inipi [a sweatlodge ceremony] or praying in the Lakota way, as the government and the missionaries tried to stamp out our old beliefs in order to make us into slightly darker, “civilized” Christians. Many historians believe that during those fifty years no Sundances were performed, but they are wrong. The Sundance was held every year . . . but it had to be done in secret, in lonely places where no white man could spy on us. (Lame Deer et al, 1992, p. 230)

Clyde Holler notes that the official ban on the Sundance began on April 10, 1883, with the enforcement of the Rules for Indian Courts; these rules were in effect until 1934, and the ban on piercing was in effect until 1952 or later, depending on interpretation (Holler, 1995; see also Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1883).

Luther Standing Bear reflected on the profound shift that was occurring as he recalled his experience traveling to the Carlisle Indian School as a boy. He wrote as follows:

It was only about three years after the Custer battle, and the general opinion was that the Plains people merely infested the earth as nuisances, and our being there simply evidenced misjudgment on the part of Wakan Tanka. Whenever our train stopped at the railway stations, it was met by great numbers of white people who came to gaze upon the little Indian “savages.” The shy little ones sat quietly at the car windows looking at the people who swarmed on the platform. Some of the children wrapped themselves in their blankets, covering all but their eyes. At one place we were taken off the train and marched a distance down the street to a restaurant. We walked down the street between two rows of uniformed men whom we called soldiers, though I suppose they were policemen. This must have been done to protect us, for it was surely known that we boys and girls could do no harm. Back of the rows of uniformed men stood the white people craning their necks, talking, laughing, and making a great noise. They yelled and tried to mimic us by giving what they thought were war-whoops. We did not like this. (Standing Bear, 1933)

To this day many older Indian people are reluctant to talk about their traditional ways, and many middle-aged Indian people who were educated in the boarding school system were literally removed from their tribes and forced to assimilate. Resocialized in often abusive environments, many never learned the older traditions and their native languages. Often, students from western tribes were sent east to the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and students from eastern tribes were sent west (e.g., the Nanticokes of Delaware were sent to the Haskell Indian School in Kansas) (Clark, 1997).

Other Indians whose behavior seemed odd or troublesome were sent to the infamous Hiawatha Insane Asylum for Indians, also known as the Canton Insane Asylum, which was the only segregated asylum built exclusively for American Indians in the United States, located in Canton, South Dakota (Hoover, 1997; Iron Shield, 1992; Putney, 1984). This institution was opened in 1902 as the second federal institution for the insane (predated by St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, DC, now long closed) to provide psychiatric care exclusively to Indian people by an act of Congress, despite opposition from the Department of the Interior and the Superintendent of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital when the bill was first passed by Congress in 1898 (Iron Shield, 1988, 1992). Under the abusive administration of Dr. Harry Hummer, the institution would become the subject of a 150-page report filed by Dr. Samuel Silk in 1929 detailing the abhorrent conditions endured by the patient-residents there.

As a result of Dr. Silk’s report, Dr. Hummer was dismissed, and in December 1933, after further study, the Hiawatha Asylum for Indians was closed and its remaining 71 Indian patients were transferred to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. Over the 31 years of operation, the asylum housed 370 Indians. There are 121 Indians buried on the grounds of the former asylum; the causes of these deaths are unknown. The asylum was founded “as a place to alleviate the suffering of mentally ill tribesmen from the Indian reservations; it ended as an institution that itself caused genuine human misery” (Putney, 1984). The asylum was turned into a community hospital in the 1950s and is now the Canton-Inwood Memorial Hospital. The Indian burial ground is now located next to the Hiawatha Golf Course, which sits adjacent to the grounds of the asylum in Canton (Iron Shield, 1991, 1994, 1997). Harold Iron Shield is currently leading a movement to identify relatives of those buried at the Canton (Hiawatha) asylum and is seeking to repatriate their remains to their respective tribes, when possible, and to preserve the cemetery as a National Historic Site.

Medical treatment and health care for American Indians was historically grossly inadequate and often seen as antagonistic to traditional Indian medicine ways. There was no supervision of agency doctors, and “not until 1891 were physicians placed in a classified service and required to pass examinations in addition to having a medical degree” (DeMallie et al, 1991). Charles Alexander Eastman, a Lakota Sioux Indian who served as an agency physician at Pine Ridge from 1890 to 1892, observed the practice of government-sponsored medical care. He wrote as follows:

The doctors who were in the service in those days had an easy time of it. They scarcely ever went outside of the agency enclosure, and issued their pills and compounds after the most casual inquiry. As late as 1890, when the Government sent me out as a physician to ten thousand Ogallalla Sioux and Northern Cheyennes at Pine Ridge Agency, I found my predecessor still practicing his profession through a small hole in the wall between his office and the general assembly room of the Indians. One of the first things I did was to close that hole; and I allowed no man to diagnose his own trouble or choose his pills. (DeMallie et al, 1991)

Physicians in the Indian Service had to use their own funds and gifts of money from friends to buy medicines and supplies. Drugs supplied to the Indians were “often obsolete in kind, and either stale or of the poorest quality” (DeMallie et al, 1991). In 1893, Dr. Z.T. Daniel recommended that the procedures for Indian Service doctors be reappraised, modernized, and compiled in serviceable form. He also recommended that an agency physician be sent annually as a representative of the American Medical Association, and he urged that Indian Service doctors be supplied with medical textbooks and medical journals.

In light of the inadequate health care provided to Indian people, it is important to keep in mind the decimation Indian people faced through exposure to Old World diseases. Henry Dobyns (1983) estimated that Native people faced serious contagious diseases that caused significant mortality at approximately 4-year intervals from 1520 to 1900. The pandemics affecting Indian people are often treated by white historians and others as types of “natural disasters,” never intended by Europeans (Jaimes, 1992). However, Indian people are cognizant of their history and remember their oral history in which forms of germ warfare were related to have been conducted in military operations against them. One example often cited was the distribution of smallpox-infected blankets by the U.S. Army to Mandan (Indians) at Fort Clark on June 19, 1837, which was thought to be the causative factor in the smallpox pandemic of 1836 to 1840 (Chardon, 1932; Jaimes, 1992).

The shame caused by decades and centuries of efforts to “civilize the heathen Indian” has taken its toll on our American consciousness. One cannot begin to appreciate traditional Indian medicine ways without a profound awareness at a gut level of how much effort went into the eradication of what is now being perceived as “alternative medicine.” This is the uneasy starting point of understanding traditional Indian medicine. Within this historical context, one can better perceive the basis for many Indian peoples’ objections to the growing “popularity” of their traditional spirituality and healing practices among non-Indians—by the wasicun. This Lakota word described the early white hunter’s propensity to take the fatty, choice portion of the buffalo, and leave the rest to rot. Buechel (1983) translates it as “one who takes things.” This term is still used today to express Indian people’s perception of the narrow, materialistic, and destructive worldview of mainstream white culture. Interest among whites in seeking out “Indian medicine men and shamans” and the resultant exploitation of Indian ceremonies (e.g., buying Indian spirituality in weekend or half-day workshops and seminars, paying fees for sweatlodge ceremonies) have prompted some Lakota leaders to issue a “declaration of war” against such exploitation (Mestheth et al, 1993). There are strong feelings about the contemporary curiosity of whites about Indian medicine ways.

WILLIAM PENN’S ACCOUNT OF TENOUGHAN’S SWEATBATH

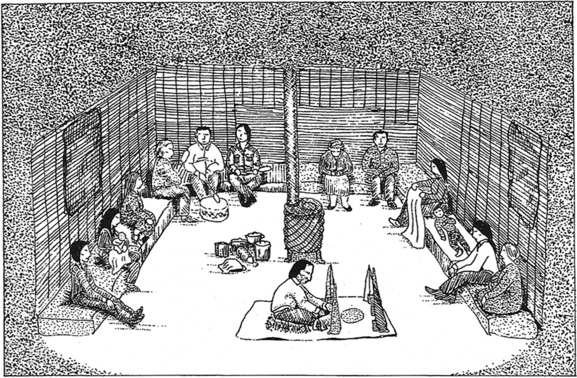

One of the earliest accounts of a European observing an American Indian healing ceremony is in William Penn’s Own Account of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians (Meyers, 1970). The account portrays many factors relevant to understanding Indian medicine ways and the quality of interaction of Indian people with Europeans. The portion cited here is Penn’s observation of a Lenape man named Tenoughan involved in a healing sweatbath (Figure 35-4).

I called upon an Indian of Note, whose Name was Tenoughan, the Captain General of the Clan of Indians of those Parts. I found him ill of a Fever, his Head and Limbs much affected with Pain, and at the same time his Wife preparing a Bagnio for him: The Bagnio resembled a large Oven, into which he crept, by a Door on the one side, while she put several red hot Stones in a small Door on the other side thereof, and fastened the Doors as closely from the Air as she could. Now while he was Sweating in this Bagnio, his Wife (for they disdain no Service) was, with an Ax, cutting her Husband a passage into the River, (being the Winter of 83 the great Frost, and the Ice very thick) in order to the Immersing himself, after he should come out of his Bath. In less than half an Hour, he was in so great a Sweat, that when he came out he was as wet, as if he had come out of a River, and the Reak or Steam of his Body so thick, that it was hard to discern any bodies Face that stood near him. In this condition, stark naked (his Breech-Clout only excepted) he ran into the River, which was about twenty Paces, and duck’d himself twice or thrice therein, and so return’d (passing only through his Bagnio to mitigate the immediate stroak of the Cold) to his own House, perhaps 20 Paces further, and wrapping himself in his woolen Mantle, lay down as his length near a long (but gentle) Fire in the midst of his Wigwam, or House, turning himself several times, till he was dry, and then he rose, and fell to getting us Dinner, seeming to be as easie, and well in Health, as at any other time (Surveyor General Thomas Holme’s letter, dated 5th Month [May] 7, 1688, concerning the running of a survey line). (Meyers, 1970)

Figure 35-4 Benjamin West’s painting of William Penn’s treaty with the Indians.

(Courtesy Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr.)

Penn made this observation when he was on a surveying expedition of the “farthest northern region of his Provence,” which was actually near Monocacy, Berks County, Pennsylvania, today about a 45-minute commute from Philadelphia. The river would be the Schuylkill River, now polluted by a century of industrial contaminants and washoff from coal mines and agriculture farther north. This old account provides a powerful illustration of the cultural chasm that separated Penn from Tenoughan’s world of medicine and health care. This story conveys the tremendous gap in appreciating what was happening during the observation. Penn was intent on buying land from the Lenape people, so it was on an economic venture that he stumbled on a healing bath taken by Tenoughan, a Lenape leader of some stature.

The story provides a model for understanding the complexity and the obstacles that confront non-Indian people, embedded in Eurocentrism, who do not comprehend Indian medicine ways. Penn was struck by the exotic and the unusual nature of the event he witnessed, as well as the apparent efficacy of the sweatbath on Tenoughan, but the observation lacks any description of a real personal encounter between Penn and Tenoughan, although we read that Tenough served dinner for his guests after the sweatbath. As old and as minimally detailed as is this account, it provides a number of important insights into American Indian medicine and health care.

First, the sweatbath was located near Tenoughan’s home. It was familiar—literally in his backyard. Second, the practice included the assistance of a family member, Tenoughan’s wife, who actually prepared the sweatbath for him, carried the red hot stones into the bagnio, and assisted in closing the door securely. Much of Indian medicine is family oriented; it is not something that is done by strangers. Medicine is a family matter; family is intimately involved and plays a significant role in the healing process. Later, Tenoughan’s wife assisted in the arduous task of cutting a path through the ice for the “patient” to plunge into the river. Indian medicine often brings the patient into close interaction with the natural world and the elements. After the sweatbath, Tenoughan rests by the fire in his wigwam, and he then serves dinner to his guests. For many Indian people, stone, fire, air, water, food, spirits, and social and familial relationships are seen as medicine.

CULTURE

Sutton and Broken Nose cite a powerful clinical vignette about how cultural differences can create real tension between the expectations of clinical practitioners from the dominant culture and Indian sensibilities and practices. Although they cite the experience of a social worker sent to run an alternative school program on a Montana Indian reservation, the setting could be any health care or service-oriented setting. The vignette is quoted in the following:

One day I came into work and no one was there. There were no teachers, students, or counselors. At first I thought it was Saturday or some holiday I had forgot about. I checked my calendar and the one the tribe printed to see if it was some special kind of Indian holiday, but it was not. Finally, I went riding around in my car. I saw one of the counselors and asked where everyone was. He said Albert Running Horse had died. I found out later that Albert was one of the oldest men in the tribe and was somehow related to almost everyone at school. When I tried to find out when everyone would be back at work, I couldn’t get a definite answer because they weren’t sure when some of Albert’s relatives would come in from out of state. I was upset because I felt we had been making progress with some particularly difficult cases. I was concerned about the continuity of therapy and the careful schedule we had all worked out. When I expressed my frustration to one of my counselors she just shrugged her shoulders and said we all have to grieve. All I could think of is how am I going to explain this to my superiors. (McGoldrick et al, 1996)

This example illustrates the fundamental difference in worldview between Indian and non-Indian Americans and presents a common clinical dilemma that is likely to occur when mainstream approaches to health care come up against the “natural” approach to healing and human relationships typical among Indian people. Which is the better medicine: following the prescribed treatment plan or attending to the sense of community loss and grief on the death of an esteemed elder? Health care practitioners need to look for ways to affirm and support the values, beliefs, and needs of Indian people. Conversely, these values, beliefs, and needs may well be the same for non-Indian people as well, but be denied in the face of economic expediency. Appreciating the impact of diverse cultures on medical and health care practice is essential and is perhaps the most important thing the health care practitioner needs to address in developing cultural competence with Indian people or with any group not often credited or valued by the larger, dominant culture.

First, the concept of “professional helper/healer” is foreign to traditional Indian peoples and has no precedent in prereservation Lakota society. The idea of paid professionals conflicts with the tradition that helping other people is a social responsibility for everyone, not just for a few. Professional or paid health care practitioners are often viewed with suspicion by traditionalists as governmental agents of forced assimilation. Along with government-sanctioned missionary activity, the legacy of Indian boarding schools, and psychiatric hospitalization, health care professionals were associated with oppressive social structures that were intended to “civilize the Indian.” Thus, a Lakota-centric view of health care starts with the awareness of the power of the institutionalized systems (e.g., social, health care, educational systems) to influence and assert social control, which although aimed at “improved health care” or social well-being, may also reflect and enact the larger, more pervasive oppression of racist attitudes, policies, and procedures for “civilizing the Indian.”

Although no permanent or paid professional “health care providers” were among the Lakota bands or tribes in prereservation days, various individuals, groups, and societies within Lakota bands provided health care to the people. In effect, every tribal member was expected to follow the “natural law of creation,” or the wo’ope, the unwritten natural law that guides Lakota life, which emphasizes unselfishness and generosity. The wo’ope embodies the philosophy of mitakuye oyas’in, which, according to White Hat “is what keeps us together.” It is the knowledge “that we come from one source, and we are all related.” However, to make this work, “we must identify the good and evil in us, and practice what is good” (White Hat, 1997). Lakota philosophy does not separate good and evil, sickness and health, or right and wrong as distinct realities, they coexist in each person, in every creation; even in the most sacred thing there is good and evil. The important thing is to understand that there is the negative and the positive within everyone and everything, and to be responsible in one’s life to live in a good, moral, healthy way, in balance with all creation.

The natural law is the way nature acts. Understanding Lakota philosophy begins with understanding the natural law or the seven laws of the Creator (Iron Shell, 1997; Looking Horse, 1997; Lunderman, 1997). The natural law or the wo’ope required each person to exercise shared values, which, if acted on in one’s life, gave the person as well as the extended family (tios’paye) and the tribe wicozani, which was understood as total or perfect health, balance and harmony, good social health, and well-being (Iron Shell, 1997); it implies physical and spiritual health (White Hat, 1997).

Another orienting value of helpers and healers among the Lakotas is nagi’ksapa or self-wisdom, the awareness of your aura or spirit (Iron Shell, 1997). Albert White Hat, Sr. (1997) translates and explains the nagi’ksapa as “one’s spirit, the wise spirit in a person.” White Hat notes that “the Lakotas are very much aware of the spirit within [us]—we talk to our spirit—we ask our spirit to be strong and to help us in our decisions” and life. Iha’kicikta is the ability to look out for one another. If you move camp, you should be concerned that everyone is going to move together. You want to make sure there is enough water and food for everyone (Iron Shell, 1997). Wo’onsila is the ability to have pity on each other (Iron Shell, 1997). White Hat explains the word as “recognizing a specific need of someone or something, and you address that (specific) need.” According to White Hat, Lakota philosophy does not encourage people to “stay stuck” or dependent. Iyus’kiniya is the ability to go do things with a happy attitude (Iron Shell, 1997). Wi’ikt ceya is the measure of wealth by how little one has; it is the capacity to give to others; it is one’s capacity for self-sacrifice (Iron Shell, 1997). Teki’ci’hilapi is the ability to cherish, esteem, and treasure each other (Iron Shell, 1997). Putting into practice these social values ensured good social functioning.

The primary orientation of traditional Indian medicine was universalistic. Health and welfare resources were made available to everyone through the family and community. Prereservation Lakota society emphasized tribalism over individualism, social harmony over self-interest, and a commitment or loyalty to the people or the larger extended family relations over individual success. Health care functions were accomplished by one’s extended family (tios’paye); it was the extended family that provided for the social support and material assistance of all its members. Wealth was distributed through the practice of the giveaway ceremony (wopila), which is still practiced by traditional Lakotas. This practice ensured that no one person’s or one family’s wealth or resources dominated.

Mental health and physical health were viewed as inseparable from spiritual and moral health. The good balance of the one’s life in harmony with the wo’ope, or natural law of creation, brought about wicozani, or good health, which was both individual and communal. Rather than viewing the individual as a mind-body split, which has influenced much of Western psychiatric thinking, traditional Lakota philosophy viewed the individual person as an unexplainable creation with four constituent dimensions of self. The nagi is one’s individual soul; Buechel (1983) translates the word as “the soul, spirit; the shadow of anything, as of a man (wicanagi) or of a house (tinagi).” The nagi la is the divine spirit immanent in each human being. The niya, or “the vital breath,” gives life to the body and is responsible for the circulation of the blood and the breathing process. The fourth element of the person is the sicun, or intellect (Goodman, 1992, p. 41). Albert White Hat, Sr., however, describes the sicun as “your (spirit’s) presence [that] is felt on something or somebody.” Beuchel (1983) translates the word as “that in a man or thing which is spirit or spiritlike and guards him from birth against evil spirits.” Often a person appeals to his or her nagi la for assistance. This is a power within each person that can help him or her overcome obstacles. When one goes on the hanbleceya, or pipe fast, one leaves the physical world as a nagi.

According to Gene Thin Elk, “We are not humans on a soul journey. We are nagi, ‘souls,’ who are making a journey through the material world” (Goodman, 1992). The nagi la has been described as the “little spirit,” which is the “divine spirit immanent in each being” (Goodman, 1992). Existence in the material world is tenuous for the newborn, according to Lakota philosophy: Edna Little Elk commented, “The most important things for infants and little children are to eat good, sleep good and play good,” and doing so persuades the nagi of the child to become more and more attached to its own body (Goodman, 1992). Traditional Lakota philosophy views abuse, rejection, or neglect as affecting the child’s nagi, which may detach from the child’s body and not come back. In this case, ceremonies are conducted by a medicine man to find the child’s nagi and bring it back (Goodman, 1992). Such a condition has been called soul loss. Thus, good mental or emotional health is intimately related to good spiritual, moral, and physical health; these cannot be separated out. (See the Evolve site for a discussion of Native American herbs and medicinal plants.)

CONTRIBUTIONS OF INDIAN PEOPLE TO MEDICINE AND HEALTH CARE

Despite the fact that Native American people have ancient oral traditions of healing and helping tribal members in need during reservation times, prereservation times, and the traumatic transition periods in between (Douville, 1997a; Lunderman, 1997; Red Dog, 1997), much of the health care literature reviewed focused on practice issues concerning Native American people and viewed them primarily as a special client or health care risk group in need of a specialized approach to treatment (DuBray, 1985, 1992; Garrett et al, 1994; Good Tracks, 1973; Williams et al, 1996). This literature generally treats “Native Americans” as a generic, homogeneous group and does not examine specific tribal traditions or practices of help and healing.

DuBray calls for a more holistic approach to treatment intervention based on Native American (Lakota) practices. DuBray (1992) discusses the use of the vision quest, the importance of food as a symbol of love and respect, the role of cultural healing ceremonies, and the importance of the collective unconscious in Indian experience of reality. The contributions of Native American practices, philosophies, and traditions of help and healing have also been discussed in anthropological studies (Wallace, 1958), rehabilitation medicine (Braswell et al, 1994; Hodge, 1989), nursing (Reynolds, 1993; Turton, 1995), and psychiatric literature (Garro, 1990; Hammerschlag, 1988, 1992; Lewis, 1982, 1990). There is a growing use of traditional medicine ways in alcohol treatment programs for American Indians, both on and off the reservation (Hall, 1985, 1986; Red Dog, 1997; Thin Elk, 1995a, 1995b, 1995c), as well as in health programs for Indian children and youth (e.g., Healthy Nations Program of the Cheyenne River Sioux tribe) (Red Dog, 1997).

The timing is ripe for health care and medical educators to look carefully at how native practices, traditions, and values can shape theory, practice, and policy at a foundational level. This is particularly important as tribal governments develop strategies and responses to welfare reform with the implementation of the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) program, which is being met with great concern by many Native American tribal leaders and health care providers (Goldsmith, 1996).

ORIENTING CONCEPTS TO INDIAN MEDICINE

In a report to the National Institutes of Health, Alternative Medicine: Expanding Medical Horizons (1992), the Lakotas (Sioux tribe) were cited for the use of healing ceremonies by specialists who are essentially shamanic in their approach to treatment.(The use of the term shamanic for Native American healers is not ethnographically precise because the term was coined for the peoples of Trans-Siberia, notwithstanding the Bering Strait land bridge of the Ice Age.) Although the report cites key ceremonies and practices used by healers and helpers, the report shows a number of important inaccuracies in addition to the use of the term shaman, which now has been perpetrated throughout the CAM community. To understand Indian medicine ways, one cannot rely solely on written accounts. Although written ethnographical studies may provide a wealth of descriptive data, it is best to talk to authoritative sources personally.

Although the sweatlodge, Sundance, and vision quest are all used by Lakotas for health, help, and healing, not all were always conducted by “medicine women” or “medicine men.” The report tends to project an exclusivity of these ceremonies, when in fact there is considerable variation and scope for these practices, most of which were family oriented (Douville, 1997b).

The sweatlodge or “purification ceremony,” for example, is very common and may be conducted by anyone who has “been on the hill” or completed the hanbleceya, often called the vision quest (Figure 35-5). Although the English name emphasizes the physiological reaction of the sweat, this ceremony of the common man (Lakota ikce wicasa), it is really an encounter with one’s spiritual self and one’s spirit relatives. This is a purification that “gives life” (inipi’kogapi, “that which gives life”) to the participants and represents a form of rebirth. It is a family-oriented ceremony and is an integral part of all other Lakota ceremonies. Participants enter a small lodge made of willow saplings (for support) and covered with heavy, darkening canvas. Between 7 and 16 or more red hot stones are brought into this little lodge, which can be 10 to 15 feet in diameter. The stones represent the “first creation” and have deep spiritual meaning in this ceremony. Water is poured over the stones by someone who is permitted to conduct this ceremony, and the steam from this generates intense heat. There is deep spiritual significance to this.

Family members usually participate in this ceremony on a regular basis. Often, sweatlodges are located behind people’s homes. There is a prohibition that excludes menstruating women from ceremonies out of respect for the ceremony the woman’s body is undergoing (i.e., menstruation, which is seen by Lakota people as a purification with its own proper spiritual power). This is often viewed by white culture as discriminatory, but the tradition is not intended to be discriminatory. It is an affirmation of the natural feminine power, which white culture tends to minimize, often viewing menstruation as a handicap or a problem (e.g., premenstrual syndrome).

There are also different types of “medicine” people among the Lakotas. It is difficult to generalize about the diverse functions using the English term “medicine man” or medicine woman.” The Lakotas practiced common medicines that included the use of herbal remedies known to families, whose primary medical care was prevention and geared to building up the immune system (Douville, 1997b). The various common medicines included teas, ointments, and smudging (smoke from burning certain herbs, such as prairie sage or “flat cedar”). This first line of medical care was performed by knowledgeable family members or friends. When required, more spiritual consultations were sought from a shaman medicine man or an interpreter for the wakantanka (the great mystery in all creation), which represents sacred medicine.

A “ceremony” could be requested by the patient and was usually held at night with family members, close friends, and singers (see Figure 35-3). Usually the patient presented a sacred pipe to the medicine man, who would smoke it if he accepted the request. The ceremony (which was usually described as a lowanpi or a spirit ceremony) took place in a darkened room in the home. All furniture was removed, and the windows were covered. Certain ceremonial objects were used (e.g., various-colored flags, tobacco offerings, earth). During the ceremony, the spirits instructed the medicine man or interpreter on what remedies would be provided by Unci Maka (Grandmother Earth) to heal the patient. This process was done with the support of the tios’paye, or the extended family, for the wicozani (good health) of the patient.

Along with these practices, family members actively participated in a ceremonial life that revolved around the wo’ope, or natural law of creation, which included the behaviors and attitudes for right living. The wo’ope is embodied in the philosophy of mitakuye oyas’in, which recognizes that all things, persons, and creations (both animate and inanimate, seen and unseen) are related (White Hat, 1997). These laws were not written down; they were learned through observing the creation. These behaviors for right living were reinforced by the ceremonial life of the extended family system, or tios’paye.

Health care was primarily an extended family matter. Medical care was common and free to everyone who needed it, because the herbs or materials for ceremonies used natural elements that could be harvested from nature’s bounty. Although medical care was “free,” it was not provided without cost, because in Lakota philosophy, when someone gives you something, you are expected to return it at fourfold the value. When treated by healers, the people who received help gave something back. The concept of receiving “something for nothing” is not part of Indian philosophy (White Hat, 1997). The Lakota philosophy encourages self-reliance and mutual relations. Something changed when white man’s medicine became institutionalized in the United States, emphasizing intervention over prevention, the individual over the tribe or extended family, materialism over spirituality, and the physical body-self over the spirit-body-self.

TRENDS IN CONTEMPORARY INDIAN MEDICINE AND HEALTH CARE

Today, many of the old Indian healing traditions are experiencing a renaissance and are beginning to be viewed with a renewed sense of respect and credibility as an alternative and complement to more invasive or secular Western medical models of treatment (Alternative medicine, 1992; Hall, 1985, 1986; Thin Elk, 1995a, 1995b, 1995c). For example, on the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation at Eagle Butte, the tribal council approved alcohol treatment programs and delinquency prevention programs based on traditional methods and approaches to helping people with alcoholism, viewed as a problem with social, emotional, physical, and spiritual dimensions (Red Dog, 1997). These traditional methods include the inipi, or purification ceremony (popularly called the sweatlodge); the hanbleceya, or pipe fast (vision quest), and the wi’wang wacipi, or the gazing-at-the-sun dance (Sundance). The infusion of these ceremonies within the treatment process, collectively, has been called the Red Road approach (Thin Elk, 1995a, 1995b, 1995c).

A number of medical facilities on various reservations include medicine men as consultants on a formal and informal basis (M Clifford, 1997; Douville, 1997a; Erickson, 1997; Twiss, 1997), and the use of traditional ceremonies in health care settings is encouraged and respected (Erickson [Rosebud Indian Health Services Hospital], 1997; Richards [Rapid City Regional Hospital], 1997). Although the ceremonial burning of sage (a common medicinal herb burned for purification) had been discouraged in the past, hospital staff report increased acceptance of this practice and now arrange appropriate space for traditional ceremonial practices both within the health care facility and outside on hospital grounds (Erickson, 1997; Richards, 1997). One Lakota friend commented on his recent hospitalization at an allopathic hospital. He was visited by a medicine man, who placed a bundle of sage under his pillow. This made him feel better and showed how simple cooperation can be between allopathic medicine and alternative health care practices.

Rapid City Regional Hospital has initiated a Diversity Committee to discuss cultural sensitivity in both employee-administration and staff-patient relationships and credits this committee for improved retention rates of Indian staff (Montgomery, 1997). The Diversity Committee, which meets monthly, provides an opportunity to identify areas of cultural awareness, tension, and misperception, so that understanding across cultures can take place. Conflicts in cultural views and values are inevitable, but there are growing opportunities for understanding and joint efforts.

Mike Richards, discharge planner and liaison with the tribes at Rapid City Regional Hospital, noted one situation in which a Lakota client was discharged to his extended family. The plan was for the child to live in a tent in the backyard. This plan was challenged by the state social services department, which failed to recognize that it is not uncommon for Lakota children to share close space in the family home or home of a relative. During my visits and stays with Lakota friends, I might see many children from an extended family share a small space in the family dwelling or occupy outbuildings or tents on the family compound or community (tios’paye) during the summer months. Although this practice might be considered inappropriate based on middle-class white standards, it affirms the Lakota value of close kinship bonds and enjoyment of children and illustrates the “bifurcating-merging family structure,” a traditional Lakota kinship structure that considered parallel family relationships (e.g., one’s aunts and uncles as “mothers” and “fathers”). Close kinship among all family members was reinforced by this family structure, whereby households and family resources were shared generously (Douville, 1997a; Driver, 1969).

The mental health liaison to the tribe advocated the child’s return to his extended family, and the plan was eventually approved. This case illustrates how simple cultural misunderstanding can occur when service delivery is not centered on the values, family system organization, and beliefs of the traditional Indian perspective. Further illustrating this cultural insensitivity at a structural level is the fact that reservation housing financed by U.S. Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grants is assigned on a lottery basis and “invents” communities that are not based on natural, extended family relationships. This social invention (i.e., building housing developments and populating them on the basis of governmental criteria) often conflicts with the natural, familial basis of the tios’paye, or extended family system, of Lakota people (Lunderman, 1997). Such practices undermine the natural sense of community among Indian people and unwittingly create community tensions.

There is active cooperation between medical practitioners and traditional medicine men on Lakota reservations. Referrals are made both ways; medicine men will refer patients to medical doctors when they have exhausted their repertoire of remedies, and medical doctors will refer to medicine men when they have exhausted their treatment repertoire. The relations between traditional and medical health care providers appear cooperative and fluid. Antagonism between these distinct and complementary approaches to health care has subsided somewhat, although suspicions toward Western approaches to medicine remain among some traditional Indian people, which is understandable.

Whereas traditional Western psychiatric thought has emphasized the mechanics of the mind, traditional American Indian philosophy looks at the natural flow of the individual’s spirit-body-mind-self in relation to “everything that is.” The Lakota term mitakuye oyas’in is often heard during ceremonies, reminding and reaffirming the participants of their relationships to ancestral spirits, powers, and energies of creation and to their kinship relatives, or tios’paye, the extended family and community. All these elements are considered essential for wicozani, or good health. The notion of mitakuye oyas’in is consistent with family systems theory that examines the impact of intergenerational family dynamics on the present functioning of family members.

Shamanic traditions and healing practices are very active among traditional American Indians today and seem to be gaining ground after generations of official and unofficial prohibitions and sanctions. There is diversity among traditional Indian tribal practices. The Lakotas have been open and receptive to sharing knowledge and technology with other nations. Lakota medicine people rely on their spirit helpers to “give them permission” to treat people and conduct ceremonies (Holler, 1995; Little Soldier, 1997; Smith, 1987; Twiss, 1997). This permission is very specific; for example, a medicine man may be instructed to use certain herbal medicines for men only, women only, or people in general. The spirits work through the healer. The medicine man is only as effective as the spirits working through him. He is responsible and accountable to the spirits for everything. This is a serious responsibility that these healers accept.

Although many similarities exist in approaches to health and healing practices among American Indian healers (e.g., emphasis on prevention, involvement of family and community in healing ceremonies), important differences must be taken into consideration as well when treating American Indians. The best advice is for the health care practitioner to ask patients about their traditional practices, assuring them that the practitioner may not understand all their cultural traditions but that he or she is interested in learning about these practices and, perhaps most importantly, is willing to work in a collaborative way that incorporates traditional healing practices without dismissing them. Individuals who use traditional methods of help and healing need to sense that their traditions will be respected when they seek medical care in mainstream medical facilities, or they may not accurately inform their physicians about what traditional measures and remedies they are using to restore health, balance, and healing in their lives (Lunderman, 2004).

One of the most important trends in Indian health care today may be the concern about the impact of welfare reform on Indian peoples, along with the widespread tendency of individual states to reduce welfare rolls and move Medicaid services under managed care providers. An article in the Journal of the American Medical Association noted that American Indians know a lot about government program reforms. “If some people had had their way, Native American tribes would have been reformed out of existence a century ago. So it’s not surprising that members of some 500 federally recognized tribes that remain are wary when talk in their locality turns to ‘health care reform’” (Goldsmith, 1996, p. 1786).

At present, the Indian Health Service (IHS), a federally administered Indian health care program that is accredited by the Joint Commission (formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, or JCAHO), is facing severe budget deficits, overall receiving only 50% to 75% of what it needs to operate (Goldsmith, 1996, p. 1787). At the same time, IHS director Michael H. Trujillo, MD, MPH, reported that the service population has increased by more than 2% per year. Although there have been increasing federal appropriations for IHS over the years, the actual amount of “real money” has gone down. For many Indian people, the IHS is the only medical provider in their often-remote areas, serving a population with disproportionately higher incidence rates of diabetes and cervical cancer, for example, than the general American population. In the context of anticipated health care reform, Dr. Gerald Hill, the director of the Center for American Indian and Minority Health in the Institute for Health Services Research at the University of Minnesota, reminds health care planners of the statistic that, in the American Indian population, 31% of the people die before their forty-fifth birthday (Goldsmith, 1996). Indian health care remains at a critical crossroad. Trends in Indian Health 2000-2001 (IHS, 2004) reports that the age-specific death rate for American Indians and Alaska Natives from 1996 to 1998 was more than double the U.S. white rate in 1997 for the age groups 1 to 4 years and 15 to 54 years. Interestingly, the only age group with a lower death rate than the U.S. white rate was the 85 and older group (p. 70). Recent evidence provides some reason for optimism in that the overall death rate for American Indians and Alaska Natives for individuals under 45 years of age was 28% during 1996 to 1998 (p. 72).

QUESTIONS FOR FURTHER DISCUSSION

In light of the growing interest in and expanding practice of traditional healing methods across American Indian communities, a number of questions deserve further study. First, it is important to note that, in raising these questions, the authors recognize the complex cultural context in which these questions are framed as they straddle the divide between Western diagnostic categories that relate to empirical facts and traditional methods of healing that relate to the subject’s belief system and spiritual practices. Thus, what is being questioned here is not traditional spirituality, but the specific medical implications of certain physical activities, often part of the spiritual healing practices. These questions are raised for both Western health care practitioners and traditional healing practitioners to consider as both seek continuing understanding in promoting good health among all people.

Because diabetes is a leading cause of death among American Indian people, 291% greater than the U.S. mortality rate for all races (IHS, p. 7), the question is raised as to the effect of moderate, sustained, or prolonged fasting from food and water on the renal system. Some traditional healing practices, such as the hanbleceya (pipe fast, vision quest) and the wi’wang wacipi (Sundance), involve fasting from food and water from 1 to 4 days, and we still do not know the long-term effect of such practices on renal functioning. Traditional Indian people differentiate physical healing and spiritual healing; sometimes both occur during a ceremony, and at other times a spiritual healing may take place without a physical cure. A powerful example of this is the sobering account reported by Archie Fire Lame Deer (1992, pp. 186-188), in which a man with diabetes died while on a vision quest, having fasted without food or water for 4 days. Lame Deer noted, “Ron’s autopsy showed that, besides diabetes, he had been suffering from three other deadly conditions. He had already been in the process of dying when he went to the mountain to leave this world in prayer” (p. 186). In this case, the individual faster was advised to take his insulin during the vision quest, but as Lame Deer later reports, “He had not touched his insulin.”

Although this case may represent a rare occurrence, researchable questions can be asked, such as, What are the physiological effects of such prolonged fasts on individuals with early, middle, and advanced stages of diabetes? Because practices vary among traditional healers in the use of fasting, other questions could focus on the effects on the individual faster of complete or absolute fasts, partial fasts from sundown to sundown, and partial fasts that include some liquid nourishment (e.g., herbal teas, medicines). It would be interesting to know which of these practices offers the best opportunity for physiological healing or cure. Some might argue that such inquiry is not appropriate for, or perhaps even disrespectful to, traditional healing practices. However, the authors also note the long tradition of holding so-called medicine men (and women) accountable to demonstrate their power in public ways before the tios’paye, or extended family or community. For example, the test of a true heyoka (medicine man) has been the demonstration of plunging his hand into a boiling hot kettle and pulling out the medicine for the people. This ceremony was (and is) conducted publicly and in full daylight. The witnessing community attests to the power and truth of the heyoka, so there are precedents for such demonstrations of efficacy among traditional healers.

Another aspect of these questions is to challenge any romanticized notion or exploitation of traditional healing, particularly among or by non-Indians, who may attempt to engage in such healing practices without the appropriate guidance or understanding. This is an extremely serious concern among genuine traditional practitioners and healers, and it has been repeatedly raised as an issue by the elders, traditional spiritual leaders, and others.

Ayahuasca: Master Healer of the Forest

The first time I drank ayahuasca I went into complete catharsis. I lost all track of time and I lost all control over my thoughts. Visions began to appear. I was suddenly about 5 years old experiencing very real traumatic childhood memories. Ayahuasca is said to completely shut down your conscious mind and take you directly to whatever issues may lurk in your subconscious mind. Ayahuasca took me straight to the deepest, darkest, most painful corners of my subconscious mind. All the dull, aching childhood memories that have shaped my life and that I have carried with me for so many years came back alive and came to pass.

My experience was extremely painful. I cried and screamed as I relived my past. As time seemed so altered, years and years of my childhood and young adult life passed in those few hours of the ceremony. . . . I definitely died on some level during my experience. I released so much pain that finally I was empty. I cried out, “I don’t want to live! There’s nothing left for me! Life is too hard!” With the release of the past I felt empty and lost. Physically, I became uncomfortable.

Drinking ayahuasca is said to be a purging experience. It is almost inevitable for people to either vomit or have diarrhea. I had the latter. However, after I physically purged, my experience became easier. My purge on the physical level mirrored my purge on the spiritual level. I suppose it was my higher self that kicked in right after my purge. Suddenly there was a voice in the back of my head telling me, “You can do this. You have the power now. You can live your life and find your happiness.” All of the horror had passed and I was free. A burden had been lifted. At four or five in the morning the day after the ceremony, when the sun was beginning to come up, I finally snapped out of my trance. I was back to reality, feeling quite empty and lost. The next day, and the next few weeks for that matter, would be about processing my experience. I think the ayahuasca brought my life into perspective, helping me release old wounds and gain my power, and leading me closer to my life’s purpose.

Writing about my ayahuasca experience is difficult. It is hard to explain how a little bit of tree bark can liberate a person from so much pain. As far as my journey goes, ayahuasca was a positive healing experience, but only the tip of the iceberg. . . . Shamanism and ayahuasca, I believe, are incredible healing mechanisms. My trip to Peru opened my eyes. There is so much wisdom in the trees and plants of the earth. (Personal communication from an ayahuasca patient and colleague, December 2008)

The preceding account of a personal experience with an ayahuasca ceremony told by a colleague is very similar to an account given by Kira Salak (n.d.), whose experience with an ayahuasca ceremony in Peru was videotaped by a National Geographic Channel film crew and published as a video exclusive in National Geographic Adventure magazine.

Field Research with Indigenous People on the Tambopata River, Peru

This author learned about the ayahuasca ceremony from a number of sources, including actual interviews with shamans who were active practitioners, patients who had positive experiences with the healing ceremony, and a patient who went to a “bad shaman” and “got lost” in the healing experience; an unpublished article, “Ayahuasca-Wasi: Proyecto de Investigación Shamánico Transpersonal” (n.d.); and Professor Mustalish, director of the Amazon Center for Environmental Education and Research.

First of all, it was clear that the “master healer” was the vegetation—the forest plants (including woody vines, tree bark, and herbs) that are boiled together to produce the ayahuasca, which is taken by both shaman and patient. The ayahuasca forms the spiritual pathway or the connection (“la conexión mágico-espiritual”) between the patient and the shaman that enables the healing to take place. The ayahuasca is a hallucinogen that often acts as a purgative and may cause vomiting and/or diarrhea; it is viewed as both a medicine and a cleansing agent. The concoction produces vivid hallucinations that reflect the power of the healing.

The ayahuasca ceremony takes place at the shaman’s house, which is often located in the middle of the forest. The use of the cha’pa’ka (a rattle made from the leaves of certain forest plants tied together at the base, which forms the handle) is significant in this ceremony. According to a shaman, the shaking of the cha’pa’ka awakens the spirit of the leaves, and the sound (the songs) produced by the movement of the leaves makes the shaman and patient dizzy. The shaman then begins to dance with the shaking of the leaves. The sound of the cha’pa’ka also helps keep the patient from getting lost while experiencing the effects of the ayahuasca. It is the sound of the shaking leaves that helps the patient stay connected to the shaman during the ayahuasca ceremony. If one takes the ayahuasca medicine alone (without a shaman present) one can become lost or lose control. A real shaman provides control during the ceremony while the ayahuasca helps the patient to see his or her dreams. When the question was asked, “How does one know a real shaman from a fake shaman?” the answer was that the ayahuasca shows you this, “You see who the shaman really is.” Of course, the outcome here can be either reassuring or devastating depending on the findings of the patient.

Clinical Applications

Clinical applications of ayahuasca are currently being studied by Jacques Mabit, director of the Centro de Rehabilitación de Toxicomanos (Rehabilitation and Detoxification Center) at Takiwasi Center, Peru. Mabit combines the traditional use of ayahuasca with psychotherapy techniques and holistic methods (consciousness-expanding techniques such as fasting, hyperventilation, and use of nonaddictive plants), largely in the treatment of coca paste addiction. The center is funded by the French government. Conventional allopathic medicines are not used (except in unusual circumstances).

Physical detoxification is accomplished through the use of medicinal plants. Conventional Peruvian approaches to addiction treatment are based on prison or military models, which have raised human rights concerns among health care workers.

All studies of the clinical use of ayahuasca have European or South American sponsorship, and the results of most are published in Spanish (Mabit, 1995; http://www.unsm.edu.pe/takiwasi).

Healing Ceremony

Although this author did not participate in an ayahuasca ceremony, when he asked one of the shamans interviewed to demonstrate a typical song used in the ceremony, the author was invited back to the shaman’s one-room house later that evening. After a friendly conversation, the author was invited to sit on the edge of the bed as the shaman actually performed a healing ceremony on the author. The author was sprinkled with rose water as the shaman began to sing. The song itself sounded more like a bird’s whistle. Smoke from a hand-rolled tobacco cigarette was also blown on the author at various times during the ceremony. The cha’pa’ka (leaf rattle) was used and proved to be a very significant part of the ceremony. As noted earlier, the cha’pa’ka is a bunch of leaves tied at the base to form a handle. The “rattle” results from the sound of the shaken leaves. At one point the author recalls the cha’pa’ka being shaken over his entire body and then focused on his head, and as the rattle continued the author had an overwhelming sensation that the entire forest was dancing around him, and the small cha’pa’ka made it feel like all the vegetation in the forest was singing and dancing in a much larger cosmic ceremony. Now this is quite remarkable, because ayahuasca was not used during this ceremony, and yet the effect of the ceremony was still quite magical.

Songs Used in the Ayahuasca Ceremony

Although the circumstances precluded taping of the healing songs being sung during the author’s own healing experience with the shaman, the author did find a collection of songs used in the ayahuasca ceremony. The author reviewed Senen Pani Antonio Muñoz’s collection of ayahuasca songs recorded on the music CD entitled, Bewa Icaro, Songs of Preparation (2005). As in the peyote ceremony of the Native American Church, there are songs used while the ayahuasca is being prepared for the ceremony followed by the actual healing songs (elevation songs), which are used during the central action of the ceremony. Two songs from the Muñoz collection (2005) are included here:

I am the son of old Metsarawa, my name is Senen Pani and my wife is Raipena. Tonight I will take ayahuasca so that I can see the body of each one of you; with flower water I will blow on you.