CHAPTER 1 CHARACTERISTICS OF COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE

This section provides an introduction to the whole topic of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), its themes and terminology, and the various contexts relative to its proper interpretation. In addition, this section addresses issues in so-called “integrative medicine,” which represents the attempt to bring legitimate CAM therapies into the continuum of mainstream healthcare. The chapters provide a social and cultural recontextualization of CAM. The ubiquitous use of plants and natural products among alternatives is introduced through underlying themes from both the social and the biological sciences.

As introduction to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), these chapters discuss social and cultural factors, an integrative medical model, and global dimensions of CAM practice. Also, the social history of the use of CAM is introduced through the concept of “vitalism” in intellectual and medical discourse, which is important to the understanding of the common themes of bioenergy and self-healing in the following Section Two.

The different medical systems subsumed under the category complementary and alternative are many and diverse, but these systems have some common ground in their views of health and healing. Their common philosophy can be called a new ecology of health, sustainable medicine, or “medicine for a small planet.”

ROLE OF SCIENCE

Allopathic medicine is considered the “scientific” healing art, whereas the alternative forms of medicine have been considered “nonscientific.” However, perhaps what is needed is not less science but more sciences in the study of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Some of the central ideas of biomedicine are very powerful but may be intellectually static. The study of dead tissue cells, components, and chemicals to understand life processes and the quest for “magic bullets” to combat disease are based on a reductionist, materialist view of health and healing. Tremendous advances have been made over the past 100 years by applying these concepts to medicine. However, the resulting biomedical system is not always able to account for and use many observations in the realms of clinical and personal experience, natural law, and human spirituality.

Contemporary biomedicine conceptually uses Newtonian physics and preevolutionary biology. Newtonian physics explains and can reproduce many observations on the mechanics of everyday experience. Contemporary quantum physics (quantum mechanics) recognizes aspects of reality beyond Newtonian mechanics, such as matter-energy duality, “unified fields” of energy and matter, and wave functions (see Chapters 10 and 11). Quantum physics and contemporary biology-ecology may be needed to understand alternative systems. Nuclear medicine uses the technology of contemporary physics, but biomedicine does not yet incorporate the concepts of quantum physics in its fundamental approach to human health and healing. Contemporary biomedicine measures the body’s energy using electrocardiography, electroencephalography, and electromyography for diagnostic purposes, but it does not explicitly enlist the body’s energy for the purpose of healing.

The biomedical model relies on a projection of Newtonian mechanics into the microscopic and molecular realms.

As a model for everything, Newtonian mechanics has limitations. It works within the narrow limits of everyday experience. It does not always work at a macro (cosmic) level, as shown by Einstein’s theory of relativity, or at a micro (fundamental) level, as illustrated by quantum physics. However useful Newton’s physics has been in solving mechanical problems, it does not explain the vast preponderance of nature: the motion of currents; the growth of plants and animals; or the rise, functioning, and fall of civilizations. Per Bak once stated that mechanics could explain why the apple fell but not why the apple existed or why Newton was thinking about it in the first place.

Mechanics works in explaining machines. But no matter how popular this metaphor has become (with acknowledgment of National Geographic’s popular “incredible machine” imagery), the body is not a machine and it cannot be entirely explained by mechanics. It is becoming increasingly clear that an understanding of energetics is required. This duality between the mechanical and the energetic has been accepted in physics for most of the past century. This duality is famously illustrated by the fact that J. J. Thomson won the Nobel Prize for demonstrating that the electron is a particle. His son, George P. Thomson, won the Nobel Prize a generation later for demonstrating that the electron is a wave.

“Hard scientists,” such as physicists and molecular biologists, accept the duality of the electron but sometimes have difficulty accepting the duality of the human body. The “soft sciences,” which attempt to be inclusive in their study of the phenomena of life and nature, are often looked on with disdain according to the folklore of the self-styled “real” scientists. However, real science must account for all of what is observed in nature, not just the conveniently reductionistic part.

The biological science of contemporary medicine is essentially preevolutionary in that it emphasizes typology rather than individuality and variation. Each patient is defined as a clinical entity by a diagnosis, with treatment prescribed accordingly. The modern understanding of the human genome does not make this approach to biomedical science less preevolutionary. Both the fundamentals of inheritance (Mendel) and those of natural selection (Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace) were explained long before the discovery of the structure of the gene itself. Although modern biology-ecology continues to explore the phenomena of how living systems interact at the level of the whole—which cannot be seen under a microscope or in a test tube—molecular genetics continues to dissect the human genome.

It may seem outrageously complex to construct a medical system based on the concepts of modern physics and biology-ecology while maintaining a unique diagnostic and therapeutic approach to each individual. This would indeed be complex if not for the fact that the body is its own entity, a part of nature, and each body has an innate ability to heal itself.

One way of studying and understanding alternative medicine is to view it in light of contemporary physics and biology-ecology and to focus not just on the subtle manipulations of alternative practitioners, but also on the physiological responses of the human body. When homeopathy or acupuncture is observed to result in a physiological or clinical response that cannot be explained by the biomedical model, it is not the role of the scientist to deny this reality, but rather to modify our explanatory models to account for it. In this way, science itself progresses. In the end there is only one reality. Integrative (or alternative) medical systems, which are relatively “old” in terms of human intellectual history, always have been trying to describe, understand, and work with the same reality of health and healing as biomedicine. Whereas contemporary biomedicine uses new technologies in the service of relatively old ideas about health and healing, alternative methods use old technologies whose fundamental character may reflect new scientific ideas on physical and biological nature (Boxes 1-1 and 1-2).

BOX 1-1 A Note about Nomenclature

Although the term complementary and integrative medicine (CIM) was used in the third edition, complementary and alternative medicine was used in the title of the first two editions of this text to which we now return, no longer a victim of fashion. The word alternative, or the term complementary and alternative medicine, now seems to be culturally encoded in the English language.

Alternative medicine has been used to refer to those practices explicitly used for the purpose of medical intervention, health promotion or disease prevention which are not routinely taught at U.S. medical schools nor routinely underwritten by third-party payers within the existing U.S. health care system.

Such a definition seems to be a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning that alternative medicine is everything not presently being promoted in mainstream medicine. This definition may remind us of a popular song from the 1960s called “The Element Song,” which offers a complete listing of the different elements of the periodic table (set to the tune of “I Am the Very Model of a Modern Major General” from Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance). It ends with words to this effect: “These are the many elements we’ve heard about at Harvard. And if we haven’t heard of them, they haven’t been discovered.” I have likened the recent “discovery” of alternative medicine to Columbus’s discovery of the Americas. Although his voyage was a great feat that expanded the intellectual frontiers of Europe, Columbus could not really discover a world already known to millions of indigenous peoples who had complex systems of social organization and subsistence activities. Likewise, the definitional statement that alternative forms of medicine are not “within the existing U.S. health care system” is a curious observation for the tens of millions of Americans who routinely use them today.

BOX 1-2 Complementary and Alternative Medicine on the American Frontier, 1492-1942

Among the early exchanges to occur between European explorers (then settlers) and Native Americans were diseases and medical treatments. In the New World, Europeans were not surprised to find Native American remedies effective in light of the sixteenth-century “law of correspondences,” which held that remedies could be found in the same locales where diseases occur. In the New World most Europeans, and thence Americans, found themselves for most of history from 1492 until as late as 1942 on the frontier where there was often no doctor. And often that was not such a bad thing.

Native Americans also readily adopted “big medicine” from European “physick” and early surgical practices as well, from the early Spanish conquistador Cabeza de Vaca (1530), eventually taking the French word for physician (médecin) and incorporating it into their own languages to express something previously unknown.

Europeans were in turn impressed by Native American resort to the healing power of nature and to spiritual healing. Nature in the New World provided a bounty of new medicinal plants and foods (whereas in Europe there had been only 16 cultivars—before chocolate, corn, squash, tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, and other foods of the Americas). In the English colonies beginning at Jamestown (1607) herbs, such as sassafras, were readily adopted. In Pennsylvania, William Penn (1680) himself became well acquainted with native herbs and other healing-spiritual practices such as the sweat lodge of the Delaware Indians (see Chapter 36).

Many of the earliest books to come out of the English colonies were natural histories, serving as “herbals,” that documented the occurrence of medicinal plants in various parts of the colonies: John Josselyn (1671) on New England, and John Lederer (1670), Robert Beverley (1705), John Lawson (1709), and John Brickell (1737) on Virginia and the Carolinas. John Wesley, later founder of the Methodist Church in England, wrote a similar book on Georgia (1737) during his two-year service as chaplain in Savannah. These regions are very biodiverse with many plant species because they represent the southern edge of the most recent geologic glaciations (see Chapter 4).

Later the best known of such herbal chronicles was Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, etc. by William Bartram, professor of botany at the College of Philadelphia (later, the University of Pennsylvania) who was consulted by Lewis and Clark prior to their own travels. (Bartram’s Travels is the one book carried by the fictional Civil War character Inman—not only for its practical value but because “it made him happy”—in his journey to Cold Mountain in the 1997 landmark novel of the same name by Charles Frazier).

Physicians were rare on the expanding frontier, which prevented “regular medicine” (such as bleeding by lancet, leeches, and cupping; and blistering, puking, and purging—of which Francis Bacon had said, “The remedy is worse than the disease”) from taking root where there were effective natural and home remedies. The American “self-help” book first took hold on the frontier with the publication in 1734 of Every Man His Own Doctor, Or, The Poor Planter’s Physician by John Tennent of rural Spotsylvania County, Virginia, describing many native American herbal remedies. The potent American ginseng of Appalachia quickly became an international commodity with exportation to China. Frontiersman Daniel Boone for a time earned a living as a “sanger,” gathering the herb in the wild.

Perhaps the most popular self-help book of all was Gunn’s Domestic Medicine, or Poor Man’s Friend, by Dr. John C. Gunn of Knoxville, Tennessee, continuously in print from 1830 to 1920. It is mentioned, for example, in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn (1885) and in John Steinbeck’s East of Eden (1952).

In 1774, the leading American physician, Benjamin Rush (see Chapter 22), published a treatise on the importance of Native American remedies, and he later advised Lewis and Clark in 1803. Amazingly only one man died on the expedition, which implied that nature was a healthier place than Civilization. Charles Dickens described the unhealthy conditions of “civilized” areas in grim detail in his American Notes (1842). The “west cure, rest cure, and nature cures” became recommended means of recuperating from the illnesses of nineteenth-century civilization. This cure was used to good effect by future President Theodore Roosevelt, for example.

Other journeys of exploration expanded the frontier and the reach of frontier medicine, including those of Zebulon Pike (1806; before Lewis and Clark had even returned), Hugh Campbell (1833; with Dr. John Scott Harrison, who was son of President William Henry Harrison and father of President Benjamin Harrison and who died of alcoholism just prior to his father’s election in 1840), John C. Frémont (1836-1848), and John Wesley Powell (named for the aforementioned Methodist minister), sometimes accompanied by colorful “mountain men” like Jedediah Smith, Jim Bridger, and Kit Carson.

Andrew Jackson’s election in 1828 had provided a second American revolution with the ascendency of the common man along with his medicines. A backlash against the regular medicine of the elites was accompanied by the formal organization of natural healing by Samuel Hahnemann (see Chapter 24), Samuel Thomson (see Chapter 21), Franz Joseph Gall, and later John Harvey Kellogg (see Chapter 21). By the middle of the nineteenth century, the natural remedies of frontier medicine represented a well established and widely available form of health care in America.

During the Civil War, after the Union naval blockade of the South began working in 1862, the Confederacy found it difficult to obtain manufactured medicines and turned to natural remedies, publishing a pamphlet listing native herbs that could be used for treatment: snakeroot, sassafras, partridgeberry, lavender, dogwood, tulip tree, and red and white oak. Confederate Medical Corps kits contained many of these remedies toward the end of the war. After the Civil War came the heyday of patent (herbal) remedies, including Dr. Pepper, Dr. John Pemberton’s Coca-Cola, and Dr. Hire’s Root Beer, still enormously popular today as “soda,” “pop,”“ tonic,” and “root beer.”

The term quacks (from the German quacksalver “quicksilver” or “mercury,” which was actually a toxic regular medical treatment of the time) began to be applied to the practitioners of natural remedies (considered useful on the American frontier from the 1500s to the 1850s) suddenly at about the time the American Medical Association was organized in 1847—in reaction to the formation of the American Homeopathic Association in 1842.

Physicians and scientists who made real health advances with the use of natural healing in the mid- to late-nineteenth century (Thomson; Vincent Priessnitz [the water cure]; Russell Trall [the nature cure]; Nikola Tesla, pioneer of electromagnetism) were rounded up in the judgment of twentieth-century history together with true charlatans like Thomas Alva Edison, Jr. (son of the inventor, who did his best to put Tesla, the true genius of electricity and bioenergy, out of business), John Romulus Brinkley, Dr. C. Everett Field, and Norman Baker. This label came to include hypnotists and “magnetic” healers (e.g., Franz Anton Mesmer) and the emerging manual therapists (e.g., Andrew Taylor Still, Daniel David Palmer) of the nineteenth century who originated in and were also initially a phenomenon of the rural frontier. In retrospect, the exploits of nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century charlatans seem quaint in comparison with the organized havoc wreaked on the public health during the last quarter century by the drug and insurance industries.

The great unexamined assumption for today’s reader is that natural healing in the later nineteenth century became “quackery.” This attitude betrays something of a triumphalist approach to the wonders of twentieth-century medicine, whereas twenty-first-century American medicine in many ways has become nothing to celebrate. The vast majority of Americans were once able to leave “frontier medicine,” for two or three generations, and enjoy medical practice and health care marked by well-trained physicians they knew and trusted, and the widespread availability of compassionate health services in hospitals that were accountable to their own communities. In the twenty-first century Americans now subsidize and sustain with hundreds of billions of dollars each year (16% of gross domestic product—the largest share in the world, but resulting in only the fortieth best health status among nations) a largely ineffective, inequitable, unsustainable health care system for the benefit of an unaccountable corporate-government-research complex of vested interests—marked by the arrogance and intransigence of mainstream biomedical research elites, excessive corporate profiteering through “blockbuster” drugs and direct-to-consumer marketing (rather than true therapeutic breakthroughs), and the mirage of “biotech” cures, as well as the substitution of hard-won medical knowledge and clinical judgment by insurance company bureaucracies that results in withholding of care and health care rationing (ironically, that which had been the greatest fear under the “socialized medicine” of a single-payer system). For several decades many have awaited the next “miracle” drug, biotech breakthrough, and, now, medical information technology for solutions to our health care crisis. This book illustrates that often it is ancient knowledge and wisdom about healing that, when adapted to new circumstances, provide truly innovative approaches to health problems.

In today’s economy, the health care crisis is rapidly moving toward collapse. Many Americans may find themselves back on the medical frontier, where fortunately the natural healing and remedies once spurned (including some in this book) are still abiding in the contemporary consumer movement labeled as “complementary/alternative medicine.”

If biomedicine cannot explain scientific observations of alternative medicine, the biomedical paradigm will be revised.

Science must account for all of what is observed, not just part of it. That is why physics has moved beyond Newtonian mechanics—biology beyond typology. Is it possible for a biomedical model to be constructed for which its validity includes observations from CAM? Although it may be necessary to wait for new insights from physics and biology to understand CAM in terms of biomedicine, clinical pragmatism dictates that successful therapeutic methods should not be withheld while mechanisms are being explained—or debated. We live in a world filled with opportunities to observe the practice of integrative medicine; all that remains is to apply scientific standards to its study. In the meantime, patients are now waiting for mainstream physicians to understand the mechanisms of CAM. Also, we can come to understand the underlying intellectual content and history of alternative forms as complete systems of thought and practice.

WELLNESS

The CAM systems generally emphasize what might be called “wellness” by the mainstream medical system. The goal of preventing disease is shared by integrative and mainstream medicine alike. In the mainstream medical model this involves using drugs and surgery to prevent disease in those who are only at risk, rather than reserving these powerful methods for the treatment of disease. I have called this trend the medicalization of prevention. In this approach, one can continue to engage in risky lifestyle behaviors while medicine provides “magic bullets” to prevent diseases that it cannot treat. Wellness in the context of complementary medicine is more than the prevention of disease. It is a focus on engaging the inner resources of each individual as an active and conscious participant in the maintenance of his or her own health. By the same token, the property of being healthy is not conferred on an individual solely by an outside agency or entity, but rather results from the balance of internal resources with the external natural and social environment. This latter point relates to the alternative approach that relies on the abilities of the individual to get well and stay healthy (Box 1-3).

BOX 1-3 Prevention versus Acute versus Chronic Disease

In Western allopathic medicine careful distinctions are made between modalities for preventing disease, for treating acute disease, and for treating chronic disease.

Because complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities generally address the causes rather than the symptoms of disease, CAM strategies for prevention, for treatment of acute disorders, and for treatment of chronic disorders may often be the same or similar.

Ambulatory CAM Care Versus Residential CAM Care

CAM modalities are now widely available in the United States in both health care and non–health care settings. However, they are generally offered only as ambulatory care. Although there is much that can be accomplished by a CAM practitioner in a clinical setting, ambulatory care clients often experience a “reduced” form of the full potential benefits. Traditional Chinese, Ayurvedic, naturopathic, and other CAM “cures” involve the client’s being “admitted” for residential care in a healthful environment over prolonged periods where all aspects of the client’s experience are directed toward a healing response. Here, for example, diet is part of therapy and not something assigned to institutional food services as in modern hospitals. Although CAM modalities are generally gentler and less potent than modern biomedical technology, the potency of a full residential CAM cure can be remarkable.

SELF-HEALING

The body heals itself. This might seem to be an obvious statement, because we are well aware that wounds heal and cells routinely replace themselves. Nonetheless, this is a profound concept among CAM systems, because self-healing is the basis of all healing. External manipulations simply mobilize the body’s inner healing resources. Instead of wondering why the body’s cells are sick, alternative systems ask why the body is not replacing its sick cells with healthy cells. The body’s ability to be well or ill is largely tied to inner resources, and the external environment—social and physical—has an impact on this ability.

What is the evidence for self-healing? The long and common history of clinical observations of the “placebo effect,” the “laying on of hands,” or “spontaneous remissions” may be included in this category. To paraphrase Carl Jung: Summoned or unsummoned, self-healing will be there. Self-healing is so powerful that biomedical methodology mainly designs double-blind, controlled clinical trials to see what percentage of benefit powerful drugs can add to the healing encounter.

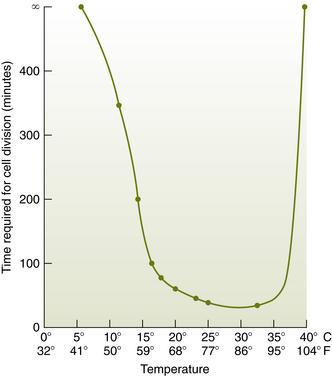

A related concept is that the body has energy (see Chapters 10 and 11). Accordingly, as a living entity, the body is an energetic system. Disruptions in the balance and flow of energy cause illness, and the body’s response to energetic imbalance leads to perceptible disease. Because the body heals itself, the body can also make itself sick. Restoring or facilitating the body to restore its own balance restores health. The symptoms of a cold, flu, or allergy are caused by the body’s efforts to rid itself of the offending agent. For example, by raising the body’s temperature, a fever reduces bacterial reproduction (like an antibiotic, fever is literally bacteriostatic), and sneezing physically expels offending agents (see Figure 1-1 and Chapter 24).

Figure 1-1 Relation between rate of cell division for Bacillus mycoides and temperature.

(Data from Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1954 ed, s.v. “Bacteriology.”)

Pathologists know that there are only so many ways that cells can look sick, because cellular reactions have a defined repertoire for manifesting malfunction. We have also learned a great deal over the past 100 years by correlating the appearance of dead tissue cells under the microscope with clinical diagnosis and prognosis. However, studying dead tissue cells for clinical significance does not allow direct observation of the dynamic energy of living cells, systems, organisms, and communities. Although correlation of the appearance of stained tissue cells under a microscope to clinical conditions is a powerful concept in medicine, alternative forms of medicine appear to provide a path to study the energy of living systems for health and healing, perhaps before the development of overt disease, as so often encountered among the many “functional complaints” in modern medicine (see Chapter 2).

NUTRITION AND NATURAL PRODUCTS

The reliance on nutrition and natural products is fundamental to CAM and does not play merely a supportive or adjunctive role. Nutrients and plant products are taken into the body and incorporated in the most literal sense. They provide the body with energy in the form of calories and with the material resources to stay healthy and get well.

Because the basic plan of the body, as a physical entity and as an energy system, evolves and exists in an ecological context, what the body needs it obtains from the environment in which it grew. Lao Tzu said that “what is deeply rooted in nature cannot be uprooted.” The human organism is designed to obtain nutrients from natural food sources present in the natural environment, and the body is often best suited to obtain nutrients in their natural forms (see Chapter 22).

PLANTS

Plants are an important part of nature relative to health and a dominant part of the nature in which humans evolved. In addition to producing the oxygen that we breathe, plants are seen as sources of nutrients, medicines (e.g., phytochemicals), and essential oils (e.g., volatiles for inhalation and transdermal absorption); some systems also view plants as sources of vibrational energy. Many systems see the use of plants as sources of nutrients in continuity with their use as sources of medicine, paralleling contemporary biomedical guidelines for nutrition as disease prevention. As in Chinese medicine, foods exist in continuity with medicines among plant sources (Boxes 1-4 and 1-5).

Garlic (Allium sativum) has been widely promoted as a remedy for colds, coughs, flu, chronic bronchitis, whooping cough, ringworm, asthma, intestinal worms, fever, and digestive, gallbladder, and liver disorders. Investigators have explored its use as a treatment for mild hypertension and hyperlipidemia, Heavy consumption may lead to lengthened clotting times, perioperative bleeding, and spontaneous hemorrhage. Numerous studies over a long period have documented garlic’s irreversible inhibitory effect on platelet aggregation and fibrinolytic activity in humans.

Unlike many other herbs, garlic is also a biologically active food with presumed medicinal properties, including possible anticancer effects. Clinical studies of garlic in humans address three areas: (1) effect on cardiovascular system–related disease and risk factors such as lipid levels, blood pressure, glucose level, atherosclerosis, and thrombosis; (2) protective associations with cancer; and (3) clinical adverse effects. There are multiple clinical studies with promising but conflicting results. There is high consumer usage of garlic as a health supplement.

Scant data, primarily from case-control studies, suggest that dietary garlic consumption is associated with decreased risk of laryngeal, gastric, colorectal, and endometrial cancer and adenomatous colorectal polyps. Single case-control studies suggest that dietary garlic consumption is not associated with breast or prostate cancer.

Cholesterol levels have been related to use of garlic as well. Thirty-seven randomized trials, all but one in adults, consistently showed that, compared with use of a placebo, use of various garlic preparations led to small, statistically significant reduction in total cholesterol at 1 month (range of average pooled reductions, 1.2 to 17.3 mg/dL). Garlic preparations studied included standardized dehydrated tablets, “aged garlic extract,” oil macerates, distillates, raw garlic, and combination tablets. Statistically significant reduction in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels (range, 0 to 13.5 mg/dL) and in triglyceride levels (range, 7.6 to 34.0 mg/dL) also were found. One multicenter trial involving 100 adults with hyperlipidemia found no difference in lipid outcomes at 3 months between persons who were given an antilipidemic agent and persons who were given a standardized dehydrated garlic preparation.

Garlic has a range of biological activities. Twenty-seven small, randomized, placebo-controlled trials, all but one in adults and of short duration, reported mixed but never large effects of various garlic preparations on blood pressure outcomes. Most studies did not find significant differences between persons randomly assigned to take garlic and those randomly assigned to take a placebo.

Adverse effects of oral ingestion of garlic are “smelly” breath and body odor. Other possible, but not proven, adverse effects include flatulence, esophageal and abdominal pain, small intestinal obstruction, contact dermatitis, rhinitis, asthma, bleeding, and heart attack. How frequently adverse effects occur with oral ingestion of garlic as a food and whether they vary for particular garlic preparations are not established. Adverse effects of inhaled garlic dust include allergic reactions such as asthma, rhinitis, urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis. Adverse effects of topical exposure to raw garlic include contact dermatitis, skin blisters, and ulcerative lesions. Frequency of reactions to inhaled garlic dust or topical exposure to garlic is not established. Whether adverse effects are specific to particular preparations, constituents, or dosages should be elucidated. In particular, adverse effects related to bleeding and interactions with other drugs such as aspirin and anticoagulants warrant further study.

Research Questions on Garlic

Like garlic, ginger can be considered as both a popular ingredient in prepared foods and an effective medicinal plant remedy. Ginger has long been known and used for its antinausea effects and calming properties on the stomach—thus, the traditional popular beverages ginger ale and ginger beer. It is particularly useful for nausea associated with pregnancy and with chemotherapy, for which acupuncture is also a useful alternative therapy.

INDIVIDUALITY

The emphasis of CAM is on the whole person as a unique individual with his or her own inner resources. Therefore the concepts of normalization, standardization, and generalization may be more difficult to apply to research and clinical practice compared with the allopathic method. Some believe that alternative forms of medicine restore the role of the individual patient and practitioner to the practice of medicine; the biomedical emphasis on standardization of training and practice to ensure quality may leave something lost in translation back to restoring the health of the individual (see Chapter 24).

The focus on the whole person as a unique individual provides new challenges to the scientific measurement of the healing encounter. Mobilizing the resources of each individual to stay healthy and get well also provides new opportunities to move health care toward a model of wellness and toward new models for helping solve our current health care crisis, which is largely driven by costs.

If the body heals itself, has its own energy, and is uniquely individual, then the focus is not on the healer but on the healed. Although this concept is humbling to the role of practitioner as heroic healer, it is liberating to realize that in the end, each person heals himself or herself. If the healer is not the sole source of health and healing, there is room for humility and room for both patient and practitioner to participate in the interaction.

For the purposes of this book, a functional definition of CAM is offered, limited here to what may be called complementary medical systems. Complementary medical systems are characterized by a developed body of intellectual work that (1) underlies the conceptualization of health and its precepts; (2) has been sustained over many generations by many practitioners in many communities; (3) represents an orderly, rational, conscious system of knowledge and thought about health and medicine; (4) relates more broadly to a way of life (or lifestyle); and (5) has been widely observed to have definable results as practiced.

Although the term holistic has been applied to the approach to the “body as person” among CAM systems, I apply holism to the medical system itself as a complete system of thought and practice (what I have called “health beliefs and behaviors,” Chapter 2). This system of knowledge is therefore shared by patients and practitioners—the active, conscious engagement of “patients” is relative to the focus on self-healing and individuality that are among the common characteristics of these systems.

In this regard it might be considered that we are trying to document here the “classic” practice of CAM systems. In trying to build a bridge between a well-developed system of allopathic medicine and complementary medical systems, it is necessary to have strong foundations on both sides of this bridge. It is not possible to apply these criteria to the work of individual alternative practitioners who have unilaterally developed their own unique techniques over one or two generations (what might be called “unconventional”), just as it is not possible to build a bridge to nowhere. This definition is meant to apply to systems of thought and not just techniques of practice. Often an underlying philosophy of individual practitioners surrounds new techniques they have developed, or new techniques may be subsumed under existing systems of practice.

Eclecticism is itself a historical form of alternative medicine that drew from among different traditions and was popular in the United States in the nineteenth century. In such a system, treatment is determined by the needs of each individual patient, not limited to what one given system has to offer. At present a chiropractor may practice in an Ayurveda clinic; osteopaths may practice in allopathic clinics; and chiropractors, osteopaths, or allopaths may use acupuncture. Naturopathy, in some ways the most recent of homegrown alternatives from the Euro-American tradition, consciously uses a variety of traditions ranging from acupuncture to herbal medicine. I have termed naturopathy neoeclecticism, with the underlying philosophy that the body heals itself using resources found in nature (see Chapter 21).

In the end a given system develops in answer to human needs. Alternatives vary widely, but their characteristics cluster around the self-healing capabilities of the human organism and the human organism’s ability to use (and reliance on) resources present in nature. What is constant and at the center of such CAM systems is the individual human. Therefore, if the focus is not on the medical system itself but on the person at the center, there is really only one system.

FUNDAMENTALS

Contemporary biomedicine is a scientific paradigm with a particular history, as much influenced by social history as by scientific laws. In the laudable effort to make medicine scientific, we have emphasized that knowledge about the world, including nature and human nature, must be pursued using the following criteria: (1) objectivism—the observer is separate from the observed; (2) reductionism—complex phenomena are explainable in terms of simpler, component phenomena; (3) positivism—all information can be derived from physically measurable data; and (4) determinism—phenomena can be predicted from a knowledge of scientific law and initial conditions. We all know that this is not the only way of “knowing” things, but it became the twentieth-century test to determine whether knowledge is “scientific.”

In fact, science simply requires empiricism—making and testing models of reality by what can be observed, guided by certain values, and based on certain metaphysical assumptions. Science itself is a system of human knowledge. Scientists often detect differences between metaphysical reality and the scientific models constructed through human intellectual activity. These new thoughts about the nature of medicine do not represent a new science so much as they represent a new philosophy.

Therefore the four criteria just listed are not always applicable. In the science of physics, objectivism is ultimately not possible at the fundamental level because of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which states that the act of observing phenomena necessarily influences the behavior of the phenomena being observed. Contemporary biological and ecological science has produced a wealth of observations about interactions among living organisms and their environments in transactional, multidirectional, and synergic ways that are not ultimately subject to reductionist explanations. For positivism and determinism to provide a complete explanation, we must assume that science has all the physical and intellectual tools to ask the right questions. However, the questions we ask are based on the history of science itself as part of the history of human intellectual inquiry.

A final point about alternative systems: In a way that is perhaps particular to the United States, complementary and alternative medicine systems imply the importance of individuality and choice. In an era in which the active engagement of the individual in his or her own health is a paramount goal, the importance of individuality and choice could not be greater.