CHAPTER 10 ENERGY MEDICINE

ENERGY AND ENERGY MEDICINE

Modern definitions for energy are introduced to grade school students. In the United States, high school students are taught formal (mathematical) definitions for energy as part of introductory physics courses. Energy is defined as the ability to do work and has two basic forms, potential and kinetic. Potential energy is stored energy and has the ability to do work. Kinetic energy is, simply put, the movement of things—from air molecules to sound to the splitting of neutrons into atomic nuclei. Underlying these deceptively simple descriptions are several subtleties that have been investigated and understood to such an extent that we can harness the awesome power of atomic energy.

Thus, we can see how putting a venipuncture needle in someone’s arm is an example of kinetic energy: the movement of the needle through the skin, the movement of the fluid into the lumen of the vein, and the movement of the pharmaceutical agent to the receptor of the target cell. Then, in a microburst of activity the receptor binds the agent, often releasing potential energy that was stored in the characteristic configuration of the receptor itself. The change in receptor topology releases stored energy and helps to propel or allow the movement of molecules and atoms across the cellular membrane, in the process consuming potential energy stored in the molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the universal coin of energy in the biology of cellular reactions and actions.

It is at this energetic interface that the pharmaceutical industry and much of allopathic medicine have focused their efforts. This is the space where endogenous molecules as well as pharmaceutical agents ultimately interact with our physical selves. These agents cause and modulate cellular responses through interactions with a class of biomolecules called “receptors.” Sometimes the agent is harvested and acquired from natural sources (materia medica), sometimes it is synthesized in a laboratory, and nearly always it interacts with a naturally occurring receptor type associated with some tissue or organ, or groups of tissues or organs. The point is that all of these steps and the downstream and sidestream consequences involve the use of energy and its transformation from potential to kinetic and back again with some loss to heat and randomness at every step. All health and healing involve these biochemical, energy-driven reactions, and thus all healing is a form of energy medicine.

Because of our understanding of the nature of these biochemical reactions, we believe that all of life is dependent on these reactions and that when these fail, life ceases. Certainly, life is dependent on these chemical energies, and in allopathic medicine we use the kinetic energy of objects (i.e., pharmaceuticals) to affect biological processes and, hopefully, maintain or improve health and healing.

SUBTLE AND VITAL ENERGY

It is also well known that different types and sources, or packets, of energy may interact, which results in a modulation or change in the energies involved. It is at this interface that energy medicine takes place, and we will describe possible models for understanding this interface.

So far we have described a conventional view of energy in healing. However, the “energy” in so-called energy medicine is not of this nature. First and foremost, it is not directly measurable. Second, it does not appear to fall off in power with distance by the inverse square law. Finally, it is not blocked by barriers that block conventional energy. This distinction in “energies” is important, because often these two very different concepts are used interchangeably and confusion results. Yet both types of “energy medicine” are placed in this single category by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). This blindsight may not be a surprise, because when members of Congress were first legislating the funding to create what is now the NCCAM at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), leaders at the NIH told Congress that the NIH “does not believe in bioenergy” (Sen. Arlen Specter R/D-PA, personal communication). It has been suggested to Congress (by the editor of this book) that the U.S. Department of Energy may be a better place to study bioenergy. We will summarize research involving both types of energy, but will make a clear distinction between the two uses of the term. We will also discuss the limits of current standards for evaluating this area and possible models to help improve our understanding of these concepts.

The intriguing and disputed (at least by Western allopathic healers) energy medicines such as qigong, reiki, and therapeutic touch are thought to involve putative forms of energy. That is, not only have there been questions about the efficacy of these energy medicine modalities, but there have not been any unequivocal demonstrations of the involvement of either known or heretofore unknown forms of energy from the healer or between the healer and the patient. These modalities are based on philosophy, historical use, and/ or tradition but without much modern scientific empirical evidence. These energy medicine modalities are thought to involve the interactions between the “energy field” of the patient and the energy field or the intention of the healer. We will return to this idea of intention and interaction with forms of energy when we discuss the quantum enigma. For now, we will consider what is meant by the use of the terms intention and human energy fields to be related and interdependent.

As hinted at earlier, often what is missing is a rational mechanism of action in the practice of energy medicine. The confounding of mechanism with empiricism in the study of healing has been an ongoing challenge in medicine (see Chapter 6). This mechanism provides a distinction between veritable forms of energy medicine such as magnetic therapy and the putative forms such as reiki (NCCAM, 2007). In spite of this gap in our understanding and knowledge, and the stress placed on understanding mechanism by the biomedical complex, it remains difficult to find funding for basic mechanistic studies. For several years, the NCCAM dedicated over 60% of its budget to clinical research and 20% to applied research at centers, with only the remaining funds allocated to basic research (http://nccam.nih.gov). Further, the NCCAM continues to move more toward clinical trials (although the methodology for such trials is frequently inappropriate; see Chapters 5 and 26), to the further exclusion of basic research and applied research. Thus, basic research on energy (both veritable and putative) medicine is scarce.

Although recent literature on forms of bioenergy—qi, ki, prana—and their biomedical application has significantly increased, the form of energy involved in energy medicine remains largely mysterious. There are some recent examples in the English-language literature of attempts to characterize this energy (Ohnishi et al, 2008), but these studies have not been replicated by other groups. To date, the most complete, criteria-based, systematic review of this area is the book by Jonas and Crawford (2003b). An additional comprehensive survey has been compiled by Benor (2004).

In addition, over the past 30 years considerable work has been done on the measurement of external qi as physical energy. The majority of publications in this field are in Chinese and therefore are not easily accessible to the Western scientific community. The few English-language references dealing with bioenergy include a book by Lu (1997). A more complete review by Zha is found in the proceedings of the Samueli Hawaii meeting of 2001 (Zha, 2001). A thorough review of previous work on physical measurements of external qi is outside the scope of this chapter, and the previous references are included as the most accessible material. It appears from these documents that the previous experiments neither had been done in a rigorously controlled way nor had utilized instruments that are currently state of the art. The documented experiments reveal, at best, very low levels of physical energy associated with external qi emission by qigong practitioners and healers (Hintz et al, 2003).

The lack of solid evidence or an accepted mechanistic explanation for the “energy” in energy medicine presents a fairly large hurdle to acceptance by Western medicine. Although there is no universal agreement as to what is meant by the “energy” in energy medicine—or even what kind it might be—terms such as “subtle energy,” “qi energy,” and prana are often used. There does seem to be some consensus on both sides of this discussion that, whatever it is, it is not the energy currently identified and described by traditional Western physics (see Chapter 1).

Finally, for a concept of such “energy” to be of value and to be adopted within the scientific community there must be consilience among and with accepted physics, chemistry, and biology. Therefore, any putative bioenergy involved in energy medicine must be internally consistent and allow for consilience with the other known energies. A cybernetic or systems analytic approach consistent with conventional descriptions of electromagnetic energies describing this system is shown in Figure 10-1 and is a level of abstraction based on the concepts of (1) information sources, (2) a medium for carrying the signal, and (3) receivers. In this view, the underlying physical layer of transfer of information is intentionally hidden to allow discussion of the transfer of bioinformation without an a priori decision about what is the physical mechanism for that transfer (Hintz et al, 2003).

In this model, we can define a bioenergy system as one which is comprised of the following:

The input and output coupling depends on properties of the source and the transfer medium, and likewise for the sink. The term perception rather than reception is used to imply some active process that uses some form of perceptual reasoning in processing the information based on its content.

The means by which information is transmitted and interacts with the system, in the sense that physicists understand it, is not clear. Feedback loops in biosystems are examples of information transfer. In most, if not all, cases the physical means by which the feedback is provided to the system is either understood or is assumed to involve interactions among actual physical objects. In the case of the placebo pill and the branding study reported later, it is not self evident how the information is transmitted but, de facto, it appears to be.

Thus, in these studies, information is able to significantly influence a biological system and its response to pain. Although we have some understanding of the biological consequences of energy medicine (Yan et al, 2008), the means by which this is done, the “energy,” remains unknown. For example, qigong has been demonstrated to have antidepressive effects in patients, but although the psychological mechanisms underlying this effect have been described, the neurobiological mechanism remains unclear (Tsang et al, 2008). The same may be said of hypnosis, for which the clinical effects are now widely accepted (thanks in part to statistical profiling) but the neurobiological mechanism has remained unclear since the time of Mesmer (see Chapter 6). The authors conclude that further research is needed to elucidate the biology and consolidate its scientific base.

There are examples within the field of veritable energy medicine, however, in which there is a good understanding of the energies and energy fields involved. For example, the magnetic fields employed in transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) are well characterized (see Chapter 11). Even so, the biology and biological mechanisms at work and affected by the magnetic fields are only beginning to be understood (Lopez-Ibor et al, 2008). Thus, although TMS has been shown to be an effective alternative for the treatment of refractory neuropathic pain by epidural motor cortex stimulation, the mechanisms at work remain poorly understood (Lazorthes et al, 2007).

STANDARDS AND QUALITY

Although it is facile to recommend that complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) be held to the same standards as conventional medical science, the complexity and intricacies of CAM are reported by the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy (2002). This is particularly true for energy medicine.

Studies are conducted in nearly all the CAM disciplines that lend themselves to the hypothesis-driven paradigm, and a search of the literature attests to that. Essentially, CAM scientific research is following the same standards used for conventional research, that is, the use of statistically significant number of subjects, specimens, or replicates; the introduction of internal and experimental controls; the definition of response specificity; and the requirement for reproducibility. The last is perhaps the most challenging criterion. In several cases, experiments have shown positive results but when repeated, sometimes in the same laboratory, do not work despite following the precautions of maintaining identical experimental conditions.

This challenge is illustrated in the work published by Yount et al (2004). They investigated the effect of 30 minutes of qigong on the healthy growth of cultured human cells. A rigorous experimental design of randomization, blinding, and controls was followed. Although both a pilot study that included 8 independent experiments and a formal study that included 28 independent experiments showed positive effects, the replication study of over 60 independent experiments showed no difference between the sham (nontreated) and treated cells. This study represents an excellent example of holding basic science research on energy medicine to the highest standard of experimental methodology.

This level of rigor is rarely achieved in energy laboratory research, however. The basic and clinical research in the area of distant mental influence on living systems (DMILS) and energy medicine was reviewed. The quality of research was quite mixed. Although a few simple research models met all quality criteria, such as in mental influence on random number generators or electrodermal activity, much basic research into DMILS, qigong, prayer, and other techniques was poor (Jonas et al, 2003b). In setting up these evaluations, the reviewers established basic criteria that should be met for all such laboratory research (Jonas et al, 2003a; Sparber et al, 2003).

In basic scientific research, formulating the testable hypothesis is sometimes not the major issue; it is setting up and testing the practice itself. In the example of Yount et al (2004), in which they followed the most rigorous methodological and experimental designs, the practice under investigation was not a simple treatment with defined doses of a pharmaceutical compound or an antagonist of a specific receptor. Instead it was an unknown amount of energy of unknown characteristics emanating from the hands of a number of qigong practitioners, with variable skills.

Acupuncture is a CAM application that lends itself to use in animal models for in vivo and ex vivo evaluation of its effects. By applying electroacupuncture, researchers are able to control the amount of energy delivered. However, the challenge here is the placement of the needles. Whereas in humans, needles would be placed based on meridian maps, in rats they must be placed so that they will not be disturbed during normal grooming while still being located along a meridian of relevance. In addition, 20-minute electroacupuncture is what is often used because this is what would be done in humans (Li et al, 2008), but should not the time and dose parameters be adjusted to the animal’s body size?

Mind-body–based therapies are often not considered energy medicine, especially when applied to oneself, although they are considered so for the purposes of this book. However, when the goal is to produce a change in an outside entity through meditation, for example, then we claim this is a form of energy medicine and, as such, very challenging to explore in a laboratory setting. Although there are several studies showing the effects of meditation on cell growth (Yu et al, 2003), differentiation (Ventura, 2005), water pH, and temperature change, as well as on the development time of fruit fly larvae (Tiller, 1997), we believe that for these studies the necessary level of methodological rigor has not been met. Independent replication has been especially problematic. On the other hand, some CAM applications, such as homeopathy, phytotherapy, and dietary supplements (Ayurveda or traditional Chinese medicine) are relatively easy to translate to the laboratory setting. This is due to the fact that these practices and their products of use can be thought of as conventional interventions using pharmaceutical compounds, for which dose and time-course experiments can be designed. We will return to homeopathy later in this chapter as a form of energy medicine.

HOW GOOD IS GOOD ENOUGH?

At this point it is appropriate to talk about levels of evidence and how we should catalogue the evidence, and at what point we should consider policy and educational changes to health care training to incorporate new information, knowledge, and understanding.

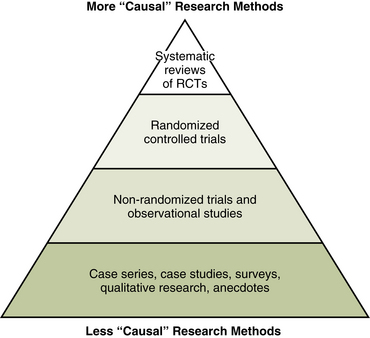

When evaluating scientific evidence one must carefully consider the nature of the evidence itself. Figure 10-2 shows a way to categorize the types of data associated with biomedical research. This evidence pyramid illustrates how to evaluate the “causal” characteristics of the data. Thus, randomized controlled trials are second from the peak or best evidence, which is systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials. At the base are anecdotes, qualitative research, and case studies. Evidence of this type should not be ignored, but it should not be overinterpreted. In cases in which the information is sufficiently compelling, the therapeutic interventions are novel, or the condition has no other remedies available for patients, then further studies are often warranted. The “evidence” may be good enough to indicate the need for further research and the generation of more valid data but may not be good enough to form a basis for medical decisions.

ORTHODOXIES AND PLACEBO

Virtually all the doctor’s healing power flows from the doctor’s self-mastery.

Healing power consists only in and no more than . . . bringing to bear those forces . . . that already exist in the patient.

—ERIC J. CASSELL, MD, THE NATURE OF SUFFERING AND THE GOALS OF MEDICINE, ED 2, 2004

By the same token, we should always examine our orthodoxies and assumptions. For example, it would be reasonable to assume that subjects given a placebo for pain would get little to no relief. In a study reported at the 1979 Society for Neuroscience conference, R.H. Gracely showed evidence that the expectations (intentions?) of the physician significantly affected the outcomes (Gracely and al, 1979) (Figure 10-3). All subjects were given the same placebo, but half were given it by physicians who thought they were giving active medication. The patients of physicians who thought they were giving an active agent experienced a significant reduction in pain, whereas subjects in the other study arm received no relief and in fact their pain got worse.

Figure 10-3 Physician knowledge affects outcome.

(From Gracely RH et al: The effect of naloxone on multidimensional scales of postsurgical pain in nonsedated patients, Soc Neurosci Abstr 5:609, 1979.)

In 1999 the impact of expectation was further explored in a four-arm study carried out by C.E. Margo (1999). One group was given an “unbranded” placebo, another group was given a “branded” placebo, a third group was given unbranded aspirin, and the fourth group was given branded aspirin. As can be seen from Figure 10-4, there appears to be an analgesic effect just from the act of taking a pill, and this effect is significantly improved if the pill is branded. In this study actual aspirin produced greater analgesia than branded placebo, and branded aspirin was better than unbranded aspirin for analgesia. The author interpreted these data to indicate that taking a pill has significant analgesic effect for patients with pain, whether the pill has any conventionally defined “bioactive” agent or not. Further, branding of the pill enhances the effect whether it is a placebo or active. One can interpret this as a demonstration of the power and efficacy of therapeutic expectation (a form of intention) (Kirsch, 1999).

MAGNETIC THERAPY

Before we get into the more exotic forms of energy medicine, and to drive home our point about the need to evaluate the quality and type of information we have on a subject, we discuss the relatively well studied use of magnetic therapy for the treatment of pain (see Chapter 11).

Magnetic therapy is reportedly a safe, noninvasive method of applying magnetic fields to the body for therapeutic purposes. The use of magnets for relief of pain has become extremely popular, with consumer spending on such therapy exceeding $500 million in the United States and Canada and $5 billion worldwide (Weintraub, Mamtani, Micozzi, 2008; Weintraub et al, 2003). There have been many clinical studies of magnetic therapy. For example, Therion’s Advanced Biomagnetics Database claims to contain over 300 clinical studies. However, few of these are randomized controlled trials, and the quality of the research is unknown.

It has been known for a while that magnets can reduce pain in subjects (Vallbona et al, 1997). Table 10-1 shows the data from a 1997 study by Vallbona et al. A highly significant analgesic effect is demonstrated by these data. Overall, the evidence shows that patients with severe pain appear to respond better to magnetic therapy than patients with mild symptoms. There appear to be no adverse effects from application of static or dynamic pulsed magnetic therapy (Harlow et al, 2004; Segal et al, 2001; Weintraub and Cole, 2008; Weintraub et al, 2003). In a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial involving 36 symptomatic patients with refractory carpal tunnel syndrome, application of dynamic magnetic fields produced significantly greater pain relief than use of a placebo device as measured by short- and long-term pain scores, and better objective nerve conduction without changing motor strength or sensitivity to electrical current (Weintraub and Cole, 2008; Weintraub, Mamtani, Micozzi, 2008).

TABLE 10-1 Proportion of Subjects Reporting Improvement of Pain After 45 Minutes of Magnetic Therapy

| Active magnetic device (n = 29) |

Inactive device (n = 21) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Pain improved | n = 22 (76%) | n = 4 (19%) |

| Pain not improved | n = 7 (24%) | n = 17 (81%) |

χ2 (1 df) = 20.6, P <.0001.

From Vallbona C, Hazlewood CF, Jurida G: Response of pain to static magnetic fields in postpolio patients: a double-blind pilot study, Arch Phys Med Rehabil 78:1200, 1997.

The Weintraub study on magnetic therapy (Weintraub et al, 2003) was the first multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to examine the role of static magnetic fields in treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and neuropathic pain. The results confirmed those of two previous pilot studies showing that the antinociceptive (pain relief) effect was significantly enhanced with long-term exposure to magnetic therapy. Since then the evidence has continued to support magnetic therapy as an effective tool for dealing with neuropathic pain (Segal et al, 2001).

Overall, 14 of 22 studies reported a significant analgesic effect of static magnets. Of the 19 better-quality studies, 12 found positive results and 6 found negative results, and in 1 there was a nonsignificant trend toward a positive analgesic effect. The weight of evidence from published well-conducted controlled trials suggests that static magnetic fields are able to induce analgesia (Eccles, 2005).

Taken as a whole, the studies of magnetic therapy are of the type required by the evidence pyramid (see Figure 10-2) to qualify as good to best and demonstrate a causal link between magnetic therapy and analgesia.

Clearly there is an interaction of energy with the body. This interaction probably involves electric potentials and action potentials across neuronal membranes with known and measurable forms of energy that we have called “veritable” forms of energy medicine. Veritable energy medicine includes electromagnetic, sound, and light therapies (NCCAM, 2007).

DISTANT HEALING

Let us now look at a set of studies performed to examine the effects of a healer’s employing distance healing on cells in culture. This healer explained that he uses intention to focus his mind and channel “Divine love through his heart” to perform healing. This claim and similar energy medicine practices are often called “distant healing” because the practitioners do not place their hands on the patient or subject. Practitioners of this form of healing believe that the distance does not matter, although most, in fact, do their work within a foot or so of their patients. This healer usually placed his hands within inches of the person on whom he was working. As an aside, he also performs diagnosis by placing his hands near the person but without touching the person. We will return to the issue of distance later in the description of the studies’ findings. The approach of this healer is typical of the so-called laying on of hands practiced in many cultures and accepted and associated traditionally with healing in Western medicine as well as Judeo-Christine tradition.

The explanation often given for any benefit seen from energy medicine of this kind is that it is a strong placebo effect that results from belief and expectation generated during the encounter (Moerman et al, 2002). The investigators intended to minimize this effect by using cells grown in laboratory culture. The healer came to the laboratories one morning per week throughout much of two sequential winters. The researchers wanted to understand how he “communicated” with cells in the laboratory and influenced them with his “intention” in a positive and healthful way. The study would not involve diagnosis or even a human subject. By working with cultured cells in a laboratory setting, the investigators increased their power over the experimental and control parameters by comparing the effects of the healer to no treatment or sham treatment, comparing treatments at different doses and time periods, and examining the effects of various other environmentally controlled conditions, including the effects of expectation with blinding.

The healer was asked to alter the calcium flux in such a way as to increase the concentration of calcium ions inside the cells. Any change in cellular calcium was measured by putting the cells in a scintillation counter before and after the healer’s “treatments.” A demonstration of significant effect would be powerful evidence that something, some form of energy presumably, flowed from the healer to the cells and changed their biochemistry in a targeted, intentional, and specific way.

The studies used Jurkat cells, an immortalized line of T lymphocytes derived from human immune system T cells. They were established as an immortalized line in the late 1970s and are available for purchase and easy to grow and maintain in the laboratory. They have been used extensively to study mechanisms of action for human immunodeficiency virus and anticancer agents. There is, in fact, a vast literature on Jurkat cells, because they are a favorite choice for cellular immunobiologists interested in understanding cellular mechanisms of the immune system.

The setup was quite simple. Jurkat cells were grown in tissue culture dishes to near confluence, then on the day of the experiment the cells were suspended in a balanced salt solution, “loaded” with calcium-sensitive dye (fura-2) and placed inside a square cuvette. Because of the activity of the dye the amount of light emitted by the cells is proportional to the amount of free calcium ions inside the cell. When the light is measured spectrofluorometrically, this technique provides an accurate and objective measure of the amount of free calcium inside the cells.

As noted earlier, the healer was asked to increase the internal concentration of calcium ions inside the cell. He told the investigators that he would need 15 minutes of relative quiet while he placed his hands near the cuvette of cells and concentrated on his intention (Figure 10-5). The experiments were repeated in six independent trials occurring on different days. Internal cellular calcium concentrations were significantly increased by 30% to 35% (P <.05, Student t test) compared with controls run in parallel. Varying the distance between 3 and 30 inches did not seem to have an effect on the outcome (Kiang et al, 2005).

Three independent attempts were made by the healer to affect calcium concentration in this system from approximately 10 miles away. He tried first with internal visualization, then with a photograph of the cells to focus his attention, and finally with a video camera display of a “live” version of the cells. None of these tests produced any noticeable change in the calcium concentration. Anecdotally, a few uncontrolled tests were run in which the healer’s hands were kept behind his back rather than toward the cuvette of cells. This position seemed to interfere with his ability to affect calcium concentration. This occurred in spite of the fact that the researchers documented a “linger effect” in which cells put on the table where the healer had focused his intention but after he had left showed an increase in calcium concentration similar to that of the cells that had been directly subject to his intention. This linger effect disappeared over time, and within 24 hours cells placed in this way had a calcium concentration no different from that of controls.

Finally, the investigators attempted to block the healer’s “energy” or intention by placing a grounded copper Faraday cage around the cuvette containing cells. Thus the healer, although still within 30 inches of the cells, had to keep his hands outside of the wire enclosure surrounding the cells. There was no significant difference in effect on the internal calcium concentration. It was still raised by the healer’s 15 minute “treatment.” This suggests that, whatever the energy is, it is not blocked by a Faraday cage the way an electric field would be (Box 10-1).

THERAPEUTIC TOUCH, HEALING TOUCH, AND ENERGY THERAPIES

Reiki, healing touch (HT), qigong, and therapeutic touch (TT) are all “energy therapies” that use gentle hand techniques thought to help repattern the patient’s energy field and accelerate healing of the body, mind, and spirit. They are all based on the belief that human beings are fields of energy that are in constant interaction with other fields of energy from others and the environment. The goal of energy therapies is to purposefully use the energetic interaction between the practitioner and the patient to restore harmony to the patient’s energy system. Western allopathic approaches focus on diseases and their underlying mechanisms. Cure is the end-all and be-all. Most energy therapies are based on a holistic philosophy that places the patient within the context of that patient’s life and an understanding of the dynamic interconnectedness with themselves and their environment (Cassidy, 1995; Chapter 5). They are about healing rather than cure (Engebretson et al, 2007).

The most common contemporary touch therapies used in nursing practice are TT, HT, and reiki. The first two were developed by nurses, whereas reiki comes out of pre–World War II Japan and although not targeted for nursing is being used today by many in hospital settings (Engebretson et al, 2007; Krieger, 1993; Mentgen, 2001). Controversy has accompanied the use of these therapies, even after the inclusion of these therapies by the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA). The controversy has not prevented their increasing popularity within the profession to promote health by reducing symptoms and ameliorating treatment side effects. Practitioners use TT and HT to improve health and healing by addressing, in the word’s of the official NANDA diagnosis, a patient’s “Disturbed Energy Field: disruption in the flow of energy surrounding a person’s being that results in a disharmony of the body, mind, and/or spirit” (NANDA, 2008).

Like many other energy therapies, TT is not designed to treat specific diseases but instead to balance the energy field of the patient or, through a boosting of energy, improve the patient’s energy. TT was developed by Dolores Krieger, PhD, RN, in the 1970s. She borrowed from and mixed together ancient shamanic traditions and techniques she learned from well-known healers of her time. Like acupuncture, qigong, and yoga, HT is based on the idea that illness and poor health represent an imbalance of personal bioenergetic forces and fields that exist around and through a person’s body. Rebalancing and boosting of these energies is done through a clear intention to support and harmonize the person with his or her innate energy balance. These practices therefore typically begin with the practitioner performing some form of ritual that clears and focuses the intention to bring harmony and balance to the person who is in need.

In a typical TT session, the practitioner begins with a centering process to calm the mind, access a sense of compassion, and become fully present with the patient. The practitioner then focuses intention on the patient’s highest good and places his or her hands lightly on the patient’s body or slightly away from it, often making sweeping hand motions above the body. Enough research on TT has been published in peer-reviewed journals to perform a meta-analysis of the combined results from separate studies. Two meta-analyses have determined that TT produces a moderately positive effect on psychological and physiological variables hypothesized to be influenced by TT, primarily anxiety and pain (Peters, 1999; Winstead-Fry et al, 1999). A systematic review of the HT research published in 2000 included 19 randomized controlled trials involving 1122 patients (Astin et al, 2000). The reviewers found 11 studies (58%) that reported statistically significant treatment effects. Another systematic review of the literature on wound healing and TT found only four studies that met the author’s criteria for quality. Of these, two showed statistically significant effects, whereas the other two found no effect from TT. The evidence is therefore insufficient to conclude that TT works for wound healing (O’Mathuna et al, 2003).

Applications for which TT and HT seem to work well include reducing anxiety, improving muscle relaxation, aiding in stress reduction, promoting relaxation, enhancing a sense of well-being, promoting wound healing, and reducing pain. In addition, no serious side effects have been associated with these healing modalities (Engebretson et al, 2007). One review of touch therapies looked at studies with outcomes such as pain reduction, improvement of mood, reduction of anxiety, promotion of relaxation, improvement of functional status, improvement of health status, increase in well-being, wound healing, reduction of blood pressure, and increase in immune function. The authors found that the studies were mixed in their quality and the degree of evidence supporting the effectiveness of touch therapies in influencing these outcomes (Warber et al, 2003).

Reiki was originally intended as a self-practice. Today it is often performed by practitioners to help their clients strengthen their wellness, assist them in coping with symptoms such as pain or fatigue, or support their medical care, sometimes in the case of chronic illness or at the end of life. Reiki was developed by Mikao Usui in Japan in the 1920s as a spiritual practice. One of his master students, Chujiro Hayashi, with Usui’s help, extracted the healing practices from the larger body of practices. Hayashi began to teach these practices and opened a clinic to treat patients. Reiki practice itself is extremely passive. Practitioners lay their hands gently on the patient or hold them just above the body without moving their hands except to place them over another area. The reiki practitioner does not attempt to adjust the patient’s energy field or actively project energy into the patient’s body. Also, unlike other forms of energy medicine and more like meditation, reiki does not involve an assessment of the patient’s energy field or an active attempt to reorganize or adjust the patient’s energy field. Instead reiki practitioners believe that healing energy arises from the practitioner’s hand as a response to the patient’s needs. It is in this way customized to the patient’s needs and condition.

In one study, 23 reiki-naive healthy volunteers participated in standardized 30-minute reiki sessions. They often reported experiencing a “liminal state of awareness.” This state is characterized by novel and paradoxical sensations, often symbolic in nature. The experiences run the gamut from disorientation in space and time to altered experience of self and the environment as well as relationships with people, especially the reiki master. In another study, quantitative measures of anxiety and objective measures of systolic blood pressure and salivary immunoglobulin A were altered significantly by the reiki experience; anxiety and systolic blood pressure were lowered, whereas immunoglobulin A level was increased. Skin temperature, electromyographic readings, and salivary cortisol level were all lowered but not significantly. When these results are taken together, it is apparent that in this study reiki induced states of lowered stress and anxiety and should be considered salutogenic in nature. The authors concluded that the liminal state and paradoxical experiences are related to the ritual and holistic nature of this healing practice (Engebretson et al, 2002).

A 2008 systematic Cochrane review of the literature on touch therapy for pain relief included studies of HT, TT, and reiki (So et al, 2008). The authors evaluated the literature to determine the effectiveness of these therapies for relieving both acute and chronic pain. They also looked for any adverse affects from these therapies. Randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials investigating the use of these therapies for treatment of pain that included a sham placebo or “no treatment” control arm met the criteria for inclusion. Twenty-four studies, including 16 involving TT, 5 involving HT, and involving 3 reiki, were found that met these criteria. A small but significant average effect on pain relief (0.83 units on a scale of 0 to 10) was found. The greatest effect was seen in the reiki studies and appeared to involve the more experienced practitioners, but the authors concluded that the data were inconclusive with regard to which was more important, the level of experience or the modality of therapy. In spite of the paucity of studies, the authors concluded that the evidence supports the use of touch therapies for pain relief. Application of these therapies also decreased the use of analgesics in two studies. No statistically significant placebo effect was seen, and no adverse effects from these therapies were reported. The authors pointed out the need for higher-quality studies, especially of HT and reiki (So et al, 2008).

LIGHT, HEALING, AND BIOPHOTONS

Light therapy is, of course, a veritable form of energy generally not thought of as a “subtle energy” of the types we have just discussed (NCCAM, 2007) (see Chapter 11). There is good evidence that applied near-infrared (NIR) light (670 and 810 nm) can significantly improving wound healing and even promote neural regeneration in animal models (Byrnes et al, 2005; Whelan et al, 2008). The mechanisms underlying this “photobiomodulation” are not understood. Nonetheless, the therapeutic use of low-level NIR laser light is a promising area. Physiological effects that have been documented include increased rate of tissue regeneration as well as reduction in inflammation and pain. Production of reactive oxygen species by cells put under stress is lowered with NIR treatment. The application of 810-nm NIR light has been tested in an animal spinal cord injury model and has been shown to significantly increase axonal number and distance of regrowth. This light treatment also returned aspects of function to baseline levels and significantly suppressed immune cell activation and cytokine-chemokine expression. The authors concluded that externally delivered NIR light improves recovery after injury and suggested that light will be a useful treatment for human spinal chord injury (Whelan et al, 2008).

To understand more about the role of light in biology and human health, investigators examined the spontaneous emission of ultraweak photons, often called “biophotons,” in humans (Van Wijk et al, 2008). Although these photons are in the visible range (470 to 570 nm) they are at too low a level to be seen in normal background light. Thus, a very efficient photomultiplier was developed, and the experiments were run in a completely light-tight environment. Reactive oxygen species are theorized to be the principle source of the photons, because these are very reactive molecules and are involved in interactions with high enough energy to result in spontaneous photon emissions. Measurement of human photon emission (biophotons) may therefore be a noninvasive method for assessing oxidative state, general health, chronic disease, and healing.

The study found that biophotons were emitted in a generally symmetrical pattern from the human body. This was not true for individuals with chronic diseases such as diabetes and arthritis, however. Further, reproducible emission patterns were demonstrated in meditating subjects, and another pattern was identified in sleeping individuals. The investigators believe this approach holds promise as a real-time, continuous, and noninvasive method for monitoring health, wellness, healing, and chronic disease, and perhaps even states of consciousness.

An important focus for future research is whether energy medicine modalities exploit these biophotonic emissions. It is not hard to imagine that some, or perhaps all, of us are able to detect these emissions. If this is possible, it is a small step to imagine that healers “learn” to detect these biophotons and their correlations with health or the lack of it. Finally, is it possible that healers interact with their clients’ biophotons and use this system not only to gain information and knowledge but, in fact, to transmit biological information and instructions to their clients through these interactions? Is it possible that healers emit biophotons in patterns to which a patient’s biosystems and biophotons respond and with which they interact? At this point, these are all untested hypotheses. Only by further researching these questions will we learn the answers.

THE QUANTUM ENIGMA

I cannot seriously believe in [quantum physics] because . . . physics should represent a reality in time and space, free from spooky actions at a distance.

Since its inception quantum mechanics has had a problem with consciousness—this in spite of the fact that it is the most rigorously tested theory in all of science. Furthermore, no test ever performed has ever failed to agree completely with the theory (Rosenblum et al, 2008). So, where is the problem?

Although quantum mechanics is applied in much of our daily lives, from computers to magnetic resonance imaging, there is an aspect of it that is counterintuitive and paradoxical. This enigma is best illustrated with light in what is called the “double-slit experiment.” As the reader will recall, light has a dual (and paradoxical) nature. It can be either a wave or a “particle” (photon) (see Chapter 1), and Nobel Prizes have been awarded both for demonstrating that light is a wave and for demonstrating that light is a particle. Which of these it is at any moment is dependent on our conscious observation. How can this be? At this moment in time no one knows, but the evidence has never been refuted, and in fact, the more sophisticated we become in our experiments and tests the more entrenched and mysterious this phenomenon becomes (Walborn et al, 2003).

The double-slit interference experiment is performed in the following way. (Because this is not a text or chapter on quantum mechanics, we will gloss over some of the details.) Light is shined into the back of two open boxes with slits on the front sides. On the wall opposite the slits, on the other side from the light source, is a projection screen. No light can reach this screen except the light that comes through the slits. If the slits are narrow enough and spaced properly, the waves of light come out the slits and, because they are made of waves with high points (peaks) and low points (valleys), the waves can interact and interfere with each other in a fashion analogous to waves on water. The light spreads out from the two slits and the waves interact where they strike the screen. Where two peaks reach the screen at the same point there is a light band. Where two valleys reach the screen at the same point there is a shadow, because no light has reached this point. What one sees, as demonstrated all the time in physics courses around the world, is a series of light and dark stripes, or “interference pattern.” This is considered definitive evidence for the wave nature of light.

Now here is the next part. The experiment can be run so that only a single “packet” of light exists in both boxes. (This is the part we are glossing over, but this experiment can be and has been done many times.) When this procedure is followed, the interference pattern is still generated, which demonstrates that light is a wave and that the wave of energy was distributed in both boxes. However, if there are photon detectors in both boxes, and we observe them while the experiment is running, only one of the detectors will react, and a photon (a quantum of light energy) will be found in only one box. Furthermore, the interference pattern will not appear because there is no longer a wave of light. The wave function is said to collapse and form the photon. If you find this confusing, you are in good company. No one has been able to adequately explain this undisputed phenomenon, called complementarity. It is important to note that no physicist disputes this phenomenon, but there is considerable controversy as to how to interpret it. The majority simply ignore it and its implications. (To the extent that the mechanisms of much of complementary medicine become understood to be based on this quantum enigma, it may some day be labeled complementarity medicine.)

If this experiment is repeated many times it always comes out one of two ways. If there is no photon detector, then we see the wave nature of light. If there are photon counters in both boxes that we observe, then we only see photons and no wave. Furthermore, the probability of finding the photon in one box or the other is exactly 50:50. It was this phenomenon that drove Einstein to try and wish it away by saying that “God does not play dice.” The reader will have noted that we used italics when describing the act of observation. This is where consciousness comes in. As strange as this sounds, the collapsing of the wave function is dependent not only on the presence of the instruments but on our conscious awareness of their output. This phenomenon is demonstrated elegantly in the recent work of Walborn et al on a phenomenon called quantum erasure (Walborn et al, 2002, 2003).

These same papers address another aspect of quantum physics called entanglement. It appears that the universe makes most, if not all, things in pairs. Thus, it is possible to entangle two photons such that they have paired aspects of their quantum natures. (This is another case in which we are glossing over the technical details, but entanglement at the photon level has been demonstrated repeatedly.) Two photons thus entangled have a very strange property: without any detectable form of energy transfer or communication and in a distance-independent manner, whatever is done to one photon immediately, without time delay and no matter the distance separating them, affects the other entangled photon. This is not a causal effect. Observation and the observer do not cause the effect. Rather, the effect is said to be a nonlocal connectivity or nonlocal correlation (Hyland, 2003).

Where does that leave us? Light has a dual nature, and which of its two natures it demonstrates depends on how we look at it. When photons, and apparently other very small quanta, are entangled they remain entangled regardless of the distance between them. Furthermore, whatever happens to one is immediately reflected in the other without any time delay and with no detectable or explainable form of energy or information transfer. We conclude, as do some physicists (Rosenblum et al, 2008), that these phenomena demonstrate interaction among consciousness and energy and matter that appears to go beyond currently understood principles of physics, and that there are ways to transfer information that are independent of distance and through means that physics has not yet determined.

We feel that the incorporation of quantum physics into the discussion on energy medicine provides a possible explanation for some of the empirical observations, anomalies, and hallmarks of this therapy. In addition to helping to explain the role of consciousness in healing, and in energy medicine in particular, quantum mechanics and physics may explain some of the anomalous observations that have been made in aspects of energy medicine such as distant healing.

Most forms of energy obey an inverse square law. That is, the effect or force drops as an inverse square of the distance. Quantum effects do not show this drop-off with distance. Furthermore, all other energies exert their influence either at or below the speed of light. Quantum effects, however, like many phenomena in energy medicine, seem to happen immediately without an appreciable time delay. Thus, two of the anomalous aspects of energy medicine, independence of time and independence of distance, are also observed in quantum effects (Julsgaard et al, 2001). In this way we may explain the exchange of healing information, or “subtle energy,” between healer and patient from a distance (Bennett et al, 2000).

We are not alone in making this connection. C.W. Smith (1998) has postulated that the body functions as a macroscopic quantum system. This idea may also be applicable to related fields of energy medicine. The data reported by Smith in his 2003 paper suggest that the acupuncture meridian system is made up of quantum domains and networks. Even the proposition that consciousness and intention are connected through quantum mechanical means to our body’s healing potentials has been proposed by others (Jahn et al, 1986).

There are serious problems with this hypothesis, however. Specifically, quantum effects have only been demonstrated at an extremely small scale and are thought by most physicists not to be applicable in domains larger than Planck’s constant (i.e., photons and electrons) and that only traditional Newtonian mechanics applies to domains we experience in everyday life. Smith’s proposal is that there is a hierarchical series of networks and domains in which quantum effects are transmitted to molecules through their quantum particles, and that molecules transfer this information to cells, and so on, until the intact organism is involved and influenced by quantum effects.

HOMEOPATHY AS ENERGY MEDICINE

Homeopathy is defined as yet another form of energy medicine by the NIH (NCCAM, 2007). This may make sense, because standard pharmacology is surely not at work in what are called “high-potency” remedies. These are remedies in which the original active substance is diluted to such an extent that there is no possibility than any of the original constituents are present. Dilutions of 30,000-fold, 100,000-fold, or even a millionfold are quite common in this type of homeopathy. Quantum theory is currently in vogue, and perhaps partly because of its mysterious nature, it is sometimes invoked to explain all aspects of energy medicine, including homeopathy. This is usually not done in a formal mathematical way and is often done by novices to the world of quantum mechanics.

Harald Walach and his colleagues have addressed this gap using a formal mathematical approach, however, and published a paper in Foundations of Physics in 2002 in which they describe how quantum mechanics and quantum theory could be applied to macro environments and to nonphysical properties such as intention and thoughts. Their theory, called “weak quantum theory and generalized entanglement,” demonstrates that, mathematically at least, transfer of information between consciousnesses in a nonphysical way is possible (Atmanspacher et al, 2002). Walach has also produced experimental data to support this hypothesis that need independent replication.

Walach has also gone on to present a case for the application of weak quantum theory and generalized entanglement to homeopathy (Walach, 2003). He contends that the remedies are entangled with both the system and the condition (symptoms) and that even when the original substance has been diluted out of the solution the entanglement remains. Further, he proposes that this explains both the efficacy of homeopathy when it works and the difficulty conventional researchers have in demonstrating this efficacy in clinical trials. Milgrom has also developed formal models for mapping how quantum mechanics could be used to explain the effects of homeopathy and has made suggestions for testing these models in clinical settings (Milgrom, 2006, 2008a, 2008b).

Because entanglement is not fully understood, may not operate inside the normal boundaries of time and space, and is certainly complex and counterintuitive, conventional, linear, cause-and-effect experiments may not properly test the system as it actually exists: entangled. Certainly physicists have demonstrated how counterintuitive and mysterious this property can be, and how difficult it is to show, even when one knows what one is looking for and specifically sets up sophisticated experiments to demonstrate the existence of entanglement. Standard biomedical research methods and study designs, including randomized controlled trials, would not demonstrate entanglement. Walach believes that weak quantum effects and entanglement underlie much of CAM practices and especially energy medicine (Walach, 2005). If this supposition is true, it would explain the difficulty in demonstrating the efficacy of energy medicine using conventional experimental approaches and would simultaneously provide an explanation for the effects that are clinically observed empirically but without apparent causal connections. For example, two salient characteristics of energy medicine are the apparent lack of dissipation of the effect of “subtle energy” with distance and our inability to block the effects with conventional energy barriers (Astin et al, 2000). This same pair of phenomena is observed in entangled quantum effects. Thinking in this way and designing tests to support or refute the weak quantum theory and entanglement hypothesis represent important directions for future research.

SUMMARY

We are not so bold as to suggest that we know the mechanism for energy medicine. On the contrary, we contend that there is legitimate debate as to whether there even is such a thing as “subtle energy.” Our goal in this chapter has been to present some of the discussion that is occurring in the field and the literature around energy medicine. There are at least three theories as to the underlying mechanisms giving rise to the effects of energy medicine: (1) a conventional energy explanation, (2) an explanation based on placebo effects, and (3) a quantum entanglement explanation. Just what the mechanism of the well-established placebo effect may be is not addressed in this distinction. We have spent time in this chapter on the quantum mechanics approach, not because we feel that it is the most correct one, but because it is the most novel and perhaps least understood of the theories, and it also best fits all the best data collected so far regarding all forms of energy medicine.

A mechanism that also might explain the effects of energy medicine is the placebo effect. That is, whatever is going on is the result of patients’ convincing themselves that they are healing or being healed—they feel less pain, they have fewer complaints, and so on—but “nothing really happened” between healer and patient. However, this explanation is not really more satisfactory and also does not fit some of the best data. The placebo effect itself is not understood nor well defined and thus still begs the question of mechanism. Second, if patients actually experience healing and/or feeling better, then something “really” is happening consciously, and we are back to our first point of still not knowing the underlying mechanism while in fact having authentic healing. Thus, we find invoking the placebo effect to be equivalent to confessing that something really is happening with the patient but that we don’t know how, or whether it is coming from within or from without. In addition, the known mechanisms of placebo such as belief, expectancy, and conditioning do not account for some of the best-replicated data on the direct effects of intention in living and nonliving systems and blinded distant effects (Jonas et al, 2003b).

The idea of a “vital force” has been a core aspect of traditional healing practices for millennia and has often been used to explain therapeutic practices in the West such as mesmerism, magnetic healing, and faith healing (see Chapter 6). It has also been part of discussions in Western science at least since 1907 when Henri Bergson proposed it as an explanation for why organic molecules could not be synthesized at the time (Bergson, 1911). This thinking held that electricity—the physics and engineering wonder of the time—was somehow connected with this vital force. Chinese and Indian healers had an equivalent idea many thousands of years older, called “qi” or “prana.” Clearly this idea has been around a long time.

The modern expression of this idea is often called the “biofield hypothesis” (Rubik, 2002). For our discussion here the important aspect of the biofield hypothesis is its dependence on classical electromagnetic fields and forces. (See Rubik’s paper for a more thorough description of this concept and discussion.) As Rubik points out, “The biofield is a useful construct consistent with bioelectromagnetics and the physics of nonlinear, dynamical, nonequilibrium living systems.” Although some aspects of energy medicine may be explained by the biofield and it is completely consistent with and even sufficient to explain magnetic therapy, there are at least two aspects of some forms of energy medicine that it does not adequately explain. One is the apparent distance independence. The other is the apparent instantaneous state change (like quantum entanglement) that is part of some forms of energy medicine. This is the second anomaly of subtle energy medicine: it often happens faster than classical mechanisms could explain.

It is possible that these anomalies, as well as the very fundamental aspects of energy medicine, have their explanation and source in quantum physics. We acknowledge that others disagree with this idea (May, 2003). Still others feel that, although this is not the whole explanation, some aspects of quantum physics may be relevant and may play a role in energy medicine (Dossey, 2003). If it is true that energy medicine is often working through nonclassical and quantum forms of energy, it is now possible to visualize a future in which energy medicine uses a combination of classical and quantum energy fields and forces to target and regulate endogenous processes and fields within the body to affect healing and salutogenesis. If energy medicine and distant healing are fundamentally forms of information transfer, then quantum mechanics may provide the explanation and means for this process. In addition to explaining the transfer of healing energy between people, it may underlie the natural self-healing process itself. Rein (2004) has proposed that this information flow within the body is necessary for health and that when it is impeded ill health and disease result. In this thinking, energy medicine is also the flow of information through quantum effects between healer and patient. In an analogous fashion, salutogenesis and health is the free flow and transfer of information within the body and the interchange of information with the environment to augment this flow. Thus, we believe that the fields of information and quantum models will be important areas of focus for future research and practice. Indeed, if testable theoretical models can be developed that explain data from both veritable and putative forms of energy medicine, a new paradigm of understanding in science and health care may emerge that is as important and revolutionary as our biochemical models were in the twentieth century.

Chapter References can be found on the Evolve website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Micozzi/complementary/

Chapter References can be found on the Evolve website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Micozzi/complementary/