CHAPTER 21 NATUROPATHIC MEDICINE

The doctor of the future will give no medicine, but will interest his patient in the care of the human frame, in diet and in the cause and prevention of disease.

This section describes the background, context, and clinical approaches of select alternative therapeutic systems as developed throughout European and American history. These chapters describe individual approaches as suggested from contemporary Western research, both within and beyond the biomedical paradigm. Where these systems and approaches can be understood in light of the contemporary biomedical paradigm, this view is examined; where they cannot be understood in these terms, this paradox is addressed. When and how these medical systems are embedded in the natural curative environment is clarified, as well as when and how they are embedded in technology. In each case, these medical practices are presented as products of history that make sense in terms of that history.

For example, homeopathy is a highly systematized method of healing that utilizes the principle of “use likes to treat likes” practiced by licensed physicians and other health care professionals throughout the world. In the United States, homeopathic medicines are protected by federal law, and most are available over the counter. The greatest challenge that homeopathy may pose to conventional medicine and science is the common use of extremely diluted medicinal substances.

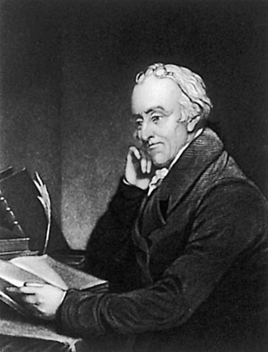

Thomas Edison’s insightful prediction is proving true today, as natural medicine finds itself in the midst of an unprecedented explosion into mainstream health care. Consumers are spending more annually out of pocket for alternative medicine than for conventional care. In particular, naturopathic medicine as the model for integrative primary care natural medicine is undergoing a powerful resurgence. With its unique integration of vitalistic, scientific, academic, and clinical training in medicine, the naturopathic medical model is a potent contributing factor to this health care revolution.

HISTORY OF “REGULAR” MEDICINE AND NATUROPATHIC MEDICINE*

“Regular” Medicine

Conventional or “regular” medicine and natural medicine have shaped and helped to define each other throughout history, often in reaction, and perhaps nothing has had as much influence on naturopathic medicine as the rise of regular medicine. Much as naturopathic doctors today may trace some of their roots to Hippocrates, regular physicians also generally consider his view of health and disease to have contributed to the basis of today’s medicine, primarily because of his rejection of supernatural or divine forces as the cause of illness, which resulted in the transition to a more physiological and rational approach to wellness. However, in contrast to naturopathic medicine, for which it is a core belief, regular medicine has come to reject Hippocrates’ concept of the healing power of nature, a principle that may have done more to define and shape naturopathic medicine than anything else.

Of course regular medicine has made extraordinary leaps since the time of Hippocrates, particularly during the last century, and many aspects of today’s education, scientific understanding, and therapeutic modalities would be unrecognizable to an MD only 100 years ago. We have also seen an unprecedented explosion in the size and role of the health care system in the United States, with over 800,000 MDs practicing as of the year 2000 (American Medical Association, n.d.), and $2.1 trillion spent on health care in 2006 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). By comparison, in the year 1800 there were only 200 graduates of the elite medical schools in the United States, along with 300 immigrants with European diplomas (Kaptchuk et al, 2001). The consistent thread that ties the regular doctors of the past to those practicing today may be a philosophy of allegiance to scientific principles and adoption of a basic biomedical orientation to illness, but coupled with disregard for the body’s innate healing capacity.

In the European countries from which American medical education was derived, medicine first became institutionalized in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, following a low ebb during the Dark Ages of ad 500 to 1050. Sarleno, Italy, was one of the earliest centers of medical training, followed by universities in Paris and England, where some of the first hospitals were built (Cruse, 1999). Although a graduate from Oxford in the 1500s had received up to 14 years of university education, very poor training was offered in the practice of medicine and patient care (Magee, 2004). When the Enlightenment arrived at the far reaches of Europe in Scotland it was a mature intellectual movement emphasizing observation (empiricism) and reason (rationality). The Scottish Enlightenment of the eighteenth century produced advancements in thinking about economics (Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776) and law (David Hume) as well as the roots of the Industrial Revolution with the application of the steam engine (James Watt), based on principles used for the steam distillation of scotch whiskey. The “rational medicine” movement was embodied in the school of medicine at the University of Edinburgh from whence Drs. William Hutchison and John Morgan came to establish the first school of medicine in the United States in 1767 at the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania), following the establishment of the first hospital in the nation by Benjamin Franklin and Dr. Thomas Bond during the prior decade in 1752 (Figure 21-1).

Figure 21-1 Pennsylvania Hospital, the nation’s first hospital, founded in 1752.

(Courtesy the Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia.)

In general, however, in the 1700s little had improved—doctors had limited diagnostic ability, and aside from feeling the pulse, inspecting the tongue, and examining the urine and stool, physicians did not touch their patients and often did not even see them (Magee, 2004). There were no consistent theories to explain the cause of illness, nor could the modalities used to treat them be agreed upon. As a result the medical landscape in the 1800s remained incredibly diverse.

This situation was not inconsistent with the political climate at the time, however. Like today, the cultural values of the early nineteenth century greatly influenced the practice of medicine. In the era of “Jacksonian democracy,” beginning in the late 1820s, American society had begun to reject any form of “elitism,” and the “elites” often included physicians, in large part because regular doctors were mostly available only to the wealthy in society (see Box 1-2). Much of the public harbored a fervent antiintellectualism coupled with belief in the tenet of economic freedom. As a consequence, laws controlling medical practice were viewed by the public as a form of class legislation; a general belief that citizens should have the right to choose their own medical care was combined with a distrust of the motives of “regular physicians” (Ober, 1997). Medical licensing became effectively irrelevant. For most of America’s Colonial period, anyone could practice medicine, without a license, regardless of qualification or training. By 1850, all but two states had removed medical licensing statutes from the books (Whorton, 2002). Numerous conflicting claims of efficacy were made by a variety of practitioners, and an intense and heated competition often left patients confused by and dissatisfied with their experience with all types of physicians. The result has been described as both “medical anarchy” (Ober, 1997) and “a war zone” (Kaptchuk, 2001). Because regular medicine was often ineffective and frequently toxic, many patients and physicians defected to other “alternatives.”

Partially in response, and after prior attempts, in 1847 a group of physicians founded an organization to serve as the unifying body for orthodox medical practitioners, the American Medical Association (AMA). Physicians who belonged to the AMA considered themselves regular practitioners and adhered to therapeutics termed heroic medicine (Rutkow, 2004). It was their treatments that may have most distinguished these regular doctors to their patients, because these often consisted of bleeding and blistering in addition to administering harsh concoctions to induce vomiting and purging, treatments that at the time were considered state of the art. The motivation behind such harsh treatments was a commitment to medical theory and a move away from empirically based medicine. Also, because regular doctors did not share belief in the concept of the healing power of nature (the vis medicatrix naturae), they felt that a physician’s duty was to provide active, “heroic” intervention. Because the majority of patients recovered notwithstanding their treatments, this had the ironic effect of encouraging both regular doctors’ belief in heroic treatments and irregulars’ belief in the inborn capacity for self-healing, despite the further injuries caused by many regular treatments. Much like physicians today are pressured to provide an active treatment that may sometimes be unnecessary (such as an antibiotic for a viral infection), regular doctors of the 1800s also felt pressure to give the heroic treatments for which they were known. As James Whorton (2002) writes, “it was only natural for MDs to close ranks and cling more tightly to that tradition as a badge of professional identity, making depletive therapy the core of their self-image as medical orthodoxy.”

Although the AMA initially held no legal authority, it began a major push during the second half of the nineteenth century to create legislation and standards of medical education and competency. This process culminated in 1910 with the publication of Medical Education in the United States and Canada, compiled by Abraham Flexner (Figure 21-2), also known as the Flexner Report. It has been described as “a bombshell that rattled medical and political forces throughout the country” (Petrina, 2008). It criticized the medical education of its era as a loose and poorly structured apprenticeship system that generally lacked any defined standards or goals beyond commercialism (Ober, 1997). In some of his specific accounts, Flexner described medical institutions as “utterly wretched . . . without a redeeming feature” and as “a hopeless affair” (Whorton, 2002). Many of the regular medical institutions were rated poorly, and most of the irregular schools fared the worst. After this report, nearly half of the medical schools in the country closed, and by 1930 the remaining schools had 4-year programs of rigorous “scientific medicine.”

Following the Flexner Report a tremendous restructuring of medical education and practice occurred. The remaining medical schools experienced enormous growth: in 1910 a leading school might have had a budget of $100,000; by 1965 it was $20 million and by 1990 it could have been $200 million or more (Ludmerer, 1999). Faculty were now called upon to engage in original research, and students not only studied a curriculum with a heavy emphasis on science, but also engaged in active learning by participating in real clinical work with responsibility for patients. Hospitals became the locus for clinical instruction. As scientific discovery began to accelerate, these higher educational standards helped to bridge the gap between what was known and what was put into practice, and more stringent licensing provided a greater degree of confidence in the competence of the nation’s doctors. During this same time period, the suppression and decline of alternative schools of health care occurred, as both public and political pressure increased.

The post-World War II era has been one of undeniable and astonishing achievements by scientific medicine, which has coincided with great strides in public health, sanitation, and living conditions. As understanding of basic clinical science has grown, the biomedical model has continued to evolve, and so has the capacity to make accurate diagnoses and interventions. Today’s physician faces new challenges, however, and some of the deficiencies of regular doctors in the past have reared their heads once again. In an era of managed care and health maintenance organizations, it has become increasingly difficult for physicians to spend quality time with patients or to focus on preventative medicine, and the treatment of chronic disease has suffered. Also, physicians must be vigilant against the constant and insidious efforts of the pharmaceutical industry to corrupt medical science, education, and practice for commercial gain. In addition, the increase in specialization and the decline of primary care is a growing problem that shows no sign of slowing. Today’s regular doctors are also not easily defined—they have been referred to as “mainstream,” “orthodox,” “conventional,” “allopathic,” “scientific,” and “authoritarian,” all of which have their own positive and negative connotations, and none is universally accepted or accurate as individual MDs are more and more becoming receptive to developing new “integrative” models of health care (Berkenwald, 1998; Kaptchuk, 2001). It is also increasingly being recognized that although regular doctors have presented themselves as the “scientific” branch of medicine throughout recent history, the mantle of science cannot be claimed or exclusively worn by any one field of medicine, and integration of various medical specialties and philosophies benefits all.

A pluralistic health care setting is reemerging. Optimally, it will value the organization, structure, and science-based approach of regular medicine, along with qualities regular medicine has typically been lacking, including a patient-centered and individualized care that reaffirms the importance of the relationship between practitioner and patient, recognition and support of innate healing systems, and a broadening of the scientific approach to allow for the evaluation and incorporation of traditional and natural medicines into current health care delivery in a way that makes use of all appropriate therapeutic approaches, health care professionals, and disciplines. “We find ourselves,” John Weeks, the editor of The Integrator, wrote recently, “in an era beyond the polarization of alternative medicine and conventional medicine,” with “an opportunity to become a seamless part of an integrated system that might rightfully be called, simply, health care” (The Integrator Blog, n.d.).

Although naturopathic medicine traces its philosophical roots to many traditional world medicines, its body of knowledge derives from a rich heritage of writings and practices of Western and non-Western nature doctors since Hippocrates (circa 400 bc). Modern naturopathic medicine grew out of healing systems of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The term naturopathy was coined in 1895 by Dr. John Scheel of New York City to describe his method of health care. However, earlier forerunners of these concepts already existed in the history of natural healing, both in America and in the Austro-Germanic European core. Naturopathy became a formal profession after its creation by Benedict Lust in 1896. The profession has now celebrated its 115th birthday.

Over the centuries, natural medicine and conventional medicine have alternately diverged and converged, shaping each other, often in reaction. During the past hundred years the naturopathic profession progressed through several fairly distinct phases, as follows:

The per capita supply of alternative medicine clinicians (chiropractors, naturopaths and practitioners of Oriental medicine) will grow by 88% between 1994 and 2010, while allopathic physician supply will grow by 16%. . . . The total number of naturopathy graduates will double over the next five years. The total number of naturopathic physicians will triple” (Cooper et al, 1996).

Founding of Naturopathy

Naturopathy, as a generally used term, began with the teachings and concepts of Benedict Lust. In 1892, at age 23, Lust came from Germany as a disciple of Father Sebastian Kneipp (the greatest practitioner of hydrotherapy) to bring Kneipp’s hydrotherapy practices to America. Exposure in the United States to a wide range of practitioners and practices of natural healing arts broadened Lust’s perspective, and after a decade of study, in 1902 he purchased the term naturopathy from Scheel of New York City (who coined the term in 1895) to describe the eclectic compilation of doctrines of natural healing that he envisioned was to be the future of natural medicine. Naturopathy, or “nature cure,” was defined by Lust as both a way of life and a concept of healing that used various natural means (selected from various systems and disciplines) of treating human infirmities and disease states. The earliest therapies associated with the term involved a combination of American hygienics and Austro-Germanic nature cure and hydrotherapy.

In January 1902, Lust, who had been publishing the Kneipp Water Cure Monthly and its German-language counterpart in New York since 1896, changed the name of the journal to The Naturopathic and Herald of Health and began promoting a new way of thinking of health care with the following editorial:

We believe in strong, pure, beautiful bodies . . . of radiating health. We want every man, woman and child in this great land to know and embody and feel the truths of right living that mean conscious mastery. We plead for the renouncing of poisons from the coffee, white flour, glucose, lard, and like venom of the American table to patent medicines, tobacco, liquor and the other inevitable recourse of perverted appetite. We long for the time when an eight-hour day may enable every worker to stop existing long enough to live; when the spirit of universal brotherhood shall animate business and society and the church; when every American may have a little cottage of his own, and a bit of ground where he may combine Aerotherapy, Heliotherapy, Geotherapy, Aristophagy and nature’s other forces with home and peace and happiness and things forbidden to flat-dwellers; when people may stop doing and thinking and being for others and be for themselves; when true love and divine marriage and pre-natal culture and controlled parenthood may fill this world with germ-gods instead of humanized animals.

In a word, Naturopathy stands for the reconciling, harmonizing and unifying of nature, humanity and God.

Fundamentally therapeutic because men need healing; elementary educational because men need teaching; ultimately inspirational because men need empowering.

Benedict Lust

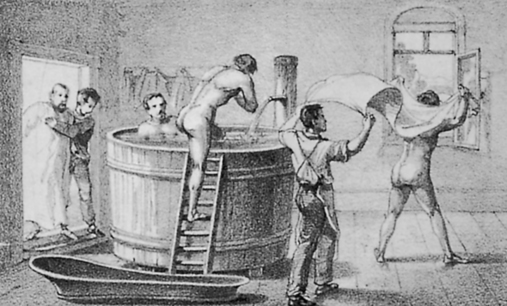

According to his published personal history, Lust had a debilitating condition in his late teens while growing up in Michelbach, Baden, Germany, and had been sent by his father to undergo the Kneipp cure at Woerishofen. He stayed there from mid-1890 to early 1892. Not only was he “cured” of his condition, but he became a protégé of Father Kneipp. He emigrated to America to proselytize the principles of the Kneipp water cure (Figure 21-3).

Figure 21-3 Curative baths, one form of hydrotherapy, were a popular form of natural healing in the late nineteenth century.

(Courtesy Wellcome Institute Library, London.)

By making contact in New York with other German Americans who were also becoming aware of the Kneipp principles, Lust participated in the founding of the first “Kneipp Society,” which was organized in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1896. Subsequently, through Lust’s organization and contacts, Kneipp societies were also founded in Brooklyn, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Denver, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Columbus, Buffalo, Rochester, New Haven, San Francisco, the state of New Mexico, and Mineola on Long Island. The members of these organizations were provided with copies of the Kneipp Blatter and a companion English publication Lust began to put out called The Kneipp Water-Cure Monthly. In 1895 Lust opened the Kneipp Water-Cure Institute on 59th Street in New York City.

Father Kneipp died in Germany, at Woerishofen, on June 17, 1897. With his passing, Lust was no longer bound strictly to the principles of the Kneipp water cure. He had begun to associate earlier with other German American physicians, principally Dr. Hugo R. Wendel (a German-trained “Naturarzt”) who began, in 1897, to practice in New York and New Jersey as a licensed osteopathic physician. Lust entered the Universal Osteopathic College of New York in 1896 and became licensed as an osteopathic physician in 1898.

Once he was licensed to practice as a health care physician in his own right, Lust began the transition toward the concept of “naturopathy.” Between 1898 and 1902, when he adopted the term naturopath, Lust acquired a chiropractic education; changed the name of his Kneipp Store (which he had opened in 1895) to “Health Food Store” (the first facility to use that name and concept in the United States), specializing in providing organically grown foods and the materials necessary for drugless cures; and founded the New York School of Massage (in 1896) and the American School of Chiropractic.

In 1902, when he purchased and began using the term naturopathy and calling himself a “naturopath,” Lust, in addition to operating his New York School of Massage and American School of Chiropractic, issuing his various publications, and running his Health Food Store, began to operate the American School of Naturopathy. All these activities were carried out at the same 59th Street address. By 1907, Lust’s enterprises had grown sufficiently large that he moved them to a 55-room building. It housed the Naturopathic Institute, Clinic, and Hospital; the American School of Naturopathy and American School of Chiropractic; the establishment now called the Original Health Food Store; Lust’s publishing enterprises; and the New York School of Massage. The operation remained in this four-story building, roughly twice the size of the original facility, from 1907 to 1915.

From 1912 through 1914, Lust took a sabbatical from his operations to further his own education. By this time he had founded his large estatelike sanitarium at Butler, New Jersey, known as Yungborn after the German sanitarium operation of Adoph Just. In 1912 he began attending the Homeopathic Medical College in New York, which granted him a degree in homeopathic medicine in 1913 and a degree in eclectic medicine in 1914. In early 1914, Lust traveled to Florida and obtained an MD’s license on the basis of his graduation from the Homeopathic Medical College.

From 1902, when he began to use the term naturopathy, until 1918, Lust replaced the Kneipp societies with the Naturopathic Society of America. Then in December 1919, the Naturopathic Society of America was formally dissolved because of insolvency, and Lust founded the American Naturopathic Association. Thereafter, the association was incorporated in some additional 18 states. Lust claimed at one time to have 40,000 practitioners practicing naturopathy. In 1918, as part of his effort to dissolve the Naturopathic Society of America (an operation into which he invested a great deal of his funds and resources in an attempt to organize a naturopathic profession) and replace it with the American Naturopathic Association, Lust published the first Yearbook of Drugless Therapy. Annual supplements were published in either The Naturopath and the Herald of Health or its companion publication, Nature’s Path (which began publication in 1925), with which The Naturopath at one time merged. The Naturopath and Herald of Health, sometimes printed with the two phrases reversed, was published from 1902 through 1927, and from 1934 until after Lust’s death in 1945.

Benedict Lust’s principles of health are found in the introduction to the first volume of the Universal Naturopathic Directory and Buyer’s Guide, a portion of which is reproduced in Box 21-1. Although the terminology is almost a century old, the concepts Lust proposed have provided a powerful foundation that has endured despite almost a century of active political suppression by the dominant school of medicine.

BOX 21-1 Principles, Aim, and Program of the Nature Cure System

From Lust B: Principles of health, vol 1, Universal naturopathic directory and buyer’s guide, Butler, NJ, 1918, Lust Publications.

Since the earliest ages, medical science has been of all sciences the most unscientific. Its professors, with few exceptions, have sought to cure disease by the magic of pills and potions and poisons that attacked the ailment with the idea of suppressing the symptoms instead of attacking the real cause of the ailment.

Medical science has always believed in the superstition that the use of chemical substances that are harmful and destructive to human life will prove an efficient substitute for the violation of laws, and in this way encourages the belief that a man may go the limit in self-indulgences that weaken and destroy his physical system, and then hope to be absolved from his physical ailments by swallowing a few pills, or submitting to an injection of a serum or vaccine, that are supposed to act as vicarious redeemers of the physical organism and counteract life-long practices that are poisonous and wholly destructive to the patient’s well-being.

The policy of expediency is at the basis of medical drug healing. It is along the lines of self-indulgence, indifference, ignorance and lack of self-control that drug medicine lives, moves and has its being.

The natural system for curing disease is based on a return to nature in regulating the diet, breathing, exercising, bathing and the employment of various forces to eliminate the poisonous products in the system, and so raise the vitality of the patient to a proper standard of health.

Official medicine has, in all ages, simply attacked the symptoms of disease without paying any attention to the causes thereof, but natural healing is concerned far more with removing the causes of disease, than merely curing its symptoms. This is the glory of this new school of medicine that it cures by removing the causes of the ailment, and is the only rational method of practicing medicine. It begins its cures by avoiding the uses of drugs and hence is styled the system of drugless healing.

The Program of Naturopathic Cure

Natural healing is the most desirable factor in the regeneration of the race. It is a return to nature in methods of living and treatment. It makes use of the elementary forces of nature, of chemical selection of foods that will constitute a correct medical dietary. The diet of civilized man is devitalized, is poor in essential organic salts. The fact that foods are cooked in so many ways and are salted, spiced, sweetened and otherwise made attractive to the palate, induces people to over-eat, and over eating does more harm than under feeding. High protein food and lazy habits are the cause of cancer, Bright’s disease, rheumatism and the poisons of autointoxication.

There is really but one healing force in existence and that is Nature herself, which means the inherent restorative power of the organism to overcome disease. Now the question is, can this power be appropriated and guided more readily by extrinsic or intrinsic methods? That is to say, is it more amenable to combat disease by irritating drugs, vaccines and serums employed by superstitious moderns, or by the bland intrinsic congenial forces of Natural Therapeutics, that are employed by this new school of medicine, that is Naturopathy, which is the only orthodox school of medicine? Are not these natural forces much more orthodox than the artificial resources of the druggist?

Schools of Thought That Formed the Philosophical Basis of Naturopathy

Because of the eclectic nature of naturopathic medicine, its history is by far the most complex of any healing art, which explains the unusually large portion of this chapter devoted to this subject. Although the following discussion is divided into distinct schools of thought, this is somewhat artificial, because those who founded and practiced these arts (especially the Americans) were often trained in, influenced by, and practiced several therapeutic systems or modalities. It was not until Benedict Lust, however, that the many threads were woven together into a unified professional practice, which makes naturopathic medicine the first Western system of full-scope integrative natural medicine based on the vis medicatrix naturae. Organized around this principle of the human capacity for healing, naturopathic medicine has been able to discriminately integrate diverse therapeutic systems and modalities into a cohesive framework, acknowledging the biomedical model of health and illness, but also supporting the whole person, including the psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of wellness. It has consistently promoted a patient-centered relationship, as well as collaboration with other health care professionals and disciplines, and today is poised as a model for integrative medicine. Although it draws from the eclectic tradition (see later), it does not do so randomly or indiscriminately. Rather, core principles, such as the vis medicatrix naturae, guide its flexible but solid structure, allowing it to navigate, perhaps uniquely, today’s medical world.

The following presents the formative schools of Western thought in natural healing and some of their leading adherents. Although the therapies differ, the philosophical thread of promoting health and supporting the body’s own healing processes runs through them all. These threads are derived from centuries of medical scholarship, both Western and non-Western, concerning the self-healing process.

After a brief overview of Hippocrates’ seminal contribution to the natural medicine way of thought, the basic themes are presented in the following order: healthful living; natural diet; detoxification; exercise, mechanotherapy, and physical therapy; mental, emotional, and spiritual healing; and natural therapeutic agents. Hippocrates and centuries of nature doctors’ writings remain empirically rich repositories of observations for future research.

Hippocrates

Prehistoric people believed that disease was caused by magic or supernatural forces, such as devils or angry gods. Hippocrates, breaking with this superstitious belief, became the first naturalistic doctor in recorded history. Hippocrates regarded the body as a “whole” and instructed his students to prescribe only beneficial treatments and refrain from causing harm or hurt.

Hippocratic practitioners assumed that everything in nature had a rational basis; therefore the physician’s role was to understand and follow the laws of the intelligible universe. They viewed disease as an effect and looked for its cause in natural phenomena: air, water, food, and so forth. They first used the term vis medicatrix naturae, the “healing power of nature,” to denote the body’s ability and drive to heal itself. One of the central tenets is that “there is an order to the process of healing which requires certain things to be done before other things to maximize the effectiveness of the therapeutics” (Zeff, 1997). The step order used by Tibetan medicine is also an example of the representation of this tenet in traditional world medicines.

Hydrotherapy

The earliest philosophical origins of naturopathy were clearly in the Germanic hydrotherapy movement: the use of hot and cold water for the maintenance of health and the treatment of disease. One of the oldest known therapies (water was used therapeutically by the Romans and Greeks), hydrotherapy began its modern history with the publication of The History of Cold Bathing in 1697 by Sir John Floyer. Probably the strongest impetus for its use came from Central Europe, where it was advocated by such well-known hydropaths as Priessnitz, Schroth, and Father Kneipp. They were able to popularize specific water treatments that quickly became the vogue in Europe during the nineteenth century. Vinzenz Priessnitz (1799-1851), of Graefenberg, Silesia, was a pioneer natural healer. Unfortunately, he was prosecuted by the medical authorities of his day and was actually convicted of using witchcraft because he cured his patients by the use of water, air, diet, and exercise. He took his patients back to nature—to the woods, the streams, the open fields—treated them with nature’s own forces, and fed them on natural foods. His cured patients numbered in the thousands, and his fame spread over Europe. Father Sebastian Kneipp (1821-1897) became the most famous of the hydropaths, with Pope Leo XIII and Ferdinand of Austria (whom he had walking barefoot in new-fallen snow for the purposes of hardening his constitution) among his many famous patients. He standardized the practice of hydrotherapy and organized it into a system of practice that was widely emulated through the establishment of health spas or “sanitariums.” The first sanitarium in this country, the Kneipp and Nature Cure Sanitarium, was opened in Newark, New Jersey, in 1891.

The best-known American hydropath was J.H. Kellogg, a medical doctor who approached hydrotherapy scientifically and performed many experiments trying to understand the physiological effects of hot and cold water. In 1900 he published Rational Hydrotherapy, which is still considered a definitive treatise on the physiological and therapeutic effects of water, along with an extensive discussion of hydrotherapeutic techniques. Drs. O.J. Carroll, Harold Dick, and John Bastyr, among others, brought the use of hydrotherapy techniques forward into modern naturopathic practice.

Nature Cure

Natural living, consumption of a vegetarian diet, and the use of light and air formed the basis of the nature cure movement founded by Dr. Arnold Rickli (1823-1926). In 1848 he established at Veldes Krain, Austria, the first institution of light and air cure or, as it was called in Europe, the atmospheric cure. He was an ardent disciple of the vegetarian diet and the founder, and for more than 50 years the president, of the National Austrian Vegetarian Association. In 1891, Louis Kuhne (ca. 1823-1907) wrote the New Science of Healing, which presented the basic principles of “drugless methods.” Dr. Henry Lahman (ca. 1823-1907), who founded the largest nature cure institution in the world at Weisser Hirsch, near Dresden, Saxony, constructed the first appliances for the administration of electric light treatment and baths. He was the author of several books on diet, nature cure, and heliotherapy. Professor F.E. Bilz (1823-1903) authored the first natural medicine encyclopedia, The Natural Method of Healing, which was translated into a dozen languages, and in German alone ran into 150 editions.

Nature cure became popular in America through the efforts of Henry Lindlahr, MD, ND, of Chicago, Illinois. Originally a rising businessman in Chicago with all the bad habits of those in the Gay Nineties era, he became chronically ill while only in his thirties. After receiving no relief from the orthodox practitioners of his day, he learned of nature cure, which improved his health. Subsequently, he went to Germany to stay in a sanitarium to be cured and to learn nature cure. He went back to Chicago and earned his degrees from the Homeopathic/Eclectic College of Illinois. In 1903 he opened a sanitarium in Elmhurst, Illinois; established Lindlahr’s Health Food Store; and shortly thereafter founded the Lindlahr College of Natural Therapeutics. In 1908 he began to publish Nature Cure Magazine and began publishing his six-volume series of Philosophy of Natural Therapeutics.

One of the chief advantages of training in the early 1900s was the marvelous inpatient facilities that flourished during this time. These facilities provided in-depth training in clinical nature cure and natural hygiene in inpatient settings. Nature cure and natural hygiene are still at the core of naturopathic medicine’s fundamental principles and approach to health care and disease prevention.

The Hygienic System

Another forerunner of American naturopathy, the “hygienic” school, amalgamated the hydrotherapy and nature cure movements with vegetarianism. It originated as a lay movement of the nineteenth century and had its genesis in the popular teachings of Sylvester Graham and William Alcott. Graham began preaching the doctrines of temperance and hygiene in 1830 and in 1839 published Lectures on the Science of Human Life, two hefty volumes that prescribed healthy dietary habits. He emphasized a moderate lifestyle, a flesh-free diet, and bran bread as an alternative to bolted or white bread. The earliest physician to have a significant impact on the hygienic movement and the later philosophical growth of naturopathy was Russell Trall, MD. According to Whorton (1982) in his Crusaders for Fitness,

The exemplar of the physical educator-hydropath was Russell Thatcher Trall. Still another physician who had lost his faith in regular therapy, Trall opened the second water cure establishment in America, in New York City in 1844. Immediately, he combined the full Priessnitzian armamentarium of baths with regulation of diet, air, exercise and sleep. He would eventually open and or direct any number of other hydropathic institutions around the country, as well as edit the Water-Cure Journal, the Hydropathic Review, and a temperance journal. He authored several books, including popular sex manuals which perpetuated Graham-like concepts into the 1890’s, sold Graham crackers and physiology texts at his New York office, was a charter member (and officer) of the American Vegetarian Society, presided over a short-lived World Health Association, and so on.

Trall established the first school of natural healing arts in this country to have a 4-year curriculum and the authorization to confer the degree of MD. It was founded in 1852 as a “Hydropathic and Physiological School” and was chartered by the New York State Legislature in 1857 under the name New York Hygio-Therapeutic College.

Trall eventually published more than 25 books on the subjects of physiology, hydropathy, hygiene, vegetarianism, and temperance, among many others. The most valuable and enduring of these was his 1851 Hydropathic Encyclopedia, a volume of nearly 1000 pages that covered the theory and practice of hydropathy and the philosophy and treatment of diseases advanced by older schools of medicine. The encyclopedia sold more than 40,000 copies.

Martin Luther Holbrook expanded on the work of Graham, Alcott, and Trall and, working with an awareness of the European concepts developed by Priessnitz and Kneipp, laid further groundwork for the concepts later advanced by Lust, Lindlahr, and others. According to Whorton (1982), Holbrook proposed the following:

For disease to result, the latter had to provide a suitable culture medium, had to be susceptible. As yet, most physicians were still so excited at having discovered the causative agents of infection that they were paying less than adequate notice to the host. Radical hygienists, however, were bent just as far in the other direction. They were inclined to see bacteria as merely impotent organisms that throve only in individuals whose hygienic carelessness had made their body compost heaps. Tuberculosis is contagious, Holbrook acknowledged, but “the degree of vital resistance is the real element of protection. When there is no preparation of the soil by heredity, predisposition or lowered health standard, the individual is amply guarded against the attack.” A theory favored by many others was that germs were the effect of disease rather than its cause; tissues corrupted by poor hygiene offered microbes, all harmless, an environment in which they could thrive.

The orthodox hygienists of the progressive years were equally enthused by the recent progress of nutrition, of course, and exploited it for their own naturopathic doctors, but their utilization of science hardly stopped with dietetics. Medical bacteriology was another area of remarkable discovery, bacteriologists having provided, in the short space of the last quarter of the nineteenth century, an understanding, at long last, of the nature of infection. This new science’s implications for hygienic ideology were profound—when Holbrook locked horns with female fashion, for example, he did not attack the bulky, ground-length skirts still in style with the crude Grahamite objection that the skirt was too heavy. Rather he forced a gasp from his readers with an account of watching a smartly dressed lady unwittingly drag her skirt “over some virulent, revolting looking sputum, which some unfortunate consumptive had expectorated.”

Trall and Holbrook both advanced the idea that physicians should teach the maintenance of health rather than simply provide a last resort in times of health crisis. Besides providing a strong editorial voice denouncing the evils of tobacco and drugs, they strongly advanced the value of vegetarianism, bathing and exercise, dietetics and nutrition along with personal hygiene.

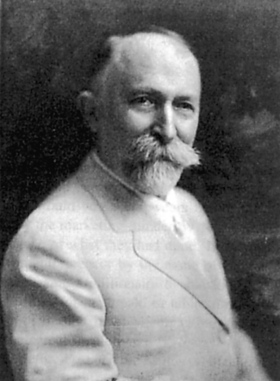

John Harvey Kellogg, MD, another medically trained doctor who turned to more nutritionally based natural healing concepts, also greatly influenced Lust. Kellogg was renowned through his connection, beginning in 1876, with the Battle Creek Sanitarium, which was founded in the 1860s as a Seventh Day Adventist institution designed to perpetuate the Grahamite philosophies. Kellogg, born in 1852, was a “sickly child” who, at age 14, after reading the works of Graham, converted to vegetarianism. At the age of 20, he studied for a term at Trall’s Hygio-Therapeutic College and then earned a medical degree at New York’s Bellevue Medical School. He maintained an affiliation with the regular schools of medicine during his lifetime, more because of his practice of surgery than because of his beliefs in that area of health care (Figure 21-4)

Figure 21-4 Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, brother to the Kellogg of breakfast cereal fame and a physical culture movement proponent.

(Courtesy Historical Society of Battle Creek, Battle Creek, Mich.)

Kellogg designated his concepts, which were basically the hygienic system of healthful living, as “biologic living.” Kellogg expounded vegetarianism, attacked sexual misconduct and the evils of alcohol, and was a prolific writer through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He produced a popular periodical, Good Health, which continued in existence until 1955. When Kellogg died in 1943 at age 91, he had had more than 300,000 patients through the Battle Creek Sanitarium, including many celebrities, and the “San” became nationally known.

Kellogg was also extremely interested in hydrotherapy. In the 1890s he established a laboratory at the San to study the clinical applications of hydrotherapy. This led to his writing of Rational Hydrotherapy in 1902. The preface espoused a philosophy of drugless healing that came to be one of the bases of the hydrotherapy school of medical thought in early-twentieth-century America.

Influence on Public Health

It is a little-known fact that most of our current and accepted public hygiene practices were brought into societal use by the early hygienic reformers. Before their efforts, neglect of these basic physiological safety measures was rampant. The hygienists had a great influence on decreasing morbidity and mortality and increasing life span, as well as on the adoption of public sanitation. Orthodox medicine is typically credited with these advances.

Currently, certified professional Natural Hygienists are advocates of the highest standards of training and supervised clinical fasting and participate in the training of naturopathic physicians. Naturopathic medicine uses the precepts of natural hygiene in reestablishing the basis of health, the first step in the therapeutic order.

Autotoxicity

Lust was also greatly influenced by the writings of John H. Tilden, MD (who published between 1915 and 1925). Tilden became disenchanted with orthodox medicine and began to rely heavily on dietetics and nutrition, formulating his theories of “autointoxication” (the effect of fecal matter’s remaining too long in the digestive process) and “toxemia.” He provided the natural health care literature with a 200-plus-page dissertation entitled Constipation, with a whole chapter devoted to the evils of not responding “when nature called.”

Elie Metchnikoff (director of the prestigious Pasteur Institute and winner of the 1908 Nobel Prize for his contribution to immunology) and Kellogg wrote prolifically on the theory of autointoxication. Kellogg, in particular, believed that humans, in the process of digesting meat, produced a variety of intestinal self-poisons that contributed to autointoxication. As a result, Kellogg widely advocated that people return to a more healthy natural state by allowing the naturally designed use of the colon. He believed that the average modern colon was devitalized by the combination of a low-fiber diet, sedentary living, the custom of sitting rather than squatting to defecate, and the modern civilized habit of ignoring “nature’s call” out of an undue concern for politeness.

Although the concept of toxemia is not a part of the body of knowledge taught in conventional medical schools, all naturopathic students are presented with this concept. Some of that presentation relies on outdated materials, such as the naturopathic texts of 75 and 100 years ago (e.g., Lindlahr, Tilden). However, modern research and textbooks are beginning to investigate this phenomenon. Drasar and Hill’s Human Intestinal Flora (1974) demonstrates some of the biochemical pathways involved in the generation of metabolic toxins in the gut through dysbiotic bacterial action on poorly digested food (Zeff, 1997). In the last 20 years, our understanding of the concept of toxemia has been significantly updated by practitioners in the newly emerging field of functional medicine, a health care approach that focuses attention on biochemical individuality, metabolic balance, ecological context, and unique personal experience in the dynamics of health. Maldigestion, malabsorption, and abnormal gut flora and ecology are often found to be primary contributing factors not only to gastrointestinal disorders but also to a wide variety of chronic, systemic illnesses. Laboratory assessment tools have been developed that are capable of evaluating the status of many organs, including the gastrointestinal tract. These cutting-edge diagnostic tools provide physicians with an analysis of numerous functional parameters of the individual’s digestion and absorption and precisely pinpoint what in the colonic environment is imbalanced, thus promoting dysbiosis.

Thomsonianism

In 1822, Samuel Thomson published his New Guide to Health, a compilation of his personal view of medical theory and American Indian herbal and medical botanical lore. Thomson espoused the belief that disease had one general cause—derangement of the vital fluids by “cold” influences on the human body—and that disease therefore had one general remedy—animal warmth or “heat.” The name of the complaint depended on the part of the body that was affected. Unlike the conventional American heroic medical tradition that advocated bloodletting, leeching, and the substantial use of mineral-based purgatives such as antimony and mercury, Thomson believed that minerals were sources of “cold” because they come from the ground and that vegetation, which grew toward the sun, represented “heat” (Figure 21-5).

Thomson’s view was that individuals could self-treat if they had an adequate understanding of his philosophy and a copy of New Guide to Health. The right to sell “family franchises” for use of the Thomsonian method of healing was the basis of a profound lay movement between 1822 and Thomson’s death in 1843. Thomson adamantly believed that no professional medical class should exist and that democratic medicine was best practiced by laypersons within a Thomsonian “family” unit. By 1839 Thomson claimed to have sold some 100,000 of these family franchises, called “friendly botanic societies.”

Despite his criticism of the early medical movement for its heroic tendencies, Thomson’s medical theories were heroic in their own fashion. Although he did not advocate bloodletting or heavy metal poisoning and leeching, botanical purgatives—particularly Lobelia inflata (Indian tobacco)—were a substantial part of the therapy.

Eclectic School of Medicine

Some of the doctors practicing the Thomsonian method, called botanics, decided to separate themselves from the lay movement and develop a more physiologically sound basis of therapy. They established a broader range of therapeutic applications of botanical medicines and founded a medical college in Cincinnati. These Thomsonian doctors were later absorbed into the “eclectic school,” which originated with Wooster Beach of New York.

Wooster Beach, from a well-established New England family, started his medical studies at an early age, apprenticing under an old German herbal doctor, Jacob Tidd, until Tidd died. Beach then enrolled in the Barclay Street Medical University in New York. After opening his own practice in New York, Beach set out to win over fellow members of the New York Medical Society (into which he had been warmly introduced by the screening committee) to his point of view that heroic medicine was inherently dangerous and should be reduced to the gentler theories of herbal medicine. He was summarily ostracized from the medical society. He soon founded his own school in New York, calling the clinic and educational facility the United States Infirmary. Because of political pressure from the medical society, however, he was unable to obtain charter authority to issue legitimate diplomas. He then located a financially ailing but legally chartered school, Worthington College, in Worthington, Ohio. There he opened a full-scale medical college, creating the eclectic school of medical theory based on the European, Native American, and American traditions. The most enduring eclectic herbal textbook is King’s American Dispensary by Harvey Wickes Felter and John Uri Lloyd. Published in 1898, this two-volume 2500-page treatise provided the definitive work describing the identification, preparation, pharmacognosy, history of use, and clinical application of more than 1000 botanical medicines. The eclectic herbal lore formed an integral core of the therapeutic armamentarium of the naturopathic doctor (ND).

Homeopathic Medicine

Homeopathy, the creation of an early German physician, Samuel Hahnemann (1755-1843), had four central doctrines: (1) that like cures like (the “law of similars”); (2) that the effect of a medication could be heightened by its administration in minute doses (the more diluted the dose, the greater the “dynamic” effect); (3) that nearly all diseases were the result of a suppressed itch, or “psora”; and (4) that healing proceeds from within outward, above downward, from more vital to less vital organs, and in the reverse order of the appearance of symptoms (pathobiography), known as Hering’s law.

Originally, most U.S. homeopaths were converted orthodox medical doctors, or allopaths (a term coined by Hahnemann). The high rate of conversion made this particular medical sect the archenemy of the rising orthodox medical profession. The first American homeopathic medical school was founded in 1848 in Philadelphia; the last purely homeopathic medical school, based in Philadelphia, survived into the early 1930s (see Chapter 24).

Manipulative Therapies: Osteopathy and Chiropractic

In Missouri, Andrew Taylor Still, originally trained as an orthodox practitioner, founded the school of medical thought known as osteopathy. He conceived a system of healing that emphasized the primary importance of the structural integrity of the body, especially as it affects the vascular system, in the maintenance of health. In 1892 he opened the American School of Osteopathy in Kirksville, Missouri.

In 1895, Daniel David Palmer, originally a magnetic healer from Davenport, Iowa, performed the first spinal manipulation, which gave rise to the school he termed chiropractic. His philosophy was similar to Still’s except for a greater emphasis on the importance of proper neurological function. He formally published his findings in 1910, after having founded a chiropractic school in Davenport (see Chapter 18).

Less well known is “zone therapy,” originated by Joe Shelby Riley, DC, a chiropractor based in Washington, D.C. Zone therapy was an early forerunner of acupressure. In zone therapy, pressure to and manipulation of the fingers and tongue and percussion of the spinal column were applied according to the relation of points on these structures to certain zones of the body.

Christian Science and the Role of Belief and Spirituality

Christian Science, formulated by Mary Baker Eddy in 1879, comprises a profound belief in the role of systematic religious study (which led to the widespread Christian Science Reading Rooms), spirituality, and prayer in the treatment of disease. In 1875 she published Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, the definitive textbook for the study of Christian Science.

Lust was also influenced by the works of Sidney Weltmer, the founder of “suggestive therapeutics.” Weltmer’s work dealt specifically with the psychological process of desiring to be healthy. The theory behind Professor Weltmer’s work was that whether it was the mind or the body that first lost its grip on health, the two were inseparably related. When the problem originated in the body, the mind nonetheless lost its ability and desire to overcome the disease because the patient “felt sick” and consequently slid further into the diseased state. Alternatively, if the mind first lost its ability and desire to “be healthy” and some physical infirmity followed, the patient was susceptible to being overcome by disease (see Chapter 6).

Physical Culture

Bernarr Mcfadden, a close friend of Lust’s, founded the “physical culture” school of health and healing, also known as physcultopathy. This school of healing gave birth across the United States to gymnasiums where exercise programs were designed and taught to allow individual men and women to establish and maintain optimal physical health.

Although many theories exist to explain the rapid dissolution of these diverse healing arts (the practitioners of which at one time made up more than 25% of all U.S. health care practitioners) in the early part of the twentieth century, low ratings in the infamous Flexner Report (which rated all these schools of medical thought among the lowest), allopathic medicine’s anointing of itself with the blessing “scientific,” and the growing political sophistication of the AMA clearly played the most significant role.

All these healing systems and modalities were naturally unified in the field of naturopathic medicine because they shared one common tenet: respect for and inquiry into the self-healing process and what was necessary to establish health.

Halcyon Days of Naturopathy

In the early 1920s the “health fad” movement was reaching its peak in terms of public awareness and interest. Conventions were held throughout the United States, one of which was attended by several members of Congress, culminating in full legalization of naturopathy as a healing art in the District of Columbia. Not only were the conventions well attended by professionals, but the public also flocked to them, with more than 10,000 attending the 1924 convention in Los Angeles.

During the 1920s and up until 1937, naturopathy was in its most popular phase. Although the institutions of the orthodox school had gained ascendancy, before 1937 the medical profession had no real solutions to the problems of human disease.

During the 1920s, Gaylord Hauser, later to become the health food guru of the Hollywood set, came to Lust as a seriously ill young man. Lust, through application of the nature cure, removed Hauser’s afflictions and was rewarded by Hauser’s lifelong devotion. His regular columns in Nature’s Path became widely read among the Hollywood crowd.

The naturopathic journals of the 1920s and 1930s provide much valuable insight into the prevention of disease and the promotion of health. Much of the dietary advice focused on correcting poor eating habits, including the lack of fiber in the diet and an overreliance on red meat as a protein source. As in the 1990s, we now hear the pronouncements of the orthodox profession, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the National Cancer Institute that the early assertions of the naturopaths that such dietary habits would lead to degenerative diseases, including colon cancer and other cancers of the digestive tract, were true.

The December 1928 issue of Nature’s Path contained the first American publication of the work of Herman J. DeWolff, a Dutch epidemiologist. DeWolff was one of the first researchers to assert, on the basis of studies of the incidence of cancer in the Netherlands, that there was a correlation between exposure to petrochemicals and various types of cancerous conditions. He contended that the use of chemical fertilizers and their application in some soils (principally clay) led to their remaining in vegetables after they had arrived at the market and were purchased for consumption. It was almost 50 years before orthodox medicine began to see the wisdom of such assertions.

Suppression and Decline

In 1937 the popularity of naturopathy began to decline. The change came, as both Thomas and Campion note in their works, with the era of “miracle medicine.” Lust recognized this, and his editorializing became, if anything, even more strident. From the introduction of sulfa drugs in 1937 to the release of the Salk vaccine in 1955, the American public became used to annual developments of miracle vaccines and antibiotics. The naturopathic profession adhered to its vitalistic philosophy and a full range of practice but unfortunately was poorly unified at this time on other issues of standards. This made the profession vulnerable to interguild competition.

Lust died in September 1945 in residence at the Yungborn facility in Butler, New Jersey, preparing to attend the 49th Annual Congress of his American Naturopathic Association. Although a healthy, vigorous man, he had seriously damaged his lungs the previous year saving patients when a wing of his facility caught fire; he never fully recovered. On August 30, 1945, writing for the official program of that congress, held in October 1945 just after his death, he noted his concerns for the future. He was especially frustrated with the success of the medical profession in blocking the efforts of naturopaths to establish state licensing laws that would not only establish appropriate practice rights for NDs but also protect the public from the pretenders (i.e., those who chose to call themselves naturopaths without ever bothering to undergo formal training). As Lust (1945) stated:

Now let us see the type of men and women who are the Naturopaths of today. Many of them are fine, upstanding individuals, believing fully in the effectiveness of their chosen profession—willing to give their all for the sake of alleviating human suffering and ready to fight for their rights to the last ditch. More power to them! But there are others who claim to be Naturopaths who are woeful misfits. Yes, and there are outright fakers and cheats masking as Naturopaths. That is the fate of any science—any profession—which the unjust laws have placed beyond the pale. Where there is no official recognition and regulation, you will find the plotters, the thieves, the charlatans operating on the same basis as the conscientious practitioners. And these riff-raff opportunists bring the whole art into disrepute. Frankly, such conditions cannot be remedied until suitable safeguards are erected by law, or by the profession itself, around the practice of Naturopathy. That will come in time.

In the mid-1920s, Morris Fishbein came on the scene as editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Fishbein took on a personal vendetta against what he characterized as “quackery.” Lust, among others, including Mcfadden, became Fishbein’s epitome of quackery. Unfortunately, he proved to be particularly effective politically and in the media.

The public infatuation with technology, the introduction of “miracle medicine,” World War II’s stimulation of the development of surgery, the Flexner Report, the growing political sophistication of the AMA under the leadership of Fishbein, intraprofession squabbles, and the death of Lust in 1945 all combined to cause the decline of naturopathic medicine and natural healing in the United States. In addition, these years, called the years of the great fear in David Caute’s book by the latter name, were the years during which to be unorthodox was to be un-American.

U.S. courts began to take the view that naturopaths were not truly doctors because they espoused doctrines from “the dark ages of medicine” (something American medicine had supposedly come out of in 1937) and that drugless healers were intended by law to operate without “drugs” (which came to be defined as anything a physician would prescribe for a patient to ingest or apply externally for any medical purpose). The persistent lack of uniform standards, lack of insurance coverage, lost court battles, a splintered profession, and a hostile legislative perspective progressively restricted practice until the core naturopathic therapies became essentially illegal and practices financially nonviable.

Although it was under considerable public pressure in those years, the American Naturopathic Association undertook some of its most scholarly work, coordinating all the systems of naturopathy under commission. This resulted in the publication of a formal textbook, Basic Naturopathy (Spitler, 1948) and a significant work compiling all the known theories of botanical medicine, Naturae Medicina (Kuts-Cheraux, 1953). Naturopathic medicine began splintering when Lust’s American Naturopathic Association was succeeded by six different organizations in the mid-1950s.

By the early 1970s, the profession’s educational institutions had dwindled to one: the National College of Naturopathic Medicine, with branches in Seattle and Portland, Oregon.

Naturopathic Medicine Reemerges

The combination of the counterculture years of the late 1960s, the public’s growing awareness of the importance of nutrition and the environment, and America’s disenchantment with organized institutional medicine (which began after the miracle era faded and it became apparent that orthodox medicine has its limitations and is prohibitively expensive) resulted in the emergence of new respect for alternative medicine in general and in the rejuvenation of naturopathic medicine. At this time, a new wave of students were attracted to the philosophical precepts of the profession. They brought with them an appreciation for the appropriate use of science, modern college education, and matching expectations for quality education.

Dr. John Bastyr (1912-1995) and his firm, efficient, professional leadership inspired science- and research-based training in natural medicine to begin to reach toward its full potential. Dr. Bastyr, whose vision was of “naturopathy’s empirical successes documented and proven by scientific methods,” was “himself a prototype for the modern naturopathic doctor, who culls the latest findings from the scientific literature, applies them in ways consistent with naturopathic principles, and verifies the results with appropriate studies.” Bastyr also saw “a tremendous expansion in both allopathic and naturopathic medical knowledge, and he played a major role in making sure the best of both were integrated into naturopathic medical education” (Kirchfield et al, 1994).

In response to the growth in public interest during the late 1970s, naturopathic colleges were established in Arizona (Arizona College of Naturopathic Medicine, 1977), Oregon (American College of Naturopathic Medicine, 1980), and California (Pacific College of Naturopathic Medicine, 1979). None of these three survived. In 1978 the John Bastyr College of Naturopathic Medicine (later renamed Bastyr University) was formed in Seattle by founding president Joseph E. Pizzorno, Jr., ND; Lester E. Griffith, ND; William Mitchell, ND; and Sheila Quinn to teach and develop science-based natural medicine. They believed that for the naturopathic profession to move back into the mainstream, it needed to establish accredited institutions, perform credible research, and establish itself as an integral part of the health care system. Bastyr University not only survived but thrived, and it became the first naturopathic college ever to become regionally accredited. In 1993, Michael Cronin, Kyle Cronin, and Konrad Kail, NDs, founded the Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine and Health Science in Scottsdale, Arizona. In 1997 the University of Bridgeport, with the leadership of Jim Sensenig, ND, founded the University of Bridgeport College of Naturopathic Medicine.

With five credible colleges (including the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine in Ontario), active research, an appreciation of the appropriate application of science to natural medicine education, and clinical practice, naturopathic medicine is well on the road to recovery.

A sixth promising naturopathic college, the Boucher Institute of Naturopathic Medicine, was established in January 2000 in Vancouver, British Columbia. Boucher Institute graduated its first class in May 2004.

Recent Influences

A tremendous amount of research providing scientific support for the principles of naturopathic medicine has been conducted at mainstream research centers and increasingly at naturopathic medical schools. In fact, allopathy is turning more to the use of naturopathic methods in the search for effective prescriptions for diseases that are currently intractable and expensive to treat (Werbach, 1996). It is now well established that nutritional factors are of major importance in the pathogenesis of both atherosclerosis and cancer, the two leading causes of death in Western countries, and studies validating their importance in the pathogenesis of many other diseases continue to be published. Much of the research now documenting the scientific foundations of naturopathic medicine practices and principles can be found in A Textbook of Natural Medicine (Pizzorno et al, 1985-1995). This two-volume, 200-chapter work contains 7500 citations to the peer-reviewed scientific literature documenting the efficacy of many natural medicine therapies.

Although the naturopaths were astute clinical observers and a century ago recognized many of the concepts that are now gaining popularity and are being supported by scientific data, the scientific tools of the time were inadequate to assess the validity of their concepts. In addition, as a group they seemed to have little inclination for the application of laboratory research, especially because “science” was the bludgeon used by the AMA to suppress the profession. This has now changed. In the past few decades a considerable amount of research has now provided the scientific documentation of many of the concepts of naturopathic medicine, and the new breed of scientifically trained naturopaths is using this research to continue development of the profession. The following sections describe a few of the most important trends.

Therapeutic Nutrition

Since 1929, when Christiaan Eijkman and Sir Frederick Hopkins shared the Nobel Prize in medicine and physiology for the discovery of vitamins, the role of these trace substances in clinical nutrition has been a matter of scientific investigation. The discovery that enzyme systems depended on essential nutrients provided the naturopathic profession with great insights into why an organically grown, whole-foods diet is so important for health. Formulation of the concept of “biochemical individuality” by nutritional biochemist Roger Williams in 1955 further developed these ideas and provided great insights into the unique nutritional needs of each individual and the way to correct inborn errors of metabolism and even treat specific diseases through the use of nutrient-rich foods or large doses of specific nutrients. Linus Pauling, the two-time Nobel Prize winner, originated the concept of “orthomolecular medicine” and provided further theoretical substantiation for the use of nutrients as therapeutic agents.

Functional Medicine

In 1990, Jeff Bland, PhD, coined the term functional medicine to describe a putatively science-based development of therapeutic nutrition for the prevention of illness and promotion of health. Focusing on biochemical individuality, metabolic balance, and the ecological context, functional medicine practitioners avail themselves of recently developed laboratory tests to pinpoint perceived imbalances in an individual’s biochemistry that are thought to cause a cascade of biological triggers, paving the way to suboptimal function, chronic illness, and degenerative disease. A broad range of functional laboratory assessment tools in the areas of digestion (gastrointestinal system), nutrition, detoxification and oxidative stress, immunology and allergy, production and regulation of hormones (endocrinology), and the heart and blood vessels (cardiovascular system) provide physicians with a basis to recommend nutritional interventions specific to the individual’s needs and to monitor their efficacy.

Environmental Medicine and Clinical Ecology

Although recognition of the clinical impact of environmental toxicity and endogenous toxicity has existed since the earliest days of naturopathy, it was not until the environmental movement and the seminal work of Rachel Carson and others that the scientific basis was established. Clinical research and the development of laboratory methods for assessing toxic load have provided objective tools that have greatly increased the sophistication of clinical practice. Clinical and laboratory methods were developed for the assessment of idiosyncratic reactions to environmental factors and foods.

Spirituality, Health, and Medicine

Naturopathic medicine’s philosophy of treating the whole person and enhancing the individual’s inherent healing ability is closely aligned with its mission of integrating spirituality into the healing process. Scientific evidence is growing on the part spirituality can play in healing. René Descartes has been accused of separating mind from body back in the seventeenth century, and medical science has attempted to explain disease independently of mind, in terms of germs, environmental agents, or wayward genes. At present, however, the evidence on the link between mind and body is not just clinical observation but chemical fact. An explosion of research in the new and rapidly expanding field of psychoneuroimmunology is revealing physical evidence of the mind-body connection that is changing our understanding of disease (see Chapter 8). Scientists no longer question whether but rather how our minds have an impact on our health, and the implications of the connections uncovered in only the last 20 years are extraordinary.

In his book Healing Words (1993), Larry Dossey, MD, pulls together what he describes as “one of the best kept secrets in medical science”: the extensive experimental evidence for the beneficial effects of prayer. Dossey reviews studies that provide evidence for a positive effect of prayer on not only humans but mice, chicks, enzymes, fungi, yeast, bacteria, and cells of various sorts. He emphasizes, “We cannot dismiss these outcomes as being due to suggestion or placebo effects, since these so-called lower forms of life do not think in any conventional sense and are presumably not susceptible to suggestion” (Pizzorno, 1995).

“Cutting-Edge” Laboratory Methods

A final significant influence has been the development of laboratory methods for the objective assessment of nutritional status, metabolic dysfunction, digestive function, bowel flora, endogenous and exogenous toxic load, liver detoxification and other system functions, and genomics. Each of these has provided ever more effective tools for accurate assessment of patient health status and effective application of naturopathic principles.

Genomics

One of the most exciting recent advances is genomic testing, the ability to evaluate each individual’s template for making the enzymes of life. This technology is now providing a level of objective evaluation of biochemical individuality never before available, greatly strengthening the naturopathic doctor’s ability to practice personalized medicine. The ability to assess each individual’s unique nutrient needs as well as susceptibilities to environmental toxins promises to change fundamentally the practice of medicine (Pizzorno, 2003).

During the last several years, as America’s staggering health care debt accumulates because of the increase in chronic disease, these core, traditional naturopathic principles are surfacing widely as central to creating an effective health care system, as follows:

Current medical education inculcates many of the dominant values of modern medicine: reductionism, specialization, mechanistic models of disease, and faith in a definitive cure. . . . What is needed is a model of care that addresses the whole person and integrates care for the person’s entire constellation of comorbidities. . . . Nothing short of a fundamental redesign of primary care systems is required. (Grumbach, 2003)

PRINCIPLES

Although in many ways, modern medicine resembles a science, it continues to be criticized for its lack of unifying theories, and for this reason alone its claim to being a science has remained suspect.

What physicians think medicine is profoundly shapes what they do, how they behave in doing it, and the reasons they use to justify that behavior. . . . Whether conscious of it or not, every physician has an answer to what he thinks medicine is, with real consequences for all whom he attends. . . . The outcome is hardly trivial. . . . It dictates, after all, how we approach patients [and] how we make clinical judgments.

Medical philosophy comprises the underlying premises on which a healthcare system is based. Once a system is acknowledged, it is subject to debate. In naturopathic medicine, the philosophical debate is a valuable, ongoing process which helps the understanding that disease evolves in an orderly and truth-revealing fashion.

Naturopathic medicine is a distinct system of health-oriented medicine that, in contrast to the currently dominant disease-treatment system, stresses promotion of health, prevention of disease, patient education, and self-responsibility. However, naturopathic medicine symbolizes more than simply a health care system; it is a way of life. Unlike most other health care systems, naturopathy is not identified with any particular therapy but rather is a way of thinking about life, health, and disease. It is defined not by the therapies it uses but by the philosophical principles that guide the practitioner.

Seven powerful concepts provide the foundation that defines naturopathic medicine and create a unique group of professionals practicing a form of medicine that fundamentally changes the way we think of health care. In 1989 the American Association of Naturopathic Physicians unanimously approved the definition of naturopathic medicine, updating and reconfirming in modern terms its core principles as a professional consensus. “The definition and principles of practice provide a steady point of reference for this debate, for our evolving understanding of health and disease, and for all of our decision making processes as a profession” (Snider et al, 1988).

The seven core principles of naturopathic medicine are as follows, with “wellness and health promotion” emerging into the forefront of the scholarly discussion of naturopathic clinical theory:

The Healing Power of Nature (vis medicatrix naturae)

Belief in the ability of the body to heal itself—the vis medicatrix naturae (the healing power of nature)—if given the proper opportunity, and the importance of living within the laws of nature is the foundation of naturopathic medicine. Although the term naturopathy was coined in the late nineteenth century, its philosophical roots can be traced back to Hippocrates and derive from a common wellspring in traditional world medicines: belief in the healing power of nature.

Medicine has long grappled with the question of the existence of the vis medicatrix naturae. As Neuberger stated, “The problem of the healing power of nature is a great, perhaps the greatest of all problems which has occupied the physician for thousands of years. Indeed, the aims and limits of therapeutics are determined by its solution.” The fundamental reality of the vis medicatrix naturae was a basic tenet of the Hippocratic school of medicine, and “every important medical author since has had to take a position for or against it” (Neuberger, 1932).

When standard medicine soundly rejected the principle of the vis medicatrix naturae at the turn of the twentieth century, nature doctors, including naturopathic physicians in the United States from 1896 on, diverged from conventional medicine. Naturopathic physicians recognized the clinical importance of the inherent self-healing process; embraced it as their core academic and clinical principle; and developed an entire system of medical practice, training, and research based on it and on related principles of clinical medicine.

Naturopathic medicine is therefore “vitalistic” in its approach (i.e., life is viewed as more than just the sum of biochemical processes), and the body is believed to have an innate intelligence or process (the vis medicatrix naturae), which is always striving toward health. Vitalism maintains that the symptoms accompanying disease are not typically caused by the morbific agent (e.g., bacteria); rather, they are the result of the organism’s intrinsic response or reaction to the agent and the organism’s attempt to defend and heal itself (Lindlahr, 1914a; Neuberger, 1932). Symptoms are part of a constructive phenomenon that is the best “choice” the organism can make, given the circumstances. In this construct the physician’s role is to understand and aid the body’s efforts, not to take over or manipulate the functions of the body, unless the self-healing process has become weak or insufficient.