Whether pointing to loved ones or inspirational ties, book dedications are a public declaration of an important relationship. Dedications can be decoded to reveal latent stories behind a few inscribed words. L.M. Montgomery’s “To the Memory of” always carries deep meaning. Montgomery wrote twenty-one books into which she inserted dedications to people (or pets) who enhanced her personal or creative life and to places that inspired her.

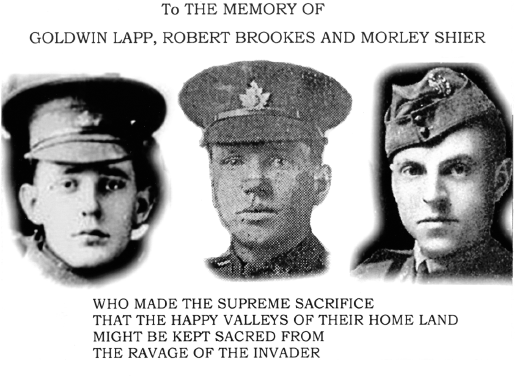

Two of these dedications are connected to the years Montgomery lived in Leaskdale, Ontario, preceding, during, and following the First World War. Her two Ontario-related dedications are in Rainbow Valley (1919) and its sequel, Rilla of Ingleside (1921). Rainbow Valley spotlights three young men from her husband’s, Reverend Ewan Macdonald’s, congregations who perished while serving in Canada’s forces in Europe between 1917 and 1918: “To the memory of Goldwin Lapp, Robert Brookes, and Morley Shier, who made the supreme sacrifice that the happy valleys of their home land might be kept sacred from the ravage of the invader.”1 Rilla of Ingleside is dedicated to Montgomery’s cousin (known as Frede): “To the memory of FREDERICA CAMPBELL MACFARLANE who went away from me when the dawn broke on January 25th, 1919 – a true friend, a rare personality, a loyal and courageous soul.” The dedication of Rainbow Valley is the only one Montgomery ever made to people whom she knew after 1904 and after she became famous. However, these dedications are not simply memorials to those who served and died or whom she loved and mourned; they are also invitations to unearth the interconnected stories of those whom Montgomery urges us to remember.2

2.1 Three Leaskdale First World War soldiers

On 3 October 1911, Montgomery as Mrs Ewan Macdonald was inducted as the minister’s new wife and honoured with a reception dinner at St Paul’s Presbyterian Church. Dressed in her wedding gown, she stood at the front of the sanctuary, while Ewan, who had lived in the community for two years, introduced her to his Leaskdale and Zephyr congregations. Margaret Leask Mustard, then seven years old, was in “awe” of Montgomery’s fame and recalls that the community was “honoured in having this already famous person as a resident.”3 Three of the families she met that evening – the Shiers, the Brookses, and the Lapps – would never have expected to be mentioned in her books. Catherine and James Shier’s farm was located a few acres away from the Leaskdale church.4 They had three children in 1911: Mabel was nineteen; Morley, sixteen, was a student at Uxbridge High School; and Harvey was nine. The Brooks family was in Ewan’s Zephyr congregation. A hard-working, twenty-five-year-old farmer, Robert lived with his mother, Catherine, and thirty-year-old sister, Janet, when he met the minister’s new wife. George Lapp was a farmer and the past reeve/mayor of the township; his wife, Effie Wright, was from Uxbridge. Their oldest son, Ford, was nineteen; Goldwin was almost eighteen and in his last year of school in Uxbridge; Dorothy was thirteen and little Harvey three.

2.2 Leaskdale allotment map

The sons would have known the Macdonalds for only a few years, but their families and relations became friends, especially the younger siblings (Harvey Shier and Dorothy and Harvey Lapp) because they grew up during the fourteen years that Montgomery created and directed the Young People’s Association. Ewan provided the Presbyterians with two important assets: a mature minister who was a long-term resident and, as an added and significant bonus, a wife whose energy and talent would touch every aspect of the local life. The church youth adored her and appreciated her love of learning and guidance in debates, plays, and recitations.5 Many of these young people became loyal friends and remained in contact with her as adults, giving her the opportunity to stay current with their evolving life stories and life in the Leaskdale community. Margaret Mustard, for example, visited Montgomery up until a week before the author died in 1942. As Elizabeth Waterston points out in the previous chapter, Shier and Lapp were adolescents in the Young People’s Association when Montgomery arrived in 1911, and afterwards, they were poised to move on into adulthood; she did not know the young men well, but she shared in their lives and stories through their siblings and parents.

Morley Roy Shier knew “Mrs Mac” for about two years before he left to attend the University of Toronto’s teacher-preparation program. Robert Forrest (Bob) Brooks was in Ewan’s congregation for about six years before he enlisted. Goldwin Dimma (Goldie) Lapp was at home for only a year before leaving for Toronto to work and study pharmacy. They joined different military units at different times between 1915 and 1917.6 These three young men represent the sacrifices that small communities all over Canada invested in the world conflict. Just as their stories are the very real stories of communities throughout Canada, Rainbow Valley and Rilla of Ingleside are their fictional counterparts. Montgomery planned, wrote, and revised Rainbow Valley during the final years of the war, from 1917 to 1918; it is, appropriately, the story of the children in Anne and Gilbert’s Prince Edward Island village of Glen St Mary who reach maturity in the last years of innocence before they are pulled into war. Montgomery penned the dedication to the pilot Morley Shier and the two soldiers Bob Brooks and Goldie Lapp, when she finished the Rainbow Valley manuscript in late December 1918, three months after the death of the last casualty, Flight Lieutenant Shier.

Several Shier family members were Montgomery’s friends, including Morley’s cousin, Mary Shier McLeod. Mary often took part in community and church programs but left Leaskdale in 1913 to work at the Mail and Empire in Toronto. Readers of Montgomery’s journals will recall Morley’s uncle, Dr Walter Columbus Shier, who was a physician in Leaskdale and Uxbridge. Dr Shier attended the Macdonald family and was the first doctor to treat Ewan’s depression. Another uncle was Rob Shier who lived in Zephyr; his third wife was Lillis Harrison (Lily Reid), Montgomery’s household helper from 1912 to 1915 and a trusted friend throughout Montgomery’s life.

Morley was a teacher, first at Corson’s Siding, northeast of Leaskdale, and then at Earl Grey School in Toronto. Shortly after Montgomery began work on Rainbow Valley, Morley started pilot training. Planes could be seen in the air from Toronto to Georgian Bay in 1917. A local Uxbridge historian, Allan McGillivray, observes, “Something that brought the war feeling to Scott [Township] was the sight of planes travelling overhead . . . In August of 1917, the paper noted that four planes had been seen over Zephyr.”7 Montgomery creates just such a “war feeling” for even a village as far removed from the action as Glen St Mary when, in Rilla of Ingleside, the Blythes and Susan Barker watch a plane, “like a great bird poised against the western sky,” and imagine “Shirley away up there in the clouds, flying over to the Island from Kingsport.”8 Morley joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in November 1917. Later that month, Montgomery wrote to her life-long correspondent, Ephraim Weber, “A friend of mine in the Flying Corps told me that when he first went up he felt neither elated nor frightened – only desperately lonely and homesick – as if he were adrift in space – like a lost star,” sentiments that Montgomery gave almost verbatim to Shirley Blythe after his first flight in the flying corps.9 The corps pilots were housed at the University of Toronto and trained at Armour Heights Field in North Toronto. During Morley’s training, fatality records were improved greatly; however, there were sometimes more than two dozen crashes each day, and the airfields were littered with plane debris. Michael Skeet cites examples of “pilots learn[ing] to fly by the seat of their pants: resting hands and feet lightly on the controls while the instructor flew the plane” and of “a typical day (21 October 1917), [when] C.H. Andrews recorded 17 crashes at his training squadron.” Although 129 RFC Canadian cadets died in training, fatalities of British cadets numbered in the thousands.10 Susan’s fear of Shirley’s “machine crashing down – the life crushed out of his body”11 is well warranted.

Morley went to England in May 1918, after basic flight training, to learn combat and reconnaissance skills at the British advanced flying schools.12 He was assigned to the 256th Royal Air Force Squadron, formed in June 1918 at Seahouses, Northumberland, a busy fishing port not far from the Farne Islands and the border with Scotland (where the Macdonalds stayed during their honeymoon). The squadron did coastal surveillance for German submarines and flew two-seater, Canadian-built de Havilland DH-6 planes, with a range of about four hours of flight. One of the many nicknames for the DH-6 was “the Flying Coffin.”13 Shier became an active RFC pilot in July 1918 at the age of twenty-three. About one-quarter of the RFC squadron crews were Canadian.14 Most RFC combat pilots survived an average of about three weeks once they began their combat flights. Although reconnaissance pilots were not exposed to enemy fire as often as combat pilots, the risk to them was still significant; they were not armed but could carry bombs, and parachutes were not allowed because they were too heavy.15 Planes took off from a field just inland from Seahouses to patrol the misty coast for German U-boats. Pilots located and chased U-boats, forcing them to stay below the surface of the sea where they could not communicate, lay mines, or observe and attack ships. In this way, Britain kept control of the North Sea in the last year of the war.16

After two months of flying, Flight Lieutenant Shier and his plane went down in the fog in the North Sea on 6 September 1918, about twenty miles from shore. When he died, Montgomery was enjoying a long visit from her Aunt Annie Campbell. In the first week of September 1918, they viewed Hearts of the World, a First World War film set in France and made at the request of the British government to spur the United States out of neutrality. Montgomery saw the film, which she deemed “a wonderful thing,” because her half-brother Carl, who had taken part in the battle of Courcelette featured in the movie, had told her stories whose landmarks she wanted to identify. Another attraction was a story that Annie’s daughter, Frede Campbell, had relayed of attending the film in Montreal and becoming “so excited by the realism of the thing” that she yelled out a warning to the actress on the screen.17 Montgomery was upbeat and happy after a summer trip to the Island and optimistic about the end of the war. She did not hear of Morley’s death until a month later, three days before Germany and Austria agreed to peace in October 1918. He was one of the last local men to die before the war was over. Second Lieutenant Morley Shier’s name is on the Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton, England, erected by the Imperial War Graves Commission with the names of those lost at sea. About one-third of the officers and men on the memorial are from Canada. Members of the Shier family placed a marker in the cemetery in Leaskdale and a plaque in the church to honour him at home.

Another member of Ewan’s congregation to make the “supreme sacrifice” to protect “the happy valleys” of his home was Bob Brooks, several years older than most local enlistees and, unlike Goldwin and Morley, part of the battalion comprised of young men who lived near the Macdonalds. The battalion was formed in September 1915 by Sam Sharpe, an Uxbridge lawyer and member of the House of Commons; Sharpe’s wife, Mabel, was Montgomery’s friend through their membership in the Uxbridge Hypatia Club, a women’s discussion group about books and authors. The 116th Battalion was part of the 3rd Division of the Canadian Corps and took part in all the major battles in France and Belgium, earning honours wherever it fought.

Private Bob Brooks took a leave from training in Uxbridge in March 1916 to go home to Zephyr and sell his machinery, horses, and livestock. His mother had passed away by then, and his sister, Janet, was displeased that he was closing down the prosperous farm. But Bob was unmarried with no dependents and felt that he was needed more in the fields of Flanders than the fields of Zephyr.18 Later he arranged for Janet and her husband, Jake Meyers (the couple had been married by Ewan in 1914), to take over the farm. The recruits from Zephyr, Leaskdale, and Uxbridge, whom Sam Sharpe had trained so well, did what was required. For over two-and-a-half years, they moved in endless marches from one battle to another, carried bombs, set communication wire under fire, cut barbed wire, and built trenches and roadways. They lived in constant cold and wet, suffered gas attacks, and fought the enemy in acres of knee-deep mud and shell-torn burial grounds at Vimy Ridge, the Méricourt trench, Ypres at the Passchendaele Ridge, and Amiens.19 Private Brooks received a field promotion to sergeant during the last half of 1917. After Passchendaele, Colonel Sharpe could find no relief from the exhaustion and the images of waste and carnage he had experienced, and he killed himself after he was sent back to Ontario in May 1918. He was loved and respected by his men, setting a courageous example for his troops with his own actions in No Man’s Land and keeping the battalion together so neighbours could serve side by side, when many other units were split up as reinforcements.20

Near the end of the war, the 116th Battalion prepared for the Hundred Days Offensive that broke the German resistance. On 8 August 1918, at 4:28 a.m., the 116th attacked in a heavy dark mist in the Luce Valley, fighting the retreating enemy for three hours. Sergeant Brooks died sometime early that morning, five weeks before his thirty-second birthday. Lieutenant-Colonel George Randolph Pearkes wrote, “He led his platoon to their objective and well past it, but was killed early in the morning of August 8 in the third battle of the Somme while helping a wounded comrade to safety. He was a good soldier, keen, and showed marked ability in the leadership of men. His loss to his company cannot be overestimated.”21 As Jerry Meredith writes in Rilla of Ingleside of Walter’s earning a D.C Medal for the same brave act, “In any war but this . . . it would have meant a V.C.”22 Brooks was buried almost where he fell, with 143 others at Hourges Orchard Cemetery, Domart-sur-La-Luce, Somme, France, a cemetery that was created after the battle. His family received the news of his death in late August, and a memorial service was held in the Presbyterian Church in Zephyr on 1 September 1918.

Montgomery remained friends with Bob’s sister, Janet Meyers. Janet and her little daughter, Olive, were with the Macdonalds at the time of the car accident that would plague the next decade of their life with legal proceedings and fears of garnisheed wages. Ewan was driving everyone to the Meyers’ farm for tea after church when his car crashed into that of Zephyr resident Marshall Pickering. Janet testified on Ewan’s behalf in the lawsuit that Pickering launched and kept them informed of happenings and conversations in Zephyr about the accident. In 1925, their friendship cooled when Janet appeared to leave the Presbyterian congregation and considered moving to the newly formed Union Church.

A poem by A.B. Lundy, “Men of the One-Sixteen,” written for the 116th Battalion and published in the Port Perry Star, recalls Walter’s premonition about war in Rainbow Valley: “For they heard the bugle’s call, Sounding All! All! All! / While the throbbing of the drum / Answered Come! Come! Come!”23 Montgomery mirrors the cadence and sense of urgency of this poem by giving it a voice through Walter, still residing in a happy valley. The young Walter envisions the call to war as “the Pied Piper [who] will come over the hill up there and down Rainbow Valley, piping merrily and sweetly. And I will follow him – follow him down to the shore – down to the sea – away from you all. I don’t think I’ll want to go – Jem will want to go.”24

Goldwin Lapp was one of the boys from Leaskdale who, like Jem, first followed the call and enlisted when war was declared in August 1914. Goldwin is at the heart of a network of stories enmeshed with events that had especially painful personal associations for Montgomery. He signed his enlistment papers on 4 January 1915, joining one of the first authorized fighting units, the 20th (Central Ontario) Canadian Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, which had been mobilized in Toronto. After months of training, Goldwin left for England on the SS Megantic, the same ship that the Macdonalds had taken on their honeymoon trip. Goldwin’s first letter home on 23 May 1915 has been preserved and records the journey overseas. He told his mother about the daily routine, what life boat drills were like, his fear of torpedoes, and the Megantic’s escort ships, the British torpedo destroyers the Legion and the Lucifer.

Like most Canadians, the Macdonalds were immersed in the tension of a life focused on a far-away brutal conflict. Ewan was the chairman of the Scott Township Patriotic Committee and president of the War Resources Committee, responsible for recruiting soldiers. Montgomery hosted Red Cross activities in the manse and recited “In Flanders Fields” at recruitment meetings. Many of the young soldiers visited or shared meals with the Macdonalds before leaving for England. In church, the families cried while Ewan said prayers for the soldiers at the front and the new recruits still at home.

Since August 1914, Montgomery had deeply absorbed emotions of shock, grief, and anguish. She gave birth to a stillborn son within weeks of the beginning of the war, and the agony of that loss was overlaid with the grim daily war news. By the time Goldwin was boarding the Megantic, she was pregnant again. Throughout this period, her journals reveal that she was consumed with the sacrifice and suffering of mothers and children. She cried herself to sleep over stories of crimes against children in Belgium; she was ashamed at her relief that her own little boy was too young to be “sacrificed”; she, like Walter Blythe, was nauseated by the reports of fatalities of babies on the Lusitania. Her third son was born in October 1915. As a mother, she was deeply affected by the war news and could empathize completely with women like Effie Lapp, whose son was already on the battlefield and whose letters were undoubtedly shared with Montgomery by the worried parents.

By November of 1915, the women of Leaskdale had organized their own Red Cross Society; Montgomery was its president, Effie its treasurer. She admired Effie’s work ethic and ability to organize and lead. Montgomery suffered from her position as the minister’s wife because it constrained her from sharing the intensity of her feelings about the war with women in the parish. Likewise, other members of the congregation seem to have suppressed their own thoughts in her presence. As a result, she felt that many of her neighbours were not as affected by the war as she was, except for those whose sons had enlisted. But there were times when she and Effie worked alone together, and thus they developed a mutual respect and loyalty outside the group.25

Meanwhile, Goldwin was receiving special training for operations in the area of Lens, France, where the battalion was holding lines, patrolling, and raiding. He was a lance-corporal, second in command in a platoon, in charge of a section of about fifteen men. His nieces remember that “he could have been used as a spy as he looked like a German and spoke some German!”26 Because of his training as a pharmacist, he may have had duties as a medic. On 5 January 1917, the soldiers began constructing “dummy” German trenches in Bully Grenay to practise for a large offensive. The drills continued for eleven days in cold, wet, grey weather. It was windy and snowy on the morning of 17 January as the troops moved into position at 4:30 a.m. in Calonne, waiting for the code word “Lloyd George” to start the attack at 7:45 a.m. Battalions charged the Germans on an 850-yard front, destroying dugouts near the railway, blowing up ammunition dumps, and taking prisoners. Goldwin was wounded in the action and transferred through a snowstorm to the 6th Casualty Clearing Station. He died the next day, 18 January 1917, at age twenty-three years, ten months, and was buried nearby at Barlin Communal Cemetery, Pas de Calais.

News travelled quickly to grieving parents during the war years as technologies like the telegraph and telephone outraced letters and dispatches. Goldwin’s father received a cable about his son’s death on 22 January and telephoned the family’s friends. The Macdonalds went to see the Lapps immediately. Because Effie and George were special friends, Montgomery was deeply grieved. Margaret Mustard remembered that “the Macdonalds proved their friendship by claiming each sorrow as their own.”27 Montgomery helped prepare the sanctuary for the memorial service two weeks later. The church was filled with broken-hearted families on Sunday evening, 11 February, in spite of extremely cold weather. As Waterston writes in the previous chapter, Montgomery’s “sombre response” to this young man’s death in her journal on 22 January reflects the effects of this loss on the small community: “It seems to me that the very soul of the universe must ache with anguish.”28

Effie died within two years of the end of the war, on 4 August 1920. Like most mothers, she seemed never to have recovered from her son’s death. At her funeral, Montgomery probably heard a family story being repeated among the Leaskdale neighbours: one winter morning, the Lapps’ dog could be heard howling and howling, a bad omen, Effie told her granddaughters.29 It was the day they received the notice about Goldie’s death. At the same time that stories about Effie were being remembered, Montgomery was working on the last half of Rilla of Ingleside and writing perhaps one of the most poignant scenes in any of her books, a scene about another grieving dog, the Blythe’s Dog Monday foretelling the death of Anne and Gilbert’s son Walter in France: “Whose dirge was he howling – to whose spirit was he sending that anguished greeting and farewell?”30

Montgomery shared the loyalty of little Dog Monday on 21 November 1921 when she spoke at Jarvis Collegiate in Toronto. Rilla of Ingleside had been published a few months earlier, in August, and she chose to introduce the students to her new work. In a loud, clear voice she read the chapter about Dog Monday’s refusal to leave the railway station where he had been waiting since his master, Jem, left for service overseas. When she came to the part where Dog Monday recognized the tired soldier getting off the train, she tried to describe the joyful reunion between Jem and his dog, but something happened. Her voice broke, and she could not speak. There was complete silence. It seemed like forever until she spoke again. Everyone in the audience had goose bumps, and it was something that no one in the auditorium ever forgot.31

This very rare public display of emotion is tied to one of Montgomery’s deepest personal losses. When she spoke at this school, she was thinking of her dearest friend, Frede, to whom she dedicated this new book. Frede, a victim of the postwar flu pandemic, died two weeks after Montgomery finished writing Rainbow Valley. Before her speech to the students, she had shared lunch with one of Frede’s colleagues, and they had talked about their mutual friend, a pivotal incident in Montgomery’s journal, discussed in greater detail by Lesley Clement in chapter 13.32 Frede’s absence was painfully fresh as she read about Dog Monday’s happy reunion, something she would never experience for herself.

In the dedication of Rilla of Ingleside, Montgomery honours the memory of her cousin and best friend. She had already dedicated The Story Girl to Frede because of their nine-year friendship during their Prince Edward Island years. Rilla’s dedication commemorates their years together in Ontario. Frede had known Ewan since 1904 when they both boarded in Stanley Bridge, six miles from Cavendish, where Montgomery lived. Frede may even have facilitated the courtship between the two; when Montgomery faltered in 1910 during her long engagement, Frede encouraged her cousin to follow through with the marriage that would bring her to Ontario. With Montgomery’s financial support, Frede left her teaching position on the Island to attend Macdonald College in Montreal. After graduation, she was employed there as superintendent of Women’s Institutes for Quebec. Although her residence was not in Ontario, Leaskdale became a home to her almost as soon as the Macdonalds moved into the manse. She stayed with them for Christmas in 1911 and afterward for many weeks between terms and assignments. Frede became acquainted with Ewan’s congregations alongside her cousin. She lived with the Macdonald family for five months in 1912 when their first son, Chester, was born and thus felt a special bond with him. This lengthy stay established her place as a member of the Macdonald family. She eased into the Leaskdale community because she was a long-time, trusted friend to both the minister and his wife. When Ewan made frequent congregational visits or attended out-of-town conferences, Montgomery was not lonely. Because the two cousins complemented one another, Leaskdale manse became the home that Montgomery always hoped to have. Her newfound contentment was due, in large part, to Frede’s presence. When she was there, the Leaskdale neighbours heard the sounds of music and laughter from the manse. Everyone in the village knew her and was fond of her.33 The tiny room at the top of the stairs was Frede’s room; the Macdonalds’ home was her home too.

2.3 Montgomery, Frede, Ewan, and Chester in the Leaskdale dining room

Montgomery always viewed Frede and herself as allies against adversity as both worked to find personal happiness and professional fulfilment. They leaned on one another when their lives felt hard. While Ewan always seemed to be much older than he was, Frede preserved Montgomery’s youth. Together they reached back in time through shared memories. They both recognized how the Montgomery and Macneill personalities intersected, not always harmoniously, in themselves; they admired each other’s wit, intellect, work ethic, and sacrifice. In the war years, the strands of their lives were bound even more tightly because Frede was the only person to whom Montgomery could express her deeply experienced feelings about the terrible news she faced each day; Ewan would not talk about it. As several chapters discuss, particularly chapters 4 (Laura Robinson) and 13 (Lesley Clement), they knew that their complete loyalty to and trust in each other meant they could be their true selves and confess feelings they could never express anywhere else.

2.4 Frede’s room, Leaskdale manse

When Frede’s mother, Annie Campbell, returned to Prince Edward Island in October 1918 after her visit to Leaskdale, her son, George, became ill with influenza, and so did Montgomery. She recovered; George did not. His four-year-old son, Georgie, died too. Frede went home to help her family, with Montgomery joining her a few days later. They were together at the Campbell farm in Park Corner when the Armistice was signed on 11 November 1918. Montgomery returned to Ontario to finish Rainbow Valley, and Frede stayed on the Island through Christmas.

On 20 January, in Boston wrapping up her lawsuit against publisher L.C. Page, Montgomery received a wire from Frede indicating she was ill. The next night, Tuesday, she received an urgent phone call from Frede’s colleague telling her to come to Montreal at once. Arriving on Thursday morning, not knowing if Frede was still alive, she went to her hospital room. Frede was conscious and had the strength to laugh. When the end was near, Montgomery asked Frede to remember an old promise they had made each other – that if one of them died, the other would come back to the survivor, “to cross the gulf.” As she held Frede’s hand, they agreed that they would never say goodbye to each other, and they never did. Montgomery ordered red roses – Frede’s favourite – for the casket and accompanied it to the crematory where she watched the doors close between her and her former life.

Frede’s death shattered Montgomery as well as her husband. Ewan suffered a double loss: he lost a friend, someone who had enlivened his family; and he lost the wife who had a capacity for resiliency that only Frede could fully replenish. It made him more vulnerable to his own fears and weaknesses. In addition, Montgomery lost someone who cared about her oldest son, Chester. Would his life have taken a different shape with Frede’s interest and guidance?

Elizabeth Epperly describes Montgomery’s fiction with the word “magic” and her journals with “lament.”34 Those two words, “magic” and “lament,” also reflect the dual purposes of Montgomery’s emotional outpourings in her journal about the person who understood her best. In her magical reminiscences of Frede, Montgomery resurrects the perfect friend, a partner in an enchantment of laughter and restoration. Her commemorative journaling about Frede is an enduring lament of her loss. Aside from her journal, Montgomery reached out to find other ways to keep a tangible connection to Frede in the months following her death. Frede’s husband was Lieutenant Nathaniel Cameron McFarlane (recorded as MacFarlane by Montgomery). Frede and Cam were married in Quebec on 16 May 1917, at the beginning of his six-day leave from the New Brunswick Kilties (the 236th O.S. Battalion, CEF, known as the “MacLean Highlanders,” was stationed in his hometown, Fredericton). He also served with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry before and after his assignment with the Kilties. A chemistry teacher at Macdonald College, he met Frede when they both were hired as a result of the Agricultural Instruction Act in 1913. Montgomery was stunned and hurt when Frede wrote to her about the surprise marriage a week later. The Macdonalds had always expected they would plan and host a wedding for Frede in the Leaskdale manse. Moreover, Montgomery feared that Frede and her husband might relocate far away from Leaskdale after the war. After Frede’s death, Montgomery wished to know Cam better; she and Ewan had met him briefly in late October 1917, before he went overseas, but there was no real spark in the meeting. She summoned him to Leaskdale in April 1919 as soon as he left the service, anticipating that they would share their mutual grief with a circle of Frede’s Leaskdale friends. But the visit was a disaster. Montgomery was appalled by his immature behaviour, especially because he seemed untouched by his loss. She took him to visit the Oxtoby sisters, to whom Frede had always shown a special kindness. He made tasteless, insulting jokes about his late wife and about the Oxtobys, which bewildered the elderly hosts and humiliated Montgomery. She put Cam McFarlane out of her life.35

Instead, she kept “the Good Fairy,” a bronze statue, a wedding gift from friends at Macdonald College, which was one of Frede’s favourite possessions. It became a prominent fixture in the Leaskdale manse and Montgomery’s later homes in Norval and Toronto as an artifact to memorialize her lost friend. As photographs that Montgomery took reveal, she rearranged the tables, books, and plant stands along the walls in the parlour where she wrote her manuscripts to set up a focal point between the tall windows: Gog and Magog, her china dogs from England, sat on the floor beside a bookcase upon which she placed the Good Fairy. Above it on the wall was a wedding portrait of Frede holding a flower. Every day as Montgomery looked out toward the western light toward the spot that, in the previous chapter, Waterston calls a “haven from a grown-up world,”36 she would see the Good Fairy standing on the top of the world, the wind blowing in her hair, gazing up with her arms outstretched in an arc that lifted the author’s eyes upward to Frede. She never required a reminder of her lost friend, but she did need something on which to fix her vision, something beautiful that belonged to Frede. Through the enshrined Good Fairy, her friend was always there with her at the manse in the quiet hours while she sought inspiration and crafted her stories. The Good Fairy was an image that insisted on hope and optimism, even when Montgomery had neither.

2.5 Cameron MacFarlane

2.6 Good Fairy, Leaskdale manse

Montgomery’s early years in Leaskdale were rich in joy and sorrow. Here she lived some of her happiest times as a wife and mother, even during the war. She had a healthy husband and an intact young and loving family; the support of her beloved companion, Frede; and a village that appreciated and admired her. She placed a reminder of these poignant times in the first pages of Rainbow Valley and Rilla of Ingleside. The war and grief would bind her forever to many kind families in Ontario. She would never forget the effects that the war had on her community, or her friends’ sorrows at the loss of their grown children in the Great War, or the wooded haunts of those children who inspired the environs of Rainbow Valley. When the time came for her to leave Leaskdale, she wrote about the view beyond the windows beside the Good Fairy: “The beautiful woods behind Mr Leask’s, the leaf-hung corner of the side road, the lovely hill field beyond with the elms on its crest. I love these things and grieve to leave them.”37 But more than that, it was the memory-filled home that summoned her deepest grief.

Montgomery was uniquely bound to her first Ontario home because, for a time, it was occupied by a family in the wholeness of their lives. To paraphrase a poem about the Good Fairy, the windows were lit with a buoyant light of hope, and the companionship within its walls provided the whispering voice of courage; it echoed of love.38 The Leaskdale manse was, and would be forever, the only house inhabited by her little boys, Chester and Stuart, untouched by their futures. It would be the only place shared with a cheerful husband who still had a dimpled smile and roguish eyes unclouded by fear, confusion, and doubt. It would be the only home infused with the brilliance of her vibrant companion, Frede, and the only haven filled with her own potential for happiness and the life story she might have lived.