I do like Toronto. I almost think I would like to live there. I have always said and believed that I could never wish to live anywhere save in the country. But I now begin to suspect that what I meant by “country” was really “Cavendish.” I would rather live in Cavendish than anywhere else in the world. But apart from it, I really believe I would like very much to live in a place like Toronto – where I could have some intellectual companionship, have access to good music, drama and art, and some little real social life.

~ L.M. Montgomery, Selected Journals, 1 November 1913

When L.M. Montgomery left Cavendish to establish her new home in Ontario, she left behind a community stamped indelibly with her trademark – just how indelibly she had yet to understand. Cavendish and indeed the entire province of Prince Edward Island were just beginning to negotiate how to adopt the orphan Anne without being engulfed by her red-headed presence. Throughout the preceding chapters, we have seen various Ontario communities, large and small, domestic and public, secular and religious, imaginary and real, in which and through which Montgomery sought home. For Ontario to become her new home, and not just a place to live, it would have to provide opportunities for social, intellectual, and cultural companionship while respecting her privacy and granting solitude for reflection and creation. This chapter examines a perhaps irremediable tension that steered her quest for a community, a quest that frequently attracted her to Toronto, “tonic” for a “sagged” soul, as she writes in 1919.1 Because of her celebrity status whereby she was constantly “lionized” – which Montgomery concedes was “not a disagreeable sensation”2 – and because of the sense of speciousness that this lionization engendered in her, this tension was never resolved.

Passing through Toronto during his Canadian tour of 1907, Rudyard Kipling tagged Toronto as “consumingly commercial.”3 In The Municipality of Toronto: A History (1923), J. Edgar Middleton attributes this commercialism to American influences, seeing in Toronto’s “outward semblance . . . an American city . . . with plays and films from the United States . . . exactly such as one may see in Detroit or in Chicago.” Despite this façade, Middleton continues, struggling as so many others to define his country’s distinctive properties, Toronto is a “Canadian” city, “British in the North American manner . . . perfectly equipped to interpret Great Britain to the United States, and the United States to Great Britain.”4 Published the year before Middleton’s history, Katherine Hale’s chapter “Toronto – A Place of Meeting” in her Canadian Cities of Romance leaves the American and British elements out of the mix to focus on indigenous and immigrant groupings and regroupings until the original settlements in the Valley of the Humber grew into a metropolis, “humming on its commercial way,” with “crowds on the pavements, crowds in the trolleys, crowds in the shops.” Hale rhapsodizes about the surprises that Toronto conceals, mentioning The Grange (the Art Gallery of Toronto) and the Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology,5 opened to the public in 1913 and 1914, respectively.

Into this maelstrom of commercialism and evolving culture, Montgomery journeyed to meet with her publishers and to do the family’s shopping for items unavailable in the smaller centres of Leaskdale or Uxbridge and, later, Norval. Increasingly, as her residence in Ontario became more publicized, she was invited to Toronto to give recitations and speeches or to be the guest of honour at an organization’s or friend’s social function. Her hosts often entertained her with excursions to the theatre. Business and domestic obligations and opportunities for “some intellectual companionship” and “some little real social life”6 were often accomplished in a whirlwind trip of several days. Although Montgomery regarded these excursions as respite from the familial and pastoral duties of Leaskdale or Norval, she herself became a product of the cultural industry in which she participated. In Literary Celebrity in Canada, Lorraine York begins with the question, “Are authors of literary works, then, no more than consumable trademarks once they enter the culture of celebrity?” Through an examination of Montgomery’s awareness of and attempt to manipulate and control factors such as media scrutiny and the potential value of artifacts and places associated with her name, York argues that the author was “canny and clear-eyed about her fame” and “knew what it was to negotiate the public and the private in the face of wide publicity.”7 Quoting from a letter that Montgomery wrote to G.B. MacMillan in 1909 about the fabrication of biographical details in a false interview and conflation of the public and private spheres (“I don’t care what they say about my book – it is public property – but I wish they would leave my ego alone”8), York situates Montgomery’s “simple, pragmatic division between the public product, the writing, and the private entity, the writer” within “the celebrity culture that was taking shape in North America during the years she experienced her success,” a culture that “militated against any such easy division.”9

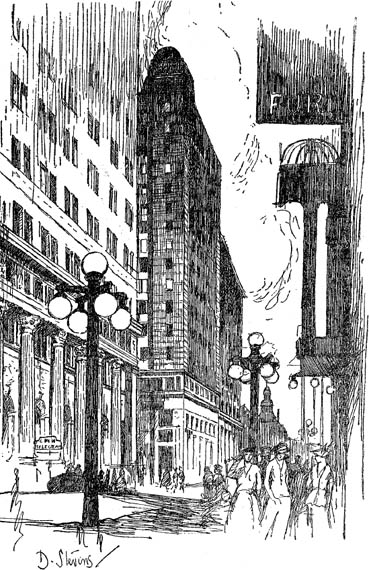

13.1 Dorothy Stevens, “The Whirlpool of King and Yonge”

This penultimate chapter of L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys examines a final valley through which Montgomery journeyed. As she travelled to and from and finally took up permanent residence in the Valley of the Humber, Montgomery became more and more cognisant of the damage – and her powerlessness to stay the damage – that subsisting as a consumer product had inflicted on her “ego” (the conscious self that translates the external world, including one’s public personae, to the private inner self) and her “soul” (the animating core of one’s being that provides the will to persist). This is not to suggest that she was “the innocent small-town Canadian literary star described by Clarence Karr,” a perception that York challenges, but rather that, even though “Montgomery was unusually articulate about and aware of the conditions and ironies of her celebrity,” her Ontario years and her connections with Toronto’s cultural scene generate a further irony. York observes generally that celebrity “signals the meeting and exchange of the public and private realms, and such a condition is itself productive of uneasiness,” which she identifies as “one of the conditions most prevalent among the literary celebrities” whom she examines in her study.10 But, as Montgomery says to MacMillan, the “fake” interview produced more than “uneasiness”; it “jarred on [her] horribly.”11 The jarring of “overlapping, competing spheres of cultural production” – “the very essence of . . . literary celebrity,” as York maintains12 – ultimately wore down her ego. Her pursuit of tonic for her sagged soul in the cultural products of Toronto – of which she was one – reveals itself to be a toxic illusion. The cultural products to which she was drawn – primarily elocutionary and theatrical performances, later supplanted by the cinema – reflect and profile Montgomery’s growing consciousness of herself as a consumer product in an illusionary and ultimately insubstantial world of literary fame.

In Cavendish, Montgomery had already experienced being a celebrity when Governor General Earl Grey personally requested a meeting with the author of Anne of Green Gables on his visit to the Island in September 1910, a request that Montgomery found somewhat “unwelcome.”13 Several months later, after a similar vein of resistance from her, she was convinced by her publisher, L.C. Page, to visit Boston. Montgomery states: “Hitherto my literary success has brought me some money, some pleasant letters and an increase of worries and secret mortifications. I had experienced only the seamy side of fame. But now I was to see the other side.” Overcoming her feelings of insignificance and fear that she was being mocked, she found herself “besieged with invitations” in Boston and discovered a “certain requirement of [her] nature, which has been starved for years,” including “gay, witty companionship and conversation . . . necessary for [her] normal well-being.” But her lengthy descriptions of her Boston lionization also capture the tedious demands on a public figure, and she apostrophizes facetiously, “Anne, Anne, you little red-headed monkey, you are responsible for much!”14 Thus, from the time that Anne of Green Gables became an immediate best-seller in the summer of 1908, Montgomery experienced conflicting responses to her success, exacerbated, Mary Rubio concludes, by her “fragile temperament [that] found sudden fame disorienting.”15

Because Montgomery lacked a long-standing supportive community of friends and family, her residence in Ontario intensified the disorientation generated by her fame. The Reverend Ewan Macdonald, as Rubio observes, would soon “sense that his powerhouse of a wife was hoping he would do well as a minister so that they could eventually move to a bigger community . . . ideally in Toronto, where her book life was” but where he “would have been totally out of his milieu.”16 Meanwhile, Montgomery was carving out a separate life for herself in what she felt to be a more compatible and stimulating environment than the Leaskdale parish. While she was still in Cavendish, two Toronto journalists, Florence Livesay and Marjory MacMurchy, “had sought her out.” She would occasionally cross paths with Livesay again; the “well-connected” MacMurchy welcomed the newly wedded couple to Ontario with lunch in Toronto as they were en route to Leaskdale.17

Montgomery was barely settled into the Leaskdale manse when she went to Toronto on 5 December 1911, at Marjory MacMurchy’s invitation and as her house guest, for a reception that the Canadian Women’s Press Club hosted for her and “Marian Keith,” the pen name of Mary Esther Miller MacGregor from Galt, who also had recently married a Presbyterian minister. The reception the next day at the King Edward Hotel was, Montgomery writes, “pronounced by all a great success. In reality it was the wearisome, unsatisfying farce all such receptions are and, in their very nature, must be.”18 With MacMurchy and the president of Toronto’s Women’s Press Club, Jane Wells Fraser, Montgomery also attended the theatre, which in one form or another would become a favourite cultural pastime for her. The Charles Frohman production they attended at the Princess, A Single Man by British playwright Hubert Henry Davies, starring American stage actor John Barrymore, was typical of the frivolous British comedies staged and toured by large American syndicates in Toronto theatres. As B.K. Sandwell asserts in his oft-quoted “The Annexation of our Stage” (1911), “Canada is the only nation in the world whose stage is entirely controlled by aliens.” He denounces the commercial ambitions of Broadway producers such as Frohman, whose control over what is produced, in Sandwell’s view, has hindered the growth of Canadian theatre and drama. His suggestion that Canadian audiences, when given the opportunity, prefer performances of “the best English standard”19 aligns with Montgomery’s assessment of A Single Man as “a silly backboneless affair.” She was obviously seeking something more substantial to sustain her than frivolous comedies and vacuous receptions. She was therefore “heartily glad to get back home” to Leaskdale: “Some outings I like. But they are such as I plan myself and are not of the conventional kind at all.”20 She optimistically clung to the notion that she had some control over the cultural products she consumed.

Over the next three years, Montgomery records in her journal attending only two other plays in Toronto, including a “silly and superficial” musical comedy she saw with “the MacMurchy girls” in the last week of October 1913. During this visit, she herself became the entertainment when she delivered her first public speech – as opposed to a prepared recitation or reading – and she admits to being for many months “in a blue funk at the idea.” Her speech on her home province captivated her audience of eight hundred members of the Women’s Canadian Club and received praise from those in the audience and the local press. Montgomery cites several of these newspapers in her journal, selecting passages that compliment her clear articulation despite her lack of elocutionary training; another describes her stature, eyes, hair, and complexion; and another finds her “a varitalented woman who did not quite all go between the covers of ‘Anne of Green Gables.’” This strange image of a woman not fully wedged inside or confined by her own literary creation prompts Montgomery to respond that “I have no intention however of rushing into a career of platform speaking.”21 Although certainly not a full-time career, putting herself on public display would become the norm throughout the next two decades. Rubio writes that with the success of this event Montgomery “embarked on a new career as a riveting platform speaker.”22 The numerous journal entries focusing on the readings, speeches, and stories she delivered are generally accompanied by accounts of the enthusiastically favourable responses of the audience and media to her content and performance. These two days that she spent in Toronto were a time of “no cares, no worries. I didn’t have to watch over everything I said, lest it might be reported to my own or my husband’s discredit.” All these factors contribute to her declaration quoted in this chapter’s epigraph: “I do like Toronto. I almost think I would like to live there.”23

Because of her celebrity status, however, Montgomery had to heed not only what she said in the parishioners’ presence but also, although eighty-five kilometres away, what she did and where she went in Toronto. Her giving a speech on her home province would not offend even the most orthodox Presbyterian or Methodist, but theatre was an entirely different kind of cultural product. When she attended the theatrical hit of the 1914 spring season, J. Hartley Manners’s Peg o’ My Heart at the Royal Alexandra, the society page of the Globe reported that “Mrs Ewan Macdonald, who has been staying with Mrs Norman [Mary] Beal, Hilton avenue, returns to her home in Leaskdale today. The authoress, who has been enjoying the theatre, says she sees all sorts of resemblances to ‘Anne of Green Gables’ in winsome ‘Peg o’ My Heart.’”24 Robertson Davies conjectures that plays like Peg o’ My Heart “struck a note that was resonantly and entirely of its time. It offered on the stage not what was observable fact, but a dream of what the audiences wished were true, spiced with enough contemporary fun to give it a spurious air of reality.”25 Montgomery’s enjoyment of “one of the most charming little comedies I’ve ever seen” – despite or perhaps because of its “spurious air of reality” – was tainted by the Globe’s reporting her presence at the play: “All ‘the parish’ will see it and what will the Zephyrites think!! Verily, that I am a brand, not yet plucked from the burning!” This seems an early example from the Ontario years of Montgomery’s fabrication or skewing of details for the kinds of self-dramatization discussed more fully later in this chapter. Although she claims that it was “some wretched newspaper reporter” who saw her and inserted this report,26 its appearance in a society column that depended on submitted material and inclusion of a quotation from Montgomery and information about her hostess suggest that the notice was more likely provided by Mary Beal, an Uxbridge (Hypatia Club) friend, now living in Toronto, whom Montgomery met soon after arriving in Leaskdale. This suspicion is reinforced by the other newspaper clippings from society columns preserved in the Black and Red Scrapbooks housed at the University of Guelph Library’s Archival and Special Collections that describe teas hosted by Mary. “My soul loathes afternoon teas,” Montgomery exclaims after yet another of Mary’s teas. “And this is in the year of grace 1919! How long does it take a world to learn how to live?”27 These rounds of vacuous social events are reflected in Montgomery’s creation of Robin Stuart, Jane’s mother in Jane of Lantern Hill, whose finery – clothes and jewellery selected by Jane’s detestable Grandmother Kennedy – cannot camouflage the young Toronto socialite’s unhappiness and consequent growing thinness. By the time that Montgomery began writing this novel in 1936, her experiences with Toronto’s cultural scene had been displaced by participation in its social scene. Jane’s mother is depicted as a bird in a cage from which she envisions no escape, caught in a round of dances, parties, and afternoon teas where the women come and go speaking of old Mrs Kennedy as “an utterly sweet silver-haired thing, just like a Whistler mother.”28

Montgomery’s concern over what the “Zephyrites” might think was well warranted. For several years, the topic of theatre censorship had been entertaining readers of Toronto newspapers, especially the Globe, then edited by the ordained Presbyterian minister J.A. Macdonald, with front-page coverage of and outraged editorials over the theatrical legal battles of “the man in the green goggles.” A Methodist minister, John Coburn, disguised with green goggles and false whiskers, had assumed for himself the role of official theatre censor, attending performances he thought required his vigilance and then waging legal battles throughout 1912 and 1913 against productions he deemed profane. These legal battles ensured that the city’s appellation “Toronto the Good” was carried well into the twentieth century – albeit in absurd fashion. Even after a court ruling on 7 June 1913 that “restricted the church again to its traditional role of pulpit-critic, not legal guardian, of drama in Toronto,”29 and even after the Methodist Church relaxed its strictures in 1914 on church members attending theatre,30 theatre remained the target of official and unofficial censorship. The “tyranny of organized virtue,” as Robertson Davies describes both the religious and secular restrictions on anything suspected of being “irreverent,” held sway well after the Second World War over those fearful for their own and others’ souls.31 With any tyrannical regime, scrutiny of those who are publicly visible, as Montgomery was throughout her years in Ontario, is paramount.

When Hart House Theatre opened in 1919, Toronto audiences were finally exposed to serious drama, although certainly not less contentious theatre, much of it written and produced by Canadians. On Saturday evening, 19 November 1921, Montgomery records that, with Mary and Norman Beal, she attended “a couple of plays” at Hart House mounted by the Community Players of Montreal: “Good amateur acting is always enjoyable, all the more so from the absence of stage mannerisms and too-great skill. There is more reality about it.”32 In their introduction to Later Stages: Essays in Ontario Theatre from the First World War to the 1970s, editors Ann Saddlemyer and Richard Plant remind us that “for many people in the 1920s, ‘professional’ was synonymous with corrupt commercialism and the foreign domination, particularly American economic control, of our theatre.”33 Montgomery’s response to the plays’ “reality” came after an afternoon spent at a talk given by Basil King, another lionized Island novelist (who had, however, been living outside Canada, mostly in Boston, for more than two decades). King’s talk in the Robert Simpson’s auditorium was followed by a “big reception given by the Press Club to the Authors’ Association,” where a meeting with a friend of Frede brought Montgomery to tears: “There in that swarming mob . . . I felt like a maggot in a swarm of inane maggots – at least they seemed inane in that personality smothering mass – coming and going and repeating endlessly, ‘I love your books’ – ‘Was “Anne” a real girl?’ – etc. etc.”34 Montgomery captures the spuriousness of her situation in this atypical (for her) image of the parasitic relationship between lionizers and lionized. York notes the aversion she experienced to this parasitism when she visited Cavendish in 1929: “Hot dogs and tea rooms: these were, in Montgomery’s eyes, horrors of commodification, displaced objects of consumption for what was really up for sale: Montgomery herself.”35 By the early 1920s, she already sensed just how devouring these commercial relationships could be on body and soul of consumer and consumed alike.

Although Montgomery does not identify the plays she attended that Saturday evening at Hart House and whose realistic production she appreciated, advertisements and reviews confirm that they were Marjorie Pickthall’s The Wood-Carver’s Wife and George Calderon’s The Little Stone House. Augustus Bridle’s detailed laudatory review for the Toronto Daily Star the following Monday focuses primarily on Pickthall’s play, which, one of his several headlines declares, is a “Canadian Play: Poetic Tragedy without Stagecraft.” He notes the “tension” the audience experienced as a result of Pickthall’s intense, powerful language. Although he asserts that the play “is much too detached from common human experience” to make a major contribution to Canadian drama, Rupert Caplan’s “integrity of delineation” of the wood-carver compensated for the play’s having “almost no more action than in a tableau just come to life.” Bridle then conjectures why the audience “began to laugh at [Calderon’s] sombre Russian play” when “there is as much comedy in The Little Stone House as in the average epitaph. But the audience wanted something human after the tense atmosphere of the Woodcarver, and the Russian play has it . . . This is tragedy that lurks on the edge of humor, and is therefore the kind that stimulates and entertains.” Pickthall’s play is about a woman’s discovering the complicated facets of herself as wife and model for her husband’s craft; Calderon’s play is about a mother’s “refus[ing] to give up her sacrificial idea of a dead son whose memory she worshipped in order to reclaim her living son in the starving convict.”36 These plays in tandem seem to have provoked in Montgomery a personal response to loss, memory, and the illusory position of the artist, which then prompted the uncharacteristic image of herself in a symbiotic, parasitical relationship with her admirers.

The twelve days between 18 and 29 November 1921 that Montgomery spent in Toronto exemplify the extent to which she was becoming the consumed, herself the cultural product, not just the consumer, and her sense of the toxicity to her sagged soul. The first Tuesday was a “full day – full of something at least,” she writes enigmatically. In the morning, she gave a reading and brief talk followed by “writing a hundred autographs” at Moulton College; she then shopped, lunched, and took in a movie (Quo Vadis) with Mary Beal; later in the afternoon, she gave “readings in the auditorium of the Simpson store” to “a bumper audience. The room was packed and half as many more couldn’t get in . . . After it came the usual autographing and handshaking.” She kept up this pace through the entire week and into the following: an audience of eight hundred girls at Jarvis Street Collegiate; “some charming women and some very foolish ones” at an IODE meeting in Parkdale; thirteen hundred boys and girls at Oakwood; fifteen hundred high-school girls at the School of Commerce (“everything seemed vanity and schoolgirls the vainest of all”); one of Mary’s “At Home[s] . . . the usual thing”; autographing books in Hamilton; a luncheon hosted by her publishers at the National Club; readings at Sherbourne House “to a mob of school teachers who may have been very nice individually but were bores en masse”; six hundred Sunday School pupils at Dunn Avenue Methodist Church; a Business Women’s Club luncheon, where she was a guest along with Emmeline Pankhurst, followed by “the Press Club reception of Lady Byng” – and then home that evening to her “darling boys again.” Between the trip to Hamilton and the luncheon at the National Club, Montgomery admits to being “so drugged by the rapid succession of the crowded days that I haven’t really thought of home at all. But now the effects of the drug have worn off and last night my hunger for Stuart and Chester seemed absolutely physical in its intensity.”37 Celebrity has failed to sate the appetite for meaningful human interaction.

Whereas the Hart House plays give her a sense of the “tragedy that lurks on the edge of humor,” the other theatrical event Montgomery attended, again with the Beals, provides her with undiluted mirth. This was the vaudeville production Biff-Bing-Bang of the touring Dumbells, a troupe of demobbed Canadian soldiers, which she finds “incredibly funny and well done, and I laughed as I haven’t laughed for years.” She particularly admires the “stunning beauties” among this troupe of female impersonators: “The ladies of Biff-Bing-Bang were wonderful creations, with their snowy shoulders, jewelled breasts and rose bloom cheeks. The only thing that gave them away was their thick ankles!”38 Montgomery responds to the carefree gaiety of this entertainment, and her description, couched in humorous terms, also conveys her keen visual sense that leads to her scrutinizing of shoulders, breasts, cheeks, and even ankles. The “man in the green goggles” would not have been amused.

Although Montgomery had no aspirations as a thespian, elocution was an avocation that attracted her and would not have outraged any orthodox parishioners in Ewan’s two-point callings of Leaskdale/Zephyr or Norval/Glen Williams. Many women in her novels pursue elocution as either a pastime or a career – from Anne Shirley through Sara Stanley to Ilse Burnley. Unlike her undiluted mirth over the female impersonators of Biff-Bing-Bang, however, Montgomery’s responses to actual women displaying themselves publicly are complex, reflecting the rapid changes and ambivalent and often conflicting attitudes of the early decades of the twentieth century. The twelve days of intense lionization discussed above began with an event that, had Montgomery known the full story, would perhaps have tempered her portrayal of the guest of honour. She records that, on 18 November, she and Mary Beal attended a Canadian Authors Association dinner honouring Nellie Mc-Clung at St George’s Hall, home to the Arts and Letters Club. Although Montgomery was not the guest of honour, she sat at the head table. She writes: “Nellie is a handsome woman in a stunning dress, glib of tongue. She made a speech full of obvious platitudes and amusing little stories which made everyone laugh and deluded us into thinking it was quite a fine thing – until we began to think it over.”39 Another person who gives an account of this evening, someone who did have time to think it over, would have disagreed: M.O. Hammond, a charter member of the Arts and Letters Club (of whom Sandra Gwyn writes, “the earth had seldom produced a more honourable and upright character”40) describes McClung in his diary on this occasion as “happy, breezy, bright” with “plenty of stories from real life, good humor and philosophy.”41

Hammond also records the sequel to this evening in an entry for 26 November that narrates a “rare night at Arts and Letters monthly dinner” featuring “a debate in burlesque” on a resolution to abolish the Canadian Authors Association and about women as authors.42 In her history of the club, Margaret McBurney summarizes Hammond’s diary entry: “In the midst of the debate there was a noisy interruption from the gallery, where Doug Hallam, in drag, was impersonating McClung and attempting to hang a banner over the railing. A ‘sergeant-at-arms’ rushed up to arrest ‘her.’ He brought ‘her’ downstairs, and forced ‘her’ to take a drink.”43 A testament to this event is a sketch by Arthur Lismer of Hallam impersonating the abstemious McClung and a long poem commemorating the event, both of which are in the Arts and Letters Club file at the Thomas Fisher Library.44 Although Montgomery would have had no knowledge of these specific misogynist antics, Augustus Bridle, the founder of the Arts and Letters Club, was notorious for his outspoken exclusionary views on women,45 views that represent “the mediaeval mind” – such as Montgomery attributes to Ewan several months later – that relegated women to a place outside the citadel walls of the baronial St George’s Hall. Montgomery contrasts Nellie McClung’s speech to Basil King’s, “full of good ideas, with no superfluities or frills or gallery plays.”46 As an aspiring public speaker, Montgomery clearly has bought into the myth with which York concludes her study: “Canadians, and Canadian women in particular, are more modest about their fame, less affected by it . . . and, therefore, more authentic and unspoiled as celebrities. As the growing body of theoretical work on celebrity has amply maintained, however, this claim of authenticity holds both powerful and unstable cultural currency.”47 While the men at the Arts and Letters Club force “Nellie Mc-Clung” to imbibe, Montgomery’s pen skewers a woman she deems an inauthentic woman flaunting the celebrated status bestowed on her. Montgomery’s own approach is much more humble and self-effacing: “If I had had the proper training in early life I think I could have made a fairly good speaker. But it is too late now and I don’t want to bother with it anyway. I have one work to do and have no time to take up another. Besides, the country is lousy with amateur speakers.”48

When Montgomery attends Margot Asquith’s lecture at Massey Hall a few months later on 27 February 1922, her response is yet more complex: “She was not worth listening to and I had not expected she would be but I was extremely anxious to see her, after reading that amazing biography of hers. She was not worth looking at either. I never saw so witch-like a profile; and she was so flat you couldn’t have told her front from her back if she had been headless. Nevertheless, she was – Margot Asquith! She is a personality. You may hate – despise – deride – but you cannot ignore her.”49 Despite Asquith’s androgynous appearance that obviously repels her, this grand orator provides Montgomery with an opportunity to learn how to talk “Little Things” without, as Asquith does, betraying the “Intimacies of Great Folk” (the Globe’s headlines for the article covering this event). The Globe reports that early in Asquith’s speech, “she remarked that she had been told to be careful of her words in Toronto, but, with a touch of her insurgent and flamboyant youth, Margot declared: ‘I cannot be careful of what I say, though,’ and received the applause of the audience.” The Globe’s reporter generally commends the orator’s choice of topics and magnetic delivery, the one exception being when she performed rather than delivered “her dissertation on prohibition . . . Margot illustrated with several anecdotes, which, although immensely amusing to the audience, were of an almost vulgar nature, in that each of them depicted an individual half stupid with drink.”50 Margot would have done well to remember that she was not only addressing a Toronto audience but also performing in Massey Hall, which had been built fewer than thirty years before, with “no proscenium or wings – the Hall was not a theatre, after all,” by Hart Massey, a staunch Methodist, who “disapproved of drink, tobacco, cards, theatre, dancing, and other forms of self-indulgence.”51

As a public speaker, Montgomery would need to adhere to topics more compatible with her own temperament and palatable to her audience – Prince Edward Island and its lore, her writing of Anne, her ascent of the Alpine Path, and advocacy for Canadian literature. Like the essays, letters, and interviews that Benjamin Lefebvre includes in the first volume of The L.M. Montgomery Reader, these public talks are “evidence of a more public Montgomery” and “complement and complicate the poetics of self-representation that scholars have traced in past published sources.”52 Rubio notes that, after readings that Montgomery gave to the Chatham branch of the Women’s Canadian Club in 1920, the confession of her insecurity and surprise over the thunderous reception she received is one of the few times, even in the privacy of her journal, that she reveals “some of the really ‘secret’ aspects of her inner life”: “Her life is truly a game of smoke and mirrors.”53 The journal entry Rubio refers to would have been written when Montgomery was reading Asquith’s An Autobiography as it is dated just two days before the long entry that Emily Woster discusses in chapter 8 in her exploration of the “autobiographical meaning” and “self-creation” of Montgomery’s reading. Montgomery “literally constructs herself in the journal,” Woster concludes.54 Asquith was a woman who had become a celebrity by airing secrets – hers and others’ – in public. Montgomery’s readings of both Asquith’s text and performance reveal the potential dangers of celebrity when not just the public personae (which York’s Literary Celebrity in Canada discusses) but the ego get caught up in “a game of smoke and mirrors,” especially when the rules of this game are dictated by a commercially controlled and often misogynist cultural environment. With the erosion of the ego’s filter, the public personae begin to collide with the soul, leaving the soul vulnerable.

Later in life Montgomery turned more and more to the movies as tonic for her sagged soul, as pure escape, although often faulting them for being a travesty of the book or history on which they were based and with which she was intimately familiar. Many of the new movie houses had taken over the old vaudeville theatres. Toronto architect Robert Fairfield writes that these theatres were “the commercial ambitions of a few syndicates in the United States and Canada that brought mass-produced entertainment to the twentieth-century urban market, packaging it with the kind of theatre buildings they thought would lure a mass audience through the turnstiles. The result was a commercially inspired make-believe theatre architecture, aimed at creating an atmosphere into which one could pleasurably escape from the grinding realities of everyday life. In the years to come deluxe movie houses and motion picture palaces were to move those make-believe creations into new realms of extravagantly romantic fantasy.”55 One of the most extravagant theatres was the Runnymede, at 2225 Bloor Street West, Montgomery’s neighbourhood theatre after her move in 1935 to “Journey’s End.”56 The Runnymede’s atmospheric style with a celestial ceiling earned it the reputation of being “Canada’s Theatre Beautiful.”57 During her Toronto residency, the final years of her life, Montgomery records visiting this (and other) movie houses several times a week for the kind of escapism that Fairchild describes. For example, on 25 June 1938, “I went alone to see Tom Sawyer. Enjoyed it and enjoyed my walk home afterwards. My worries and problems remain the same but I felt now that I can grapple with them and forget them by times. And I am able to escape into my ‘dream lives’ again and come back refreshed and stimulated.”58 Whereas she once wove these “dream lives” out of her imagination, often spurred by her active engagement with literature and history, they now need the stimulant of the screen to provide the desired tonicity. They are conducive to neither the kind of self-constructive autobiographical meaning that Woster discusses in chapter 8 nor the creative process whereby, Montgomery writes, “I am outside of [the story] – merely recording what I see others do. But in a dream life I am inside – I am living it, not recording it.”59 The darkened movie house made her invisible to public scrutiny, but it also inhibited fruitful self-scrutiny, its cultural product promoting the escape from any reality but that projected visually on the screen.

Unlike these movies, the few plays that Montgomery attended from the mid-1920s onwards – and one in particular – provided her with an opportunity to develop a clearer understanding of the toxicity of celebrity in a “consumingly commercial” cultural environment. Hart House Theatre was not the only effort to combat the commercialization of the dominant American syndicates; there had been a number of endeavours to develop antidotes to the Americanization of the Canadian stage, primarily touring British companies, which floundered during the First World War. From these various companies, one emerged after the war: “Maurice Colbourne’s London Company was unquestionably the strongest and most important influence in the province . . . Colbourne first came to Ontario in 1926 to help organize the English Repertory Theatre in Toronto and to champion Shavian drama as a bulwark against the crassly commercial American theatre . . . As a result, many audiences were given their first taste of ‘modern’ drama through productions that, in terms of the excellence of the acting and staging techniques, were uniformly well above those usually provided by the American touring system.”60 Montgomery attended a Colbourne production of John Bull’s Other Island at the Royal Alexandra Theatre in late February 1929 with the Barracloughs from Glen Williams, but she was more focused on describing her enjoyment of “the excursion in spite of [her] languor and headache” than the play itself: “Shaw’s play was quite good but not nearly so good as St Joan and the accent of the English cast made it difficult to follow the dialogue.”61

Montgomery had attended a remarkable production of Shaw’s Saint Joan nearly five years previously, on 9 October 1924, of which she declared, “never did I have such an evening of enjoyment.”62 Extensive media coverage was given to the premier of Shaw’s play on 28 December 1923 at New York’s Garrick Theatre, a Theatre Guild production starring Winifred Lenihan; the London staging with Sybil Thorndike, for whom Shaw had written the play, which began its run 26 March 1924; and the Theatre Guild’s touring production, which replaced Lenihan with Hamilton-born Julia Arthur, and successfully travelled throughout North America for two years after opening in Toronto at the New Princess Theatre on 6 October 1924. The stories of Shaw and Arthur, as aired in the press – like the story of Saint Joan herself, for whom church and various French and English factions are willing to negotiate “a king’s ransom” and who must be totally consumed to ensure there are no relics to incite an idolatrous following63 – address the “consumingly commercial” vagaries of lionization. Montgomery would certainly have been aware of the vicissitudes of Shaw’s status as an international celebrity, the deepest valley occurring during the First World War because of his controversial anti-war newspaper articles, published collectively as Common Sense about War (1914). Shaw ascended from this valley in the 1920s with the success of Saint Joan and consequent honour of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1925, which he initially declined but then accepted, although donating the money to the Anglo-Swedish Literary Foundation, a newly formed organization more in need of money than himself, he declared. The title of a long article by Lawrence Mason, drama critic for the Globe, sums up well the playwright’s return to public favour: “‘Saint Joan’: Why Has This Particular Masterpiece, among Shaw’s Many, Reconciled Thousands to Him after a Lifetime of Dislike?”64

From beginning to end, Julia Arthur’s story was fodder for magazines and newspapers, tabloid and mainstream. Most pertinent to Montgomery’s story is Arthur’s coming out of retirement in her mid-forties, fifteen years after her marriage to the fabulously wealthy Bostonian, Benjamin Pierce Cheney Jr, with The Eternal Magdalene, which played in both Hamilton and Toronto (March 1916) after a mixed reception in the United States where it was deemed by some too old-fashioned.65 In the role of Saint Joan, Arthur reached the pinnacle of her career at the age of fifty-five. The Toronto drama critic Hector Charlesworth contends that with Arthur “the play became a new thing, noble, moving, and at every moment appealing.”66 Her biographer, Denis Salter, describes the strengths that Arthur brought to the role: Joan’s “sturdy conviction formed the ruling passion of [Arthur’s] conception, while around it were seemingly myriad qualities – of courage, fire, resiliency, simplicity, and determination – which she brought so intensely and yet so naturally together that some audience members felt that both she and they had become pure disembodied spirit in an act of worship.” Through the “publicity interview” that Arthur gave Geraldine Steinmetz for Maclean’s magazine (January 1916) – in which Steinmetz suggests that “Canadians were excited because one of their artists . . . was now making a newsworthy come-back” – and the five-part serialization of her memoirs for Hearst’s magazine (March–July 1916), “an exciting legend was fashioned from her career,” carrying her through another decade of performance and lionization. Throughout the later years of her career, but especially while touring Saint Joan in Ontario, Arthur – like Montgomery – made the rounds as guest of honour and guest speaker at various service and cultural organizations. Canadians, Salter concludes, “shared vicariously in her success as an international star. ‘We all feel a sort of reflected glory about Miss Arthur’s fame,’ observed a member of the Women’s Canadian Club.”67

Montgomery’s own copy of Shaw’s Saint Joan (Constable, 1925) shows that it is a text, like those that Woster discusses, with which she communicated over a number of years. Montgomery inscribed her copy of Saint Joan with her name, the date 1925, and her signature cat icon; she marked passages with arrowheads and question marks; she inserted and pasted in performance photographs from periodical clippings and images of Shaw’s Dublin birthplace and magazine reproductions of George William Joy’s Jeanne d’Arc endormie (1895) and Jules Lenepveu’s Jeanne d’Arc au sacre de Charles VII (1874) – thus conflating the man, his product, and visual and dramatic representations of it between the covers of one book. The Black Scrapbook also preserves a noteworthy artifact, inserted almost a decade later, a letter to the editor addressing the debate over the relevance of the play’s Epilogue to Joan’s “second martyrdom”: “Here is the real tragedy of Joan, and of Mankind. Our saints, like our Christs, must be kept on pedestals and in stain-glass windows, to be worshipped but not to be met with.”68 Literary celebrities such as Shaw and Montgomery experienced a similarly tragic fate as that of Joan: an isolating lionization.

In previous chapters, William Thompson and Emily Woster discuss Montgomery’s journals as self-constructions, but her journal descriptions of attending the production of Saint Joan and several interactive readings of the play move beyond self-fashioning to self-dramatization. Montgomery inserts herself into this narrative as if she were living a tragic play of the misunderstood and isolated lone lion. In Writing a Life, a companion to the journals, Rubio and Waterston begin with the observation that Montgomery “was fettered by her own popularity” and “caught, perhaps unawares, in another trap: her own facility in creating narratives. To keep her secret journal going, she unconsciously adapted her life to her narrative skill. Gradually she began to make life-choices shaped to fit the kind of story she was prepared to tell in that journal.”69 The back story of Montgomery’s communication with Saint Joan – as performance and text – sets the stage: it begins with Montgomery’s journey to North Bay on Tuesday (7 October 1924), where, on Wednesday, she gave a series of readings and lectures, including “to the girls in the Convent school in the forenoon . . . The Reverend Mother and Sister St John were very sweet and interesting women.” After several other speaking engagements, she took the night train back to Toronto; however, because of a six-hour delay, her plans to catch the morning train from Toronto to Leaskdale changed. “Now, mark! Had I caught that train home I would not have had a wonderful pleasure.”70 To whom is this passage addressed? To her journal, her understanding “friend and confidante,” as Thompson discusses more generally in chapter 6?71 It seems much more consciously crafted than Rubio and Waterston suggest, addressed to a posthumous audience witnessing the vicissitudes of L.M. Montgomery.

Montgomery was not as enamoured with Julia Arthur as the reviewers were: “Joan was never such a pink-and-white golden haired, brilliant, beautifully clad person. Only when I shut my eyes and listened to her wonderful golden voice did I get the conviction of the Maid.” Because Arthur was renowned for her coal-black eyes and hair, and because Montgomery voices this same objection about many of the Hollywood actresses in the movies that she attends, another variation on her perception of inauthentic celebrated women, her response to Saint Joan seems shaped primarily to provide an apposite medium for her lament, “Oh, if Frede could only have been sitting beside me while I saw that play.” She concedes that “Shaw’s play is a ripe and wonderful thing; but I don’t think his Joan is the real Joan either. That Joan is still an enigma.”72 Since she is an enigma, Joan’s story, like Frede’s – and Montgomery’s – can be told and retold – romantically, lyrically, satirically, farcically, comedically, tragically – and never be totally consumed. As Margaret Turner concludes, Montgomery’s process of reading and writing and responding “does not advance her or us toward an integrated subject, but rather keeps the multiple versions of the I that she constructs and lives active, relevant, and fluid.”73

Montgomery decides to attend the play only after her physical hunger has been assuaged – “the first food I had eaten since supper the evening before” – but her hunger for Frede’s companionship remains unsatisfied. Two days later, Montgomery records, “I have been re-reading Frede’s letters. I have not read them since the winter she died. But I have been so hungry for her lately – especially since seeing Saint Joan – that I had to get out the letters. Last night when I went to bed I thought I would read just one. Then I said ‘Just one more’ – and that went on till twelve o’clock. It was always ‘just one more.’ I was like a famished creature pleading for just one more bite of food.” What is it about Saint Joan that sends Montgomery on this binge of letter reading? She goes on to say that, with Frede, the façade of “laughter and satisfaction” characterizing her public personae was unnecessary; with Frede, her joy “was not pretence – it was reality,” or, as Mary Beth Cavert writes in chapter 2, when together, these two cousins “could be their true selves and confess feelings they could never express anywhere else.”74 In his Saturday Night review of the touring production of Saint Joan, Charlesworth captures the tragedy of Joan, whose ego can no longer provide a buffer against the jarring of the public personae against her soul: “After all there could be no more dramatic spectacle than that of an heroic soul striving to be true to itself in a maze of misunderstandings and antagonistic motives, – far more dramatic than battles and visions and escapes.”75 Although the “antagonistic motives” are not so clearly delineated in life as they are in art, this too is the tragedy of Montgomery as crafted in her journals: a woman who fights for the integrity of her soul in a commercial milieu that eventually consumes her, whether that consumption be of a ravenous public whose appetite needs feeding or the sputtering flames of a celebrity’s public personae, as Kate Sutherland describes in the previous chapter.

On 7 November 1925, the Globe reprinted excerpts from a sketch of Shaw by his first authorized biographer, Archibald Henderson, which had appeared several months before in the New York Times: “When I began to write about Shaw, more than twenty years ago, he was virtually unknown to fame. When people thought of him . . . they thought of a ghastly little celebrity dancing in a vacuum, a comical jack-in-the box ludicrously popping up at intervals to cry himself and his wares.”76 With this perception of literary personalities, then, it is not surprising that the remainder of Montgomery’s journal references to Shaw are rooted in metaphors of consumption that interrogate the degenerative cost of fame when celebrity depends on exhibiting only those personae that the public is willing to consume. Whether as “L.M. Montgomery” or “Mrs Ewan Macdonald,” her personae must be consistently self-effacing and optimistic; however, a close reading of the journals reveals self-absorption, pessimism, and a deteriorating strength to fight on in an increasingly alien world. The final mention of reading Shaw comes in November 1933: “Lately I have been having a debauch of George Bernard Shaw. Today I reread Androcles and The Lion. Shaw is very brilliant. I think he must be a reincarnation of Voltaire. And yet – satirically true as he is, his writings lack the essential truth after all. And he is too conscious of G.B. Shaw. He is always saying in effect, ‘Oh, am I not clever. You must think me tremendously clever. You can’t deny it. Listen to this and this.’” Montgomery may see Shaw as the public saw him, “a ghastly little celebrity,” and he may, as she alleges, produce “brilliant fireworks, not a permanent coruscation,” but “he tastes good” because his soul is that of a reincarnated Voltaire, which is what his plays rather than public personae reveal.77

In Literary Celebrity in Canada, York remarks upon the effect that the signage of the “iron bower” over the entrance to the Cavendish cemetery – with “Resting Place of L.M. Montgomery” writ large – must have on its resident community: “One wonders how families of others who rest there feel about Montgomery becoming the synecdoche for all of the Cavendish ancestors. It seems a strange kind of celebrity vampirism visited upon a community-host.”78 If Montgomery were to answer (as Joan does Cauchon in her tragedy’s Epilogue), she might say, “Your dead body did not feel the spade and the sewer as my live body felt the fire” – a passage Montgomery marked in her copy of Saint Joan.79 Rubio and Waterston’s conclusion to Writing a Life takes us back to the novels, a cultural product whose legacy, like Joan’s, withstands the consuming flames: “Montgomery exits from her journals suffering and silenced, perhaps believing they contained the true and only story of her life. But she was far from defeated – and far from silenced.”80 An examination of her final journey through the Valley of the Humber and her exposure to its cultural products reveals the tragic consequences of the erosion of the ego that leaves the soul vulnerable to conflicting demands on someone who has herself become a cultural product. It also reveals, however, a vulnerability that led to Montgomery’s final line of characters: the wife, mother, and grandmother Anne; the sister Rilla experiencing vicariously the pain of a brother who does not go unthinkingly to war; the artist Emily, whom Teddy Kent envisions as “Joan of Arc – with a face all spirit – listening to her voices”;81 the emotionally starved and psychologically abused Valancy Stirling and Robin and Jane Stuart; and the recalcitrant Pat, whose “home for generations [is] wiped out [by fire] . . . all its memories, all its possessions . . . in ashes!”82 And like Emily – “a chaser of rainbows” – who produces The Moral of the Rose after A Seller of Dreams has been consumed by the flames, and after “the delight and allurement and despair and anguish of the rainbow quest,”83 each of these characters, in her own way, maps a narrative arc characteristic of Montgomery’s own Ontario years: she travels westward and seeks a new home for herself far from Prince Edward Island.