Don Marcello Massarenti was a Roman priest and member of the papal court. For many years, he had served as a pontifical under-almoner. But beneath this veneer of respectability, Massarenti was a shadowy figure with an unsavory reputation. It was said that he was enamored more with the material than with the spiritual side of life. His position empowered him to dispense financial benefits, or alms, to churches and monasteries throughout Italy, likely providing him with the influence and connections to amass an enormous collection of approximately sixteen hundred works of art. Massarenti retained no records documenting the provenance of his artwork, and their origins have to this day remained mostly unknown. The dark side of his reputation stemmed from stories about his sexual predilections and his willingness to pander to the salacious practices of higher officials in the church.1 Whether by reason of Massarenti’s reputation or Walters’s personal dealings with him, Walters disliked Massarenti. He disparagingly referred to him as “the old man on the hill,” perhaps referring to the fact that he isolated himself in a small apartment in the Vatican that overlooked Saint Peter’s Dome. Massarenti’s collection of art was housed nearby on two floors of the Palazzo Accoramboni, which had been constructed in the seventeenth century and was prominently located at the eastern end of Bernini’s colonnaded extension of Saint Peter’s Piazza.2

In 1881, Massarenti published a catalogue of his collection, which at that time included 309 paintings, most of which were allegedly by Italian masters.3 Thereafter, the collection grew tremendously. By 1897, it numbered 848 paintings, and Massarenti, who was approaching his ninetieth birthday and was almost blind, decided to sell the entire collection.4 He retained the Dutch artist, Edouard Van Esbroeck, to organize the collection and to write a new catalogue describing it. That catalogue, entitled Catalogue du Musée, was published in 1897 and followed in 1900 by a supplemental catalogue that described an additional 62 paintings that had been added to the collection.5 Thus, in 1902, at the time of Henry Walters’s visit, the Massarenti collection had approximately 930 paintings. Of these, 520 paintings were by Italian artists.

The catalogue published in 1897 expressly informed the public that the art was available for purchase. Written in French, the catalogue was addressed primarily to potential purchasers on the mainland of Europe. The catalogue’s introductory remarks were tantamount to an infomercial—transparently disingenuous and full of fluff. It claimed that it was a collection “of the highest order” and that it “would add to the renown of any foreign city.” It claimed that the paintings were assembled during the previous thirty years from “illustrious old families,” but it failed to provide specific information about the provenance of any of the paintings. It represented that the collection had been praised by many authorities in the field of Italian art, but it cavalierly dismissed any need to identify them. It stated: “As for its high value, we could draw support from numerous testimonies of competent persons who have visited it, but we consider these citations superfluous.” What Massarenti characterized as “superfluous,” most prudent collectors would have considered as essential. Devoid of any endorsement by a specialist in Italian painting and crammed with transparently fictitious attributions, the Massarenti catalogue was like a red flag that warned potential buyers to proceed with caution.

The catalogue attributed many of the paintings to the greatest Italian artists. According to the catalogue, there were two paintings by Botticelli, one by Giovanni Bellini, four by Bronzino, six by Caravaggio, one by Annibale Caracci, six by Correggio, a pair painted jointly by Domenichino and Reni, one by Dossi Dosso, three by Giotto, three by Giorgione, three by Ghirlandaio, one by Leonardo de Vinci, two by Filippo Lippi, two by Mantegna, one by Masaccio, one by Antonello da Messina, two by Michelangelo, two by Pollaiuolo, two by Raphael, seven by Titian, four by Tiepolo, one by Tintoretto, five by Veronese, and four by Verrocchio. As suggested by the remarkable array of Renaissance and Baroque masters whose names filled the catalogue, the Massarenti collection of paintings, in a very real sense, was the quintessential product of Italy’s culture of copying—a collection perhaps more than any other ever acquired that serves as a laboratory to study the innumerable misattributions of Italian paintings that had been made during the course of the previous four centuries. Anyone vaguely familiar with the traditional practice of imitation and reproduction in Italian cultural history and the consequent confusion about who painted what would have approached Massarenti’s attributions with a mixture of two-thirds skepticism and one-third hope that below the surface of the misrepresentations were some authentic treasures of Renaissance art.

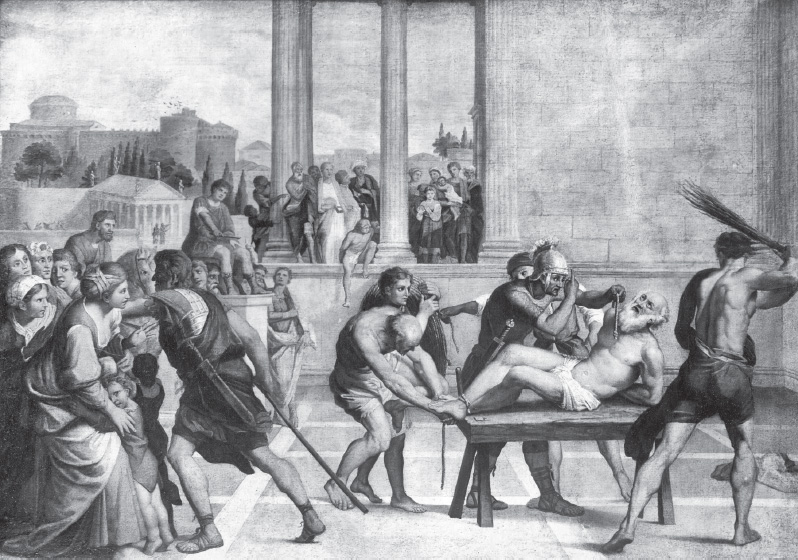

Massarenti crammed his paintings into approximately ten dimly lit rooms. As evidenced by vintage photographs of the Massarenti collection, the paintings were hung from floor to ceiling so closely together that their individuality merged into a collage of pictures and frames, leaving the identity of each painting largely dependent on a number which appeared at the bottom of its frame.6 Some of the paintings were hidden behind others and could not be seen at all. The purported gems of the collection, such as the paintings attributed to Raphael and Michelangelo, were displayed on easels in front of the other paintings (fig. 4).

In several of the rooms, the paintings also competed for space with display cases full of small statues, vases, and other objects of decorative art that impeded any opportunity to closely examine the paintings. The difficulty in seeing many of the paintings was further compounded by layers of discolored varnish that darkened the surface and obscured important details.7 A reporter for the New York Times aptly captured the problem by writing that “the pictures hung on two floors of the gloomy palazzo . . . where it was difficult to see them and where it was impossible to see them without a special introduction from Msr. Massarenti.”8

Although the floor-to-ceiling manner in which the paintings were displayed was consistent with museum practice at that time, the lack of light and congested surroundings created a claustrophobic atmosphere that was not conducive to the leisurely enjoyment or close examination of fine art. This problem is reflected in the photographs and also revealed in the anecdotal account of a visit to the Massarenti collection in 1898 by the famous London and New York art dealer Joel Duveen and his nephew James Henry Duveen. Upon entering the collection, Joel Duveen’s first request was for “better light,” but his guide responded that better light was unavailable. Duveen reiterated his displeasure, directing the guide to “take me to something I can see.” When the guide again indicated with a negative shrug that the problem was not remediable, Joel Duveen responded, “I don’t like the atmosphere of this place.” After quickly looking at several paintings that he characterized as ghadish, a derisive Yiddish word meaning imitations, Duveen and his nephew promptly walked out.9

While the manner in which Massarenti displayed his paintings lacked aesthetic appeal, there was an effort to rationally organize and divide the Italian paintings into eleven schools of art in a manner that had been advocated by Morelli. The schools, designated primarily by their location, were Tuscany, Tuscany/Florence, Bologna, Lombardy, Ferrara, Parma, Umbria, Turin, Venice, Naples, and Byzantine. According to the catalogue, the paintings in each school were displayed together in one of the ten salons. The paintings and their artists, the catalogues claimed, could be identified by the numbers on the paintings, which corresponded with the numerically organized descriptions of the paintings in the catalogues.

FIGURE 4. Salle V in the Massarenti Gallery, Rome, about 1900, crowded from floor to ceiling with paintings attributed to great masters. The paintings on display purportedly included Saint Francis of Assisi attributed to Annibale Carracci (now his workshop, WAM 37.1920); Saint Mary Magdalen attributed to Caravaggio (now Sparadino, WAM 37.651); The Mourning Virgin attributed to Guido Reni (now his workshop, WAM 37.492); Battle Scene attributed to Paolo Uccello (now School of Ferrara, WAM 37.499) and featuring self-portraits purportedly by Raphael and Michelangelo mounted on easels in front of the other paintings. Photograph WAM Archives.

The execution of the plan set forth in the catalogue stumbled badly for several reasons. First, scattered throughout the collection were blatant copies of famous paintings by Italian old masters, such as Titian’s The Worship of Venus, and Correggio’s Allegory of Vice and Allegory of Virtue. The second, more pervasive problem involved the sheer number of paintings that carried erroneous attributions. Although Massarenti might not have recognized the extent of this problem, more than two-thirds of his paintings were probably attributed to the wrong artist. Because the attributions were in general problematic, Massarenti’s effort to organize his paintings by the locations where the artists resided and the schools of art to which they belonged was futile. The Massarenti catalogue simply failed to satisfy the basic Morellian principle demanding that any analysis of Italian art begin with the accurate identities of the artists who painted the individual works of art.

Among myriads of apparent misattributions in the Massarenti collection, six paintings exemplify the pervasive nature of the problem: an easel-sized portrait that, according to Massarenti, was a rare self-portrait by Michelangelo; a pair of paintings purportedly co-authored by two of the masters of Italian Baroque art, Domenichino and Guido Reni; a painting attributed to Caravaggio and described as a small version of The Entombment, one of his best-known masterpieces; a painting purportedly by Titian of Christ and the Tribute Money; and a painting that appeared to be of a woman dressed in black and apparently in mourning by a relatively unknown artist by the name of Sabastiano del Piombo.

With regard to the self-portrait purportedly by Michelangelo (see fig. 3), Massarenti was not content in simply claiming to possess this painting. He also asserted that it was the only painting of its kind. Moreover, he wanted prospective buyers to believe that Michelangelo remained virtually alive in the painting and that, by acquiring the painting, the purchaser would hold the key to nothing less than Michelangelo’s soul. According to the catalogue, Michelangelo’s self-portrait was “the only and unique portrait of this master . . . His features are sculpted, the design is tight and powerful, the unity is perfect, and the forms are of an unparalleled grandeur and simplicity.” All of these qualities, Massarenti contended, combined to capture “the soul of this giant.”10 If this were so, of course, it would have been one of the most treasured paintings in art history.

There is no need to rehearse the singular fame and standing of Michelangelo. It is sufficient to recognize that Michelangelo’s life and art were the subjects of extraordinary documentation both through the meticulous records and drawings he maintained and in the biographies written by Vasari in the first and second editions of his Lives and by Ascanio Condivi, Michelangelo’s studio assistant, whose biography of Michelangelo is widely acknowledged to have been directed by Michelangelo himself.11 In 1892, shortly before Massarenti published his catalogue and placed his collection on the market, an extensively researched, two-volume biography written by John Addington Symonds updated Vasari’s and Condivi’s earlier biographies.12 If Michelangelo had painted a self-portrait, surely the rarity and importance of this painting would have been mentioned by Vasari, Condivi, or Symonds. However, no mention of a self-portrait appeared in any of these biographies, and it was understood then as now that Michelangelo rarely painted any easel-sized paintings and never painted any easel-sized portrait of himself of the kind purported to be in the Massarenti collection.13 In light of the absence of any historical evidence that Michelangelo painted a self-portrait, Massarenti’s claim that he was offering to sell such an extraordinary painting was astounding. It reflected at best a cavalier attitude in the assignment of attributions to the paintings in his collection as well as a hope to attract a buyer who was gullible enough to accept such a remarkable claim at face value.

In claiming that he owned Michelangelo’s self-portrait, Massarenti seized upon a resemblance of the man in his painting to two well-known portraits of Michelangelo. The first was a painting by Jacopino del Conte completed in 1540, when Michelangelo was sixty-five years old (now on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art). This image of Michelangelo obtained widespread currency in 1568 when it appeared in the opening pages of the second edition of Vasari’s Lives. The other portrait of Michelangelo was in the form of a bronze bust sculpted by Daniele Da Volterra in 1564, shortly after Michelangelo’s death (now on display at the Bargello in Florence).14 Probably modeled after Conte’s painting or Volterra’s bronze bust, the painting in the Massarenti collection captured Michelangelo’s distinctive features—a broken nose that was flattened at its bridge, deep-set eyes, high cheek bones, and a mustache and long sideburns that together were combed into a beard about two inches in length. By the end of the nineteenth century, easel-sized paintings of Michelangelo’s portrait, which were based on Volterra’s model, abounded in the marketplace. It is likely that one of these copies by an anonymous artist is what landed in Massarenti’s collection and what he effusively mischaracterized as Michelangelo’s unparalleled self-portrait.

A second example of the misattributions in the Massarenti collection involves two pictures that Massarenti claimed were jointly painted by two of the masters of Baroque art, Domenichino and Guido Reni (figs. 5 and 6). According to the Massarenti Catalogue, the paintings were completed by Domenichino and Reni around 1620 when they were working in Rome on frescoes in the oratory of Saint Gregory in the church of San Gregorio Magno al Celio. (“Ces deux peintures furent faites pour concourir a l’execution des deux fresques si vantees de l’Oratorie de St. Gregorie, aumont Celius.”)15 By referring to the oratory of Saint Gregory, the catalogue misleadingly suggested that the painting depicted the martyrdom of Saint Gregory. That was certainly the understanding of Henry Walters, who, after acquiring the Massarenti collection, entitled both paintings as the Martyrdom of Saint Gregory and attributed both to “Domenichino and Guido,” as if they were joined at the hip.16

There was little more than a grain of truth in Massarenti’s description of these two paintings. Domenichino and Reni were both born in Bologna, became friends and fellow students in the Carracci Academy, and early in their careers followed similar paths to Rome, where they became celebrated masters of Baroque painting and collaborated in the painting of two magnificent frescoes in the same oratory. Practically everything else in Massarenti’s description of these two paintings was inaccurate. The subject of the paintings, the location of the paintings, the date of their completion, and the notion that these two paintings were jointly painted by Domenichino and Reni all represent departures from the two paintings’ well-documented history known at that time.17 In 1608, Guido Reni received an important commission from Cardinal Borghese to decorate two oratories near the church of S. Gregorio Magno on the Caelian hill in Rome. One of these oratories was dedicated to Saint Andrew. The plan to decorate the Saint Andrew Oratory called for two frescoes depicting the martyrdom of Saint Andrew to be painted as fictive tapestries on two long side walls facing each other in the oratory. Although Reni was in charge of the entire project and painted one of the frescoes, known as Saint Andrew Led to his Martyrdom, Domenichino managed to obtain the commission to paint the other fresco, known as the Flagellation of Saint Andrew.18 Both were completed around 1609. These are the paintings that served as the models for the small copies in the Massarenti collection, which were mischaracterized as the Martyrdom of Saint Gregory.

The notion that Reni and Domenichino painted these two pictures together collides with the fact that, by 1609, the two painters had developed sharply contrasting styles that would have made any collaboration on the same painting extremely awkward and highly unlikely.19 Domenichino’s composition, which focuses on Saint Anthony on the rack at the moment of his martyrdom, appears stiff and disjointed, with different participants in the event grouped unnaturally together. In contrast, Reni’s composition flows from figure to figure almost poetically. Reni’s painting depicts the moment when Saint Andrew, while being led to his death, stopped and knelt in prayer upon receiving a vision of the crucifixion.20 In the late nineteenth century, when Massarenti was marketing these paintings as being created jointly by Domenichino and Reni, the two paintings were understood by both art historians and the general public as having been produced by different hands. For instance, two of the most respected guides to Italian art, Burckhardt’s The Cicerone and Baedeker’s Handbook for Travellers, clearly drew a distinction between Reni’s picture of Saint Andrew on the way to execution and Domenichino’s picture of the execution.21 Thus, contrary to the assertion by Massarenti, the paintings did not represent an amalgamation of the styles produced jointly by the hands of these two painters but, as the art historian Stephen Pepper has observed, two distinctly different paintings in which “each artist . . . executed the work assigned to him in his own style.”22 The misrepresentations in the Massarenti catalogue regarding these two paintings well illustrate its unreliability and its primary goal of attracting potential buyers rather than providing scholarly information about the works of art.

FIGURE 5. Copy by unknown artist of Domenichino’s Scourging of Saint Andrew. Massarenti and Walters mislabeled the painting Martyrdom of Saint Gregory and characterized it as a “Study by Domenichino and Guido.” In 1922, after Berenson’s examination of the painting, Walters disposed of it, and its present owner is unknown. Photograph WAM Archives.

FIGURE 6. Copy by unknown artist of Reni’s Saint Andrew Adoring the Cross. Massarenti and Walters also mislabeled the painting Martyrdom of Saint Gregory and likewise attributed it to both Domenichino and Reni. Along with its companion, Walters disposed of this painting in 1922, and its present owner is unknown. Photograph WAM Archives.

According to the Massarenti catalogue, The Descent from the Cross (fig. 7), purportedly by Caravaggio, was a small replica of the larger, well-known painting that was in the Vatican (“Replique en petit de la Deposition de la Croix existante dans la Galeria Vaticane”).23 This would have been remarkable because Caravaggio, unlike Guido Reni, rarely made any replicas of his own paintings. This was due in large measure to his practice of employing live models whom he individually posed and carefully illuminated to create the realistic scenes that he painted.24 On the other hand, following his death in 1610 and for the next thirty years during which Caravaggio’s fame ascended, his paintings served as models for young artists who converged on Rome to study painting and to compete for commissions. As a result, copies of Caravaggio’s paintings became legion in Italy and beyond.25 The popularity of Caravaggio’s paintings as models for other artists was reflected in the Massarenti collection, which claimed to have six paintings by him. Except for the paintings attributed to Titian, there were more paintings in the Massarenti collection purportedly by Caravaggio than by any other artist.26

FIGURE 7. The Descent from the Cross attributed to Caravaggio. Massarenti and Walters attributed this painting to Caravaggio. It was described in Walters’s 1909 catalogue as a “Replica, in small, of the painting in the Vatican.” Based on Berenson’s advice, Walters disposed of this painting in 1922, and its present owner is unknown. Photograph WAM Archives.

Among the most admired and copied paintings by Caravaggio was his Entombment (which Massarenti named The Descent from the Cross), in which Caravaggio depicted the athletic, nude body of Christ being dramatically lowered toward an open tomb by Nicodemus and John the Evangelist, whose hand simultaneously touches the open wound on Christ’s side, while Mary lowers her head in mourning and the Magdalene raises her arms in grief.27 The painting was created in 1604 and strategically placed above the sacramental altar in the Vittrici Chapel in the Church of Chiesa Nuova in Rome. For the faithful looking up in awe at this painting, it was as if the body of Christ was being handed down to them literally in a manner that merged the symbolism of the Eucharist with the realism of Caravaggio’s brush. This dramatic painting was praised from its inception. Bellori, the highly regarded seventeenth-century critic of Baroque art, characterized it as “among the best works ever made by Michale [Caravaggio] and is therefore justly held in highest esteem.”28 It was so highly venerated that Rubens, while in Rome in 1609, created his own version of Caravaggio’s painting. Although Berenson initially frowned upon Caravaggio, toward the end of his life he converted into a champion of his art, characterizing him as the most serious and interesting Italian painter of the seventeenth century and acknowledging that his Entombment was “considered one of the greatest masterpieces of art.”29

The Entombment remained in the Vittrici Chapel until 1797, when, as a result of Napoleon’s defeat of the Papal States, it, along with over a thousand other Italian old-master paintings and other treasured works of art (such as the Laocoön and the Apollo Belvedere) were shipped as spoils of war to Paris and placed in the Louvre. Anticipating the transfer of Caravaggio’s Entombment to France, the Church of Chiesa Nuova commissioned Vicenzo Camuccini, the renowned copyist, to paint a replica of it. The Camuccini Entombment replaced the Caravaggio painting above the altar of the church. When Caravaggio’s painting was repatriated to Rome in 1817, it was not returned to the church but instead entered the collection of the Pope in the Vatican, where it has remained to this day. As a result, after 1817, there were in Rome two prominently displayed paintings of the Entombment, one being a mirror image of the other.30

Over the centuries, one copy of the Entombment seems to have spawned another, resulting in more than one hundred renditions of Caravaggio’s famous painting finding places in prominent collections and galleries across Europe.31 Although Caravaggio’s fame had lessened in the nineteenth century, the Entombment, more than any other painting in his oeuvre, retained its fame, and for that reason, it was prominently displayed by Massarenti in his collection. There should have been little doubt, however, that the painting was by an unknown albeit highly skilled copyist.

Around 1518, Titian painted Christ and the Tribute Money, a copy of which was in the Massarenti collection (fig. 8). The painting depicted the moment described by Matthew in the Gospels when Christ was approached by a Pharisee, who, intent on entrapping him into committing treason, asked whether the Pharisees were permitted to pay taxes to the Roman emperor. Christ requested the Pharisee to show him the coin used for the tax, and upon recognizing the face of Caesar on the coin, replied philosophically, “Then pay to Caesar what belongs to Caesar, and to God what belongs to God.”32 Titian’s memorable painting emphasized the difference between good and evil, as embodied in Christ and the Pharisee. He contrasted the beautifully luminous face of Christ, his perfectly straight nose, and elegant fingers with the rugged, beastlike countenance of the Pharisee, whose hooked nose, boxed ear, gnarled hand, and darker skin, all of which were punctuated by a garish ring that hung from his ear, suggested that he had recently emerged from an inner circle of hell. It was a study of Christ’s divine confidence and self-control when faced with the perils of those who would maliciously harm him. From the time of its execution to the end of the nineteenth century, the painting was extolled as one of Titian’s masterpieces. By the end of the nineteenth century, the painting had found a permanent home in Dresden’s Gemäldegalerie.

Massarenti acknowledged that one version of this famous painting was in Dresden but claimed that Titian had made two more replicas of the same painting, one of which was in his own collection. Massarenti’s catalogue characterized his version as “a masterpiece by a great master” (“C’est un chef d’oeuvre du grand maitre”). To prove that his version was painted by Titian, his catalogue noted that the painting was signed by the master, “Ticianus, F.” Massarenti strategically placed the painting on a picture stand near a large window in a manner that emphasized its importance and provided viewers with additional light with which to inspect it (fig. 9).

The painting, however, was not by Titian. It was a copy of Titian’s painting made in the seventeenth century, approximately one hundred years later, by Domenico Fetti. Fetti was born in Rome in 1588 and at the age of twenty-five became the official court painter to Duke Ferdinando Gonzaga of Mantua and the superintendent of his significant art collection. Fetti’s fame was based primarily on his paintings of New Testament parables, in which the spiritual teachings of Christ about the difference between good and evil were imparted to his followers.33 In 1621, Fetti traveled to Venice for the purpose of purchasing art for the duke and was subjected to the influence of Venetian painting, including the work of Titian. It is not precisely known when, where, or what motivated Fetti to copy Titian’s painting of Christ and the Tribute Money, but it is likely that the Duke of Mantua, aware of Fetti’s skill in painting scenes depicting Christ’s teachings as well as his ability to emulate the colors of Titian, requested that he copy Titian’s painting for his collection. The painting illustrates the practice of prominent artists, at the request of their patrons, of painting copies of famous paintings by earlier Renaissance masters.34

FIGURE 8. Domenico Fetti, Copy of Titian’s Christ and the Tribute Money, ca. 1618–20, oil on panel, 31¼ × 22⅛ in. WAM 37.582. Massarenti attributed this painting to Titian and claimed that it was signed by him. Echoing this assertion, Walters claimed that this painting as well as the self-portraits by Michelangelo and Raphael “have the names of the artists upon them.” Photograph WAM Archives.

FIGURE 9. Salle I in the Massarenti Gallery, Rome, about 1900. In the upper right-hand corner of the room is a portrait purportedly of Catherine de’ Medici attributed to Bronzino (now workshop of Allesandro Allori, WAM 37.1112), but the main attraction in the room was the painting of Christ and the Tribute Money attributed to Titian, which was prominently placed on an easel in front of the other paintings. Photograph WAM Archives.

Perhaps the most remarkable misattribution was attached to an easel painting, which had been darkened with veneer, of a woman solemnly dressed in black as if in mourning. Practically hidden from view, it hung just above the floor in the dark corner of a room full of paintings in a manner that suggested that it was unworthy of attention (fig. 10). The painting, according to Massarenti’s catalogue, was by Sabastiano del Piombo, a relatively unknown artist, and depicted the sixteenth-century poet Victoria Colonna.

FIGURE 10. Salle in Massarenti Gallery, Rome, about 1900, with a portrait of Maria Salviati de’ Medici by Pontormo, mistakenly identified as a portrait of the poet Victoria Colonna and misattributed to Sebastiano del Piambo. The painting was relegated to a dark corner of the room near the floor, where it was unlikely to be noticed. Photograph WAM Archives.

Walters initially adopted this attribution when he opened his museum in 1909. Five years later in 1915, however, following Berenson’s inspection of Walters’s collection, the Colonna painting happily was reattributed to Jacopo Pontormo, the most prominent painter in Florence toward the middle of the sixteenth century and a favorite artist of the Medici.35 Because the identity of the woman painted by Pontormo was unknown, the painting was simply entitled “Portrait of a Lady.” The importance of the painting was further elevated in 1937 when the “lady” was identified as Maria Salviati de’ Medici, the granddaughter of Lorenzo de’ Medici and mother of Cosimo de’ Medici, who became Duke of Florence in 1537 (fig. 11). Furthermore, a careful cleaning of the painting that year revealed that it was actually a double portrait of Maria Salviati and a child, whose image had been painted over (fig. 12). The child in the Pontormo painting was subsequently identified as Giulia, the illegitimate African European daughter of Duke Alessandro de’ Medici, whose assassination in 1537 led to the selection of Cosimo as duke. Following Alessandro’s death, Maria Salviati looked after Giulia with the care and tenderness reflected in Pontormo’s double portrait. The importance of the painting of Maria Salviati and Giulia in mourning lies not only in the fact that it was painted by Pontormo but also in its visualization of a significant page of Renaissance history.36

FIGURE 11. Pontormo’s Portrait of Maria Salviati de’ Medici before its restoration. Walters adopted Massarenti’s attribution, and in his 1909 catalogue, Walters referred to Sebastiano del Piambo as the artist. After Berenson’s examination of Walters’s collection in 1914 and based on Berenson’s advice, Walters upgraded the attribution to Pontormo in a new catalogue that was published in 1915. Photograph WAM Archives.

FIGURE 12. Pontormo’s Portrait of Maria de’ Salviati with Giulia de’ Medici, ca. 1539, oil on panel, 34⅝ × 281⁄16 in. WAM 37.596. When Walters acquired this painting from Massarenti in 1902, the young girl was painted over. In 1937, six years after Walters’s death, the painting was restored and the young girl discovered. The young girl has been identified as Giulia, the daughter of Duke Alessandro de’ Medici, heir to the leadership of the Florentine Republic, who was assassinated in 1537. Following Alessandro’s death, Giulia was cared for by Maria de’ Salviati, the mother of Cosimo de’ Medici. Pontormo pictured Giulia holding onto the long elegant fingers of Maria while both appear to be in mourning. Photograph WAM Archives.

As illustrated by the unrecognized painting by Pontormo, scattered in Massarenti’s field of misattributed copies were genuinely important paintings of quality that helped to frame the history of Italian art from the thirteenth to the eighteenth centuries. Some were truly by well-known artists, such as Pietro Lorenzetti, Giovanni di Paolo, Fra Filippo Lippi, Carlo Crivelli, Giulio Romano, Rosso Fiorentino, Jusepe De Ribera, Bernardo Strozzi, and Giambattista Tiepolo. Other paintings, such as The Ideal City, evoked a time and place in Renaissance history in a manner so astounding to the eye and mind that the identity of its author was unnecessary. From the time that The Ideal City (see plate 2) was displayed in the Massarenti collection to the present, twelve different artists or anonymous members of different schools of art have been identified by various scholars as its likely painter.37 The inability to reach any agreement as to its authorship has not kept the painting from being universally admired as one of the Renaissance’s great masterpieces. Thus, below the surface of Massarenti’s collection of bogus masterpieces was an array of paintings that were of the kind and quality which, Walters believed, would tell the history of Italian painting.38

Massarenti’s goal was to keep his collection intact and to sell it to someone who was willing to purchase the whole thing and who would allow the collection to carry his family name. He could not find any European collector who would accept these terms. Like Joel Duveen, most Europeans doubted the attributions given to the paintings and considered the collection as a whole to have little value. Unable to entice any European collector to buy it, Massarenti turned to the United States for prospects. He retained the services of J. H. Senner, an American attorney and journalist, who had served as U.S. commissioner for immigration in New York. There was nothing in Senner’s background to indicate any expertise in the field of art. By reason of his legal training and governmental experience at Ellis Island, however, he was familiar with the regulatory nuts and bolts of bringing Italian works of art into the New York harbor and was able to bring this special knowledge to the bargaining table. Moreover, he was familiar with New York’s upper-crust collectors and brought the availability of the Massarenti collection to their attention. Senner’s initial objective was to sell the collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but when this failed to materialize, he offered the collection to Walters. His instrumental role in selling the Massarenti collection to Walters was recognized by the New York press: “To him [Senner] is due the credit of having called the attention of Mr. Walters to it, in order to secure it for America.”39