Walters began acquiring paintings from Berenson in the summer of 1910. Among his initial acquisitions was an altarpiece in the form of a triptych by the Venetian artist Niccolò Rondinelli. It was entitled Madonna and Child with Saint Michael and Saint Peter (fig. 15).1 Berenson subsequently described Rondinelli as “perhaps the most prominent of Bellini’s followers,” and he characterized the painting he sold to Walters as closely following the architectural designs and figurative drawing of this master.2 The painting depicts Mary and Jesus enthroned under an elaborately coffered arch that corresponds with the circular lines of the Madonna’s halo and serves to emphasize her divinity. To the right of the Virgin is Saint Peter, characteristically holding the papal key, while to the left is Saint Michael engaged in battle against the forces of evil. The painting is reminiscent of Giovanni Bellini’s famous altarpiece of the Virgin and Child in the Church of San Zaccaria in Venice. Walters must have been delighted with this painting, for he proceeded to purchase thirteen more paintings from Berenson during the first year of their contractual relationship and an additional twelve paintings during the second year. According to their correspondence and telegrams, during the course of six years from July 1910 through July 1916, Walters purchased at least thirty-six paintings from Berenson and possibly more (see appendix B, list 1).3

As exemplified by Rondinelli’s painting and its devotional subject matter, the paintings Walters acquired from Berenson were by Italian artists who worked primarily in the second half of the fifteenth and first quarter of the sixteenth centuries and who painted traditional religious themes and motifs that preoccupied the artists of that time. Twenty-four of the paintings depicted the Madonna and Child either by themselves or in Sacra Conversazione with saints or donors by their sides. Other paintings depicted well-known episodes in the life of Jesus and Mary, such as the Annunciation or the Nativity, or episodes in the lives of saints, such as Susannah and the Elders, Saint George and the Dragon, and Saint Jerome in the Wilderness. In contrast, only six paintings depicted secular or non-Christian subjects; five were portraits and one was a mythological landscape.

FIGURE 15. Niccolò Rondinelli, Madonna and Child with Saint Michael and Saint Peter, ca. 1497–1500, oil, tempera, and powdered gold on panel, 34 × 18⅜ in. WAM 37.517 A, B, C. The painting was acquired by Walters from Berenson in 1910, around the beginning of their dealer-client relationship. Berenson referred to Rondinelli as “perhaps the most prominent of Bellini’s followers.” Although the painting was represented to Walters as a triptych, it was later discovered that the three panels had been sawed out of a single altarpiece and repaired and repainted to conceal the damage. Photograph WAM Archives.

Walters, as a general rule, left the selection of each painting entirely to Berenson, reserving for himself the final decision about whether to purchase it. In only two cases did Walters express an interest in acquiring a painting by a specific artist. On one occasion he requested that Berenson find him an affordable painting by Sassetta, one of the leading Sienese painters of the fifteenth century; it was a request that remained unfulfilled.4 On another occasion, he requested Berenson to assess the quality and authenticity of a painting that a Venetian dealer was seeking to sell to him. It was entitled Portrait of a Woman as Cleopatra and was purportedly by Paris Bordone, a student of Titian and one of the most accomplished painters of portraits in Venice. With regard to the Bordone painting, Walters wrote to Berenson, “I told him [the Venetian dealer] that I could not consider it unless it were submitted to me and recommended by you.”5 Other than expressing an interest in these two paintings, Walters expressed to Berenson no preference for any particular artist, school of art, style, or subject matter.

A variety of factors influenced Berenson’s selection of paintings for Walters. They included the reputation of the artists, the price of the paintings, and their availability. The issue of availability was influenced not only by the variables at play in the marketplace but also by factors over which Berenson exercised significant control. Among the thirty-four paintings that Berenson sold to Walters, eight came from Berenson’s own collection.6 One cannot state with any certainty whose interest was best served by these transactions. In proposing that Walters acquire the painting of the Madonna and Child by Cosimo Rosselli (fig. 16), Berenson combined spoonfuls of candor and exaggeration as if they came from the same jar. He candidly informed Walters that the painting belonged to him but that he was interested in disposing of it because his wife “Mary has the bad taste not to like it.” Then, in the same sentence, Berenson added that, “it is one of the best things that this not inconsiderable artist ever did.”7 Berenson’s praise of his own painting appears, in retrospect, to have been little more than a shallow effort to sell it. Years later, in illustrating what he believed were Rosselli’s best paintings, Berenson referred to a painting of the Madonna and Child in the Kress Collection of the National Gallery of Art and a second painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He made no reference to the painting he sold to Walters.8

Another painting that Berenson sold to Walters from his own collection was a Madonna and Child by Bernardo Daddi (see plate 4). In this case, Berenson’s motivation for disposing of the painting seems clear. In January 1911, Berenson acquired a second painting of a Madonna and Child by Daddi, which he admired more than the other painting by Daddi.9 In February 1911, Berenson attempted to sell his first Daddi to John G. Johnson.10 When that failed, Berenson offered it to Walters, who acquired it in October of that year.11

FIGURE 16. Cosimo Rosselli, Madonna and Child, ca. 1480, tempera on panel, 17 × 11½ in. WAM 37.518. This painting, which was in Berenson’s private collection, was sold to Walters in 1911. Berenson informed Walters that it was “one of the best things that this not inconsiderable artist ever did” and that he decided to sell it to Walters because his wife had “the bad taste not to like it.” Walters responded that “I am more than delighted to have the one from your collection,” and with a touch of humor he added, “I thank Mrs. Berenson most sincerely for not liking it.” Photograph WAM Archives.

The availability of the paintings Berenson selected for Walters was also influenced by Berenson’s need to balance his obligation to find paintings for Walters against his obligation to find Italian paintings of similar quality for other clients. During the period when Berenson was actively selling Renaissance and Baroque paintings to Walters, he was also actively engaged in selling paintings in the same price range to John G. Johnson. From 1910 to 1912, Berenson was proposing paintings on a regular, weekly basis to both Walters and Johnson. Johnson had informed Berenson that he was not interested in purchasing additional paintings of the Madonna and Child, a fact that helps to explain why such paintings were regularly offered to Walters. In at least two cases, Walters was offered paintings that Berenson had previously offered to Johnson. Both of the paintings came directly from Berenson’s personal collection. They were the aforementioned Madonna and Child by Bernardo Daddi and a Portrait of a Baby Boy by Bronzino (see plates 4 and 5). If Berenson gave Johnson first choice on some paintings, there were bona fide reasons for doing so. Not only had Johnson retained Berenson as an adviser several years before Walters had done but had also agreed to pay him a healthier commission of 15 percent of the price of the paintings in contrast to Walters’s commission of 10 percent.

Regardless of the factors that influenced Berenson’s selection of paintings for Walters, most of the artists who allegedly painted them were highly respected and well known by students of Italian art. There was nothing second-rate about them. Paintings by these artists were on display in the Uffizi and other major galleries in Florence, Venice, and Rome. Twenty-seven of these artists had been listed by Berenson as being among the “principal” Renaissance artists of Venice, Florence, Central Italy, and Northern Italy. In his Four Gospels of Italian Renaissance painters published between 1894 and 1906, Berenson provided concise descriptions of each of these artists and outlined the principal galleries, churches or private collections where their work was found.12 These four books had become standard reference manuals for collectors, and Walters undoubtedly would have referred to them if he needed to supplement the information about the artists provided in Berenson’s letters.

The thirty-six paintings sold to Walters by Berenson covered all of the regions of Italian Renaissance art. Seven of the paintings purportedly were by artists listed in Berenson’s book on Venetian Painters, six were in his book on Florentine Painters, seven were in his book on Northern Italian Painters, and six were in his book on Central Italian Painters. Turning first to the seven Venetian painters, the most celebrated was Tintoretto (1518–1594), who decorated the Doges Palace but left his mark on art history by his dynamic pictorial decoration of the Scuola di S. Rocco. The other Venetian artists whose work was sold to Walters by Berenson were Marco Basaiti (1470–1530), a follower of Giovanni Bellini, who painted in a style so close to Bellini’s that Berenson initially attributed Bellini’s Saint Jerome Reading, in the Kress Collection of the National Gallery, to him; Cima da Conegliano (1459–1518), who was considered to be one of the most captivating and creative students of Bellini and whose large altarpieces were viewed as among the most significant achievements of Venetian art; Antonio Vivarini (active 1440–1476), who remained devoted to the gothic style; Polidoro Lanzani (1515–1565), who was a follower of Titian; Bartolomeo Mantagna (1450–1523), who also was influenced by Giovanni Bellini; and, as noted above, Niccolo Rondinelli.

The six Florentine artists Berenson selected for Walters reflected the evolution of Florentine painting over two centuries. They were Bernardo Daddi (active 1300–1348), Bicci Di Lorenzo (1373–1452), Cosimo Rosselli (1439–1507), Bartolomeo Di Giovanni (active 1483–1500), Francesco Granacci (1477–1543), and, as noted above, Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572). Bernardo Daddi was a student of Giotto and among the most prominent Florentine painters during the first half of the fourteenth century. Although Daddi painted large altarpieces, one of which is in the Uffizi, his forte was small and intimate devotional paintings, as exemplified by the painting of the Madonna and Child that Berenson sold to Walters. Bicci Di Lorenzo’s paintings served as a bridge between the Gothic style of the fourteenth century and the realism of Masolino and Fra Angelico in the fifteenth century. His gold-leafed altarpiece of The Annunciation is considered one of the masterpieces in the Walters collection. Cosimo Rosselli was highly regarded in Florence and Rome, as evidenced by his selection around 1480 to join Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and Perugino in decorating the side walls of the Sistine Chapel, where he was responsible for painting The Crossing of the Red Sea. Bartolomeo Di Giovanni, who was also referred to by Berenson as Alluno di Dominico, was an assistant to both Botticelli and Ghirlandaio and specialized in painting predellas and panels for fine furniture. Francesco Granacci also was a student of Ghirlandaio and a lifelong friend of Michelangelo, who sought his technical guidance about fresco painting when working on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Bronzino was one of the most famous and gifted sixteenth-century mannerists and a favorite court painter of the Medici.

The eight North Italian painters selected by Berenson were Nicola Appiano, known as “Pseudo-Boccaccino,” who was from Milan and active in the first quarter of the sixteenth century; Barnaba da Modena (active 1361–83), who was born in Milan but was most active in Genoa and whose patrons extended from Italy to Spain; Bartolomeo Bramantino (1460–1529), another artist from Milan, who was one of the region’s most important painters and architects and who became the court painter to Duke Francesco II Sforza; Bernardino Butinone (1454–1507), a Milanese artist whose frescoes were celebrated in that city; Ercole De’Roberti (1430–1496), who was one of the greatest Renaissance painters of Ferrara; Giovanni Batista Moroni (1520–1578), an artist born near Bergamo, who was regarded as the greatest Italian portrait painter of the sixteenth century; Giorgio Schiavone (1443–1504), who worked mainly in Padua and is known for his brilliant colors and ability to depict rare and precious stones; and Sodoma (Giovanni Antonio Bazzi) (1477–1549), one of the leading painters in Siena during the sixteenth century.

The six artists who were listed by Berenson in his book on Central Italian painters were Antoniazzo Romano (active 1460–1508), who painted mainly in Rome, working with Ghirlandaio in decorating the library of the Vatican; Bernardino Fungai (1460–1516), whose best-known paintings decorated the Siena Cathedral; Benvenuto Di Giovanni (1436–1518), another well-established Sienese artist; Fiorenzo di Lorenzo (1440–1521), an Umbrian artist whose work is sometimes confused with Pintoricchio and whose most distinguished work was painted in Perugia; Giovanni Di Paolo (1403–1482), who was one of the greatest artists in Siena during the fifteenth century and whose art moved from Gothic traditions to highly original imaginary landscapes; and Lo Spagna (1450–1528), whose real name was Giovanni di Pietro and who, although born in Spain, produced his most remarkable work in Umbria. In addition to the artists who were listed in his four books on principal Renaissance painters, Berenson sold to Walters paintings by three relatively unknown artists: Pietro Carpaccio (active 1514–26), the son of the Venetian master Vittore Carpaccio; Nicolo da Guardiagrele, a Venetian artist; and Giovanni Mansueti (active 1485–1526), a Venetian artist who studied under Giovanni Bellini.

Walters’s letters to Berenson indicate that he was very satisfied with the paintings he acquired from him. He expressed not a single word of criticism about their quality or condition. To the contrary, the correspondence indicates that, to the extent that Walters looked at the paintings and paid any attention to them, he loved what he saw. For example, on February 7, 1911, he wrote to Berenson, “I am thoroughly delighted with the two portraits by Moroni and Tintoretto and with the Saint George by Carpaccio.” He added that “I have quite fallen in love with the photograph of the Fungai.” On June 9, 1912, he wrote to Berenson that, “Somehow the Cima [da Conegliano] is constantly before my eyes and also the remarkable [Francesco di] Rimini.” On February 14, 1914, he wrote, “Sodoma . . . is a great picture. I have the greatest delight in studying it.”13 Walters’s satisfaction with the paintings he acquired from Berenson was further evidenced by the fact that, in 1915, when Walters reorganized his collection of Italian paintings, he hung thirty pictures acquired from Berenson in place of paintings that he previously had acquired from Massarenti.

Walters’s favorable impression of the paintings offered by Berenson undoubtedly was influenced by Berenson’s hyperbolic, overly effusive descriptions. His letters to Walters slide imperceptibly from scholarly advice into rank salesmanship. For example, on November 4, 1911, Berenson recommended a “suave, gracious, distinguished” Madonna by Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, whom he described as “one of the big wigs of Italian Painting.” It was “a very great bargain,” Berenson claimed, and he urged Walters to acquire it because “these things are getting visibly rarer.” On December 16, 1911, Berenson urged Walters to buy Lo Spagna’s painting of The Holy Family with Saint John the Baptist, which he described as a painting that “has always passed for a Raphael . . . In a sense one can hardly blame them, for this picture is very Raphaelesque indeed . . . It is the finest Lo Spagna I have ever seen. It is extraordinarily clear and brilliant.” In the same letter Berenson recommended a painting of Madonna and Child with Saints Mark and Peter by Polidoro Lanzani, which he described as “near to being a Titian as any work I have ever seen . . . Here the color is as good as Titian in his very best years . . . [possessing] fully Titianesque radiance and magic.” On January 16, 1912, Berenson urged Walters to purchase a painting of the Madonna and Child by Nicola Appiano (known as the “Pseudo-Boccaccino”), which he described as “a blend of Venetian with Milanese qualities which makes him one of the most fascinating of Leonardo’s pupils in Milan. The Madonna I am proposing is as fine as any of his that I know . . . It is in excellent condition.” On November 9, 1912, Berenson recommended a painting of the Annunciation by Bicci di Lorenzo, which he described as “one of the most delightful works painted soon after 1400, & is the masterpiece of one of the most interesting figures of that time.” At the same time, Berenson proposed a painting of the Madonna and Child by Bernardino Butinone, which he characterized as “an appealing Leonardesque work of delicate sentiment & delicious colour . . . The naiveté of the landscape background is not easily to be surpassed, & the whole panel has an unusual sincerity & heartiness about it.”14 And, as noted above, in offering to sell his painting by Rosselli, Berenson characterized it as one of the artist’s “best” paintings. As evidenced by Berenson’s alluring descriptions, he was not offering to sell to Walters great paintings by Leonardo, Raphael, or Titian—Walters did not at that time covet such paintings but instead paintings by their followers that were “Leonardesque,” “Raphaelesque,” or “Titianesque” in flavor and that looked like they were completed by the hands of the great masters. (The letters from Berenson dated November 4, 1911; December 16, 1911; January 16, 1912; and November 9, 1912 are in appendix A.)

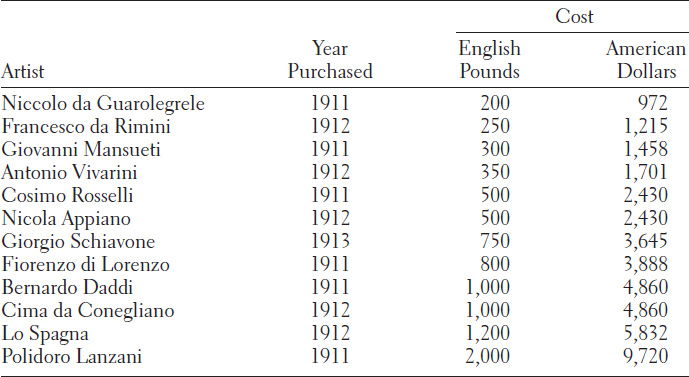

TABLE 1

Italian Paintings Acquired in 1911–1913

Walters must have been pleased with the opportunity to purchase paintings that often looked like a Raphael or a Titian but were dramatically less expensive. In comparison with the $100,000 or more that he reportedly spent for Raphael’s Madonna of the Candelabra, the paintings he purchased from Berenson must have seemed like a bargain. Based on Walters’s handwritten notes and the letters from Berenson, the prices appeared to range from approximately $1,000 to $10,000, with the average price being $3,584.15 This average price is roughly equivalent to $50,000 in today’s dollars. As evidenced by the prices he paid for these paintings, Walters’s strategy was to budget $75,000 per year to acquire dozens of paintings by important, although lesser-known Italian artists, instead of spending the same amount or more to acquire one painting by Raphael, Titian, or a comparable master of Renaissance art.

Three of the paintings Berenson sold to Walters are still viewed as being among the jewels of the Italian painting collection.16 They are Bicci di Lorenzo’s Annunciation, Bartolomeo di Giovanni’s Myth of Io, and Fiorenzo di Lorenzo’s Saint Jerome in the Wilderness (now attributed to Pintoricchio) (see plates 6 to 8). These paintings, in the context of the entire collection, help to trace the progression of Italian painting from the iconic, Gothic prototypes of the fourteenth century to the realism of the fifteenth century and later to the imaginary landscapes of the early sixteenth century. In Bicci di Lorenzo’s The Annunciation, painted around 1430, we can see a transition from the flat, golden backgrounds of Gothic art to early experiments with architectural perspective. In Pintoricchio’s Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, painted around 1475, we are invited to interpret a painting rich in iconography, as reflected in the cardinal-red hat, the domesticated lion, the scholarly text, and the rocky, ascetic environment. And in Bartolomeo da Giovani’s Myth of Io, painted in 1490, we see the influence of Ovid on the artist’s creation of an imaginary landscape, which combines features of the Nile valley and the Tuscan countryside and which is inhabited by a remarkable ensemble of Roman gods, shepherds, and animals.

Although Walters was apparently satisfied with the paintings he acquired from Berenson, over the years a more objective and critical assessment of the overall quality of these thirty-six paintings has emerged. The problem with the paintings did not involve their price. Nor did it involve the credentials of the artists who allegedly painted them. The problem, somewhat surprisingly, is that most of Berenson’s attributions have not withstood the test of time. More specifically, the attributions of twenty-two of the thirty-six paintings Berenson sold to Walters, or approximately two-thirds of Berenson’s attributions, have been overridden by modern scholars and no longer carry any currency.17 (See appendix B, list 2).

The painting of Saint George and the Dragon purportedly by Pietro Carpaccio (see plate 9), with which Henry Walters was “thoroughly delighted,” was dismissed in 1969 as a fake by the Walters Art Museum after it discovered that it was probably painted by an unknown artist in the nineteenth century, not in the early sixteenth century when Carpaccio painted.18 The painting by Fungai that Walters “had fallen in love with” was not by Fungai, but more likely by an unknown sixteenth-century Umbrian artist who was given the name of Master of the Liverpool Madonna.19 The painting by Cima that was “constantly before my [Walters’s] eyes,” also was determined, after a careful examination, to have been painted by one of Cima’s followers named Girolamo Da Udine.20 The painting purportedly by Tintoretto, which Walters purchased from Berenson in 1911, was downgraded to the “Manner of Tintoretto” and disposed of by the Walters Art Museum in 1951.21 The painting purportedly by Lo Spagna, which Berenson characterized as “Raphaelesque . . . [and] the finest Spagna I have ever seen,” was determined to be not by Lo Spagna but by an unknown artist of the Umbro-Tuscan school who based his painting upon “Raphael prototypes.”22 The painting that Berenson attributed to Polidoro Lanzani and which he praised as being “Titianesque” also has been reattributed to an unknown artist on the ground that “on the whole this painting differs from the artist’s [Polidoro’s] usual manner, and certain elements . . . are not characteristic of Polidoro’s style.”23 The painting purportedly by Bramantino has been downgraded to an unknown artist from the School of Ferrara.24 And the painting purportedly by Bernardo Daddi, which was in Berenson’s private collection before he sold it to Walters, has been downgraded to a painting done primarily by Daddi’s workshop.25

Other opinions expressed by Berenson about the paintings in the Walters collection also have not survived scrutiny. Around 1914, Walters acquired two paintings purportedly by Francesco Bonsignori, a Veronese by birth who was strongly influenced by Giovanni Bellini and other Venetian artists. The paintings, entitled Profile of a Warrior and Portrait of a Prelate in Black, were listed by Walters in the catalogue published, with Berenson’s assistance, in 1915.26 In Venetian Paintings in America, published in 1916, Berenson praised these paintings. He wrote that the Profile of a Warrior was the “finest and best constructed of Bonsignori’s portraits,” and its “attribution cannot be subject to dispute, for everything about it witnesses to the mind and hand of the master.” Berenson also wrote that “there can be no reasonable doubt” that Bonsignori also painted the Portrait of the Prelate. Years later, the Walters Art Museum concluded that Bonsignori painted neither of these pictures, and they were removed from the collection. A subsequent effort to sell these paintings through Christies for five hundred dollars failed, and they were donated to charity.27

In addition to Berenson’s misattributions, several of the paintings Berenson sold to Walters had been awkwardly restored and were not, as Berenson suggested, in pristine condition. The painting by Pseudo-Boccaccino of Madonna and Child, which Berenson represented as being in “excellent condition,” had been trimmed on all four edges, seriously overpainted in dark blue in one area, and carelessly overpainted in a dull red color elsewhere.28 A similar problem was discovered in the first painting that Walters purchased from Berenson, the purported triptych entitled Madonna and Child between Saint Michael and Saint Peter, by Niccolo Rondinelli. It originally had not been a triptych, as Berenson claimed, but instead had been a single painting that had been sawed apart, trimmed on all four sides, and in some sections repainted in an inexpert effort to restore it.29

How could Berenson, the preeminent connoisseur of Italian paintings who is credited with guiding the important collections of Isabella Stewart Gardner and Peter Widener and for serving virtually as an “adjunct curator” of the marvelous collection of Italian paintings at the National Gallery in Washington,30 have been mistaken so often when selecting paintings for Walters? There is no easy answer to this question. There is no hard evidence that Berenson intentionally misrepresented the attributions of any of the paintings he sold to Walters or intentionally concealed the poor condition of some of them. Although the attributions given by Berenson to the paintings sold to Walters appear in hindsight to often have been in error, these attributions did not at that time seem mistaken and were not challenged by other experts in the small, cutthroat league composed of connoisseurs who often promoted themselves by discrediting the attributions of others.31

It is difficult to measure the quality of all of the attributions given by Gilded Age connoisseurs to Renaissance paintings because there have been no firm, objective standards for doing so. Attributions given to paintings completed in Italy hundreds of years ago have not been set in stone but are subject to change based on the application of new evidence about the paintings and their artists. Accordingly, any effort to score the number of correct or incorrect attributions is relatively meaningless.32 The field of connoisseurship at the turn of the twentieth century was an intuitive and inexact science.33 Berenson’s attributions were not objectively measured or confirmed by x-rays, microscopes, chemical analyses, and other tools of modern conservators. They were instead simply the product of his intellectual memory and eye for art, which, while extraordinary, were far more fallible than his fame and swagger suggested. There was not at that time and there is not now any acid test for conclusively determining who painted what during the Renaissance and Baroque periods of Italian art. The difference between a “signature” painting completed primarily by a master and a painting completed primarily by the talented painters in the master’s workshop and under his supervision continues to be, in many cases, extremely difficult to discern. Although attributions given to Italian Renaissance and Baroque paintings based on the judgments of connoisseurs as famed as Morelli, Bode, and Berenson carry a presumption of validity, such attributions remain subject to challenge. A significant attribution—as David Alan Brown, the curator of Italian paintings at the National Gallery of Art, has observed—“is not necessarily one that we would take to be correct today. It is an attribution that was perceptive, given what was known about the artist at the time it was made. The attribution should have pointed in the right direction, even if it did not turn out to be finally correct.”34

Berenson had no misgivings about occasionally changing his own attributions based on additional visual evidence which, in his mind, enabled him to see paintings more clearly than before.35 In response to a question raised about an attribution to a relatively unknown artist, which he later changed, Berenson defended his earlier error on the ground that it was based only on “rudimentary” knowledge.36 A good example of the plasticity of Berenson’s attributions involves the changing opinions he offered about whether a painting in the Walters Art Gallery entitled Virgin and Child with Saints Peter and Mark and Two Kneeling Donors had been painted by Giovanni Bellini (see plate 12). In Venetian Paintings in America, published in 1916, Berenson concluded that this painting was not painted by Bellini. “I find it hard to believe,” he wrote, “that it was by Bellini himself.” Instead, he assigned the painting to “assistants who are nameless.”37 In 1932, Berenson offered a somewhat different opinion. In Italian Painters of the Renaissance, Berenson concluded that this picture was painted “in part by the artist [Bellini].” In 1957, he offered a third opinion. In his final, two-volume edition of Italian Painters of the Renaissance, Berenson concluded that the painting was “in great part autograph.”38 Thus, Berenson’s attributions progressed from not painted by Bellini, to painted “in part” by Bellini, to painted “in great part” by Bellini.39

The continuing uncertainty about the identity of the artists who painted renowned works of art is also illustrated by some of the best Italian paintings at the Walters Art Museum. One of the jewels of the collection is a painting entitled The Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist (see plate 13). The magic of the painting lies in its imaginary relationship between the vibrant figures of Mary, Jesus, and John the Baptist in the foreground and a classically designed, circular building crumbling with age, overtaken by nature, and sliding outside the frame of the picture in the background. The divine figures in the foreground and the antique structure withering away behind them were intended to remind the viewer of the beauty, permanence, and superiority of Christianity and its promise of everlasting life over the ephemeral nature of even the most magnificent antiquities of the man-made world. When the painting was in the Massarenti collection in Rome, more than one hundred years ago, it was attributed to Giulio Romano, a Roman-born painter and architect who was one of the most gifted students of Raphael and who was celebrated for combining devotional motifs with creative references to ancient Roman buildings. Walters adopted Massarenti’s attribution and listed the painting as by Romano in his 1909 catalogue. Berenson, however, disagreed with this attribution and identified Bedolo, a relatively unknown painter from Parma who was a follower of Parmigiano and Correggio, as its author. Based on Berenson’s advice, Walters’s catalogues of 1915 and 1922 reattributed the painting to Bedolo. In 1976, Federico Zeri, one of the most highly regarded connoisseurs of Italian paintings during the second half of the twentieth century, published a comprehensive study of the Italian paintings in the Walters Art Gallery, in which he concluded that the painting was not by Bedolo, as Berenson had suggested, but by Raffaello Dal Colle, who worked as an assistant to Giulio Romano in Raphael’s workshop. Zeri’s attribution was accepted by the Walters Art Museum until 1997, when the attribution was again changed, this time to “Giulio Romano and workshop.” This attribution lasted for only eight years until 2005, when it was changed again by the curators of the museum to Giulio Romano. Thus, the various attributions given to this painting over the course of a century made a full 360-degree cycle beginning and ending with Giulio Romano, the artist to whom Massarenti originally had attributed the painting.40

It is also salutary to compare the present vitality of the attributions made by Berenson with regard to the thirty-six paintings he sold to Walters with the present vitality of the attributions that accompanied the paintings sold by a variety of other art dealers to Walters between 1900 and 1931 (see appendix B, list 3). During this time frame, Walters acquired sixty-four individual Italian paintings from dealers other than Berenson. Among the sixty-four paintings, the original attributions of six are unknown. Among the remaining fifty-six paintings, the original attributions have withstood the test of time in nineteen cases.41 Stated otherwise, 33 percent of the attributions given to the Italian paintings sold to Walters by dealers other than Berenson have remained unchanged. This rate of success matched Berenson’s. Thus, regardless of whether the Italian paintings were acquired by Walters from Berenson or other dealers, their attributions have remained intact only 33 percent of the time.

Without diminishing the difficulty of assigning attributions to Italian Renaissance paintings, the question remains whether Berenson’s advice satisfied Walters’s expectations established at that time. Berenson styled himself as the world’s greatest connoisseur of Italian Renaissance painting. He represented that his attributions were more dependable than those of others and tantamount to guarantees of authenticity. Moreover, he represented that the paintings he was selling to Walters were not merely typical of the work of the artists but among the best work that the artists ever painted. He obligated himself contractually to sell paintings to Walters that would improve “the overall quality of the collection.” The paintings that Berenson offered to Walters were predicated on these express and implied understandings. The paintings were not acquired by Walters for his own aesthetic pleasure—he rarely looked at them. They were acquired for the education and enjoyment of future generations who would visit his museum. Thus, there was a legitimate expectation that the quality of the paintings Berenson sold to Walters as well as their attributions would maintain their currency for the indefinite future. In this light, one can only imagine how disappointed Walters would have been if he had known that most of the paintings he acquired from Berenson suffered from the same virus of misattributions as the Massarenti paintings they were intended to replace and that Berenson’s attributions were no more reliable than those of other dealers.

In retrospect, Berenson’s major contribution to Walters’s collection of Italian paintings was in a manner neither sought nor appreciated by Walters at that time. It was clearly not in the quality of the paintings he sold to Walters, for there were surprisingly few great paintings among them. Nor was it in the scholarly, illustrated catalogue that he promised to write for Walters but never finished. Rather, as we shall see, it was in Berenson’s studious criticism, which peeled away the stale and pretentious attributions Walters had adopted from Massarenti and which thereby gave the Walters collection of Italian paintings a fresh start. What Berenson contributed to the Walters collection, paradoxically, was not primarily by addition but by a refined process of subtraction.