The year 1922 was, for Walters, a year of transition. Within a period of seven weeks, a number of interrelated events occurred that changed Walters’s life and the future of his gallery. On February 18, 1922, Faris Pitt, the gallery’s sole curator and de facto director, died, and Walters decided not to replace him. Four days later, on February 22, Walters, as if engaged in some final act of catharsis, disposed of fifty-three Italian paintings that once were among his most prized possessions, including paintings that had been attributed to Correggio, Veronese, Tintoretto, Domenichino, Reni, and Caravaggio. Then, on April 11, 1922, Walters, at the age of seventy-three, married Sadie Jones, the widow of his old friend Pembroke Jones. On the very same day, Walters executed his last will and testament bequeathing his collection and gallery to the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore “for the benefit of the public.”1 That same year, Walters made some minor, housekeeping revisions to the catalogue that previously had been orchestrated by Berenson, adding seven Italian paintings that had been acquired since 1915. They would be the last changes to the catalogue of paintings that he would oversee.2 What tied these events together was not just their temporal proximity but Walters’s belief that he had essentially fulfilled his obligations to his gallery in Baltimore, and it was time to move on.

All fifty-three of the Italian paintings that were disposed of by Walters had been on display when he opened his gallery in 1909. Following Berenson’s evaluation of the collection in 1914, they had been removed from display, put in storage in the basement of the gallery and placed by Berenson on his list of “Pictures to be removed from Mr. Walters’ collection.” Berenson’s list, however, contained the names of 119 paintings, not just 53, and it is not known why Walters selected some of the listed paintings for disposition but elected to retain the others. Also unknown are most of the surrounding circumstances of the disposition. There are no extant documents that disclose the means by which Walters disposed of these paintings, whether they were sold or given away, who were the recipients and who owns them now. Nor will we likely ever know whether there were any very valuable works of art among them. The question of whether, as seems unlikely, Caravaggio painted Walters’s picture of Jesus Crowned with Thorns (see fig. 16)—which appears from its vintage photograph to reflect the dramatic contrast of light and darkness that characterized Caravaggio’s paintings—or whether the painting was a fine example of the work of his followers, is simply unanswerable. We can only speculate as to whether Berenson’s criticism of Walters’s paintings might have been just as mistaken in certain cases as the exaggerated praise that colored his description of many the paintings he sold to Walters.

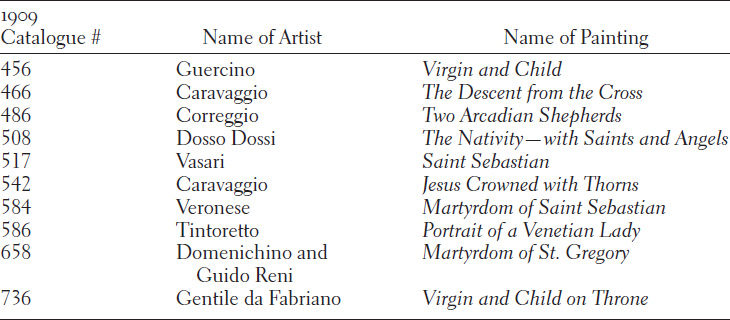

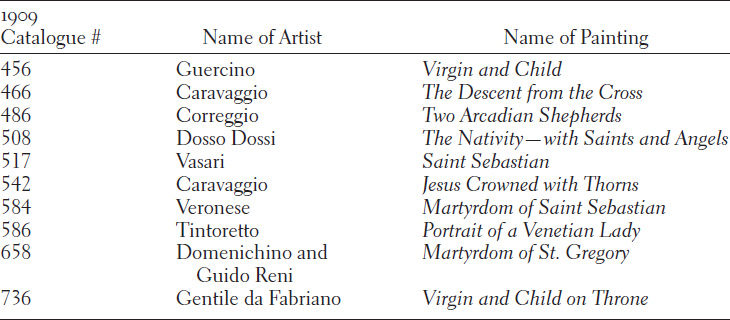

TABLE 2

Partial List of Paintings Disposed of by Walters in 1922

Among the paintings that Walters disposed of in 1922 were those listed in table 2. One can imagine Walters’s pain in parting with paintings by artists of this stature, unless he secretly doubted their attributions in the first place.

The event in 1922 that had the most immediate impact on the museum was the death of the gallery’s curator, Faris C. Pitt. Because Walters rarely traveled from New York to Baltimore to visit his gallery, Pitt had been instrumental in managing the day-to-day operations of the museum. Walters’s decision not to replace him constituted a watershed moment in the early history of the gallery. It signaled Walters’s intent to begin using the gallery more as a distant outpost to store unopened crates of art that were being left to the City of Baltimore than a place to look at art and enjoy its visual and intellectual pleasures.

The impact of Walters’s decision was made graphically clear several months later. In January 1923, Walters received a request from the American Association of Museums to provide certain information about his gallery and to permit a group to visit it. In turning down this request, Walters wrote, “I presume you know my Galleries in Baltimore are in no sense a public museum, and I have no curator or director. At one time a former friend of mine [Pitt] was in a certain sense in charge, but he died and I have never replaced him, but attend to all the questions myself personally.”3

Without the attention of any curator or director, the Walters Art Gallery became a dark and desolate place. It was managed by a Building Superintendent, James C. Anderson, who was granted little discretion. Anderson’s primary duties were to receive, document and store the shipments of art that continued to arrive at the gallery each week, to supervise the gallery’s upkeep and maintenance and to guard the gallery like a fortress and prevent any unauthorized person from entering. Although Walters, consistent with the precedent established by his father, allowed members of the public to visit the gallery two days each week during the months of January through April, Walters kept the gallery off-limits to the general public during the rest of the year. He covered the skylights and windows of the museum, causing the gallery to remain dark and, as he reminded Anderson, “in no condition for the public to see.”4

Anyone wanting to visit the gallery to see the art had to obtain written permission directly from Walters. Walters routinely discouraged such requests. On the rare occasions when Walters permitted a visit, he would provide the guest with a card signed personally by him which authorized the guest’s admission for a specific date and send a telegram to Anderson instructing him to permit the visitor to enter the museum “upon presentation of [his/her] card.” Walters’s instructions to Anderson usually concluded with the strict reminder to “be governed accordingly.”5 Walters also gave Anderson strict instructions regarding when, if ever, to permit a visitor to leave the gallery and then return. He wrote: “If anyone presents a card from me and should want to leave the gallery for lunch and return again on the same day, you would be justified in letting them do it. You would not be justified in letting them come back on another day on the same card; they would have to get another card of admission.”6 In this manner, Walters firmly restricted the public’s access to his gallery.

Even if a visitor were acquainted with Walters, gaining access to his gallery was not an easy or pleasant experience. On one occasion, H. G. Kelekian, a relative of one of Walters’s principal dealers, requested the opportunity to visit the gallery. Walters responded, “I am sorry the Galley is all covered up and all disarranged . . . all the skylights are covered with heavy canvas.” Walters concluded his letter by informing Kelekian that he would be admitted by his superintendent, Mr. Anderson, but that “you will not be able to see much.”7 In response to a request from his stepson, Pembroke Jones, Jr., to visit the gallery, Walters reminded him that, “between about the 15th of May and the 1st of November, covers are over pretty much everything, including the skylights, so that in the summertime very little can be seen.”8

One of the few persons who recorded an impression of the Walters Gallery was Walters’s dealer, Arnold Seligman, who was invited in 1924 by Walters to meet him at his gallery. Upon entering the main building, Seligman found a “vast and gloomy hall” filled with over two hundred unopened cases piled on top of one another and objects that were, in his judgment, either copies or out-and-out fakes. It looked more like a “wilderness” than a well-organized gallery of art, and, as he later recalled, the haphazard nature of Walters’s gallery placed him in “a state of shock.” In an effort to explain the reason for the chaotic condition of the collection, Walters informed Seligman that “he had no time to arrange or catalogue it.”9

Walters at that time also acknowledged that he simply did not have the interest or resources to unpack the crates of art that continued to flow into his gallery. When Seligman inquired about a work of art that he had sold to Walters the previous year, Walters replied that it had never been unpacked. And then, referring to all of the unopened crates of art, Walters added: “I probably won’t live to see them all opened . . . but you can imagine the surprise of those who will unpack them after I am gone.”10

In light of its condition, it is no surprise that Walters, after 1922, made little effort to publicize his gallery. The American Art Annual, which served during that era as the central source of information about American museums, contained only the address of the Walters Art Gallery and the few dates when it was opened to the public. When Walters was asked by that magazine “to provide more information about the contents of your great Gallery,” he declined.11 In June 1925, the magazine Art and Archeology devoted its entire issue to “Baltimore as an Art Center.”12 The issue contained separate articles about the recently established Baltimore Museum of Art, the Maryland Institute of Art, the Archeological Museum at the Johns Hopkins University, and the Maryland Historical Museum. The Walters Art Gallery, however, was not even mentioned in the magazine’s table of contents. The only reference to the gallery was buried in the section on private art collections.

Walters not only avoided publicity but ceased using the gallery for private, social affairs. Unlike the grand parties hosted years earlier by his father to proudly show off his collection of French paintings, Henry Walters hosted no social events in Baltimore to show off his Italian paintings to his circle of wealthy friends and collectors living in New York or to his associates at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The daily log of the building superintendent, which documented the names of visitors, did not record any visits by any members of the Metropolitan’s Board.13 Walters rarely invited anyone to his gallery, and it appears likely that he never even brought his wife from New York to Baltimore to visit it.14 Perhaps embarrassed by what had happened to his once-famous collection of Italian paintings, Walters began to act as if he would rather hide his museum than show it. As a result, the Walters Art Gallery during the remainder of Walters’s life gradually disappeared from the consciousness of art lovers in Baltimore and elsewhere.