The Most Famous Cities of the Maya: The History of Chichén Itzá, Tikal, Mayapán, and Uxmal

By Jesse Harasta and Charles River Editors

Picture of El Castillo in Chichén Itzá, taken by Daniel Schwen

About Charles River Editors

Charles River Editors is a boutique digital publishing company, specializing in bringing history back to life with educational and engaging books on a wide range of topics. Keep up to date with our new and free offerings with this 5 second sign up on our weekly mailing list, and visit Our Kindle Author Page to see other recently published Kindle titles.

We make these books for you and always want to know our readers’ opinions, so we encourage you to leave reviews and look forward to publishing new and exciting titles each week.

Introduction

Chichén Itzá’s Great Ball Court. Photo by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen

Chichén Itzá

Many ancient civilizations have influenced and inspired people in the 21st century, like the Greeks and the Romans, but of all the world’s civilizations, none have intrigued people more than the Mayans, whose culture, astronomy, language, and mysterious disappearance all continue to captivate people. At the heart of the fascination is the most visited and the most spectacular of Late Classic Maya cities: Chichén Itzá.

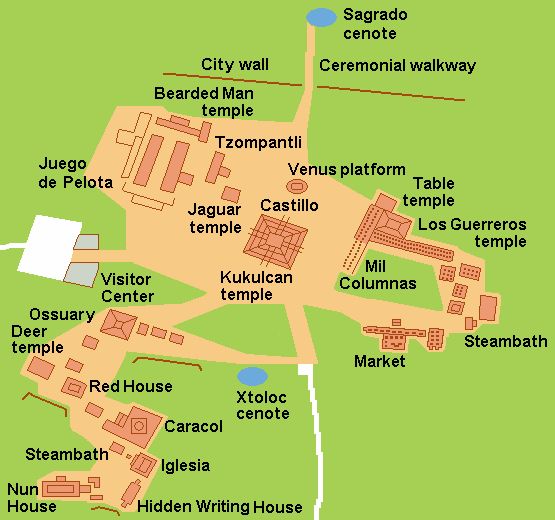

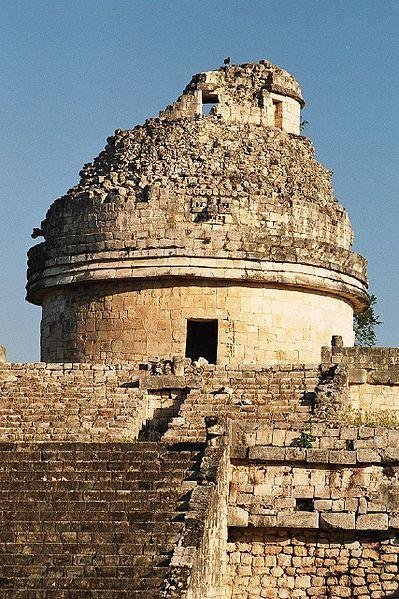

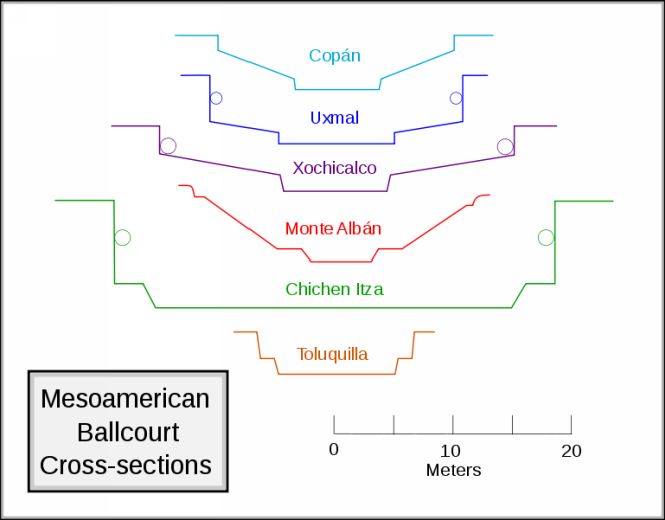

Chichén Itzá was inhabited for hundreds of years and was a very influential center in the later years of Maya civilization. At its height, Chichén Itzá may have had over 30,000 inhabitants, and with a spectacular pyramid, enormous ball court, observatory and several temples, the builders of this city exceeded even those at Uxmal in developing the use of columns and exterior relief decoration. Of particular interest at Chichén Itzá is the sacred cenote, a sinkhole was a focus for Maya rituals around water. Because adequate supplies of water, which rarely collected on the surface of the limestone based Yucatan, were essential for adequate agricultural production, the Maya here considered it of primary importance. Underwater archaeology carried out in the cenote at Chichén Itzá revealed that offerings to the Maya rain deity Chaac (which may have included people) were tossed into the sinkhole.

Although Chichén Itzá was around for hundreds of years, it had a relatively short period of dominance in the region, lasting from about 800-950 CE Today, tourists are taken by guides to a building called the Nunnery for no good reason other than the small rooms reminded the Spaniards of a nunnery back home. Similarly the great pyramid at Chichén Itzá is designated El Castillo (“The Castle”), which it almost certainly was not, while the observatory is called El Caracol (“The Snail”) for its spiral staircase. Of course, the actual names for these places were lost as the great Maya cities began to lose their populations, one by one. Chichén Itzá was partially abandoned in 948, and the culture of the Maya survived in a disorganized way until it was revived at Mayapán around 1200. Why Maya cities were abandoned and left to be overgrown by the jungle is a puzzle that intrigues people around the world today, especially those who have a penchant for speculating on lost civilizations.

Mayapán

A panoramic view of Mayapán

Early Mayapán was closely connected to the overshadowing power of the region at the time: the mighty trading city of Chichén Itzá. Mayapán emerged first as a minor settlement in the orbit of Chichén, but it slowly came to replace it after the larger city's trade connections with the Toltecs of Tula crumbled and it suffered a staggering defeat by Mayapán's armies. The building styles and art in their city show both admiring references to the great Chichén Itzá as well as an attempt to position Mayapán as a more orthodox heir of Maya tradition. At the same time, they emulated many features and could not escape the tremendous influences - especially in religion - of Chichén. This is seen in the fact that many of the most important buildings in the new city appear to be small-scale reproductions of ones in Chichén.

Due in part to the fact that it has long been overshadowed by Chichén Itzá, a lot excavation and scholarly research on the site has only come about in recent decades, and even though there is still plenty of work to do, a lot of information about life in Mayapán has been unearthed. At its height, Mayapán may have boasted a population of over 15,000, and archaeologists have had their hands full trying to discover and restore the several thousand buildings both inside Mayapán’s walls and outside them as well.

Tikal

Tikal’s main plaza during the Winter Solstice. Picture by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen.

The Maya maintained power in the Yucatan for over a thousand years, and at the height of its “Classical era” (3rd-9th centuries CE), the city of Tikal was one of the power centers of the empire. Archaeologists believe Tikal had been built as early as the 5th or 4th century BC, and eventually it became a political, economic and military capital that was an important part of a far-flung network across Mesoamerica, despite the fact it was seemingly conquered by Teotihuacan in the 4th century CE. It seems the foreign rulers came to assimilate Mayan culture, thus ensuring Tikal would continue to be a power base, and as a result, the city would not be abandoned until about the 10th century CE.

As one of the Ancient Maya’s most important sites, construction at Tikal was impressive, and even though it was apparently conquered, the city’s records were unusually well preserved. This includes a list of the city’s dynastic rulers, as well as the tombs and monuments dedicated to them. Thanks to this preservation, Tikal offers researchers their best look at the Ancient Maya and has gone a long way toward helping scholars understand Mayan history.

Uxmal

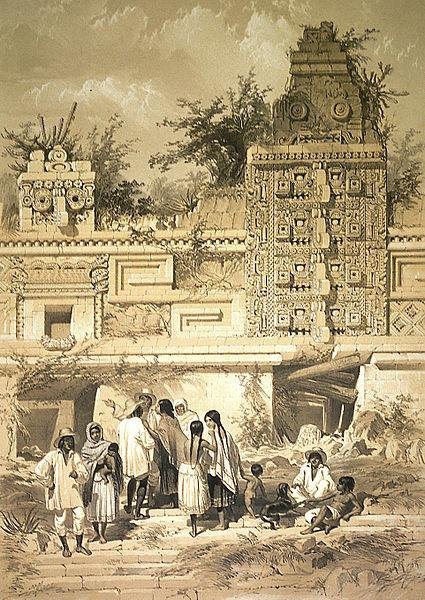

Palimp Sesto’s picture of the ruins of Uxmal

During the Maya’s Classical era, the city of Uxmal was one of its most noteworthy places. While it was not as powerful as cities like Tikal, Uxmal was apparently at the forefront of Mayan culture, particularly when it came to architecture. However, while Uxmal used high ground to display its prominence, and the ruins are still among the most popular places for tourists in the region, the site is still shrouded in mystery. Even as scholars continue to work on the site to further interpret it, it’s still unclear when exactly Uxmal was founded, how many people called it home, and when it was abandoned, despite the existence of Mayan chronicles and oral legends.

What is apparent, however, is the skills of Uxmal’s artisans, whether through constructing structures like the five-level Pyramid of Magicians and the expansive Governor’s Palace or adorning the structures with precisely detailed art and sculptures. In fact, the craftsmanship can be credited with helping to preserve Uxmal itself.

The Most Famous Cities of the Maya: The History of Chichén Itzá, Tikal, Mayapán, and Uxmal covers the history of each city, as well as the speculation and debate over the city’s buildings. Along with pictures and a bibliography, you will learn about the Mayan cities like never before.

The Most Famous Cities of the Maya: The History of Chichén Itzá, Tikal, Mayapán, and Uxmal

A Note on the Periods of Mayan History

A Note on Pronunciations and Names

Chapter 3: The Entrada, Teotihuacán, and the Second Dynasty

Chapter 4: The Great Hiatus and the Third Dynasty

Chapter 5: Jasaw Chan K'awiil I and the Fourth Dynasty

Chapter 1: Description of the Site

Chapter 2: Daily Life in Uxmal

Chapter 3: Origins of the City

Chapter 5: Chichén Itzá and the Eclipse of Uxmal

Chapter 6: Revolution and The League of Mayapán

Chapter 7: The Abandonment and Rediscovery of Uxmal

Timeline of Events in the Yucatan Postclassic Period

Chapter 1: Origins of Chichén Itzá

Chapter 2: The Era of Chichén Itzá's Glory

Chapter 3: Description of the Site of Chichen Itzá

Chapter 4: The Decline of Chichén Itzá and the Rise of Mayapán

Chapter 5: The Layout of Mayapán

Chapter 8: The Centrality of Religion in Mayapán

Chapter 10: The Rediscovery of the Cities’ Ruins

Free Books by Charles River Editors

Discounted Books by Charles River Editors

Tikal

A Note on the Periods of Mayan History

This book follows the traditional system of dividing Mayan history into "periods." Much like European history is divided between the Ancient and Medieval Periods based on whether the Roman Empire had fallen or not, there is a great dividing line in Mayan history called the Classic or Postclassic period.

The apogee of Mayan culture and influence was in the period known to Mesoamerican scholars as the "Classical" period. Ranging from to the 3rd-9th centuries, during this time the region was dominated by two great powers, Tikal and Calakmul, located far to the south of the Yucatán in the northern Highlands. To the west, central Mexico was dominated by the cities of Teotihuacan, Cholula and Monte Albán. This was a period of relative stability, though it probably didn't feel that way as the ruling dynasties of Tikal and Calakmul vied for power and fought numerous proxy wars through their many client states . This period is comparable to the great "cold war" between Athens and Sparta in ancient Greece.

Much like the Roman Empire did not collapse in every area at the same time, the change from the Classic to Postclassic occurred in different places differentially. The Classic Mayan world included a constellation of city-states arranged in great, rival, shifting confederacies. These cities, including the famous centers of Tikal, Palenque, Caracol, and Calakmul, were ruled by kings who were considered semi-divine and were widely commemorated in stone monuments. Eventually, however, the great cities of the Classic Period collapsed, one by one. Far from vanishing, Mayan culture persisted, especially in rural areas, and over time, a new series of cities emerged. While the greatest Classic cities were based in the Highlands of modern Mexico and Guatemala, the Postclassic cities, including Chichén Itzá and Mayapán, emerged in the north in the Yucatan peninsula. Generally speaking, the Postclassic period lasted from the 900s until the arrival of the Spanish in the 1500s.

A Note on Pronunciations and Names

While the Ancient Maya certainly had their own system of writing, the Spanish Conquest ultimately eradicated knowledge of it, so the Mayan languages have been written for almost 500 years using Latin characters adopted from Spanish by missionary priests. Nonetheless, some of the sounds in the Mayan languages do not correspond directly to sounds in English or Spanish, so some guidance is needed for proper pronunciation.

"X" is pronounced as "SH" so the Mayan city of Yaxchilan is pronounced "Ya-sh-i-laan"

"J" is pronounced as a hard "H" so the Mayan name Jasaw is pronounced "Ha-saw"

"Z" is pronounced like an English "S"

"HU" and "UH" are pronounced like a "W" so the Mexican name Teotihuacán is pronounced "Teo-ti-wa-caan"

The Mayan orthography also uses an apostrophe ( ' ) to mark a sound that does not appear in most European languages called a glottal stop. This represents a stoppage of air in the throat, a bit like the swallowing of the "TT" in "LITTLE" when pronounced by a Cockney Englishman (which would be written in Mayan orthography as: "li'le"). The glotttal stop is considered to be a consonant.

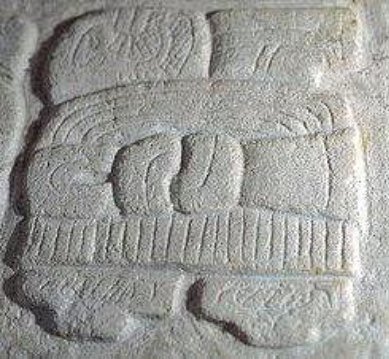

While the word "Tikal" is Mayan, it is not the name that the Ancient Maya gave to the city when they lived in it. The modern name comes from the Mayan "Ti' ak'al" or "At the Waterhole," a name given by Mayan hunters who traveled through the area and stopped at water reservoirs in the ancient city. The exact name has been lost, but it appears that it was written using a glyph that represented a topknot hair style. Hence, it was probably given the same name, "Mutal." In more formal occasions, it was likely called "Yax Mutal" ("First Topknot"). As a result, some modern archaeologists use the name "Mutal" for talking about the city, but to avoid confusion, this book will stick with the more common name Tikal throughout.[1]

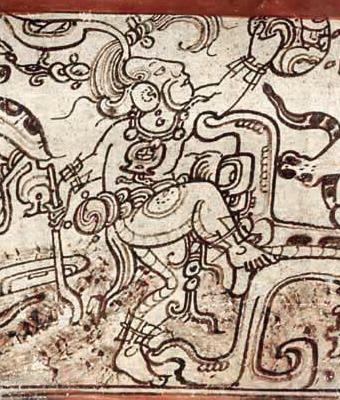

The emblem glyph representing the name Mutal.

As scholars have increasingly learned to read the sophisticated writing system left behind by the Maya, they have gained a more subtle understanding of their naming practices. Generally speaking, only the names of kings and queens, as well as a few other individuals, are named in the records, and early archaeologists used names that described the name glyphs, with names like "Stormy Sky," "Curl Snout" or "Great Jaguar Paw." Today it’s possible to reconstruct the actual sounds of names like Siyaj Chan K'awiil II , Yax Nuun Ayiin I, or Chak Tok Ich'aak I, but these names are quite long and contain many repetitive elements (much like the continual repetition of the names George and Edward among English kings). This can quickly get confusing for readers, so when this book refers to a king, the Mayan pronunciation will come first, followed by the English glyph names. Subsequent references to the kings will then use the English glyph names to help readers follow along. That said, there are a few exceptions to this due to the growing prominence of the Mayan names for these individuals, most importantly the great king Jasaw Chan K'awiil I.

A jade statue depicting Jasaw Chan K'awiil I

The names of the early kings after Yax Ehb' Xook are largely unimportant to history because of a lack of definitive information about their lives and deeds. One exception is from 317 AD, when there was a break in the male line and the city was ruled by its first recorded woman: queen Lady Une' B'alam ("Baby Jaguar"). This set an important precedent for later claims of succession in the city when usurpers of various shades would look to their own matrilineal ancestors as justification for their place on the throne[2].

Chapter 1: Early Tikal

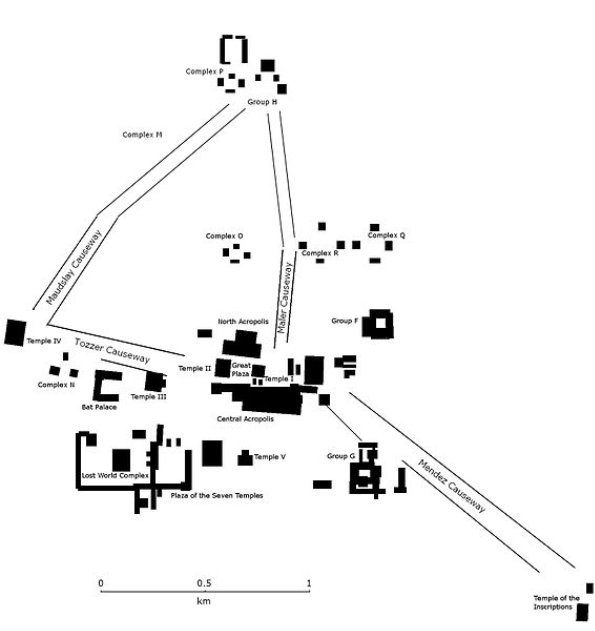

A layout of Tikal

Given how old the city of Tikal is, it’s no surprise that the actual origins of the city and the date of its first settlement have been lost to time. In fact, the city was so old that it seems to have predated the Maya’s invention of writing, and it was not recorded by later generations, likely because they were more concerned with the founding of the First Dynasty. Thus, the only information historians can glean regarding dates comes from archaeological excavations at the tomb-temple complex of the North Acropolis. The North Acropolis is not only ancient but was sacred and central to the political, religious and social lives of communities for centuries, similar to Westminster Abbey or the Acropolis in Ancient Athens. The Ancient Mayans who lived in Tikal and were unaware of the city’s origins itself viewed the North Acropolis not only as ancient but as a symbol of their national identity and sense of self. Thus far, archaeologists have determined that the oldest date for a building at the North Acropolis is about 350 BC, though traces of settlement likely went back centuries before that.[3] By the time the city fell over a millennium later, it had become a complex jumble of construction, a "labyrinth of elevated platforms and walls.[4]"

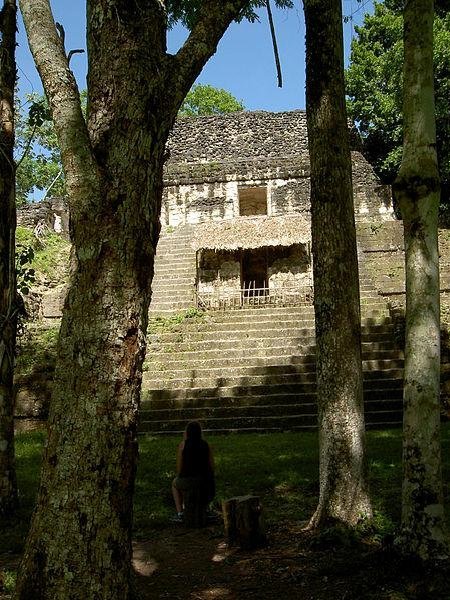

Pictures of the ruins of the North Acropolis

The city of Tikal was founded in a favorable position along the southern edge of a north-south mountain range that divides the Peten region. Around Tikal, settlers enjoyed a number of varied environments. From the swampy bottomlands called “bajos”, they collected crocodiles, frogs, water lilies and logwood trees. Along the hills, they raised corn and other crops and navigated the river valleys as trade routes, bringing up useful items like shells, seaweed and stingray spines from the coast of what is today Belize[5]. The city that they founded would eventually become the longest-inhabited Classical center, with an estimated 39 recorded rulers.

It appears that the early inhabitants of Tikal worshiped "spirit forces personified by [a] giant birdlike stucco mask.[6]" These masks have been found in the temples of the North Acropolis, and archaeologists have uncovered similar monuments in other contemporary Lowland Pre-Classic cities like El Mirador, Nakbé, Cerros and Uaxactun. There is no consensus on exactly what god or goddess was represented by the masks, but there are two potential candidates based on documents that survived the Spanish and records kept by the Spanish themselves. In the Highland mythological text Popoh Vuh, there is one candidate called "Vucub Caquix," a lord of twilight who dominated the earth before he was displaced by the hero twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque. Another possibility is the creator god Itzamna, who was recorded as being revered by the Maya of the Yucatec peninsula by the Franciscan priest Diego de Landa. The interpretation of the North Acropolis monuments and the surrounding temples varies greatly depending on whether this figure is a dark lord of the era before humans or a beloved creator. Of course, it is also possible that this deity, who was worshiped in a period of great antiquity, was displaced by the emergence of later gods like Tlaloc or Quetzalcoatl. Regardless, there are no known written accounts of this deity’s name.

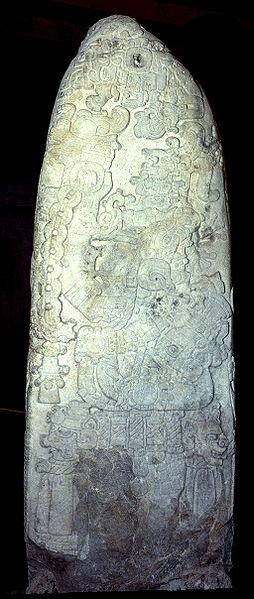

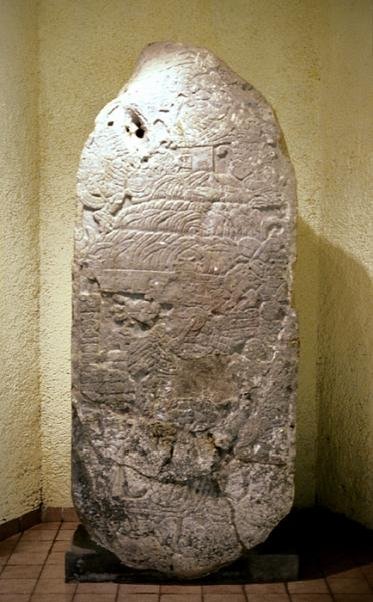

Once it emerged as a political unit worthy of mention, early Tikal was dominated by two sister-cities located roughly 20 miles (32 km) to the northwest. These were El Mirador and Nakbé, cities which adopted an elaborate Mesoamerican urban tradition from groups like the Olmecs further north. This included stone buildings, temples on top of pyramids, the ball game,[7] and the construction of stone monuments. The most important of these monuments to emerge out of the El Mirador/Nakbé tradition were "stelae" (the plural of "stela"), which were large stone slabs covered in elaborate carvings commemorating important events. Similar to royal inscriptions in ancient Egypt, kings in Tikal would erect these stelae to commemorate great victories, important calendric events (the equivalent of decades and centenaries), investitures of power, and deaths. Since little of the early Mayan writing has survived the ravages of time and the Spanish Conquest, these stelae are often important sources of information about what the kings wanted observers to know about themselves[8].

Picture of a stela in Tikal

The ballgame court at Tikal. Picture by Simon Burchell.

Chapter 2: The First Dynasty

By 300 AD, the El Mirador/Nakbé political entity was crumbling, so its various vassal states were able to act independently, including not only Tikal but other major players of later history like Uaxactun and Calakmul. In this vacuum of power emerged what anthropologists call "chiefdoms," relatively simple units ruled by a single leader (the chief) and his personal bodyguard who is able to extract tribute from surrounding farmers. Chiefs might in turn send tribute up the line to a larger, paramount chief who controlled a number of lesser chiefdoms[9].

It was out of this relatively chaotic and occasionally brutal situation that Tikal's leadership began to consolidate local power, and eventually the rulers established a system to transfer power from one generation to the next. They also created basic bureaucratic institutions, such as a priesthood, which gave further continuity and regularity to government. During this process, they undoubtedly looked to the examples of El Mirador and Nakbé, as well as other neighboring cities. In time, what emerged was the creation of the First Dynasty.

The early information about the First Dynasty is largely unavailable because much of it was destroyed via the elimination of the city's early monuments in 378 AD, but even if they had survived, the records would have been spotty because of the lack of sophistication in Mayan writing at the time. It would be some time before the people of Tikal themselves were involved in perfecting writing; in fact, contemporary records were only kept starting around 292 AD, so everything that scholars can piece together about the earlier eras of the First Dynasty have come from what was written by subsequent generations of Tikal’s residents after the fact.[10]

As a result, scholars’ estimates of the dates of the reigns of the early monarchs are based upon a technique called average reign length estimates. Simon Martin, a historian of the region, compiled all of the known start and end dates for the reigns of Mayan kings and queens and created an average of 22.5 years. He was then able to put them onto undated lists of kings, such as those available for early Tikal[11]. While this system obviously does not always (or even most of the time) provide the correct date, it offers up the best technique for dating events like the founding of the First Dynasty.

At the same time, knowledge of those early days has improved over the last few decades as historians unearth new information about the First Dynasty. For example, scholars long thought that Great Jaguar Paw, the last ruler of the dynasty, was the 9th in his line, but recent findings have uncovered the names of four more early kings. When added to the average reign length technique, this pushes back the reign of Yax Ehb' Xook (First Step Shark) to roughly 90 AD and opens up the possibility that his remains are those found in a splendid, sumptuous tomb called Burial 85 at the North Acropolis[12].

What is clear is that royal life in early Tikal centered around the Great Plaza, a broad paved area between the North Acropolis temple-tombs and the Central Acropolis, a complex structure that included administrative facilities, courts of law, and administrative areas. It was in splendor here that the First Dynasty constructed their empire. Other elite families tended to have their own homes scattered around the neighboring hills and farms, where they could control the local population[13].

Royal residences in Tikal. Picture by Dennis Jarvis.

Temple I with the North Acropolis to the left and Center Acropolis to the right.

One definitive element of the political life of the First Dynasty was the city's conflict with its primary political rival, the nearby city of Uaxactun. In many ways, Uaxactun remains in the record as a ghostly twin, mostly because its eventual conquest by Tikal meant that its early history was erased and that it remained in Tikal's shadow after that. However, it seems that early Uaxactun was nearly equal in power, making the two legitimate rivals. Like Tikal, Uaxactun emerged out of the chaos of the collapse of the old Nakbé and El Mirador power structure, but the eventual conquest of Uaxactun by the Second Dynasty after the Teotihuacano Entrada would solidify the city of Tikal as the dominant power in the region[14].

The last king of the First Dynasty was one of the most important. Chak Tok Ich'aak I, whose name is written as either Great Burning Paw or (more commonly) Great Jaguar Paw, came to the throne around roughly 360 AD, and it was during his reign that the city began to look outward in a much greater way than before. Much of this outward looking perspective involved the importation of goods and ideas from Central Mexico, specifically Teotihuacán; trade had existed for some time, but it reached new levels of sophistication during this period, especially involving high quality ceramics. As discussed further below, Great Jaguar Paw may have written his own death warrant, because it seems that the Teotihuacano army traveled along these same trade routes to come kill him. Another direct impact of this contact was the creation of the Lost World Complex[15].

Perhaps the most important construction during the rule of the First Dynasty was a complex of temples and support buildings poetically called the Mundo Perdido (or "Lost World"). Located at the western edge of the city center, it was the largest temple complex in the Preclassical city, dominated by a large four-sided pyramid topped with three temples, some of which may have been used as solar observatories to chart solstices and equinoxes. The architectural impact of the Mexican contact on the Lost World complex can be seen as early as 250 AD, long before Great Jaguar Paw's trade contacts[16].

One of the more important elements of the Lost World's architectural style is that it was the first area of Tikal to utilize a style called "Talud-Tablero." Unlike an Egyptian pyramid with four smooth sides, Mesoamerican pyramids were built like layer cakes or steps, with ever-smaller square blocks placed on top of one another. The Talud-Tablero style, also called the "slop and panel" style, is characterized by "pairs of taludes [sloped layers] and framed tableros [horizontal layers] that pass completely around a platform , and stairs flanked by balustrades that are capped with finial blocks (called remates)."[17] This is important because the style originated not amongst the Maya but in the mighty Central Mexican city of Teotihuacán. The interaction between Tikal and this distant imperial capital would come to dominate Tikal's political fortunes in the coming years, but the Lost World also shows the importance of Mexican styles at an early date in Tikal.

One of the Lost World pyramids. Picture by Dennis Jarvis.

A Lost World Temple. Picture by Mike Murga.

The roof of Temple III.

A step pyramid that’s part of “Complex Q” in Tikal.

Chapter 3: The Entrada, Teotihuacán, and the Second Dynasty

The destiny of Tikal was forever changed on January 31st, 378 AD when a massive army arrived at the city's gates. This event has become known by the Spanish name "Entrada" which means simply the "Entry," as in "the entry of Teotihuacán". While there is no clear record of the events due to the sheer scale of destruction that took place, it’s clear neither Tikal nor the Maya as a whole had ever seen anything like it because these foreign soldiers not only conquered but also subsequently ruled Tikal despite the fact they had come from Teotihuacán in Central Mexico, about 630 miles (1013 kilometers) away.[18] In short order, the Teotihuacanos dispatched the rulers of Tikal and installed their own people to rule, which ironically resulted in positioning Tikal as the largest and most important city in the Mayan lands. In the process, the Teotihuacanos not only changed Tikal but the direction of the Mayan civilization for centuries to come.

This conquest came about after trade contacts were established between the Mayan regions and what is today Central Mexico. These contacts went back centuries and included the transfer of not only goods but also ideas. An early example of this was the Talud-Tablero architecture found in the Lost World Complex of Tikal, and another clearly identifiable Mexican import found in early Tikal is green-hued obsidian, which can be clearly identified to sites in Mexico[19].

Early contacts between the Teotihuacanos and the Maya of Tikal and other cities began in the western Mayan city of Kaminaljuyu, which became wealthy acting as a go-between for the two peoples[20]. Tikal’s trade was primarily with the city of Teotihuacán, which was located in the Valley of Mexico near today's Mexico City. Thriving between 100-750 AD, this was one of the largest cities in the ancient world, with a population of at least 200,000. In comparison, when Tikal was at the height of its power in the 8th century, it had a population of around 60,000. Teotihuacán was a supremely well-planned and efficient city that was able to field massive armies and extend its power far beyond its home base to create a unified empire of the type that was never possible in the less fertile Mayan lands[21].

The ruins of Teotihuacán

There is a long-standing debate over exactly how much influence Teotihuacán (and Central Mexico in general) had over the development of the Mayan heartland. Mayanists have long been protective of their region and have tended to downplay Mexican influence and emphasize Mayan creativity. Before the decipherment of the Mayan script, they argued that Mayan leaders emulated styles from Teotihuacán but had no direct contact or rule[22]. In this interpretation, what happened in 378 was that Great Jaguar Paw, who had initiated trade with Teotihuacán, died and was replaced by his son, Lord Curl Snout, who formalized the trade relationship and began a period of stylistic emulation of their trade partners[23]. However, over time, archaeologists and historians have found evidence that the transfer of power in 378 from Great Jaguar Paw to Curl Snout - while it may have been inspired by earlier trade contacts - was anything but peaceful.

Today, there is a general consensus that Tikal was conquered by a mighty army, and the rumors of the conquering army’s march must have preceded it, as such a force could not move quickly without horses (which arrived with the Europeans). The first record historians have of its movements comes from a smaller city called El Perú, roughly 49 miles (78 kilometers) to the west of Tikal. El Perú fell on January 23rd, and the armies arrived at Tikal eight days later after traveling up the San Pedro Martir River.[24]

At the head of this army was a figure called Siyaj K'ak' ("Fire Born"), who appears to have been a general. The surviving writing says that Siyaj K'ak' was sent at the head of the army at the behest of a mysterious figure called "Spearthrower Owl." This name is not written out using Mayan script but is instead an image of an owl bearing an atlatl (a device for throwing spears). The owl may have been a symbol of a warrior god or caste in the city, but the name "Spearthrower Owl" appears more likely to be a title than the actual name of the person. Traditionally, Spearthrower Owl has been thought of as the ruler of Teotihuacán who sponsored the expedition, based on some monuments that appear to place the date of his ascension to a throne (which throne is not certain, but it's not Tikal’s) on May 4th, 374 and his death on June 10th, 439. The records also suggest he took a Mayan wife[25]. However, recently there has been a debate over whether the title actually refers to a god, because some murals found at Teotihuacán refer to a site called "Spearthrower Owl Hill", and these murals are roughly contemporaneous with the Entrada of 378. In this understanding, Spearthrower Owl is a martial god similar to the later Aztec god Huitzilopochtli. The archaeologists and historians will have to find further evidence (including a search for Spearthrower Owl Hill) before a more definitive statement on the subject can be made.[26]

Either way, when this army arrived, the Maya likely resisted, but Tikal had no walls, a defensive feature that would not appear in Mayan cities until centuries later. It also seems that the resistance didn’t do much harm to the armies of Teotihuacán, which quickly conquered other cities as well. Images found on pottery depict the arrival of the Mexican warriors and ambassadors and the death of Great Jaguar Paw on January 31st, 378. More direct evidence of conquest comes from Uaxactun, where a mural image depicts a submissive Maya and a dominant Teotihuacano from the time period[27]. It is useful to compare this image to the type of imagery found at the city of Chichén Itzá some 600 years later. There is a similar debate at Chichén about a possible invasion by a Central Mexican power (this time the Toltec Empire), but there is no record there of conquest and no images of Mayans dominated by Mexicans[28].

There is also archaeological evidence for a change in the nature of the Mexican-Mayan contact at this point as well. For example, Tikal became home to considerably more Teotihuacano objects after 378, especially lidded tripods coated in painted stucco. Even more notable is the fact that there was a systematic destruction of monuments from before 378, and the use of the broken stone as either fill for new construction projects or their exportation to other, less important cities. For a royal system whose legitimacy was founded upon a connection to the past (especially in the form of the tombs of the North Acropolis), the destruction of these past records indicate a major political break occurred on that year[29].

A stucco mask adorning a temple in the North Acropolis. Picture by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen.

It’s also known that during the same year, an army out of Tikal finally conquered Uaxactun and eliminated its ruling line. In its place, the brother of the lord of Tikal, a man named Lord Smoking Frog, was put on the throne and founded his own cadet dynasty that would rule in the shadow of Tikal[30]. The last date scholars have for the fall of a surrounding city was 381. The Teotihuacanos would put up their own dynasties at all of these sites, but it’s unclear what the relationship between Tikal and these other conquests was, or if there was an effective central coordination. If there was, it would eventually break down in the wars that would emerge a few generations later[31].

Regardless of whether Spearthrower Owl was a man or a god, he was not the titular ruler of Tikal for long, because the record suggests that his son, Yax Nuun Ayiin I (“Curl Snout”) took the throne on September 12, 379. This date marks the beginning of the Second Dynasty, and Curl Snout would reign for 25 years until his death on June 17, 404. When he came to the throne, Curl Snout was only a boy, and it appears that the general Siyaj held the reins of power as a regent over the city during Curl Snout's youth.

A stela at Tikal that depicts Curl Snout. Picture by H. Grobe.

While Curl Snout would not live to a ripe old age (if Spearthrower Owl was a man, he apparently outlived his son by 35 years), his reign was notable as the high watermark of Teotihucano imperialism in the region. This was when the monuments dating before 378 were destroyed, and the regime aimed to re-create the royal imagery of Central Mexico in its monuments and murals. This first generation of conquerors had no connections to the land they ruled and derived their legitimacy from their distant patron Spearthrower Owl, but Curl Snout did marry a wife with Mayan royal titles, so there was at least a nominal attempt to associate the Second Dynasty with the previous power structure.[32] It is believed that Curl Snout was buried in the magnificent Burial 10 in Temple 34, which was the first building to break out of the traditional front face of the North Acropolis (though others would follow in later generations)[33].

Upon Curl Snout's death, his heir was not yet considered an adult, so just as Siyaj K'ak' ruled as a regent during Curl Snout’s youth, another non-royal by the name of Siyaj Chan K'inich ("Sky Born Sun God") would rule from 406-411. After sitting under the thumb of the regent Siyaj Chan K'inich for five years, the new king, Siyaj Chan K'awiil II (Lord Stormy Sky), ascended to the throne of Tikal on November 26, 411. He would have a particularly long and productive reign before he died on February 3, 456 (45 years, twice the average).

A stela depicting Stormy Sky

The reign of Lord Stormy Sky was characterized by a re-emergence of Mayan imagery in royal propaganda and an emphasis on the continuity of the Second Dynasty with the royalty of the First Dynasty through his mother's line. This was a distinct break with the imagery of his father's reign, which depicted the Maya only as subservient and was dominated by imported Mexican symbols. In fact, there was a conscious use of archaisms in the art; for instance, artisans basically re-created a 150 year old stela with only slightly different wording. The words of other monuments also placed an emphasis on the precedence of royal blood being transferred via the female line in the case of the 4th century queen, Lady Une' B'alam[34]. Furthermore, emphasis was taken off of ritual at the consciously Mexican Lost World complex and returned to the thoroughly Mayan North Acropolis. Other evidence of the change is that the royal regalia depicted in the stelae returned to the traditional Maya form created in the 3rd century, and this would remain basically unchanged until the collapse of the city. Even the king's name - possibly a regnal name[35] - was a reference to an earlier king, Stormy Sky, who ascended to the throne around 307 AD[36].

What inspired the triumphant Teotihuacanos to "nativize" and emphasize the Mayan culture and dynastic tradition that they had previously scorned? The written and archaeological records are mostly silent on this, but it’s possible to make comparisons to similar cases around the world where an invading warrior elite conquers a wide swath of territory. Examples would include the French Normans in Britain, the Hellenic Greeks in much of their post-Alexander empire, the Turkic Safavid Dynasty in Persia, and the Manchus in China. In all of these cases, the elite established not only a dominant dynasty but also installed smaller lines throughout the new territory, and in the process, they spread themselves quite thin. The conquering Teotihuacanos must have needed to learn to speak the local language to communicate not only with the peasantry but with Tikal’s local administrators and bureaucrats, and over time, subsequent generations of the elite who grew up communicating with the locals likely had no direct experience or emotional ties to their native homeland. Moreover, they may have resented having to send tribute back “home” and may have further assimilated in efforts to legitimize themselves to avoid local uprisings.

One long-term effect of this period of strength, during which Tikal-Teotihuacán influence spread throughout the Mayan Lowlands, was a reinforcement of the dynastic system. In fact, while Tikal had been an early pioneer in this form of governance, it was only with the influence of Teotihuacán's Mexican tradition that it reached its peak. Tikal’s dominance also helped spread the cult of the rain god Tlaloc (who became known by the Mayan name Chaak) throughout the Mayan lands, where he displaced the earlier bird-faced deity as the principal god[37]. There has been some argument that this dynastic and religious tradition fostered opposition amongst more conservative Mayan groups and helped garner support for Tikal's enemies in traditionalist Calakmul, which claimed royal descent from El Mirador.

A Classical era depiction of Chaak

Chapter 4: The Great Hiatus and the Third Dynasty

As archaeologists began to piece together Tikal’s history in the mid-20th century, they encountered a confusing problem. Between 562 and 692 - a full 130 years - not a single dated monument was built in the city, nor were there any large construction projects. It was as if the leadership of the city had simply left for over a century. Further complicating this picture is the fact that many Early Classic monuments that predate 550 AD were vandalized[38]. This time became known as the "Hiatus", but today, scholars have a much richer understanding of this period. The lack of monuments at Tikal during the Hiatus no longer hinders an understanding of the period as much as it previously did because much has been learned from decorated commemorative ceramics and monuments in other cities.

Far from being a period of quiescence, it is now known that this period was marked by chaos, political intrigue, and war. The roots of the Hiatus begin in a troubled period between 508 and 562. After the death of Chak Tok Ich'aak on July 24, 508, there appears to have been a vacuum of power, which was made perfectly clear 13 days later when the relatively weak city of Yaxchilan captured one of Tikal’s vassal cities. The exact events after this are largely lost because most of the stelae are defaced or unfinished, but it appears that Tikal’s elite became divided between two factions.

Around this time, a figure called the "Lady of Tikal" appeared on the stage. A daughter of Chak Tok Ich'aak, she was only four years old when her father died and was undoubtedly a pawn of a larger faction, at least initially. She appears on stelae in 511, 514, and 527, but always in association with a male co-ruler, and in 527, she was depicted as ruling alongside Kaloomte' B'alam, a general involved in the 486 attack on the city of Maasal and usually considered the 19th king of Tikal. However, somewhere between 527 and 537, she becomes associated with the 20th king, lord "Bird Claw."

By 557, fortunes appear to have shifted, as another king, "Double Bird", is marked as the 21st king. Double Bird was also the child of Chak Tok Ich'aak II, born in January 508, only seven months before his father's death. He is commemorated as having come to power on January 29, 537, and the monuments record him as having "returned" (presumably from exile) during this period.[39]

As these records suggest, the death of Chak Tok Ich'aak II led to dynastic strife, with different elements of his court seizing his two young children as pawns to make separate claims to the throne. Meanwhile, the internal divisions of the city meant that Tikal’ elites were unable to maintain their control on wider Mayan politics. In 553, Double Bird is recorded as sponsoring the ruler in distant Caracol, but in the same year, the far closer kingdom of Naranjo became a vassal of the rival city of Calakmul. This was followed in 556 by a direct war with the now-rebellious Caracol, where Tikal lost a vassal to the upstart city. Finally, in 562 there was an event called a “star war”, a war that was timed to coincide with the movements of Venus. During this war, an army likely consisting of the combined forces of Caracol and Calakmul overran Tikal and ritually killed Double Bird.

It’s certainly noteworthy that early archaeological studies have documented the simultaneous collapses of Teotihuacán and Tikal, but it’s unclear how or whether the two are linked. Did Teotihuacán recall its soldiers from Tikal? Was the fall of Teotihuacán seen as a withdrawal of divine mandate and something that might have galvanized Tikal's enemies? Another theory is that the collapse was brought about by the collapse of trade and the inability of Tikal's elites to maintain their own trade routes. Regardless of exactly what the connections were between the collapse of Tikal and Teotihuacán, 562 AD was a momentous one in Mesoamerica because it witnessed the collapse of the region's mightiest city and the conquest and subjugation of its second-most powerful.

Debates over the internal divisions in Tikal and the effects of the collapse of Teotihuacán also overshadow the fact that the collapse of Tikal's hegemony was at least partly a product of a geopolitical strategy by two rivals: Caracol and, especially, Calakmul. Calakmul was, like Tikal, an inheritor of the ancient Preclassic era, having emerged from being a vassal of El Mirador and Nakbé. The capital of the kingdom was located 24 miles (39 km) to the north of the ruins of old El Mirador and seemed to have claimed to be the rightful heir of that ancient city. In this way, the rulers of Calakmul leapfrogged over Tikal and Teotihuacán, effectively asserting themselves as the true heirs of the Mayan civilization.

Calakmul and the kingdom it ruled, called Kaan (the Kingdom of the Snake), remained in the shadow of Tikal during Tikal’s glory days, but the kingdom was never conquered by Tikal or the Teotihuacanos. In the 540s, Calakmul began to cement power and began implementing a strategy to displace Tikal. King Stone Hand Jaguar and then King Sky Witness worked throughout the 540s and 550s to bring to heel one small city after another in order to create a ring of enemies around Tikal. In the process, they apparently hoped to be able to starve Tikal politically by denying it tribute from vassals and preventing it from reconstituting trade networks to Central Mexico that were in decline with the collapse of Teotihuacán.

It appears that despite their divisions, the Tikal elites were aware of this strategy, at least after Sky Witness' troops brought Caracol under his banner in 561[40]. Tikal's last Second Dynasty king, Lord Double Bird, ordered an attack on Caracol in 562, no doubt hoping to break the stranglehold that Calakmul had created. Unfortunately, he underestimated the strength of his enemies or perhaps overestimated his own power. He not only failed to take Caracol in that attack but subsequently lost everything in the alliance's counterattack[41].

Sometime around 593 AD, a new king is recorded as ascending to the throne of Tikal: King Animal Skull, 22nd in the line. There is evidence to show that this ascension involved the rise of a third dynasty to power. For one, there is an oblique reference to the ritual killing of Double Bird, and the pottery made for Animal Skull makes much of his matrilineal connections to Tikal's elite but is completely silent about his father. In fact, scholars’ understanding of the line of the earliest kings comes from retrospective ceramics that trace his lineage. Both of these elements give weight to the argument that Animal Skull was part of a new ruling family put into power by the victorious Caracol and Calakmul, a common occurrence in Mayan conquests[42].

In the normal course of events, this conquest should have been the political end of Tikal. A typical example would be Tikal's old rival Uaxactun, which became a minor player after its conquest. There’s no doubt that the victorious powers of Caracol and Calakmul had much at stake in keeping Tikal under their thumb.

After the death of Animal Skull in 628 AD, there appears to have been a relatively orderly transition, as his tomb was constructed immediately and was well made and adorned. However, this unity was not to last, as a schism appears to have occurred as early as 648 AD. Roughly 70 miles (112 kilometers) to the southwest of Tikal, a new city named Dos Pilas had a king, B'alaj Chan K'awiil, who claimed to be the legitimate ruler of Tikal. His ascension to the throne was backed by Calakmul[43], but meanwhile, back in Tikal, a ruler named Nuun Ujol Chaak ("Shield Skull") - a rival of B'alaj Chan K'awiil in Dos Pilas - took the throne.

In response, Yuknoom the Great of Calakmul launched another star war in 657 to eject the upstart, but the results of this conflict are confusing. Shield Skull fled Tikal to the distant city of Palenque (another enemy of Calakmul), but B'alaj Chan K'awiil and the Dos Pilas elites seemingly did not return in triumph to Tikal. It’s unclear why this happened, but some have speculated that Calakmul decided to rule the city directly. Shield Skull is recorded as being present in Palenque in 659, but he eventually retook Tikal and then Dos Pilas itself in 672. Yet again, Calakmul attacked Shield Skull's forces and drove him out of Dos Pilas in 677, and he was defeated once and for all in 679 AD[44]. While scholars aren’t certain, it seems that the Third Dynasty continued in exile in Dos Pilas until around 807 AD.

To understand Tikal during the Hiatus, one helpful comparison is 20th century China. Internally divided and beset by enemies, the traditional dynasty (the Second Dynasty in Tikal or the Manchus in China) was overthrown and puppet rulers - perhaps with ideological ties to foreign powers - are put into place (Tikal’s Third Dynasty and the pro-Western government of Chiang Kai Shek), and the nation is ringed with enemy states (Naranjo, Caracol and others for Tikal and Japan, Korea and India for China). When revolution topples the government, a rump of survivors flees and establishes a petty domain under the protection of the former masters, for whom it is useful to recognize the exiles as the legitimate government (in these cases, Dos Pilas and Taiwan).

Despite his overall failure to restore Tikal to glory, Shield Skull was successful in igniting the embers of his city's independence and power, something his son was to see through. This son, Jasaw Chan K'awiil I, was possibly the most important ruler in the long history of Tikal.

An altar depicting Jasaw Chan K'awiil I

Chapter 5: Jasaw Chan K'awiil I and the Fourth Dynasty

The most famous building at Tikal, and arguably one of the most famous and evocative buildings in all of the Mayan kingdoms, is the plainly named Temple I. Temple I, which stands 154 feet (47 meters), is not the tallest building at the site, but its incredibly steep sides, crowning temple, and the existence of its mirror in Temple II across the plaza all give it a remarkable quality that visitors have noted for centuries. The tomb sits hard against the North Acropolis, but it is not properly part of that complex; in essence, Temples I and II dramatically frame the Acropolis. It is perhaps fitting that the tomb of Jasaw Chan K'awiil I - the greatest king of Tikal – both gives a nod to the burial traditions of the North Acropolis but also breaks them, because after Jasaw, no other king would be buried in the ancient halls of their ancestors.

The back of Temple I

The front of Temple I. Picture by Dennis Jarvis.

Jasaw Chan K'awiil faced an uphill battle when he came to power on May 3, 682. He viewed himself as a restorer of Tikal, but he probably had little to work with: his father's armies had been defeated five years earlier, a rival dynasty claimed his throne in Dos Pilas, and it is possible that enemies occupied his capital city. While he may have had some help from his father's allies in Palenque, the fact that he overcame all of these challenges and finally defeated the armies of Calakmul in open battle on August 5, 695 is a testament to his skill as an administrator, diplomat and tactician[45].

As a restorer, Jasaw Chan K'awiil sought to remind his city of its former glories, so he openly revived the symbolism of long-fallen Teotihuacán, especially its regalia (much in the same way that Europeans would use Roman symbolism centuries after that empire's collapse). He had an eye for the past, including hosting the commemoration of his 695 battle on September 14 in order to also commemorate the 13th K'atun anniversary (256 years - an auspicious number) of the death of his Teotihuacano progenitor Spearthrower Owl[46].

After breaking the stranglehold of Calakmul's noose around Tikal, Jasaw Chan K'awiil began to recreate the old empire. He may have taken Masaal and Naranjo as the spoils of the 695 victory (though he had to put down rebellions in Naranjo later), and he must have taken great satisfaction in sacking Dos Pilas in 705. By 711, he had retaken the cities of Motul de San José, El Perú and Uaxactun. Once these conquests were complete and the Noose was broken, Jasaw Chan K'awiil set about a large number of building projects in the capital before his death in 731 AD.

Despite his emphasis on continuity with the ancient past and his obvious assertions of the inheritance of Teotihuacán's legitimacy, Jasaw Chan K'awiil appears to have been the founder of the Fourth (and final) Dynasty at Tikal. Of course, historians don’t know (and probably never will) whether Jasaw Chan K'awiil was actually the direct inheritor of Double Bird, the last Second Dynasty ruler, but either way, he was succeeded by several generations of rulers. His son Yik'in Chan K'awiil, the 27th king, ascended in 734 and built upon his father’s triumphs to strengthen the empire, forever shattering Calakmul's desire to dominate in a series of military campaigns that also reshaped the center of Tikal and reflected its return to grandeur.

At the city's height around this time, it had over 60,000 inhabitants covering 10 square miles (25 square kilometers)[47]. This period of strength continued through two more kings until the reign of Yax Nuun Ayiin II in 794 AD. During the city's peak, its merchants were trading in, salt, cotton, cacao, obsidian, jade, and feathers, and the city dominated the region's rivers and ports, reconstituting trade networks that had declined during the Hiatus.[48]

Chapter 6: The Collapse

At the start of the 9th century, it may have seemed to Tikal’s residents that the city had passed its darkest days and would rule the region for another six centuries, but in reality, the city and its sociopolitical order would soon be history. This period would become famously known as the Mayan Collapse.

After the relative prosperity of Yax Nuun Ayiin, the Tikal elites once again went quiet. The important ritual date of the 10th Bak'tun in 830 was not commemorated in stone, one part of a 60 year period known as the Second Hiatus during which there were no monuments. Between the years of 809 and 869, there is no evidence of any central authority in the city; while there must have been some form of order, there is nothing to suggest that it was a traditional dynasty with pretensions to the classic power.

In 869, Jasaw Chan K'awiil II, a name likely chosen in homage to the famous king of the past, had a stela erected in his honor as king of Tikal, but he was unable to prevent rulers in Tikal’s small vassal cities from asserting their claims to Tikal’s throne, something that had never occurred before. The last monument built in the city was in 889 AD, and while the city was not immediately abandoned (there is archaeological evidence of settlements there lasting until the late 10th or early 11th centuries), the subsequent generations of residents did not even maintain the pretence of dynastic rule. In fact, some of the residents actually squatted in the palaces and temples and mined the North Acropolis tombs for their treasures. Similarly, in Dos Pilas, crude earthworks were built that cut right across old roads, courtyards and even buildings[49]. There is also evidence that local groups in the region regularly raided each other.

One of the palaces in Tikal. Picture by Dennis Jarvis.

The Mayan Collapse has fascinated Westerners since the ruins were first discovered and described by 19th century European visitors. The modern-day obsession with "mysterious sites," evidenced by a raft of dubious documentaries and spurious scholarship attributing Mayan triumphs to everyone from aliens to Atlantis, has obscured the fact that recent scholarship has done much to clear up not only the details of the dynastic struggles of the Maya but also the reasons for the eventual collapse of their civilization. In fact, there is nothing shocking about the idea that an entire cultural area can suffer an irretrievable collapse, as history offers plenty of examples. In his book on the subject, Collapse, How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Jared Diamond examined not only the Maya but also Easter Island, the Pitcairn Islands, the Anasazi, the Vikings in Greenland, and contemporary China, Australia and Hispaniola.

In his book, Diamond argues that the Mayan Collapse was a gradual ecological development brought about by the political and economic systems of Tikal and other cities. Mayan agriculture was heavily dependent upon corn, a relatively protein-poor food (compared to wheat and barley), and they lacked access to a wide selection of domesticated animals, since they only had access to dogs and turkeys. This production was significantly lower in the Maya area than in other parts of Mesoamerica because of poor soils and humid climate. Humidity prevented storing corn for more than a season, the lack of draft animals meant that food could not be transported long distances, and agriculture was labor intensive[50].

As the population levels peaked in the Late Classic period, the time of Tikal's second zenith around the 700s, Mayan farmers were exploiting increasingly precarious farmlands, leading to deforestation and erosion on an unprecedented scale. Even the glorious buildings in the center of Tikal would have needed immense amounts of wood to make the thick layers of plaster that covered the surfaces. In turn, this may have led to human-produced droughts caused by the disruptions to water cycles, all due to lack of forests and the speed of runoff without the entrapment caused by roots. Furthermore, in 760 AD, the worst regional drought in thousands of years began, lasting over four decades and exacerbating all of these problems As eroded farmland was abandoned and drought spread, there would have been increasing conflicts amongst farmers and growing anger at the ruling class that was not performing its role as intercessors with the divine. In fact, in the city of Copán, that anger would turn to outright violence; the royal palace was burned to the ground in 850 AD, and nothing was heard from the elites after that.[51]

The Collapse affected a wide range of Classical cities, including Tikal, Calakmul, Palenque and Caracol, but it did not affect all of the Maya. This was especially true of those in the far north of the Yucatan Peninsula, who would found new cities like Uxmal, Chichén Itzá and Mayapán in the wake of the Collapse. Moreover, the Maya themselves around Tikal did not disappear. In fact, they live there still, making up the majority of the population of northern Guatemala and surrounding Mexican states. Instead, the Collapse should be understood as a political event: the collapse of the traditional Mayan dynastic system and the loss of much of the Mayan population in the resulting famines.

What did the Collapse look like? It was a slow-moving event, affecting peripheral areas first and the great heartlands later. Famine and drought would have driven peasants from marginal lands, filling the cities with beggars and swelling recruits to armies. Some families would march far away to the north in search of new lands, founding Yucatecan cities like Uxmal. At the same time, rival kings would have sought to take advantage of weaker rivals or expand their weakening agricultural base at their enemies' expense. Increasingly desperate armies likely came to resemble bandits, and their kings probably acted more like bandit captains. People may have turned to religion and then turned against it, desecrating temples and burning palaces, killing kings and priests. The population shrunk, not only from outright deaths from starvation, disease and war, but because in desperate and uncertain times when the world seemed to be falling apart, they likely had fewer children[52]. Those that did survive to carry on left the cities to avoid all the troubles, and in the process, Tikal and its rivals were ultimately reduced to ruins. When thinking about the Maya Collapse, many descriptions might come to mind, such as "tragic," "fascinating," and even "inevitable", but "enigmatic" and "mysterious" are not among them.

At the same time, it’s clear that Tikal influenced later Mayan settlements. Besides its direct role in dominating the political and economic structure of the Mayan heartland during its periods of regional hegemony, Tikal had a much larger place in Mayan history as one of the fonts of the more sophisticated elements of Mayan culture. The first of these was serving as a political role model far beyond the areas it controlled. At its height, other Mayan cities’ rulers took great pains to demonstrate their genealogical and ideological links to Tikal, even emulating the city's royal ceremony and regalia. This was especially true after the Teotihuacano Entrada, when the dynastic system was infused with the patriarchal systems and religious rituals and symbolism of Central Mexico. Even after the Collapse of Classical Mayan civilization, it seems that refugees who came to the northern Yucatan also brought this dynastic tradition (albeit with many changes) when they founded new cities like Uxmal, Chichén Itzá and Mayapán[53].

Furthermore, scribes in Tikal were at the forefront in transforming the incipient writing system they inherited from El Mirador and Nakbé into a sophisticated, fully-formed orthography capable of expressing all of the subtleties of human language. This remarkable feat - the creation of writing - has only been accomplished three times in human history: in Mesoamerica, Mesopotamia and China. The beautiful Mayan glyphs reached their fullest flower in Tikal and its neighboring cities, and even today, over 7,000 texts of varying length survive[54].

Chapter 7: Modern Tikal

“The imagination reels. There are reliefs, pyramids, temples in the extinguished city. The damp murmur of the arroyos, voices, crepitations of the intertangling vines, the sound of flapping wings, trickle into the immense sea of silence. Everything palpitates, breathes, exhausting itself in green above the vast roof of Peten.” - Miguel Ángel Asturias (1967 Nobel Laureate), in The Mirror of Lida Sal: Tales Based on Mayan Myths & Guatemalan Legends, p. 13-14.

The city of Tikal was abandoned, but it was never truly lost or forgotten. When the Spanish arrived in the Lake Peten Itzá area in the 1620s, they found the local Itzá Maya rulers from the nearby lake city of Tayasal worshiping at the ruins and venerating its builders, well aware that ancient Tikal’s people were their ancestors[55]. In the Colonial period, it was occasionally visited by Spaniards and was certainly well-known by local hunters who regularly traveled through it on their treks.

The first Guatemalan government survey of the ruins was done in 1848, and this was followed by Eusebio Lara's drawings of stelae on the site, which attracted considerable attention. While Guatemala declared its independence in 1825, it was not until 1840 that it was fully independent of the United Provinces of Central America. Since the very beginning, Guatemala has sought to establish its national identity based in part upon a glorification of the ancient Mayan past, which is deeply troubling considering the great lengths that this same government has gone to keep down the Mayan peoples actually living in its territory, even to the point of an attempted genocide in the late 20th century. Despite these contradictions, the Guatemalan government has based much of its symbolism upon the Maya, including a Classical sculpture of a Mayan head on the 25 centavo coin and Tikal's Temple I on the back of the old 1/2 Quetzal note. [56]

In 1877, Europeans became increasingly interested in Tikal and the other ruins, especially after Austrian national Gustav Bernoulli visited the city and took a series of wood carved panels back home with him[57]. These panels, which were from Temples I and IV depicted, the life of Jasaw Chan K'awiil I, and while their plunder and movement to museums in Austria was certainly a theft from the Guatemalan people, it allowed the fragile wood to be preserved to the modern day. After Bernoulli, there were other expeditions. In 1881 and 1882 the English proto-archaeologist Alfred Maudslay made a map and survey of the city, and Teobert Maler took photos for the Peabody Museum[58]. From 1926-1937, Sylvanus Morley from Harvard University and the Carnegie Institute made surveys, and there has been an almost continuous period of work at Tikal since, including an elaborate 18 year project by the Guatemalan Government and the University of Pennsylvania[59].

In 1979, the site was given recognition by the United Nations Education, Science and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a "World Heritage Site"[60]. It did so on a number of overarching criteria that capture some of the ruins' importance to humanity; Tikal was selected “to represent a masterpiece of human creative genius; to bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared; to be an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human history…”

The site's ecological value, preserving a wide swath of forest as it does, is also recognized by UNESCO. In this regard, Tikal was selected “to be outstanding examples representing significant on-going ecological and biological processes in the evolution and development of terrestrial, fresh water, coastal and marine ecosystems and communities of plants and animals; to contain the most important and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation.”

Of course, Tikal is not simply a site of research or international recognition but also a premier tourist site today. Thousands of tourists come annually to marvel over the ruins of the once mighty city, helping ensure that the world’s fascination with the Ancient Maya doesn’t end anytime soon.

Uxmal

Chapter 1: Description of the Site

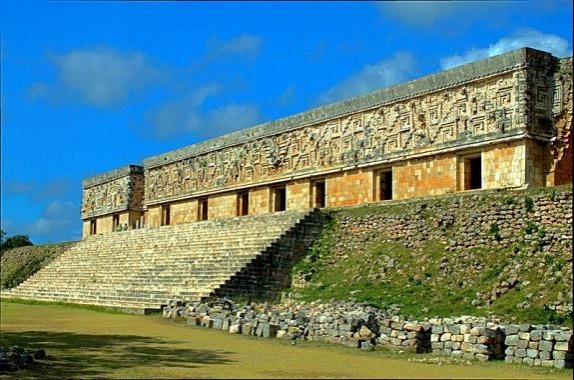

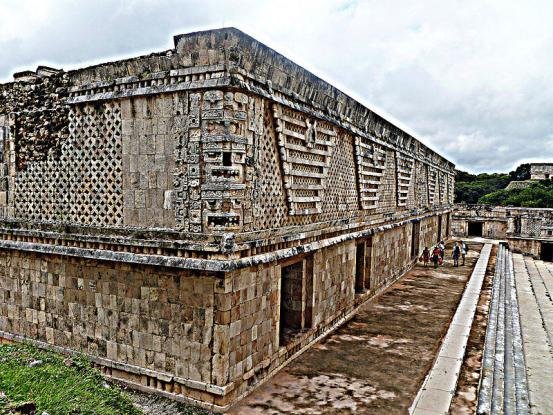

A picture of the front of the Governor’s Palace

"We took another road, and, emerging suddenly from the woods, to my astonishment came at once upon a large open field strewed with mounds of ruins, and vast buildings on terraces, and pyramidal structures, grand and in good preservation, richly ornamented, without a bush to obstruct the view, and in picturesque effect almost equal to the ruins of Thebes...The place of which I am now speaking was beyond all doubt once a large, populous, and highly civilized city. Who built it, why is was located away from water or any of those natural advantages which have determined the sites of cities whose histories are known, what led to its abandonment and destruction, no man can tell." - John Lloyd Stephens, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas & Yucatán, 1843[61]

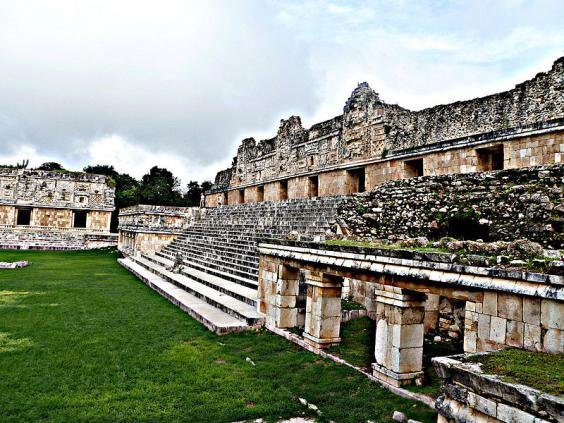

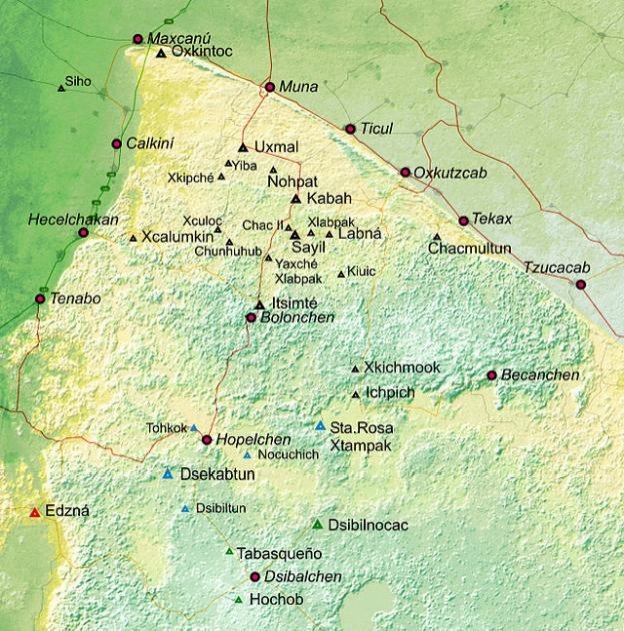

The city of Uxmal, which once housed an estimated 20,000 people in its urban core and many thousands of others in peripheral farms and vassal cities, is the northernmost of the Puuc city-states that thrived for several centuries in the northern Yucatán Peninsula beginning around the 800s. Uxmal is a majestic city even in its modern ruined form, dominating the landscape from its position atop the Puuc and looking out over the great wide plain of the Yucatán jungle. From atop its pyramids, its ancient rulers must have been able to see much of their kingdom.

While Uxmal would eventually be superseded in economic and political might by the lowland cities of Chichén Itzá and Mayapán, it would maintain its stately glory long after the city’s arrival on the scene and even become a venerated dowager empress to these later cities. Even after its abandonment, the Maya continued to come to its ruins for ceremonial purposes, and their noble families proudly traced their ancestry back to its halls. .

Like all Mayan cities, Uxmal is built around a ceremonial core centered on temples[62], and in Uxmal, this core was built along a north-south axis and was roughly 100,000 square feet (30,000 square meters) in size. The core's social role is comparable to the Westminster area of London: large buildings for administration, housing royals, religious worship and large public gatherings and celebrations[63]. That said, one of the major differences between Uxmal and its southern Classical precursors is that the monumental architecture dominating the city's core is not focused upon the entombment and veneration of dead monarchs but is instead focused upon facilities for the use of the living. In other words, the broad plazas before the tomb-pyramids (such as the central plaza of Tikal) was replaced as the city focal point by grand halls and palaces around central courtyards in Uxmal[64].

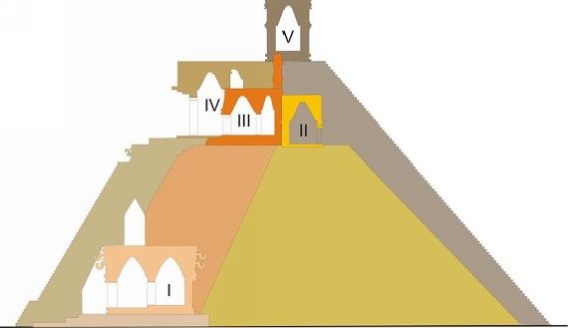

The most famous structure in Uxmal is probably the "Pyramid of the Magician," a name that comes from the Spanish "Pirámide del adivino" (which is probably better translated as the Pyramid of the "Diviner" or "Soothsayer"). Rising 115 feet (35 meters), it is crowned by a temple, but unlike all other Mesoamerican pyramids, the base of this structure is elliptical in shape, with the longest measurements of its sides being 280 feet (85 meters) by 165 feet (50 meters).

The Pyramid has five chambers that are traditionally considered to be temples and which archaeologists have numbered using Roman Numerals. Temple V sits at the crown and is called the House of the Magician,[65] and it is known for its impressive latticework panels. Just below it on the structure is Temple IV, which was far more sumptuous in its décor compared to the relative austerity of Temple V. The gate to Temple IV was enormous and covered in zoomorphic masks, geometric patterns and statuary. Since the entrance to Temple V was not visible from the ground, but Temple IV was, it was probable that IV was the central public space of worship[66]. From a distance, as a visitor ascends towards Temple IV, the facade looms above him or her and appears to be the maw of some terrible monster, and it is only when the visitor reaches the top that the complex patterns of statuary and carving separate from one another[67]. This face has been argued to be the creator god Itzamna[68], who is sometimes depicted as a great serpent[69].

Pictures of the Pyramid of the Magician

Map of the layout of the Pyramid of the Magician

As that description suggests, the Pyramid of the Magician demonstrates that Uxmal fused a number of architectural styles as it was seeking its own aesthetic (what would eventually become the Puuc Style, detailed below). The ornate Temple IV is in a more Classical, southern style called Chenes, while the simpler Temple V is in a local Puuc style[70].

To the south of the Pyramid of the Magician is the "Governor's Palace," or the "House of the Governor," which is sometimes considered to be the greatest masterpiece of Mayan architecture. The Palace, which was almost certainly a royal palace, is the largest building in Uxmal and is built on a platform that was located atop another platform (48 feet, 15 meter tall). The Palace is built with a simple, harmonious plan: a long central building flanked by two smaller structures joined to it by roofed arcades. The three buildings share a roof line and are joined together by sharing their raised dais, with a single central staircase.

The compound also had a facade decoration of remarkable contrast. The lower exterior walls, up until a little over the tops of the 13 identical doorways, were covered in smooth, undecorated stucco, but above this is the decorative cornice, a massive carved surface covered in images of ancestors, deities (especially Chaak the rain god), and elaborate geometrical images. Each panel was undoubtedly a work of art comparable to the famous friezes of the Parthenon in Athens (now on display in London). Visitors approaching the central staircase finds these friezes to be particularly impressive because the building has a feature called a "negative batter," meaning that the front walls lean forward. In fact, the base of the facade is close to two feet further from the front staircase than the crest of the frieze. The effect of this carefully planned feature is that the friezes appear to soar overhead, giving additional drama to the structure. The interior of the structure was similarly dramatic, with high vaulted arches and broad paved rooms[71].

Pictures of the Governor’s Palace

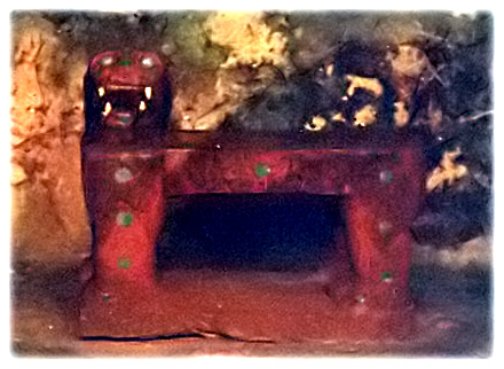

In front of the House of the Governor is a broad plaza, and on the far side is a worn stone throne carved in the shape of a two-headed jaguar. If one was to stand in the center of the House of the Governor and look directly toward the throne, in a straight line beyond it would be the main pyramid of the vassal city of Kabah. The two-headed jaguar throne appears to have been a symbol of the city since it appears in stone carvings, including one of the only known king, Lord Chak.

Picture of the stone throne

Pictures of the Great Pyramid

Sculptures atop the temple on the Great Pyramid

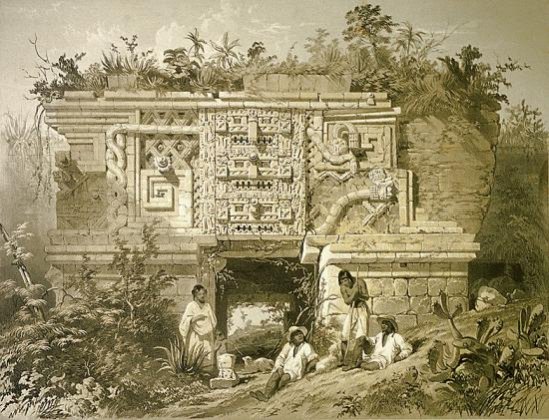

The other large structure within the ceremonial center (which has a number of smaller temples, ceremonial ballcourts and elite residential complexes) is called the Nunnery Quadrangle, due to its similarity to a Spanish cloister. This is believed to have been the home of one of the city's elite families and is the grandest of numerous palaces in the city. The complex has four buildings surrounding a central plaza, and it is located almost at the feet of the Pyramid of the Magician. Each of the four buildings is distinct as well. For example, the North is the largest and is 330 feet (100 meters) long and 23 feet (7 meters) high, with friezes that mimic a number of the themes found in the Palace of the Governors. The West building is elaborately decorated with images of the great Central Mexican and Chichén Itzá god Kukulkán the feathered serpent and the earth god Pawahtun. The East building is far less grand but has two-headed serpent carvings, while the friezes of the South building have depictions of miniature houses and mask panels. Archaeologists have argued that the iconography of the North building is associated with the heavens, the West building with the earth, and the South building with the underworld. The East building is still being interpreted[72].

The North Building

The East Building

The South Building and West Building

A feathered serpent engraved on the West Building

While often overlooked by tourists and even many archaeologists, the bulk of the city of Uxmal is found not it the impressive buildings of the ceremonial core but in the residential neighborhoods that sprawl outwards from it. After all, it was here the the vast majority of the citizenry lived and worked, and like all Maya cities, Uxmal was strongly divided between a small elite and a massive laboring class beneath them.

Of course, the residential homes reflect this division. The simplest form of housing was (and in many areas of the rural Yucatán still is) the "pole-and-thatch" style. In this type of home, the builder creates a wooden framework based around four corner poles, and once this framework is in place, outer walls are constructed by lashing horizontal poles between the uprights at the top and bottom and then creating a fence of thin branches between them. The resulting home is only semi-enclosed, so while visitors cannot see in, residents can see out, and breezes waft through the building to keep down the often-oppressive heat. The roof of the home is made of thatching, and the floor of the hut is made of pounded earth which can be easily kept clean by sweeping.

While central buildings like the Pyramid of the Magician or the Governor’s Palace were most certainly planned formally by professional architects, the vernacular architecture of the common Maya home was built in a more piecemeal fashion. Generally speaking, buildings were constructed around a central courtyard that included space for gardens, perhaps pens for turkeys, a cistern full of wáter, and outbuildings like a kitchen (separated to prevent losses from cooking fires and to keep the main home cool) and a washroom (the Maya are fastidiously clean and sometimes bath several times a day). As the extended family grew, new rooms might be added to the perimeter of the courtyard, including separate sleeping rooms for unmarried children, new bedrooms for recently-married couples, and other storage rooms. Pole-and-thatch would eventually be replaced if the family had enough wealth to build stone walls, so a family compound may have a combination of wooden and stone buildings.

As might be expected, the stuccoed white stone homes had several advantages over their wooden predecessors. Among other advantages, they did not blow away during the periodic hurricanes, they were safer from thieves, they remained cooler than the outside, and they were a symbol of the family's status. That said, even within stone construction, there was a wide variety of stones of varying qualities, as well as a wide range in proficiency among the carvers and masons, meaning that not all stone construction was equally prestigious. As a result, it was possible for very wealthy individuals to demonstrate their status through the construction of stunning buildings made of exceptional stone, both in size and level of quality[73].

Even the homes of elites had a number of similarities to those of the commoners. As was described above in the Nunnery Quadrangle, the wealthy also had homes built around central courtyards with numerous rooms facing inwards, but of course, the Nunnery also demonstrated the differences between common housing and the finest of the Uxmal palaces. For example, the Nunnery had paved floors both within the houses and in the courtyard itself, as well as a prestigious raised platform or terrace upon which the entire complex was constructed, stone roofs with vaulted arches, and elaborately decorated exteriors and interiors. Where the commoners' homes enjoyed both privacy from the exterior and the ability to look out through the loosely woven walls, the elites achieved the same effect by having stonecarvers make them elaborate limestone latticework for their walls. These elites put great effort into their homes, which appear not only to be constructed for comfort but also to be able to both host and inspire awe in large numbers of guests. The ruling class' culture in Uxmal under the rule of their council appears to have become a world of sophisticated courtly intrigue involving rival families and a need to entertain on a grand scale. The grandees of Renaissance Venice would have instantly recognized the interplay between politics and socialization that played out in these grand homes.

Chapter 2: Daily Life in Uxmal

After exploring the ruined homes of commoners and elites, visitors are left with all kinds of burning questions. What was daily life like for these people? How did they go about the events, big and small, that marked their lives? Archaeology can tell visitors much about architecture and provide insights into economic life, but it often stumbles when faced with more intangible questions and figuring out some of the more fragile parts of material life, such as clothing and food. To determine answers, scholars must supplement archaeological data with information from colonial and other written sources who recorded daily life in the Yucatán, but since these documents are necessarily several centuries older than the apex of Uxmal's influence in the late 800s, they also have to be taken with a grain of salt.