Chapter 7

Fundamentals:

Operating Statement Tests You Need to Know

The previous chapter explained analysis of balance sheet accounts. That statement reports on the balances of asset, liability, and capital accounts as of a fixed date, usually the end of a quarter or year. The operating statement is a summary of a series of transactions over a period of time, ending on a specific date. The period covered by the published operating statement reports on transactions through the same date on which the balance sheet is prepared, usually the end of the quarter or fiscal year.

These two statements represent what most people are familiar with in terms of financial reporting. The balance sheet (ending date balances) and the operating statement (summary of transactions for a period of time) are supposed to reveal to you all that you need to know in order to make an informed opinion and to develop comparative value judgments about companies. For this, fundamental analysis is based on a series of ratios and formulas intended to produce a shorthand version of the transactions (by way of percentages, ratio values, and trends). These representations are best reviewed under the following guidelines:

- Every ratio is best viewed as part of a long-term trend. The ratio by itself can be compared to a universally accepted standard, your own goals, or looked at as the latest entry in a long-term trend. The longer the trend, the easier it is to understand the significance of the ratio. Even a two-year comparison has limited value compared to a five-year or a ten-year historical record.

- The analyst or investor should ensure that comparisons are valid and accurate. The problem with the fundamentals is their very complexity and variation. Validity is not as easily found as every investor would like. If one company has significant core earnings adjustments and another does not, it makes little sense to compare the reported numbers without adjusting them to the same basis (core earnings).

- Ratios and formulas should reveal meaningful facts about risk and potential growth. Any number of ratios can be used, but you should be sure you know how to interpret the results. What does a ratio reveal about the company? How can you equate a specific ratio in terms of income potential and risk? These are the key questions to ask about every ratio and every trend.

- A program of fundamental analysis should employ a range of tests and never rely on a single indicator by itself. Analysis becomes valuable when you review an entire series of trends, each developed from ratio tests. This does not mean you need to get an accounting education. In fact, using a handful of well-selected ratios is easy and much of the work may be done for you already. Using a well-structured analytical service like the CFRA Stock Reports provides a 10-year summary and includes most of the ratios you are likely to want in your program.

- A set of conclusions for one industry may not be comparable to the same conclusions in another industry. One of the most common errors is to develop a series of assumptions about what outcomes should be, and then apply those assumptions to all companies. The truth is that every sector and sub-sector involves companies in particular industry groups, and these are, by definition, different from the companies in other sectors. Once you have decided which set of ratios to use, it makes sense to go through a review of an entire industry; develop a working idea of the standards; and adjust your expectations based on those standards. Even the most basic ratios, such as the percentage of earnings, gross profit, expense levels, and other well-known tests are going to be different between industries.

- The value judgments developed are best employed as part of a larger investment goal. When you begin to invest, you need to set goals for yourself. Most people understand this in terms of price appreciation, and they set goals based on that: “If the stock doubles in value, I will sell” or “If I lose 25% I will cut my losses” are common price-based goal statements. The same strategic approach works with the fundamentals as well, and may be based on the ratios themselves, involving tests of working capital, capitalization ratios, revenue and earnings growth, or— in the best approach of all—a combination of all of these critical areas of analysis.

However, an assumption that income and earnings as reported is by default an accurate report may be wrong. The motivations for accurate reporting are not always as strong as the alternative of reporting earnings in as favorable a light as possible, even if that means exaggerating outcomes: “Powerful incentives to reach elusive earnings expectations can create serious conflicts of interest among corporate executives eager to meet these expectations.”27

A former chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Arthur Levitt Jr., explained this problem as one of combined incentive among analysts, management, and auditors:

Companies try to meet or beat Wall Street earnings projections in order to grow market capitalization and increase the value of stock options. Their ability to do this depends on achieving the earnings expectations of analysts. And analysts seek constant guidance from companies to frame those expectations. Auditors, who want to retain their clients, are under pressure not to stand in the way.28

This problem is nothing new. In fact, the preference in “the market” (referring to a collective Wall Street insider, investors in general and institutional investors specifically, and the journalists and analysts reporting on corporate profit and loss) prefer a predictable year-to-year outcome in earnings over volatile or erratic outcomes. As a result, some organizations have practiced “cookie jar” accounting in which some earnings in exceptionally positive years are deferred until later years to smooth out results. This occurs to the extent that some estimates are reported at lower than accurate levels to avoid future negative outcomes:

Wall Street disapproves of earnings volatility in general, and frequently seeks incremental earnings growth rather than unexpected changes. Companies that have outperformed analysts’ growth expectations in the current year, will frequently fear successive years’ growth expectations, and will seek to modify those expectations by lowering current year earnings through these charges.29

With this widespread qualifier in mind, reviews of revue and earnings are best performed as part of a long-term trend and not in a single year by itself. A single year’s outcome may not be typical, so a trend-based review of revenue and earnings is a wise process.

The Basics of the Operating Statement

The operating statement summarizes revenues, costs and expenses, and earnings for a specified period of time. That time is usually a fiscal quarter or year; and the report normally includes the current period and the previous period, so that comparisons are readily made. In corporate financial statements, the major expenses are summarized in a single line, so detailed analysis requires further investigation (this often means contacting the company’s Shareholder Relations Department and requesting breakdowns beyond what is shown on the published financial statement).

The components of the operating statement are summarized in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1: Operating Statement

Because there are so many divisions to the operating statement, it is imperative to understand which line is being discussed and compared. “Earnings” should mean the same thing when comparing one company to another. The operating profit is normally used to report earnings per share, but important distinctions have to be made between the various kinds of margins found on the operating statement. These distinctions are shown later in this chapter. Below is a brief summary of operating statement divisions and terms:

–Revenue – The top line is revenue (sales) and is perhaps the best-known line and most often watched indicator on the operating statement. As a general observation, many people believe that as long as revenues are rising each year, all is well. But in reality, you are also likely to see rising revenue accompanied by falling earnings (net profits). That indicates that growth in terms of rising revenues is not always a positive attribute; it is always better when revenues and earnings both rise.

–Cost of goods sold – This segment of the operating statement is the sum of several accounts. These include merchandise purchased for sale (or manufacture); freight; direct labor (salaries and wages paid to employees directly generating revenues); and a change in inventory levels from beginning to end of the period. A distinction is made between costs and expenses. Costs are expected to track revenues closely, and the percentage of costs should remain about the same even when revenue levels change. In comparison, expenses are assumed to be unresponsive to revenues. In situations where companies expand into new markets or product areas or merge with other companies, expense levels will naturally change as well. But expenses can and should be controlled so that ever-greater profits can be achieved in periods of revenue growth.

–Gross profit – This sub-total is the dollar amount of revenues minus costs. The percentage of gross profit is called gross margin. Just as direct costs should track sales closely, the gross profit should do the same. When you see a widely fluctuating gross margin from one period to the next, further analysis is required. Possible reasons include seasonal change, merger or acquisition, development of new product line, sale of an operating unit, changes in inventory valuation method, or lack of internal controls.

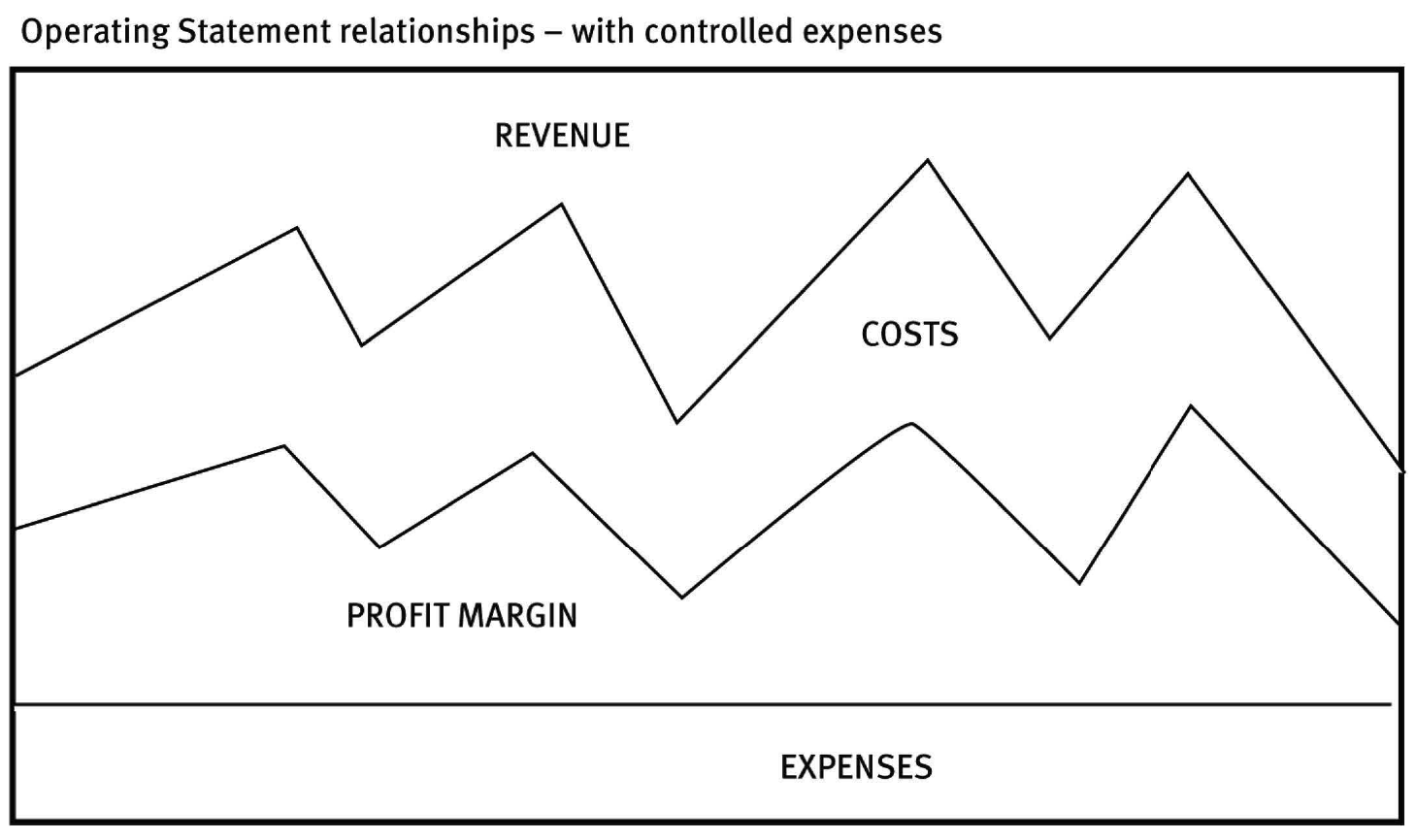

–Expenses – This category is the most varied and complex. It includes all money going out of the company as well as debts owed at the end of the period, that are not direct in relation to revenue production. The distinction between direct costs and expenses is quite important in financial statement analysis because you expect, as a general rule, to see actual internal controls having the greatest impact in this portion of the operating statement. This relationship is demonstrated in Figure 7.2. Note how the changes occur as revenue and costs increase or decrease. First, revenue and costs track on the same trend, as you would expect. Skip to the bottom and you see the area of expenses, which is flat as you would expect. If this trend continues, the profit margin grows when revenues grow, and shrinks when revenues shrink.

Figure 7.2: Operating Statement Relationships – with Controlled Expenses

Consider what happens when expenses are not controlled. In that situation, the level of expenses tends to rise over time and does not retreat if and when revenues decline. As a consequence, the profit margin shrinks even when revenues rise, and shrinks severely when revenues fall. This relationship is summarized in Figure 7.3. Note how much difference gradually increasing expenses makes. Expenses rise regardless of revenue and cost trends. At the end of the chart, revenues decline so that the profit margin shrinks considerably. Finally, it ends up in the territory of net losses. When a company experiences a net loss, it is usually due to a combination of events, including reduced revenues, non-recurring adjustments or non-core losses, and—most severe of all—uncontrolled expenses.

The level of expenses can also be further subdivided, although the published annual reports and financial statements do not always provide these details. For example, two major sub-divisions are selling expenses (those expenses related to generation of sales but not as directly as direct costs) and general and administrative expenses, also called overhead. These expenses recur each year regardless of revenue levels, and include administrative salaries and wages, rent, office telephone and office supplies, for example.

Figure 7.3: Operating Statement Relationships – with Uncontrolled Expenses

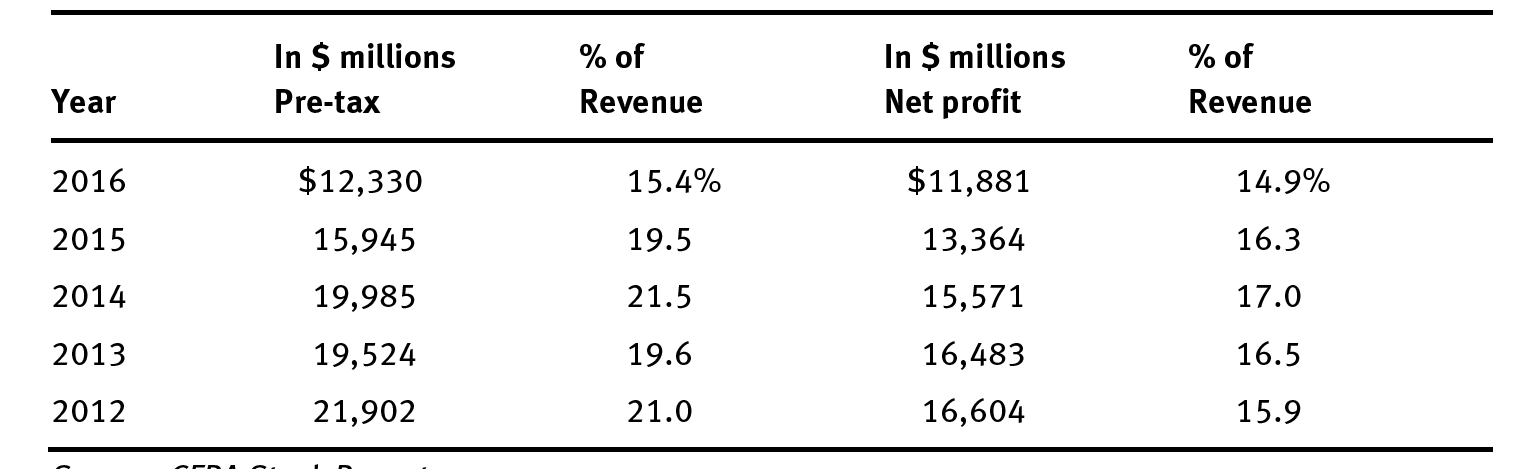

–Operating Profit – This is the profit from operations which, in most instances, will be the same as (or close to) S&P-defined core earnings. If the company has done a good job of isolating non-operating expenses below this line, then it is a reliable number; but companies do not always make these matters clear. In fact, they may be obscured by application of inconsistent standards, even with the blessing of the GAAP system. Another problem arises in the fact that published earnings are usually computed on the bottom line (net profit) which is likely to include an array of non-operational items. To gauge the significance of this distortion, compare the earnings reported for IBM over five years, both pre-tax and net. This is shown on Table 7.1.30

Table 7.1: Earnings History, IBM

Source: CFRA Stock Reports

This comparison reveals the actual trend. Pre-tax and net earnings both declined during the five-year period. And whereas the pre-tax percentage of revenues declined, the net profit percentage remained more consistent, between 14.9% and 17.0%. This is a reflection of a lower set of adjustments, for tax liabilities as well as non-operating items. However, the pre-tax outcome was disturbing because of the overall decline in both dollars and net yield.

–Other Income and Expenses – Following the operating profit are a series of additional adjustments, all part of the non-core or non-operational section. In an ideal world, all core earnings adjustments would show up here so that the operating profit could be a universally understood, consistent number. But because so many core earnings adjustments involve expenses not listed on the operating statement, this is not likely to occur any time in the near future. Other income includes profits from the sale of capital assets, currency exchange adjustments, interest income, and the sale of operating units. Other expenses include losses from the sale of capital assets, currency exchange losses, interest expenses, and other non-core forms of income.

–Pre-Tax Profit – When you add or subtract the net difference between other income and other expenses from operating profit, you find the pre-tax net profit. This is the value often used in analysis to report net earnings, but because it includes the effect of other income and expenses, this is less than accurate; and when comparing return on sales among different companies, there will be a lot of variation in the pre-tax profit.

–Provision for Income Taxes – Companies set up reserves to pay income taxes, and this provision appears here as the second-to-last line of the operating statement. This value can change considerably and for a number of reasons. First, a company may be reducing its tax liability with carryover losses. Second, tax reporting is not always the same as GAAP reporting, so differences in the taxable net income or loss will affect the provision. Third, companies operating in foreign countries may pay a higher or lower overall tax rate depending on their mix of profits. Fourth, companies based in states that do not tax corporate profits will pay lower taxes than those in states with state-level income tax laws on the books.

–After-Tax Profit – This is the “net net” profit or loss, the bottom line most often used to calculate earnings per share. The problem with this is that, as the previous explanations demonstrated, the after-tax profit is subject to many accounting interpretations, non-recurring and non-core adjustments, and other factors that make a true comparison between companies less than reliable. Only the operating profit provides an approximation of outcome that can be treated as comparable; but EPS is usually reported on the basis of the bottom line, so investors get a distorted view of a company and its value and profitability.

Revenue Trends

Beginning at the top line of the operating statement, analysis begins by tracking revenue trends. Just about every analyst wants to see revenues grow each year. However, each sector involves competing companies and finite markets, so it is not realistic to expect every well-managed company to increase its revenue every year without fail.

Even when corporate revenues do grow, investors and analysts may place unrealistic expectations about the rate of growth. In other words, if a company increased revenues by 5% the first year, 10% percent the second year, and 15% last year, should you expect a 20% growth rate this year? All statistics tend to level off over time, but that does not mean a slow-down in the rate of growth is bad news; it is simply reality.

The most popular method for tracking revenue is by year-to-year percentage of change (up or down) in revenues. This is a reasonable method for tracking revenues, because it ignores the dollar amount and reduces growth to a simple percentage. If a company’s annual growth rate remains consistent or shows little change, that is far more positive in the long term than the less realistic demand for ever-higher rates of growth. To calculate the rate of growth in revenue, the formula is:

Formula: rate of growth in revenue

(C – P) ÷ P = R

C = current year revenue

P = past year revenue

R = rate of growth in revenue

Excel program

| A1 | current year revenue |

| B1 | past year revenue |

| C1 | =SUM(A1-B1)/B1 |

For example, current year revenue was $93,580 (in millions of dollars) and past year’s was $86,833. The formula for rate of growth:

($93,580 – $86,833) ÷ $86,833 = 7.8%

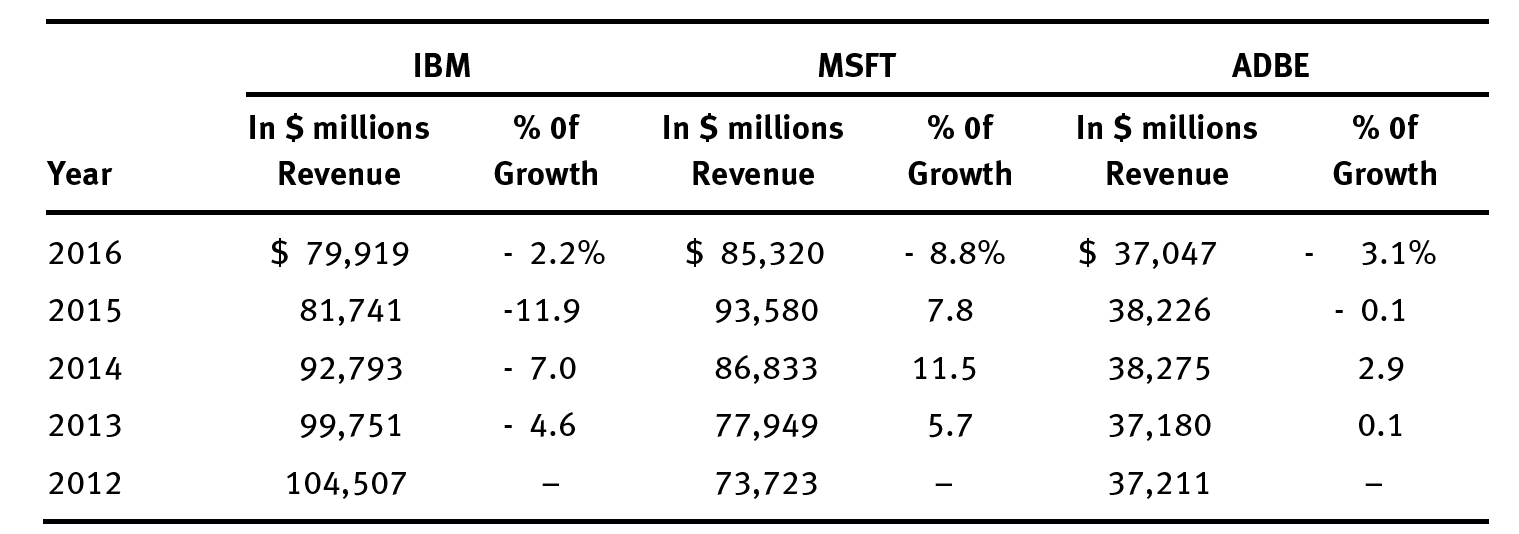

It is more revealing to compare rate of growth (plus or minus) than to review the dollar values of revenue from year to year. To demonstrate this, consider the case of three companies over a five-year period. This is summarized in Table 7.2.31

Table 7.2: Rate of Revenue Growth

Source: CFRA Stock Reports

In spite of the significant differences in dollar levels of revenue, the three companies had vastly different rates of growth (positive or negative). IBM declined each year, as reflected in both dollar amount and rate of growth. In fact, of the three, IBM’s rate was the largest decline reported. Adobe showed very little change from year to year, in a period of weakness in the sector. In that regard, their rate of growth was far better than that of IBM. And although Microsoft reported a decline in 2016, its overall rate of change in revenue was far stronger than its two competitors.

An analyst looking at the dollar values of revenue might conclude that as candidates for long-term growth, Adobe has a relatively small dollar level of revenue, and IBM has the strongest overall level; however, this would be a misleading conclusion. When dollar values are accompanied by an analysis of trends in the rate of growth, a more accurate picture emerges.

Earnings Trends

Trends in growth should not be restricted to revenue, but should include earnings as well. Only in this way can the importance of revenue growth by appreciated. If a company reports increases in revenue but losses in the same years, that is far from a positive outcome. At the same time, a decline in revenue accompanied by growth in earnings is a promising trend.

The study of earnings can be done on a percentage basis just as revenues can be; and you will gain greater insight into the trend by performing an analysis on this basis. Two formulas are involved in the analysis of earnings. The traditional rate of growth in earnings is calculated with this formula:

Formula: rate of growth in net earnings

(C – P) ÷ P = R

C = current year net earnings

P = past year net earnings

R = rate of growth in net earnings

Excel program

| A1 | current year net earnings |

| B1 | past year net earnings |

| C1 | =SUM(A1-B1)/B1 |

For example, current year earnings were reported at $16,798 million; past year was $12,193. The rate of change is:

($16,798 – $12,193) ÷ $12,193 = 37.8%

Using the same companies as those in the revenue example, the dollar value of traditional earnings is summarized in Table 7.3.

Table 7.3: Rate of Net Earnings Growth

Source: CFRA Stock Reports

The tracking of earnings presents a more volatile result that revenues. IBM reported a negative rate each year and Microsoft’s results were in double digits in three of the four years. However, the dollar value of earnings was nearly identical from the beginning to the end of the period. Adobe’s results point out a flaw in this type of analysis. The dollar values of earnings were so low that year-to-year changes were large on a percentage basis.

A more accurate rendition of earnings requires analysis of core earnings rather than reported net earnings. The formula for rate of growth in core earnings is:

Formula: rate of growth in core earnings

(CC – PC) ÷ PC = CE

CC = current year core earnings

PC = past year core earnings

CE = rate of growth in core earnings

Excel program

| A1 | current year core earnings |

| B1 | past year core earnings |

| C1 | =SUM(A1-B1)/B1 |

For example, current and past year earnings were reported as $16,798 million and $12,193 million. However, with core earnings adjustments, the core net earnings changed to $12,044 and $9,427. The result:

($12,044 – $9,427) ÷ $9,427 = 27.8%

There are substantial differences between reported earnings and core earnings in this example, a reduction of 10%. These types of analysis—using percentage changes and comparing reported revenues and earnings rather than changes in dollar amounts— provide the most meaningful conclusions of top-line and bottom-line change over time. This is the most reliable operating statement trend analysis, especially when the flaws in GAAP reporting are understood, and how those flaws distort the fundamental analysis itself.

Revenue Compared to Direct Costs and Expenses

Within the operating statement, you will find additional valuable information for selecting companies. To better understand the causes of trends in revenue and earnings, begin with an analysis of the relationship between revenue and gross profit. If the gross profit is inconsistent from year to year, you can expect to see a corresponding inconsistency in reported profits or losses.

Direct costs—expenditures that are relating specifically to generation of revenues—should remain a constant from year to year. The costs—including merchandise as the primary element—will change only due to changes in valuation methods for inventory; catastrophic inventory losses; or changes in the mix of business. A change can be brought about through mergers or as a consequence of selling off an operating segment. But assuming that none of those unusual events occur, you should be able to track direct costs and gross profit and see consistency from year to year.

When you deduct direct costs from revenue, you find the gross profit. The percentage of gross profit to revenue is called gross margin. The formula for checking the gross margin is:

Formula: gross margin

G ÷ R = M

G =gross profit

R = revenue

M = gross margin

Excel program

| A1 | gross profit |

| B1 | revenue |

| C1 | =SUM(A1/B1) |

For example, IBM reported revenues, direct costs and gross profit for three years as shown on Table 7.4.32

Table 7.4: IBM Annual Gross Margin

Source: IBM annual reports

The consistency of gross margin in this example makes the point that direct costs should not vary greatly from year to year. During this five-year period, revenue and gross profit changed significantly; but gross margin changed by just over 2% during the period.

The analysis becomes even more revealing when expenses are studied in relation to revenue, and when changes in expenses are reviewed on a percentage basis. The formula for rate of growth in expenses is:

Formula: rate of growth in expenses

(C – P) ÷ P = E

C = current year expenses

P = past year expenses

E = rate of growth in expenses

Excel program

| A1 | current year expenses |

| B1 | past year expenses |

| C1 | =SUM(A1-B1)/B1 |

For example, current expenses were $21,069 (million), and the past year’s expenses were $20,430. The formula:

($21,069 – $20,430) ÷ $20,430 = 3.1%

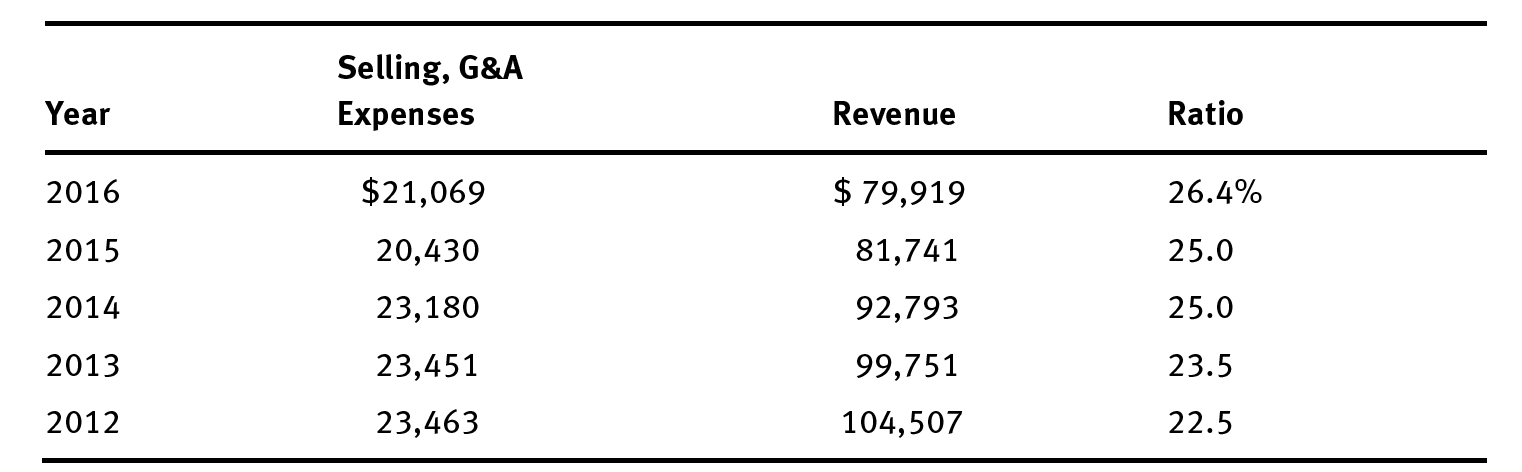

A five-year summary for IBM’s rate of growth in expenses is summarized in Table 7.5. 33

Table 7.5: IBM Annual Rate of Growth in Expenses

Source: IBM annual reports

The change between 2015 and 2014 was substantial, but otherwise it did move in a discernable trend. This leads to a conclusion that other than the one spike, expenses did not change much during the period, even when revenue and gross profit declined considerably. Gross profit fell from 2012 levels of $51,994 (million) to $38,294, a decrease of $13,700 (million). However, selling and general & administrative expenses declined in the same period from $23,463 (million) to $21,069, a decline of only $2,394 (million). The disparity in decline of gross profit versus the decline in expenses reveals a negative trend that would not be obvious other than through an analysis of expense trends.

The picture is not, complete, however. Expenses need to be further reviewed in comparison to revenue levels. This is likely to shed more light on the expenses trend. For this reason, expenses may be further analyzed through the formula for ratio of expenses to revenue, which is:

Formula: ratio of expenses to revenue

E ÷ R = P

E = expenses

R = revenue

P = ratio (percentage)

Excel program

| A1 | expenses |

| B1 | revenue |

| C1 | =SUM(A1/B1) |

For example, with annual expenses at $21,069 (million) and revenue at $79,919, the ratio of expenses to revenue is:

$21,069 ÷ $79,919 = 26.4%

In the case of IBM, this ratio for the five-year period is summarized in Table 7.6.34

Table 7.6: IBM Ratio of Expenses to Revenue

Source: IBM annual reports

Here, the negative trend in expenses is confirmed. The ratio rose from 22.5% in 2012 to 26.4% in 2016, revealing that as revenues declined through the period, expenses (which also declined on the basis of dollars) actually rose as a percentage of revenue.

A final level of analysis is based on the operating profit. The previous formulas show how the items between top and bottom are studied, and how they affect the overall results. The operating profit—assumed to be the profit from all continuing operations—is the number to watch when trying to quantify growth potential. The first of two formulas to study is the rate of growth in operating profit, which is not the same as the previously introduced rate of growth in net earnings. That formula includes all other income and expenses and is normally based on the after-tax profit. Operating profit (also called profit from continuing operations before income taxes) is limited to earnings from operations and is computed by the following formula:

Formula: rate of growth in operating profit

(C – P) ÷ P = R

C = current year operating profit

P = past year operating profit

R = rate of growth in operating profit

Excel program

| A1 | current year operating profit |

| B1 | past year operating profit |

| C | =SUM(A1-B1)/B1 |

For example, current year operating profit was $12,330 (million) and past year’s was $15,945. The negative rate of growth was:

($12,330 – $15,945) ÷ $15,945 = –22.7%

IBM’s operating profit over a five-year period is summarized in Table 7.7.35

Table 7.7: IBM Annual Growth in Operating Profit

| Operating | Annual | |

| Year | Profit | Growth |

| 2016 | $12,330 | -22.7% |

| 2015 | 15,945 | -20.2 |

| 2014 | 19,986 | - 1.3 |

| 2013 | 20,244 | -10.2 |

| 2012 | 22,540 | -- |

Source: IBM annual reports

The annual declines, in double digits for three of the four years between 2013 and 2016, further confirms the negative long-term trend in earnings.

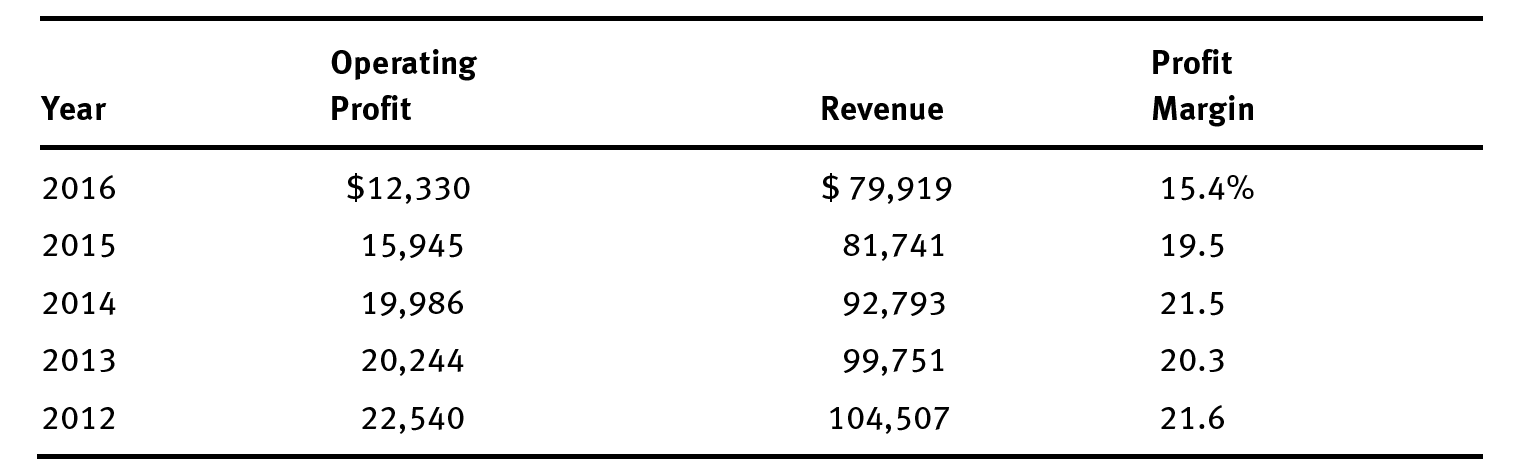

An additional formula is equally important for long-term trend watching. This is the operating profit margin, which is computed as:

Formula: operating profit margin

E ÷ R = M

E = expenses

R = revenue

M = operating profit margin

Excel program

| A1 | expenses |

| B1 | revenue |

| C1 | =SUM(A1/B1) |

For example, the latest year’s operating profit was $12,330 (million) versus revenue of $79,919 (million). The profit margin was:

$12,330 ÷ $79,919 = 15.4%

IBM’s five-year operating profit margin is summarized in Table 7.8.36

Table 7.8: IBM Annual Operating Profit Margin

Source: IBM annual reports

The consistent annual decline in margin further reveals the weakness in the profit trend reported by IBM. Only through calculating the ratios over a period of time can the direction of the trend be recognized.

The evaluation of these many versions of “income,” “profits,” and “earnings” demonstrates that the many terms only confuse the issue of determining whether the trend is positive or negative. Just reviewing the dollar values is not enough. True insight is possible only with a series of analyses over time. The accounting industry is a passive and reactive culture; it is not in their interests to improve the terminology used in financial reporting, although it should be. Ultimately, it will be up to corporate leaders to achieve true transparency. However, in annual reports, companies rarely disclose the negative trends in clarified, honest language. The tendency is to focus on segments where improvement has taken place and to downplay the negative trends seen only through year-to-year analysis.

As an investor, you ensure that your comparisons are truly valid by following these guidelines:

- Study the terminology to ensure that you’re using comparable values. Not every company uses the same phrasing for the various levels on the operating statement. One may refer to net income, another to income from continuing operations. But are these truly comparable? The value used affects not only return on sales, but also PE ratio and EPS, among the important ratios popularly followed.

- Remove non-core income and add excluded expenses to reported earnings to ensure accuracy. The inclusion of non-core income or exclusion of core expenses is a significant problem in the accounting/auditing culture and in the corporate reporting culture as well. Unfortunately, the reporting formats considered official and correct are unreliable and misleading. You need to seek out the true core earnings from operations to develop reliable long-term trends.

- Pay close attention to the differences between reported and core earnings You will discover in reviewing the long-term trends for many companies that there is a close relationship between core earnings adjustments and volatility (both in revenues and stock prices). As a general rule, companies with relatively high core earnings adjustments are also going to experience higher than average stock price volatility. Conversely, those with low core earnings adjustments will be far less volatile. Rather than simply accepting reported net earnings, use the core earnings value as the most reliable indicator of where earnings are leading into the future.

Conclusion

The relationship between the fundamentals and a stock’s price volatility is direct. The two camps (fundamental and technical) complement one another, and should not be thought of as different or separate. The next chapter provides you with valuable market trend formulas that can be used, along with fundamental tests, to evaluate risks and to pick stocks.