3

ESTABLISHING KNOWLEDGE: INSTITUTIONS OLD AND NEW

In the customs and institutions of schools, academies, colleges and similar bodies destined for the abode of learned men and the cultivation of learning, everything is found adverse to the progress of knowledge.

Bacon

Gutenberg war nicht Privatdozent, Columbus nicht ordinarius.

(Gutenberg was not a university teacher, or Columbus a professor.)

Schöffler

ACCORDING to Karl Mannheim, as we have seen (above, 5), the beliefs of the ‘free-floating intelligentsia’ (freiscbwebende Intelligent) are less subject to social pressures than the beliefs of other groups. This statement provoked the reply from the economist Josef Schumpeter that Mannheim’s intellectual was just ‘a bundle of prejudices’.1 Whether or not this is the case, we certainly need to take note of the fact that most of the early modern clerisy, like modern intellectuals, did not float completely freely but were attached to institutions, such as universities. The institutional context of knowledge is an essential part of its history.2 Institutions develop social impulses of their own as well as being subject to pressures from outside. The drive to innovate and the opposite drive to resist innovation are of particular relevance to this study of the social history of knowledge.

Before turning to early modern Europe, it may be illuminating to introduce two general theories into the discussion, concerned respectively with the sociology of intellectual innovation and of cultural reproduction. The first, associated with Thorstein Veblen (above, 3), focuses on outsiders, on individuals and groups at the margin of society. In his essay on ‘the intellectual pre-eminence of Jews in modern Europe’, Veblen explained this pre-eminence, as we have seen, by the position of Jewish intellectuals on the border of two cultural worlds, a position which encouraged scepticism and detachment and so fitted them to become what another sociologist, the Italian Vilfredo Pareto, called intellectual ‘speculators’.3

Pareto contrasted these speculators with the opposite social type, the intellectual ‘rentiers’ who work within the framework of a tradition. The second theory, associated with Pierre Bourdieu, is concerned with the production of rentiers of this kind by academic institutions and with the tendency of these institutions to reproduce themselves, building up and transmitting what he calls ‘cultural capital’. In other words, they develop ‘vested interests’. A similar point was made by Norbert Elias in terms of ‘establishments’. In a short but penetrating essay, Elias described academic departments as having ‘some of the characteristics of sovereign states’, and went on to analyse their competition for resources and their attempts to set up monopolies and to exclude outsiders.4 Similar strategies of monopolization and exclusion can be seen in the history of the professions – the clergy, lawyers and physicians, joined in the nineteenth century by engineers, architects, accountants and so on.

It would of course be unwise to assume that these two theories, which appear to fit together rather neatly, are universally applicable without qualification. All the same, it may be useful to keep them in mind in the course of this brief examination of the organization of learning between 1450 and 1750.

For the later Middle Ages, the theory of Bourdieu and Elias seems to work quite well. As we have seen, the rise of cities and the rise of universities occurred together in Europe from the twelfth century onwards. The model institutions of Bologna and Paris were followed by Oxford, Salamanca (1219), Naples (1224), Prague (1347), Pavia (1361), Cracow (1364), Leuven (1425) and many more. By 1451, when Glasgow was founded, about fifty universities were in operation. These universities were corporations. They had legal privileges, including independence and the monopoly of higher education in their region, and they recognized one another’s degrees.5

At this time it was assumed rather than argued that universitiesought to concentrate on transmitting knowledge as opposed to discovering it. In similar fashion, it was assumed that the opinions and interpretations of the great scholars and philosophers of the past could not be equalled or refuted by posterity, so that the task of the teacher was to expound the views of the authorities (Aristotle, Hippocrates, Aquinas and so on). The disciplines which could be studied, officially at least, were fixed: the seven liberal arts and the three postgraduate courses in theology, law and medicine.

Despite these assumptions, debate was encouraged, especially the formal ‘disputation’, an adversarial system like a court of law in which different individuals defended or opposed a particular ‘thesis’. The example of Thomas Aquinas is a reminder that it was possible for ‘moderns’ to become authorities in their turn, even if Aquinas did this by producing a synthesis of elements from different traditions rather than by offering something completely new. The strength of the opposition to Aquinas’s use of the pagan thinker Aristotle in his discussion of theology shows how mistaken it would be to describe these institutions purely in terms of intellectual consensus. So do the controversies between different philosophical schools in later medieval universities, notably the conflicts between ‘realists’ and ‘nominalists’. Indeed, in the early modern period medieval universities were criticized not as too consensual but as too disputatious. All the same, the protagonists in these debates shared so many assumptions that their controversies were generally limited to a few precise topics such as the logical status of general statements or ‘universals’.6

As we have seen in chapter 2, in medieval Europe university teachers were almost all clerics. The relatively new institution of the university, which developed in the twelfth century, was embedded in a much older institution, the Church. No wonder that it is common to describe the medieval Church as having exercised a monopoly of knowledge.7 All the same, as was noted in chapter 1, we should not forget the plurality of knowledges, in this case the different knowledges of medieval artisans (who had their own training institutions, their workshops and guilds), of knights, of peasants, of midwives, housewives and so on. All these knowledges were transmitted mainly by word of mouth. However, by the time of the invention of printing, lay literacy already had a long history in western Europe (in eastern Europe, by contrast, where the religion was Orthodox Christian and the script Cyrillic, lay literacy was relatively rare). Heretics, who multiplied at about the same time as the universities, have been described as ‘textual communities’, held together by their discussions of ideas written down in books.8

The diversity of knowledges, sometimes in competition and conflict, helps to explain intellectual change. However, important questions remain open. Did heretics and other outsiders ever enter the intellectual establishment? If so, how did this happen? Were the changes which were made in the system official or unofficial? Were they the result of intellectual persuasion or political alliances? Did intellectual innovation lead to the reform of institutions, or did new institutions have to be founded to provide ecological niches in which such innovation could flourish?9 These questions were sometimes discussed in the period itself, notably by Francis Bacon. Like Louis XIV’s minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert a generation later (below, 129), Bacon was extremely conscious of the importance in the history of learning of material factors such as buildings, foundations and endowments. So were his English followers in the middle of the seventeenth century, who were fertile in projects for what they called the ‘reformation of learning’.10

The following sections will examine three centuries of intellectual change, focusing on three of the major cultural movements of the period – the Renaissance, the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment – paying particular attention to the place of institutions in the process of intellectual innovation, whether they are to be viewed as helps or as hindrances. The invention and establishment of new disciplines will be discussed in more detail in chapter 5 (below, 99) as part of a later reclassification of knowledge.

THE RENAISSANCE

The humanist movement associated with the Renaissance was at least in intention a movement not of innovation but of revival, the revival of the classical tradition. Nonetheless this movement was innovative, and self-consciously so, in the sense of opposing much of the conventional wisdom of the ‘scholastics’, in other words the philosophers and theologians who dominated the universities of the ‘Middle Ages’. The very terms ‘scholastics’ and ‘Middle Ages’ were inventions of the humanists of this time, in order to define themselves more clearly by contrast to the past.

The majority of the humanists had studied at the universities they criticized. All the same, it is noticeable that some of the most creative individuals spent much of their lives outside the system. Petrarch, for instance, was a wandering man of letters. Lorenzo Valla left the University of Pavia under a cloud after criticizing the intellectual ‘authorities’, and entered the service of the king of Naples and later of the pope. Leonardo Bruni was the chancellor of Florence, writing letters on behalf of the republic. Marsilio Ficino was a physician in the service of the’ Medici. Even more creative and even more marginal was Leonardo da Vinci, who had been trained as a painter and became a self-taught universal man. Outside Italy, the most famous humanist of all, Erasmus, refused to stay very long at any university, despite many offers of permanent employment from Paris to Poland.

The humanists developed their ideas in discussion, but their debates took place not so much in the environment of universities, where longer-established groups were often hostile to new subjects, as in a new kind of institution they created for themselves, the ‘academy’. Inspired by Plato, the academy was closer to the ancient symposium (drinking included) than to the modern seminar. More formal and longer-lasting than a circle (Petrarch’s disciples, for example), but less formal than a university faculty, the academy was an ideal social form in which to explore innovation. Little by little these groups turned into institutions, with fixed memberships, statutes and regular times of meeting. By the year 1600 nearly 400 academies had been founded in Italy alone, while they could also be found in other parts of Europe, from Portugal to Poland.11

Discussions of ideas were no monopoly of academics. In early fifteenth-century Florence, as we have seen (above, 15) the humanist Leonbattista Alberti had frequent conversations with the sculptor Donatello and the engineer Filippo Brunelleschi. Another member of Alberti’s circle was the mathematician Paolo Toscanelli, whose interests included geography, especially routes to the Indies. Toscanelli obtained information on this subject from questioning travellers who passed through Florence after their return to Europe, and he may have been in touch with Columbus.12

What Toscanelli was doing informally was done more officially in Portugal and Spain. In fifteenth-century Portugal, information as well as goods coming from Asia found its way to ‘India House’ in Lisbon (A Casa da India). In Seville, the ‘House of Trade’ (La Casa de Contratación), founded in 1503, was a similar store of knowledge about the New World. It was also a training school for pilots, under the direction of the piloto mayor (at one time Amerigo Vespucci, and later Sebastian Cabot). Instruction was sometimes given in the pilot’s home, sometimes in the chapel of the Casa. The first school of navigation in Europe, it soon acquired an international reputation (as an English visitor in 1558, the pilot Stephen Borough, bears witness).13

Royal support was crucial in the establishment of the Houses of India and of Trade, and of other institutions as well. In Paris in the early sixteenth century, the humanists, opposed by the Faculty of Theology, appealed to King François I, who founded the Collége des Lecteurs Royaux to encourage the study of Greek and Hebrew. Later in the century. King Henri III was the patron of a palace academy in which lectures were given on the ideas of Plato (a link with the so-called ‘Platonic Academy’ of Florence).14

Royal support was also important to humanists because they met with opposition in some intellectual circles. The strength of the opposition varied from university to university. It was strong in early sixteenth-century Leipzig, for instance, and also in Oxford, where a group hostile to the study of Greek became known as the ‘Trojans’. That opposition to humanism was less vigorous in newer institutions, which were free, for a time at least, from the pressure to do what had ‘always’ been done in the past, is suggested by the cases of the new universities of Wittenberg, Alcalà and Leiden.15

Wittenberg, which was founded in 1502, was originally organized on fairly traditional lines by scholars who had themselves been trained at Leipzig and Tubingen. However, within five or six years the humanists had come to play an unusually important role in the university. It is probably easier for would-be innovators to take over new institutions than old ones, so it may be no accident that the Reformation was launched by Professor Luther at a time when his university was only fifteen years old. A year later, Philip Melanchthon was appointed professor of Greek, with the approval of Luther and other members of faculty, as part of a programme of reform. His reform of the arts curriculum was taken as a model by teachers in the Protestant universities of the later sixteenth century, such as Marburg (founded 1527), Koenigsberg (1544), Jena (1558) and Helmstedt (1576), new institutions in which there were fewer traditions and less hostility to humanism than elsewhere.16

Alcalà opened six years later than Wittenberg, in 1508. Its foundation cannot be interpreted as a triumph of humanism, since the university was consciously modelled on Paris and staffed by old Paris men or Salamanca men.17 However, as at Wittenberg, the balance between humanism and scholasticism had shifted to the advantage of the former. A ‘trilingual’ college was founded at Alcalà to encourage the study of the three biblical languages, Latin, Greek and Hebrew, a few years before the foundation of a similar college in the older university of Leuven in 1517. It was at Alcalà that the famous polyglot edition of the Bible was edited and printed between 1514 and 1517, the work of a team of scholars including the famous humanist Antonio de Mebrija.18

Unlike Wittenberg and Alcalà, Leiden was founded (in 1575) for essentially ideological reasons, as a Calvinist university. The first president of the board of governors, Janus Dousa, built up the university by methods which have become familiar in our own century, making offers of high salaries and low teaching loads in order to attract distinguished scholars, including the botanists Rembert Dodoens and Charles de l’Ecluse and the classicist Joseph Scaliger. Leiden was not new in its formal structure, but two relatively new arts subjects, history and politics, quickly acquired an unusually important position there. History was taught by a leading humanist, Justus Lipsius. Quantitatively speaking, politics was an even greater success; there were 762 students of politics at Leiden between 1613 and 1697.19

The point of these examples is not to argue that all teachers in new universities are innovators, and still less that new ideas are a monopoly of new institutions. It was not the universities but certain groups within certain universities who were hostile to humanism. The foundation of chairs of rhetoric in Leuven (in 1477) and Salamanca (in 1484) indicates sympathy with the studia humanitatis, like the lectureships in history founded in Oxford and Cambridge in the early seventeenth century. The ideas of the humanists gradually infiltrated the universities, especially in the sense of influencing the unofficial curricula rather than the official regulations.20 By the time this happened, however, the most creative phase of the humanist movement was over. The challenge to the establishment now came from ‘the new philosophy’, in other words from what we call ‘science’.

THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION

The so-called ‘new philosophy’, ‘natural philosophy’ or ‘mechanical philosophy’ of the seventeenth century was an even more self-conscious process of intellectual innovation than the Renaissance, since it involved the rejection of classical as well as medieval traditions, including a world-view based on the ideas of Aristotle and Ptolemy. The new ideas were associated with a movement generally known (despite growing doubts about the appropriateness of this label), as the Scientific Revolution.21 Like the humanists, but on a grander scale, the supporters of this movement tried to incorporate alternative knowledges into learning. Chemistry, for instance, owed a good deal to the craft tradition of metallurgy. Botany developed out of the knowledge of gardeners and folk healers.22

Although some leading figures in this movement worked in universities – Galileo and Newton among them – there was considerable opposition to the new philosophy in academic circles (a major exception, but one which fits the general argument, is that of the new university of Leiden, which became a major centre of innovation in medicine in the seventeenth century).23 In reaction to the opposition, supporters of the new approach founded their own organizations, societies such as the Accademia del Cimento in Florence (1657), the Royal Society of London (1660), the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris (1666), and so on, organizations reminiscent in many ways of the humanist academies but placing more emphasis on the study of nature.

The argument that the hostility of the universities to the new philosophy led to the creation of ‘scientific societies’ as an alternative institutional framework was put forward by Martha Ornstein in a book published in 1913 (above, 9). According to Ornstein, ‘with the exception of the medical faculties, universities contributed little to the advancement of science’ in the seventeenth century. The claim has often been reiterated.24 In the case of England, for example, historians have linked the foundation of the Royal Society to the criticisms of Oxford and Cambridge put forward in the middle of the seventeenth century by William Dell, John Webster and others.25 Webster, for example, who was active as a surgeon and an alchemist as well as as a clergyman, criticized the universities in his Examination of Academies (1654) as strongholds of a scholastic philosophy concerned with ‘idle and fruitless speculations’, and suggested that students should spend more time on the study of nature and ‘put their hands to the coals and furnace’. It has often been pointed out that there was no chair of mathematics at Cambridge until 1663.

The traditional view that universities opposed the ‘new philosophy’ or at least did little to further it is one which has come under fire in a series of studies published from the late 1970s onwards. Their authors argue that the study of mathematics and natural philosophy had an important place in universities and that contemporary criticisms of universities were either ill-informed or deliberately misleading. In the case of Oxford, the foundation of chairs of astronomy and geometry in 1597 and 1619 has often been noted. The interest in new ideas in university circles has been emphasized. The views of Descartes were sometimes discussed at the university of Paris, for example, those of Copernicus at Oxford and those of Newton at the university of Leiden. As for the critique of the universities by contemporaries, it has been pointed out that the Royal Society was concerned to make publicity and to generate support for itself, while Dell and Webster, both of whom were radical Protestants, also had their own agenda, so that their remarks cannot be taken at face value.26

As the dust settles on the controversy, it is becoming increasingly clear that any simple opposition between progressive academies and reactionary universities is misleading. It is difficult to measure the relative importance of universities and other institutions, since a number of scholars belonged to both. As so often in this kind of debate, what are needed are distinctions – between different universities, different moments, different disciplines, and, not least, between different questions – whether the universities failed to originate the new ideas, or were slow to disseminate them, or actively opposed them.27 Despite these problems, it seems possible to reach a few provisional conclusions.

In the first place, as in the case of the humanist movement, the proliferation of new forms of institution gives the impression that a considerable number of supporters of the movement to reform natural philosophy themselves perceived the universities as obstacles to reform, at least in that movement’s early stages. These locales offered appropriate micro-environments or material bases for the new networks, small groups or ‘epistemological communities’ which have so often proved to play an important role in the history of knowledge (above, chapter 1).

In the second place, distinctions between these new forms of institution are in order. Some of them were founded within the universities themselves, botanical gardens for example, anatomy theatres, laboratories and observatories, all of which were islands of innovation within more traditional structures. The new university of Leiden had a botanical garden by 1587, an anatomy theatre by 1597, an observatory by 1633 and a laboratory by 1669. The relatively new university of Altdorf acquired its garden in 1626, its anatomy theatre in 1650, its observatory in 1657 and its laboratory in 1682.

Some institutions were founded from below, by a group of like-minded people who formed a society, like the natural philosophers or ‘Lynxes’ (Lincei) in seventeenth-century Rome, or an individual who turned part of his house into a museum or ‘cabinet of curiosities’ which might display stones or shells or exotic animals (alligators, for example) or ‘sports of nature’. The rise of museums of this kind in the seventeenth century is a clear indication of the spread of a less logocentric conception of knowledge, a concern with things as well as words of the kind recommended by the Czech educational reformer Jan Amos Comenius (below, 85).28

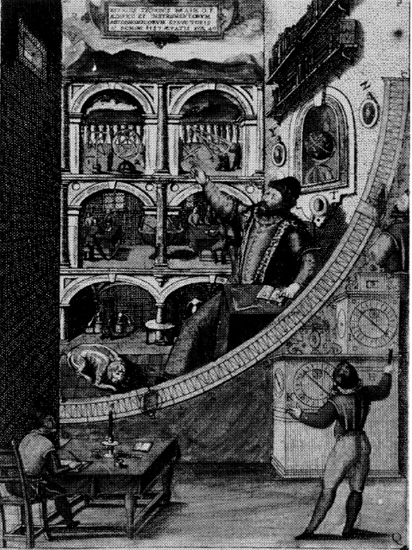

Other institutions were called into existence from above, by governments, whose resources were necessary for large-scale projects and expensive equipment. The astronomer Tycho Brahe’s famous observatory on the island of Hveen (figure 1) was founded (in 1576) and funded by the king of Denmark. The French Academy of Sciences was another royal foundation. The Paris Observatory (1667) was funded by Louis XIV, and the Royal Observatory at Greenwich (1676) by Charles II, to compete with his powerful rival.

The courts of princes themselves offered some opportunities for the practice of natural philosophy, as in the case of Prague in the time of the Emperor Rudolf II (himself fascinated by these studies), or Florence in the age of Grand Duke Cosimo II. An innovative projector such as Johann Joachim Becher, whose interests included alchemy, mechanics, medicine and political economy, was more at home in the world of the court of Vienna in the mid-seventeenth century than he would have been in any university of the time.29 Yet these opportunities sometimes had their price. Galileo had to play the courtier in Florence, while the French Academy of Sciences was encouraged by the government to turn away from ‘curious’ research, dismissed as a ‘game’, to ‘useful research which has some connection with the service of the king and of the state’.30

Again, some new institutions were exclusive, like the Academy of Sciences and to a lesser degree the Royal Society, while others had the function of widening the public for the new ideas. In London, for example, the lectures at Gresham College, which began in the early seventeenth century, were open to all, and most of them were delivered in English, not the Latin customary at the universities. In Paris, Théophraste Renaudot organized lectures on a wide variety of subjects for a wide public at his Bureau d’Adresse from 1633 onwards. The Royal Garden in Paris, which opened to the public in 1640, offered them lectures on anatomy, botany and chemistry.31

1 ENGRAVING, THE OBSERVATORY AT HVEEN, FROM TYCHO BRAHE, ASTRONOMIAE INSTAURATAE MECHANICA (1598)

The interest in the so-called ‘mechanical philosophy’ shown by the groups and organizations discussed in the last few paragraphs, and the success of this philosophy in the eighteenth century, should not lead us to forget the rival, ‘occult philosophy’. An increasing concern with the occult was another form of innovation in the early modern period, a concern visible at some courts (notably that of Rudolf II) but one which also generated its own institutions, asociations like the Rosicrucians, a secret society concerned with secret knowledge.

The new institutions discussed in the preceding paragraphs were not limited to the domain of natural philosophy. The Royal Society, for example, in their instructions for travellers (below, 202) were concerned not only with the fauna and flora of different parts of the world but with the customs of the inhabitants. When Leibniz planned a German learned society around 1670, he referred to the Royal Society and the Academy of Sciences as models but placed more emphasis than they did on what he called res litteraria, in other words the humanities. Museums and cabinets of curiosities generally contained not only shells and stuffed animals but Roman coins or objects from distant places such as China or Mexico. A number of the most famous learned societies of the seventeenth century were concerned with language, notably the Crusca of Florence (which brought out a dictionary in 1612), the German Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft (founded in 1617) and the Académie Française (1635). So were the more informal salons which flourished in Paris from about 1610 to 1665 under the patronage of aristocratic intellectual ladies at the Hotel de Rambouillet and elsewhere.32

Other societies were concerned with history, like the Society of Antiquaries (founded in the 1580s) in London or the Antikvitetskollegiet at Uppsala (1666). Libraries as well as laboratories sometimes became meeting-places for scholars. The convents of religious orders sometimes became the setting for collective scholarly projects, such as the lives of the saints written by the Bollandists in the Jesuit house in Antwerp or the ambitious historical works produced by the Maurists in the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the setting for weekly discussions sometimes described as an ‘academy’.33

What was common to these new ‘seats and places of learning’, as Bacon called them (or ‘seats of knowledge’, in the words of the Baconian Thomas Sprat, the historian of the Royal Society), was the fact that they provided opportunities for innovation – for new ideas, new approaches, new topics – and also for innovators, whether or not they were academically respectable. The encouragement of discussion in these places also deserves to be emphasized. Intellectual debates owe a good deal to the forms of sociability and so to the social frameworks in which they take place, from the seminar room to the café. In early modern Europe, learned societies helped create a collective identity for the clerisy and encouraged the development of intellectual communities, both the smaller and more intimate face-to-face groups and the wider community of the Republic of Letters (above, 19), linked by visits and especially by correspondence. In short, what has been called ‘the importance of being institutionalized’ should not be forgotten.34

THE ENLIGHTENMENT

From an institutional point of view,-the eighteenth century marks a turning-point in the history of European knowledge in a number of respects. In the first place, the virtual monopoly of higher education enjoyed by the universities was challenged at this time. In the second place, we see the rise of the research institute, the professional researcher and indeed of the very idea of ‘research’. In the third place, the clerisy, especially in France, were more deeply involved than ever before with projects for economic, social and political reform – in other words, with the Enlightenment. These three points need to be discussed in more detail, one by one.

Some alternative institutions for higher education already existed in 1700. Although artists continued to receive much of their training in workshops, the instruction they provided was increasingly supplemented by attendance at academies in Florence, Bologna, Paris and elsewhere. Academies for noble boys to learn mathematics, fortification, modern languages and other skills considered useful for their future careers in the army or in diplomacy had been founded in Sorø (1586), Tubingen (1589), Madrid (1629) and elsewhere. Academies or quasi-universities for French Calvinists had been founded in Sedan and Saumur around 1600 and played an important part in intellectual life until their suppression in 1685. In Amsterdam the Athenaeum (founded in 1.632) emphasized new subjects such as history, and botany.

It was in the eighteenth century, however, that these initiatives multiplied. Academies for the arts were founded in Brussels (1711), Madrid (1744), Venice (1756) and London (1768). New noble academies were founded in Berlin (1705) and in many other places. Between 1663 and 1750 nearly sixty academies for ‘Dissenters’ from the Church of England, who were excluded from Oxford and Cambridge, were founded in or near London and in a number of provincial towns such as Warrington in Lancashire (where one of the teachers was the natural philosopher Joseph Priestley).

The Dissenting academies taught a less traditional curriculum than the universities, designed for future businessmen rather than gentlemen, paying attention to modern philosophy (the ideas of Locke, for example), natural philosophy and modern history (a common textbook was the political history of Europe by the German lawyer Samuel Pufendorf). Teaching sometimes took place in English rather than Latin.35 In central Europe, colleges such as the Karlschule at Stuttgart were founded to teach the art of government to future officials. New institutions, the equivalent of later colleges of technology, were also founded to teach engineering, mining, metallurgy and forestry; the Collegium Carolinum in Kassel, for example, founded in 170.9, the engineering academies of Vienna (1717) and Prague (1718), the forestry school founded in the Harz mountains in 1763 and the mining academies of Selmecbánya in Hungary and Freiberg in Saxony (1765).

The second important development in the eighteenth century was the founding of organizations to foster research. The word ‘research’ (recherche, ricerca, etc), is of course derived from ‘search’ and it can already be found in book titles in the sixteenth century, including Etienne Pasquier’s Recherches de la France (1560). The term was used more in the plural than the singular and it became more common from the end of the seventeenth century, and more common still at the end of the eighteenth, whether to refer to the arts or the sciences, historical or medical studies. Together with the word ‘research’, other terms came into more regular use, notably ‘investigation’ (and its Italian equivalent indagine), which widened out from its original legal context, and ‘experiment’ (in Italian cimento), which narrowed down from tests in general to the testing of laws of nature in particular. Galileo’s famous-pamphlet Il Saggiatore used the metaphor of ‘assaying’ in a similar sense.

Taken together, this cluster of terms suggests an increasing awareness in some circles of the need for searches for knowledge to be systematic, professional, useful and co-operative. The Florentine Accademia del Cimento published anonymous accounts of its experiments, as if concerned with what the sociologist Auguste Comte would later call ‘history without names’ (above, 3). For all these reasons one might speak of a shift around the year 1700 from ‘curiosity’ to ‘research’, summed up in a memorandum of Leibniz, recommending the establishment of an Academy in Berlin but defining its purpose in contrast to mere curiosity (Appetit zur Curiosität). This sense of research was connected with the idea that the stock of knowledge was not constant in quality or quantity but could be ‘advanced’ or ‘improved’, an idea discussed in more detail below.

There is an obvious link between this awareness and the development of organizations to foster research. Bacon’s famous vision of ‘Solomon’s House’ in his philosophical romance New Atlantis (1626), described a research institute with a staff of thirty-three (not counting assistants), divided into ‘merchants of light’ (who travelled in order to bring back knowledge), observers, experimenters, compilers, interpreters and so on. Something like this, on a more modest scale, already existed in a few places in Europe. Bacon’s vision may owe more than is generally recognized to the Academy of the Lincei in Rome, of which Galileo was a member; to Tycho Brahe’s observatory at Uraniborg, with its complex of buildings and assistants; or to the House of Trade in Seville (above, 36), where data were collected and charts updated.

In turn, Bacon’s description probably stimulated change in institutions. The Royal Society, full of admirers of Bacon, hoped to establish a laboratory, an observatory and a museum. It also funded the research of Robert Hooke and Nehemiah Grew by collecting subscriptions. On a grander scale, Louis XIV’s minister Colbert spent 240,000 livres on research within the framework of the Academy of Sciences, partly in the form of salaries to certain scholars, the pensionnaires, to allow them to carry out collective projects such as a natural history of plants.36

These initiatives of the 1660s were taken further in the eighteenth century, the age of academies, generally supported by rulers, which paid salaries to savants to conduct their investigations, allowing them to pursue at least part-time careers outside the universities. The professional scientist of the nineteenth century emerged from a semi-professional tradition. Some seventy learned societies concerned wholly or partly with natural philosophy were founded in the eighteenth century, of which the Academies of Berlin, St Petersburg and Stockholm (Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademie) were the most famous, while the French Academy of Sciences was reorganized in 1699. With a vigorous president (such as Banks in London or Maupertuis in Berlin), or an active secretary (such as Formey in Berlin or Wargentin in Stockholm), there was much that these societies could achieve. They organized knowledge-gathering expeditions (below, 129), offered prizes, and increasingly formed an international network, exchanging visits, letters and publications and on occasion carrying out common projects, thus participating in the ‘trade’ in learning recommended by Leibniz, einen Handel und Commercium mit Wissenschaften.37

This increasingly formal organization of knowledge was not confined to the study of nature. Monasteries, especially Benedictine monasteries, following the example of the late seventeenth-century Maurists but placing greater stress on collective research, became important seats of historical learning in France and in the German-speaking parts of Europe in the eighteenth century.38 Leibniz suggested that one of the tasks of the new Academy of Berlin should be historical research. Research of this kind was taken seriously in a number of French provincial academies as well as in German ones. It was also funded by the government in the form of salaries for members of the Paris Academy of Inscriptions, reorganized in 1701 according to the model of the Academy of Sciences.39 Academies for the study of politics were founded in Paris by the foreign minister, the marquis de Torcy (1712) and in Strasbourg by a professor, Johann Daniel Schöpflin (c.1757).40 Research, including historical research, was important in the new university of Göttingen, founded in the 1730s.

The eighteenth century was a great age for voluntary associations of many kinds, many of them devoted to the exchange of information and ideas, often in the service of reform. Three examples from the British Isles may serve to exemplify the rising interest in useful knowledge: the Dublin Society for the Improvement of Husbandry (1731); the London Society of Arts (1754), founded to encourage trade and manufactures; and the Lunar Society of Birmingham (1775), which exchanged scientific and technical information.41 The rise of masonic lodges in London, Paris and elsewhere in the early eighteenth century illustrates this new trend as well as an older tradition of secret knowledge.

Even less formal organizations such as the salon and the coffeehouse had a part to play in the communication of ideas during the Enlightenment, In Paris, the salons have been described as the ‘working spaces of the project of Enlightenment’. Under the direction of Madame de Tencin, for example, Fontenelle, Montesquieu, Mably and Helvétius met for regular discussions, while Mme de L’Espinasse played hostess to d’Alembert, Turgot and other members of the group which produced the Encyclopédie.42 Coffee-houses played an important role in Italian, French and British intellectual life from the late seventeenth century onwards. Lectures on mathematics were given at Douglas’s and the Marine Coffee-House in London, while Child’s was for booksellers and writers, Will’s for the poet John Dryden and his friends, and French Protestant refugees congregated in the Rainbow. In Paris, Procope’s, founded in 1689, served as a meeting-place for Diderot and his friends. The proprietors of coffee-houses often displayed newspapers and journals as a way of attracting clients, and thus encouraged public discussion of the news, the rise of what is often called ‘public opinion’ or ‘the public sphere’. These institutions facilitated encounters between ideas as well as between individuals.43

The press, especially the periodical press, may also be regarded as an institution, and one which made an increasingly important contribution to intellectual life in the eighteenth century, contributing to the spread, the cohesion and the power of the imagined community of the Republic of Letters. No fewer than 1,267 journals in French are known to have been founded between 1600 and 1789, 176 of them between 1600 and 1699 and the rest thereafter.44

To sum up so far, the example of the institutions of learning in early modern Europe appears to confirm both the ideas of Bourdieu on cultural reproduction and those of Veblen on the link between marginality and innovation. The universities may have continued to perform their traditional function of teaching effectively, but they were not, generally speaking, the locales in which new ideas developed. They suffered from what has been called ‘institutional inertia’, maintaining their corporate traditions at the price of isolation from new trends.45

Over the long term, what we see are cycles of innovation followed by what Max Weber used to call ‘routinization’ (Veralltäglichung) and Thomas Kuhn described as ‘normal science’. In Europe, these cycles are visible from the twelfth century, when new institutions called universities replaced monasteries as centres of learning, to the present. The creative, marginal and informal groups of one period regularly turn into the formal, mainstream and conservative organizations of the next generation or the next-but-one. This is not to say that the reform or renewal of traditional organizations is impossible. The new role played by a very old institution, the Benedictine monastery, in the organization of research in the eighteenth century (above, 43, 47) is proof to the contrary. In similar fashion, in the reorganization of research in the nineteenth century, it would be the universities, especially in Germany, which would recover the initiative and leap ahead of the academies.

CONCLUSIONS AND COMPARISONS

Are these cycles of creativity and routinization a universal phenomenon, or are they confined to some periods in the history of the West? An obvious comparison is that between the early modern European system and the system of madrasas in the Muslim world, especially in Baghdad, Damascus and Cairo in what westerners call the ‘Middle Ages’ and in the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Although there are no clergy in Islam, the madrasas, teaching institutions attached to mosques, look remarkably like the Church-dominated educational institutions of Europe. The main subjects studied were the Quran, the Hadith (the sayings of the Prophet) and the law of Islam. The khans in which the students lived, the salaries of professors, the stipends of students and the tax-exempt foundations or wakfs which supported the system are all reminiscent of the college system which still exists in Oxford and Cambridge, and they may have influenced that system in the twelfth century. The formal organization of argument in the munazara resembled the western disputation, while the ijaza or licence to teach which a master gave his students resembled the medieval European licentia docendi.46

The historian who drew these parallels and raised the possibility of conscious western borrowing from the Muslims did not deny the existence of major differences between the two systems. However, more recent research suggests that he overemphasized the formal organization of knowledge and education in the Middle East, and that the ‘system’ – if one should call it that – was a fluid one. The ijaza was a personal licence, not a degree from an institution. What mattered in the career of a teacher was not where one had studied, but with whom. The central place of learning was an informal study circle (halqa), actually a semicircle at a respectful distance from the master (shaykh), whether in his house or in a mosque. There was no fixed curriculum. The students moved from master to master as they pleased. Indeed, even the term ‘student’ is not always appropriate since some members of study-circles attended part-time, including women. No wonder that a recent historian of the madrasa speaks of ‘persistent informality’.47

The contrast between the Christian and Muslim educational worlds must not be drawn too sharply. Western universities were less formal in early modern times than they became after 1800.48 All the same, the protracted Islamic resistance to institutional congealment is impressive. There remains the question whether institutional fluidity was associated with a more open intellectual system. Apparently not. A student might move from one master to another, but he was expected to follow the ideas of a senior scholar, rather than engaging in private reading and putting forward personal views.49

The Ottoman medrese (the Turkish form of the word madrasa) followed a similar pattern. The mosque which Sultan Mehmed II founded in Istanbul soon after conquering the city had eight colleges attached to it. By the seventeenth century there were ninety-five colleges in the city, rising to 200 in the eighteenth century. The lectures were open, but for the students who wanted to attain high office in the ulema (above) as judge, counsellor or teacher (müderris), the support of a particular master was essential. By 1550, to have studied in certain prestigious colleges, the so-called ‘inner’ group, was a virtual prerequisite for high office. Diplomas and examinations were introduced, so many signs that the system was becoming more formal.50

In this system, in both its Arab and Ottoman forms, the study of nature was marginal. It was carried on for the most part outside the colleges. Medical teaching took place in hospitals, foundations with a long history in the Muslim world, while astronomy was studied in specialized observatories. The first known observatory was founded in 1259, while a new one was founded at Galata in 1577 – the year after Uraniborg – by a scholar, Takiyyüddin, with the support of Sultan Murad III. It was destroyed by soldiers in 1580, a sign that the knowledge of nature was not only institutionally marginal but considered by some as irreligious.51 However, marginality, as we have already seen, can sometimes be an advantage. At any rate, medicine and astronomy were at once marginal areas and seats of innovation in the world of Islam.

The example of the Muslim world, more especially that of the Ottoman Empire, appears to confirm the theories of Veblen and Bourdieu in some respects, although the persistence of an informal system over the long term shows that institutionalization cannot be taken for granted. A comparison and contrast between the worlds of Islam and Christendom (Catholic and more especially Protestant Christendom, rather than the world of Orthodoxy), highlights the relative strength of opposition to intellectual innovation in Islam, including opposition to the new technology of the intellect, the printing press. The hypothesis that printing, which made intellectual conflicts more widely known, also encouraged critical detachment, receives some support from comparative historical analysis.52

Generally speaking, it seems that the marginal individual finds it easier to produce brilliant new ideas. On the other hand, to put these ideas into practice it is necessary to found institutions. In the case of what we call ‘science’, for example, the institutional innovations of the eighteenth century seem to have had important effects on the practice of the disciplines.53 Yet it is virtually inevitable that institutions will sooner or later congeal and become obstacles to further innovation. They become the seats of vested interests, populated by groups who have invested in the system and fear to lose their intellectual capital. There are social as well as intellectual reasons for the dominance of what Kuhn calls ‘normal science’.

Thus the social history of knowledge, like the social history of religion, is the story of the shift from spontaneous sects to established churches, a shift which has been repeated many times over. It is a history of the interaction between outsiders and establishments, between amateurs and professionals, intellectual entrepreneurs and intellectual rentiers. There is also interplay between innovation and routine, fluidity and fixity, ‘thawing and freezing trends’, official and unofficial knowledge. On one side we see open circles or networks, on the other institutions with fixed membership and officially defined spheres of competence, constructing and maintaining barriers which separate them from their rivals and also from laymen and laywomen.54 The reader is probably tempted to side with the innovators against the supporters of tradition, but it is likely that in the long history of knowledge the two groups have played equally important roles.

1 Schumpeter (1942).

2 Lemaine et al. (1976), 8–9.

3 Pareto (1916), section 2233.

4 Bourdieu (1989); Elias (1982).

5 Le Goff (1957), 80ff; Ridder-Symoens (1992, 1996).

6 Ridder-Symoens (1992); Verger (1997).

7 Innis (1950).

8 Stock (1983).

9 McClellan (1985).

10 Webster (1975).

11 Field (1988); Hankins (1991).

12 Garin (1961); cf. Goldstein (1965).

13 Stevenson (1927); Pulido Rubio (1950), 65, 68, 255–90; Goodman (1988), 72–81.

14 Yates (1947); Sealy (1981); Hankins (1990).

15 Burke (1983).

16 Grossmann (1975).

17 Codina Mir (1968), 18–49.

18 Bentley (1983), 70–111.

19 Lunsingh Scheerleer and Posthumus Meyes (1975); Wansink (1975).

20 Fletcher (1981); Giard (1983–5); Rüegg (1992), 456–9; Pedersen (1996).

21 Shapin (1996).

22 Hall (1962); Rossi (1962).

23 Ruestow (1973), esp. 1–13.

24 Ornstein (1913), 257. Cf. Brown (1934), Middleton (1971).

25 Hill (1965), Webster (1975), 185–202.

26 Ruestow (1973); Tyacke (1978); Feingold (1984, 1989, 1991, 1997); Brockliss (1987); Lux (1991a, 1991b); Porter (1996).

27 Cohen (1989).

28 Impey and Macgregor (1985); Pomian (1987); Findlen (1994).

29 Evans (1973), 196–242; Moran (1991), 169ff; Smith (1994), 56–92.

30 Biagioli (1993); Stroup (1990), esp. 108.

31 Hill (1965), 737–61 Mazauric (1997); Ames-Lewis (1999).

32 Picard (1943); Lougee (1976); Viala (1985), 132–7.

33 Knowles (1958, 1959).

34 Hunter (1989), 1–14.

35 Parker (1914).

36 Hunter (1989), 1, 188, 261, 264–5; Stroup (1990), 51; Christianson (2000).

37 Hahn (1975); Gillispie (1980); McClellan (1985); Lux (1991).

38 Voss (1972), 220–9; Gasnault (1976); Hammermeyer (1976); Ziegler (1981).

39 Voss (1972), 230–3; Roche (1976, 1978); Voss (1980).

40 Klaits (1971); Keens-Soper (1972); Voss (1979).

41 Im Hoff (1982; 1994, 105–54); Dülmen (1986).

42 Goodman (1994), 53, 73–89; Im Hoff (1994), 113–17.

43 Habermas (1962); Stewart (1992); Johns (1998), 553–6.

44 Calculated from Sgard (1991).

45 Julia (1986), 194.

46 Pedersen and Makdisi (1979); Makdisi (1981).

47 Berkey (1992), 20, 30; Chamberlain (1994).

48 Curtis (1959); Stichweh (1991), 56.

49 Berkey (1992), 30; Chamberlain (1994), 141.

50 Repp (1972; 1986, 27–72); Fleischer (1986); Zilfi (1988).

51 Huff (1993), 71–83, 151–60, 170–86.

52 Eisenstein (1979).

53 Gillispie (1980), 75; Lux (1991a), 194.

54 Kuhn (1962); Shapin (1982); Elias (1982), 50.