PRIVATE GARDENS ARE A FEATURE of most of the dwellings found within the UK. A study by Davies et al. (2009), using data from a number of different datasets, put the proportion of households with an associated garden at 87 per cent. The researchers then used this information, alongside figures for mean garden size and the number of households, to calculate the total area of gardens within the UK. The resulting figure, some 432,964 ha, represents an area larger than the county of Suffolk but still an order of magnitude less than the 4.7 million ha of UK land that is under statutory protection.

While such figures underline that gardens only make up a relatively small part of the UK land area, they are the habitat within which many of us engage with birds and other forms of wildlife. This gives them special importance, not least because gardens provide the best opportunities to empower UK citizens with the conservation and research understanding needed to support sustainable planning, lifestyle and land management decisions. Birds are of particular importance in this context because they are one of the most visible, accessible and appreciated components of the wider natural world. If we can understand how they use gardens, and how this use is perceived by the people who have access to those gardens, then we can begin to provide the evidence and messaging needed to support public engagement with the natural world more widely.

FIG 1. Private gardens vary considerably in their size, composition and use, presenting a series of different opportunities for birds. (Mike Toms)

We also need to recognise that gardens come in many different forms; at the simplest level they have tended to be split into those that are urban, suburban or rural in nature, but there is substantial variation within these broad categories. Many gardens fall within urbanised landscapes, so we also need to understand the relationships that exist between gardens and their surroundings. We know, for example, that city-centre gardens are just one form of urban green space and that birds, being mobile, will move between a city’s many different patches of such space. But how important is the spatial arrangement of these different patches or the temporal pattern of feeding resources available within them? Many of the same questions can be asked of those birds using rural gardens, perhaps bordered by arable farmland or woodland plantations. This underlines that gardens should not be viewed in isolation but rather as a part of a wider landscape over which birds may range. In some cases these ranging movements may take birds not just beyond the boundaries of the gardens and often urbanised landscapes within which they sit, but also beyond the borders of countries or even continents.

FIG 2. The Robin is perhaps the most familiar of our ‘garden birds’ but in reality it is a species of woodland edge habitats. (John Harding)

It is for this reason that this book on garden birds starts by looking at the nature of the garden habitat and the garden’s place within a wider landscape context. Inevitably, this will require us to look at urban ecology and the processes that shape the urban environment, and to look into a future where the ongoing process of urbanisation sees an ever-growing number of us living within towns and cities. We will also use this chapter as an opportunity to ask ‘what is a garden bird?’ and to examine the nature of garden bird communities. Are they, for example, just those species that happen to be generally common and widespread across the wider landscape, or is there something special about garden bird species and the communities that they form.

THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT

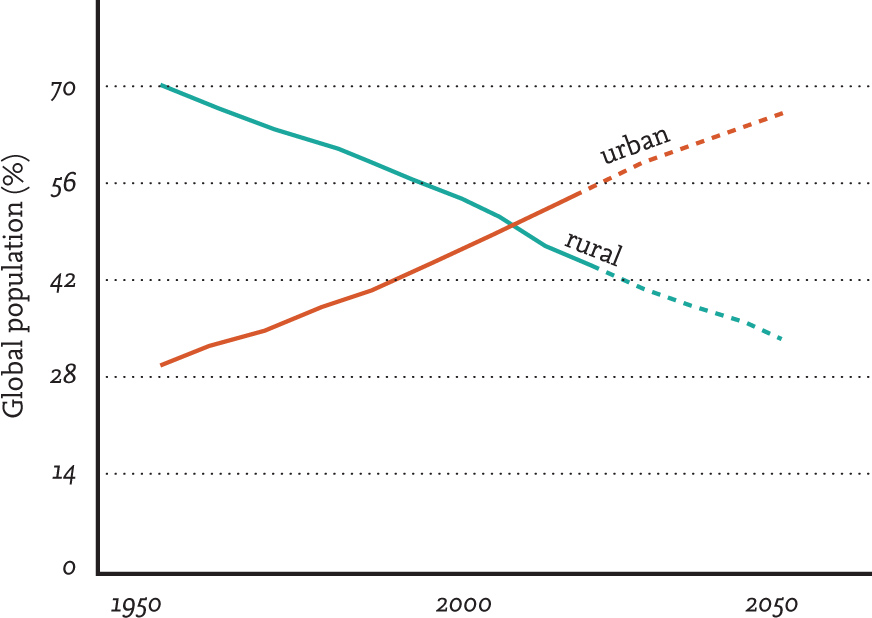

One of the most shocking statistics relating to the human population is that showing the proportion of the global population now living within urbanised landscapes (see Figure 3); this figure, which passed 50 per cent in 2008, is projected to reach 66 per cent by 2050 (United Nations, 2014). This increase brings with it an associated increase in the amount of land under urban cover. Urbanisation is an ongoing process and considered to be one of the greatest threats facing species and their ecosystems. It is of particular concern because some of the most intensive urban development is projected to occur within key global biodiversity hotspots (Elmqvist et al., 2013). The growth in the numbers of households globally, and within biodiversity hotspot regions in particular, has been more rapid than aggregated human population growth, reflecting that average household size continues to fall. This is relevant because the reduction in average household size is thought to have added 233 million additional households to biodiversity hotspot countries alone between 2000 and 2015 (Liu et al., 2003). It seems all the more important than ever to understand the implications of urbanisation for biodiversity; to some extent this urgency has been recognised by the research community, with increasing numbers of studies helping to unravel how birds and other forms of wildlife make use of the urban environment and revealing what urban expansion means for their wider populations. Urbanisation also has implications for the ways in which the human population interacts with the wider natural world, of which it is a part, so we also need to learn about these relationships and what they mean for both birds and people; this is something that we will explore in Chapter 6.

FIG 3. The proportion of the human population living within urbanised landscapes passed 50% in 2008 and is predicted to reach 66% by 2050. Redrawn from United Nations data.

The process of urbanisation involves the conversion of natural or semi-natural landscapes – the latter including farmed land – into ones that are characterised by high densities of artificial structures and impervious surfaces. Urbanised landscapes contain fragmented and highly disturbed habitats, are occupied by high densities of people and show an elevated availability of certain resources. Associated with the process of urbanisation is the modification of ecological processes, particularly those linked with nutrient cycling and water flow. The density of bird species within such landscapes is best explained by anthropogenic features and is often negatively associated with the amount of urban cover. This underlines the importance of urban green space, especially gardens and (for some species) urban parks and woodland. Although many bird species decline in abundance once an area has become urbanised, some are able to take advantage of the new opportunities that have been created. Because different species respond to urbanisation in different ways, we typically see a dramatic shift in the structure of avian communities living within urban landscapes and the habitats, like gardens and urban parks, found within them.

Alongside the structural changes seen, which may alter nesting opportunities or the availability of food resources, urbanisation also results in increased levels of disturbance, noise, night-time light and pollution, all of which may impact birds and other wildlife. While some of these impacts may be generally negative across species, there may be instances where such effects are not felt equally. Noise pollution can impact on some species more than others, for example, perhaps because of the frequencies at which such noise tends to occur; bird species whose songs are pitched towards lower frequencies may be affected more than those whose high-pitched songs can still be heard above the background noise. Other species may show a behavioural response, perhaps moving the time at which they sing or even altering the characteristics of the song itself. It has been found, for example, that Robin Erithacus rubecula populations breeding in noisy parts of urban Sheffield sing at night, with the levels of daytime noise experienced by these individuals a better predictor of their nocturnal singing behaviour than levels of night-time light pollution, the latter previously considered to have been the driver for nocturnal song in this species (Fuller et al., 2007a).

Not all of the changes that occur during urbanisation are necessarily negative; the provision of food at garden feeding stations (Chapter 2) is regarded as being generally beneficial, buffering the temporal variation in food availability that is typical of natural landscapes and thought to limit populations. The availability of anthropogenic food, either at garden feeding stations or present as food scraps, is thought to be one of the main factors driving the structure of urban bird communities, something to which we will return shortly. A number of studies have found that urbanisation stabilises both the richness and composition of bird communities, perhaps because there is greater predictability of, and less variation within, the climate and resource availability of more urbanised landscapes (Suhonen et al., 2009; Leveau & Leveau, 2012).

As we’ll also discover later in this chapter, some species are better able to cope with or respond to the impacts and opportunities of the built environment than others, and there are particular traits within bird families or species groups which may lead to them being more likely to adapt to the urban environment (Blair, 1996). This raises the question of just what is a garden bird.

WHAT IS A GARDEN BIRD?

Some people take the term ‘garden bird’ to mean a species that is common and widespread, adaptable and found just as commonly in other habitats. While this is certainly true of many garden birds, it is not true of every species found to use gardens on a regular basis. The phrase ‘common or garden’ – meaning something that is common and consequently of little value – may have also added to the sense that garden birds have little conservation value and are thus of little interest. This may be exacerbated by the sense that gardens themselves are an artificial habitat, highly modified and managed and thus greatly removed from more natural habitats and processes. However, it needs to be remembered that many of the habitats that we consider to form the countryside – such as farmland and woodland – are also often highly managed and very different to wholly natural landscapes untouched by human activities. Once we recognise this, then it becomes possible to accept garden birds less as a distinct type of bird and more as simply a subset of a wider population using a broad range of habitats.

Look at any book on UK garden birds and you will see species that are summer migrants (Swift Apus apus, House Martin Delichon urbicum, Spotted Flycatcher Muscicapa striata), winter visitors (Redwing Turdus iliacus, Waxwing Bomybycilla garrulus, Brambling Fringilla montifringilla, Fieldfare Turdus pilaris), insectivores (Goldcrest Regulus regulus, Wren Troglodytes troglodytes), omnivores (Carrion Crow Corvus corone), cavity nesters (Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus, Great Tit Parus major) or have low dispersive ability (House Sparrow Passer domesticus), all underlining the variety of ecological traits encountered within our garden bird community. Certain ecological traits may come to the fore if you look at particular components of the wider community; for example, an examination of the birds using garden feeding stations may suggest the dominance of granivorous and omnivorous species rather than insectivores, a reflection of the types of food being provided (Shochat et al., 2010). A different pattern may be seen in winter from summer, when looking at some aspect of the breeding community, or indeed when looking at the same component (e.g. cavity-nesting) but in different geographical locations. We know, for example, that cavity-nesting species are well represented within the UK garden bird community, having adapted to nest boxes, but are far less common in that of Australia, where native cavity nesters rely on natural tree cavities rather than boxes (Shanahan et al., 2014).

Globally, certain species are well represented within garden bird communities, including Rock Dove/Feral Pigeon Columba livia, House Sparrow and Starling Sturnus vulgaris (Aronson et al., 2014). Also widely represented – at least within the wider urban environment – are introduced or ‘invasive’ species such as Mallard Anas platyrhynchos, Canada Goose Branta canadensis, Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto and Ring-necked Parakeet Psittacula krameri, plus (in those places beyond their native range) House Sparrow, Starling and Rock Dove/Feral Pigeon. As a group, corvids appear to be well represented, as do pigeons and doves, leading some authors to suggest that urban bird communities globally are becoming more homogenous in their composition (either directly, in terms of particular species, or indirectly, through different species occupying similar ecological niches). This process is something that we will discuss in the next section.

FIG 4. Blackbird is best considered as an ‘urban adopter’, a species that is opportunistic in the way that it uses gardens and the resources that they offer. (John Harding)

The species of birds associated with the urban environment – of which gardens are a key component – can be divided into three main types. These are the ‘urban exploiters’, the ‘urban adopters’ and the ‘urban relicts’. Exploiters are those species, like Feral Pigeon, that are typically abundant within urban areas and which depend upon the anthropogenic resources available within the built environment. Adopters also make use of the resources but are more opportunistic in how they do this, and many of our familiar garden birds can be regarded as being of this kind – think of the Blackbirds Turdus merula and Siskins Spinus spinus that move into gardens during the winter months. Urban relict species are those whose population has managed to hang on within a fragment of their former habitat that is now contained within a wider urbanised landscape; such species tend to be found outside of western Europe, where new cities have emerged quickly within formerly wildlife-rich habitats. Another term that may be encountered when discussing urban bird populations is ‘urban avoiders’, those species that are absent or very poorly represented within the urban bird community.

The Rock Dove/Feral Pigeon is one of the oldest and most cosmopolitan commensal species, whose huge global population reflects early domestication and the subsequent transportation and introduction to sites across the world. The very high Feral Pigeon densities encountered in many cities is, to a large degree, a consequence of supplementary feeding and discarded human food, and the presence of buildings and other structures with an abundance of suitable nest sites. In some cities, such as Singapore, these populations are derived from the rapid expansion of a genetically homogenous group of founder individuals (Tang et al., 2018), underlining how a species can very rapidly colonise an urban area given favourable conditions. Similar patterns may be seen in introduced populations of House Sparrow, Starling and Collared Dove.

The notion that species found in a high proportion of the world’s cities, such as Starling, are successful generalists and able to breed anywhere, does require some refinement. Work by Gwénaëlle Mennechez and Philippe Clergeau has, for example, revealed that while the abundance of breeding Starlings does appear to be similar throughout the urbanisation gradient, the degree of urbanisation still has a measurable negative impact on its breeding success. Working in western France, Mennechez and Clergeau (2006) found that the amount of food delivered to Starling nestlings in more urbanised areas was significantly lower than that delivered elsewhere along the urbanisation gradient, resulting in smaller nestling masses. These urban Starlings were found to produce fewer young, each of seemingly lower quality; while they were able to maintain breeding populations in these highly urban habitats, the species was not as successful as a simple measure of breeding abundance might suggest. This is something to which we will return in Chapter 3.

URBAN BIRD COMMUNITIES

Surprisingly perhaps, one in five of the world’s 10,000 or so bird species is found in the highly urbanised landscapes of major cities, including 36 species that have been identified by the IUCN global Red List as threatened with extinction. (Aronson et al., 2014). Globally, the species richness of urban bird communities ranges from 24 species to 368, with a global median of 112.5 species (Aronson et al., 2014). As just noted, a number of studies, typically involving work carried out within a single city, have suggested that the process of urbanisation results in urban bird communities that are becoming increasingly similar over time, and dominated by a few key species. This process is known as homogenisation and is thought to come about because urbanisation not only extirpates native species from an area but also promotes the establishment of non-native species capable of adapting to the new conditions (Luck & Smallbone, 2010). Although these new conditions tend to be similar in cities across the world, they do not in themselves promote the same species winners; instead, it is our preference for certain species (transporting them to new settlements) that has resulted in the homogenisation seen at a global scale (McKinney, 2006).

In their review of the bird communities of 54 cities, spread over 36 countries and 6 continents, Aronson et al. (2014) found that cities tended to retain similar compositional patterns within their distinct biogeographic regions. While certain non-native species were shared across many of the cities studied, the urban communities had not yet become taxonomically homogenised at a global scale – they retained the characteristics of their local region pool. Four species were found in more than 80 per cent of the cities examined; these being the familiar Feral Pigeon, House Sparrow, Starling and Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica. With the exception of Australasia, the proportion of non-native species found within each urban community was similar (at 3 per cent), Australasia being somewhat higher because of the large number of non-native species introduced into New Zealand by settlers. Work within Europe (Jokimäki & Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, 2003; Clergeau et al., 2006) suggests that urbanisation here might bring about homogenisation by decreasing the abundance of ground-nesting species and those preferring bush-shrub habitats, but also noting that it is difficult to generalise because of the effects of latitude and diversity in the urban habitats studied.

What is interesting about species seemingly well adapted to the urban environment is that they tend to share a number of traits (Leveau, 2013). They tend to be omnivorous in their diet, largely sedentary in habits and able to utilise a range of artificial nesting sites (Máthé & Batáry, 2015). Table 1 highlights the broad ecological traits of the garden bird species considered in this book. As we have seen, omnivores and granivores (seed-eating species) tend to dominate the garden bird community, with insectivores often poorly represented. This suggests that invertebrate populations within gardens and the wider urban environment may not be sufficient to support populations of insect-eating birds. It also has implications for breeding success more widely, since most small birds feed their chicks on invertebrates. Work by Croci & Clergeau (2008) also suggests that ‘urban adapter’ species are those that are sedentary in habits and omnivorous, though with the additional traits of preferring forest environments, being widely distributed, and being high-nesters with large wingspans. Croci & Clergeau (2008) also note that ‘urban avoider’ species tend to be those that allocate more energy to their breeding attempts than ‘urban adaptor’ species, a trait that might make it difficult for them to adapt to new environments. Logically, given the absence of larger and older trees with natural cavities, you might predict cavity-nesting birds to be less common in urban environments. However, the presence of substantial numbers of nest boxes appears to help at least some of these species, most notably the tits, though those requiring large cavities often lose out.

TABLE 1. Common garden birds, their ecological traits and status. * Goldcrest and Long-tailed Tit are open-nesting species, whose nest is fully domed. Conservation status is derived from the Birds of Conservation Concern (BOCC) List, which classifies species as Red-, Amber- or Green-listed based on a number of criteria. Non-native species with feral populations are not assessed by BOCC.

That wild birds can take advantage of the opportunities afforded by human activities is evident from changes in urban-nesting gull populations within the UK, which have increased substantially over a short period of time; this increase has occurred despite the fact that coastal populations of the same species have been in decline. It is thought that much of this increase has been driven by the availability of food scraps on our urban streets and at landfill sites, coupled with the relatively predator-free nesting opportunities available (Ross-Smith et al., 2014).

Interestingly, much of the ecological work looking at urban birds has tended to adopt a binary approach, separating species into urban and non-urban classes and then looking for differences in their ecological and/or physiological traits (e.g. Møller, 2009). Such work has underlined, for example, that insectivores, cavity nesters and migrants are under-represented within urban bird communities, while species showing high rates of feeding innovation, high annual fecundity and high adult survival rates are over-represented. However, such an approach – where species are lumped into one or the other of these two groupings – fails to account for important differences in how individual species may respond to urbanisation, or to differences in how a species may respond in different parts of its geographic range. When you consider these differences, then many of the identified traits characteristic of one or other community disappear (Evans et al., 2011).

The nature of urban bird communities has been the subject of study and review for a number of years and several common patterns emerge. It appears, for example, that local factors are more important in determining the species richness of these communities than factors operating at a wider regional scale, and that urban communities respond positively to the availability of supplementary feeding and the structural complexity of local habitat, but negatively to the degree of human disturbance (Evans et al., 2009a). While there is likely to be continuing debate around this topic (e.g. Møller, 2014), it does appear that, at the species level, generalists are better suited to the urban environment than specialists, as are those species that nest off the ground. Generalist species are known to be less susceptible to, and may even benefit from, environmental disturbance of the sort associated with urbanisation (McKinney & Lockwood, 1999), and they are also the species that appear to be coping best with a changing global climate (Davey et al., 2012), something that may also be behind their apparent success in our towns, cities and gardens. Broader environmental tolerance is something that has been demonstrated in urban birds, most clearly through a study by Frances Bonier and colleagues, who compared the elevational and latitudinal distributions of 217 urban birds found in 73 of the world’s largest cities with the distributions of 247 rural congeners. The results of this work showed that urban bird species had markedly broader environmental tolerance than rural congeners, suggesting that a broad environmental tolerance may predispose some species to thrive within urban habitats (Bonier et al., 2007).

UK GARDEN BIRDS, THE SIZE OF THEIR POPULATIONS AND COMMUNITY STRUCTURE

The BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) is the core scheme used to monitor the population trends of a broad range of breeding bird species across the UK. Some 3,000 participants visit randomly selected 1-km survey squares and record the bird species that they encounter there. The birds seen are recorded in a series of distance bands running out parallel to the line transects along which each observer walks. This approach, coupled with the collection of habitat information for each of the transect sections, allows researchers to calculate density estimates by habitat for each of the bird species commonly recorded. These can then be multiplied up by the area of each habitat type nationally to calculate population estimates based on habitat type, which in turn provide a sense of the bird populations associated with gardens and wider urbanised landscapes (Newson et al., 2005).

FIG 5. Data from the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey underline the sizeable populations of certain species breeding in urbanised landscapes. Redrawn from data presented by Newson et al. (2005).

This approach suggests that some of the national population estimates previously given for familiar species, like Blackbird, Starling, House Sparrow, Greenfinch Chloris chloris, Jackdaw Crovus monedula and Woodpigeon Columba palumbus, have been underestimated because the built environment and its gardens had not been properly taken into account. The BBS habitat-based approach indicates the importance of urban, suburban and rural human habitats for species like House Sparrow and Starling, which have 61.5 per cent and 53.9 per cent respectively of their breeding population found here. The survey has also enabled the production of figures suggesting that the habitats directly associated with human sites (urban, suburban and rural) could represent 27,919 km2 (2,791,900 ha) or 10.9 per cent of UK land area. This can be further broken down as urban (2.2 per cent), suburban (5.1 per cent) and rural human sites (3.6 per cent). The figure of 10.9 per cent is somewhat higher than the 6 per cent figure that has been derived from the Corinne Land Cover map. Given the different assumptions involved, it seems likely that the true figure lies somewhere between the two approaches and possibly closer to the 6 per cent derived from satellite imagery. Using the figure of 432,964 ha, presented at the top of this chapter and calculated by Davies et al. (2009) for the area of UK gardens, and the two figures just mentioned (Newson et al. 2,791,900 ha, Land Cover map 1,454,970 ha) for the amount of built-upon land, suggests that gardens might represent between 16 per cent and 30 per cent of the land area present within UK cities, towns and villages, and 1.79 per cent of total land area.

Gardens and their associated houses are of particular importance to House Martin and Swift, two species that national monitoring schemes like the Breeding Bird Survey struggle to monitor. While these two summer visitors are clearly dependent upon buildings for the nesting opportunities that they provide, the nature of the surrounding gardens is much less important. Resident species, such as House Sparrow and Starling, also make use of domestic dwellings for their nesting opportunities but are more closely tied to the nature of the gardens within which these dwellings are located. The presence of shrubby cover is important for House Sparrow, while Starlings appear to favour properties where there is access to nearby areas of short vegetation – such as garden lawns or amenity grassland. Another summer migrant, the Spotted Flycatcher, also appears to be dependent on the nature of the gardens it occupies, seemingly preferring rural or larger suburban gardens with mature trees and an abundance of small flying insects.

A number of bird species use gardens at a particular time of the year, arriving to take advantage of feeding opportunities when conditions elsewhere become less favourable. This is something that we will examine in greater detail in Chapter 2 but it is worth noting here how the early winter arrival of migrant thrushes and finches boosts resident populations and sees birds taking windfall apples and the fruits of berry-producing shrubs. Joining these less obvious visitors (which look the same as year-round residents, such as Blackbird and Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs) are more obvious migrants, including Brambling, Redwing, Fieldfare and Waxwing. Such species tend to forage over large areas, responding to the availability of favoured foods, and so are able to take advantage of the seasonal resources present in many gardens.

COMMUNITY STRUCTURE AND GARDEN TYPES

As the figures produced by Newson et al. (2005) illustrate, the garden bird community contains a significant component of the wider breeding populations of a number of key species. In addition, Newson et al.’s work underlines that many garden species also occur alongside one another within other communities – such as the farmland bird community and the woodland bird community. There may be differences between these communities in terms of species interactions, such that one species does better than another in one habitat but not elsewhere. Such differences in community structure can also be seen from smaller and more focussed studies. Work on tit populations across different UK habitats reveals that Great Tits usually outnumber Blue Tits in woodland populations, often by 2:1 or more. In a suburban population studied by Cowie & Hinsley (1987), the situation was reversed, with Blue Tit outnumbering its larger relative by 3:1 or more. This suggests that Blue Tits might be better suited to the urban environment than Great Tits.

Gardens vary greatly in their size and structure, and consequently in their use by birds. Although we often categorise gardens into urban, suburban and rural, this is a rather simplistic approach and fails to adequately account for the variation that exists both within individual gardens and in the wider habitat framework within which they sit. Within the UK, as much as 7 per cent of land area may be located within towns and cities with a human population in excess of 10,000 people. Some 80 per cent of the UK population lives in these areas, with 40 per cent of the population living within London and our other major conurbations. In an attempt to document the extent and structure of the gardens associated with these conurbations, Alison Loram and colleagues at the University of Sheffield took a detailed look at the cities of Edinburgh, Belfast, Oxford, Cardiff and Leicester (Loram et al., 2007). The researchers surveyed a sample of at least 500 properties from each of the five cities, revealing that 99 per cent had an associated garden. The size of the gardens – whose median areas varied across the different cities, from 96.4 m2 (Belfast) to 213.0 m2 (Edinburgh) – was closely related to the type of housing present; the general pattern revealing that garden size roughly doubles as you move from terrace housing, to semi-detached to detached. Relatively small gardens (<400 m2) were much more numerous within the cities than larger gardens, contributing disproportionately to the total garden area present. This has important consequences for engaging householders in nature conservation through practices such as wildlife-friendly gardening (see Chapter 6), because a small garden might not seem particularly important in a wider context to a householder. I have often heard the phrase ‘what difference can I make; my garden is only small’ but it is important to remember that individual gardens do not exist in isolation; they are instead part of a wider ecological network.

FIG 6. Blue Tits typically outnumber Great Tits in the urban environment, by as much as 3:1, but are the less numerous species within traditional woodland habitats. (John Harding)

Loram’s work also revealed the spatial pattern of gardens within each of the cities, reflecting variation in the density of the human population and the associated densities of housing stock. The history of each city, together with the geography of its location, contributed to the pattern of housing seen; the notion of a simple gradient in garden size, from the leafy suburbs with their large gardens through to courtyard gardens in the urban centre, was disrupted by these and other factors. This also meant that there was no clear relationship between garden size and distance to the edge of the conurbation within any of the five cities studied. This is important when we look at urban bird populations in more general terms as, for example, examined through the work of Chamberlain et al. (2009a) and others.

At a wider spatial scale, it is possible to use data from the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey to examine the densities of bird species across the broader landscape and, as was done by Tratalos et al. (2007), to look at the relationship between avian abundance, species richness and housing densities within urban areas. Tratalos et al. (2007) found that total species richness – and that of 27 urban-indicator species – increased from low to moderate household densities, before then declining as you reached higher household densities. Avian abundance showed a rather different pattern, increasing across a wider range of household densities and then only declining at the highest household densities. The researchers were also able to look at the patterns in abundance seen within individual species, highlighting some interesting differences between them. Importantly, however, most of the species showed a hump-shaped relationship with household density, declining at the highest densities. A somewhat worrying finding, highlighted by the team, was that avian abundance almost invariably began to decline at a point below the density of housing required by the UK government for new developments.

A number of studies have highlighted that within cities it is the suburbs that support the greatest variety of bird species, something that is reflected in the hump-shaped distribution of the relationship between species richness and housing density mentioned above. A widely accepted hypothesis for the shape of this relationship is that the observed pattern is due to the increased habitat heterogeneity present at intermediate levels of urbanisation – i.e. that the suburbs are more diverse than either the more urbanised town centres or the farmland habitats that so often surround our towns and cities. However, it may also be the case that there is a higher availability of food resources in our suburbs than elsewhere (see Chapter 2) and that this, rather than habitat heterogeneity, shapes species richness.

Where a garden is located along the rural to urban gradient may influence the community of garden birds associated with it. This is something that we have been able to examine by using data from the BTO’s Garden BirdWatch project (Chamberlain et al., 2004a). Looking at nearly 13,000 garden sites contributing weekly data on garden birds between 1995 and 2002, we examined the extent to which the occurrence of individual garden bird species at a site was determined by features within the garden itself or by the nature of the surrounding landscape. Garden size was taken into account because we found that, in most cases, species were more likely to occur in large gardens (and larger gardens were more likely to occur in rural habitats and to have high tree and hedge cover). Exceptions to this were House Sparrow, Collared Dove, Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus and Starling, all of which were more likely to occur in small gardens.

FIG 7. Analysis of BTO Garden BirdWatch data revealed that while most bird species were associated with larger gardens, Starling was one of four species found to be more likely to occur in smaller gardens. (Jill Pakenham)

Once we had controlled for the effects of garden size and the provision of food at garden feeding stations, we found that the likelihood of many species occurring in gardens was dependent on the nature of the surrounding local habitat rather than on features within the garden itself. We found that 12 of the 40 species examined were most likely to occur where the habitat outside the garden was rural in nature – these included open-nesting passerines associated with woodland or woodland edge (Wren, Robin, Blackbird, Blackcap Sylvia atricapilla and Chaffinch), hole-nesting (Great Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos major, Blue Tit and Coal Tit Periparus ater) or farmland (Pied Wagtail Motacilla alba, Rook Corvus frugilegus, Greenfinch, Goldfinch Carduelis carduelis and Yellowhammer Emberiza citrinella). Just seven species showed a probability of occurrence that was highest in gardens located within urban habitats, these being House Sparrow, Feral Pigeon, Starling, Magpie Pica pica, Black-headed Gull, Woodpigeon and Collared Dove.

The features within a garden may sometimes be more important than those in the surrounding landscape, as work carried out in Hobart, Tasmania, demonstrates. Daniels and Kirkpatrick (2006) examined how garden and wider landscape features influenced the abundance and species richness of bird species in 214 suburban gardens and found that the percentage cover of shrubs had a very important influence on the garden birds present, with the presence of shrubby vegetation favouring small native woodland birds and the New Holland Honeyeater Phylidonyris novaehollandiae in particular. The same study also underlined the importance of native vegetation for the nectar- and fruit-eating bird species native to Tasmania, but did note that such species also made use of non-native plants. In contrast, introduced bird species – such as Blackbird, House Sparrow and Goldfinch – only used non-native vegetation.

A piece of UK work looking more broadly across a single urban area – the city of Bristol – identified three different bird communities: one composed of species associated with broadleaf woodland and/or inland waterbodies, one associated with high-density housing and residential gardens, and one intermediate to these two and associated with low-density housing and variable amounts of woodland (Baker et al., 2010). More detailed examination of these three communities suggests that the diversity of bird species present within urban areas may be dependent on the availability of blocks of natural and semi-natural habitat, with areas dominated solely by residential gardens supporting fewer species. However, despite the lower species diversity of residential gardens, these areas may support particularly high densities of those species that are present. This is something that is reinforced by other work (e.g. McKinney & Lockwood, 1999).

The spatial arrangement and pattern of gardens and other forms of urban green space also has consequences for the extent to which birds use different patches. Connectivity of suitable habitat patches may be less of a problem for birds than it is for less mobile species, but it has still been shown to be of importance. Esteban Fernández-Juricic, for example, highlighted the importance of wooded streets as potential corridors for birds living in urban Madrid (Fernández-Juricic, 2000), while work in North America has revealed that even the movement of urban-adapted species is influenced by the structure and composition of urban habitats (Evans et al., 2017).

FIG 8. The presence of green cover within urban areas is of particular importance to urban birds, shaping both their distribution and their ability to move between different parts of the built environment. (Mike Toms)

While there has been relatively little work examining how features within and around gardens influence the bird species present, rather more work has been done on other components of urban green space (Jokimäki, 1999). Some of the findings from these studies may provide an indication of how similar features may influence garden bird communities. Work on areas of public green space within London has, for example, underlined the importance of patch size, the presence of waterbodies and the provision of areas of scrubby cover and weedy patches (Chamberlain et al., 2004b). Importantly, some of this work has also underlined the importance of gardens in promoting the species richness of the bird communities using other types of urban green space, such as parks (Chamberlain et al., 2004b). Interactions between gardens, urban green space and the wider built environment may be complex, with the non-biotic components of a city (such as building height and architectural style) also a potential influence on the nature of the bird communities present. Work in Paris, for example, has demonstrated that building height can influence the abundance of particular avian guilds, such that the abundance of omnivorous species was found by Vincent Pellissier to be influenced by the interaction between building heterogeneity and the proportion of low and medium-height buildings present (Pellissier et al., 2012). The findings of this work have implications for urban planning.

Although our work examining the BTO Garden BirdWatch dataset (see Chapter 6) underlines the greater importance of features outside of a garden in determining its use, there do appear to be some garden characteristics that shape the extent to which a garden is visited by particular bird species. Several finch species appear to favour those gardens (and garden feeding stations) that are associated with the presence of tall and mature trees (either within the garden or nearby). Greenfinches, Chaffinches and Goldfinches appear to prefer to fly into tall trees before dropping down to garden feeding stations to feed. Similarly, the presence of thick shrubby cover near to feeding stations appears to increase their use by House Sparrows. The presence of berry-producing shrubs and trees will influence whether or not a garden is visited by wintering thrushes or Waxwings, while the presence of a pond appears to be a particularly attractive feature during the summer months for many different garden bird species.

HOW THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT IMPACTS ON BIRDS AND THEIR POPULATIONS

Over recent years there has been an increasing push to understand the finer-scale effects of the urban environment – of which gardens are a significant component – on the ecology, health, behaviour and physiology of birds. Such effects have been studied both at the level of the individual bird and at the level of the population or community. As we shall see in this section, some of these effects can have significant consequences, determining which species thrive in our town and city gardens and which struggle.

Three of the most striking ways in which urban habitats and gardens differ from more natural landscapes are in the availability, predictability and novelty of key resources, most notably food (provided at garden feeding stations) and nesting opportunities (provided through nest boxes). As we will discover in Chapter 2, the presence of food at garden feeding stations can lead to the creation of a more predictable environment (both through time, and spatially across the city or town). This can have profound consequences for urban birds, as work on Northern Cardinal Cardinalis cardinalis populations in Ohio has demonstrated. Rodewald & Arcese (2017) found that female cardinals, breeding in urban habitats within their study area, were more similar in their contribution to the next generation than was the case for those breeding in rural habitats, where a pattern of winners and losers was more evident. Importantly, this difference occurred despite comparable variation in body condition across the habitats studied. The urban cardinal population, then, is more homogenous in terms of its breeding performance than the rural population.

Living within an urban environment is thought to impact on the health of the organisms found there and we know, for example, that urban pollution elevates the levels of oxidative stress (see Chapter 4) seen in humans and birds (Isaksson, 2010). Researchers have measured the levels of oxidative stress in urban populations of study species and compared these with individuals living in other, more natural habitats. Other researchers have looked instead at the levels of particular hormones, again using these to tease out possible health effects. More recently, attention has turned to telomeres; these are the nucleoprotein structures found at the end of chromosomes. Telomeres are thought to promote genome stability and there is good evidence to associate the length of a telomere with lifespan, mortality rate and disease risk. This suggests that telomeres may prove a useful ‘biomarker’ for phenotypic quality and ageing. If the pressures of urban living modify an individual’s oxidative balance, then this may result in the shortening of telomere length and indicate a health effect.

FIG 9. Being raised in an urban environment significantly reduces telomere length in Great Tits. Telomeres are the nucleoprotein structures found at the end of chromosomes and thought to promote genome stability. They have been linked to health and longevity. (Jill Pakenham)

Through an experiment in which nestling Great Tits were cross-fostered, Salmón et al. (2016) found that being raised in an urban environment significantly reduced telomere length compared to that of nestlings raised in a rural environment. However, this finding could not be replicated by a similar study in France (Biard et al., 2017). A larger study, this time of Blackbirds, also found that urban-dwelling individuals had shorter telomeres than those living elsewhere, adding evidence to this growing area of research interest (Ibáñez-Álamo et al., 2018). While Clotilde Biard’s study failed to find differences in telomere length between urban and rural populations of Great Tits in France, the work did reveal differences in chick growth (rural chicks were larger and heavier) and in plumage colouration (the yellow carotenoid-based plumage was more colourful in rural chicks – see also Chapter 2), suggestive of developmental constraints within the urban populations. Measures of ‘damage’ in relation to the impacts of urbanisation have been shown to vary between species with, for example, Salmón et al. (2017) determining that sparrow species show greater overall damage than that seen in tits.

There is the suspicion then, that gardens and the wider urban habitat are sub-optimal for many bird species (though not all). If this is the case, then we might expect to see the presence of three features that have been found to be characteristic of sub-optimal habitats elsewhere. These are:

i) a greater proportion of young breeders and more floating individuals;

ii) less stable populations, whose numbers fluctuate from year to year; and

iii) low breeding density.

The idea that populations living within sub-optimal habitats are more likely to fluctuate from year to year is linked to the notion of ‘source-sink’ dynamics, where populations living within high-quality habitats produce a surplus of young each year, but competition for breeding territories in these high-quality habitats is high, resulting in many young and less dominant individuals moving away to occupy territories in less optimal habitats. This also explains the first characteristic that we mentioned – the greater proportion of young birds in sub-optimal habitats. We certainly see this in suburban tit populations (Cowie & Hinsley, 1987; Junker-Bornholdt & Schmidt, 1999) but it isn’t always the case. Work on farmland Blackbird populations has revealed the presence of greater numbers of young males in this habitat (Hatchwell et al., 1996a), and David Snow – in his classic treatise on urban Blackbirds – speculated that urban populations act as a source population for a rural sink (Snow, 1958). Snow had demonstrated that his urban Blackbirds were generating a significant surplus of youngsters each year, some 1.7 yearlings per pair when only 0.7 yearlings per pair were needed to maintain a stable population.

Urban living may also lead to greater exposure to humans, perhaps resulting in increased tolerance of their presence and reduced levels of ‘fear’. Work on urban Great Tits has highlighted that they are less neophobic and show shorter flight initiation distances (see Chapter 6) than their rural counterparts (Møller et al., 2015; Charmantier et al., 2017). They also appear to have a more proactive coping strategy when dealing with stressful situations (Senar et al., 2017a).

DISEASE AND THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT

Chapter 4 explores the diseases affecting garden birds in detail, but it is important to give a brief overview here of how disease risks differ between urban and rural environments. Comparisons between the diseases of urban and rural populations of birds have yielded mixed results when it comes to seeking general patterns of occurrence and prevalence. Some studies, such as the work of Grégoire et al. (2002), Fokidis et al. (2008) and Evans et al. (2009a), have found reduced parasite loads in urban populations of garden bird species, including Blackbird. Others, such as Giraudeau et al. (2014) have found higher levels of disease in more urban areas. Giraudeau’s work revealed that the severity of coccidian infection in House Finch Haemorhous mexicanus and the prevalence of pox virus were both inversely related to the proportion of undisturbed habitat within the Phoenix metropolitan area. Patterns of disease infection along urban to rural gradients, and across the different habitats within the urban environment, may differ between diseases, in part a reflection of variation in how different diseases are transmitted. In the case of parasites, transmission may require an intermediate host that is absent from the urban environment (Sitko & Zales´ny, 2014), but for other diseases – including those transmitted between individuals through contaminated food – transmission rates may increase in gardens and other urban sites because of the high densities of birds attracted to garden feeding stations (Lawson et al., 2018). The provision of food at garden feeding stations may also influence disease dynamics (Galbraith et al., 2017a).

FIG 10. Garden feeding stations have been implicated in the transmission of disease between different species of garden bird, but the presence of supplementary food also has positive benefits for birds like this Brambling. (Jill Pakenham)

ARE GARDENS IMPORTANT?

As the figures presented within this chapter demonstrate, gardens and the wider built environment support significant proportions of the breeding populations of certain bird species. In addition, gardens and their associated resources may be important for particular birds at other times of the year or during periods when the availability of key resources within the wider environment is at a seasonal low. This underlines that gardens are important, and not just for species flagged as being of conservation concern. How we manage our gardens and the resources they contain has consequences for bird populations and, as we shall see later in this book, may also help to drive evolutionary change. It is important to remember that garden bird populations do not exist in isolation, since birds are well able to move between different habitats or regions. While gardens may not be as suitable as certain other habitats for breeding, they may be better in other ways, at least for some species.

We are, however, far from fully understanding the role that gardens play in a wider context, particularly in relation to source-sink dynamics, and it is certainly too early to be able to quantify the true value (or cost) of garden living for bird populations here in the UK, in Europe or North America, let alone elsewhere in the world. The mobility of birds makes it difficult to follow individuals throughout their full life cycle; in turn, this prevents us from being able to determine why particular individuals use gardens and the consequences or benefits of this use on future events in their lives. For a young Great Tit, raised in a piece of mature deciduous woodland bordering a city’s suburbs, the presence of suitable food in garden bird feeders may enable it to survive its first winter when it would otherwise have died. While this fortunate individual may fail to secure a prime woodland breeding territory the following year, and instead end up making a failed breeding attempt in a garden setting, it may still have the opportunity to occupy a woodland territory in a subsequent year. In the end, this individual’s lifetime reproductive success may still be better for having used a garden and its resources, than would have been the case had it only ever lived within a woodland site.

FIG 11. Gardens across the globe vary greatly in their structure and in the plants they contain, something that can reflect both cultural differences and local conditions. (Mike Toms)

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Before we leave this chapter and turn to look in more detail at particular aspects of the garden environment, it is worth reminding ourselves that the gardens present here in the UK, and across much of western Europe and North America, are often very different from those in other parts of the world. Thinking about gardens in a more global context forces you to move away from the predominantly recreational basis to gardens located within western Europe and North America. Many home gardens elsewhere are very different and provide families with space to engage in food production for subsistence or small-scale marketing. Such gardens may also play an important social or cultural role, perhaps acting as spaces within which knowledge related to agricultural practices can be shared. The management of these spaces creates structures and microclimates that are typically very different from the surrounding countryside; in this respect they can be considered alongside the more familiar urban and suburban gardens of western Europe, even though they look and act very differently (Guarino & Hoogendijk, 2004). It is known, for example, that ‘home gardens’ support high levels of inter- and intra-specific plant diversity, making them important in a global context, but far less is known about the role that they play for wider biodiversity and, in the context of this book, wild birds (Galluzzi et al., 2010). For the most part, however, we will just consider the gardens of western Europe, North America and Australasia in this book, something that also reflects where the greater amount of research has been carried out. The pattern of research worldwide isn’t just linked to particular geographic areas, since it has also been demonstrated that there is a positive and significant association between the degree of urbanisation of a species and how frequently it has been the subject of scientific study (Ibáñez-Álamo et al., 2017).

This chapter has highlighted the fact that gardens come in many different forms and that this has consequences for the communities of birds associated with them. The birds present in our gardens are the species that have, for the most part, adapted to the process of urbanisation to take advantage of the resources and other opportunities that gardens and the wider built environment provide. While some of these species populations are resident within the built environment, others make use of our gardens on a seasonal basis. Most UK gardens are located within highly urbanised landscapes; with urban land cover globally predicted to triple between 2000 and 2030 (United Nations, 2014), we can expect to see future changes in our garden bird communities. Such changes are part of an ongoing process that has altered the distribution of bird species, changed the composition of avian communities, brought about local extinctions and altered behaviour. It is these features and processes that we will examine of the following chapters, starting with feeding opportunities (Chapter 2), then moving on to an examination of breeding behaviour (Chapter 3), disease risk (Chapter 4) and behaviour (Chapter 5).