TABLE 5.1 NDPG comparison: Personnel and major equipment

Source: Adapted from Ministry of Defense, Defense of Japan 2014, 151–52.

Note: Some of the values are listed as approximate in Defense of Japan 2014.

a Subset of combat aircraft.

Prime Minister Shinzō Abe’s return to power in December 2012 returned Japan to international attention with his popular “Abenomics” economic policy platform and his oft-repeated motto that “Japan is back.” Abe projected a refreshing new image of Japan as revitalized and confident. His own political comeback was seen by many as an inspiring metaphor for Japan’s potential comeback. Abe’s security policies have received special attention because of his outspokenly nationalist views on controversial history issues, the company he keeps (including many historical revisionists in his party and civil society institutions), and rising tensions with rival China and fellow US ally South Korea. In addition, the sheer number of new security policies enacted under Abe attracts attention and scrutiny.

This chapter explains these numerous new security policy developments as a response to the changed international environment Japan faces and as a result of changed domestic politics in Japan, but in each case also structured and limited by the three important historical legacies under which Japan’s leaders must operate—illustrating how Japan’s security renaissance is both forward looking and backward looking. The legacy of Japan’s wartime and colonial past became closely associated with Abe, rightly or wrongly, and his efforts to address this history were widely covered. The postwar legacy of antimilitarism sharply hindered and shaped the policies enacted over these years, and the politics surrounding them. The complex postwar legacy of the US-Japan relationship also continued to shape Abe’s policy preferences in multiple ways, from the landmark 2015 US-Japan Guidelines for Defense Cooperation to the continued challenges of strident opposition to the concentration of US military forces in Okinawa. Abe himself will surely exert a lasting legacy on Japan’s security future as one of the longest-serving prime ministers in Japan’s history, but his great efforts to advance Japan’s security renaissance is only one factor that contributed to the scale of change seen during his time in office.

Many of the prominent new security policies enacted in this period mark a culmination of policies initiated by previous administrations, including those of the rival DPJ as well as Abe’s own previous and short-lived administration (2006–2007). It seems likely that any prime minister, not just Abe, would have enacted a similar policy program in response to Japan’s changed international environment—and, indeed, as argued in chapter 4, the three prime ministers of the DPJ ruling period set important precedents that Abe followed.

Still, Abe himself is part of the explanation for the sheer number of prominent developments in the area of military security in the first three years of his administration. His high popularity in the first years of his second term in office—and political savvy—enabled him to advance policies across many areas simultaneously. It was a comeback that rivaled his grandfather’s rise to prime minister in 1957, only a decade after being imprisoned for suspected war crimes and blackballed from political office by the Allied occupation authorities. As with his grandfather Nobusuke Kishi, some of Abe’s security policy reforms also elicited huge public protests, at times drawing out over a hundred thousand demonstrators in front of the Diet building and Prime Minister’s residence,1 reminiscent of the protests in those locations in 1960 over the revision of the US-Japan Security Treaty, though on a much smaller scale. Even former prime minister Murayama, albeit a former socialist prime minister, joined the protests in July 2015 over the Abe government’s package of security legislation, saying to the media, “I stood up out of a sense of crisis.”2

Important developments in security policy, institutions, and practices were numerous and far-reaching in the first three years of the second Abe administration: the crafting and adoption of Japan’s first formal national security strategy, creation of the NSC, new NDPG, new US-Japan Guidelines for Defense Cooperation, enactment of an official state secrets law, legislation implementing a reinterpretation of the constitution to allow Japan to participate in CSD with the militaries of other states in limited circumstances, further relaxation of restrictions on weapons exports, recrafting of ODA doctrine to allow for defense-related aid, and increased military spending for the first time in a decade.3 Debates over enactment of this full agenda illustrate well the international and domestic drivers of security policy change as well as the continued challenges of reconciling Japan’s present goals with the legacies of its past.

The Domestic and International Politics of Abe’s Return to Power

The return of the LDP to power in the December 2012 Lower House elections resulted in large part from the collapse in public confidence in the ability of the DPJ to rule effectively, much as the DPJ’s rise to power three years earlier had been largely the result of public discontent with the LDP broadly as opposed to discontent over any one specific policy or set of policies. One data point from the December 2012 election starkly illustrates that the LDP did not enjoy a sudden new boost in popularity despite the “landslide” outcome in terms of seats gained: the LDP actually received fewer votes in the 2012 election than it had in the 2009 election that brought the DPJ to power in 2009. Rather, what accounts for the huge increase in LDP seats in 2012 is the fracturing of the opposition, a marked decline in voter turnout, and the effect of the electoral system. Due to the effect of single-member electoral districts on translating percentage of vote to percentage of seats, the LDP secured 61.3 percent of the seats in the Lower House election in 2012 with only 43 percent of the vote in the SMD and 27.6 percent in the PR districts. (See appendix 2 for a breakdown of the votes in recent elections.) By contrast, the DPJ secured only 11.9 percent of seats despite gaining 22.8 percent of the votes in SMD and 16 percent in PR districts. When comparing the percentage of LDP votes across elections, one sees that the LDP gained more than double the number of seats in 2012 from 2009, with only about a 5 percentage point higher vote draw in the SMD and only 1 percentage point higher in the PR districts, and fewer actual total votes. Certainly many voters would have been aware of Abe’s hawkish views—after all, he had served as prime minister six years earlier—but support for these views cannot be assumed to be a primary cause of Abe’s and the LDP’s electoral success. Thus, Abe’s election—and the LDP return to power—cannot be seen as an example of a sudden surge of popular support for positions to the political right. Rather, it is the broad continuity of security policies and trajectory between DPJ and LDP rule that illustrates Japan’s security renaissance of the past decade.

Security policy issues arguably factored into public concern with DPJ rule in the general sense of awareness of Japan’s eroding national security status in relation to such issues as the growing fear of military confrontation with China and concerns over the reliability of the US-Japan Security Treaty commitments that emerged at the start of DPJ rule, but security policy issues were not the primary drivers of the change in political power. To a large degree, the particularly assertive security policy views of Abe were incidental to his return to power—though they would ultimately cast a long shadow on perceptions of his time in office. Rather, the LDP campaigned on the need to restore Japan’s economic health, linking even security-policy strengthening to Japan’s economic revitalization.

Upon assuming office, Abe set out three “arrows” of economic policy that would come to symbolize this goal, which the media has embraced as Abenomics. Abe’s success in revitalizing Japan’s moribund economy was critical to his popularity in his first year in office and allowed a simultaneous pursuit of security policy innovation.4 The Japanese economy and stock market posted impressive gains in Abe’s first year in office. Looking forward, success with Abenomics will continue to be a necessary condition for further security policy innovation, including in terms of sustaining necessary public support, maintaining respect and support in the Asian region, and simply paying for the new defensive capabilities and roles that the Abe government seeks to enact.

Abe’s return to power in December 2012 led to the same sort of media firestorm and concerns about rising nationalism in Japan and a dramatic break with Japan’s long-standing security practices as when Abe took office in September 2006. The similarities between the first and second Abe terms as prime minister did not end there. In December 2012, as in September 2006, Abe would face a scheduled Upper House election in July of the following year that would affect his ability to pass new legislation. And as in September 2006, Abe made a number of statements in his first six months in office from December 2012 that made headlines around the world for the concerns they raised about Japan’s rightward policy moves—which the New York Times and China Daily alike described as “hypernationalism.” Unlike his first experience as prime minister, however, Abe successfully led his party to gains in the Upper House election and, less than one year after assuming office, succeeded in implementing several major pieces of national security legislation. These new developments are notable and important. They do not, however, connote a dramatic break from Japan’s past practices but rather reflect an adaptation of past practices to a new international environment—an adaptation that was greatly influenced by domestic politics, particularly the LDP’s coalition partner, the Kōmei Party.5

Here it is important to note the unique sort of coalition the LDP has formed with Kōmei, which is unlike political coalitions common in European democracies due to Japan’s unusual electoral system, which includes both individual constituencies and PR seats in both houses of the Diet. As a small party, Kōmei has little hope of securing seats in the individual constituencies such as the SMD in the Lower House or the prefectural constituencies in the Upper House, but it can (and does) attract voters in the PR vote. As part of the coalition agreement with the LDP, Kōmei instructs supporters to vote for LDP candidates in the SMD in exchange for greater power in the coalition and a few designated SMD seats in urban constituencies. This boost to LDP candidates in individual constituencies arguably led to the LDP landslide win of seats in 2012 and 2014.

As an illustration, consider the LDP-Kōmei return to power in 2012. In that election, Kōmei won 11.83 percent of the PR vote but only 1.49 percent of the SMD vote. (Vote percentages are provided in appendix 2.) Since each voter in Japan casts one vote in each system, one must ask where the missing 10.34 percent of the Kōmei vote in the SMD went (i.e., the difference between 11.83 in PR and 1.49 in SMD). If most Kōmei supporters followed party leader instructions to vote for the LDP candidate, that alone accounts for more than half the vote differential between the DPJ and the LDP in the 2012 election. Put another way, had those votes gone to the DPJ, the LDP and the DPJ share of the vote in the SMD would have been roughly equal, dramatically altering the balance of seats—much beyond what one would expect by just looking at the small vote share Kōmei itself draws.

Kōmei’s pivotal role in boosting LDP vote share in SMD helps to explain why Abe conceded so much of his security agenda ambitions to Kōmei preferences despite Kōmei’s holding presently only roughly 7 percent of the seats in the Lower House versus the LDP’s roughly 61 percent. Another reason is that with Kōmei in coalition, the LDP has the necessary two-thirds majority to override opposition in the Upper House, where the LDP held a very narrow majority until the July 2016 election that could be jeopardized by defectors in the LDP and by procedural rules in the Upper House.

International developments in Japan’s regional environment also assisted Abe in achieving his long-standing agenda for security policy innovation. China pursued an increasingly assertive set of policies related to its claims to the Senkaku Islands from shortly after Abe’s previous term as prime minister, and this aggressive agenda further escalated shortly after Abe assumed office for the second time. In addition to regular incursions into the territorial waters of the Senkaku Islands, Japan and China exchanged harsh words in Abe’s first month back in power over an alleged radar lock of a Chinese fighter plane on a JMSDF vessel, an act that might have escalated into a shooting conflict had it not been handled with restraint. That the Abe government chose to respond to this provocation with a harshly worded diplomatic protest and criticism of China in the Diet and not with military force or even economic sanctions belied the war-mongering reputation ascribed to Abe. In addition, China’s actions elsewhere in the region, in particular in the South China Sea with rival claimants to islands there, the Philippines and Vietnam in particular, further fueled concern in Japan over China’s military intentions, lending credence to Abe’s call for Japan to increase its military spending, to develop new capabilities, and to adapt existing security practices to a more hostile environment. North Korea’s continued military provocations in Japan’s neighborhood also facilitated an expanded security agenda—as both had in the period of DPJ rule.

Developments in the national security environment beyond Japan’s immediate region also facilitated the Abe government’s agenda of developing greater military capabilities and streamlined security practices. Under the previous DPJ government, Japan’s NDPG of 2010 had set out the new concept of gray-zone conflict in the context of fears over the Senkaku dispute, but in the world beyond Japan’s immediate neighborhood instances of gray-zone conflict actually emerged during Abe’s second term. In particular, Russia’s stealth invasion of Crimea and eastern Ukraine in 2014 alarmed many Japanese for the parallels they imagined in the context of how stealth Chinese paramilitary forces might invade the Senkaku Islands—with seeming US acquiescence to Russia’s actions stoking fears that US action in a Senkaku dispute would similarly be limited to rhetoric.6 US attention to renewed conflict in the Middle East also created concern in Japan that the stated rebalance of US military forces to Asia would not be forthcoming.

Important New Security Institutions and Practices, 2013 to 2015

The speed and skill with which the second Abe government enacted a series of changes to national security policies and practices was remarkable, especially since similar efforts his first cabinet made in this area were markedly unsuccessful in 2006 to 2007. Undoubtedly part of these achievements was due to lessons learned in effective governance and policy making from his first experience, a second chance few elected leaders are granted. The changed nature of the political opposition also surely played an important role, however, with a popular new political party rising to the right of the LDP, the JRP (Nippon Isshin no Kai), and the dovish challenge of the left wing of the DPJ and SDP in decline. In addition, as discussed in chapter 3, the international environment Japan faced had notably deteriorated in the six years since Abe had last served as prime minister, leading to further impetus for policy shift—though, as discussed later in the chapter, policy responses informed by the postwar legacy of antimilitarism continued to be preferred by the majority of the Japanese public.

Even in his second attempt to enact sweeping security legislation, however, Abe and his supporters did not get everything they wanted. Indeed, part of his success in his second term was the result of asking for less. For example, in his first term in 2006 to 2007, the Abe government sought to formally revise Article Nine of Japan’s constitution to allow for expanded military roles for Japan beyond strict self-defense. His government did achieve passing legislation that established the formal process for the required national referendum to revise the constitution but lost control of the Upper House in the meantime, making the national referendum legislation moot (at least for the time being). In the new Abe administration, Abe sought the lesser goal of reinterpreting the constitution to allow for Japan to play new roles in CSD and succeeded in this attempt—though he had to compromise even further in terms of the scope of the reinterpretation. This reinterpretation was implemented in two phases: the cabinet issued its decision to pursue this approach on July 1, 2014, and legislation to enact this reinterpretation was approved in the Diet in September 2015 after discussions in the party and coalition in the spring of 2015 and deliberation in the Diet in the summer of that year. New thinking related to military security was evident in this period, including willingness across political parties and societal actors to reconsider old taboos. Still, the three important historical legacies of the postwar period limited Abe’s success in making further changes and altered the scope of the resulting changes his government was able to enact.

Establishment of the NSC and Related Legislation

The new NSC and publishing of a formal national security strategy are important indicators of Japan’s security renaissance. They indicate a new willingness to consider approaches to managing Japan’s national security that transcend old taboos, and they enlarge Japan’s broader approach to security in their own right. Under the NSC, the Japanese government for the first time has a standing body—the National Security Secretariat (NSS)—that seeks to coordinate aspects of Japan’s military security strategy across government and not just at a time of crisis.7 It also has a formal counterpart to the US National Security Advisor in the position of the secretary-general of the NSS, the first of whom being the former chair of the advisory panel that led to the establishment of the NSC, former senior MOFA official Shotarō Yachi.

Japan has long considered security in a comprehensive manner, integrating issues like energy security and economic security, and was a global leader in the push to consider human security in the post–Cold War era8—but this new approach is different: it explicitly includes military advisers into the process of crafting Japan’s security policies and considers more explicitly military power as an aspect of broader foreign policy objectives. The Japanese government previously had a body called the Security Council, established in 1986 as one of Prime Minister Nakasone’s attempts to strengthen Japan’s security bureaucracy, but it was not a standing body and lacked a secretariat to provide analysis and policy suggestions independent of its constituent ministries; moreover, as noted in the East Asian Strategic Review 2014,” “the mere fact of its meeting was considered newsworthy” for the former Security Council.9

At the core of the new NSC format are the secretary-general of the NSS, two deputy secretaries-general, the roughly seventy staff members of the NSS drawn from across government, and the regular meetings of the “Four-Minister Meeting,” consisting of the prime minister, the chief cabinet secretary, and the ministers of foreign affairs and defense. Under Abe, this Four-Minister Meeting is held roughly every two weeks, serving as what Japanese defense planning documents describe as “the control tower for foreign and defense policies concerning national security.”10 In addition, a “Nine-Minister Meeting” is also part of the institutional structure and is intended to provide a venue for broader consultation on national security issues that would benefit from a broader range of input from ministries such as METI and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism (which has oversight over the JCG). The East Asian Strategic Review 2014 offers China policy as an example of an issue where broader coordination may be desirable, citing the case of the rare earths export ban imposed by China at the time of the 2010 Fishing Trawler Incident related to the Senkaku Islands dispute.11

Through the NSC and its roughly seventy-member secretariat, members of the JSDF are playing a larger role in Japan’s national security planning. This is happening, of course, under civilian control of the MOD, cabinet, and Diet oversight—but this is new for Japan, and it is happening largely without significant opposition (as opposed to the huge public protests over other parts of Abe’s security policy agenda). In practice, Japan has begun to use its military prowess—in particular its advanced technology and practical working knowledge and training—as one new fledgling arm of its foreign policy. “Seamless” is one of the primary buzzwords of the NSS, the 2013 NDPG, and the US-Japan defense guidelines in the context of different branches of the military working together more effectively—but the concept is also applied to Japan’s new seamless approach across government to considering military capabilities in its broader foreign policy.

Several practical complications had to be confronted and addressed to move toward this more seamless approach to Japan’s crafting of its military-security policies. One was the pervasive bureaucratic stove-piping endemic in the Japanese government system and the related and strong rivalries among Japan’s powerful ministries. The question of who would be represented in the Four-Minister Meeting, for example, generated years of discussion and debate—including over arriving at the final number of four. This was not primarily about defense politics, however, but rather bureaucratic politics. The creation of the NSC also marked another step forward for the MOD, which had risen to ministry status only in January 2007 (under the first Abe administration). At the same time, however, the MOD also lost some bureaucratic power in the new institutional arrangements vis-à-vis uniformed officers of the JSDF, which technically are supervised by the MOD but have greater latitude to affect policy within the NSC framework.

A second practical complication to operating a cross-ministry coordinating body for national security is the expanded need to share information across ministry boundaries. One challenge to this process is simply the bureaucratic rivalries just alluded to, but another, which invokes Japan’s wartime legacy, is the need to designate state secrets in order to protect information security among a wider group of individuals across ministries and agencies.

In the years leading up to and including World War II, the Japanese government increasingly designated information as state secrets as a way to silence and even imprison opponents to the fascist-militarist regime that hijacked Japanese democracy in those years. Even the suggestion of creating such a government-wide system of secrets with criminal penalties for divulging such information to the media or general public generated substantial opposition at multiple times in the recent past, including when the DPJ floated the idea when it was in power. This practical imperative also evokes the complex postwar US-Japan legacy, given that the United States has long been pressuring Japan to address the information security gap in its policy-making structure.12 Within the JSDF and MOD the United States succeeded in getting the Japanese government to create higher penalties for release of classified information from those organizations, but no such system had existed across ministries until the specially designated secrets (SDS) law passed in the Diet—under great opposition in the Diet and among the general public—in December 2013 with an implementation date of December 2014. As explained in the 2014 defense white paper: “In order to protect information on Japan’s defense and foreign affairs, as well as the prevention of designated harmful activities (e.g., counter-intelligence) and terrorism, which requires special secrecy, the act stipulates: (1) designation of Specially Designated Secrets by head of administrative organs; (2) security clearance for personnel that handle Specially Designated Secrets in duty; (3) establishment of a framework for providing or sharing Specially Designated Secrets within and outside administrative organs; and (4) penalties for unauthorized disclosure of Specially Designated Secrets.”13

Introduction of this legislation into the Diet resulted in the first extended battle over Abe’s national security agenda, both in the Diet and on the streets. In what would prove to be a precursor to the even larger demonstrations and divisiveness in the Diet over new security legislation introduced in the summer of 2015, activists employed a wide range of new social media tactics together with old-school demonstration tactics popular in the 1960s student-led movements protesting Japan’s involvement with US military action abroad. The new SEALDs student group illustrates this combination of tactics and also how the renaissance in security attitudes in contemporary Japan remains rooted in the past.14 One result of this activism was a one-year period added to the legislation to develop a set of policies that would protect civil liberties and promote transparency, though this addition did little to quell the opposition, who continued to characterize the legislation as having been rammed through the Diet and not adequately addressing civil liberties concerns. Also foreshadowing themes that would reemerge with the introduction of new security legislation in the Diet in the summer of 2015, concerns over the constitutionality of the proposed legislation would play a central role in the protests—including condemnation by the Japan Federation of Bar Associations.15 Moreover, evoking Japan’s militarist past was also evident, such as in a statement by former Nobel laureates that included the charge that “the Abe government’s political stance bears a close resemblance to the prewar Japanese government’s clamping down on freedom of speech and thought and rushing into war.”16

In sum, the creation of the NSC and passage of the SDS law show a continued ambivalence among the general public over new security practices. There was a tacit acceptance of the need for the NSC but strong opposition to the secrets law. A changed domestic configuration of power allowed for the passage of both, however—though the Abe government did pay a short-term price in its popularity with the passage of the latter.

A Formal National Security Strategy, New NDPG and MTDP

Japan’s first formal national security strategy, the new NDPG, and related MTDP adopted in December 2013 in conjunction with the establishment of the NSC are other important indications of Japan’s development of greater military capabilities and operational processes as part of its security renaissance.

The national security strategy document, which sets out a comprehensive outline of the security challenges Japan should consider and Japan’s strategic thinking in terms of policy responses, is framed in terms of “proactive contributions to peace” but devotes the bulk of its policy prescriptions to three aspects of strengthening and expanding Japan’s defense capabilities and roles: (1) the JSDF and other government institutions related national defense, (2) the US-Japan alliance, and (3) other “partners for peace” in the region and beyond. From this broad template, numerous specific policy initiatives follow, including in the five areas discussed in the following.17

The 2013 NDPG builds on innovative concepts initially set out under the 2010 NDPG; continuity is more evident than change. This continuity underscores the cross-party agreement over security evident in Japan today at the conceptual level (though, obviously, not always at the practical level—as seen in the frequent contentious Diet debates and street demonstrations during Abe’s second term). The 2013 NDPG seeks to move the branches of the JSDF and the JCG not just to more effective jointness—institutionalized by the creation of the Joint Staff Office, among other innovations of the 2010 NDPG—but also to truly seamless coordination, including in government institutions (as facilitated by the NSC) and in the US-Japan alliance (as set out in the subsequent 2015 US-Japan Guidelines for Defense Cooperation). The 2013 NDPG also builds on the 2010 concepts of dynamic defense and gray-zone defenses to build what is thought to be a more effective deterrent based both on the quantity and on the quality of assets under the expanded concept of a dynamic joint defense force.18

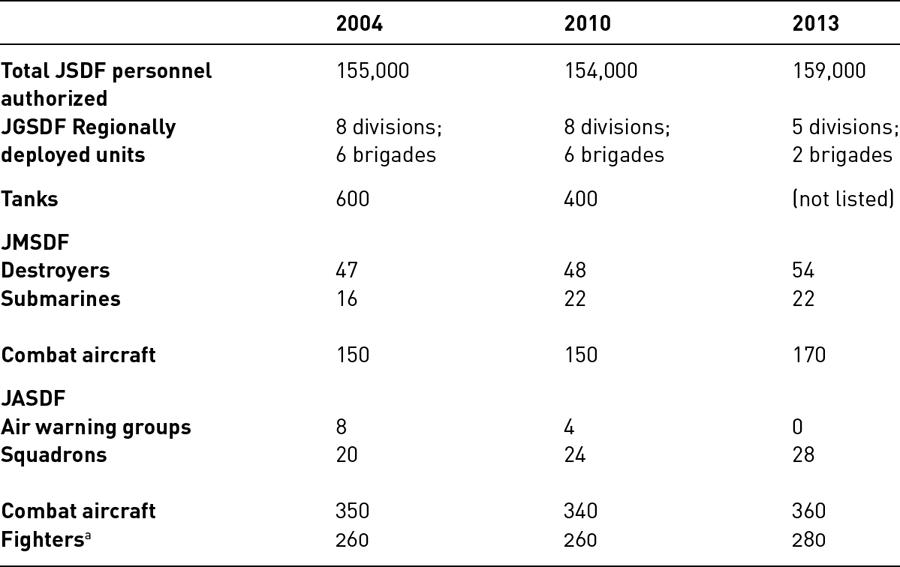

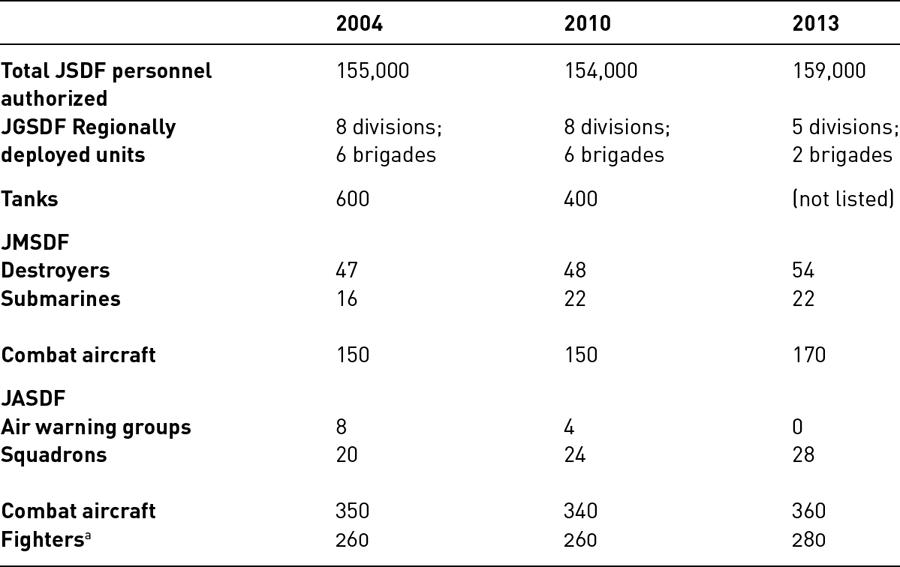

Beyond concepts, the 2013 NDPG and companion MTDP set out to further expand JSDF capabilities through the acquisition of six additional destroyers beyond the 2010 NDPG and the continued plan to acquire six more submarines (which had been the as yet unrealized goal from the 2010 NDPG). (See table 5.1 for a comparison of the major acquisitions set out in the 2004, 2010, and 2013 NDPGs.) Moreover, the additional destroyers will be of the new destroyer type that includes anti-mine capabilities and a towed array sonar system. The shift of JSDF deployment to the southwest deepens in the new NDPG. The JGSDF sees three fewer regionally deployed JGSDF divisions and six fewer regionally deployed brigades, in favor of additional “rapid deployment divisions and brigades” as well as the creation three new types of brigades, one each for airborne, helicopter, and “amphibious rapid deployment.” The number of combat aircraft also has been increased under the higher defense budget, with an additional squadron of F-15 fighter aircraft positioned at the Naha Air Base in Okinawa. Defense of Japan 2014 outlines a number of other additional capability enhancements set out in the NDPG and MTDP,19 some of which are possible via shifting resources (as seen over the past decade of capability enhancements) and others possible only because of the increasing defense budget.

TABLE 5.1 NDPG comparison: Personnel and major equipment

Source: Adapted from Ministry of Defense, Defense of Japan 2014, 151–52.

Note: Some of the values are listed as approximate in Defense of Japan 2014.

a Subset of combat aircraft.

Finally, the 2013 NDPG links these conceptual and capabilities developments by seeking to further streamline defense institutions and practices to provide for the truly seamless operating posture envisioned in the 2013 national security strategy.20

Additional Security-Related Legislation

Beyond these core defense policy innovations of Abe’s first year in office, the Abe government implemented a series of other policy changes to long-standing practices related to national security in an effort to effect a more “proactive pacifism”—in particular, relaxation of arms export restrictions beyond that implemented by the DPJ government in 2011, new guiding legislation on the use of outer space for defensive purposes beyond relaxations implemented in 2009 at the end of the last LDP-led government, and a new charter to guide Japan’s ODA policy to allow for more seamless coordination of Japan’s development assistance and security capacity building. Each of these adaptations to past practice helps to implement the broader strategy set out in the national security strategy and illustrates the renaissance in contemporary Japanese security practice.

Contrary to the shorthand often seen in the media, Japan still very much has strict arms export restrictions, though they are framed in a more proactive way as “Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology.”21 The first principle casts a wide net of areas where weapons and technology may not be exported—including to countries currently involved in a conflict that the United Nations is involved in addressing and countries under sanctions. The second principle, “overseas transfer of defense equipment and technology may be permitted in such cases as the transfer contributes to active promotion of peace and international cooperation,” may seem counterintuitive to those not used to long-standing Japanese discourse on security22—in other words, Japanese firms should export weapons only to promote peace. This second principle adds that such exports should also promote Japan’s national interests, another high bar for a private firm. Japan is unlikely to become a major arms exporter because of such remaining restrictions as well as of the internal nature of the defense industry in Japan, which is highly diffuse across companies that focus on nondefense business and which currently lacks a competitive cost structure and international marketing savvy.23 Similarly, in outer space policy the changes made to past restrictions do allow for some increased defensive use of outer space for activities like satellite surveillance at military-grade resolution, but Japan remains bound by the Outer Space Treaty of 1967—and its own antimilitarist attitudes—which prohibits space-based weapons.24

Japan’s new ODA charter, adopted in February 2015, also continues to stress long-standing practices, which include an expressed belief in the connection between peace and development.25 In the latest iteration, this connection is made more explicit and allows for some development assistance that contributes to capacity building that may also have a limited military use—such as a civilian airport or seaport also used by military aircraft and vessels. Thus, a greater flexibility of thinking about new approaches is evident.26 Even Abe’s choice of the first new president in years of the JICA, the principal ODA institution in the Japanese government, illustrates this thinking: Akihiko Tanaka is a professor at the University of Tokyo who specializes in Japanese security, not development or ODA policy; his successor, Shin’ichi Kitaoka, also a former professor, was the deputy chairman of Abe’s Advisory Panel on the Reconstruction of the Legal Basis for Security. Still, the new ODA charter is quite clear that Japanese ODA may not be provided for facilities or equipment solely for military use. The Japanese government has never provided weapons as a part of its ODA, and that prohibition remains.

These many security policy innovations enacted in just three years, from 2013 to 2015, will create a lasting legacy for future Japanese political leadership. The office of the prime minister (kantei) in particular now has many more tools at its disposal to execute foreign policy and diplomacy that include a military component. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that any of these policies will be reversed by future governments as each of the policies was the result of significant compromise informed by the legacies of the past. These legacies, however, have ensured that Japan’s security renaissance is not at all a reflection of an entirely new Japanese approach to military security: even the one other significant policy innovation enacted in this period, the legislation allowing for CSD, will not result in Japan’s prime minister dispatching the JSDF abroad in the normal course of statecraft, as is the purview of Japan’s other major power peers, nor acquiring weapons amassed in Japan that could be used to threaten Japan’s neighbors to alter their policies.27

Renewed Concerns About Japan’s Handling Under Abe of Its Militarist Past

The scale of expansion of Japan’s security roles, institutions, and capabilities under Abe, plus Abe’s return to power itself, has led to increased questioning and activism related to imperial Japan’s campaign of brutal expansion across East Asia. Vocal, organized, and divisive activism for Japan to better address and apologize for its past conduct has been apparent throughout the postwar period but has again risen to prominence since Abe resumed power in December 2012.

Causes and Consequences of a Renewed Focus on Japan’s Past

What has been the effect of these history issues on Abe’s security policy strategies and Japan’s new proactive contributions to peace? The broad coverage of the so-called history issues of Japan’s past in the Japanese and global media and tense relations between Japan and its immediate neighbors has not halted important developments in Japan’s security renaissance. To the contrary—much like during the Koizumi years, where Japan’s relations with its immediate neighbors were chilly but the relationship with the United States and countries further afield were strong—Japan’s security policy made substantial leaps in capabilities, institutions, and ambitions in the first three years of Abe’s second term. Abe himself met a record number of world leaders in the first year of his second term, including heads of state of all ten ASEAN countries (a first for a Japanese prime minister) as well as the heads of state of Australia, India, and dozens of other countries around the world. But, linking to the history-issue question, Abe did not hold bilateral meetings with the heads of state of either South Korea or China in his first year in office, and even by the fall of 2015, he had met these leaders only on the sidelines of other multilateral meetings where both leaders were already scheduled to be present. This stands in great contrast to Abe’s choice in his first term as prime minister of meeting China’s president Hu Jintao and South Korean president Roh Moo-hyun before meeting the president of the United States.

In the case of China, numerous other issues (number one being the territorial dispute) arguably drive frosty Japan-China relations with the history issues providing only a surface pretext. The differences between Japan and South Korea are more complex and more directly related to disagreements over past history—not just World War II but also back to the beginning of Japanese colonialism on the Korean Peninsula in 1910, and even the circumstances preceding that. The consequences of these problems are also more acute, as Japan and South Korea could, in principle, be working together to address shared security concerns, including in conjunction with their mutual ally, the United States.28 Instead, South Korea has found common cause with China over history issues, which has pushed Japan further away.

There are numerous, divergent causes of this renewed attention to Japan’s early-twentieth-century militarism. Japan’s increasingly proactive security policies are certainly one factor: as Japan engages in military-related activities in the region it once sought to conquer, emotions are bound to rise as citizens of the region are exposed to the new Japanese military forces, the JSDF, for the first time. But this explanation alone is inadequate. For example, it cannot explain why the JSDF was welcomed to provide post-typhoon disaster relief assistance in the Philippines—where the Japanese military caused great suffering—but not postearth-quake relief assistance in China (and in a region of China where Japanese forces hardly penetrated);29 nor can it explain why the comfort women issue is a massive political issue with South Korea but not with Taiwan or the Philippines, despite nationals of all three areas having been subjected to this treatment and all being allies of the United States today. Thus, new Japanese military capabilities and activities alone cannot explain the varied reactions of Japan’s neighbors to how Japan has atoned for its militarist past.

Three other factors help to explain why the historical legacy of Japan’s militarist and colonial past has risen to unusual prominence under the second Abe administration. Each has a divergent influence on Japan’s security renaissance. First, Abe himself, and especially members of his cabinet and other supporters, have made numerous inflammatory statements related to Japanese militarism that have called into question the Abe government’s commitment to respect previous Japanese government policies related to Japan’s militarist past. They have also questioned the way Japan’s militarist past is explained in school curricula and government narratives, provoking strong reaction both abroad and in Japan. Second, changes in Japanese domestic politics have empowered minority voices in the ruling LDP and also in the political opposition, an opposition that previously had been dominated by the political left but now also includes parties and strong voices from the right. Third, and of a different character, changes outside Japan—in particular politically motivated action by individuals and groups in China and South Korea—have sought to counter Japan’s regional influence or gain domestic political leverage by playing the “history card.” This has led to a reaction in Japan, by both the government and activists, to enact new policies or media campaigns to convey Japan’s view of history, which in some areas has created a vicious circle—such as the proclamation of Takeshima Day as a holiday to further assert Japan’s territorial claim or the back-and-forth over textbook depictions of Japan’s past.30

Revisionist Views of Abe and His Supporters

Abe’s return to power has led to strong criticism from those who believe Japan denies history. Invectives against Abe’s “far right” views are widely published not just on interest-group websites but also in mainstream journals and foreign mass media.31 A group of prominent scholars in Japan, the United States, and elsewhere signed and circulated a joint statement criticizing Japan and other states in the region for politicizing history, in particular over the comfort women issue.32 The prominent British specialist on Japanese security Christopher Hughes has described the “Abe Doctrine” as a “radical trajectory” for Japan and that “from autumn 2013 onwards, the full guise of Abe’s revisionist agenda . . . has become readily apparent.”33 Mainstream media in Japan, however, have been much more cautious to issue such invectives. Instead, mainstream criticism is limited largely to specific issues, such as Abe’s “intimidation diplomacy”34 or decision to visit Yasukuni Shrine in December 2013—a decision criticized even by the editor of the right-of-center Yomiuri newspaper.35

Abe has consistently sought to thread the needle between upholding past Japanese government statements of apology for Japan’s militarist past and calling into question the accuracy or necessity of such apologies. In his first term in office, Abe’s revisionist statements about Japan’s past conduct led to a highly unusual public rebuke by the US Congress, among other reactions discussed in chapter 4. In his second term as well, Abe made statements in the Diet and to supporters that called into question his commitment to the 1995 Murayama apology and the 1993 Kōnō statement, though his chief cabinet secretary repeatedly reaffirmed the Abe government’s adherence to those statements.36 In a March 2015 interview with the Washington Post, Abe again unequivocally stated his support for all Japan’s past major statements of reckoning with Japan’s wartime past;37 widespread skepticism nonetheless remains.

In June 2014, the LDP concluded a study of the circumstances leading to the issuing of the Kōnō statement in 1993. The study formally reaffirmed the content of the Kōnō statement while also noting the politicized nature of the drafting process of the time, which included consultation with the South Korean government about the specific language used.38 Such a political compromise pleased no one—South Korea and others in Japan and elsewhere in the world saw a watering down of the responsibilities Japan admitted in the Kōnō statement by the many qualifications explained in the new report, and a group of Abe’s supporters on the far right were unsatisfied that Abe appeared to back away from his earlier stridency on this issue. The circumstances surrounding the findings of the report—in which an Asahi newspaper journalist retracted some of his earlier reporting on this issue that had laid the foundation for aspects of the Kōnō statement and was excoriated by the far right in response (to the extent that the reporter was forced to resign from a teaching position and his daughter’s life was threatened)—provided further emotional fervor on the issue, despite it being “resolved” in Abe’s official public statements.

Abe’s compromise policy related to Yasukuni Shrine in his second term also pleased no one and led to lingering concerns on all sides. In Abe’s first term as prime minister, he sought to repair the damage done in relations with China during the Koizumi period, damage resulting in no small part from Koizumi’s repeated visits to the shrine. Two early examples of Abe’s outreach were his decisions to travel to Beijing to meet President Hu Jintao before traveling to Washington, DC, and to promise to refrain from visiting Yasukuni Shrine while prime minister, a promise he kept during his one year in office. (Abe had repeatedly visited the shrine when a Diet member before becoming prime minister.)

At the start of his second term in office, Abe again inherited a tense relationship with China from his predecessor, though this time due primarily to the escalation of the territorial dispute with China over the Senkaku Islands. Unlike in his first term, however, Abe had repeatedly promised his supporters on the campaign trail that he would visit Yasukuni Shrine while prime minister, and he refused to renounce this promise when China sought it as a precondition to scheduling a bilateral meeting between Abe and China’s new president, Xi Jinping. On December 23, 2013, Abe followed through on his promise to supporters and visited the shrine, leading to widespread criticism from abroad, including, unusually, from the US embassy in Tokyo. In 2014 and 2015 Abe refrained from again visiting the shrine, but he has not pledged that he would not visit again; moreover, in 2014, 2015, and 2016 he sent ceremonial offerings to the shrine to mark seasonal festival rites—again a sort of compromise that seemingly pleased no one.39

Abe sought to address lingering concerns about his position regarding Japan’s prewar and wartime history in an interview with the US journal Foreign Affairs. In response to the question, “Who is the real Abe,” he responded, “Let me set the record straight. Throughout my first and current terms as prime minister, I have expressed a number of times the deep remorse that I share for the tremendous damage and suffering Japan caused in the past to the people of many countries, particularly in Asia. I have explicitly said that, yet it made few headlines.” Yet on the sensitive issue of whether Japan committed “aggression,” he waffles somewhat, responding, “I have never said that Japan has not committed aggression. Yet at the same time, how best, or not, to define ‘aggression’ is none of my business. That’s what historians ought to work on. I have been saying that our work is to discuss what kind of world we should create in the future.”40 Abe also would not commit as to whether or not he would visit Yasukuni Shrine in the future, and, in fact, he did make his first (and, to date, only) visit to the shrine as prime minister later that year.

In the months leading up to the seventieth anniversary of the end of World War II, the media speculated widely about which words Abe would use to mark the occasion. Interest was high because of both longstanding concerns over Abe’s views and Abe’s appointment of a special Advisory Panel on History to offer suggestions for how he should commemorate the seventieth anniversary, as discussed in chapter 2.41 In his seventieth anniversary statement, Abe sought a middle ground that led to criticism from both those seeking a more explicit apology for Japan’s past actions and those who wanted Abe to toe the line that Japan had apologized enough and that Japan’s future should be forward looking. (The full text of the statement is provided in appendix 3.) This approach follows an earlier pattern seen during his time in office in which he seeks to appeal to different constituencies that hold opposing views—sometimes in sequence, and sometimes (as in his seventieth anniversary statement) simultaneously. This further illustrates how the past as well as the future strongly shapes the ultimate nature of Japan’s security policy, and its security renaissance more broadly.

Beyond Abe himself, the company Abe keeps in his own cabinet and among political supporters has also led to charges that Abe is an extreme historical revisionist. Abe’s minister of education, culture, sports, science and technology—who leads the ministry that approves textbooks available for adoption by schools nationwide—was among those in the cabinet Abe chose after the December 2012 election who attracted special attention for his statements prior to joining the cabinet calling for the revoking of the Kōnō and Murayama apology statements and for his revisionist views of Japan’s wartime past.42 Numerous other cabinet members across the two Abe cabinets appointed in the period December 2012 to 2015 have also been reported to have previously called for revisions of history textbooks, repeal of the Kōnō statement, and other reforms that critics associate with Japan’s militarist past.43 Many are members of Diet groups strongly associated with such policy platforms, such as the nationalist organization Nippon Kaigi (the Japan Conference, thirteen of nineteen members of the first Abe cabinet), the Japan’s Future and Textbook group (eleven of nineteen members of the first Abe cabinet), and the Worshipping at Yasukuni Shrine Together group (fifteen of nineteen members of the first Abe cabinet).44 As noted in a report by the US Congressional Research Service, “sizeable numbers of LDP lawmakers, including three Cabinet ministers, have periodically visited the Shrine on ceremonial days, including the sensitive day of August 15, the anniversary of Japan’s surrender in World War II.”45

The Apparent Rise of Nationalism and a Shift to the Political Right

The fact that in contemporary Japan there are competing political parties on the right of the political spectrum leads to greater pressure on the LDP and to more media attention to the conservative agenda such as the so-called history issues. This has led to widespread reporting outside Japan that there is a rising militarism, or at least rising nationalism, in present-day Japan. In Japan as well, there has been significant media attention to the concern over a rising nationalism (though not as often rising militarism),46 a claim that seems evident from the number of events covered in the media—such as group visits to Yasukuni Shrine by elected politicians and activist groups and the apparently growing number of anti-China and anti-Korea demonstrations and hate speech online.

The anecdotal impression of a rising nationalism in Japan is not as clear from more systematic research, however. For example, Japanese Cabinet Office polling on Japanese self-reported levels of “patriotic feeling” shows little variation in the period 2000 to 2013, though 2013 was the peak year for those describing a “strong affection,” at 58 percent.47 Over a third of those surveyed professed no feeling either way, and a small number reported a weak patriotic feeling. Glosserman and Snyder cite comparative studies of nationalist sentiment in Asia that show that “Japanese exhibit the lowest sense of patriotism among Asian nations. According to Asia Barometer, 27 percent of Japanese are ‘proud of their nationality,’ considerably less than the 46 percent of Chinese, 75 percent of Malays, and 93 percent of Thais. In the World Values Survey, Japan has the lowest percentage of people (24 percent) ‘proud of their country’ and willing to fight for their country (16 percent) among all countries polled.”48 Yet one could describe Japanese as looking for respect, as Glosserman and Snyder do when noting, “In 2013, 60 percent of Japanese felt that their country should be more respected in the world than it is.”49 Japanese themselves seem concerned about possible rising nationalism, based on the large number of opinion pieces and editorials that have appeared on this issue in major Japanese newspapers, which could be interpreted as a sign that more nationalist sentiment is visible and aired but could equally be seen as a moderate middle pushing back against such actions.

A related but more complex question is whether there has been a broader shift to the right in Japanese politics. As noted earlier, LDP “landslides” in the past two Lower House elections certainly imply such a shift—but a closer look at voting patterns yields a more mixed picture: there have not been more votes for parties on the right than in the past. The new opposition parties on the right have not fared well since their emergence, framing, and breakup on a regular basis. They have struggled to attract sustained support. Far right political candidates have not attracted mainstream voter support in the way seen in some European democracies in recent years. For example, in the Tokyo governor election in February 2014, Toshio Tamogami—the darling of the revisionist right who won a national essay contest with an essay espousing revisionist history views and who was ousted from the JSDF as a result—came in fourth of four major candidates, with only 12.4 percent of the vote, despite the media buzz covering the race. Moreover, as with recent national elections, voter turnout dropped sharply in this election from the previous Tokyo governor election, to 46.1 percent from 62.6 percent in the 2012 election, suggesting that voters were not excited about their candidate choices.

On broader issues associated with the conservative right beyond the security issues that are the focus of this book, there is evidence of support of rightist causes—such as xenophobia or anti-immigrant stances—but these issues do not seem to have resonated among the general public as they have in many European democracies, which in part is because of Japan’s very low levels of immigration and lack of a significant refugee population. Dislike of China is high (around 80 per cent—which is a big negative shift over time) and of the two Koreas as well (for which virulent racist diatribes and attitudes are especially evident in online forums and some print media) but not so of other foreign places—there is very high support for the United States and for cooperative approaches to outreach to Japan’s Asian neighbors. In a 2013 NHK survey, 70 percent of Japanese responded that “Japan still has much to learn from other countries,” belying the idea of widespread xenophobia beyond what has long been seen in the far right.

Overall, it is rather the two postwar historical legacies that have more deeply shaped Japan’s security policies under the second Abe administration, the legacy of antimilitarism and the legacy of the complex US-Japan security relationship.

The Postwar Legacy of Antimilitarism and Japan’s Security Renaissance

The publication of Japan’s first national security strategy marked a culmination of the first stage of a controversial and closely followed process of reformulation of Japan’s security policies under a reportedly nationalist and conservative government that has sought to respond to what it has characterized as “severe” security challenges.50 Yet the strategy adopted by Abe’s purportedly hypernationalist cabinet proclaims repeatedly Japan’s long-standing “peace-loving” policies and principles. For example, the text begins, “Japan will continue to adhere to the course that it has taken to date as a peace-loving nation, and as a major player in world politics and economy, continue even more proactively in securing peace, stability, and prosperity of the international community, while achieving its own security as well as peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific region as a ‘Proactive Contributor to Peace’ based on the principle of international cooperation. This is the fundamental principle of national security that Japan should stand to hold.”51

How can one reconcile this apparent contradiction? Why doesn’t a conservative prime minister with high levels of popular support pursue policies more in line with views widely reported to be central to his values and outlook? One answer is the strength of the historical legacy of antimilitarism—a second history issue that challenges the preferred agenda of the Abe government, in addition to the history issues related to Japan’s conduct in the years leading to World War II. By adopting a formal national security strategy document that seeks to guide Japan’s national security policy “over the next decade,” the Abe government itself provides another important illustration of how seventy years of antimilitarist security practices and institutions will continue to structure Japan’s security frame for years to come, despite powerful political actors seeking change not just to policy but also to Japan’s broader security identity.52

The Resilience of Antimilitarist Beliefs

Looking at the scope and scale of change in Japanese security policy in 2013 to 2016, observers might reasonably surmise that Japanese public attitudes about security have transformed in response to a growing number of threats facing Japan. In fact, extensive polling data convincingly demonstrate that Japanese views about how best to provide for Japan’s security have not been transformed by a more hostile environment.53 This lack of transformation of public attitudes is one reason why this book discusses a security “renaissance” rather than a more strident framing of a fundamental transformation of Japan’s security approaches.

For example, when asked how Japan should deal with the rising military threat from China, arguably the most important and well-covered security issue in the media, by far the most popular polling response—at 50 percent in 2014—was “strengthen relations with other countries in East Asia,” while “deal with China on the basis of deterrence provided by the US-Japan alliance” ranked the lowest, at only 5.2 percent in 2014 (down from 12.4 percent in 2010).54 “Deal with China through Japan’s own independent military capabilities” also ranked quite low and was on the decline, from 25 percent in 2012 to 9.5 percent in 2014. Thinking beyond China specifically, when NHK asked in July 2013 how best to guarantee Japan’s security, equal numbers of Japanese—about 45 percent each—chose “cooperate with the United Nations to build a global security system” and “have a degree of military power and rely on the US alliance.”55 Fewer than 5 percent of those polled said that Japan should rely exclusively on its own military power, roughly the same percentage as those who chose “have no military power and remain neutral.”

The important change in Japan’s security policies in the 1990s to contribute the JSDF to UNPKO on a limited basis is consonant with this support for a UN-centric system of global peace reflected in Japanese public opinion polls and is a “pillar” of Japanese foreign policy as long promoted by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. When the Asahi newspaper asked in 2013 and 2014 about acceptable roles for the JSDF overseas, there was near-universal support for helping at a time of a natural disaster (94 and 95 percent, respectively), but in relation to contemporary debates over the exercise of CSD, only a tiny minority supported “fighting on the front lines in combat with the United States (7 and 5 percent, respectively, so a decline year on year); only 17 percent of those polled thought it was acceptable for the JSDF to “provide weapons and fuel support to the US military overseas” (down from 20 percent in 2013).56

Clearly, despite a “renaissance” in Japan’s approach to its security in the past decade, Japanese views on the utility of the military in conflict resolution have not transformed by any means—but rather are grudgingly adapting to a new environment and in some cases being dragged into adapting by a determined political leadership. The postwar legacy of antimilitarism remains quite strong, as does ambivalence related to the utility of the US-Japan alliance for all aspects of Japan’s security.

This ambivalence—or outright opposition—extends even to policies that were in fact implemented under the Abe administration. For example, fewer than 30 percent of Japanese polled in 2013 and 2014 favored relaxing arms export restrictions—which the Abe government implemented in 2014—versus upward of 60 percent against.57 A poll conducted by Kyodo News in July 2015 showed 62 percent of respondents opposed the package of security legislation introduced into the Diet in June 2015—though it should be noted, the legislation is a complex package, and levels of support varied substantially based on how the polling questions were formulated.58 Approval for the Abe cabinet slumped by almost ten percentage points in the first month after the legislation was introduced, to 37.7 percent.59 Similarly high rates of disapproval were seen in response to the initial 2014 cabinet statement reinterpreting the constitution to allow for CSD and to the SDS law—both of which were also accompanied by public protests of, at minimum, tens of thousands of people in front of the Prime Minister’s residence and Diet building.

While Japan’s security identity has not been replaced by a new set of guiding principles, a new politics of security has been evident in Japan since the Koizumi period (2001–2006) that includes new attitudes about security among elites. Increased public discussion of alternative security policies—including those advocated by powerful political actors—is not the same as acceptance of these policies, however. For example, great media and public attention to the idea of constitutional revision of Article Nine in 2007 did not lead to revision of the constitution; similarly, discussion of Japan’s developing preemptive strike capabilities, for example, made headlines but did not result in a decision to pursue the idea.

Looking forward, in the remaining years of the second Abe administration policies rooted in the postwar antimilitarist legacy will no doubt continue to be challenged, both ideationally and institutionally. Moreover, substantial institutional and political constraints stand in the way of a realization of Abe’s full policy objectives vis-à-vis Japan’s future security practices. Ultimately even the large victory in the Upper House elections in July 2016 to attempt to implement one of his primary objectives of security policy: formal revision of Article Nine of the postwar constitution. Success in this area requires not just a two-thirds affirmative majority vote in both houses of the Diet but also a majority vote in a national referendum. Thus, even though the LDP—in informal coalition with other, smaller parties—was able to secure a two-thirds majority vote in the Diet that supports the idea of constitutional revision, there is yet another step, a step that seems unlikely to succeed based on extensive polling data on this question and the reaction to new security legislation passed in the Diet in September 2015. In the interim, however, a number of more limited challenges to the postwar antimilitarist legacy can be expected.

Article Nine and CSD

While Article Nine of the constitution—the so-called war-renouncing clause—plays a central role in anchoring Japan’s postwar antimilitarist legacy, political actors must interpret and uphold constitutional principles. The constitution has undergone reinterpretation numerous times in the postwar period and was significantly reinterpreted once again in the second year of the second Abe administration, when the Abe cabinet released a statement indicating a plan to reinterpret the constitution to allow for Japan to exercise its sovereign right to engage in CSD activities with other states closely aligned with Japan’s interests.60

At the start of his first term in office, Prime Minister Abe made clear that he would like the JSDF to engage in activities related to CSD. The Cabinet Legislative Bureau (CLB) interpretation of this issue, however, stood in conflict with Abe’s agenda. It reads (italics added), “International law permits a state to have the right of collective self-defense, which is the right to use force to stop an armed attack on a foreign country with which the state has close relations, even if the state itself is not under direct attack. Since Japan is a sovereign state, it naturally has the right of collective self-defense under international law. Nevertheless, the Japanese government believes that the exercise of the right of collective self-defense exceeds the limit on self-defense authorized under Article 9 of the Constitution and is not permissible.”61

With formal constitutional revision politically unattainable, Abe sought in his second term a reinterpretation of this opinion. The idea of a reinterpretation of a constitutional provision related to national security is not novel, protests from the left notwithstanding. In conjunction with earlier LDP efforts to expand Japan’s international security role, the CLB issued an interpretation that allowed for the JSDF to operate in “areas surrounding Japan” outside Japanese territory—with the restriction that the JSDF could not operate in the air, land, or sea territory of another state; it has also reconciled the constitutionality of Japan’s participation in an integrated missile defense system with the United States (which some saw as an exercise of CSD) and a range of other security-related issues over the years.

The July 1, 2014, cabinet decision that explicitly allows for the JSDF to participate in CSD activities with other states marks a significant change in a long-standing interpretation of appropriate security practices, though not as significant a change as Abe sought nor as is widely thought. The July 2014 cabinet decision that has been widely reported to have overturned Japan’s long-standing policy not to exercise its inherent right to CSD directs that such CSD actions would be undertaken in only extremely limited circumstances: only when not acting “threatens Japan’s survival” and “when there is no other appropriate means available to repel the attack” and, even then, that the JSDF is permitted “the use of force to the minimum extent necessary . . . in accordance with the basic logic of the Government’s view to date.”62 This result is far less than Abe and many of his supporters sought to achieve in this cabinet statement—but their views were overridden by opposition from within the ruling coalition (both in the LDP and especially from Kōmei) as well as influenced by strong public opposition.

Legislation to implement the July 2014 cabinet decision—one bill to amend twenty laws and another to create a legal framework for the JSDF to participate in international peace cooperation activities outside a UNPKO63—was introduced in the Diet in June 2015 and passed in September 2015, despite widespread public opposition and political demonstrations. Once again, however, draft legislation created by the Abe cabinet had to undergo several stages of watering down based on concerns expressed by backbenchers in the LDP, by coalition partner Kōmei, and during Diet interpolations—resulting in a set of policies that were far less than Abe originally sought, even after compromise the previous year on the 2014 cabinet statement. In one sense, it is therefore domestic politics and public opinion that played the direct role in limiting Abe’s policy ambitions—but it was the long-standing legacy of postwar antimilitarism that provided the framing language, institutional barriers, and that garnered public support to reshape the preferences of a powerful political actor.

The Influence of Antimilitarism in Other New Security Practices

Beyond these constitutional issues, the Abe administration adopted three new government documents related to national security policy in December 2013, each of which illuminates Abe’s new approaches to security. The new NDPG and related MTDP continue the policies set out in the last published NDPG of December 2010 but also push further Abe’s preference for a more activist security policy for Japan and a Japan that possesses greater military capabilities. However, the increase is fairly limited and clearly framed with the historical legacy of antimilitarist security practices in mind. The Japanese government’s first published national security strategy and the creation of the new NSC also rub against the legacy of antimilitarism though at this point have been adapted to not challenge this legacy overtly. It is illuminating of Japan’s postwar security identity that Japan has not even had such a formal strategy document in the past seventy years, illustrating how military policy was not seen as a core tool to promote the national interest—though the MOD (and, prior to that, the Japan Defense Agency) had developed military defense guidelines by way of the aforementioned NDPG since 1976, which have become increasingly detailed and strategic as they have been updated over the years, especially the 2004, 2010, and 2013 versions. This new formal national security strategy is crafted by a new institution, the NSC, operating within the Cabinet Secretariat and including representatives from ministries other than the MOD. The prospect of integrating military strategy into broad Japanese national objectives could mark a significant shift in Japan’s approach to military security, but whether this is what actually takes place in this new institution and future iterations of this core strategy document remains to be seen; the first attempt does not appear substantially different from earlier NDPGs, though it officially now expresses a more whole-of-government approach as the product of an internal cabinet body. At this point, however, Japanese policy makers certainly have many more tools at their disposal for utilizing military power to achieve broader national objectives, crossing to some degree previous boundaries imposed by the postwar legacy of antimilitarism.

The rise in presence and prominence of JSDF officers in Japan’s defense planning is also a notable sign of Japan’s security renaissance and one that challenges old taboos. After the July 2014 cabinet statement related to CSD, the JMSDF assigned an officer to work with the US Department of Defense to enhance the operational integration of the US Navy and JMSDF in regional operations.64 The JASDF had already dispatched such a liaison to Washington the previous year under the Abe government.65 These examples, together with a general rise in responsibilities of uniformed JSDF officers in defense policy planning in the MOD and the new NSC, mark a significant shift from what was considered politically possible in pre-renaissance Japan. There were certainly precedents in the preceding years—from around the time of the last US-Japan defense guidelines in 199766—but the normalcy of civilian-military interactions in contemporary Japan (between the “uniforms” and the “suits”) is what marks the renaissance of the past decade.

New precedents related to civilian-military interaction continue to be set in the Abe second term, such as the first-ever public speeches of Japan’s top military officers in Washington, DC—both the chief of the JSDF Joint Staff Office, Admiral Katsutoshi Kawano, and the JMSDF chief of staff, Admiral Tomohisa Takei, delivered public lectures in uniform (and in English) in July 2015.67 In their lectures they reported an impressive number of high-level meetings with senior US government officials and military commanders and touted the benefits of expanded US-Japan military-to-military cooperation. That such high-level consultations are taking place is itself notable, but that they are being publicly touted is another indication of Japan’s security renaissance.

In addition to the aforementioned new NSC, the Abe government envisions an “upgrade” to the institutions underpinning the Japan-US security alliance through implementation of the new US-Japan Guidelines for Defense Cooperation adopted in April 2015. Institutionalized military cooperation with the United States has long been a controversial aspect of security policy in Japan but has grown less so in recent years. Still, the level of cooperation and the sorts of roles that Japan will play within the alliance framework continue to be issues that challenge Japan’s postwar antimilitarist legacy. As noted in a recent report by Japan’s National Institute for Defense Studies, “the scope to the US-Japan alliance has expanded from the ‘defense of Japan’ to ‘the Asia-Pacific region’ and thence to ‘global cooperation.’”68 The last significant expansion of US-Japan cooperation took place under the Koizumi administration with the dispatch of the JSDF abroad to support US combat operations (discussed in chapter 2), a decision that was quite controversial and ultimately very limited in scope.

The Abe government has also crafted, and seeks to expand, institutionalized security cooperation with other states in the region, building on recent developments with Australia in particular.69 Whether the Abe administration, or a future Japanese administration, will be able to routinize and expand such out-of-area cooperation—or development of “dynamic defense cooperation” during ordinary times and not only in emergencies—remains to be seen. The package of new security legislation passed in the Diet in September 2015 sets very narrow limits for JSDF cooperation with other states in the area of CSD, limiting such actions to cases that “threaten Japan’s survival,”70 an early concession to substantial opposition to the legislation that emerged early on. This legislation came into effect only in March 2016, after government bureaucrats devised procedures and new processes to enact the changes legislated to twenty existing laws. Some aspects of the legislation may not be acted upon until much later, however—depending on domestic politics and the evolving international situation. The core aspect of the legislation, regarding JSDF participation in CSD activity, would not actually take place unless Japan was gravely threatened. However, an important aspect of the passage of the new security legislation is that it enables Japan’s defense establishment to legally plan for possible security contingencies that would involve CSD and to develop bilateral and multilateral exercises to train for this possibility—something that has not previously been possible.

Other areas of greater cooperation, by contrast, though new, are easily reconciled with the past antimilitarist practices—such as increased cooperation in regional HADR and in addressing threats in cyberspace: both areas scheduled for deepened cooperation under the new US-Japan guidelines and new security legislation. The extent to which the JSDF can cooperate with countries other than the United States is also an important question raised in Japan’s new national security strategy, and in the 2010 and 2013 NDPGs. Such cooperation need not conflict with past antimilitarist security practices, but it could depending on how it is framed—particularly in areas related to CSD. An expansion of defense cooperation with other states would be a new development—and certainly would present a new image for Japan overseas—but security cooperation with states other than the United States in itself would not be an indication of identity shift; it would depend on the nature of that cooperation.

The Abe government also seeks to increase the capabilities of the JSDF—as evidenced in the 2013 NDPG and MTDP documents. The question of what capabilities the JSDF should have has been controversial since its creation in 1954 and has historically been rooted in the concept of “minimum force necessary for the defense of Japan.” What was considered minimally necessary is, of course, related to perceptions of threat and to evolving military technologies. For example, some technologies once considered solely military but that now have widespread civilian uses have become uncontroversial in use by the JSDF: satellite communications and surveillance satellites are examples. In addition, as international cooperation was a core mission of the MOD at the time it was established as a ministry, new capabilities needed for this mission also have become uncontroversial—such as heavy-lift air transport capabilities, which were once imagined as a threatening means to transport soldiers and weapons abroad are now seen as a way to deliver humanitarian assistance.

Other aspects of enhanced JSDF capabilities remain controversial in relation to the legacy of antimilitarism—such as overt strike capability. Such a capacity is reportedly desired by Prime Minister Abe but, notably, has not been directly requested in policy documents to date, suggesting a continued resilience of the antimilitarist legacy even in changed domestic and international political circumstances. Recent Cabinet Office polling similarly lends support to the idea that the Abe government must be cautious in this area. While longitudinal public opinion surveys conducted by the Cabinet Office show the number of Japanese who believe that JSDF capabilities “should be increased” has jumped significantly from 14.1 percent in January 2009 to 24.8 percent in January 201271 and to 29.9 percent in 2015,72 it is nonetheless notable that fewer than one-third of Japanese express this view.

The prioritizing of incremental change to security policies that can be articulated within the discourse of postwar practices rooted in antimilitarist rhetoric confirms the continued resilience of this historical legacy. Other, overlapping explanations for security policy continuity can be offered beyond the antimilitarist legacy—but the effect of the postwar antimilitarist legacy remains strong even in contemporary Japan under Prime Minister Abe and even in the midst of a security renaissance.

Recrafting the Legacy of the US-Japan Security Relationship for a New Era

Let the two of us, America and Japan, join our hands together and do our best to make the world a better, a much better, place to live. . . . Together, we can make a difference.

—Prime Minister Shinzō Abe, address to a joint meeting of the US Congress, April 29, 2015