Two-Minute Drill

Two-Minute Drill• Describe the Interfaces that Make Up the Core of the JDBC API (Including the Driver, Connection, Statement, and ResultSet Interfaces and Their Relationship to Provider Implementations)

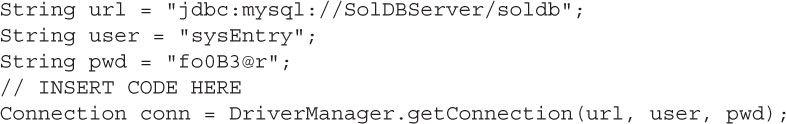

• Identify the Components Required to Connect to a Database Using the DriverManager Class (Including the JDBC URL)

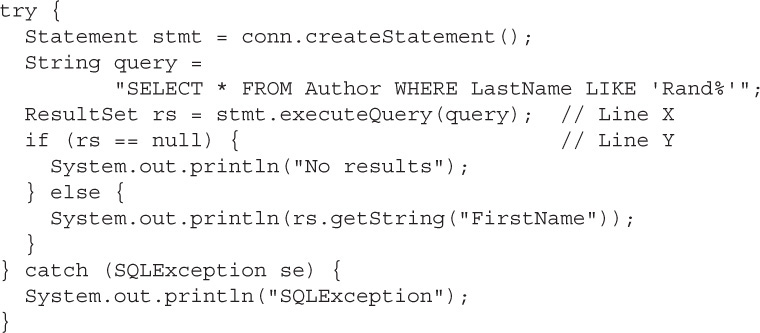

• Submit Queries and Read Results from the Database (Including Creating Statements; Returning Result Sets; Iterating Through the Results; and Properly Closing Result Sets, Statements, and Connections)

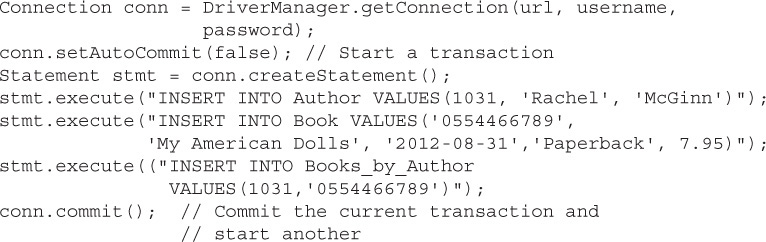

• Use JDBC Transactions (Including Disabling Auto-commit Mode, Committing and Rolling Back Transactions, and Setting and Rolling Back to Savepoints)

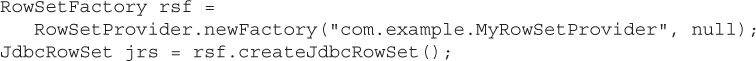

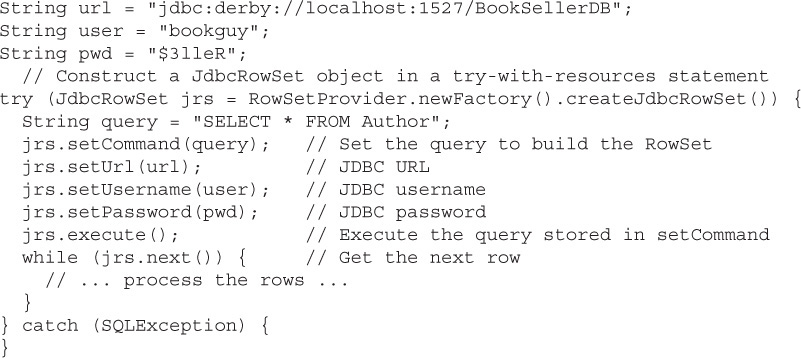

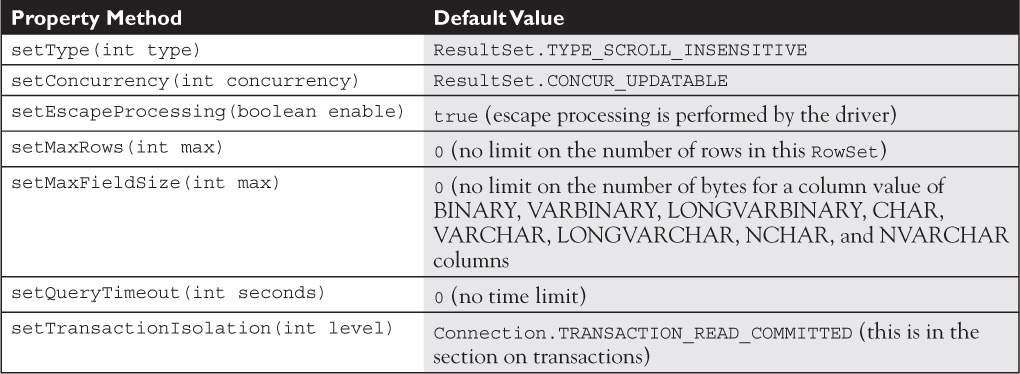

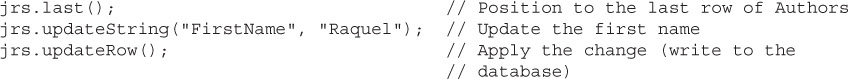

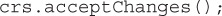

• Construct and Use RowSet Objects Using the RowSetProvider Class and the RowSetFactory Interface

• Create and Use PreparedStatement and CallableStatement Objects

Two-Minute Drill

Two-Minute Drill

Q&A Self Test

This chapter covers the JDBC API that was added for the Java SE 7 exam. The exam developers have long felt that this API is truly a core feature of the language, and being able to demonstrate proficiency with JDBC goes a long way toward demonstrating your skills as a Java programmer.

Interestingly, JDBC has been a part of the language since JDK version 1.1 (1997) when JDBC 1.0 was introduced. Since then, there has been a steady progression of updates to the API, roughly one major release for each even-numbered JDK release, with the last major update being JDBC 4.0, released in 2006 with Java SE 6. In Java SE 7, JDBC got some minor updates, and is now at version 4.1, which we’ll discuss a little later in the chapter. While the focus of the exam is on JDBC 4.x, there are some questions about the differences between loading a driver with a JDBC 3.0 and JDBC 4.x implementation, so we’ll talk about that as well.

The good news is that the exam is not going to test your ability to write SQL statements. That would be an exam all by itself (maybe even more than one—SQL is a BIG topic!). But you will need to recognize some basic SQL syntax and commands, so we’ll start by spending some time covering the basics of relational database systems and enough SQL to make you popular at database parties. If you feel you have experience with SQL and understand database concepts, you might just skim the first section or skip right to the first exam objective and dive right in.

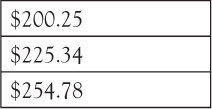

When you think of organizing information and storing it in some easily understood way, a spreadsheet or a table is often the first approach you might take. A spreadsheet or a table is a natural way of categorizing information: The first row of a table defines the sort of information that the table will hold, and each subsequent row contains a set of data that is related to the key we create on the left. For example, suppose you wanted to chart your monthly spending for several types of expenses (Table 15-1).

TABLE 15-1 Chart of Expenses

From the data in the chart, we can determine that your overall expenses are increasing month to month in the first three months of this year. But notice that without the table, without a relationship between the month and the data in the columns, you would just have a pile of receipts with no way to draw out important conclusions, such as

Assuming you drove the same number of miles per month, gas is getting pricey—maybe it is time to get a Prius.

Assuming you drove the same number of miles per month, gas is getting pricey—maybe it is time to get a Prius.

You are eating out more month to month (or the price of eating out is going up)—maybe it’s time to start doing some meal planning.

You are eating out more month to month (or the price of eating out is going up)—maybe it’s time to start doing some meal planning.

And maybe you need to be a little less social—that phone bill is high.

And maybe you need to be a little less social—that phone bill is high.

The point is that this small sample of data is the key to understanding a relational database system. A relational database is really just a software application designed to store and manipulate data in tables. The software itself is actually called a Relational Database Management System (RDBMS), but many people shorten that to just “database”—so know that going forward, when we refer to a database, we are actually talking about an RDBMS (the whole system). What the relational management system adds to a database is the ability to define relationships between tables. It also provides a language to get data in and out in a meaningful way.

Looking at the simple table in Table 15-1, we know that the data in the columns, Gas, EatingOut, Utilities, and Phone, are grouped by the months January, February, and so on. The month is unique to each row and identifies this row of data. In database parlance, the month is a “primary key.” A primary key is generally required for a database table to identify which row of the table you want, and to make sure that there are no duplicate rows.

Extending this a little further, if the data in Table 15-1 were stored in a database, I could ask the database (write a query) to give me all of the data for the month of January (again, my primary key is “month” for this table). I might write something like:

“Give me all of my expenses for January.”

The result would be something like:

This kind of query is what makes a database so powerful. With a relatively simple language, you can construct some really powerful queries in order to manipulate your data to tell a story. In most RDBMSs, this language is called the Structured Query Language (SQL). The same query we wrote out in a sentence earlier, would be expressed like this in SQL:

which can be translated to “select all of the columns (*) from my table named ‘Expenses’ where the month column is equal to the string ‘January’.” Let’s look a bit more at how we “talk” to a database and what other sorts of queries we can make with tables in a relational database.

There are three important concepts when working with a database:

Creating a connection to the database

Creating a connection to the database

Creating a statement to execute in the database

Creating a statement to execute in the database

Getting back a set of data that represents the results

Getting back a set of data that represents the results

Let’s look at these concepts in more detail.

Before we can communicate with the software that manages the database, before we can send it a query, we need to make a connection with the RDBMS itself. There are many different types of connections, and a lot of underlying technology to describe the connection itself, but in general, to communicate with an RDBMS, we need to open a connection using an IP address and port number to the database. Once we have established the connection, we need to send it some parameters (such as a username and password) to authenticate ourselves as a valid user of the RDBMS. Finally, assuming all went well, we can send queries through the connection. This is like logging into your online account at a bank. You provide some credentials, a username and password, and a connection is established and opened between you and the bank. Later in the chapter, when we start writing code, we’ll open a connection using a Java class called the DriverManager, and in one request, pass in the database name, our username, and password.

Once we have established a connection, we can use some type of application (usually provided by the database vendor) to send query statements to the database, have them executed in the database, and get a set of results returned. A set of results can be one row, as we saw before when we asked for the data from the month of January, or several rows. For example, suppose we wanted to see all of the Gas expenses from our Expenses table. We might query the database like this:

“Show me all of my Gas Expenses”

The set of results that would “return” from my query would be three rows, and each row would contain one column.

An important aspect of a database is that the data is presented back to you exactly the same way that it is stored. Since Gas expense is a column, the query will return three rows (one for January, one for February, and one for March). Note that because we did not ask the database to include the Month column in the results, all we got was the Gas column. The results do preserve the fact that Gas is a column and not a row, and in general, presents the data in the same row-and-column order that it is stored in the database.

Let’s look a bit more at the syntax of SQL, the language used to write queries in a database. There are really four basic SQL queries that we are going to use in this chapter, and that are common to manipulating data in a database. In summary, the SQL commands we are interested in are used to perform CRUD operations.

Like most terms presented in all caps, CRUD is an acronym, and means Create, Read, Update, and Delete. These are the four basic operations for data in a database. They are represented by four distinct SQL commands, detailed in Table 15-2.

TABLE 15-2 Example SQL CRUD Commands

Here is a quick explanation for the examples in Table 15-2:

INSERT Add a row to the table Expenses, and set each of the columns in the table to the values expressed in the parentheses.

INSERT Add a row to the table Expenses, and set each of the columns in the table to the values expressed in the parentheses.

SELECT with WHERE You have already seen the SELECT clause with a WHERE clause, so you know that this SQL statement returns a single row identified by the primary key—the Month column. Think of this statement as a refinement to Read—more like a Find or Find by primary key.

SELECT with WHERE You have already seen the SELECT clause with a WHERE clause, so you know that this SQL statement returns a single row identified by the primary key—the Month column. Think of this statement as a refinement to Read—more like a Find or Find by primary key.

SELECT When the SELECT clause does not have a WHERE clause, we are asking the database to return every row. Further, because we are using an asterisk (*) following the SELECT, we are asking for every column. Basically, it is a dump of the data shown in Table 15-1. Think of this statement as a Read All.

SELECT When the SELECT clause does not have a WHERE clause, we are asking the database to return every row. Further, because we are using an asterisk (*) following the SELECT, we are asking for every column. Basically, it is a dump of the data shown in Table 15-1. Think of this statement as a Read All.

UPDATE Change the data in the Phone and EatingOut cells to the new data provided for February.

UPDATE Change the data in the Phone and EatingOut cells to the new data provided for February.

DELETE Remove a row altogether from the database where the Month is April.

DELETE Remove a row altogether from the database where the Month is April.

Really, this is all the SQL you need to know for this chapter. There are many other SQL commands, but this is really the core set. If we need to go beyond this set of four commands in the chapter, we will cover them as they come up. Now, let’s look at a more detailed database example that we will use as the example set of tables for this chapter, using the data requirements of a small bookseller, Bob’s Books.

SQL commands, like SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, and so on, are case insensitive. So it is largely by convention (and one we will use in this chapter) to use all capital letters for SQL commands and key words, such as WHERE, FROM, LIKE, INTO, SET, and VALUES. SQL table names and column names, also called identifiers, can be case sensitive or case insensitive, depending upon the database. The example code shown in this chapter uses a case-insensitive database, so again, just for convention, we will use upper camel case, that is, the first letter of each noun capitalized and the rest in lowercase.

One final note about case—all databases preserve case when a string is delimited—that is, when they are enclosed in quotes. So a SQL clause that uses single or double quotation marks to delimit an identifier will preserve the case of the identifier.

In this section, we’ll describe a small database with a few tables and a few rows of data. As we work through the various JDBC topics in this chapter, we’ll work with this database.

Bob is a small bookseller who specializes in children’s books. Bob has designed his data around the need to sell his books online using a database (which one doesn’t really matter) and a Java application. Bob has decided to use the JDBC API to allow him to connect to a database and perform queries through a Java application.

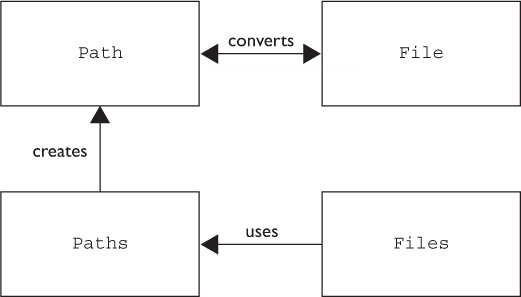

To start, let’s look at the organization of Bob’s data. In a database, the organization and specification of the tables is called the database schema (Figure 15-1). Bob’s is a relatively simple schema, and again, for the purposes of this chapter, we are going to concentrate on just four tables from Bob’s schema.

FIGURE 15-1 Bob’s BookSeller database schema

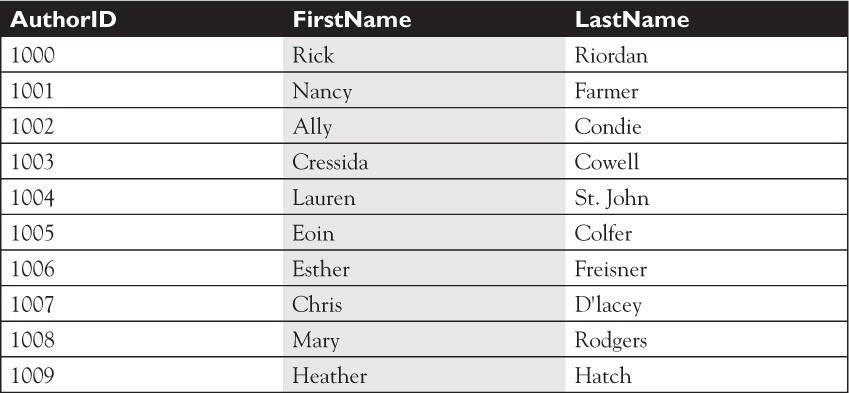

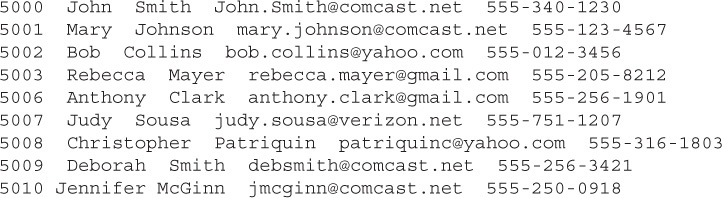

This is a relatively simple schema that represents a part of the database for a small bookstore. In the schema shown, there is a table for Customer (Table 15-3). This table stores data about Bob’s customers—a customer ID, first name and last name, an e-mail address, and phone number. Address and other information could be stored in another table.

TABLE 15-3 Bob’s Books Customer Table Sample Data

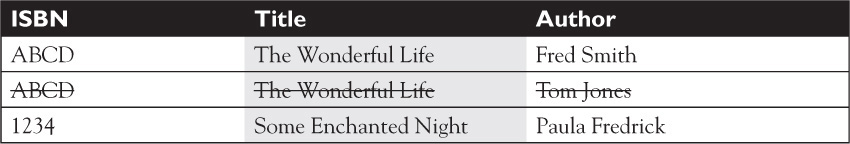

The next three tables we will look at represent the data required to store information about books that Bob sells. Because a book is a more complex set of data than a customer, we need to use one table for information about books, one for information about authors, and a third to create a relationship between books and authors.

Suppose that you tried to store a book in a single table with a column for the ISBN (International Standard Book Number), title, and author name. For many books, this would be fine. But what happens if a book has two authors? Or three authors? Remember that one requirement for a database table is a unique primary key, so you can’t simply repeat the ISBN in the table. In fact, having two rows with the same primary key will violate a key constraint in relational database design: The primary key of every row must be unique.

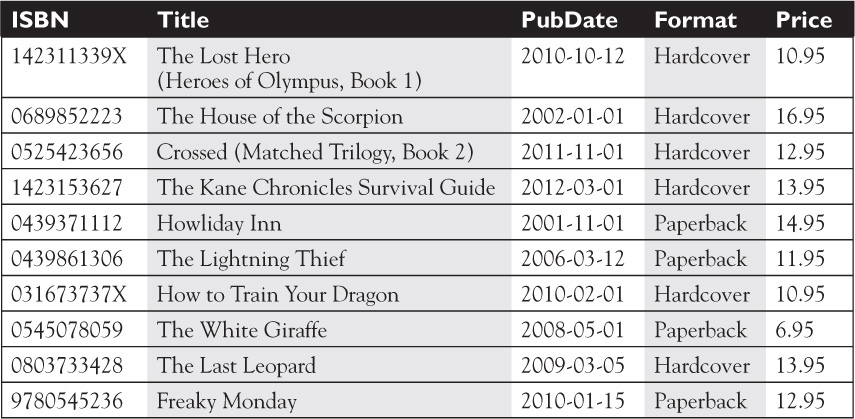

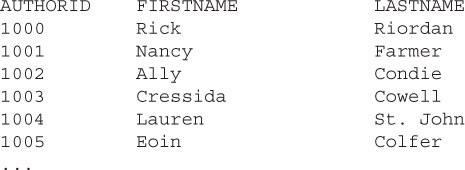

Instead, there needs to be a way to have a separate table of books and authors and some way to link them together. Bob addressed this issue by placing Books in one table (Table 15-4) and Authors (Table 15-5) in another. The primary key for Books is the ISBN number, and therefore, each Book entry will be unique. For the Author table, Bob is creating a unique AuthorID for each author in the table.

TABLE 15-4 Bob’s Books Sample Data for the “Books” Table

TABLE 15-5 Bob’s Books Author Table Sample Data for the “Authors” Table

To tie Authors to Books and Books to Authors, Bob has created a third table called Books_by_Author. This is a unique table type in a relational database. This table is called a jointable. In a join table, there are no primary keys—instead, all the columns represent data that can be used by other tables to create a relationship. These columns are referred to as foreign keys—they represent a primary key in another table. Looking at the last two rows of this table, you can see that the Book with the ISBN 9780545236 has two authors: author id 1008 (Mary Rodgers) and 1009 (Heather Hatch). Using this join table, we can combine the two sets of data without needing duplicate entries in either table. We’ll return to the concept of a join table later in the chapter.

A complete Bob’s Books database schema would include tables for publishers, addresses, stock, purchase orders, and other data that the store needs to run its business. But for our purposes, this part of the schema is sufficient. Using this schema, we can write SQL queries using the SQL CRUD commands you learned earlier.

To summarize, before looking at JDBC, you should now know about connections, statements, and result sets:

A connection is how an application communicates with a database.

A connection is how an application communicates with a database.

A statement is a SQL query that is executed on the database.

A statement is a SQL query that is executed on the database.

A result set is the data that is returned from a SELECT statement.

A result set is the data that is returned from a SELECT statement.

Having these concepts down, we can use Bob’s Books simple schema to frame some common uses of the JDBC API to submit SQL queries and get results in a Java application.

9.1 Describe the interfaces that make up the core of the JDBC API (including the Driver, Connection, Statement, and ResultSet interfaces and their relationship to provider implementations).

As we mentioned in the previous section, the purpose of a relational database is really threefold:

To provide storage for data in tables

To provide storage for data in tables

To provide a way to create relationships between the data—just as Bob did with the Authors, Books, and Books_by_Author tables

To provide a way to create relationships between the data—just as Bob did with the Authors, Books, and Books_by_Author tables

To provide a language that can be used to get the data out, update the data, remove the data, and create new data

To provide a language that can be used to get the data out, update the data, remove the data, and create new data

The purpose of JDBC is to provide an application programming interface (API) for Java developers to write Java applications that can access and manipulate relational databases and use SQL to perform CRUD operations.

Once you understand the basics of the JDBC API, you will be able to access a huge list of databases. One of the driving forces behind JDBC was to provide a standard way to access relational databases, but JDBC can also be used to access file systems and object-oriented data sources. The key is that the API provides an abstract view of a database connection, statements, and result sets. These concepts are represented in the API as interfaces in the java.sql package: Connection, Statement, and ResultSet, respectively. What these interfaces define are the contracts between you and the implementing class. In truth, you may not know (nor should you care) how the implementation class works. As long as the implementation class implements the interface you need, you are assured that the methods defined by the interface exist and you can invoke them.

The java.sql.Connection interface defines the contract for an object that represents the connection with a relational database system. Later, we will look at the methods of this contract, but for now, an instance of a Connection is what we need to communicate with the database. How the Connection interface is implemented is vendor dependent, and again, we don’t need to worry so much about the how—as long as the vendor follows the contract, we are assured that the object that represents a Connection will allow us to work with a database connection.

The Statement interface provides an abstraction of the functionality needed to get a SQL statement to execute on a database, and a ResultSet interface is an abstraction functionality needed to process a result set (the table of data) that is returned from the SQL query when the query involves a SQL SELECT statement.

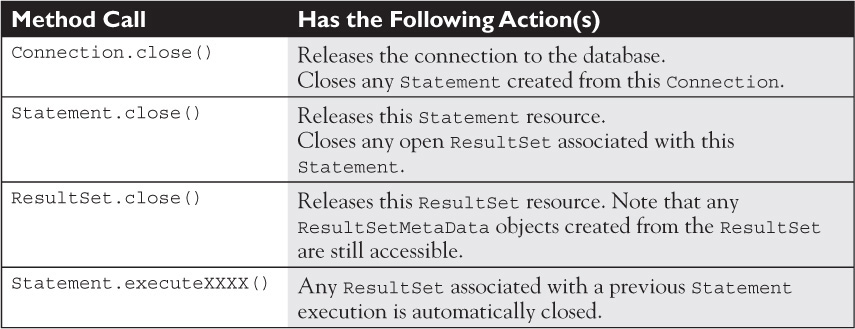

The implementation classes of Connection, Statement, ResultSet, and a number of other interfaces we will look at shortly are created by the vendor of the database we are using. The vendor understands their database product better than anyone else, so it makes sense that they create these classes. And, it allows the vendor to optimize or hide any special characteristics of their product. The collection of the implementation classes is called the JDBC driver. A JDBC driver (lowercase “d”) is the collection of classes required to support the API, whereas Driver (uppercase “D”) is one of the implementations required in a driver.

A JDBC driver is typically provided by the vendor in a JAR or ZIP file. The implementation classes of the driver must meet a minimum set of requirements in order to be JDBC compliant. The JDBC specification provides a list of the functionality that a vendor must support and what functionality a vendor may optionally support.

Here is a partial list of the requirements for a JDBC driver. For more details, please read the specification (JSR-221). Note that the details of implementing a JDBC driver are NOTon the exam.

Fully implement the interfaces:

Fully implement the interfaces: java.sql.Driver, java.sql .DatabaseMetaData, java.sql.ResultSetMetaData.

Implement the

Implement the java.sql.Connection interface. (Note that some methods are optional depending upon the SQL version the database supports—more on SQL versions later in the chapter.)

Implement the

Implement the java.sql.Statement, java.sql.PreparedStatement.

Implement the

Implement the java.sql.CallableStatement interfaces if the database supports stored procedures. Again, more on this interface later in the chapter.

Implement the

Implement the java.sql.ResultSet interface.

9.2 Identify the components required to connect to a database using the DriverManager class (including the JDBC URL)

Not all of the types defined in the JDBC API are interfaces. One important class for JDBC is the java.sql.DriverManager class. This concrete class is used to interact with a JDBC driver and return instances of Connection objects to you. Conceptually, the way this works is by using a design pattern called Factory. Next, we’ll look at DriverManager in more detail.

The DriverManager class is a concrete class in the JDBC API with static methods. You will recall that static or class methods can be invoked by other classes using the class name. One of those methods is getConnection(), which we look at next.

The DriverManager class is so named because it manages which JDBC driver implementation you get when you request an instance of a Connection through the getConnection() method.

There are several overloaded getConnection methods, but they all share one common parameter: a String URL. One pattern for getConnection is

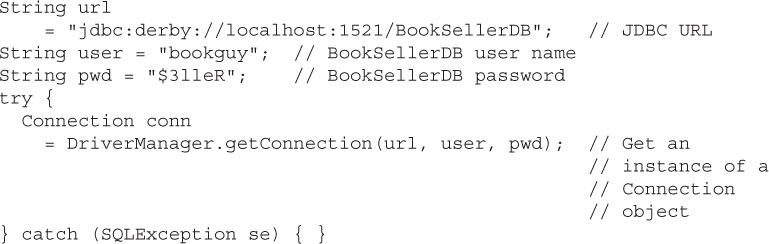

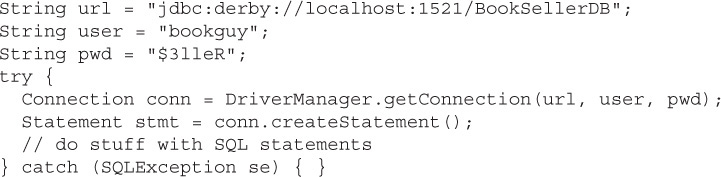

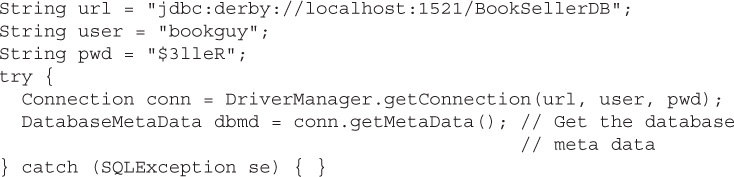

For example:

In this example, we are creating a connection to a Derby database, on a network, at a localhost address (on the local machine), at port number 1521, to a database called “BookSellerDB”, and we are using the credentials, “bookguy” as the user id, and “$3lleR” as the password. Don’t worry too much about the syntax of the URL right now—we’ll cover that soon.

It’s a horrible idea to hard-code a username and password in the getConnection() method. Obviously, anyone reading the code would then know the username and password to the database. A more secure way to handle database credentials would be to separate the code that produces the credentials from the code that makes the connection. So in some other class, you would use some type of authentication and authorization code to produce a set of credentials to allow access to the database.

For simplicity in the examples in the chapter, we’ll hard-code the username and password, but just keep in mind that on the job, this is not a best practice.

When you invoke the DriverManager’s getConnection() method, you are asking the DriverManager to try passing the first string in the statement, the driver URL, along with the username and password to each of the driver classes registered with the DriverManager in turn. If one of the driver classes recognizes the URL string, and the username and password are accepted, the driver returns an instance of a Connection object. If, however, the URL is incorrect, or the username and/or password are not correct, then the method will throw a SQLException. We’ll spend some time looking at SQLException later in this chapter.

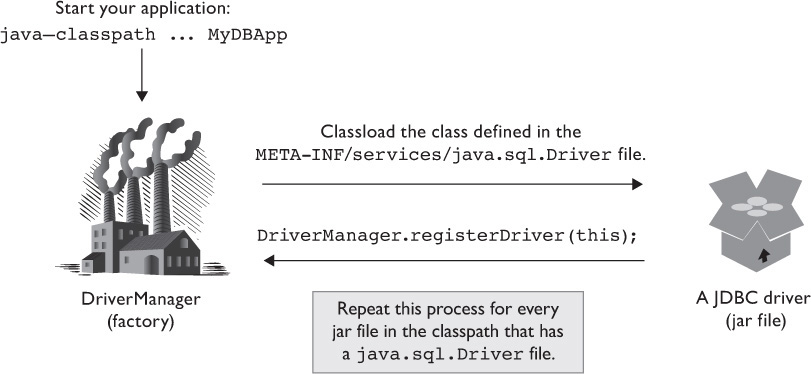

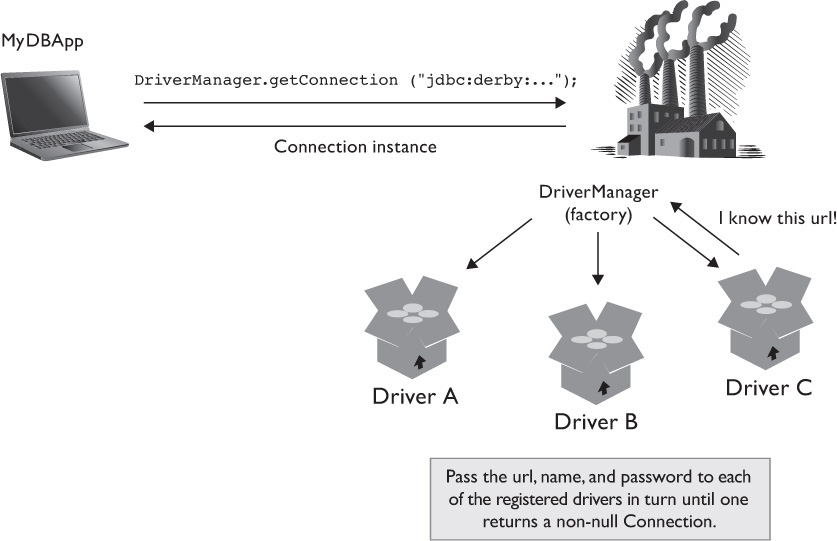

Because this part of the JDBC process is important to understand, and it involves a little Java magic, let’s spend some time diagramming how driver classes become “registered” with the DriverManager, as shown in Figure 15-2.

Figure 15-2 How JDBC drivers self-register with DriverManager

First, one or more JDBC drivers, in a JAR or ZIP file, are included in the classpath of your application. The DriverManager class uses a service provider mechanism to search the classpath for any JAR or ZIP files that contain a file named java.sql.Driver in the META-INF/services folder of the driver jar or zip. This is simply a text file that contains the full name of the class that the vendor used to implement the jdbc.sql.Driver interface. For example, for a Derby driver, the full name is org.apache.derby.jdbc.ClientDriver.

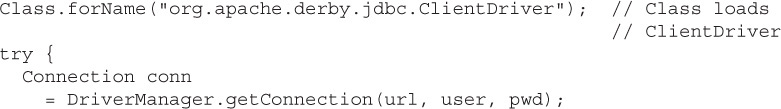

The DriverManager will then attempt to load the class it found in the java.sql.Driver file using the class loader:

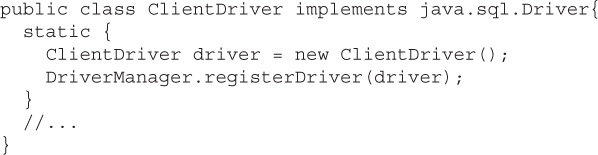

When the driver class is loaded, its static initialization block is executed. Per the JDBC specification, one of the first activities of a driver instance is to “self-register” with the DriverManager class by invoking a static method on DriverManager. The code (minus error handling) looks something like this:

This registers (stores) an instance of the Driver class into the DriverManager.

Now, when your application invokes the DriverManager.getConnection() method and passes a JDBC URL, username, and password to the method, the DriverManager simply invokes the connect() method on the registered Driver. If the connection was successful, the method returns a Connection object instance to DriverManager, which, in turn, passes that back to you.

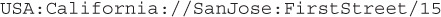

If there is more than one registered driver, the DriverManager calls each of the drivers in turn and attempts to get a Connection object from them, as shown in Figure 15-3.

FIGURE 15-3 How the DriverManager gets a Connection

The first driver that recognizes the JDBC URL and successfully creates a connection using the username and password will return an instance of a Connection object. If no drivers recognize the URL, username, and password combination, or if there are no registered drivers, then a SQLException is thrown instead.

To summarize:

The JVM loads the

The JVM loads the DriverManager class, a concrete class in the JDBC API.

The

The DriverManager class loads any instances of classes it finds in the META-INF/services/java.sql.Driver file of JAR/ZIP files on the classpath.

Driver classes call

Driver classes call DriverManager.register(this) to self-register with the DriverManager.

When the

When the DriverManager.getConnection(String url) method is invoked, DriverManager invokes the connect() method of each of these registered Driver instances with the URL string.

The first

The first Driver that successfully creates a connection with the URL returns an instance of a Connection object to the DriverManager.getConnection method invocation.

Let’s look at the JDBC URL syntax next.

The JDBC URL is what is used to determine which driver implementation to use for a given Connection. Think of the JDBC URL (uniform resource locator) as a way to narrow down the universe of possible drivers to one specific connection. For example, suppose you need to send a package to someone. In order to narrow the universe of possible addresses down to a single unique location, you would have to identify the country, the state, the city, the street, and perhaps a house or address number on your package:

This string indicates that the address you want is in the United States, California State, San Jose city, First Street, number 15.

JDBC URLs follow this same idea. To access Bob’s Books, we might write the URL like this:

The first part, jdbc, simply identifies that this is a JDBC URL (versus HTTP or something else). The second part indicates that driver vendor is derby driver. The third part indicates that the database is on the localhost of this machine (IP address 127.0.0.1), at port 1521, and the final part indicates that we are interested in the BookSellerDB database.

Just like street addresses, the reason we need this string is because JDBC was designed to work with multiple databases at once. Each of the JDBC database drivers will have a different URL, so we need to be able to pass the JDBC URL string to the DriverManager and ensure that the Connection returned was for the intended database instance.

Unfortunately, other than a requirement that the JDBC URL begin with “jdbc,” there is very little standard about a JDBC URL. Vendors may modify the URL to define characteristics for a particular driver implementation. The format of the JDBC URL is

In general, subprotocol is the vendor name; for example:

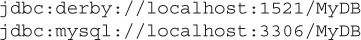

The subname field is where things get a bit more vendor specific. Some vendors use the subname to identify the hostname and port, followed by a database name. For example:

Other vendors may use the subname to identify additional context information about the driver. For example:

In any case, it is best to consult the documentation for your specific database vendor’s JDBC driver to determine the syntax of the URL.

We talked about how the DriverManager will scan the classpath for JAR files that contain the META-INF/services/java.sql.Driver file and use a classloader to load those drivers. This feature was introduced in the JDBC 4.0 specification. Prior to that, JDBC drivers were loaded manually by the application.

If you are using a JDBC driver that is an earlier version, say, a JDBC 3.0 driver, then you must explicitly load the class provided by the database vendor that implements the java.sql.Driver interface. Typically, the database vendor’s documentation would tell you what the driver class is. For example, if our Apache Derby JDBC driver were a 3.0 driver, you would manually load the Driver implementation class before calling the getConnection() method:

Note that using the Class.forName() method is compatible with both JDBC 3.0 and JDBC 4.0 drivers. It is simply not needed when the driver supports 4.0.

Here is a quick summary of what we have discussed so far:

Before you can start working with JDBC, creating queries and getting results, you must first establish a connection.

Before you can start working with JDBC, creating queries and getting results, you must first establish a connection.

In order to establish a connection, you must have a JDBC driver.

In order to establish a connection, you must have a JDBC driver.

If your JDBC driver is a JDBC 3.0 driver, then you are required to explicitly load the driver in your code using

If your JDBC driver is a JDBC 3.0 driver, then you are required to explicitly load the driver in your code using Class.forName() and the fully qualified path of the Driver implementation class.

If your JDBC driver is a JDBC 4.0 driver, then simply include the driver (jar or zip) in the classpath.

If your JDBC driver is a JDBC 4.0 driver, then simply include the driver (jar or zip) in the classpath.

9.3 Submit queries and read results from the database (including creating statements; returning result sets; iterating through the results; and properly closing result sets, statements, and connections).

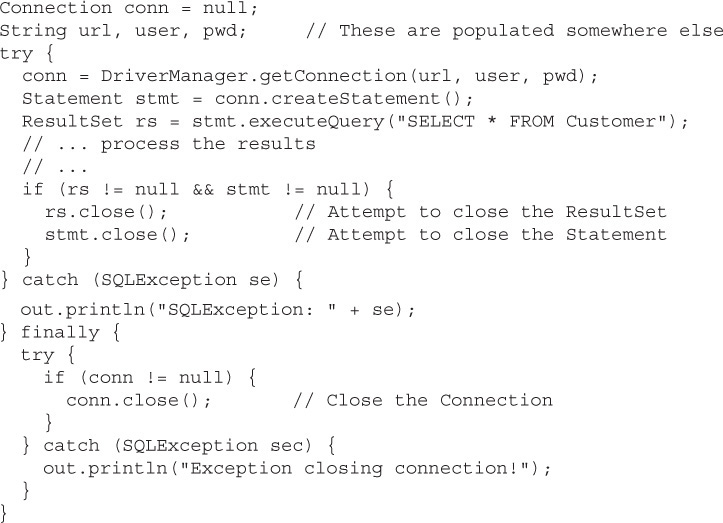

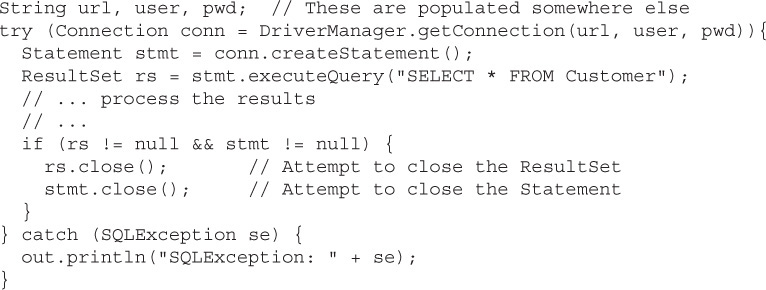

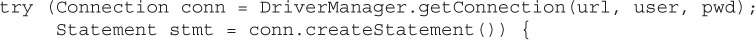

In this section, we’ll explore the JDBC API in much greater detail. We will start by looking at a simple example using the Connection, Statement, and ResultSet interfaces to pull together what we’ve learned so far in this chapter. Then we’ll do a deep dive into Statements and ResultSets.

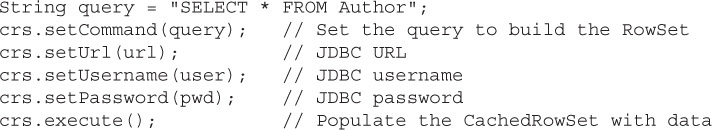

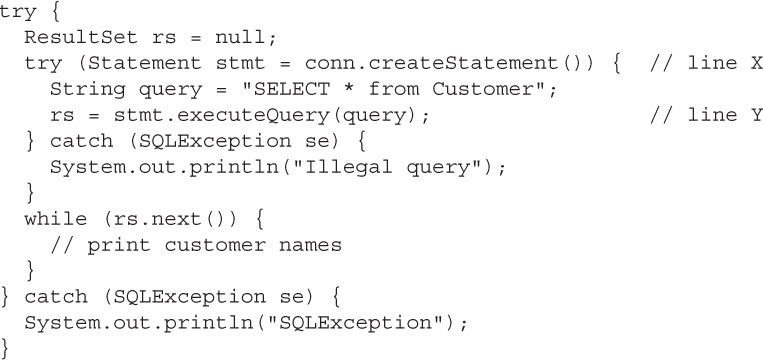

Probably one of the most used SQL queries is SELECT * FROM <Table name>, which is used to print out or see all of the records in a table. Assume that we have a Java DB (Derby) database populated with data from Bob’s Books. To query the database and return all of the Customers in the database, we would write something like the example shown next.

Note that to make the code listing a little shorter, going forward, we will use out.println instead of System.out.println. Just assume that means that we have included a static import statement, like the one at the top of this example:

Again, we’ll dive into all of the parts of this example in greater detail, but here is what is happening:

Get connection We are creating a

Get connection We are creating a Connection object instance using the information we need to access Bob’s Books Database (stored on a Java DB Relational database, BookSellerDB, and accessed via the credentials “bookguy” with a password of “$3lleR”).

Create statement We are using the

Create statement We are using the Connection to create a Statement object. The Statement object handles passing Strings to the database as queries for the database to execute.

Execute query We are executing the query string on the database and returning a

Execute query We are executing the query string on the database and returning a ResultSet object.

Process results We are iterating through the result set rows—each call to

Process results We are iterating through the result set rows—each call to next() moves us to the next row of results.

Print columns We are getting the values of the columns in the current result set row and printing them to standard out.

Print columns We are getting the values of the columns in the current result set row and printing them to standard out.

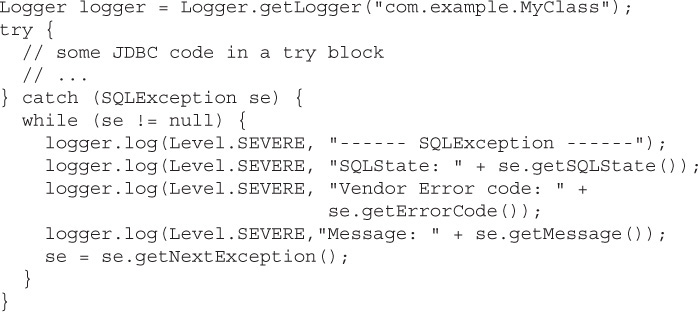

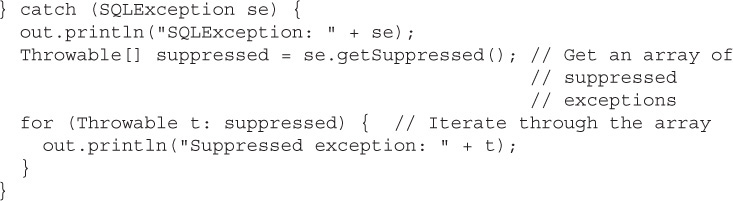

Catch

Catch SQLException All of the JDBC API method invocations throw SQLException. A SQLException can be thrown when a method is used improperly, or if the database is no longer responding. For example, a SQLException is thrown if the JDBC URL, username, or password is invalid. Or we attempted to query a table that does not exist. Or the database is no longer reachable because the network went down or the database went offline. We will look at SQLException in greater detail later in the chapter.

The output of the previous code will look something like this:

We’ll take a detailed look at the Statement and ResultSet interfaces and methods in the next two sections.

Once we have successfully connected to a database, the fun can really start. From a Connection object, we can create an instance of a Statement object (or, to be precise, using the Connection instance we received from the DriverManager, we can get an instance of an object that implements the Statement interface). For example:

The primary purpose of a Statement is to execute a SQL statement using a method and return some type of result. There are several forms of Statement methods: those that return a result set, and those that return an integer status. The most commonly used Statement method performs a SQL query that returns some data, like the SELECT call we used earlier to fetch all the Customer table rows.

To start, let’s look at the base Statement, which is used to execute a static SQL query and return a result. You’ll recall that we get a Statement from a Connection and then use the Statement object to execute a SQL statement, like a query on the database. For example:

Because not all SQL statements return results, the Statement object provides several different methods to execute SQL commands. Some SQL commands do not return a result set, but instead return an integer status. For example, SQL INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE commands, or any of the SQL Data Definition Language (DDL) statements, like CREATE TABLE, return either the number of rows affected by the query or 0.

Let’s look at each of the execute methods in detail.

public ResultSet executeQuery(String sql) throws SQLException This is the most commonly executed Statement method. This method is used when we know that we want to return results—we are querying the database for one or more rows of data. For example:

Assuming there is data in the Customer table, this statement should return all of the rows from the Customer table into a ResultSet object—we’ll look at ResultSet in the next section. Notice that the method declaration includes “throws SQLException.” This means that this method must be called in a try-catch block, or must be called in a method that also throws SQLException. Again, one reason that these methods all throw SQLException is that a connection to the database is likely to a database on a network. As with all things on the network, availability is not guaranteed, so one possible reason for SQLException is the lack of availability of the database itself.

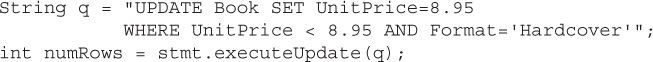

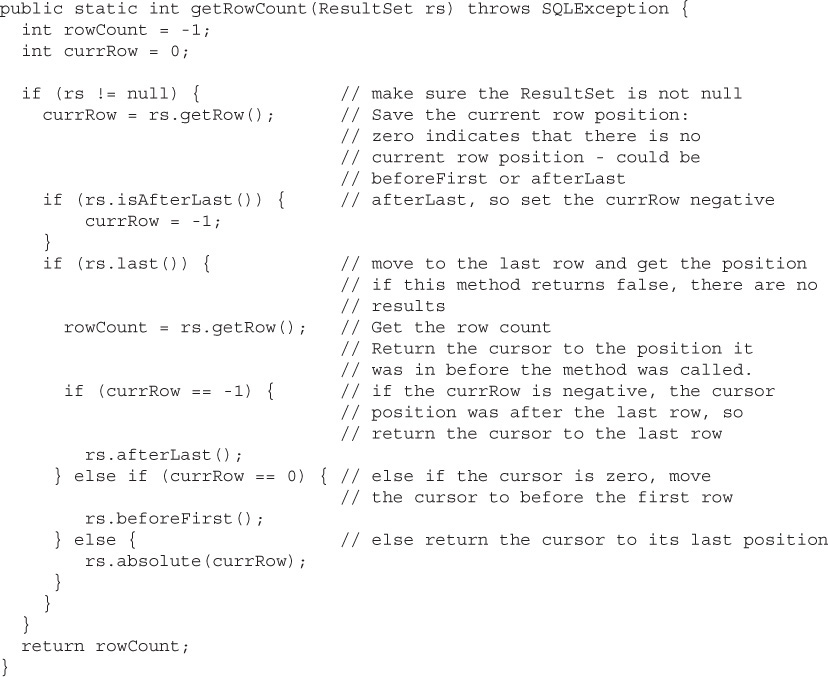

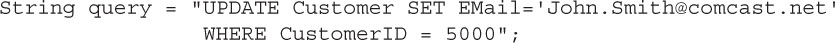

public int executeUpdate(String sql) throws SQLException This method is used for a SQL operation that affects one or more rows and does not return results—for example, SQL INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE, and DDL queries. These statements do not return results, but do return a count of the number of rows affected by the SQL query. For example, here is an example method invocation where we want to update the Book table, increasing the price of every book that is currently priced less than 8.95 and is a hardcover book:

When this query executes, we are expecting some number of rows will be affected. The integer that returns is the number of rows that were updated.

Note that this Statement method can also be used to execute SQL queries that do not return a row count, such as CREATE TABLE or DROP TABLE and other DDL queries. For DDL queries, the return value is 0.

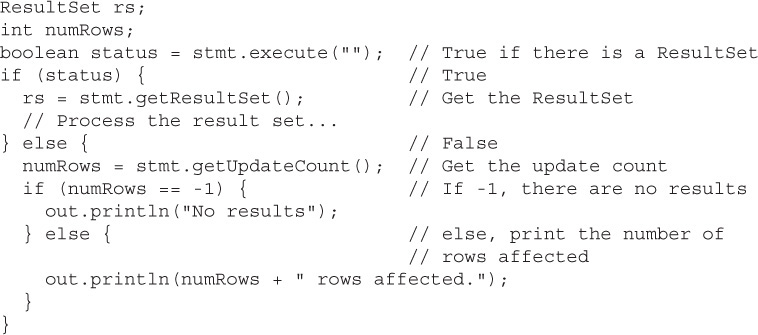

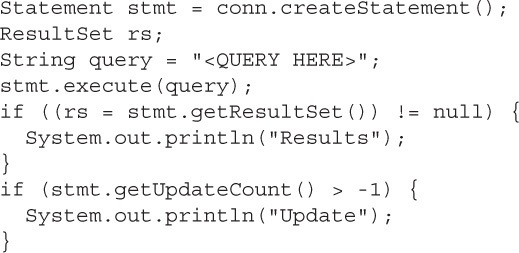

public boolean execute(String sql) throws SQLException This method is used when you are not sure what the result will be—perhaps the query will return a result set, and perhaps not. This method can be used to execute a query whose type may not be known until runtime—for example, one constructed in code. The return value is true if the query resulted in a result set and false if the query resulted in an update count or no results.

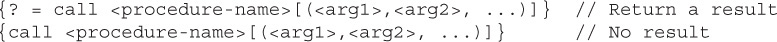

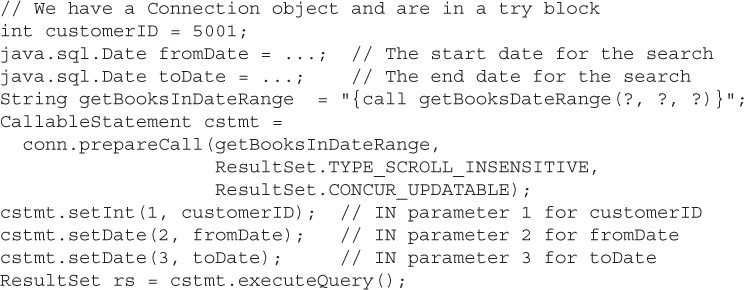

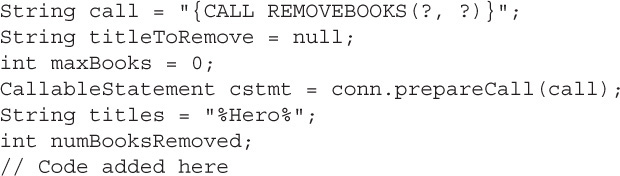

However, more often, this method is used when invoking a stored procedure (using the CallableStatement, which we’ll talk about later in the chapter). A stored procedure can return a single result set or row count, or multiple result sets and row counts, so this method was designed to handle what happens when a single database invocation produces more than one result set or row count.

You might also use this method if you wrote an application to test queries—something that reads a String from the command line and then runs that String against the database as a query. For example:

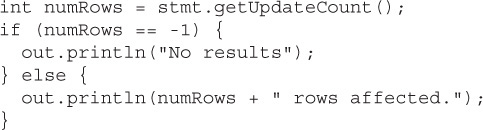

Because this statement may return a result set or may simply return an integer row count, there are two additional statement commands you can use to get the results or the count based on whether the execute method returned true (there is a result set) or false (there is an update count or there was no result). The getResultSet() is used to retrieve results when the execute method returns true, and the getUpdateCount() is used to retrieve the count when the execute method returns false. Let’s look at these methods next.

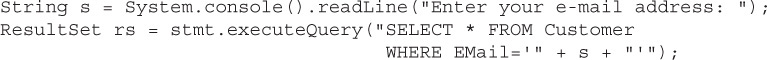

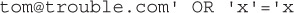

It is generally a very bad idea to allow a user to enter a query string directly in an input field, or allow a user to pass a string to construct a query directly. The reason is that if a user can construct a query or even include a freeform string into a query, they can use the query to return more data than you intended or to alter the database table permissions.

For example, assume that we have a query where the user enters their e-mail address and the string the user enters is inserted directly to the query:

The user of this code could enter a string like this:

The resulting query executed by the database becomes:

Because the OR statement will always return true, the result is that the query will return ALL of the customer rows, effectively the same as the query:

And now this user of your code has a list of the e-mail addresses of every customer in the database.

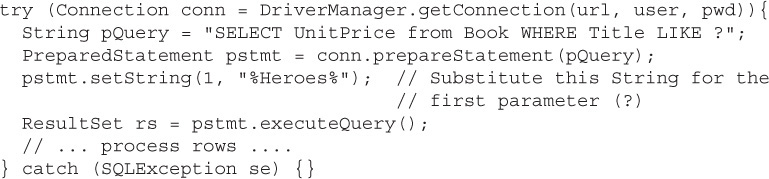

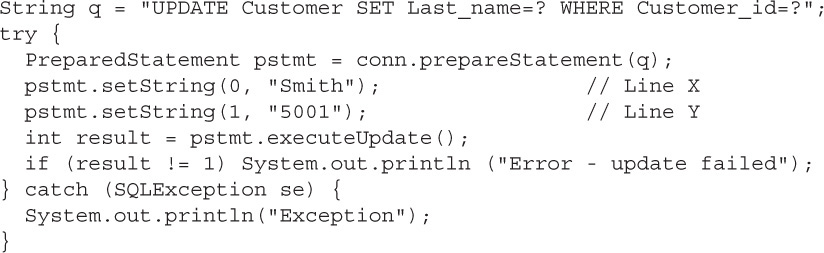

This type of attack is called a SQL injection attack. It is easy to prevent by carefully sanitizing any string input used in a query to the database and/or by using one of the other Statement types, PreparedStatement and CallableStatement. Despite how easy it is to prevent, it happens frequently, even to large, experienced companies like Yahoo!.

public ResultSet getResultSet() throws SQLException If the boolean value from the execute() method returns true, then there is a result set. To get the result set, as shown earlier, call the getResultSet() method on the Statement object. Then you can process the ResultSet object (which we will cover in the next section). This method is basically foolproof—if, in fact, there are no results, the method will return a null.

public int getUpdateCount() throws SQLException If the boolean value from the execute() method returns false, then there is a row count, and this method will return the number of rows affected. A return value of –1 indicates that there are no results.

Table 15-6 summarizes the Statement methods we just covered.

TABLE 15-6 Important Statement Methods

When a query returns a result set, an instance of a class that implements the ResultSet interface is returned. The ResultSet object represents the results of the query—all of the data in each row on a per-column basis. Again, as a reminder, how data in a ResultSet are stored is entirely up to the JDBC driver vendor. It is possible that the JDBC driver caches the entire set of results in memory all at once, or that it uses internal buffers and gets only a few rows at a time. From your point of view as the user of the data, it really doesn’t matter much. Using the methods defined in the ResultSet interface, you can read and manipulate the data, and that’s all that matters.

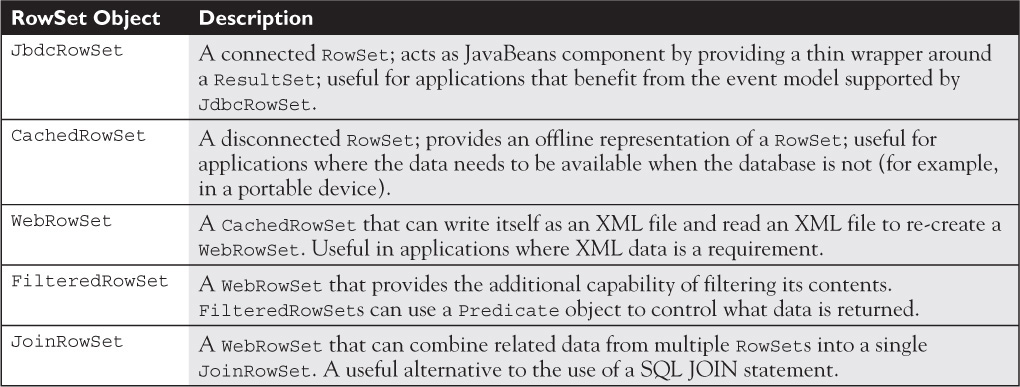

One important thing to keep in mind is that a ResultSet is a copy of the data from the database from the instance in time when the query was executed. Unless you are the only person using the database, you need to always assume that the underlying database table or tables that the ResultSet came from could be changed by some other user or application.

Because ResultSet is such a comprehensive part of the JDBC API, we are going to tackle it in sections. Table 15-7 summarizes each section so you can reference these later.

TABLE 15-7 ResultSet Sections

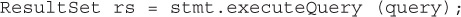

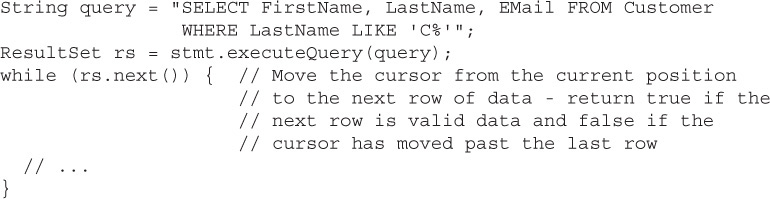

The best way to think of a ResultSet object is visually. Assume that in our BookSellerDB database we have several customers whose last name begins with the letter “C.” We could create a query to return those rows “like” this:

The SQL operator LIKE treats the string that follows as a pattern to match, where the % indicates a wildcard. So, LastName LIKE ‘C%’ means “any LastName with a C, followed by any other character(s).”

When we execute this query using the executeQuery() method, the ResultSet returned will contain the FirstName, LastName, and EMail columns where the customer’s LastName starts with the capital letter “C”:

The ResultSet object returned contains the data from the query as shown in Figure 15-4.

FIGURE 15-4 A ResultSet after the executeQuery

Note in Figure 15-4 that the ResultSet object maintains a cursor, or a pointer, to the current row of the results. When the ResultSet object is first returned from the query, the cursor is not yet pointing to a row of results—the cursor is pointing above the first row. In order to get the results of the table, you must always call the next() method on the ResultSet object to move the cursor forward to the first row of data. By default, a ResultSet object is read-only (the data in the rows cannot be updated), and you can only move the cursor forward. We’ll look at how to change this behavior a little later on.

So the first method you will need to know for ResultSet is the next() method.

public boolean next() The next() method moves the cursor forward one row and returns true if the cursor now points to a row of data in the ResultSet. If the cursor points beyond the last row of data as a result of the next()method (or if the ResultSet contains no rows), the return value is false.

So in order to read the three rows of data in the table shown in Figure 15-4, we need to call the next() method, read the row of data, and then call next()again twice more. When the next()method is invoked the fourth time, the method will return false. The easiest way to read all of the rows from first to last is in a while loop:

Moving the cursor forward through the ResultSet is just the start of reading data from the results of the query. Let’s look at the two ways to get the data from each row in a result set.

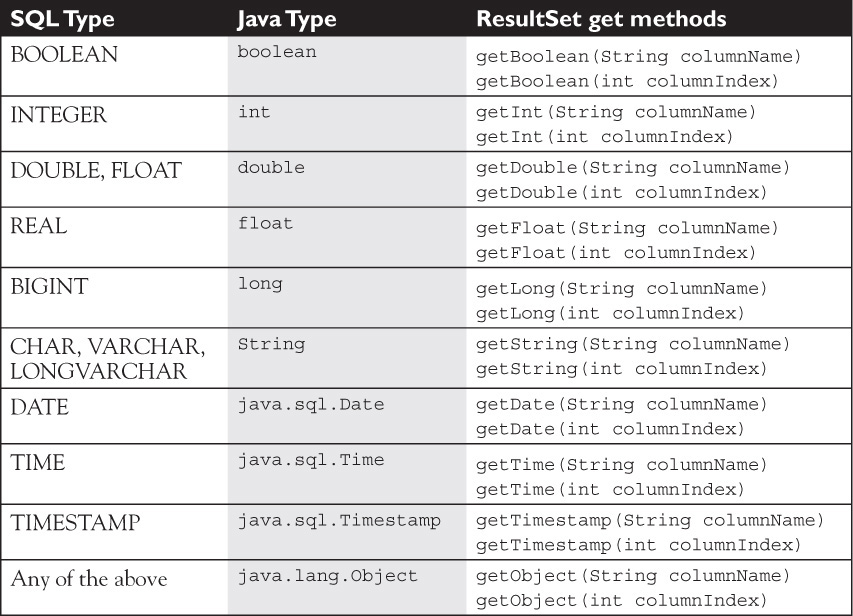

When a ResultSet is returned, and you have dutifully called next() to move the cursor to the first actual row of data, you can now read the data in each column of the current row. As illustrated in Figure 15-4, a result set from a database query is like a table or a spreadsheet. Each row contains (typically) one or more columns, and the data in each column is one of the SQL data types. In order to bring the data from each column into your Java application, you must use a ResultSet method to retrieve each of the SQL column values into an appropriate Java type. So SQL INTEGER, for example, can be read as a Java int primitive, SQL VARCHAR can be read as a Java String, SQL DATE can be read as a java.sql.Date object, and so on. ResultSet defines several other types as well, but whether or not the database or the driver supports all of the types defined by the specification depends on the database vendor. For the exam, we recommend you focus on the most common SQL data types and the ResultSet methods shown in Table 15-7.

SQL has been around for a long time. The first formalized, American National Standards Institute (ANSI)–approved version was adopted in 1986 (SQL-86). The next major revision was in 1992, SQL-92, which is widely considered the “base” release for every database. SQL-92 defined a number of new data types, including DATE, TIME, TIMESTAMP, BIT, and VARCHAR strings. SQL-92 has multiple levels; each level adds a bit more functionality to the previous level. JDBC drivers recognize three ANSI SQL-92 levels: Entry, Intermediate, and Full.

SQL-1999, also known as SQL-3, added LARGE OBJECT types, including BINARY LARGE OBJECT (BLOB) and CHARACTER LARGE OBJECT (CLOB). SQL-1999 also introduced the BOOLEAN type and a composite type, ARRAY and ROW, to store collections directly into the database. In addition, SQL-1999 added a number of features to SQL, including triggers, regular expressions, and procedural and flow control.

SQL-2003 introduced XML to the database, and importantly, added columns with auto-generated values, including columns that support identity, like the primary key and foreign key columns. Believe or not, other standards have been proposed, including SQL-2006, SQL-2008, and SQL-2011.

The reason this matters is because the JDBC specification has attempted to be consistent with features from the most widely adopted specification at the time. Thus, JDBC 3.0 supports SQL-92 and a part of the SQL-1999 specification, and JDBC 4.0 supports parts of the SQL-2003 specification. In this chapter, we’ll try to stick to the most widely used SQL-92 features and the most commonly supported SQL-1999 features that JDBC also supports.

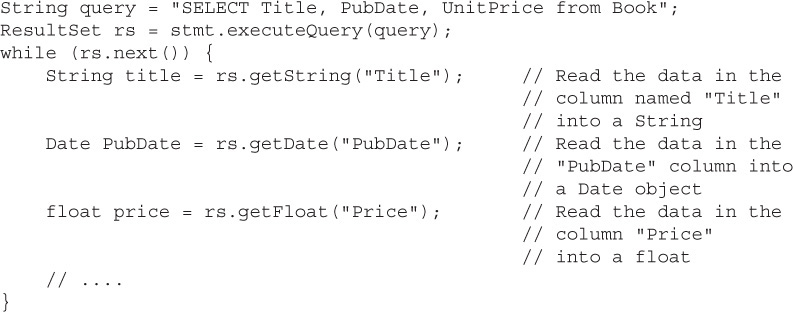

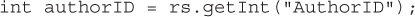

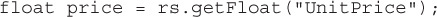

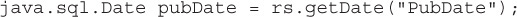

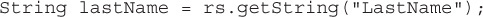

One way to read the column data is by using the names of the columns themselves as string values. For example, using the column names from Bob’s Book table (Table 15-4), in these ResultSet methods, the String name of the column from the Book table is passed to the method to read the column data type:

Note that although here the column names were retrieved from the ResultSet row in the order they were requested in the SQL query, they could have been processed in any order.

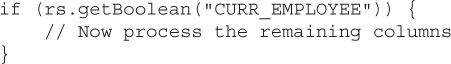

ResultSet also provides an overloaded method that takes an integer index value for each of the SQL types. This value is the integer position of the column in the result set, numbered from 1 to the number of columns returned. So we could write the same statements earlier like this:

Using the positional methods shown earlier, the order of the column in the ResultSet does matter. In our query, Title is in position 1, PubDate is in position 2, and Price is in position 3.

What the database stores as a type, the SQL type, and what JDBC returns as a type are often two different things. It is important to understand that the JDBC specification provides a set of standard mappings—the best match between what the database provides as a type and the Java type a programmer should use with that type. Rather than repeating what is in the specification, we encourage you to look at Appendix B of the JDBC (JSR-221) specification.

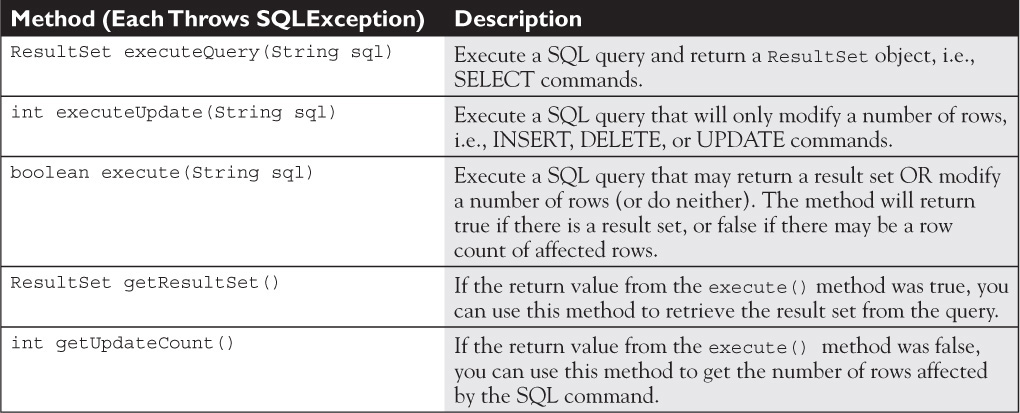

The most commonly used ResultSet get methods are listed next. Let’s look at these methods in detail.

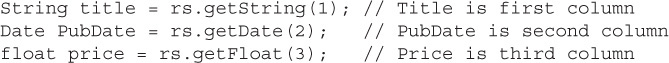

public boolean getBoolean(String columnLabel) This method retrieves the value of the named column in the ResultSet as a Java boolean. Boolean values are rarely returned in SQL queries, and some databases may not support a SQL BOOLEAN type, so check with your database vendor. In this contrived example here, we are returning employment status:

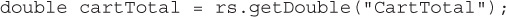

public double getDouble(String columnLabel) This method retrieves the value of the column as a Java double. This method is recommended for returning the value stored in the database as SQL DOUBLE and SQL FLOAT types.

public int getInt(String columnLabel) This method retrieves the value of the column as a Java int. Integers are often a good choice for primary keys. This method is recommended for returning values stored in the database as SQL INTEGER types.

public float getFloat(String columnLabel) This method retrieves the value of the column as a Java float. It is recommended for SQL REAL types.

public long getLong(String columnLabel) This method retrieves the value of the column as a Java long. It is recommended for SQL BIGINT types.

public java.sql.Date getDate(String columnLabel) This method retrieves the value of the column as a Java Date object. Note that java.sql.Date extends java.util.Date. The most interesting difference between the two is that the toString() method of java.sql.Date returns a date string in the form: “yyyy mm dd.” This method is recommended for SQL DATE types.

public java.lang.String getString(String columnLabel) This method retrieves the value of the column as a Java String object. It is good for reading SQL columns with CHAR, VARCHAR, and LONGVARCHAR types.

public java.sql.Time getTime(String columnLabel) This method retrieves the value of the column as a Java Time object. Like java.sql.Date, this class extends java.util.Date, and its toString() method returns a time string in the form: “hh:mm:ss.” TIME is the SQL type that this method is designed to read.

public java.sql.Timestamp getTimestamp(String columnLabel) This method retrieves the value of the column as a Timestamp object. Its toString() method formats the result in the form: yyyy-mm-dd hh:mm:ss.fffffffff, where ffffffffff is nanoseconds. This method is recommended for reading SQL TIMESTAMP types.

public java.lang.Object getObject(String columnLabel) This method retrieves the value of the column as a Java Object. It can be used as a general-purpose method for reading data in a column. This method works by reading the value returned as the appropriate Java wrapper class for the type and returning that as a Java Object object. So, for example, reading an integer (SQL INTEGER type) using this method returns an object that is a java.lang.Integer type. We can use instanceof to check for an Integer and get the int value:

Table 15-8 lists the most commonly used methods to retrieve specific data from a ResultSet. For the complete and exhaustive set of ResultSet get methods, see the Java documentation for java.sql.ResultSet.

TABLE 15-8 SQL Types and JDBC Types

When you write a query using a string, as we have in the examples so far, you know the name and type of the columns returned. However, what happens when you want to allow your users to dynamically construct the query? You may not always know in advance how many columns are returned and the type and name of the columns returned.

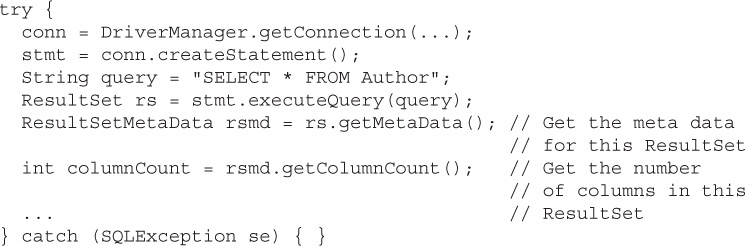

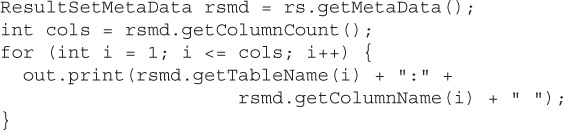

Fortunately, the ResultSetMetaData class was designed to provide just that information. Using ResultSetMetaData, you can get important information about the results returned from the query, including the number of columns, the table name, the column name, and the column class name—the Java class that is used to represent this column when the column is returned as an Object. Here is a simple example, and then we’ll look at these methods in more detail:

Running this code using the BookSeller database (Bob’s Books) produces the following output:

ResultSetMetaData is often used to generate reports, so here are the most commonly used methods. For more information and more methods, check out the JavaDocs.

public int getColumnCount() throws SQLException This method is probably the most used ResultSetMetaData method. It returns the integer count of the number of columns returned by the query. With this method, you can iterate through the columns to get information about each column.

The value of columnCount for the Author table is 3. We can use this value to iterate through the columns using the methods illustrated next.

public String getColumnName(int column) throws SQLException This method returns the String name of this column. Using the columnCount, we can create an output of the data from the database in a report-like format. For example:

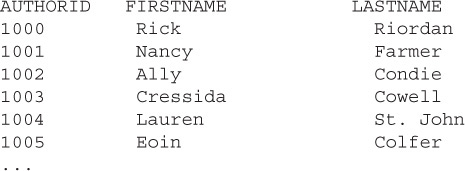

This example is somewhat rudimentary, as we probably need to do some better formatting on the data, but it will produce a table of output:

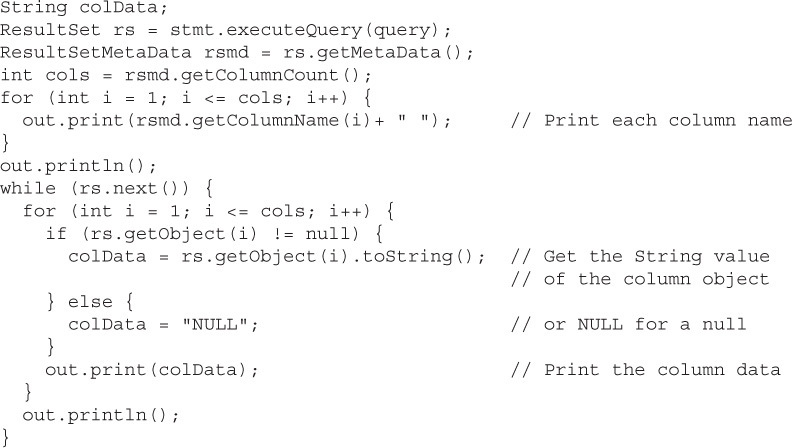

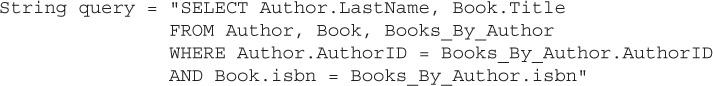

public String getTableName(int column) throws SQLException The method returns the String name of the table that this column belongs to. This method is useful when the query is a join of two or more tables and we need to know which table a column came from. For example, suppose that we want to get a list of books by author’s last name:

With a query like this, we might want to know which table the column data came from:

This code will print the name of the table, a colon, and the column name. The output might look something like this:

public int getColumnDisplaySize(int column) throws SQLException This method returns an integer of the size of the column. This information is useful for determining the maximum number of characters a column can hold (if it is a VARCHAR type) and the spacing that is required between columns for a report.

To make a prettier report than the one in the getColumnName method earlier, for example, we could use the display size to pad the column name and data with spaces. What we want is a table with spaces between the columns and headings that looks something like this when we query the Author table:

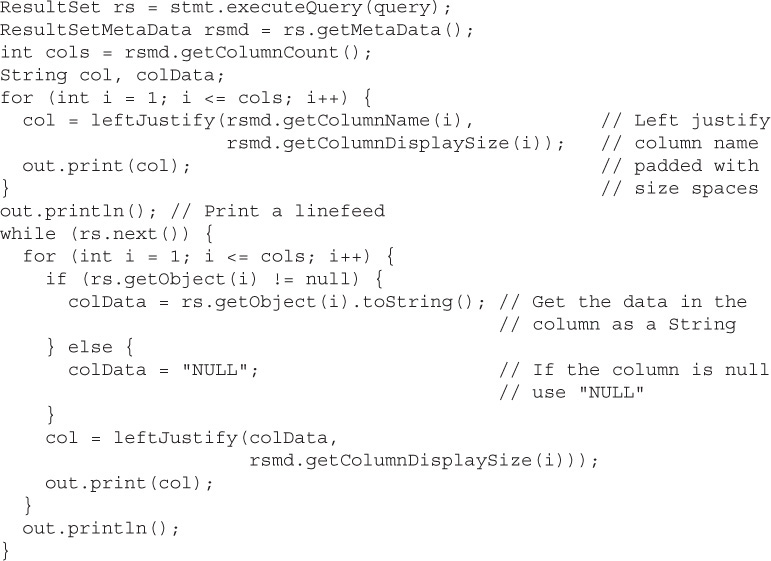

Using the methods we have discussed so far, here is code that produces a pretty report from a query:

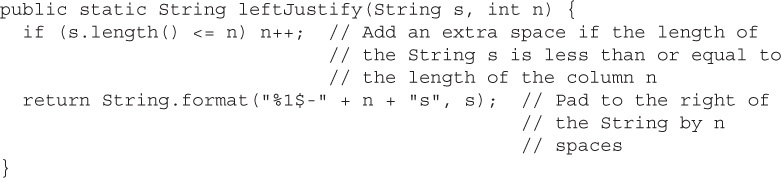

A couple of things to note about the example code: first, the leftJustify method, which takes a string to print left-justified and an integer for the total number of characters in the string. The difference between the actual string length and the integer value will be filled with spaces. This method uses the String format() method and the “-” (dash) flag to return a String that is left-justified with spaces. The %1$ part indicates the flag should be applied to the first argument. What we are building is a format string dynamically. If the column display size is 20, the format string will be %1$-20s, which says “print the argument passed (the first argument) on the left with a width of 20 and use a string conversion.”

Note that if the length of the string passed in and the integer field length (n) are the same, we add one space to the length to make it look pretty:

Second, databases can store NULL values. If the value of a column is NULL, the object returned in the rs.getObject() method is a Java null. So we have to test for null to avoid getting a null pointer exception when we execute the toString() method.

Notice that we don’t have to use the next() method before reading the ResultSetMetaData—we can do that at any time after obtaining a valid result set. Running this code and passing it a query like “SELECT * FROM Author” returns a neatly printed set of authors:

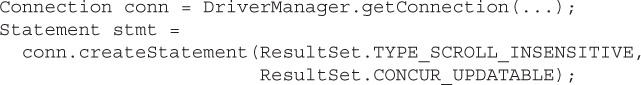

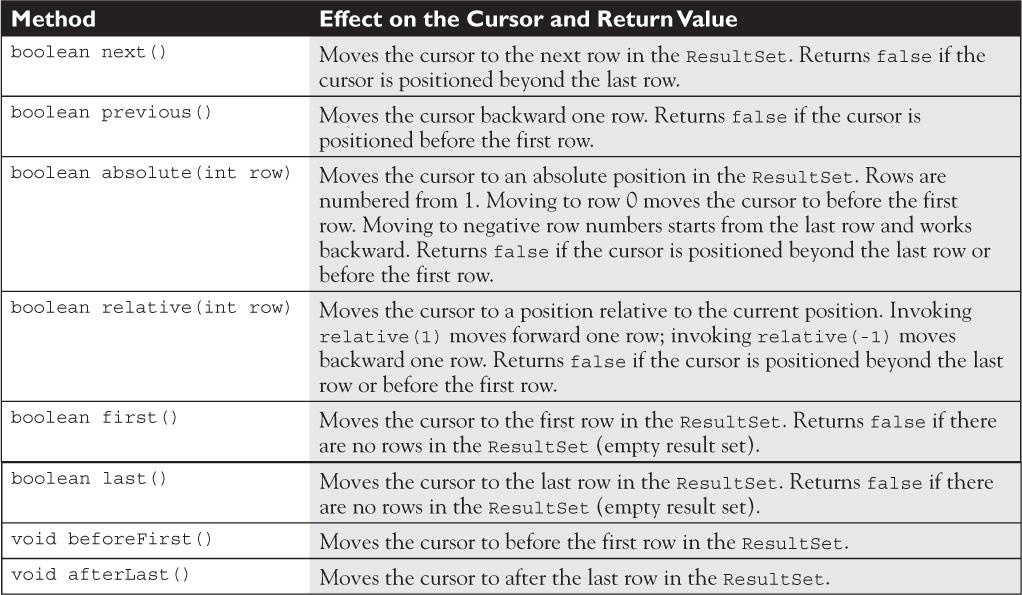

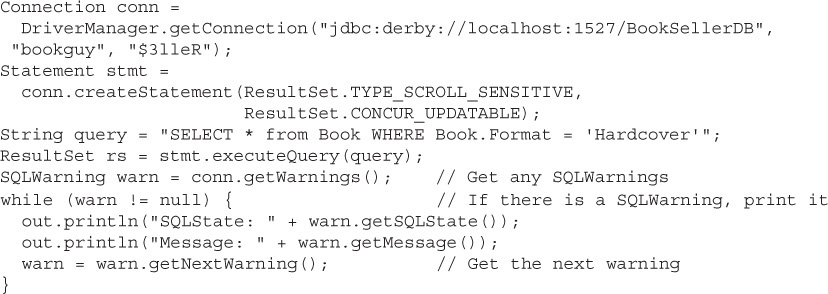

So far, for all the result sets we looked at, we simply moved the cursor forward by calling next(). The default characteristics of a Statement are cursors that only move forward and result sets that do not support changes. The ResultSet interface actually defines these characteristics as static int variables: TYPE_FORWARD_ONLY and CONCUR_READ_ONLY. However, the JDBC specification defines additional static int types (shown next) that allow a developer to move the cursor forward, backward, and to a specific position in the result set. In addition, the result set can be modified while open and the changes written to the database. Note that support for cursor movement and updatable result sets is not a requirement on a driver, but most drivers provide this capability. In order to create a result set that uses positionable cursors and/or supports updates, you must create a Statement with the appropriate scroll type and concurrency setting, and then use that Statement to create the ResultSet object.

The ability to move the cursor to a particular position is the key to being able to determine how many rows are returned from a result set—something we will look at shortly. The ability to modify an open result set may seem odd, particularly if you are a seasoned database developer. After all, isn’t that what a SQL UPDATE command is for?

Consider a situation where you want to perform a series of calculations using the data from the result set rows, then write a change to each row based on some criteria, and finally write the data back to the database. For example, imagine a database table that contains customer data, including the date they joined as a customer, their purchase history, and the total number of orders in the last two months. After reading this data into a result set, you could iterate over each customer record and modify it based on business rules: set their minimum discount higher if they have been a customer for more than a year with at least one purchase per year, or set their preferred credit status if they have been purchasing more than $100 per month. With an updatable result set, you can modify several customer rows, each in a different way, and commit the rows to the database without having to write a complex SQL query or a set of SQL queries—you simply commit the updates on the open result set.

Let’s look at how to modify a result set in more detail. There are three ResultSet cursor types:

TYPE_FORWARD_ONLY The default value for a

TYPE_FORWARD_ONLY The default value for a ResultSet—the cursor moves forward only through a set of results.

TYPE_SCROLL_INSENSITIVE A cursor position can be moved in the result forward or backward, or positioned to a particular cursor location. Any changes made to the underlying data—the database itself—are not reflected in the result set. In other words, the result set does not have to “keep state” with the database. This type is generally supported by databases.

TYPE_SCROLL_INSENSITIVE A cursor position can be moved in the result forward or backward, or positioned to a particular cursor location. Any changes made to the underlying data—the database itself—are not reflected in the result set. In other words, the result set does not have to “keep state” with the database. This type is generally supported by databases.

TYPE_SCROLL_SENSITIVE A cursor can be changed in the results forward or backward, or positioned to a particular cursor location. Any changes made to the underlying data are reflected in the open result set. As you can imagine, this is difficult to implement, and is therefore not implemented in a database or JDBC driver very often.

TYPE_SCROLL_SENSITIVE A cursor can be changed in the results forward or backward, or positioned to a particular cursor location. Any changes made to the underlying data are reflected in the open result set. As you can imagine, this is difficult to implement, and is therefore not implemented in a database or JDBC driver very often.

JDBC provides two options for data concurrency with a result set:

CONCUR_READ_ONLY This is the default value for result set concurrency. Any open result set is read-only and cannot be modified or changed.

CONCUR_READ_ONLY This is the default value for result set concurrency. Any open result set is read-only and cannot be modified or changed.

CONCUR_UPDATABLE A result set can be modified through the

CONCUR_UPDATABLE A result set can be modified through the ResultSet methods while the result set is open.

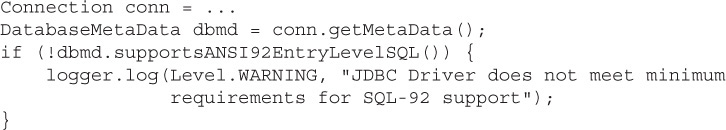

Because a database and JDBC driver are not required to support cursor movement and concurrent updates, the JDBC provides methods to query the database and driver using the DatabaseMetaData object to determine if your driver supports these capabilities. For example:

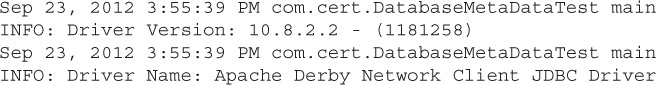

Running this code on the Java DB (Derby) database, these are the results:

In order to create a ResultSet with TYPE_SCROLL_INSENSITIVE and CONCUR_UPDATABLE, the Statement used to create the ResultSet must be created (from the Connection) with the cursor type and concurrency you want. You can determine what cursor type and concurrency the Statement was created with, but once created, you can’t change the cursor type or concurrency of an existing Statement object. Also, note that just because you set a cursor type or concurrency setting, that doesn’t mean you will get those settings. As you will see in the section on exceptions, the driver can determine that the database doesn’t support one or both of the settings you chose and it will throw a warning and (silently) revert to its default settings if they are not supported. You will see how to detect these JDBC warnings in the section on exceptions and warnings.

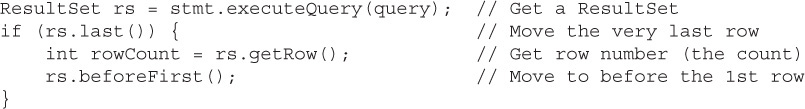

Besides being able to use a ResultSet object to update results, which we’ll look at next, being able to manipulate the cursor provides a side benefit—we can use the cursor to determine the number of rows returned in a query. Although it would seem like there ought to be a method in ResultSet or ResultSetMetaData to do this, this method does not exist.

In general, you should not need to know how many rows are returned, but during debugging, you may want to diagnose your queries with a stand-alone database and use cursor movement to read the number of rows returned.

Something like this would work:

Of course, you may also want to have a more sophisticated method that preserves the current cursor position and returns the cursor to that position, regardless of when the method was called. Before we look at that code, let’s look at the other cursor movement methods and test methods (besides next) in ResultSet. As a quick summary, Table 15-9 lists the methods you use to change the cursor position in a ResultSet.

TABLE 15-9 ResultSet Cursor Positioning Methods

Let’s look at each of these methods in more detail.

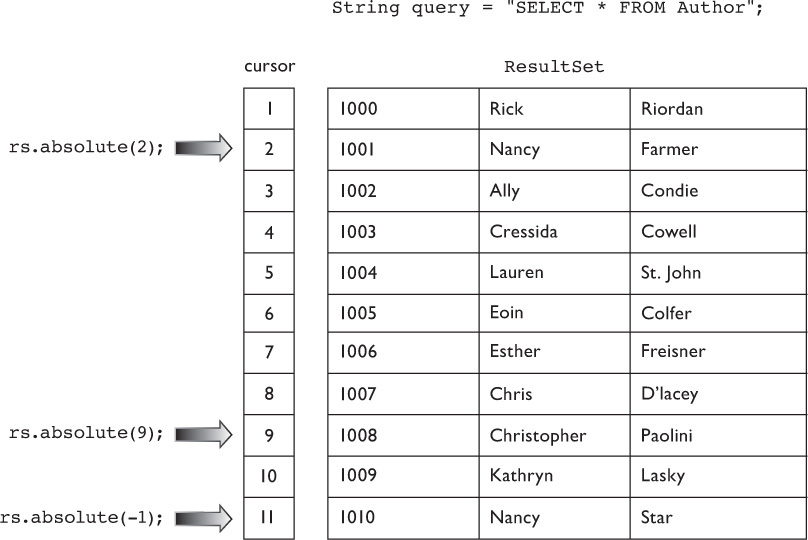

public boolean absolute(int row) throws SQLException This method positions the cursor to an absolute row number. The contrasting method is relative. Passing 0 as the row argument positions the cursor to before the first row. Passing a negative value, like -1, positions the cursor to the position after the last row minus one—in other words, the last row. If you attempt to position the cursor beyond the last row, say at position 22 in a 19-row result set, the cursor will be positioned beyond the last row, the implications of which we’ll discuss next. Figure 15-5 illustrates how invocations of absolute() position the cursor.

FIGURE 15-5 Absolute cursor positioning

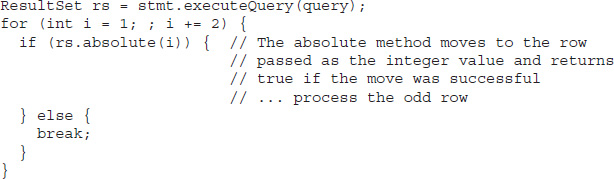

The absolute() method returns true if the cursor was successfully positioned within the ResultSet and false if the cursor ended up before the first or after the last row. For example, suppose that you wanted to process only every other row:

public int getRow() throws SQLException This method returns the current row position as a positive integer (1 for the first row, 2 for the second, and so on) or 0 if there is no current row—the cursor is either before the first row or after the last row. This is the only method of this set of cursor methods that is optionally supported for TYPE_FORWARD_ONLY ResultSets.

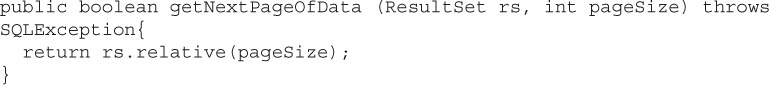

public boolean relative(int rows) throws SQLException The relative() method is the cousin to absolute. Get it, cousin? Okay, anyway, relative() will position the cursor either before or after the current position of the number of rows passed in to the method. So if the cursor is on row 15 of a 30-row ResultSet, calling relative(2) will position the cursor to row 17, and then calling relative(-5) positions the cursor to row 12. Figure 15-6 shows how the cursor is moved based on calls to absolute() and relative().

FIGURE 15-6 Relative cursor positioning (Circled numbers indicate order of invocation.)

Like absolute positioning, attempting to position the cursor beyond the last row or before the first row simply results in the cursor being after the last row or before the first row, respectively, and the method returns false. Also, calling relative with an argument of 0 does exactly what you might expect—the cursor remains where it is. Why would you use relative? Let’s assume that you are displaying a fairly long database table on a web page using an HTML table. You might want to allow your user to be able to page forward or backward relative to the currently selected row; maybe something like this:

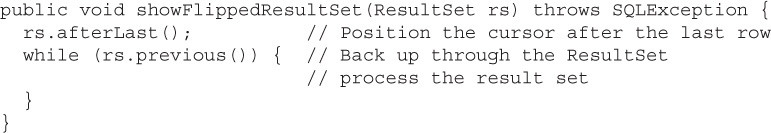

public boolean previous() throws SQLException The previous() method works exactly the same as the next() method, only it backs up through the ResultSet. Using this method with the afterLast() method described next, you can move through a ResultSet in reverse order (from last row to first).

public void afterLast() throws SQLException This method positions the cursor after the last row. Using this method and then the previous() method, you can iterate through a ResultSet in reverse. For example:

Just like next(), when previous() backs up all the way to before the first row, the method returns false.

public void beforeFirst() throws SQLException This method will return the cursor to the position it held when the ResultSet was first created and returned by a Statement object.

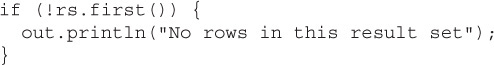

public boolean first() throws SQLException The first() method positions the cursor on the first row. It is the equivalent of calling absolute(1). This method returns true if the cursor was moved to a valid row, and false if the ResultSet has no rows.

public boolean last() throws SQLException The last() method positions the cursor on the last row. This method is the equivalent of calling absolute(-1). This method returns true if the cursor was moved to a valid row, and false if the ResultSet has no rows.

A couple of notes on the exceptions thrown by all of these methods:

A

A SQLException will be thrown by these methods if the type of the ResultSet is TYPE_FORWARD_ONLY, if the ResultSet is closed (we will look at how a result set is closed in an upcoming section), or if a database error occurs.

A

A SQLFeatureNotSupportedException will be thrown by these methods if the JDBC driver does not support the method. This exception is a subclass of SQLException.

Most of these methods have no effect if the

Most of these methods have no effect if the ResultSet has no rows—for example, a ResultSet returned by a query that returned no rows.

The following methods return a boolean to allow you to “test” the current cursor position without moving the cursor. Note that these are not on the exam, but are provided to you for completeness:

isBeforeFirst() True if the cursor is positioned before the first row

isAfterLast() True if the cursor is positioned after the last row

isFirst() True if the cursor is on the first row

isLast() True if the cursor is on the last row

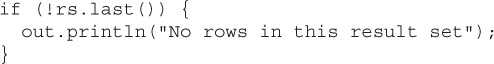

So now that we have looked at the cursor positioning methods, let’s revisit the code to calculate the row count. We will create a general-purpose method to allow the row count to be calculated at any time and at any current cursor position. Here is the code:

Looking through the code, you notice that we took special care to preserve the current position of the cursor in the ResultSet. We called getRow() to get the current position, and if the value returned was 0, the current position of the ResultSet could be either before the first row or after the last row, so we used the isAfterLast() method to determine where the cursor was. If the cursor was after the last row, then we stored a -1 in the currRow integer.

We then moved the cursor to the last position in the ResultSet, and if that move was successful, we get the current position and save it as the rowCount (the last row and, therefore, the count of rows in the ResultSet). Finally, we use the value of currRow to determine where to return the cursor. If the value of the cursor is -1, we need to position the cursor after the last row. Otherwise, we simply use absolute() to return the cursor to the appropriate position in the ResultSet.

While this may seem like several extra steps, we will look at why preserving the cursor can be important when we look at updating ResultSets next.

If you have casually used JDBC, or are new to JDBC, you may be surprised to know that a ResultSet object can do more than just provide the results of a query to your application. Besides just returning the results of a query, a ResultSet object may be used to modify the contents of a database table, including update existing rows, delete existing rows, and add new rows. Please note that this section and the subsections that follow are not on the exam, and are provided to give you some insight into the power of using an object to represent relational data.

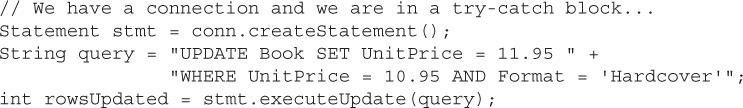

In a traditional SQL application, you might perform the following SQL queries to raise the price of all of the hardcover books in inventory that are currently 10.95 to 11.95 in price:

Hopefully by now you feel comfortable that you could create a Statement to perform this query using a SQL UPDATE:

But what if you wanted to do the updates on a book-by-book basis? You only want to increase the price of your best sellers, rather than every single book.

You would then have to get the values from the database using a SELECT, then store the values in an array indexed somehow—perhaps with the primary key—then construct the appropriate UPDATE command strings, and call executeUpdate() one row at a time. Another option is to update the ResultSet directly.

When you create a Statement with concurrency set to CONCUR_UPDATABLE, you can modify the data in a result set and then apply your changes back to the database without having to issue another query.

In addition to the getXXXX methods we looked at for ResultSet, methods that get column values as integers, Date objects, Strings, etc., there is an equivalent updateXXXX method for each type. And, just like the getXXXX methods, the updateXXXX methods can take either a String column name or an integer column index.

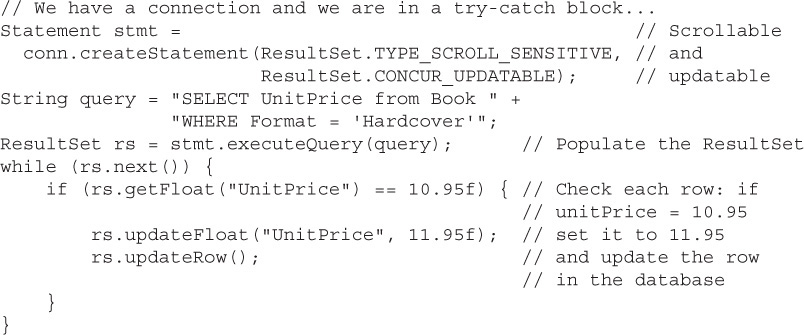

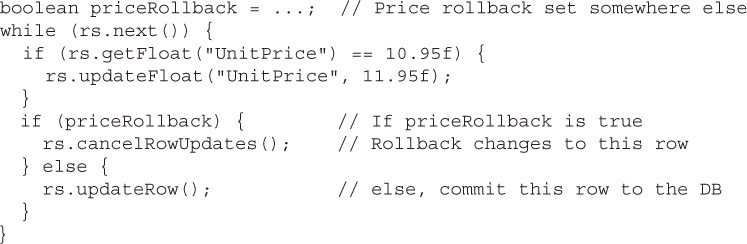

Let’s rewrite the previous update example using an updatable ResultSet:

Notice that after modifying the value of UnitPrice using the updateFloat() method, we called the method updateRow(). This method writes the current row to the database. This two-step approach ensures that all of the changes are made to the row before the row is written to the database. And, you can change your mind with a cancelRowUpdates() method call.

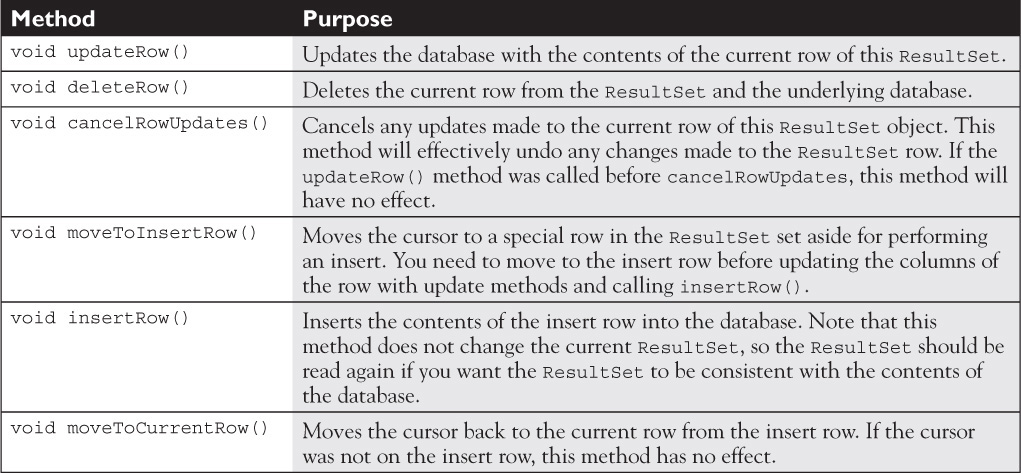

Table 15-10 summarizes methods that are commonly used with updatable ResultSets (whose concurrency type is set to CONCUR_UPDATABLE).

TABLE 15-10 Methods Used with Updatable ResultSets

Let’s look at the common methods used for altering database contents through the ResultSet in detail.

public void updateRow() throws SQLException This method updates the database with the contents of the current row of the ResultSet. There are a couple of caveats for this method. First, the ResultSet must be from a SQL SELECT statement on a single table—a SQL statement that includes a JOIN or a SQL statement with two tables cannot be updated. Second, the updateRow() method should be called before moving to the next row. Otherwise, the updates to the current row may be lost.

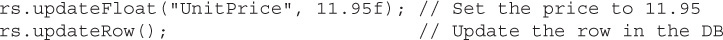

So the typical use for this method is to update the contents of a row using the appropriate updateXXXX() methods and then update the database with the contents of the row using the updateRow() method. For example, in this fragment, we are updating the UnitPrice of a row to $11.95:

public boolean rowUpdated() throws SQLException This method returns true if the current row was updated. Note that not all databases can detect updates. However, JDBC provides a method in DatabaseMetaData to determine if updates are detectable, DatabaseMetaData.updatesAreDetected(int type), where the type is one of the ResultSet types—TYPE_SCROLL_INSENSITIVE, for example. We will cover the DatabaseMetaData interface and its methods a little later in this section.

public void cancelRowUpdates() throws SQLException This method allows you to “back out” changes made to the row. This method is important, because the updateXXXX methods should not be called twice on the same column. In other words, if you set the value of UnitPrice to 11.95 in the previous example and then decided to switch the price back to 10.95, calling the updateFloat() method again can lead to unpredictable results. So the better approach is to call cancelRowUpdates() before changing the value of a column a second time.

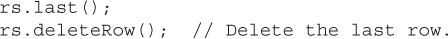

public void deleteRow() throws SQLException This method will remove the current row from the ResultSet and from the underlying database. The row in the database is removed (similar to the result of a DELETE statement).

What happens to the ResultSet after a deleteRow() method depends upon whether or not the ResultSet can detect deletions. This ability is dependent upon the JDBC driver. When a ResultSet can detect deletions, the deleted row is removed from the ResultSet. When the ResultSet cannot detect deletions, the columns of the ResultSet row that was deleted are made invalid by setting each column to null.

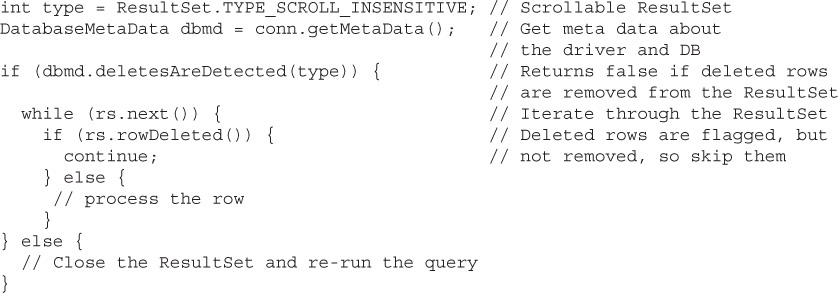

The DatabaseMetaData interface can be used to determine if the ResultSet can detect deletions:

In general, to maintain an up-to-date ResultSet after a deletion, the ResultSet should be re-created with a query.

Deleting the current row does not move the cursor—it remains on the current row—so if you deleted row 1, the cursor is still positioned at row 1. However, if the deleted row was the last row, then the cursor is positioned after the last row. Note that there is no undo for deleteRow(), at least, not by default. As you will see a little later, we can “undo” a delete if we are using transactions.

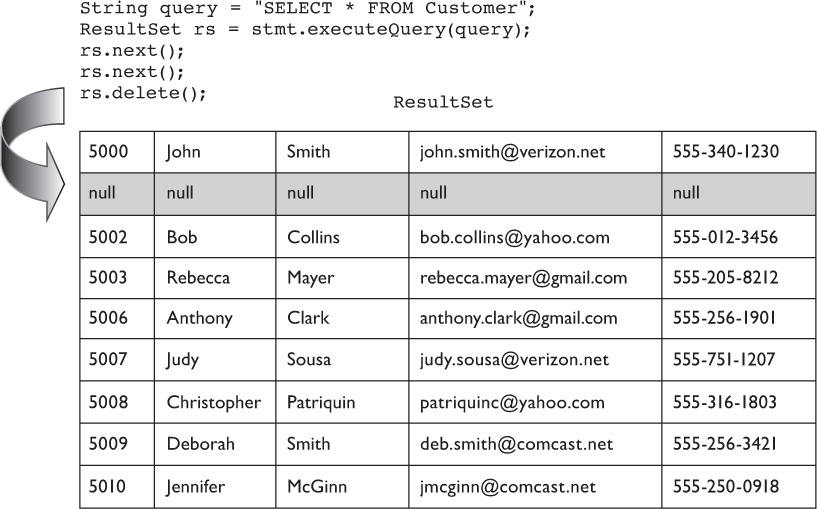

public boolean rowDeleted() throws SQLException As described earlier, when a ResultSet can detect deletes, the rowDeleted() method is used to indicate a row has been deleted, but remains as a part of the ResultSet object. For example, suppose that we deleted the second row of the Customer table. Printing the results (after the delete) to the console would look like Figure 15-7.

FIGURE 15-7 A ResultSet after delete() is called on the second row

So if you are working with a ResultSet that is being passed around between methods and shared across classes, you might use rowDeleted() to detect if the current row contains valid data.

Updating Columns Using Objects An interesting aspect of the getObject() and updateObject() methods is that they retrieve a column as a Java object. And, since every Java object can be turned into a String using the object’s toString() method, you can retrieve the value of any column in the database and print the value to the console as a String, as we saw in the section “Printing a Report.”

Going the other way, toward the database, you can also use Strings to update almost every column in a ResultSet. All of the most common SQL types—integer, float, double, long, and date—are wrapped by their representative Java object: Integer, Float, Double, Long, and java.sql.Date. Each of these objects has a method valueOf() that takes a String.

The updateObject() method takes two arguments: the first, a column name (String) or column index, and the second, an Object. We can pass a String as the Object type, and as long as the String meets the requirements of the valueOf() method for the column type, the String will be properly converted and stored in the database as the desired SQL type.

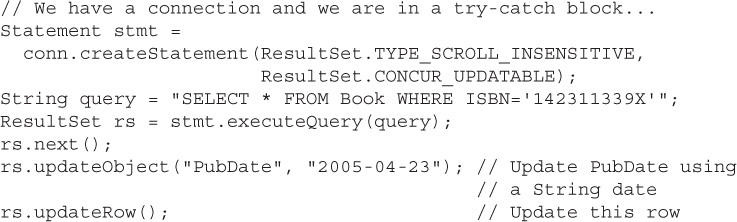

For example, suppose that we are going to update the publish date (PubDate) of one of our books:

The String we passed meets the requirements for java.sql.Date, “yyyy-[m]m-[d]d,” so the String is properly converted and stored in the database as the SQL Date value: 2005-04-23. Note this technique is limited to those SQL types that can be converted to and from a String, and if the String passed to the valueOf() method for the SQL type of the column is not properly formatted for the Java object, an IllegalArgumentException is thrown.

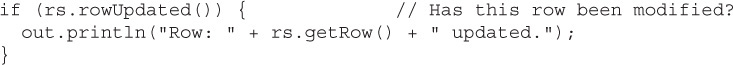

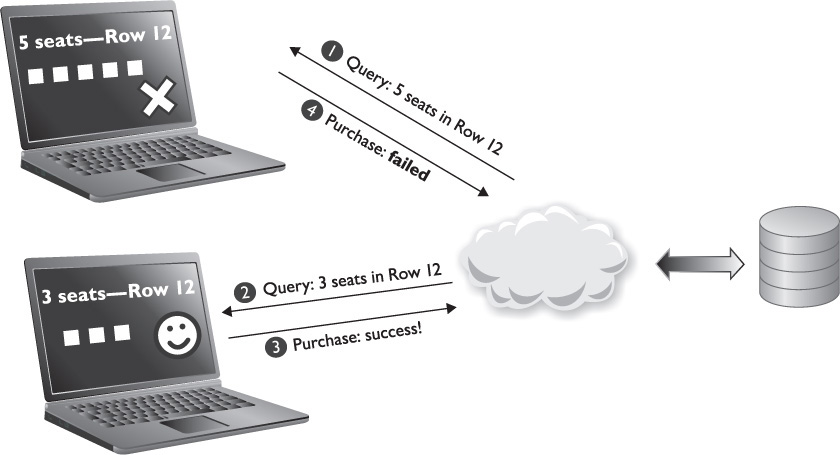

In the last section, we looked at modifying the existing column data in a ResultSet and removing existing rows. In our final section on ResultSets, we’ll look at how to create and insert a new row. First, you must have a valid ResultSet open, so typically, you have performed some query. ResultSet provides a special row, called the insert row, that you are actually modifying (updating) before performing the insert. Think of the insert row as a buffer where you can modify an empty row of your ResultSet with values.

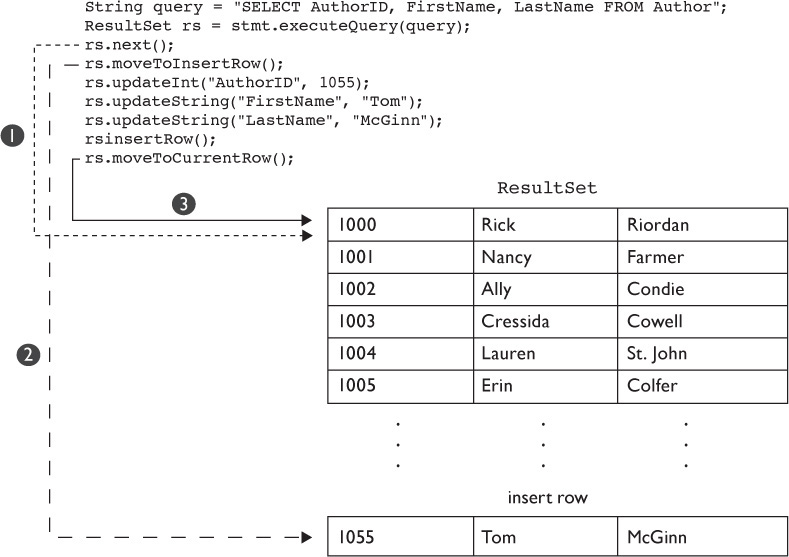

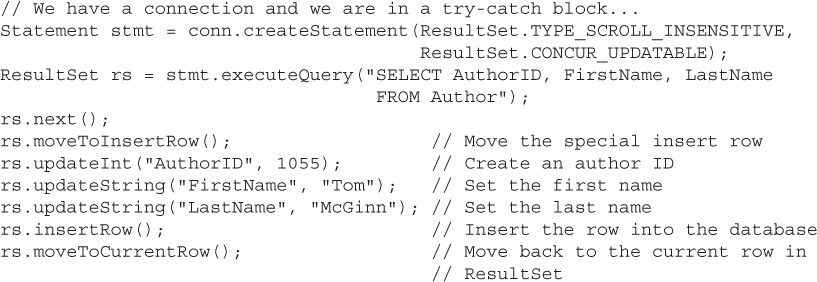

Inserting a row is a three-step process, as shown in Figure 15-8: First (1) move to the special insert row, then (2) update the values of the columns for the new row, and finally (3) perform the actual insert (write to the underlying database). The existing ResultSet is not changed—you must rerun your query to see the underlying changes in the database. However, you can insert as many rows as you like. Note that each of these methods throws a SQLException if the concurrency type of the result set is set to CONCUR_READ_ONLY. Let’s look at the methods before we look at example code.

FIGURE 15-8 The ResultSet insert row

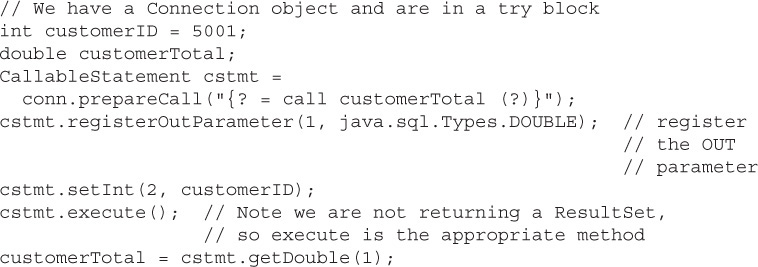

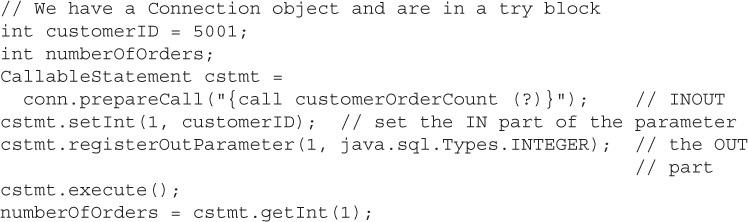

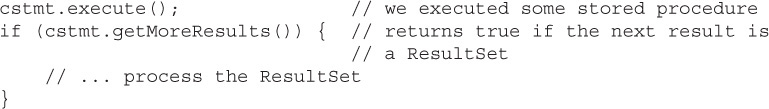

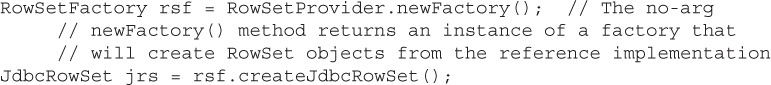

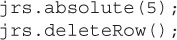

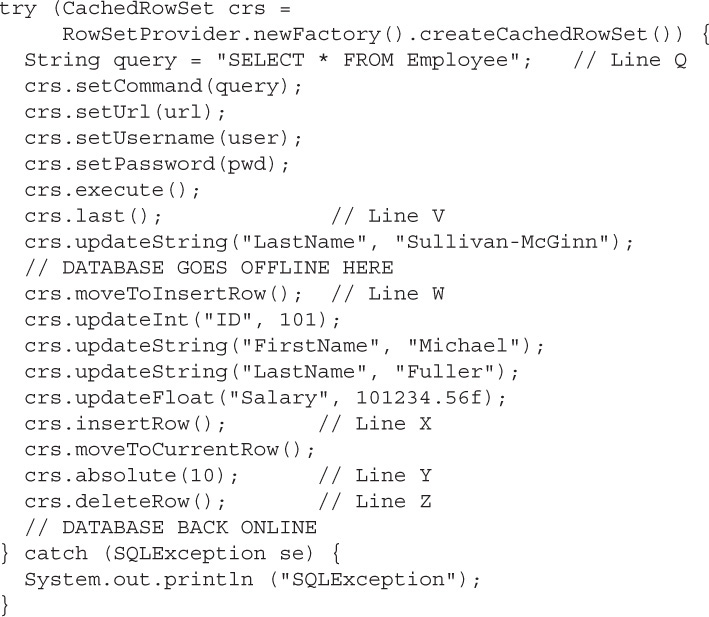

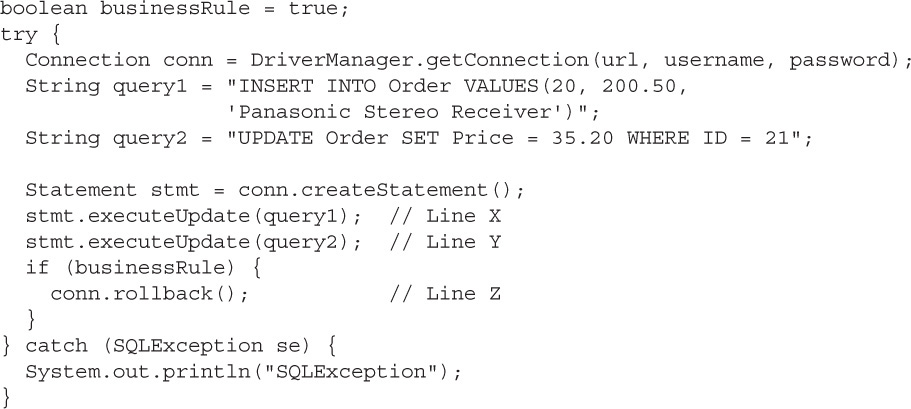

public void moveToInsertRow() throws SQLException This method moves the cursor to insert a row buffer. Wherever the cursor was when this method was called is remembered. After calling this method, the appropriate updater methods are called to update the values of the columns.