NATURAL BAIT AND ARTIFICIAL LURES

One of my most vivid fishing memories is of a Sunday afternoon in springtime when I was in grade school. After church and family dinner, I headed off to go fishing in a large pond on our neighbor’s farm. I’d trapped some minnows for bait. (Our family raised and sold minnows for extra income.) My plan was to use a long cane pole to bobber-fish for crappies.

However, as I eased up to the water’s edge, I spied a large bass finning lazily in the shallows below me. I crept backward, unwound the line from my pole, and baited my hook with the biggest minnow in the bucket. Then I eased back to the pond’s edge and lowered the minnow right in front of the bass’ nose.

Suddenly I had a tempest on my line! The bass inhaled the minnow and hooked itself in the process. The fish went wild, jumping and thrashing and splashing water and mud in all directions. I held on and was finally able to drag that fish out on the bank. That was enough action for one day! I headed straight home to show my catch. In less than a half-hour I was back with a five-pound largemouth and a memory to keep forever.

In this case, the big minnow did the trick. At other times it was worms, crawfish, and other live or artificial baits. Bait is a part of every fishing story. This is why beginners must learn about different baits, which work on which species, and how to use them. Simply put, if you’re not savvy about baits, you won’t catch many fish.

Most of North America’s waterways, no matter how large or small, offer good fishing for anglers who take the time to locate them and learn their secrets.

NATURAL AND ARTIFICIAL BAITS

There are two broad categories of baits: natural and artificial.

Natural baits are organic. They include minnows, worms, insects, crawfish, leeches, frogs, cut bait (fish pieces)—a wide variety of living or once-living critters.

Artificial baits include a vast range of lures. Some mimic natural bait. Others bear no resemblance to any natural food, yet they have some attraction that causes fish to bite. (Besides being hungry, fish strike artificial lures because they’re mad, greedy, curious, or impulsive.)

The list of categories of artificial baits includes topwaters, spinners, crankbaits, soft plastics, jigs, spoons, and flies. Further, these categories can be broken down into individual types of baits. For example, soft plastics include plastic worms, minnows, lizards, grubs, crawfish, tubes, eels, and more.

Natural baits are effective on most species of fish. Minnows, worms, grasshoppers, crawfish, leeches, and other “critters” offer real look, movement, and smell, and feeding fish bite them with little hesitation.

Many anglers find success using the specific live bait upon which their target fish are feeding. For instance, small shad, like the one shown here, are a favorite target of game- and panfish. Capture some alive, hook one on, and offer it where fish are feeding; chances are very good for a strike.

So, which should you use: natural bait or artificials? Anglers have faced this decision since the first lures were invented. (Before this, natural baits were the only choice.) Basically, this is a matter of personal preference, convenience, and bait capabilities. Each has certain advantages over the other.

Fish usually prefer natural bait over artificials. A bluegill will eat a real earthworm before it will eat a plastic one. If a live crawfish is retrieved next to an artificial crawfish, a bass will recognize and take the live one. These are examples of why more fish caught in North America are taken on natural bait. It’s hard to beat Mother Nature.

So why even bother with artificial baits? There are several reasons. First, many anglers enjoy the challenge of using artificials. Since fish are harder to catch on artificials, these anglers feel there’s more reward in fooling the fish with them. These people are fishing more for sport than for meat.

Second, artificial baits are more convenient. You don’t have to dig or trap them, and you don’t have to keep them alive and fresh. Most artificials can be kept in a tackle box indefinitely and fished with no advance preparation.

Third, artificial lures have certain capabilities and attractions that natural baits don’t have. While natural baits are normally used with a stationary or slow-moving presentation, artificials can be retrieved rapidly to cover a lot of water quickly. They sometimes cause inactive fish to strike out of impulse or anger as the bait runs by (the “catch-it-before-it-gets-away” syndrome). On the other hand, this same fish might ignore a minnow hanging under a bobber because it just doesn’t trigger its feeding instinct.

So, when deciding which to use, weigh the advantages of natural bait versus artificials as they relate to your particular fishing situation. Which is more important: making a good catch, or enjoying a sporty challenge? How difficult is it to get and keep natural bait? Which type bait is more likely to suit your fish’s mood and location and the technique you’ll use to try for it?

USING NATURAL BAIT

To use natural bait, you have to get it, keep it fresh, hook it on properly, and offer it with the right presentation. Following are guidelines for fishing with several popular natural baits.

Although you might be able to catch your own bait, in many cases it’s more practical to buy bait from a dealer who has it in stock. True, catching bait can be almost as much fun as catching fish, but I usually buy my bait to save as much time as possible for fooling the fish.

One other note: fish normally prefer fresh, active bait to old, lifeless bait. This is why I always keep fresh bait on my hook. If my minnow quits swimming, I replace it with a new one!

Worms are the most popular of all natural baits. They include large nightcrawlers and a variety of smaller earthworms (“wigglers”). Worms can be used to catch a variety of panfish and sportfish. They’re especially good for catfish, bullheads, bass, sunfish, walleyes, yellow perch, and trout.

Worms are easy to collect. You can dig for them in moist, rich soil in gardens or around barnyards, and find them under rotting leaves or logs. In warm weather nightcrawlers can be collected on a grassy lawn at night following a rain. Place freshly captured worms in a small container partially filled with loose crumbled dirt. If you put a top on the container, make sure it has holes so the worms can breathe.

Keep the worm can or box out of the sun or the worms might become overheated and die. Many anglers keep their worms in a cooler. Leftover worms will keep for several days in a refrigerator. If you’re not going fishing again for a week or so, just let them go in the yard and get some more when you need them.

There are several methods for using worms. With a stationary rig (bobber rig, bottom rig), gob one or more worms onto the hook, running the point through the middle of the worm’s body several times with the ends dangling free. When fishing for bluegills or yellow perch with a drop-shot rig, don’t put too much worm on the hook, since these fish have small mouths. But when fishing for catfish, bass, and other large fish, the more worms on the hook, the better because such fish like big mouthfuls.

If you’re fishing for walleyes or bass with a walking slip-sinker, drop-shot rig, or a bottom bouncer, hook a nightcrawler once through the head so the body can trail out behind. When drift fishing in a stream for trout, hook the worm through the middle of the body and allow the two ends to dangle and squirm enticingly in the current.

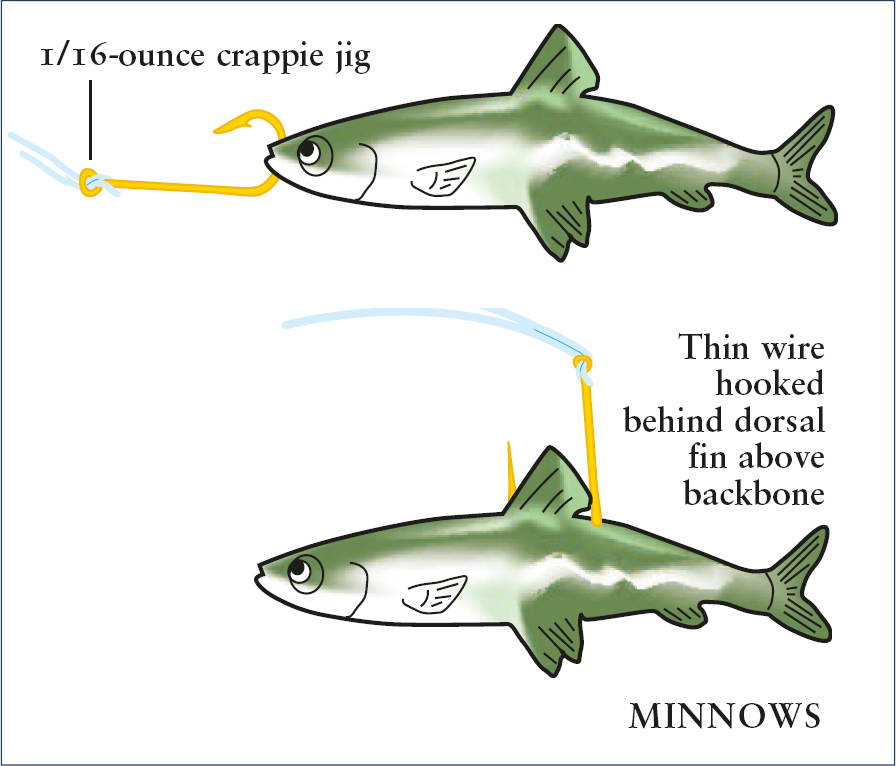

MINNOWS

Shiners, tuffies (fatheads), and goldfish are popular minnow species that are sold in bait stores. Also, other small minnows can be caught from ponds, streams, and lakes. Anglers routinely use minnows to catch crappies, bass, walleyes, saugers, catfish, white bass, stripers, northern pike, muskies, and other fish.

One of the easiest ways to catch minnows is to set a wire basket trap. (Most tackle stores or departments sell such traps.) Bait the trap with a piece of bread and drop it into a pond or creek where minnows live. Leave it for a few hours, then retrieve it with its catch inside. Minnows might also be seined or caught with a cast net. However, seines and nets are expensive, and both take a fair amount of know-how to use. I don’t recommend them for beginning fishermen.

Minnows must be cared for properly or they will die quickly. To keep them alive, use water from a pond or creek, or distilled water. Don’t use tap water because the water- purifying chemicals in it are likely to kill them. Keep their water cool and fresh. I use foam-plastic buckets instead of metal or plastic, because foam plastic keeps the water cooler. I never put more than four dozen minnows in a bucket to avoid overcrowding. If the water in a bucket becomes too warm or stale (oxygen is running out), the minnows will rise to the surface and start trying to gulp air, and you must take quick action to save them. Exchange the old water for fresh. On extremely hot days, add chunks of ice to keep the water cool. And you might consider purchasing a small battery-powered bait aerator to spray water into the bucket to maintain a good oxygen supply.

Minnows can be kept several days between trips so long as they stay in a cool place and their water is changed as often as needed.

When I fish with minnows, I put them on the hook one of two ways. If I’m using a stationary rig, I hook the minnow through the back under the main fin. This allows it to swim naturally. If I’m using a moving rig such as a bottom-bouncer, walking slip sinker or two-hook rig, I hook the minnow through both lips from bottom to top. And again, I frequently replace battered or dead minnows with fresh ones. New minnows always attract more bites.

Small minnows are effective on crappies, bass, white bass, and other species. Always keep a lively minnow on the hook. If a minnow dies or tires out, replace it with a fresh, wiggly one.

Crickets and grasshoppers are excellent baits for sunfish, bass, catfish, and trout.

You can catch grasshoppers in grassy or weedy fields either by hand or with a butterfly net. Or better yet, you and a friend can open a fuzzy wool blanket and run through a field into the wind. The grasshoppers will try to fly away, but the wind will blow them into the blanket, and their legs will stick in the fuzz. For crickets, look under rocks, planks or logs, and grab them by hand or with a net. (Watch out for poisonous spiders and snakes when doing this!)

Place grasshoppers or crickets in a cricket box from a tackle store, or make your own container by punching holes in a coffee can that has a plastic lid. Cut a small round hole in the lid and keep it covered with masking tape. Peel the tape back to deposit grasshoppers or crickets as you catch them. When you want to get one out, peel the tape back, shake an insect out of the hole, and then stick the tape back over the hole.

Grasshoppers and crickets should be stored in a cool, shady place. Each day add a damp paper towel for moisture and a tablespoon of corn meal for food.

Grasshoppers and crickets are normally used with bobber rigs or bottom rigs. They are hooked by inserting the point behind the tail and running it the length of the body and out at the head.

CRAWFISH

Crawfish are found in most freshwater lakes and streams. Many anglers think of them as good bass baits (smallmouths love them!), but they are also deadly on catfish. Pieces of crawfish tail are irresistible to sunfish, too.

The best way to gather crawfish is to go wading in a shallow stream and slowly turn over flat rocks. When you see a crawfish, ease a tin can (with holes punched in the bottom) up behind it and then poke at its head with a stick. Crawfish swim backward to escape, so it should back up into the can. When the crawfish goes in, lift the can quickly.

Keep crawfish in a foam-plastic minnow bucket half-filled with pond or creek water. They can be kept several days if refrigerated.

When handling crawfish, be careful to avoid their pinchers, which can cause painful injury. Hold them by the body just behind the pinchers.

A broad variety of natural baits can be collected from nature. For instance, in late spring, large yellow and black worms infest catalpa trees in many regions, and these worms are a choice food for catfish. They can’t resist them!

Live crawfish should be hooked in the back section of the tail, from the bottom through the top. They are usually fished on or near bottom with a standard bottom rig or live-bait rig. They can also be trolled slowly along bottom with a slip-sinker rig or bottom bouncer. And once in a while they should be fished just above bottom with a bobber rig.

For smaller panfish, cut a fresh crawfish tail into several pieces and apply one to a small hook or jig dangled under a bobber.

LEECHES

Several kinds of leeches inhabit North American waters, but only ribbon leeches are widely used for bait. These leeches squirm actively when held; less desirable leeches seem lifeless when held. Ribbon leeches are used primarily to catch walleyes and bass.

To trap leeches, put dead minnows, liver, beef kidney, or bones into a large coffee can and mash the top of the can almost shut. Sink the can in leech-infested waters overnight, and rapidly pull the can up the next morning. Leeches keep for a long time in a foam-plastic minnow bucket filled with natural water and placed in the shade.

Leeches work well suspended under a bobber, since they squirm continuously. They may be trolled or crawled across bottom on a live-bait rig, slip-sinker rig, or bottom-bouncer rig. They are also frequently used as a trailer on a leadhead jig. To hook a leech, run the point of the hook through the head.

MAKING SENSE OF FISH SCENT

Tackle store shelves are lined with scent products designed to make fish bite more eagerly and to hold onto a bait longer. These products come in two forms: scent-impregnated baits (the scent is molded into the bait); and add-on scents, which are applied to baits either by spraying or smearing on.

Do these products really work? My best answer is that some probably work some of the time, and some better than others. Confusing? Biologists know that many fish species have a well-developed sense of smell. Also, testing by independent laboratories indicates that scent application sometimes increases the chance that fish will bite and hold onto a lure longer.

That’s not to say that scent products are magic potions that will cause inactive fish to go into a feeding frenzy all of a sudden. A scent might persuade a borderline fish that’s inspecting a bait to bite it. But don’t expect miracles to happen if you start using scents or scented lures.

In my opinion, scents are most effective when used on slow-moving artificial baits such as plastic worms, jigs, grubs, etc. I don’t use them on fast-moving baits such as crankbaits and spinnerbaits. These are more visual/reaction baits. Fish don’t have time to sniff them before they decide to bite or let them pass.

However, fish might have the opportunity to follow, observe, and smell slower-moving baits. A natural or inviting smell could generate just enough persuasion to cause a curious or undecided fish to feed. Or, if it bites into a plastic worm, lizard, crawfish, tube, or swimbait that’s scent-impregnated, the fish might hold on longer and allow the angler more time to set the hook.

I can’t say with complete certainty that scents have ever helped me, but I think they have. Each angler has to decide for himself whether or not to use scent products. The fishing-scent industry is built on the basis that scents help anglers increase their catch. If you experiment with scents and think they help, it will increase your confidence and concentration and make you a better fisherman in the long run, whether the scent really works or not.

CUT BAIT

Pieces or entrails of baitfish are excellent for catching catfish. Larger shad, herring, smelt, and other oily baitfish are best. These can be netted, cut into chunks of an inch square, and hooked onto bottom rigs. Since catfish are scent feeders, they home in on the oil and blood escaping from cut bait.

Also, a small slice of panfish meat adds to the attraction of a small jig for sunfish, white bass, crappies, and yellow perch.

OTHER NATURAL BAITS

Baits listed above are the most popular natural baits, but they are not the only good ones. Many others are very effective on various fish species. Meal worms, wax worms, waterdogs, frogs, mayflies, salmon eggs, hellgrammites, grubs, catalpa worms, spring lizards, and mussels are excellent baits for different species of fish.

WHOPPER PLOPPER

HEDDON ZARA SPOOK

ARBOGAST JITTERBUG

STRIKE KING ELITE BUZZBAIT

USING ARTIFICIAL BAITS

Live worms and leeches wiggle on the hook. Live minnows swim. Live crawfish scoot across rocks or mud. But artificial baits hang motionless in the water until the angler gives them life by casting and retrieving. In most cases, the more skillfully this is done, the more fish an angler will catch. This is why many fishermen consider artificial baits more challenging than natural baits. You’ve got to add the life!

Following are short descriptions of various artificial lures and how to use them.

TOPWATERS

Bass, muskies, pike, stripers, white bass, trout, and other species feed on the surface, normally in warm months and low-light periods of early morning, late afternoon, night, or cloudy weather. Sometimes, though, fish will hit topwaters in the middle of a bright day if that’s when baitfish are available to them. Basically, if you see surface-feeding activity, give topwaters a try.

Topwater baits include wood, hard-plastic and soft-plastic lures in a broad variety of shapes and actions.

Poppers (also called “chuggers”) have scooped-out heads which make slapping sounds when pulled with short, quick jerks.

Minnow imitators rest motionless and then swim with a quiet, subtle side-to-side action when reeled in or worked with a jerk-and-pause retrieve.

Stickbaits resemble cigars with hooks attached. They dart across the surface in a zig-zag pattern when retrieved with short, quick snaps of the rod tip.

Crawlers have concave metal lips or paddle tails that rotate around a metal shaft on the retrieve. This bait makes “plopping” sounds on a steady retrieve.

Buzzbaits have revolving metal or plastic blades that boil the water on a steady retrieve.

Soft-plastic frogs are especially good when fishing thick weed mats, shady areas along a bank or any time bass are holding in heavy cover.

If fish are actively feeding at the surface, use a lure that works fast and makes a lot of noise. But if fish aren’t active, select a quieter lure and work it slowly. (In this case, after the lure hits the water, let it sit still until all ripples disappear. Then twitch the lure slightly, and hold on!)

Plastic worms are among the most popular soft plastic lures, and are top producers of trophy bass. These lures are typically worked along bottom through stumps, brush, rocks, and other cover where bass hang out.

When casting a topwater lure, be ready for a strike when it hits the water. Sometimes fish see it coming through the air and take it immediately.

When a fish strikes a topwater lure—especially a frog—wait until the lure disappears underwater before setting the hook. This takes nerves of steel, since the natural tendency is to jerk the instant the strike occurs. However, a short delay will give the fish time to take the lure down in its gullet and turn away with it, which increases your chance of getting a good hookset.

SPINNERS

This bait category includes spinnerbaits and in-line spinners. Spinnerbaits are shaped like an open safety pin. One or more rotating blades are attached to the upper arm; a leadhead body, plastic skirt, and hook are on the lower arm. This design makes a spinnerbait semi-weedless so it can be worked through vegetation, brush, timber, and stumps with few hang-ups.

Spinnerbaits come in a wide variety of sizes and blade configurations. Some have one blade while others have two or more. Some have Colorado or Indiana blades (oval-shaped) for slower vibrations with more “thump,” while others have willowleaf blades (elongated/pointed) for faster, higher-pitched vibrations. Colorado/Indiana blades are better for slower retrieves for inactive fish, at night or in murky water. Willowleaf blades are made to retrieve at a faster rate (especially in current) and for fish that are actively chasing baitfish.

JOHNSON RATTLIN’ BEETLE

ABU GARCIA REFLEX SPINNER

STRIKE KING BLEEDING BAIT SPINNERBAIT

STRIKE KING COMPACT SILHOUETTE SPINNERBAIT

MEPPS AGLIA

Spinnerbaits are normally associated with bass fishing, but they’re also productive for muskies and pike. Small spinnerbaits with soft-plastic bodies can be effective on small panfish such as bluegills and crappies.

The blade of an in-line spinner is attached to the same shaft as the body, and it revolves around it. Because of this compact design, in-line spinners work well in current. These lures are typically used for smallmouth bass, white bass, rock bass, trout, and other stream species.

Spinners are a good artificial lure for beginning anglers. In most cases, all you have to do is cast them out and reel them in. As your skills increase you’ll learn to vary retrieves and crawl spinnerbaits through cover or across bottom. In any case, when you feel a bump or see your line move sideways, set the hook immediately!

CRANKBAITS

This is another good lure family for beginners. Crankbaits have built-in actions. All you have to do is cast them and then crank the reel handle. The retrieve causes these baits to wiggle, dive, and come to life.

Crankbaits are used mainly for largemouth and smallmouth bass, white bass, walleyes, saugers, muskies, and pike. They are effective in reservoirs, lakes and streams. Fish them around rocks, timber, docks, bridges, roadbeds, drop-offs and other structure or cover. Generally they’re not effective in vegetation, since their treble hooks foul in the weeds. However, crankbaits can be effective retrieved close to weeds or over the top of submerged vegetation.

There are two sub-categories of crankbaits: “floater/divers,” and “vibrating.” Floater/divers usually have plastic or metal lips. They float on the surface at rest, but when the retrieve starts, they dive underwater and wiggle back and forth. Usually, the larger or longer a bait’s lip, the deeper it will run.

One of the secrets to success with floater/divers is to keep them bumping bottom or cover such as submerged trees. To do this, you must retrieve them so they will dive as deeply as possible. Maximum depth might be achieved by (1) using smaller line (6- to 12-pound test is perfect), (2) cranking at a medium speed instead of too fast, (3) pointing your rod tip down toward the water during the retrieve, and (4) making long casts. Once the bait hits bottom, vary the retrieve speed or try stop-and-go reeling to trigger strikes. Keep it working along bottom as long as possible before it swims back up to the rod tip. Sometimes a floater/diver crankbait gets “out-of-tune” and won’t swim in a straight line. Instead, it veers off to one side or the other. To retune a lure, bend the eye (where you tie the line) in the direction opposite the way the lure is veering. Make small adjustments with a pair of needle-nose pliers and test the lure’s track after each adjustment to get it swimming straight.

Vibrating crankbaits are used in relatively shallow water where fish are actively feeding. These are sinking baits, made of plastic or metal, so the retrieve must be started shortly after they hit the water. They should be reeled quickly to simulate baitfish fleeing from a predator. This speed and tight wiggling action excites larger fish into striking.

Diving crankbaits come in a broad range of sizes and designs. One of the secrets to success with diving crankbaits is to keep them digging along bottom. Anglers should learn how deep various crankbaits dive, then select one that best matches up with the water depth where they’re fishing.

SOFT PLASTICS

This huge family of baits includes plastic worms, grubs, minnows, tubes, lizards, crawfish, eels, and other live bait imitations. These baits are natural-feeling and lifelike to fish. They are used mainly to trick largemouth, smallmouth, and spotted bass as well as white bass, stripers, panfish, crappies, walleyes, and other species.

Soft plastics are very versatile lures. They can be fished without weight at the surface or they can be weighted with a sinker or jighead and fished below the surface. They can be rigged weedless and fished through weeds, brush, rocks, or stumps.

Lures come in every color, shade, and pattern imaginable. Manufacturers use colors to capture the fancy of anglers who buy their lures. Less-experienced anglers almost always ask about the color of a lure another fisherman used to make a good catch. We’re tuned in to colors, but I think we give lure color more credit than it deserves in fishing success.

I do pay attention to color, but I don’t think it’s critical in making a good catch. That said, I’ve seen times when fish were very color-specific. They wanted one color and nothing else. Still, for those few times, I’ve seen many more when the fish would hit any of several colors presented to them.

When choosing lure color I normally stick to what’s natural to the fish. If they’re feeding on shad I’ll use a shad-colored lure. If they’re feeding on crawfish I want a bait with an orange belly and brown or green back.

There are exceptions to this rule. If the water is muddy I prefer bright lures that show up better in the murk. If the water is clear I favor white or chrome crankbaits and spinners or translucent soft-plastic baits.

Again, seek advice about lure colors for particular lakes or reservoirs. But stick with the basic colors and concentrate more on fish location and depth.

Plastic worms are among the most popular of soft-plastic lures. The most common way to use them is to crawl or hop them along bottom structure. To do this, rig the worm according to the instructions under Texas-Rigged Plastic Worms in the previous chapter.

Use a small slip sinker for fishing shallow water and a heavier sinker for deeper water. A good rule of thumb is to use a ⅛-ounce slip sinker in depths up to six feet, a ¼-ounce sinker from six to 12 feet, and a ⅜- to 1/2-ounce sinker in water deeper than 12 feet.

Cast the worm toward the structure and allow it to sink to the bottom. (You’ll feel it hit or see your line go slack.) Hold your rod tip in the 10 o’clock position and reel up slack. Then quickly lift the rod tip to the 11 o’clock position without reeling. This lifts the worm off bottom and swims it forward a short distance. Allow the worm to fall back to the bottom, reel up slack line, and repeat the process. This lift/drop/reel sequence should be repeated until the worm exits the main target area (drop-off, rock bluff, tree top, brush, weedbed, etc.). Then, reel it in and cast to the next target.

BILL LEWIS RAT-L-TRAP BLEEDING SHAD

BOMBER MODEL 8A

When hopping a plastic worm, be alert for any taps or bumps, and always watch your line for sudden, unnatural pulses or sideways movements. Sometimes strikes are obvious and easy to detect. Other times they are light and subtle. If you know you’ve got a bite, reel up slack line and set the hook immediately. But if you’re not sure, reel up slack and hold the bait still for a few seconds. If nothing happens, tug on the bait ever so slightly. If you feel something tug back, set the hook!

To set the hook with a plastic worm, lower your rod tip to the 9 o’clock position, then set hard and fast with your wrists and forearms. If you don’t feel that you have a good hookset, set again. This method applies to tackle spooled with line above 10-pound test. When you’re using lighter line, set with less force, or you may break your line.

Virtually all soft-plastic baits can be fished with the same lift/drop/reel technique described above. Also, grubs can be hopped along bottom or swum through mid-depth areas with a steady retrieve. Lizards and eels can be slithered through weeds and brush. Minnows can be threaded through sunken flats and timber. Crawfish can be bumped through rocks. Weightless worms and plastic stick lures can be worked over sunken vegetation and other cover. Experiment with various baits to see which the fish prefer. Remember, too, that soft plastics can be fished effectively using Carolina or drop-shot rigs, as noted in the preceding chapter. What rig you choose often depends on the water depth and apparent mood of the fish. Figuring out what the fish want, and how they want it, is all part of the fun.

Zoom Horny Toad

Strike King Rage Tail Claw

Yamamoto Senko

Culprit Water Dragon

SWIMBAITS

In recent years, swimbaits have gained popularity because of their versatility in all sorts of fishing conditions and water depths. All gamefish seem to like them. These hard- or soft-plastic lures mimic baitfish of various sizes and can be fished unweighted by themselves or on jigheads. The hard-plastic models that mimic the look and action of real fish are weighted and typically have a jointed body that gives them more action when they’re reeled slowly along.

Soft-plastic lures are effective on many types of fish. Soft plastics include worms, grubs, lizards, frogs, and other natural bait imitations.

Soft-plastic swimbaits rigged on jigheads usually are anywhere from four to eight inches long and have paddle or boot tails that produce maximum action on the retrieve.

Perhaps the most popular way to fish soft-plastic swimbaits from boats is with umbrella rigs. These rigs consist of three or more wire arms with snaps. Weighted or unweighted swimbaits rigged with hooks are connected via the snaps, and then the umbrella rig is tied to the line and ready to fish. An umbrella rig can be cast out and retrieved by the angler, or trolled. Whichever presentation is used, these rigs are relatively heavy and require tackle to match. The added attraction of three or more baitfish seemingly swimming together sometimes is too much temptation for any predator fish to ignore. Be sure to check your state’s regulations regarding how many baits and hooks you can fish on an umbrella rig before trying one.

JIGS

If there’s such thing as a universal bait, the leadhead jig is it. These balls of lead with hooks running out the back can be used in a wide range of circumstances to catch almost all freshwater fish. Jigs are basic baits that all anglers should learn to use.

Jigs come in a wide range of sizes. Tiny jigs (1⁄32 ounce) will take trout or small panfish in shallow water. A 1-ounce jig might be used to bump bottom in heavy current for walleyes or saugers. The most popular jig sizes are  , ⅛, and ¼ ounce.

, ⅛, and ¼ ounce.

Many veteran anglers keep jigs of different sizes and weights in their tackle boxes and then select the right size for a particular fishing situation. This selection is based on the size of the target fish, depth of water, and amount of wind and current. The bigger the fish, the deeper the water, and the stronger the wind and current, the heavier the jig should be.

Jigs are almost always “dressed” with an artificial trailer or live bait. Some jigs are made with hair, feathers, or rubber skirts wrapped around the hook. Others come pre-rigged with plastic grubs. But the majority of jigs are sold without any trailer, leaving this choice up to the angler. You can add your own trailer (plastic grub, booted swimbait, tube, small worm, or pork rind), or you might prefer hooking on a live minnow, nightcrawler, or leech. Also, in addition to trailers, some jigs have small spinners attached to the head of the lure to add flash. Another version has a metal blade attached to the front. This type is known as a “vibrating jig” and often fished in and around shallow cover.

There are several effective jig retrieves. The basic one is the lift/drop: Allow the jig to sink to bottom, then hop it along bottom with short lifting jerks of the rod tip. (This is similar to the lift/drop/reel method for fishing a plastic worm, except faster.) The steady retrieve is popular, too, especially when fishing with a vibrating jig. Here, the angler swims the jig over submerged weeds, in open water or just above bottom. As it moves along, the jig sometimes grazes stumps, rocks, or other cover to attract the attention of aggressive bass.

A third retrieve is vertical jigging. Lower the jig straight down to bottom or into cover, lift it with the rod tip, then allow it to sink back down. Most strikes come when the bait is dropping.

As with plastic worms, jig strikes might be very hard or extremely light. An angler using a jig will usually feel a bump or “tick” as a fish sucks in the bait. The key to detecting such takes is keeping a tight line at all times. If you feel a bump or see unnatural movement, set the hook immediately. There’s no waiting with jigs.

SPOONS

Metal spoons are the “old faithfuls” of artificial lures. They’ve been around a long time, and they’re still producing. They are excellent for catching bass, walleyes, pike, muskies, and white bass.

Some spoons are designed to be fished at the surface, while others are for deep-water use. In both cases, the standard retrieve is a slow, steady pull. Sometimes, however, an erratic stop-and-go retrieve might trigger more strikes.

One special use for spoons is fishing it around or through weeds and surface-matted grass. Topwater spoons will ride over the thickest lily pads, moss, etc. Spoons retrieved underwater will flutter and dart through reeds and grass with minimal hang-ups. In this situation, a spoon with a weedguard covering a single hook is recommended. Recently, big “hubcap” spoons that are several inches long have found favor among summertime bass fishermen. These spoons are worked over ledges and other offshore bass haunts with a “rip-and-let-fall” retrieve.

Z-MAN CHATTERBAIT

BOMBER FLAIR HAIR JIG

STRIKE KING DENNY BRAUER PREMIER PRO-MODEL JIG

STRIKE KING BLEEDING BITSY BUG JIG

Different baits serve specific purposes. Beginning anglers must learn what various baits are designed to do, then apply them where they work best. For instance, this jig/minnow combo is good for bumping along bottom for walleyes, saugers, crappies, and other panfish.

Trailers are frequently added to a spoon’s hook for extra attraction. Pork strips or plastic or rubber skirts are standard trailers. When adding a skirt to a spoon’s hook, run the hook’s point through the skirt from back to front so the skirt will billow out during the retrieve.

SUMMARY

In Chapter 4, I described rods, reels, and line as “tools” for fishing. Baits are also tools in the truest sense. They are objects designed to help you catch fish. Different baits serve specific purposes. You must learn what various baits are designed to do and apply them where they work best.

You start to do this by reading, but then you must apply what you read on the water. There’s no better teacher than experience. Lakes and streams are your laboratory. This is where you’ll carry out your experiments with various fishing tools.

COTTON CORDELL GRAPPLER SHAD

LUHR-JENSEN RADAR 10

STRIKE KING WILD SHINER SUSPENDING JERK BAIT

JOHNSON SPRITE SPOON

Now you’re ready to put the entire package together. You’ve learned about different fish species, where to fish, tackle, accessories, rigs, and baits. We’re finally ready to go fishing, to learn simple ways to catch fish from different types of waters. Let’s move forward into what’s probably the most important chapter in the Scouting Guide to Basic Fishing.

Ethics & Etiquette

Leave It As You Found It! Don’t litter.

Never leave trash on the shore, toss it out of the boat or car window, or sink cans in the water. Don’t leave anything behind after a day’s fishing except footprints in the mud or sand.