BASIC FISHING TECHNIQUES

Before becoming an outdoor writer, I was a pilot in the US Air Force. I now realize that in a way, flying and fishing are alike. You can read books about flying for years, but before you climb into a cockpit you don’t know what flying is really like. Reading won’t teach you how to take off, hold the wings straight and level, and land a plane. You have to get up in the clouds before you’ll really get the feel of flying.

The same is true about fishing. You can read about fishing, but you’ll never be a fisherman until you put your book knowledge to practical use. This is where we’ll get specific. This chapter will teach you practical, step-by-step techniques for taking fish from various spots.

In essence, then, this chapter is the heart of the Scouting Guide to Basic Fishing. Now we’ll talk mechanics of fishing, not theories. We’ll cover exactly how to approach different situations. You’ve already learned about various species, how to find places to fish, select tackle and accessories, tie rigs, and choose baits. This was all background material to prepare you for what’s in this chapter, where we’ll bind everything together.

When fishing ponds and small lakes, anglers should concentrate on areas close to the bank, especially where there is some type of cover (weeds, brush, logs, docks, etc.) They should keep moving and trying new areas until they learn where sunfish, bass, crappies, and other species are holding.

Obviously it’s impossible to cover all techniques for all fish. Instead, we’ll look at the best opportunities and simplest techniques. Also, I’ll help you identify prime fishing locations in different types of waters, then tell you how to make them pay off.

WHERE FISH LIVE

The first step in catching fish is knowing where to find them. On each outing, regardless of where you go and what species you’re after, you must first study your water to determine where fish are located.

This is the key in determining where fish are holding and where you can catch them. Remember that most fish gather in predictable places, and these places fall into what we call “structure.”

Various waters have different types of structure. In this chapter, I’ll identify structure specific to ponds, lakes, streams, and rivers and I’ll explain how to fish them. First, you need to figure out where fish are most likely to be found. Then decide which combination of tackle, bait and method will be most effective in catching them.

You should go through this process each time you fish. First, location. Where should the fish be? Then, presentation. What’s the best way to catch them? Follow this outline, and your fishing efforts will be orderly and successful instead of haphazard and ineffective.

A big catch like this largemouth bass comes through knowing where these fish live and which lure and techniques will get them to bite. In this chapter we’ll talk specifics about how to catch fish from the broad variety of North American waters.

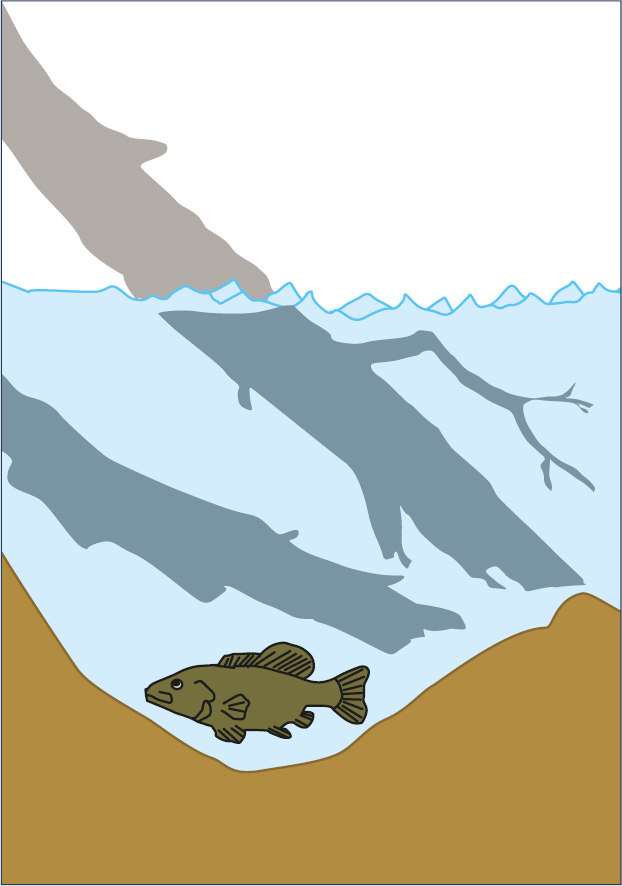

A fallen tree or log can form an ideal hiding place for bass, sunfish, and other species. Be sure to carefully scout a small lake or pond for such underwater cover.

HOW TO FISH PONDS AND SMALL LAKES

Farm ponds and small lakes are scattered throughout North America. They are the most numerous of all fishing waters and are some of the best fishing spots.

A lot of ponds were formed naturally by beavers, mudslides, glaciers, etc. However, many ponds and small lakes were manmade to provide water for livestock, irrigate fields, and prevent erosion. Other ponds and small lakes were built strictly for recreation.

Small bodies of water are excellent places to learn to fish, for two reasons. First, many of them have abundant fish populations, but little fishing pressure. So the fish aren’t spooky. Second, since these waters are small the fish are more confined and easier to locate. It doesn’t take as long to test different locations and techniques. For this reason, I like to think of ponds and small lakes as “training grounds” to prepare you to fish bigger waters.

ANALYZING PONDS AND SMALL LAKES

When you get to a pond or small lake, your fishing starts before you wet a line. First, you should study the pond to determine its characteristics. Some ponds have flat basins, while others have a shallow end with ditches running into it and a deep end with a dam. Many ponds have brush, weeds, trees, logs, rocks, or other cover around the banks or in the water. Take note of all the combinations of depths, structure and cover to determine which combination is holding the fish.

Again, consider your target species’ basic nature. Where a fish will be located varies according to the time of year and water conditions. For instance, bass might be in the shallows in spring and in deeper water along a drop-off in the summer. However, in the hottest months they might still feed in the shallows during night or at dawn and dusk. These are the types of factors you must learn before you can make an educated guess about where to find fish.

Don’t worry, you can learn the specifics of fish behavior as you go. For now, you can fish effectively if you follow the directions in the following section. These are basic methods that produce fish consistently from one season and set of conditions to the next.

Ponds and small lakes are plentiful throughout North America, and many offer very good action on fish that rarely see baits or artificial lures. These diminutive waters are great places for beginners to learn the basics of this sport.

TECHNIQUES FOR FISHING PONDS AND SMALL LAKES

Most ponds and small lakes support sunfish, crappies, bass, catfish, and bullheads. Some spring-fed ponds hold trout. Let’s take these species one at a time and look specifically at how to catch them.

SUNFISH

Bluegills and other small sunfish are my choice for someone just starting out in fishing. These are usually the most plentiful fish in ponds and small lakes and they always seem willing to bite. Learning how to fish for them will help sharpen fishing skills for other species.

In spring, early summer, and fall, sunfish stay in water of, say, 2 to 10 feet deep. In hottest summer and coldest winter, they normally move deeper, though they might still occasionally feed in the shallows. They might prefer structure such as a secondary drop-off, or a hump, especially if there is some sort of cover there.

One secret to fishing ponds and small lakes is to keep moving until you locate fish. A small boat will enable an angler to cover more water and prime fish locations.

As for cover itself, small sunfish love to hold around brush, logs, weeds, docks, and piers. On cloudy days or in dingy water, they might hang around the edges. This is true during the early morning and late afternoon. During the part of the day when the sun is brightest, especially in clear-water ponds, sunfish swim into brush or vegetation, under piers and docks, or close to stumps and logs. On sunny days, they like to hide in shady areas to escape the attention of predators.

If possible, get out early to fish for sunfish in a pond or small lake. Take a long panfish pole or light-action spinning or spincast rod and reel spooled with 4- or 6-pound-test line. Tie a fixed-bobber rig with a longshank wire hook (#6 or #8), a light split shot and a bobber. (Remember to balance the weight of your split shot and bobber as explained earlier!)

For bait, try earthworms, crickets, or grasshoppers. Thread a small worm up the shank of the hook, or use only a small piece of nightcrawler. A whole cricket or grasshopper is the perfect-size bite for a bluegill.

Next, adjust the bobber so your bait hangs midway between the surface and the bottom. If you can’t see bottom and you don’t know how deep the pond is, begin fishing two to four feet deep. If you don’t catch fish, experiment with other depths.

Let’s say you think sunfish might be holding around weeds growing close to the bank. Drop your bait in next to the weeds. The bobber should be floating upright. If it’s laying on its side, the bait is probably on bottom. In this case, shorten the distance between the bobber and hook so the bait will suspend above the bottom.

Be careful not to stand right over the spot you’re fishing, especially if the water’s clear. The fish will see you and become spooky. Sometimes it’s better to sit on the pond bank rather than stand. Wear natural-colored or camouflage clothing and avoid making any commotion that might scare the fish. Also, try to position yourself so that your shadow isn’t over the spot where your bobber is.

Sunfish will usually bite with little hesitation. If you don’t get a bite in a couple of minutes, twitch your bait to get the fish’s attention.

Carefully select locations to place your bait. Keep it close to cover, or structure such as a sharp ditch bend or where there is rock. If the fish are particularly stubborn, look for openings in cover where you can drop the bait without getting hung up.

If you’re not getting bites, try something different. Fish around another type of structure or cover. If you’ve been fishing in shallow water, try a deeper area. (Don’t forget to lengthen the distance between your bobber and hook.) If the pond has a dam, drop your bait close to it. If there is an overflow, aerator or fish feeder, try around those.

Most anglers who pond-fish walk the banks, but you have two other options. You can fish from a small boat to cover more water, or you can wade-fish. The latter technique is especially good in ponds with a lot of brush, cattails, or similar cover. In warm months, you can wade-fish in old pants and tennis shoes.

Don’t drop your bait at some random spot in the middle of the pond and then sit and watch your bobber for an hour. Keep moving until you begin catching fish. Then slow down and work the area thoroughly. Once you find a productive spot, stay with it as long as the fish keep biting.

A special opportunity exists during spring when sunfish are spawning. They fan nests in shallow water (two to five feet deep) around the banks and especially in the shallow end of a pond. Often you can see the nests. They’re about the size of a dinner plate and they appear light against the dark pond bottom. Usually, many nests will be clustered in the same area.

When you see these “beds” set your bobber shallow and drop your bait right next to them, trying not to spook the fish. You might be better off casting into the beds rather than sneaking in close with a long pole. Sometimes it’s best not to use a bobber and simply cast the bait rigged on a drop-shot rig into the bedding area.

CRAPPIES

Fishing for crappies in ponds and small lakes is similar to fishing for bluegills and sunfish. Always fish close to cover, especially where there are structure changes such as drop-offs. Stay on the move until you find fish. Crappies prefer minnows over other natural baits and they readily attack small jigs and spinners.

Long poles are a favorite with crappie fishermen. Many crappie experts quietly scull a small boat from one piece of cover to the next and use a panfish pole to dangle a float rig with a minnow or jig. They ease their bait down beside a tree or piece of brush, leave it for a moment, pick it up, set it down on the other side, then move to the next spot.

In small lakes and ponds, crappies scatter throughout such shallow cover, and this “hunt-and-peck” method of fishing is very effective. This is especially true in spring when the fish move into shallow cover to spawn. You can also use this method while wade-fishing or fishing from shore, if the cover is within reach.

Another good crappie technique is to use a slip-bobber rig (See “Rigs For Everyday Fishing,” page 69) with a spinning or spincast outfit. Hook a live minnow through the back onto a thin wire hook (#2) or through the lips on a lightweight ( or

or  ounce) jig. Then cast this rig next to a weedline, brushpile, creek channel, or log.

ounce) jig. Then cast this rig next to a weedline, brushpile, creek channel, or log.

If you don’t get a bite in five minutes, try somewhere else. If you get a bite, don’t yank if the bobber is just twitching. Wait for the bobber to start moving off or disappear beneath the surface before setting the hook. Crappies have soft mouths, so don’t set too hard or you’ll rip out the hook. Instead, lift up on your pole or rod, and you should have the fish.

If you don’t catch fish shallow, try deeper water, especially during hot summer months or on bright, clear days. Adjust your bobber up the line and drop your bait right in front of the dam or off the end of a pier. Try casting into the middle of the pond where the creek channel runs and see what happens. With this method of fishing, 6 to 10 feet is not too deep. There is less certainty in this technique, however, because you’re hunting for crappies in a random area. Once you catch one fish, though, you can bet there will be other crappies nearby.

To cover a lot of water, cast a 1⁄16-ounce jig or a small in-line spinner. After casting, count slowly as the bait sinks. After a few seconds, begin your retrieve. Try different counts (depths). If you get a bite, let the bait sink to the same count next time. You might have found the depth where crappies are holding. This technique is called the “countdown” method of fishing with a sinking bait.

When retrieving the jig, move it at a slow to moderate pace and alternate between a straight pull and a rising/falling path back through the water and mindful of whatever structure is there. With the spinner, a slow, straight retrieve is best. Crappies will usually bite if you pull either of these baits past them.

BASS

Bass fishing is more complicated than fishing for sunfish or crappies, partly because of all the different types of bass tackle and lures. Still, bass are members of the sunfish family and they share certain behavioral characteristics with bluegills and crappies. If those fish are present, bass are likely to be in the same neighborhood.

Let’s begin with the simplest technique. You can catch bass on a long cane or fiberglass pole, but you need a stronger pole than you used for bluegills. And your line should be at least 12-pound test.

Tie on a slip-bobber rig with the bobber set at around three feet. Use a 1/0 or 2/0 steel hook. Add a light sinker six inches up from the hook. Then bait this rig with a gob of nightcrawlers or a live minnow hooked through the back.

Drop your line near likely fish-holding spots, but don’t leave it in one place for more than two or three minutes. If a bass is there it’ll usually take the bait. When you get a bite, wait for the bobber to disappear before setting the hook. Then pull the fish quickly to the surface and land it.

When using the long-pole method, work your way around the pond, keeping your shadow behind you and being careful not to let the fish see you. They are skittish when they’re in shallow water and they’ll spook easily.

While this long-pole method is a good one, most experienced fishermen go after pond bass with casting or spinning tackle and artificial lures. Casting allows you to reach targets farther away and also to cover more water. Many artificial lures will catch pond bass, but my three favorites are topwaters, spinnerbaits, and plastic worms.

Try topwaters early in the morning, late in the afternoon, or at night (during summer). Also fish topwaters when the sky is overcast, especially if the surface is calm. In warmer months, I prefer poppers and propeller baits that make a lot of noise and attract bass from a distance. In early spring, I like a quieter floating minnow.

Cast topwaters close to weeds, beside logs, next to drop-offs, along dams or anywhere you think bass might be holding. Cast beyond a particular object and work the bait up to where you think the fish are. Allow the bait to rest motionless for several seconds, then twitch it just enough to cause the slightest ripple on the water. This is usually when the strike comes!

If a spot looks good, but you don’t get a strike, cast back to it several times. Sometimes when bass are “inactive” (aren’t feeding), you have to arouse their curiosity or agitate them into striking and it might take a few casts.

At times, though, bass just won’t strike a surface lure. If you don’t get any action on a topwater lure within fifteen minutes, switch to a spinnerbait and try the same area. Keep your retrieve steady and try different speeds (fast, medium, slow). You might try “fluttering” the bait, which is allowing it to sink momentarily after it runs past a log, treetop, or over any change in the bottom. This can trigger a strike from a bass that’s following the lure during a steady retrieve.

Little waters can yield some big catches like this lunker bass. A good way to go after bass in ponds and small lakes is to wadefish. Wading allows you to slip up close to bass hiding spots and present a bait in just the right location.

Don’t be afraid to retrieve a spinnerbait through brush and weeds. If you keep reeling while it’s coming through cover, this lure is virtually weedless. You might hang occasionally (use strong line with these baits so you can pull them free), but you’ll get more strikes by fishing the thick stuff.

Plastic worms are what I call “last-resort baits.” Bass can usually be coaxed into striking worms when they won’t hit other lures, and plastic worms can be worked slower and through the thickest cover. They’re also good for taking bass in deep water. Plastic worms are top prospects for midday fishing in hot weather.

For pond bass, use a 4- to 7 ½-inch plastic worm rigged Texas-style with a  - to ¼-ounce sliding sinker. (The heavier sinker is for deeper water.) Cast it right into cover or close to it. (Make sure the point of the hook is embedded inside the worm.) Then crawl it slowly through the cover, alternately lifting it with the rod tip and allowing it to settle back to the bottom.

- to ¼-ounce sliding sinker. (The heavier sinker is for deeper water.) Cast it right into cover or close to it. (Make sure the point of the hook is embedded inside the worm.) Then crawl it slowly through the cover, alternately lifting it with the rod tip and allowing it to settle back to the bottom.

When fishing lily pads, brush, or other thick vegetation, cast to openings and pockets. Cast to spots off points, ends of weedbeds or riprap, and under piers. These are places where bass are likely to hang out in hopes of ambushing passing prey.

If you don’t get action in the shallows, and you suspect the bass are deeper, it’s time to change tactics. Since you can’t see under the water, you must locate cover or structure features in the bottom such as a winding creek channel. Interpret what you can from the surface. Find a gully feeding into the shallow end of the pond. Then try to imagine how this ditch runs along the pond bottom, and cast your plastic worm along it. This can be prime bass-holding structure.

A spinnerbait is a super-productive lure for catching bass in ponds and small lakes. This is an easy lure to use. Simply cast it and reel back with a steady, medium-paced retrieve. Most strikes come around cover where bass like to watch for prey.

A second deep-water strategy is to cast a plastic worm into the deep end or along the dam, then crawl it back up the bank. The third option is simply to walk along the bank and cast at random, hoping you’ll locate bass along some invisible cover or structure change under the water. In all cases, however, it’s very important to allow your plastic worm to sink to bottom before starting the retrieve. When casting to deep spots, if you get a bite or catch a fish, cast back to that same spot several more times. Bass often school together in deep water.

There are other rigs or baits you might use in special situations. Try a drop-shot rig with a small plastic worm or swimbait. Many ponds have heavy weedbeds or lily pads and you can fish them with a topwater spoon. When retrieved fast enough to keep it near the surface, the spoon wobbles over plants and attracts bass waiting underneath. Leadhead jigs tipped with a plastic trailer (grub, crawfish, etc.) can be hopped across bottom when searching deep-water areas. Diving crankbaits are good for random casting into deep spots.

CATFISH/BULLHEADS

Catfish and bullheads spend the most time on or near the bottom of small ponds and lakes, so this is where you should fish for them. While they prefer deep water, they might move up and feed in the shallows from time to time. In either location, fish directly on bottom without a float or just above bottom with a float.

While you move a lot searching for sunfish, crappies, and bass, fishing for catfish and bullheads calls for a pick-one-spot-and-wait-’em-out method. These fish find their food mostly through their sense of smell and you have to leave your bait in one place long enough for the scent to spread through the water and for the fish to home in on it.

It’s possible to fish for these species with long poles, but spincast or spinning outfits allow you to fish farther off the bank. Take at least two rods, then pick a spot on the bank close to deep water. Cut a forked stick for each rod and push the sharpened end into the ground next to the pond’s edge. Cast out your lines, prop the rods in the forked sticks, and watch and wait for something to happen.

A variety of lures can be used to catch stream bass and smaller panfish. Spinners, diving crankbaits, topwater minnows, and plastic worms and tubes are all deadly on fish that inhabit small moving waters.

When using two rods, it’s wise to tie a bottom rig on one and a slip-bobber rig on the other. This gives the catfish or bullheads a choice of a bait laying on bottom or hanging just above.

Catfish grow much larger than bullheads, so if they’re your main target, you need larger hooks. Start out with a #1 or 1/0 Sproat or baitholder hook. If you’re fishing for bullheads, select a smaller #6 hook. If you’re trying for both species, use something in between such as a #2 or #4.

Catfish and bullheads will eat the same baits. Earthworms or nightcrawlers are two favorites. Chicken liver, live or dead minnows, grasshoppers, and a wide variety of commercially prepared baits also work well. Regardless of the bait, be sure to load up your hooks. The more bait on them, the more scent you have in the water and the more likely you are to attract fish.

Carefully examine small ponds for features that provide fish-holding areas. These could be sunken timber and brush piles, shallow weed beds, or a submerged creek channel, for instance.

Cast your baited lines into deep water. With the bottom rig, wait until the sinker is on bottom, then carefully reel in line until all the slack is out. With a slip-bobber rig, set the bobber so the bait is suspended just above bottom.

Now, just relax and wait. When a fish takes the bottom-rig bait, the rod tip will first begin to bounce and then bend in a steady pull. When there’s a bite on the slip-bobber bait, the bobber will dance nervously on the surface.

If you get a bite don’t set the hook until the fish starts swimming away with the bait. Pick up the rod and get ready to set the hook, but don’t exert any pull until the line starts moving steadily off or the bobber goes under and stays. Then strike back hard and begin playing in your fish.

If you’re not getting bites, how long do you stay in one place before moving to another? Probably the best answer is “as long as you can stand it.” The best catfishermen are usually the ones with the most patience. At a minimum, you should fish in one spot at least twenty minutes before moving somewhere else.

Catfish like to feed in lowlight periods of dawn, dusk, or night. For night fishing, buy a small metal bell and fasten it to the end of your rod. When you get a bite, the bell will ring and let you know that a fish is at the bait.

TROUT

Trout are generally thought of as fish of streams and large lakes. However, they can also live in cool-water ponds. Northern beaver ponds are great places for wild brook trout, and spring-fed manmade ponds can sustain stocked rainbows.

Trout do not relate to structure and cover the way warm-water fish do. They roam a pond or small lake and are likely to be found at any depth. The best way to find them is to walk the bank and try different areas. You can catch trout on either natural bait or artificials. Use spincast or spinning tackle and 4- or 6-pound-test line. For fishing natural bait, use either a bobber rig or a very light slip-sinker rig. Bait with a nightcrawler, grasshopper, preserved salmon eggs, whole kernel corn, or commercially made scented baits that replicate various worms, minnows and insects. Use a #8 short-shank hook.

A boat is a definite help in fishing a large lake or reservoir. Anglers who can move around and fish away from the bank have a better chance of success on these larger waters.

If you prefer artificials, stick with tiny crankbaits, sinking spoons, in-line spinners (probably the best of all), and minnow lures. If you’re casting a lure that sinks, use the countdown method to fish different depths.

HOW TO FISH LARGE LAKES AND RESERVOIRS

Large lakes and reservoirs are some of the most popular and accessible fishing locations. Most are public waters with boat ramps, piers, and other facilities to accommodate fishermen. They usually have large, diverse fish populations and offer many opportunities for anglers.

What’s the difference between a lake and a reservoir? A lake is made by nature, while a reservoir is made by man. Natural lakes are plentiful in the northern US and Canada, in Florida, along major river systems (oxbows), and in the Western mountains.

Some natural lakes have rounded, shallow basins with soft bottoms. Others are very deep with irregular bottoms that includes reefs, islands, channels, points, and other structure. In many natural lakes, vegetation grows abundantly in shallow areas.

Natural lakes vary in age and fertility, which are measures of their capability to support fish populations. Some are relatively young and fertile, while others in the same area might be eons old and somewhat infertile.

Reservoirs exist throughout North America. These are impoundments formed by building a dam across a river and backing up the floodwaters. Hundreds of reservoirs have been built across the continent in the last 75 years or so to control floods, generate electric power, or serve farmers.

In most cases, the bottoms of reservoirs were once farmlands or forest. The water covers old fields, woodlands, creeks, roads, and other features that, when submerged, became fish structure.

Reservoirs are divided into two categories: upland and lowland (or mainstream). Upland reservoirs were built in highlands or canyons. They are typically deep and wind through steep terrain. Their coves and creek arms are irregular in shape.

In contrast, lowland reservoirs course through broad, flat valleys. These reservoirs are wider and shallower than upland reservoirs and typically have a long, fairly straight trunk with numerous smaller tributary bays.

The fertility of a reservoir and its capability to support a large fish population often depends on how fertile the area was before it was flooded.

Lowland reservoirs impounded over river bottoms are highly fertile, especially if trees were left standing when the area was flooded. As the trees decay, they release nutrients that support fish. Upland or canyon areas are less fertile, however. This is why upland reservoirs seldom support fish populations as dense as those in lowland reservoirs.

ANALYZING LARGE LAKES AND RESERVOIRS

It’s easy for a beginning angler to stand on the bank of a large lake or reservoir and feel overwhelmed. There’s so much water and so many places where fish can be. Start by adjusting your attitude. Since there’s more water there are more fish, so your odds of success are roughly the same as when fishing a pond or smaller lake.

That’s exactly how to approach this situation! It’s impossible to fish an entire large lake or reservoir. Choose one small part of it, approach it as you would a pond or small lake and use the same tactics. Whether they live in large or small waters, fish react the same to similar conditions in their environment. The basics still apply and the same tactics work in large waters and small. The main difference is that since they aren’t confined in small ponds, the fish have more freedom to roam and might migrate from one area to another depending on the season, food supply, and other factors. So, when deciding where to fish on a big lake, you have to pick the right small part.

How do you do this? Ask an employee at a nearby tackle store or bait shop where the fish are biting. Watch where other anglers are fishing. Try to determine if the fish are shallow or deep. Learn the depth where they’re biting. Use whatever information you can to get an overall picture, then key in on a location.

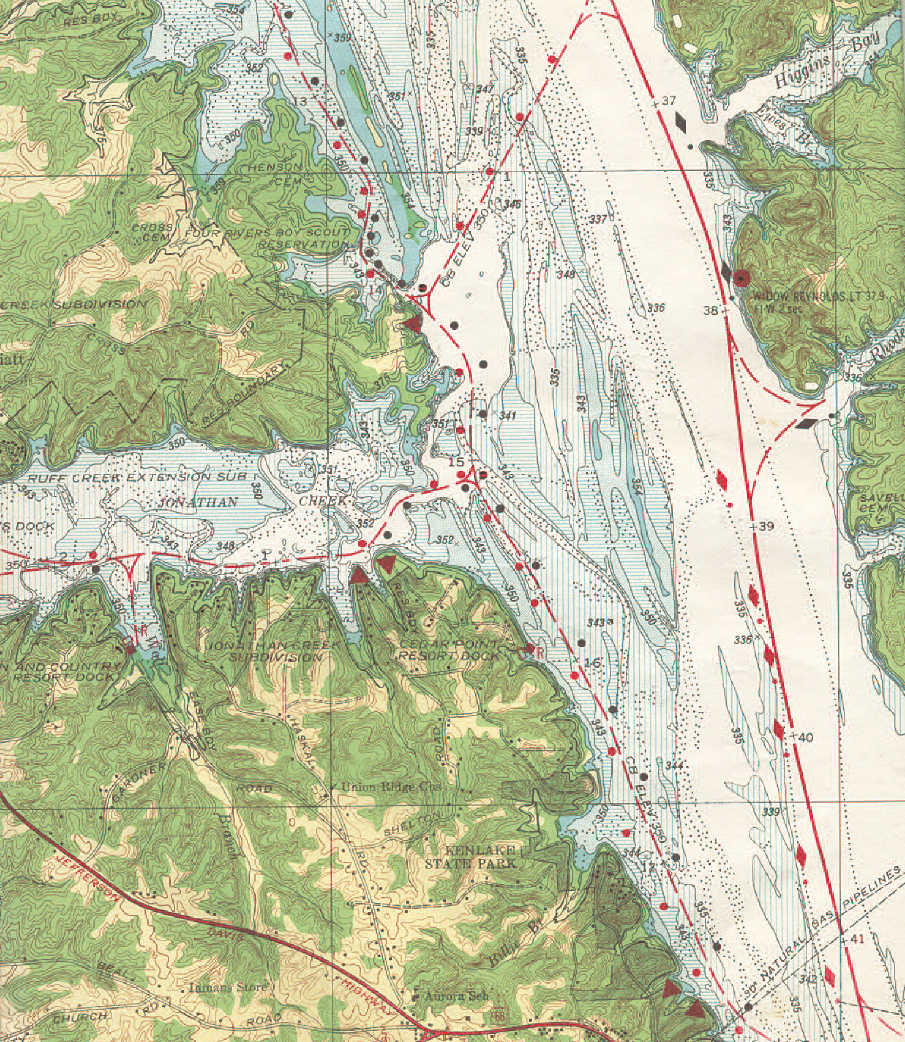

One aid that all anglers should learn to use is a topographic map. A “topo” map shows water depth and contour changes on the lake bottom. You can look at a topo map and find drop-offs, reefs, flats, creek channels, sunken islands, and other types of structure. Study what the different lines and features on the map mean and how fish might relate to such features. You can use the map to find the special areas where fish are likely to hang out. For instance, if a tackle store operator tells you crappies are spawning around the shoreline in shallow bays, you can locate shallow bays on your topo map, figure out the best way to get to them, and then go fishing for them.

In essence, topo maps are road maps to hot spots. Get one for the lake where you plan to fish and begin studying it.

Bluegills are favorite targets for many pond, lake, and reservoir fishermen. These fish are aggressive biters, hard fighters, and delicious to eat. Most bluegills are caught on live bait presented with a float rig around shady structure.

TECHNIQUES FOR FISHING LARGE LAKES AND RESERVOIRS

Again, large lakes and reservoirs support many different fish species. Some have only warm-water fish, some only cold-water fish, and others a mix of the two. When you go fishing, single out which species you’d like to catch and tailor your efforts to it.

Obviously, it’s impossible to discuss all places and methods for catching different types of fish from large lakes and reservoirs. Instead, the following represent the best, easiest big-water opportunities for beginning anglers.

SUNFISH

There’s little difference in fishing for sunfish in small ponds or in large lakes. Catching them is a simple matter of figuring out their locations and then getting a bait in front of them.

In spring, sunfish migrate into shallow areas to spawn, so look for them in bays and pockets along wind-protected shorelines. Before spawning, sunfish stay around brush, stumps, weeds, rocks, or other cover in two to eight feet of water. Then, as the water temperature climbs into the mid-60° F range, sunfish will move up into one to four feet of water and spawn in areas that have firm bottoms—gravel, sand, and clay.

Long poles or light-action spinning or spincast tackle will take these fish. Use fixed or slip-bobber rigs with wiggler worms, crickets, or a small hair jig tipped with a maggot for bait. You might even try a drop-shot rig to present natural baits in shallow, open water. When fishing around cover, keep your bait close in. When fishing a spawning area, drop or drag the bait right into the beds. (When fishing a visible sunfish spawning bed, try the outer edge first, then work your way to the center. This keeps fish that are hooked and struggling from spooking other fish off their beds.)

If it’s spawning time and no beds are visible, fish through likely areas and keep moving until you start getting bites. If sunfish are around, they’ll bite with little hesitation. Don’t stay very long in one place if you’re not getting any action there.

After spawning, sunfish head back to deeper water. Many fish will still hold around visible cover, but they prefer to be near deep water. Two classic examples are a weedline on the edge of a drop-off and a steep rocky bank.

Beside a bobber or drop-shot rig, another good way to catch sunfish is “jump-jigging,” which involves casting a  -ounce tube jig around weeds or rocks. Use a very light spinning outfit. Slowly reel the tube jig away from the cover and let the jig sink along the edge. Set the hook when you feel a bump or tug. This technique requires a boat, since you have to be over deep, open water casting into the weeds.

-ounce tube jig around weeds or rocks. Use a very light spinning outfit. Slowly reel the tube jig away from the cover and let the jig sink along the edge. Set the hook when you feel a bump or tug. This technique requires a boat, since you have to be over deep, open water casting into the weeds.

Docks, fishing piers, and bridges are good locations to catch sunfish after they’re through spawning. The water might be deep, but usually the fish will be up near the surface, holding under or close to the structures. Don’t stand on a dock, pier, or bridge and cast far out into the water. The fish are likely to be under your feet! Set your bobber so your bait hangs deeper than you can see, then keep your bait close to the structure.

Sometimes you have to try different depths to find where sunfish are holding. Change locations once in a while if you’re not getting bites. When you find the fish, work the area thoroughly. Sunfish swim in big schools after spawning and you can catch several in one place.

One special sunfish opportunity exists when insects are hatching. If you can find insects such as mayflies falling out of overhanging trees and swarming over the water, get ready for some hot action! Just thread one of the flies onto a small hook and drop it into this natural dining room. The sunfish will do the rest.

CRAPPIES

Crappies follow the same seasonal patterns as sunfish, except slightly earlier in the spring. When the weather starts warming, crappies head into bays and quiet coves to prepare to spawn. When the water begins to warm into the 60° F range, they fan out into the shallows. They spawn in or around brush, reeds, stumps, logs, roots, submerged timber, artificial fish attractors, or other cover. The right spawning depth depends on water color and sunlight penetration. In dingy water, crappies might spawn only a foot or two deep. But in clear water, they’ll spawn deeper, as far down as 12 feet. A good rule-of-thumb is first to try one to two feet below the depth at which your bait sinks out of your sight, then go deeper.

Minnows or small plastic jigs are good baits to try. Drop them next to or into potential spawning cover. You can do this from the bank, from a boat, or by wade-fishing the shallows. Lower the bait, wait thirty seconds, then move the bait to another spot. When fishing a brushpile, treetop or reed patch, try moving the bait around in the cover if it’s not too snaggy. If you catch a fish, put the bait back into the same spot to try for another. Stay on the move until you find some action. Fish straight up and down with a long crappie pole if you can, because you probably will snag your hook if you don’t.

After crappies spawn, they head back toward deeper water where they collect along underwater ledges, creek channel banks, sharp bottom contour breaks and other structure. This is where a topo map can help. If you’re fishing from shore, look for spots where deep water runs close to the bank.

Then go to these areas and look for treetops, brush, logs or other visible cover. Fish these spots with minnows or jigs. Or, if there is no visible cover, cast jigs randomly from shore. Wait until the jig sinks to the bottom before starting your retrieve. Then use a slow, steady retrieve to work the bait back up the bank. Set the hook when you feel any slight “thump” or when you see your line twitch.

Fish attractors also offer good fishing for crappies. Many fish and wildlife agencies sink brush or other cover into prime deep-water areas to concentrate fish. These attractors are then marked so anglers can find them. They might be out on a ledge or hump in a bay or around fishing piers or bridges. Dangle minnows or jigs around and into the middle of the cover. You’ll hang up once in a while, but you’ll also catch fish.

Fall might be the second-best time to catch crappie in large lakes and reservoirs. When the water starts cooling, these fish move back into shallow areas and hold around cover. Troll slowly through bays, cast jigs, or drop minnows into likely spots.

BASS

Spring, early summer, and fall are the three best times for beginning anglers to try for bass. This is when the fish are aggressive and shallow. When they’re deep, they might be tough even for guides and professional tournament fishermen to find.

Don’t let the size of a lake or reservoir intimidate you. Fish do the same things in big lakes that they do in small ponds. Bass, bluegills, and others often hang around rocky banks.

During these seasons, bass spend most of their time in or near cover such as brush, weeds, lily pads, flooded timber, logs, docks, stumps, rocks, riprap, and bridge pilings. By casting around such cover you’ve always got a chance for a strike.

In spring, bass spawn in shallow, wind-sheltered coves and shorelines, especially the ones with hard bottoms of sand, gravel, or clay. During the spawning season, try topwater minnows, spinnerbaits, and plastic lizards (weighted or unweighted) in these areas. Bass love to locate their nests next to features that offer protection from egg-eating sunfish.

After spawning, bass might stay shallow for several weeks, but slowly begin to migrate toward their summer haunts. The post-spawn period is a good time to fish points, which are ridges of land that run off into the water. Stand on the tip of a point and fan-cast crankbaits, plastic worms, or splashy topwater lures (poppers, propbaits) around the point. Pay special attention to any cover—brush, stumps, or weeds. If you don’t get a strike the first time through such a high-potential spot, cast back to it. Remember: sometimes you have to goad bass into striking.

Despite the warm water temperatures of summer, good bass fishing can still be found. Try fishing early and late in the day. If the water is very clear, it might be better to fish at night.

Some bass will feed in the shallows during low-light periods, then retreat to deeper water during midday. Other bass will hold along deeper areas or on the edges of shallow flats that border deeper water. Work your way along reefs, weedlines, channel drop-offs, edges of standing timber, sunken roadbeds, or around boat docks. Also, never pass up any isolated piece of cover such as a log, brushtop, or rockpile.

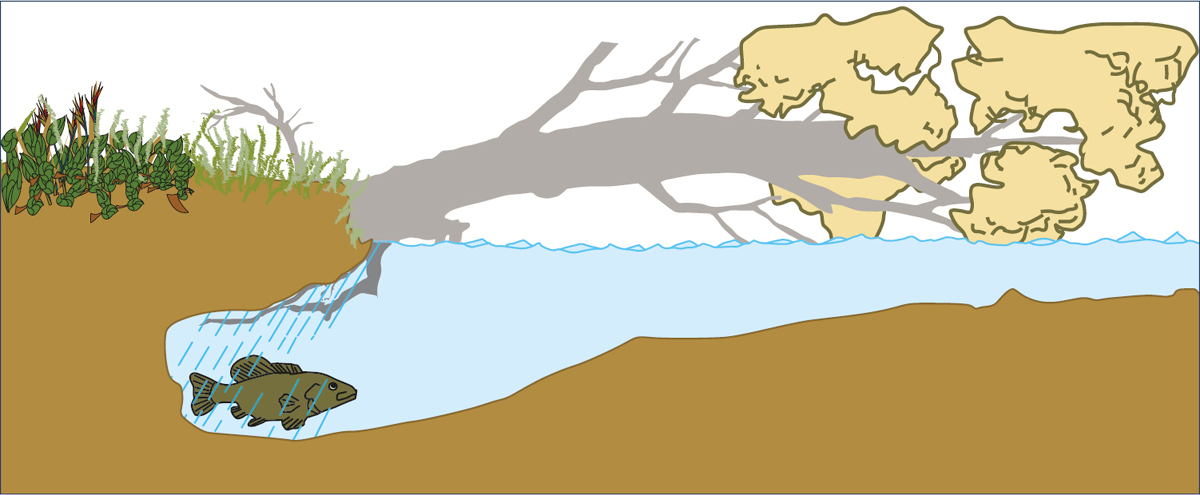

Big bass and catfish will sometimes lurk in hollows in a pond or river bank formed by erosion beneath fallen trees. Catfish favor these holes during spawning season.

Crankbaits and spinnerbaits are good lures for hot-weather bass, since you can fish them quickly and cover a lot of water. If you go through a likely area without getting a bite, work back through it with a Texas-rigged plastic worm. Move around and try to find where fish are concentrated. In the warm months, this will typically be where a food supply—usually minnows—is available. If you can find baitfish, bass will be somewhere close by.

In fall, concentrate on shorelines and shallows in coves. Water temperature cools off in these areas first, and draws in both baitfish and bass. Use the same tactics and baits you did in spring. Pay special attention to cover and the presence of minnows. If you see schools of minnows and bigger fish working around them, cast to these areas with a lipless crankbait in a shad color. In reservoirs, try the mouths, mid-sections, and backends of major bays where feeder creeks empty into the reservoir.

CATFISH/BULLHEADS

Big lakes can hold big catfish, and the best time to catch them is in late spring during the spawn. These fish move to the banks in search of holes and protected areas to lay their eggs.

Look for banks with big rock bluffs, riprap, etc. Catfish like to spawn in rocks. Fish around these areas with fixed- or slip-bobber rigs baited with gobs of wiggler worms or nightcrawlers. Set the float so the bait hangs just above the rocks. Use medium-strength line (10- to 20-pound test) and a steel hook (#1-3/0), since the possibility of hooking a big fish is good.

After they spawn, catfish head back to deepwater flats and channels. Normally they spend daylight hours deep, and move up at night to feed in nearby shallows. Find a point or other spot where the bank slopes off into deep water and fish here from late afternoon well into the night. Use a bottom rig baited with worms, cut bait, liver, commercial stink bait, or other popular catfish baits.

Another easy and productive method for taking catfish is called “jug fishing.” This method requires a boat and twenty-five or more plastic milk cartons or two-liter plastic bottles. Tie strong lines of four to six feet long onto the jug handles or around the bottle spouts. Tie a 2/0 steel hook on the end of the line, and add a split shot or a clincher sinker six inches up from the hook. Bait these lines with minnows, fish guts, or other catfish bait, and throw the jugs overboard on the upwind side of a lake or bay. The wind will float the jugs across the water and catfish will be drawn to the bait. When a jug starts bobbing on the surface, move the boat in and retrieve the fish.

US Geological Survey (USGS) topographical maps such as this one provide detailed information about the bottom features and shorelines of lakes, rivers, and impoundments.

Bullheads normally stay in warm bays that have silty or muddy bottoms. Like catfish, they stay deep during the day, but move up shallow and feed from late afternoon through the night.

The technique for catching bullheads is the same as for night-feeding catfish except you need lighter tackle. A spinning rod, 6-pound-test line, and a #3 hook make a good combination. A small split shot should be clamped on the line a foot up from the hook. Worms are good bait for bullheads.

WALLEYES

Walleyes are traditionally regarded as deep-water, bottom-hugging fish, but they will frequently feed in the shallows. The determining factor seems to be light penetration into the water. Walleyes don’t like bright sunlight. They might hold and feed in water no deeper than a couple of feet on overcast days, at night, when shallow areas are dingy or wave-swept, or when and where heavy weed growth provides shade.

Walleyes might be the ultimate structure fish. In deep areas, they hold along underwater humps, reefs, and drop-offs on hard, clean bottoms—especially those with rock or sand. They prefer water with good circulation and rarely concentrate in dead-water areas such as sheltered bays or coves. Walleyes will move in and out of feeding areas.

Walleyes spawn when water temperature climbs into the mid-40° F range, and this is a good time for beginning anglers to try for these fish. (Check local regulations; some states maintain a closed season on walleyes until after they spawn.)

Large rivers are among the most diverse of North America’s waters. Big rivers have a broad range of structure where fish can concentrate. Look for bass, after spawning, off points that lead into submerged feeder creek channels.

Look for shallows or shoal areas with gravel or rock bottoms that are exposed to the wind. Sloping points, islands, reefs, and rock piles close to shore are high-percentage spots. Fish for walleyes during lowlight periods—dawn, dusk, and at night.

Try a slip-bobber rig baited with a nightcrawler, leech, or live minnow in these areas. Adjust the bobber so the bait is suspended just above bottom. Sometimes casting shallow-running crankbaits or jigs tipped with live minnows in shallow areas will produce.

In early summer, walleyes can be caught along weedlines and mid-lake structure, both requiring a boat to fish them properly. When fishing weeds, cast a small jig ( or ⅛ ounce) tipped with a minnow right into the edge of the weeds, then swim it back out. Work slowly along the weedline. Pay special attention to sharp bends in the weedline or areas where the weeds thin out. (This technique will also produce bass, crappies, and pike, too.)

or ⅛ ounce) tipped with a minnow right into the edge of the weeds, then swim it back out. Work slowly along the weedline. Pay special attention to sharp bends in the weedline or areas where the weeds thin out. (This technique will also produce bass, crappies, and pike, too.)

Fishing deep structure can be a needle-in-a-haystack situation, so it’s best to stay on the move until you locate fish. If you see other boats clustered in a small area, they’re probably fishing productive structure. Go there and try drifting a nightcrawler on a slip-sinker rig. Move upwind of the other boats and let out enough line to hit bottom. Then engage your reel and drag the nightcrawler across bottom as you drift downwind.

A bite will feel like a light tap or bump. Release line immediately, and allow the fish to swim off with the bait. After about twenty seconds, reel up slack, feel for the fish, and set the hook.

This is the standard way to fish for lake or reservoir walleyes, but there are other good methods. Bottom-bouncing or drop-shot rigs trailing nightcrawlers or minnows can be productive along deep structure or submerged points. This is the same principle as using the slip-sinker rig. Let your line down to bottom, engage the reel, then drag the rig behind you as you drift or troll. A slip-bobber rig drifted across this structure is also a good bet.

As you fish deep structure, it’s a good idea to have a floating marker buoy handy. It should have several yards of line wrapped around it, with a weight tied to the end. If you get a bite, throw out the marker. The weight will cause the line to revolve off the buoy until it hits bottom. Then the buoy will stay in place and you can return to this spot after you’ve landed your fish. Walleyes are school fish, so there are probably more in the same area.

Trophy walleyes like this one can be caught from many of North America’s big lakes and reservoirs. These fish usually stay in deeper water and hug bottom structure. Sometimes, though, when feeding and water conditions are just right, they will move up into shallow vegetation or close to shore.

Big catfish can be caught from large rivers by anglers who learn the right techniques. Heavy tackle and natural bait are the standard presentation. Rivers can produce catfish as large as 100 pounds.

Beginners should try two other simple approaches for walleyes. First, find a rocky shoreline that slopes off quickly into deep water. Fish this from dusk to around midnight, either with live bait (slip-bobber rig) or by casting floating minnow lures. Second, cast into areas where strong winds are pushing waves onto the shore. The wave action muddies the water and walleyes move up to the banks to feed. Cast a jig and minnow here. Either walk the bank or wade the shallows, casting as you go. Pay special attention to the zone where muddy water meets clear water.

WHITE BASS

White bass are open-water fish. During spring spawning season they migrate up tributaries, though at other times they are usually in the main body of a lake or reservoir, schooled up to feed on small baitfish.

The best chance for beginners to catch white bass occurs when the fish are feeding on minnows at the surface. From early summer through fall, schools of white bass herd baitfish such as juvenile threadfin shad to the surface and then slash through them, feeding as they go. This typically happens in reservoirs when water is being pulled through the dam to generate electricity. Resulting current concentrates shad minnows where they are vulnerable to white bass. The baitfish try to escape by heading to the surface. When white bass are feeding “in the jumps,” almost any bright, fast-moving lure cast into this action will get a strike. The trick is to make long casts and stay a reasonable distance away, or else the baitfish and bass will dive.

White bass normally feed around sunken islands, reefs, flats near the main channel, or where submerged creeks empty into the main channel. Usually white bass will surface-feed for a short period, go back down to wait for another school of baitfish, then feed again. Hang around known surface feeding areas, and then cast fast and furiously when the fish appear.

If you’re fishing in the tailwaters of a dam, cast jigs and inline spinners upstream at an angle, then let the lure sink a bit and wind it in as it’s swept downstream. Keep your line tight and set the hook when you feel a tick or the line hops. This is a good way to catch white bass when you don’t have a boat.

NORTHERN PIKE

Pike fishing is best in spring, early summer, and fall when these fish are in quiet, weedy waters. They are normally aggressive, attacking any moving target. Look for pike in bays, sloughs, flats, and coves that have submerged weedbeds, logs, or other “hideout” cover. Pike like fairly shallow water of 3 to 10 feet deep.

Pike can get big and even small ones are tough fighters, so use fairly heavy tackle. (Spool up with 12- to 20-pound-test line.) They have sharp teeth that can easily cut monofilament or fluorocarbon line. For this reason, always rig with a short steel leader ahead of the lure or bait.

Find a place that gives you access to likely cover. Cast a large, brightly colored spoon next to or over the cover. You can cast from the bank or wade-fish, staying on the move to cover a lot of water. If you have a boat, motor to the upwind side of a shallow bay, shut down, and drift slowly downwind, casting a spoon to clumps of weeds and weed edges as you go. Retrieve the spoon steadily.

Otherwise, if pike don’t seem interested, pump the spoon up and down or jerk it erratically to get their attention. Other good lures for pike are large spinnerbaits, in-line spinners, large floating minnows, and wide-wobbling crankbaits.

Live-bait fishing is very effective. A large minnow suspended under a fixed-bobber rig is almost too much for pike to pass up. Clip a strong 1/0 or 2/0 hook to the end of a wire leader. Add a couple of split shot above the leader. Then add a large round bobber at a depth so the minnow will be up off bottom. Hook the minnow in the lips or back.

Cast this rig to the edges of weedlines and wood cover, or to pockets, points, or other structure. Then sit back and wait for a bite. When the bobber goes under, give the fish slack as it makes its first run with the bait. When the pike stops, reel in slack line, feel for the fish, and set the hook hard!

Yellow perch spawn in early spring when the water temperature climbs into the high 40° F range. They head into a lake’s feeder streams or shallows and during this migration they are extremely easy to catch.

A fixed- or slip-bobber rig is a good choice for perch. Use light line (four- to eight-pound test) and a #6 long-shank hook. Add a small split shot and bobber, bait with worms or live minnows, and drop the bait into shallow areas around cover. If you don’t get quick action, try somewhere else.

After the spawn, these fish return to main-lake areas. Smaller fish hold along weedlines, and jump-jigging is a good way to take them. (Refer to the “Sunfish” part of this section.) Larger perch hang close to the bottom and move onto reefs, ledges, and deep points. They might hold as deep as 40 feet.

Again, ask bait dealers about good deep-water perch spots. When you find one, fish it with a two-hook panfish rig or drop-shot rig. Bump your bait along bottom to attract strikes. If you catch a fish, unhook it quickly and drop a fresh bait right back into the same spot. Other perch will be drawn by the commotion.

HOW TO FISH SMALL STREAMS

Large lakes and reservoirs might be North America’s most popular fishing spots, and streams are surely the most overlooked. Fish-filled streams flow throughout the continent, yet most receive only a fraction of the fishing pressure that big lakes do. This means that stream fish are oftentimes easier to catch.

Streams can be divided into two classes: warm-water and cold-water. Warm-water streams harbor typical warm-water species: bass, sunfish, catfish, and white bass. They range in character from clear, fast-moving, whitewater-and-rocky streams to muddy, slow, deep streams.

Cold-water streams are normally found at higher altitudes or in valleys that drain highlands. Their primary gamefish are various trout species and perhaps smallmouth bass. Cold-water streams are usually clean and fairly shallow, and they have medium-to-fast current. Their bottoms are typically rock, gravel or sand. You can fish small streams by any of three methods: bank-fishing, wading, or floating.

When wade-fishing, you should work upstream, since you’ll continually stir up silt and debris. By fishing upcurrent, the sediment dislodged by your feet drifts behind you instead of in front of you, so the fish aren’t alerted to your presence.

Since they’re not subjected to much fishing pressure, stream fish like this smallmouth bass are more likely to bite a lure that’s pulled past where they’re holding.

Floating takes more planning and effort than wading, but it might also offer greater rewards. Floating can take you into fishing territory that’s seldom fished. I prefer a canoe when float-fishing, but kayaks, johnboats, and inflatables also work.

ANALYZING SMALL STREAMS

Current is the primary influence in the life of a stream. It’s like “liquid wind,” blowing food downstream and shaping the environment. Current determines where fish will find food and cover and is the reason why stream fishermen must always be aware of current and how it affects fish location.

Basically, fish react to current in one of three ways. One, they might be out in the fast water chasing food. Two, they might position themselves in an eddy right at the edge of current where they can watch for food without using much energy. And three, they will locate in quiet pools where current is slow. Different species vary in the amount of current they prefer and the places they hold.

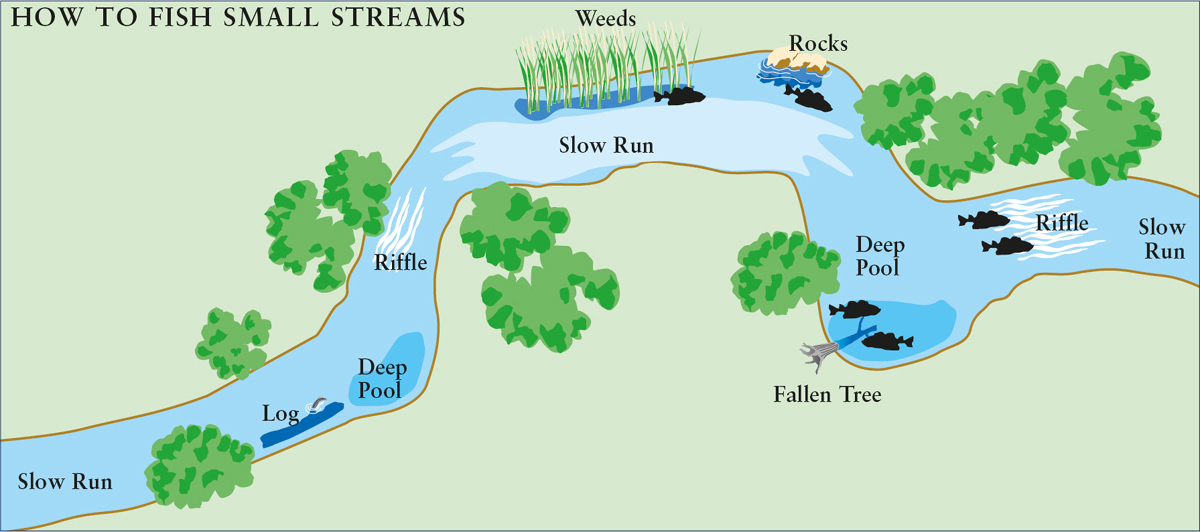

The typical stream is made up of a series of shallow riffles where current is swift, deep pools where current is slow, and medium-depth runs where current is intermediate. Riffles normally empty into deep pools. Runs usually drain the downstream ends of pools, and these runs lead to successive riffles. This progression repeats itself as a stream winds through the countryside.

Rocks, logs, stumps, and weeds form attractive stream cover. Many stream fish like to hide under or close to cover and then dart out and grab a crawfish or minnow.

Analyzing a stream is a matter of studying the current, depth, and cover. Remember that stream fish are consistent in the types of places where they hold. Catch one fish from behind a log, and chances are others will be hiding behind other logs.

TECHNIQUES FOR FISHING SMALL STREAMS

Information in the previous section addressed stream-fishing generalities. Now we get specific, learning exactly where to find different species and how to catch them.

Channel and flathead catfish are found in deep pools in warm-water streams. Catfish generally move deeper into pools as water temperatures rise toward midday.

In the process, understand that stream fish are more confined than lake or reservoir fish. In big waters, fish have a lot of room to move around, but in streams they have to be somewhere along one narrow waterway. Following are high-percentage methods for making fish bite the lures or baits you present to them.

BASS

Smallmouth bass are the predominant bass species found in many streams from the mid-South into Canada. They hold in eddies behind or under cover adjacent to fast current. Typical holding spots are behind a rock or a root wad that splits the current, beneath an undercut bank that lies beside a fast run, along edges (and especially ends) of weedbeds, or under a lip or rocky bar at the head of a pool where a riffle empties into it. I always pay special attention to holes gouged out where a stream makes a turn.

Smallmouth bass prefer shade to bright sunshine. Any place that offers quiet water and concealment with access to fast water is a potential smallmouth hot spot. Depth of such locations can vary. To fish these places, I recommend spinning or spincast tackle and 4- to 8-pound-test line. You’ll need something fairly light, because most stream smallmouth baits are small.

These fish feed mostly on crawfish, minnows, worms, mature insects, and insect larvae. The best artificial baits mimic these natural foods. Small crawfish crankbaits are deadly. So are floating minnows, in-line spinners, small jigs (hair or rubber skirt), and 4-inch plastic worms. My favorite lure for stream smallmouths is a brown tube lure rigged on a small jighead.

The key with all these baits is to work them close to cover. Cast your lure across or up the current, and work it right through the spot where you think bass might be holding. I like to swim a tube lure parallel to a log or deep-cut bank. I also like to crawl a crawfish crankbait or float a minnow lure over logs, rocks, or stumps. I’ll cast a jig into the head of a pool, allow it to sink, then hop it across bottom back through the heart of the pool. At times stream smallmouths will show a preference for one type of bait. In early spring, floating minnows or in-line spinners seem to work best. Later on, tube lures, small crankbaits, and jigs are better.

One of the secrets of catching stream smallmouths on artificial lures is accurate casting. You’ve got to get your lure close to the fish. When stream-fishing, wear camouflage or natural colors that won’t spook fish. Ease in from a downstream or cross-stream position of where the fish should be. Use the current and your rod tip to steer the bait into the strike zone.

One note on float-fishing streams: When I see a place where smallmouth should be I beach my canoe, get out, and walk around the spot. Then I ease in close from the downstream side and start casting. It’s easier to cast accurately while standing stationary instead of floating by a spot. Also, if I hook a fish, I can concentrate on playing it without worrying about controlling the canoe.

Smallmouths can be taken on several live baits, but crawfish and spring lizards are best. Use a slip-sinker rig (#1 hook) to work through high-percentage spots. Ease baits slowly along bottom and set the hook at the first hint of a pickup.

Many slower, deeper streams will hold largemouth or spotted bass instead of smallmouths. Fish for largemouth and spotted bass just as you would for smallmouths. Cast around cover. Work the ends and edges of pools, and stay alert for any sign of feeding activity. If you see a bass chasing minnows, cast to that area immediately!

CATFISH

Channel and flathead catfish are common in warm-water streams. They usually stay in deep, quiet holes. When feeding, they move into current areas and watch for food washing by.

Fish pools, heads of pools or around cover in runs with moderate current. Use a bottom rig or a fixed-bobber rig and live bait. The weight of these rigs depends on the water depth and current.

No matter if you’re fishing for bluegills, yellow perch, white bass, or catfish, fishing is a fun activity for everyone, whether you catch anything or not.

Bait with worms, crawfish, fish guts, live minnows, cut bait, or grasshoppers. Cast into the target zone, let the bait settle, and wait for a bite. Early and late in the day, or at night, concentrate on the heads of pools. During midday work the deeper pools and mid-depth runs. Be patient.

WHITE BASS

White bass spend most of their lives in large lakes, reservoirs and rivers. In spring, however, they also make spawning migrations up tributary creeks.

This migration occurs as the water temperature approaches 60° F. Huge schools of white bass swim upstream to spawn in shallow riffles. Before and after spawning, these fish hold in eddy pools beside swifter water. They particularly like quiet pockets behind logjams or along the stream bank.

During this spawning run, white bass are very aggressive, and will hit almost any bait pulled by them. In-line spinners (white, chartreuse), leadhead jigs with plastic trailers, and small crankbaits are top choices. Retrieve them at a medium-fast clip, and keep moving until you locate fish. When you find them, slow down and work potential spots thoroughly.

TROUT

Trout are found in cold-water streams throughout much of the US and Canada. Some are native to their home waters while others have been raised in hatcheries and stocked.

Fly fishing is a popular, effective way to take trout, but I don’t recommend it for beginners. I suggest sticking with light spinning tackle until you build your angling skills. Then you might “graduate” to fly fishing in the future.

Stream trout are very elusive fish. Get too close, make too much noise, wear bright clothes, or drop a lure right on their heads, and they’ll dart away. Instead, you have to stay back from feeding zones, remain quiet, wear drab-colored clothes, and cast beyond where you think the fish are.

Trout hold in areas similar to those smallmouths prefer. They like eddies adjacent to swift water where they can hide and then dart out to grab passing food. During insect hatches, trout also feed in open runs with moderate current.

Since most trout streams are clear, rig with four- to six-pound-test line. Then tie on a small in-line spinner, spoon, floating minnow, or crawfish crankbait. Cast these lures around rocks, logs, weeds, and other likely cover bordering swift water. The heads of pools can be especially good early in the morning and late in the afternoon. Also, trout love to feed after dark.

Streams, such as the one charted above, are some of the most plentiful—and least pressured—fishing spots in North America. This means that stream fish are naïve and easy to catch by anglers who know the basics of fishing these moving waters.

Natural baits are also effective for stream trout. Nightcrawlers, salmon eggs, grasshoppers, and minnows are good bets. Canned corn or small marshmallows will draw bites, especially from hatchery-raised trout. All these baits should be fished on the bottom with a very small hook (#12) and a split shot clamped 10 or 12 inches up the line.

Earlier in this chapter, I mentioned that fishing large lakes is like fishing small ponds in terms of basics. The same comparison can be made between small streams and large rivers. Big rivers are just little streams that have grown up. They are more complex, however, and contain a much broader range of fishing conditions.

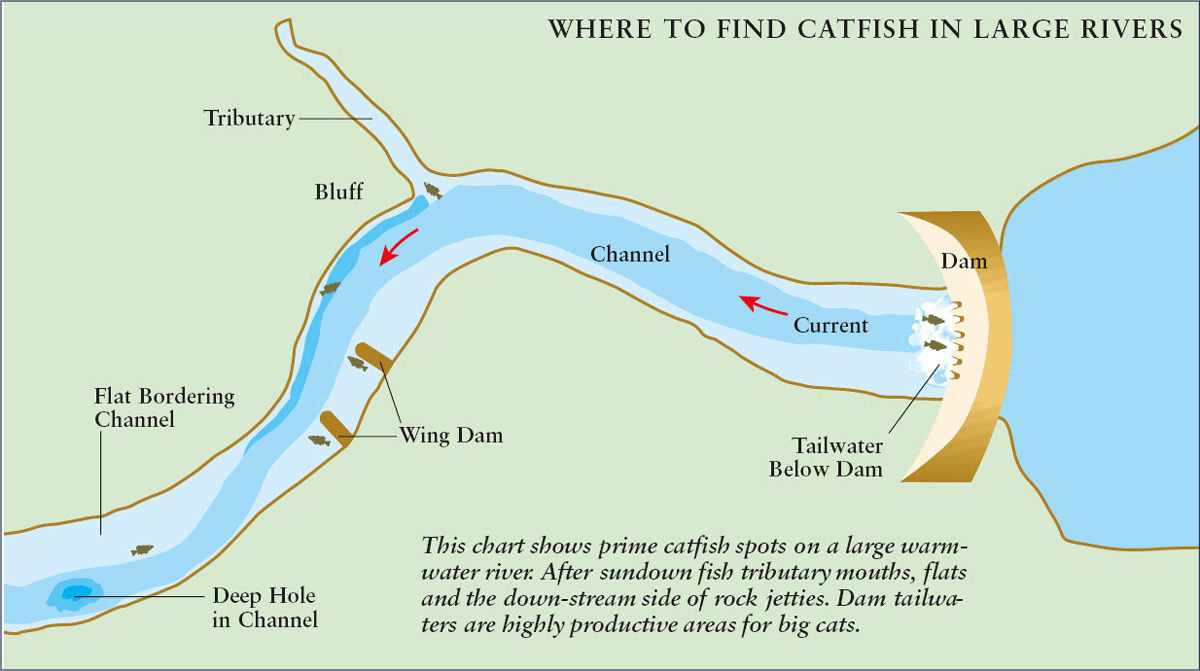

Large rivers are the most diverse of all waters. They contain a wide variety of fishing locations: eddies, bluffs, drop-offs, shallow flats, feeder streams, backwater sloughs, tailwaters, deep and shallow areas, and swift-flowing and calm water. Rivers typically hold several species of freshwater fish and consequently offer diverse fishing opportunities.

As with small streams, large rivers are divided into two types: warm water and cold water. Most rivers in North America are the warm, deep variety and support sunfish, bass, white bass, crappies, catfish, walleyes, etc. Many are dammed into “pools” to provide enough deep water for navigation.

In contrast, cold-water rivers are typically shallow and swift, flowing through mountainous areas and usually holding various trout species.

Large rivers are better suited for fishing from boats, though you can fish successfully from the bank, especially below dams or in backwater sloughs and oxbows. Whichever method and location you choose, large rivers are top-notch fisheries that beginners and veteran anglers can share and enjoy.

ANALYZING LARGE RIVERS

As in small streams, current determines fish locations in large rivers. Understanding current and being able to read rivers is essential to fishing them.

Current in large rivers might be more difficult to figure out. In small streams you can see the riffles and swift runs, but in large rivers the current might appear equal from bank to bank. Look closer, though, and you’ll see signs of current breaks. Points of islands, jetties, dam tailwaters, river sandbars, and mouths of tributaries are all areas where current is altered, and are prime spots to catch fish.

Most fish in large rivers usually hang in eddies or slack water. Sometimes they prefer still water bordering strong current where they can ambush baitfish washing by. At other times they seek still backwater sloughs.

Besides current, three other variables in large rivers are water level, color, and cover.

This stream angler is doing everything right. He’s casting up-current and retrieving his lure back through a deep hole with cover. There is a good chance he will get a strike from a bass or sunfish.

Rivers continuously rise and fall, depending on the amount of rainfall upstream. The level of the river is referred to as its “stage,” and this can have a direct bearing on fish locations. Many times when a river is rising and its waters are flooding surrounding lowlands, fish move into these freshly flooded areas to take advantage of a banquet of worms, crawfish, and other food.

COLOR

Large rivers vary greatly in water clarity. While the main channel area might be muddy, backwaters can be clear and more attractive to fish. Or, entire river systems could be muddy or clear depending on recent rains. Most fish species feed better in clear water.

COVER AND STRUCTURE

Fish react to cover in rivers the same way they do in other bodies of water. Species such as bass, crappies, and sunfish usually hold in or close to cover. It provides hiding places and a shield from current. Structure, or changes in bottom content or configuration, also provide holding places for fish.

When “reading” a large river, then, be aware of current (especially eddies), river stage, water color, cover and structure. You will encounter a broad range of combinations of these conditions that might confuse a beginning fisherman. But by following the advice in the remainder of this section, you can be assured that you’re on track and that you can, indeed, mine large rivers of their fishing riches.

TECHNIQUES FOR FISHING LARGE RIVERS

Many techniques for fishing large rivers are the same for ponds, lakes, and small streams. Therefore, the key to catching fish from rivers is finding them and then applying the fundamentals of tackle, bait, and fishing methods.

SUNFISH

Sunfish like quiet water, so look for them in eddies, backwater sloughs, feeder creeks, and other still areas. I’ve also caught sunfish from under bridges, in quarries, gravel pits, riprap banks, tailwaters, and other manmade spots. Remember that these fish won’t linger in strong current very long. Find quiet, deep pools with cover if you can.

Fish for them just as you would anywhere else. Use light tackle and small bobber rigs or drop-shot rigs. Bait with worms, crickets, or tiny tube jigs. Toss the bait right beside or into the cover and wait for a bite.

When fishing for sunfish many beginning anglers get frustrated because they get bites, but they can’t hook the fish. There are two possible solutions: (1) try a smaller hook; (2) wait longer before setting the hook. If your bobber is dancing on the surface, wait for it to go under completely before setting the hook.

Crappies also prefer quiet water. The best places to find river crappies are sloughs and slow-moving tributaries. Sometimes crappies hold in treetops, brush and other cover along river banks where the current is slow to moderate in speed.

The best times to catch crappies in rivers are spring and fall, and the easiest way to catch them is to move from one piece of cover to the next. Use a long panfish pole and a fixed-bobber rig to drop a minnow or small crappie jig beside or into fallen treetops, brush or vegetation. Be quiet as you move, and get only as close to cover as you must to reach it with your pole. Work each new object thoroughly, covering all sides. Don’t neglect areas where driftwood has collected.

Sometimes river crappies hide under floating debris.

A special time for crappies is when a river is rising and flooding adjacent sloughs and creeks. As the river comes up, crappies move into cover in these areas. If your timing is good, you can work these freshly flooded areas for huge catches.

BASS

River bass receive far less angling pressure than lake and reservoir bass, which means there’s some great fishing awaiting anglers who put forth the effort to find them.

Many cool-water streams in North America support abundant trout populations, both natives and stockers. The best way for beginners to catch these fish is casting tiny spinners or natural baits into holds below swift runs.

In spring, look for river bass in quiet waters where current won’t disturb their spawning beds. Cast to cover: brush, flooded timber, fallen trees, riprap banks, bridge pilings, etc. Spinnerbaits, buzzbaits, crankbaits, floating minnows, and jigs are good lure choices.

By early summer, most river bass will move out to the main channel. This is where the biggest concentrations of baitfish are found. Bass in current breaks can dart out and nail a hapless minnow passing by in the flow.

A broad variety of spots will hold river bass in summer and fall. These include mouths of feeder creeks, eddies on the sides and downstream ends of islands, wash-ins and rock piles, ends and sides (upcurrent and downcurrent) of rock jetties (wing dams) that extend from the bank toward the channel, bridge pilings and riprap causeways, any tree or log washed up on a flat or bank, wing walls, and breaks in riprap walls in tailwater areas. As in small streams, cast wherever the current is deflected by some object or feature in the river.

An increase in current generally activates bass in a river. Many rivers have power dams and when the dams begin generating, the current increases suddenly. This rings the dinner bell for fish! Bass that have been inactive will move to ambush stations and start feeding with abandon. One reason for this is because current bunches baitfish together and makes them easier targets.

Lure choices for fishing rivers run the gamut. Minnow-imitating crankbaits (diving and lipless) and buzzbaits are good in eddy pools, around bridge pilings, sand and mud bars, rock piles, and rock jetties.

Spinnerbaits are a top choice for working logs, treetops, brush, and weeds. Jigs tipped with a pork or plastic trailer will snare bass from tight spots close to cover. Try vibrating jigs too. Select lures for rivers as you would in lakes.

When a river floods adjacent lowlands, bass move into this fresh habitat to feed. Look for areas where the water is fairly clear and current is slack. Fish with spinnerbaits, topwaters, shallow crankbaits, or plastic worms. When the water starts dropping, bass will abandon these areas and move back to deeper water. When the water is receding, cast around the downstream end or mouths of oxbows, sloughs, side channels, and any feeder creeks or ditches that serve as travel routes.

Always be conscious of river bass “patterns.” If you find fish at the mouth of a feeder creek, chances are the next creek will also hold bass. The same is true of jetties, islands, rocks, etc.

CATFISH/BULLHEADS

Catfish and bullheads are plentiful in most large warm-water rivers. In the daytime, catfish stay in deep holes and channel edges, while bullheads prefer shallower backwaters. At night, both roam actively in search of food.

The best time to try for these fish is just after sundown. Fish for catfish along bluffs, tributary mouths, flats bordering the channel, or the downstream side of rock jetties. Try for bullheads in mud-bottom sloughs.

For catfish, use stout tackle and a bottom rig. Sinkers should be heavy enough to keep the bait anchored in current (one to three ounces). Hooks should be large and stout (1/0 to 3/0 steel). Live minnows, worms, cut bait, liver, or any traditional catfish bait will work. Cast the rig and allow it to sink to the bottom. Prop the rod in a forked stick jammed and sit back and wait for a bite.

Serious catfish anglers fish several rods at once. They stay in the same spot for several hours, waiting for the fish to feed.

A rock bank will offer red-hot catfishing during spawning time, especially if the rocks are out of direct current. Fish these spots with a fixed or slip-bobber rig, adjusting the float so the bait hangs just above the rocks.

River catfishing can be phenomenal in dam tailwaters—a collection point for fish. Tailwaters contain baitfish, current, dissolved oxygen, and bottom structure where fish can hold and feed.

The best way to fish a tailwater is to work eddies close to the swift water that pours through the dam. If you’re bank-fishing, use a bottom rig and cast into quiet waters behind wing walls, pilings, or the dam face. If the bottom is rough and you keep hanging up, switch to a slip-float rig adjusted so the bait hangs close to bottom, but not on it.

A better way to fish tailwaters is from a boat, floating along current breaks while bumping a two-hook panfish rig off the bottom. Use enough weight so your line hangs almost straight under the boat. Make long downstream drifts, up to a quarter-mile or more, before motoring back up to make another float. Don’t lay your rod down since big catfish strike hard, and can yank it overboard.

Another special catfishing opportunity occurs right after a heavy rain. Look for gullies, drains, or other spots where fresh water is rushing into the river. Catfish often move up below these inflows and feed furiously. In this case, use a fixed or slip-bobber rig and dangle a bait only two or three feet under the surface in the immediate vicinity of the inflow.

Fish bullheads in rivers the same as in large lakes and reservoirs. Light tackle, worms, and a bottom rig or bobber rig are hard to beat.

Since these fish are similar, and the techniques to catch them are the same, I will mention only walleyes, though the methods apply to both species.

River walleyes collect in fairly predictable places. They spend most of their time out of current, so look for them around islands, rock jetties, eddies below dams, etc. They usually hold near the edge of an eddy where they can watch for food.

The best river conditions for catching walleyes are when the water is low, stable, and relatively clear. Walleyes continue feeding when a river is rising, but might change locations in response to high-water conditions. When the river gets too muddy, or when the water starts dropping again, walleyes generally become inactive and hard to catch.

Tailwaters below dams are the best places for beginners to catch river walleyes. Some fish stay in tailwaters all year long, but the biggest concentrations occur during late fall, winter, and early spring. Walleyes might hold close to dam faces or behind wingwalls. They like to hang along rock ledges, gravel bars or other structure. But again, the key is reduced flow.

Boat-fishing is best for catching river walleyes. Use a cannonball-head jig tipped with a live minnow, matching the jig weight to the amount of current. In slack water, a 1⁄8-ounce jig is heavy enough to work most tailwater areas. Float or troll through likely walleye locations, vertically jigging off the bottom. Or anchor and cast into eddies, holes, and current breaks. Let the jig sink to the bottom and work it back with a lift/drop retrieve. At all times, work the bait slowly. Set the hook at the slightest bump.

A good technique for bank fishermen is casting crankbaits or jigs tipped with minnows along riprap banks in early spring. Walleyes spawn along the rocks downstream from dams when the water temperature climbs into the mid-40° F range. Cast parallel to banks, bump crankbaits off the rocks, or swim jigs just above them.

In summer and fall, look for walleyes farther downstream along riprap banks, jetties, gravel or rock bars, mouths of tributaries or sloughs, or deep eddy pools at the edge of current. Cast jigs or troll live-bait rigs through deeper areas, or cast crankbaits along rocky shallows.

WHITE BASS/STRIPERS/HYBRIDS

These three species of fish share similar river habitats and patterns. Since white bass are the most common, I will refer only to them. But be aware that where stripers and hybrids coexist with white bass, you might catch any of the three.

I mentioned the white bass spawning run in the section on how to fish small streams. These fish also spawn in tailwaters below dams on large rivers, and at this time fishing is easy and productive. White bass move into tailwaters and feed actively in early spring, when the water temperature rises into the low 50° F range.

One good way to catch them is to cast jigs from the bank. Use ⅛-ounce jigs in light current and ¼-ounce jigs in strong current. Dress the jigs with soft-plastic curly-tail trailers (white, yellow, chartreuse). Experiment by casting into both eddies and current, by allowing your jig to sink to different levels before starting the retrieve, and by varying your retrieve speed. Once you find a good pattern, stick with it. When you find tailwater white bass in early spring, you can catch them by the dozens!

After they spawn, white bass move back downstream. In summer and fall, they feed in large open areas of a river. If dams along the river generate electricity, feeding activity will be affected by the generation schedule. When the generators go on and the current increases, feeding begins. Some dams publish daily generation schedules, and smart anglers check them to time their trips to coincide with when the current is running. If you have a smartphone, it’s likely that you can find apps that provide dam generation schedules for the waters you want to fish.