CHAPTER 1

What You Need to Know About the AP Microeconomics Exam

IN THIS CHAPTER

Summary: Learn what topics are tested, how the test is scored, and basic test-taking information.

Key Ideas

Most colleges will award credit for a score of 4 or 5; some will award credit for a score of 3.

Most colleges will award credit for a score of 4 or 5; some will award credit for a score of 3.

Multiple-choice questions account for two-thirds of your final score.

Multiple-choice questions account for two-thirds of your final score.

Free-response questions account for one-third of your final score.

Free-response questions account for one-third of your final score.

Your composite score on the two test sections is converted to a score on the 1-to-5 scale.

Your composite score on the two test sections is converted to a score on the 1-to-5 scale.

Background Information

The AP Economics exams that you are taking were first offered by the College Board in 1989. Since then, the number of students taking the tests has grown rapidly. In 1989, 3,198 students took the Microeconomics exam, and by 2012 that number had increased to 62,351.

Some Frequently Asked Questions About the AP Economics Exams

Why Take the AP Economics Exams?

Although there might be some altruistic motivators, let’s face it: most of you take the AP Economics exams because you are seeking college credit. The majority of colleges and universities will accept a 4 or 5 as acceptable credit for their Principles of Microeconomics or Macroeconomics courses. A number of schools will even accept a 3 on an exam. This means you are one or two courses closer to graduation before you even begin working on the “freshman 15.” Even if you do not score high enough to earn college credit, the fact that you elected to enroll in AP courses tells admission committees that you are a high achiever and serious about your education. In recent years close to two-thirds of students have scored a 3 or higher on their AP Microeconomics exam.

What Is the Format of the Exams?

Table 1.1 Summarizes the format of the AP Macroeconomics and Microeconomics exams

Who Writes the AP Economics Exams?

Development of each AP exam is a multiyear effort that involves many education and testing professionals and students. At the heart of the effort is the AP Economics Development Committee, a group of college and high school economics teachers who are typically asked to serve for three years. The committee and other college professors create a large pool of multiple-choice questions. With the help of the testing experts at Educational Testing Service (ETS), these questions are then pretested with college students enrolled in Principles of Microeconomics and Macroeconomics for accuracy, appropriateness, clarity, and assurance that there is only one possible answer. The results of this pretesting allow each question to be categorized by degree of difficulty. Several more months of development and refinement later, Section I of the exam is ready to be administered.

The free-response essay questions that make up Section II go through a similar process of creation, modification, pretesting, and final refinement so that the questions cover the necessary areas of material and are at an appropriate level of difficulty and clarity. The committee also makes a great effort to construct a free-response exam that allows for clear and equitable grading by the AP readers.

At the conclusion of each AP reading and scoring of exams, the exam itself and the results are thoroughly evaluated by the committee and by ETS. In this way, the College Board can use the results to make suggestions for course development in high schools and to plan future exams.

What Topics Appear on the Exams?

The College Board, after consulting with teachers of economics, develops a curriculum that covers material that college professors expect to cover in their first-year classes. This curriculum has just undergone a revision and the new outline for the Microeconomics course is provided below. Based upon this outline of topics, the multiple-choice exams are written such that those topics are covered in proportion to their importance to the expected economics understanding of the student. If you find this confusing, think of it this way: Suppose that faculty consultants agree that market failure and the role of government topics are important to the microeconomics curriculum, maybe to the tune of 8 to 13 percent. So if about 10 percent of the curriculum in your AP Microeconomics course is devoted to these topics, you can expect roughly 10 percent of the multiple-choice exam to address these topics. This curriculum has just undergone a revision and the outline is provided below. Remember, this is just a guide and each year the exam differs slightly in the percentages.

Microeconomics

Unit 1: Basic Economic Concepts

This unit covers the foundations of microeconomic thinking, decision-making under constraints, and rational choice.

Topics:

Scarcity

Resource allocation and economic systems

The Production Possibilities Curve

Comparative advantage and gains from trade

Cost-benefit analysis

Marginal analysis and consumer choice

Exam Coverage

12%–15%

Unit 2: Supply and Demand

This unit provides the basics for understanding how markets work with an introduction to the supply and demand model.

Topics:

Demand

Supply

Elasticity

Market equilibrium, disequilibrium, and changes in equilibrium

The effects of government intervention in markets

International trade and public policy

Exam Coverage

20%–25%

Unit 3: Production, Cost, and the Perfect Competition Model

This unit describes the factors that drive the behavior of companies and the model of perfect competition.

Topics:

The production function

Short- and long-run production costs

Types of profit

Profit maximization

Perfect competition

Exam Coverage

22%–25%

Unit 4: Imperfect Competition

This unit explores how imperfectly competitive markets work and how game theory is used to predict behavior in oligopolies.

Topics:

Monopoly

Price discrimination

Monopolistic competition

Oligopoly and game theory

Exam Coverage

15%–22%

Unit 5: Factor Markets

This unit demonstrates how markets and marginal decision-making are used to describe the workings of factor markets.

Topics:

Introduction to factor markets

Changes in factor demand and factor supply

Profit-maximizing behavior in perfectly competitive factor markets

Monopsonistic markets

Exam Coverage

10%–13%

Unit 6: Market Failure and the Role of Government

This unit looks at the conditions under which markets may fail and the effects of government intervention in markets.

Topics:

Socially efficient and inefficient market outcomes

Externalities

Public and private goods

The effects of government intervention in different market structures

Income and wealth inequality

Exam Coverage

My Teacher (and the Syllabus) Keeps Talking About “Big Ideas” and “Skill Categories.” What Are These?

Most of the new curricular revision was a big-picture way of describing, and teaching, the key concepts in the AP Microeconomics course. While these are critical to your teacher’s preparation, and fundamentally guide the way in which she structures the course, as a student preparing for the exam you probably don’t need to have a deep understanding of what is happening behind the scenes. In other words, your course will be new and improved because of these revisions, but your fantastic teacher is doing the heavy lifting on making sure these are woven throughout the course.

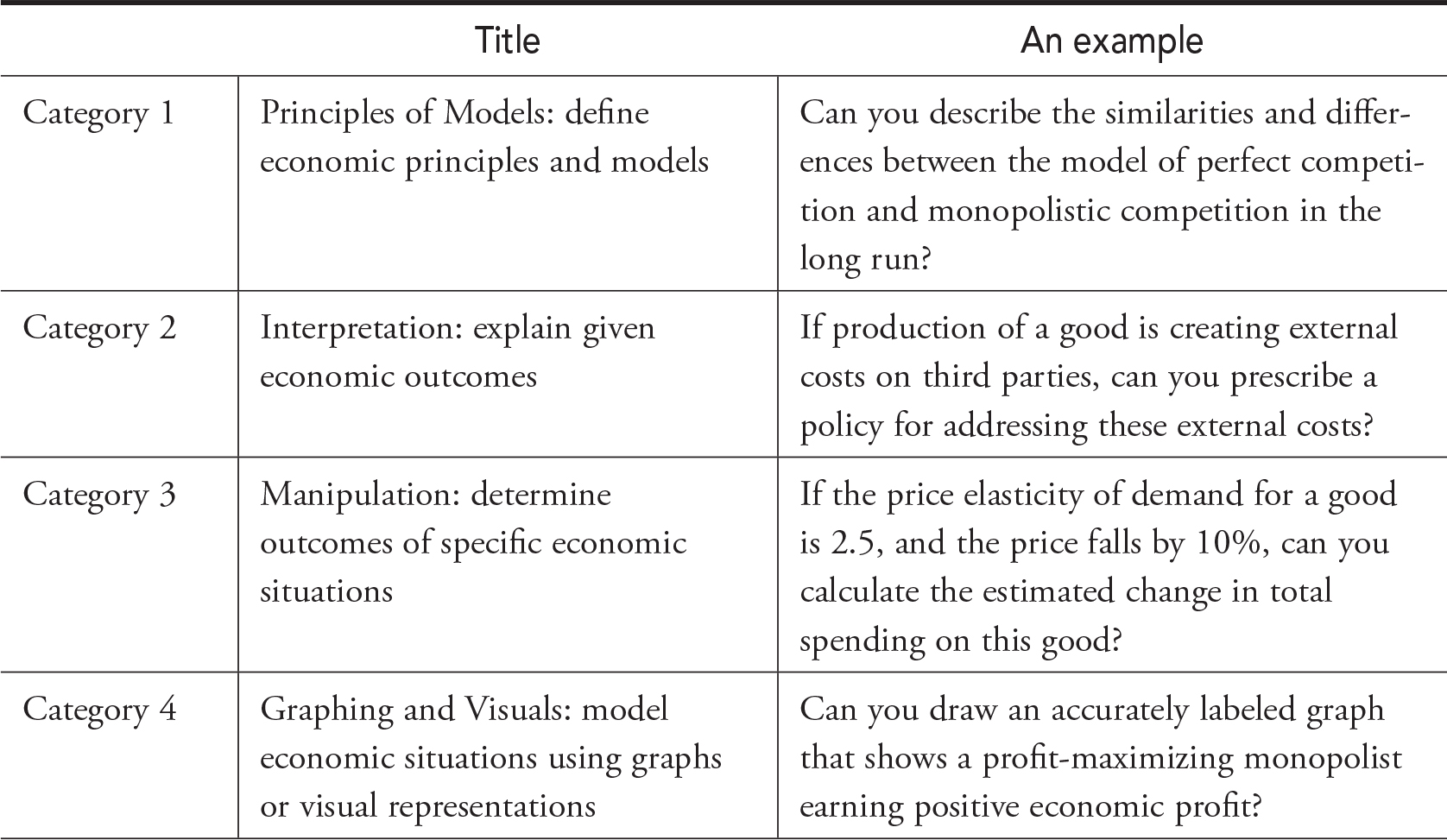

But in case you’re still curious, there are four skill categories that identify important skills that an AP Micro student should master throughout the course. The table below provides a brief summary.

There also four Big Ideas that will appear throughout your course. These are intended to reinforce common concepts that are key to a deep understanding of microeconomics. The four Big Ideas are:

1. Scarcity and Markets

2. Costs, Benefits, and Marginal Analysis

3. Production Choices and Behavior

4. Market Inefficiency and Public Policy

Much more detail on these Big Ideas and the Skill Categories can be found in the “AP Microeconomics Course and Exam Description” that is found at https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/pdf/ap-microeconomics-course-and-exam-description.pdf?course=ap-microeconomics.

Who Grades My AP Economics Exam?

From confidential sources, I can tell you that nearly 100,000 free-response essay booklets are dropped from a three-story building, and those that fall into a small cardboard box are given a 5, those that fall into a slightly larger box are given a 4, and so on until those that fall into a dumpster receive a 1. It’s really quite scientific!

Okay, that’s not really how it’s done. Instead, every June a group of economics teachers gather for a week to assign grades to your hard work. Each of these “Faculty Consultants,” or “Readers,” spends a day or so getting trained on one question and one question only. Because each reader becomes an expert on that question, and because each exam book is anonymous, this process provides a very consistent and unbiased scoring of that question. During a typical day of grading, a random sample of each reader’s scores is selected and cross-checked by other experienced “Table Leaders” to ensure that the consistency is maintained throughout the day and the week. Each reader’s scores on a given question are also statistically analyzed to make sure that he or she is not giving scores that are significantly higher or lower than the mean scores given by other readers of that question. All measures are taken to maintain consistency and fairness for your benefit.

Will My Exam Remain Anonymous?

Absolutely. Even if your high school teacher happens to randomly read your booklet, there is virtually no way he or she will know it is you. To the reader, each student is a number and to the computer, each student is a bar code.

What About That Permission Box on the Back?

The College Board uses some exams to help train high school teachers so that they can help the next generation of economics students to avoid common mistakes. If you check this box, you simply give permission to use your exam in this way. Even if you give permission, your anonymity is still maintained.

How Is My Multiple-Choice Exam Scored?

The multiple-choice section of each Economics exam is 60 questions and is worth two-thirds of your final score. Your answer sheet is run through the computer, which adds up your correct responses. The total scores on the multiple-choice sections are based on the number of questions answered correctly. The “guessing penalty” has been eliminated, and points are no longer deducted for incorrect answers. As always, no points are awarded for unanswered questions. The formula looks something like this:

Section I Raw Score = Nright

How Is My Free-Response Exam Scored?

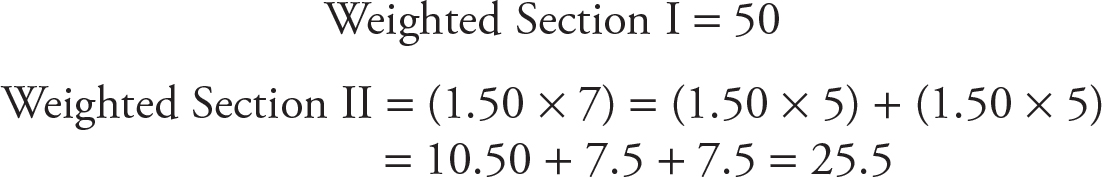

Your performance on the free-response section is worth one-third of your final score and consists of three questions. Another change to the exam is that the first question will always be scored out of 10 points, and the second and third questions will each be scored out of 5 points. Because the first question is longer than the other two, and therefore scored on a higher scale, it is given a different weight in the raw score. If you use the following sample formula as a rough guide, you’ll be able to gauge your approximate score on the practice questions.

Section II Raw Score = (1.50 × Score 1) + (1.50 × Score 2) + (1.50 × Score 3)

So How Is My Final Grade Determined and What Does It Mean?

With a total composite score of 90 points, and 60 being determined on Section I, the remaining 30 must be divided among the three essay questions in Section II. The total composite score is then a weighted sum of the multiple-choice and the free-response sections. In the end, when all of the numbers have been crunched, the Chief Faculty Consultant converts the range of composite scores to the 5-point scale of the AP grades.

Table 1.2 gives you a very rough example of a conversion, and as you complete the practice exam, you may use this to give yourself a hypothetical grade, keeping in mind that every year the conversion changes slightly to adjust for the difficulty of the questions from year to year. You should receive your grade in early July.

Table 1.2

Example:

In Section I, you receive 50 correct and 10 incorrect responses on the microeconomics practice exam. In Section II, your scores are 7/10, 5/5, and 5/5.

Composite Score = 50 + 24 = 75.5, which would be assigned a 5.

How Do I Register and How Much Does It Cost?

If you are enrolled in AP Microeconomics in your high school, your teacher is going to provide all of these details, but a quick summary wouldn’t hurt. After all, you do not have to enroll in the AP course to register for and complete the AP exam. When in doubt, the best source of information is the College Board’s website: www.collegeboard.com.

In 2019–2020 the fee for taking an exam is $94 for each exam. Students who demonstrate financial need may receive a partial refund to help offset the cost of testing. There are also several optional fees that can be paid if you want your scores rushed to you or if you wish to receive multiple grade reports.

The coordinator of the AP program at your school will inform you where and when you will take the exam. If you live in a small community, your exam might not be administered at your school, so be sure to get this information.

What If My School Only Offered AP Macroeconomics and Not AP Microeconomics, or Vice Versa?

Because of budget and personnel constraints, some high schools cannot offer both Microeconomics and Macroeconomics. The majority of these schools choose the macro side of the AP program, but some choose the micro side. This puts students at a significant disadvantage when they sit down for the Microeconomics exam without having taken the course. Likewise, Macroeconomics test takers have a rough time when they have not taken the Macroeconomics course. If you are in this situation, and you put in the necessary effort, I assure you that buying this book will give you more than a fighting chance on either exam even if your school did not offer that course.

What Should I Bring to the Exam?

On exam day, I suggest bringing the following items:

• Two sharpened number 2 pencils and an eraser that doesn’t leave smudges.

• Two black or blue-colored pens for the free-response section. Some students like to use two colors to make their graphs stand out for the reader.

• A watch so that you can monitor your time. You never know whether the exam room will have a clock on the wall. You cannot have a watch that accesses the Internet, and make sure you turn off any beep that goes off on the hour.

• Your school code.

• Your photo identification and social security number.

• Tissues.

• Your quiet confidence that you are prepared!

What Should I Not Bring to the Exam?

It’s probably a good idea to leave the following items at home:

• A calculator. It is not allowed for the Microeconomics or Macroeconomics exam. However, this does not mean that math will not be required. Questions involving simple computations have recently appeared on the exams, and later in the book I point out a few places where knowing a little math can earn you some points.

• A cell phone, smart watch, camera, tablet, laptop computer, or walkie-talkie.

• Books, a dictionary, study notes, flash cards, highlighting pens, correction fluid, a ruler, or any other office supplies.

• Portable music of any kind.

• Clothing with any economics on it.

• Panic or fear. It’s natural to be nervous, but you can comfort yourself that you have used this book well and that there is no room for fear on your exam.