Writing two coherent essays in an hour might seem daunting, but in this chapter, you will learn techniques of pre-construction and pre-structuring that will make the process easy. You will also learn how the essays are scored and the key factor the readers are told to look for. (Hint: It isn’t originality.)

The very first thing you will be asked to do on the GMAT is to write two essays using a word-processing program. You will have 30 minutes for each essay. You will not be given the essay topic in advance, nor will you be given a choice of topics. However, there is a complete list of all the possible writing assessment topics available for you to review on the GMAC website. Simply go to www.mba.com/mba/TaketheGMAT, select the link for the Analytical Writing Assessment section, and follow the directions to download a list of current topics. Oh, and just in case you are wondering, it’s free!

The business schools themselves asked for them. Recent studies have indicated that success in business (and in business school) actually depends more on verbal skills than has been traditionally thought.

The business schools have also had to contend with a huge increase in the number of applicants from overseas. Admissions officers at the business schools were finding that the application essays they received from outside the United States did not always accurately reflect the abilities of the students who were supposed to have written them. To put it more bluntly, some of these applicants were paying native English speakers to write their essays for them.

The GMAT Analytical Writing Assessment (AWA) is thus at least partly a check on the writing ability of foreign applicants who now make up more than one-third of all applicants to American business schools.

At the business schools’ request, all schools to which you apply now receive, in addition to your AWA score, a copy of the actual essays you wrote.

If you are a citizen of a non-English-speaking country, you can expect the schools to look quite closely at both the score you receive on the essays you write and the essays themselves. If you are a native English speaker with reasonable Verbal scores and English grades in college, then the AWA is not likely to be a crucial part of your package.

On the other hand, if your verbal skills are not adequately reflected by your grades in college, or in the other sections of the GMAT, then a strong performance on the AWA could be extremely helpful.

When you get your GMAT score back from GMAC, you will also receive a separate score for the AWA. Each essay is read by two readers, each of whom will assign your writing a grade from 0 to 6, in half-point increments (6 being the highest score possible). If the two scores are within a point of each other, they will be averaged. If there is more than a one-point spread, the essays will be read by a third reader, and scores will be adjusted to reflect the third scorer’s evaluation.

The essay readers use the “holistic” scoring method to grade essays; your writing will be judged not on small details but rather on its overall impact. The readers are supposed to ignore small errors of grammar and spelling. Considering that these readers are going to have to plow through more than 600,000 essays each year, this is probably just as well.

We’ll put this in the form of a multiple-choice question:

Your essays will be read by:

(A) captains of industry

(B) leading business school professors

(C) college TAs working part time

If you guessed C, you’re doing just fine. Each essay will be read by part-time employees of the testing company, mostly culled from graduate school programs.

The graders get two minutes, tops. They work in eight-hour marathon sessions (nine to five, with an hour off for lunch), and are each required to read 30 essays per hour. Obviously, these poor graders do not have time for an in-depth reading of your essay. They probably aren’t going to notice how carefully you thought out your ideas or how clever your analysis was. Under pressure to meet their quota, they are simply going to be giving it a fast skim. By the time your reader gets to your essay, she will probably have already seen more than a hundred essays—and no matter how ingenious you were in coming up with original ideas, she’s already seen them.

On the face of it, you might think it would be pretty difficult to impress these jaded readers, but it turns out that there are some very specific ways to persuade them of your superior writing skills.

In a 1982 internal study, two researchers from one of the big testing companies analyzed a group of essays written by actual test takers and the grades that those essays received. The most successful essays had one thing in common. Which of the following characteristics do you think it was?

The ETS researchers discovered that the essays that received the highest grades from ETS essay graders had one single factor in common: length.

To ace the AWA, you need to take one simple step: Write as much as you possibly can. Each essay should include at least four indented paragraphs.

The test makers have created a simple word-processing program to allow students to compose their essays on the screen.

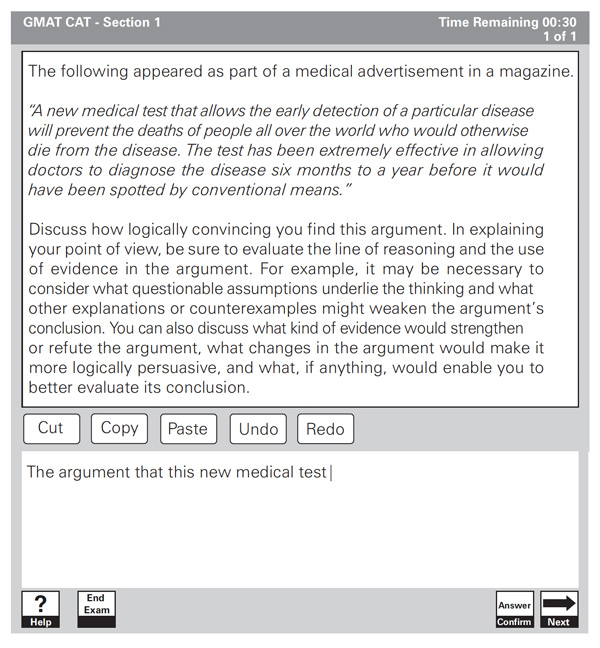

Here’s what your screen will look like during the essay portion of the test:

The question always appears at the top of your screen. Below it, in a box, will be your writing area (where you can see a partially completed sentence). When you click inside the box with your mouse, a winking cursor will appear, indicating that you can begin typing. The program supports the use of many of the normal computer keys, plus the following shortcuts:

Cut: Ctrl + X and Alt + T

Copy: Ctrl + C and Alt + C

Paste: Ctrl + V and Alt + A

Undo: Ctrl + Z and Alt + U

Redo: Ctrl + Y and Alt + R

You can also use the icons above the writing area to copy and paste words, sentences, or paragraphs and to undo and redo actions.

Obviously, this small box is not big enough to display your entire essay. However, you can see your entire essay by using the scroll bar, the up and down arrows, or the Page Up and Page Down keys.

Officially, no. Essay readers are supposed to ignore minor errors of spelling and grammar. However, the readers wouldn’t be human (so to speak) if they weren’t influenced favorably by an essay that had no obvious misspelled words or unwieldy constructions. Unfortunately, there is no spell-check function in the word-processing program.

There are two types of essay topics: Analysis of an Issue and Analysis of an Argument. Here’s an example of each:

Analysis of an Issue

“Some believe that violent television programs and music lyrics are the cause of increased violence and crime in our cities, and should be censored—but in fact, there is no correlation between violence in popular culture and violence in real life.”

Discuss the extent to which you agree or disagree with the opinion expressed above. Support your point of view with reasons and/or examples from your own experience, observations, or reading.

Analysis of an Argument

The following appeared as part of a medical advertisement in a magazine.

“A new medical test that allows the early detection of a particular disease will prevent the deaths of people all over the world who would otherwise die from the disease. The test has been extremely effective in allowing doctors to diagnose the disease six months to a year before it would have been spotted by conventional means.”

Discuss how logically convincing you find this argument. In explaining your point of view, be sure to evaluate the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument. For example, it may be necessary to consider what questionable assumptions underlie the thinking and what other explanations or counterexamples might weaken the argument’s conclusion. You can also discuss what kind of evidence would strengthen or refute the argument, what changes in the argument would make it more logically persuasive, and what, if anything, would enable you to better evaluate its conclusion.

You might think that there is really no way to prepare for the AWA (other than by practicing writing over a long period of time and by practicing your typing skills). After all, you won’t find out the topic of the essay they’ll ask you to write until you get there, and there is no way to plan your essays in advance.

However, it turns out there are some very specific ways to prepare for GMAT essays. Let’s take a look.

When a builder builds a house, the first thing he does is construct a frame. The frame supports the entire house. After the frame is completed, he can nail the walls and windows to the frame. We’re going to show you how to build the frame for the perfect GMAT essay. Of course, you won’t know the exact topic of the essay until you get there (just as the builder may not know what color his client is going to paint the living room), but you will have an all-purpose frame on which to construct a great essay no matter what the topic is.

We call this frame the template.

Just as a builder can construct the windows of a house in his workshop weeks before he arrives to install them, so can you pre-build certain elements of your essay.

We call this preconstruction.

In the rest of this chapter, we’ll show you how to prepare ahead of time to write essays on two topics you won’t see until they appear on your screen. Let’s begin with the Analysis of an Issue essay.

Writing the Analysis of an Issue essay requires the following steps:

Step 1:

Read the topic.

Step 2:

Decide the general position you are going to take—you need to take a stand on the issue.

Step 3:

Brainstorm. Come up with a bunch of supporting ideas or examples. It helps to write these down in your scratch booklet, or even to type them in the space where you will eventually write your essay. (If you type them, remember to erase them later.) These supporting statements are supposed to help persuade the reader that your main thesis is correct.

Step 4:

Look over your supporting ideas and throw out the weakest ones. There should be three to five left over.

Step 5:

Write the essay on screen, using all the preconstruction and template tools you’re going to learn in this chapter.

Step 6:

Read over the essay and do some editing. The GMAT readers will not take away points for spelling or grammatical mistakes, but you want your organization to be as well-reasoned as possible.

What the Readers Look For

The essay topic for the Analysis of an Issue will ask you to choose a side on an issue and develop coherent reasons or examples in defense of your position. You aren’t required to know any more about the subject than would any normal person. As far as the essay graders are concerned, it doesn’t even matter which side of the argument you take—as long as your essay is well written. So what constitutes a well-written essay?

The essay readers will look for four characteristics as they skim at the speed of light through your Analysis of an Issue essay. According to GMAC, “an outstanding essay

To put it more simply, they’ll look for good organization, good supporting examples for whatever position you’ve taken, and reasonable use of the English language. Let’s start with good organization and the easiest way to accomplish it—the template.

You will want to come up with your own template, but here is an elementary example of one, just to get you started:

Paragraph 1:

The issue of

is a controversial one. On the one hand,

On the other hand,

However, in the final analysis, I believe that

Paragraph 2:

One reason for my belief is that

Paragraph 3:

Another reason for my belief is

Paragraph 4:

Perhaps the best reason is

For all these reasons, I therefore believe that

Let’s try fitting the Analysis of an Issue topic we’ve already seen into this organizational structure.

Essay Topic 1:

“Some believe that violent television programs and music lyrics are the cause of increased violence and crime in our cities, and should be censored—but in fact, there is no correlation between violence in popular culture and violence in real life.”

Discuss the extent to which you agree or disagree with the opinion expressed above. Support your point of view with reasons and/or examples from your own experience, observations, or reading.

How would this topic fit into the first paragraph of our template? Take a look.

The issue of censorship of popular TV programs and music lyrics is a controversial one. On the one hand, increased crime and violence are causing a disintegration of the framework of our society. On the other hand, free speech is one of our most important freedoms, guaranteed by the constitution. However, in the final analysis, I believe that the dangers of subjecting impressionable young minds to questionable values makes self-censorship by the entertainment industry a viable alternative.

If we were writing the rest of this essay, we would start giving supporting examples and reasons for our position, but for now, let’s concentrate on the first paragraph. Could we have used this template to take the other side of the argument? Sure. Here’s how that would look:

The issue of censorship of popular TV programs and music lyrics is a controversial one. On the one hand, free speech is one of our most important freedoms, guaranteed by the constitution. On the other hand, increased crime and violence are causing a disintegration of the framework of our society. However, in the final analysis, I believe that the principle of free speech is too precious to allow censorship in any form.

Of course. Let’s try the same template with another topic.

Essay Topic 2:

“Critics who blame government bureaucracy for the increasing costs of our country’s infrastructure say our federal bureaucracy needs to be overhauled. However, these increasing costs are only to be expected in a growing state.”

Discuss the extent to which you agree or disagree with the opinion expressed above. Support your point of view with reasons and/or examples from your own experience, observations, or reading.

The issue of the overhaul of our federal bureaucracy is a controversial one. On the one hand, federal jobs employ a huge number of Americans, making any attempt to prune the federal payroll both difficult and painful. On the other hand, the percentage of our tax dollars spent simply on the upkeep of this huge bureaucratic juggernaut is rising at an alarming rate. However, in the final analysis, I believe that the political and financial price of bureaucratic reform would be too high.

As you can see, this template will fit practically any situation. To prove it, let’s try it out on one of the great philosophical arguments of our time.

Essay Topic X:

“Some people say that they drink light beer because it tastes great. However, the true reason people drink light beer is that it is less filling.”

Discuss the extent to which you agree or disagree with the opinion expressed above. Support your point of view with reasons and/or examples from your own experience, observations, or reading.

The issue of whether light beer is so popular because of its taste or because you can drink more of it without it filling you up is a controversial one. On the one hand, light beer does have a pleasingly mild taste. On the other hand, light beer also offers a sharply reduced number of calories. However, in the final analysis, I believe that light beer is so popular because of its great taste.

Read the following topic carefully. Decide which side of the argument you want to be on, and then fill in the blanks of the first paragraph of this template.

You may have noticed in the previous examples that to make this particular template work most effectively, the first “on the one hand” should introduce the argument that you are ultimately going to support. The “on the other hand” should be the argument you are going to disprove. The sentence beginning “however, in the final analysis” will return to the point of view that you believe in.

Essay Topic 3:

“Capping monetary awards in medical malpractice cases would result in lower costs for patients and a better health-care system.“

Discuss the extent to which you agree or disagree with the opinion expressed above. Support your point of view with reasons and/or examples from your own experience, observations, or reading.

The issue of

is a controversial one. On the one hand,

On the other hand,

However, in the final analysis, I believe that

If you were completing the entire essay now, you would write paragraphs giving support to your belief, but for right now, let’s concentrate on that first paragraph. Here’s one way Topic 3 could have gone:

The issue of capping malpractice awards is a controversial one. On the one hand, health-care costs are rising so quickly that drastic measures are needed to contain them. On the other hand, when an individual’s life is ruined as a result of a doctor’s negligence, that individual deserves fair recompense. However, in the final analysis, I believe that by capping the awards at a reasonable amount, we can both lower the cost of health care and protect the rights of victims of malpractice.

There are many ways to organize an Analysis of an Issue essay, and we’ll show you a few variations, but the important thing is that you bring with you to the exam a template you have practiced using and are comfortable with. Whatever the topic of the essay and whatever your personal mood that day, you don’t want to have to think for a second about how your essay will be organized. By deciding on a template in advance you will already have your organizational structure down before you get there.

That said, it’s important that you develop your own template, based on your own preferences and your own personality. Of course, yours may have some similarities to one of ours, but it should not mimic ours exactly—for one thing, because it’s pretty likely that when this edition of our book comes out, the folks who write the GMAT will read it, and they might take a dim view of anyone who blatantly copies one of our templates word-for-word.

Your organizational structure may vary in some ways, but it will always include the following elements:

Here are some alternate ways of organizing your essay:

Variation 1:

| 1st paragraph: | State both sides of the issue briefly before announcing what side you are on |

| 2nd paragraph: | Support your position |

| 3rd paragraph: | Further support |

| 4th paragraph: | Further support |

| 5th paragraph: | Conclusion |

Variation 2:

| 1st paragraph: | State your position |

| 2nd paragraph: | Acknowledge the arguments in favor of the other side |

| 3rd paragraph: | Rebut each of those arguments |

| 4th paragraph: | Conclusion |

Variation 3:

| 1st paragraph: | State the position you will eventually contradict, i.e., “Many people believe that …” |

| 2nd paragraph: | Contradict that first position, i.e., “However, I believe that… |

| 3rd paragraph: | Support your position |

| 4th paragraph: | Further support |

| 5th paragraph: | Conclusion |

We’ve shown you how templates and structure words can be used to help the organization of your essay. However, organization is not the only important item on the essay reader’s checklist. You will also be graded on how you support your main idea.

Learning to use the structural words we’ve just discussed is in fact a way to bring pre-built elements into the GMAT examination room with you. Along with a template, they will enable you to concentrate on your ideas without worrying about making up a structure from scratch. But what about the ideas themselves?

After reading the essay topic, you should take a couple of minutes to plan out your essay. First, decide which side of the issue you’re going to take. Then, begin brainstorming. Write down all the reasons and persuasive examples you can think of in support of your essay. Don’t stop to edit yourself; just let them flow out.

If you think better on the computer, you can write out your outline and supporting ideas directly on the screen. Just remember to erase them before the time for that essay is over.

Then go through what you’ve written to decide on the order in which you want to make your points. You may decide, on reflection, to skip several of your brainstorms—or you may have one or two new ones as you organize.

Here’s an example of what some brainstorming might produce in the way of support for Analysis of an Issue topic #1:

Main Idea: Censorship of television programs and popular music lyrics would be a mistake.

Support:

After you’ve finished brainstorming, look over your supporting ideas and throw out the weakest ones. In general, examples from your personal life are less compelling to readers than examples from history or current events. There should be three to five ideas left over. Plan the order in which you want to present these ideas. You should start with one of your strongest ideas.

The GMAT readers are looking for supporting ideas or examples that are, in their words, “insightful” and “persuasive.” What do they mean? Suppose you asked your friend about a movie she saw yesterday, and she said, “It was really cool.”

Well, you’d know that she liked it, and that’s good—but you wouldn’t know much about the movie. Was it a comedy? An action adventure? Did it make her cry?

The GMAT readers don’t want to know that the movie was cool. They want to know that you liked it because:

“It traced the development of two childhood friends as they grew up and grew apart.”

or because:

“It combined the physical comedy of The Three Stooges with the action adventure of Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

You want to make each example as precise and compelling as possible. After you have brainstormed a few supporting ideas, spend a couple of moments on each one, making it as specific as possible. For example, let’s say we are working on an essay supporting the idea that the United States should stay out of other countries’ affairs.

Too vague: When the United States sent troops to Vietnam, things didn’t work out too well. (How didn’t they work out? What were the results?)

More specific: Look at the result of the United States sending troops to Vietnam. After more than a decade of fighting in support of a dubious political regime, American casualties numbered in the tens of thousands, and we may never know how many Vietnamese lost their lives as well.

You’ve picked a position, you’ve brainstormed, you’ve utilized a template and some structure words; brainstorming should have taken about five minutes. Now it’s time to write your essay. Start typing, indenting each of the four or five paragraphs. Use all the tools you’ve learned in this chapter. Remember to keep an eye on the time. You have only 30 minutes to complete the first essay.

If you have a minute at the end, read over your essay and do any editing that’s necessary.

Then, during the next 30 minutes, you’ll turn to the second essay topic.

Q: What are the most

important aspects of

writing a good Analysis

of an Issue essay?

You’ll be able to use all the skills we’ve just been discussing on the second type of essay as well—with one major change. The Analysis of an Argument essay must initially be approached just like a logical argument in the Critical Reasoning section.

An Analysis of an Argument topic requires the following steps:

Step 1:

Read the topic and separate out the conclusion from the premises.

Step 2:

Because they’re asking you to critique (i.e., weaken) the argument, concentrate on identifying its assumptions.

Brainstorm as many different assumptions as you can think of. Again, it helps to write or type these out.

Step 3:

Look at the premises. Do they actually help to prove the conclusion?

Step 4:

Choose a template that allows you to attack the assumptions and premises in an organized way.

Step 5:

At the end of the essay, take a moment to illustrate how these same assumptions could be used to make the argument more compelling.

Step 6:

Read over the essay and do some editing.

An Analysis of an Argument topic presents you with an argument. Your job is to critique the argument’s line of reasoning and the evidence supporting it and suggest ways in which the argument could be strengthened. Again, you aren’t required to know more about the subject than would any normal person—but you must be able to spot logical weaknesses. This should start to remind you of Critical Reasoning.

The essay readers will look for four things as they skim through your Analysis of an Argument essay at the speed of light. According to GMAC, “an outstanding argument essay…

To put it more simply, the readers will look for all the same things they looked for in the Analysis of an Issue essay, plus one extra ingredient: a cursory knowledge of the rules of logic.

A: Write at least four or

five well-organized

paragraphs (an introduction

that explains

the side you are taking,

a middle with your

points and

examples,

and a conclusion to

sum up your position).

In any GMAT argument, the first thing to do is to separate the conclusion from the premises.

Let’s see how this works with an actual essay topic. Check out the Analysis of an Argument topic you saw before.

Topic:

The following appeared as part of a medical advertisement in a magazine.

“A new medical test that allows the early detection of a particular disease will prevent the deaths of people all over the world who would otherwise die from the disease. The test has been extremely effective in allowing doctors to diagnose the disease six months to a year before it would have been spotted by conventional means.”

Discuss how logically convincing you find this argument. In explaining your point of view, be sure to evaluate the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument. For example, it may be necessary to consider what questionable assumptions underlie the thinking and what other explanations or counterexamples might weaken the argument’s conclusion. You can also discuss what kind of evidence would strengthen or refute the argument, what changes in the argument would make it more logically persuasive, and what, if anything, would enable you to better evaluate its conclusion.

The conclusion in this argument comes in the first line:

A new medical test that allows the early detection of a particular disease will prevent the deaths of people all over the world who would otherwise die from that disease.

The premises are the evidence in support of this conclusion.

The test has been extremely effective in allowing doctors to diagnose the disease six months to a year before it would have been spotted by conventional means.

The assumptions are the unspoken premises of the argument—without which the argument would fall apart. Remember that assumptions are often causal, analogical, or statistical. What are some assumptions of this argument? Let’s brainstorm.

You can often find assumptions by looking for a gap in the reasoning:

Medical test → early detection: According to the conclusion, the medical test leads to the early detection of the disease. There doesn’t seem to be a gap here.

Early detection → nonfatal: In turn, the early detection of the disease allows patients to survive the disease. Well, hold on a minute. Is this necessarily true? Let’s brainstorm:

Okay, we’ve uncovered some assumptions. Now, the essay graders also want to know what we thought of the argument’s “use of evidence.” In other words, did the premises help to prove the conclusion? Well, in fact, no, they didn’t. The premise here (the fact that the test can spot the disease six months to a year earlier than conventional tests) does not really help to prove the conclusion that the test will save lives.

We’re ready to put this into a ready-made template. In any Analysis of an Argument essay, the template structure will be pretty straightforward: You’re simply going to reiterate the argument, attack the argument in three different ways (one to a paragraph), summarize what you’ve said, and mention how the argument could be strengthened. From an organizational standpoint, this is pretty easy. Try to minimize your use of the word “I.” Your opinion is not really the point in an Analysis of an Argument essay.

Of course, you will want to develop your own template for the Analysis of an Argument essay, but to get you started, here’s one possible structure:

The argument that (restatement of the conclusion) is not entirely logically convincing, because it ignores certain crucial assumptions.

First, the argument assumes that

Second, the argument never addresses

Finally, the argument omits

Thus, the argument is not completely sound. The evidence in support of the conclusion

Ultimately, the argument might have been strengthened by

Here’s how the assumptions we came up with for this argument would have fit into the template:

The argument that the new medical test will prevent deaths that would have occurred in the past is not entirely logically persuasive, because it ignores certain crucial assumptions.

First, the argument assumes that early detection of the disease will lead to a reduced mortality rate. There are a number of reasons this might not be true. For example, the disease might be incurable (etc.).

Second, the argument never addresses the point that the existence of this new test, even if totally effective, is not the same as the widespread use of the test (etc.).

Finally, even supposing the ability of early detection to save lives and the widespread use of the test, the argument still depends on the doctors’ correct interpretation of the test and the patients’ willingness to undergo treatment. (etc.)

Thus, the argument is not completely sound. The evidence in support of the conclusion (further information about the test itself) does little to prove the conclusion—that the test will save lives—because it does not address the assumptions already raised. Ultimately, the argument might have been strengthened by making it plain that the disease responds to early treatment, that the test will be widely available around the world, and that doctors and patients will make proper use of the test.

Q: What are the most

important aspects of

writing a good Analysis

of an Argument essay?

Your organizational structure may vary in some ways, but it will always include the following elements:

Variation 1:

| 1st paragraph: | Restate the argument. |

| 2nd paragraph: | Discuss the link (or lack of one) between the conclusion and the evidence presented in support of it. |

| 3rd paragraph: | Show three holes in the reasoning of the argument. |

| 4th paragraph: | Show how each of the three holes could be plugged up by explicitly stating the missing assumptions. |

Variation 2:

| 1st paragraph: | Restate the argument and say it has three flaws. |

| 2nd paragraph: | Point out a flaw and show how it could be plugged up by explicitly stating the missing assumption. |

| 3rd paragraph: | Point out a second flaw and show how it could be plugged up by explicitly stating the missing assumption. |

| 4th paragraph: | Point out a third flaw and show how it could be plugged up by explicitly stating the missing assumption. |

| 5th paragraph: | Summarize and conclude that because of these three flaws, the argument is weak. |

You’ve separated the conclusion from the premises. You’ve brainstormed for the gaps that weaken the argument. You’ve noted how the premises support (or don’t support) the conclusion. Now it’s time to write your essay. Start typing, indenting each of the four or five paragraphs. Use all the tools you’ve learned in this chapter. Remember to keep an eye on the time.

Again, if you have a minute at the end, read over your essay and do any editing that’s necessary.

In both essays, the readers will look for evidence of your facility with standard written English. This is where preconstruction comes in. It’s amazing how a little elementary preparation can enhance an essay. We’ll look at three tricks that almost instantly improve the appearance of a person’s writing:

In Chapter 16, we brought up a problem that most students encounter when they get to the Reading Comprehension section: There isn’t enough time to read the passages carefully and answer all the questions. To get around this problem, we showed you some ways to spot the overall organization of a dense reading passage in order to understand the main idea and to find specific points quickly.

When you think about it, the essay readers face almost the identical problem: They have less than two minutes to read your essay and figure out if it’s any good. There’s no time to appreciate the finer points of your argument. All they want to know is whether it’s well organized and reasonably lucid—and to find out, they will look for the same structural clues you have learned to look for in the reading comprehension passages. Let’s mention them again:

• If you have three points to make in a paragraph, it helps to point this out ahead of time:

There are three reasons why I believe that the Grand Canyon should be strip-mined. First … Second … Third…

• If you want to clue the reader in to the fact that you are about to support the main idea with examples or illustrations, the following words are useful:

for example

to illustrate

for instance

because

• To add yet another example or argument in support of your main idea, you can use one of the following words to indicate your intention:

furthermore

in addition

similarly

just as

also

moreover

• To indicate that the idea you’re about to bring up is important, special, or surprising in some way, you can use one of these words:

surely

truly

undoubtedly

clearly

certainly

indeed

as a matter of fact

in fact

most important

• To signal that you’re about to reach a conclusion, you might use one of these words:

therefore

in summary

consequently

hence

in conclusion

in short

A: Write at least four or

five well-organized

paragraphs (an intro-

duction, in which you

state that you will

analyze the reason-

ing of the topic;

a

middle, to pick apart

the argument by

exposing assumptions;

and a conclusion in

which you state how

the argument could

be strengthened and

sum up your

position).

Remember, this essay

uses the same skills

and approach you

developed for the

Critical Reasoning

section of the test.

You may have noticed that much of the structure we have discussed thus far has involved contrasting viewpoints. Nothing will give your writing the appearance of depth faster than learning to use this technique. The idea is to set up your main idea by first introducing its opposite.

It is a favorite ploy of incoming presidents to blame the federal bureaucracy for the high cost of government, but I believe that bureaucratic waste is only a small part of the problem.

You may have noticed that this sentence contained a “trigger word.” In this case, the trigger word but tells us that what was expressed in the first half of the sentence is going to be contradicted in the second half. We discussed trigger words in the Reading Comprehension chapter of this book. Here they are again:

| but | however |

| on the contrary | although |

| yet | while |

| despite | in spite of |

| rather | nevertheless |

| instead |

By using these words, you can instantly give your writing the appearance of depth.

Example:

Main thought: I believe that television programs should be censored.

While many people believe in the sanctity of free speech, I believe that television programs should be censored.

Most people believe in the sanctity of free speech, but I believe that television programs should be censored.

In addition to trigger words, here are a few other words or phrases you can use to introduce the view you are eventually going to decide against:

| admittedly | true |

| certainly | granted |

| obviously | of course |

| undoubtedly | to be sure |

| one cannot deny that | it could be argued that |

Also, don’t forget about yin-yang words, which can be used to point directly to two contrasting ideas:

on the one hand/on the other hand

the traditional view/the new view

Trigger words can be used to signal the opposing viewpoints of entire paragraphs. Suppose you saw an essay that began:

Many people believe that youth is wasted on the young. They point out that young people never seem to enjoy, or even think about, the great gifts they have been given but will not always have: Physical dexterity, good hearing, good vision. However…

What do you think is going to happen in the second paragraph? That’s right, the author is now going to disagree with the many people of the first paragraph.

Setting up one paragraph in opposition to another lets the reader know what’s going on right away. The organization of the essay is immediately evident.

Many people think good writing is a mysterious talent that you either have or don’t have, like good rhythm. In fact, good writing has a kind of rhythm to it, but there is nothing mysterious about it. Good writing is a matter of mixing up the different kinds of raw materials that you have available to you—phrases, dependent and independent clauses—to build sentences that don’t all sound the same.

The graders won’t have time to savor your essay, but they will look for variety in your writing. Here’s an example of a passage in which all the sentences sound alike:

Movies cost too much. Everyone agrees about that. Studios need to cut costs. No one is sure exactly how to do it. I have two simple solutions. They can cut costs by paying stars less. They can also cut costs by reducing overhead.

Why do all the sentences sound alike? Well, for one thing, they are all about the same length. For another thing, the sentences are all made up of independent clauses with the same exact setup: Subject, verb, and sometimes object. There are no dependent clauses, almost no phrases, no structure words, and, frankly, no variety at all.

Now let’s take a look at the same passage, with some minor modifications.

Everyone agrees that movies cost too much. Clearly, studios need to cut costs, but no one is sure exactly how to do it. I have two simple solutions: They can cut costs by paying stars less and by reducing overhead.

In this version of the passage, we’ve combined some clauses and used conjunctions. This helped to add variety in both sentence structure and sentence length. We also threw in a few structure words as well. As you can see, simple techniques like these can make your writing appear stronger and more polished.

In any kind of writing, it pays to remember who your audience will be. In this case, the essays are going to be graded by college teaching assistants. They wouldn’t be TAs if they didn’t have a soft spot in their hearts for someone who can refer to a well-known, nonfiction book or a famous work of literature.

What book should you pick? Obviously it should be a book that you have actually read and liked. We do not advise picking a book if you’ve only seen the movie. Hollywood has a habit of changing the endings.

You might think that it would be impossible to pick a book to use as an example for an essay before you even know the topic of the essay, but it’s actually pretty easy. Just to give you an idea of how it’s done, let’s pick a famous work of literature that most people have read at some point in their lives: Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Now let’s take each of the topics we’ve used in this chapter and see how we can work in a reference to Hamlet.

Essay Topic 1:

“Should television and song lyrics be censored in order to curb increasing crime and violence?”

…Where would such censorship stop? In an attempt to prevent teen suicide, would an after-school version of Shakespeare’s Hamlet be changed so that the soliloquy read, “To be, or … whatever”?

“Is government bureaucracy to blame for the increased cost of government?”

If you were to compare the United States government to Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the poor bureaucrats would represent the forgotten and insignificant Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, not the scheming pretenders to the throne.

Essay Topic 3:

“Should the maximum amount of a medical malpractice lawsuit be capped in the interest of lowering the cost of health care?”

Malpractice awards are getting out of hand. If Shakespeare’s era was reportedly the most litigious age in history, surely ours must come a close second. If he were writing today, you have the feeling Hamlet might have said, “Alas, poor Yorick, he should have gotten a better malpractice lawyer.”

You get the idea. Because your essays may be read by the admissions officers at the schools to which you apply, you might think it would be better to cite a book by a well-regarded economist or business guru rather than that of a playwright or novelist. As long as your example feels like an organic addition to your essay, it won’t matter too much who you cite. But you may find that these economic references are harder to work into your essay—and they will almost certainly go over the heads of the essay graders.

Few people are rejected by a business school based on their writing score, so don’t bother feeling intimidated. Think of it this way: The essays represent an opportunity if your Verbal score is low, or if English is your second language. For the rest of you, the essays are as good a way as any to warm up (and wake up) before the sections that count.

After you finish your essays, take advantage of the optional five-minute break to clear your head, and get ready for the multiple-choice questions to come.

Step 1:

Read the topic.

Step 2:

Decide the general position you are going to take on the issue.

Brainstorm. Come up with a bunch of supporting ideas or examples and write them down. These supporting statements are supposed to help convince the reader that your main thesis is correct.

Step 4:

Look over your supporting ideas and throw out the weakest ones. There should be three to five left over.

Step 5:

Write the essay, using all the preconstruction and template tools you learned in this chapter.

Step 6:

Read over the essay and edit your work.

Step 1:

Read the topic and separate out the conclusion from the premises.

Step 2:

Because they ask you to critique (i.e., weaken) the argument, concentrate on identifying its assumptions. Brainstorm as many different assumptions as you can think of and write them down.

Step 3:

Look at the premises. Do they actually help to prove the conclusion?

Step 4:

Choose a template that allows you to attack the assumptions and premises in an organized way.

Step 5:

At the end of the essay, take a moment to illustrate how these same assumptions could be used to make the argument more compelling.

Step 6:

Read over the essay and edit your work.