Introduction

The early Christian apologist Lactantius (240–330 ce) identifies a failed ritual of divination as the spark that set off the Great Persecution of the early church that ended with Constantine’s Edict of Toleration in 313 ce. While in Antioch in 299 ce, Emperor Diocletian, whose courtiers included both pagans and Christians, arranged for the slaughter of some cattle so “that from their livers he might obtain a prognostic of events” (De Mortibus Persecutorum X; Anti-Nicene Fathers 7:304). During the sacrificial rites, his Christian courtiers surreptitiously made the sign of the cross. Lactantius says that this action chased away “the daemons” so that no tokens for divination were found on the livers no matter how often the rites were repeated. Eventually the chief haruspex realized “there are profane persons here, who obstruct the rites” (ibid.).1

Diocletian’s initial response was to order his courtiers to sacrifice to the Roman gods or be whipped. Soldiers were ordered to do likewise or be discharged. Goaded by Galerius, his co-ruler and son-in-law, to rid the empire of “these enemies of the gods and adversaries of the established religious ceremonies,” Diocletian sent an embassy to inquire of Apollo at Didymus. On the basis of this oracle, February 23, 303, the festival of Terminus, god of boundaries, was selected as an auspicious day to “terminate, as it were, the Christian religion” (Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum XI–XII, ANF 7:305). Churches were razed, scriptures burned, treasures seized, clergy arrested. Christians were forbidden to assemble for worship and deprived of rank, property, and the due process of law unless they sacrificed to the gods of Rome.

This incident demonstrates graphically how very important access to knowledge from the gods was in the Roman world. To help us understand the phenomenon of divination, we will draw upon the field of ritual studies, especially Catherine Bell’s Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice (1992) and Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions (1997). Her focus on the process of ritualization and its role in power relationships, together with her genres of ritual activity, serves as an etic model—i.e., a cognitive map—for observing, categorizing, comparing, synthesizing, and analyzing Greco–Roman, Judean, Jesus group, and early church rituals for accessing divine knowledge.

Catherine Bell on ritualization

Bell defines ritualization as a human practice that is situational, strategic, embedded in “misrecognition,” and reproducing “redemptive hegemony.” Ritual practices are situational, that is, they are rooted in real cultural and historical circumstances, and cannot be grasped apart from their specific contexts. Ritual practices are inherently strategic, manipulative, and expedient, involving situational schemes, tactics, and strategies that construct meanings and values, posit relationships of authority and submission, and reproduce patterns from the past even as they reinterpret and transform them. Misrecognition refers to the way leaders and participants see themselves as responding naturally and appropriately to a given set of circumstances, but often do not see how their activity creates and generates, reorders and reinterprets the situation they seek to address. Redemptive hegemony denotes the way participation in ritual practices produces a vision for personal action and empowerment (1992, 81–84; 1997, 81–83).

Bell sees ritualization primarily as a strategy for the construction of power relationships. Drawing on the work of Michel Foucault, she defines power as a mode of action aimed at directing the activity and conduct of others without coercion or violence. Power relationships cannot exist in the absence of freedom, the option of acting differently, the possibility of resistance, escape, or flight. She writes, “A power relationship undoes itself when it succeeds in reducing the other to total subservience or transforming the other into an overt adversary” (1992, 201). Ritualization constructs power relationships by differentiating and privileging particular activities, delineating special places and times, and identifying specialized personnel, objects, texts, dress, gestures, and speech for a particular constituency (1992, 197–205). One way to get at this power dimension when analyzing any particular ritual action is to ask this question: in this ritual, what/who affects what/whom, by what means, in what circumstances, for what purpose, and according to whom? (adapted from Quack and Tobelmann 2010, 17–18).

In the ritual described as this chapter opens, Diocletian, the most powerful human in the Roman Empire seeks information about forthcoming events, information that is known only to the gods. Having this knowledge will make him more powerful, enabling him to act in accordance with the will of the gods. He arranges for a ritual of divination that involves examining the liver of a ritually slain animal for marks that may be read as omens. The ritual repeatedly fails to provide the expected results.

Rituals can fail for a variety of reasons, such as inadvertent mistakes in their performance, hence the repetition of Diocletian’s ritual, but to no avail. Rituals also fail because of the presence of inappropriate persons or conditions, violations of purity laws or taboos deemed essential to the ritual, and/or disruptive actions intended to “defeat” the rite (Grimes 1988, 110–16; Hauser-Schaublin 2007, 245–46). “Failure implies a disrupted relationship between humans and gods/ancestors that can be restored, if at all, only with great difficulty and sometimes after much loss” (Hauser-Schaublin 2007, 245). In many cultures, ritual failure is greatly feared as a catalyst for natural catastrophes, illness, and death. Christian refusals to offer sacrifices to the gods and the images of the emperor were often cited as the cause of natural disasters in the ancient world (Tertullian, Ad Nationes 1.9).

Diocletian’s ritual specialists concluded that their rituals of divination failed due to the presence and actions of “profane”—impure, unclean, inappropriate—persons. The Christian Lactantius claims the “daemons” fled when the emperor’s Christian courtiers made the sign of the cross. The situation appears to be one of competition and rivalry between traditional Roman religious practices and emerging Christianity. Diocletian was unable to overlook this ritual failure, and sought to purge the imperial service, the military, and eventually the empire itself of these profane persons. At this point we might wonder, what kind of rituals were these? What was their purpose?

Bell proposes six genres or categories of ritual action as a means of classifying and analyzing the plethora of rituals observed in human societies. Her genres are not intended to be definitive or exhaustive, as she states, “there are many other recognizable rituals that could be usefully classified in other categories, and there are rituals that could logically be placed in more than one category” (1997, 94). She names six genres as examples of rituals that are primarily communal, traditional (i.e., based on ways of acting established in the past), and rooted in beliefs in divine beings. These include rites of passage; calendrical rites; rites of exchange and communion; rites of affliction; feasting, fasting, and festivals; and political rites (1997, 91–137).

Ancient rituals seeking access to knowledge from the god(s) can be classified in more than one category, and often represent overlapping, complementary, and even competing social and ritual systems. For example, rites of exchange and communion involve making offerings to the god(s) in expectation of receiving something in return such as fertility, long life, safe passage, or some abstract benefit (Bell 1997, 108). Diocletian makes sacrificial offerings to the god(s) with the expectation of receiving a sign of approval for his upcoming plans. But when the emperor orders his courtiers and soldiers to sacrifice to the Roman gods, he transforms a rite of exchange and communion into a political rite. Bell defines political rites as ceremonial practices that construct, display, and/or promote the power and interests of a particular political institution, constituency, or sub-group (1997, 128–29). The imperial order to sacrifice to the gods of Rome was a demand for a public demonstration of loyalty and submission to the empire and its rulers. Some Christians undoubtedly did so to avoid whipping or losing their jobs. Others, like Lactantius, chose to resign their posts.2

The seriousness of ritual success or failure in any given situation is linked to “ritual density,” how much ritual activity is present in a particular society or historical period. Bell, building on the work of Mary Douglas, correlates ritual density with social structure and ritual style. Societies like those of the ancient Mediterranean region that emphasize group identity and hierarchical social structures tend to have more ritual activity, predominantly of the “appease and appeal” and/or “cosmological ordering” styles (1997, 185). Rituals seeking access to knowledge from the god(s) are concerned about cosmologically ordering human activity, ensuring that human decisions and actions are aligned with the will of the god(s), and hence have a divine mandate (Bell 1997, 103). The failure of Diocletian’s ritual, therefore, had deep religious, political, and social implications.

Accessing divine knowledge in the Greco–Roman world

Divination is the name given to ritual practices intended to access knowledge from the god(s). It is premised on the belief that divine action produces signs in the physical universe that can be interpreted by humans to their benefit. Greco–Roman authors regarded divination as a transcultural phenomenon handed down from time immemorial. Cicero writes,

I am aware of no people, however refined and learned or however savage and ignorant, which does not think that signs are given of future events, and that certain persons can recognize those signs and foretell events before they occur.

(De divinatione 1.1 [Falconer, Loeb Classical Library])

He links various forms of divination with different peoples. The Chaldeans read the stars, the peoples of Asia Minor observe the songs and flights of birds, the Greeks turn to their oracle, while Rome’s founders handed on the gift of augury (De divinatione 1.2–3).

Cicero’s comments do not exhaust the wide variety of methods ancients employed to access knowledge from the gods. Presuming that any element of the physical world could become a conduit for communication from the gods, the ancients paid special attention to extraordinary activity in the environment such as comets, stars, eclipses, thunder, lightning, earthquakes, and so forth. They carefully observed the behavior of animals, examined the external appearance and internal organs of sacrificial animals. They believed the gods could manipulate inanimate objects such as beans or stones when used in rituals of casting lots. The ancients learned that changes in consciousness made humans open to heavenly contact through dreams, visions, auditions, and prophecy. Often various modes of divination were combined in order to confirm and substantiate a sign and its interpretation (Kitz 2003, 24–33). Diocletian’s ritual specialists sought information from the god Apollo through oracles in order to understand the absence of marks on the livers of the sacrificed cattle.

A brief description of a visit to the oracle of Delphi shows us how different types of rituals and methods of divination often worked together. The oracle at Delphi was the most prestigious religious site in the Greek world, dedicated to accessing knowledge from the god Apollo. A variety of ritual specialists staffed the shrine. The Pythia was chosen from a guild of priestesses native to Delphi specifically to seek answers to supplicants’ questions while in an alternate state of consciousness (ASC). Her responses were transmitted and recorded by a prophetes. One or two leading citizens of Delphi were chosen at a time to serve as lifelong priests, overseeing the activities of the shrine, offering sacrifices, and conducting some rites of divination.3

Prior to the divinatory session with the Pythia, supplicants purified themselves with holy water (a rite of purification), and made a sacrificial offering to the god Apollo (a rite of exchange and communion). This was usually a goat, which also served as a medium for divination. The animal was doused with holy water and watched to see if it trembled in the correct way, from the hooves up. This auspicious sign indicated the sacrifice and the consultation could proceed. Admission to the oracle’s anteroom was determined by honor, status, and/or by casting lots (another method of divination). The supplicant’s question was transmitted by a priest to the Pythia, who sought an answer from the god Apollo by entering an alternate state of consciousness while gazing into a dish of water. Her response was then transmitted back to the supplicant, and recorded (Plutarch, De Pythiae oraculis; Broad 2007, 36–39; Maurizio 1995, 83).

An appeal to the oracle involved a whole set of ritual activities, including rites of purification, rites of exchange, and multiple rites of divination. While the primary mode of divination at Delphi was the Pythia’s ASC experience, other non-ASC techniques were used as preliminaries to determine the timing and order in which petitions were presented.

Given that the supplicants at Delphi were most frequently members of ruling elites—i.e., private citizens of means, lawmakers, or delegations from city states or kings—Delphi functioned primarily as a site for the ritual construction, display, and promotion of their political interests as being cosmologically aligned. The oracle provided divine affirmation and legitimation of, or warned against, enacting laws, establishing colonies, going to war, and other matters of state. Roman elites behaved in similar ways, seeking divine knowledge to guide and validate their political affairs.

The desire to access divine knowledge was not limited to ruling elites. Private individuals consulted oracles to determine if and when to marry, undertake a voyage, or make a loan, while community leaders asked the god about projected crop yields, herd increases, and public health (Plutarch, De Pythiae oraculis 408C). Documents from third century ce Roman Egypt demonstrate that men and women, free people and slaves, businessmen and soldiers, the wealthy and those who could not pay their taxes sought advice on business and personal matters from oracles (Sortes Astrampsychi in De Villiers 1999, 47). It might be tempting to dismiss these as simply strange rituals practiced by superstitious pagan peoples that were completely alien to Judean and Christ-following groups. That would be a mistake.

Divination through alternate states of consciousness (ASC)

An extensive study undertaken by Ohio State University anthropologist Erika Bourguignon in the 1960s found that 80% of the forty-four Mediterranean societies studied had one or more institutionalized forms of ASC (1979, 236; Pilch 1996, 133). These are neurophysiological events marked by greater predominance of brain activity in the right hemisphere and non-frontal parts of the brain in contrast to “ordinary waking” consciousness, which is dominated by left brain activity (Newberg, d’Aquili, and Rouse 2001; Newberg and Waldman 2006; Newburg and Waldman 2010). ASCs can be induced by a wide variety of activities, such as drumming or chanting; fasting; exposure to extreme cold or heat or other physical or emotional stressors; meditation; community rituals; specific ritual postures; and alcohol and hallucinogens. ASCs always occur within the context of specific belief systems that fill them with culturally significant and expected scenarios, and provide the key to understanding and interpreting them. Three types of ASCs are commonly identified in the ancient world:

1Possession trances, in which a spirit being enters, speaks, or acts through a human.

2Sky journeys, sometimes called soul flight, where a human is transported to the divine realm.

3Meditative states that blur the boundaries between the human and divine realms.

(Winkelman 1997, 393–428; Goodman 1990, 71–75; DeMaris 2000, 11–15; Pilch 2004, 4–5; Williams 2006, 94–7; Craffert 2010, 126–46).

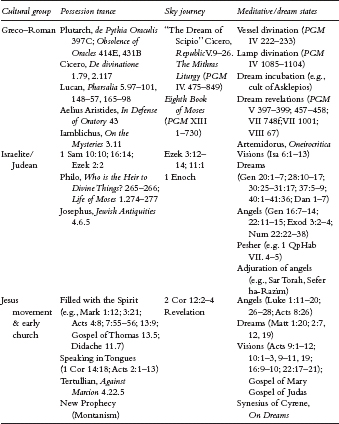

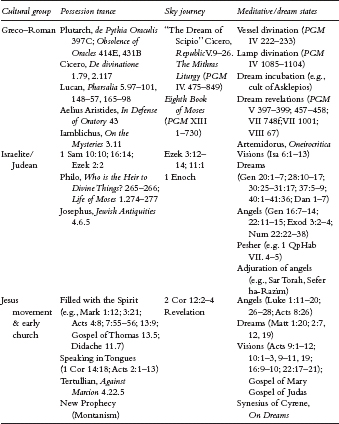

ASC techniques for accessing knowledge from god(s) were truly trans-cultural, as Table 3.1 demonstrates. Spirit possession, meditative states, and dreams were the most frequently reported and sought after by all groups. Ancients viewed dreams as means through which the gods and spirits could and did communicate with humans (Dodson 2002, 40). Although everyone had access to the divine through dreaming, most dreams were enigmatic and required interpretation. Priests in the temples of Asclepius interpreted the dreams of their patients to discern the causes of their ailments. Ancient Israelite patriarchs were led by their dreams (Gen 28:10–17), and served as dream interpreters for their adversaries (Gen 41; Dan 2:24–45; 4:19–27). Dreams guided Joseph in providing protection for the unborn and infant Jesus (Matt 1:18–2:23). The Apostle Paul is led by a dream to Macedonia (Acts 16:6–10). Artemidorus’ Oneirocritica (second century ce), the only surviving dream interpretation from the Greco–Roman world, cites numerous previous works on the subject. The Christian Bishop Synesius of Cyrene (died 413 ce) wrote a treatise On Dreams defending dreams as a path to the divine (Neil 2015, 23).

TABLE 3.1 Types of alternate states of consciousness in Ancient Greco–Roman cultures

The Greek Magical Papyri, dating from the second century bce to the fifth century ce, provide details of rituals intended to access divine knowledge through ASCs. Ritual specialists, occasionally assisted by a child medium, enacted vessel or lamp divinations to summon gods and daemons to answer questions posed by the persons or households that sought their counsel. Vessel divination involved pouring water into a receptacle, covering it with oil, and reading the reflections that appeared in the water. Lamp divination consisted of gazing at the burning wick of a lamp and seeing the gods within it. These rituals were well planned in advance to coincide with propitious phases of the moon or its position within certain signs of the zodiac. The diviner, the objects used, and the room in which the ritual was conducted had to be in a state of purity. The rituals included offerings, fumigations with incense, myrrh, and other substances, the application of special ointments to the eyes, and the repetition of long, complex incantations (Quack 2010).

Texts from Qumran (e.g., 4Q560) and the hekhalot literature attests to similar “magical” ASC practices within late antique Judaism. Fasting, washing, and seclusion prepare the practitioner for the ritual recitation of the divine name for the purpose of ascending to the heavens (sky journey) or conjuring an angelic presence or aid in response to human need (Swartz 2001; Swartz 1994; Lightstone 1986). Similar practices appear in the Christian New Prophecy (Montanist) movement of the second and third centuries ce, including fasting, the use of child mediums, trance, spirit possession, and the utterance of unintelligible sounds (Wypustek 1997).

Divinely inspired women known as sibyls prophesied at Delphi, Dodona, Didymus, and other holy sites around the Mediterranean. The last king of Rome (died 495 bce) purchased a collection of their oracles. These books, called Libri Sibyllini, were entrusted to the safekeeping of a college of fifteen curators, usually ex-consuls or ex-praetors, assisted by two Greek interpreters. They were kept secret and consulted by Roman rulers from the fourth century bce to the fourth century ce.

Israelite prophets received messages from God through visions, auditions, spirit possession, and dreams. Isaiah has a vision of God while worshipping in the Temple (Isa 6:1–13). The word of the Lord comes to Jeremiah (1:4; 2:1). The Israelite prophet Ezekiel describes how “a spirit entered into me” (2:2; 3:22), lifted him up, and transported him in visions to Jerusalem (8:3), and on another occasion set him down in a valley full of bones (37:1). Daniel’s visions came to him as dreams in the night (Dan 7:1–10). The biblical prophets spoke to the ruling elites. Samuel reluctantly follows God’s instructions to choose Israel’s first king, and later anoints David. Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Haggai, Zechariah, and possibly Habbakuk, were of priestly status, suggesting that ASC-produced oracles may have been a function of the central temple cult. Nathan was a household, or court, prophet mediating divine knowledge to King David. Amos, who was by trade a herdsman and dresser of sycamore trees, emerges as a prophet advocating social change and challenging the ruling elites.

The ancient Israelite prophetic texts came to take on a status not unlike the Libri Sibyllini, being regarded as oracles that spoke not only to the distant past, but which could with proper interpretation yield insight into current events. The Qumran community regarded its Teacher of Righteousness as a person to whom God had made known “all the mysteries of his servants the prophets” (1 QpHab VII.4–5). Their method of divinely revealed interpretation, known as pesher, correlated ancient prophecies with events occurring in the interpreter’s lifetime.

Jesus appears in the gospel narratives as an Israelite holy man for whom ASC experiences are foundational. As he emerges from the waters of the Jordan, Jesus sees the Spirit of God descending into him and hears a voice declaring that he is God’s beloved Son (Mark 1:9–11//Matt 3:13–17//Luke 3:21–22). The same Spirit drives Jesus into the wilderness where Satan tests him over a forty-day period (Mark 1:12–13//Matt 4:1–11//Luke 4:1–13). In the eyes of his peers, Jesus was a prophet (Mark 6:15//Matt 14:5//Luke 9:8; also John 4:19; 6:14; 7:37–40; 9:17), a view that coincided with Jesus’ own understanding of himself (Mark 6:5//Matt 13:57//Luke 4:24; 13:33; John 4:44).

The Johannine Jesus communicates in oracles of self-commendation, speaking for, or as, the bread of life (6:35, 48, 51); the light of the world (8:12; 9:5); the gate for the sheep (10:7, 9); the way, truth, and life (14:6–7); and the true vine (15:1). Jesus’ prophetic cry, “Let anyone who is thirsty come to me” (7:37) identifies him as one who speaks for, or as, divine Wisdom (Ringe 1999, 61; Cory 1997, 95–116). Jesus’ declarations, “I am from above” (8:23) and “I came from the Father” (16:28), fit the same pattern of self-commendation oracles typically associated with spirit possessed prophets and sibyls (Aune 1983, 40, 70–71). It has been suggested that the giving of the Spirit was a primary purpose of Jesus’ ministry in the Fourth Gospel (von Wahlde 1990, 117; Neyrey 1988, 182–215; Malina 1994, 173), and that the Johannine Jesus’ discourses were intended to facilitate entry into trance (Davies 1995, 200; Malina and Rohrbaugh 2003).

Jesus recruited disciples whom he sent out to teach, preach, and cast out demons (Mark 3:13–15//Matt 10:1–4//Luke 6:12–16). Jesus’ identity as God’s beloved Son was revealed through ASC experiences, such as the transfiguration (Mark 9:2–10//Matt 17:1–9//Luke 9:28–36). A vision of angels at the site of his tomb informs Jesus’ women followers that he had been raised from the dead (Mark 16:1–8//Matt 18:1–8//Luke 24:1–12//Jn 20:1–10). The disciples’ encounters with the risen Christ all occurred in ASCs (Pilch 1998, 52–60).

In Acts, every significant step in spreading the good news of Jesus is the result of some form of ASC. Unbelievers hear the gospel preached by persons “filled with the Holy Spirit” (4:8; 7:55–56; 13:9–11). An Ethiopian eunuch is baptized when an angel directs Philip to intercept him on the wilderness road from Jerusalem to Gaza (8:26–40). Saul has been blind and fasting for three days, when during his prayer he sees a vision of Ananias coming to lay hands on him (9:9–12). Ananias is directed to tend Saul in a dream vision (9:10–19). Prayer (a meditative state) and almsgiving prepare the centurion Cornelius for a vision (10:1–3). Peter is fasting and praying when he falls into a trance and sees the heavens opened to reveal a sheet filled with all kinds of animals descending from the sky (10:9–11). While Peter is still focused on puzzling out the meaning of this vision, the Spirit speaks to him again (10:19). Worship, fasting, and prayer set the stage for the Spirit’s instruction to set apart Barnabas and Saul (13:2–3). Prayer in the Temple provides the context for Paul’s vision of Jesus telling him to leave Jerusalem (22:17–18).

The importance of ASC-derived knowledge from God is further highlighted in Paul’s letters. Paul claims he was set apart and called by a revelation of Jesus Christ to proclaim the gospel among the Gentiles (Gal 1:12, 15–16). A revelation prompted him to visit Jerusalem fourteen years later to lay out before the acknowledged leaders the gospel he was proclaiming (Gal 2:2). When defending his status as an apostle to the Corinthians, Paul refers to a sky journey in which he was “caught up to the third heaven … in Paradise and heard things that are not to be told” (2 Cor 12:2–4). Paul shares the oracle he received in response to his prayer that the thorn in his flesh would leave him: “My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor 12: 8–9). Paul introduces innovative teaching as oracular pronouncements with phrases such as “through the Lord Jesus” (1 Thess 4:2–6), “by the word of the Lord” (1 Thess 4:15–17), or as “mystery” (1 Cor 15:51–52; Rom 11:25–26).

ASC experiences were a source of honor and status as well as a cause of conflict in Paul’s congregations. At the end of a discussion of marriage in 1 Cor 7:40, he quips, “and I think that I too have the Spirit of God,” a remark suggesting his opponents claimed the same status. Paul’s evaluation of speaking in tongues in relation to prophecy indicates rivalry between members adept at different forms of ASCs. Paul notes that he speaks in tongues more than any of them (1 Cor 14:18), but places a higher value on prophecy because it builds up, encourages, and consoles the entire community and not just the one speaking (1 Cor 14:3–4). He insists that any spiritually empowered person will recognize his instructions as “a command of the Lord” (1 Cor 14:37). Further evidence of rivalry over access to divine knowledge can be found in 1 John (prophetic conflict over access to divine knowledge), the Gospel of Thomas (especially Logion 13), Didache (prophets speaking in the spirit, 11.7), the Gospel of Mary and the Gospel of Judas (visionary encounters with the resurrected or never-crucified Christ).

Like their Greco–Roman and Judean neighbors, early Christ-followers consulted ancient prophetic texts to create their own ritualized worldview and way of life. The gospel writers presented many aspects of Jesus’ life as fulfillments of ancient prophecies, such as his virginal conception (Matt 1:22–23//Isa 7:14), his birth at Bethlehem (Matt 2:5–6; Mic 5:2; 2 Sam 5:2), his family’s sojourn in Egypt (Matt 2:15; Hos 11:1), Herod’s massacre of the innocents (Matt 2:17–18; Jer 31:15), John the Baptist’s ministry (Matt 3:3//Mark 1:2–3//Luke 3:4–6; Isa 40:3), the beginning of Jesus’ ministry in Galilee (Matt 4:14–16; Isa 9:1–2), Jesus’ cleansing of the Temple (John 2:17; Ps 69:9), his humble entry into Jerusalem riding on a donkey (Matt 21:1–5//John 12:12–15; Isa 62:11; Zech 9:9), and the piercing of his side during his crucifixion (John 19:36–37; Ps 34:20; Exod 12:46; Num 9:12; Zech 12:10).

Such divine validation of Jesus’ life and ministry was necessary because, as Paul states, “we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Judeans, and foolishness to Gentiles” (1 Cor 1:23). The problem was not just that no one in the ancient world was expecting a crucified messiah, but that a person who was crucified was “cursed,” a source of defilement for the land (Gal 3:13; Deut 21:23). We shall return to this subject later in the section the “sign of the cross.”

This brief survey shows us that Roman rulers likes Diocletian relied on oracles and turned to ancient collections of prophetic texts, as well as other techniques of divination, to guide their decision-making processes. Through these means ruling elites sought assurances that their policies and plans were cosmologically aligned with the will of the god(s). Private persons sought the services of ritual specialists who could interpret their dreams, and/or summon gods and daemons (if one was Greek), or angels (if one was Judean), to answer their most pressing questions. Jesus and his earliest followers were thoroughly enculturated in this world, using common means of accessing divine knowledge to construct an alternative set of power relations.

Non-ASC techniques of divination

Diocletian’s Great Persecution was sparked by the failure of his ritual specialists to discern special marks on the livers of sacrificed cattle. This form of divination is called haruspicy (also heptascopy or hepatomancy), and was widely practiced among the peoples of the Ancient Near East thousands of years before the founding of Rome (Pardee 2000, 232). Haruspicy consisted of sacrificing an animal (a rite of exchange) for the purpose of predicting forthcoming events and/or determining an appropriate course of action. The Romans picked up this practice from the Etruscans, creating a college of sixty haruspices of Etruscan descent maintained by the state and excluded from participation in political processes. These haruspices also read and interpreted environmental phenomena such as lightning, thunder, comet showers, and other astral events, for the purpose of predicting and correcting, if possible, the outcome of current events, including epidemics and wars.

Roman writers credited haruspicy with providing the first omens of Julius Caesar’s death: “While he was offering sacrifices on the day when he first sat on the golden throne and first appeared in public in a purple robe, no heart was found in the vitals of the votive ox” (Cicero, De divinatione 1.119 [Falconer, LCL]). It was a haruspex who allegedly uttered the famous warning to beware the ides of March (Valerius Maximus, Memorable Doings and Sayings 8.11.2). The appearance of a comet following Julius Caesar’s death was interpreted as signaling the ascent of his soul into the heavens (Suetonius, Divus Julius 88). Diocletian’s reliance on haruspicy for accessing divine knowledge was, therefore, unexceptional within his historical and cultural context.

Israelite texts demonstrate familiarity with such divinatory practices, e.g., the prophet Ezekiel describes the king of Babylon inspecting livers (Ezek 21:21). Biblical texts forbid such practices (Lev 19:26, 31; Deut 18:10, 14; 1 Sam 28:3), denigrate persons and groups who engage in them (Num 22:7; Isa 2:6; 1 Sam 15:23), and advocate punishing them (Lev 20:6; Deut 13:6; 2 Kgs 17:17; 2 Chr 33:6). Jesus’ followers were known for their refusal to participate in many common Greco–Roman ritual practices, especially those associated with the imperial cult or that involved sacrifice. They did, nevertheless, pay attention to divine portents in the natural world, taking notice of lightning, earthquakes, and crowing roosters (Matt 24:27; 26:34, 74–75; 27:54; Luke 17:24; Rev 4:5; 6:12; 8:5; 11:3, 18; 16:18).

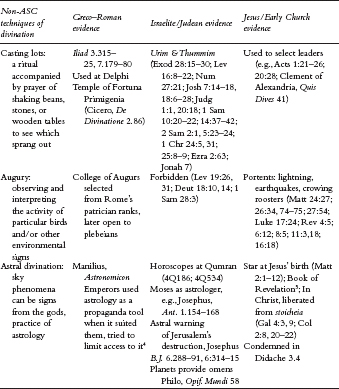

Although the Scriptures explicitly condemn divination, augury, soothsaying, sorcery, casting spells, and consulting ghosts, spirits, or the dead (Deut 18:10), Israelites, Judeans, and Christ-followers were just as interested as anyone else in the ancient world in determining God’s will in advance, if they could. While they opposed some forms of divination, such as reading the entrails of sacrificial animals, they appreciated and adapted others for their own purposes, as we can see in Table 3.2.

TABLE 3.2 Non-ASC techniques of divination common in the ancient world

Casting lots, as method of divination, is attested in ancient Near Eastern, Hebrew, Greek, and Roman texts. The process consists of throwing “lots” (stones, beans, pieces of wood) into a container such as a pouch or helmet or whatever is at hand. This is shaken up and down until one of them leaps, springs, jumps, or is cast out. Prayer invoking the god whose decision or judgment is sought accompanies the process (Kitz 2000). The heroes of the Iliad cast lots to determine who fought whom. As we have seen, lot casting at Delphi determined the order of presentation to the Pythia. A famous lot oracle was a feature of the temple of Fortune at Praeneste near Rome (Cicero, De divinatione 2.86). The vestments of Israel’s high priest included a jewel-encrusted pouch, containing an instrument of decision known as the Urim and Thummim (Exod 28:15–30). It consisted of two or more lots (Prov 16:33) used to determine God’s judgment regarding military actions, allocation of land, legal verdicts in the absence of evidence, and the choice of leaders. The followers of Jesus select a replacement for Judas Iscariot by casting lots (Acts 1:21–26). References to the Holy Spirit making or marking out persons as bishops suggests that the practice continued in the early church for some time (Acts 20:28; Clement of Alexandria, Quis Dives 42).

Interest in astral divination was widespread in the ancient Mediterranean world. The astral sciences of astrology and astronomy were stereotypically associated with the “Chaldeans” who were thought to be the inhabitants of Babylonia or a special class of Babylonian priests. Some Greeks, however, credited the Egyptians for the discovery of these sciences (Herodotus, Histories 2.4.1; Plato, Timaeus 22a–c), supported by an Egyptian tradition positing that the Babylonian astrologers were emigrants from Egypt (Diodorus Siculus 1.81.6). A Judean source alleges that Abraham brought astrology from Ur of the Chaldeans to Egypt (Josephus, Antiquities 1.154–168), while a Roman source traces the origins of “this great and holy science” to the god Mercury (Manilius, Astronomicon 1.25–37)

In the early imperial period, astral divination emerged as an alternative to more traditional Roman techniques of accessing divine knowledge. It proved to be simultaneously a useful propaganda tool and a source of anxiety for imperial rulers. In 11 ce, Augustus outlawed astrological consultations about his death, and forbid the practice of private astral divination. This did not prohibit his successors from retaining court astrologers, or from using astral divination to prop up their regimes and identify potential rivals and successors (Campion 2009; Reed 2004).

Astral divination is present among Judeans during the Second Temple period. Alexander Jannaeus’ election to kingship was divinely affirmed by an alleged conjunction of Jupiter (the king star) and Saturn (the seventh star heralding the Judean Sabbath) in Pisces in the year of his birth (126 bce). Jannaeus’ introduction of coins bearing an eight-pointed star combined this astrological information with the biblical prophecy of Numbers 24:17. Another conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in Pisces occurred at the vernal equinox of 7 bce. Herod the Great may have interpreted it as a threat to his power, contributing to the murder of his wife, sons, and a host of enemies (Von Stuckrud 2000, 29–30).

At Qumran, horoscopes were used to discover the disposition of potential new members (4Q186; 4Q534). The community also practiced brontologia, a technique for predicting the future by reading omens of thunder in connection with the moon’s path through the zodiac (4Q318). Philo describes the planets as signs of future events that influence agriculture and human fertility (Opif. 58, 101, 113, 117) and presents the twelve stones in the high priest’s breastplate as corresponding to the twelve signs of the zodiac (Spec. Leg. 1.87). Josephus similarly asserts that the seven branches of the menorah correspond to the seven planets (B.J. 5.217–218). He reports the presence of astral signs, including a comet visible for an entire year prior to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, which residents misinterpreted or ignored (B.J. 6:288–291, 314–315).

Knowledge of astral divination informs the story of the star that leads the magi to Bethlehem (Matt 2:1–12), Jesus’ final discourse revealing the fate of the Temple (Mark 13:1–37//Matt 24:1–44//Luke 21:5–33), and is the foundation of the book of Revelation (Malina and Rohrbaugh 2003, 361–63; Malina and Pilch 2000). Paul’s reference to being liberated from stoicheia (the elements) may be a reference to astral powers (Gal 4:3, 9; Col 2:8, 20–22). The Didache explicitly condemns reading omens, astrology, magic, and enchantments, regarding them as the slippery slope to idolatry (3.4). The church fathers commended the study of the stars (astronomy) but condemned astrology, arguing against the widespread notion that the movement of the stars (or fate) determined people’s lives (Stramara 2002).

This survey of various techniques of divination shows us that Greeks, Romans, Israelites, Judeans and the followers of Jesus were very interested in accessing knowledge from the gods. It demonstrates that Diocletian’s recourse to haruspicy really was unexceptional for a Roman ruler.

The questions that remain have to do with the sign of the cross, the alleged cause of the ritual failure, to which we turn now.

The sign of the cross

As previously stated, Jesus’ crucifixion was a serious obstacle of both Judeans and non-Israelites. Hebrew scripture declares that anyone hung on a tree is under God’s curse (Deut 21:23). Cicero regarded even the word “cross” as too offensive, too unworthy to be even mentioned within the hearing of free citizens (Pro Rabirio 16). Seneca argued that suicide was preferable to enduring death on a cross, writing:

Can any man be found willing to be fastened to the accursed tree, long sickly, already deformed, swelling with ugly tumors on chest and shoulders, and draw the breath of life amid long drawn-out agony? I think he would have many excuses for dying even before mounting the cross!

(Seneca, Epistulae Morales 101.14 [Gummere, LCL]).

For Josephus, crucifixion was “the most wretched of deaths” (B.J. 7.203), while Origen called it the “utterly vile death” (Commentary on Matthew 27:22). Crucifixion was a humiliating and degrading punishment reserved for runaway slaves, criminals, pirates, and enemies of the state. Jesus’ crucifixion was thus highly problematic. Even when presented alongside the experience of the resurrection, it remained a stumbling block and foolishness.

Yet, the evidence is clear that by the time of Diocletian making the sign of the cross on one’s forehead had become a significant Christian symbolic act. Writing in the previous century, Tertullian (ca. 155–240 ce) attests that:

At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign. If, for these and other such rules, you insist upon having positive Scripture injunction, you will find none. Tradition will be held forth to you as the originator of them, custom as their strengthener, and faith as their observer.

(De Corona Militis III–IV; ANF 3:95–96)

Here Tertullian asserts that the sign of the cross was rooted in the traditions and customs of the church rather than in any particular scriptural instruction. That did not prevent him from supplying a biblical antecedent for the practice in his treatise Against Marcion. Tertullian writes that Christ signed the apostles and the faithful with “the very seal” spoken of by Ezekiel (9:4). He describes this sign as the Greek letter Tau, which is the very form of the cross. This sign, together with the church’s sacraments and offerings of sacrifice, glorifies God. With these practices, Christ-followers are urged to “burst forth, and declare that the Spirit of the Creator prophesies of your Christ” (Against Marcion 3.22; ANF 3:341). For Tertullian, the sign of the cross is not just a symbol of Christian identity; it is a means of public proclamation (Longenecker 2015, 29–30).

In Ezekiel 9:4, God’s angelic messengers are instructed to put a mark (Hebrew tav) on the foreheads of those who sigh and groan over the abominations committed in Jerusalem. This tav depicted as an equilateral cross, either standing (+) or reclining (x), would serve as a mark of protection. This mark is treated as a symbol of eschatological protection and salvation in the Damascus Document (19:9–13) and in the Psalms of Solomon (15:6), suggesting a Judean origin for the identifying symbol of Christ’s followers (Longenecker 2015, 57). Certainly, Tertullian and other early Christian writers went to some lengths to demonstrate that the sign of the cross was predicted in the scriptures.6

So, when Diocletian’s Christ-following attendants “put the immortal sign on their foreheads,” what did they think they were doing? Did they employ the sign of the cross to protect themselves from being profaned by the emperor’s idolatrous practices? Did they imagine they were proclaiming the victory of Christ over the gods of Rome? Did they intend to cause a ritual failure? As Lactantius tells the story, making the sign of the cross caused the daemons to flee, overpowered by the sign of the cross. The rhetoric of the narrative leads us to read the sign of the cross as more than a symbolic, perhaps apotropaic, gesture. It becomes a ritual act constructing and promoting an alternate set of power relations rooted in divine knowledge revealed in the story of Jesus and a christological interpretation of ancient prophetic texts.

Conclusion

One can, of course, study rituals in the ancient world and in the early church without the aid of social-scientific concepts, theories, or models. There are, however, advantages to making use of social-science approaches, as I hope is evident in this chapter. Bell’s work on ritual provides an etic model, a cognitive map for observing, categorizing, comparing, synthesizing and analyzing ancient ritual practices. It helps us to see that a visit to an oracle in the Greco–Roman world involved a complex of different kinds of rites in addition to the central rite of divination. A cognitive map like Bell’s alerts us to details in gospel texts that point to ritual activity as the circumstances in which divine instruction was received (e.g., Acts 13:2). When reading New Testament texts that provide only the briefest of allusions to ritual activity, our cognitive maps and models can lead us to explore contemporaneous or culturally similar groups that were engaged in ritual practices such as fasting, prayer, or accessing divine knowledge. What we learn through such comparative studies will be suggestive, providing us with scenarios that are more probable than those we would generate on the basis of our personal experiences. More specifically, Bell’s work helps us understand that early Christian ritual gatherings provided more than just the context for the recitation of the texts we study. The ritual practices of the early church created Christ-followers, defined the “way” of Jesus, constructed “Christian” meanings and values, and orchestrated a cosmic framework in which making the sign of the cross was both protection and proclamation, especially in the midst of the Roman emperor’s rites of divination.

Notes

1Other early Christian sources associate this verdict with a Pythian oracle, perhaps at Daphne, consulted to determine the cause of the ritual failures (see Eusebius, Vita Constantini 2.48–60; Digeser, 2004 75).

2At the time, Lactantius, a Latin-speaking North African of Berber origin, was serving by imperial appointment as professor of rhetoric in the capital city of Nicomedia. While serving in this capacity he converted to Christianity, but resigned his office just before the emperor’s edict went into effect on February 24, 303 ce.

3Plutarch served as a priest at Delphi for about twenty years and provides much firsthand information about the oracle in his work De Pythiae oraculis.

4Campion 2009, 229–42; Reed 2004, 119–58.

5Malina and Pilch 2000.

6Epistle of Barnbas 11–12; Cyprian, Testimonies against the Jews Book 2. 21, 22, also cites Ezek 9:4; Origen reports how a Judean who believes in Christ interpreted the Hebrew letter tav as predicting the mark placed on the foreheads of Christians (Patrologia Graeca 13:800–801 quoted in Longenecker 2015, 59).

Bibliography

The Ante-Nicene Fathers. 1994. Edited by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson . 1885–1887. 10 vols. Repr., Peabody, MA: Hendrickson.

Aune, David E. 1983. Prophecy in Early Christianity and the Ancient Mediterranean World. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Bell, Catherine. 1992. Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bell, Catherine. 1997. Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bourguignon, Erika. 1979. Psychological Anthropology: An Introduction to Human Nature and Cultural Differences. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Broad, William J. 2007. The Oracle: Ancient Delphi and the Science Behind Its Lost Secrets. New York: Penguin Press.

Campion, Nicholas. 2009. A History of Western Astrology. London: Continuum.

Cicero. 1923. De Senectute, De Amicitia, De Divinatione. Translated by William A. Falconer . LCL. London: Heinemann.

Cory, Catherine. 1997. “Wisdom’s Rescue: A New Reading of the Tabernacles Discourse (John 7:1–8:59).” Journal of Biblical Literature 116:95–116.

Craffert, Pieter F. 2010. “Altered States of Consciousness: Visions, Spirit Possession, Sky Journeys.” Pp. 126–146 in Understanding the Social World of the New Testament. Edited by Dietmar Neufeld and Richard E. DeMaris . London: Routledge.

Davies, Stevan L. 1995. Jesus the Healer: Possession, Trance, and the Origins of Christianity. New York: Continuum.

DeMaris, Richard E. 2000. “Possession, Good and Bad – Ritual, Effects and Side-Effects: The Baptism of Jesus and Mark 1.9–11 from a Cross-Cultural Perspective.” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 80:3–30.

De Villiers, Pieter. 1999. “Interpreting the New Testament in the Light of Pagan Criticism of Oracles and Prophecies in Greco–Roman Times.” Neotestamentica 33.1:35–57.

Digeser, Elizabeth Depalma. 2004. “An Oracle of Apollo at Daphne and the Great Persecution.” Classical Philology 99.1:57–77.

Dodson, Derek S. 2002. “Dreams, The Ancient Novels, and the Gospel of Matthew: An Intertextual Study.” Perspectives in Religious Studies 29:39–52.

Goodman, Felicitas. 1990. Where the Spirits Ride the Wind: Trance Journeys and Other Ecstatic Experiences. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Grimes, Ronald L. 1988. “Infelitious Performance and Ritual Criticism.” Semeia 41:103–122.

Hauser-Schaublin, Brigitta. 2007. “Rivalling Rituals, Challenged Identities: Accusations of Ritual Mistakes as an Expression of Power Struggles in Bali (Indonesia).” Pp. 245–271 in When Rituals Go Wrong: Ritual Dynamics, Mistakes and Failures. Edited by Ute Huesken . Leiden: Brill.

Kitz, Anne Marie. 2000. “The Hebrew Terminology of Lot Casting and Its Ancient Near Eastern Context.” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 62:207–214.

Kitz, Anne Marie. 2003. “Prophecy as Divination.” CBQ 65:22–41.

Lightstone, Jack. 1986. “Christian Anti-Judaism in its Judaic Mirror: The Judaic Context of Early Christianity Revisited.” Pp. 103–132 in Anti-Judaism in Early Christianity, Volume 2: Separation and Polemic. Edited by Stephen G. Wilson . Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier Press.

Longenecker, Bruce W. 2015. The Cross Before Constantine: The Early Life of a Christian Symbol. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Malina, Bruce J. 1994. “The Maverick Christian Group – The Evidence of Sociolinguistics.” Biblical Theology Bulletin 24.4:167–182.

Malina, Bruce J., and John J. Pilch . 2000. Social-Science Commentary on the Book of Revelation. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Malina, Bruce J., and Richard L. Rohrbaugh . 2003. Social-Science Commentary on the Synoptics. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Maurizio, L. 1995. “Anthropology and Spirit Possession: A Reconsideration of the Pythia’s Role at Delphi.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 115:69–86.

Neil, Bronwen. 2015. “Synesius of Cyrene on Dreams as a Pathway to the Divine.” Phronema 30.2:19–36.

Newberg, Andrew, Eugene d’Aquili, and Vince Rouse . 2001. Why God Won’t Go Away. New York: Balantine Books.

Newberg, Andrew, and Mark Robert Waldman . 2006. Why We Believe What We Believe. New York: Free Press.

Newberg, Andrew, and Mark Robert Waldman . 2010. How God Changes Your Brain. New York: Balantine Books.

Neyrey, Jerome H. 1988. An Ideology of Revolt: John’s Christology in Social-Science Perspective. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Pardee, Dennis. 2000. “Divinatory and Sacrificial Rites.” Near Eastern Archaeology 63.4:232–234.

Pilch, John J. 1996. “Altered States of Consciousness: A ‘Kitbashed’ Model.” BTB 26:133–138.

Pilch, John J. 1998. “Appearances of the Risen Jesus in Cultural Context: Experiences of Alternate Reality.” BTB 28:52–60.

Pilch, John J. 2004. Visions and Healing in the Acts of the Apostles: How the Early Believers Experienced God. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press.

Quack, Joachim Friedrich. 2010. “Postulated and Real Efficacy in Late Antique Divination Rituals.” Journal of Ritual Studies 24.1:45–60.

Quack, Johannes, and Paul Tobelmann . 2010. “Questioning ‘Ritual Efficacy’.” JRitSt 24.1:13–27.

Reed, Annette Yoshiko. 2004. “Abraham as Chaldean Scientist and Father of the Jews: Josephus, Ant. 1.154–168, and the Greco–Roman Discourse about Astronomy/Astrology.” Journal for the Study of Judaism 35.2:119–158.

Ringe, Sharon H. 1999. Wisdom’s Friends: Community and Christology in the Fourth Gospel. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox.

Seneca . 1917–25. Ad Lucilium Epistulae Morales. Translated by R. M. Gummere . 3 vols. LCL. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Stramara, Daniel F., Jr. 2002. “Surveying the Heavens: Early Christian Writers on Astronomy.” St. Vladimir’s Quarterly 46.2:147–162.

Swartz, Michael D. 1994. “‘Like the Ministering Angels’: Ritual and Purity in Early Jewish Mysticism and Magic.” Association for Jewish Studies Review 19.2:135–167.

Swartz, Michael D. 2001. “The Dead Sea Scrolls and Later Jewish Magic and Mysticism.” Dead Sea Discoveries 8.2:182–193.

Von Stuckrud, Kocku. 2000. “Jewish and Christian Astrology in Late Antiquity.” Numen 47:1–40.

Von Wahlde, Urban C. 1990. The Johannine Commandments: 1 John and the Struggle for the Johannine Tradition. New York: Paulist.

Williams, Ritva H. 2006. Stewards, Prophets, Keepers of the Word: Leadership in the Early Church. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson.

Winkelman, Michael J. 1997. “Altered States of Consciousness and Religious Behavior.” Pp. 393–428 in Anthropology of Religion: A Handbook. Edited by S. D. Glazier . Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Wypustek, Andrej. 1997. “Magic, Montanism, Perpetua, and the Severan Persecution.” Vigilae Christianae 51:276–297.