THE CITATIONAL SOUL OF BLACK FOLK: W.E.B. DU BOIS

Strolling through New York’s Lower East Side one day early in the twentieth century, a young Russian Jewish immigrant impulsively purchases The Souls of Black Folk, having been attracted by the title. So moved by W.E.B. Du Bois’s recently published book is the twenty-four-year old D. Tabak that he writes a letter of gratitude to the author, urging Du Bois to “keep up the noble work you do” and attempting to convey the jumble of emotions he experienced while reading: “I was over powered by a peculiar pain that was so much akin to bliss, indignation stirring my blood, yet, somehow, being glad of that—growing furious at times, overcome with shame and disgrace, yet, from underneath all this, up swelled a keen sense of inner delight.” “Heavens,” exclaims Tabak, “who could describe in adequate terms that Satanic blending of both pain of a bleeding heart and joy [of] the gods?”1

A number of scholars have commented on this letter, which Du Bois saved and which bears vivid witness to the impact his seminal work was capable of having on its earliest readers across racial and ethnic lines.2 Of particular interest here, though, is the little-noted sentence following, and implicitly answering, the seemingly rhetorical question posed by Tabak (“Heavens who could describe . . . ?”). “But lo,” he continues, “all this inner agitation culminated to [sic] ‘tears, idle tears.’”3 At a loss for words, Tabak calls on Tennyson.

This allusion on the part of a recent (if obviously bookish) immigrant to an English-speaking country suggests the continued currency of this phrase from one of Tennyson’s most popular lyrics a half-century after its publication. But this turn to Tennyson by no means signals a turn away from Du Bois’s book. On the contrary, Tabak’s allusion shows that his sensitivity as a reader of Souls extends beyond its argument and pathos to include its range of references as well: Du Bois himself quotes and alludes to Tennyson several times, along with a number of other nineteenth-century British poets.

The Souls of Black Folk is widely recognized, in Eric Sundquist’s words, as “the preeminent modern text of African American cultural consciousness,”4 and its deployment of nineteenth-century British literature is both prominent and provocative. It therefore stands as the fitting culmination of the history traced in this book. Unlike most of the intertextual engagements we have examined thus far, however, Du Bois’s citations have been widely noted and discussed. Moreover, Du Bois himself tends to attract the adjective “Victorian” as a descriptor—of his intellectual formation, his prose style, his aesthetic, his morality—with greater frequency than virtually any other figure in the African American literary and intellectual tradition. Nonetheless, I will show, critics have been too quick to generalize about the presence of nineteenth-century British literature in Souls. They have rarely asked why Du Bois selected the specific authors, texts, and passages he cites or how these citations contribute to and intervene in a tradition of African American citation and intertextuality. Addressing these questions not only nuances our understanding of Du Bois’s rhetorical strategy but also leads us to reconsider a seemingly settled question in the scholarship on Souls: the role Du Bois assigns culture in the fight for racial equality.

As this chapter will also show, even as The Souls of Black Folk extends the tradition of African Americanization traced here and gives it its most visible expression, it also marks a turning point: when later African American writers engage with Victorian literature, they will not be engaging with it as contemporary, and when they engage with contemporary literature, they will not be engaging with Victorian literature. We will see this shift occurring within the pages of Souls itself, as Du Bois supplements his citations of no-longer-contemporary nineteenth-century poets who have a history of African American citation with citations of younger, turn-of-the-century poets. However, Du Bois himself never stops citing Victorian literature, and I end the chapter with an account of a late lecture in which he revisits and reworks his citational strategy in Souls by way of one of the most unlikely and spectacular African Americanizations of Victorian literature ever undertaken.

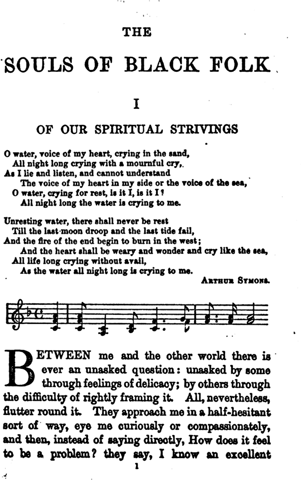

Published in 1903, The Souls of Black Folk flouts generic and disciplinary boundaries by bringing together lightly revised versions of Du Bois’s recently published historical and sociological articles along with several new chapters, including a short story and a memoir. Du Bois frames the book with a brief “Forethought” and “Afterthought,” and prefaces each of its fourteen chapters with a pair of epigraphs. Among the most famous paratexts in African American literary history, these formally innovative dual epigraphs consist in every case of lines of verse, typically identified by author, followed by several measures of unidentified musical notation drawn from African American folk songs and spirituals, which Du Bois calls “Sorrow Songs.”5 Eleven of the fourteen verse epigraphs are drawn from the work of white, nineteenth-century and turn-of-the-century poets: Americans James Russell Lowell, William Vaughn Moody, and John Greenleaf Whittier; and British writers Elizabeth Barrett Browning (who appears twice), Lord Byron, Edward FitzGerald (as translator of Omar Khayyám), William Sharp (under his pseudonym, Fiona Macleod), Algernon Swinburne, Arthur Symons, and Tennyson. In addition, one epigraph is from the Song of Solomon, and one, in German, from Friedrich Schiller’s play The Maid of Orleans. The verse epigraph for the last chapter, “The Sorrow Songs,” is taken from one of the songs themselves. (See figure 6.1)

Du Bois offers little explicit guidance on how to interpret the epigraphs. In the book’s “Forethought,” he explains that “Before each chapter, as now printed, stands a bar of the Sorrow Songs,—some echo of haunting melody from the only American music which welled up from black souls in the dark past” (6). At the beginning of the chapter on the Sorrow Songs he again notes, “before each thought that I have written in this book I have set a phrase, a haunting echo of these weird old songs in which the soul of the black slave spoke to men” (154–55), and in the course of that chapter he identifies the specific songs cited in various chapter epigraphs. But Du Bois says nothing about the verse epigraphs or about the pairings he constructs.6

Despite this reticence, critics universally agree that the paired epigraphs do more than merely reinforce the book’s coherence as a book (as opposed to the more miscellaneous collection of “essays and sketches” indicated by the book’s subtitle): the epigraphs perform rhetorical and ideological work that speaks to some of the central concerns of Souls. And differences of emphasis and nuance notwithstanding, a standard interpretation has emerged. This critical consensus emphasizes the profound gap between verse and musical epigraphs: they are described, variously (or not so variously), as “appearing to be from bizarrely different realms,”7 “appear[ing] as autonomous fragments from opposing worlds,”8 “not simply from different genres but virtually from different worlds (or at the least from radically segregated traditions, audiences, and cultures),”9 a “blunt dialectical challenge” marking “the gulf between black and white America.”10

6.1. Dual epigraphs to chapter 1 of The Souls of Black Folk.

Crucially, however, critics also tend to see the pairing of the epigraphs as graphically modeling the overcoming of this gap. Versions of this argument tend to invoke two of the book’s most famous passages: Du Bois’s assertion that “the end of [the Negro’s] striving is to be a co-worker in the kingdom of culture” (11), and his celebrated vision of the sociability of culture, which comes at the end of the chapter on “the training of black men”:

I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the Veil. (74)

According to Eric Sundquist, “[this] well-known passage defined a world in which the alternating epigraphs would be in communion, not in conflict, in which the Western and African traditions might harmoniously coexist.”11 In a similar vein, Ross Posnock asserts that the “paired epigraphs . . . represent the ‘kingdom [of culture]’ itself in miniature as a utopian realm above the Veil where sorrow songs and Swinburne dwell together ‘un-colored.’”12

For these critics, then, the form of The Souls of Black Folk’s paired epigraphs neatly enacts the book’s argument about culture. As I will show, however, this reading flattens out differences among the verse epigraphs themselves, which are hardly the uniform collection of Arnoldian touchstones critics often take them for. It also fails to situate the epigraphs within the history of African American citational practices. The poems and poets cited vary greatly with regard to their cultural standing and signification, on the one hand, and their distance from African American history and the African American literary tradition, on the other. Moreover, the tradition Du Bois extends and tropes on is not simply one of African American citation but rather of African Americanizing citation: that is, as we have seen throughout this book, citations (and other forms of intertextuality) that assign African American contents or referents to the texts and passages cited. These principles of selection and forms of deployment give the epigraphs different valences—different from one another and different from that usually ascribed to them.

SOULS AND THE AFRICAN AMERICAN TRADITION OF CITATION

Two factors in particular regarding the verse epigraphs have not received their due: the familiarity of some and the contemporaneity of others. To start with the former, we should note that fully half of the verse epigraphs in The Souls of Black Folk would not have seemed out of place in the pages of Frederick Douglass’ Paper a half-century earlier: those quoting Lowell, Whittier, Barrett Browning (twice), Byron, and Tennyson (as well as the Bible). This fact alone suggests that talk of the distance or even opposition between verse and musical epigraphs has been overstated. Most obviously, Lowell’s “The Present Crisis” and Whittier’s “Howard at Atlanta” are hardly “force[d] to bear witness to slavery,” as one critic claims: the former is one of the most famous antislavery poems and the latter is about emancipation.13 Similarly, while neither of the poems Du Bois cites by Elizabeth Barrett Browning—“A Vision of Poets” and “A Romance of the Ganges”—is about race or slavery, Barrett Browning herself was also identified with the abolitionist movement thanks to the two poems she published in the antislavery annual The Liberty Bell, “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” and “The Curse of a Nation.” These writers and their work were associated with an interracial fight for racial justice, not a rarefied realm of high culture removed from the lives of “black folk.”

Two of the other nineteenth-century British poets Du Bois cites in addition to Barrett Browning—Byron and Tennyson—occupy a different position, but not the remote one to which Du Bois’s critics tend to assign them. Unlike Lowell, Whittier, and Barrett Browning, these poets did not write about American slavery, but both were familiar presences in the writing and oratory of African Americans addressing issues of race—as we have seen at length with regard to Tennyson, and as we shall see for Byron as well, especially for the particular passage Du Bois cites. In citing these writers, then, Du Bois extends an existing tradition of African American citational practice.

Moreover, Du Bois does not simply join this tradition: he also references and tropes on it. In other words, his verse epigraphs—especially those by Byron and Tennyson—not only extend but also evoke an African American literary and rhetorical tradition, just as the musical epigraphs evoke an African American folk tradition. Indeed, I would go so far as to suggest that the paired epigraphs juxtapose these traditions, as much as black and white ones. From this perspective, the merger they epitomize is not interracial but intraracial, and the lines they cross are those of class and education, not color: that between the Byron- and Tennyson-citing Talented Tenth and the sorrow-song-composing black folk, a major concern throughout the book.14

The self-consciousness with which Du Bois uses Byron and Tennyson to summon an African American tradition of citation—and to associate this tradition with the black elite—is suggested by these poets’ appearance at the head of the two chapters in the book most explicitly concerned with the question of African American leadership: the Byron epigraph introduces the chapter devoted to Booker T. Washington, whom Du Bois challenges, while the Tennyson epigraph introduces that on Alexander Crummell, whom Du Bois eulogizes and implicitly positions himself as succeeding. These citations herald and contribute to this self-positioning.

Chapter 3 of Souls, “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others,” famously criticizes Washington for his willingness to accept civil inferiority for African Americans and his advocacy of mechanical training as opposed to what Du Bois calls “the higher education of Negro youth” (40). The chapter’s verse epigraph reads:

From birth till death enslaved; in word, in deed, unmanned!

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Hereditary bondsmen! Know ye not

Who would be free themselves must strike the blow?

Byron.

(34)

In Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, these lines refer to Greece. As Eric Sundquist was perhaps the first to note, however, the use of the latter two lines to rally African Americans to the cause of their own liberation began by the 1830s, when the lines circulated in African American and abolitionist newspapers.15 Henry Highland Garnet quotes them in his 1843 “Address to the Slaves of the United States,” and Martin Delany used them as the motto for a newspaper he published in the 1840s. Frederick Douglass used them as a chapter epigraph in his novella “The Heroic Slave”; quotes them again in his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, where they are also quoted in James McCune Smith’s introduction; and quotes them yet again in his third autobiography, the Life and Times of Frederick Douglass.16

In citing Byron’s incitement, then, Du Bois does not reach outside an African American tradition but takes his place in the line of writers and leaders who have cited this passage before him. Indeed, it is this tradition of citation he is citing, as much as the poem itself. In other words, the epigraph is a meta-epigraph, and it signifies not only that Du Bois sits with Byron, who winces not, but also that he stands with Garnet and Delaney and Douglass.

Or perhaps not quite with these African American predecessors, but in relation to them. Du Bois signifies upon and distinguishes himself from this tradition in two ways. First, he expands the usual citation to include another line from the poem, from two stanzas earlier: “From birth till death enslaved; in word, in deed, unmanned” (34). The addition of this line suggests that Du Bois has returned to the original poem as his source, and thus implies that even as Du Bois’s use of Byron references that of prior African Americans, his familiarity with Byron is not fully mediated by that history. Second, Du Bois breaks from prior citations of Byron by giving the lines an ironic twist. Robert Gooding-Williams (who is perhaps the first critic to note Du Bois’s expansion of the conventional citation) reads the extended citation as opposing Washington’s ostensible submissiveness, as captured by the first line, to the more defiant stance advocated by Du Bois and represented by the latter two lines.17 However, one of Du Bois’s final criticisms of Washington is that “his doctrine has tended to make the whites . . . shift the burden of the Negro problem to the Negro’s shoulders and stand aside as critical and rather pessimistic spectators.” “In fact,” Du Bois continues, “the burden belongs to the nation,” and the notion that the Negro’s “future rise depends primarily on his own efforts” is “a dangerous half-truth” (45, 44).18 It is thus Washington, not Du Bois, who gets aligned here with Byronic initiative and autonomy. The blow Du Bois himself strikes is against the historically uniform embrace of Byron’s lines by those who cite it. By the same token, insofar as Byron is not fully absorbed into the African American tradition here, the co-presence of his verse with bars of a Sorrow Song (“A Great Camp-Meeting in the Promised Land”) exemplifies the biracial effort Du Bois demands as much as the desired result of such efforts.

Du Bois’s epigraphic citation of Tennyson similarly participates in an African American history of citation while at the same time establishing a certain distance between Du Bois and a race leader with whom he ostensibly aligns himself. Here, though, this distancing involves citational practices themselves and the cultural politics they imply. Du Bois uses lines from “The Passing of Arthur” (part of Idylls of the King) as the verse epigraph for his elegiac chapter on Alexander Crummell, the African-nationalist intellectual and activist who died in 1898:

Then from the Dawn it seemed there came, but faint

As from beyond the limit of the world,

Like the last echo born of a great cry,

Sounds, as if some fair city were one voice

Around a king returning from his wars.

Tennyson.

(134)

The extent to which Crummell’s life and death echo King Arthur’s may seem as faint as the echo these lines describe, yet the location of the epigraph asks us to view Arthur as a figure for Crummell. Although Du Bois does not develop the analogy at length in a biographical sketch that focuses on Crummell’s blackness as the defining fact of his life—the source of the challenges he faced and the focus of his life’s work—he returns to it in the chapter’s closing paragraph: just as Tennyson’s lines describe the disappearance of the barge carrying Arthur’s body, so too does Du Bois conclude with a vision of Crummell “gliding” into “that dim world beyond,” greeted by a different “King,—a dark and pierced Jew.” The echoing “great cry” greeting Arthur is itself echoed in the “singing” of “the morning stars” greeting Crummell, and with which the chapter ends (142).

However bold this appropriative citation of “The Passing of Arthur” is in its particulars, by 1903 the African Americanizing deployment of Tennyson is also a well-established practice—a practice, as we have seen, with a long history, and which in the decade or so preceding Du Bois’s book includes such prominent examples as Anna Julia Cooper’s A Voice from the South (1892), Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “The Colored Soldiers” (1895), and Pauline Hopkins’s Contending Forces (1901). The resemblance between the roles assigned Tennyson in Souls and Contending Forces is especially striking given the difference in genre between the two works: just as turning points in Hopkins’s romance plot are marked by citations of Tennyson, as we saw in the previous chapter, so too are key moments in Du Bois’s historical narrative.19 Thus, Du Bois calls upon Tennyson not only when enacting the implicit passing of the torch from Crummell to himself but also, of more profound import, to figure both the origins of American slavery and its abolition: with devastating understatement, he writes of the initial establishment of slavery in the New World, “some one had blundered” (30), and he writes that slaves mistakenly looked forward to Emancipation as the “one divine event” that would bring “the end of all doubt and disappointment” (12). The former allusion, as noted in chapter 2, transforms Tennyson’s blunt characterization of a miscommunicated order in “The Charge of the Light Brigade” into a tragicomic euphemism for one of the most momentous events in world history; the latter allusion gives specific content to the studied vagueness of the concluding lines of In Memoriam: “one far-off divine event, / To which the whole creation moves.”20

When articulating his own more positive vision of the future, Du Bois again turns to In Memoriam: concluding a chapter on southern labor relations, he proclaims that “Only by a union of intelligence and sympathy across the color-line in this critical period of the Republic shall justice and right triumph,—

‘That mind and soul according well,

May make one music as before,

But vaster.’” (118–19)

Here again, Du Bois gives new, and newly racial, meaning to Tennyson’s language to evoke a key (future) moment in race relations, transforming the poet’s call for an end to the tension between knowledge and religious reverence into an image of interracial harmony.21 It is no wonder that D. Tabak was moved to cite Tennyson to capture the effect of reading Souls.

Yet Du Bois’s epigraphic citation of Tennyson does not align him with Alexander Crummell himself—not quite. Du Bois departs in a subtle but significant way from Crummell’s own typical citational practice and the relationship between race and culture it implies. Crummell is one of the most inveterate African American quoters of British literature in the nineteenth century, but he has not been a focus of this book because he does not typically repurpose or transpose the passages he quotes—that is, he rarely assigns them new, let alone specifically African American, referents. For example, when Crummell quotes William Wordsworth on “Splendor in the grass, and glory in the flower,” he does so to embroider his own description of “the attractiveness and charm of nature.” When he quotes Tennyson on “The blind hysterics of the Celt,” he is talking about the Irish.22 As this latter example suggests, when Crummell does attend to the treatment of race and ethnicity in nineteenth-century British literature, he tends simply to admire it or call on its authority. Thus, he quotes in full “the touching Sonnet of Wordsworth . . . on the occasion of the cruel exile of Negroes from France” and writes that Nature’s “conserving power which tends everywhere to fixity of type . . . reminds us of the lines of Tennyson:

Are God and nature, then, at strife,

That nature lends such evil dreams?

So careful of the type she seems,

So careless of the single life.”23

In contrast to Crummell, and as we have been seeing, when Du Bois cites nineteenth-century British poetry he frequently does so in such a way as to give the poetry a racial or specifically African American meaning or referent it does not already have—in short, he African Americanizes it. Even as the implicit comparison of Crummell’s death to that of Tennyson’s Arthur works to honor Crummell and elevate his stature, then, it also marks Du Bois’s break from his predecessor. His repurposing of British literature signals a more dialogic relationship to that literature than Crummell’s, and a more race-conscious view of culture than what the paired epigraphs are often read as symbolizing.

Both Du Bois’s difference from Crummell and the implications of this difference—which is to say, the implications of Du Bois’s African Americanizing use of nineteenth-century British literature—regarding Du Bois’s view of the relationship between race and culture, are made clearer by his references to Wordsworth’s “Intimations” ode. Whereas, as we have just seen, Crummell takes the ode on its own terms, Du Bois gives Wordsworth’s universalizing account of childhood and maturation social, and explicitly racial, content. Recounting Crummell’s youthful aspirations, Du Bois writes, “And then from that Vision Splendid all the glory faded slowly away”; he concludes the paragraph containing that phrase, “even then the burden had not lifted from that heart, for there had passed a glory from the earth”; and he repeats this phrase at the end of the following paragraph: “and then across his dream gleamed some faint after-glow of that first fair vision of youth—only an after-glow, for there had passed a glory from the earth” (137–38). Du Bois echoes several famous passages from Wordsworth’s poem—“The Youth . . . by the vision splendid / Is on his way attended; / At length the Man perceives it die away, / And fade into the light of common day”; “But yet I know, where’er I go, / That there hath pass’d away a glory from the earth”; “Whither is fled the visionary gleam? / Where is it now, the glory and the dream?”24 However, the falling off Du Bois allusively uses Wordsworth’s language to describe is not the inevitable result of growing up but rather the product of racial discrimination: Crummell’s vision fades and a glory passes from the earth because Crummell’s initial attempts to become a priest are met with the response, “It is all very natural—it is even commendable; but the General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church cannot admit a Negro” (137).

Du Bois’s assignment of specific historical content to Wordsworth’s aggressively departicularizing paradigm might seem to brush the ode against the grain; however, the point of this racializing redirection is not to demystify the poem’s false universalizing or accuse it of bad faith (as readers raised on the hermeneutics of suspicion might be quick to assume). Instead, Du Bois calls upon and reworks Wordsworth’s mythmaking to reinforce his own.25 This use of the “Intimations” ode picks up on and extends the use Du Bois makes of the same poem in an autobiographical passage at the beginning of Souls. Writing of his childhood, Du Bois remarks, “The shades of the prison-house closed round about us all.” Continuing, however, he introduces a distinction absent from Wordsworth’s ode: “walls strait and stubborn to the whitest, but relentlessly narrow, tall, and unscalable to sons of night who must plod darkly on in resignation” (10). Du Bois seeks here neither simply to inhabit nor to escape the prison-house of Wordsworth’s language, but instead to do both at once—that is, to grant the poem universal applicability while also using it to articulate a specifically black experience.26

The relevance of such finely parsed intertextuality to the central concerns of The Souls of Black Folk is suggested by this passage’s specific location in the first chapter. The sentence revising Wordsworth is followed immediately by the famous passage in which Du Bois ascribes a “double-consciousness” to African Americans—the “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others” and state of “two-ness”—American and Negro—he hopes to see superseded by the “merging” of this “double self into a better and truer self” in which “neither of the older selves [would] be lost” (11). Neither the existing form of subjectivity nor its desired replacement is directly analogous to the doubled vision required by the preceding intertextuality, yet the very shape of Du Bois’s discussion suggests that his treatment of Wordsworth anticipates and paves the way for their articulation. The fact that the discussion of double consciousness culminates in the declaration, “This, then, is the end of his striving: to be a co-worker in the kingdom of culture” (11), reinforces this connection between his vision of African American selfhood and the recalibration of Wordsworth that precedes it.

Strikingly, Du Bois’s later evocation of a cultural sphere free from racial prejudice is also preceded by allusive play with nineteenth-century British poetry, and the connection between these latter passages is less ambiguous. In the last sentence of the paragraph immediately preceding the pronouncement “I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not,” Du Bois, describing educated black men, avers that “to themselves in these the days that try their souls, the chance to soar in the dim blue air above the smoke is to their finer spirits boon and guerdon for what they lose on earth by being black” (73). This image looks ahead to the following paragraph’s utopian realm “above the Veil”; at the same time, though, it also looks back to the chapter’s verse epigraph:

Why, if the Soul can fling the Dust aside,

And naked on the Air of Heaven ride,

Were’t not a Shame—were’t not a Shame for him

In this clay carcase crippled to abide?

Omar Khayyám (FitzGerald) (62)

Like the epigraph, the sentence near the end of the chapter celebrates the transcendence of bodily materiality. Even as it echoes the epigraph, though, the later sentence also introduces a racial dimension into the dynamic the poem describes—“for ‘clay,’” Du Bois in effect says, “read: ‘black.’” As he did with Wordsworth’s ode, Du Bois turns Khayyám’s metaphysical lament into a sociohistorical one. Here, though, this move is paradoxical, as Du Bois imports race into a poem to make it into a poem about leaving race behind. In other words, rather than emblematizing a realm where racism or even race itself does not exist, the epigraph depicts—that is, is made to depict—the desire for and aspiration toward such a realm. The educated black man reading FitzGerald’s Omar Khayyám the way Du Bois reads him does not so much dwell above the Veil or soar in the dim blue air above the smoke as find in the poem an image of his very desire to do so.

These African Americanizing allusions to Tennyson, Wordsworth, and FitzGerald within the body of the text suggest that Du Bois’s use of nineteenth-century British poetry in general, including the epigraphs, conforms less to the utopian vision of culture evoked at moments within The Souls of Black Folk than to the view he later articulated in his essay “Criteria of Negro Art.” There Du Bois notoriously declares that “all Art is propaganda and ever must be,” and claims that “whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy.”27 As Ross Posnock emphasizes, however, Du Bois does not thereby choose politics over aesthetics but instead “radically defamiliarizes propaganda by giving it the function of restoring beauty to an impoverished American culture.”28 According to Posnock, Du Bois’s article “is intended as a wedge against premature closure”29 of the battle against racism by those who might see the ability of African Americans to produce beautiful art as reason to declare victory in, as Du Bois puts it, “the eternal struggle along the color line”30: as Du Bois asserts, “the Beauty of Truth and Freedom which shall some day be our heritage and the heritage of all civilized men is not in our hands yet.”31 While Du Bois credits the NAACP with promoting this view in the 1920s, I am arguing that this same view animates his use of nineteenth-century British poetry in Souls two decades earlier—its use, that is, to conduct that ongoing struggle.

Du Bois strengthens the connection between The Souls of Black Folk and “Criteria of Negro Art” by ending the later text with a quotation from one of the same poets deployed in Souls, William Vaughn Moody. In the final section of the essay, Du Bois argues that while “the ultimate art coming from black folk is going to be just as beautiful, and beautiful largely in the same ways, as the art that comes from white folk,” in the meantime “the point today” is not therefore to view art in a color-blind way but rather to use art to “compell recognition” of the humanity of “black folk.” Only when that recognition comes, he continues, will it be time to view their art as timeless: “when through art they compell recognition then let the world discover if it will that their art is as new as it is old and as old as new.” Ending on an evocative note, he concludes by describing and quoting a scene from Moody’s play The Fire-Bringer in which the sight of the heavens brings the cry, “It is the stars, it is the ancient stars, it is the young and everlasting stars!”32

Despite the congruence between the two texts, however, the weaponized view of art articulated most explicitly in “Criteria” is undoubtedly in tension with the vision of culture as a timeless realm of cross-racial respect and sociability so powerfully evoked by the “I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not” passage. At the same time, though, the later essay highlights and clarifies the underappreciated twist Du Bois’s argument takes at the end of that famous passage. After laying out his vision of what it would look like to “dwell above the Veil,” Du Bois continues the paragraph, and concludes the chapter, with a series of pointed questions:

Is this the life you grudge us, O knightly America? Is this the life you long to change into the dull red hideousness of Georgia? Are you so afraid lest peering from this high Pisgah, between Philistine and Amalekite, we sight the Promised Land? (74)

Up until the last sentence, it seems as if the realm of culture Du Bois has been describing is itself the Promised Land. Here, though, this realm becomes instead the mountaintop from which one can view that Promised Land. Presumably, this place makes the Promised Land visible by serving as its harbinger or type. Yet insofar as it is not itself the Promised Land, this place also serves—like the passage from the Rubáiyát as reworked in the preceding paragraph—as a reminder that one does not yet inhabit it.

SOULS AND THE CONTEMPORARY LITERARY FIELD

Du Bois’s use of culture to signify both ongoing struggle and transcendence—that is, his use of poems as “propaganda” in the ongoing antiracist effort to destroy cultural and political barriers as well as to shadow forth the prize for such efforts—helps explain the presence and role of another group of verse epigraphs in Souls. This group’s distinctiveness as a group has in fact rarely been recognized, thanks to the widespread tendency to view the epigraphs as symbolizing an established, monolithic Western canon or tradition. Just as the prior association of several of the poems and poets with African American writing, oratory, and print culture has been obscured by this tendency, so too has the sheer contemporaneity of others. Du Bois cites four living poets—Macleod (Sharp), Moody, Swinburne, and Symons—all of whom, except Swinburne, were members of his own generation.33 These living, active writers inhabit—and signify—the actual present tense rather than the historical present tense of the “I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not” passage.

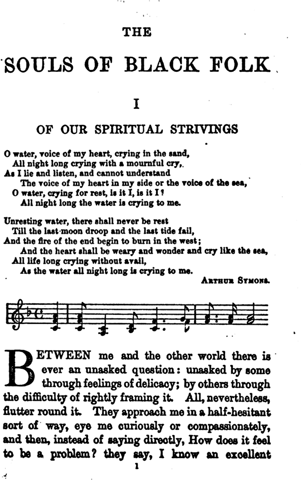

When Du Bois quotes Moody in “Criteria of Negro Art,” he does not name the poet but instead identifies him as “a classmate” he once had: the two were both at Harvard in the early 1890s.34 Yet even before Du Bois calls on Moody and his two other contemporaries for epigraphs in Souls, he already “dwells” with all three of them: not “above the Veil” or (only) on campus in Cambridge but rather in the pages of American periodicals. Not only were the poems he cites by all three poets quite recently published, but in addition they all appeared in the very magazines in which his own articles were appearing, including several of the pieces that became chapters in The Souls of Black Folk. Thus, Moody’s “The Brute” first appeared in 1901 in the Atlantic, which published versions of five of Du Bois’s chapters between 1897 and 1902, and books by Symons and Macleod containing the poems Du Bois cites (“The Crying of Water” and “Dim Face of Beauty,” respectively) were reviewed together in 1902 in The Dial, which had published one of Du Bois’s chapters the previous year. In a coincidence too remarkable to be dismissed as a coincidence, this review quotes in full, on the same page, both of the short lyrics Du Bois uses. (See figure 6.2)

The review from which Du Bois (presumably) took the Symons and Macleod poems points toward another common denominator linking Macleod, Moody, Swinburne, and Symons beyond the sheer fact of being alive at the time Du Bois was writing: all four poets received the strong endorsement of the author of that review, William Morton Payne. A prominent, Chicago-based literary critic at the turn of the century and the regular reviewer of poetry and fiction for The Dial for many years, Payne was also a leading champion of both the young Moody and the aging Swinburne (whose reputation remained contested at the time): in a review in The Dial in 1900, for example, Payne called Swinburne “the greatest [poet] that remains to us,” author of “upwards of a score of volumes of the noblest poetry to which the English tongue has given utterance”35; and in a 1901 review Payne declared of Moody that “no other new poet of the past score of years, either in America or in England, has displayed a finer promise upon the occasion of his first appearance.”36 Payne’s visibility may well have been at its height when Du Bois was compiling The Souls of Black Folk, as three collections of the critic’s literary articles from The Dial were published in 1902, the year before Souls appeared. These collections were published by A. C. McClurg, the same press that published Souls (and The Dial).

6.2. “Recent Poetry” review in The Dial, showing two poems used as epigraphs in Souls, May 1, 1902.

Whether or not Du Bois’s own taste was shaped by Payne, then, his sense of what was esteemed or fashionable in the literary world into which he was launching his book certainly seems to have been. By the same token, he could be confident that his readers would share in his recognition of these poets’ standing in the contemporary literary field. Unlike, say, Aristotle and Aurelius, their cultural currency resided precisely in their currentness.37 In citing these poets, then, Du Bois does not lay claim to the cultural past but rather displays his familiarity and identification with the cultural present. He positions himself—and the sorrow songs with which he pairs these poems—in the realm of cultural and political history in the making.

The terms in which Payne writes about these poems also shed light on Du Bois’s selections and on their relationships to other verse epigraphs and the musical epigraphs in Souls. The poem by Moody that heads the chapter “Of the Quest of the Golden Fleece,” “The Brute,” depicts the historical struggle to harness the force of machinery personified by its title character and thus seems broadly relevant to that chapter’s treatment of the sharecropping system.38 More relevant still, however, are the terms in which Payne praises Moody in his 1901 Dial review, writing with particular reference to Moody’s poems protesting U.S. imperial expansion: in “a period of inexpressible sadness to Americans who have been taught to cherish the teachings of Washington and Jefferson, of Sumner and Lincoln,” Payne laments, “How we have longed for the indignant words of protest that our Whittier or our Emerson or our Lowell would have voiced had their lives reached down to this unhappy time!” “But,” he continues, “in reading Mr. Moody’s ‘Ode in Time of Hesitation’ and his lines ‘On a Soldier Fallen in the Philippines,’ we are almost consoled for the silence of the prophet-voices that appealed so powerfully to the moral consciousness of the generation before our own.”39 Du Bois thus follows Payne in locating Moody in a specifically American poetic/prophetic tradition identified closely (though not exclusively) with the antislavery movement.

By contrast, Du Bois’s use of the Symons and Macleod poems both follows and departs from their treatment by Payne. Payne’s review praises Symons’s “The Crying of Water,” which serves as the verse epigraph to the first chapter of Souls, as “one of the most beautiful things in English song,” with “its tender pathos . . . fairly matched by the subtle music of the verse”; similarly, the review chooses “Dim Face of Beauty” from “a recent selection of [Macleod’s] songs . . . for the sake of its own sheer loveliness.”40 These formulations repeat and underscore the historical identification of lyric poems with or as “songs.” This identification suggests a greater formal kinship between the verse and musical epigraphs than is acknowledged by accounts that read the two kinds of epigraphs as representing opposed literate and oral cultures. To notice this kinship is not to deny all differences between these cultures, nor indeed to minimize the gulf between the sociohistorical reality out of which the sorrow songs and these tenderly pathetic lyrics emerged. However, this kinship, as foregrounded by Payne’s language, suggests that Du Bois chose poems that in some respect reached across these gulfs, whether through their subject matter, history of citation, or, as here, their formal properties.

In one key respect, though, Du Bois’s deployment of these poems runs athwart Payne’s characterization of them. We can hear in that characterization the influence of Victorian critic Walter Pater, who argued that

[poetry] may find a noble and quite legitimate function in the conveyance of moral or political aspiration, as often in the poetry of Victor Hugo. . . . But the ideal types of poetry are those in which this distinction [between the matter and the form] is reduced to its minimum; so that lyrical poetry, precisely because in it we are least able to detach the matter from the form, without a deduction of something from that matter itself, is, at least artistically, the highest and most complete form of poetry. And the very perfection of such poetry often appears to depend, in part, on a certain suppression or vagueness of mere subject, so that the meaning reaches us through ways not distinctly traceable by the understanding.41

Payne follows Pater in valuing the lyrics he selects for their inextricability of matter and form and their “vagueness of mere subject.” Du Bois himself embraces vagueness “as a political and aesthetic project” in Souls, as Ross Posnock has shown, and this stance helps account for his selection of these particular poems.42 Yet however much Du Bois values the evocativeness and defamiliarizing power of vagueness, ultimately he places that vagueness in the service of capturing and conveying “the strange meaning of being black here in the dawning of the Twentieth Century,” as the first sentence of the book’s “Forethought” announces.43 Thus, by recontextualizing Symons’s poem, Du Bois assigns a new cause for or meaning to its expression of sorrow—or rather, assigns it a specific cause and meaning for the first time.

Indeed, insofar as the most immediate new context Du Bois provides for his verse epigraphs is the bars of music from the sorrow songs (that for “The Crying of Water” is “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen”), he can be seen as reimagining the famous dictum with which Pater summarizes the view expressed above: “all art constantly aspires towards the condition of music.”44 In other words, whereas Du Bois’s practice, as captured by his own corresponding dictum—“all art is propaganda”—might seem to contradict Pater’s claim, it can also be seen as rendering it ironically true, by redefining “the condition of music”—at least this music—as “the articulate message of the slave to the world,” music that tells “of death and suffering and unvoiced longing toward a true world.”45 The epigraphic movement from poetry to musical notation thus enacts a miniature Paterian narrative—from poetry to music—but in so doing combines this aspiration with “the conveyance of moral or political aspiration” against which Pater opposes it.46 In citing such poets as Symons and Macleod, then, Du Bois aligns himself with contemporary literature and aesthetic doctrine even as he subtly manipulates them to serve his own agenda.

VICTORIAN AFTERLIFE: “THE VISION OF PHILLIS”

The recognizable contemporariness of the literature Du Bois cites, I have argued, is crucial to the effects he seeks. In thus expanding his archive from earlier nineteenth-century poets to include more recent works, Du Bois extends the practice of engagement with contemporary literature that played such an important role for virtually all earlier African Americanizers of Victorian literature. But in so doing he also signals the beginning of the end of this phenomenon, at least in its major phase, as a gap opens up between the Victorian and the contemporary. The sheer passage of time changes the nature and reduces the frequency, centrality, and intensity of African American engagements with Victorian literature. This falling off is greatly exacerbated by the rapid decline of Victorian literature’s critical reputation, on the one hand, and by the more gradual (and fitful) rise of a commitment to an autonomous African American literary tradition, on the other.

Du Bois himself acknowledges in 1945 that “It is not today fashionable to quote the poet of the Victorian Age.” Yet he makes that acknowledgment even as he quotes “Locksley Hall,”47 and Du Bois never stopped citing Victorian literature and drawing on it as a stylistic resource. One of the most notable examples comes in his 1928 novel Dark Princess, which not only references In Memoriam’s “far-off divine event,” as noted earlier, but also includes a pastiche of the opening paragraphs of Bleak House:

London. . . . Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping, and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights.48

Fall. Fall of leaf and sigh of wind. . . . Fall on the vast gray-green Atlantic, where waves of all waters heave and groan toward bitter storms to come. Fall in the crowded streets of New York. Fall in the heart of the world.49

This rewriting recalls Hannah Crafts’s even closer reworking of the same passage in The Bondwoman’s Narrative, as discussed in chapter 1 (“Gloom everywhere. Gloom up the Potomac”)—a striking coincidence, but presumably not another example of Du Bois’s metacitationality, since there is no evidence that he was familiar with Crafts’s unpublished manuscript.

Unlike Crafts’s pastiche, moreover, Du Bois’s is not part of a sustained engagement with Dickens’s novel, and Dark Princess as a whole is much less invested in the protocols of Victorian realism than was Du Bois’s earlier novel, The Quest of the Silver Fleece (1911).50 Du Bois’s later allusions often stand as isolated grace notes—although, given his evolving political stance, these notes are sometimes quite jarring. For example, in his last editorial for The Crisis, in 1934, Du Bois embraces voluntary segregation and decries “drowning our originality in imitation of mediocre white folks,” yet (as noted in my introduction) he does so using terms borrowed from Thomas Carlyle: “In this period of frustration and disappointment,” he writes, “we must turn from negation to affirmation, from the ever-lasting ‘No’ to the ever-lasting ‘Yes.’” Perhaps it is enough for Du Bois that the author of Sartor Resartus—not only white but also obnoxiously racist, even by the standards of his own time—was not “mediocre,” but here the productive tension of so many of Du Bois’s citations threatens to give way to disabling contradiction.51

A remarkable 1941 lecture by Du Bois flirts with a similar contradiction and—if we can read into the piece’s near-total absence from Du Bois criticism (despite its inclusion by Eric Sundquist in the Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader)—has largely been written off for succumbing to it. However, here Du Bois returns, I will argue, to his strategy in The Souls of Black Folk of granting Victorian literature a prominent role in his writing not out of a habit that has lost its purchase but instead precisely to revisit and revise his own earlier practice. Just as Du Bois’s citations of nineteenth-century British literature in Souls were in some cases meta-citations—citations of prior African American citations of that literature and indeed of an entire practice of citation—this late example performs a kind of auto-meta-intertextuality, an intertextual exercise in dialogue with Du Bois’s own earlier such exercises. This piece thus proves less a belated instance of the African Americanization of Victorian literature than a self-conscious return and reflective limit case.

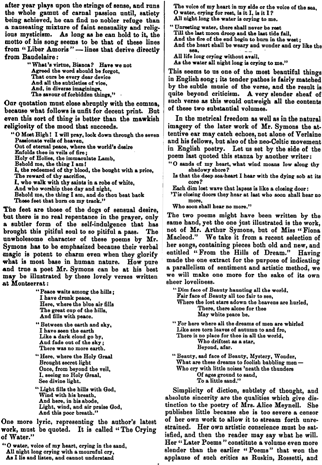

Participating in the seventy-fifth anniversary celebration of Fisk University as perhaps its most celebrated alumnus, Du Bois delivered a lecture titled “The Vision of Phillis the Blessed: An Allegory of Negro American Literature in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.” He begins the lecture by quoting the opening stanza of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “The Blessed Damozel”:

The blessed Damozel leaned out

From the gold bar of Heaven:

Her eyes were deeper than the depth

Of waters stilled at even;

She had three lilies in her hand

And the stars in her hair were seven.52

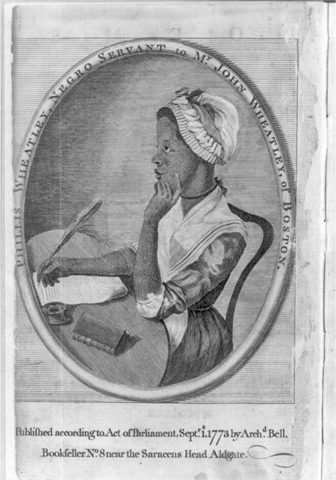

He then declares, rather remarkably, “I find in these well-known verses of Rossetti a text upon which to build a brief review of the literature of American Negroes before the twentieth century” (328). (See figure 6.3)

As Du Bois clearly expects his listeners to know (judging from his characterization of the lines he quotes as “well-known”), “The Blessed Damozel” is a kind of “inverted elegy”53 in which a young woman in heaven grieves over her separation from her still-living lover—or, alternately, in which a bereaved young man imagines his dead beloved thus grieving.54 The relevance of such a poem to Du Bois’s announced topic is not self-evident (to put it mildly), but Du Bois is quick to develop his conceit. Beginning his history with a discussion of Phillis Wheatley that includes biographical information and examples of her poetry, he repeatedly applies lines from “The Blessed Damozel” to “Phillis the Blessed,” as he calls her: describing her appearance, for example, he writes, “Her skin was darkly brown, velvet and glossy. Her hair, tight-curled, grasped her high round head like a close woven cap of tendrils. Her eyes were large and black—

6.3. W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Vision of Phillis the Blessed,” Fisk News, May 1941. Fisk University, John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library, Special Collections.

Her eyes were deeper than the depth,

Of waters stilled at even.” (328)

“Build[ing]” on Rossetti’s imagery, Du Bois assigns meaning of his own devising to the three lilies in the damozel’s hands, writing, “I seem to see her there . . . one hundred sixty-five years ago, with hands holding the three lilies of her thought; the tall white lily of her faith . . .; the tiger lily . . . typifying her inward frightened revolt; and finally the little purple flower of her sorrow” (330).

Similarly, if more spectacularly, Du Bois aggressively allegorizes the stars in the damozel’s hair. Incorporating Rossetti’s line into his own prose, he describes how seven singing stars “came down and nestled in [Phillis’s] hair—her stiff and crinkly close-curled hair; so the stars in her hair were seven,” and goes on to explain that these seven stars are African American writers “who, coming after her, continued and fulfilled her promise and tradition.” “One by one,” Du Bois continues, these writers “leapt heavenward like thin flames; and over the birth of each, Phillis shivered with appeal and longing, and before her eyes the Visions passed” (332)—alluding here to a later passage from Rossetti’s poem, in which the blessed damozel watches as the souls of lovers newly reunited by death “mounting up to God / Went by her like thin flames” (ll. 41–42).

In the middle part of the lecture, Du Bois briefly sketches the contributions of his chosen seven writers: David Walker, Armand Lanusse, George Williams, William Wells Brown, Alberry Whitman, Charles Chesnutt, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. This section is largely free of allusions to Rossetti. Toward the end of the lecture, though, he returns to both Wheatley and Rossetti, as he sketches a portrait of Phillis on her deathbed: “She lay stark and stiff, thin as a skeleton, worn to a shadow, her little dark hands crossed on her flat chest, clasping three lilies. Her crinkled hair formed a dim halo about her head. Yet . . . she did not die; she rose again and lived incarnate in Paul Laurence Dunbar. Again that soul of song lived in a thin, black body and behind eyes ‘Deeper than the depth / Of waters stilled at even’” (341). Soon thereafter, the lecture concludes as it began, with Du Bois quoting Rossetti’s opening stanza.

Viewed in isolation, Du Bois’s flamboyant allegorical gambit seems random if not bizarre, and more likely to distract from his narrative than to organize and punctuate it. When we view the lecture through the lens this book has sought to construct, however, we can see that Du Bois is both revisiting his own prior practice and extending a strand of the African American literary tradition he celebrates—that is, its very history of African Americanizing Victorian literature. In particular, “The Vision of Phillis” offers both an explicitation and elaboration of the intertextual strategy of The Souls of Black Folk, on the one hand, and a supplement or corrective to it, on the other.

Du Bois invites comparison of his lecture to his most famous book in several ways. Most obviously, his prefatory quotation of Victorian poetry recalls the verse epigraphs of The Souls of Black Folk structurally—that is, by virtue of its position as a prefatory quotation. Although Rossetti is not cited in the earlier work, his turn-of-the-century reception and reputation align him closely with several of the Victorian and fin-de-siècle poets Du Bois does cite. As we have seen, for example, Du Bois’s selections of recent poetry correspond with the critical judgments of William Morton Payne, and in his 1901 review of William Vaughn Moody’s work, Payne asserts that only two books of poetry so great as “to constitute an event in literature, or to set its writer among the enduring poets of his age” had appeared “In the memory of men now in their middle or advancing years”: Swinburne’s Poems and Ballads (the volume in which “Itylus,” the source of one of the verse epigraphs in Souls, appears) in 1866 and Rossetti’s Poems (the volume in which “The Blessed Damozel” was first published in book form) in 1870.55 The Pre-Raphaelite poet was also often viewed as a forerunner of the aestheticist movement with which several of Du Bois’s choices were associated, and the two youngest British poets Du Bois called upon for epigraphs, William Sharp (Fiona Macleod) and Arthur Symons, both wrote appreciative books about him.56

In choosing “The Blessed Damozel,” Du Bois also returns to the topoi of Heaven, the heavens, and the afterlife shared by several of the verse epigraphs in Souls—in particular, those by FitzGerald, Macleod, and Tennyson. Du Bois’s intertextuality is at its most layered and precise here: for example, leaning out from Heaven, the blessed damozel is imagined as having a voice “like the voice the stars / Had when they sang together”; similarly, Du Bois envisions Wheatley leaning out from Heaven as “the morning stars . . . sang together.” But even as Du Bois echoes Rossetti here, the added specification that it is the morning stars that are singing (an image that originates in the Book of Job) recalls as well a passage in The Souls of Black Folk—recalls, in fact, the passage that most closely anticipates the scenario of “Phillis the Blessed,” the final paragraph of the chapter on Alexander Crummell: as we saw, Du Bois pictures Crummell, like Wheatley, in Heaven; in doing so alludes to and reworks a Victorian poem (Tennyson’s “Passing of Arthur”); and ends with the image of “the morning stars . . . singing.”57

The specific ways in which Du Bois reworks Rossetti’s depiction of Heaven and the central figure of its blessed inhabitant not only recall but also flesh out the earlier book’s allusive and revisionary practices. They also pack a greater critical punch. For example, in “The Blessed Damozel,” as Antony Harrison observes, “Symbolism full of potentially Christian meaning—such as the seven stars in the Damozel’s hair and the three lilies in her hand—are drained of all such meaning and become merely ornamental.”58 Du Bois’s bold assignment of meaning to these symbols highlights this void and fills it, just as he anchors and gives specific content to the vague longings of Symons and Macleod. While the obvious arbitrariness of Du Bois’s allegorizing of the stars and lilies seems playful rather than critical, other tweaks and reworkings are more pointed, and more barbed than those in Souls. Thus, Du Bois’s racialization of the image of confinement in the “Intimations” ode is echoed and intensified by his tweaking of Rossetti’s comparable image of a barrier: whereas “the blessed damozel leaned out / From the gold bar of Heaven,” Wheatley “leaned out and then as now Heaven was barred with gold” (330). “Without lay poverty, darkness and dirt,” Du Bois adds, “without crawled crime and disease, while within the angels sang.” Like the blessed damozel, “Phillis yearned down from heaven to earth,” but she does so not out of desire for her lover but rather because she is “striving to lift the soul of a people” (330). According to Harrison, Rossetti’s poems “manipulate palimpsests parodically in order . . . to resist the social actuality which obsessed his contemporaries.”59 Du Bois reverses this process, using Rossetti’s own method to restore “social actuality” to the poem.

Similarly, whereas Du Bois’s use of King Arthur as a figure for Alexander Crummell does not emphasize the cross-racial nature of this identification, Du Bois repeatedly highlights a racially coded difference between the Blessed Damozel and Phillis the Blessed. Again and again, he calls attention to Phillis Wheatley’s hair, which he describes as “tight curled . . . like a close woven cap of tendrils,” and “stiff and crinkly close-curled.” Pre-Raphaelite hair this is not; the Blessed Damozel’s hair, we learn in the second stanza of the poem, “lay along her back” and “Was yellow like ripe corn” (ll. 11–12). Here, then, the mismatch between poem and lecture not only indexes Du Bois’s will to allegorical power but also makes visible the racial specificity of the poem’s ideal of beauty.60 (See figures 6.4, 6.5)

6.4. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Blessed Damozel, 1871–78. Oil on canvas, 53 ⅞″ × 38″. Harvard Art Museums / Fogg Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop, 1943.202. Photo: Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

In addition to opening up a greater critical distance between his own writing and a chosen Victorian intertext than he did in Souls even as he extends the citational practice of the earlier work, Du Bois also turns his attention to a body of work conspicuously absent from that book: African American literature itself. Although Phillis Wheatley is mentioned in passing in Souls, Du Bois’s championing of the Sorrow Songs seems to leave him no room, rhetorically, in which to situate—let alone celebrate—an African American literary tradition. “The Vision of Phillis” can thus be understood as supplementing Souls by sketching that tradition. From this perspective, the use of the epigraph-like Victorian poem—paired now not with a Sorrow Song but with Phillis Wheatley and indeed the lecture’s whole series of African American writers—signals the work’s corrective relationship to its predecessor.

6.5. Frontispiece portrait of Phillis Wheatley, from Wheatley, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (London: Printed for A. Bell, 1773).

In combination, though, these two departures from Souls—greater critical distance from the cited white-authored text and new focus on African American authors—raise a question: Why continue to grant nineteenth-century British literature such a prominent role? To be sure, Du Bois’s stance cannot be mistaken for that of William Stanley Braithwaite’s cloying poem “To Dante Gabriel Rossetti” (1908), which proclaims, “I salute thee . . . Master . . . as the one faultless voice / In the praise of Beauty blown / Since Keats’ lips were turned to stone.”61 Yet although Du Bois’s reworking of Rossetti contains an element of critique, the lecture’s very conceit runs the risk of positioning African American literature as secondary and of suggesting that, when it comes to aesthetic value, Rossetti’s “gold bar” remains the gold standard.

By way of contrast, consider the argument Alice Dunbar Nelson makes in her 1922 essay “Negro Literature for Negro Pupils.” Using imagery that does not allude to but resonates with “The Blessed Damozel,” Dunbar Nelson objects that “for two generations we have given brown and black children a blonde ideal of beauty to worship, a milk-white literature to assimilate, and a pearly Paradise to anticipate, in which their dark faces would be hopelessly out of place.”62 Like Dunbar Nelson, Du Bois sees how “milk-white literature” can promote racially exclusive norms and ideals; unlike Dunbar Nelson, however, Du Bois refuses to set “milk-white literature” aside, even when celebrating the creative achievements of African Americans.

Of course, it is precisely through his use of “The Blessed Damozel” that Du Bois is able to put “The Vision of Phillis” in dialogue with his earlier work, as we have seen. And if this dialogue revises the earlier practice, it does not reject outright that practice or the vision of culture bound up with it: Du Bois remains committed to an ideal of culture as integrated and free from prejudice, sharing the “dream” he ascribes to Wheatley of “a day . . . when it would be natural to see folk of all races mingling in a democracy of culture” (335). But his use of “The Blessed Damozel” also helps specify just what such “mingling” looks like to Du Bois.63

Despite his implicit criticism of Rossetti and the blatant arbitrariness of his allegorizing, there are elements of the poem that clearly appeal to Du Bois. Indeed, the very liberties Du Bois takes with the poem are in keeping with its spirit, and that of Rossetti’s artistic practice more generally, which Antony Harrison has characterized as “seriously parodic”—that is, combining sincerity and parody—in its treatment of its source and intertexts.64 Du Bois, we might say, is doing to Rossetti’s poem what Rossetti, in an evocative phrase, once described himself as doing to a poem by Tennyson: “allegoriz[ing] on one’s own hook on the subject of the poem, without killing, for oneself and everyone, a distinct idea of the poet’s.”65

Nor is Du Bois true to his source only insofar as he departs from it. On the contrary, two “distinct idea[s]” from the poem, one formal and one philosophical, make their presence felt in the lecture. Formally, the structure of the lecture recapitulates and makes explicit the implied structure of the poem: both are acts of projection, specifically a man attributing thoughts to a dead woman imagined to be in Heaven. Philosophically, Rossetti’s version of Heaven itself as a site of yearning corresponds to Du Bois’s understanding of culture as a site of struggle and striving as well as the goal of such striving—both the Promised Land and Pisgah, the place from which one gazes on the Promised Land. Moreover, whereas in Souls Du Bois flirted with the notion of a Heaven where bodies and blackness are left behind (for example, by way of his allusive play with the Rubáiyát), his commitment here to a specifically African American literary tradition jibes better with Rossetti’s notoriously physical version of Heaven (in which bodies are not left behind, as the Blessed Damozel’s bosom warms the bar and wilts the flowers she holds).

Instead of moving past “The Blessed Damozel” once the work of critique is done, then, Du Bois continues to “mingle” with it. He repeatedly cites key lines from it, giving them an incantatory quality while palimpsestically superimposing a new meaning on them. As in The Souls of Black Folk but more ostentatiously, he leverages his intertext to reinforce his own mythmaking. The success of this technique is suggested by a report in the same commemorative Fisk newsletter in which the lecture was published. According to this report, Du Bois’s listeners were neither puzzled by his gambit nor knowingly appreciative of his irony: they were “spellbound.”66

Mingling Rossetti’s language and imagery with his own to weave his spell, Du Bois thus manages to simultaneously acknowledge and transcend the incongruity between the Blessed Damozel and Phillis the Blessed. In a final flourish, he ends his lecture by conjuring a lingering image of the “darkly brown” foundational figure of the African American literary tradition—and does so by reproducing verbatim the Victorian image of yellow-haired beauty with which he began. Following Du Bois’s lead, I will conclude with this doubled vision of Heaven, which stands as the very apotheosis of the African Americanizing practices traced in this book.

And so the story ends. . . . Last night and each night:

The blessed Damozel leaned out

From the gold bar of Heaven:

Her eyes were deeper than the depth

Of waters stilled at even;

She had three lilies in her hand

And the stars in her hair were seven. (342)