Chapter 9

With Liberty and Inequality for All?

The white man knows how to make everything, but he does not know how to distribute it.

—Sitting Bull

Like Sitting Bull in the nineteenth century, some people think of the rise in income inequality in the United States, which has proceeded for thirty to forty years now, as an urgent socioeconomic problem that needs to be addressed. Some people don’t. Like it or not, one’s views on inequality hinge sensitively on value judgments—making this an inherently political question, not one on which technocrats hold any advantages over politicians. That said, sound economics still can shed light on important questions like why inequality has risen so much (for example: Is it the “natural” working of markets, or has public policy contributed?) and what we as a society can do about it, if we choose to. That’s what this chapter is about.

President Barack Obama clearly did think inequality had become a serious problem by Inauguration Day 2009, and he did want to do something to mitigate it. To that end, he subsequently pushed a recalcitrant Congress to make the tax code considerably more progressive, with several increases in top-bracket rates. And he created, again over stiff congressional resistance, what we now know as Obamacare, whose benefits—not to mention the taxes that finance them—are decidedly progressive. Add them together, and it amounted to a substantial redistribution of posttax income.

Eight years later, Donald Trump was elected president after campaigning as, among other things, the tribune of the working class. You may recall that he declared “I am your voice” in his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention in 2016. Yet once in office, his policies turned mainstream Republican: his health care proposals sought to strip tens of millions of Americans of their insurance coverage, his budget proposals sought to shred the social safety net, and his tax “reform” was perhaps the most regressive tax cut in history. Democrats objected vociferously to all these things.

Yes, the two parties disagree vehemently on redistributive policy, and have for years. But what are the facts?

The Age of Inequality

The years since around 1980 are sometimes referred to as the Age of Inequality. The label fits because virtually every measure of income or wealth inequality has risen substantially since then. Three basic facts sum up the phenomenon of rising inequality in the United States: it’s been large; it’s been long-lasting; and inequality here is higher than in other advanced countries.

Start with “large.” There are many ways to measure inequality. Some are simple, such as the share of income received by the top 10 percent, 5 percent, or 1 percent of the population. Others are rather complicated, such as the so-called Gini coefficient, which is computed using a mathematical formula I’ll use but not torture you with.* In consequence, there is no single, crisp answer to the seemingly straightforward question, How much has inequality risen since 1980? Check that. If you don’t insist on a number, there is a simple answer: quite a lot.

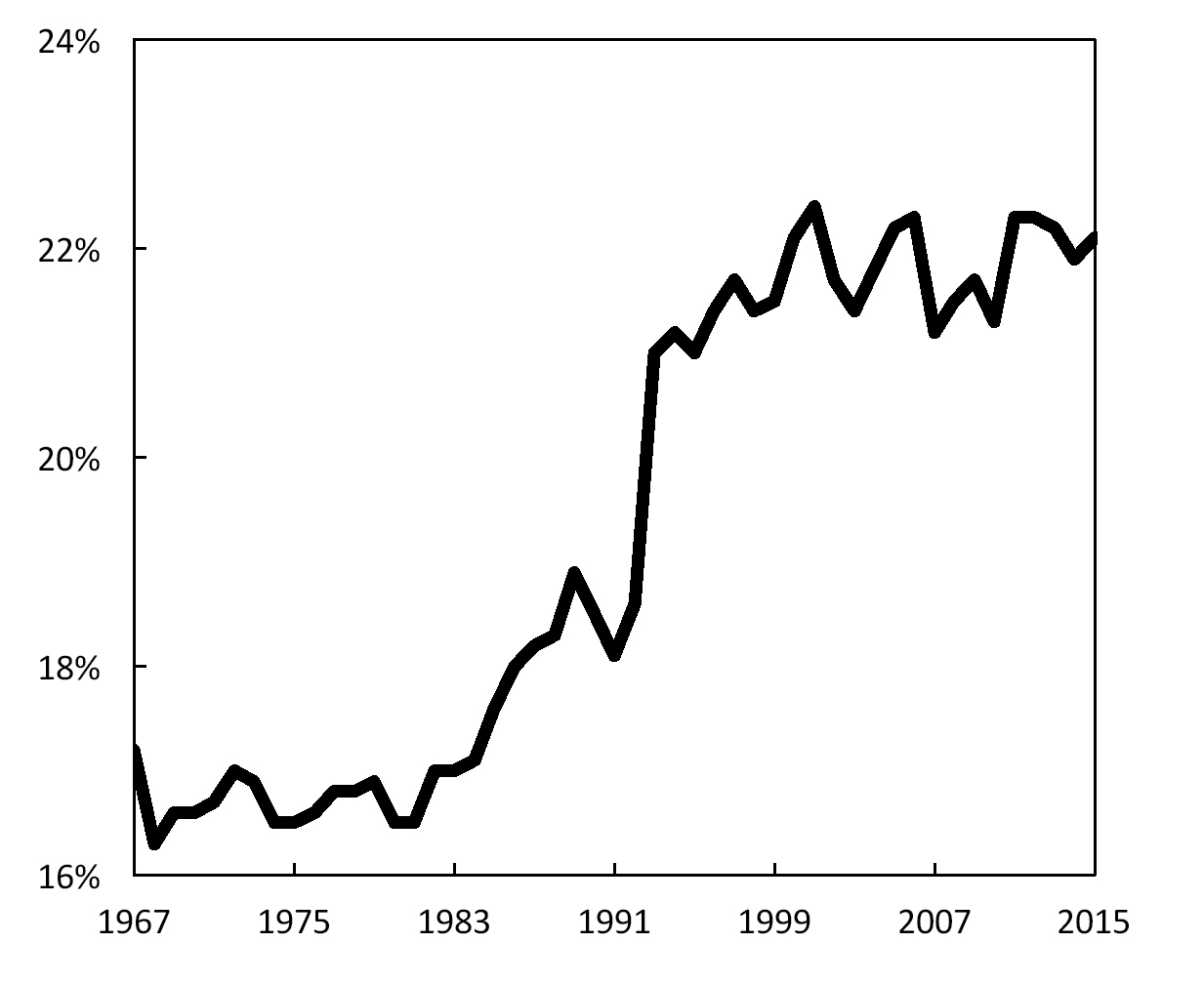

FIGURE 9.1 Share of US Household Income Received by Top 5%, 1967–2015

Source: US Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, Table H-2.

Here are three possible numerical answers, all based on the same underlying data from the Bureau of the Census. But each measures a different aspect of inequality and so gives a different quantitative answer. Had I taken data from multiple sources, the differences would have been greater still. But the picture they paint would have been consistent.

Figure 9.1 displays the share of household income received by the top 5 percent of households, ranked by income, from 1967 to 2015. This measure of the share of “the rich” was trendless (at around 16.5 percent) until 1981 and then began a steep climb up to 22.3 percent by 2006. It has been pretty stable since then.

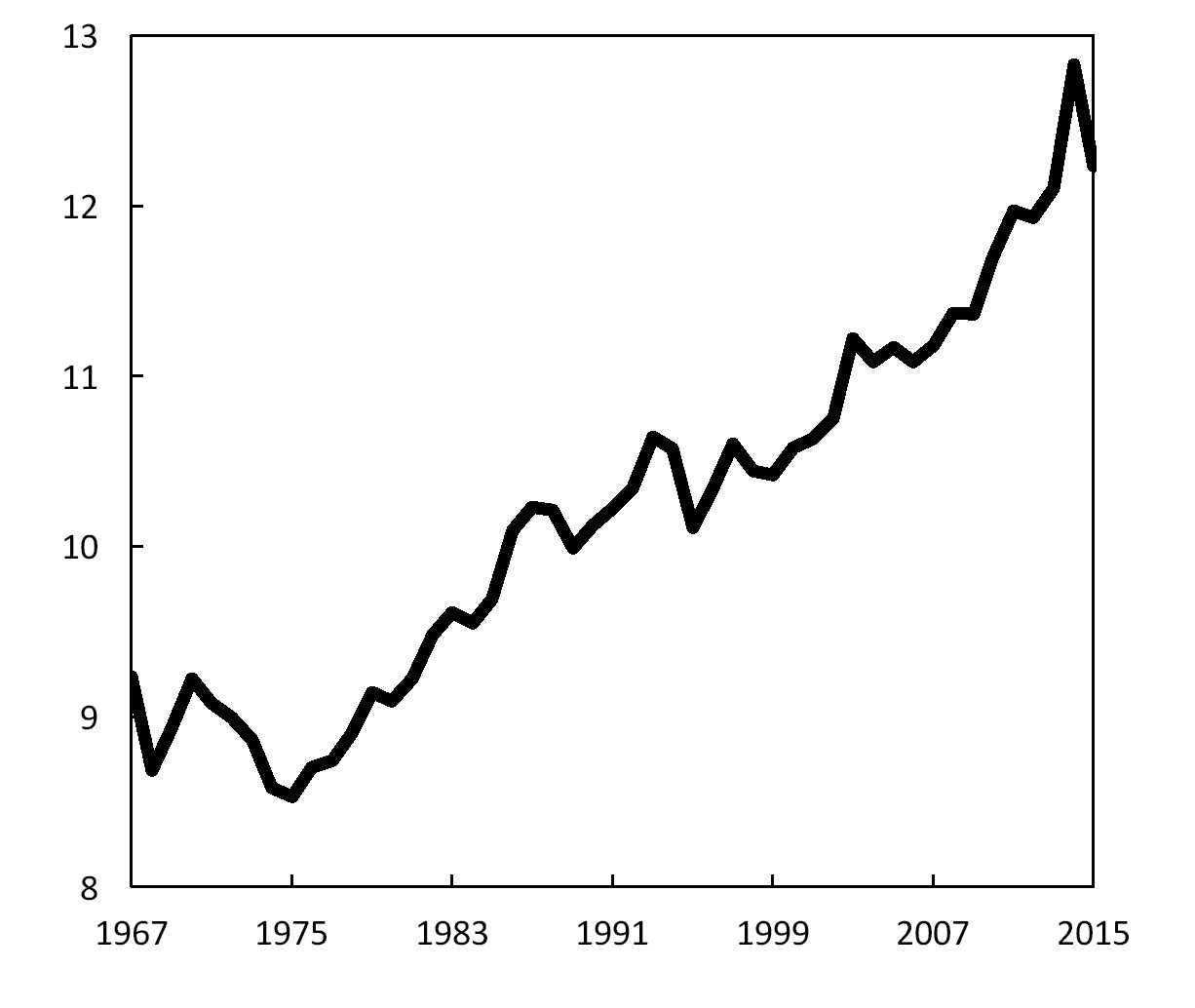

Figure 9.2 shows an alternative measure derived by comparing the incomes of the “rich” with those of the “poor.” Specifically, it’s the ratio of income at the ninetieth percentile (meaning the income level exceeded by only 10 percent of households) to income at the tenth percentile (which 90 percent of households exceed). This indicator starts at 8.7 times in 1977 and rises to a peak of 12.8 in 2014. That last number means that a rich family in 2014 (income of about $157,700) had almost thirteen times the income of a poor family (about $12,300).

FIGURE 9.2 The 90/10 US Household Income Ratio, 1967–2015

The figure shows the ratio of income at the ninetieth percentile to income at the tenth percentile. Source: US Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

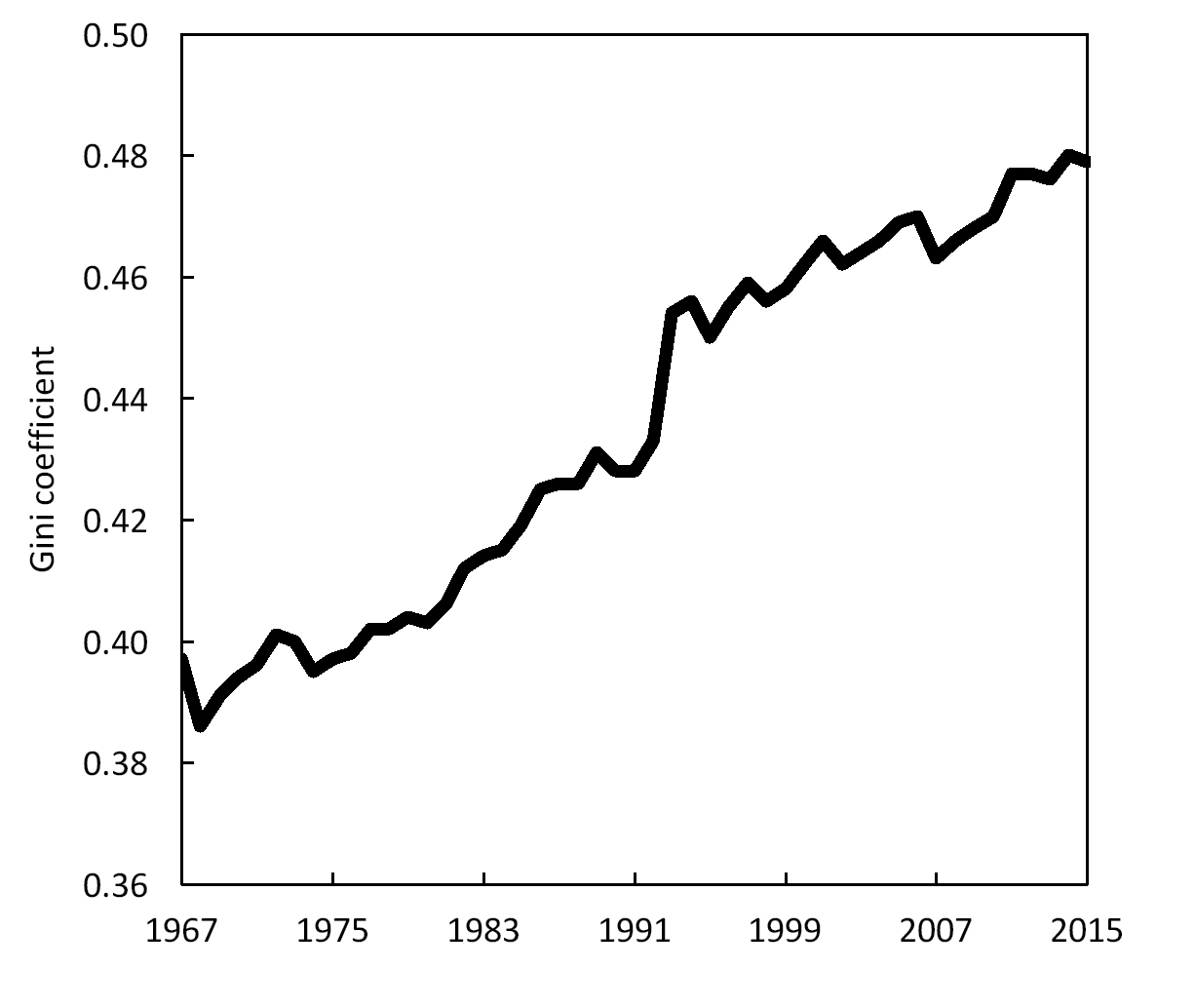

Finally, Figure 9.3 depicts the behavior of the aforementioned Gini coefficient, a complicated measure that pays attention to the entire income distribution, not just the extremes. The Gini measure ranges between zero (when every household has the same income) and 1.00 (when one household has all the income). Typical real-world numbers run around 0.4. The Gini coefficient for the United States rose from 0.398 in 1976 to 0.477 in 2011, and then roughly leveled off. As Gini coefficients go, a rise of 0.08 is a big deal. It’s roughly the difference, for example, between inequality in the unequal United States versus in egalitarian Ireland (based on data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD]).

FIGURE 9.3 Gini Coefficient for US Household Income, 1967–2015

The Gini coefficient ranges from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality). Source: US Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

Thus across just these three measures, and there are many others, the rise in inequality ranged between 21 percent and 47 percent, and the increase took place over the years 1976–2011 or 1977–2014 or 1981–2006. Take your pick. Fortunately, statistical quibbles like these need not detain us here. The basic fact is clear: income inequality has risen quite a lot since the late 1970s. (So, by the way, has wealth inequality, which I won’t deal with here.)

We need no additional data to demonstrate the second important fact: that the rise in inequality has persisted for decades. Just glance back at the three previous figures. The lines move steadily upward with few interruptions. Yes, there is a good reason why this period of US history has been dubbed the Age of Inequality. It has lasted a long time—and it may not be over yet.

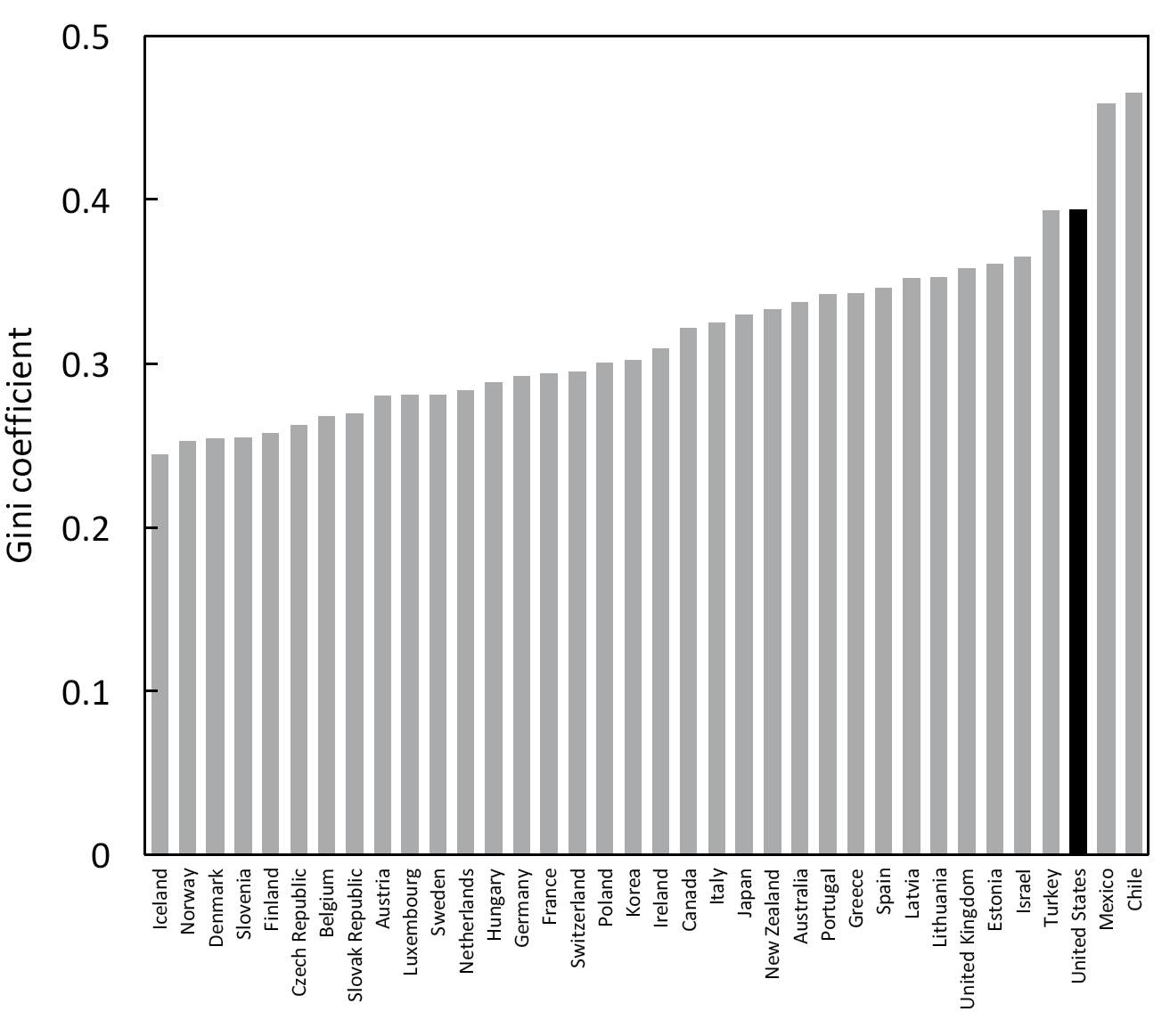

FIGURE 9.4 Gini Coefficients for Household Income, 2013–2014

The Gini coefficient ranges from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality). Data are from 2013 or 2014, whichever is the most recent year available. Source: OECD database.

The final basic fact, that inequality is higher in the United States than in other advanced countries, is much harder to establish because different countries measure both income and inequality differently. Indeed, it takes a somewhat Herculean effort to create consistent data that enable scholars and policymakers to make apples-to-apples comparisons across nations. Fortunately, several teams of researchers have done exactly that over the years, and they all find that inequality in the United States is at or close to the highest among all the world’s advanced industrial nations. Figure 9.4 is an example. It displays 2013–2014 data for thirty-six OECD countries. Only Mexico and Chile, which are hardly advanced industrial nations, had Gini coefficients higher than the United States.

Having looked first at income inequality, I now turn to wage inequality, which is where I want to concentrate. Why? Because for all but the richest Americans, income from work is almost the whole story. For most people, the income derived from owning capital or running businesses doesn’t amount to much. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that 80–86 percent of market income in the four lower quintiles of the income distribution derives from labor. Only in the top 1 percent is labor income a minority of total market income (36 percent). So if your concern is either envy or how vast fortunes are amassed, then by all means dote on income from capital. Neither Bill Gates nor Jeff Bezos got rich by earning high paychecks. (But LeBron James and Tom Cruise did.) If, however, you’re more concerned with what’s happened to the lower 99 percent of American families, you should concentrate on income from work, as I will.

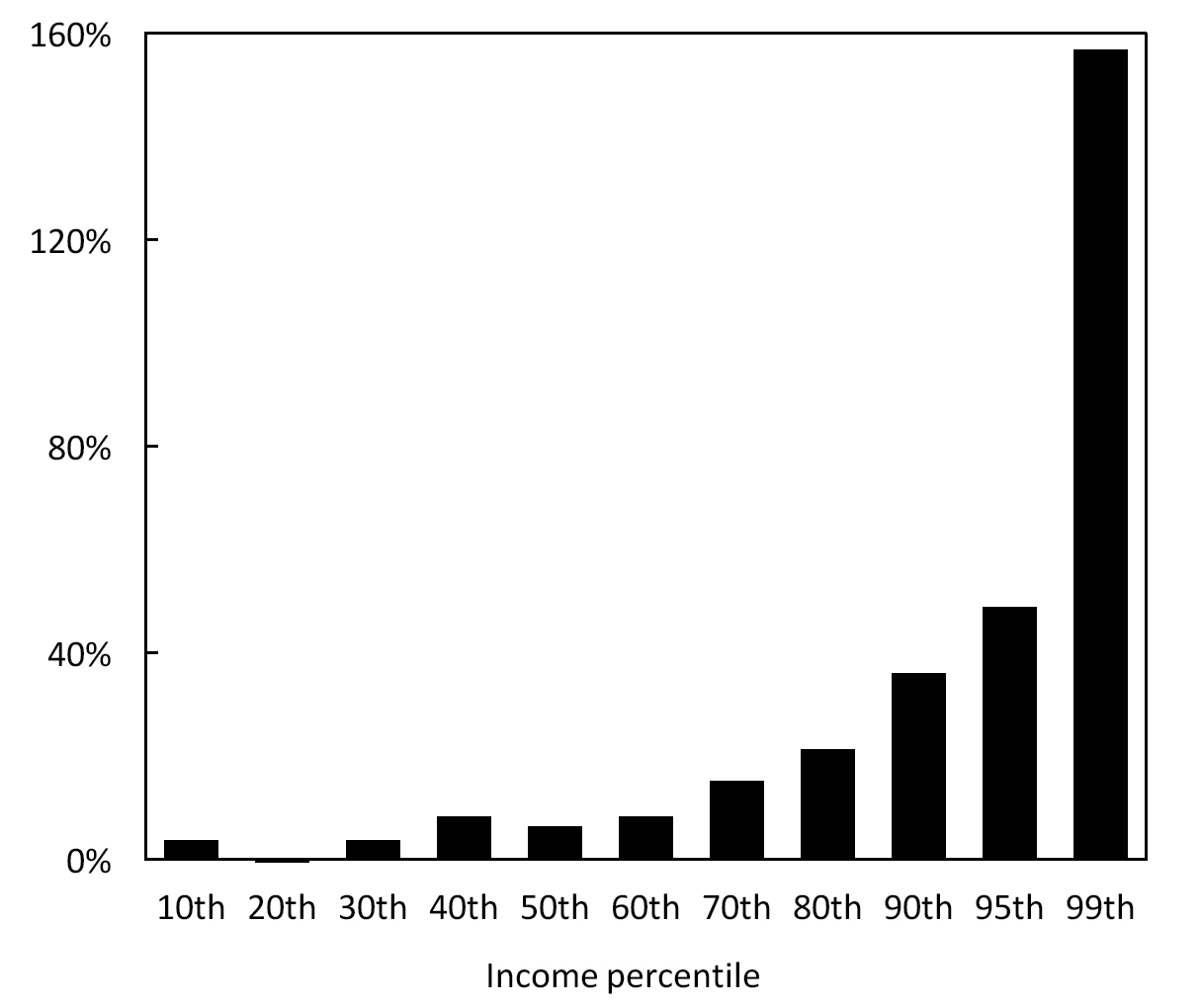

Figure 9.5 is a stunner. It displays the cumulative increases in real hourly wage rates between 1980 and 2015 at various points in the wage distribution. The shape of the graph is disturbing. The lower 60 percent of the working population (the first six bars) garnered only meager real wage gains—in all cases, less than 9 percent over thirty-five years. Even at the 90 percent percentile, real wage gains averaged only about 1 percent per annum. But workers at the ninety-ninth percentile (the rightmost bar) did fabulously well.* Numbers like these depict a national tragedy. The Age of Inequality has left almost all working people behind.

FIGURE 9.5 Real Wage Growth by Income Percentile, 1980–2015

Source: Economic Policy Institute (epi.org/data/#?preset=wage-percentiles).

Why? Harsher Labor Markets

Enough data; you get the point. Why in the world did this happen? Economists have written tons of research papers—literally, I think, if you put them all on a scale—on the causes of rising inequality in the United States. An extremely short summary of all that research is that changes in the labor market—who gets paid how much for doing what—did it.

Specifically, almost all researchers agree that the most important factor by far has been what is sometimes called the race between education and technology. Many people forget about the first contestant in that important race (education) and concentrate on the second. They note that skills in the middle and bottom rungs of the US labor force have failed to keep pace with rapidly advancing technology. If technological change favors highly educated workers over poorly educated ones, as it surely has in recent decades, then we expect wages near the top to rise faster than wages near the bottom, thereby opening up wider and wider wage gaps. Which is exactly what happened.

But let’s not forget the other contestant in the race: education. Many people are surprised to learn that what was once a huge American advantage in international competition—our highly educated workforce—is no longer an advantage. Rather, we’ve dropped back into the middle of the pack and are in danger of slipping even further behind the leaders. There are many ways to look at this phenomenon, none of which paints a pretty picture. If we compare US adults with those of other countries, we find that our college completion rates, once the envy of the world, now rank us behind such countries as Spain, Slovenia, and Russia. If we look at what students actually learn in school, as measured by the latest Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests of high school students, the United States ranked fortieth in the world in math literacy, twenty-fifth in science literacy, and twenty-fourth in reading literacy. I could go on.

Now apply some rudimentary economic analysis to the two-contestant race. Suppose rapidly improving technology boosts the demand for highly educated labor, relative to that for poorly educated labor. And suppose further that the school system fails to keep pace, so the supply of highly educated labor doesn’t keep pace. Highly educated labor then becomes relatively scarcer, and markets naturally bid up its price. We would then expect wages near the top of the educational ladder to race ahead of wages near the bottom, which is exactly what US data so vividly show.* In 1983, the average college graduate earned 49 percent more than the average high school graduate—a hefty pay gap, to be sure, but not quite like living on different planets. By 2013, that margin had soared to a mind-blowing 83 percent.

So education lost the race to technology. But that’s not the whole story. Some additional inequality can be laid at the doorstep of the dramatic decline in unionization, which fell from 20 percent of all employed workers in 1983 (and was once much higher) to just 11 percent in 2015. Muscular unions once extracted higher wages from employers. But muscular unions are hard to find these days. Indeed, outside the government sector, it’s getting increasingly hard to find unions at all. Across the entire private sector, unionization is down to a paltry 6.7 percent of workers—just one worker in sixteen.

Another piece of the inequality puzzle stems from international competition, which we discussed at length in the previous chapter. Here’s an astounding fact. Taken together, the rise of China, the awakening of India, and the collapse of the Soviet Union essentially doubled the world economy’s effective labor force over a period of a decade or two while bringing in little usable capital. You don’t have to be an economist to understand that a huge increase in the world’s supply of labor thrust American and Western European workers, especially less skilled workers, into a much tougher competitive environment. Capital, on the other hand, benefited from its relative scarcity. No wonder profits fared better than wages and high wages fared better than low wages.

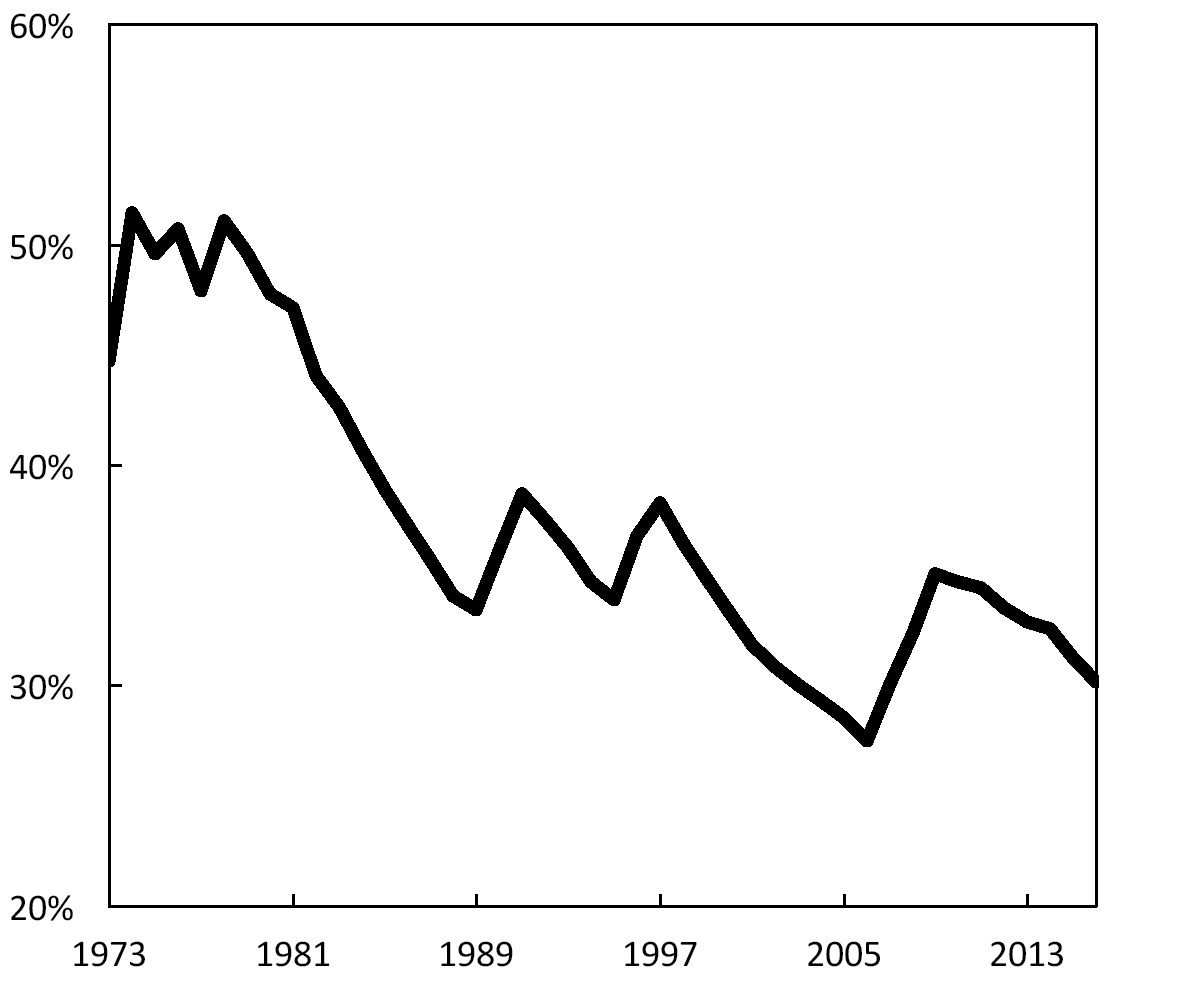

A third factor leading to increased inequality, especially at and near the bottom of the US wage ladder, is the sagging minimum wage. Figure 9.6 shows that the federal minimum wage fell from 50 percent of the average wage in 1978 to barely over 30 percent by 2015. (Many states have minimum wages above the federal minimum wage.) Had the national minimum wage remained at half the average wage, it would be over $11 per hour today.

Finally, let me mention a possible factor that economists hesitate to talk about because we can neither measure it nor even define it precisely: the breakdown of the previous social contract between labor and capital. Virtually every profitable business generates a little surplus here and there—company revenue that exceeds what the firm must pay to attract the labor, capital, and other factors of production it needs. In the “good old days” of the 1950s and 1960s, management used to share some of this largesse with its workers, perhaps by paying wages above what the market demanded or by granting employees generous fringe benefits. A bit of corporate paternalism was the norm then. Today, it’s closer to devil take the hindmost.

FIGURE 9.6 Federal Minimum Wage as a Percentage of Average Hourly Wage, 1973–2016

Source: US Department of Labor; Economic Policy Institute.

What happened? One major development was the shareholder value revolution, which glorified the idea that every dollar of surplus belongs to the shareholders. The one and only proper goal of the corporation, according to many academic economists and practitioners, is to maximize the company’s stock market value. Giving any of the surplus to workers interferes with achieving that goal. Thus did kinder, gentler capitalism give way to meaner, tougher capitalism—to the detriment of American workers. The latest manifestation of this phenomenon is the so-called gig economy, in which workers receive virtually no fringe benefits and corporate paternalism is pretty much unknown.

I believe that story, as do some other economists. The problem is that we believers cannot prove our case either theoretically or, more important, statistically. And in economics, what cannot be measured and demonstrated with data might as well not exist. (That’s not so in politics. Remember, they are two different civilizations.) The social contract theory of rising inequality may or may not be true, but we have no way to put a number on it.

Or do we? One highly imperfect measure of the dominance of shareholder value over corporate paternalism is the ratio of CEO pay to average wages. After all, those sky-high CEO compensation packages are dominated by bountiful stock options and the like, not by high hourly wages. The idea was that paying top executives in stock options would align their interests with those of the shareholders. Data compiled by the Economic Policy Institute show that CEO pay at America’s 350 largest firms rose from 30 times the compensation of their average workers in 1978 to 276 times in 2015. Do we really believe that CEOs became almost ten times more valuable, relative to ordinary workers, over those years?

Then Tax Policy Piled On

So markets turned ferociously against labor, especially against low-skilled and manufacturing labor, during the Age of Inequality. That’s most of the story. But perhaps the saddest part is what came next, when the US government, unlike most other governments around the world, decided to pile on with regressive tax policies that cut taxes for the richest Americans, rather than try to limit inequality’s rise. In a football game, such nasty behavior would be flagged as unnecessary roughness and penalized fifteen yards.

The tax part of the story starts with Ronald Reagan. In fairness, no one in 1981 knew that market-based income inequality would rise for the next thirty-five years or so. So don’t blame Reagan for gratuitous cruelty to labor. Nonetheless, the income tax cuts he pushed through Congress were decidedly regressive. Some of this regressivity was reversed under Bill Clinton, who, for example, raised the top income tax rate and increased the Earned Income Tax Credit drastically. But Clinton was followed by George W. Bush, and another huge round of tax cuts tilted strongly toward the rich. Once again, Barack Obama took a lot of this back with tax hikes on the rich and other equalizing measures like Obamacare. But he was followed by Donald Trump, who failed to undo Obamacare but pushed through one of the most regressive tax cuts in American history in 2017.

Add all this up, and you are forced to conclude that the tax policies of the US government joined hands with the anonymous but powerful forces of the market to push income inequality higher.

But wait. Taxes are only one of two pieces of the tax-and-transfer system that transforms market-based incomes that people earn into the net disposable incomes they live on. Taxes are taken out, but transfers get added back in. Needy Americans receive payments from such programs as Social Security, unemployment insurance, food stamps, Medicaid, housing subsidies, and more. Presidents Reagan, Bush, and Trump all railed against what is colloquially called “the welfare state.” Perhaps because of congressional resistance, their barks were far worse than their bites. Nonetheless, there were some bites.

You have no doubt noticed that each of these attacks on the social safety net was mounted by a Republican administration. Democrats have been cast as the party either defending the safety net or seeking to expand it. This is not a selective reading of history.* Not only is it accurate to portray Democrats as friendlier to the poor and near-poor than Republicans, but the difference goes beyond attitudes: the data clearly show that income inequality rises under Republican presidents and falls under Democrats.

Now add up all the federal government action on taxes and transfers over periods of both Democratic and Republican control, and stir the pot. What do you get? According to a comprehensive CBO study, the tax-and-transfer policies of the federal government reduced income inequality by almost exactly the same amount in 2013 (the final year of their study) as in 1979. Thus over the Age of Inequality, the free market turned ferociously against low- and moderate-income Americans, and the federal government basically sat back and let it happen.

The Tradeoff Between Equality and Efficiency Revisited

Could the US government have helped more? Could it have battled back against the powerful market forces that were pushing inequality up? Certainly, though at some cost. And it might not have won the battle.

I mentioned several chapters ago that economists generally believe there is a tradeoff between equality and efficiency. Society can deploy such tools as progressive taxation, more generous transfer programs, and higher minimum wages to reduce inequality. But each takes a toll—even if a small one—on economic efficiency by dulling incentives. That annoying side effect is pretty much inherent in the idea of using taxes and transfers to redistribute income. The market dishes out highly unequal rewards, based on each person’s success or failure in the economic game. If the government increases taxes on the rich, it diminishes the rewards for success. If it provides more generous benefits to the poor, the jobless, or the homeless, it diminishes the penalty for failure. So, as in the well-worn metaphor, as you cut the pie more equally, you probably also shrink it.

For those who live near the bottom of the income distribution, a larger slice of a smaller pie is a good deal. But if you live near the top, a smaller slice of a smaller pie holds far less appeal. For this obvious reason, political wars over redistribution often pit rich versus poor, with the rich, or rather their lobbyists and sympathetic politicians, not mounting the Gordon Gekko defense (“greed is good”), but rather arguing that higher taxes and more generous transfer payments damage economic efficiency.

Do they? Almost certainly yes, though the damages are frequently exaggerated. Neither the advent of the progressive income tax in 1913 nor the New Deal in the 1930s ended capitalism as we know it—despite the jeremiads of the times. The US economy also did very nicely, thank you, during the Eisenhower and Kennedy years, despite top marginal tax rates above 90 percent. Indeed, statistical evidence that the US economy grows faster when income tax rates are lower is sorely lacking—despite the confident claims of Presidents Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump. (More on this in the next chapter.)

That said, no economist argues that incentives don’t matter, and having a social safety net certainly dulls them. Workers covered by unemployment insurance are a bit fussier about taking the first job that comes along. Businesses invest less when the returns on investment are taxed more heavily. Taxpayers bend themselves into proverbial pretzels to take advantage of tax loopholes. Each of these actions takes a toll on efficiency.

So what do you do if you find current levels of inequality intolerable—or at least undesirable? (Remember, not everyone does.) The tradeoff teaches us three main lessons.

First, if society decides to deploy the power of the state to reduce inequality, it should concentrate on redistributive policies that do the least harm to economic efficiency. If there was any bipartisanship left in America, this lesson would command broad bipartisan support. It’s one place where more economic illumination could do a lot of good.

Second, redistributive tools should generally be used in moderation. There is a reason why socialist economies like Cuba’s and North Korea’s look economically lifeless; incentives have been dulled to the point where they barely exist. These are extreme examples, to be sure. Closer to home, the 90 percent income tax rates of the 1950s and 1960s were probably too high, even though Americans of the day adapted to them. So is a $15 national minimum wage. (In Mississippi, the average wage is just $18. Think about it.) Besides, this is America, not France or Denmark. Compared to Europe, the political appetite for redistribution here is limited. Republicans understand this better than Democrats.

Third, the US government probably doesn’t have enough firepower to beat back powerful market forces pushing toward greater inequality. So it’s unlikely that even determined government action could have turned the Age of Inequality into an Age of Equality. But liberals think it would have been nice to have tried; we could at least have made a bad situation somewhat less devastating. Democrats understand this better than Republicans.

With these three broad lessons in mind, let’s get more specific. Where might more illumination about redistribution actually take us? And would American politics go there?

For openers, consider the following important principle of taxation: it is harder to raise taxes on mobile factors of production than on immobile factors—whether “mobility” refers to geography, industry, or type of economic activity. Thus, for example, high geographical mobility makes it hard for city governments in liberal bastions like San Francisco and New York City to redistribute income too much. Rich people facing high tax rates can (and will) move out, eroding the city’s tax base. Poor people offered generous benefits can (and will) move in, ballooning the cost of the city’s generosity. It is therefore more sensible to assign the job of redistribution to the federal government because people are far less likely to change countries than to change cities.

A second doleful application of the same mobility principle is to the relative taxation of labor versus capital. The rich own almost all the capital; that’s why we call them rich. So egalitarians often favor higher taxes on interest, dividends, and capital gains. It makes sense. But watch out; here’s where illumination can help. The distressing reality is that capital is far more mobile than labor. So if a country—not to mention a state or a city—tries to tax capital more heavily, money may simply flee to a kinder jurisdiction. Moving is harder for labor. So while concern for equality calls for higher taxes on capital, recognition of efficiency costs may call for lower ones. There is indeed a tradeoff.

What Policy Can Do: The Social Safety Net

That said, every Western democracy tempers raw, free-market capitalism with some sort of safety net that employs progressive taxes and transfer payments, among other tools, to mitigate inequality. Not all safety nets are created equal, however. And too few Americans, it seems, realize that ours is thin by international standards.

How thin? To make comparisons across countries, I turn to data compiled by the OECD, focusing on the United States and eight other advanced nations—our peer group, so to speak. Using the Gini coefficient to measure inequality, the top line of Table 9.1 shows that all taxes and transfer payments, taken together, reduced income inequality by 22 percent in the United States. Is that a lot or a little? Well, judge for yourself, but every other nation in this table did more redistribution. By this metric, the US government stands out as providing the weakest safety net.

Whether that’s something to be proud of or ashamed of is a matter of opinion. To soft-hearted believers in the principle of equity, it’s a source of shame. America looks mean-spirited toward its poor. To hard-headed believers in noninterventionist government and the principle of efficiency, it’s a source of pride. It means we interfere less with market outcomes. Judging by the battles that frequently roil American politics, Americans seem pretty divided on whether more redistribution would be a good thing or a bad thing. For example, since 1998 the Gallup poll has been asking Americans intermittently whether taxes on the rich should be increased for the purpose of redistribution. The country is almost evenly divided on this question. Many of us prize equality of opportunity—even if it’s a myth—over equality of outcomes.

TABLE 9.1 Government Redistribution in Nine Countries

Country: United States

Gini Coefficient Before Taxes and Transfers: .508

Gini Coefficient After Taxes and Transfers: .394

Percent Change: –22%

Country: Canada

Gini Coefficient Before Taxes and Transfers: .440

Gini Coefficient After Taxes and Transfers: .322

Percent Change: –27%

Country: Australia

Gini Coefficient Before Taxes and Transfers: .483

Gini Coefficient After Taxes and Transfers: .337

Percent Change: –30%

Country: Japan

Gini Coefficient Before Taxes and Transfers: .488

Gini Coefficient After Taxes and Transfers: .330

Percent Change: –32%

Country: United Kingdom

Gini Coefficient Before Taxes and Transfers: .527

Gini Coefficient After Taxes and Transfers: .358

Percent Change: –32%

Country: Sweden

Gini Coefficient Before Taxes and Transfers: .443

Gini Coefficient After Taxes and Transfers: .281

Percent Change: –37%

Country: France

Gini Coefficient Before Taxes and Transfers: .504

Gini Coefficient After Taxes and Transfers: .294

Percent Change: –42%

Country: Denmark

Gini Coefficient Before Taxes and Transfers: .442

Gini Coefficient After Taxes and Transfers: .254

Percent Change: –43%

Country: Germany

Gini Coefficient Before Taxes and Transfers: .508

Gini Coefficient After Taxes and Transfers: .292

Percent Change: –43%

Source: Author’s calculations based on OECD data.

What, concretely, does a thinner safety net look like? After all, no country practices social Darwinism. While the orderings are not identical, as you move down the list of nations in Table 9.1, you generally find countries with more progressive tax systems, higher taxes in general, and more generous social welfare programs to support the poor and near-poor.

The United States and Germany offer a convenient case study because, by sheer coincidence, the two countries displayed exactly the same amount of inequality in market incomes that year. The level of inequality generated by a country’s markets depends on myriad factors, and the US and German economies differ in numerous ways. Yet somehow, when all the dust settled, markets in the two countries dished out precisely the same degree of inequality—to three decimal places! (As Table 9.1 shows, the Gini coefficient in each country was 0.508.)

But that’s before the two governments got into the act with redistributive taxes and transfer programs. Once taxes were taken out and transfers added in, Germany’s after-tax (and transfers) Gini coefficient dropped all the way to 0.292, but ours fell only to 0.394. That huge difference stemmed from different government policies, not from different market outcomes. Like most Western European democracies, Germany has a thick social safety net for its workers, unlike anything we have ever seriously considered in the United States. Germans, for example, take universal health insurance for granted and, should they need it, receive unemployment benefits for up to two years. In a word, the United States is kinder to its rich—the government lets them keep more of their money—and Germany is kinder to its poor.

At this point, readers with an egalitarian bent may start jumping to a premature conclusion: the US should emulate Germany by thickening its social safety net and making its tax system more progressive. After all, other rich European countries have lived that way for years and seem to have prospered.

Hmm. But first let’s remember that average market incomes are higher in the United States than in Germany—and after-tax disposable incomes are higher yet because the tax burden is smaller here. Yes, Americans are richer than Germans on average, and part of the reason is that we allow free markets a freer hand.

Second, American attitudes toward redistribution by government fiat differ from the attitudes that characterize most other Western democracies. The Declaration of Independence may have declared that “all men are created equal,” but its main author kept slaves and believed “that government is best which governs least.”* Forget the eighteenth century, and jump to the twenty-first. Modern Americans appear not to be a very equality-loving people by first-world standards. I guess it’s part of American exceptionalism. The amount of inequality a country gets depends critically on its citizens’ value judgments, as voiced through their political representatives. Let’s face it. The United States is a high-inequality country partly because we’re content to be a high-inequality country.

But wait. Suppose our politicians paid closer attention to the principles of equity and efficiency and accepted a bit more illumination from economics. Maybe then the American government would design more efficient redistributive mechanisms. According to Table 9.1, we now use the tax-transfer system to reduce inequality by 22 percent. Suppose doing so costs us X percent of GDP in terms of lost efficiency. What if sounder policy choices could reduce that cost to, say, half that amount? Would we then “buy” more equality? No one can know for sure, but I’d like to think the answer is yes.

What Policy Can Do: Market Wages

When it comes to income inequality, however, markets are far more important than government redistributive policies. If natural developments in labor markets increase wage disparities by large amounts, as has happened in recent decades, governments will almost certainly be unable to reverse the trend toward greater inequality by using progressive taxes and transfers. In Germany, for example, inequality in market-based incomes rose (by the Gini measure) from 0.429 in 1990 to 0.508 in 2013.

Furthermore, the “losers” may not welcome the types of governmental assistance that economists typically recommend. Nobel Prize–winning economist Robert Shiller put it this way, in explaining Donald Trump’s appeal to the working class:

Those on the downside of rising economic inequality generally do not want government policies that look like handouts. They typically do not want the government to make the tax system more progressive, to impose punishing taxes on the rich, in order to give the money to them. Redistribution feels demeaning. It feels like being labeled a failure.…

The desperately poor may accept handouts, because they feel they have to. For those who consider themselves at least middle class, however, anything that smacks of a handout is not desired. Instead, they want their economic power back. They want to be in control of their economic lives.

Perhaps. But there may also be an important asymmetry. Potential recipients of public benefits such as Trade Adjustment Assistance, unemployment insurance, or food stamps may be less than eager to acquire them, seeing receipt as stigmatizing. But once actual recipients are collecting such benefits, they may feel sorely aggrieved if the monies are taken away. They will certainly be poorer.

That said, Shiller’s claim that people greatly prefer dignity and a job to dependency and the dole is probably both true and important. Unfortunately, applying this notion to policies that would mitigate inequality is no mean trick. It involves, among other things, changing labor market outcomes—something the US government has traditionally been loath to do.

Yes, we have a minimum wage that sets a wage floor that businesses may not breach. That’s not a handout; it’s something earned by working. But the federal minimum wage now stands at a meager $7.25 per hour, so few firms would want to breach it anyway. (Many states and a few cities set higher minimums.) Similarly, the Fair Labor Standards Act currently decrees that employees earning under about $24,000 a year must be paid extra for overtime work. Again, that additional income is earned, not given. But such a low-income cutoff covers only about 7 percent of full-time salaried workers—compared to 62 percent when it was set in 1975.* Once a worker gets above such low thresholds, the US government basically leaves wage setting to the market.

Sadly, in recent decades market forces have pushed toward greater inequality. As mentioned earlier, the rise of China, the awakening of India, and the fall of the Soviet Union—three powerful disequalizing forces—tilted the playing field strongly against labor and in favor of capital. Those same forces also produced greater inequality within the distribution of wages by hurting low-skilled workers while helping (at least some) highly skilled workers.

The upward march of technology—a force vastly stronger than international trade—has had similar effects. The Luddites have been proven wrong time and time again: automation did not make jobs disappear. But they might have been right if they had concentrated on relative wages instead. Certainly in recent decades, technological advances have improved the job market prospects of highly skilled workers, especially college-educated workers, while creating a hostile environment for low-skilled workers. Like globalization, technology has been a force for greater inequality.

As noted, the US government has barely even tried to counteract these powerful market trends. Could it have done more? I think so.

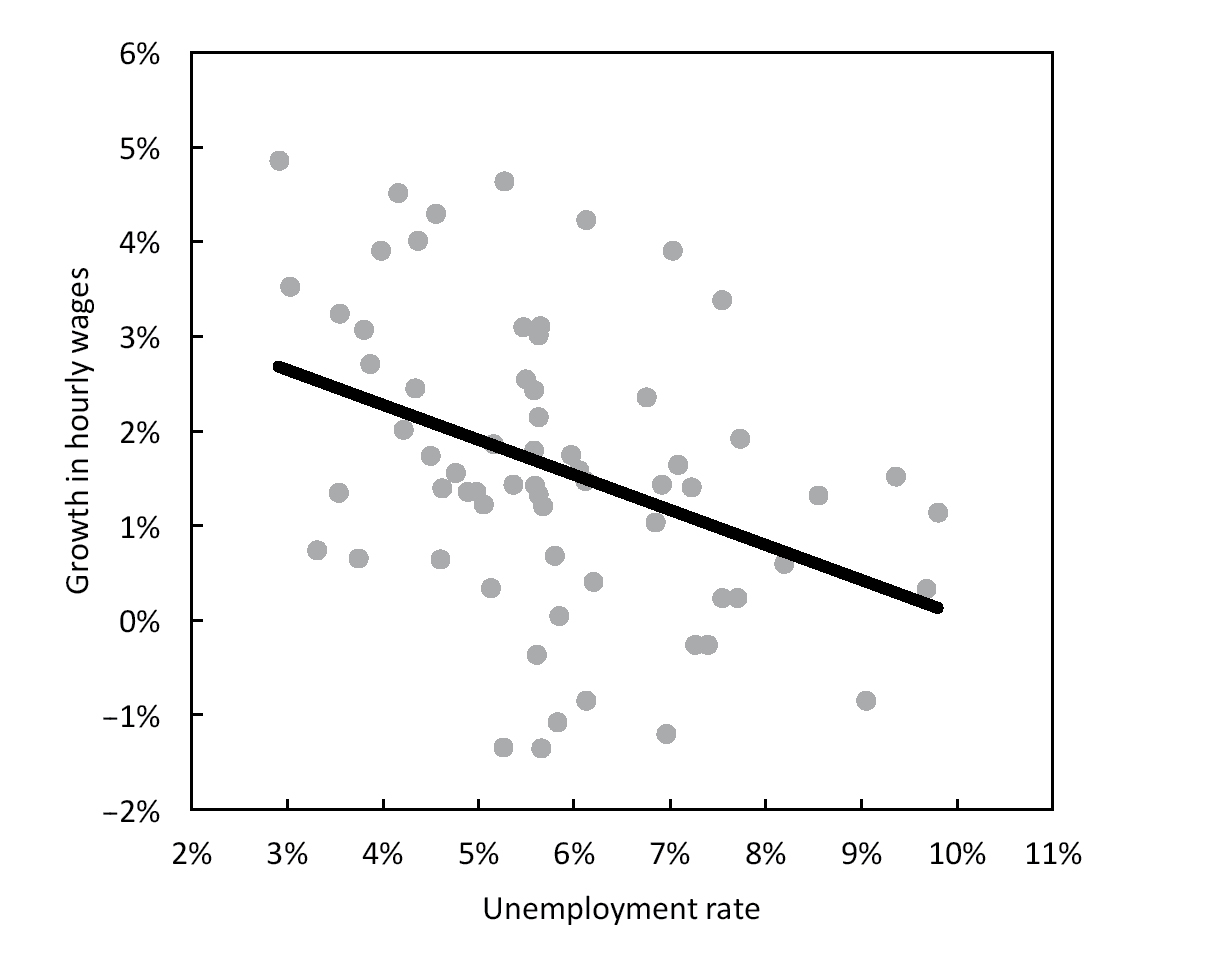

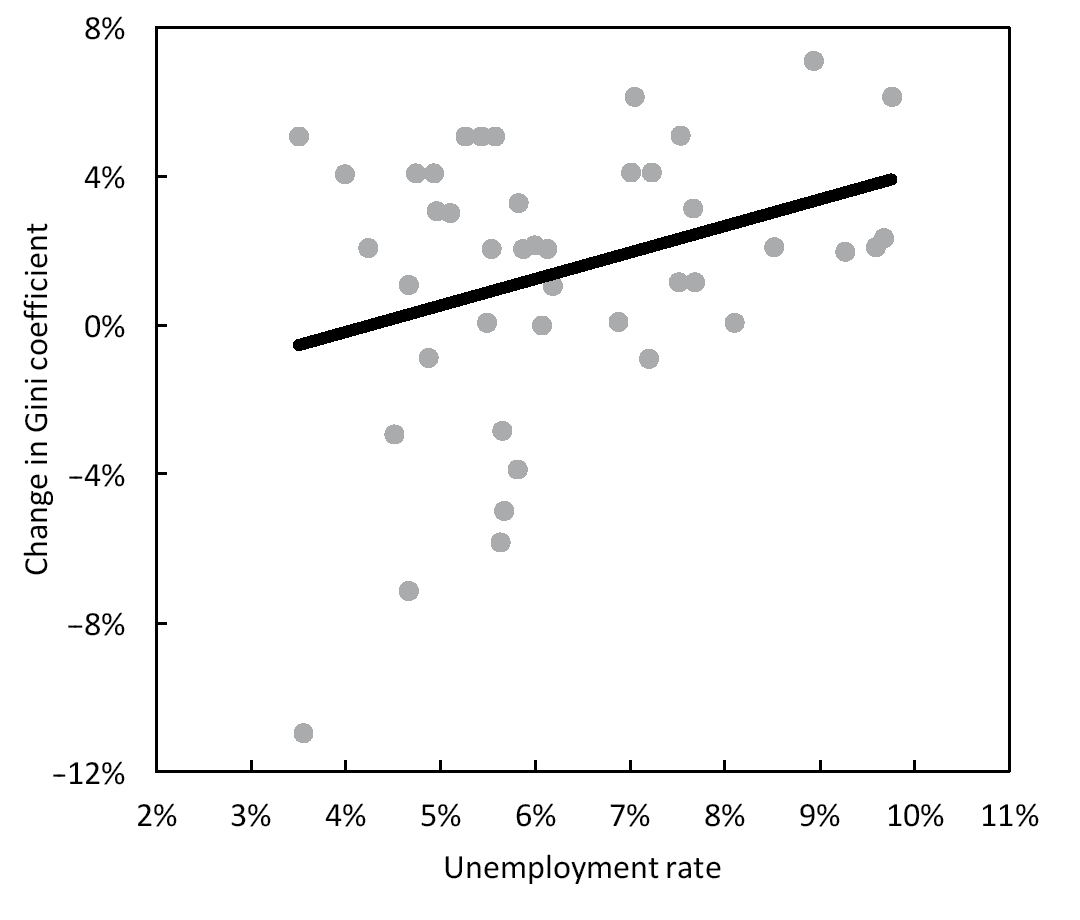

For openers, strong evidence supports the unsurprising hypothesis that tight labor markets reduce wage inequality while slack labor markets exacerbate it. Look at the two scatter plots in Figures 9.7 and 9.8. The upper panel shows that real wages grow faster when unemployment is low and slower when unemployment is high. You might have guessed that! The lower panel shows that wage inequality (measured, again, by the Gini coefficient) is lower when the unemployment rate is lower and higher when the unemployment rate is higher. Put those two findings together, and you have this conclusion: tight labor markets benefit labor as a whole and especially low-wage labor. Tight labor markets are medicine against inequality.

How have we been doing on this score? Quite well, if you look only at very recent years, but not so well if you look back a bit further. Over the period from January 2015 through June 2017, the national unemployment rate averaged 5 percent. You can call that “full employment,” or at least a reasonable facsimile thereof. But now consider the years during and after the Great Recession, 2009–2014. The unemployment rate averaged 8.2 percent over that six-year period, a high rate that both held back wage growth and exacerbated inequality. While inequality is not uppermost in the minds of Federal Reserve officials when they make monetary policy, nor of members of Congress when they make fiscal policy, running a high-pressure economy is probably the government’s single most powerful weapon for reducing inequality. Recessions breed inequality like stagnant water breeds mosquitos.

FIGURE 9.7 Real Wage Growth and Unemployment, 1948–2013

FIGURE 9.8 Wage Inequality and Unemployment, 1968–2012

Figure 9.7 shows changes in inflation-adjusted compensation per hour and the unemployment rate between 1948 and 2013. Figure 9.8 shows changes in the Gini coefficient and the unemployment rate between 1968 and 2012. Source: Alan S. Blinder, “Petrified Paychecks,” Washington Monthly (November/December 2014): 29–34.

But there is also a long list of other, albeit weaker or slower-acting policies the government could pursue if it really wanted to reduce wage inequality. Here are a few:

A higher minimum wage. Raising the minimum wage obviously puts more money into the pockets of the lowest-paid workers—as long as they don’t lose their jobs. Conservatives have long resisted higher minimum wages both because they intrude on the prerogatives of business and because they allegedly kill jobs. The scholarly evidence refutes the claim of large-scale job loss—at least for modest minimum wage increases. But all bets are off for the more-than-doubling of the federal minimum wage that some people proposed in 2016.

More profit sharing. Though it’s largely an unknown story, many US companies pay a share of their profits—normally a small share—to their workers as a wage supplement. Many others do not, however. Should the government encourage more companies to share profits, perhaps by providing tax incentives for so doing? That would certainly interfere with free markets; as things stand today, every firm decides for itself. But perhaps surprisingly, this particular interference with market outcomes might not violate the principle of efficiency—or at least not violate it much. Why not? Because research shows that profit-sharing firms get better performance from their workers in return. So firms reap a productivity dividend that offsets part or all of their higher labor costs.

The upshot is that a little nudge from the government might lead to more efficiency, not less. Such a nudge would not be difficult to provide. Here’s one simple idea: amend the tax law so that corporations may deduct the high-powered incentive pay they offer to top executives only if they offer incentive plans to all their workers. (If you must know, it’s Section 162[m] of the tax code.) I guarantee you that will get the CEO’s attention.

Strengthening unions. Declining unionization has been one factor holding down wages. And intermittent hostility from government has been one reason behind that decline since President Reagan broke the back of the air traffic controllers’ union in 1981. George W. Bush’s appointees to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) were decidedly less friendly toward organized labor than Bill Clinton’s or Barack Obama’s, and Republican intransigence left two NLRB seats open when Donald Trump moved into the White House. He quickly named Philip Miscimarra, a lawyer with extensive experience representing management against labor, as the new NLRB chair. If the US government wanted to take a stand against rising inequality, rather than piling on, it could switch sides and start helping unions win wage gains, rather than undermining them. Good luck with that in this administration.

Vocational training and apprenticeships. Our comparatively free labor markets place the United States near the bottom of the league tables in both apprenticeships and vocational training. Here’s one set of shocking statistics: the United States has just 0.2 percent of its labor force in formal apprenticeship programs, compared to 2.2 percent in Canada, and 3.7 percent in Australia. Canadians and Aussies seem a lot like Americans. Why can’t we do as many apprenticeships as they do? In 2017, President Trump proposed that we up our game here. Americans are also light-years behind such world leaders as Germany in providing vocational education to students who are not bound for college, even though the prospective income gains for people trained to be, say, plumbers, electricians, or carpenters are quite high. (Have you tried to get one to your house lately?)

The United States can and should provide much more apprenticeships and vocational training, each of which can open the door to well-paid jobs for non–college-educated workers. Instead, we seem bent on ignoring the experience of other nations and leaving ourselves trapped in a situation in which the government thinks businesses should do it and businesses think the government should. It would be better if both would.

Occupational licensure. You probably wouldn’t want to be treated by a doctor who is not licensed to practice medicine. You may also prefer a licensed electrician when you need work done in your house. But what about the locksmith who makes new keys, the stylist who does your hair, and the truck driver who delivers packages? Must they be licensed too? Here’s a stunning fact that few people know: in the early 1950s, fewer than 5 percent of US workers were required to have a license; by 2008, that share had risen to almost 29 percent. Was that sixfold increase really warranted by mounting health and safety concerns, the considerations typically used to rationalize licensing requirements? Or might it echo the medieval guild system—erecting barriers to keep people out of certain lines of work? Many economists think it has strong elements of the latter, and that less licensure would open up more opportunities, especially for non–college-educated labor.

K-12 education. Taking a longer and broader view, the now-creaky American education system was once the envy of the world—and one of the main nonsecrets of our fabulous economic success. In the nineteenth century, the United States created “universal” primary education—a revolutionary idea at the time. Then we started graduating record numbers of teenagers from high school and eventually sending unheard-of numbers to college. No other major country came close. Today, however, the education levels of America’s workforce no longer give us a leg up on the competition. We’re mediocre at best.

This is not the place for a lengthy disquisition on what’s wrong with K-12 education in the United States, nor am I the right person to offer it. Suffice it to say that the agenda is lengthy and goes way beyond just spending more money. But one important point is vital in the present context: for the K-12 education system to help us reduce inequality, we must focus a disproportionate share of any incremental resources on the poor and middle classes. The private market doesn’t do this so well. Government has to take the lead.

Pre-K education. I have saved what may be the most important education policy for last, mainly because society must wait almost a generation to see it bear fruit. Many kids from lower-income backgrounds do not receive high-quality pre-K education—and that puts them at a distinct disadvantage relative to richer kids, who do. While not entirely unequivocal, the weight of the evidence suggests that this disadvantage is large and long-lasting. For example, several studies have found that poor children put through high-quality educational programs at age three or four subsequently perform better in school and drop out less. As adults, they commit fewer crimes and earn higher incomes.

A comprehensive report by the President’s Council of Economic Advisers in 2014 estimated that each dollar invested in early learning programs eventually returns about $8.60 to society, roughly half of which comes from higher earnings as adults. Some think that estimate is too high. But even if the benefits are only half as large, pre-K is still an outstanding investment. How many for-profit businesses return four times the original investment? But here’s the rub. While investment in pre-K education pays rich dividends, most poor people cannot afford to make it—which is why government should step in. The question for Congress and state legislators needs to change from “How can we afford it?” to “How can we afford not to do it?” And it’s not very expensive. Pre-K teachers do not cost much.

Why Doesn’t Policy Do More?

So while there is no magic bullet, there is a long list of ways in which public policy could chip away at the inequality problem. And some of them would hold broad, bipartisan appeal if there was any bipartisanship left in America. Why, then, hasn’t the US government tried harder to reduce inequality? Here, I think, the economic reasons are relatively unimportant, while the political reasons are crucial.

But let’s start with the economics—in particular, with the nagging tradeoff between equality and efficiency, a lesson we may have learned too well. Since most policies that reduce inequality also reduce efficiency, many people seem to have concluded that the game is not worth the candle. “Let’s not try to redistribute income,” the reasoning goes, “for it might hurt our fragile market economy.” But the right lesson is that we should pursue greater equality in the most efficient ways. The tradeoff creates a speed bump, not a wall.

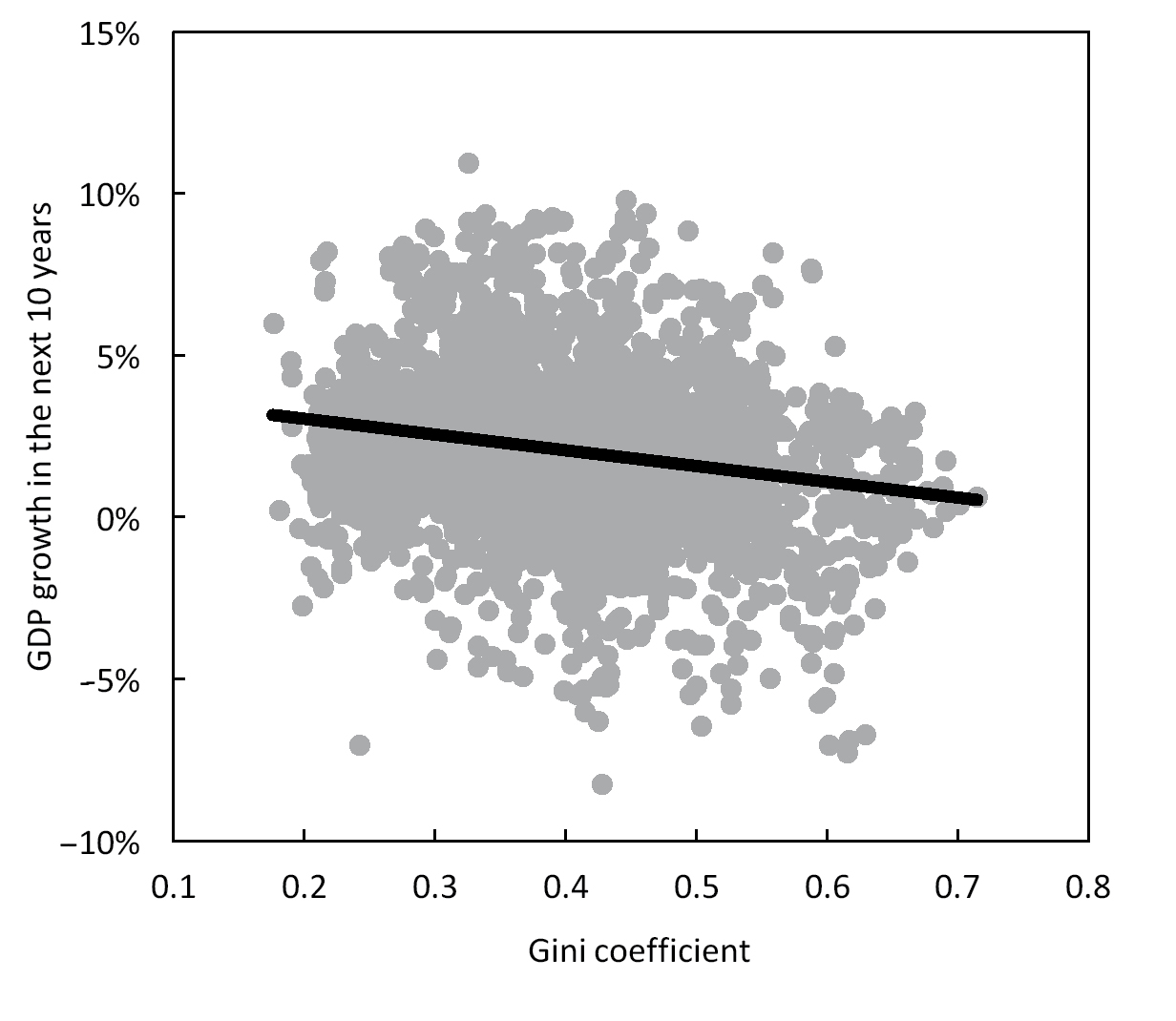

Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that it’s a mistake to apply the tradeoff idea to economic growth (how fast does the pie grow?) as opposed to economic efficiency (how big is the pie today?). While scholarly debate continues, the preponderance of evidence to date—and there’s a lot of it—suggests that higher inequality may actually retard, rather than promote, growth.

Figure 9.9, which comes from an International Monetary Fund study, is just one example among many I could show. It displays a modest negative statistical association between a country’s inequality of net income (after taxes and transfers) and its GDP growth over the following decade, using all available data from 153 countries over the period 1960–2010. No, don’t jump to the conclusion that greater equality is a sure path to faster growth. The correlation is weak, as you can see. My point is simply that it’s not possible to find a positive relationship in these data. Higher inequality does not lead to faster growth.

How can this be, in view of standard incentive arguments? In extreme cases, the answer is obvious: workers so poor that they’re undernourished aren’t productive. But that observation can’t be terribly relevant to the contemporary United States or other rich countries. Yes, low-income Americans are poor by first-world standards, but few of them are starving. Rather, the main problem in the rich countries seems to be that low-income families cannot avail themselves of the educational opportunities that would make their children more productive as workers. So the poor and near-poor build less human capital, and in consequence both they and the economy suffer.

FIGURE 9.9 The Correlation Between Inequality and Growth

Growth rates are from the Penn World Tables, and Gini coefficients are from Frederick Solt’s Standardized World Income Inequality Database. Source: Jonathan Ostry, Andrew Berg, and Charalambos Tsangarides, “Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth,” Staff Discussion Note, International Monetary Fund, February 2014, 16.

If inadequate education within, say, the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution is the essence of the problem, the remedies are clear. Economics, having pointed the way, can step aside and let the political system find the will. Sadly, there are good reasons to think it won’t do so. If you’ve read this far, you know most of them, so I’ll be brief.

First, political decision making in America is highly partisan, and the currently dominant party systematically opposes virtually every policy that would reduce inequality, whether it’s Medicaid, food stamps, “welfare,” or whatever. In fact, Republican proposals from health care to budgets to tax reform actively seek to widen inequalities. Remember Speaker Paul Ryan’s concern that our tattered social safety net might provide an alluring “hammock” for the lazy and indolent. Or perhaps you recall Wall Street Journal editorials some years ago that labeled people too poor to pay federal income taxes the “lucky duckies.” How lucky to be so poor!

Those political attitudes were not changed by Donald Trump’s “working man” rhetoric in the 2016 campaign. On the contrary, the new administration embraced congressional Republicans’ regressive health care bills, offered an amazingly regressive set of budget cuts that would have eviscerated the social safety net, and proposed an even more amazingly regressive tax plan that feathered the richest nests. Fortunately for America’s working class, only a little of this agenda made it through Congress.

Second, money talks in American politics—loudly. And money does not normally speak out in favor of redistribution. That the rich have a disproportionate influence on political decisions is obvious to everyone and extends well beyond the realm of redistribution to almost all facets of American political life. Political scientist Martin Gilens has found, for example, that the opinions of people in the middle of the income distribution count for naught in terms of whether or not a particular policy becomes law. The opinions of those at the ninetieth percentile, by contrast, have a strong influence. Shocked? I didn’t think so.

Third, redistribution in America has long labored under the burden of racial attitudes. Experts are fond of pointing out that more poor people are white than black. It’s true. In 2015, for example, poor whites outnumbered poor blacks by almost three to one. But that’s mainly because whites outnumbered blacks by about six to one in the general population. Poverty rates tell a different, and racially tinged, story: the share of blacks living below the poverty line in 2015 was 24.1 percent, more than double the share of whites (11.6 percent). In consequence, white people who harbor racial resentments can, with some statistical validity, view antipoverty programs as “for those people.” In our society, sadly, attitudes like that undermine political support for antipoverty measures.

So the short answer to the question “Why doesn’t the government do more?” is: politics. Economics provides a modestly long list of policies that could ameliorate, though certainly not eliminate, inequality. But the American political system won’t adopt them. Attitudes toward redistribution are laden with value judgments, and, to put it bluntly, we Americans are not very egalitarian compared to, say, Western Europeans.

A Role for Illumination?

Could we do better? Economics certainly doesn’t offer all the answers—not even close. Even if economists ran the world—a fanciful, or perhaps horrifying, thought—we would not know how to abolish poverty or inequality. Maybe we could only make a dent. But American politics has set the bar really low, making it child’s play to improve on the status quo. That’s the basis for my claim that our nation’s policies toward income inequality could be more effective if politicians would accept more economic illumination instead of just insisting on political support for preconceived notions.

The Lamppost Theory of redistribution plays out quite differently for Democrats and Republicans. For Democrats, most of whom are disposed to tackle the inequality problem, the main need is to concentrate more on evidence-based policy rather than what’s been called policy-based evidence. In many cases, redistributive policies will shrink the pie. Let’s not deny that. Supply-side economics may be a comic exaggeration, but incentives do matter. So let’s seek out redistributive policies that shrink the pie just a little, or maybe even expand it. And let’s not get swept up by romantic ideas like a $15 national minimum wage. (A local minimum wage of $15 per hour in San Francisco is another matter entirely.) Nor that cutting the United States off from international trade will help reduce poverty. (It won’t.)

For Republicans, let’s recognize that those “lucky duckies” who are too poor to pay income taxes are not reveling in their good fortune, that the unemployed would prefer a hand up rather than a handout, and that sheer luck plays a larger role in economic success than the economically successful care to admit. And let’s recognize, first, that the United States really doesn’t do much for society’s underdogs, and second, that we could do a lot more in ways that could be (but aren’t now) bipartisan. I am thinking, especially, about education broadly conceived, ranging from pre-K for three-year-olds all the way to vocational training and apprenticeships for young adults who don’t go to college. Remember that Horatio Alger was born into the New England aristocracy and attended Harvard—advantages not shared by many.

Here, as elsewhere, it’s not a matter of finding a magic bullet that will return inequality to 1980 levels, nor even a boxful of such bullets. Rather, it’s a matter of moving the needle a bit. We don’t know how to solve the inequality problem, but we could manage it much better than we do. More hard-headed but soft-hearted thinking based on evidence—more illumination, if you will—and less partisan ranting would help.

* If you want the torture, you can find it on Wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gini_coefficient.

* A wonkish but important note: Unlike the other percentile bars, the ninety-ninth percentile is based on annual earnings, not hourly wage rates. The former depends, in addition to wages, on hours of work per year. The annual data can be found at Lawrence Mishel and Teresa Kroeger, “Strong Across-the-Board Wage Growth in 2015 for Both Bottom 90 Percent and Top 1.0 Percent,” Economic Policy Institute Working Economics Blog, October 27, 2016, epi.org/blog/strong-across-the-board-wage-growth-in-2015-for-both-bottom-90-percent-and-top-1-0-percent.

* More educated workers also experience fewer, shorter spells of unemployment. So not only do they earn more per hour, over the years they work more hours.

* It is true that the 1996 welfare reform passed under a Democratic president, Bill Clinton. But Republicans then held majorities in both houses of Congress.

* The famous quotation “That government is best which governs least” is often attributed to Thomas Jefferson, but historians have never unearthed evidence that he said it.

* Late in President Obama’s second term, the Department of Labor issued a rule that would have roughly doubled the overtime ceiling. President Trump cancelled it. US Department of Labor, “Overtime for White Collar Workers: Overview and Summary of Final Rule,” May 18, 2016, dol.gov/sites/default/files/overtime-overview.pdf.