Great chefs don’t ask “Why?” They ask “Why not?” They aren’t afraid of a challenge and they aren’t afraid to break the rules. But they also have the technical training necessary to play with recipes while intuitively knowing which crucial steps should not be sacrificed.

—DANIEL BOULUD, The Dinex Group (New York City)

If you’re reading this book, you no doubt have a passion for food and drink, and likely have more than a passing interest in learning to prepare them more creatively.

But if you question whether you have any natural talent for it, take heart. Alain Ducasse, the first chef in the world to hold nine Michelin stars at his restaurants, estimates that talent is responsible for a mere 5 percent of great cooking.

Another 35 percent is technique, and fully 60 percent is the quality of the raw materials.

You can learn technique: in books (in addition to this one, see The Chef’s Library here), in the classroom, in a restaurant kitchen. And you should.

But the most important thing you can do to master cooking is to develop your palate and your ability to both 1) determine the excellence of your ingredients, and 2) make them taste delicious, even when they’re imperfect.

Some believe that the process of mastery of any field demands a “10,000-hour” threshold of deliberate practice. In cooking, however, mastery involves gaining knowledge through not only the hands, but also the head and especially the palate—which involves a combination of practice (cooking), reading, and tasting (both while cooking and while shopping and dining). The Mastery section provides a broad-brush overview of some of the knowledge and skills to be mastered during this stage.

The whole movement that Ferran Adrià started in cuisine was possible because he knew classical cooking better than anyone.… How far you can take creativity is a function of the products you understand and techniques you’ve mastered.

—GABRIEL KREUTHER,

Gabriel Kreuther (New York City)

Learn foundational techniques and recipes.

Classical Western cuisine once required a foundation in French technique, just as classical Eastern cuisine did a foundation in Chinese technique. Both still provide a valuable foundation. However, you can also benefit from studying the classic ingredients, techniques, and dishes of many different cuisines. It’s up to you what you feel most drawn to—whether learning to toast and temper and blend spices through studying Indian cuisine, or learning to toast hand-crafted marshmallows for perfect s’mores in the spirit of American campfire “cuisine.”

If you learn the masters’ recipes for building blocks, you can later build your own dishes from them. Mark Levy of Magdalena at the Ivy Hotel in Baltimore doesn’t hesitate to acknowledge that he uses Alain Ducasse’s gnocchi recipe. (Levy channels his creativity into his accompanying mushroom brodo, which he makes by deeply caramelizing mushrooms and deglazing them with a red wine syrup and adding a tiny hint of bird’s eye chiles, which enhance the other flavors.) Nor does Levy hesitate to share that he uses the recipe for Dominique Ansel’s Chocolate Pecan Cookies for the ones he serves with his own version of crème brûlée. “They’re baked to order, and gluten-free,” says Levy.

Be literate.

Read the gastronomic literature. It will be hard to talk your way convincingly into top chefs’ kitchens if you’ve never even cracked the spine on their cookbooks. At the very least, make your way through some or all of the basic foundational texts.

Top Books Recommended by Chefs

Employ your time in improving yourself by others’ writings, so that you shall gain easily what others have labored hard for.

—SOCRATES

No one who cooks, cooks alone. Even at her most solitary, a cook in the kitchen is surrounded by generations of cooks past, the advice and menus of cooks present, the wisdom of cookbook writers.

—LAURIE COLWIN

Cookbooks were my mentors.

—BARBARA LYNCH,

Menton (Boston)

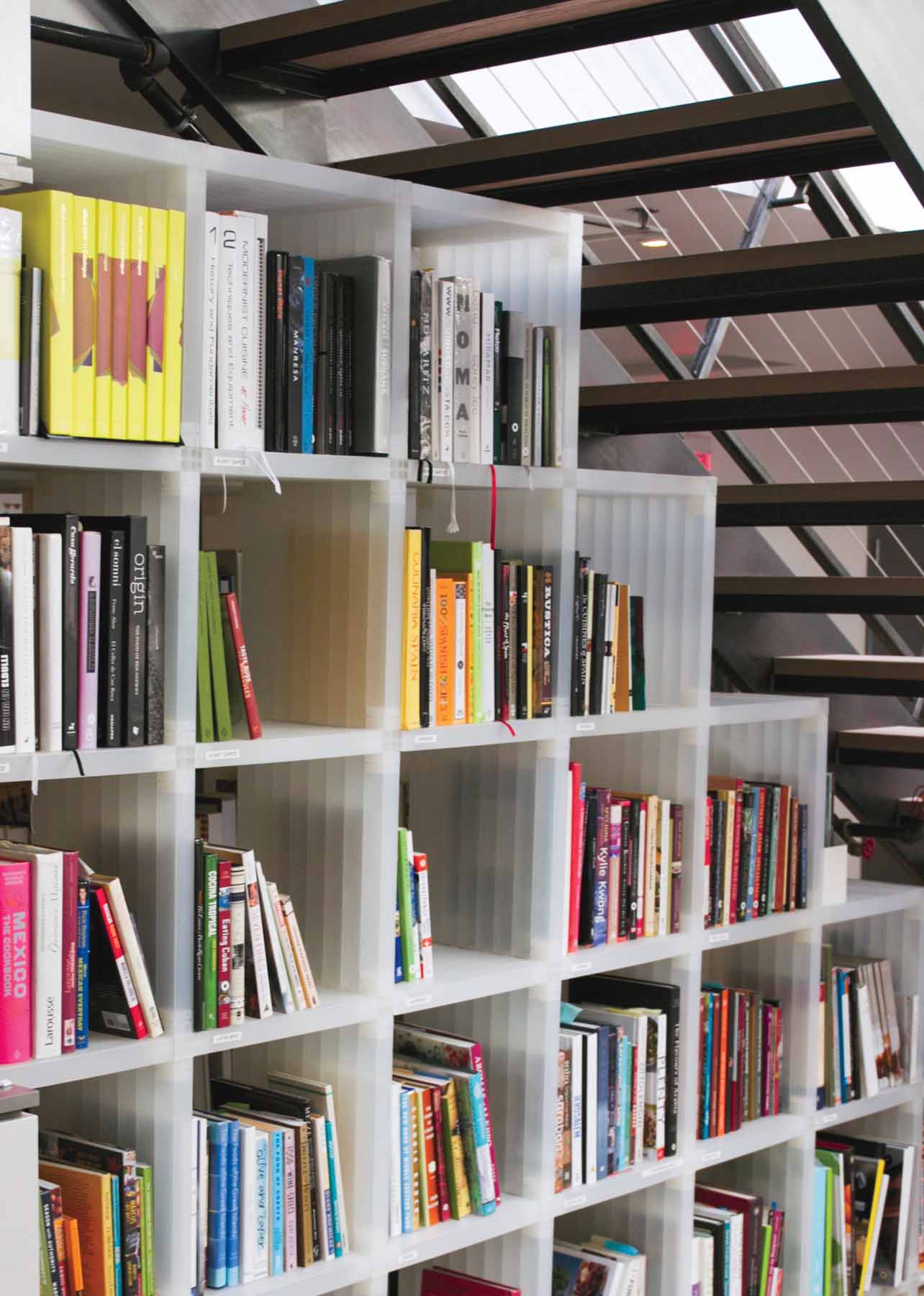

Top chefs and restaurants have long believed that food lovers shouldn’t waste a moment not reading great books about food. Eric Ripert owns more than 1,000 cookbooks, including a 1907 first-edition of Gastronomie Pratique, which is also a beloved favorite cookbook of chefs Michel Richard and Jean-Georges Vongerichten. (Vongerichten has described Henri Babinski’s imaginative yet technically precise book, written under the pseudonym of Ali-Bab, as “ahead of its time,” and more interesting than Escoffier.) Ripert keeps many of them in a conference room under Le Bernardin in New York City. His sous chefs are required to review every single one.

Having interviewed leading professional chefs extensively about their most-loved and most-used food books, I’m very familiar with their top picks. They’re listed chronologically. “Everybody knows that” the new generation sometimes scoffs about the contents of a decades-old book. Well, everybody didn’t know that back then—and these are the books that created culinary “common sense.”

A large cookbook collection allows you to research trusted sources regarding different ways to prepare a particular ingredient, apply a particular technique, or make a particular dish. When the approach you choose is informed by the wisdom of multiple experts that came before you, how can your version help but be better?

Read an inspiring book, then close it and really think about it—so its lessons become more intuitive.

—MICHAEL ANTHONY,

Gramercy Tavern and Untitled (New York City)

ThinkFoodGroup

Leading Chefs’ Top 20 Culinary Books

1. Le Guide Culinaire by Auguste Escoffier (1903) | codification of classical French cuisine that has won the admiration of chefs like Scott Conant, Jason Neroni, Rich Torrisi, and Ming Tsai

2. Encyclopedia of Practical Gastronomy by Ali-Bab (1907; first English edition in 1974) |

classic treatise on gastronomy that is beloved by chefs like Daniel Boulud, David Kinch, Michel Richard, Eric Ripert, and Jean-Georges Vongerichten

3. Joy of Cooking by Irma S. Rombauer (1931) | codification of American cuisine; a favorite of chefs like Traci Des Jardins, Bobby Flay, Anita Lo, Emily Luchetti, and Christina Tosi

4. Larousse Gastronomique by Prosper Montagne (1938) | the A-to-Z French culinary encyclopedia that Daniel Boulud described as “the only [one] that is always up to date” and also counts as fans Dan Barber, Marcus Samuelsson, Mario Batali, Thomas Keller, Vitaly Paley, and Charlie Palmer

5. Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Julia Child, Louisette Bertholle, and Simone Beck (1961) | the classic that brought French cuisine to American kitchens; a favorite of Lidia Bastianich, Ris Lacoste, Emily Luchetti, Patrick O’Connell, Barton Seaver, and Nancy Silverton

6. Ma Gastronomie by Fernand Point (1969) | philosophy from the influential

French restaurateur behind the long-time Michelin three-star La Pyramide, and a favorite of chefs like John Besh, Thomas Keller, Ludo Lefebvre, and Jasper White

7. Couscous and Other Good Food from Morocco (1973), The Cooking of Southwest France (1983), World of Food (1988), and other books by Paula Wolfert | a personal way with words, whether writing about rustic (and lighter) French cuisine or couscous, that has “mentored” chefs like Hugh Acheson, Jody Adams, David Lebovitz, Tony Maws, Nancy Silverton, and Susan Spicer

8. La Technique (1976) and La Methode (1979) by Jacques Pépin | illustrated guides to cooking fundamentals that are favorites of chefs like Andrew Carmellini, Roy Choi, Tom Colicchio, and Michel Nischan

9. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen by Harold McGee (1984) Mark Levy | how-to on enhancing food through science from the Yale-educated PhD; taught readers like Dan Barber, Matt Dillon, Michael Laiskonis, Ivy Stark, and Paul Virant

10. Chez Panisse cookbooks (Chez Panisse Desserts, 1985; Chez Panisse Cooking, 1994; Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook, 1995; et al) by Alice Waters, Paul Bertolli and/or Lindsey Shere | local/regional/farm-to-table cookbooks that count chefs like Matt Dillon, Wylie Dufresne, Suzanne Goin, David Lebovitz, and Nancy Silverton as fans

Mark Levy

11. White Heat by Marco Pierre White (1990) | the bad-boy-chef-as-rock-star’s first cookbook, with black and white photos of kitchen life juxtaposed with four-color photos of his vibrant food, that inspired chefs like Chris Cosentino, Paul Liebrandt, Michael Mina, and Rich Torrisi

12. Culinary Artistry by Andrew Dornenburg and Karen Page (1996) | insider guide to culinary composition and flavor pairings that is a favorite of Grant Achatz, Hugh Acheson, Timon Balloo, John Fraser, Will Goldfarb, Michael Laiskonis, Michael Mina, Jesse Schenker, Ivy Stark, and Ethan Stowell

13. The French Laundry Cookbook by Thomas Keller, Michael Ruhlman, and Susie Heller (1999) | California-style haute cuisine cookbook that influenced Justin Aprahamian, David Chang, and Marc Forgione, as well as notable alums like Grant Achatz

14. Le Grand Livre de Cuisine d’Alain Ducasse by Alain Ducasse (2001) | culinary encyclopedia created by one of France’s greatest contemporary chefs

and admired by chefs like Carrie Nahabedian, Alison Vines-Rushing, and

Michael White

15. River Cottage cookbooks (The River Cottage Cookbook, 2001, The River Cottage Fish Book, 2007, The River Cottage Meat Book, 2004, and River Cottage Veg, 2011) by Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall | authentic, locavore, sustainable cookbooks that have inspired chefs like Justin Aprahamian, Dan Barber, April Bloomfield, and Brad Farmerie

16. Essential Cuisine by Michel Bras (2002) | a visual-feast-inspiring presentation that is a favorite of David Chang, Dominique Crenn, Curtis Duffy, Daniel Humm, Gavin Kaysen, and David Kinch

17. Zuni Cafe Cookbook by Judy Rodgers (2002) | cooking philosophy from the late San Francisco chef, which Mike Anthony considers a foundational text that has inspired some of his own kitchen creations, and also counts as fans Anne Burrell, Suzanne Goin, Alex Guarnaschelli, Nigella Lawson, David Lebovitz, Bryant Ng, and Barton Seaver

18. Cooking by Hand by Paul Bertolli (2003) | cooking philosophy book by the former Chez Panisse chef that is a favorite of chefs like Justin Aprahamian, Jeremy Fox (who counts it as one of his two most-used books), Ben Ford, and Blaine Wetzel

19. The Flavor Bible by Karen Page and Andrew Dornenburg (2008) | A-to-Z guide to flavor pairings and affinities that counts as fans Nina Compton, Jared Gadbaw, Gunnar Gislason, Carla Hall, Josh Habiger, Timothy Hollingsworth, Hung Huynh, Matthew Kenney, and Michel Roux

20. elBulli books by Ferran Adrià (1994–2011) | books that expanded the boundaries of food through science and art, earned fans like Grant Achatz, José Andrés, David Chang, Eric Ripert, Damian Sansonetti, and Michael Voltaggio

Daniel Boulud, whose personal favorite books include Le Repertorie de la Cuisine by Louis Saulnier (1914)

Pick chefs and food worth copying—study the greats,

and emulate their standards.

The ultimate way to learn from a master is to spend time in his or her kitchen. Not so many years ago, ambitious cooks looking to work in a restaurant kitchen might simply drop off their résumé at every four-star or three-star restaurant in town, as guided by the local newspaper’s reviews. Today, the most ambitious cooks might be guided to work at restaurants that have been recognized on the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list, or with chefs who have distinguished themselves via recognition through the James Beard Foundation Awards. (See the Appendix for listings of named restaurants, here, and JBF-recognized chefs, pastry chefs, and rising stars, here.)

Today, those restaurants are so diverse that you’ll want to do your homework in advance. As a first pass, you can research restaurants online, reading about their cuisines and chefs, and seeing which dishes appeal to you and whose philosophies you’re most drawn toward. As a next step, you could visit for a meal, or sit in the bar and order a drink and an appetizer or two to get a sense of the restaurant’s vibe. Or you could attend a lecture or cooking class or volunteer at a charity event where you’re able to taste the chef’s food and interact with the chef.

Somebody once said to me that you have to be as excited about mashed potatoes or a PB&J sandwich as you are about a dish with truffles. And I think it’s true. If you look at it and think, “Eh, it’s just mashed potatoes…,” then it is just going to be mashed potatoes. But if you look at it and think, “I’m going to make the best mashed potatoes I possibly can,” and you get it down to the type of potato you’re going to use, and down to the gram how you’re going to season them perfectly, then it changes your approach. And you can approach everything that way.

—MICHAEL VOLTAGGIO,

ink (Los Angeles)

Having a compelling reason to want to study with someone, and a sense that there’s already a fit between the restaurant’s style and your own interests, can help you land a stint in a coveted professional kitchen.

Cooking at Melisse with [chef-owner] Josiah Citrin is where I learned so many fundamentals—like making sauces, and making smooth pureed soups, and roasting mushrooms. Working the meat station at Melisse, we’d have eight different jus on hand—including chicken jus seasoned with dried orange zest, duck jus finished with caramelized sugar and star anise, and beef jus finished with herb butter. Josiah and [chef de cuisine] Ken Takayama were constantly creating new dishes, inspired by their visits to the market.

—Katianna Hong, The Charter Oak (Napa Valley)

Jon Shook and Vinny Dotolo on Changing Influences

Cooking was different when we started cooking together in the late 1990s: Chefs were all about “the best” ingredients [and flying them in from wherever they were sourced, whether Thailand, North Dakota, or South Africa]. That was the mentality. When we moved to California in the early 2000s, we really adapted a lot of its philosophies, stemming from Alice Waters, obviously, and it became about “hyper-local.” We didn’t want to fall into that mix of just California-based cuisine, but we wanted to respect it.

We worked in Miami for Michelle Bernstein, which is where we first started cooking together. You still had to use your imagination then. Like, a cook would go to New York and bring back copies of the menus of the restaurants they ate at, and you had to use your imagination to figure out what these dishes were actually like. Now, there’s Instagram, so you feel like you’ve already been to all these restaurants in your mindspace.

A year or two ago, we wanted to hire some culinary students, so we had a questionnaire, and one of the questions we asked was “What’s your favorite cookbook?” And 90 percent of the people cited a website (e.g., Epicurious.com). Shocking. The irony was that we were doing the interviews in a library. We went to school at the beginning of the end. Now, some [culinary students] don’t even know guys that were key to American cooking. If you walked down the line and asked, “Who was Charlie Trotter? Who was Jean-Louis Palladin?,” they’d be scared. Everybody knows René Redzepi, but that’s it.

Vinny Dotolo and Jon Shook

Remember that there’s also much to be learned from those who have studied under great chefs and soaked up their lessons, but whose own still-rising star status may make their kitchens more accessible to mere mortals. You’ll read about a few of them in this book, and the lessons they’ve been able to absorb during their time in top kitchens across the country.

LEARNING TO TASTE

Just as there is more to a song than its sheet music, there is more to a dish than its recipe. Chefs’ know-how with regard to seasoning and flavoring gives them the power to make crucial creative decisions in the moment regarding a dish-in-progress.

You can follow a recipe perfectly, yet still end up with a dull, listless dish. Why? Recipes can’t account for every possible variable—in ingredients (the age of your spices, the strength of your herbs, the ripeness of your fruit; not to mention that the same six-ounce fillet can be thick or thin), in equipment (an oven running hot or cold), in weather (that day’s humidity), and so on. Luckily, you can develop the ability to taste and to adjust a dish’s flavor as you go—which is the fundamental skill for anyone looking to master cooking.

Flavor is more important than technique.

—GAVIN KAYSEN, Spoon and Stable (Minneapolis)

In music, there’s such a thing as perfect pitch—or you can simply use a pitch pipe to tune your own instrument to the same musical scale as every other musician. However, in food, we haven’t yet invented a “flavor pipe” to be able to tune our own dishes to perfection. That’s why “Taste, taste, taste” has become the mantra great chefs teach their cooks—and why learning to imitate an expert’s palate via cooking classes or stints in professional restaurant kitchens can be invaluable. You’ll learn how to make each carefully chosen ingredient through perfect cooking and seasoning reach its peak of perfection—something the French refer to as à point. While in time you can and should develop your own individual palate, you’ll want to learn to season with a master whose palate and seasoning techniques you can imitate. And you’ll learn that the quality of the dish you’re creating will never be better than the quality of the ingredients you put into it—so you’ll learn to shop where the best chefs shop, and to patronize the same producers the best chefs do (see Set Your Standards: Choosing the Highest Quality Ingredients, here).

When I first opened Public [in 2003], food was more about whiz-bang technology—circulators, sous-vide, bendable solids, liquid nitrogen. But now that’s gone into the background. Today, it is much more about ingredients and flavor.

—BRAD FARMERIE,

Saxon + Parole (New York City)

Having a trained palate allows you to take any ingredient and know how to enhance its flavor—or when to leave it alone. It also serves as the foundation of creating a dish from start to finish—or of rescuing one that’s falling flat.

Cooking begins with getting to know your ingredients every single time you use them—that is, tasting them at the very beginning, and during the entire cooking process, all through to the very end.

You have to have an attention to detail and a knowledge of what is good and what is possible. You have to know how to work with textures, or what salt or lemon will do to your food. You have

to understand balance.

—JEREMY FOX, Rustic Canyon (Los Angeles),

on the necessary foundation for creativity

STRIKING A BALANCE

Everything changes; everything stays the same.

—BUDDHA

Balance is one of the central tenets of great food, and one of the most frequently cited characteristics of great cooking among the best chefs we’ve interviewed over the years.

Understanding when a dish is in balance is one of the most essential aspects of mastering flavor. A feeling of completeness is achieved by the embrace of opposites within a dish—whether hot and cold (e.g., hot chocolate with whipped cream), crunchy and soft (e.g., nachos with melted cheese), or spicy and sweet (e.g., Thai sweet potato curry).

Balance is fundamental to creative individuals as well. Dr. Scott Barry Kaufman, scientific director of the Imagination Institute at the University of Pennsylvania, sees two opposing super-factors in the personalities of creative individuals: divergence and convergence. Divergence is non-conformity and out-of-the-box thinking related to impulsivity. Convergence is the ability to be practical, and to bring ideas into reality. Given the definition of creativity as the ability to make new things that are both novel and useful, it’s clear how creative types need both.

According to psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, creative individuals also have a predisposition to psychological androgyny: “Creative and talented girls are more dominant and tough than other girls, and creative boys are more sensitive and less aggressive than their male peers.”

So the most creative people tend to be “both/and” people: paradoxically, both masculine and feminine, extroverted and introverted, imaginative and realistic, playful and disciplined, humble and proud.

The chef’s profession is a messy set of contradictions that fits right in: Chefs at the highest levels of the profession have taken their rightful place among so-called right-brain conceptually driven (culinary) artists, even as they must think like left-brain analytically driven managers or entrepreneurs who must keep an eye on costs in order to be profitable and to keep their doors open.

It’s crucial to taste as you go. Analyze what’s going on in your dish, and what the objective is. Start by identifying the dominant taste: sweet? salty? sour? bitter? savory? Is it appropriately balanced? If not, you’ll be able to work with the other tastes to find a better balance.

Think about the context of what it is you’re tasting. What is its intended final format? A hot soup that will be garnished with other ingredients? A room-temperature dipping sauce for something more neutral-flavored? Imagine it in that context, and at that temperature, and adjust appropriately. Take what you know or can intuit about your guests’ palates into account.

And if wine is part of the equation at the meal, try to taste the sauce alongside the wine the dish will be served with.

Cooking at Charlie Trotter’s, I learned to taste things over and over again. Even though you tasted it at 2 pm when you made it, this afternoon it changed—and at 7 pm it’s different, and at 9 pm it’s different from what it was at 7 pm. Oxygen affects it, reduction affects it, time affects it—all these things affect it. So you’ve got to taste it, and fix it, and make it right again.right again.

—CURTIS DUFFY, Grace (Chicago)

LEARNING TO SEASON

One of the most important things you’ll learn as you imitate the masters is how to season a dish to deliciousness. Embedded in classic recipes is information about recommended proportions of various ingredients. While you’ll develop your own palate so that you can “season to taste,” you’ll have to learn to taste first—and there’s no better place to start than by having a benchmark in your taste memory of some of the best versions of particular dishes. Eating at the best restaurants—as a guest, while cooking in their kitchens—is an invaluable part of this process.

In the kitchen at Coi, it struck me how much we tasted the food. You tasted what every other person there was working on. You only had two dishes, and every day you brought them to the chef to taste for consistency. You would taste it five or six times and talk about it every day for 20 minutes. Daniel [Patterson, the chef] would tell you, “You need two drops of this or two grams of that”…But you learn to trust certain people’s palates. Every night [at Natalie’s], we will hand each other a spoon and ask, “What do you think?” At Coi, there was an acceptable range of salt or acid, and we could just look at each other and know.

—SHELBY STEVENS, Natalie’s at the Camden Harbour Inn (Maine)

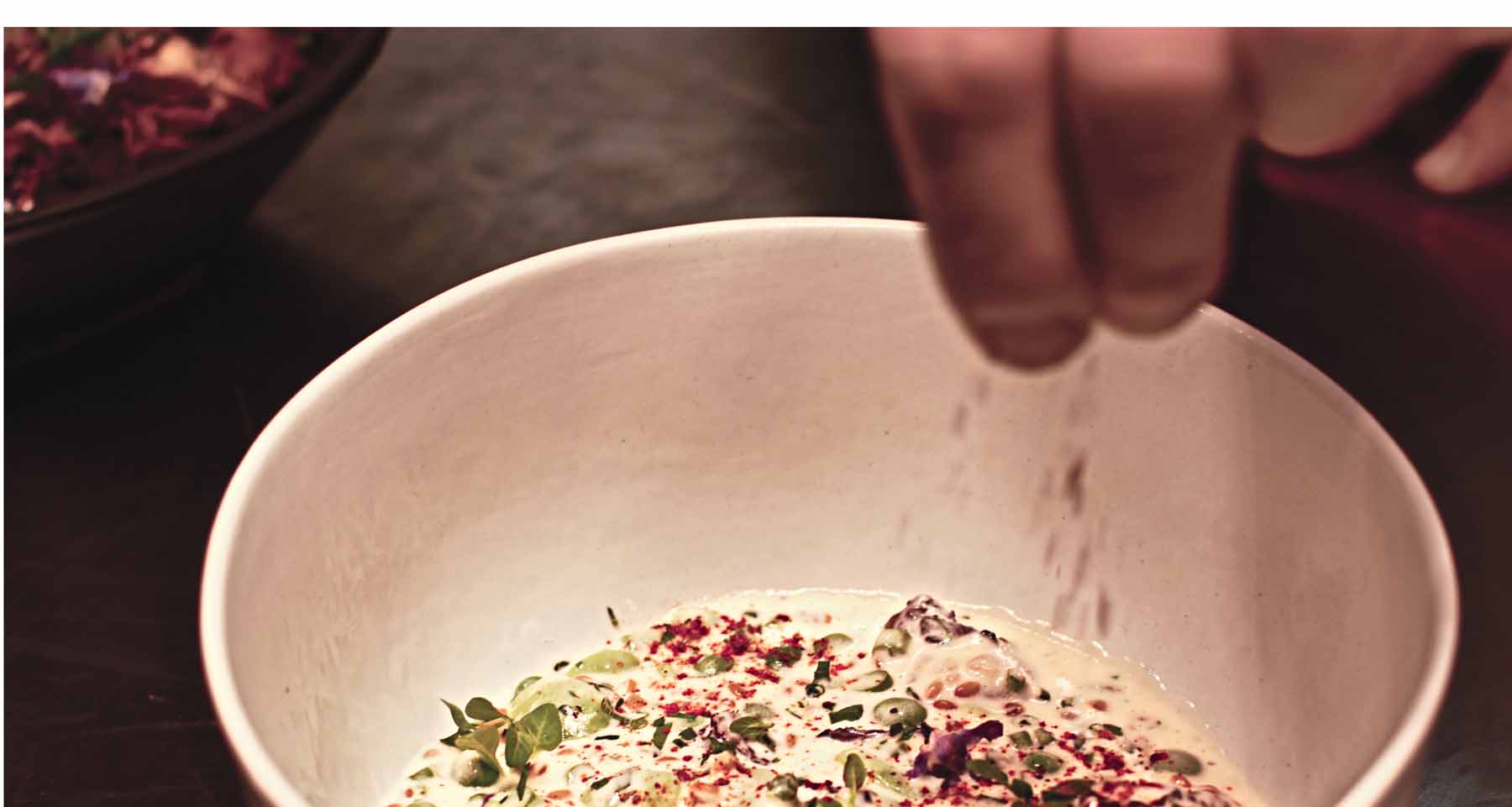

Seasoning makes an ingredient taste like more of itself. An asparagus spear will still taste first and foremost of asparagus, for example, once it’s been sprinkled with just the right amount of salt. Strawberries will taste more like strawberries, once they’ve been hit with just the right amount of sugar.

Salt is the single most important flavor enhancer for savory foods, and sugar the single most important for sweet foods such as fruit. Acidic ingredients—such as citrus juice, or vinegar—are the second-most-important flavor enhancers. And while a pinch of sugar in a savory dish can serve the role of balancing flavors as a flavor enhancer, once that sweetness is noticeable, it’s wrong. The dish should taste better, but not salty or sweet.

Seasoning Savory Dishes

Saltiness is the first place to start in any savory dish, as it’s the most important taste. You’ll want to taste your ingredient(s) first, and determine whether a bit of salt might add value as a flavor enhancer. The key is to learn to add just enough to enhance the flavor of the ingredient without being detectable—and no more. Salt slowly and gradually.

Seasoning and spicing is the first thing a young cook needs to learn, and it’s the hardest thing to teach. There’s no miracle recipe to follow.

—DANIEL BOULUD,

The Dinex Group (New York City)

The most important thing for a chef to know? Seasoning.… How to use salt.… Salt really is what enhances flavor.

—THOMAS KELLER,

The French Laundry (Yountville, California) and Per Se (New York City)

Once you’ve reached an optimal level of saltiness, check to see whether adding a hint of acidity—e.g., a squeeze of lemon or lime, or a dash of vinegar—would enhance the dish’s flavor further. A bit of brightness can make a dish that’s flat or heavy start to sparkle. You’re looking to bring out the dish’s flavors—not to mask them with acidity.

This is the point at which experienced chefs can learn to finesse even further. Perhaps you’re making a tomato sauce that’s now beautifully balanced in saltiness and acidity, but would still benefit from a rounder flavor. You might consider adding a bit of sweetness through a pinch of sugar. Or perhaps you want to heighten those flavors even further—in which case you might add piquancy through a pinch of cayenne instead.

Flavor enhancement can also take place through adding an ingredient rich in umami to a dish. However, this is a bit more complex, given that many ingredients that add umami also simultaneously add another taste, such as salt (as in miso paste or Parmesan cheese); this will be addressed further during Stage 2.

It’s easier to add more than to remove seasoning. Don’t believe you must season the whole pot of soup at once—remove a cup for your seasoning experiment, and once you achieve your desired flavor, season the entire pot that way. From time to time as you taste and adjust a dish, be aware that you will want to cleanse your palate (e.g., with a sip of water, or a bite of bread or cracker—Eric Ripert tastes bites of cheese between spoonfuls during his daily sauce tasting).

Don’t hesitate to seek another opinion to counterbalance your own. Married chefs de cuisine Katianna Hong of the Charter Oak and John Hong of The Restaurant at Meadowood go to each other first to taste each other’s dishes. (Katianna says she’ll ask, “Am I crazy, [or does this need something]?”) Of the couple and their executive chef Christopher Kostow, Katianna characterizes Kostow as having the strongest preference for acidity in food, herself as having the strongest preference for pungency and stronger flavors, and her husband as having the strongest preference for restraint and subtlety. “We balance each other well,” says Katianna. “John will keep me from adding too much, and I’ll keep him from being boring.”

It’s mandatory that cooks bring every [element on their stations] for me to taste, every day. It’s not so I can judge it, but because it makes them taste it. I hardly ever corrected anyone near the end [of her term as chef de cuisine at Manresa]. If something needed correcting, I’d ask, “Did you try this?” Then they’d go back and taste it and fix it, and if they brought it back and it still wasn’t correct, we’d work together to fix it.

—JESSICA LARGEY,

Simone (Los Angeles)

Seasoning is like tuning: You taste and adjust your ingredients to get them perfect. If you oversalt something, you can’t redo it. With too much acidity, you can add sweetness to bring down the acid.

—EDDY LEROUX, chef de cuisine,

Daniel (New York City)

Meg Galus, pastry chef of Chicago’s Boka, notes that it’s important to get feedback, because when you taste dishes too many times you lose any kind of objectivity. “Lee [Wolen, Boka’s chef] is a more collaborative chef, so we’ll taste together,” she says. “I like a hint of salt in desserts, while Lee likes acid in desserts. Citrus is my go-to, and I’ll also use fruit vinegars and ‘drinking vinegars,’ either to macerate berries or straight on the plate. I try to make every component in a dessert as light as it can be.”

Seasoning Sweet Dishes

Sweetness is the first place to start in any sweet dish. If your strawberries are perfectly ripe and sweet, there’s no need to add sugar. In fact, following a recipe blindly and adding sugar to strawberries when it’s not needed can destroy a dish.

After a dish’s sweetness is optimized, see whether some acidity might enhance the flavor further—just as with a savory dish.

This is the point at which experienced chefs can finesse even further. Perhaps you’re making a lemon sauce for a dessert that’s beautifully balanced between its sweetness and acidity, but would still benefit from a rounder flavor. That’s the time you might consider adding a bit of salt through a pinch of salt or another salty ingredient.

Sugar enhances flavor—up to a point. Too much sugar dulls flavor.

—EMILY LUCHETTI, chief pastry officer of The Cavalier, Marlowe, and Park Tavern (San Francisco)

Jean-François Bruel on Seasoning to Taste

You can’t season if you don’t know how to taste.

You learn the most when you’re a young cook and, early on, it’s hard to learn to control salt. Once you add too much, it’s too late!

[Bruel shares the expert tip of using two, three, or four fingers to grab a pinch of salt, in order to deliver a consistently small, medium, or large pinch of salt, respectively, as needed.]

We only use two kinds of salt, which we never, ever change. We use classic French sea salt [sel de mer] from La Baleine for cooking, and fleur de sel for finishing a dish when we want a bit of crunch.

You have to think about the dish, and understand what it is you’re seasoning. You’ll want to season a tiny accent of coulis very differently from an entire bowl of soup. A few drops of coulis should be tart and spicy so it makes an impact—but if you’re eating an entire bowl of soup, it should be flavorful with enough acidity and salt without being overpowering (and wearing out the palate).

You taste, and taste, and taste—and add what’s missing, adjusting the flavor. You’ll want to make sure the spice and seasoning and acidity are all in balance. Acidity adds a nice pop to a dish, and can cut the fat. Bitterness often needs a bit of sweetness to balance it out.

You want to think about where the kick is in your dishes—in the spice? in the acid? in the sauce? Or in a pureed vegetable on the side?

Even traditional French dishes like a velouté sauce will have a dash of Tabasco or cayenne pepper to push the other flavors forward. Michel Guérard would say, “It’s the ingredients you can’t see that boost the other ingredients.” Things like cayenne, espelette, mustard, and vinegars all serve this function. Even in France, chefs will add a dash of soy sauce to enrich a consommé. Orange zest will be added to braised veal—and while you won’t see it in the dish, its flavor makes a big difference.

ENHANCING FLAVOR VS. ADDING FLAVOR

The minute the taste of salt or sugar or acid or anything else is apparent on the palate, that’s not enhancing flavor, that’s adding flavor. Key sources of added flavors are herbs, spices, and other flavorings (such as garlic).

Certain ingredients play different roles at different times. Capsicum-dominant ingredients (e.g., chile peppers) are so strongly flavored that their heat is typically thought of as an added flavor. But cayenne pepper can be used in miniscule amounts such that it’s not noticeable by itself, yet it quietly boosts the flavor of the other ingredients. In those cases, it is a flavor enhancer.

A spice is anything and everything I can use to flavor food. In my spice blends, I use everything I can dry, embracing the notion “Reuse before Recycle.” And that goes for herbs, peppers, and citrus. I’ll grate a whole dried lemon. If I have leftover herbs, I’ll dry them—dried herbs serve a different function than fresh. Fresh, a tomato is a vegetable—but dried, it is a seasoning. Tomato powder, cheese powder, bonito flakes—I think of them all as spices.

—LIOR LEV SERCARZ, La Boîte (New York City)

Lior Lev Sercarz

When Andrew cooked in the kitchen of Lydia Shire in Boston, her motto was, “Don’t spare the fat, dear.” “Fat equals flavor” was pounded into many cooks’ heads. And when fat—such as butter and cream—were added in judicious amounts, their richness could indeed enhance mouthfeel and thus flavor. When cooks went overboard and the presence of butter and cream became dominant, the balance—and the flavor of what should have been the “star” ingredient—was lost. When you’re making cream of tomato soup, you want to be able to taste the tomato and its acidity and other properties.

When you actually want to add flavor to a dish, there’s another huge world of possibilities available to you. Understanding what herbs, spices (and spice blends), and other flavorings (from garlic to zest) best enhance a particular ingredient can give you a huge advantage in the kitchen.

Jessica Largey of Simone on Seasoning and Adding Flavor

You want to have your salt, acid, and sugar ready in order to balance flavors. At Manresa [where Largey served as chef de cuisine under chef-owner David Kinch], I think both David and I saw acid as equal in importance to salt when seasoning food. LEMON JUICE IS MY GO-TO ACID—one of my friends says my middle name is “Lemon Juice” because whenever I’m asked to taste a dish, I almost invariably say it needs lemon juice. I love citrus in general, but I especially love lemon juice for the acidity and brightness it gives. When I dress salads, I’ll be asked what kind of salad dressing I used, and I’ll say, “None—just lemon juice and olive oil.” Not everyone loves all the other citrus fruits, but virtually everyone loves lemon.

I have an entire selection of vinegars. Champagne vinegar is the lemon juice of the vinegar world. It has higher acidity [typically 7 percent] versus other vinegars, like cider vinegar [typically 5 percent]. White balsamic vinegar is one of the most neutral types, so it marries well with flavors like fennel or herbs. I love making my own infused vinegars, especially at Manresa with produce from the farm.…

When something is too salty, you can sometimes fix it with acid or with sugar. You don’t want to add enough sugar to make it sweet—you just want to add it until the dish’s flavor hits equilibrium without its sweetness being noticeable. If it’s a hot dish and the sugar will melt easily, you can use granulated sugar—otherwise, if it’s a cold dish [or iced tea], you can add simple syrup. But the syrup contains water, so it’s diluted—and you don’t want to risk diluting flavor.

When I was in China, I visited a Szechuan cooking school that was training cooks not to use MSG, and to use sugar instead. Apparently MSG breaks down into sweetness, so sugar can serve the same function.

If I were making an onion sauce and wanted more sweetness, I might substitute shallots—which are naturally sweeter—in order to increase the sauce’s sugar content.

Jessica Largey

SET YOUR STANDARDS: CHOOSING THE HIGHEST QUALITY INGREDIENTS

Do you know the resource sections that typically appear at the end of leading chefs’ cookbooks, listing their suppliers of the specialty ingredients mentioned in their recipes? These compilations are too often overlooked, but they’re pure gold: a database of where the best chefs source the best ingredients. Use them to stock your own pantry, realizing that no dish can ever be any better than the ingredients you put into it.

While many produce suppliers are local farmers and greenmarkets, others ship cross-country and beyond. The trusted food sources listed below provide high-quality ingredients to some of America’s best restaurants.

AmadeusVanillaBeans.com for vanilla beans

Amoretti.com for flavor sprays, nut flours

AnsonMills.com for beans, Carolina Gold rice, fine-ground polenta, grits, heritage grains

Asiachi.com for bitter almonds (aka apricot seed)

AsianFoodGrocer.com for dried bonito flakes, kombu, yuzu

AUISwiss.com for chocolate, rose petals

BaldorFood.com for finger limes, hearts of palm

BellaVado.com for avocado oil

BlisGourmet.com for barrel-aged products (e.g., fish sauce), maple syrup, sherry vinegar

BobsRedMill.com for flours (e.g., almond, hazelnut, semolina), grains, other ingredients (e.g., dried sour cherries)

BoiledPeanuts.com for green peanuts

BoironFreres.com for cherry puree

BourbonBarrelFoods.com for Bluegrass soy sauce, bourbon-smoked black pepper, bourbon-smoked paprika, aged vanilla extract

BulkFoods.com for apple pectin powder

BuonItalia.com for Italian foods (e.g., dried pastas, olive oils, truffle oil, truffle paste, white truffles)

ChefRubber.com for cocoa butters, Pop Rocks (aka pastry rocks)

ChefShop.com for French olive oils

Chefs-Garden.com for baby herbs, baby turnips, edible flowers, micro-greens

ChefsWarehouse.com for Banyuls vinegar, brik dough, flavored olive oils, Korean dried chili threads, liliput capers, pastry cream powder, pistachio paste, strawberry puree, Valrhona chocolate, white balsamic vinegar

CookingDistrict.com for Huilerie Beaujolais vinegars, Melfor vinegar, Orleans mustard, pistachio oil, walnut oil

Dartagnan.com for dried and fresh mushrooms, Perigord truffles, truffle juice

DeanDeluca.com for honey, pastas, salts, vinegarsDespanaNYC.com for aged sherry vinegar, pimentón, piquillo peppers

Our suppliers also supply inspiration.… For two years, we’ve been working with Daniel Leiber, a CIA graduate who has StarDust Farm in Pennsylvania….And we get Castle Valley Bloody Butcher Red Grits, which comes in a fine flour and a coarser grain. For the best texture, I combine both with mascarpone and butcher-cut black pepper into a creamy polenta-like dish. It’s a very pinky color, and I’ll pair them with nettles and asparagus.

—EDDY LEROUX, chef de cuisine,

Daniel (New York City)

Eataly.com for pastas

FarmersDaughterBrand.com for pickles, preserves

Freddyguys.com for hazelnuts

Guittard.com for bittersweet chocolate, cocoa powder

Gustiamo.com for artisanal, authentic Italian products (e.g., olive oils, Sicilian pistachios)

KALUSTYAN’S in New York City is frequented by countless chefs and culinarians including Padma Lakshmi and Martha Stewart, and even actor Richard Thomas, who turned us on to its medjool dates during one visit.

HaydenFlourMills.com for durum flour, farro flour, polenta, semolina

Huilerie-Beaujolaise.com for Huilerie Beaujolaise nut oils

ImportFood.com for betel leaves, coconut cream, coconut milk, fresh Thai chiles, makrut limes and lime leaves, Pandan leaves, pad thai noodles, tempura flour

Kalustyans.com for spices and other flavorings from more than 75 different countries, including Aleppo pepper, argan oil, bitters, black garlic, chile pastes, dried apricots, dried chiles, five-spice powder, ghost peppers, Hawaiian sea salt, lemon confit, Madras curry powder, orange blossom water, peperoncino, pimenton, pomegranate molasses, spices, Thai tamarind concentrate, umeboshi vinegar, vandouvan curry spice, vinegar powders

Katagiri.com for kombu, shiro dashi, white miso paste

KingArthurFlour.com for flours

KingOfMushrooms.com for dried mushrooms (e.g., candy cap)

KLWines.com for Boker’s baked apple bitters

KodaFarms.com for sweet rice flour

KoppertCress.com for purple shiso

LaBoiteNY.com for Lior Lev Sercarz’s spices and spice blends

LaTourangelle.com for pistachio oil, truffle oil

LEpicerie.com for Banyuls vinegar, bitter almond extract, chestnut honey, cocoa butter, edible gold dust and leaf, egg white powder, frozen fruit purees, La Baleine salts, pink salt, Valrhona chocolate, violet mustard [moutarde violette]

Le-Sanctuaire.com for carnaroli rice, Szechuan peppercorns, spices

LeVillage.com for Edmond Fallot mustards, Le Puy lentils

LocalHarvest.org for honeys (e.g., acacia, lavender)

Manicaretti.com for black olive paste, pastas

McEvoyRanch.com for extra virgin organic olive oil, olio nuovo

Melissas.com for Brussels sprouts on the stalk, cherimoya, dragon fruit, finger limes, mangosteens, morels, passion fruit, Ruby Gold potatoes, starfruit, truffles (black, burgundy, white)

MikuniWildHarvest.com for vinegars

Minus8Vinegar.com for 8 Brix red and white verjus, ice wine vinegar, rice wine vinegar

MELISSA’S in Los Angeles provides hard-to-find produce for James Beard House and Foundation events such as Chefs and Champagne (in the Hamptons) and Taste America (chefs on tour).

Mitsuwa.com for bonito flakes, kombu, ponzu, shiro dashi, soy sauce, wakame seaweed, yuzu, yuzu juice, yuzu kosho

ModernistPantry.com for agar-agar, xantham gum

MurraysCheese.com for cheese, Marcona almonds

Mycological.com for chanterelles, morels, Oregon truffles, porcini

NielsenMassey.com for vanilla extract, vanilla paste

OliverFarm.com for benne oil

Pastaworks.com for pastas

PerfectPuree.com for apricot puree

PollenRanch.com for fennel pollen

RanchoGordo.com for heirloom beans, posole

RareSeeds.com for seeds

RockRidgeMarketHall.com for Espelette and piquillo peppers, pink salt, verjus, walnut oil

If angels sprinkled a spice from their wings, this would be it.

— PEGGY KNICKERBOCKER in Saveur, on the fennel pollen at Chicago’s SPICE HOUSE, the store Julia Child called “a national treasure”

RoveySeed.com for dried corn, pickling lime

Saffron.com for saffron, vanilla beans

SaltTraders.com for Viking sea saltSaltWorks.us for espresso salt, Maldon smoked sea salt, Murray River sea salt

SantaBarbaraPistachios.com for pistachio flour, pistachio oil

Seaweed.net for bladderwrack, dulse seaweed

SeedSavers.org for seeds

SpanishTable.com for Spanish foods (e.g., chickpeas, smoked paprika, white beans)

Starwest-Botanicals.com for fennel extract, orange blossom water

TempleOfThai.com for galangal, fresh Thai chiles

TennesseeTruffle.com for Tennessee truffles

TerraSpiceCompany.com for beet powder, chicory root granules, dried chiles, freeze-dried fruits and vegetables, piment d’espelette, roasted barley powder, seaweed powder, tonka beans, yogurt powder

TheSpiceHouse.com for adobo seasoning, aleppo pepper, black garlic, Ceylon True cinnamon, fennel pollen, grains of paradise, habanero powder, Indonesian cassia cinnamon sticks, maple sugar, molecular gastronomy ingredients, Saigon bark, spices, star anise, toasted sesame seeds, Vadouvan curry powder, vanilla beans, za’atar

Tienda.com for Spanish products (e.g., Calasparra rice, capers, piquillo peppers, saffron)

TrueFoodsMarket.com for almond flour

Truffe-Plantin.com for black truffles, truffle juice, white truffles

Urbani.com for truffle juice, truffles

Valrhona-Chocolate.com for chocolate, cocoa nibs

Verjus.com for red verjus, white verjus

Zingermans.com for olive oils, vinegars

La Boite

TRAINING YOUR PALATE: ONLY THE BEST WILL DO

You can follow chefs’ recipes or advice on compatible pairings (e.g., sherry vinegar + walnut oil), but your version will never taste as good as theirs unless you’re willing to invest in the same high-quality ingredients.

Train your palate to be able to taste the quality differences between various ingredients. Once you’ve done your homework and tasted some of the benchmark versions, if you still prefer a different producer of course you should go with your own favorite. But never settle for less until you’ve tasted some of the best versions out there of various ingredients, which may be versions from a specific region or specific brands.

Below, you’ll find a list of chefs’ recommended ingredients, which you can track down to use as a flavor benchmark against locally available or other versions:

The heart of good food is to start with the most delicious ingredients you can find.

—MICHAEL ANTHONY, Gramercy Tavern and Untitled (New York City)

Adobo paste: Doña Maria

Almonds, Marcona: Murray’s Cheese (New York City)

Anchovies: Agostino Recca, Scalia

Beans, heirloom: Rancho Gordo

Butter: Beurre Echiré (84%+ butterfat), Jonathan White’s Bobolink Dairy butter, Diane St. Clair’s Animal Farm in Vermont (87% butterfat); David Kinch’s housemade butter at Manresa in California (local cream broken in a Mennonite churn); Norman butter, Plugrá (82% butterfat)

Capers: Pantelleria

Cheese, feta: Pastures of Eden

Cheese, Parmesan: Di Palo (New York City)

Cherries, preserved: Fabbri (Amarena/sugar syrup), Luxardo (Maraschino/liqueur)

Chickpeas: Matiz Navarro, Rosara

Chiles, Calabrian: Tutto

Chili flakes: Hatch (New Mexico)

Chocolate: Amedei, Cacao Barry, Callebaut, Chocolates El Rey, Felchlin, Grenada Chocolate Factory, Guittard Chocolate Company, Kellari, Luker, Scharffen Berger, TCHO, Valrhona

Chocolate, white: Cacao Barry, Guittard, Valrhona (Ivoire)

Cocoa powder: deZaan, Valrhona

Fennel seeds: Lucknow (region of India)

Fish sauce: BliS barrel-aged Red Boat fish sauce (Vietnamese, via Michigan); Delfino Colatura di Alici di Cetara (Italian); Red Boat 40°N or 50°N (Vietnamese)

Flour: King Arthur

Flour, chestnut: Allen Creek Farm

Grits: Anson Mills, Geechie Boy Mill

Hot sauce: Crystal, Texas Pete

Lentils, French green: Du Puy

Maple syrup, Indiana: Burton’s Maplewood Farm

Maple syrup, Michigan: American Spoon, barrel-aged BliS

Maple syrup, New Hampshire: Fadden’s

Maple syrup, Ohio: Pappy & Company (barrel-aged Bissell’s)

Maple syrup, Quebec, Canada: Remonte-Pente Sirop d’Erable

Maple syrup, Vermont: Hartshorn Farm

Mustard, Dijon: Fallot, Maille

Mustard, spicy brown: Gulden’s

Mustard, whole-grain: Tin (Brooklyn)

Nut oils: Hammons Products (Missouri: black walnut), Huilerie Beaujolaise (France: almond, hazelnut, pecan, pistachio, walnut)

Olive oil, extra-virgin, California: Arbequina, California Olive Ranch, DaVero, McEvoy Ranch Organic

Olive oil, extra-virgin, Greece: Naturally Greek

Olive oil, extra-virgin, Italy: Agrumato (lemon-pressed), Capezzana, Castello di Ama, Fontodi, Frantoio, Laudemio

Olive oil, extra-virgin, Spain: Miguel & Valentino, Valderrama

Paprika, smoked, Spain: La Chinata

Pasta, dried, Italy: Afeltra, De Cecco, Latini Senatore Cappelli, Martelli, Rustichella d’Abruzzo, Setaro (e.g., porcini)

Pasta, dried, New York: Sfoglini (Brooklyn)

Peanut butter: Koeze’s Cream-Nut and Koeze’s Sweet Ella’s Organic (Michigan)

Peppercorns, black: Tellicherry (India)

Rice, carnaroli (for risotto): Acquerello

Rice, short-grain: Koshihikari

Rose water: Cortas, Mymoun

Salt, kosher: Diamond Crystal

Salt, local (U.S./Mid-Atlantic): J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works

Salt, local (U.S./Pacific Northwest): Jacobsen Salt Co.

Salt, pink (Australia): Murray River Gourmet

Salt, sea: La Baleine, Maldon

Salt, smoked: Danish Viking, Maldon

Sorghum: Muddy Pond Sorghum Mill

Soy sauce, China: Koon Chun Sauce Factory Thin

Soy sauce, Indonesia: Conimex

Soy sauce, Japan: Kamebishi

The 40°N [fish sauce] is perfect for everyday use; the 50°N is wonderful for last-minute seasoning. Think of 40 as extra-virgin olive oil and 50 as cold-press extra-virgin olive oil, or fleur de sel: just a light sprinkling to finish a dish will do.

—CORINNE TRANG, author of

Essentials of Asian Cooking

We have a scallop dish on the menu with a squash brandade, fried Brussels sprouts, pomegranate seeds, and spiced pecans. The dish has been on the menu for three years and we have adjusted the brandade every time. This year, we did a blind taste test of nine different squashes from our farmer, because everybody typically gets the same butternut squash or pumpkin. When we tasted them, we found that the butternut squash and the pumpkin were the least flavorful. Pumpkin doesn’t taste like anything! So this year we are making the dish with delicata squash, which is fantastic. We are also using these huge banana squashes, which were my second favorite. This was a squash I had never seen before and did not know where else to get them, so we asked our farmer to only sell them to us so we can use them all year.

—STEPHANIE IZARD,

Girl & the Goat (Chicago)

Soy sauce, thick: Koon Chun

Soy sauce, thin: Wan Ja Shan (aged)

Soy sauce, U.S.: Bluegrass (Kentucky)

Spices, whole: Kalustyan’s (New York City), La Boîte (New York City), Spice House (Chicago, Milwaukee)

Tahini: al wadi (Lebanon), El-Karawan (Middle East), Soom (Philadelphia)

Tomatoes, canned, California: Bianco DiNapoli (from Chef Chris Bianco), Muir Glen

Tomatoes, canned, San Marzano (whole): La Bella San Marzano, La Valle

Tomatoes, preserved: Mount Vesuvius, Mutti, Pomi, San Marzano

Tomato paste: Muir Glen, Mutti

Truffles, black: Plantin (which also makes black truffle products, like mustards)

Truffles, white: Urbani

Vanilla and vanilla extract: Nielsen-Massey

Verjus: Fusion Napa Valley, Minus 8 Brix

Vinegar, artisanal: Jean-Marc Montegattaro (e.g., honey, quince)

Vinegar, balsamic: Aceto Manadori; Giusti’s Aceto Tradizionale, La Vecchia Dispenza, Villa Manodori

Vinegar, drinking: Pok Pok

Vinegar, flavored: Jean-Marc Montegottero (e.g., honey, lemon), Pok Pok (e.g., black pepper, pomegranate)

Vinegar, ice wine: Minus 8

Vinegar, sherry: BLiS barrel-aged 9-year-old, BLiS Extra Old Fine Solera Aged Sherry Vinegar, Noble XO refined finishing vinegar

Yeast, fresh: Red Star

Yuzu juice: Yakami Orchard

Stephanie Izard

Just because two components are amazing doesn’t mean that combining them will work. I have learned this lesson over and over.

—DANIEL PATTERSON,

Coi (San Francisco) and LocoL (Oakland and Watts)

FLAVOR COMPATIBILITY (e.g., X + Y + Z)

Beyond choosing the highest-quality ingredients available to you, you’ll want to cook with those that have a natural affinity for one another.

When you combine different ingredients, sometimes 1 + 1 does not equal 2—but it equals 3 or more. Think of the magic of tasting the first basil + tomatoes of summer—or the first beets + cheese + walnuts of winter. You can achieve these synergies between food and wine as well, as in the case of oysters + Sancerre, or mushrooms + pinot noir, or Roquefort + Sauternes.

Once you understand time-tested flavor pairings (two ingredients that are a match made in heaven) and flavor affinities (groups of three or more ingredients that harmonize well), you can use them as the building blocks to creating new dishes, new cocktails, and more.

Dominique Ansel [Boulud’s former pastry chef] approached classic American flavors with the naive curiosity of a student in his first cooking class: WHY do the combinations of peanut butter and chocolate—or Key lime and graham cracker—get people so excited?

—DANIEL BOULUD, The Dinex Group (New York City)

Each gin is as different as a different cut of steak or type of fish. Plymouth Gin is soft and delicate, so I’d never pair it with a bold flavor like ginger or chartreuse, but it would work well with Lillet. Tanqueray is a big, bold gin, on the other hand, so it could stand up to ginger or chartreuse. Beefeater has the largest array of botanicals, which pair well with citrus, like lemon and orange. Just as in food, you want to keep everything in balance and MAKE SURE YOUR INGREDIENTS DANCE WELL TOGETHER.

—AUDREY SAUNDERS, mixologist and owner, Pegu Club

(New York City)

But how on earth can you possibly know what flavors go well together? Isn’t that a lifetime’s worth of work to discover?

It used to be. Rocco DiSpirito wrote in his book Flavor that he remembers begging his instructors at the CIA for insights into what ingredients go well together before discovering our 1996 book, Culinary Artistry, our first book to chronicle classic flavor pairings.

Later, we expanded our exploration of food and drink synergies in our 2006 book, What to Drink with What You Eat, and then modern flavor synergies in 2008 with The Flavor Bible, and in 2014 with The Vegetarian Flavor Bible. Today, some of the world’s best chefs and cooks and sommeliers and mixologists turn to them to leverage centuries of historic wisdom in order to make better choices.

How do new dishes come into being?

I remember reading an interview with rising star chef Jeremiah Langhorne of the Dabney in Washington, D.C., on his “aha” moment of first realizing that kitchens could be a place of creativity. Having previously cooked only at McDonald’s, his job at a modest Italian pizza place was the first time he’d seen guys in the kitchen coming up with a dish. “I don’t know why, but it shocked me that you could actually create new dishes,” he’d told Washington Life’s Laura Wainman. “I literally thought that all dishes were just recipes that already existed, and the idea of making something new was mind-blowing to me at the time.”

Given our culture’s overwhelming focus on published recipes, with little attention paid to the process of creating them or of cooking without them, this made perfect sense to me.

Some dishes are so ever-present in our culture that they seem to take on a life of their own, making it hard to imagine a time when they didn’t exist. It’s too easy to forget that each of them began with a human being (or team of them) and a spark of inspiration—inevitably a desire or need (which is simply desire in a pressure cooker).

Through the examples that follow, you’ll see that some of the dishes you might take for granted each started with a spark of inspiration. Some of the most common sparks include pressure, product placement, pleasure, even providence—though they are by no means mutually exclusive.

Every great and iconic American dish has a STORY TO TELL.

—MICHAEL LOMONACO, Porter House

(New York City)

Pressure

Italian native Caesar Cardini found himself at the end of an especially busy July 4th weekend at his restaurant Caesar’s at the Hotel Caesar in Tijuana, Mexico, where he was able to escape the restrictions of the Prohibition era. His kitchen was caught short on ingredients, and with VIPs in the house (including the entourage of the Prince of Wales, according to folklore), the pressure was on. So he threw together a salad based on what he had on hand, including Romaine lettuce + grated Parmesan cheese + coddled egg + garlic croutons + olive oil + vinegar + mustard + Worcestershire sauce, finished tableside with a dramatic flourish. Cardini’s customers loved the show and the salad so much that, since that day in 1924, word has continued to spread about his Caesar salad.

Product Placement

Girl Scouts have been selling cookies to finance troop activities for the past century. In the 1930s, the Camp Fire Girls were looking for something they, too, could sell to raise funds. Kellogg’s home economist Mildred Day and her coworker Malitta Jensen were inspired by the popularity of popcorn balls held together with honey, maple, or molasses, the first recipe for which appeared in the 1860s. Day and Jensen substituted Rice Krispies (which Kellogg’s debuted in 1928) for popcorn, and concocted a melted marshmallow + butter + vanilla mixture as the edible “glue” to hold it together, pressing it into buttered sheet plans so it could be cut into squares when cool. The treat proved so popular that the recipe was printed on the sides of Rice Krispies boxes starting in 1941.

Pleasure

Michelin three-star chef Michel Bras loves to run, something he counts as a source of endless inspiration to his cuisine. He was running in the French countryside one particularly fragrant and flower-filled day in June 1978 when he was inspired to re-create the beauty of the moment on a plate. The result was an ever-changing signature dish he called a gargouillou [gar-goo-YOO] of young vegetables, which features a colorful array of as many as 80 different raw and cooked vegetables, flowers, fruits, herbs, leaves, sprouts, and seeds showcasing the local seasonal terroir and accented by spices (and a dry-cured slice of country ham), arranged on the plate in a way that suggests movement. His salad-as-seasonal-mosaic has since become one of the most imitated dishes in the world, inspiring customized offerings in Denmark (at René Redzepi’s Noma), Spain (at Andoni Luis Aduriz’s Mugaritz), and the United States (including at David Kinch’s Manresa).

Long runs in open space bring an amazing sense of well-being and fluidity. Aubrac is inhabited by silence and saturated with light, a perfect setting to feel the ever-changing cycle of nature. Sounds, colors, fragrances fill each moment with wonder, and every run takes me on an “inner trip.”

—MICHEL BRAS, Bras (Laguiole en Aubrac, France)

Providence

Sure, maybe there are even examples of dishes that were created when the hand of God intervened. There’s no telling whether all of these examples might have had a touch or more of providence behind them. But remember that each of these creations started with a human being—just like you—with a wish to create something new and delicious.

While the creative process can seem obscure or mysterious, it’s also very human—people like you, dealing with everyday life, including sparse refrigerators coupled with hungry guests. So don’t sell yourself short. You never know what you’ll be able to create until you try.

YESTERDAY’S AVANT GARDE, TODAY’S TRADITION

Today’s classic dishes were the cutting-edge of creativity at another point in history—so they’re worth studying. It can be surprising to realize how long some dishes and techniques have been around—and how relatively new others are. Many origin stories of dishes are unknown or contested. Precious few are crystal clear. But all of them can provide food for thought when creating your next dish. The proof of flavor affinities is in the tasting.

The culinary world learned a lot before—and since—the nouvelle cuisine revolution of the 1960s and 1970s and the molecular gastronomy movement of the turn of the 21st century, and we shouldn’t let the lessons of centuries of trial-and-error go unheeded. If we’re smart enough to learn from our ancestors’ mistakes, we can free ourselves to make new ones!

And most importantly, you’ll want to internalize the principles of—and be on the lookout for—the patterns of creation, including necessity (which can indeed be the mother of invention, as exemplified through the origins of many classic dishes, from Buffalo wings to nachos), accidents (like chimichangas, which were thought to be the result of knocking a burrito into a deep-fat fryer), and mere happenstance.

The avant garde of today will be tomorrow’s tradition.

—ALBERT ADRIÀ, Tickets (Barcelona)

In cuisine as well as in design, architecture, and art, what survives is timeless. You can’t define it in the moment—it must be defined later, in time.… In the same way, you don’t decide what is your signature dish—your guests decide.

—GABRIEL KREUTHER,

Gabriel Kreuther (New York City)