CHAPTER 2 |

“Take the Christ out of America, and America Fails!”: |

My nature is serious, righteous and just,

And tempered with the love of Christ.

My purpose is noble, far-reaching and age-lasting.

My heart is heavy, but not relenting;

Sorrowful but not hopeless;

Pure but ever able to master the unclean;

Humble but not cowardly;

Strong but not arrogant;

Simple but not foolish;

Ready, without fear.

I am the Spirit of Righteousness.

They call me the Ku Klux Klan.

I am more than uncouth robe and hood

With which I am clothed.

YEA, I AM THE SOUL OF AMERICA

—DAISY DOUGLASS BARR (1923)1

Three times, on his bended knee, with his right hand raised to high Heaven, and his left hand placed over his heart; in the presence of a sacred altar. Over the top of the altar was spread the American flag, and on top of the American flag was laid the Holy Bible open at the twelfth chapter of Romans; hanging aloof was the “fiery” cross, symbol of the Christian religion; with still another American flag unfurled from a staff, and the beauty and splendor of its wonderful standard blowing in his face. In this position he took the oath thrice binding him in solemn loyalty and serious pledge to support the laws of the city, state and nation. Therefore a Klansman, bound by patriotism[,] which inspired him to become a member and then by a three-fold oath, is pledged to the great government of the United States over and above any and every government in the whole world. He pledges his life, if necessary, his property, and his sacred honor to the unfaltering purpose of perpetuating our great American country, the most dauntless lineage known to man.

—“TO THE CITIZENS OF WAYNE COUNTY” (N.D.)2

On bended knee, each Klansman pledged allegiance to patriotism and dedicated his life to the perpetuation of “our great American country.” Americanism, more particularly 100 percent Americanism, was a rallying cry for the 1920s Klan, and members prostrated themselves in front of altars of Americanism, complemented by the flag and the cross. Both the flag and the fiery cross were part of the “seven symbols” of the Klan. The American flag was an unsurprising symbol, one with an obvious and long-standing tie to patriotism.3 The fiery cross, however, seemed to demonstrate more the order’s uplifting of Protestantism and religious belief than its national character. Yet the Klan envisioned both of those material artifacts as signifiers of nation.

The Starry Flag and the Fiery Cross Shall Not Fail. Four Georgia Klansmen present the Fiery Cross and the American Flag, two of the seven symbols of the order. Courtesy of University of Georgia Hargrett Library, Athens.

The flag, “purchased by blood and suffering of American heroes,” articulated the “price paid for American liberties.”4 For the Klan, like other Americans, it was a symbol of liberty, democracy, the Constitution, free speech, freedom of worship, and the rights of citizens. The flag was a fabric symbol of American character. For W. C. Wright, a Klan minister, the colors of that emblem presented American values and history. The red stripes uplifted “the bravery and blood” of all who fought for liberty. The white stripes symbolized “the sacrifice and tears of American womanhood whose husbands and sons paid the price, as well as the purity and sanctity of the American home.” The blue was “but a path of America’s unclouded sky, snatched from the diamond-studded canopy that bends above our native land.” Finally, the stars illustrated the union of the states.5 Each component of the flag communicated the character of the nation, its people, and its romanticized geography. The artifact provided a nostalgic view of the country and its beneficence.

The Kourier reported that the flag was a gift from the forefathers presented to subsequent generations as a representation of liberty. The “Glorious Banner” connoted both liberty and law, yet the monthly purported that Old Glory was denigrated by ignorance of both. The monthly configured the meaning of the banner theologically. Red equaled devotion, which might have required “the shedding of blood.” The Kourier printed, “We love Jesus because He shed His blood for us, and we love the Flag because it represents the blood shed for our freedom.” The white signified purity, intelligence, and citizenship. The stars in the field of blue no longer indicated a commitment to the Union but instead the realm of the metaphysical. Those stars “stand for Him Who is back of the stars in Heaven above.” The Kourier continued, “We may not all understand God alike, but we do believe there is a God, and we must admit that the bases of America’s Laws are the great moral laws of God. When any man turns his back on God[,] he turns his back on the Flag.” Thus, the banner connoted not only American history but also the relationship of God to the American nation. The quintessential American symbol reflected divine guidance in American history, and it also affirmed that the belief in God was essential to citizenship. The monthly, however, was not promoting a universal God that would be inclusive of citizens of all faiths. The Kourier understood Christianity as an important part of Americanism and expounded that “pure Americanism can only be secured by confidence in the fact that the Cross of Jesus Christ is the wisest and strongest force in existence.”6

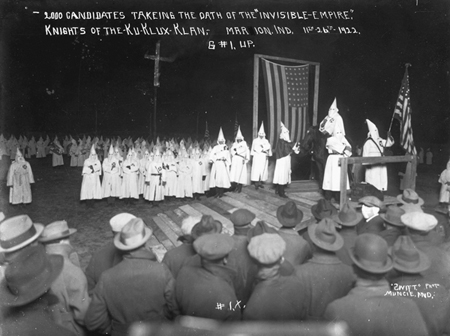

Two thousand candidates take the oath of the Invisible Empire in Marion, Indiana, 1922. Photograph by W. A. Swift. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

For the Klan, Christianity constructed nationalism, and the flag and the cross were artifacts of both religious faith and devotion to the nation. Daisy Douglas Barr, a Klan poetess, wrote that the Klan was “more than uncouth robe and hood”; it was “the soul of America.”7 The Klan was represented as savior and soul of the nation. The questions her poem begs prove intriguing: What if we take seriously the claim that the Klan was the “soul” of 1920s America rather than just the proclaimed “savior”? What if we understand that nativist movement as a nationalist one instead?8 By overlooking the impact of Protestantism on the order’s nationalism, previous historians have obscured the intimate relationship between faith and nation in 1920s America. Millions of Americans found resonance in the Klan’s vision of white Protestant America, and they wore robes and burned crosses. They supported the Klan’s homogenous, antipluralist construction of the nation and its people. Both presented the theology of the movement as well as its imagining of what America should be. Average, ordinary citizens found resonance in a movement that claimed to be “soul” and “savior” of American culture. Those people believed if the Klan was the soul of America, then faith and nation were inseparable. Robes, flags, and crosses demonstrated how the Klan welded Protestantism and Americanism together into a cohesive whole. To understand those artifacts and renderings of Americanism in Klan print complicates narratives of American religious history in the 1920s by suggesting that faith and nation were not as separate as we might like them to be. Religious exclusion and antipluralism were the foundations of this particular vision of the nation.9

Klansmen proclaimed Protestantism, and their Americanism reverberated with religious overtones. From their view, America was primarily Protestant, and the Klan romanticized the Founding Fathers and their “Protestantism” as the keystone in the creation of America. The Night-Hawk and the Kourier urged Klansmen to be defenders of the faith and Americanism by carrying the fiery cross. That faith dictated the behavior of members on personal and collective levels. The newsmagazines also confirmed the Klan’s vision of the world, and its printed words sought to define a textual community of believers in homogenous faith and a particular vision of America. The cross, like the flag, articulated the order’s form of nationalism, which emphasized faith as essential to the character of the nation.

By the fire of Calvary’s cross.

William Simmons, the first Imperial Wizard, added the fiery cross to 1920s Klan’s rituals, though Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman (1905) introduced the idea of the burning crosses as a part of the Reconstruction Klan’s mythology. In that literary work, the cross bound the American Klan to the Scottish clans of lore. Dixon used that connection to place the order to a larger history of Anglo-Saxons. More practically, in the novel the lit cross functioned as a tool for Klans to communicate with one another. Much like the robe, the 1920s Klan re-crafted the fiery symbol from Dixon’s staging to present its twin messages of Americanism and Protestantism. The cross harkened back to the Klan’s Protestantism and the magnitude of Jesus’ selfless sacrifice on the cross. It reflected the heritage of Protestantism as “the symbol of heaven’s richest gift and earth’s greatest tragedy.”10 As one of the seven sacred symbols of the Klan, “this old cross is . . . a sign of the Christian religion,” which was “sanctified and made holy nearly nineteen hundred years ago by the suffering and blood of the crucified Christ, bathed in the blood of fifty million martyrs who died in the most holy faith, it stands in every Klavern of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan as a constant reminder that Christ is our criterion of character.”11

The cross magnified Christ’s importance as the archetype for a Klansman’s behavior. The wooden object was a memorial of Christ’s debt for human sin as well as his merit-filled actions. In a poem praising the fiery cross, an Iowa Klansman noted that its light indicated that the universe was firmly under God’s control and, moreover, that God would “redeem and regenerate the world.”12 For the Iowan, the cross suggested that “good,” the Klan, would triumph over any “evil”: immigration, alcohol, threats to the public school, attacks on Protestantism, Catholicism, Bolshevism, and Judaism, to name a few. The artifact reassured the Klansman that the universe was structured in the way he hoped. Its glow symbolized a world in which the Klan was the singular force of good and the order would triumph.

The fire signified that Christ was “the light of the world.” That light vanquished the darkness and superstitions, though it was a beacon of truth for Klansmen only. (Victims of the order did not necessarily recognize the religious vision of the cross but rather the fear and terror the Klan inspired.) “The fire of Calvary’s cross” purified Klansmen of their human sins. Much like fire purified the basest of metals, the purification process “burned off” vice, leaving only the glowing presence of virtue behind. An Exalted Cyclops reflected, “Who can look upon this sublime symbol, or sit in its sacred, holy light without being inspired with a holy desire and determination to be a better man? ‘By this sign we conquer.’”13 For the Exalted Cyclops, the cross inspired Klansmen to become more religious, dedicated, and determined. The glowing light of the cross not only stirred members to be better men but also indicated their need to conquer forces opposed to them. To conquer, I think, was an obvious goal of the Klan. The order hoped to reconquer the nation in the name of Protestantism and “100% Americanism” and envisioned its battle as a crusade for the nation and its way of life. After all, members imagined themselves as Knights in white robes who marched under the glow of a burning cross. According to the Night-Hawk, Christ’s light emanated from the fire, but the cross was also a sign that “rall[ied] the forces of Christianity” to conquer the “hordes of the anti-Christ,” as well as the “enemies” of Americanism.14 The artifact was both beacon and warning. For Klansmen, its glow provided comfort, but for those “enemies,” the fire terrified.

The cross was explicitly bound to the cause of “100% Americanism.” Its theology focused on the actions and death of Jesus as well as the exclusion of all those who were not (Protestant) Christian or American. Its glowing presence was an ominous signal to those who “threatened” the nation. The Night-Hawk claimed that the object was the “emblem of real Americanism” and “flashed its message of a Nation Reborn.”15 The “Nation Reborn” was one in which faith adhered to nation. The rebirth affirmed what Klansmen believed was the foundation of nation: white Protestantism. Faith built the exclusionary boundaries of its nation, which marked certain religious traditions and races as unable to assimilate. For the Klan, Catholics had allegiance to a foreign entity, the pope; Jews refused to assimilate; and African Americans were a “lesser” race that could never reach the great heights of the Anglo-Saxon. All of those groups proved threatening to the “glorious” nation. For Imperial Wizard Evans, a goal of the Klan was to preserve the “good government.” He argued that preservation required “maintaining a Christian civilization in America.” For Evans, “Pre-eminence is enjoined upon us by God and by our obligations to the world. If the Klan aspires to purify America and make her impregnable, it is not any selfish reason.”16 The reason, instead, was divinely ordained. America, in all its glory, needed to maintain its Protestantism or the future of the nation might be in peril. By wearing white robes and waving the flag under the light of the fiery cross, Evans and his Klan hoped to restore the faith in order to save America. Their nation was in danger, and the only way to save it was to reconnect with the nation’s religious foundations. The accounts of the flag and cross were purposeful discussions of what each should mean. Both artifacts articulated the Christianity of America to point citizens in the correct direction and to verse them in the Klan’s ideology. To illuminate the correct path, the Klan defined its Americanism in opposition to cosmopolitanism in retellings of national history and in defense of the public schools.

The Klan embodies the group mind of America.17

In order to be a Klansman, a member had to follow the principles of “klannishness,” which included patriotic, domestic, racial, and imperial klannishness. For patriotic klannishness, the Klansman had to devote himself to allegiance of pure Americanism, liberty, truth, and justice. According to Imperial instructions, “real, true Americanism unadulterated, [included] a dogged devotedness to our country, its government, its ideals and its institutions.”18 That nationalism required the uplifting of the country and government by all Klansmen, which also included the protection of the precious ideals. The order’s message of Americanism contained menacing overtones because the nation appeared, at least to Klansmen, to be in grave danger. The speeches and articles of Imperial Wizard H. W. Evans tempered the hope present in the writings of Simmons. Evans feared the downfall of civilization and assessed the constant threats to American character. He argued, “We must look first at the crisis in our civilization, now near its height. Americans find today that aliens . . . instead of joining, challenged and attacked us. They seek to destroy Americanism.” The nation was in crisis, and the Klan needed to confront those problems to save civilization and “the American stock.” Evans continued, “The Klan embodies the group mind of America. It is representative of complete nationalism. It is not sectional, it is not personal, it is not selfish, it does not represent any private interest—it speaks for all America.”19 The Klan’s goal was to be the voice of patriotism and to safeguard an imperiled nation. The order believed that it was representative of average Americans and their concerns.

Of course, the Klan was not representative of “all America.” Instead, members presented their interests above the welfare of those who did not qualify as “true” citizens. Moreover, Evans characterized the Klan as the “group mind” of America, which suggested a collective spirit of all native-born citizens who molded their thoughts, actions, and words. Nationalism would not be effective without that group mind. Evans argued that America’s particular nationalism contained six vital elements: the “fighting instinct,” unity of kind, independence, public spirit, common sense, and conscience. Men of the “American race” were fighters who loved their “kind,” meaning whites or Anglo-Saxons. The American was also inventive and independent, but that independence did not interfere with a sense of public responsibility. In regard to common sense, Evans penned, “Ours is no race to deal with fine spun theories, no race to allow our purposes to be thwarted.”20 And finally, conscience guaranteed the highest standards for home, faith, and nation. Those elements highlighted the superiority of both America and her people, but for the Imperial Wizard, the “Cosmopolitan movement” threatened her virtues.

“Cosmopolitanism” was an umbrella term for many of the movements that Evans and his Klan identified as threats. The term referred largely to various attempts to create understandings of a “citizen of the world unbounded” by national constraints.21 For the order, Cosmopolitan movements included political ideologies (Communism, Socialism, and Anarchism) as well as religious traditions (Judaism and Roman Catholicism). For Evans, those Cosmopolitans all had group minds that proved oppositional to the American values. Evans relayed “four different types of people” who sought to destroy America: Jews, Celts, “Mediterranean peoples,” and “Alpines.” He noted material things consumed the Jews, who had their own form of ethnic and religious nationalism that trumped commitment to American nationalism. In his writing, the Celts, Mediterranean peoples, and Alpines were unstable, uneducated, and, above all, devoted to the Catholic Church. Because of their development in Europe, their lack of education, and their loyalty to the church, those groups differed too drastically from the American group mind, such that they could not assimilate to the norms and mores of the nation. Evans wrote, “The group minds of other races and other nations have developed differently from ours. Each nation has its own God-given qualities and its own mission.”22 Nationalism, then, was “the right of each nation to develop the genius and instincts with which God endowed its people.” That understanding of nationalism uplifted patriotism, uniformity, common language, common religion, respect for the government, and common tradition as well as history. With his rendering of nationalism, Evans emphasized qualities that he thought were essential to the development and maintenance of a nation. Uniformity emerged as a necessity in order to avoid conflict and strife. He wrote, “True nationhood is essentially oneness of mind, and it recognizes certain beliefs held in common by its citizens. . . . No person who lacks them can be in harmony with the nation.”23

Aliens, or foreigners, were the greatest threat to the unity of mind, or Americanism. For an Iowa Klansman, Americans were first and foremost nation builders; foreigners were not. Americanism fostered native-born Americans, and it was not was easily learned. He categorized an American as “one who lives in America, and lives for America and will die for America,” and “whose oath of allegiance is to America above any other government, civil, political or ecclesiastical in the whole world.”24 “True” Americans upheld their country before other allegiances, and they were committed to fulfilling the destiny of the nation. Evans argued that Americanism “was bred into us—native, white, Protestant Americans—it was suckled with our mother’s milk, absorbed in our homes, learned in our schools, breathed into the very air.”25 Americans were born, not naturalized. The Klan suggested that Americans could not be created through immigration legislation, since the group mind was akin to instinct. Klansmen knew American principles by nature and inheritance, which the order believed cemented members’ roles as protectors of nation. The destiny of the nation depended on native-born Americans who had a clearer sense of their nationality.

That destiny included more than patriotic duty. It also included uniformity in (Protestant) Christianity and white supremacy. The Anglo-Saxon heritage of the Klan, and of America, directly resulted in the greatness of the nation, and racial purity ensured the maintenance and development of the group mind. Americanism, then, was not simply about democratic government but also about the racial superiority of whites. Aliens would destroy the group mind as well as democracy, a cherished American ideal. The Klan’s vision was not pluralistic, for sure. The order noted that it was the representative of true Americanism. The Klan was “founded upon, and represents, those deep instincts and qualities of our race which have led us to high achievement.” Klansmen also believed that their order was representative of the whole of Protestantism. Evans wrote: “This unity between Americanism and Protestantism is no accident. The two spring from the same racial qualities, and each is a part of our group mind. Together they worked to build America, and together they will work to preserve it. Americanism provides politically the freedom and independence Protestantism requires in the religious field.”26

Protestantism was a central element of that form of Americanism because it proved essential in the creation of the nation. In addition, the religious movement helped define the all-important group mind. Freedom emerged politically from nation and religiously from Protestantism, a merger that produced the unique mind of Americans. Evans and Klansmen envisioned Protestantism as a major force in the history of the nation. They looked to its influence on the founders and other major historical actors as a sign of Providence in the formation of America. Americanism had sacred elements because God had made “the native Americans distinct from other peoples.”27 Americanism and Protestantism were unified because, at its core, America was a Protestant nation. To show that unity, the Klan strove to tell history in a way that reflected the divinity of the American mission.

The soil of America was consecrated by the Pilgrim Fathers.

A pamphlet entitled The Menace of Modern Immigration reported that God had favored America: “He [God] fashioned this land in surpassing beauty and placed in it and upon it a varied, exhaustless store of resources.” The nation and its bounty remained hidden until the “best” settlers could arrive and cultivate the land. The pamphlet continued: “To this Eden journeyed the best and the bravest of the Old World. . . . There was a double refinement of these pioneer patriots, first through their strength and courage required for their emancipation abroad, and then in their triumph over the dangers and adversities of a virgin environment.”

The focus on pioneer patriots, who conquered America with divine assistance, deemphasized the historical presence of indigenous peoples and the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus, a Catholic.28 The pamphlet overlooked historical veracity to tell the story of America founded by patriots who were “physically, mentally and morally virile, with an inherent, kindred reverence for rightly established institutions.”29 The nation was a blank canvas ripe with possibility, which was painted skillfully by those settlers only. The “bane” of immigration had degraded the canvas, and the only way to restore the possibility and the beauty was for native-born Americans to realign with their destiny. Restoration and redemption lay in the hands of the native-born. Klan leaders, newspapers, pamphleteers, and ordinary members bore the responsibility of redemption. Through print media, the Klan avidly molded the history of the nation to reflect its values and concerns. The order sought to demonstrate that America, from inception, had been a Protestant nation and to illustrate how important historical actors held similar opinions to Klan leaders.

The Imperial Night-Hawk and its contributors analyzed the issue of Americanism and how it was intricately wed to the religious founding and destiny of the nation. In an article reprinted from the American Standard, the author reflected on the nature of 100 percent Americanism, and he produced a Christian foundation for that particular form of patriotism. He opined, “America’s idealism, institutions, destiny, and affluence are written in the [B]ible, and upon this Book, the Work of God, America is founded.” Americanism, then, was centered on the nation’s religious foundation, and one could not be a citizen without recognizing that “truth.” His article was a jeremiad, a lament about the decline of the nation and the forces aligning against it. For the author, the nation was in peril if Americans did not realize the sacred status of the peculiar place. All of the “great” documents (the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Monroe Doctrine) originated from the Bible, and “therefore these documents are the basis of the logic and demonstration of every American problem.” Christianity thus permeated American culture, and the land became sacred as well. “The soil of America was consecrated by the Pilgrim Fathers with the words, ‘in the name of god, amen!’” The nation was exceptional in origin, doctrine, and even physical space. The distinctiveness did not entirely emerge from divine beginnings but rather from America’s separation from the corruption of the “old world.” The Monroe Doctrine proved significant because it “declare[d] the unique character of the American System and its inevitable separateness from the system of the old world.” The author’s emphasis alluded to his most important point: the labors of “white, Protestant, Anglo-Saxon Americans” created the country and nationalistic fervor.30

The greatest threat to the divine nation came from Old World machinations, in particular “the politico-ecclesiastical despotism of Europe” and “the Roman Catholic system of political control.” The Roman Catholic political machine had an elaborate hierarchy: hundreds of thousands of lay members, Knights of Columbus, priests, “crafty Jesuits,” cardinals, and a pope with the power to control them all. In the article, Roman Catholicism equaled tyranny and proved threatening to the promise of the New World. The author confirmed “the lives of the early fathers and their writings reveals [sic] that America was established by Christ . . . to put an end to ‘their System’ . . . Romanism.” The Founding Fathers were opposed to that political system masquerading as religion. For America to survive and manifest her glory, Americans had to “break these alien bonds.”31 Divine providence was bound to the actions of white Protestant Anglo-Saxon Americans. In Klan retellings of American history, those true Americans were the heroes, and Catholics and others were excised from historical records. Americanism was Protestant Christian, and the order generalized the “forefathers” of the nation into Christian patriots.

For instance, an Arkansas Klansman presented the “builders” of America as “Christian pioneers.” Those Christian men laid the foundations for all that was valuable in American life, including the freedom of speech and religion. For that Klansman, it was essential to look to the example of those founders because the nation was endangered. He wrote: “America is the great nation she is, because she was born of Christian ideals, and because she is in no small way moved by them. Take Christ out of America, and America fails! Take the freedom of the Protestant Christian religion from us and expect another St. Bartholomew’s massacre.”32

America was a nation that would suffer if Christianity was removed or denigrated. The Klansman noted the order’s role to protect America from alien influences and preserve its Christian character. Not surprisingly, members observed similarities between their actions in the twentieth century and the actions of the forefathers. One Klansman observed that the Boston Tea Party might have been the “first Ku Klux Klan meeting on record.” He reflected, “The members masked. They did a bit of night work, made an immense pot of tea, liberty tea at that. King George tried to break up the Klan.”33 The king, of course, did not succeed because of those patriots who masked themselves in the name of liberty. The task of the Klan, then, was to embrace the legacy of historical actors who molded the nation and its character. It did not just imagine historical actors as exemplars but also re-created various historical events to show continuities between those figures and the Klan.

In the October 1926 issue of the Kourier, W.A.H. compared H. W. Evans, the Imperial Wizard, to Abraham Lincoln to show striking commonalities in character. Both were “products of pioneer Americanism.” They were fighters and leaders who preferred simple language. The author noted that both were fair. He affirmed, “Hiram Wesley Evans could well be called his [Lincoln’s] reincarnation.”34 The purported eerie similarity was not as significant, however, as what Evans’s relationship with Lincoln signaled. To make the comparison demonstrated that a Klan leader was wed to a quintessential American leader, which illustrated the Klan’s ties with the mainstream as well as the order’s place in American history. To further make the case, the Imperial Night-Hawk ran a series of articles about historical “One Hundred Percent Americans” that illuminated the resonance of Klan values with other influential historical figures. The Puritan sage, Jonathan Edwards, merited his own article, which emphasized his education, sermons, influence, and his removal from the Northampton pulpit. The Night-Hawk suggested, “Jonathan Edwards would have made a staunch Klansman” because “he preached the love of God.” Moreover, he lived the Klansman’s creed—“Be not overcome of evil, but overcome evil with good”—by not showing “any resentment” in his farewell sermon.35 What was notable was not whether Edwards would have been a “staunch Klansman,” though that might prove interesting, but rather that the weekly strove to convey his resonance with the order. Such was a blatant attempt not only to recraft historical actors to fit the Klan’s mold but also to establish a longer historical lineage for the order. If the order and its members could trace the origins of its ideas to forefathers, the Pilgrims, Edwards, or even Lincoln, the Klan was the logical extension of mainstream cultural currents. The tactic gave the order cultural legitimacy and placed its members as the common inheritors of Americanism. In retelling history, Klan print culture crafted Klansmen and Klanswomen as the culmination of founding ideals, aspirations, and events. Those inheritors embodied the “legacy” of white Protestant Americans who created and fostered the nation from its earliest moments until the 1920s.

In that imagining of American history, the forefathers of the nation fought and spilled blood to create a country explicitly for native-born Americans. In a textbook for Klansmen entitled Bramble Bush Government, the author highlighted significant events and institutions for the country, including Moses’s parting of the Red Sea, the settlement at Jamestown, the American Revolution, and the Civil War. Those events defined American character, and the parting of the Red Sea, I think, signified the divine heritage of the nation that could be traced from biblical origins. Each event proved notable because each was a moment in which Americanism was forged. Divine guidance, first settlements, and wars all changed the course of history, and the spilling of blood made values tangible and sacred. The bloodstained heritage made native-born Americans unique from their immigrant brethren because they were born and matured on consecrated soil. For the author, the native-born should have immense pride in their nationality and heritage because their nation was special and quite different. He wrote: “No people should be as proud of their heritage, their traditions and forbears as America’s native sons. Why? Because in their veins run the courage of the Pilgrims, the bravery of Boone, the wisdom of Washington, sagacity of Franklin, the nobility of Lincoln and Lee. Surely the blood of kings and potentates could be no more royal.”

Native-born Americans were part of an aforementioned legacy that made their nation singularly great, and they were to strive to preserve it from impurity. The author continued that the land, then, was not for “the refuse populations of other lands.” The Pilgrim fathers worked and suffered to transform a “stern and rockbound coast” into a civilized country.36 The “refuse” had not civilized the wilds of the nation: they hoped only to take advantage of the toil of the forefathers and pioneers. The author downplayed the fact that the builders of the nation, including the Pilgrims and the settlers of Jamestown, were immigrants as well. They were not born on native soil, yet those immigrants were coded as beneficial, while the other waves of immigration in the early twentieth century were viewed as “refuse.” The early immigrants were transformed through alchemy. As soon as founding immigrants stepped foot on the soil that became America, they became the natural inhabitants of the land, which purified their Old World elements. The divinely crafted land was made just for them, and these “white, Protestant” settlers fashioned the nation. One of the faults of the founders was that they never created a movement to safeguard the nation; that responsibility became the burden of later generations.

The Kourier reported, “Our forefathers should have started a great Christian American citizen’s movement, in connection with the new or American government. . . . But they did not do it, and the Klan got started very late in the process—but it is working day and night to save our civilization.”37 According to the monthly, the forefathers might have intended to create a movement that mimicked the order, but they did not. That responsibility, then, was left for the Klan. The creation of the order was fortuitous because the Klan and its leaders envisioned that they were continuing the mission of the founders to protect a white Protestant nation from the threats of Catholics, Jews, African Americans, and “hyphenated Americans.” In the order’s perusal of the American landscape, the providential nation was in threat of annihilation, and all along the landscape threats were apparent and imminent. They envisioned themselves as saviors of the nation, and the public schools quickly became a foremost battleground. By examining the Klan’s dedication to the preservation of the Bible in the public school, one can see the order’s commitment to a Christian nation and its rendering of national character. The threat to public education was essentially a threat to nation. To lose the schools would be a death blow to the order’s defenses. Schools trained future citizens, and the Klan wanted the public schools to remain firmly in the purview of white Protestants.

The American Public School is the Safeguard of American Liberty.38

Mrs. J. W. Northrup, a contributor to The New Age, lamented the decline of the public school, which she noted had to be “dear to all Americans.” For Northrup, the public schools were “where tiny minds begin to soar, where great men and great women of this country first learn the alphabet that leads to fame.” The public schools made children patriots, trained them for greatness, and informed them of the character of their nation. This patriotism, fostered and nurtured in the public school system, should have included Protestantism. Northrup’s frustrated lamentation hinged on the lack of God in public education. She wrote vehemently: “Any intelligent Protestant knows when you educate a man to believe he can be saved without the living God, that he is not a true American citizen, for it is impossible to be true to this country and at the same time believe that his existence on earth and in eternity depends upon a foreign mortal. . . . Americans arouse yourselves; don’t be cowards, for God hates nothing worse than cowardice.”39

Mrs. Northrup’s infuriated opinion piece crystallized the Klan opinion on the place of religion in public education. Her jeremiad was reprinted in full for the readers of the Night-Hawk. In her article, American citizenship was intimately bound to the belief in God, and American citizens could not be a people who believed instead in a foreign mortal (quite obviously the pope). Devotion was to be directed to divinity alone. She challenged her fellow Americans to move past their cowardice and protect “the little red schoolhouse.” The Klan echoed Northrup’s concern over public education in its print, and the order feared the removal not only of God from the schoolhouse but also the Word of God, the Bible. The public, or common, school became a sacred institution that inculcated children with a sense of American history, citizenship, and belief in God, and the Klan saw the public school as the front line to protect its threatened ideals.40 In that battle, the order spilled much ink to show its textual community the danger to the public schools and the ramifications for its beloved nation.

Not surprisingly, the Klan’s defense of the public school began with the forefathers of the nation. “The condition that existed in the early history of the Nation forced our forefathers to the conclusion that something must be done to unify the ideals of the people.” The “early settlers” came to America for freedom and democracy, and thus they created a system that indoctrinated those principles and emphasized the unity of language. Moreover, the public school was instituted “so that the children of the rich and poor alike might have the same opportunity by being placed on a common level and so counteract that inequality with which birth or fortune otherwise produce.” This ideal vision of the common school furnished opportunities to all children in spite of socioeconomic status and gave them a chance to absorb the value and character of America. It was equalizing, patriotic, and necessary. Yet this form of schooling did not materialize out of a vacuum; rather it had precedence within religious institutions. The Kourier observed that the earliest schools emerged from churches and that the schools in America “were clearly the fruits of the Protestant Reformation.”

Specifically, the Reformation shifted the approach of schooling by uplifting the Bible as crucial to personal salvation. The reformers focused on personal salvation, which fostered the importance of personal responsibility, which stood in opposition to the “collective authority” of the Roman Catholic Church. More important, responsibility for one’s salvation made reading a necessity because “one might know what the commands of God were and what was demanded of him.”41 If reading was essential for salvation, then schooling was required to train pupils in this religiously mandated skill. For the Klan, even the prominence of reading and schooling separated Protestants from Catholics. With reformers highlighting the need for schooling, the Pilgrims brought a commitment not only to religious freedom but also to education when they landed on American soil. They established homes free of “dictations of a paternalistic nature” and created “little town governments loosely bound together in colonial federations.” Education was their project, which began as a voluntary endeavor and evolved into laws that “compelled children to be educated.” For the monthly, the Pilgrims were essential to the development of American character because their “contribution” was an “institution so essential to her [America’s] progress and welfare, The American Public School.”42

The Kourier also examined the forefathers’ contribution to the common school. The monthly reported that the forefathers “planned our public school system as one of the foundation stones of our liberties and claimed the right of the state to educate her children.” The public school system was imperative to creating new American citizens well versed in the liberties they were guaranteed. That Kourier article did not focus on the religious basis for the school system but rather the function of schooling to create a solid American citizenship. The explicit aim of the institution was to foster “effective manhood and womanhood and prepare for good, useful citizenship in the various duties and callings of life.” The school created good citizens, which affected the relationships of the nation to the rest of the world. The monthly argued that “the Public Schools of America have changed the mental equilibrium of the world” and produced “our best men, our strongest patriots, our sweetest daughters and our most devoted mothers.”43 Patriotism was a masculine act, but the schools also produced well-mannered daughters who became devoted mothers. The Imperial Night-Hawk lauded the public schools for evolving from the “schools of our fathers, wherein we taught the elements of education—loyalty to God and to our flag”—to more modern institutions. The common schools laid the foundation for patriotic citizenship. Schools taught children that God and flag were components of their lives and their future development. However, the Klan organ questioned the large amount of change in schooling and pondered, “Are our children developing Christian character? Are the right principles being brought to bear on their lives?”44

Modern schools appeared ill-equipped to replicate the values of the “schools of our fathers.” The Night-Hawk called for school reform to align the current system with its predecessor, which emphasized loyalty to God and loyalty to nation. The development of the nation depended on children, and the Kourier noted, “The life blood of the Nation pulses no less in the veins of our children of the elementary school age, than those of adult life which fill the places of leaders, and of the rank and file in business, industry, commerce and professions.”45 The schools represented a safeguard to American ideals and liberties because those institutions inculcated a sense of nation in the young minds of their pupils. For the order, children became blank states to be molded into effective citizens in the venue of public education. Religious historian Robert Orsi noted, “Children represent the future of the faith standing there in front of oneself.”46 Children, then, were the new faithful, and they represented both peril and promise. In their small hands lay the fate of the faith and the nation. These small citizens had the ability to follow in the paths of their parents or shun them in favor of their own way. Children represented a future plagued with uncertainty. For the Klan, children embodied the future of the national ideals, and children proved to be a valuable resource for creating the nation that the order wanted. It is not surprising that the government did not necessarily educate children “for their own sake, but also for its own.” Education molded the young minds in the dictates, values, and history of the nation, and the Klan wanted to make sure that what children were being taught resonated with the Klan’s vision of America. Children were symbols of a future, and the order strove to influence public education to reinstate a Protestant Christian America in the minds and hearts of the nation’s young citizens.

For Imperial Wizard Evans, children were “the greatest asset to the state” and the “hope for a glorious national future.” The development and grandness of the nation rested on the small shoulders of American children, and the Klan’s energies focused on those children learning certain historical events in the hopes of producing legions of patriotic children who would become patriotic adults. Evans continued, “What nation shall be the greatest among the nations of the ‘New World’? That nation shall be the greatest that puts children first in its thought, in its politics, in its economics, in its ethics. The nation that accepts the leadership of little children.”47 The children were to be both immigrant and native-born, and their schooling would guarantee the nation’s legacy.

The centrality of this legacy meant the Klan complained about educational funding, as it was so small compared with the benefits of enriched, future citizenship. In 1924 the Klan supported a law in Congress that would guarantee “every child, native, naturalized and foreign,” would receive “a common school education.” The Klan was not as progressive as it might have seemed. For the foreign children, the goal was “equipping these future citizens with the proper material for successful co-operation of American children in . . . the affairs of the country.”48 With the order’s support of the educational bill, Klansmen assumed that Protestant native-born children would be more privileged. The Klan contributor opined, “It is natural to assume that the Protestant children of the United States will receive proper attention and adequate tutors will be provided with funds supplied by Federal authorities.”49 The equalizing vision of the early public school disappeared because of the overwhelming desire to protect white Protestant America. Protestant children were the backbone of the nation, and they were to be treated as such.

Yet those “little children” were not to be leaders in their own right. Rather, they were to be groomed by public education to be obedient, strong, patriotic, and devoted citizens. The Klan strove to craft the public education system to produce forbearers of nationhood. Upon small shoulders rested the fate of the nation, and the order did not take the situation lightly. Its anxiety over the school reflected paranoia about what would happen to the nation if the schools did not represent the intentions of the forefathers or Pilgrims. What would happen to the nation if the burden was too great for “little children”? The emphasis on child-citizens and their schooling highlighted the Klan’s concerns about the absence of the Bible in schools and about the parochial school. Education inculcated nationalism, and the removal of the sacred text and the movement of students into parochial schools suggested that the Klan’s preferred form of nationalism might be undercut or, more dramatically, attacked.

Education, in addition to patriotic leanings, was to provide moral teachings, in particular “the revealed will of the Bible,” because a biblical focus would “make good citizens and will best promote the interests of the institutions under which they live and for which they are responsible hereafter.”50 For the Klan, the Bible, then, was not just central to public education; it was a necessity. Children could not fully become (Protestant) American citizens without biblical instruction.51 The Klan’s concern over the Bible in the public school arose over what the order perceived as threats to common schooling. Some wanted to remove the Bible from the curriculum, while others removed their children from the public school in favor of “sectarian” education. In an article titled “Patriotism” the author tackled the issue of the Bible in the public schools as a part of his system of nationalism. He wrote, “If we would keep this land of the free we must extend Christian principles. Let us keep the Bible in schools.”52 A Kourier contributor, a self-proclaimed former educator, explained why the Bible was so important. The Bible was “holy inspiration of the word of God to man as a guide . . . so regarded by all denominations of Christians.” However, creeds and dogmas, according to the author, should be left out of the schools and instead taught in the home. For the “retired teacher,” biblical instruction made good moral citizens dedicated to American institutions. He could not fathom why “one denomination alone objects to the reading of the Bible in the public schools” and how that objection caused the removal of the sacred text in many instances. The retired teacher wanted the text returned to the schools, so children would “become acquainted with their relations and obligations to the Creator.” Additionally, he derided critics by noting that the Bible was not a “sectarian book,” but rather that men placed sectarian theories upon it. The Bible was the center of the Christian faith, and the teacher did not see why Bible reading in schools would cause controversy. The contributor either lacked knowledge of the Douay-Rheims Bible, the Catholic Bible, or he did not consider anything other than the King James Bible to be a Bible per se. For opponents, it was a sectarian text—more specifically, a Protestant text. For the teacher and the Klan, the Bible was “the foundation upon which civilization itself and National liberty are based; it is more. It is the only guide that man has to lead him upward to God. Without it the future is all darkness and the present all gloom. It is the ray of light emanating from the throne of God that illuminates the destiny of man beyond the grave.”53

This sacred text was a necessity for education because civilization and national liberty were at stake with its removal. The character of nation would be changed not for the better but to reflect the concerns of one denomination, Catholicism. The Klan did not acknowledge the concern that a generalized Protestantism might indoctrinate Catholic children. The nation had caved to sectarian interests instead of uplifting the nation’s heritage and the lineage of the common school. Moreover, the foundation of religion and nationalism civilized children. Because of the emphasis on education as civilizing, Imperial Wizard Evans noted that the public school could provide an aid to the lawlessness that he believed was overrunning the country. Evans lamented that the public schools no longer followed the approach of Horace Mann, a prominent educational theorist. Mann, “the immortal sponsor and patron saint of education in America, believed that national safety, prosperity and happiness could all be attained through free public schools, open to all, good enough for all and attended by all.” If public education had followed Mann’s direction, Evans believed that the nation would be free of anarchy and crime. The schools in their longevity had become somehow inadequate. The Imperial Wizard voiced his concerns that the schools “have not the institutional standing to which they are entitled; they do not prevent illiteracy, not always promote patriotism; too often they teach a divided allegiance.”54 The schools had been corrupted, and the removal of the Bible was only a piece of the puzzle. The Klan’s enemies surrounded the sacred institution.

J. S. Fleming, a Klan author, reported, “Our enemies would bar Jesus Christ and His Bible from our public schools, in order that we may forget them and thus enable aliens to cunningly substitute the pope and his creed as our God and Guide.” Without the Bible as guidance, Fleming was afraid that immigrants might be able to subvert “traditional” American culture by focusing on the pope and Roman Catholicism. Fleming conveyed the magnitude of Bible reading as part of common education, as did the contributors to the Kourier. He contended that the biggest threat to education was Roman Catholicism. Fleming wrote, “Subjects of the Roman Catholic government cannot avail themselves the benefits of our American public schools on account of the contaminating influence of religious heresy over their children.” In Fleming’s opinion, Catholic worldview contaminated children, and the public school might not prove effective for them. Like Evans had maintained, those children faced a “divided allegiance.” Catholic students would not have the experience of public education because they were enrolled in parochial schools operated by the church. The parochial school was particularly offensive to Fleming because Catholic religious tenets were taught there, and the Bible was supposedly missing “because it is dangerous to the moral and religious welfare of the children of its subjects.” Fleming did not acknowledge that the Catholics used their own Bible, the Douay-Rheims, which shows at best a lack of understanding about Catholic worship and practice. The crux of the issue for the author was that Catholic parochial schools, which taught Catholicism, were receiving some funding from the government. Fleming lamented that the government “cannot yet legally force loyal Americans to pay for the training of children into a religious hatred of everything American.”55 The Klan envisioned the parochial school as a vehicle that might destroy national character because Catholic children were not being taught the correct form of American citizenship.

For the order, the parochial school was an affront on American culture. For one missionary, the Roman Catholic Church was replacing the necessary state education with Catholic forms of education. The missionary argued, “Evidently Rome believes that there is a radical difference between Catholic education and that given by the civil government, else her leaders would not be so bitterly opposed to the public schools.” What most concerned the writer was the “obvious” plot by Catholics to put American children in parochial schools and then to take over the educational system as a whole. Catholics obeyed the pope, and their priests “[forbade] their members to send their children to our schools,” as well as threatened “them with hell-fire” if parishioners sent their children to public schools.56 The writer envisioned Catholics as oppositional to the ideals of democratic government and questioned their ability to maintain parochial schools. Sectarian schooling was unnecessary since state schools were created with the explicit purpose of educating the nation’s children and youth. Parochial schools supposedly taught papal infallibility, ecclesiastical law over civil law, “inferior” moral codes, and limited subject matter.

The missionary warned, “We have only to wait until they have duly trained five or ten millions of their youth to find ourselves worm-eaten with a close-knit constituency pleaded to a system of politics which is entirely subversive of our liberties.” In the order’s thinking, the parochial schools were breeding grounds for un-American ideas and foreign allegiances, and those schools created youth and children versed in an alien religious system. The Catholic Church and its schools were, then, a direct menace to the Klan’s America. The “Romish education” robbed the government’s right to educate children and taught “immorality and anti-democratic doctrine.” Moreover, Catholic teachers could not be trusted in the public schools because of their allegiance to their church. The missionary ended his article by affirming that “no Protestant Church holds or teaches such anti-democratic and iniquitous doctrines.”57 What becomes clear is that the missionary, like many other contributors to Klan newspapers, believed that Catholicism was an inherent threat to the nation. Catholics did not use the same Bibles as Protestants, and they often educated their children in parochial schools rather than the public schools. Their children, thus, were pedagogically dissimilar to Protestant American children, and future generations of citizens would not be trained on how to be citizens by the common school. How could Catholics and their children be trusted? They did not absorb the mandated patriotism of the public schools, nor were they aware of whom the “forefathers” were. Catholic opposition to common schooling was coded as an enemy’s attack on sacred liberties. For the Klan, those Catholics preferred not only the degradation of public education but also the destruction of national foundations.58

Despite the Klan’s attempts to present the parochial school as opposed to citizenship and real Americanism, Catholics envisioned the parochial school as “a solid bulwark of good citizenship.” Writing in Our Sunday Visitor, T. L. Bouscaren presented the Catholic concern with the public schools in similar terms to the order. For Bouscaren, the problem with common schooling was that it excluded religious instruction because those schools were open to all citizens. Since a variety of students from diverse religious backgrounds attended school together, teachers could not force a particular religious belief on them. He wrote: “Americans have always been, and are still a religious people. Even in the public schools, many of the most prominent teachers and directors have been either ministers of religion or at least sincere and earnest Christians. They would be shocked at the idea of regarding religion of Christ as something un-American.”

For the Jesuit, religion was not antithetical to Americanism but rather a crucial part of nationalism. The problem was in the public schools’ attempts to be nonsectarian. Excluding religion proved detrimental for students and the nation. That absence of religion was why Catholics preferred parochial schools for their children—they guaranteed that their children would receive needed religious instruction. Bouscaren noted, “The public schools would be better and truly American if they included much-needed religious instruction.”59 American citizenship still needed religion from a Catholic perspective, and the public schools were sorely lacking. In spite of the similar concerns about the absence of religious instruction, the Klan did not see the parochial schools as beneficial for the nation. In addition, the order believed Protestantism to be the only religious tradition bound to patriotism. Bouscaren supported the place of religion in schools, but only if Catholic students learned about Catholicism and other students learned about their own faith traditions. For the Klan, that was not a viable plan because students then would not have access to the white Protestant version of American history. In Oregon, Klansmen mobilized around the issue of compulsory public education to combat the influence of the parochial school. In 1922 the Oregon Klans supported a statewide initiative that required attendance at state schools.60 The hope was to diminish the impact of the parochial school and bolster the beloved public school. Americanism was defined in general Protestant terms, and the school proved to be the battlefield not just for local communities but also for the larger nation.

The spirit of Americanism and the spirit of Protestantism are one and the same.

For the Klan, “The spirit of Americanism and the spirit of Protestantism” were not just similar but “one and the same.”61 To protect America required a defense of Protestantism against all those reprehensible forces that would weaken or denounce the faith. The Klan’s attack on immigration, its religious intolerance of Catholics and Jews, and its campaign to keep the Bible in the public schools emerged because of concerns about the relationship between faith and nation. Immigration introduced millions of non-Protestants into American culture, and the Klan feared that those immigrants might not assimilate to the Klan’s version of American culture. Evolution was blasphemy in the face of God, and the Bible belonged in the schools because good citizens needed to experience God as part of their patriotism. Many of the Klan’s “enemies” of Americanism were supposed enemies of the predominantly Protestant culture of 1920s America. Protestantism was an essential facet of the Klan as a movement, and it shaped the order’s approach to the nation and the many different peoples within it. American culture was changing, and the Klan wanted to save its vision of the only America, white and Protestant. For Imperial Wizard Simmons, “The cross of Christ must be exalted and sustained, or our splendid civilization might be doomed.”62 America’s fate was intimately wed to the place of Protestantism in the nation. For Imperial Wizard Evans, the only choice to protect America was for Klansmen to step forward, proclaim their religion, and protect their nation. The Klan was needed to “sound continuously its certain Protestant note in this Protestant country.” Evans wrote: “The Klansmen of the nation, unafraid and undeterred, strong in their faith in God, cherishing an open Bible, loyal to the Klansman’s Christ, firmly believing in the principles taught by Him, rejecting all traditions and opinions of men contrary to His teachings, will continue to contend to establish these principles in Protestant America.”63

Exclusion and homogeneity defined both faith and nation. The Klan’s virtues and theologies hinted at the more nefarious side of the organization. The order hoped to be the savior of the nation, “a civic Messiah” to lead Protestant Americans in their reclamation of America.64 To save the nation, the Klan defined the nature of true Americanism, in opposition to all groups who were not white and Protestant, and retold American history with a selective sampling. It also fought fiercely to keep the Bible in schools. To protect the nation, the order felt it must keep the country Christian in the face of foreign as well as domestic threats. The Klan envisioned members as Christian knights defending faith, nation, womanhood, and the race in the battle against all of its enemies. They strove to preserve the white Protestant nation and the order’s enduring vision at all costs, but masculinity and manliness could not solve the problem confronting the second order. The challenge to the Klan’s vision was already in place, and encroaching diversity of religion and race made its white Protestant America tenuous at best.