CHAPTER 4 |

“The Sacredness of Motherhood”: |

We women believe that the Klan is to America what a loyal wife and mother is to the home. Her work is in a sense invisible to the eyes of the world. Yet she is ever on the lookout and ready to meet this need and to care for that one. She is the spirit of protections, of love, of idealism, of discipline and of life itself in the home.

—ROBBIE GILL COMER (1925)1

We believe that under God, the Women of the Ku Klux Klan is a militant body of American free-women by whom these principles shall be maintained, our racial purity preserved, our homes and children protected, our happiness insured, and the prosperity of our community, our state and our nation guaranteed against usurpation, disloyalty, and selfish exploitation.

—IMPERIAL NIGHT-HAWK (1924)2

In Thomas Dixon’s Clansman (1905), for Southern whites as well as African American enfranchisement causes the birth of the Ku Klux Klan. The pivotal plots of the novel focus on the danger that African American men, now in positions of power, pose to vulnerable, white women. Dixon creates many female characters, but two, Elsie, the plain and kind Northerner, and Marion, the “shy elusive beauty,” are essential to the action of the novel.3 While playing her banjo in a veteran’s hospital, Elsie encounters Ben Cameron, the Confederate hero. Moved by his mother’s desperation to save her son, Elsie secures a presidential pardon for the handsome Ben and promptly falls in love with him. However, her father disapproves of Ben’s Confederate background, and their romance is thwarted throughout Dixon’s tale with increasingly sappy prose. Dixon describes her with “warm amber eyes” and “fair skin with its gorgeous rose-tints of the North paled.”4 The tale documents not only the Klan’s rise to prominence but also Elsie and Ben’s growing love for one another, her eventual embrace of Southern culture, her growing disdain for African Americans, and Ben’s interpretation of Reconstruction.

Marion, on the other hand, is Southern by birthright, and her beauty and gentle nature enchant even Elsie’s cantankerous father. On her outings with her horse, “every boy lifted his hat as to passing royalty, and no one, old or young, could allow her to pass without admiration,” because she “had developed into the full tropic splendor of Southern girlhood.”5 Blonde and fair, dainty and graceful, Marion is the example of a Southern woman. She is the epitome of white womanhood metamorphosed into the tragic symbol of Southern loss in Reconstruction. When Gus, an African American, rapes her, Dixon alludes to the loss of not only a white woman’s purity but also the white men’s power. The rape demonstrates that white men are no longer able to protect the honor of their women in the face of African American “brutes.” Because of their dedication to racial purity and her reputation, Marion and her mother react with horror to the rape and lament the loss of innocence. They decide that suicide is a far better option than allowing anyone to find out about the terrible act. The mother and young daughter throw themselves off Lover’s Leap. When their broken bodies are discovered, Ben and others recognize the brutal attack on Marion.

Several white men, including Ben, seek to avenge Marion’s demise and to take back control of their region. They gather together as a clan in white robes and helmets to protest the ruin of white womanhood and their imperiled South. During their first gathering, one member utters, “Brethren, I hold in my hand the water of your river bearing the red stain of life of a Southern woman, a priceless sacrifice on the altar of outraged civilization.”6 The loss of Marion’s virginity and her death haunt Ben, and he is convinced that the Klan has to combat “dangerous” African Americans. Vulnerable and in need of constant protection, Elsie and Marion represent white womanhood at its finest—exemplifying virtue, loyalty, and love—and both women impact Ben in his journey to save the South. The defense of white womanhood was a banner for the first Ku Klux Klan in the 1860s and 1870s, and the concern over the fragility of white women resonated in the 1920s Klan. However, the characterization of women changed with the second order.

In George Alfred Brown’s Harold the Klansman (1923), a novel about the 1920s Klan, Ruth Babcock is not only the central female character but also the heroine. Ruth has a career as a stenographer, and she works very hard to support her aunt and her father, who has been injured in a car accident. In the early pages of the novel, the author traces her lineage through her mother’s family, who is of Confederate stock. Like Dixon’s female characters, Brown’s Ruth is also attached to the South, which informs her decisions throughout the novel. In addition to her career and domestic duties, Ruth is also the love interest of Harold King, an architect and the Klansman for whom the novel is titled. The novel is an elucidation of Klan principles through fiction to provide “entertainment” as well as “a greater appreciation of the Invisible Empire.”7 To accomplish his goal, Brown uses discussions between Ruth and Harold, as well as Ruth and other characters, to flesh out Klan principles. Ruth, “a girl with a kindly heart and plenty of grit,” eventually falls in love with Harold and embraces the order.8 However, she struggles greatly as she slowly becomes aware that Harold and the Klan are the man and the order she supports. She is a woman of honor and modesty, and Harold’s admiration for the heroine grows page by page. He, of course, is the exemplar of manhood: hardworking, kind, courageous, and dedicated to his order. The plot also follows the opposition he encounters as a Klansman from the larger business establishment, which is under the control of Roman Catholics and Jews.

Interestingly, Ruth proves to be a more developed character than either Elsie or Marion because she has more agency. In a pivotal moment in the novel, she terrorizes an African American janitor at the bank, where she works, by donning a robe and a mask. Rastus, the janitor, is significantly behind in his tithing, and Ruth uses her costume to terrify him back into financially supporting his church and pastor. Rastus’s pastor is supportive of the Klan, and Ruth believes the janitor needs a little encouragement in the form of terror to back the white-robed order. Unfortunately, her bold action brings negative press upon the Klan, who, Brown reminds readers, never committed such dastardly acts. The heroine eventually confesses her actions in an affidavit to a local newspaper to guarantee that the press did not malign the order, which marks Ruth’s transformation into a proponent of the Klan. When her other suitor, Chester Golter, who is also the nephew of Ruth’s prosperous boss, Stover, impugns the Klan, she quickly defends it: “I believe in the principles of the Klan; I believe that a good class of men belong; that they are doing many charitable acts, and in many places have created more respect for law and order. If I were a man I would join this order of real red-blooded Americans.”9

Her support of the Klan displeases Golter, who opposes the fraternity and Ruth’s newfound admiration for the Knights. More important, her desire to join the order, if she were a man, reveals her commitment to the fraternity and its politics. That commitment emerges again when her friendship with Harold imperils her job. Stover demands that Ruth end the friendship, but she refuses. Despite Stover’s threats and later cajoling, Ruth quits. In that moment, Brown describes her as “a type of noble womanhood,” determined, daring, and loyal. The heroine’s actions enchant the author and hopefully his readers.

However, Ruth is not a complete agent in her literary destiny. Harold saves the floundering heroine by finding her a new job and uncovering that Stover stole her father’s fortunes. The novel ends with Stover’s arrest and Ruth’s marriage to Harold in a nearby town. On the way back to their hometown of Wilford Springs, they spot a fiery cross in the landscape, which signals the sanctity of their marriage. Unlike Elsie or Marion, Ruth surfaces as a strong female character but still requires a Klansman’s protection. She works to take care of her family, upholds her principles, and finds comfort in marriage to her protector. Harold, of course, rescues her and restores her father’s dignity (and wealth), but Ruth proves responsible for her actions. The plucky heroine might require defense, but she also has agency, which Dixon refuses to provide to Elsie and Marion. Ruth signifies the paradox for the Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK): women claimed their agency but also negotiated the gendered expectations and constraints from their male brethren about the required roles of women in American life.

In the 1920s Klan, defense of white womanhood was a slogan for members. Yet with the advent of the WKKK in 1923, women were crusaders for the order as well as supporters of their husbands, brothers, fathers, and sons who were members. For Klansmen, Klanswomen were to be virtuous white women in need of defense and protection, but those women strove to define their service in their own terms. They used their roles as wives and mothers to articulate their entrance into the order while men sought to circumscribe their roles. Motherhood was a primary feature of a woman’s role, along with undying support of Klansmen. Yet Klanswomen had their own notions about the role of women within the order and in the larger American society. They called for political equality for white women, echoing the Klan’s concerns over the sanctity of the home and the virtue of white womanhood.

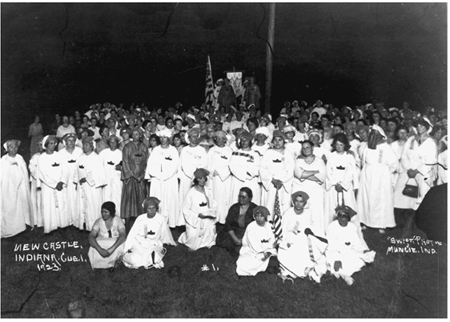

Women of the KKK, New Castle, Indiana, 1923. Photograph by W. A. Swift. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

To articulate their positions on gender, the WKKK relied on Protestantism and nationalism to showcase the important role women played in domestic and public spheres. While the men’s order limited the place of women to wives, and most significantly mothers, the Klans women attempted to prove that motherhood made them more apt than their male counterparts to protect the nation the Klan held dear. The WKKK were “conservative maternalists” who deployed the Klan’s expectations about motherhood and womanhood to their advantage. Drawing upon beliefs about inherent differences between the sexes and women’s special role in producing young citizens, the WKKK, like other conservative women of the 1920s, manipulated their gender role to help promote the Klan’s political aspirations but also to critique the men’s order.10 Both Klansmen and Klanswomen uplifted the home as a sacred altar that stoked the fires of religiosity and patriotism, and this emphasis on the special status of the home and domesticity furthered the order’s preoccupation with women and marriage. The Klan supported lecturers, who were supposed ex-nuns, ex-priests, and ex-Catholics, to demonstrate the pressing danger of Catholics toward young women in both the confessional and the convent. The 1920s Klan, then, perceived a pressing Catholic threat to the bonds of Protestant marriage because of the reinterpretations of legitimate marriage by the church’s hierarchy. This threat signaled that Catholics, once again, were dangerous to nationhood and faith, and that the danger was most significant for white Protestant women, who were the supposed targets of the church’s convents, priests, and marriage reforms.

Women of the KKK in regalia. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

American women are the uncrowned partners of American men.11

For W. C. Wright, a Klan minister, the first Klan came into existence because of the “negro domination” of the South. His narrative echoed Dixon’s portrayal of Reconstruction, and he argued the “Klan saved the South from negro domination, protected the chastity of Southern womanhood from black brutes in human form.”12 The 1920s Klan was partially a memorial to celebrate the achievements of those original Klansmen, especially their desire to defend chaste white women. The second revival of the order sought “to promote good morals,” which required the protection of “the chastity of womanhood, the virtue of girlhood, and the sanctity of the home.”13 This morality was bound to womanhood. The defense of white women was essential for the order as well as for its predecessor, and the 1920s Klansmen lamented the degradation of white womanhood that they found in popular culture and society at large. The 1920s, after all, was the era of the flapper as well as the establishment of women’s right to vote (1919), which provided women with political power in the form of the ballot.14

Historian Nancy MacLean noted that Athens Klansmen wrung their hands over the behavior of young women, their treatment by the men in their lives, and their need of protection because of female fragility and vulnerability. MacLean pointed to the Athens press as the cause of such anxiety, because the newspapers documented the prevalence of unwed mothers, deserted wives, the abuse of women by husbands and fathers, and, most disturbingly, defiant young women who did not heed the warnings of their mothers or fathers.15 These women were in dire need of protection not only from societal ills but also from themselves. Thus, Klan newspapers, speeches, and other print asserted the proper characteristics and roles for women to correct those documented ills. The Klan’s reading community became versed in the proper places for women in American society and acknowledged the order’s crucial role in preserving those places and spaces.

In the Kluxer, a Klan weekly from Dayton, Ohio, the pseudonymous C.B. reflected on the essential nature of women, who possessed the “most wonderful kind of heart created.” For C.B., humans first had to acknowledge that our hearts were “inclined to do evil,” but by following the path of Jesus, one could have a change of heart. Once members realized that truth, then they could not disagree that the hearts of women might possibly be divine. Women were the more spiritual yet delicate creatures. C.B. continued:

Do you realize women, that on our every side, to the North of us, to the South, to the East and to the West of us are precious young ladies with hearts as pure as gold, and with a conscience as tender as a baby’s, which are about to blossom forth with all the splendor, and the beauty of the purest lily growing. O God, how can I say it—it grieves my heart to know it is so, but here in America, a nation of Christian people, these precious young lives are taken in beauty and innocence with no regard for their feminine timidity, with no respect for their sense of shame, and in a cruel and pitiless manner, their lives are wrecked forever.16

Women had hearts “as pure as gold,” infantile consciences, and beauty. For C.B., the fairer sex was essentially childlike and in need of defense. Men deserted, abused, and maligned these pure and vulnerable women, so women lacked the care they rightly deserved. C.B. was astounded that in “Christian America” the cruel treatment of women existed with no attention to their “timidity” and gentle qualities. Heartbreak, cruelty, prostitution, and suffering “wrecked” young women. C.B. lamented the burgeoning “white-slave traffic,” which created despairing and piteous women. Only “white-robed figures” could protect the white woman with “girlish figure and innocent eyes.” The Klan was the only organization that could remedy the poor state of womanhood. The author purported that the “God-inspired army” of the Klan could guarantee that the “Heart of Woman” would never suffer again. C.B. urged the men of the Klan to be a part of that campaign, and he also encouraged the WKKK and ordinary young women to take a stand against such travesty. The author pleaded with American women to take up the “banner of purity” to assure “fair young creatures have their liberty too.” Those women should offer prayers to ensure the safety of all women in the supposed Christian nation. C.B. proclaimed, “Let us push forward and clean things up, for the protection of pure womanhood in America.”17

Such protection was crucial not just because women were delicate creatures in peril but also because women were a valuable resource for nation and order: 100 percent American women were needed just as much as 100 percent American men. C.B., however, painted a disturbing portrait of fragile, timid women confronted by danger lurking around every corner and the inability to provide protection for themselves. The men of the Klan had to supply much-needed defense for white women.

In spite of women’s “inherent” fragility, the order lauded women who embraced the traditional roles of wives and mothers and maintained the home. In “A Tribute and Challenge to American Women,” the Grand Dragon of Arkansas observed “the word ‘Woman’ always arrests the attention of every true man at once.”18 That was not because of the sexual attraction of women. Rather the Klan leader professed that no man could forget his loving and wonderful mother. Mothers, sisters, wives, and daughters were all noble beings who supported and fostered their men. Yet their nobility was often ignored, and women were treated as lesser than men. For the Grand Dragon, women throughout history had faced prejudice, ignorance, and superstition until Jesus “discovered” woman and started “her on the upward road.” The presence of Christ undercut that ignorance. Christianity served to advance women in society, and despite the Catholic attachment to Mary, the author argued that the “mother of our Lord” should be reevaluated, even if America sought to expunge Catholic ideology from its history.19 Jesus called upon women in his ministry and demonstrated that they had the ability to impact their individual societies and the larger world.

The Grand Dragon continued that the American woman shaped the “destiny of America” as much as the American man because she reared children. Women were more than “help-meets”; they were “helpmates” who helped build homes, churches, and schools.20 American women were the “uncrowned partners of American men.” For the Klan leader, they could no longer be limited to the domestic sphere. More important, with the right to vote women could support the Klan ideals and principles through the ballot box, a mandate that provided women with a voice in the nation’s development. The Grand Dragon remarked that his “tribute” to women came from his “tenderest recollections of a mother’s solicitude” and the “constant inspiration of a wife’s undying affections.”21 Women fostered him, and he believed that the Klan should encourage women to participate in the political process to repay their kindness. Additionally, he challenged women to stand beside “one hundred percent American men in their stride to restate, and reinstate, great American principles in this, our God-given Country.”22 Men needed to protect women, but their female counter parts were to be partners in the Klan’s endeavor to bolster Christian America. Women had the ability to help reclaim the American nation.

The sacred remembrance of their glorious mothers.

Despite the equality offered by the Grand Dragon of Arkansas, the Klan, overall, glorified women as mothers rather than as political participants. In a letter to the Exalted Cyclops and Kligrapps in Indiana, a Klan official reminded fellow officers of Mother’s Day, “the sacred remembrance of their glorious mothers.” The director of the Department of Propagation wrote, “When God opened the gates of heaven and gave to all the world mother, it was his greatest blessing to all humanity outside of Jesus Christ.”23 Mothers were a blessing who were only surpassed by Jesus in their significance, which clearly demonstrated the magnitude of ideal motherhood for Klansmen. Motherhood equaled love and support, and, more important, motherhood was God’s gift to humanity. The director continued:

She knows how to kiss away the sorrow of the heart, her hand knows just when and how to stroke a weary brow. Her sweet, soft voice gives the loving word of counsel and sympathy needed but—oh, how we miss her when she is gone. She has waded into the jaws of her death for her offspring and is willing to lay down her life again if need be that their lives might be spared. She has spent the long weary night in taking care of the babes, watching over them during their growing school days, planning the meals, mending the clothes, bandaging the hurts, following them closely up to young manhood and young womanhood, and then she gives them to some one else to have and to hold. that’s a mother’s love.24

For the director, mothers were counselors, sympathizers, and supporters who guided their children from “babes” to adulthood. They gave up sleep and time for their children, and likely those adoring women would hand over their own lives for the lives of their children. A mother’s love was defined by self-sacrifice because women raised their children only to lose them to the adult child’s husband or wife. The director encouraged Klansmen to reflect on their own mothers and to write notes that echoed the love that they had received. Contemplating a mother’s example “shall do much to strengthen the morale of our Klaverns.”25

New Jersey Klansmen celebrated Mother’s Day in an Ocean Grove auditorium. The event, which the Christian Century called a “bed sheet revival,” began with a Kleagle’s speech on the “sacredness of motherhood, the services of the [K]lan in the protection of motherhood, and the despicableness of the persons—presumably not white Protestant gentiles—who do not love their mothers as they should.” The main speaker, however, was a “lady kleagle,” who was excited to speak to young women in the audience. Those young women were the “mothers of tomorrow.”26 She also reiterated the Indiana director’s vision of motherhood by asserting that mothers were the second gift from God (because Jesus was the first). She even suggested that she would rather “hold the office of motherhood than be a President of the United States of America.”27 All her positive attributes, she claimed, came from her very own mother.

The Kleagle’s mother, by inculcating Klan principles in the life of her daughter, served to further the order. The Klan idealized motherhood and uplifted the primary role of women as mothers for that very reason. Women had the power and influence to raise their children by Klan principles. They taught their boys and girls a love for religion, nation, and the order—the mother’s primary and most imperative role. This power over one’s children, however, also gave the men’s order pause. If women could produce better white Protestant citizens, then they also had the ability to create lackluster and problematic citizens too.

The Kluxer warned that a mother’s influence could prove dangerous to her children. In a morality story for its readers, the publication confirmed the unspoken dangers of motherhood. A young man with “the Ku Klux germ,” which grew into a burgeoning sense of Americanism, almost neglected the Klan because his mother did not want him to join the fraternity. The young man was “manly” and “a native born Protestant” who admired the order and its “wonderful” reputation. Yet he feared that he was a “slacker” for both his country and Christianity. His mother, however, was against his membership. The Kluxer reported that she was a nervous creature, and “when that young man told his mother that he intended to join an organization and that he would be away at meetings at night, it nearly killed her.” His mother did not deny the efficacy of the order. Instead, she wanted to hold on to her son a bit longer. She, unlike the ideal mother, was not prepared to sacrifice herself for the betterment of her son. The young man joined the order against her wishes. Like “the heroes of fiction . . . are willing to sacrifice their loved ones for the common good,” that young man decided to fight for Americanism.28 Through his noble example, his mother forgave him, and she eventually embraced the order that her son loved. Her son’s commitment changed the heart and mind of his mother. Mothers, then, wielded much influence, good or ill, over the lives of their children.

In “American Mother’s Prayer,” published in the Imperial Night-Hawk, Mrs. P. B. Whaley emphasized her crucial role as a mother to her son. She instilled a love of nation, religious faith, bravery, and manhood. She prayed to God to make sure that her son would become a Klansman because that was her utmost duty as an “American mother.” Mrs. Whaley, unlike the mother from the Kluxer, understood what was expected of her in the maternal role. Whaley was the example, and the unnamed mother was the exception. The Klan portrayed the exemplar mother motivated by self-sacrifice in the face of her children’s needs. Mrs. Whaley’s submitted poem emphasized how women desired to guarantee that their children, especially their sons, turned into “real” American citizens. The wishes of the unnamed mother, the most pressing of which was to keep her son at home, were cast aside in the face of her child’s needs and her responsibility to raise white Protestant citizens.

Mothers were supposed to be supporters, but they were not sustained in their own wishes and desires. The Klan’s vision of motherhood revolved around the female figure, who sustained the order and fostered her children regardless of her own interests. She was deserving of Mother’s Day praise while the order cautioned less devoted mothers about their harmful behaviors. The expectations the Klan placed on motherhood were unattainable. Relationships with one’s children defined the archetype of maternity, but the model woman had her own desires and wants relegated behind her maternal duties. For the Klan’s textual community and its vision of nation, women became mothers only, but the order expressed its deep concern over the power women could wield when they ignored the Klan’s larger ideals and goals. The relegation of women to maternity and domesticity occurred because of the mother’s relationship with the sacred home. Mothers helped create, maintain, and preserve the home, the order’s foundation of faith and nation. Mothers, much like masculine Knights, inhabited a tightly inscribed role, and the Klan tried valiantly to keep women within it by emphasizing the significance of the home to its vision of America.

God’s greatest earthly institution . . . the anteroom to the Mansion in the Skies.

Regard for the home appeared in domestic klannishness, a term employed by the first Imperial Wizard, William J. Simmons. Domestic klannishness was one of the “four-fold” applications of the order, and the main goal was the protection of the “sanctity of the home” by Klansmen.29 The Klan warned members of the danger posed to the sacred institution, which served as the building block for both religious faith and nation. For Imperial Wizard H. W. Evans, the fate of the national government rested in the “quality” of the American home. The Imperial Wizard argued that the home was “the highest and soundest expression of both personal and public welfare.” The strength of its homes supported America, and the failed countries were those “whose citizenship worshipped not at the fireside.”30 The nation, for Evans, was like a home that previous Americans built and current citizens protected. A citizen’s personal home directly impacted the national home. And families were equally as important. The love of individuals for their homes and families produced love of nation. Familial love transformed into national love. According to Evans, the defense of the home and family life was a necessity because the home was the arena where future citizens learned patriotism.

Texan judge Felix D. Robertson outlined the duties of citizenship in a public speech reprinted in the Night-Hawk. He saw the home as pivotal to the formation of better citizens. Robertson argued that America should actively put God in history and trace the presence of God through momentous events, from Mount Sinai to the Civil War. The way to guarantee recognition of God’s presence in American history, he believed, was to emphasize the matters in the “American home.” Robertson called the home “God’s greatest earthly institution . . . the anteroom to the Mansion in the Skies.” The home represented the path to salvation for individuals and the nation. Robertson suggested each home should contain an “old style Family Altar[,] that sacred place around which every American family ought to meet in humble supplication to the God of their Fathers twice each day.” The family altar served as a place of worship that would produce “that high and noble type of men who built our Government on its solid foundation of reverential faith.” The physical altar should contain the “starry banner” and the Bible, which were symbols for human liberty and God’s promise respectively. The altar functioned as a material artifact to show the family’s dedication to the Christian nation. Interestingly, Robertson focused primarily on the rearing of sons to become patriots. But he ignored the daughters as potential citizens despite the fact that the mother was responsible for both education and maintaining the altar. The critical feature for the betterment of the nation for Robertson was the family and the home, yet he neglected women in his plan to restore national consciousness of religion. To foster a religious and patriotic environment in the home would lead to better citizens and the restoration of a “Godly land.”31

The godly land, however, included female citizens who wanted to do their part for the nation and their families. Women hoped to participate in the Klan’s restoration, and the women’s order allowed them to become active participants. In their creed, the Women of the Klan affirmed the American home as the “foundation upon which rests secure the American Republic, the future of its institutions, and the liberty of its citizens.”32 The home, the domestic space over which women had such power, was essential for citizenship, and the WKKK did not take that role lightly. They, unlike Robertson, recognized the power of women to foster the order’s vision. They saw themselves as soldiers for the cause, much as Klansmen were, and they articulated their position in both religious and patriotic terms.

We believe in the mission of emancipated womanhood.33

In 1923 the Klan established the Women of the Ku Klux Klan as an order. The national officers adopted a creed similar to the men’s order, but it contained key differences. Both the men’s and women’s creeds emphasized Christianity, the separation of church and state, public schools, racial purity, freedom of speech, freedom for the press, freedom of worship, the Constitution, and the protest of foreign influence in American government. The women’s creed also emphasized political and social equality for men and women, as well as a call for “emancipated womanhood freed from the shackles of old-world traditions and standing unafraid in the full effulgence of equality and enlightenment.”34 Not surprisingly, the Klan did not focus upon rights for women but did appreciate the potential power of white women as voters. The WKKK stressed that both men and women had built the nation together, and so they could restore it together. They advocated their role in protecting and fostering national culture, and they endeavored to be active participants. Like their male counterparts, they focused on benevolence as well. Klanswomen in Alabama founded a Protestant orphanage named Klanhaven, which connected children with Christian families.35 The founder was an exemplary Klanswoman known for her religious faith as well as her mothering skills. The orphanage was just one example of the power of Klanswomen and their organizing ability. More important, such a benevolent action signaled that the WKKK claimed leadership ability from the members’ power to nurture.

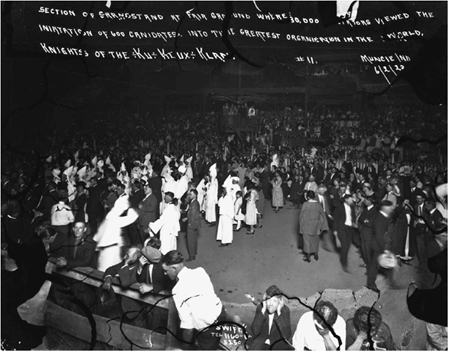

Klansmen and Camelias on parade, 1923. Three thousand Klansmen and Klanswomen paraded with 60,000 onlookers. Photograph by W. A. Swift. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

Klanswomen attend a funeral in full regalia. The deceased’s uniform rests on the coffin. Photograph by W. A. Swift. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

The WKKK was “organized by women for women” with the aid of the Knights of the Klan. Previously, women could only help the men rather than have their own order.36 The WKKK was headquartered in Little Rock, Arkansas, under the command of Lula A. Markwell, the Imperial Commander, and Robbie Gill (later Comer), the Imperial Kligrapp (who eventually became the Imperial Commander after Markwell). The WKKK was an order of “white, Gentile, Protestant native-born women of America, imbued with the high ideals of patriotism and love of home, school and country, [who] recognize in the new order the agency wherewith they may make secure the emancipation for which they have been struggling from the beginning of time, and which the last few years have actually began to realize.”37

Klanswomen imagined their order not only as a mechanism to fight for their country but also as a vehicle for women’s rights. In Kathleen Blee’s Women of the Klan, she provided a much-needed monograph on the role of women in the WKKK, as well as how the men’s order envisaged the women’s auxiliary. Blee examined the tension between the men’s and women’s orders as well as how the Klan understood the home and women differently from the WKKK. She wrote, “The W.K.K.K dissented from the idealized view of home and family that was such a powerful symbol in the men’s Klan. Instead, Klanswomen described the home as a place of labor for women.”38 She found that the WKKK called for political equality as well as social equality. Yet she downplayed the religious emphasis of that order. Blee focused on their drive for women’s right to vote and defense of said right while ignoring the resonance between the men’s and women’s orders on the place of Protestantism in women’s equality.

Rather than rehearse the support of women’s suffrage, I choose to explore how the WKKK and their commander, Robbie Gill Comer, understood the role of religion in women’s equality. Blee wrote that the WKKK “appropriated the Christian emphasis of the Klan and used it to support an agenda of women’s rights.”39 Rather than examining the purported Protestantism of the women’s order, Blee, unfortunately, dismissed the faith as appropriation. The WKKK imbibed in the religious faith of the men’s order. Protestantism and nation defined the women of the Klan as much as it did the men.

God gave him woman to be his [Adam’s] comrade and counselor.40

In “American Woman” (1924), Robbie Gill explored the relation of her order to the men’s Klan and reflected upon the place of women in America. This speech, given at the Second Imperial Klonvokation in Kansas City, Missouri, proved to be very popular, and it was reprinted several times in the Klan press. Gill began her speech by admitting her hesitancy of speaking before Klansmen about the power of a woman. She admitted that the men might have already realized their “inability” to function “regardless of her [a woman’s] whims and annoying ways.” The Imperial Commander showed deference to the men in her audience, but she continued with her theme of female power. She traced the ability of women back to the Garden of Eden. God provided Adam with Eve as “his comrade and counselor,” and Adam was her “lord and husband.” Eve was the partner of Adam, but he was the head of household. Gill, however, centered upon Adam’s name for the “first” woman. Gill observed: “Gentlemen, that name he gave his wife on the morning of their nuptials is worth all the lectures on women ever written since. Adam . . . called her Eve, which in our language is Life. . . . Eve was intended to be not only the mere life of humanity, in its literal import, but the life and spirit of all true and genuine civilization.”41

God’s place, then, for Eve was represented in women, who were the lifeblood of society. Rather than emphasize men’s control over women, Gill explained how women were essential for both men and the larger culture. Not surprisingly, she ignored Eve’s participation in the exodus from Eden and instead relied upon the significance of Eve’s name. For the leader of WKKK, such action signaled that God never intended for women to be slaves to men. Women were to be equal participants in society, which she purported was the divine intention, although they had been treated poorly throughout history. For Gill, women had achieved their full freedom under the influence of Protestant Christianity. She argued that women were “better educated, more refined and more honored in Protestant countries than anywhere else—in Protestant countries, under free governments which are the fruits of Protestantism.” Gill lauded America, a (Protestant) Christian nation, as the country that most supported and recognized the rights of women.

Even the flag symbolized the national commitment to women. The red stripes signified the “manly blood” spilled for “women’s protection.” The white stripes represented both the purity of men and women. Each stripe “bears silent testimony” of the men, who would protect the “honor and chastity of our home-builders—our women.” Finally, the field of blue indicated both “loyalty and royalty,” which included loyalty to country and home, as well as Gill’s assessment that women in America were like royalty. Comparing American women to the “queens” in a deck of cards, Gill noted that they toiled (spades), disciplined husbands and children (clubs), and basked in their wealth (diamonds), but more important, all of these women were queens of hearts who loved.42 Their love fostered their husbands and children. Such love encouraged women to support their men because women’s power rested in men’s dependence upon them.

Eve might have been Adam’s helpmeet, but she had the ability to persuade him because of her support. Gill suggested that women yielded power over their husbands, and she reminded Klansmen of their dependence and need for their female counterparts. The Imperial Commander also acknowledged that men had provided women with an honored position as well as the ability to vote—a crucial step in the right direction. Gill assured her listeners that she would not continue to bore them with the virtues of women, and she congratulated her audience on their commitment to suffrage for women. Gill’s apology only rang partially true because she attempted to dismantle stereotypes that her audience, primarily men, had about their female companions. Her compliments to her audience masked her intent. Gill wanted to prove to the Klan that women would take suffrage seriously and that women actually had stronger political convictions than men. The conservative maternalism of the WKKK emerged in Gill’s speeches and convictions about the ability of women to reform American society.

These convictions emerged from the life stories of individual women who had experienced the detriment of alcohol, unlawfulness, and gambling because they had husbands who were drinkers, gamblers, or supporters of some other vice. Their families were at stake, and the power of the ballot gave women the voice to protect their families. The underlying message was that American women were victims to the men in their lives. With the ballot, women had the power to correct societal ills to make their own lives better, which meant they would not be subjected to the rule of detrimental husbands. Gill’s message was that those women would be involved in the political process, but what were the men doing? She affirmed that the WKKK supported the Klan’s program of Americanism and Protestantism, and she stated, “We believe with gripping conviction that a rediscovery of Jesus Christ . . . will be the only thing that will save our nation in these days of unrest and disturbance.”43

Yet Gill turned her attention to the men in her audience to point out that her membership had pressing questions about the men’s order. She wanted direct answers about its objectives, so that both Klans could demonstrate what they had accomplished for faith and nation. Interestingly, Gill compared the Klan to a “loyal wife” and mother, and she suggested that the Klan’s relationship to the nation was similar to the wife’s relation to the home. The maternal endeavor was not always visible, yet the mother handled the needs of the home. The Klan fulfilled the maternal role for the Invisible Empire. However, she still wondered whether the Klan was living up to the goals that the order cherished. Gill wanted objectives for action. She questioned, “Are we going to be Christlike in our relationships with all men, showing to the world just why Protestant Christianity is better for it than any other religions? Or, are we going to reveal the spirit of bitter intolerance in condemning the intolerance of others?”44

Gill interrogated the religious ethic of the Klan, and she affirmed the need to be “Christlike,” which she believed matched the true religious spirit of the Klan. Gill’s pointed questions revealed her frustration with the actions of the Klan, but she still deferred to the men’s authority by suggesting that Klansmen needed to provide a strong direction for both orders. In her speech, women, like Eve, were still helpmeets. She used her convictions to question their authority, but they did not give her the ability to rule the men’s order. The women wanted to put their God-given power behind the Klan, but they needed instructions to follow. Again, Gill emphasized the role of women to support. She asserted:

We women of America love you men of America. We believe in the things that are high and good and holy. Our homes will be kept as sanctuaries for you. . . . We will mother your children, share your sorrows, multiply your joys and assist you to prosper in the way of this world’s good. In return, we expect you to recognize our power for good over your lives, and in the nation. We expect you to be men of no ulterior motive, of no double-dealing, of no base conduct. . . . We pledge our power of motherhood to America. We can instill the spirit of our forefathers into the lives of our boys and girls. Our knees can be the altars of patriotism to them, and our homes the shrines of idealism where liberty can be fostered. The old saying that “the hand that rocks the cradle is the hand that rules the world” is true.45

Klanswomen offered their support, but Gill again hinted at the power of women over men. She also affirmed the power of those women to change the world. Such God-given power gave Klanswomen the ability to stand beside Klansmen in the fight for the nation. Moreover, Gill relied on Klan-sanctioned roles for women as mothers and wives to influence the development of the home and the nation. But her message was more radical because she alluded to the influence that women held over their children as transformative power over the larger world. White women were crucial for the implementation of the Klan’s vision of Protestant America, and Gill’s speech made such clear.

The Kourier continued to praise women for their attachment to the home. As in Gill’s speech, Klanswomen were important as home-builders and supporters for the Klan. The home, again, served as a foundation for nation, and a woman, “in all her purity and virtue,” made the home a sacred space. The monthly reflected not only on the connection of femininity with home but also the ability of women to engage the political realm. The Kourier noted that the amount of control women possessed over the domestic sphere might be applied to government and politics. The monthly argued that women had historically played an indirect role in government, motivating husbands and sons, until the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. “Woman gave to the world her greatest leaders, and is it at all out of place that she should now come to the front, proving her sex is fully capable of performing arduous and important duties?” Since the fairer sex gained the responsibility to pull their “share” in government, the Kourier affirmed the practicality of women in an age of radicalism. The hope was that white women would bring their abilities from the domestic sphere into the political realm. The “home builder” could become a nation builder.46 Not everyone was supportive of the new political power of women, and the Kourier reported that some denounced the ability of women to act in the political process.

In 1926 Robbie Gill Comer (who married) deflected criticism of her women, who were accused of not employing the ballot as many deemed they should. Comer had to explain the poor showing of women in electoral politics as well as to defend her own order.47 At the Third Biennial Klonvokation, Comer gave a speech that provided explanation. Comer focused on the mistreatment of women throughout history and argued that women faced a “handicap.” In her narration of women’s history, women started out as slaves to men, and later wives became “toys” to men, playthings who were at the whim of their male counterparts. As women began to assert their influence in the lives of their husbands and children, “Christian Europe,” with the emphasis on chivalry, allowed for women to advance forward. Chivalry placed women on “a pedestal of reverence and respect,” which Comer recognized as “unsatisfactory” for her female contemporaries. She remarked, “In the vow of Knighthood, to defend beauty, virtue, and the gentleness of womanhood, was the practical beginning of that respect in which, in Christian lands, woman is held today.” Men still lorded over women, but there was slow progress. A woman “was still the keeper of the fires, and her voice was heard only beside the fires.”48

Women continued to be the “keeper of the fires,” and the true destiny of those keepers occurred in America. For Comer, America was not just an advanced civilization but a country that advanced because of Protestant Christianity. The Imperial Commander narrated American history from the Mayflower, to the Puritans, to Salem, to the founding of the Republic by emphasizing the role of women in the nation’s development. Pilgrim mothers tended the fires of their husbands and endured unbearable hardships because they sought to found the nation beside their men. Comer observed that men ruled women in the beginnings of the American nation and neglected women’s education because they did not realize that women could be their equals with education. Such was the crux of the issue for the leader of the WKKK: how could men expect women to use the ballot and learn the political system when they had been systematically held back for years? She questioned, “If we go slowly, in our share of the Nation’s management, stumbling sometimes because the path is strange, can we be blamed, whose feet were seldom set and guided in that path?”49 The denial of equal rights for women had caused adversity, which meant women had yet to embrace their political duty. Confined to domestic spaces and denied access to education, women faced nearly insurmountable odds that led to their ignorance of politics.

Comer was not, however, overly negative about the potential of women. By using the examples of pioneer women and heroines in American history, she suggested women could overcome the prejudices they faced and embrace the power of the political process. Comer pointed to Ann Hutchinson, “a woman of ambition and some brains,” and Mary Dyer, a martyr for religious freedom, as two influential women who, though persecuted in their eras, laid the foundation for religious freedom.50 Moreover, Comer stressed that men and women founded the nation together, so that while men used “swords of liberty,” their female counterparts continued to tend the fires. Women fostered the men in their heroism and bravery. Comer proclaimed:

Then—and since—woman taught her sons, encouraged her husband, held up the hands of her fathers, in the case of justice and liberty. What to her are the risks and suffering necessary to save men? She forever endured risk and suffering that men may be born. What fear does women know when her loved ones are in danger—woman—whose love has neither measurable length, nor breadth, nor height nor depth. Hers for countless centuries has been the tending of the fires. Hers forever shall be the duty that the fires she has helped to build shall not go out.51

Women tended the flames of liberty, and for Comer, women, in America at least, had reached a stage of equality. Her rhetoric echoed to the Klan’s rendering of American history, in that she selectively uplifted examples of patriotic women as an example for her Klanswomen. She used national history as evidence of women’s impact on American culture. Comer continued to rely on the language of women as helpmeets to the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

At her urging, Klanswomen were to “go about our business of helping Klansmen feed and keep bright the fires of true Americanism” rather than take charge of the push for liberty.52 The professed equality for women did not match Comer’s assertion of women’s support of men. Despite the calls for equality, the KKK and the WKKK imagined women as essential to the domestic sphere, while men remained the active participants in the public restoration of Christian civilization. Women taught sons and encouraged husbands in the pursuit of liberty. Where did their daughters fit into that paradigm? Were they taught to tend the fires like their mothers? In her discussion of a mother’s power, girls were absent. What about the “virtue of girlhood”? Comer talked directly to Klanswomen as mothers, so that Klan daughters might have been viewed as future mothers. A “lady kleagle” from New Jersey was more direct. In her speech, she noted that the “girls of today are the mothers of tomorrow.”53 Girls were important as potential mothers who would foster and support their husbands and sons, but their possibilities in other initiatives for the order fell short. In spite of her rhetoric of equality, Comer affirmed the Klan’s conflation of womanhood and motherhood, and she ignored the roles of girls as patriot citizens by centering only on sons. Klansmen and Klanswomen were not quite prepared for an active female citizenship, and Comer stressed that women would remain primarily the supporters of their male counterparts.

Klan Parade, Muncie, Indiana, 1923. Thirty thousand people attended the initiation of 600 candidates. Photograph by W. A. Swift. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

In 1928 Comer addressed the Fourth Imperial Klonvokation in Chicago, and her speech once again centered upon the American woman, her progress, promise, and problems. In her opinion, women had advanced. New professions as well as social and economic equalities were now open to American women, and she believed that women would not return to their previous, lowly positions. She critiqued “women extremists” who alleged that women had no physical limitations. For the Imperial Commander, women were still essentially “child bearers” who were “busy through a part of their lives with the reproduction of humanity unless the race is to die and the earth become as unpopulated as before the Almighty breathed into the nostrils of the first man the breath of life.”54 Even though she emphasized child-rearing as the main role for women, she questioned the supposed superiority of men by suggesting again that historically women faced more limitations than men. She interrogated the assumption that women needed men’s governance. The burden of such history rested squarely on the shoulders of women, who were not able to rid themselves of those bonds. That burden plagued Comer, and she admitted it “rests upon my soul.” Due to the critical nature of her speech, she claimed hesitancy for fear of being misunderstood by both women and men. Her speech trod over familiar themes of previous speeches and leaned toward the theological. Women had to free themselves from “our progenitor’s mental servitude” to recognize their true potential.55 Moreover, she stressed that God established the ability of both sexes:

Woman is half the created kingdom of mankind, which is of the Kingdom of God. He made mankind in His own image—male and female created He them. That they should be fruitful and multiply was the Divine command, and each sex has its share in obeying that mandate, with women the mothers of the race and theirs the duty to exercise care and watchfulness over the sons and daughters of the race during the years when character is formed.56

By divine mandate, women were to reproduce the race. Motherhood, again, emerged as the most important role for women because it involved the molding of children into citizens. Comer admitted that not all women would be mothers, but all women had instincts associated with the divinely ordained role. Womanhood and motherhood became one and the same for Gill Comer and the men’s Klan. In that speech, she also reiterated that women were to be helpmeets to men. Together, men and women could create a better world in partnership than men had created alone. Such was crucially important because Comer lamented the state of the nation, particularly the youth. She noted that boys and girls had “taken a bit of control into their teeth” and were “dashing almost unhindered toward a future of unbridled selfishness and unhappy irresponsibility.”57 Parents provided bad examples. Mothers who lacked modesty produced immodest daughters, and children and parents embraced irreligion. Daughters became a pressing concern when they behaved immorally, as such behavior was a threat to citizenship. As potential mothers, their behavior directly affected their offspring. Divorce was on the rise, which suggested the collapse of the home, the sacred foundation of nation and religious faith. There were good men and good women who could restore the nation, and women would be on the front lines to combat immorality in their ranks.

For Comer, women directly impacted American life more than their counterparts in any other nation. With newfound equality, they could assist the men more than ever before. Men and women together could restore religion and order to the nation. Perhaps to assuage the minds of her male listeners, she emphasized that such equality would not mean that a woman would “neglect the home-building and home-keeping for which she is not only more experienced but better fitted than man.”58 It was even possible that women might move from helpmeets to true partners to their husbands with their new abilities. That partnership would lead to a better country for their children. Speaking for the WKKK, she pledged that the order would protect the government, which was “established Christian, Protestant, and white,” to make sure that it remained so. Additionally, the members would raise children that supported those values to safeguard the American home. Women would be the helpmeets who worked to protect the Klan’s vision of a religious nation. Her vision of partnership proposed men and women could accomplish their goals together. Her rendering of equality was a limited one, and it conformed somewhat to the Klan’s vision of white womanhood. Klanswomen might be strong, active participants in faith and nation, but they were still bound first and foremost to traditional roles. Comer struggled to voice equality for herself and her order, but she conflated womanhood and motherhood similarly to her male brethren. In that conflation, women remained the supporters of their husbands and sons. She made it clear that her women wanted to protect rather than to be protected, but the defense of white womanhood required that Klanswomen employ their roles as mothers to claim authority. The ability to nurture and sacrifice remained the uplifted norms for the women’s order.

However, the Klan was concerned not only with the protection of Klanswomen but also with American women more generally. Klanswomen might be able to protect themselves because of their affiliation with the order, but other American women were vulnerable to threats that they were not aware of. For the Klan, threats to white womanhood took the form of Jews, African Americans, and Catholics who might harm the purity of those delicate women. The order seemed most concerned with Catholics and their institutions. The order articulated its fear of Catholics as the danger to white women from both the confessional and the convent, and anti-Catholic lecturers, who gained popularity in Klan circles, stoked those fears to show that Catholicism was a personal as well as political threat.

There is a continuous cry going up, from the lips of thousands of wives and daughters, to be delivered from the terrors of the confessional.59

Comer asserted that Protestant civilization uplifted women, unlike other religious cultures. Klansmen and Klanswomen feared the influence of other religious traditions on young Protestant women, and the order often sponsored lecturers who documented in gruesome detail the hazard of Catholicism to the minds and bodies of young women. According to Kathleen Blee, the Indiana Klan in particular focused on “graphic tales of female enslavement and sexual exploitation” by Catholic institutions. Klan lecturers and various Klan publications obsessed about the celibacy of the priesthood, the treatment and character of nuns, and the stories of Protestant girls captured and enslaved by secretive convents. Blee contended that the apprehension about the sexual morality of white women gave the Klan a large following among Protestants, who were at best ambivalent about Catholics.60 However, such trepidation was more than just an attempt at public legitimacy. After all, white women were seen not only as vulnerable and delicate targets but also as potential mothers essential to the creation of national character. Attacks on white women were harmful to the national body. The Catholic threat revolved around issues of morality and decency, but it also concerned the centrality of women to the formation and reformation of the Christian nation. They kept the fires of patriotism burning and provided religious education for their children. If the purity of white women was at stake, then the Klan’s ideal nation was in danger.

Lecturers claimed that Rome targeted and captured Protestant girls. They affirmed the exaggerated fear and distrust that many Protestants and Klan members had about Catholics. As mentioned earlier, the order labeled Catholics as a menace to the Protestant foundations of the American nation as well as dangerous to the American form of government because of their allegiance to the pope. Their allegiance affirmed what the Klan believed all along: Catholics aligned with the papacy instead of their nation. The message perpetuated by Klan lecturers that Rome targeted women for slave labor and debauchery cemented the church’s status as a possible foe to the American way of life. On the Klan lecture circuit, Klansmen and Klanswomen heard the tales of horror, which motivated both orders to protect white womanhood at all costs. Two of the most popular lecturers were Helen Jackson, “the escaped nun,” and L. J. King, a self-proclaimed “ex-Romanist.” King became a Klansman in the early 1920s, and he and Jackson often lectured together for Klan events. They even staged revivals for the Klan in many towns in Indiana while lecturing on the depravity of priests and nuns.61

Helen Jackson’s popularity emerged from her Convent Cruelties, or My Life in a Convent, which was published in 1919. The volume had seven editions between 1919 and 1924. Jackson documented supposed cruelties at a number of Catholic convents in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Kentucky, and her tale targeted Good Shepherd convents as particularly heinous. According to her own accounts, Jackson was raised in a Polish Catholic family, and from age thirteen she desired to be a nun. Her mother was adamantly against her decision and forewarned, “Helen dear, I do not want to stop you from going to be a nun and go to hell for your lost soul but you will understand me some day and think of what your Ma-me said.” Jackson ignored her mother’s warning and claimed, instead, that the nuns somehow hypnotized her into making the decision. Even more, she reported that membership in a convent might exempt her “from hearing these embarrassing questions that were asked of me at my first confession.”62

The first convent she entered was a Felician convent. Jackson quickly realized that the nuns were not the kind, enchanting nuns she knew previously. Instead, they were cruel and vindictive to their charges. They punished her for many indiscretions, from disobedience to questioning the nun’s authority to attempting to help other girls. Such was the major thrust of her “memoir,” which recorded not only the punishment that the young Jackson faced but also the harsh penalties imposed upon the other young girls at convents. She even escaped, but determined nuns forced her back into the convent against her will by “pinching, punching, and nearly pulling me into pieces.”63 At various points in her narrative, Jackson turned her attention to the reader, especially after egregious acts by the nuns. She asked, “How many girls are struggling in those convents today, so you know? Is your daughter one of the victims, or perhaps your friend’s missing girl? If so, I advise you to do your duty according to the fundamental principles upon which this great republic was founded.”64

The most important principle was liberty. Jackson asserted that the convent, a Catholic prison, blatantly ignored the founding ideal. Convents enslaved girls in secretive places, and the enslavement denied their liberty. She encouraged her readers to save these girls from the injustices they encountered. Moreover, Jackson demonstrated that the abuse impacted Catholic and Protestant girls because priests prided themselves on kidnapping Protestants. The reasoning behind the kidnappings remained obscure throughout her “memoir,” especially the logic for abducting girls. One Protestant girl attempted to escape by rappelling down the side of the convent, but her rope snapped. In her plummet, she broke her leg, and her screaming alerted the nuns. However, the police saved her because she told them she was Protestant and did not belong in the convent in the first place.65 For young Jackson, the Protestant girl was lucky because she was able to escape when so few other girls ever had the chance.

To make obvious the gruesome punishments inflicted by the nuns, Jackson recorded the broken and bruised bodies of the girls. Body lice afflicted them as well. The nuns punished Jackson, now Lena, for refusing to wear an overly warm dress while working in the laundry. (Jackson asserted that the girls’ names were changed, so their families could not locate them.) Her hands and feet were bound, and she was tossed into a small room where she licked up her sustenance “like a dog.”66 Many girls were also dunked in a bathtub full of cold water and lashed with “sewing machine straps,” which left many bruised and unable to walk.67 Jackson reported that the nuns often did not inflict the punishment themselves but had their young charges commit the crimes. The diabolical scheme meant the nuns could not be accused of wrongdoing. After the death of her mother, the nuns allowed Jackson to return home to her family. Unfortunately, her reprieve was short-lived because a priest re-kidnapped her and sent her to a different convent.

The rest of her tale focused on the cruelties she and others faced until her successful escape. Jackson described the deceptive machinations of the nuns. If there were visitors in the convent, the nuns tied up the faces of girls with black eyes to fake a toothache.68 A dear friend of Jackson, Modestus, died because of her chastisement. The nuns intended to give her a “cold water ducking,” but instead tossed her into a “tub where they soaked the sanitary clothes of about one hundred and eighty girls.”69 Modestus’s dying wish was that her family would find out where she was located. Reflecting on the death of her friend, Jackson stated:

Oh, what would you do if your loved one was sick and dying away from home, longing to see you? Would you broaden the dividing line or grant their request? Yet this girl laid here looking as if she would like to see some one for the last time. Do you ever wonder why so many of our girls are missing? I say “Our Girls,” because they are American girls; and if they are not American girls then it is un-American to treat them like that. Why tolerate such slavery and devilish practices in this country.70

She questioned how those practices could happen in a nation that no longer tolerated slavery. Jackson’s enslavement, however, came to an end. She managed to escape with the help of her friend Vivian. Mrs. Graeff, a Baptist, saved the girls by hiding them in her house. Jackson then wrote about the horrors that she had faced in many convents. She hoped that her book would lead readers to suppress convents in America and to save female inmates from the experiences that she faced as a young, vulnerable girl. On the lecture circuit, she regaled audiences with those tales of horror and reported on infanticides that covered up priests’ illicit relationships with nuns.71 Jackson’s “memoir” primarily verified the damage to the bodies of young women and the intolerable cruelty of supposed Catholic prisons.

Her comrade on the lecture circuit, L. J. King, wrote pamphlets and gave speeches on similar topics, but he perceived the threat to American women to be primarily the confessional, which he argued ruined the female mind as well as the body. King claimed to be a former Catholic who was privy to knowledge the average Protestant might not have, and he asserted that the confessional was a den of iniquity for women because of the immodest questioning they faced. The crux of the issue for King was that the Roman Catholic Church required celibacy for their priests, and that requirement led to debauchery. For King, “horrible disorders, seductions, adulteries and abominations of every kind . . . have sprung from this practice of auricular confession.”72 King painted the penitents as “young, beautiful, and interesting females,” and the priests as men “young and vigorous, without the grace of God in their hearts, burning with fires of passion, and in many instances wrought to a frenzy by the vow of celibacy.”73 The Roman Catholic Church thus created a problem because the priests were passionate and the female penitents had to answer indecent inquiries. According to King, such questioning led to dubious behavior between the two parties. The “ex-Romanist” maintained that confession was not a practice of which young women could abstain because it was one of the seven sacraments of the Catholic Church. He wrote: “All her faithful must pass through this cesspool of iniquity. Rome had decreed that her pious shall not escape; but that all should be bound . . . by the relentless irons of the confessional in order to reduce and enslave them to the will and wishes of her priest craft.”74

The practice of confession guaranteed obedience of the faithful. It compromised the purity and modesty of American women. Abstaining from confession was a path to hell, so that the soul was at stake if one neglected confession. The church forced women into the dreaded confessional as part of their religious practice. King affirmed that the inquiries of priests proved detrimental to both the priest and the women. The supposed questions concerned the sexual experiences of the penitents, which he purported often led to relationships between priests and women. Basically, King envisioned the confessional as a tool used by the priests to seduce female congregants, married or single. The “depraved” questioning demoralized the women and made them vulnerable to the “lecherous” priests.

To demonstrate his claims, King used selections from other “former” nuns and priests, including ex-priest Chiniquy and Maria Monk. Using Chiniquy’s text, King claimed many noble and modest women fell victim to vile priests. Between 1874 and 1875, Chiniquy wrote The Priest, the Woman, and the Confessional, which supposedly documents confessions he heard as a priest in Canada. Bishop Duggan from Chicago, however, excommunicated him in 1858 because of his previous indiscretions with female congregants.75 Nevertheless, King still culled examples from Chiniquy’s works to provide a general description of what occurred in the confessional. For example, he describes the penitent in her struggle against the priest: “She grows pale and trembles like an aspen leaf, her bosom heaves, showing the terrible storm within; her lips quiver, then move as she pleads to be spared the ordeal. She pleads, pleads for self-respect and chastity.” King characterizes the priest as “the bachelor confessor” who seeks to “uncover every secret chamber in the soul of the penitent.”76

Not surprisingly, the priest wins the battle of wills because of his claim that the woman must confess every sin or vile thought to be absolved. King laments that “every garment of modesty is torn in twain and the last vestige of self-respect has gone down leaving the heart bare, and open to his unhallowed gaze.”77 Using the metaphor of rape, King suggests that the priest is able to conquer the heart and minds of the women in the confessional. Through the confessional, priests seduce women, which leads to illicit sexual relationships, illegitimate children, adultery, and perversion. The confessors destroy female virtue, a requirement of confession rather than a consequence. Moreover, he also asserts that nuns and priests use the confessional as a cover for their sexual relationships. The “ex-Romanist” urged husbands and fathers to protect their wives and daughters from such evil, arguing that Catholic machinations ruin women, putting female modesty and virtue at stake. King implored Catholic women to turn away from the “deceiving words of the church of Rome” and embrace “the invitations of our Savior, who has died on the cross, that you might be saved; and who along, can give rest to your weary souls.”78 He felt they should convert to Protestantism to protect their modesty. Not surprisingly, Catholics did not welcome King’s message. He claimed that the Knights of Columbus and Catholic mobs attempted to kill him multiple times because of his exposés on the church.

The writings and speeches of King and Jackson reverberate with themes of anti-Catholicism from the nineteenth century. Both Marie Anne Pagliarini and Tracy Fessenden argue that anti-Catholicism functioned as a method for Protestants to renegotiate gender norms in the nineteenth century. Pagliarini points out that the abundance of anti-Catholic literature declares the sexual immorality of Catholicism.79 Building upon Jenny Franchot’s work, she reasons that Protestants imagined the Catholic priest as sexually depraved because Protestants believed Catholicism represented “a threat to the sexual norms, gender definitions, and family values that comprised the antebellum ‘cult of domesticity.’”80 Anti-Catholic literature focuses on the importance of the purity of American women, and such literature has a pornographic quality that appealed to Protestants while also reestablishing the importance of sexual norms. The tales portray young women defiled by priests or convent life and serve as a lesson that Catholicism endangers both young women and family life. For Pagliarini, the sexually perverted priest and the dangerous convent are pitted against the pure American woman whose greatest asset is her sexual purity. Catholicism emerges as a path to sexual immorality that not only endangers individuals but also families and the larger society. Tracy Fessenden proposes that anxiety over gender roles drove the Protestant attack on Catholics.81 Nuns and prostitutes surface in nineteenth-century literature as women of sexual excess.

In particular, Fessenden maintains that anti-Catholicism helped create and preserve the Protestant woman’s sphere in opposition to the realms of prostitutes and nuns. Protestant women defined their sphere by placing boundaries between themselves and other women. Anxieties overflowed in their characterization of liminal women because nuns were enshrouded in secrecy, and prostitutes participated in behavior that was too public.82 Catholicism was, once again, the imagined enemy by which Protestants sought to define themselves and project their anxieties about society.

The rhetoric of anti-Catholicism reified the gender norms that Protestants embraced and maintained the domestic sphere. The tales of convent horror and lecherous priests affirmed notions of what womanhood should be, and King’s and Jackson’s works uplifted similar themes. The depraved Catholic of the convent, or confessional, illuminated the delicate nature of Protestant womanhood and emphasized the fact that white Protestant women could not protect themselves. In their respective works, King and Jackson solidified the Klan’s representation of white womanhood as fragile, vulnerable, and defenseless. The nuns and priests proved to be the villains in their stories, emphasizing the harm that women constantly faced.

The careers of both lecturers were born of fears of the Catholic Church. However, Catholics did not ignore the sordid tales and called into question the legitimacy of the narratives. A Record of Anti-Catholic Agitators listed all the known anti-Catholic lecturers as well as other Catholic detractors. The pamphlet included Jackson, King, and various leaders of the Klan (notably H. W. Evans). Jackson surfaced as a fake ex-nun sent to the House of the Good Shepherd in Detroit because of her own misconduct, including questionable behavior with young men. King was exposed as a fake ex-priest whose lecture tour proved controversial, and he had been charged with assaulting a woman in Indiana because she protested a portion of his lectures. He was also arrested for inciting riots and resisting arrest.83

Both King and Jackson were accused of acting in ways that they publicly disdained in their writings and lectures. Jackson acted immodestly, and King had harmed a woman. Whatever their indiscretions, however, they were both popular on the lecture circuit for the Klan. They confirmed the Klan’s worst suspicions about the Catholic Church’s treatment of women. They also demonstrated the helplessness of white women and their need of protection from Rome. Their stories of terror and debauchery echoed the Klan’s unease about white women and the menace to the American home. Cruel convents and lecherous priests were not the only attacks by Rome on white womanhood. Catholic hierarchy’s approach to marriage proved threatening to the virtue of Protestant women as well, because the Klan believed that Rome’s next line of attack involved the sanctity of marriage.

To change the established American customs concerning marriage would produce social confusion, discord, and finally civil war.84

According to Imperial Wizard Evans, “Homes and family life are the warp and woof of America.” Patriotism was the “overflowing of family life in National life,” and Evans found that “spiritual autocracy” damaged the sacred institution. Rome, he accused, alleged the only right to preside over the marriage ceremony. The implications of Catholic jurisdiction over marriage were frightening because the order believed that the home would be “entirely under their control.”85 That would mean that Catholics would have a religious as well as political advantage over Protestants, and the nation might bend to Catholic influence. For Evans, marriage, and the laws surrounding it, proved to protect the “chastity of American women” and the “honor of the mothers of America who have been united in the holy bonds of matrimony by any person authorized by the law to perform the ceremony.”86 A challenge to marriage equaled opposition to the honor and purity of American womanhood, and the Klan needed to act to stop any religious group from harming the American home. Changing “American customs” of marriage would prove disastrous because of the potential for social upheaval.

Moreover, Evans reported confusion as to why religion needed to be a part of a legal agreement like marriage. He wrote, “It is inconceivable to me that religion enters into the ceremony of marriage by and beyond adding approval of Almighty God to any union formed in accordance with the law of the land.” The approval from God, he asserted, likely emerged from Christian tradition because it contained no legal benefit. What troubled Evans was that Catholic practices would somehow degrade Protestant marriages. If the Protestant marriage bond was not valid, then the women in those marriages would lose all claims to honor and virtue. The American home might be disrupted if Protestant marriages were declared null and void.

Evans also feared the “intrusion of the Roman hierarchy” in the home because of a required “contract from the parties marrying when they are of different religious faiths, that the children born of marriage shall be raised in the Roman Catholic Church.” For Evans, this was another example of the Catholic attack on religious freedom because of “the religious control of minds yet unborn.” The parents in “mixed” marriages promised their children to the Catholic Church without the child having a say in his/her religious faith. To protect the home and the nation, Evans urged the Klan to “plead for the enactment of laws to protect the religious liberty of unborn Americans.”87 Catholic control over marriage could lead to Catholics’ control over the nation if they were continually promised the religious adherence of the unborn. In Evans’s logic, the unborn would become citizens under the auspices of Rome.