CHAPTER 6 |

“Rome’s Reputation Is Stained with Protestant Blood”: |

“It [the Indiana Klan] has never been accused of violence,” says Mr. Frost, “and in a recent riot which I happened to see at South Bend the aggression was entirely from the other side. That bloodshed was prevented was due to the strenuous efforts of Klan leaders.”

—THE TRUTH ABOUT THE NOTRE DAME RIOT (1924)1

Because of the intolerant views held by Rome, thousands of Protestants have been murdered in the past, and until Rome proves that she has discarded those murderous policies, Protestants will do well to fear her.

—IMPERIAL NIGHT-HAWK (1924)2

In Roman Catholicism and the Ku Klux Klan (1924-1925), Charles E. Jefferson seeks to explain why the hooded order opposed Roman Catholicism. The pastor of the Broadway Tabernacle in New York, he makes it clear that he is willing to criticize both movements for their critical flaws in his effort to inform the American public about the Ku Klux Klan and to be a meditating presence between the Klan and its foes. In a sermon of the same title as the book, Jefferson examines why “the Roman Catholic Church . . . excites the Klan’s antagonism.”3 According to Jefferson, the Klan was not essentially an anti-Catholic order. The numerical lack of Catholics in states under the banner of the Invisible Empire did not justify such behavior. He reasoned that since Catholics only made up “one-seventieth” of Christians in Georgia and one-fourth in Texas, the Klan could not be opposed to them just because of their presence. By Jefferson’s logic, it would make no sense for the order to expend its energies on such a small population. Numerical absence, however, did not mean that Catholics were ignored either. Catholics, the pastor admitted, proved to be quite troublesome to the order because of their supposed lack of patriotism. Jefferson noted that the order was primarily a patriotic reform movement that sought to improve America for Americans.4

Catholics stood in the way of this reform. The pastor centered on the Klan view of Catholics because “the Ku Klux Klan gives the impression that a certain class of Americans are being discriminated against because of their religion.” After asserting that he was not a Klansman, he argued that the Klan was not entirely religiously intolerant. The author explicated the Klan’s complicated position on its Catholic neighbors. First and foremost, the KKK did not oppose Catholics because of their worship, even if it was “Christianity in Italian dress.”5 Jefferson wrote, “Americans have no objection of Catholics making use of candles and incense, holy water and the sanctus bell, and the gorgeous robes of the priest.” Additionally, he wrote, Protestants did not mind Catholic doctrines, including transubstantiation, papal infallibility, purgatory, or the adoration of the Virgin Mary. He further argued that Protestants have no problem with Catholics believing such doctrines if they were able to actually believe such things.6

The quarrel between the Klan and Catholics lay firmly in the realm of politics. The Klan opposed the government of the church and hierarchy because of the threat of mass mobilization under the command of the pope. The New York pastor upheld the KKK position on the Catholic Church. The danger of the papacy and the hierarchy was one that Jefferson agreed all Americans should be aware of. Moreover, Jefferson asserted that Rome was partly to blame because the church ignored and disdained Protestants, which practically forced Klansmen to take up their hoods to protect white Protestant supremacy in America.

Despite his attempts to understand the Klan’s relation to the church, Jefferson approached the issue differently from his Klan brethren. He urged his listeners and readers to recognize the patriotism and dedication of Catholics throughout American history. He pleaded with them to think of Catholicism at its best rather than obsess over the church. Such obsession made them the “victims of hysteria” who inhabited a “whole world [that] swarms with enemies.” For Jefferson, that conspiratorial thinking elicited a divine response. Anxiety was “the penalty that God inflicts upon men who always think of their fellow men at their worst.”7 The pastor wanted to comprehend the Klan’s persistent fear of Catholics, and he alluded to the many portrayals of Catholics present in Klan print culture. The hierarchy and the influence of the pope made Jefferson nervous, but he did not fully agree with the order’s presentation of the church as an enemy of Americanism. Jefferson instead looked for the best in Catholic neighbors and their institution rather than condemning outright the religious tradition. The order, however, did not allow such a gracious interpretation.

The KKK feared Catholics because of their allegiance to an opposing religious movement, their ties to immigration, and the hierarchy of the church, which appeared secretive and possibly dangerous. Catholic strangeness caused the order’s anxiety. Catholics were the perfect foil to the Klan’s white American Protestantism; they epitomized all that the Klan hoped not to be. The Klan’s imaginings of the church and her members showed acute concerns with nationalism, religious orientation, womanhood and manhood, and whiteness. The church symbolized all that could lead to the downfall of the Protestant nation.

On May 17, 1924, a riot broke out between Notre Dame students and Klansmen that actualized the Klan’s fears about Catholics and their place in America. In the streets of South Bend, young men from the Catholic university attacked and ripped robes off of Klansmen who had gathered for a rally. Klansmen fought back. The rioting lasted for a total of three days and finally came to an abrupt end.

For the KKK, the battle quickly metamorphosed into a fight over American ideals. In the order’s accounts, Catholics resorted to attacking Protestants in the streets. In his Notre Dame vs. the Klan (2004), Todd Tucker employed a Catholic narrative of the riot, in which the men of Notre Dame not only won that battle but also won the larger war. For Tucker, the riot in South Bend stopped the nefarious organization in its tracks.8 Despite Tucker’s earnestness, Klansmen being disrobed and threatened by Catholic students did not lead the order to the brink of destruction. Rather, in some ways the riot emboldened Klansmen and their fellow Protestant brethren in their verbal and printed attacks on Catholics.

The riot was significant and underplayed in the history of the 1920s Klan. While Tucker’s work examined both the Notre Dame and Klan experiences of the riots, he overlooked the Klan’s religious mooring. Moreover, he assumed, like much of the literature on Klan-Catholic relations, that the Klan simply hated Catholics. The riots, and the press surrounding them, tell a dissimilar story. The order feared Catholics as a threat to nation and to white Protestant dominance, even as Klan members claimed a place in larger culture. For the 1920s Klan, Catholics were powerful enemies, but Protestant citizenry still dominated American life. The Notre Dame–Klan riots elucidated Jenny Franchot’s hypothesis that Protestants were attracted to and repulsed by Catholics in her work on Protestant-Catholic relations of the nineteenth century. The Protestant KKK was both attracted to and fearful of its enemy.9

Tucker’s provocative work, then, overlooked the intricacies of the riots as well as the rhetoric of Americanism employed by both sides. Those riots demonstrated how both Catholics and Protestants in South Bend utilized the rhetoric of faith and nation in very similar ways. The men of Notre Dame struggled with the issue of being Catholic in America, and the Klan lamented the decline of Protestant America because of the presence of Catholics and other outsiders. Both were concerned about the character of nation and how their religious affiliations affected their citizenship. To explore the riot in detail demonstrates how ideas of American nation intermingled with religious ties and white supremacy. Moreover, the examination of the riot and its place in Klan print culture highlights how the Klan worldview functioned. Protestantism, whiteness, gender, and nationalism coalesce in Klan renderings of the riot and allow one to see how those fixtures function together to define the order. The Klan’s characterization of Catholics, as a menace to American culture, explains why both sides interpreted the riot in such stark terms.

Rome’s reputation is stained with Protestant blood.10

The Imperial Night-Hawk claimed that the Klan was “unalterably opposed to religious intolerance,” but the news organ also professed common suspicions of Catholics held by Protestants. As the Night-Hawk noted, the “infallibility of the church,” its disdain for Protestant marriages, and its belief that “all Protestants are heretics” led many to “dread its power.” Rome proved to be intolerant and inflexible, not the Klan. The weekly reported that “Rome’s reputation is stained with Protestant blood.” The provocative statement said much about how the order interpreted and reinvented the Protestant relationship with Rome. Rome became the active oppressor of movements that it supposedly considered heretical. According to the Night-Hawk, the Catholic Church had a crimson-tinged history. Until the church reckoned with that history, how could Protestants feel anything but dread? Protestants could not trust the intentions of the church. The article continued:

It is regrettable that there is a religion in America, that cannot be trusted. It would be satisfying to feel that no religion considers our wives concubines or our children bastards. It would be equally gratifying to know that no religion stands for murder and devilish cunning in its dealings with other religions. And, it would also be pleasing to feel that no church in America wants to limit freedom. But, until Catholics prove that they do not stand for such principles . . . safety demands that Protestants stand together, not to molest Catholics, but to protect themselves.11

The Night-Hawk insisted that Catholics must be watched to safeguard Protestants and American liberties, and such precautions were preventative measures. As the editorial made clear, Catholics could not to be trusted because at best they were saddled with a bad reputation, and at worst they were still an active threat to Protestants. If Catholics had control of the nation, Protestants would lose their constitutional guarantee to religious freedom and control over their own marriages. The Night-Hawk painted a dire image of the nation under the firm control of the hierarchy. A Texas Klansmen concurred with the weekly’s assessment. He argued that “Romanism” sought to “lay its slimy, blood-stained, murderous hands” upon the public schools, Protestant marriage, and the government.12 Romanism—more loathed than Catholicism because of its political rendering of the Catholic Church—could potentially corrupt American institutions.

While the order proved highly critical of the hierarchy, its stance did not necessarily affect members’ views of ordinary Catholics and beliefs. Individual Catholics garnered protection for the freedom to worship. Imperial Wizard H. W. Evans emphasized that the Klan had no quarrel with the individual’s right to worship. He argued, “The right to worship God according to the dictates of one’s own conscience is necessarily one of the fundamental principles of human liberty.” However, that right could be compromised if religious practitioners intruded upon the state. Evans affirmed that those “devotees” would have to “abstain” from political behavior for “their own protection.”13 The order grudgingly admired the efficiency of the hierarchy and employed it as a model for the Klan’s own bureaucracy. The difference, of course, was that Protestant bureaucracy would be on the side of good intent, unlike the Catholic counterpart.

In a position paper on Roman Catholic hierarchy, H. W. Evans pinpointed one particular threat. The position of the pope within the tradition unnerved Evans, especially the pope’s supposed challenge to the separation of church and state. He wrote, “The individual Klansman recognizes the right of the individual Catholic to worship God, pope, or idol . . . but the claim of the pope that he is God’s divinely appointed . . . representative on earth complicates” the Catholic position in the nation. Evans believed that the pope’s position gave him special power over the state. As God’s human agent, the pope might hold more sway over the minds of practitioners than calls to patriotism by national governments. For the Imperial Wizard, this indicated that Catholics would be loyal first to the pope and then to America. Catholics, therefore, supported faith over government, which meant that they might not be prepared to support the state in all necessary arenas because of their religious allegiance. Evans, who was more subtle and cautious than his predecessor, observed that “the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan do not believe that persons of the Roman Catholic faith necessarily are un-patriotic, or in any way inferior to people of other beliefs, but we do hold that a system of Church government which claims dominance over state governments is dangerous to the state.”14

The Klan fretted about the church because of its potential for political interference. In the Klan view, the church’s system of teaching and government contradicted American principles and values. Individualism and religious liberty were not foundations of the Catholic tradition; rather, they were created, with difficulty, for Catholics to fully embrace the character and heritage of the nation. Bound by hierarchy and dominated by priests, bishops, and the pope, Catholics were unable to make their own decisions or to embrace fully American institutions. Evans feared that Catholics would destroy sacred American liberties because of the pope’s influence on their hearts, their minds, and especially their votes. Through the pope’s dictate, the faithful might block votes, which could prove ruinous not only to democracy but also to the sacred separation of church and state. To protect the nation from the church might be viewed as intolerance. Evans believed it to be a defense of all that he held dear: “For the Roman Catholic as a man we are sorry, for the Roman Catholic hierarchy as a semipolitical religious organization we have an antipathy bred into us from the loins of our forefathers, the men who conquered the wilderness and built a nation, and set ablaze the beacon fires of liberty that all the world might see by that light the true road of happiness.”15

Evans was not demure in his denunciation of the church’s political organization, and he made it clear to his Klansmen that Catholics were a threat to the liberty of their Protestant nation. Interestingly, this logic could have legitimated Klan persecution and intolerance of Catholics, but the print culture remained remarkably silent about the Klan’s actual treatment of the church and its members. Various Klan journals denounced Catholicism in their pages, but there was no documentation of how the Klan reacted to adherents of the faith.

Instead, the print highlighted the persecution of the Klan by Catholics. The order’s opposition to the hierarchy led to the maltreatment of the Klan at the hands of the hierarchy and some willful individuals. Evans warned his members that “the heavy weight of Catholic persecution . . . is a cross we will bear,” and bear they did.16 The Night-Hawk documented various incidents of Catholic harassment of the Klan. In New York, Catholics and Jews supposedly championed the Walker Bill, which applied only to the order, instead of broadly to all secret organizations. The Walker Bill required antimasking, filing membership lists with the state, and limiting mailing and political participation of the order. Walker, according to the weekly, was a supposed Catholic or at least sympathetic to the Catholic cause.17 The support of the bill demonstrated to Klansmen what they had believed all along: their foes were out to get them.

In one bizarre instance of Catholic harassment, Nelson B. Burrows claimed that the Klan abducted him and branded the letter K on three different body parts, including his forehead. At first, Burrows, a Catholic convert and a member of the Knights of Columbus, received support from his community of Rochester, New Hampshire. However, once the attorney general began questioning him on the attack, it became apparent that Burrows concocted the whole scheme to place the blame on the Klan. He staged the hoax and branded himself. The Night-Hawk reported that Burrows hatched the elaborate plot to harm the reputation of the order in Rochester because of a recent spike in Klan membership. Burrows, who fancied himself a religious martyr, hoped to turn the public against the order. The Night-Hawk noted that many people attempted to blame the KKK, but “the truth always comes out, sooner or later.”18 This plot, in particular, represented the fanatic persecution that the order confronted not only from the hierarchy but also from rogue individuals. Moreover, Burrows was a member of the Knights of Columbus, a fraternal order that the Klan believed was full of nefarious intentions toward Protestants in general and the Klan in particular. Thus, if Catholicism made the Klan anxious, the Knights of Columbus (KC) proved more menacing. The fraternal order, an organization of Catholic men, appeared harmful to the purpose of the order. Klan leaders conspiratorially noted that the KC engineered schemes against them.

To demonstrate the hazard of the KC, an Arkansas Klansman submitted an article from the Memphis News Scimeter, which detailed the dangers of Catholicism as well as his own analysis of the threat, to the Night-Hawk. The Scimeter pointed to the creation of two new American cardinals and the prowess of the KC. The addition of cardinals made visible Rome’s encroachment on America. However, he proved more concerned about the possible power of the KC. Overall, the Arkansas Klansmen’s position was similar to the standard line about the Catholic Church being a “master of political intrigue, masquerading under the guise of religion.” More important, he uplifted the threat of the KC as the “militant arm” of the church. He pondered, “Or is it true, that the Roman Catholic Church . . . has so organized its militant arm . . . that it is now ready to remove its mask, throw down the gauntlet and defy patriotic American Protestants to do their worst?” America, in all her focus on liberty, created “a Frankenstein monster which now shamelessly threatens to devour its benefactor.” By allowing freedom of worship and immigration, the nation had opened its doors to the church, its political apparatus, and varied missionary attempts. The church was powerful, and its fraternal order might have proved to be the most powerful in America, according to the Klansman’s rendering. Catholic Knights took their orders directly from Rome, and the protection of the hierarchy was their central goal. With the power and support of the KC, the Klansman dreaded that the church might be unstoppable. However, the KKK’s opposition meant that the hierarchy could not maintain reprehensible plans for America. The order imagined that its Protestant Knights were the only ones defending the nation from Catholic danger. To differentiate the order from other Knights, the Klan sought to demonstrate that it was the truly American order with the “blood of pure Americanism coursing” through its members’ veins.19 The other Knights, by default, were not actually American but rather pawns of a foreign interloper.

American or not, the KC had to be exposed to show its militant intentions and its hatred for Protestants. To further document the menace of the KC, the Klan issued a pamphlet titled Knights of the Klan versus Knights of Columbus. The pamphlet represented the issue in stark terms. One could either be allied with “the Roman Catholic hierarchy as representative of the Pope of Rome, or with the Ku Klux Klan representing Americanism in this country.”20 This “with us or against us” stand, according to the pamphlet, was no fault of its members. Catholics had caused the divisive rift by attempting to take over American government. The Catholic Knights were the strength behind that attempt. Additionally, the KC was to Catholicism what the Klan hoped to be to Protestantism: a militant, religious army fated with the task of protecting the faithful. Interestingly, the order ignored that they were parallel organizations and instead demonized the other Knights and their hypothetical practices. The KC was dangerous precisely because members sought to defend Catholicism, which was ironic considering the Klan envisioned itself functioning in the same but legitimate way for Protestantism. The defense of the faith was a virtuous task, but the defense of other religious movements was represented in the order’s writings as harmful and intolerant.

To present the motivations of the KC, the aforementioned pamphlet contained a supposed KC oath interspersed with various images presenting Catholic torture of Protestants, supposedly from the Inquisition. The images of Catholics hanging, burning at the stake, and generally threatening and harming Protestants provided the visual evidence for the legitimacy of the oath. The images made the claims of the oath tangible and concrete, and Protestant readers might have been duly convinced by the depictions of torture. The interlacing of words and images clarified the Klan’s intentions: to malign the Catholic fraternal order. The oath declared:

I will defend this doctrine [Roman Catholic positions on Jesus, the Virgin Birth, the papacy, etc.] and His Holiness’s right and custom against all usurpers of the heretical or protestant authority. . . . I do further promise and declare that I have no opinion or will of my own or any mental reservation whatsoever, even as a corpse or cadaver . . . but will unhesitatingly obey each and every command that I may receive from my superiors in the militia of the Pope, and of Jesus Christ. . . . I do further promise and declare that I will when opportunity presents, make and wage relentless war, secretly and openly, against all heretics, Protestants and Masons, as I am directed to do, to extirpate them from the face of the whole earth; and that I will spare neither age, sex, or condition, and that I will hang, burn, waste, boil, flay, strangle, and bury alive these infamous heretics: rip up the stomachs and wombs of their women and crush their infants’ heads against the walls in order to annihilate their execrable race.

The graphic words made the images appear tame. The oath avowed the destruction of heretical Protestants in grotesque and visceral methods. It proved what the Klan had believed all along: the hierarchy was waging secret and open wars against them. The oath confirmed the Klan’s worst fears about the KC, including its unquestioning devotion to the pope. Catholics, again, became the unthinking followers of a powerful religious leader. Additionally, the pamphlet provided “evidence” that Catholics harmed heretical Protestants as well as the permissible violence committed by the KC under the dictate of the larger church structure. Men, women, and children were not safe from the Catholic fraternal order and its wicked intentions. The violence was not limited to Protestants, however. If a Knight of Columbus was weak or uncommitted, the oath detailed his fate as well. The member might have “his brethren . . . of the Pope cut off my hands and feet and my throat from ear to ear, my belly opened and sulphur burned . . . and my soul shall be tortured by demons in eternal hell forever.”21 For the Klan, what more evidence could one need to show the violent tendencies of the KC, or of Catholics in general? The oath served as a warning to those who did not align with the order that if Catholics conquered America, torture might await all Protestants. It was clear that unlike Pastor Jefferson, the Klan wanted to view Catholics at their worst, even if it was an imagined worst.

Not surprisingly, Catholics responded to the KC Oath and asserted its falsehood. Our Sunday Visitor, a national Catholic weekly, denounced the fake oath and its continued popularity. The “bogus” oath continued to be used despite “a committee of prominent Masons,” who vouched that “no such obligation forms any part of the ritual work” of the KC. The fraternal order even published the real oath as a countermeasure. The Visitor noted that the New York World proclaimed the oath was fake and documented that “paid organizers of the Klan” circulated it. Moreover, the Visitor questioned the Klan’s own oath as dangerous and harmful.22 For the weekly, the Klan willfully used a bogus oath to malign Catholics while its own oath recorded the threatening nature of its order. To support those denouncements, the Visitor offered a $1,000 reward to anyone who could prove the oath was “genuine.” The reward was also offered for any documentation of “misstatement of facts concerning real Catholic belief and practice on subjects treated.”23 For the weekly, the Klan’s persecution of the Catholic Church actually helped the church in its cause. The church could not change bigoted minds, so Klan membership demonstrated who the bigots really were.

The Visitor reported that the church benefited from all of the negative press and argued, “The more Protestantism espouses the Klan, the more its cause is sure to be injured, because where the Klan disgraces itself, Protestantism must be disgraced.” The order, in its attempts to discredit other religious movements, was presenting a seamy side of its own faith. Protestants, then, had to repudiate the Klan or suffer a fall from grace at the hands of the order. Additionally, the Visitor claimed that those tactics actually helped the church because members and new converts came to its defense. The weekly reported, “In a nearby city, where the Klan became very powerful, every Catholic became zealous; the Knights of Columbus Council initiated one hundred new members” and “a wealthy Catholic donated a home to the Knights.” Klan actions, according to the weekly, actually led to growth of the KC, which was obviously not the order’s intention. The Visitor also responded to Klansmen in a gentler manner than the hierarchy was treated in Klan newspapers. The weekly affirmed the order’s anti-Catholicism, but “we must not presume that every person who has joined the Klan has anti-Catholic antipathies in advance.”24 The motivation to join was not necessarily driven by that antipathy, and the Visitor sought to give Klan members the benefit of the doubt.

The order was not so gracious in its renderings of the KC or the church as an institution. Klansmen were at best ambivalent about Catholics and their position in the nation and in the world. Their condemnations of the church and the Catholic Knights bordered upon hatred and were fueled by deep mistrust of the church’s intentions. The order was on the defensive, watching and waiting for the despicable intents of Rome to become public. Catholics repulsed and attracted Klansmen, and more often than not the order chose to interpret the church as a political organization in religious clothing. The order feared what impact Catholics might have on the political realm, yet much of the ambivalence about the church revolved around the Klan’s professed Protestantism. To prove the distance between the religious movements required exaggeration and accusation.

The riot in South Bend proved to be a candid example of Catholic intolerance and persecution for the Klan, as well as evidence of the order’s fight to uphold true Americanism. The battle in the streets became a canvas colored by Klan fears and anxieties about Catholics. For many Klansmen, that event proved that even ordinary Catholics could have despicable intentions toward the order. It was a self-fulfilling prophecy that allowed the order to present all that it upheld under vicious attack. Much like its understanding of the KC, the Klan portrayed those events to fit previous narratives about Catholics and their avid loathing of all things Protestant and American. The riots, similarly, gave “evidence” to Klan claims about the peril of the nation.

Students of Notre Dame College . . . are the latest to commit an outrage against citizens of the Invisible Empire.25

The Fiery Cross reported the following about the Klan–Notre Dame Riot of 1924: “In South Bend, Indiana, while it seems impossible, students of Notre Dame, a Catholic university, burning with hatred, attacked men and women . . . and trampled under their feet the American flag.”26 The riot became a pitched battle between Protestants and their fierce attackers, Notre Dame students (who represented the whole of Catholicism). The order viewed the event as indicative of Catholic affronts on Americanism, their hatred for Protestants, and their continued persecution of the Klan. In essence, the riot proved to Klansmen that their beloved nation was under attack, and they were the victims as well as defenders of the noble heritage of the nation. Their depictions, then, present their victimization. Moreover, reports of the rioting served as a rallying cry to mobilize the white Protestants not only of South Bend but also of the nation. The riot legitimized the Klan’s worldview and demonstrated that its concerns were tangible and real. The assault by Notre Dame students illuminated that Catholics were a menace that needed to be stopped.

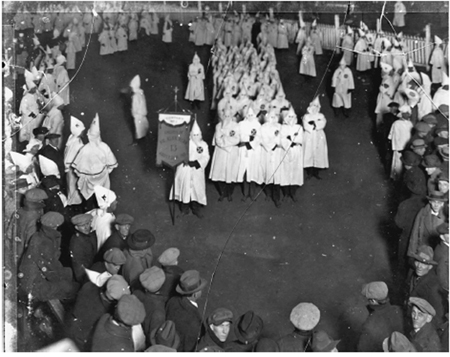

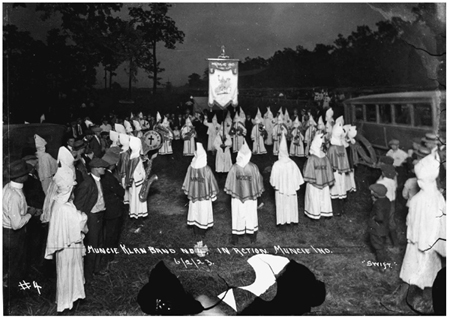

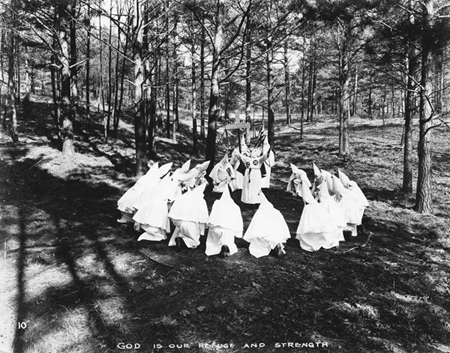

Klansmen on parade. Courtesy of Ball State University Archives, Muncie, Indiana.

Interestingly, the riot in many ways was unremarkable. It was cataloged as one of many incidents of persecution. For the Klan, the event was only the “latest outrage” faced by “citizens of the Invisible Empire,” which suggested the normality of persecution that the Knights faced. According to the Night-Hawk, May 17 started as a mundane Saturday. Klansmen gathered in South Bend for an ordinary ceremony and parade. The villains of the weekly’s rendering were the Notre Dame students, who opposed a “peaceful assembly of one hundred percent Americanism.” Those students uncovered the location of the Klonclave, the assembly, and they “booed and hissed” at all the men who had gathered at the hall. The Night-Hawk characterized the beginning of the riot in the following terms:

A 1924 newspaper clipping from South Bend, Indiana, describes the initial skirmish between Klansmen and Notre Dame students. The students disrobed several Klansmen and then proceeded to wear the “captured costumes.” Courtesy of the University of Notre Dame Archives, Notre Dame, Indiana.

At about half past eleven, when the students realized that the Klansmen intended to carry out their purpose in a quiet and orderly manner, they [the students] became violent and began to stone an American flag hanging from the Klavern window and to smash the windows of the building. As the Klansmen left the hall, they were pounced upon[,] beaten and cursed by the students of Notre Dame. The Klansmen, as is their custom, refrained from fighting back those who opposed their movements and actions, again proving to the world that they are law-abiding citizens, willing and ready to let the law take its course.27

The Klan news organ presented the Klansmen as innocent victims of many indignities. According to the weekly, the police did not come to the order’s aid because much of the police force was Catholic. Those sectarian police officers did nothing to halt the student escapades. By late afternoon, Protestant policeman joined the fray to protect their kindred citizenry of South Bend. Interestingly, the South Bend News-Times described the police presence as more substantial in number. According to the paper, all available police reserves were called in to quell the riot. Policemen wielded clubs indiscriminately at both parties and arrested Klan and anti-Klan factions.28 The order, however, emphasized not only the lack of police presence but also the larger motivations of the rioters: to assault all the Protestant citizenry. By the order’s accounts, the students enlarged their attack to include any Protestants, whether they were affiliated with the Klan or not. All white Protestants became potential targets and victims of the rowdy students.

On May 18 the rioting was quieted by rain, and the students returned to the university. However, the street clashes began fresh on Monday, May 19, until Father Matthew Walsh, the president of Notre Dame, intervened. According to the Night-Hawk, students mercilessly trampled American flags and harmed the citizenry. From the order’s perspective, the riot boiled down to attacks on Klansmen, Klanswomen, and civilians because they were Protestant and American, and their enemies, the students, lacked patriotism.

To document the persecution, the Night-Hawk described the event and the order crafted a pamphlet, The Truth about the Notre Dame Riot. In the twenty-one-page document, the Klan inserted editorials, eyewitness accounts by Klan and non-Klan writers, and opinion pieces. The pamphlet documented the injustice Klansmen faced at the hands of riotous Notre Dame students and a cover-up by the media that revealed the press’s support for Catholics. It also provided a time line from the first attack to the development of “general rioting.” In the so-called general rioting, students attacked Protestant men, women, and children. Students trampled flags, accosted women, destroyed robes, and even harmed the young and the elderly in the fray. The students were clearly on a rampage. Robes “were torn from them and torn into strips,” and students tied “the strips about their arms” and gave “them to girl sympathizers to mark them as friends.”29 One eyewitness, Wingfoot, noted that the students quickly outnumbered the Klan. The order decided not to hold its parade, not because of numerical disadvantage but because members feared more bloodshed.30 Wingfoot also reported the savage beating of an elderly couple. He wrote, “One of the most distracting scenes was the beating of an old white-haired couple who carried small American flags.” The elderly woman was injured.31 According to the Fiery Cross, police sustained countless injuries, and “hundreds of women suffered the injured indignities of receiving threats and scurrilous names.”32 In one incident mentioned again and again in the pamphlet, a student accosted a baby girl in the tumult. One account rendered the story most dramatically:

Finally, at one of the cross streets, I saw several of them [students] run across the street and surround a woman who was pushing a baby carriage on which was fastened a small American flag. One of them tore the flag from the carriage and pulled out the baby. He slapped the baby first on one side of the face and then on the other, and threw it, literally threw it, to the woman I suppose was the mother.33

According to Wingfoot, that was one of the “worst outrages of the day,” because the “baby girl was struck in the face by a student and her mouth was badly lacerated.” According to the Klan, one student stooped so low as to slap a baby because her carriage sported a flag. Such showed the desire of the students to attack any Protestant Americans no matter what age. The elderly and the young were full-fledged targets. The assaults were not limited to people and included symbols of Americanism. Students trampled, ripped, stomped, and otherwise desecrated flags. Wingfoot reported, “When appeals came from American citizens not to stone and trample flags, students cursed and said they ‘were not American flags.’”34 In excerpts from the Noble Country Democrat, a purported non-Klan editor commented on the calamitous events and the defilement of the flag. The editor of the Democrat disdained the South Bend police as Catholic and as “appear[ing] to be more ignorant than they sound.” He also interviewed “a very gentlemanly Catholic” who claimed “he didn’t like Klansmen,” but “he could not condone the desecration of the flag.” The editor continued at length to make sense of the riot and the possible Catholic responsibility for the event:

We much prefer to think this whole disgraceful affair at South Bend was fostered by that small thirty to thirty-five per cent of the students who do not owe allegiance to this country, but facts ascertained by close investigation do no bear this out. They—the foreign element—were undoubtedly of the mob hurled on a peaceful citizenship from the gold-domed college, but they were not all of it. They were augmented and assisted and undoubtedly directed by religious fanatics who are citizens of the United States, but feel called upon to disgrace the flag of this free land just because it is given a place of honor in an organization they oppose.35

By trampling the flag and rioting against the Klan, Catholics proved that they showed no allegiance to nation. In the editor’s opinion, they were fanatics who possibly did not deserve the honor of citizenship.

Notre Dame students, then, showed their true colors in the riot: they did not support the peaceful nation, which provided “the foreign element” a home. According to the pamphlet, the students were not patriots. Moreover, the Klan impugned the faculty of Notre Dame, who supposedly did nothing to punish their students for the “outrage.” Wingfoot reported that the riot lasted a full day without response by the faculty “to stop thugs who were beating women and children, dishonoring the American flag and causing riot.” He also reported that the “gates” of Notre Dame had been locked down with no reason given.36 According to an eyewitness, the institution had not sufficiently punished the students for their malfeasance and their apparent lack of patriotism. The students had harmed innocent bystanders, including vulnerable women and children, and defiled the flag. Yet no action was taken. To add insult to Klan injury, Mayor Seebirt of South Bend requested the Klan “lower” its emblem from the order’s headquarters. A Klan officer rebutted that “the Knights of Columbus display their emblem at lodge halls . . . and that Roman Catholic churches display crosses.” According to the account, the mayor did not continue his request.37

Despite the uneventful end to the riot, various authors of the Klan pamphlet affirmed that the persecution did not end with these events. Rather, the press attempted to cover up the students’ actions in South Bend. According to the Fiery Cross, the reactions of the press made it more apparent to the residents of South Bend that the Klan stood for law and order. Residents witnessed the dramatic events of the riot and read local newspapers that “made an effort to gloss over the actions of the mob.” One “prominent business man” questioned whether the press could ever be trusted to fairly represent the Klan since the actions of the Notre Dame students were hidden.38 To show the prejudice of the local papers, the Klan paper pointed to an article on Edward Dinneen, a Notre Dame student who supposedly lost his life in the riot. The article placed the blame for the riot squarely on the shoulders of the order and claimed the students protected themselves and their university from the attack.39 The story was evidence of the press’s bias against the Klan and the distortion of the events to benefit Catholics. Klansmen were the victims in this event, but the press defended the unpatriotic Catholics. Even though the persecution continued, the Klan adamantly believed that they had won the war, even if they had lost this particular battle to the students.

According to the Night-Hawk, the riot led to a boon in applications in Indiana. The “state organization” was “clogged by applications from American citizens seeking membership in the Klan.” Additionally, the states nearest to Indiana also gained in membership applications. From the Klan’s perspective, the riot proved to be beneficial because it demonstrated to white Protestant Americans the real threat of Catholics and Catholicism to the nation. The riot, in some ways, proved that the church actively maligned the Klan and Protestants. The Klan, despite the beatings, flag trampling, and robe ripping, had won a significant battle against the enemies of Americanism who might have altered the face of its beloved nation. For Catholics, however, the order impugned the Americanism and dedicated patriotism of not only the Notre Dame students but also all Catholics. Both the Klan and the students interpreted the riot as a battle for Americanism, but each side believed they were defending national pride and culture.

There is no loyalty that is greater than the patriotism of a Notre Dame student.40

In the May 17, 1924, Notre Dame Daily, an editorial titled “Heads, Not Fists” reported that an “organization formed of men who do not think deeply nor well plans to parade in South Bend this evening.” The organization was obviously the Klan, and the Daily reported that Mayor Seebirt forbade the order to parade and beseeched “the Notre Dame men to remain at the university on that evening so possible trouble could be avoided.” Moreover, Seebirt confirmed that South Bend’s officials had the situation under control. The Daily warned Notre Dame students that ignoring the mayor’s request would only cause trouble. The editorial continued:

Some children need to be whipped, but the approved correction is an appeal to growing intellect. The approved correction is a means, not of administering bruises that surely pass with time, but of impressing mental blows that do not pass but remain to germinate. Tonight, we are sure, Notre Dame will give some shallow-minded ones an example of respect for the law. Tonight, Notre Dame men will use their heads and not their fists.41

The Daily reported that the students who planned to march against the mayor’s order would not provoke the Klan. Instead, they would provide a shining example to the order of how to be law-abiding. The president of Notre Dame, Father Matthew Walsh, also issued a bulletin on the Klan rally and parade, which was reprinted in the Daily on May

18. He noted that Notre Dame was “interested in the proposed meeting of the Klan,” but the university planned not to interfere. Interference in Klan events, according to Walsh, led the order to “flaunt its strength,” which “resulted in riotous situations, sometimes in the loss of life.” Walsh also acknowledged why Notre Dame students might feel the need to react to the order:

However aggravating the appearance of the Klan may be, remember that lawlessness begets lawlessness. Young blood and thoughtlessness may consider it a duty to show what a real American thinks of the Klan. There is only one duty that presents itself to Notre Dame men, under the circumstances, and that is to ignore whatever demonstration may take place today. . . . It is my wish that the Klan be ignored, as they deserve to be ignored, and that the students avoid any occasion coming into contact with our Klan brethren during their visit to South Bend.42

Unfortunately, some Notre Dame men did not heed the warning of Walsh to stay on campus. According to Todd Tucker’s account, curiosity motivated some Notre Dame students to disobey the directives of the president. The Klan gathering and parade could not be missed. For Tucker, the events began when Notre Dame students scared, attacked, and even disrobed Klansmen in alleys and on the streets. One student Tucker chronicled, William “Bill” Foohey, even had his picture taken in a tattered Klan robe. The fun quickly turned violent as Klansmen decided to arm themselves with handguns underneath their official costumes. Tucker noted that deputy sheriff John Cully, a Klansman, called the governor in hopes of mobilizing the Indiana National Guard.43

From that account, the students had caused a full retreat of timid Klansmen, and they began to gather at the Klan headquarters. Luckily for the students, the first floor of the headquarters housed a grocery, from which the creative students plucked potatoes and took aim at an electric fiery cross that was mounted atop the building. Tucker wrote:

The first potato shattered the third-floor window that shielded the cross, showering a few pedestrians with glass as they ran for shelter. A fusillade of potatoes followed. Each time one hit its target, a red bulb would burst with a pop and a shower of golden sparks. Occasionally, an angry-looking Klansman would peek out through a window, but a barrage [of potatoes] would quickly drive him back into the shadows. Soon, only the top bulb of the cross remained glowing. Throw after throw fell short. The men had exhausted their arms trying to hit the bulb, and their throws were becoming weaker and wilder. The remaining red bulb mocked them from above.

Eventually, Harry Stuhldreher, a Notre Dame quarterback, burst the final bulb.44 Some students decided to enter into the headquarters, and according to their accounts one Klansman confronted them with a gun. Tucker noted that priests from Notre Dame attempted to have the chief of police intervene in the riot, but he was dismissive of their concerns.45 Luckily, rain dampened the excitement of the day. Our Sunday Visitor, in agreement with the South Bend News-Times, noted that a “thunder shower” kept the violence at bay and made Sunday a day of rest.46 However, by Monday, May 19, Notre Dame and Klan forces again clashed in the streets.

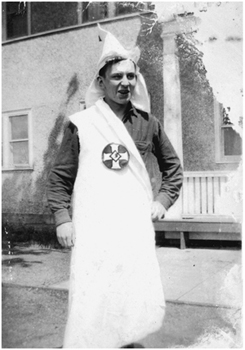

William “Bill” Foohey, a Notre Dame student, wears a stolen Klan robe in 1924. Courtesy of the University of Notre Dame Archives, Notre Dame, Indiana.

The News-Times reported that the rioting began again when the Klan hung a fiery cross from the window of its headquarters. Police stationed near the headquarters noticed “500 members of the anti-Klan forces began a march.” Faced with such a large presence of Klansmen and Notre Dame students, “policemen charged the crowd and wielded their clubs at random members of both factions.” In the process, the police clubbed some “innocent bystanders.” Fights broke out all over the city. Even “railroad detectives” were called in for reserve. The police force arrested both Klan and Notre Dame rioters, and members of both groups sustained injuries in the brawl. Catholic students claimed that they “were attacked with clubs, bottles and other weapons carried by men who wore white handkerchiefs as arm bands.”47 The order eventually removed the fiery cross, and the crowds dispersed somewhat. For the News-Times, the appearance of Father Walsh calmed the calamity. The Notre Dame president talked to the students in an attempt to hamper their tempers and soothe bruised bodies and egos. Walsh stated:

Whatever challenge may have been offered tonight to your patriotism, whatever insult may have been offered your religion, you can show your loyalty to Notre Dame and to South Bend by ignoring all threats. . . . If tonight there have been violations of the law, it is not the duty of you and your companions to search out the offenders. I know that in the midst of excitement you are swayed by emotions that impel you to answer the challenge with force. As I said in the statement issued last Saturday, a single injury to a Notre Dame student would be too great a price to pay for any deed or any program that concerned itself with antagonisms. . . . There is no loyalty that is greater than the patriotism of a Notre Dame student There is no conception of duty higher than that which a Notre Dame man holds for his religion or for his university.48

A 1924 news clipping reports that after the intercession of Rev. Matthew Walsh and athletic director Knute Rockne, Notre Dame students pledged to leave the Klan alone. Courtesy of the University of Notre Dame Archives, Notre Dame, Indiana.

Walsh’s measured statements affirmed the indignities that the students faced at the hands of Klansmen and the dismissal of their patriotism. He argued that it was not necessarily their fight to correct the ills of the Klan but rather to focus on their own loyalty and duty. Notre Dame men were patriotic, and they did not have to assault members of the order to prove their dedication to the nation or their local community. The News-Times did not comment on Walsh’s statement about the patriotism of the students but rather summarized the events of the three previous days, saying that the order had scheduled a Klan parade, students and Klansmen clashed in the streets, rain prohibited further rioting on Saturday, and Monday proved to be the day of most vigorous fighting. Finally, Walsh stepped in to save the day.49

What the accounts show is that the Notre Dame students were culpable. They did antagonize Klansmen, and Klansmen returned the favor. Both sides were involved in the street fights, and neither could really claim to be victims. The Klan narratives present wild-eyed college students attacking Protestants, and the Catholic version of events do not necessarily support the students’ actions. What started out as pranks led to destruction of personal and public property, injuries within both factions, and chaos in the streets of South Bend. The event was calamitous, to say the least. Patriotism was an issue for the Notre Dame students as much as it was for the Klan. For some, Notre Dame’s victorious football season in 1924 showcased that they had won the larger battle with the Klan and established their place in American culture.50

Walsh attempted to show the students that street fighting did not necessarily affirm their patriotism. Some students, however, believed their attacks on the Klan were retribution for the order’s degradation of Catholic loyalty to the nation. To Walsh, the KKK was not powerful enough to impugn the patriotism and duty of his students. Rioting did not legitimate the Catholic presence in South Bend or the nation. Despite Walsh’s sentiments, the events caused some members of the community to question further the Catholic university’s commitment to nationalism.

Walsh received letters decrying Notre Dame’s role in the riot. In a letter from Toledo, Ohio, J. E. Hutchison admitted that he was shocked to hear of the events that took place in South Bend and that previously he had admired the university in its educational efforts. However, the destruction of the flag by students swayed his opinion. He believed that the particular incident could have happened in a foreign country, but on American soil it was unbelievable. He ended his letter, “This Un-American demonstration has lost for Notre Dame University many ardent Protestant supporters in this section.”51 A letter from a self-proclaimed “Kluxer” noted that Walsh should “thank your lucky stars” that Klansmen were not as destructive as “your bunch of lawless Anarchist students.” If they were, the author wrote, Notre Dame might have been razed to the ground. For the Kluxer, Klansmen were law-abiding, as opposed to the “Anarchist Ruffians” of the university who had attacked him and showed obvious disregard for the law. The Kluxer explained that Walsh should start teaching patriotism to those Catholic students who “tore the American flag to bits.” He wrote:

I have heard the Knights of Columbus deny that they have took such an oath as has been circulated among the public, but after reading in history of the bloody murders during the French Revolution, and knowing conditions as they exist today under Catholic domination in South America, and seeing with my own eyes some of the things that the bunch of Mackerel Smacking Anarchists from Notre Dame did last Saturday, I can easily believe that every world of the K of C oath is true.52

For the Kluxer, the Notre Dame riot proved beneficial because more Americans would realize the present danger of the Catholic Church in America. The Klansman had his previous impressions of the church and the KC confirmed by the students’ actions. The Klan’s renderings of the events were palpable to some who might have already wanted to believe the worst about Catholics.

But Our Sunday Visitor did not take the matter lightly. It produced its own version of events, in which the Klan ignored pleas and requests to call off its parade. Klansmen, then, “assumed the places of regular traffic officers,” which led students to disrobe some members of the order. Most important, the claims of “flag desecration” by students concerned the weekly. The Visitor responded that desecration was “only an embellishment of fervid minds, which, in their pipe dreams, take every rebuff to the Klan as ‘an outrage of the flag.’”53 Such was an unfounded allegation created by the Klan. Notre Dame students were patriotic and loyal, and they did not destroy flags. By Tucker’s account, the students won the battle, showing Klansmen that Catholics were a force to be reckoned with when their patriotism was on the line.

We could go and raze Notre Dame University, but that is not what the Klan teaches.54

Accounts of the events on May 17, 18, and 19, 1924, vary widely. What is likely is that each contains some truth and a good amount of exaggeration. The Klan’s audacity to hold a gathering and parade in such close proximity to the university incensed Notre Dame students, and Klansmen believed that they were physically, spiritually, and intellectually beleaguered. What the riot most clearly highlighted was the Klan’s understanding of its worldview in one particular incident. The Klan envisioned a world in which Protestantism and nationalism needed defense from foreign ideas, religious movements, and races. The riot gave credence to that way of viewing the world. Catholics, who loathed the Klan’s faith and nation, attacked Protestants in the streets of South Bend. As students ripped robes off the bodies of Klansmen, Protestant theology was also trampled. The riots were an all-out religious war happening on native soil. White women, children, and flags faced indignities. All the ideals that the Klan held dear seemed fragile in that moment. The order’s print culture had warned of various threats, and they were actualized in the eyes of Klansmen and Klanswomen in the days of the riot. If the Klan was attacked, the nation was actually in peril. The order understood its members as the only real citizens because of their religious affiliation, their race, their commitment to patriotism, and their protection of gender roles. The street battle signaled the failing dominance of white Protestant men. In the tumult of the street battles, all of the order’s principles appeared to be harmed. The students besmirched patriotism, disgraced white womanhood, and accosted the faithful in the street brawls. The Klan’s worldview, in which a dedicated white Protestant citizenry populated and ruled the nation, appeared tenuous at best.

The physical manifestations of the order’s slogans, robes, flags, and the bodies of white women were molested. Vicious Catholic enemies tampered with the physicality of the Klan’s beliefs. Its anti-Catholicism, which appeared primarily in the printed word, gained justification because the students confirmed the order’s worst imaginings. The Notre Dame students became the foil of the Klan’s desires and fears in that historical moment. After the chaos passed, the Klan again imagined the nation as its members preferred to. Time and distance reaffirmed its worldview, and Klansmen and Klanswomen embraced their previous positioning. Members did not hate or fear Catholics. They definitely did not accost Notre Dame students with weapons. They faced persecution because of their beliefs and their proclaimed Protestant identity. Instead of reacting with hate, they responded with tolerance and love. Members did not attack the university for vengeance but returned to the gracious principles of the order. The Fiery Cross enumerated the order’s position:

Klansmen . . . are truly taught to obey the law, to love their fellowman regardless of what their fellowman may believe. The acts of the Klansmen showed naught but love. The tolerance displayed by misused Klansmen might well serve as a criterion for all Americans. Klansmen could have done that which the man quoted said they could have done [harm the university]. But they did not; did not in the face of the fact that as American citizens they had a perfect right to assemble as they did. Every law, moral and otherwise, had been broken in the attack against them, but, remembering their pledge to uphold the laws of America—which give those Roman Catholic students the right to worship as they please—they were not swayed by hatred; they were held steadfast to American principles and, in the face of demoniacal hate, exhibited naught but love.55

Love, not hate, was the defining feature of the order. Yet in the visceral renderings of the events of May 1924, the Klan appeared in its most intolerant form. Members’ anger at the Notre Dame students’ audacity to assault the order rang clear. Anti-Catholicism materialized through the eyewitness accounts of the riots as well as the “fake” Knights of Columbus oath. The order imagined the church and its faithful at their worst, and these particular events confirmed such.

The Klan accounts of the assaults were not personal but national. The assaults were larger than torn robes and slapped babies because they were acts of violence against the nation, the faith, and the race. The Knights of the KKK visualized themselves as quintessentially American. Thus, harm to the Knights was harm to the nation at large. Each Klansman was a symbol of the larger image of America. In the order’s imagining, America was a nation founded, fostered, and actively crafted in the hands of white Protestant men. The white-robed visages were symbols of that heritage. Destroyed robes signaled racial and religious intolerance as well as national peril. True 100 percent Americanism could only be found in the hearts, minds, and bodies of white, native-born Protestants. The Klan’s envisioning of beloved nation was exclusive and stark, so that African Americans, Jews, and especially Catholics could not really be citizens but only interlopers. They were hazards to body politic because of supposedly foreign ideas, religious movements, and the possibility of miscegenation. In foreign yet familiar hands, the nation would become heterogeneous, loathsome, and corrupt. American values and liberties would be decimated, and Liberty, the white goddess, would be tainted irreparably. The riot was a small representation of the larger battle, and the Klan had to win to guarantee the sanctity not only of the Indiana town but the whole of the nation.