biological factors

biological factors

psychological factors

psychological factors

external events

external events

NOW YOU HAVE an understanding of the different elements of OCD and the importance of meaning in driving the problem.

This chapter will build on this to help you think about:

biological factors

biological factors

psychological factors

psychological factors

external events

external events

The first chapter should have given you a clear idea of what are obsessions and compulsions and how to recognise them. It should also have begun to make sense of why obsessional thoughts cause so much anxiety and why people feel strongly compelled to perform compulsions, i.e. the central meaning given to the thoughts. The meaning is usually that having a particular thought:

We know that not everyone responds to their thoughts in this way and that, for many people, even the most violent and chilling thoughts can be easily ignored because they don’t carry the burden of meaning. This means that those who don’t have OCD typically treat their intrusive thoughts, images and doubts as mostly irrelevant. As a result, they do not respond in the ways which typically tend to keep OCD in place; that is, they don’t use compulsive behaviour, avoidance, thought suppression and all the other things motivated by fears of being responsible for harm. To continue the task of really getting inside this problem, this chapter will cover the reasons that some people may be more susceptible to such fears of being responsible for harm and therefore the negative interpretations of thoughts associated with OCD.

NO SIMPLE ANSWERS: THE VULNERABILITY–STRESS MODEL

Where do mental health problems come from? Put simply, it is reasonable to say that people experience psychological problems because things get to them in ways that they can’t manage and through no fault of their own. This simple truth can conceal another, as researchers ignore the complexity of human beings and their problems and try to pin down blame for problems such as OCD to genes, brain chemical imbalances or a troubled relationship with parents. Appealing though such simple explanations are, the less obvious truth is that the causes of psychological problems are complex and interlinked. There appear to be several different ways in which a person can end up suffering from a problem such as OCD and it is never simple.

Everybody has a combination of vulnerabilities and strengths (‘resilience’). Research and experience tells us that there are many types of biological, environmental and psychological factors that might be linked to why a person develops mental health problems. However, there are also things which can protect us from even the most severe circumstances. In other words, we all have our limits, and if pushed far enough anyone can and will experience severe and persistent mental health problems. How far we have to be pushed before ‘breaking down’, and the way in which such a ‘breakdown’ will affect us, will depend on several of these factors, some general, for example, how mentally ‘tough’ we are, how we seek support from those around us (or don’t), some specific, for example, our weak spots (‘Achilles heel’), our ways of coping when confronted by problems. And, of course, this will also relate to the type of pressure we find ourselves under and our past experience of such problems and dealing with them.

To complicate things further, some of these factors are thought to represent very general vulnerabilities to stress (such as how easily we become worried and how we physically react to stressful situations), while others may present specific risks linked to a particular problem, such as our sensitivity to particular types of worries. It goes on to become even more complicated; these factors will also vary depending on day-to-day issues, such as whether we are feeling run down, our reactions to recent events (such as bereavements, falling in love), our mood, having had too much coffee and feeling on edge and so on. Notice that these factors can go either way, making you more or less susceptible to problems. And of course, the reality is that there is always a complicated combination of factors involved in complicated ways. Happy events can increase our fears. For example, having a baby can, for most people, open up whole new worlds of joy and opportunity, but can also unleash a world of uncertainty and terror about things which can go wrong. For someone who is worried already, things going well becomes another source of worry, as the person realises how much they now have to lose!

This complicated pattern of factors has been described as the ‘vulnerability–stress’ model. The idea of a complicated interplay between how a person is ‘made’ and the things which happen to them is the accepted model of thinking about most physical and mental health problems. A combination of background factors including those related to genes, to social, psychological and biological factors and to past experience can make us more vulnerable to developing a problem in stressful circumstances. These factors may come into play in certain situations (such as external events), and the combination may then ‘tip’ us into the problem, which will be further affected by the way in which we try to ‘fight it off’ and the extent to which further events affect our ability to deal with the situation.

In reality, there is a lot of variation in the contribution of vulnerability and stress factors for individuals. It may be that one factor is particularly potent for one person, while for another it could be something completely different. The diagrams below illustrate this idea:

Are you a victim of your biology and genes? Some neuroscience researchers in the field of mental health have encouraged us to think of research on brain scans and similar findings as indicating that you are. This research is often described in terms of chemical imbalances in the brain, faulty brain circuitry, genetic defects and so on. However, people are often surprised to learn that the supposed genetic and other supposed vulnerabilities described in OCD are most likely to fall into the category of ‘non-specific’ risks for developing a disorder. An example of a non-specific risk would be the fact that women are twice as likely to be depressed as men. This does not mean, of course, that depression is caused by being a woman!

Yes, groups of people with OCD are sometimes found to have different patterns of brain activation when brain scans are carried out. However, it would be very weird if this were not true, given the way these studies are carried out. The brain scan is sensitive to different patterns of activity in the brain and can, for example, detect the difference in terms of the way the brain reacts between expert musicians listening to music and people with no special knowledge of music. It is therefore not surprising that there are brain activation differences between people with OCD and those without; they tend to have different patterns of worrying! This does not mean that OCD is a biological disease.

No true biological differences have been found between people with and without OCD, and those that have been identified are confused by the fact that having the disorder can lead to temporary changes in the brain, such as listening to music or thinking a happy thought. There is clearly no ‘OCD gene’, but certain genes have been implicated as vulnerability factors. These genes become relevant and ‘switched on’ in particular environments. This is true of all human behaviours, for example, having a genetic predisposition to being an amazing tree climber may not be relevant unless you live somewhere where you can climb trees regularly. We cannot do very much about the genetic hand which nature deals us, but we know that biology is only one aspect of vulnerability and that other factors (which can change) are necessary for a problem to develop. It is hard to estimate because the research findings are not clear, but probably less than 10% of what happens in OCD can be linked to genetic factors, and these factors are probably to do with being prone to anxiety; that is, ‘being a bit of a worrier’.

At the time of writing, there is no biological theory of OCD which helps us understand it in ways which could improve how it is treated.

PSYCHOLOGICAL VULNERABILITIES: THE SPECIAL ROLE OF RESPONSIBILITY

There is no doubt that OCD is a problem of thinking and how the sufferer reacts to their thoughts. We all have ‘silent’ beliefs about ourselves, how the world works, and our future; these are general attitudes which are based on our understanding of our place in the world, and are linked to the values by which we live our lives. These attitudes may not be something we are aware of most of the time and we may never even have thought much about them, but they are there and we act consistently with them. For example, if you are a person who has general attitudes about yourself that you are essentially good and competent, but one day your car breaks down and you lose your keys, you may think, ‘what a lot of bad luck!’ If you believe that you are in some way defective, you may conclude, ‘bad things always happen to me’. Returning to Beck’s cognitive model, he put forward the idea that the beliefs that a person holds about themselves and the world in general act like a lens through which they view what happens to them. They are the ‘unwritten rules’ of our life. It may be that specific events bring particular beliefs ‘online’ which were not previously relevant, for example, losing a job may bring to the front a person’s belief that they are worthless. They may never have thought about this before, as things have generally gone okay for them; the unwritten rules were never challenged.

We build up our set of beliefs through a combination of direct experience and what we are told about ourselves and the world, over our entire life. It is therefore very difficult to pinpoint where beliefs come from, and in reality they are usually assembled and developed from many different sources over many years. A number of beliefs are relevant to the experience of OCD. These include the need to be ‘perfect’, the need to be ‘in control’ and difficulties in tolerating uncertainty. One set of beliefs that has been consistently shown to be very important in OCD is the set concerning responsibility for harm. This is the idea that by doing something wrong, or failing to act, you may be responsible for causing a terrible and preventable outcome. The ‘terrible’ thing may be very individual, and may involve harm coming to you or someone you love, or a complete stranger. The key factor is that by your actions (what you do or what you fail to do) you will be in some way to blame if it were to happen.

We know that people with OCD have very broad shoulders where responsibility is concerned; that is, they feel very aware of responsibility, and it is very hard for someone like that to tolerate the idea that they could be even partly responsible for something awful happening and not do something about it. As with other beliefs, these ideas build up over time, but theorists suggest that particular early experiences may play a role for some people. One example of this is being expected to, or made to, take on a lot of actual responsibility, perhaps by caring for siblings or even adults. Similarly, ‘scapegoated’ children who are consistently blamed by parents/carers for negative consequences over which they actually have little control (e.g. ‘look what you’ve made me do now’) may take on a broad sense of responsibility.

You may have had to follow very rigid and extreme codes of conduct and duty leading you to conclude that there are very bad moral consequences to certain actions. Some overly strict religious upbringings can have this effect; for OCD a highly relevant example is the idea of ‘sin by thought’. See ‘Superstition and magical thinking’ here. Everyday things, like the dangers of not being clean, can sow the seeds for obsessional fears about contamination and washing.

Alternatively, you may have been overprotected and shielded from ever taking responsibility, perhaps by being told that the world is too dangerous a place and that you are not able to operate successfully in it without taking a lot of care. When it is your turn to take responsibility this can therefore become particularly frightening, leading you to be so careful that you behave … obsessionally.

On occasion particular incidents happen in childhood that can lead to the development of beliefs around responsibility. This may be one specific incident or a series of incidents in which something you did or did not do actually contributed to a serious misfortune. Believing oneself to be inadvertently capable of causing something terrible to happen can lead people to believe it is their responsibility to take extra care. Sometimes, unfortunate coincidences can lead people to conclusions about their responsibility in misfortunes, perhaps thinking ‘I wish you were dead’ about someone who then died soon after. Through a number of different experiences, or sometimes one key experience, people with OCD have commonly absorbed the idea that it is very important that they take particular care about their thoughts and actions. This is a subtle type of responsibility belief, where your own thoughts can cause and/or prevent harm, making you responsible for it.

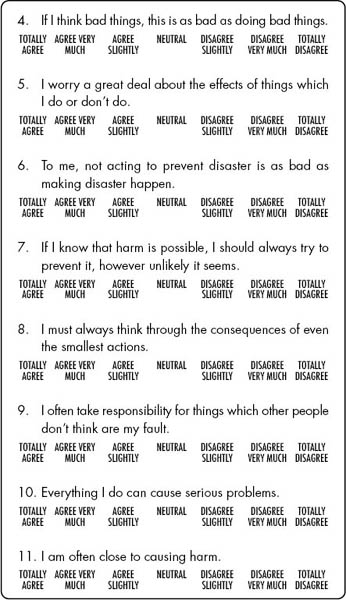

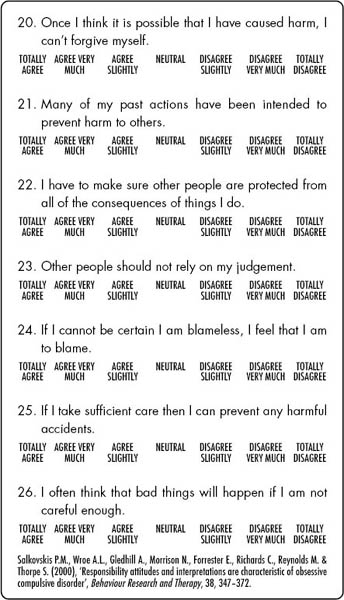

Below are some of the responsibility ideas that people commonly experience as part of OCD. The questionnaire asks you to think about how much you agree with the idea. There is no particular number of ‘agrees’ that indicates whether you have OCD; the purpose of the questionnaire is to get you thinking about whether you have inflated responsibility beliefs. This is a questionnaire that has been used extensively in clinical work and research. Try not to worry if you don’t understand every statement or you think it doesn’t apply to you – just move on to the next item.

OTHER PSYCHOLOGICAL VULNERABILITIES

Research has shown that ideas about responsibility are particularly important in the understanding of how OCD takes and keeps hold. However, other factors have been highlighted as playing a role for some people in their OCD.

PERFECTIONISM

Most people want to achieve what they can in life and there are a range of ways that we go about motivating ourselves to do better – two important aspects of our progress through life are choosing and setting the right goals and how we feel when we meet, or sometimes fail to meet, those goals. Most people drive themselves very hard to do ‘perfectly’ some things they regard as ‘important’, and therefore set very high standards in the belief that this will help them achieve the best. This is generally fine, when the high standards are like ambitions, something the person is happy if they achieve and not too much of a problem if they don’t. However, some people have perfectionistic standards for everything – not just the important piece of work that they are doing, but small things like how they carry out their everyday routines. What can then make it worse is if the perfectionistic standards are not a source of satisfaction, but instead a constant source of fear. Another problem with perfectionism is a type of ‘putting all your eggs in one basket’. That is, the person who believes that everything depends on getting things right in one area of their life (and therefore much of their behaviour is motivated by the fear of getting things wrong in that area).

Positive perfectionism is when we persist in things which are important to us, allowing ourselves to apply lower standards in other areas. We can enjoy the rewards of a good job done well, and easily tolerate the imperfect trivia. However, if we treat everything as equally important and try to do everything perfectly, we are doomed to a negatively motivated perfectionistic life of slavery linked to our blindly high standards, and may be tortured by our fears of things going wrong (meaning, things which are not perfect). In OCD, not getting things we believe we have a responsibility for ‘just right’ turns out to be at the centre of things.

When people don’t manage to meet the standards they set themselves, this might be a reason to try ever harder. Sometimes, however, the better response is to lower your standards so that they are achievable, and to choose carefully where we need to put our efforts. In summary, people who are vulnerable to experiencing a lot of psychological distress have particularly high standards about what they feel they should achieve and are motivated by fear of not meeting those standards rather than satisfaction if they do.

VIEWS OF OURSELVES AND SELF-CRITICISM

Important factors that can either protect us against difficulties, or may make us more vulnerable to them, is how we view ourselves and our ability to look after ourselves mentally when we encounter difficulties. Many of us can tend to be self-critical with the underlying view that this will help us get where we want to be and that not to be self-critical will somehow make us fail in our efforts. This self-critical message usually has its origins in childhood or early experiences and has been reinforced over time by being harsh towards yourself. However, over time the effect of this may be to make us feel less capable and may undermine our self-confidence in important ways. When you hear the crowd at a football match they will usually shout out supportive things for their own team. However, if a member of the opposing team comes near they will shout out lots of negative things. The purpose of this is to undermine that player’s confidence and make them play less well. So, if you are constantly criticising yourself and telling yourself that you are terrible, bad or stupid for making a mistake or doing compulsions, the overall effect of this will be that you will feel worse about yourself. This is likely to make the OCD seem more powerful. On the other side of the coin, if you take a more understanding and supportive approach to your problems, it may be that this will help you make more progress.

BELIEFS ABOUT THE IMPORTANCE OF THOUGHTS

As with other types of beliefs, those about the importance of thoughts are there, even if we have never spent any time considering them. If we believed that ‘thoughts don’t mean anything at all’ we would be less likely to be seriously troubled by a random intrusive thought. As we have discussed, people with OCD are very ‘tuned in’ to their thoughts and tend to make certain interpretations or assumptions about their thoughts, even if these are not articulated:

The esteemed psychologist Professor Stanley Jack Rachman, an expert in this area, gives some examples of attaching undue importance to the occurrence of intrusive thoughts:

It follows that if you have beliefs such as these about your thoughts, you will want to try to do something to have fewer of the thoughts in the first place, and will also try to do something about them once they have occurred.

TRIGGERING EVENTS AND CRITICAL INCIDENTS

If people have a number of underlying psychological and biological vulnerability factors, then for particular individuals an obsessional problem may start to develop when they encounter situations in life which bring these factors to the fore. In particular, situations which increase a person’s sense of responsibility, or decrease their sense of control over their environment, are often significant in bringing ideas of responsibility to the fore. This can happen gradually, for example gaining more and more responsibility in work, or the ongoing effect of being bullied at school, but it can also happen quite suddenly, for example leaving home or becoming a parent for the first time. Good things can make us more worried; we may begin to notice that we have a lot more to lose than we previously realised. As discussed in Chapter 1, the key factor is how the person responds to these events, and how the events interact with their underlying beliefs and general assumptions about themselves, how the world works in general and their possible futures.

For example, the birth of a child may lead to OCD in someone who believes that they should take every possible precaution to ensure that they do not cause, or risk, harm to those who cannot protect themselves. They may not previously have been exposed to such high levels of (very real) responsibility. Suddenly, when they ask themselves ‘What’s the worst thing that could happen?’, the answer seems very frightening.

Given the idiosyncratic nature of OCD, the particular triggering event, or events, can also be very individual. Common triggering events are changing school, other major life transitions like leaving home, losing a loved one, illness in yourself or someone important to you, having a baby, parental conflict, bullying, and relationship break-up. These events would, of course, be stressful for anyone, but for people who go on to develop OCD, there are often particular conclusions drawn at the time in relation to responsibility and the need to control what is happening. Sometimes there is no obvious triggering event, but a person experiences a worrying thought that they had never experienced or noticed before, and feels compelled to act. In either case, underlying responsibility beliefs play a role.

The development of contamination fears has always seemed easy to understand; after all, we are bombarded by ideas of how best to wash our hands, avoid infection and other health and safety messages. However, there is a further type of contamination fear which is much harder to understand: this is called ‘mental contamination’. In mental contamination, the person does not believe themselves to have picked up germs or poison, but feels inwardly polluted; dirty on the inside. Recently, one of the most important psychologists in the field, Professor Jack Rachman, pointed out the link between feelings of mental contamination and important formative experiences, particularly the experience of abuse and trauma from trusted people. He suggested that the experience of betrayal, a violation of trust by some person or organisation that we thought we could depend upon, can lead to feelings of mental contamination. It seems that we can feel contaminated and dirty because we have been treated like dirt when we were trusting. This feeling is dealt with by attempts to wash away the feeling; of course, because the feeling is inside, the washing fails.

OCD can creep in over a number of years or can develop quite suddenly. Sometimes it can get better if circumstances change, but can recur at a later point. There are many reasons why people may not seek help straight away but one of them is that the obsessions and compulsions may seem at first to be helpful. Who can argue that taking care and being responsible is not a good thing? Of course it is not the taking care that is the problem, it is the fact that it becomes out of proportion to the risks involved. This is particularly tricky if you begin to view yourself as a potential risk to others. As we said before, the driving mechanisms of OCD are understandable as extreme versions of normal psychological processes. It may take a while for the behaviours to become extreme and obviously unhelpful, and sometimes it can be hard to identify exactly where this line is (and of course there is no real line). It may take a while, too, to realise that what you are doing has become very out of step with the norm, particularly if you are very focused on your own behaviour. It is not uncommon for others who know the person well to notice this well ahead of the person themselves. It makes sense that if you feel that your compulsions or avoidance are keeping you and others safe, it may feel like you have no choice but to continue doing them, or that it is a price worth paying.

In some cases, the symptoms which later turn into OCD may even start off as comforting, a kind of false friend. Little rituals can be soothing when they remain within limits. For some people, washing or checking or putting things in particular order makes them feel more in control at first. Only when these rituals take over and dominate do things begin to become problematic; as we describe below, ‘the solution becomes the problem’.

Another aspect that can keep people suffering for a long time is not knowing what OCD is and how it works. If you have never heard of this problem or the fact that negative thoughts are normal and suddenly notice an intrusive thought or have an image of stabbing someone for example, it is very understandable that you might conclude that it means something terrible about you. Perhaps you may think that you may actually do it or that having the thought means you are going crazy. As well as causing a lot of anxiety, these types of interpretations may make you hesitant to seek help, and often it is the case that people struggle with such thoughts for a long time before finding out that these experiences are part of OCD. Shame and stigma can prevent you disclosing thoughts or symptoms even to your closest friends and family.

It is natural to want to understand how your problem developed. However, due to the fact that the problem may have been influenced by things you experienced long ago – before you could even make sense of them – and that there are many factors which can have an influence on OCD, it is important to bear in mind that there may be no definite answers. However, it can be helpful to think of things that might be relevant, as this will help you identify and understand particular ideas and behaviours that keep your problem going in the present. Think back to when symptoms of the problem began to emerge (it may have been long after this that you began to consider that they were actually part of a problem).

Was there anything when you were growing up that made you more prone to being concerned about bad things happening?

Think about experiences, or patterns of experiences, where you may have had too much responsibility or were given too little. You may have been overprotected by parents or perhaps had to care for them in certain ways. Perhaps you had a time where you felt that things were very out of control, for example being bullied, or your parents breaking up.

Did anything happen that made you particularly concerned about taking risks or worry more about bad things happening?

Did you have any experiences that seemed to mean that you were capable of causing or preventing harm?

What ideas do you think you absorbed about harm and your role to prevent it?

What ideas did you internalise about what sort of person you are?

There is no one reason or set of reasons for developing OCD and we are each unique in our personality, our biological make-up and the set of experiences we have had. Therefore it is usually very hard to pinpoint the exact reasons why any one person develops a problem. Luckily it is not essential to know this in order to beat the problem, although it does no harm to spend a little time thinking about how we got to where we are with a problem like this. Nevertheless, it is much more important to focus on the ‘here and now’ and what is keeping the problem going at the moment. Although we may not know exactly what ‘caused them’, we know that currently held beliefs about responsibility and about the world in general help us understand why people find it hard to ignore, or dismiss, negative thoughts. The next chapter will help you understand how OCD takes hold and keeps hold.