IN THIS CHAPTER we will cover:

Have you ever gone back to check that the gas is off, or thought that something is invisibly dirty or contaminated and taken extra care to clean it, or even thrown it away? Do you feel uncomfortable if your things aren’t arranged in a very particular way? Have you ever had a thought that you might do something terrible and out of character? Have you had a thought or mental picture about something you think you should never think about? Ever noticed what seemed like an impulse to do something you don’t really want to? Or had a ‘bad’ thought that you needed to cancel out in some way? These are all intrusive thoughts, meaning thoughts which pop into your head and interrupt what you are already thinking … they intrude! If they intrude so often and so strongly that they severely interfere with what you want to do, then you can be said to be suffering from obsessions and compulsions as a disorder: obsessive–compulsive disorder.

OCD has been increasingly mentioned in the media over the last few years, but not always correctly. Many people will have heard about the most common forms of the problem, affecting those who compulsively wash their hands or check things repeatedly, although there are many other types. However, precisely what drives people to get stuck in these patterns of thinking and behaving is not usually talked about, leading to misunderstanding of what the problem is. As a result, OCD can be offered as an explanation for almost anything which is repeated, from preferences for routine and order to the experience of everyday worries, or the motivation behind almost any ‘quirky’ behaviour which a person does more than once. Using everyday terminology, people with a strong interest are described as being ‘obsessed’ with it; people who are very focused are sometimes referred to as being ‘obsessive’. Being strongly interested in something, or being perfectionistic and persistent about something important to you can be helpful in the right circumstances and may be enjoyable if these things happen by willing choice. However, truly obsessional behaviour is very different in that it is driven by personally unpleasant ideas linked to an uncomfortable or even unbearable feeling of anxiety, and stands apart from other kinds of ‘obsessions’ and compulsions in being neither helpful nor enjoyable. The person suffering from OCD does not feel that they have any choice about what is happening to them. However, we will show that the processes which drive OCD are all understandable as exaggerated versions of normal psychological experiences and worries which take hold and develop into OCD in certain people.

Sometimes, when seen from the outside, the problem of OCD can seem extreme, bizarre and so far from ‘normality’ as to appear ‘mad’; this is, of course, one of the factors which stops people seeing the disorder for what it is and getting the right knowledge to fight the problem effectively. Unfortunately, this can also have the effect of cutting them off from seeking help (because they feel ashamed, scared or frightened of what will happen if they tell others). If you have OCD you may think of the problem as one of ‘mad, bad or dangerous to know’, all ideas that can fill you with some combination of shame, terror and misery. OCD is none of these things, and understanding how OCD works is an intrinsic part of moving through treatment and beating the problem so you can reclaim your life. Another factor which can interfere with how a person deals with OCD is when the problem becomes so completely consuming that the person loses their perspective. In this case, all you can think about is how to make sure that the things you fear do not happen. You become so taken up with what you are trying to do by washing, checking and other rituals that you are unable to see that your problem is fear of the thing which you are focused on, rather than the thing itself.

So, when people have OCD, the three most obvious elements of the way they experience it are:

Obsessions, also known as ‘intrusive thoughts’, are unwanted and unacceptable thoughts that seem to appear in your mind in an unbidden way. Obsessions can be thoughts in words but can also be images; urges, as if one wants to do something, or feelings of doubt. We will refer to them as ‘thoughts’ for clarity of writing from this point. Everyone has had the experience of a song coming into their head that stays around all day; when walking down the street many people experience nonsense phrases or perhaps swear words popping into their head. Unlike other thoughts that pass through our minds, obsessive thoughts are experienced as any or all of repugnant, senseless, unacceptable; they are always difficult to dismiss or ignore. Obsessional thoughts, therefore, seem to stand out from other sorts of thoughts because they are alien to the way we see ourselves. That is, they don’t fit with who we think we are (but often people with OCD fear that they might reveal some terrible truth about themselves).

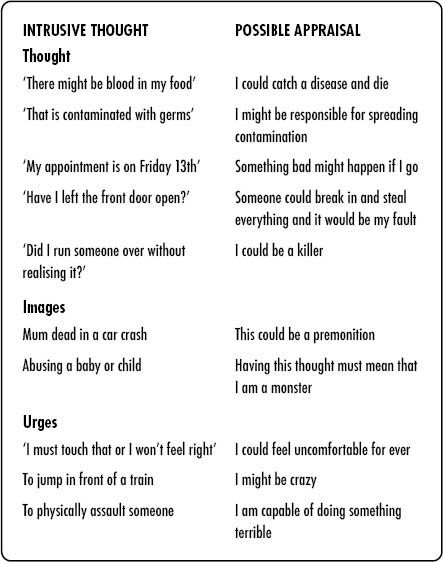

It would be impossible to list all the possible intrusive thoughts people could have as they are so many and varied. Here are some common intrusive thoughts, images and urges that we will revisit throughout the book:

THOUGHTS

DOUBTS

IMAGES

URGES

Looking at the list above, if you are someone who knows or thinks that they have OCD, you may have spotted a thought similar to one that particularly bothers you. There are probably others in the list that don’t bother you, but would certainly be troublesome to someone else. Surprising as it may seem, there are people who may have had any one of the thoughts listed above, but are not particularly worried by them and certainly do not have OCD. In fact, everyone has thoughts such as these. Often people are surprised to find out that everyone has all sorts of intrusive thoughts – including the nasty ones: thoughts of harm coming to people, images of violence, urges to check things, doubts about whether they have done something or impulses to do something they consider ‘terrible’. For most people the thoughts just flicker in and out of their mind without causing the levels of distress seen in OCD.

In the 1970s, when the cognitive understanding of OCD was being developed, two experts in OCD thought it was important to know whether ‘normal’ people had intrusive thoughts, and whether they were different in content from those that troubled people with OCD. They asked people with and without OCD to write down their intrusive thoughts and they mixed up the list. They then asked professionals with experience in working with OCD to say which had come from people with OCD and which had not. They were not able to tell the difference between normal intrusive thoughts and obsessional intrusive thoughts. Normal intrusive thoughts included:

Rachman, S. & De Silva, P. (1978), ‘Normal and Abnormal Obsessions’, Behaviour Research and Therapy, 16, 233–248.

The notion that ‘intrusive thoughts’ are everyday occurrences was backed up by research conducted in the late 1970s and 1980s which investigated whether there were differences between the thoughts of people with OCD and these ‘normal’ intrusive thoughts. The intrusive thoughts that people who did not have OCD (or other problems) disclosed concerned impulses to hurt and abuse others, images of harm and thoughts that things were wrong or could go wrong. The content of the thoughts that others just had very fleetingly was remarkably similar to the thoughts that troubled people with OCD. The fact that ‘normal’ people experience all sorts of negative ‘intrusive thoughts’ is a very important fact to remember.

Although we now know that negative and unacceptable intrusive thoughts are normal, clearly some people are much more troubled by them than others. Some people are so disturbed by their intrusive thoughts that, understandably, they would like to stop thinking them altogether. If only there was a way not to think about things being contaminated, or to block out the horrific and unwanted thoughts of violence, then surely the problem would be solved? This might seem like an attractive idea, but is it a realistic solution? What happens if you try? It has been known for many years now that the harder you try to get rid of an idea the more you will be troubled by it … until you stop trying! As discussed later in this book, this is an example of the solution becoming the problem. The harder you try to get rid of your thoughts, the more important you are making them seem and the deeper the ‘groove’ they wear in your thinking patterns.

The reason you can’t control your intrusive thoughts in this way is probably because you are not meant to! Our brain is designed as a super-efficient problem-solving machine which is flexible enough to adapt to unexpected situations. A really important thing in unexpected situations is to be able to free your thinking to come up with loads of different ways of tackling things, and to do that quickly. Probably for that reason, our brains tend to interrupt what we are doing with multiple ideas that might be relevant to what’s going on. That’s what intrusive thoughts are; a mishmash of things which spring to mind, especially when we are in an emotional (that is, important) situation. When it seems like we are in danger, our quick-fire mind gives us as many options as possible … run away, climb a tree, fight, do nothing and so on. A lot of the options are irrelevant, stupid and dangerous, but the point is that our mind delivers as many of these as possible as quickly as possible. It is then up to the rational bit of us to choose which option to go for. What this means is that we can’t control intrusive thoughts, but it is entirely within our control to respond or not respond to them as we think best. The ones we do things about will tend to stick around and are more likely to come back later. Unfortunately, this might include the thoughts we struggled to get rid of, or that we acted on defensively (for example by checking, washing our hands, or avoiding something). So attempts to defend ourselves against the intrusions keep us worried about them.

What this means is that if you could control some thoughts, you would have to do it by controlling all of your thoughts, to ensure that this was going to be effective. Funnily enough, this might have already happened in a particularly nasty way if you have OCD. Because the obsessions (and fighting them) have taken up so much of your attention, you may not have spent much time considering and noticing the other thoughts you have. Also, you may have given up thinking about some of the better things that might otherwise have been running round your head. So think back over the last few hours, or if you have just woken up, over the previous day. What kinds of thoughts have been going through your mind? Perhaps you had some thoughts about boring, tedious things you had to do, like the washing-up, or remembering to pay a bill? Did you have some positive thoughts about something nice you did in the past, or something you were looking forward to? Did you worry about anything, or did something upset you? Most likely you had thoughts in all of these categories. The point is that we have thoughts and images going through our mind much of the time. Sometimes, and in fact most of the time, thoughts such as these just ‘pop’ into our mind without us being aware of any ‘chain of thought’. We might have a brilliant creative idea in this way, or suddenly remember to our horror that it was our turn to pick the children up from school an hour ago! This sort of ‘intrusive’ thought can be very useful indeed. Usually people can think of an occasion when they suddenly had a thought that was helpful, such as remembering a friend’s birthday is coming up, or having a memory of a lovely holiday pop into their head.

Our everyday intrusive thoughts are generally not linear, ordered or controlled and that is a very good thing. Imagine what life would be like if they were and we had to plan everything we thought (if that was possible). There would be no creativity, no inspiration and no doing things on the spur of the moment and it would be a strange, dull and inhuman world. What this really means is that getting rid of the thoughts isn’t a realistic, or even desirable, goal. Thoughts come and go, and are as important as we make them. Think of it as like a huge self-service cafeteria you are walking through with a tray. So many different things come to your attention. Oh yuk! There is the food which makes you sick. Would it be a good idea to focus on how much you don’t want to take it? Or should you just accept that it’s there and see what else is on offer? If you do, you can take that and tuck into your preferred choice. Pretty soon, the nasty smell will have faded from memory and you can carry on dealing with what you want, rather than being preoccupied with something which you can’t stand.

So we know that ‘intrusive thoughts’ are entirely normal and may actually be helpful. Therefore having the thoughts themselves is not the problem. Simply stopping thinking the thoughts is an impossible goal.

So, if it is ‘normal’ and common to experience thoughts which are both unbidden and negative we need to look a bit further to understand why, for some people, having these thoughts is particularly worrying.

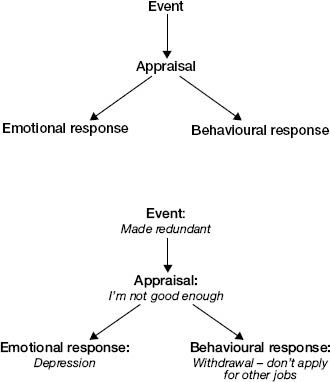

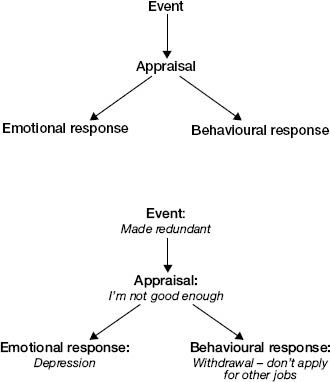

THE ‘COGNITIVE THEORY’ OF EMOTION AND EMOTIONAL PROBLEMS

Cognitive theories and cognitive therapy were devised by Professor Aaron ‘Tim’ Beck, originally a psychoanalyst, who found he was bothered by two things as he tried to make the theories devised by Sigmund Freud work. Firstly, it seemed to Beck that psychoanalysis did not work when it was used to try to help patients. Secondly, the theory of emotions that psychoanalysis laid out also did not work when it was researched properly. At first Beck just found this confusing, but subsequently he used his findings to develop a cognitive theory of emotion and emotional disorders. He went on to apply this more specifically to develop a cognitive theory of depression, which provided the cornerstone for subsequent work in the cognitive understanding of many other problems, and the treatments that have proved so successful.

‘Cognition’ is another word for thoughts and meanings, so the cognitive theory was a theory of the role that thinking plays in a problem. In summary, Beck’s theory stated that people did not become upset, anxious, sad or angry because of what happened to them, but instead by what they thought it meant (the way in which they interpreted it).

For example, imagine you were alone in the house and woke up in the middle of the night thinking you had heard a noise in the next room. If you thought it was an intruder, you would probably be frightened. However, when you then heard another noise (‘miaow!’) you would feel much better because you realised that it was not an intruder but your cat. This very simple example illustrates not only the way that negative thinking can make us needlessly anxious, but also the fact that changing our thinking (by finding out what is really happening in a particular situation) can help us feel quite differently.

So, Tim Beck showed us that depression was not caused directly by what happened to people, but by the interpretation given to those events. Furthermore, he suggested that how people saw and interpreted what happened to them was connected to their beliefs about themselves, about the world in general and also their beliefs about the future. People tend to think in a particular way because of past experiences which influenced what they believed about themselves and the world. For example, someone may have learned that ‘the world is a dangerous place and you should trust no one’. Although this belief might seem to keep them safe, it would also have the effect of making them overly cautious and distrustful. The theory also suggests that this kind of belief can have the effect of changing the way the person experiences things. For example, it might result in the person being on the lookout for bad things happening and people not being trustworthy, so they did not notice when good things happened and people were helpful and reliable.

Thus, this theory went a long way in explaining why certain events affect some people more than others. For example, a person who has lost their job (the event) interprets it as ‘I’m useless and inadequate and will never be able to keep a job’. This not only makes them feel sad, but means that they stop trying to get another job and withdraw to bed for days on end. However, another person may think ‘This job didn’t suit me; this is an opportunity to try something new’. They may feel slightly sad and a bit apprehensive about what a new job might be like (and how easy it would be to get one) but they would feel motivated to set in motion what they need to do in order to get a new job.

The same thing has happened to them, but these two people feel and behave very differently. The important point is that the response to any event hinges on the particular appraisal or meaning given to it by an individual.

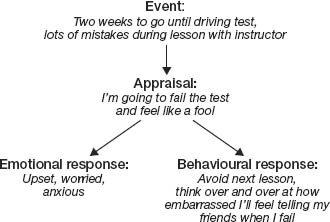

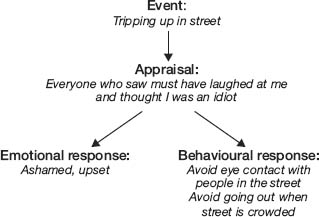

Let’s consider some further examples when the appraisal of an event affects what emotion someone feels and what they do.

By avoiding the lesson, they actually increase their chances of failing – a counterproductive course of action.

By withdrawing, the person does not get the chance to find out what really happens when you trip in the street – that people either don’t notice, or are sympathetic.

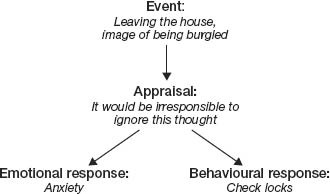

When this theory is applied to OCD, the event in question is not something in the outside world, but it is the mental event, i.e. the intrusive thought/urge/doubt/image or impulse itself. We know that intrusive thoughts are normal and very common, so the difference between someone who is bothered by a thought and someone who is not lies in what they make of having the thought. This ‘appraisal’ is what the intrusive thought seems to them to mean, for example, ‘Having this thought means that I am a bad person’. It is important to note that it is not the case that negative intrusive thoughts never bother people who do not have OCD. For example, having an image of someone you love coming to harm, or a doubt as to whether you turned off the oven, would be experienced as uncomfortable to some extent for the majority of people. However, most people would consider these to be ‘just one of those odd thoughts’ and they would not spend any time thinking about why they had this thought, or consider having it as an urgent sign that they must act to undo or prevent harm. When a person has OCD, having the thought itself is often interpreted as being particularly significant and it is this significance which both drives the emotional response (such as anxiety, shame, misery) and motivates the need to do something about it (behavioural response).

Using our examples of intrusive thoughts, possible appraisals that could lead to significant anxiety are given below.

These are, of course, just examples; sometimes the meaning of a person’s thought is unique to them. In general, the meaning always concerns something negative or unsafe about the person themselves or the world in general and it is this which causes such anxiety. The meaning is also linked to the person’s values, and significance is given to thoughts which appear to contradict them. For example, the gentle person who has violent thoughts would find these more upsetting than the thug, and the religious person experiencing blasphemous thoughts would find these much more problematic than an atheist. We will discuss this further in Chapter 2.

It is the personal meaning of the thoughts that makes them so unpleasant, anxiety-provoking and difficult to dismiss.

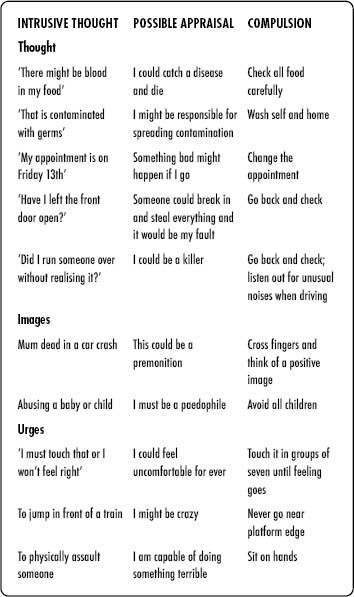

Compulsions (also called neutralising or safety-seeking behaviours) are the physical or mental actions and reactions that follow from intrusive thoughts or obsessions, and which are motivated by the meaning which the intrusion has for them. There are two main types of compulsions, which are best understood in terms of what the person is trying to do. One is to verify (to check, to make sure of) something, most commonly by physical or mental checking. The idea is that if you verify things, you can either feel completely sure that it is okay, or put it right if it is not. The second type of compulsion, restitution, is where the person aims to put right, make amends or correct something they think has already happened, for example by cleaning something thoroughly which they regard as contaminated, or by thinking a positive thought after having a negative thought they regard as dangerous.

People typically carry out compulsions for two important reasons: firstly, to try to prevent the harm for which they fear they might be responsible from happening, and secondly to reduce their levels of discomfort (anxiety, shame, sadness, anger). As such, the compulsions make sense as a response motivated by how a person has interpreted the obsessions. For example, if you are very worried about making yourself or others ill by contaminating them with something you have on your hands or body, it makes sense to do a lot of cleaning and washing. If you feel anxious that something may happen to a loved one, you do everything you can to make sure it doesn’t happen. In addition to the (sometimes, but not always) anxiety-reducing effect of that, you may have found that going through a ritual relieves or soothes this anxiety for a short time, sometimes by taking your mind away from the main worry. Although it is understandable why people suffering from OCD do rituals in this way (including seeking reassurance from others), in the longer term the effect is to increase worry, preoccupation and anxiety. It is a bit like using a drug; it may make you feel better immediately, but you pay for your relief in the longer term by needing to ritualise and avoid more and more.

Compulsions at their most obvious can be physical actions which would be visible to someone else present (known as overt compulsions) or behaviours that go on in your own head (known as covert compulsions), such as checking your memory, saying a prayer or ‘good word’ after thinking something ‘bad’, and even internally arguing with oneself. It is also possible, and very common, to undertake more than one compulsion in response to a particular obsessional thought. There are also a number of other possible reactions to having obsessions such as avoidance of particular people, places or activities or trying to push the thoughts away (these will be discussed in much more detail later). Common compulsions and the obsessions and appraisals that they are often related to are shown below.

The final element in understanding OCD is the interference caused by the problem. Interference seems too mild a word for the havoc wreaked by this problem. The negative appraisals in OCD invariably cause anxiety (often escalating into sheer terror) but can also be linked with other negative emotions such as shame, depression, disgust and anger. The anxiety is significant, that is, it tends to last for a long time and comes back after a short while. Continuously or repeatedly feeling anxious is very unpleasant in itself. Feeling unsafe and anxious can also affect your sleep and appetite and can cause you to become irritable with those around you. If you perform compulsions to try to manage these feelings or to stop bad things happening, it is likely that the urge to do this does not always come at a ‘convenient’ time. Most people with OCD find that they begin to prioritise their rituals and compulsions over other things and may find that doing compulsions takes up increasing amounts of time. This then has a knock-on effect on other things. Often this means being late for activities and appointments, or avoiding particular places or situations to try to avoid the stress and anxiety from having negative thoughts or doing compulsions. You may be missing out on certain social activities, or may avoid taking on more challenging jobs due to obsessions and compulsions. People can spend vast amounts of money they can’t afford on cleaning and washing products or getting rid of things that seem to them marred, spoiled or contaminated. Sometimes people go to great lengths, even moving house or country to try to get away from ‘contamination’.

Friends and families are often very concerned about a loved one who is caught up in rituals and obsessions. It can be heartbreaking to see someone in states of high distress, and it may be very difficult for you to explain what is happening if you are not sure yourself or if you are experiencing a great deal of shame about your difficulties. If you are doing a lot of compulsions such as cleaning, it may be difficult for those who live with you to follow the same rules or live up to the same standards as, if they do not have an obsessional problem, they probably do not share the same underlying beliefs or concerns. Following your rules may be stressful for you and for them, and this issue often causes conflicts within families. We will talk more about this and how to tackle it in Chapter 8.

Although some people with obsessive–compulsive disorder are able to continue to work and have a social life, others find that they have no choice but to give up most other things, de facto becoming full-time OCDers. OCD tends to creep into more and more areas of your life, taking it over.

Compulsions make sense as a response to the interpretation of obsessions. However, they are likely to have an increasingly negative impact on you and those around you.

SELF-ASSESSMENT SECTION: SO DO I HAVE OCD?

Below are some of the symptoms people commonly experience as part of OCD. As you will see, the items describe thoughts and behaviours in a quite general way. This is because the specific content of worries and particular behaviours can be very individual. The questionnaire asks you to think about how much distress the particular symptom is causing you. There is no particular number that indicates whether you have OCD, as some people will be bothered by many of the things listed below, while others will be bothered by only a few. The purpose of the questionnaire is to get you thinking not just about whether you have obsessions or compulsions but about the degree to which you are bothered by these types of symptoms. This is a questionnaire that has been used extensively in clinical work and research. Try not to worry if you don’t understand every statement or you think it doesn’t apply to you – just move on to the next item.

OBSESSIVE–COMPULSIVE INVENTORY

The following statements refer to experiences which many people have in their everyday lives. In the column labelled DISTRESS, please circle the number that best describes how much that experience has distressed or bothered you during the past month. The numbers in this column refer to the following labels:

DISTRESS |

|

0 = Not at all 1 = A little 2 = Moderately 3 = A lot 4 = Extremely |

|

1. Unpleasant thoughts come into my mind against my will and I cannot get rid of them. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

2. I think contact with bodily secretions (perspiration, saliva, blood, urine, etc) may contaminate my clothes or somehow harm me. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

3. I ask people to repeat things to me several times, even though I understood them the first time. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

4. I wash and clean obsessively. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

5. I have to review mentally past events, conversations and actions to make sure that I didn’t do something wrong. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

6. I have saved up so many things that they get in the way. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

7. I check things more often than necessary. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

8. I avoid using public toilets because I am afraid of disease or contamination. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

9. I repeatedly check doors, windows, drawers, etc. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

10. I repeatedly check gas and water taps and light switches after turning them off. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

11. I collect things I don’t need. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

12. I have thoughts of having hurt someone without knowing it. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

13. I have thoughts that I might want to harm myself or others. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

14. I get upset if objects are not arranged properly. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

15. I feel obliged to follow a particular order in dressing, undressing and washing myself. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

16. I feel compelled to count while I am doing things. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

17. I am afraid of impulsively doing embarrassing or harmful things. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

18. I need to pray to cancel bad thoughts or feelings. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

19. I keep on checking forms or other things I have written. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

20. I get upset at the sight of knives, scissors and other sharp objects in case I lose control with them. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

21. I am excessively concerned about cleanliness. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

22. I find it difficult to touch an object when I know it has been touched by strangers or certain people. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

23. I need things to be arranged in a particular order. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

24. I get behind in my work because I repeat things over and over again. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

25. I feel I have to repeat certain numbers. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

26. After doing something carefully, I still have the impression I have not finished it. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

27. I find it difficult to touch garbage or dirty things. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

28. I find it difficult to control my own thoughts. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

29. I have to do things over and over again until it feels right. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

30. I am upset by unpleasant thoughts that come into my mind against my will. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

31. Before going to sleep I have to do certain things in a certain way. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

32. I go back to places to make sure that I have not harmed anyone. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

33. I frequently get nasty thoughts and have difficulty in getting rid of them. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

34. I avoid throwing things away because I am afraid I might need them later. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

35. I get upset if others change the way I have arranged my things. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

36. I feel that I must repeat certain words or phrases in my mind in order to wipe out bad thoughts, feelings or actions. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

37. After I have done things, I have persistent doubts about whether I really did them. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

38. I sometimes have to wash or clean myself simply because I feel contaminated. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

39. I feel that there are good and bad numbers. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

40. I repeatedly check anything which might cause a fire. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

41. Even when I do something very carefully I feel that it is not quite right. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

42. I wash my hands more often or longer than necessary. |

0 1 2 3 4 |

Foa E., Kozak M., Salkovskis, P., Coles M., Amir N. (1998), ‘The validation of a new obsessive-compulsive disorder scale: The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory’, Psychological Assessment, 10(3), 206–214.

MY PROBLEM DOESN’T FIT: I DON’T HAVE COMPULSIONS

Sometimes people are acutely aware that they have unpleasant obsessional thoughts, but do not feel that they have any compulsions. This may be the case, and you may be continuing your life despite having lots of obsessions. Sometimes people say that although they are not performing obvious compulsions in terms of what they do, the quality of their life is affected by the torment caused by their obsessions. Compulsions are in fact always there, but they can be hidden. In some cases the compulsions are very subtle and may be more related to avoiding particular activities. In others the compulsions are all internal (often referred to as ‘neutralising’), including not only mental checking by going over things in your mind and restitution in which you try to ‘put things right’ in your head (by thinking a good thought to balance a bad one, for example) but also things like mental arguing (trying to convince yourself that there is nothing to worry about, a type of self-reassurance seeking) or by directly seeking reassurance from those around you. Whether your compulsions are external, like washing or checking, or internal, like neutralising, it is still obsessive–compulsive disorder.

MY PROBLEM DOESN’T FIT: I DON’T HAVE OBSESSIONS

It is also the case that people find it hard to describe the particular thoughts related to their compulsions. For example, if you are very used to washing your hands in a ritualistic manner, then you may do this each time whether or not you have a particular thought. However, it is likely that when it originally developed, the behaviour was a response to a thought and has, with the passage of time, become more like a habit that is done automatically. One way of thinking about this is if you drive a car (or if not, when crossing the road as a pedestrian), you probably stop at red traffic lights quite habitually. How often do you think about why you stop, or the consequences of not stopping when you approach a red light? Most people do not think about it at all, but of course the reason you do stop is to avoid an accident when cars or people are crossing the road ahead of you. If your brakes were to fail when you were approaching a red light, the underlying reasons for stopping will come flooding back quickly and vividly!

For those people with no obvious obsessional thought, the fact that you are continuing to do your rituals or compulsions, even though there is a cost to you in terms of time taken up, interference with your life and distress, suggests that there is an underlying reason that is preventing you just giving them up, and that underlying reason will be a submerged and invisible obsessional thought which you have stopped being aware of, in the same way that you have stopped being aware of why you stop at a red traffic light. The only way to find out what this is is to conduct your own ‘experiment’, where you actively try to stop doing the ritual or compulsion. This is, of course, very hard to do, and it might be a good idea to seek support from someone close to you when you try to do it. This also has the advantage of giving you someone to talk to about it when you have tried this experiment. Some people reading this book might not have told anyone at all about their problem. Although understandable, perhaps this is now the time to open up to someone you trust, so that you can get the support that you need to help you change.

Usually the obsessional thoughts related to the compulsions come to the forefront of a person’s mind when they do this ‘finding out’ exercise (i.e. when you try to actively stop doing the compulsion). You might also consider whether what is going on is happening as a mental image (a picture), impulse or urge, or a doubt about something you consider important. However, this is not always the case and you should not worry if it is hard to identify clear obsessional thoughts. For a small number of people, the obsessional thoughts have faded away to nothing, leaving the compulsion as a habit. If this is the case, then you can simply phase out the compulsion.

When it takes hold, OCD can affect many areas in a person’s life. However, it doesn’t always start like that. For some, the OCD takes the disguise of a friend, promising to keep you safe … but at a very high cost! And as time goes on, that cost escalates and keeps on rising. It can affect your well-being in a general way if you are constantly feeling anxious and can also have a direct impact on what you feel you can do and where you feel you can go. In many cases it can have an impact on relationships with other people, as they are repeatedly asked for reassurance or won’t follow your obsessional rules. It is worth asking yourself what is the real cost of your problem. Do the obsessions or compulsions take a lot of your time? Do they get in the way of your plans to do other things? Have family members complained? Are you frequently late? Are you suffering from physical problems such as rashes or dry skin? Are you spending a lot of money on replacing contaminated things or buying cleaning products? Perhaps you have decided not to take on a more challenging role or course, as these would be hard to manage around your obsessions or compulsions. You may even have decided not to have a relationship or not to have children due to fears and worries related to OCD.

Think about all of these areas and note whether and how the problem is affecting each one:

If the descriptions of obsessions and compulsions fit with things that you are thinking and doing, it is possible that you may have OCD at some level. The clinical diagnosis of OCD is given when people have either obsessions or compulsions that significantly interfere with their lives, and it is the level of interference which is key. Usually this means that people are particularly troubled, or are spending a lot of time on their obsessions and compulsions. However, many people have symptoms of OCD at a lower level which can still cause some interference and inconvenience. The symptoms may increase if their circumstances change and they experience more stresses in their lives. We know that many people coming to treatment wait for a long time until things get really bad before seeking help, with one study identifying an average wait of 11 years. Understanding the nature of OCD can help prevent the problem growing and as you will see, you can use the techniques in this book even if you have low levels of the problem or if you have recovered

If OCD is causing significant interference in your life it is important to acknowledge this reality. Even if this is difficult, it is the springboard for thinking about why it’s so important to change, and for imagining how you would like your life to be without this problem. We will return to this at the end of Chapter 3 when we ask you to identify your goals.

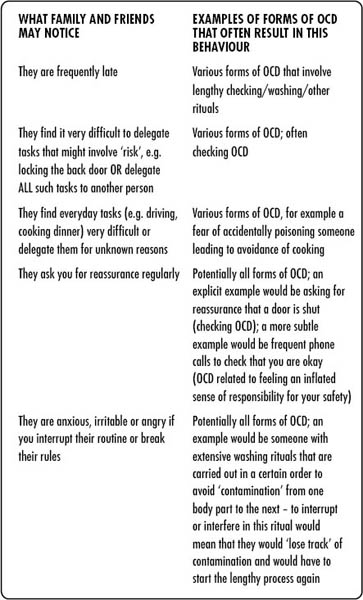

HOW DO YOU KNOW IF YOUR FRIEND OR FAMILY MEMBER HAS OCD?

You may be reading this book because you are concerned about a friend or family member and suspect that their behaviour could mean that they have OCD. It is often the case that family and friends are aware of the anxiety, distress and impairment caused by the problem, even if the particular obsessions and compulsions are well hidden. There are many different types of OCD, and some fears and compulsions are much more apparent than others to an observer. Friends and family may notice somebody checking a lock repeatedly, washing something excessively or repeating a physical activity. Less obvious are mental rituals like replacing ‘bad’ thoughts with ‘good’ ones, saying a silent prayer or self-reassurance. You may have noticed your friend or family member being very quiet in certain situations, or saying something under their breath. However, there are many compulsions and reactions driven by OCD that can be going on in the person’s mind without anyone else knowing.

Another, very important, issue is that due to the shame and secrecy that often surrounds OCD, people can become very good at hiding their symptoms, or delaying their rituals until they are alone. People with OCD can become very skilled at generating subtle excuses so they can avoid situations where their problem will be worse. The general stigma of ‘mental health’ problems may also stop people from talking about their difficulties. It is useful to remember that, for these reasons, OCD can sometimes be difficult to spot. However, if OCD is around, you have probably noticed its effects, even if they are subtle.

In the table below we give a range of examples of what family and friends may notice in the behaviour of a loved one and how it might be related to certain forms of OCD. By reading further into this book it will become clear how and why each one of these can result from obsessional fears.

If the person you are concerned about is not sure if they have OCD you can go through this book together to see if these are the sorts of things that are happening and whether the understanding of OCD we talk about in the next chapters fits with what they are experiencing. There is some information here about other problems which can seem similar to OCD and how to get help for them.

WHEN THE PERSON YOU ARE WORRIED ABOUT IS RELUCTANT TO TALK ABOUT IT

Sometimes friends and family members may open the discussion before the person themselves, and sometimes things get to such a point that they feel forced to do so. There are two main reasons that people may not recognise the problem or seek help in the early stages. For some people, OCD can seem like a helpful friend at first as it may give them a sense of control in difficult circumstances. What can start as ‘normal behaviours’ can then gradually become excessive and harmful. Others may be very afraid of what is going through their mind and have no other way to make sense of it than that they are bad, mad or dangerous. This horrible fear may stop them disclosing the problem to anyone, even those they love, for fear of the consequences.

TRY TO BRING IT UP

It is always worth trying to discuss the problem with the person you are worried about, even in general terms – after all, you are asking because you have noticed something is up, even if they are trying to hide it. Sometimes being asked what’s wrong can be a great relief as things get into the open and they no longer have to cover it up, or worry about your reaction. If they have not yet discussed it then it may be because they feel very ashamed of their thoughts and behaviour and it may be difficult to go into detail. Assure them that you don’t need to know all the details if they don’t want to tell you but you just want to help them with an obviously distressing problem. Alternatively, they may feel embarrassed or ‘silly’ talking about the things they are doing (but this is replaced by real fear or anxiety when they are stuck in their obsessions and compulsions). Using some of the examples in this book might help your friend or family member to realise that they are not alone.

BEING SENSITIVE

It goes without saying that it is important to try to be as sensitive and understanding as possible and let people tell you in their own way, and in their own time. Some people like very ‘matter-of- fact’ conversations, some people might prefer an email, some people might like the analogies and metaphors we have used in this book as an opening to a conversation. Your friend or family member may feel more comfortable discussing their problems if they know about something you have struggled with in your life. The most important thing is letting them know that you want to help them work out what is happening, as this is the way they will overcome the problem. There is more information aimed at helping friends and family support someone fighting the problem in Chapter 8.

QUESTIONS YOU MIGHT ASK SOMEONE YOU THINK MAY HAVE OCD