THIS CHAPTER IS about the impact on those who live with or are close to someone with OCD and how these people may best try to help the sufferer through their difficulties. If you have OCD, there are sections here and here for you to show your friends and family to help explain the problem and how they can support you.

Recent years have seen a much greater understanding of how the problem affects not only sufferers but also those around them including parents, partners, children and friends. We will talk about the various possible effects on others and how to minimise the impact on them, as well as maximising help from others when you are fighting OCD. Many types of relationships can be affected by OCD, but for ease of reference we will use the term ‘family members’ to include all of those who may be closely affected by the problem of another.

If you have OCD, or if you live with someone with OCD, you can probably think of instances where OCD has affected not just the person with the problem but others too. If you are stuck in obsessional patterns of thinking and behaving, this can affect other people and your relationships with them in a number of ways. It may be that you are frequently late for work or social engagements as it is taking so long to do rituals, which may be causing difficulties and stress with others. You may have started avoiding certain places or even people because to go near them would mean that you would have to be extra vigilant or you would have to spend a long time doing checking or cleaning at the time or afterwards. It may make things awkward or cause arguments if you are asking people to do things a certain way, or if you are preoccupied by your fears when you are with them. Perhaps you feel that others are simply better off or safer without you there and you may feel very down and not feel like mixing with people at all. Often people who have OCD get very good at making sometimes very subtle excuses for avoiding things or otherwise explaining their behaviour. However, after a point, other people may notice that something is wrong, even if they have no idea that OCD is the problem.

In some cases the fact that something is wrong can seem more apparent to others than to the person themselves as they are so consumed with their thoughts and rituals. This is because, particularly in the early stages of the problem, OCD can masquerade as a friend by offering the illusion of control and protection against danger. By its nature, OCD deflects attention from the bigger picture towards the moment-to-moment task of trying to feel safe. It can take a long while before people realise how much their life is revolving around the problem and just how much it has taken from them. Sometimes only a crisis, or a change in their lives that exposes the problem, can help people really face up to this. This is why it is really important to sit down and think about how much the problem is costing you, and those around you, before such a crisis occurs.

Because OCD is driven by the inner world of thoughts and interpretations, there are not usually many places that people with OCD feel genuinely ‘safe’ and free of the problem. If you are stuck in OCD, it is often going on in one way or another, most of the time. Therefore relationships are likely to be affected, as it is very difficult to hide the problem all the time, and the OCD is of course keeping you anxious and afraid. It can be very upsetting to see a friend or loved one being drawn into obsessional behaviour. This is particularly difficult when they cannot see themselves how destructive it is. OCD keeps people in a state of anxiety and alertness to threat, and the threat can be from internal sources (your own thoughts and feelings) as well as external sources (for example, contamination). It can be very difficult to make sense of for anyone who is not inside it, and it is difficult even if you are inside it. People with OCD are often told, asked or even begged by those that know them to ‘just stop’ their rituals and behaviours. Of course, if it were that straightforward, the person with OCD would have done this already. They may feel very frustrated in their efforts to stop ritualising and control the OCD. As the person with the problem, it can be hard to explain to others that, even though you know it is unlikely and even a bit irrational to think that something awful will happen, the fear of it happening is very powerful, particularly in the moment that it is triggered.

Often people will not disclose the contents of their intrusive thoughts even to loved ones, for fear that their reactions will confirm that they are somehow mad, bad or dangerous. Shame is a strong motivating factor for keeping OCD a secret, but it also keeps the problem going as people are left alone with their OCD fears and doubts with nothing to compare or reality check them against. If you have not told anyone in detail about your problem then, looking at this from the outside, the only information available to family members may be that you have become very anxious, secretive, avoidant, irritable or distant.

Even when they do disclose the problem to others, people are often torn between their anxiety and the knowledge that it is affecting their relationships. Feelings of guilt about the impact on others and worry that they are driving others away by their behaviour can further compound the problem. People can often feel terrible when they know their behaviour is having a damaging effect, but feel helpless to do anything about it. We will now have a look at some very specific ways that OCD behaviour gets in the way of relationships and how forces might be joined against the problem.

REASSURANCE

One of the most common ways that OCD impinges on relationships is the need for frequent reassurance. As we discussed earlier, this is a very common means that people use to manage their anxiety. Asking someone to reassure you that the door is locked, that you didn’t make a mistake or that you are not a bad person is a logical thing to do if you doubt yourself. However, when it is part of OCD it has the effect of keeping the problem going by reinforcing the belief that there is something to be reassured about, by raising more doubt and by undermining your ability to tolerate ‘normal’ uncertainty. Therefore, repeated reassurance seeking does not help the person, but helps the OCD.

Let’s have a think about this again from the point of view of the person providing reassurance. By definition, to ‘reassure’ is to make certain again. This is an oxymoron, that is, the two parts of the word are conflicting, because if you were already certain, you would not of course need to do this repeatedly. For the person being asked to give reassurance this fact is plain, as they do not experience the anxiety, doubt and sense of over-inflated responsibility associated with OCD that drives people so strongly to look for certainty and safety. It can be very tiring to be asked the same questions over and over again if you cannot really see the point of it, apart from calming down the person asking you. Often, the reassurance becomes increasingly meaningless over time as the ‘reassurer’ will ‘just say it’ to try to satisfy the person with OCD. It is not uncommon for the person with OCD to be on high alert for this ‘devaluing’, as of course to them it is equally important each time and ‘less than perfect’ reassurance (as all reassurance is) will make them feel more anxious. They may feel less safe as they search for flaws in the reassurance, for example, ‘He wasn’t really paying attention then, how do I know he has cleaned the chicken and not touched anything else in the kitchen?’ Such thoughts can lead the questioner to ask again, to monitor the behaviour of the other person, and to do the job again, but ‘properly’ this time. This can lead to tension, frustration and conflict with both parties feeling like they are not understood.

GETTING OTHERS TO FOLLOW YOUR OBSESSIONAL RULES OR ‘ACCOMMODATION’

This term was first used a few years ago to describe the degree to which family life is altered to adapt to or accommodate OCD. It makes sense that, if you are strongly driven to follow a set of obsessional rules, you may require others to follow these rules in order to stay safe, or to fulfil your sense of responsibility to keep others safe. After all, the OCD will not be satisfied until you have done everything in your power to protect others. This could be things like getting family members to check locks and appliances or asking them to wash their hands repeatedly or change their clothes as soon as they enter the house. Sometimes, it becomes difficult for the person with OCD to delegate any tasks as they just cannot be sure that others will carry them out with the same standards that they would have applied. They may become very anxious about sharing the tasks of family life and restrict what others can do or get into conflict about the standards of the people they live with. If the OCD is focused on the person worrying that they themselves are a danger then the opposite may be true, and they may want to delegate all tasks where they could cause harm. Given the nature of the problem, this can start to affect almost anything, for example food buying and preparation (fears of accidental contamination), driving (fears of accidentally running someone over) and childcare (fear of abusing a child). The avoidance that is so commonly found in OCD can affect the whole family in terms of the activities they are allowed to do, or the quality with which these things are enjoyed, and is, therefore, part of accommodating the problem.

Brian had been married to Mary for seven years. She had always been a scrupulous and careful person who kept things clean and in order but was able to enjoy life. Brian noticed that over time, her need for order and cleanliness began to become stronger and more rigid. They had always had a rule of taking shoes off when they came into the house but soon Mary required him to do this straight away and would become very agitated if he delayed at all. Before long she insisted he changed his clothes into ones she had washed for him as soon as he came in from work. The washing machine was constantly on the go. It became hard to have people round or to go out socially as Mary was very preoccupied with the idea that things outside the home could be dirty. This was very hard for Brian and while he tried to be understanding, he also felt resentful that everything in their life was affected by the problem. Things got particularly bad after they had their first child Jeff, when Mary became very preoccupied with cleaning and sterilising the baby’s things. She insisted on performing all of the daily tasks for Jeff and would watch Brian carefully whenever he was looking after him. This led to many arguments and conflicts between them as Brian felt Mary did not trust him to look after Jeff. She would constantly ask Brian for reassurance that things were clean and that they had not touched anything dirty but would often go and clean them again anyway. Mary and Brian would often argue about this. Brian was often very sad to see that Mary had become so imprisoned by her anxiety, but felt that it was unreasonable that he had to follow her rules. However, if he did not, he knew that this could make her feel worse. He felt very stuck.

Brian’s story paints a stark picture of how OCD can affect a family. Clearly, in reality families are affected in a range of ways and to greater and lesser extents than this. People can get very good at compartmentalising the disorder, and as we know, people with OCD are very loving and caring and responsible. However, if OCD is affecting your family at all, then it is too much.

HELPING YOUR FAMILY TO BREAK FREE FROM OCD

While we know that rituals, compulsions and reassurance make the problem worse, it is very difficult to deny help with these things to someone who is desperate and anxious. It is wholly understandable that families do give reassurance and even accommodate compulsions and rituals. The problem is not located in family members doing these things, but the fact that they are being asked to do them in the first place. If you have been doing this, then it is as a result of your OCD bullying you. Obsessional behaviour is born of fear. You do not need to feel guilty about it as you were trapped in this fear. Before you really understood what was happening and how OCD works you did not have a real choice to do anything differently; you were doing the best you could. Even knowing about OCD does not make it easy to change but it is certainly a good starting point. Now is the time to really get angry with this problem bullying you and getting in the way of your life.

The route to changing and breaking free from OCD is for you to understand the problem and what is unhelpful and to test out what happens if you do things differently. If you feel able, sharing this understanding and knowledge with a trusted loved one or friend can help in several ways. First, explaining the problem to someone else gives you a way to make sure that it makes sense to you and clarify your own understanding. If you would rather not explain in detail, you can talk in general terms about the principles involved, in particular the vicious flower we discussed earlier. Second, the other person may not really know about OCD, or about your OCD and what sort of a problem it is. It may come as a relief to know that this is a problem of anxiety that has a strong internal logic. Third, if the other person understands what OCD is and how it works, then they will better understand how to help you in your fight against the problem. Of course, only you can change your behaviour, but if you feel strongly compelled to avoid something, ask reassurance, or ritualise, they can help you focus on the fact that this is part of the OCD, not a behaviour that is keeping them or you safe, in order to help you in your decision making.

SOME PRACTICAL STRATEGIES

BEHAVIOURAL EXPERIMENT: REASSURANCE

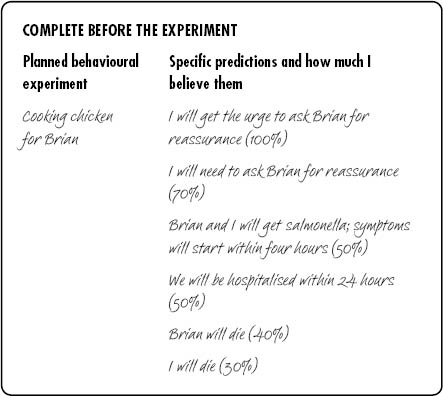

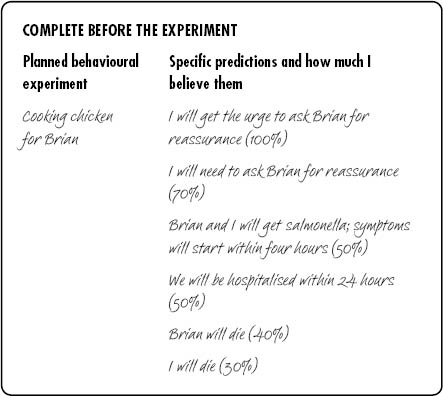

Mary would often ask Brian for reassurance. She would ask him if he thought that the bus was safe, if her hands were clean enough, if she had cooked food for long enough.

Mary and Brian discussed the role of reassurance – it makes OCD worse. Mary explained that whilst she experienced a temporary relief of anxiety, in the long term reassurance worked in the same way as all her safety-seeking behaviours – it made her thoughts and beliefs about contamination feel more important. It also made her reliant on other people – another way that OCD had robbed her of her freedom. Mary undertook to not ask Brian for reassurance but worried that she would get very anxious and might need to ask for it. Brian pointed out that refusing to give reassurance is hard and upsetting for both of them as he felt unkind and Mary would get upset. They agreed that rather than Brian refusing point-blank to give reassurance, he would try to remind Mary that reassurance is the OCD trying to ruin her life. They agreed that he would say:

They agreed that Mary would cook dinner and try to not seek reassurance about whether the food was properly cooked:

One of the best things about fighting back against your OCD is that it benefits not only you but those around you, and often straight away. You will have more time, more freedom and more clear-minded attention without this problem. A huge OCD lie is that not performing rituals and compulsions is irresponsible, and potentially harmful to others. It may feel like this at first, which of course does not make it true. If you ask your family, it is likely that they will agree that they do not get any benefit from you having OCD, and that they would rather have you back, OCD-free.

Mary felt horribly guilty about the impact of her fears on Brian but had always thought of it as doing her best to try to protect him and her son Jeff. While she knew she could go a bit far with her rules and worries, she had never really thought of it as a problem until she read an article on OCD in a magazine. This described many of the behaviours and thoughts she herself had. The more she thought about it, the more she realised that she had gone further and further in her behaviour which had had an effect on everyone in the family. Although they had not been physically ill for a while she understood that the home was not very happy. She showed the article to Brian who was hugely relieved to know that this problem had a name, and that treatment was available and effective. Mary researched OCD more and went to her GP who confirmed the diagnosis and referred her for CBT. During therapy she identified the problem as one of fear that she would be responsible for Jeff becoming ill rather than danger that he would become ill. She explained this to Brian, who was more understanding towards her not wanting him to help with Jeff. He was pleased that her goals involved not checking on him, and getting him to take Jeff out for the day, as well as allowing the house to become messy, well, less strictly neat and clean. He was particularly pleased that he no longer had to change when he came in. It was difficult for Mary in the first stages, and she would still frequently ask Brian for reassurance and would occasionally even clean after him. Although it was difficult to see the OCD bullying her occasionally, Brian was less annoyed as he understood why she did this. He felt proud that she was confronting her fears that had been growing for so many years. The obvious delight of Jeff as Mary and Brian watched him play in the local sandpit was a strong motivator.

If you are having difficulty not asking for reassurance or not asking others to follow obsessional rules, think about two visions of the future. Project forward to five or ten years’ time. In the first exercise, imagine how family and social life will be if you carry on with the obsessional behaviour. Try to put yourself in the position of those around you and what their life would be like if they go along with it. It is likely that this is a future of restriction, conflict and unhappiness. Would they be thanking you for ‘keeping them safe’ and following your rules? It’s unlikely isn’t it? Think now of the alternative future, where you start and continue in the fight towards an OCD-free life. What will your relationships be like after five or ten years of this? What will you be able to do? How will others feel about you for not being obsessional? This is a real choice that you have and a real future that you can have, if you let go of your OCD.

Spouses, friends and parents are usually the people most involved in supporting people with OCD as they are adults, but in families with children there are some particular issues and questions that often present themselves.

MY OCD IS MAKING IT VERY DIFFICULT TO DEAL WITH MY CHILD’S DEVELOPMENT AND BEHAVIOUR

As we develop from infancy to adulthood, we all go through a number of different developmental stages. If you are a parent with OCD, depending on the time that you developed the problem and depending on the type of OCD you have, it is possible that various aspects of your child’s behaviour may have come into conflict with the demands and rules of your OCD. One obvious example is, if you have worries about contamination and dirt, then the normal behaviour of a toddler and child – getting very messy, putting their little hands in all sorts of things and in their mouths – may be very anxiety provoking. The OCD may say, ‘Well, it’s fine to take a risk with yourself, but what about your child?! That’s really irresponsible!’ This is not true. OCD is a damaging problem that causes people to take unnecessary and excessive precautions that become a problem in themselves – your child needs to explore and have contact with the world. The most responsible thing you can do is not to do what the OCD wants and to allow the baby to do ‘normal things’. It is important to see that the OCD will focus you on one domain, in this example safeguarding the child’s physical health. If you think about all the things that contribute to being a good parent, there is far more to it than that. Most people would also include emotional availability, ability to have fun, the ability to soothe and comfort the child and many other qualities and abilities. All these things are important (although no one person will be perfect in any domain); focusing on just one part of being a parent is likely to affect the other parts. Fighting back against the OCD will put things back in balance and help you be the best you can be.

If you are not sure what is ‘normal’ with regard to boundaries for children, have a look when you see parents with their children and ask other parents if you can what sort of approach they take. There will always be a range of behaviour and different opinions on how to go about things. However, most people would not take the extremes of overprotection/restriction of the child or under-protection/laxness but will be somewhere in the middle as a general guide.

Another area that may be difficult for you if you have OCD is helping your child manage their own fears and anxiety, and this is perhaps particularly difficult if your child is showing signs of being obsessional. This is very understandable – of course, it will be harder for you to help your child if their fears chime with yours and many parents with OCD feel very guilty that they may have ‘passed on’ the OCD (more below). Recent research says that working on your own difficulties will help you help your child as you will truly know what the experience is like and the realities of facing up to your anxiety. Many treatment programmes for children with clinical levels of anxiety will involve the parent as a co-therapist (whether they have anxiety or not). Treatment is likely to be more effective if the parent has at least an understanding of their own difficulties.

CAN I PASS ON OCD TO MY CHILDREN?

If you have suffered from the debilitating effects of OCD, it is understandable that you will not want your children to experience what you have been through. It is a common worry that OCD can be ‘passed on’ to children, particularly for parents whose own parent may have had the disorder. Of course, children are influenced by parents, that is the way that it should be, and if you have OCD they may have noticed that you are anxious at times and will try to make sense of that. However, remember that the OCD is only one part of you and what is going on in their lives. We discussed biological and psychological vulnerabilities in more detail in Chapter 2, but the overall message is that it’s perfectly possible to have OCD and for your children not to have OCD. In fact, it’s also possible to have OCD and be a very good parent. However, that does not mean that you should live with the OCD, far from it. The fact that it is there means that it will be affecting things in some way, like having less time to give to your children (or yourself) or enjoying being with them less due to the depression and anxiety. It may be affecting life in more direct ways such as stopping you going to particular places or doing certain activities.

Apart from getting rid of the OCD (if that’s not immediately possible for you), one of the most important things you can do to minimise any possible impact on your children is to not involve them in your obsessions and rituals. This will not only make sure that they do not ‘pick up’ any obsessional ideas or get frustrated by having to follow obsessional rules, but it will help you challenge your own OCD and see that those rules are really not necessary. As well as being therapeutic for you, it can be a lot of fun for children to be allowed to make a whole lot of mess. You will enjoy being a parent, and your children will enjoy you far more without OCD in your life. The best thing you can do for you and your child is overcome your OCD.

DISCLOSURE

There is no hard and fast rule about the best time, how, or indeed whether to tell a child at all that you have OCD. This, of course, depends on the particulars of your situation and the age and nature of the child. As one person in their twenties said, ‘My mother used to disappear into the bathroom for hours on end. For years I thought she had some sort of drug problem, but one day she sat us down and said that it was OCD and that she went into the bathroom to do her rituals. I was so relieved!’

You know your situation and your child and can make a judgement as to whether disclosure is appropriate and likely to be helpful. Of course, as ever, the best disclosure is that you have had a problem called OCD but you are now working through it and these are the new things that you and your child will now be doing.

OCD DURING PREGNANCY AND POST-NATALLY

Until recently OCD during pregnancy and after having a baby had received very little research attention. However, recent studies suggest that OCD may be more common at this time than other times in life, with 2–4% of women experiencing clinical levels of symptoms. Some people develop OCD for the first time either during pregnancy or afterwards, while others find that pre-existing symptoms worsen. However, some people can feel better in pregnancy.

Although perinatal OCD, as OCD at other times, can be about anything, most commonly it revolves around significant fear of harm coming to the infant, with worries frequently focused on accidentally harming the child, the child becoming ill or deliberately harming the child. It is important to note that the occasional experience of all of these worries is absolutely normal and indeed very common in parents and parents-to-be. However, some people find themselves so distressed that they will take measures to manage their anxiety or prevent their fears coming true. In this way the thoughts and behaviours can interfere significantly with their well-being and their experiences of pregnancy and parenting. This problem can happen to women and men if their partner is pregnant. As with all forms of OCD, it is the extent of and response to the worries, rather than just having them, that becomes the problem.

For example, in pregnancy a woman may be very concerned that something she eats or touches may cause harm to the unborn baby. This may cause her to avoid and restrict foods, places and situations well beyond the recommended guidelines in order to keep as safe as possible, or at least feel that she has done everything in her power to do so. She may spend large amounts of time cleaning and washing and ask those around her to do the same. Women with such concerns may seek excessive reassurance from friends, family and professionals that the baby is developing okay and that her behaviour is ‘safe’ and will seldom be reassured by the answers given. Post-natally, these concerns may revolve around other illnesses of childhood with mums taking measures such as excessively checking their child when asleep, so that she does not sleep or relax at all herself.

Another common theme of perinatal OCD is thoughts of deliberately harming your own child. After the birth, many parents experience occasional fleeting thoughts that they may deliberately harm their baby, but are able to dismiss these as meaningless. Some women interpret the very fact that they have these thoughts as meaning that they may act on them and become frightened about their potential to harm their child in a moment of madness. They may then, after the birth, avoid contact with the baby or take special measures to stay ‘safe’ around the child, such as hiding knives and sharp objects in the home.

It may be particularly difficult for mums firstly to recognise their experiences as OCD and then to seek help due to the shame and secrecy associated with the disorder, especially at a time when they and those around them expect them to feel happy. As there is often a lack of awareness of OCD during pregnancy and post-natally, people are rarely asked about these experiences by professionals. If you think that you might have symptoms it may be up to you to suggest that you have OCD and ask for an assessment by someone who knows about this problem.

HELPING SOMEONE BREAK FREE FROM OCD – INFORMATION FOR FAMILY AND FRIENDS

This section is designed to be read by people who are helping someone trying to break free from OCD. In Chapter 1 we discussed recognising OCD in someone you know and how to approach the problem if you are not sure it is OCD. Here we discuss developing a shared understanding and turning this into strategies for helping someone break free from OCD.

You may be a partner, friend or the son or daughter of someone who has this problem and, if so, it is likely that OCD is affecting you in some way too. In fact it can be really hard living with someone who has OCD. At the very least it is upsetting to see someone you care about struggling with the problem and stuck in harmful cycles of behaviour. For most people with OCD, the harm extends beyond themselves: for friends, partners and family, constantly being asked for reassurance, perhaps trying to follow OCD rules and coping with the sufferer avoiding everyday tasks and places can be very draining and can cause lots of conflict. In most cases, the person with OCD knows that their behaviour is excessive and feels very guilty about the impact it is having on others, but even so, they are stuck doing the same things. This is because they really have been stuck in the grip of the OCD bully.

Throughout this book we have encouraged those with OCD to think about how much the problem is affecting all aspects of their life, including relationships. Even though this is sometimes painful to reflect on, we want people to do this so that they can say ‘enough is enough’ to OCD and stay motivated in the sometimes difficult and uncomfortable job of standing up to this bully.

GETTING A SHARED UNDERSTANDING OF THE PROBLEM

Of course, only the person who has the problem can do the work of breaking free from OCD, but reading parts of this book or getting the person to explain it to you will give you a deeper understanding of why they do what they do. The most important things for friends and family to remember are that:

A discussion may help them clarify their own understanding of OCD and might also give you the opportunity to ask questions and explain things from your point of view. However, sometimes this sort of discussion is difficult as the topics can be very sensitive – just having a shared general understanding of how OCD works is a good starting point.

FIGHTING A COMMON ENEMY

People with OCD have spent a long time trying to stop bad things from happening. Throughout this book we present an alternative way of understanding OCD – that it is a problem of worry and anxiety about the meaning of thoughts and about terrible things happening. How one deals with a worry problem is to confront the fears to find out what really happens. In practice, broadly speaking, this means not washing or checking to see what happens, or not grappling with thoughts. It also means not avoiding anything. Although this may be terrifying at first, if someone with this problem can really direct their efforts at beating the problem of worry, the OCD will have nothing to grip on to.

As a supporter, having an understanding not only of what OCD is, but how to deal with it, will be really helpful at those moments when the person is being sucked back into the problem. It may be worth drawing up some strategies together for those times. Some examples are below:

When I ask you if you washed your hands:

When I want to go back to check the locks:

Remember, it’s okay if you both find it hard to stick to these. Just have another go at working out the strategies or getting the sufferer to remember why they are there when they are less anxious.

WHAT TO ENCOURAGE

It is important to encourage the person to choose to change – perhaps remind them what life could be like without this problem, that when things are tough it’s just the OCD trying to bully them as it wants to stay around.

Supporting their motivation is useful. Wherever possible, ask them what they are planning to do or what they have done to work on their OCD. Help them recognise when they achieve their goals.

Offer support and encouragement wherever possible – and for yourself too, as supporting someone with this problem takes patience and time.

Rewards help too: perhaps aim for a treat together that OCD may have got in the way of in the past.

WHAT TO AVOID

People with OCD are often told to ‘just stop’ doing their rituals. Blanket bans or strategies like removing the means by which they can do their compulsions (e.g. soap) does not give them a choice and will be experienced as unhelpful.

LOOKING AFTER YOURSELF

It’s important to remember that it is not your responsibility to cure someone of their OCD, and that you are there to support them in their journey. If you could have done it for them you probably would have! Living with someone with OCD can be a strain and if you are experiencing difficulties, focusing on helping yourself will make you a more effective supporter for them. This could be something simple like making sure you get to do at least some of the activities you want, even if your friend or family member cannot, due to the OCD. It might mean something more like seeking support or even professional help for yourself. Some resources are given at the end of the book, including websites with dedicated sections for supporters.

For people with OCD it can sometimes take a few goes to really get rid of the problem, perhaps because the person is not truly ready to let go at that particular time or there is just too much else going on. Encouraging them to seek help is important and we have more suggestions about this for sufferers in the previous chapter.