We do not consider our principles as dogmas contained in books that are said to come from heaven. We derive our inspiration, not from heaven, or from an unseen world, but directly from life.

—Atatürk, 1937

If under the present conditions we manage to create an acceptable type of society and set up a model of development, progress, evolution, and correct Islamic morals for the world, then we will achieve what the world has feared; that is, the export of the Islamic revolution.

—Hashemi Rafsanjani, 1988

REZA PAHLAVI, SHAH OF IRAN, and Saddam Hussein, President of Iraq, had much to fight about. They were immediate neighbors and both claimed the strategic Shatt al-Arab waterway on the Persian Gulf. Iraq was Arab, Iran, Persian. Whereas the Shah supported U.S. hegemony in the region and cooperated with Israel, Saddam leaned toward the Soviets and sought to lead the Pan-Arab movement. Notwithstanding these serious occasions for conflict, in the 1975 Algiers Agreement Saddam had relinquished Iraqi claims to the Shatt al-Arab waterway, and the Shah had ceased supporting Kurdish separatists in Iraq. In September 1977, as anti-Shah demonstrations were breaking out in various Iranian cities, Saddam had agreed to the Shah’s request to expel the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini from Najaf, Iraq, from which he was inspiring and directing the unrest in Iran. This last bit of cooperation points to one common interest of increasing importance. Each despot ruled a country the majority of whose population was Shia Muslim, and each was attempting to develop his country by means of state-led growth, centralization of power, and secularization. And therefore the two rulers shared a surprisingly durable and resilient enemy: a transnational, resurgent Shia-Islamism that insisted on the restoration of religion to its traditional position in society, a resurgence largely propelled and symbolized by Khomeini.

From Iraq Khomeini went to Paris, from which he continued to stir up and harness political radicalism in Iran. On January 17, 1979, the besieged Shah fled Iran, and two weeks later Khomeini arrived from Paris. It was not yet clear what direction the Iranian Revolution would take, as liberals and Marxists had joined Islamists in ousting the Shah. Islamists themselves were divided between Khomeini’s radicals, who sought a faqih or clerical regime, and moderates who did not. Mehdi Bazargan, a moderate Islamist, headed the provisional government. Like the Russian Bolsheviks in 1917 (chapter 6), the Khomeinists sought to seize control of the domestic revolution by stirring up revolution abroad. On February 11 Khomeini announced, “We export our revolution to the four corners of the world because our revolution is Islamic; and the struggle will continue until the cry of ’There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is the messenger of Allah’ prevails throughout the world.”1 Khomeini’s most immediate target was his former home-in-exile, Iraq. Iraq’s territory housed six Shia holy sites.2 During his sojourn there, Khomeini had become close to Ayatollah Muhammad Baqr al-Sadr, head of the Islamic Call Society (al-Dawa), a movement that sought to combat Saddam’s Baathist secularism. Now that Khomeini was back in Iran, Sadr sent congratulations and praised his plans to implement a faqih regime.

Events in Iran polarized Iraq between those who favored a similar revolution in Iraq and those who did not. Transnational coalitions strengthened and their competition intensified: Khomeini and his circle in Iran and al Dawa in Iraq promoted a Shia faqih regime in both countries, while the Baathist regime in Baghdad and moderates in Iran opposed such a regime in both. Each faction reached into the other country to try to influence events there, knowing that the outcome in one country would affect the outcome in the other. In June, as Ayatollah Sadr tried to lead a procession to Tehran to congratulate Khomeini, Saddam placed him under house arrest.3 Shii demonstrated in several Iraqi cities in response, and, as Dilip Hiro writes, “Tehran Radio’s Arabic service referred to Sadr as the ’Khomeini of Iraq’ and called on the faithful to replace ’the gangsters and tyrants of Baghdad’ with ’divine justice’.”4 In July, Saddam submitted to Iraq’s figurehead President Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr a list of Islamists, including some in the military, for execution. When Bakr balked, Saddam placed him under arrest and named himself President. At the same time, Saddam tried to keep more Iraqi Shii from joining the Islamists by hinting that his Sunni-led Baath Party would share more power with them and declaring as a national holiday the birthday of one of the Shii’s major figures. In March 1980, Saddam had scores of al Dawa leaders executed. In retaliation Iraqi Shia Islamists tried to assassinate Tariq Aziz, Saddam’s (Christian) deputy, in April. Saddam responded by having Sadr executed. On the same day, Iran’s Foreign Minister announced, “We have decided to overthrow the Baathist regime of Iraq.”5 The Khomeinists in Tehran began training Iraqi Shia guerrillas and sending them back to Iraq. Saddam hosted key officials under the deposed Shah and broadcast their propaganda into Iran. These Baghdad-sponsored officials attempted military coups against Khomeini on May 24-25 and again on July 9-10.6

With regime change the goal of each for the other, the stakes could rise no higher for either Khomeini or Saddam. In August, Saddam visited the rulers of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait and secured their quiet support for the toppling of Khomeini, by force if necessary. Saudi Arabia was itself an Islamist country, but the Saudi dynasty was Sunni rather than Shia and hence had two strong motives to see the world rid of Khomeinist Iran. Their country’s own Eastern Province had a Shia majority, some of whose members were inspired by the Khomeini revolution. And Khomeinist Iran was denouncing the Saudi monarchy as corrupt and unfit to lead the Muslim world, thereby challenging the monarchy’s chief claim to legitimacy.7 By September, Saddam had 50,000 troops massed on the Iranian border and abrogated the 1975 Algiers Agreement: now the Shatt al-Arab, he insisted, was all Iraqi territory. Iraqi forces invaded Iran on September 22, claiming that Iranian forces had attacked first.8

Like most bordering states, Iraq and Iran had many conflicts of interest in 1979-80, conflicts that made war a perpetual possibility. But the two states had cooperated for four years. What ruined the cooperation and brought on the Iran-Iraq War, a war that lasted a decade and killed as many as 1.5 million people, was the stated desire of each ruler, Saddam and Khomeini, to overthrow the other’s regime. The immediate cause of those mutually conflicting, zero-sum preferences was the Iranian Revolution and establishment of Khomeini’s faqih regime in Tehran.9 But the revolution had the effect that it did on Iranian-Iraqi relations because it was embedded within a longer transnational struggle between Islamists and secularists. Secularism was a domestic and foreign danger to Khomeini’s vision for Iran. Islamism was a domestic and foreign danger to the Baathist vision for Iraq. The revolution intensified the transnational struggle by heightening the threat to Saddam’s regime, which in turn began to threaten Khomeini’s regime; the war, in turn, intensified the struggle still more. And the struggle extended far beyond Iran and Iraq; elites in much of the Muslim world had been participating in it for many decades.

On its surface, our final case study of a long wave of forcible regime promotion is less spectacular than our first three. It has produced far fewer direct uses of force to promote one regime or another. But as discussed below, there have been a number of such regime impositions, many by outside, non-Muslim powers—most recently, the United States and various allies in Afghanistan and Iraq. As in the cases in chapters 4 through 6, governments in the region have also used other means, including propaganda, economic aid, military training, and covert action, to promote one regime or another. The struggle has been most intense in North Africa and Southwest Asia, and so in this chapter I exclude Southeast Asia, home to hundreds of millions of Muslims.10

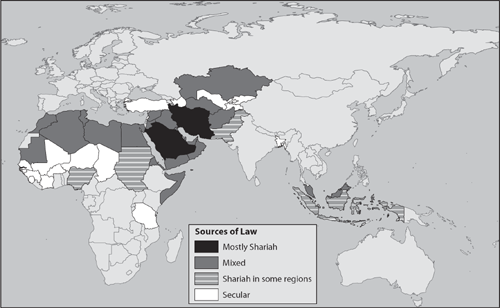

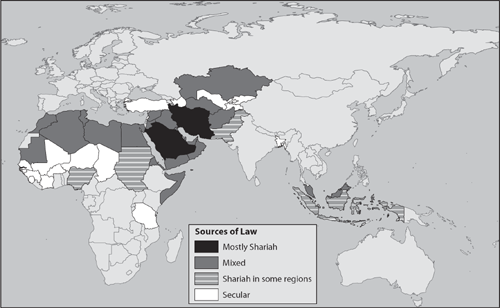

As with previous long waves of forcible regime promotion, one condition that has helped cause this one is a prolonged transnational ideological struggle among Muslims over the best regime. The struggle is among various types of secularist and various types of Islamist. It is perpetuated by networks of elites that span Muslim states and agitate for one or another of the ideologies. As with earlier transnational struggles, rulers and would-be rulers have attempted to harness these networks and their ideas and turn them to their own ends. At times rulers have found themselves more controlled by than controlling the networks. Rulers take sides in the struggle because their legitimacy is at stake. Like all transnational ideological struggles, that dividing the Muslim world is complex. But the core disagreement concerns the proper source of society’s laws and institutions. Ought positive law—the laws of human society—to derive from Islamic law or Shariah, that is, divine revelation to the Prophet Muhammad (the Quran) and the sayings and practices of the Prophet (hadith)?11 Or ought positive law to derive from non-religious sources such as autonomous human reason or natural law? If Shariah, then which version of Islam, Sunni or Shia, will set the terms? If secular, then should the regime be more like a Western, multiparty one or the single-party one exemplified by Nasser’s Egypt? Map 7.1 displays majority-Muslim states according to the degree to which law derives from each source. Some states, such as Turkey, have entirely secular law; others, such as Saudi Arabia, entirely divine; others, such as Egypt and Afghanistan, mixed constitutions; still others, such as Nigeria and Pakistan, vary by province or region.12

Unlike the struggles analyzed in chapters 4 through 6, that cutting across the Muslim world is ongoing at the time of this writing and seriously affects relations among sovereign states, including non-Muslim states such as the United States. The intra-Muslim contest over the best regime may yet have a long life ahead. The struggle is seen in the persistent eruptions of legitimacy crises in countries and provinces whose populations contain significant proportions of Muslims. Across time and space, these crises have a common shape. Actors who have diverse discontents with diverse causes nonetheless appeal to common sets of symbols and present themselves as participating in a single battle that others past and present have waged. In the early years of the struggle, from the 1920s through the 1960s, secularism had the wind at its back and traditional Islam was in retreat. The wind reversed direction in the 1970s, as discontented intellectuals and army officers began to find in Islamism—an ideology reformulating traditional Islamic society—an articulation of their discontents and a set of prescriptions. The contest originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as Muslim elites grappled with their societies’ clear decline vis-à-vis the West. In more recent decades, a crucial test of legitimacy among many Muslim elites (and masses), particularly in the Middle East, has become which regime type is better able to damage Israel. From 1948 until 1967, secularism appeared better equipped to destroy Israel; since that time Islamism has assumed that position.

MAP 7.1. Islamism v. Secularism in heavily Muslim countries, 2009

Source: Central Intelligence Agency, World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

During this ongoing grand struggle, when one country appears on the verge of changing from a secular to an Islamist regime, or when there is a contest between Sunni and Shia Islamists, demonstration effects appear in other countries and actors polarize according to whether or not they favor the change. Elites then have stronger incentives to thwart ideological foes in neighboring countries. The ideological struggle has come to dominate not only majority-Muslim countries stretching from West Africa to Southeast Asia, but also affects the millions of Muslims in India and Western Europe. It also affects the United States owing to America’s global power, particularly in the Middle East, and its status as an exemplar of secularism. Many Islamists consider America the “far enemy” because they believe it keeps the “near enemy”—secularist and apostate Muslims—in power in Muslim countries.

Why isolate Islamism, when other major religions also contain anti-secularist movements? What Gilles Kepel calls the “revenge of God”—the resurgence of religion in defiance of the expectations of social science—has been at work among Christians, Jews, Hindus, and others since the 1970s.13 But thus far only Muslims have been able to activate a transnational movement that has captured states and bids to capture more. Notwithstanding the rhetorical efforts of some religious conservatives such as Dinesh D’Souza14 and secularists such as Andrew Sullivan,15 there is no Religious or Anti-Secular International and will almost certainly never be one. The connections among conservatives or radicals in each religion are weak; Islamists draw little or no comfort from the successes of the Christian Right in America (who, in any case, do not seek to overthrow the American regime of constitutional democracy, but simply to reform it); orthodox Jews in Israel are not dejected at the setbacks suffered by Hindutva in India.

Like all the transnational movements in this book, Islamism and secularism are complex and multiform. Islamists may be Sunni or Shia, monarchist or republican, left- or right-wing.16 Broadly speaking, Islamists agree that for Muslims to live piously their laws and institutions must model and enforce piety; Islam, Arabic for “submission,” applies to society as well as the individuals within it. Thus, Islamists cannot accept the notion that religion is a private matter or that the public realm must be secular. Nor can they accept, in the long run, life in a society constructed by some alternative religion such as Christianity or Hinduism. Secularist Muslims, for their part, vary in militancy. The aggressive atheism of communism sought to eliminate revealed religion, sometimes by direct coercion. Most Muslim secularist regimes have instead sought to tame religion by fashioning a Hobbesian state that controls religious training and regulates practice.

By no means are all Muslims Islamists; indeed, that is what I mean when I argue that the Muslim world is in a prolonged period of ideological strife. Many Muslim elites in some countries, and most in a few, are secularists who accept the legitimacy of law deriving from extra-Islamic sources. Among the Islamists, not all are radicals or terrorists. Some, such as Turkey’s Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi (AKP) or Justice and Development Party, have evidently embraced constitutional democracy and the European Union’s list of human rights. (Indeed, it is not clear whether the AKP qualifies as Islamist.) Some Islamists, sometimes called religious nationalists, seek revolution in their own country as the only route to Shariah.17 The most radical Islamists are internationalists, aiming to destroy the nation-states that divide the Muslim world and to re-establish the caliphate. For internationalist Islamists, religious nationalists satisfied with Shariah in their native Egypt or Lebanon are missing the point: the restoration of pristine Islam requires a united Islamic empire under the rule of the legitimate successor to the Prophet Muhammad. As with previous transnational movements, Islamism attracts people with diverse grievances, some contradictory. Especially attracted in many lands are the poor and their advocates, who see a restoration of traditional institutions as a route to greater equality.

The extremists are sustained to some extent by the latent sympathies of some of the moderates, who admire the activism if not the methods of the extremists. In times of high polarization, when middle ground is disappearing, moderates feel compelled to sympathize with the extremists against the common foe, and differences among Islamists and among secularists disappear.

Islamism today is typically labeled radical, but in the Islamists’ own telling it is restorationist, aiming to reestablish the old regime against the radical innovations of the secularists. From the Middle Ages through the nineteenth century, the Muslim world accepted that the only legitimate regime was the theocracy established by the Prophet Muhammad in the seventh century A.D. Muslims were certainly divided politically. Competition was common among ethnic groups, branches of the faith, and of course tribes, families, and individual leaders. Muslims differed over whether the ruler is the sole interpreter of the law (as the Shii held) or whether he should consult jurists (as the Sunni held). But Muslims agreed that the proper regime was a theocracy. The original Islamic regime was a unified umma (community) under the temporal and spiritual rule of a single man, the caliph, successor to the Prophet. As sultans, temporal monarchs, came to assume de facto power in the caliphate, Islamic jurists developed theories legitimating their rule. Al-Ghazali (1058-1111) argued that if necessary the ruler could be someone other than the legitimate caliph as long as he enforced Shariah. For Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328), the ruler must consult with a council of (religious) scholars when interpreting the law. Ibn Khaldun (1333-1406) dealt with the development of states within the umma and argued that a pious regime of Shariah was possible even then.

TABLE 7.1

Forcible Promotions of Secularism or Islamism, 1958-2005

Common to all of these theories of authority was an absence of recognition of a secular realm of life, one separate in some sense from spiritual or transcendent reality. Hence, mosque and state could not be divided. Islam, “submission” to God, was not simply a plan for the individual to achieve paradise in the afterlife, but also a plan for a community or umma in this life made harmonious by the obedience of all to Shariah. This community required enforcement of Shariah, however, and hence a central coercive authority—a state. As Albert Hourani writes: “in the Muslim umma power was a delegation by God (wiyala) controlled by His will and directed to the happiness of Muslims in the next world even more than in this.” Thus in the eighteenth century, when some Ottoman military officers and diplomats began pushing for Western-style reforms to strengthen their empire, the political leadership was concerned not to relinquish Shariah. History was the divinely directed movement from the rule of ignorance (jahiliyya), in the form of traditional tribal and monarchical rule, to that of knowledge, in the form of this Islamic state. During the Umayyad caliphate (660-750), the umma regressed toward human tendencies for rulership and became internally divided. During the Abbasid caliphate that followed (750,1258), writes Hourani, “the principles of the umma were reasserted and embodied in the institutions of a universal empire, regulated by law, based on the equality of all believers, and enjoying the power, wealth, and culture which are the reward of obedience.” Ever since, Sunni thinkers have looked to a restoration of the golden age rather than a progressive improvement in the human condition.18

Traditional Islamic theocracy was tolerant of the Jews and Christians who lived under its rule. Adherents of these older religions, whose sacred texts Muslims revered, were “people of the book,” with valid (if incomplete) divine revelation, entitled to their own worship and the ruler’s protection as long as they paid a special tax. In the mature Ottoman Empire, the Sultan invested Jewish and Christian leaders with political authority over their respective communities, granting them virtual autonomy in return for loyalty and the poll tax. But Islamic regimes were not secular in the modern sense: the ruler had the burden to enforce orthodoxy among Muslims.19

It was the slow but unmistakable decay of the Ottoman Empire that produced the crisis of the old theocratic order. Western ideas and institutions came to appear more attractive to Ottoman officials as imperial decline began to ensue in the seventeenth century. It was then that the economic and political effects of European colonization in Asia and the Americas came to be felt. Ottoman trade routes were disrupted and prices rose. The Turks had to import from the West military innovations such as firearms and fortification techniques. The notion began to take hold among many Turkish elites that Muslim greatness would return not with closer fidelity to the past but with the adoption of new technologies and practices of the now-predominant West. Eighteenth-century sultans tried piecemeal reforms. Selim III (r. 1789-1807) initiated a systematic reform of his military with help from French officers. Selim was overthrown by conservatives, but under his successor Mahmud II (r. 1808-39) there developed a cohort of military officers and diplomats with extensive contacts in Europe, determined to make the empire more Western in order to save it from Western domination. The empire must be centralized under rationalized administration, including a professional army officer corps and the equality of all subjects under the law.20

At the same time, among Arab elites ruled by the Ottomans Western ideas were taking hold following Napoleon’s 1798 conquest of Egypt. Muhammad Ali, Ottoman Viceroy of Egypt (r. 1805-48), carried out modernizations similar to those of Mahmud II, including legal equality for adherents of all religions. Arabs studied in Europe and became acquainted with Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, and other Enlightenment thinkers. Many of these Arabs were Christians from the Levant, and so their immediate effect on Islamic culture was limited. But as the century progressed, many Arab intellectuals—Muslim and Christian alike—began to argue that secularization was the route to an Arab revival. They brought the Western Enlightenment and its skepticism about traditional religion to the Arab world.21

Ottoman decay accelerated as the nineteenth century progressed. The threat of dissolution signaled by Greek independence in 1832 led the Empire’s rulers to attempt to modernize and rationalize their empire along Western lines. During the Tanzimat period (1839-76) the Sultan extended equal legal rights to all subjects regardless of religion, in hopes that the 25 percent who were not Muslim would have less reason to follow the Greeks’ lead. This liberalism was gradually reversed during the Hamidian period (1876-1908), which foreshadowed the full-blown Islamism that was to come later. Resurgent Western imperialism in the 1880s generated an Islamic reaction: it must be the case, reasoned many intellectuals, that infidels rule Muslims because Muslims have strayed from the correct path.22 These concerns, along with a desire to deflate growing Arab ethnic consciousness (itself due to Western influence), led Sultan Abdul Hamid (r. 1876-1909) to renew the traditional emphases on his role as caliph and the Islamic character of the empire.23 In some ways Abdul Hamid re-enacted the enlightened absolutism of eighteenth-century Europe (chapter 5) by attempting to centralize power and rationalize society based upon a religious claim to legitimacy. He built a railway from Damascus to Medina to facilitate pilgrims on the hajj.24 Although Jews, Christians, and other religious minorities continued to enjoy legal equality with Muslims, and the Sultan enjoyed little de facto authority over much of the empire outside of the cities, the regime remained a traditional theocracy, with Sultan as caliph and Shariah as law.25

By the turn of the twentieth century, traditional Islam’s political regime lay in ruins. Most of the Muslim world was divided among European empires: the French, Spanish, and Italian (North Africa), British (South Asia and Malaya and, with the Ottomans, Egypt and the Sudan), Russian (central Asia), and Dutch (the East Indies). Persia and Egypt were semi-autonomous and the Ottoman Empire itself continued its formal rule over most of the Middle East. But the empire continued to decompose. In 1878, under the Treaty of Berlin, Austria-Hungary had begun to administer Bosnia-Herzegovina; in 1881, France occupied Tunisia. Fearing dissent from Westernizing reformers, Abdul Hamid suspended the 1876 constitution, censored the press, and employed a secret police force. In response, reformers in the universities and military academies formed secret societies analogous to the old Italian carbonari (chapter 5).26 From Paris and Berlin, expatriate dissenters published pamphlets denouncing the Sultan’s backward autocracy.27 Dissenters were opposed to more than simply theocracy; the old religio-political institutions were one part of a more general problem with the Ottoman Empire. Their solutions comprised more than simply secularism, or separating mosque from state. But inasmuch as secularism entailed decreasing the power of clergy and the normativity of tradition, it was integral to their program of strengthening Muslim society against Western imperialism, and it proved the most polarizing aspect of that program.

One reformist secret society founded by Mehmet Talaat, Minister of the Interior, grew into the Young Turkey Party. A number of junior army officers, including Enver Pasha, joined the Young Turks, and in July 1908 the group seized power in Constantinople and imposed a constitutional monarchy, relegating the Sultan to a figurehead. The Young Turks were modernizers, committed to technological development, secularism, and nationalism.28 For several years they shared power with more liberal modernizers, and then took control of the Ottoman imperial apparatus. The Young Turks found in Germany a great-power sponsor to protect their empire from foreign attack. During the First World War they fought alongside the Germans and Austrians. The British, helped by Colonel T. E. Lawrence, tried to weaken the modernizing Ottomans by encouraging Arab nationalism, but a revolt by the Emir of Mecca in June 1916 failed.

Following the defeat of the Central Powers in November 1918, General Mustafa Kemal, the Ottomans’ hero of Gallipoli, assumed power over much of Anatolia. While the Allies met in London in February 1920 to decide the fate of the Ottoman Empire, Kemal consolidated power among Young Turks in the middle ranks of the army and Muslim clergy, who were unaware of his strong secularist leanings. Kemal revolted against the new Sultan and repeatedly defeated French forces fighting on the Sultan’s behalf. An anti-communist, Kemal nonetheless accepted aid from the young Bolshevik regime in Russia.29 Kemal abolished the 700-year-old Osmanli sultanate in 1922, and in October 1923 the Republic of Turkey was declared.

Kemal, later known to the world as Atatürk, not only ended the caliphate but carried earlier Westernizing reforms much further, aggressively weakening Islam’s influence in Turkish society. Writes William Cleveland: “Secularism was a central element in Atatürk’s platform, and the impatient Westernizer pursued it with a thoroughness unparalleled in modern Islamic history.” As a Turkish nationalist, Atatürk was by definition a secularist: nation-states had no place in traditional Islam. But he also took concrete steps to shrink the role of Islam in public life. He abolished the office of sheikh al-Islam, closed all religious schools, and abolished the government’s religious ministry. Sunday replaced Friday as the day of rest. Atatürk had the Quran translated into Turkish and required the calls to prayer to be in Turkish rather than traditional Arabic.30 He replaced Shariah with the Swiss Civil Code, banned the fez and discouraged the veiling of women, replaced the Arabic with the Roman alphabet for the Turkish language, and constructed a secular nationalist ideology, Kemalism. Although Islam was by no means banished, it was no longer to be a pole of loyalty to compete with the state; rather, it was under the control of the secular state. The ulema lost prestige and influence and their numbers dwindled.31

Atatürk’s cultural revolution enjoyed demonstration effects in much of the Muslim world, attracting admiration from intellectuals, lawyers, and military officers in country after country. It was in Iran, a country that had been relatively impervious to Western ideas in the nineteenth century, that Kemalism had its greatest immediate effects. During the First World War Iran had been occupied by British and Russian troops. The latter withdrew after the 1917 revolution but the British remained and sought to reorganize society to their advantage; much of the countryside was run by competing tribes. Reza Khan was a talented army colonel who seized power in February 1921. By 1926, he had become Shah and established the new Pahlavi dynasty.

Reza Shah (r. 1926-41), writes Cleveland, “borrowed many of his programs directly from the Kemalist experience.” He reformed and expanded Iran’s army and established a large state bureaucracy. Like Atatürk, Reza Shah was a thoroughgoing secularist. The scope of Shariah was reduced to family law, with a code modeled on the French governing civil disputes. State courts were created and their secular-trained judges given the power to decide which cases were in the jurisdiction of the ulema. The ulema themselves were now trained and licensed by the state, and the state founded the secular Tehran University to foster a non-religious intelligentsia. In the 1930s, laws were passed requiring men to dress like Westerners and forbidding women to wear the chador or veil. Iranian nationalism was emphasized, pan-Islamism discouraged.32

In the Arab world, however, such radical secularization was still decades away. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire led to the creation of the Arab states of Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Iraq, Transjordan, Hijaz, and Yemen. Only the last two enjoyed full independence in the Middle East; the others were League of Nations “mandates,” ruled by France or Britain until such time, said the League, as they could govern themselves. The typical pattern was for the British or French to strike bargains with local elites that involved some modernizing reforms but not the radical regime changes of Turkey or Iran. In the Levant, under French mandate, Lebanon was created as a “confessional” state, essentially secular but dominated by Christians (Maronite Catholics).33 Egypt gained nominal independence from Britain in 1922 owing to the efforts of the Wafd Party, an organization of landed gentry and lawyers, many of whom had been educated in Europe. From 1924 to 1936, Egypt was a constitutional monarchy whose parliament was dominated by the Wafd Party. Cleveland writes of the “diminution of religious values and religious institutions in the regulation of legal affairs and personal relationships” under Wafd governance. A liberal Egyptian elite flourished that emphasized the country’s pre-Islamic heritage (“pharaonism”) and its Mediterranean aspect. A robust feminist movement was founded in 1923.34

Traditional Islam remained predominant in the Arab world through the 1950s. In Jordan and Iraq, the House of Hashemite—which traced its lineage to the Prophet Muhammad’s tribe—ruled and kept in place traditional institutions. And Islamic resistance to modernization was flourishing on the Arabian peninsula. In 1902, Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud (1876-1953) had seized the city of Riyadh from the family’s rivals, the Rashidis. Over the next two decades, Ibn Saud conquered much of the peninsula, establishing the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (and erasing the Kingdom of Hijaz) in 1932. Ibn Saud’s success came not only from military prowess but also from the legitimacy conferred upon him by his status as head of the Wahhabi movement within Sunni Islam. In the eighteenth century, Abd al-Wahhab and the House of Saud had become permanently joined. Founded by Muhammad ibn abd-Al Wahhab (1703-92), Wahhabism has been compared to Calvinism in Christianity (see chapter 4). Wahhabists reject various accretions of tradition in Islam that, as they would have it, detract from pure monotheism. They reject any mediating role for saints between the believer and Allah. Claiming to recapture the primitive religion as revealed to the Prophet, they call themselves Salafists, or those who return to the earlier generations.35 Ibn Saud capitalized on this integral relationship by propagating Wahhabism to the tribes and requiring their shaikhs to attend a religious institute in Riyadh. In return he provided their tribes with farming supplies and weapons. Thus, Ibn Saud made local leaders loyal subjects with a transcendent mission: to spread the pure, rigorous Wahhabist form of Islam throughout the peninsula.36

At the same time, in those countries where secularism was making inroads, Islamists began quietly to mobilize in reaction. The ulema understood that secularization had a great deal of elite support, and so chiefly criticized its detrimental effects on Muslims’ piety. In Sunni Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood was founded in 1928 by Hassan al-Banna. Branches of the Brotherhood appeared in subsequent years in other Arab countries. The Egyptian Rashid Rida (1865-1935) founded a journal, al-Manar (The Beacon), urging the preservation of Islamic tradition. From Switzerland Amir Shakib Arslan (1869-1946), a Lebanese Druze exiled by the French, propagated the notion that freedom from imperialism would come with a return to traditional Islam. “A staunch opponent of Atatürk, Arslan wrote that the callous disregard of cultural tradition would undermine the spiritualism that made Eastern civilization superior to the shallow materialism of the West,” writes Cleveland.37 Among the Shii in Iran the young Ruhollah Khomeini and other clergy quietly taught and wrote against the Shah’s effacing of the divinely ordained order of society.38 These early Islamists proclaimed loyalty to their nation’s regimes and in general worked within the system for reform; like the secularists, they sought independence from European (i.e., infidel) colonialism. But their teachings were nonetheless subversive of the secularist project. Khomeini and other Shia Islamists practiced taqiyya, or dissimulation, to avoid persecution.39

Thus, in the second quarter of the twentieth century elites in many societies of the Middle East were polarizing over whether secularism or Islamism presented the better account of what success entailed and how to achieve it. Until the 1950s, however, neither secularists nor Islamists carried out any forcible regime promotions. Although rulers had some incentives to export their regimes, those incentives were outweighed by familiar incentives not to attack neighbors. Saudi Arabia was the chief exemplar of traditional Islam, but it was militarily weak. Secular Turkey and Iran were stronger, but the hegemony of outside powers—the British and French between the world wars, the Americans and Soviets after 1945—suppressed the possibility of Atatürk’s or the Shah’s using force to spread secularism. Things were to change, however, with the eruption of radical secular ideology in the Arab world in the form of Gamal Abdul Nasser’s regime in Egypt. Nasserism exacerbated polarization in Arab societies between traditionalists and secularists, making both more militant. Indeed, Nasser’s brutal suppression of the Muslim Brothers helped transform traditional Islamic resistance to secularism into militant Islamism. In so doing, Nasserism created threats and opportunities for the rulers of these societies.

Decolonization in the Muslim world following the Second World War ushered more secular regimes into the Muslim world. In British India, Muhammad Ali Jinnah had been inspired by Atatürk’s transformation and renewal of Turkish society.40 Jinnah went on to found Pakistan as a secular Muslim state, in which Islam was an ethnic marker rather than the comprehensive way of life it had traditionally been. In Arab societies secularism also took hold in the form of Arab nationalism. A diverse phenomenon, Arab nationalism, like Kemalism, sought to modernize Muslim societies by rationalizing administration and centralizing power in the state, which in turn entailed reducing the independent influence of the clergy. Like European nationalisms of the nineteenth century, Arab nationalism recognized a spiritual as well as material element, and was propelled among elites by a transnational set of intellectuals, including Taha Hussein of Egypt, Sati al-Husri of Yemen, and Michel Aflaq of Syria, founder of the Baathist (Renaissance) movement (and a Christian).41

Arab nationalism’s most important advocate was Nasser, who ruled Egypt from 1954 until 1970. Nasser had been an Egyptian army officer during Israel’s 1948 war with Arab forces. Following the Arabs’ defeat, Nasser and his clique of officers set out to modernize Egypt. The Muslim Brotherhood aligned with him out of common hatred of both British imperialism and Soviet communism, and cooperated in overthrowing the Egyptian monarchy in 1952 and establishing a new republic. But with the common enemy vanquished, the divergence of the secularist and Islamist visions for Egypt became difficult to ignore; each began to threaten the other. In January 1954, Nasser dissolved the Brotherhood.42 On the surface Nasser appeared to be strengthening Islam in Egypt by building more mosques, supporting al-Azhar University in Cairo, and making religion compulsory in school examinations. But Nasser altered traditional Islam by removing it from the control of the ulema and bringing it under the sway of the Egyptian state. He abolished the private Shariah courts in 1955.43 He successfully co-opted leading ulema and al-Azhar University, the ancient and prestigious center of Islamic scholarship. Following the general Muslim secularist line, Nasser recast Islam as a religion suitable for modern state-led development.44 As Barnett Rubin writes, “the regime did not abandon the potent power of religion to its enemies [the Muslim Brotherhood], seeking instead to re-interpret and dominate Islam as a pillar for its own rule.”45

Nasser’s early program concerned Egypt primarily, but he clearly saw advantages to the spread of his regime to other societies. When the Algerian war of independence broke out in November 1954, he provided support and training for the rebels in their struggle against the French. At the 1955 Bandung Conference that launched the Nonaligned Movement, Nasser was recognized as the leader of Arab anti-colonialism.46 His prestige rose further with his successful defiance (with American help) of the Israelis, British, and French in the 1956 Suez crisis. Nasser turned his humiliation of imperialists and Zionists to his advantage, and Nasserism became the leading form of pan-Arabism, enjoying momentum among intellectuals, military officers, and others throughout the Arab world, including within the conservative monarchies of the Arabian peninsula.47 Propaganda broadcasts from Radio Cairo called for the overthrow of corrupt and weak monarchical regimes.48 Nasserism was to find a kindred movement to Egypt’s east in Baathism, whose program was similar. In the republic of Syria, where a majority of army officers were Baathist, the government sought political union with Egypt. Nasser granted it and the United Arab Republic (UAR) was born on February 1, 1958.49

The sudden spread of Nasserism into Syria implicated the interests of the United States and Soviet Union and led to two forcible regime promotions. Already in the 1950s the Cold War had spread to the Middle East, with both superpowers courting rulers and political movements. The United States had organized the Baghdad Pact in February 1955, comprising Iraq, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, and Britain. Nasser sought to maintain a nonaligned stance, frequently consulting Tito of Yugoslavia for advice. He courted both the American and Soviet governments, seeking to extract maximum benefit by playing the two off against one another. It was a desire not to alienate Nasser and the Arab world in general that led Eisenhower to back Egypt in the Suez Crisis. Nasser also made the most of Khrushchev’s desire for the Soviet Union to lead the “wars of national liberation” (chapter 6). Notwithstanding Egypt’s putative non-alignment and Nasser’s persecution of Egyptian communists, he was anti-British and -French; insofar as his movement eroded Western influence, its spread was a net gain for the Soviet Union. On July 14, inspired by their confreres in Syria, Baathists in Baghdad carried out a coup d’état, overthrowing the Hashemite monarchy of Faysal II. Although Nasser was not involved in the coup, Iraqis waved his picture in victory parades and the new Iraqi rulers immediately asked that Iraq be allowed to join the UAR.50 The new Arab-nationalist Iraq quickly withdrew from the Baghdad Pact.51 The spread of secularism was a net gain for the Soviets and a corresponding loss for the Americans.

The Syrian accession to the UAR had demonstration effects in other Arab countries as well. In Jordan and Lebanon Arab nationalists began to press for regime change and membership in the UAR as well. Lebanon was not a traditional Islamic state but rather a republic with a secular regime dominated by Christians. Although Arab nationalism was not originally Muslim per se—Michel Aflaq, the Syrian founder of Baathism, was a Christian—Lebanese Muslims discontented with their subordinate status latched onto it as a formula for empowerment. When President Camille Chamoun refused to seek membership in the UAR, rebels seized large parts of Lebanese territory and demanded Chamoun’s resignation. Chamoun requested U.S. intervention, and on July 15, U.S. Marines began to land on Lebanese beaches. Around 10,000 U.S. forces eventually arrived.52 Jordan’s monarchy, being of the same Hashemite dynasty as Iraq’s had been, was in deeper jeopardy. King Hussein asked for British intervention, and on July 17-18 some 2,400 British paratroopers entered the country to safeguard the regime.53 Saïd Aburish writes that “there is little doubt that both countries would have fallen to pro-Nasser forces without the American and British presence.”54

Just as Lutheranism and Calvinism prodded Catholicism to become more mobilized and militant (chapter 4), Nasserism prodded traditional Islamists into a more assertive and precise ideology. Islamism became more militant through two overlapping pathways—one through rulers who formed and ran networks, particularly the Saudi dynasty, and another through the transnational Muslim Brotherhood.

King Saud (r. 1953-64) was quick to see the threat that Nasserism posed to his own Islamist regime. For decades the desert kingdom was famously closed to the outside world, but the discovery of oil led to its partial opening at the elite level. Requiring trained engineers and civil servants loyal to the regime, the Saudi government in the 1950s began sending young men to Europe and North America to study and young military officers to train in Egypt. These returned to Saudi Arabia not only with technical expertise but also with secularist political ideas. In 1955, a group of Egyptian-trained Saudi military officers plotted to overthrow the monarchy, just as Nasser had done in Egypt three years earlier; the plot was foiled but sent shock waves through the royal family.55 Notwithstanding this ideological threat, for several years Saud cultivated good relations with Nasser out of common opposition to the Hashemite dynasty that ruled Iraq and Jordan (a competitor with the House of Saud for prestige among Muslims). Saudi-Egyptian relations deteriorated sharply from late 1956, as Saud began to see that Nasser’s persecutions of the Muslim Brothers and socialist pan-Arab vision contradicted his dynasty’s entire system. Saud began to tilt toward the Hashemites as potential allies against Nasserism, and in 1957 he visited King Faysal II in Baghdad. The following year, when Faysal was overthrown by allies of Nasser (see above), an attempt by a Syrian to assassinate Nasser was traced to the Saudis.56

The Saudis continued to go on the ideological offensive in the early 1960s, organizing an anti-revolutionary bloc to subvert the secularist regimes. 57 In May 1962, Saudi Prince Faysal organized a conference at Mecca to discuss how to combat secularism and socialism. The result was the Muslim World League, an international educational and cultural organization. The League ever since has promoted Wahhabism around the world. Working through Saudi embassies, the Muslim World League has supported Muslim Brothers in various Arab countries and Islamist movements in South Asia and Africa. It has combated Nasserism, Baathism, and other secular movements as well as Sufism and other forms of Islam considered heretical by Wahhabis. In 1972, the Saudis founded the World Assembly of Muslim Youth, which works among young Muslims to serve the same purposes.

Perhaps the most lasting consequence of Nasserism was its radicalization of the Muslim Brotherhood. Nasser imprisoned and tortured many Muslim Brothers. (The Saudis interceded with Nasser on behalf of many and gave asylum to those who fled Egypt.)58 Among the imprisoned was Sayid Qutb (1906-66), the movement’s leading intellectual.59 Qutb spent most of the last twelve years of his life in prison and was ultimately hanged for treason in 1966. His time in prison, along with his earlier years of study in the United States (1948-51), led him to elaborate a deep critique of modern secular society as a version of paganism. “Our whole environment,” wrote Qutb, “people’s beliefs and ideas, habits and art, rules and laws—is jahiliyah [infidelity or ignorance] even to the extent that what we consider to be Islamic culture, Islamic sources, Islamic philosophy, and Islamic thought, are also constructs of jahiliyah.”60

Required, argued Qutb, was a return to pure Islam, meaning a strict, literal application of Shariah to society. In turn, this return required the formation of a force capable of pushing back the secular juggernaut:

The Muslim society cannot come into existence simply as a creed in the hearts of individual Muslims, however numerous they may be, unless they become an active, harmonious, and cooperative group, distinct by itself, whose different elements, like the limbs of a human body, work together for its support and expansion, and for its defense against those elements that attack its system. This group must work under a leadership that is independent of the jahiliyyah so it can organize its various efforts in support of one harmonious purpose, and strengthen and widen the Muslims’ Islamic character in order to abolish the negative influences of jahili life.61

Following Qutb’s execution in 1966, the Muslim Brothers debated precisely what Qutb meant for this separate, pure entity to do: to work within existing institutions, or to overthrow and replace them? The separatism of Qutb, however, was clear. Pious Muslims could no longer continue to participate in secular, impious society.62 The years of secularist triumph were in fact years of deep, quiet polarization within Egypt, in which Islamists and secularists became mortal enemies.

With Islamism no longer simply a conservative way of life but now a vibrant competing ideology, it was to pull the Egyptians and Saudis into competing forcible interventions in North Yemen. In September 1962, Imam Ahmad died and his son Muhammad al-Badr assumed the throne. Junior army officers, aided by the Nasser government, quickly deposed al-Badr and declared a Yemeni Arab Republic. Egyptian troops began to pour into Yemen to support the republic against al-Badr’s forces; by the middle of 1963, 30,000 Egyptian soldiers and advisers were in country; by the next year the number had swollen to 40,000.63 The Saudis saw the young secular republic on their southern border as a sign that Nasserism was spreading and responded by arming the royalists. As Paul Dresch writes, “a fiery front dividing the whole Arab world now ran through Sanaa with on one side the Arab monarchies, most importantly Saudi Arabia, and on the other Egypt.”64 The Cold War and European colonialism were overlaid onto the conflict. The British, who ruled southern Yemen and were fighting an insurgency there (chapter 6), joined the Saudis in supporting the Yemeni royalists. In November, Nasser announced the formation of a National Liberation Army to liberate Yemen from al-Badr’s forces. The war was to persist until 1970. (The Yemeni civil war’s demonstration effects helped trigger a rebellion in the Dhofar region of neighboring Oman; the Dhofar revolt took a Marxist turn and is treated in chapter 6.)

Although the Islamists—the Saudis, the Muslim Brotherhood—were fighting back, there is no question about secularism’s forward momentum during these years. Secularist governments could suppress Islamists and risk driving some of them toward radicalism because Islamist ideas had little purchase in the universities or among average people. In the words of Kepel: “At that time it was thought—mistakenly—that secularization was a straightforward, unstoppable process, in the Muslim world as elsewhere. Islam was regarded as an outmoded belief held only by rural dotards and backward reactionaries.” Most dissenters from these regimes latched onto Marxism-Leninism, not Islam, and criticized the governments for betraying socialism.65

In June 1967 Nasser finally overreached, and secularism in the Muslim world has never recovered. Intending to demonstrate his secular pan-Arabism’s superiority once and for all, Nasser and the governments of Syria and Jordan determined to destroy Israel, reversing the humiliation that the weak traditional Arab regimes had suffered in 1948. Israel’s stunning defeat of these three larger nations showed that the balance of power in the Middle East was not as all had supposed: under Nasser’s leadership the Arabs remained weaker than tiny Israel. Waiting in the wings to articulate the crisis and prescribe a solution were the Islamists, who had been predicting Arab socialism’s failure all along. The Muslim Brothers propagated their narrative that the fundamental problem was that Muslims had abandoned the true path, and the fundamental solution was Islam—not Nasser’s Hobbesian version of a religion run by a secular state, but pristine Islam, untainted by ideas and institutions from the West. Writes Kepel: “A fault line—initially secular in origin—then opened up across the various societies concerned, demolishing the political consensus which had experienced no such shock since independence.”66 James Piscatori adds several other mechanisms for the supplanting of secularism by Islamism: the modernizing process itself uprooted people, chiefly by encouraging them to move from the countryside to cities such as Cairo, Damascus, and Tehran, and Islamism provided them with moral and material support; modernization simultaneously increased the ability for elites to communicate and mobilize actors, which benefited Islamists; and, in order to co-opt devout Muslims, all along the secularists had used Islamic language and symbols to legitimize their rule, thereby implicitly acknowledging the normative power of the religion in public life.67

The sudden weakness of the secularists is clear in their attempts to embrace certain aspects of traditional Islam. Nasser’s and other Arab secularist regimes struck a new bargain with the Islamists: they would halt their secularizing efforts at home and abroad in return for Saudi aid and a united Arab front against Israel. The Arab League summit in Khartoum, August 29-September 1, 1967, ended in the famous “three noes” declaration: no peace with, recognition of, or negotiations with Israel.68 Nasser withdrew Egypt from Yemen and ceased all efforts to destabilize Islamist regimes.69 His protégé and successor Anwar Sadat, who took power in 1970, went further and lifted the ban on the Muslim Brotherhood, assumed the title “Upholder of the Faith,” claimed that his first name was Muhammad, and supported religious instruction in the schools.70

Sadat also tried to vindicate Arab secularism by combining with Syrian forces in attacking Israel in October 1973. Although Israel won this war too, in the early stages Arab armies repulsed Israeli forces, restoring some measure of Arab pride. Even so, Islamism emerged from the 1973 war still stronger owing to war’s role in strengthening the Saudis, who tripled the price of oil and thereby transferred massive wealth from the West to the oil-producing states. By bidding fair to end Western predominance altogether, Saudi Arabia finally supplanted Egypt as the Arab exemplar. Before the 1970s, Egypt was generally thought of as progressive, Saudi Arabia as backward. By the late 1970s, writes Kepel, the roles had reversed: “Islam, championed by the Saudis, was a synonym for victorious confrontation with Israel, America and their allies.”71 Young and disaffected Arabs across states began to turn to Islam, the Muslim Brotherhood, and writers such as Qutb. Islamic charities appeared in the urban shantytowns; Islamic educational organizations began to supply materials to distended, under-funded universities. By the late 1970s, Islamists had begun to challenge secularist regimes from within. In 1977, Sadat had to suppress an Islamist rebellion in Egypt.72

The momentum of Islamism was also aided by expanded Saudi promotion of Wahhabism. Sharply increased rents from oil following the OPEC embargo in 1973 allowed the Saudis to pour massive amounts of money into the World Muslim League. As David Commins writes:

By the time of King Faysal’s assassination [by a relative seeking revenge] in March 1975, he had put Saudi Arabia at the center of a robust set of pan-Islamic institutions, contributed to a new consciousness of international Muslim political issues, ranging from Jerusalem to Pakistan’s troubles with India over Kashmir to the suffering of South Africa’s Muslims under the apartheid regime.73

The bargain between the Saudi royals and the ulema who propagated Wahhabism worked well for both: the House of Saud relied on the ulema for legitimacy; the ulema, on the royals for money and protection.74

Not all Arabs agree that secularism had failed in 1967; committed secularist elites argued instead that Nasserism had not been sufficiently radical. They insisted that reviving Islamic tradition was precisely the wrong route to Arab greatness. This view predominated among one crucial group, Palestinian elites, for another two decades.75 Palestinian nationalism, which emerged in reaction to Jewish settlements in Palestine in the early twentieth century, has too complex a history to explore here. Mehran Kamrava writes that it was eclipsed by Nasserism from 1952 to 1967, but after the Israeli war victory in June 1967, Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) became predominant. The PLO, itself dominated by the al-Fatah movement, is explicitly secularist owing in part to its determination to include Christian Arabs.76 Its declarations state that the PLO aims to build a Palestinian state where Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others are equal; its stated objection to Israel is that it is a Jewish state.77 It is difficult to divine the precise regime that Arafat intended to build in the 1970s, because ideological statements were vague owing to the need to build consensus among various Palestinian factions and to recruit Muslim and world opinion to the cause. Official PLO declarations named “secular democracy” as their favored regime. The chief in Beirut stated that the PLO had in mind “not a liberal democracy according to the one man-one vote system” but “popular democracy,” meaning in the language of the time a single-party leftist regime.78 Thus, the PLO fits within the secular, Arab nationalist category.

Because the Palestinians had no territorial state during this period (and still have none at the time of this writing), we do not count as forcible regime promotions Israeli incursions into the West Bank or Gaza. In 1975-76, however, civil war in Lebanon raised the possibility that Arab nationalism, in the form of a PLO-dominated regime, would take over that country and replace its Christian-dominated secular regime. The Lebanese were divided into a number of factions, but when Christian Phalangists killed a busload of Muslims in April 1975, the population polarized and Muslims rallied to the PLO. Outside powers quickly became involved. Israel used direct force by blockading the coast to prevent support from reaching the PLO-Shia coalition. When the latter nonetheless began to win the war in early 1976, Syrian President Hafez al-Assad—himself a Baathist—began to fear an Israeli invasion to block regime change. In a complex move, Assad sent 20,000 troops and 450 tanks into Lebanon to prop up the regime. The regime in the end survived, although a de facto partition was in place from 1976; the southern part of Lebanon was effectively ruled by Shia, Druze, and Palestinian forces.79

Those forces continued to harass northern Israel, and Israeli forces invaded Lebanon in 1978, 1980, and 1982, the last with a large force of 60,000. These interventions were intended not to alter or preserve Lebanon’s regime but to weaken or destroy the PLO and to install a Lebanese government to take a harder line against the PLO and Shia militias and sign a peace treaty.80

Through the late 1970s the Islamist side of the transnational ideological contest was dominated by Sunnis, owing to Saudi patronage and the Muslim Brothers. With the Iranian Revolution of 1979, Shia Islamism was to bid to supplant Sunni Islamism. Shia-Islamist networks had spanned Iraq and Iran, and their victory in the latter produced a regime that contrasted with the Sunnis’ chiefly in its attitude toward America’s presence in the Middle East. Whereas the Sunni Islamists were more pro-American (and anti-Soviet), the Shii Islamists were decidedly anti-American.

The Sunni-Shia division has often bedeviled Islamism since its emergence in events following the death of Muhammad in A.D. 632. On the whole, Sunni and Shia Islamism are ambivalent regarding one another. Some Islamists of one branch will openly admire the other when it is fighting secularism elsewhere; thus the (Sunni) Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt praised the (Shia) Khomeini revolution in Iran in 1979. But other Islamists in each branch adamantly oppose the other. Their points of contention may seem trivial to outsiders, especially since Sunni and Shia both regard the Koran and hadith (sayings and actions of Muhammad) as authoritative. But these sacred sources require interpretation, and the theories of authority that divide the two branches mean they cannot agree on who is entitled to interpret or apply Shariah. Sunnis (from the Arabic for “tradition”) assert that the Prophet Muhammad left it to his disciples to choose his successor or caliph. SunniIslam has developed a consensual model of legal interpretation: scholars designated by the ruler are authorized to say what divine law implies for society today.

Shii claim, by contrast, insist that there is an imam, an infallible interpreter of the divine law, and only a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad may be an imam. Muhammad named as his heir his son-in-law Ali (Shia literally means “follower,” as of Ali). With the disappearance of the Prophet’s lineage, Shii have had to formulate provisional accounts of authority. As a practical matter, modern Shii allow fuqaha (jurists) to act as the imam’s surrogates, but consensus among fuqaha must include an imam’s infallible opinion. For the sub-branch known as Twelver Shiism, the Twelfth Imam went into hiding in A.D. 874 and will reappear as the Mahdi or messiah to end injustice on earth.81 The Shii’s strong notion of clerical authority has made them much more reluctant than the Sunnis to accept rule by laity. For most of Muslim history, the caliphate was Sunni and the Shii had to submit to a regime they regarded as heretical. Even within Shia realms—such as the Safavid Dynasty that ruled Persia from 1501 to 1742—a secular ruler was recognized by the clergy or ulema as the deputy of the imam and hence legitimate.82 Sunnis and Shii are both geographically concentrated, with Shii predominant in Iran, Azerbaijan, southeastern Iraq, Bahrain, and parts of Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, and Afghanistan. Pockets of Shii exist elsewhere in southwest and south Asia, but most of the rest of the Muslim world, including North Africa and Southeast Asia, is Sunni.

It is not entirely clear how far Sunni and Shia Islamists have influenced one another. As a young scholar, Ali Khamenei, currently Supreme Leader of Iran, translated a work of the Sayid Qutb into Persian.83 In turn, the writings of Ruhollah Khomeini and Ali Shariati, another Iranian, have influenced Sunni Islamists in various countries. The influence of Sunni Islamism on the Iranian Revolution of 1979 is hazy and indirect.

Iran’s conservative ulema had supported the U.S.- and British-sponsored overthrow of the secularist government of Muhammad Mosaddeq in 1953, and their relations with the Shah were cooperative in the 1950s. The Shah and the ulema were both anti-communist and anti-Baha’i (Bahaism is an offshoot of Islam). They had fundamentally different visions for Iran, however, and different attitudes toward the West and the United States in particular: the Shah saw aligning with America as the route to development, while the ulema saw America as a carrier of impiety and hence alignment with it as a road to ruin. The difference sharpened in the early 1960s. The Kennedy administration, aiming to reduce the appeal of communism throughout the Third World, began to press friendly authoritarian governments to redistribute land to their countries’ peasants. In Iran, the religious establishments were among the major landowners, and the ulema protested. Ruhollah Khomeini began to emerge as an Islamist leader. The Shah’s government, seeking to weaken the ulema, proposed further reforms including female suffrage and office-holding by non-Muslims. In March 1963, the Shah suppressed dissent at various mosques; in June he imprisoned Khomeini, released him, and imprisoned him again. Upon his release Khomeini denounced the Shah and his close relations to the United States. He was re-arrested and exiled.84 From Turkey, Khomeini went to Iraq in 1965, where he continued to develop his version of Islamism:

Islam has a system and a program for all the different affairs of society: the form of government and administration, the regulation of people’s dealings with each other, the relations of state and people, relations with foreign states and all other political and economic matters…. The mosque has always been a center of leadership and command, of examination and analysis of social problems …

he declared in a typical sermon in Najaf.85

As mentioned at the outset of this chapter, Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s secularist dictator, and the Shah had come to see enough common interest in suppressing Khomeini’s movement that they began a rapprochement in 1975, and in 1977 Saddam agreed to the Shah’s request to expel Khomeini from Iraq. The revolution against the Shah began in late 1978 as a coalition among diverse anti-Shah elements, including liberals and communists. When Khomeini arrived from Paris in January 1979, he began to seize the revolution and use it to build a faqih or clerical theocracy. Indeed, like the Girondists in 1792 (chapter 5) and the Bolsheviks in 1917 (chapter 6), the Khomeinists recognized the potential of foreign demonstration effects to strengthen their grip on power at home. They sought to foment Islamist insurrections in many countries and to transcend the Shia-Sunni (and Persian-Arab) divide by using nonsectarian language.86 Proclaimed Khomeini in December 1979: “Islam is not peculiar to a country, several countries, a group [of people or countries], or even the Muslims. Islam has come for humanity. Islam addresses the people and only occasionally the believers. Islam wishes to bring all of humanity under the umbrella of its justice.”87 From Tehran was broadcast the Arabic-language “Voice of the Islamic Revolution,” urging Muslims everywhere to overthrow their governments.88

Demonstration effects were clearest among the Shii in other lands, and most alarmed were those Arab rulers of countries with significant Shia populations, namely Iraq, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Lebanon. A wave of unrest hit these countries and was met with a wave of repression. In Bahrain, a majority of whose population was Shia, the Islamic Front for the Liberation of Bahrain attempted a coup against the monarchy in December 1981; seventy-three alleged plotters were arrested.89 Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, whose population is roughly one-third Shia, experienced some unrest, as did Kuwait, with a similar percentage of Shii.90 The Khomeinists saw Lebanon, whose population was approximately one-third Shia, as one of their most promising targets.91

The Iranian revolution’s effects among Sunni Islamists were more complex. Those who operated outside of state apparatus—the Muslim Brothers—tended to support the Khomeinists. In Egypt, the Brothers declared that all Muslims were duty-bound to support Khomeini’s movement. Fathi Abd al-Aziz published Khomeini: The Islamic Alternative, which declared that Khomeini’s revolution was not an attempt at Shia predominance, but concerned the beliefs common to all Muslims.92 The Islamic Student Association (al-Jamaah al-Islamiyyah) at Cairo University gave its unqualified endorsement.93

The Khomeini Revolution thus intimidated secularist rulers of Sunni societies. Anwar Sadat of Egypt, like Saddam Hussein, at first tried to conciliate the new Tehran regime in hopes of helping the moderates prevail in seizing the revolution back from the Khomeinists. But Sadat’s warm reception of the Shah in January 1979 immediately alienated Islamists throughout the Muslim world. When Mehdi Bazargan fell in Tehran in November, writes R. K. Ramazani, it “unleashed the ideological crusade of the Khomeini regime against Egypt.” The radicals in Tehran depicted Sadat’s regime as un-Islamic, like that of the Shah.94 Sadat was particularly vulnerable to Islamist criticism because in recent years he had turned on the Muslim Brothers and, in 1978, had signed a peace treaty with Israel. During these years Mohammed Adb al-Salam Faraj wrote “The Absent Duty,” arguing that a Muslim’s first duty was to work not to “liberate” Jerusalem but to topple his country’s apostate government. Faraj helped plan the assassination of Sadat in 1981. “ ‘The Absent Duty’,” writes Fawaz Gerges, “became the operational manual of the jihadist movement in the 1980s and remained so through the first half of the 1990s.”95

In Libya, Tunisia, and Sudan, all of which had secular regimes, society was polarized as Islamists were encouraged by the Iranian revolution. Events in Tehran also impressed millions of Muslims in Southeast Asia and Western Europe, leading to some conversions from Sunni to Shia Islam.96 But the Khomeinists were not able to exploit these Sunni movements.97

Crucial to the long-term shape of the secularist-Islamist struggle was the response of the Saudis, the long-time Islamist exemplars, to the Khomeini revolution. That response was hostile. To the Saudis, Khomeini’s Iran was a latecomer and a heretical usurper.98 Iran’s assertive anti-Americanism was an open challenge to the Saudis’ longtime pro-U.S. foreign policy. Like the deposed Shah, the Saudis had struck a bargain with the United States after the Second World War on ensuring stable energy prices and limiting Soviet influence in the region. Because Soviet communism was atheistic and menacing to Islam, as seen by its rule of historically Muslim societies in Central Asia, the Saudis could simultaneously be Islamist and pro-Western. Indeed, the Shah and the Saudis had cooperated to contain Arab nationalism in the Persian Gulf.99 Ramazani sums up the differences between Iranian and Saudi Islamism as follows: “clericalism versus monarchism; populism versus elitism … Shiaism versus Suniism; and anti-Westernism versus pro-Western nonalignmentism.”100

Hence, the Khomeini regime in Tehran was a double challenge to the Saudis. It was stirring up the Shii in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, and attempting to erode Saudi influence throughout the Muslim world by supplanting the House of Saud as vanguard of Islam. The Khomeinists began accusing the Saudis of degeneracy, elitism, and toadying to America and Israel. Tehran’s Arabic-language radio network began broadcasting messages of this sort:

The ruling regime in Saudi Arabia wears Muslim clothing, but it actually represents a luxurious, frivolous, shameless way of life, robbing funds from the people and squandering them, and engaging in gambling, drinking parties, and orgies. Would it be surprising if people follow [sic] the path of revolution, resort to violence and continue their struggle to regain their rights and resources?101

The Saudis responded by portraying the Iranian Revolution as “outside the mainstream of Islamic culture” owing to its Shiism and disrespect for legitimate authority.102

Tehran’s propaganda had an effect: In November 1979, Sunni militants seized the Grand Mosque at Mecca during the hajj or annual pilgrimage, repeating Khomeini’s line that the Saudi monarchy was counterfeit Islamic.103 The Iran-Iraq War, however, by pitting a Shia- against a Sunni-ruled (if secular) regime, reduced Sunni sympathy for the Iranian republic. Iran began to appear less an instrument of the Islamic revival and more one of Shia or Persian imperialism.104 Most Sunni Islamists still revered the Saudi monarchy at this point and saw the Khomeinists as upstarts—admirable for their overthrow of the apostate Shah, but still heretics unfit to unite the ummah.105 On the governmental level, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), comprising Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates—Sunni monarchies all—formed in May 1981 and cooperated to block Shia-Islamist subversion and Iranian predominance. The GCC’s formation further polarized Sunni and Shia, and in December Khomeinists attempted a coup d’état in Bahrain. The Saudis openly condemned the Iranians for engineering the coup attempt and sent agents to Bahrain to interrogate suspects. In February 1982, two GCC ministerial meetings were held, the second declaring the “intervention by any country in the internal affairs of one of the member states is considered to be intervention in the internal affairs of the GCC states [as a whole].”106 The GCC came to cooperate with the governments of Jordan and Egypt, as well as the United States, in aiding Iraq; Shia-ruled (secularist) Syria, on the other hand, aided the Iranians.

At roughly the same time as the Shia-Islamist resurgence in Iran, Sunni Islamism was surging to Iran’s east, in Pakistan and Afghanistan, further complicating international relations in the region and more broadly. The ideological surge followed top-down secularizing, centralizing programs from governments—a communist one in Afghanistan, and a non-communist one in Pakistan. In Pakistan the rise of Islamism involved increasing influence for a movement that originated in the nineteenth century in Deoband, a city north of Delhi in British India. The Deobandi sought to return Muslims to strict practices concerning dress, worship, and behavior; they rejected various accretions of tradition such as “what they regarded as excesses at saints’ tombs, elaborate lifecycle celebrations, and practices they attributed to the influence of the Shia.”107 Most Deobandi opposed the formation of secular Pakistan in 1947, preferring instead to cultivate a pure parallel Muslim society within a secular India; some splinter groups disagreed.108 The Deobandi were not a significant political force until the 1970s, when the transnational Islamic resurgence hit Pakistan. President Z. A. Bhutto, a secular socialist, was overthrown in 1977 by General Zia ul-Haq, a devout Muslim who proceeded to “re-Islamicize” Pakistan as a way to combat Soviet influence. Zia gave state certification to the madrassas (Islamic schools) and infused them with anti-communist jihadism; in 1975, only 100,000 taliban (students) were in these schools, but in 1977 the number grew to approximately 540,000. The resulting surfeit of mullahs contributed to the proliferation of state-supported Shariah courts.109

Early Deobandism had no evident connection to Saudi Wahhabism. But the programs of the two were similar, and the Saudi-sponsored World Muslim League poured funds into Zia’s re-Islamicization project. Wahhabi-Deobandi cooperation was to accelerate and expand in Afghanistan. In April 1978, the secularist regime of Muhammad Daoud Khan was overthrown by Nur Muhammad Taraki of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), a Soviet-sponsored communist party. Taraki’s efforts to remake Afghanistan rapidly into a modern communist society, including land redistribution and the education of women, generated deep resistance among the devout peasantry. Under the influence of religious elites, the resisters began to identify the problem as atheistic communism and the solution as fidelity to Islam. Burhanuddin Rabbani, a philosophy professor at Kabul University who had studied at al-Azhar in Cairo, quickly organized the National Rescue Front, comprising nine Islamic organizations.110 As Anthony Arnold writes, “Rural resentment had already become resistance; resistance was becoming rebellion; and rebellion showed signs of becoming jihad, a holy war against the infidel Kabul regime.”111 By August 1979, an estimated 100,000 Afghan refugees were in Pakistan. The Zia government refused to return the refugees, and relations between Islamabad and Kabul quickly soured.112

Taraki’s Soviet sponsors worried that the Islamist resistance was a tool of Zia’s regime and, since Pakistan was aligned with the United States, linked to American and Chinese efforts to weaken the Soviet Union. Islamism was hurting the Soviets in Afghanistan and had the potential to polarize and destabilize Soviet Central Asia.113 As the KGB Chairman for Soviet Azerbaijan put it shortly after the Soviets invaded: “In view of the situation in Iran and Afghanistan, the U.S. special services are trying to exploit the Islamic religion—especially in areas where the Moslem population lives—as one factor influencing the political situation in our country.”114 The communists suspected Khomeini of engineering a savage uprising in March 1979 in Herat, a Persian-speaking Afghan city near the Iranian border. Mobs butchered scores of communists, and as many as a hundred Soviets were killed. Khomeini vigorously denied any involvement, but did warn Taraki that he must reverse his anti-Islamic policies or suffer the Shah’s fate.115 Over the course of the 1980s, Tehran and the Pakistani and Afghan Islamists were to become increasingly hostile over the status and future of Afghanistan’s sizeable Shia minority.116

On December 25, 1979, thousands of Soviet tanks rumbled into Afghanistan to try to preserve the PDPA regime and thereby Soviet influence in Southwest Asia. The Soviet invasion increased ideological polarization in the region, heightening Muslims’ identification with one another across state borders against a common atheistic foe.117 The Sunni Islamists of Pakistan and Saudi Arabia responded predictably. With encouragement from the Saudis, Arab Islamists from all over North Africa and the Middle East went to Afghanistan to wage jihad against the communist invaders. Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) was delighted not only at Saudi financial help and propaganda but also at the demonstration effects in Kashmir, a Muslim Indian province claimed by Pakistan.118 Indeed, the ISI was under the influence of Pakistani Islamists who saw the struggle in Afghanistan as linked to their own struggle against Pakistani secularists in the Foreign Ministry and, beyond that, to their efforts to claim Muslim Kashmir from India.119 The ISI was in charge of distributing Saudi money to the Afghan mujahideen and also directed their military operations. In 1987, Islamists received more than two-thirds of the weaponry the ISI distributed.120 Indeed, some Saudi aid ended up in the hands of Pakistani Islamists near the Afghan border.121 General Hamid Gul, who headed the ISI in 1988 and 1989, later made clear that he favored the Islamicization of Pakistan and supported the Taliban in its fight against the United States and its allies.122

The conflict in Southwest Asia was overlaid with the Cold War (chapter 6). As early as the spring of 1979, prior to the Soviet invasion, U.S. intelligence did discuss aiding the mujahideen (Islamist “strugglers”) with Pakistan’s ISI, and the Saudis proposed a joint program with the CIA and the Afghan rebels.123 Under the Reagan administration, CIA cooperation with Sunni Islamists greatly expanded. The Chinese government was also involved in the general effort to stymie the Soviets.

The Soviets failed and finally withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989. Over the next decade there followed a sustained period of energy, expansion, and radicalization among Sunni Islamists. An uprising by Islamists in Algeria led to a long, savage civil war. In Sudan and Afghanistan, Sunni Islamists succeeded in setting up regimes. Events in all three countries had demonstration effects, but none led to a forcible regime promotion. Following independence from France in 1962, Algeria had a secular, left-wing regime. The next year Islamists, influenced by the writings of Sayid Qutb, organized to propagate Islamic values. Islamism simmered and expanded in Algeria, and in October 1988 urban riots began, the rioters identifying with Islamism and the Afghan mujahideen. The following year the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) was founded; in June 1990, the FIS dominated local elections, and in December 1991 it won the first round of parliamentary elections. The army cancelled the second round (to the relief of secularists throughout the Muslim world and beyond) in January 1992 and arrested thousands of FIS members. The FIS rebelled, and civil war raged with varying intensity for the rest of the decade. The FIS was divided within itself between the devout middle class and the urban poor; the latter formed the Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA) and included veterans of the Afghan wars. Kepel writes of the demonstration effects of the Algerian civil war: