Chapter 6. Peak–End Rule

People judge an experience largely based on how they felt at its peak and at its end, rather than on the total sum or average of every moment of the experience.

Overview

An interesting thing happens when we recollect a past event. Instead of considering the entire duration of the experience, we tend to focus on an emotional peak and on the end, regardless of whether those moments were positive or negative. In other words, we remember each of our life experiences as a series of representative snapshots rather than a comprehensive timeline of events. Our feelings during the most emotionally intense moments and at the end are averaged in our minds and heavily influence how we assess the overall experience to determine whether we’d be willing to do it again or recommend it to others. This observation, known as the peak–end rule, strongly suggests we should pay close attention to these critical moments to ensure users evaluate an overall experience positively.

Origins

Evidence for the peak–end rule was first explored in the 1993 paper “When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End” by Daniel Kahneman et al.1 They conducted an experiment in which participants were subjected to two different versions of a single unpleasant experience. The first trial involved participants submerging a hand in 14°C water (roughly 57°F) for 60 seconds. The second trial involved participants submerging the other hand in 14°C water for 60 seconds and then keeping it submerged for an additional 30 seconds as the water was warmed to 15°C. When given the choice of which experience they would repeat, participants were more willing to repeat the second trial, despite it being a longer exposure to the uncomfortable water temperatures. The conclusion by the authors was that the participants chose the longer trial simply because they preferred the memory of it in comparison to the first trial.

Subsequent studies would corroborate this conclusion, beginning with a 1996 study by Kahneman and Redelmeier2 that found that colonoscopy or lithotripsy patients consistently evaluated the discomfort of their experience based on the intensity of pain at the worst and final moments, regardless of length or variation in intensity of pain within the procedure. A later study by the same researchers3 expanded on this by randomly dividing patients into two groups: one that underwent a typical colonoscopy, and another that underwent the same procedure in addition to having the tip of the scope left in for three extra minutes without inflation or suction. When asked afterward which they preferred, patients who underwent the longer procedure experienced the final moments as less painful, rated their overall experience as less unpleasant, and ranked the procedure as less aversive in comparison to the other participants. Additionally, those that underwent the longer procedure were more likely to return for subsequent procedures—a result of these participants judging the experience positively because of the less painful end.

Examples

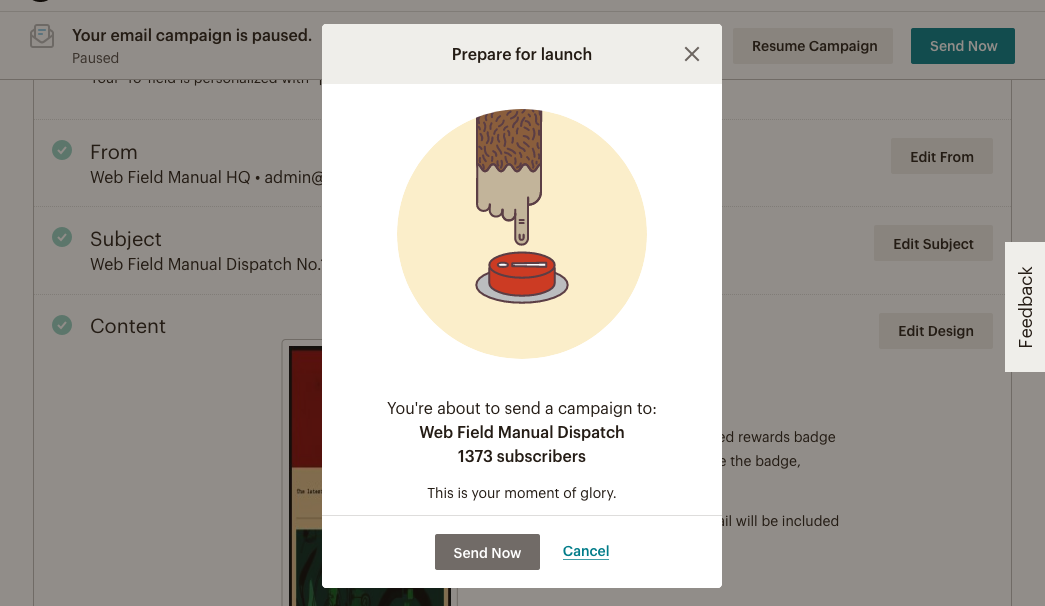

One company that demonstrates proficiency in understanding how emotion impacts user experience is Mailchimp. The process of creating an email campaign can be quite stressful, but Mailchimp knows how to guide users while keeping the overall tone light and reassuring. Take, for example, the moment when you’re about to hit Send on an email you’ve crafted for your audience’s inboxes. This peak emotional moment represents the accumulation of all the work that has gone into that email campaign, compounded by the potential fear of failure. Mailchimp understands this is an important moment, especially for first-time users, so it goes beyond presenting a simple confirmation modal (Figure 6-1).

Figure 6-1. Mailchimp’s email campaign confirmation modal (source: Mailchimp, 2019)

By infusing a touch of brand character through illustration, subtle animation, and humor, the tool defuses what could potentially be a stressful moment. Freddie, the company’s emblematic chimp mascot, hovers his finger over a large red button as if to imply he is eagerly awaiting your permission. The longer you wait, the more nervous Freddie seems to get, which is evident through the beads of sweat that appear on his hand and subtle shaking.

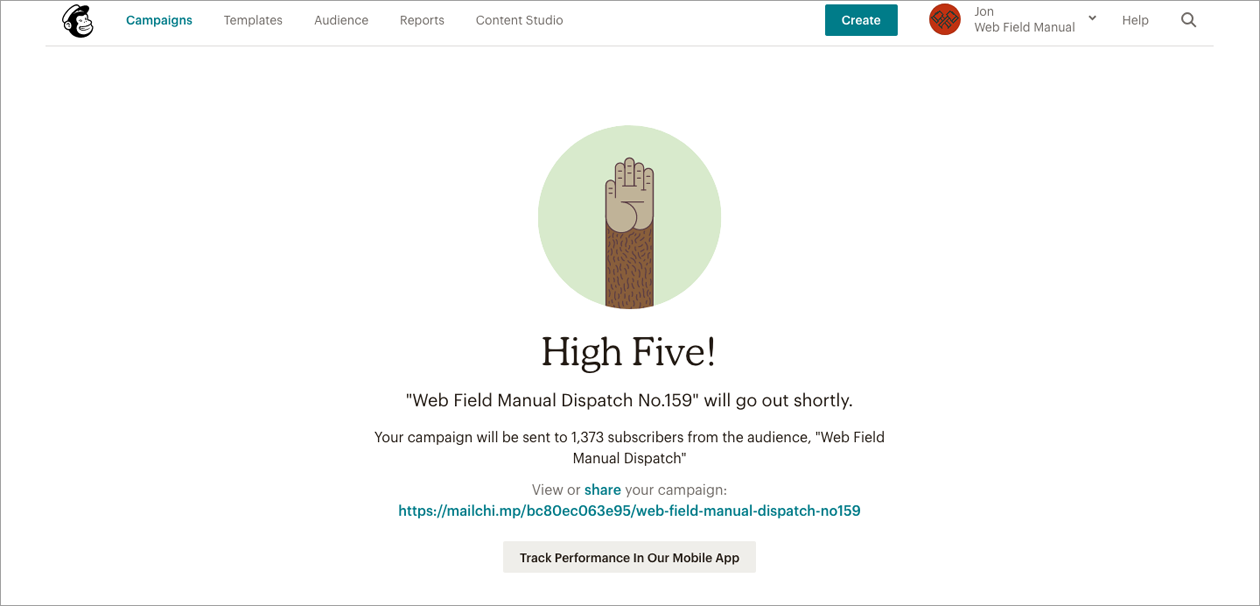

Mailchimp’s artful capitalization on key moments doesn’t end there. Once an email campaign is sent, the user is redirected to a confirmation screen (Figure 6-2) providing details pertaining to the campaign. There’s also an Easter egg on this screen that validates the user’s hard work: Freddie gives them a high five, as if to reassure them of a job well done. These details reinforce the feeling of accomplishment and enhance the experience, creating positive mental snapshots for people that use this service.

Figure 6-2. Mailchimp’s “email sent” screen (source: Mailchimp, 2019)

Positive events aren’t the only things that have an impact on how people feel about a product or service. Negative events also provide emotional peaks and can contribute to a user’s lasting impression of an experience. Take, for example, wait times, which can have a profound effect on how people perceive a product or service. Ride-sharing company Uber realized that waiting was an unavoidable part of its business model and sought to reduce this pain point by focusing on three concepts related to wait time: idleness aversion, operational transparency, and the goal gradient effect.5 Uber Express POOL customers (Figure 6-3) are presented with an animation that helps to keep them not only informed but also entertained (idleness aversion). The app provides an estimated time of arrival and information on how arrival times are calculated (operational transparency). It clearly explains each step of the process so customers feel that they are continuously making progress toward their goal of getting a ride (goal gradient effect). By focusing on people’s perceptions of time and waiting, Uber was able to reduce its post-request cancellation rate and avoid what could easily become a negative emotional peak while using its service.

Figure 6-3. Uber Express POOL (source: Uber, 2019)

Conclusion

Our memories are rarely a perfectly accurate record of events. How users recall an experience will determine how likely they are to use a product or service again or recommend it to others. Since we judge past experiences based not on how we felt throughout the whole duration of the event but on the average of how we felt at the peak emotional moments and at the end, it is vital that these moments make a lasting good impression. By paying close attention to these key moments of an experience, we can ensure users recollect the experience as a whole positively.

1 Daniel Kahneman, Barbara L. Fredrickson, Charles A. Schreiber, and Donald A. Redelmeier, “When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End,” Psychological Science 4, no. 6 (1993): 401–5.

2 Donald A.Redelmeier and Daniel Kahneman, “Patients’ Memories of Painful Medical Treatments: Real-Time and Retrospective Evaluations of Two Minimally Invasive Procedures,” Pain 66, no. 1 (1996): 3–8.

3 Donald A. Redelmeier, Joel Katz, and Daniel Kahneman, “Memories of Colonoscopy: A Randomized Trial,” Pain 104, no. 1–2 (2003): 187–94.

4 Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, “Subjective Probability: A Judgment of Representativeness,” Cognitive Psychology 3, no. 3 (1972): 430–54.

5 Priya Kamat and Candice Hogan, “How Uber Leverages Applied Behavioral Science at Scale,” Uber Engineering (blog), January 28, 2019, https://eng.uber.com/applied-behavioral-science-at-scale.