Baking Bread

Breads

Bread has been a dining staple for thousands of years. The art of breadmaking has evolved over time, but the basic principles remain unchanged. Bread is made from flour of wheat or other grains, with the addition of water, salt, and a fermenting ingredient (such as yeast or another leavening agent). After you’ve baked a few loaves, you’ll start to get a feel for what the dough should look and feel like. Then you can start experimenting with different flours, or additions of fruits, nuts, seeds, herbs, and more.

Quick Breads

Muffins, banana bread, zucchini bread, and many other sweet breads are often leavened with agents other than yeast, such as baking soda or baking powder. These breads are easy to make and require far less preparation time than yeast breads. They’re also very versatile; once you master the basic recipe you can add almost any fruit, nut, or flavoring to make a uniquely delicious treat.

Basic Quick Bread Recipe

This basic recipe will make 2 loaves or 12 large muffins. Fold in 1 to 2 cups of mashed fruit, whole berries, nuts, or chocolate chips before pouring the batter into the pans.

3 ½ cups flour (use at least 2 cups of a gluten-rich flour)

2 tsp baking powder

1 tsp baking soda

1 tsp salt

1 to 2 tsp spices or herbs, if desired

1 ¼ cups sugar

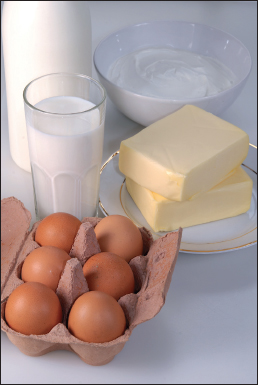

¾ cup butter, oil, or fruit puree

3 eggs

¾ cup milk

1. In a large mixing bowl combine all dry ingredients except sugar.

2. In a separate bowl, beat together sugar and butter, oil, or fruit puree. Add eggs and beat until light and fluffy.

3. Add butter and sugar mixture and milk alternately to the dry ingredients, stirring just until combined. Fold in additional fruit, nuts, or flavors of your choice.

4. For bread, pour into a greased bread pan and bake at 350°F for 1 hour. For muffins, fill muffin cups ⅔ full and bake at 350°F for 20 to 25 minutes.

Cinnamon Bread

2 eggs

½ cup butter

1 cup sugar

½ cup milk

1 ¼ cups flour

2 ½ tsp baking powder

1 tsp cinnamon

1 tsp butter, melted

2 Tbs sugar and 2 Tbs cinnamon, mixed together

1. Beat together the eggs, butter, and sugar until fluffy.

2. In a separate bowl, combine the dry ingredients. Add the dry mixture and the milk to the butter mixture and mix until combined.

3. Bake in a greased bread pan at 300°F for almost an hour. When done pour melted butter over top and sprinkle with cinnamon and sugar mixture.

One-Hour Brown Bread

1 cup cornmeal

1 cup white flour

½ tsp salt

1 tsp baking soda

1 cup water, boiling 1 egg

½ cup molasses

½ cup sugar

1. Combine cornmeal, flour, and salt.

2. Add the baking soda to boiling water and stir. Add to dry ingredients.

3. Beat together egg, molasses, and sugar and add to dry ingredients. Mix until combined. Pour batter into an empty coffee can with a cover (or cover with foil).

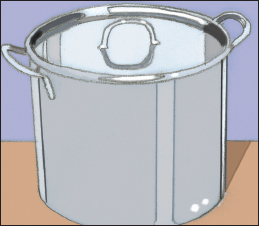

4. Place a cake rack in the bottom of a dutch oven or large pot. Place the covered can on the rack and pour boiling water into the pot until it reaches half way up the cans. Cover the pot, turn the unit on very low, and steam for one hour.

Cinnamon Bread

Date-Orange Bread

2 Tbs butter or margarine melted

¾ cup orange juice

2 Tbs grated orange rind

½ cup finely cut dates

1 cup sugar

1 egg, slightly beaten

½ cup coarsely chopped pecans

2 cups sifted all-purpose flour

½ tsp baking soda

1 tsp baking powder

½ tsp salt

1. Combine first 7 ingredients.

2. Mix and sift remaining ingredients; stir in. Mix well, but quickly, being careful not to overbeat.

3. Turn into greased loaf pan. Bake in moderate oven, 350°F, for 50 minutes or until done. Remove from pan and let cool right side up, on a wire rack.

Caramel Biscuits

2 cups bread flour

4 tsp baking powder 1 tsp salt

1 Tbs lard

1 Tbs butter

⅓ cup milk

⅓ cup water

1 cup light brown sugar

½ cup butter

Nutmeg

Mix and sift the flour, baking powder, and salt twice. Work in the butter and lard with the tips of the fingers until it is thoroughly blended. Add the milk and water and mix to a soft dough, using a knife. (A trifle more liquid may be needed.) Toss on a floured board, roll lightly to one-fourth inch thickness. Cream the brown sugar and butter together till it is smooth, then spread lightly over the dough. Roll up like a jelly roll, fasten end by moistening with milk or water, and cut in pieces three-fourths inch thick. Sprinkle just a little nutmeg over each slice and bake in a hot oven fifteen minutes. Serve hot.

Berry Loaf

⅓ cup shortening

⅔ cup brown sugar

⅓ cup sour milk

1 egg

1 ½ cups pastry flower

1 tsp baking powder

½ tsp baking soda

½ tsp cinnamon

½ tsp salt

½ tsp nutmeg

1 cup cooked berries, drained

Cream together the shortening and the brown sugar; add the milk, egg well beaten, and all the dry ingredients sifted together. Then add the berries. Mix thoroughly together and bake in a well-greased loaf-cake pan.

Yeast Bread

Once you’ve made a loaf of homemade yeast bread, you’ll never want to go back to buying packaged bread from the grocery store. Homemade bread tastes and smells heavenly and the baking process itself can be very rewarding. Store homemade bread in a paper or resealable plastic bag and eat within a day or two for best results. Bread that begins to get stale can be cubed and made into stuffing or croutons.

Before you start baking, it’s helpful to understand the various components that make up bread.

Wheat

Wheat is the most common flour used in bread making, as it contains gluten in the right proportion to make bread rise. Gluten, the protein of wheat, is a gray, tough, elastic substance, insoluble in water. It holds the gas developed in bread dough by fermentation, which otherwise would escape. Though there are many ways to make gluten-free bread, flour that naturally contains gluten will rise more easily than gluten-free grains. In general, combining smaller amounts of other flours (rye, corn, oat, etc.) with a larger proportion of wheat flour will yield the best results.

A grain of wheat consists of (1) an outer covering, or husk, which is always removed before milling; (2) bran, a hard shell that contains minerals and is high in fiber; (3) the germ, which contains the fat and protein content and is the part that can be planted and cultivated to grow more wheat; and (4) the endosperm, which is the wheat plant’s own food source and is mostly starch and protein. Whole wheat contains all of these components except for the husk. White flour is only the endosperm.

Yeast

Yeast is a microscopic fungus that consists of spores, or germs. Thcse spores grow by budding and division, multiply very rapidly under favorable conditions, and produce fermentation. Fermentation is the process by which, uuder influence of air, warmth, and a fermenting ingredient, sugar (or dextrose, starch converted into sugar) is changed into alcohol and carbon dioxide.

Dry yeast is most commonly used for baking. Most grocery stores sell regular active dry and instant yeast. Instant yeast is more finely ground and thus absorbs the moisture faster, speeding up the leavening process and making the bread rise more rapidly.

Active dry yeast should be proofed before using. Mix one packet of active dry yeast with ¼ cup warm water and 1 teaspoon sugar. Stir until yeast dissolves. Allow it to sit for 5 minutes, or until it becomes foamy.

Milling Your Own Grains

You can grind grains into flour at home using a mortar and pestle, a coffee or spice mill, manual or electric food grinders, a blender, or a food processor. Grains with a shell (quinoa, wheat berries, etc.) should be rinsed and dried before milling to remove the layer of resin from the outer shell that can impart a bitter taste to your flour. Rinse the grains thoroughly in a colander or mesh strainer, then spread them on a paper or cloth towel to absorb the extra moisture. Transfer to a baking sheet and allow to air dry completely (to speed this process you can put them in a very low oven for a few minutes). When the grains are dry, they’re ready to be ground.

| FLOUR | DESCRIPTION |

| All-purpose | A blend of high- and low-gluten wheat. Slightly less protein than bread flour. Best for cookies and cakes. |

| Amaranth | Gluten-free. Made from seeds of amaranth plants. Very high in fiber and iron. |

| Arrowroot | Gluten-free. Made from the ground-up root. Clear when cooked, which makes it perfect for thickening soups or sauces. |

| Barley | Ground barley grain. Very low in gluten. Use as a thickener in soups or stews or mixed with other flours in baked goods. |

| Bran | Made from the hard outer layer of wheat berries. Very high in protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. |

| Bread | Made from hard, high-protein wheat with small amounts of malted barley flour and vitamin C or potassium bromate. It has a high gluten content, which helps bread to rise. Excellent for bread, but not as good for use in cookies or cakes. |

| Chickpea | Gluten-free. Made from ground chickpeas. Used frequently in Indian, Middle Eastern, and some French Provençal cooking. |

| Buckwheat | Gluten free. Highly nutritious with a slightly nutty flavor. |

| Oat | Gluten-free, though many people with gluten allergies or sensitivities are also adversely affected by oats. Made from ground oats. High in fiber. |

| Quinoa | Gluten-free. Made from ground quinoa, a grain native to the Andes in South America. Slightly yellow or ivorycolored with a mild nutty flavor. Very high in protein. |

| Rye | Milled from rye berries and rye grass. High in fiber and low in gluten. Light rye has had more of the bran removed through the milling process than dark rye. Slightly sour flavor. |

| Semolina | Finely ground endosperm of durum wheat. Very high in gluten. Often used in pasta. |

| Soy | Gluten-free. Made from ground soybeans. High in protein and fiber. |

| Spelt | Similar to wheat, but with a higher protein and nutrient content. Contains gluten but is often easier to digest than wheat. Slightly nutty flavor. |

| Tapioca | Gluten-free. Made from the cassava plant. Starchy and slightly sweet. Generally used for thickening soups or puddings, but can also be used along with other flours in baked goods. |

| Teff | Gluten-free. Higher protein content than wheat and full of fiber, iron, calcium, and thiamin. |

| Whole wheat | Includes the bran, germ, and endosperm of the wheat berry. Far more nutritious than white flour, but has a shorter shelf life. |

1 package active dry yeast = about 2 ¼ teaspoons = ¼ ounce

4-ounce jar active dry yeast = 14 tablespoons

1 (6-ounce) cube or cake of compressed yeast (also know as fresh yeast) = 1 package of active dry yeast

Multiply the amount of instant yeast by 3 for the equivalent amount of fresh yeast.

Multiply the amount of active dry yeast by 2.5 for the equivalent amount of fresh yeast.

Multiply the amount of instant yeast by 1.25 for the equivalent of active dry yeast.

Gluten-Free Bread

Making good gluten-free bread isn’t always easy, but there are several things you can do to improve your chances of success:

• Choose flours that are high in protein, such as sorghum, amaranth, millet, teff, oatmeal, and buckwheat

• Use all room temperature ingredients. Yeast thrives in warm environments.

• Add a couple teaspoons of xantham gum to your dry ingredients.

• Add eggs and dry milk powder to your bread. These will add texture and help the bread to rise.

• Crush a vitamin C tablet and add it to your dry ingredients. The acidity will help the yeast do its job.

• Substitiute carbonated water or gluten-free beer for other liquids in the recipe.

• If you’re following a traditional bread recipe, add extra liquid (water, carbonated water, milk, fruit juice, or olive oil) to get a soft and sticky consistency. The batter should be a little too sticky to knead. For this reason, bread machines are great for making gluten-free bread.

Making Bread

Making bread is a fairly simple process, though it does require a chunk of time. Keep in mind, though, that you can be doing other things while the bread is rising or baking. The process is fairly straightforward and only varies slightly by kind of bread.

1. Mix together the flour, sugar, salt, and any other dry ingredients. Form a well in the center and add the dissolved yeast and any other wet ingredients. Mix all the ingredients together.

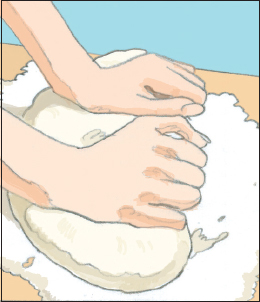

2. Gather the dough into a ball and place it on a lightly floured surface. Flour your hands to keep the dough from sticking to your fingers. Knead the dough by folding it toward you and then pushing it away with the palms of your hands. Continue kneading for five to ten minutes, or until the dough is soft and elastic.

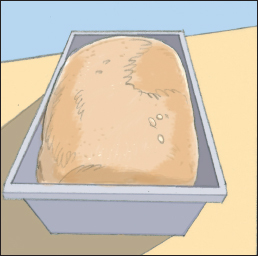

3. Place the dough in a lightly greased pan, cover with a dish towel, and allow to rise in a warm place until it doubles in size.

4. Punch the dough down to expel the air and place it in a greased and lightly floured baking pan. Cover and let rise a second time until it doubles in size.

5. Bake the bread in a preheated oven according the recipe. Bread is done when it is golden brown and sounds hollow when you tap the top.

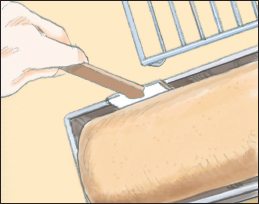

6. Remove bread from the pan by loosening the sides with a knife or spatula and tipping the pan upside down onto a wire rack.

Biscuits

Any bread recipe can be made into biscuits instead of one large loaf. To shape bread dough into biscuits, pull or cut off pieces, making them all as close to uniform in size as possible. Flour palms of hands slightly and shape each piece individually. Using the thumb and first two fingers of one hand, and holding it in the palm of the other hand, move the dough round and round, folding the dough towards the center. When smooth, turn it over and roll between palms of hands. Place in greased pans near together, brushed between with a little melted butter, which will allow biscuits to separate after baking.

Multigrain Bread

¼ cup yellow cornmeal

¼ cup packed brown sugar

1 tsp salt

2 Tbs vegetable oil

1 cup boiling water

1 package active dry yeast

¼ cup warm (105 to 115ºF) water

⅓ cup whole wheat flour

¼ cup rye flour

2 ¼–2 ¾ cups all-purpose flour

1. Mix cornmeal, brown sugar, salt, and oil with boiling water; cool to lukewarm (105 to 115ºF).

2. Dissolve yeast in ¼ cup warm water; stir into cornmeal mixture. Add whole wheat and rye flours and mix well. Stir in enough all-purpose flour to make dough stiff enough to knead.

3. Turn dough onto lightly floured surface. Knead until smooth and elastic, about 5 to 10 minutes.

4. Place dough in lightly oiled bowl, turning to oil top. Cover with clean towel; let rise in warm place until double, about 1 hour.

5. Punch dough down; turn onto clean surface. Cover with clean towel; let rest 10 minutes. Shape dough and place in greased 9 x 5 inch pan. Cover with clean towel; let rise until almost double, about 1 hour.

6. Preheat oven to 375ºF. Bake 35 to 45 minutes or until bread sounds hollow when tapped. Cover with aluminum foil during baking if bread is browning too quickly. Remove bread from pan and cool on wire rack.

Handy Household Hints

Dip your knife in boiling water and you can cut the thinnest slice from a fresh loaf.

The Junior Homesteader

Bread in a Bag

Materials needed:

• A heavy-duty zipper-lock freezer bag (1 gallon size)

• Measuring cup

• Measuring spoons

• Cookie sheet

• Pastry towel or cloth

• 13-inch x 9-inch baking pan

• 8½-inch x 4½-inch glass loaf pan

Ingredients:

2 cups all-purpose flour, divided

1 package rapid rise yeast

3 Tbs sugar

3 Tbs nonfat dry milk

1 teaspoon salt

1 cup hot water (125ºF)

3 Tbs vegetable oil

1 cup whole-wheat flour

1. Combine 1 cup all-purpose flour, yeast, sugar, dry milk, and salt in a freezer bag. Squeeze upper part of the bag to force out air and then seal the bag.

2. Shake and work the bag with fingers to blend the ingredients.

3. Add hot water and oil to the dry ingredients in the bag. Reseal the bag and mix by working with fingers.

4. Add whole-wheat flour. Reseal the bag and mix ingredients thoroughly.

5. Gradually add remaining cup of all-purpose flour to the bag. Reseal and work with fingers until the dough becomes stiff and pulls away from sides of the bag.

6. Take dough out of the bag, and place on floured surface.

7. Knead dough 2 to 4 minutes, until smooth and elastic.

8. Cover dough with a moist cloth or pastry towel; let dough stand for 10 minutes.

9. Roll dough to 12-inch x 7-inch rectangle. Roll up from narrow end. Pinch edges and ends to seal.

10. Place dough in a greased glass loaf pan; cover with a moist cloth or pastry towel.

11. Place baking pan on the counter; half fill with boiling water.

12. Place cookie sheet over the baking pan and place loaf pan on top of the cookie sheet; let dough rise 20 minutes or until dough doubles in size.

13. Preheat oven, 375ºF, while dough is rising (about 15 minutes).

14. Place loaf pan in oven and bake at 375ºF for 25 minutes or until baked through.

Oatmeal Bread

1 cup rolled oats

1 tsp salt

1 ½ cups boiling water

1 package active dry yeast

¼ cup warm water (105 to 115ºF)

¼ cup light molasses

1 ½ Tbs vegetable oil

2 cups whole wheat flour

2–2 ½ cups all-purpose flour

1. Combine rolled oats and salt in a large mixing bowl. Stir in boiling water; cool to lukewarm (105 to 115ºF).

2. Dissolve yeast in ¼ cup warm water in small bowl.

3. Add yeast water, molasses, and oil to cooled oatmeal mixture. Stir in whole wheat flour and 1 cup all-purpose flour. Add additional all-purpose flour to make a dough stiff enough to knead.

4. Knead dough on lightly floured surface until smooth and elastic, about 5 minutes.

5. Place dough in lightly oiled bowl, turning to oil top. Cover with clean towel; let rise in warm place until double, about 1 hour.

6. Punch dough down; turn onto clean surface. Shape dough and place in greased 9 x 5 inch pan. Cover with clean towel; let rise in a warm place until almost double, about 1 hour.

7. Preheat oven to 375ºF. Bake 50 minutes or until bread sounds hollow when tapped. Cover with aluminum foil during baking if bread is browning too quickly. Remove bread from pan and cool on wire rack.

Substitutions

| Spices | |

| Allspice | Cinnamon, cassia, dash of nutmeg, mace; or cloves |

| Aniseed | Fennel seed or a few drops anise extract |

| Cardamom | Ginger |

| Chili Powder | Dash bottled hot pepper sauce plus a combination of oregano and cumin |

| Cinnamon | Nutmeg or allspice (use only ¼ of the amount) |

| Cloves | Allspice, cinnamon, or nutmeg |

| Cumin | Chili powder |

| Ginger | Allspice, cinnamon, mace, or nutmeg |

| Mace | Allspice, cinnamon, ginger, or nutmeg |

| Nutmeg | Cinnamon; ginger; or mace |

| Saffron | Dash turmeric (for color) |

| Leavens | |

| Baking Powder (1 tsp) | • ⅝ tsp cream of tartar plus ¼ tsp baking soda |

| • 2 parts cream of tartar plus 1 part baking soda plus 1 part cornstarch | |

| • Add ¼ tsp baking soda to dry ingredients and ½ C. buttermilk or yogurt or sour milk to wet ingredients. Decrease another liquid in the recipe by ½ C. | |

| • 1 tsp baker’s ammonia | |

| Baking Soda | Potassium BiCarbonate |

| Baker’s Ammonia (1 tsp) | • 1 tsp baking powder |

| • 1 tsp baking powder plus 1 tsp baking soda | |

Handy Household Hints

Vanilla Essence or Extract

This is an expensive article when of fine quality, and you may prepare it yourself either with brandy or alcohol. With brandy, the flavor is superior. Cut into very small shreds three vanilla beans, put them in a bottle with a pint of brandy and cork the bottle tightly. Shake it occasionally and it will be ready for use after three months. You may shorten the process to three weeks by using alcohol at 95 percent. Chop three vanilla beans and pound them in a mortar. Cover them with a little powdered sugar and put them in a pint bottle, adding a tablespoonful of water. Let it stand twelve hours, then pour over it a half pint of alcohol or spirits of wine. Cork tightly, shake it every day, and it will be ready for use in three weeks.

Beer

Home brewing has grown in popularity to the point where the equipment and ingredients are fairly easy to find. The Internet is the easiest place to find the tools you’ll need.

What You’ll Need

1. Brewpot: a huge, stainless steel (or other enamelcoated metal) pot of at least sixteen quart capacity. This will be used to boil all the ingredients, otherwise known as “wort.”

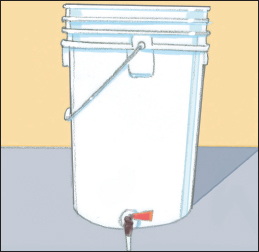

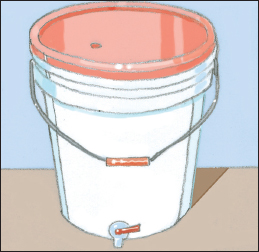

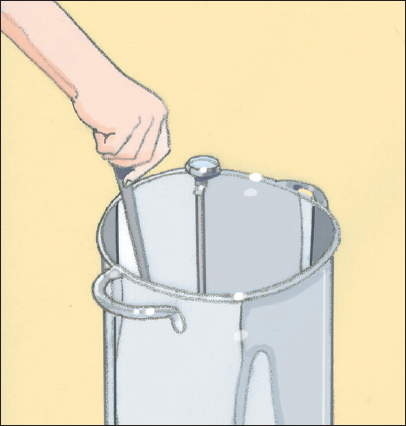

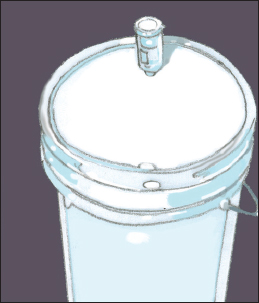

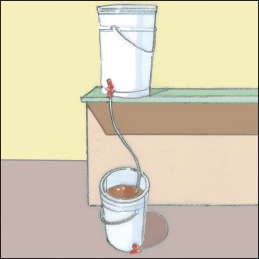

2. Primary fermenter: where the wort goes after it’s been boiled. It’s where beer begins to ferment. The fermenter must have a capacity of seven gallons and an airtight lid that can accommodate an airlock and rubber stopper. Look for one made of food-grade plastic.

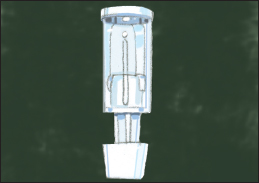

3. Airlock and stopper: the airlock allows carbon dioxide to escape without allowing any outside air in and fits into a rubber stopper with a hole drilled in it. The stopper goes on top of the primary fermenter; they are sized by number, so make sure to match the size of the hole with the stopper that fits it.

4. Plastic hose: a five-foot length of hose made out of food-grade plastic is ideal to transfer beer. Make sure to keep it clean and clear of kinks or leaks.

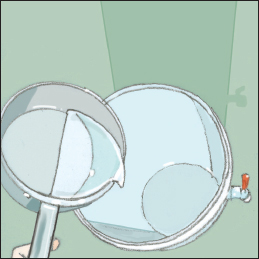

5. Bottling bucket: a one gallon, food-grade plastic bucket with a spigot at the bottom. It must be at least as big as the primary fermenter.

6. Beer bottles. After primary fermentation, you place beer in bottles for the second stage of fermentation and then finally, storage. You need enough bottles to hold all the beer you’ll make (a five gallon batch is 640oz). Use solid dark glass bottles (to keep the light out) with smooth tops (not the ones that accommodate twist-off caps) that will accept a cap from a bottle capper.

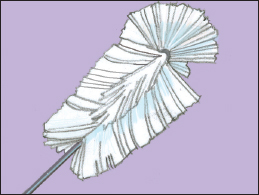

7. Bottle brush: thin, curvy brush to clean the beer bottle.

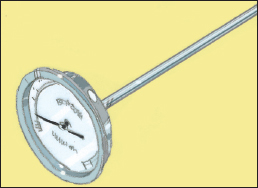

8. Stick-on thermometer.

9. Household items: a small bowl, saucepan, rubber spatula, over mitts, a big mixing spoon (stainless steel or plastic).

Choose a recipe and buy ingredients, or buy a “beer kit,” which includes a can of hopped malt concentrate and a packet of yeast. For your first time brewing, a beer kit may be the best choice since it would eliminate the possibility of error and allow you to get used to the procedure. Purchase other fermentables (more fermentables mean more alcohol) like dry malt extract, rice syrup, brewers’ sugar, liquid malt extract, Belgian candi sugar, or demera sugar or any combination of the above. You need at least two pounds of fermentables, but no more than three.

Clean and sanitize all the equipment you’ll use. Sanitizing is the use of heat, chlorine, or iodine mixed with water, but if your dishwasher has a “heat dry” cycle, cut down the preparation time by using it.

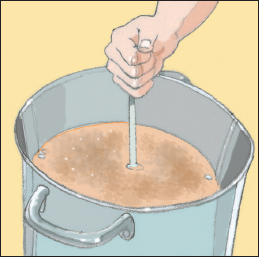

1. Bring 2 quarts of water to 160-180 degrees F: steaming, but not boiling. Remove from heat.

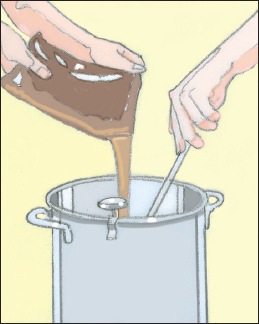

2. Add your beer kit (or recipe) and additional fermentables according to the directions. Each fermentable adds its own unique flavor.

3. Stir aggressively to dissolve everything in the pot. Put the lid on the pot and let it sit for 10-15 minutes on the lowest heat setting.

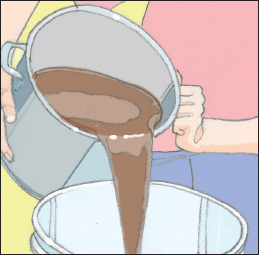

4. Add the contest of the pot to 4 gallons of cold water, which should already be waiting in the primary fermenter. Mix well, at least a minute or two, to add oxygen to the wort prior to adding the yeast. When the side of your fermenter is cool to the touch, it’s safe to add the yeast.

5. Ferment as close to the recommended temperature range as possible. It will begin to ferment within the first day and continue to do so for 3-5 days. You can tell because of the air bubbles. When there no bubbles, or a pause of two minutes in between bubbles, the beer is ready to be bottled.

6. Make sure you have enough bottles ready and cleaned and sanitized! Also have pure dextrose on hand to make the priming solution, which is what helps the yeast already in the beer to carbonate. Take the saucepan and put 2 or 3 cups of water in it. Dissolve ¾ cups of dextrose in the water. Then, bring it to a boil over medium heat, cover it, and set aside to cool for 15-20 minutes.

7. After this is done, place the bottling bucket on the floor. Place the primary fermenter on a chair, table, or counter directly above the bottling bucket; do not shake the beer up inside the fermenter as the sediment should stay at the bottom. Attach the plastic hose to the spigot on the fermenter and put the other end of the hose in the bottom of the bottling bucket. Pour priming solution into bottling bucket and open the spigot on the fermenter, allowing the beer to flow in and mix with the solution. Don’t worry about saving the last of the beer in the fermenter since it contains sediment.

8. Move the fermenter and put the bottling bucket where it was. Hook the hose to its spigot. Line up the bottles on the floor underneath and stick the hose into one, all the way into the bottle. Open up the spigot and fill the bottle until the beer gets to the top, leaving about an inch of airspace. Quickly yank the hose out and stick it in the next bottle.

9. Once all the beer is drained out of the bucket, put caps on the bottles. Every second your beer is exposed to the air is bad. Find a cool, dark place to put the bottles while the second round of fermentation takes place. Do not put it in a refrigerator. Leave the beer to ferment for a minimum of two weeks before you drink it. Once the cloudiness caused by the yeast has dissipated (after the two weeks), you can put it in the fridge. If it hasn’t cleared, leave it to sit for longer. When you finally drink your beer, it’s best to pour it in the glass rather than drinking straight from the bottle to avoid the sediment and leftover yeast.

Butter

Making butter the old-fashioned way is incredibly simple and very gratifying. It’s a great project to do with kids, too. All you need are a jar, a marble, some fresh cream, and about 20 minutes.

1. Start with about twice as much heavy whipping cream as you’ll want butter. Pour it into the jar, drop in the marble, close the lid tightly, and start shaking.

2. Check the consistency of the cream every three to four minutes. The liquid will turn into whipped cream, and then eventually you’ll see little clumps of butter forming in the jar. Keep shaking for another few minutes and then begin to strain out the liquid into another jar. This is buttermilk, which is great for use in making pancakes, waffles, biscuits, and muffins.

3. The butter is now ready, but it will store better if you wash and work it. Add ½ cup of ice cold water and continue to shake for two or three minutes. Strain out the water and repeat. When the strained water is clear, mash the butter to extract the last of the water, and strain.

4. Scoop the butter into a ramekin, mold, or wax paper.

If desired, add salt or chopped fresh herbs to your butter just before storing or serving. Butter can also be made in a food processor or blender to speed up the processing time.

Canning

Canning began in France, at the turn of the nineteenth century, when Napoleon Bonaparte was desperate for a way to keep his troops well fed while on the march. In 1800 he decided to hold a contest, offering 12,000 francs to anyone who could devise a suitable method of food preservation. Nicolas François Appert, a French confectioner, rose to the challenge, considering that if wine could be preserved in bottles, perhaps food could be as well. He experimented until he was able to prove that heating food to boiling after it had been sealed in airtight glass bottles prevented the food from deteriorating. Interestingly, this all took place about 100 years before Louis Pasteur found that heat could destroy bacteria. Nearly ten years after the contest began, Napoleon personally presented Nicolas with the cash reward.

Canning practices have evolved over the last two centuries, but the principles remain the same. In fact, the way we can foods today is basically the same way our grandparents and great grandparents preserved their harvests for the winter months.

On the next few pages you will find descriptions of proper canning methods, with details on how canning works and why it is both safe and economical. Much of the information here is from the USDA, which has done extensive research on home canning and preserving. If you are new to home canning, read this section carefully as it will help to ensure success with the recipes that follow.

Whether you are a seasoned home canner or this is your first foray into food preservation, it is important to follow directions carefully. With some recipes it is okay to experiment with varied proportions or added ingredients, and with others it is important to stick to what’s written. In many instances it is noted whether or not creative liberty is a good idea for a particular recipe, but if you are not sure, play it safe—otherwise you may end up with a jam that is too runny, a vegetable that is mushy, or a product that is spoiled. Take time to read the directions and prepare your foods and equipment adequately and you will find that home canning is safe, economical, tremendously satisfying, and a great deal of fun!

The Benefits of Canning

Canning is fun, economical, and a good way to preserve your precious produce. As more and more farmers’ markets make their way into urban centers, city dwellers are also discovering how rewarding it is to make seasonal treats last all year round. Besides the value of your labor, canning home-grown or locally grown food may save you half the cost of buying commercially canned food. Freezing food may be simpler, but most people have limited freezer space, whereas cans of food can be stored almost anywhere. And what makes a nicer, more thoughtful gift than a jar of homemade jam, tailored to match the recipient’s favorite fruits and flavors?

The nutritional value of home canning is an added benefit. Many vegetables begin to lose their vitamins as soon as they are harvested. Nearly half the vitamins may be lost within a few days unless the fresh produce is kept cool or preserved. Within one to two weeks, even refrigerated produce loses half or more of certain vitamins. The heating process during canning destroys from one-third to one-half of vitamins A and C, thiamin, and riboflavin. Once canned, foods may lose from 5 percent to 20 percent of these sensitive vitamins each year. The amounts of other vitamins, however, are only slightly lower in canned compared with fresh food. If vegetables are handled properly and canned promptly after harvest, they can be more nutritious than fresh produce sold in local stores.

The advantages of home canning are lost when you start with poor quality foods, when jars fail to seal properly, when food spoils, and when flavors, texture, color, and nutrients deteriorate during prolonged storage. The tips that follow explain many of these problems and recommend ways to minimize them.

How Canning Preserves Foods

The high percentage of water in most fresh foods makes them very perishable. They spoil or lose their quality for several reasons:

• Growth of undesirable microorganisms—bacteria, molds, and yeasts

• Activity of food enzymes

• Reactions with oxygen

• Moisture loss

Microorganisms live and multiply quickly on the surfaces of fresh food and on the inside of bruised, insectdamaged, and diseased food. Oxygen and enzymes are present throughout fresh food tissues.

Proper canning practices include:

• Carefully selecting and washing fresh food

• Peeling some fresh foods

• Hot packing many foods

• Adding acids (lemon juice, citric acid, or vinegar) to some foods

• Using acceptable jars and self-sealing lids

• Processing jars in a boiling-water or pressure canner for the correct amount of time

Collectively, these practices remove oxygen; destroy enzymes; prevent the growth of undesirable bacteria, yeasts, and molds; and help form a high vacuum in jars. High vacuums form tight seals, which keep liquid in and air and microorganisms out.

Canning Glossary

Acid foods—Foods that contain enough acid to result in a pH of 4.6 or lower. Includes most tomatoes; fermented and pickled vegetables; relishes; jams, jellies, and marmalades; and all fruits except figs. Acid foods may be processed in boiling water.

Ascorbic acid—The chemical name for vitamin C; commonly used to prevent browning of peeled, lightcolored fruits and vegetables.

Blancher—A 6- to 8-quart lidded pot designed with a fitted, perforated basket to hold food in boiling water or with a fitted rack to steam foods. Useful for loosening skins on fruits to be peeled or for heating foods to be hot packed.

Boiling-water canner—A large, standard-sized, lidded kettle with jar rack designed for heat-processing seven quarts or eight to nine pints in boiling water.

Tip

A large stockpot with a lid can be used in place of a boilingwater canner for high-acid foods like tomatoes, pickles, apples, peaches, and jams. Simply place a rack inside the pot so that the jars do not rest directly on the bottom of the pot.

Botulism—An illness caused by eating a toxin produced by growth of Clostridium botulinum bacteria in moist, low-acid food containing less than 2 percent oxygen and stored between 40°F and 120°F. Proper heat processing destroys this bacterium in canned food. Freezer temperatures inhibit its growth in frozen food. Low moisture controls its growth in dried food. High oxygen controls its growth in fresh foods.

Canning—A method of preserving food that employs heat processing in airtight, vacuum-sealed containers so that food can be safely stored at normal home temperatures.

Canning salt—Also called pickling salt. It is regular table salt without the anti-caking or iodine additives.

Citric acid—A form of acid that can be added to canned foods. It increases the acidity of low-acid foods and may improve their flavor.

Cold pack—Canning procedure in which jars are filled with raw food. “Raw pack” is the preferred term for describing this practice. “Cold pack” is often used incorrectly to refer to foods that are open-kettle canned or jars that are heat-processed in boiling water.

Enzymes—Proteins in food that accelerate many flavor, color, texture, and nutritional changes, especially when food is cut, sliced, crushed, bruised, or exposed to air. Proper blanching or hot-packing practices destroy enzymes and improve food quality.

Exhausting—Removing air from within and around food and from jars and canners. Exhausting or venting of pressure canners is necessary to prevent botulism in low-acid canned foods.

Headspace—The unfilled space above food or liquid in jars that allows for food expansion as jars are heated and for forming vacuums as jars cool.

Heat processing—Treatment of jars with sufficient heat to enable storing food at normal home temperatures.

Hermetic seal—An absolutely airtight container seal that prevents reentry of air or microorganisms into packaged foods.

Hot pack—Heating of raw food in boiling water or steam and filling it hot into jars.

Low-acid foods—Foods that contain very little acid and have a pH above 4.6. The acidity in these foods is insufficient to prevent the growth of botulism bacteria. Vegetables, some varieties of tomatoes, figs, all meats, fish, seafood, and some dairy products are low-acid foods. To control all risks of botulism, jars of these foods must be either heat processed in a pressure canner or acidified to a pH of 4.6 or lower before being processed in boiling water.

Microorganisms—Independent organisms of microscopic size, including bacteria, yeast, and mold. In a suitable environment, they grow rapidly and may divide or reproduce every 10 to 30 minutes. Therefore, they reach high populations very quickly. Microorganisms are sometimes intentionally added to ferment foods, make antibiotics, and for other reasons. Undesirable microorganisms cause disease and food spoilage.

Mold—A fungus-type microorganism whose growth on food is usually visible and colorful. Molds may grow on many foods, including acid foods like jams and jellies and canned fruits. Recommended heat processing and sealing practices prevent their growth on these foods.

Mycotoxins—Toxins produced by the growth of some molds on foods.

Open-kettle canning—A non-recommended canning method. Food is heat-processed in a covered kettle, filled while hot into sterile jars, and then sealed. Foods canned this way have low vacuums or too much air, which permits rapid loss of quality in foods. Also, these foods often spoil because they become recontaminated while the jars are being filled.

Pasteurization—Heating food to temperatures high enough to destroy disease-causing microorganisms.

pH—A measure of acidity or alkalinity. Values range from 0 to 14. A food is neutral when its pH is 7.0. Lower values are increasingly more acidic; higher values are increasingly more alkaline.

PSIG—Pounds per square inch of pressure as measured by a gauge.

Pressure canner—A specifically designed metal kettle with a lockable lid used for heat processing lowacid food. These canners have jar racks, one or more safety devices, systems for exhausting air, and a way to measure or control pressure. Canners with 20- to 21-quart capacity are common. The minimum size of canner that should be used has a 16-quart capacity and can hold seven one-quart jars. Use of pressure saucepans with a capacity of less than 16 quarts is not recommended.

Raw pack—The practice of filling jars with raw, unheated food. Acceptable for canning low-acid foods, but allows more rapid quality losses in acid foods that are heat-processed in boiling water. Also called “cold pack.”

Style of pack—Form of canned food, such as whole, sliced, piece, juice, or sauce. The term may also be used to specify whether food is filled raw or hot into jars.

Vacuum—A state of negative pressure that reflects how thoroughly air is removed from within a jar of processed food; the higher the vacuum, the less air left in the jar.

Proper Canning Practices

Growth of the bacterium Clostridium botulinum in canned food may cause botulism—a deadly form of food poisoning. These bacteria exist either as spores or as vegetative cells. The spores, which are comparable to plant seeds, can survive harmlessly in soil and water for many years. When ideal conditions exist for growth, the spores produce vegetative cells, which multiply rapidly and may produce a deadly toxin within three to four days in an environment consisting of:

• A moist, low-acid food

• A temperature between 40°F and 120°F, and

• Less than 2 percent oxygen.

Botulinum spores are on most fresh food surfaces. Because they grow only in the absence of air, they are harmless on fresh foods. Most bacteria, yeasts, and molds are difficult to remove from food surfaces. Washing fresh food reduces their numbers only slightly. Peeling root crops, underground stem crops, and tomatoes reduces their numbers greatly. Blanching also helps, but the vital controls are the method of canning and use of the recommended research-based processing times. These processing times ensure destruction of the largest expected number of heat-resistant microorganisms in home-canned foods.

Properly sterilized canned food will be free of spoilage if lids seal and jars are stored below 95°F. Storing jars at 50 to 70°F enhances retention of quality.

Food Acidity and Processing Methods

Whether food should be processed in a pressure canner or boiling-water canner to control botulism bacteria depends on the acidity in the food. Acidity may be natural, as in most fruits, or added, as in pickled food. Low-acid canned foods contain too little acidity to prevent the growth of these bacteria. Other foods may contain enough acidity to block their growth or to destroy them rapidly when heated. The term “pH” is a measure of acidity: the lower its value, the more acidic the food. The acidity level in foods can be increased by adding lemon juice, citric acid, or vinegar.

Low-acid foods have pH values higher than 4.6. They include red meats, seafood, poultry, milk, and all fresh vegetables except for most tomatoes. Most products that are mixtures of low-acid and acid foods also have pH values above 4.6 unless their ingredients include enough lemon juice, citric acid, or vinegar to make them acid foods. Acid foods have a pH of 4.6 or lower. They include fruits, pickles, sauerkraut, jams, jellies, marmalade, and fruit butters.

Although tomatoes usually are considered an acid food, some are now known to have pH values slightly above 4.6. Figs also have pH values slightly above 4.6. Therefore, if they are to be canned as acid foods, these products must be acidified to a pH of 4.6 or lower with lemon juice or citric acid. Properly acidified tomatoes and figs are acid foods and can be safely processed in a boiling-water canner.

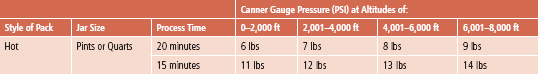

Botulinum spores are very hard to destroy at boilingwater temperatures; the higher the canner temperature, the more easily they are destroyed. Therefore, all lowacid foods should be sterilized at temperatures of 240 to 250°F, attainable with pressure canners operated at 10 to 15 PSIG. (PSIG means pounds per square inch of pressure as measured by a gauge.) At these temperatures, the time needed to destroy bacteria in low-acid canned foods ranges from 20 to 100 minutes. The exact time depends on the kind of food being canned, the way it is packed into jars, and the size of jars. The time needed to safely process low-acid foods in boiling water ranges from seven to 11 hours; the time needed to process acid foods in boiling water varies from five to 85 minutes.

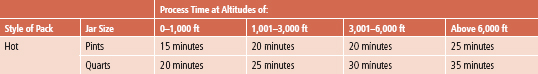

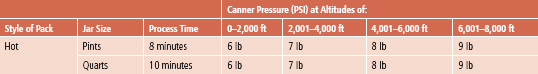

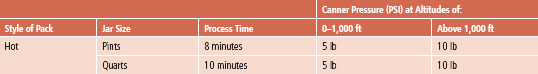

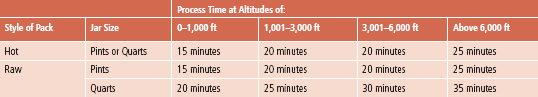

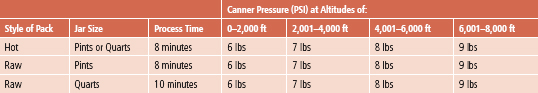

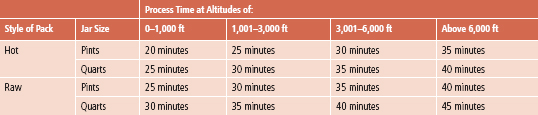

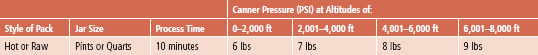

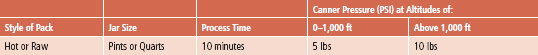

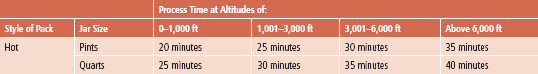

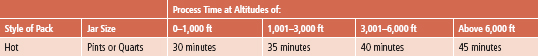

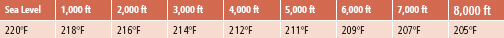

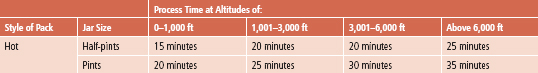

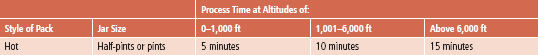

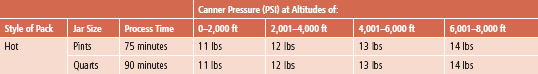

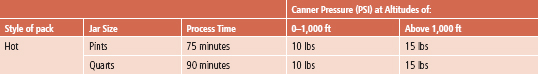

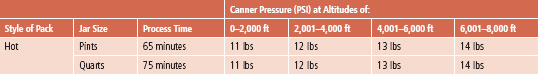

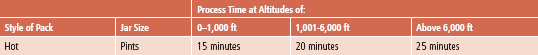

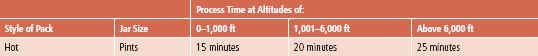

Know Your Altitude

It is important to know your approximate elevation or altitude above sea level in order to determine a safe processing time for canned foods. Since the boiling temperature of liquid is lower at higher elevations, it is critical that additional time be given for the safe processing of foods at altitudes above sea level.

What Not to Do

Open-kettle canning and the processing of freshly filled jars in conventional ovens, microwave ovens, and dishwashers are not recommended because these practices do not prevent all risks of spoilage. Steam canners are not recommended because processing times for use with current models have not been adequately researched. Because steam canners may not heat foods in the same manner as boiling-water canners, their use with boiling-water processing times may result in spoilage. So-called canning powders are useless as preservatives and do not replace the need for proper heat processing.

It is not recommended that pressures in excess of 15 PSIG be applied when using new pressure-canning equipment.

Ensuring High-Quality Canned Foods

Examine food carefully for freshness and wholesomeness. Discard diseased and moldy food. Trim small diseased lesions or spots from food.

Can fruits and vegetables picked from your garden or purchased from nearby producers when the products are at their peak of quality—within six to 12 hours after harvest for most vegetables. However, apricots, nectarines, peaches, pears, and plums should be ripened one or more days between harvest and canning. If you must delay the canning of other fresh produce, keep it in a shady, cool place.

Fresh, home-slaughtered red meats and poultry should be chilled and canned without delay. Do not can meat from sickly or diseased animals. Put fish and seafood on ice after harvest, eviscerate immediately, and can them within two days.

Maintaining Color and Flavor in Canned Food

To maintain good natural color and flavor in stored canned food, you must:

• Remove oxygen from food tissues and jars

• Quickly destroy the food enzymes, and

• Obtain high jar vacuums and airtight jar seals.

Follow these guidelines to ensure that your canned foods retain optimal colors and flavors during processing and storage:

• Use only high-quality foods that are at the proper maturity and are free of diseases and bruises

• Use the hot-pack method, especially with acid foods to be processed in boiling water

• Don’t unnecessarily expose prepared foods to air; can them as soon as possible

• While preparing a canner load of jars, keep peeled, halved, quartered, sliced or diced apples, apricots, nectarines, peaches, and pears in a solution of 3 grams (3000 milligrams) ascorbic acid to 1 gallon of cold water. This procedure is also useful in maintaining the natural color of mushrooms and potatoes and for preventing stem-end discoloration in cherries and grapes. You can get ascorbic acid in several forms:

Pure powdered form—Seasonally available among canning supplies in supermarkets. One level teaspoon of pure powder weighs about 3 grams. Use 1 teaspoon per gallon of water as a treatment solution.

Vitamin C tablets—Economical and available yearround in many stores. Buy 500-milligram tablets; crush and dissolve six tablets per gallon of water as a treatment solution.

Commercially prepared mixes of ascorbic and citric acid—Seasonally available among canning supplies in supermarkets. Sometimes citric acid powder is sold in supermarkets, but it is less effective in controlling discoloration. If you choose to use these products, follow the manufacturer’s directions.

• Fill hot foods into jars and adjust headspace as specified in recipes

• Tighten screw bands securely, but if you are especially strong, not as tightly as possible

• Process and cool jars

• Store the jars in a relatively cool, dark place, preferably between 50 and 70°F

• Can no more food than you will use within a year.

Many fresh foods contain from 10 percent to more than 30 percent air. The length of time that food will last at premium quality depends on how much air is removed from the food before jars are sealed. The more air that is removed, the higher the quality of the canned product.

Raw packing is the practice of filling jars tightly with freshly prepared but unheated food. Such foods, especially fruit, will float in the jars. The entrapped air in and around the food may cause discoloration within two to three months of storage. Raw-packing is more suitable for vegetables processed in a pressure canner.

Hot packing is the practice of heating freshly prepared food to boiling, simmering it three to five minutes, and promptly filling jars loosely with the boiled food. Hot packing is the best way to remove air and is the preferred pack style for foods processed in a boilingwater canner. At first, the color of hot-packed foods may appear no better than that of raw-packed foods, but within a short storage period both color and flavor of hot-packed foods will be superior.

Whether food has been hot packed or raw packed, the juice, syrup, or water to be added to the foods should be heated to boiling before it is added to the jars. This practice helps to remove air from food tissues, shrinks food, helps keep the food from floating in the jars, increases vacuum in sealed jars, and improves shelf life. Preshrinking food allows you to add more food to each jar.

Controlling Headspace

The unfilled space above the food in a jar and below its lid is termed headspace. It is best to leave a ¼-inch headspace for jams and jellies, ½-inch for fruits and tomatoes to be processed in boiling water, and from 1 to 1 ¼ inches in low-acid foods to be processed in a pressure canner.

This space is needed for expansion of food as jars are processed and for forming vacuums in cooled jars. The extent of expansion is determined by the air content in the food and by the processing temperature. Air expands greatly when heated to high temperatures—the higher the temperature, the greater the expansion. Foods expand less than air when heated.

Jars and Lids

Food may be canned in glass jars or metal containers. Metal containers can be used only once. They require special sealing equipment and are much more costly than jars.

Mason-type jars designed for home canning are ideal for preserving food by pressure or boiling-water canning. Regular and wide-mouthed threaded mason jars with selfsealing lids are the best choices. They are available in half-pint, pint, 1 ½-pint, and quart sizes. The standard jar mouth opening is about 2 ⅜ inches. Wide-mouthed jars have openings of about 3 inches, making them more easily filled and emptied. Regular-mouth decorative jelly jars are available in eight-ounce and 12-ounce sizes.

Handy Household Hints

How to open a jar of fruit or vegetables that has stuck: Place the jar in a deep saucepan half full of cold water, bring it to a boil and allow to boil a few minutes. The jar will then open easily.

With careful use and handling, mason jars may be reused many times, requiring only new lids each time. When lids are used properly, jar seals and vacuums are excellent.

Look for scratches in the glass because while they may appear inconsequential, they could cause breakages and cracking while being processed in a canner. Mayonnaisetype jars are also notorious for jar breakage when being used for foods to be processed in a pressure canner and therefore aren’t recommended. Other commercial jars are also not recommended if they cannot be sealed with twopiece canning lids.

Jar Cleaning

Before reuse, wash empty jars in hot water with detergent and rinse well by hand, or wash in a dishwasher. Rinse thoroughly, as detergent residue may cause unnatural flavors and colors. Scale or hard-water films on jars are easily removed by soaking jars several hours in a solution containing 1 cup of vinegar (5 percent acid) per gallon of water. Jars should be kept hot until they are ready to be filled with food. Submerge the jars in a pot of simmering water (like a boiling water canner or a large stockpot) that can hold enough water to cover them and keep them simmering until it’s time to fill the jars. Alternatively, a dishwasher could be used for the preheating process if the jars are washed and dried on a regular cycle.

Sterilization of Empty Jars

Use sterile jars for all jams, jellies, and pickled products processed less than 10 minutes. To sterilize empty jars, put them right side up on the rack in a boiling-water canner. Fill the canner and jars with hot (not boiling) water to 1 inch above the tops of the jars. Boil 10 minutes. Remove and drain hot sterilized jars one at a time. Save the hot water for processing filled jars. Fill jars with food, add lids, and tighten screw bands.

Empty jars used for vegetables, meats, and fruits to be processed in a pressure canner need not be sterilized beforehand. It is also unnecessary to sterilize jars for fruits, tomatoes, and pickled or fermented foods that will be processed 10 minutes or longer in a boiling-water canner.

Lid Selection, Preparation, and Use

The common self-sealing lid consists of a flat metal lid held in place by a metal screw band during processing. The flat lid is crimped around its bottom edge to form a trough, which is filled with a colored gasket material. When jars are processed, the lid gasket softens and flows slightly to cover the jar-sealing surface, yet allows air to escape from the jar. The gasket then forms an airtight seal as the jar cools. Gaskets in unused lids work well for at least five years from date of manufacture. The gasket material in older unused lids may fail to seal on jars.

It is best to buy only the quantity of lids you will use in a year. To ensure a good seal, carefully follow the manufacturer’s directions in preparing lids for use. Examine all metal lids carefully. Do not use old, dented, or deformed lids or lids with gaps or other defects in the sealing gasket.

After filling jars with food, release air bubbles by inserting a flat plastic (not metal) spatula between the food and the jar. Slowly turn the jar and move the spatula up and down to allow air bubbles to escape. Adjust the headspace and then clean the jar rim (sealing surface) with a dampened paper towel. Place the lid, gasket down, onto the cleaned jar-sealing surface. Uncleaned jar-sealing surfaces may cause seal failures.

Then fit the metal screw band over the flat lid. Follow the manufacturer’s guidelines enclosed with or on the box for tightening the jar lids properly.

• If screw bands are too tight, air cannot vent during processing, and food will discolor during storage. Overtightening also may cause lids to buckle and jars to break, especially with raw-packed, pressure-processed food.

• If screw bands are too loose, liquid may escape from jars during processing, seals may fail, and the food will need to be reprocessed.

Do not retighten lids after processing jars. As jars cool, the contents in the jar contract, pulling the self-sealing lid firmly against the jar to form a high vacuum. Screw bands are not needed on stored jars. They can be removed easily after jars are cooled. When removed, washed, dried, and stored in a dry area, screw bands may be used many times. If left on stored jars, they become difficult to remove, often rust, and may not work properly again.

Selecting the Correct Processing Time

When food is canned in boiling water, more processing time is needed for most raw-packed foods and for quart jars than is needed for hot-packed foods and pint jars.

To destroy microorganisms in acid foods processed in a boiling-water canner, you must:

• Process jars for the correct number of minutes in boiling water;

• Cool the jars at room temperature.

To destroy microorganisms in low-acid foods processed with a pressure canner, you must:

• Process the jars for the correct number of minutes at 240°F (10 PSIG) or 250°F (15 PSIG);

• Allow canner to cool at room temperature until it is completely depressurized.

The food may spoil if you fail to use the proper processing times, fail to vent steam from canners properly, process at lower pressure than specified, process for fewer minutes than specified, or cool the canner with water.

Processing times for half-pint and pint jars are the same, as are times for 1 ½-pint and quart jars. For some products, you have a choice of processing at 5, 10, or 15 PSIG. In these cases, choose the canner pressure (PSIG) you wish to use and match it with your pack style (raw or hot) and jar size to find the correct processing time.

Recommended Canners

There are two main types of canners for heat-processing home-canned food: boiling-water canners and pressure canners. Most are designed to hold seven one-quart jars or eight to nine one-pint jars. Small pressure canners hold four one-quart jars; some large pressure canners hold eighteen one-pint jars in two layers but hold only seven quart jars. Pressure saucepans with smaller volume capacities are not recommended for use in canning. Treat small pressure canners the same as standard larger canners; they should be vented using the typical venting procedures.

Low-acid foods must be processed in a pressure canner to be free of botulism risks. Although pressure canners also may be used for processing acid foods, boiling-water canners are recommended because they are faster. A pressure canner would require from 55 to 100 minutes to can a load of jars; the total time for canning most acid foods in boiling water varies from 25 to 60 minutes.

A boiling-water canner loaded with filled jars requires about 20 to 30 minutes of heating before its water begins to boil. A loaded pressure canner requires about 12 to 15 minutes of heating before it begins to vent, another 10 minutes to vent the canner, another five minutes to pressurize the canner, another eight to 10 minutes to process the acid food, and, finally, another 20 to 60 minutes to cool the canner before removing jars.

These canners are made of aluminum or porcelain-covered steel. They have removable perforated racks and fitted lids. The canner must be deep enough so that at least 1 inch of briskly boiling water will cover the tops of jars during processing. Some boiling-water canners do not have flat bottoms. A flat bottom must be used on an electric range. Either a flat or ridged bottom can be used on a gas burner. To ensure uniform processing of all jars with an electric range, the canner should be no more than 4 inches wider in diameter than the element on which it is heated.

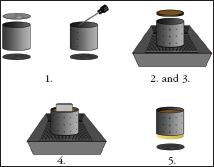

Using a Boiling-Water Canner

Follow these steps for successful boiling-water canning:

1. Fill the canner halfway with water.

2. Preheat water to 140°F for raw-packed foods and to 180°F for hot-packed foods.

3. Load filled jars, fitted with lids, into the canner rack and use the handles to lower the rack into the water; or fill the canner, one jar at a time, with a jar lifter.

4. Add more boiling water, if needed, so the water level is at least 1 inch above jar tops.

5. Turn heat to its highest position until water boils vigorously.

6. Set a timer for the minutes required for processing the food.

7. Cover with the canner lid and lower the heat setting to maintain a gentle boil throughout the processing time.

8. Add more boiling water, if needed, to keep the water level above the jars.

9. When jars have been boiled for the recommended time, turn off the heat and remove the canner lid using a jar lifter, remove the jars and place them on a towel, leaving at least 1 inch of space between the jars during cooling.

Pressure canners for use in the home have been extensively redesigned in recent years. Models made before the 1970s were heavy-walled kettles with clamp-on lids. They were fitted with a dial gauge, a vent port in the form of a petcock or counterweight, and a safety fuse. Modern pressure canners are lightweight, thin-walled kettles; most have turn-on lids. They have a jar rack, gasket, dial or weighted gauge, an automatic vent or cover lock, a vent port (steam vent) that is closed with a counterweight or weighted gauge, and a safety fuse.

Pressure does not destroy microorganisms, but high temperatures applied for a certain period of time do. The success of destroying all microorganisms capable of growing in canned food is based on the temperature obtained in pure steam, free of air, at sea level. At sea level, a canner operated at a gauge pressure of 10 pounds provides an internal temperature of 240°F.

Air trapped in a canner lowers the inside temperature and results in under-processing. The highest volume of air trapped in a canner occurs in processing raw-packed foods in dial-gauge canners. These canners do not vent air during processing. To be safe, all types of pressure canners must be vented 10 minutes before they are pressurized.

To vent a canner, leave the vent port uncovered on newer models or manually open petcocks on some older models. Heating the filled canner with its lid locked into place boils water and generates steam that escapes through the petcock or vent port. When steam first escapes, set a timer for 10 minutes. After venting 10 minutes, close the petcock or place the counterweight or weighted gauge over the vent port to pressurize the canner.

Weighted-gauge models exhaust tiny amounts of air and steam each time their gauge rocks or jiggles during processing. The sound of the weight rocking or jiggling indicates that the canner is maintaining the recommended pressure and needs no further attention until the load has been processed for the set time. Weighted-gauge canners cannot correct precisely for higher altitudes, and at altitudes above 1,000 feet must be operated at a pressure of 15.

Check dial gauges for accuracy before use each year and replace if they read high by more than 1 pound at 5, 10, or 15 pounds of pressure. Low readings cause over-processing and may indicate that the accuracy of the gauge is unpredictable. If a gauge is consistently low, you may adjust the processing pressure. For example, if the directions call for 12 pounds of pressure and your dial gauge has tested 1 pound low, you can safely process at 11 pounds of pressure. If the gauge is more than 2 pounds low, it is unpredictable, and it is best to replace it. Gauges may be checked at most USDA county extension offices, which are located in every state across the country. To find one near you, visit www.csrees.usda.gov.

Handle gaskets of canner lids carefully and clean them according to the manufacturer’s directions. Nicked or dried gaskets will allow steam leaks during pressurization of canners. Gaskets of older canners may need to be lightly coated with vegetable oil once per year, but newer models are pre-lubricated. Check your canner’s instructions.

Lid safety fuses are thin metal inserts or rubber plugs designed to relieve excessive pressure from the canner. Do not pick at or scratch fuses while cleaning lids. Use only canners that have Underwriter’s Laboratory (UL) approval to ensure their safety.

Replacement gauges and other parts for canners are often available at stores offering canner equipment or from canner manufacturers. To order parts, list canner model number and describe the parts needed.

Using a Pressure Canner

Follow these steps for successful pressure canning:

1. Put 2 to 3 inches of hot water in the canner. Place filled jars on the rack, using a jar lifter. Fasten canner lid securely.

2. Open petcock or leave weight off vent port. Heat at the highest setting until steam flows from the petcock or vent port.

3. Maintain high heat setting, exhaust steam 10 minutes, and then place weight on vent port or close petcock. The canner will pressurize during the next three to five minutes.

4. Start timing the process when the pressure reading on the dial gauge indicates that the recommended pressure has been reached or when the weighted gauge begins to jiggle or rock.

5. Regulate heat under the canner to maintain a steady pressure at or slightly above the correct gauge pressure. Quick and large pressure variations during processing may cause unnecessary liquid losses from jars. Weighted gauges on Mirro canners should jiggle about two or three times per minute. On Presto canners, they should rock slowly throughout the process.

When processing time is completed, turn off the heat, remove the canner from heat if possible, and let the canner depressurize. Do not force-cool the canner. If you cool it with cold running water in a sink or open the vent port before the canner depressurizes by itself, liquid will spurt from jars, causing low liquid levels and jar seal failures. Force-cooling also may warp the canner lid of older model canners, causing steam leaks.

Depressurization of older models should be timed. Standard size heavy-walled canners require about 30 minutes when loaded with pints and 45 minutes with quarts. Newer thin-walled canners cool more rapidly and are equipped with vent locks. These canners are depressurized when their vent lock piston drops to a normal position.

1. After the vent port or petcock has been open for two minutes, unfasten the lid and carefully remove it. Lift the lid away from you so that the steam does not burn your face.

2. Remove jars with a lifter, and place on towel or cooling rack, if desired.

Cooling Jars

Cool the jars at room temperature for 12 to 24 hours. Jars may be cooled on racks or towels to minimize heat damage to counters. The food level and liquid volume of raw-packed jars will be noticeably lower after cooling because air is exhausted during processing and food shrinks. If a jar loses excessive liquid during processing, do not open it to add more liquid. As long as the seal is good, the product is still usable.

Testing Jar Seals

After cooling jars for 12 to 24 hours, remove the screw bands and test seals with one of the following methods:

Method 1: Press the middle of the lid with a finger or thumb. If the lid springs up when you release your finger, the lid is unsealed and reprocessing will be necessary.

Method 2: Tap the lid with the bottom of a teaspoon. If it makes a dull sound, the lid is not sealed. If food is in contact with the underside of the lid, it will also cause a dull sound. If the jar lid is sealed correctly, it will make a ringing, high-pitched sound.

Method 3: Hold the jar at eye level and look across the lid. The lid should be concave (curved down slightly in the center). If center of the lid is either flat or bulging, it may not be sealed.

Reprocessing Unsealed Jars

If a jar fails to seal, remove the lid and check the jarsealing surface for tiny nicks. If necessary, change the jar, add a new, properly prepared lid, and reprocess within 24 hours using the same processing time.

Another option is to adjust headspace in unsealed jars to 1 ½ inches and freeze jars and contents instead of reprocessing. However, make sure jars have straight sides. Freezing may crack jars with “shoulders.”

Foods in single unsealed jars could be stored in the refrigerator and consumed within several days.

Storing Canned Foods

If lids are tightly vacuum-sealed on cooled jars, remove screw bands, wash the lid and jar to remove food residue, then rinse and dry jars. Label and date the jars and store them in a clean, cool, dark, dry place. Do not store jars at temperatures above 95°F or near hot pipes, a range, a furnace, in an un-insulated attic, or in direct sunlight. Under these conditions, food will lose quality in a few weeks or months and may spoil. Dampness may corrode metal lids, break seals, and allow recontamination and spoilage.

Accidental freezing of canned foods will not cause spoilage unless jars become unsealed and re-contaminated. However, freezing and thawing may soften food. If jars must be stored where they may freeze, wrap them in newspapers, place them in heavy cartons, and cover them with more newspapers and blankets.

Identifying and Handling Spoiled Canned Food

Growth of spoilage bacteria and yeast produces gas, which pressurizes the food, swells lids, and breaks jar seals. As each stored jar is selected for use, examine its lid for tightness and vacuum. Lids with concave centers have good seals.

Next, while holding the jar upright at eye level, rotate the jar and examine its outside surface for streaks of dried food originating at the top of the jar. Look at the contents for rising air bubbles and unnatural color.

While opening the jar, smell for unnatural odors and look for spurting liquid and cotton-like mold growth (white, blue, black, or green) on the top food surface and underside of lid. Do not taste food from a stored jar you discover to have an unsealed lid or that otherwise shows signs of spoilage.

All suspect containers of spoiled low-acid foods should be treated as having produced botulinum toxin and should be handled carefully as follows:

• If the suspect glass jars are unsealed, open, or leaking, they should be detoxified before disposal.

• If the suspect glass jars are sealed, remove lids and detoxify the entire jar, contents, and lids.

Detoxification Process

Wear rubber or heavy plastic gloves when handling the suspect foods or cleaning contaminated work areas and equipment. The botulinum toxin can be fatal through ingestion or through entering the skin.

Carefully place the suspect containers and lids on their sides in an eight-quart-volume or larger stockpot, pan, or boiling-water canner. Wash your hands thoroughly. Carefully add water to the pot. The water should completely cover the containers with a minimum of 1 inch of water above the containers. Avoid splashing the water. Place a lid on the pot and heat the water to boiling. Boil 30 minutes to ensure detoxifying the food and all container components. Cool and discard lids and food in the trash or bury in the soil.

Thoroughly clean all counters, containers, and equipment including can opener, clothing, and hands that may have come in contact with the food or the containers. Discard any sponges or washcloths that were used in the cleanup. Place them in a plastic bag and discard in the trash.

Canned Foods for Special Diets

The cost of commercially canned special diet food often prompts interest in preparing these products at home. Some low-sugar and low-salt foods may be easily and safely canned at home. However, it may take some experimentation to create a product with the desired color, flavor, and texture. Start with a small batch and then make appropriate adjustments before producing large quantities.

There’s nothing quite like opening a jar of home-preserved strawberries in the middle of a winter snowstorm. It takes you right back to the warm early-summer sunshine, the smell of the strawberry patch’s damp earth, and the feel of the firm berries as you snipped them from the vines. Best of all, you get to indulge in the sweet, summery flavor even as the snow swirls outside the windows.

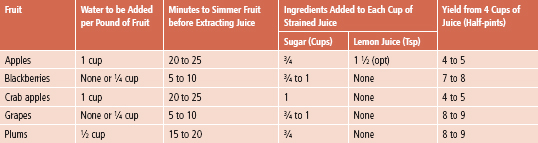

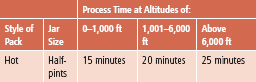

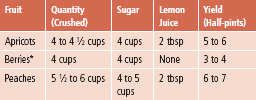

Preserving fruit is simple, safe, and it allows you to enjoy the fruits of your summer’s labor all year round. On the next pages you will find reference charts for processing various fruits and fruit products in a dial-gauge pressure canner or a weighted-gauge pressure canner. The same information is also included with each recipe’s directions. In some cases a boiling-water canner will serve better; for these instances, directions for its use are offered instead.

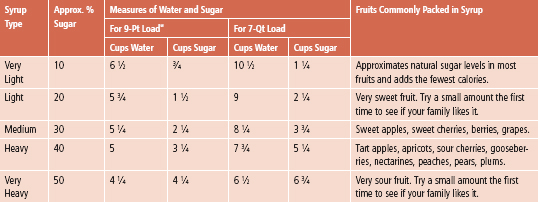

Adding syrup to canned fruit helps to retain its flavor, color, and shape, although it does not prevent spoilage. To maintain the most natural flavor, use the Very Light Syrup listed in the table found on page 60. Many fruits that are typically packed in heavy syrup are just as good—and a lot better for you— when packed in lighter syrups. However, if you’re preserving fruit that’s on the sour side, like cherries or tart apples, you might want to splurge on one of the sweeter versions.

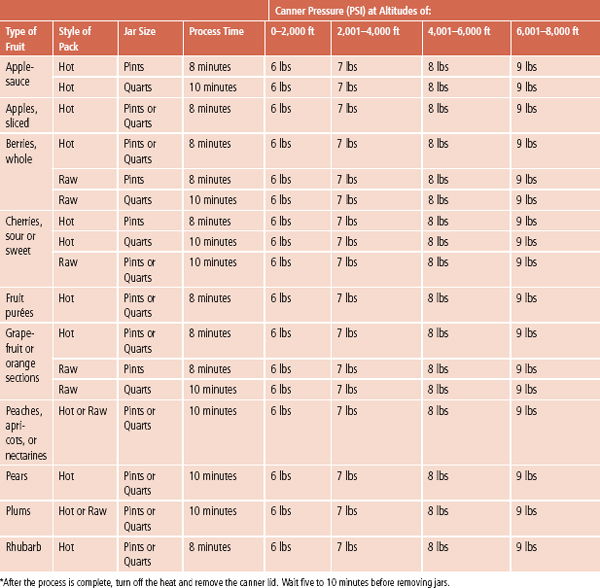

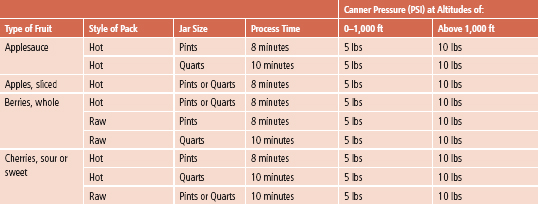

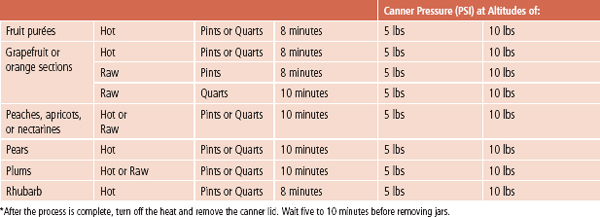

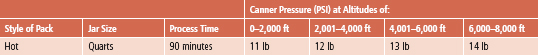

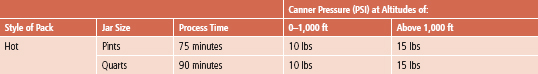

Process Times for Fruits and Fruit Products in a Dial-Gauge Pressure Canner*

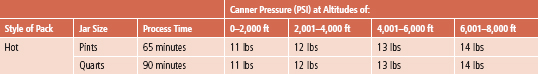

Process Times for Fruits and Fruit Products in a Weighted-Gauge Pressure Canner*

Process Times for Fruits and Fruit Products in a Weighted-Gauge Pressure Canner*

Syrups

Adding syrup to canned fruit helps to retain its flavor, color, and shape, although jars still need to be processed to prevent spoilage. Follow the chart below for syrups of varying sweetness. Light corn syrups or mild-flavored honey may be used to replace up to half the table sugar called for in syrups.

Directions

1. Bring water and sugar to a boil in a medium saucepan.

2. Pour over raw fruits in jars.

For hot packs, bring water and sugar to boil, add fruit, reheat to boil, and fill into jars immediately.

Canning Without Sugar

In canning regular fruits without sugar, it is very important to select fully ripe but firm fruits of the best quality. It is generally best to can fruit in its own juice, but blends of unsweetened apple, pineapple, and white grape juice are also good for pouring over solid fruit pieces. Adjust headspaces and lids and use the processing recommendations for regular fruits. Add sugar substitutes, if desired, when serving.

Apple Juice

The best apple juice is made from a blend of varieties. If you don’t have your own apple press, try to buy fresh juice from a local cider maker within 24 hours after it has been pressed.

Directions

1. Refrigerate juice for 24 to 48 hours.

2. Without mixing, carefully pour off clear liquid and discard sediment. Strain the clear liquid through a paper coffee filter or double layers of damp cheesecloth.

3. Heat quickly in a saucepan, stirring occasionally, until juice begins to boil.

4. Fill immediately into sterile pint or quart jars or into clean half-gallon jars, leaving ¼-inch headspace.

5. Adjust lids and process. See below for recommended times for a boiling-water canner.

*This amount is also adequate for a four-quart load.

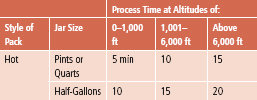

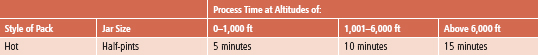

Process Times for Apple Juice in a Boiling-Water Canner*

*After the process is complete, turn off the heat and remove the canner lid. Wait five minutes before removing jars.

Apple Butter

The best apple varieties to use for apple butter include Jonathan, Winesap, Stayman, Golden Delicious, and Macintosh apples, but any of your favorite varieties will work. Don’t bother to peel the apples, as you will strain the fruit before cooking it anyway. This recipe will yield eight to nine pints.

Ingredients

8 lbs apples

2 cups cider

2 cups vinegar

2 ¼ cups white sugar

2 ¼ cups packed brown sugar

2 tbsp ground cinnamon

1 tbsp ground cloves

Directions

1. Wash, stem, quarter, and core apples.

2. Cook slowly in cider and vinegar until soft. Press fruit through a colander, food mill, or strainer.

3. Cook fruit pulp with sugar and spices, stirring frequently. To test for doneness, remove a spoonful and hold it away from steam for 2 minutes. If the butter remains mounded on the spoon, it is done. If you’re still not sure, spoon a small quantity onto a plate. When a rim of liquid does not separate around the edge of the butter, it is ready for canning.

4. Fill hot into sterile half-pint or pint jars, leaving ¼-inch headspace. Quart jars need not be pre-sterilized.

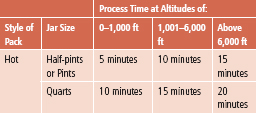

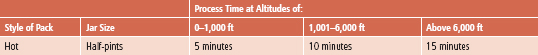

Process Times for Apple Butter in a Boiling-Water Canner*

*After the process is complete, turn off the heat and remove the canner lid. Wait five minutes before removing jars.

Quantity

1. An average of 21 pounds of apples is needed per canner load of seven quarts.

2. An average of 13 ½ pounds of apples is needed per canner load of nine pints.

3. A bushel weighs 48 pounds and yields 14 to 19 quarts of sauce—an average of three pounds per quart.

Applesauce

Besides being delicious on its own or paired with dishes like pork chops or latkes, applesauce can be used as a butter substitute in many baked goods. Select apples that are sweet, juicy, and crisp. For a tart flavor, add one to two pounds of tart apples to each three pounds of sweeter fruit.

Directions

1. Wash, peel, and core apples. Slice apples into water containing a little lemon juice to prevent browning.

2. Place drained slices in an 8- to 10-quart pot. Add ½ cup water. Stirring occasionally to prevent burning, heat quickly until tender (5 to 20 minutes, depending on maturity and variety).

3. Press through a sieve or food mill, or skip the pressing step if you prefer chunky-style sauce. Sauce may be packed without sugar, but if desired, sweeten to taste (start with ⅛ cup sugar per quart of sauce).

4. Reheat sauce to boiling. Fill jars with hot sauce, leaving ½-inch headspace. Adjust lids and process.

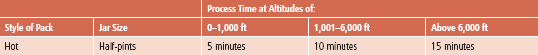

Process Times for Applesauce in a Boiling-Water Canner*

*After the process is complete, turn off the heat and remove the canner lid. Wait five minutes before removing jars.

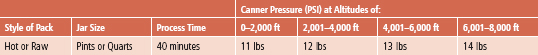

Process Times for Applesauce in a Dial-Gauge Pressure Canner*

*After the canner is completely depressurized, remove the weight from the vent port or open the petcock. Wait 10 minutes; then unfasten the lid and remove it carefully. Lift the lid with the underside away from you so that the steam coming out of the canner does not burn your face.

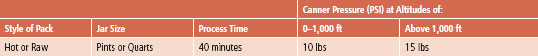

Process Times for Applesauce in a Weighted-Gauge Pressure Canner*

*After the canner is completely depressurized, remove the weight from the vent port or open the petcock. Wait 10 minutes; then unfasten the lid and remove it carefully. Lift the lid with the underside away from you so that the steam coming out of the canner does not burn your face.

Spiced Apple Rings

12 lbs firm tart apples (maximum diameter 2-½ inches)

12 cups sugar

6 cups water

1-¼ cups white vinegar (5%)

3 tbsp whole cloves

¾ cup red hot cinnamon candies or 8 cinnamon sticks

1 tsp red food coloring (optional)

Yield: About 8 to 9 pints

Directions

1. Wash apples. To prevent discoloration, peel and slice one apple at a time. Immediately cut crosswise into ½-inch slices, remove core area with a melon baller and immerse in ascorbic acid solution.

2. To make flavored syrup, combine sugar water, vinegar, cloves, cinnamon candies, or cinnamon sticks and food coloring in a 6-qt saucepan. Stir, heat to boil, and simmer 3 minutes.

Quantity

• An average of 16 pounds is needed per canner load of seven quarts.

• An average of 10 pounds is needed per canner load of nine pints.

• A bushel weighs 50 pounds and yields 20 to 25 quarts—an average of 2 ¼ pounds per quart.

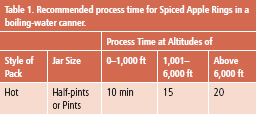

Process time for spiced apple rings in a boiling-water canner.

3. Drain apples, add to hot syrup, and cook 5 minutes. Fill jars (preferably wide-mouth) with apple rings and hot flavored syrup, leaving ½-inch headspace. Adjust lids and process according to the chart below.

Apricots, Halved or Sliced

Apricots are excellent in baked goods, stuffing, chutney, or on their own. Choose firm, well-colored mature fruit for best results.

Directions

1. Dip fruit in boiling water for 30 to 60 seconds until skins loosen. Dip quickly in cold water and slip off skins.

2. Cut in half, remove pits, and slice if desired. To prevent darkening, keep peeled fruit in water with a little lemon juice.

3. Prepare and boil a very light, light, or medium syrup (see page 60) or pack apricots in water, apple juice, or white grape juice.

Process Times for Halved or Sliced Apricots in a Dial-Gauge Pressure Canner*

*After the process is complete, turn off the heat and remove the canner lid. Wait five minutes before removing jars.

Process Times for Halved or Sliced Apricots in a Weighted-Gauge Pressure Canner*

*After the process is complete, turn off the heat and remove the canner lid. Wait five minutes before removing jars.

Quantity

• An average of 12 pounds is needed per canner load of seven quarts.

• An average of 8 pounds is needed per canner load of nine pints.

• A 24-quart crate weighs 36 pounds and yields 18 to 24 quarts—an average of 1 ¾ pounds per quart.