Few books are sufficiently influential to have a lasting impact on a nation’s culture. But in mid-Victorian Britain, two came close to achieving that effect, and both were written at least fifteen years before Darwin’s On the Origin of Species appeared. In different ways, each concerned religious doubt and evolution. Neither book is a household name today, in part because one of them appeared anonymously and generated such heat that the identity of its author remained concealed until years after he had died. The other book, also the cause of serious controversy, was burned at Oxford University before its author, a deacon, was asked to renounce his fellowship.

Tensions over creationism and science had simmered through the 1830s, as Charles Lyell’s notebooks and John Henry Newman’s tracts confirm, but they didn’t ignite until a decade and a half later, when a powerful salvo appeared in 1844 bearing the title Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. It is no exaggeration to say that the book became a widespread topic of conversation across the country, putting doubt at the forefront of countless public, household, and church-based discussions. The book set out to establish what its author called “the mode in which the Divine Author proceeded in the organic creation.”1 Simply thinking about that mode, and calling it one, turned out to be incendiary.

In Victorian Sensation, his vivid account of Britain’s intense reaction to the book, James Secord notes: “It was effectively impossible, only a few weeks after Vestiges [had] appeared, to comment on it without being aware of sharing an experience with a wider national and even international community of readers…. Vestiges was [as Darwin explained] the one book that all readers of the Origin of Species were assumed to have read.”2

Written by the Scots author, editor, and publisher Robert Chambers, Vestiges caused more than a public “sensation”; it sparked one of the most significant cultural discussions of the century, and not just in Britain. It was widely read on both sides of the Atlantic and throughout Europe. In Britain, perhaps a bit surprisingly, readers took to the book enthusiastically, in part because it was well written, but also because it ostensibly rejected atheism. The first newspaper reviews were admiring, calling it, in the words of the Lancet, “a very remarkable book, calculated to make men think.” Others praised not only the “ingenuity” of its argument (Spectator), but also the author’s “extraordinary ability,” “clearness of reasoning,” and “the grandeur of the subjects … he treats” (Atlas).3

Within a few weeks, Vestiges was a major topic of discussion from dinner parties to newspaper columns. Not wanting to miss out on the conversation (and greatly intrigued, it must be said, by the mystery of its authorship), large sections of the reading public felt that it was imperative to peruse it. Even the queen and members of the royal family clamored to get hold of copies. It is not difficult to see why. In bringing together a large number of fields and disciplines, including geology, natural history, phrenology, and chemistry, Chambers offered the latest synthesis. He put before the public what he called “the first attempt… as far as I am aware … to connect the natural sciences into a history of creation” (V, 388).

He was, as it happens, wrong on that and several other important counts: Erasmus Darwin (Charles’ grandfather) had begun to write about evolution as early as the 1780s, in a popular poem called The Loves of the Plants (1789);4 and some of Chambers’ science was eyebrow-raising, to say the least, in remodeling classification groups and suggesting that insects could be created by electricity. Still, as Secord reminds us, the “extraordinary publication, reception, and secret authorship” of Vestiges meant that “evolution moved off the streets and into the home.”5

In doing so, the book generated fierce clerical and scientific reactions. As one reviewer thundered, “To style this book infidel would be pronouncing upon it too mild a condemnation.”6 This was but a foretaste of the hostility that Evangelicals managed to foment around the book. As they turned Vestiges into a symptom of their concerns, including premillennialist fears of the Apocalypse, they implicitly conceded that the book was enormously effective in making people think about a subject that they had largely accepted as biblical. Florence Nightingale wittily observed, “We had got up so high into Vestiges that I could not get down again, and was obliged to go off as an angel.”7 Everyone was either fascinated by the experience or terrified by what it suggested.

With a culture as complex as nineteenth-century Britain’s, it would be rash to try to pin down the moment when scientific and secular works gained enough momentum to affect how the country saw and understood itself. That process took at least three decades, following the influence of debates and discoveries from well over a century before. Still, to focus on the upheaval in mid-Victorian England, when the issue achieved critical mass, major debates in the early 1860s turned out to be turning points for cultural arguments that had flared in the 1830s and begun to attract wide audiences in the 1840s. The primary instigators of those cultural arguments were Vestiges and J. Anthony Froude’s Nemesis of Faith, the second of the two books alluded to earlier.

In the course of those decades, theological explanations for scientific phenomena lost significant ground in Britain, and secular arguments once limited to a relatively small group of freethinkers began to draw greater interest. In her landmark study Varieties of Unbelief, Susan Budd conveys the scale of that interest and widening skepticism by tracking the growing numbers of secularist obituaries in free-thinking journals such as the Reasoner (1852-61), National Reformer (1860-93), Secularist and Secular Review (1876-84), and Freethinker (1881-1968). The first of these had five thousand subscribers in 1853, and with the other journals above it recorded in detail “the conversion experiences of one hundred and fifty secularists …, with supporting evidence from nearly two hundred briefer biographies.” The journals did so, she points out, to refute the popular notion that free thought and unbelief might be fashionable stances in life, but deathbed repentances would ultimately favor Christianity.8

As intellectual, theological, and lay readers struggled to absorb dramatic scientific discoveries, one sign of the ensuing turmoil and transition on both sides of the Atlantic was a growing number of articles on and about religious doubt.9 Their titles shift significantly from pleas for “Deliverance from Doubt” (1857) to more balanced analyses of “Faith, Doubt, and Reason” (1863), as scholars began to weigh doubt’s function, value, and even its ethical necessity.10 One called it “the very mother of a perfect faith.”11 Christianity, in turn, became a major object of inquiry. Scholars wanted to give its practices and history as much close examination as the Church could bear. Mill’s On Liberty (1859) made its history a frequent touchstone for concerns about “the evils of religious or philosophical sectarianism.” “It is,” he wrote, “the opinions men entertain, and the feelings they cherish, respecting those who disown the beliefs they deem important which makes this country not a place of mental freedom.”12

Enlightenment arguments about rationalism, rights, and scientific method had circulated decades earlier, especially in continental Europe. In Britain, moreover, Jeremy Bentham’s Utilitarian approach to religion had gained some traction, identifying followers with criticism of the Church. His approach included estimating the use-value of religious systems and gauging whether “utility” justified their existence.13 Still, such arguments generally circulated among a limited audience of professional and gentlemen scholars largely oriented to biblical and creationist perspectives. A significant lag occurred before German and French Enlightenment texts reached Britain, partly because of publication and translation delays, but also, more fundamentally, because of resistance to their arguments.

The intellectual gap between the Continent and Britain began to narrow in the late 1840s and early 1850s, with progressive journals (the free-thinking Westminster Review, for instance) introducing readers to such philosophers as Arthur Schopenhauer; Auguste Comte, untiring advocate for a secular “religion of humanity,” an attractive concept for religious skeptics; and Ludwig Feuerbach, author of The Essence of Christianity (1841), whose opening section carries the title “The True or Anthropological Essence of Religion.” A growing number of Victorian scientists, drawn to empirical emphasis on method and evidence, also challenged the clergy’s scientific and cultural authority.

It is easy to see why these and related arguments were threatening to British theologians and why they and other scholars tried desperately to keep them at arm’s length. While Comte believed that humanity would progress in three doubt-filled stages, from theocracy to metaphysics before finally reaching a positive phase governed by science and sociology, Feuerbach styled God as “feeling released from limits,” which strongly implied that believers are drawn to doctrinal positions that befit their temperaments. If “God is the highest feeling of self,” in Feuerbach’s terms, then “in God man is his own object,” confronting needs and desires that are very much earthly in origin.14

In her novel Jane Eyre, published six years later in 1847, Charlotte Brontë advanced a similar idea by describing how St. John Rivers’ extreme Calvinism is an extension of his austere temperament, rather than, as many Victorians would have thought, its logical cause. As Rivers “scarcely impressed one with the idea of a gentle, a yielding, an impressible, or even of a placid nature,” he ends up betraying that psychology when asking Jane, while proposing marriage, “Do you think God will be satisfied with half an oblation? Will He accept a mutilated sacrifice? It is the cause of God I advocate: it is under His standard I enlist you.”15 The idea that religious doubt and religious extremism were psychologically inflected was steadily gaining momentum.

Much eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Continental philosophy (by Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, and G. W. F. Hegel, for example) had made doubt and self-questioning integral to how we form judgments. As Robert Flint observed in his 1903 study Agnosticism, “the great revolutions of speculative thought … all originated in extensions of the operations of doubt.”16 Complicating a standard line about the ensuing spread of rationalism, Ayaan Hirsi Ali explains: “Enlightenment thinkers, preoccupied with both individual freedom and secular and limited government, argued that human reason is fallible. They understood that reason is more than just rational thought; it is also a process of trial and error, the ability to learn from past mistakes. The Enlightenment cannot be fully appreciated without a strong awareness of just how frail human reason is. That is why concepts like doubt and reflection are central to any form of decision-making based on reason.”17

A further reason why secular arguments gained while those of theology slipped is the expansion of literacy in the culture. In addition to enlarging the number of people interested in books and ideas, higher literacy rates helped to strengthen long-standing ties in England between working-class radicalism and free thought. That tie had been formed because freethinkers tended to break with aristocratic assumptions about the order of things, including God’s role in orienting the Established Church. As we saw in chapter 2, the secular embrace of evolution by political and religious radicals in the 1820s and 1830s helped pave the way for its later debate among middle-class readers, who could discuss Vestiges’ support for evolution without automatically being thought irreligious. As the demand for books increased and the cost of producing them fell dramatically, the skepticism once limited to David Hume and others gained enough momentum in the culture to become unstoppable.

A third key factor, as we saw in the previous chapter, is that in the 1830s the Church was increasingly splintered and distracted by disputes with Evangelical Methodism and Calvinism. Demands to emancipate Catholicism were at an all-time high. Not surprisingly, Anglicanism was less able to defend itself against the arguments that assailed it—including that religion was part of human discourse, not exempt from its rules and practices.

Finally, Victorian secularism differed greatly from its eighteenth-century precursors. Dramatic gains in scientific understanding had refined methods and standards of proof, making opposition to scientific inquiry look increasingly flat-footed. Chambers’ Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation is a prime example, which helped to make “scriptural geology” sound more outdated than as a neutral description.18 The Church and the scientific establishment took a wait-and-see line with Chambers’ radical claims, clearly hoping that his book would disappear. When the first wave of reviews was overwhelmingly positive and the book became a sensation, a full-on assault took place. The author was publicly denounced as an “infidel” and charged, by furious reviewers, with promoting atheism. A backlash had begun that would take at least two decades to dissipate.

Vestiges was Chambers’ twenty-sixth book, and certainly his best-selling, surpassing even Darwin’s Origin of Species and reaching a twelfth edition by 1884. Most of his other books and pamphlets were histories of Scotland, covering its traditions, ballads, and royalty. But though Vestiges was mostly a departure from Chambers usual subject matter, as a publisher and editor he was well informed about evolutionary theory and able to represent its arguments incisively.

The son of a cotton manufacturer, Chambers set up a printing press with his elder brother, William, printing cheap pamphlets and books, as well as Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal, which soon became influential. Secord notes that it “had a religious target, the evangelical wing of the Scottish Presbyterians. Within the charged world of Scottish theology,” he adds, “the Journals ‘neutral’ position on religious questions sparked intense controversy.”19

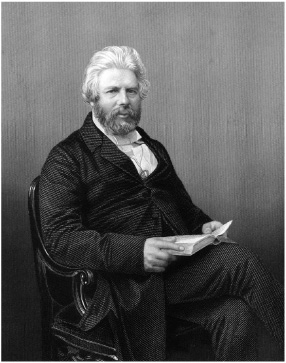

Figure 10. Robert Chambers, a line and stipple engraving by D. J. Pound after Jabez Edwin Mayall, 1860. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

The Chambers family worshipped at a Presbyterian church, but to say that their minister was unhappy with the journal would be putting it mildly. When he held up a copy of it to excoriate, the family and supportive friends walked out en masse. The minister had sermonized that omitting discussion of Christian salvation from a “so-called family periodical” was “tantamount to atheism.”20 According to Secord, “Robert rarely went to services after [that] (how often he had gone before his marriage is not clear), while Anne took the children to the Episcopalian church.”21

Although Chambers’ private correspondence is “fiercely anticlerical,” in Vestiges he was firm, even adamant, that God anchors evolutionary arguments. How we interpret that gap, or whether we detect one, depends heavily on our starting point. Critics of Chambers would see it as bad faith; others, perhaps with Charlotte Brontë in mind, would hold that criticizing the Church as an organization can stem from the strongest piety.

If we view Chambers as ingenuous—as wanting to encourage theological debate from the perspective of a critical believer—we would point to the deism of his argument, a philosophy arguing that God created the world, then left it alone for nature to take its course. Any transmutation among species would thus be written into a blueprint. As Chambers put it, such arguments had to take into account “the original Divine conception of all the forms of being which … natural laws [are] only instruments in working out and realizing” (V, 231).

One can, however, overstate the religiosity of his argument and person. Secord claims that the former was “largely strategic,” to encourage resistant readers to consider an argument they would otherwise rule out of hand. Even more shrewdly, perhaps, Chambers was able to prod the clerisy into debate from the vantage of a religious position.22

Despite his deist position, Chambers supported Lamarck’s theory of species transmutation, an early form of evolutionary theory. He thus incensed critics by accepting what his more cautious fellow Scot Lyell had publicly refuted (and privately agonized over). In his deism, however, Chambers tried to pivot by criticizing Lamarck for inadequately describing a process that Chambers called God given, or at least God orchestrated.

Choosing his words carefully, he sought to clarify precisely “the mode in which the Divine Author proceeded in the organic creation” (V, 153). Not exactly mechanistic, his approach came across as coolly impersonal, conjuring a God more interested in systems than in souls. At the same time, detachment gave Chambers enough flexibility to discuss evolutionary and geological change while appearing to satisfy conservatives demanding that the argument have a religious foundation. “We have seen powerful evidence,” he wrote, Hutton and Lyell very much in mind, that “the earth’s formation … was the result, not of any immediate or personal exertion on the part of the Deity, but of natural laws which are expressions of his will” (153-54). “What is to hinder our supposing,” he added almost mischievously, taking the argument further than either Scotsman before him, “that the organic creation is also a result of natural laws, which are in like manner an expression of his will?”

The echo that Chambers set up with “expression of his will” may have dampened the shock caused by such astonishing sentences, especially as both threaten to end before their reassuring subclauses can modify things heavenward. Without the final clause, for instance, one would read: “The earth’s formation … was the result, not of any immediate or personal exertion on the part of the Deity.”

Perhaps owing to this provocation, the backlash came not from the general public—which was, for the most part, intrigued, almost seduced. It came from religious leaders and the scientific establishment, with scientists attacking Chambers claims about evolution and clergy chastising him for promoting a “rank materialism … [that] may end in downright atheism.”23 The review in which this last charge appeared was vitriolic; the Edinburgh Review also felt it necessary to give the anonymous author (the Reverend Adam Sedgwick, Woodwardian Professor of Geology at Cambridge) eighty-five more pages to explain why Chambers’ argument about evolution was “mischievous, and sometimes antisocial, nonsense.”24 In the same review, Sedgwick also memorably called Lamarck’s theory of species transmutation “as baseless as the fabric of a crazy dream.”25 Not only was Sedgwick equating support for evolution with delusion, even delirium; in doing so, he was entangling science in a new round of metaphors and similes.

To the charge of atheism, Chambers insisted, politely and quite reasonably: “I had remarked in no irreverent spirit, but on the contrary, that the supposition of frequent special exertion anthropomorphises the Deity” (Explanations, 134). He was trading piety with a version of Hume’s warning in Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion that God must be kept austere, to avoid suppositions that he is always at hand, to intervene in even the most mundane details. As Chambers asked in Vestiges,

How can we suppose that the august Being who brought all these countless worlds into form by the simple establishment of a natural principle flowing from his mind, was to interfere personally and specially on every occasion when a new shell-fish or reptile was to be ushered into existence on one of these worlds? Surely this idea is too ridiculous to be for a moment entertained…. Are we to suppose the Deity adopting plans which harmonize only with the modes of procedure of the less enlightened of our race? (V, 154, 157; emphasis in original)

Variants of that assumption of course still exist today, from U.S. football teams that pray for victory before each game to those who insist that God is their group’s or nation’s ally, with truth exclusive to the faithful and damnation likely for almost everyone else.

The Edinburgh Review was merciless in listing Chambers errors, a large number of them compounded by his quirky enthusiasms; but Chambers was quick to capitalize on the higher ground he had seized, insisting that he merely wished to restore dignity to a theological position that would otherwise degrade God. Even when attacking theologians on theology, that is, he managed to sound both pious and, for the most part, humble: “To a reasonable mind the Divine attributes must appear, not diminished or reduced in any way, by supposing a creation by law, but infinitely exalted” (V, 156).

“To a reasonable mind” was one of Chambers’ many ingenious phrases, since it positioned his angriest critics as unreasonable, and thus wrong. Chambers was in fact wrong himself about several speculative matters, including whether plants could grow like frost crystals, dogs could play dominoes, and several other odd notions. Even so, his rhetorical authority makes it seem wise, not blasphemous, to point out that the Book of Genesis is “not only not in harmony with the ordinary ideas of mankind respecting cosmical and organic creation, but is opposed to them” (V, 155).

“When we carefully peruse [Genesis] with awakened minds,” he continued, half-flattering some readers and outmaneuvering others,

we find that all the procedure is represented primarily and preeminently as flowing from commands and expressions of will, not from direct acts. Let there be light—let there be a firmament—let the dry land appear—let the earth bring forth grass, the herb, the tree—let the waters bring forth the moving creature that hath life —let the earth bring forth the living creature after his kind—these are the terms in which the principal acts are described. The additional expressions,—God made the firmament—God made the beast of the earth, &c., occur subordinately, and only in a few instances; they do not necessarily convey a different idea of the mode of creation, and indeed only appear as alternative phrases, in the usual duplicative manner of Eastern narrative. (155; emphasis in original)

According to Chambers, “reasonable mind[s]” will quickly perceive that “the prevalent ideas about the organic creation” were simply “a mistaken inference from the text,” meaning the first verses of the Bible (156).

A quick counterpunch came from Samuel Richard Bosanquet, a wealthy lawyer who in 1845 published two editions of a pamphlet called “Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation”: Its Argument Examined and Exposed. This tract, Secord notes, was advertised prominently across London by placards announcing “that an atheist agitator with a prison record for blasphemy would be speaking on Vestiges.” The agitator in question wasn’t identified, but it obviously was not Chambers, given his continued wish for anonymity as the book’s author. “A year later,” Secord adds, referring to a time when the authorship of Vestiges was still well concealed (though a matter of fierce speculation), “announcements promised an entire series of lectures on the book by the country’s most notorious woman atheist. The audience for such talks rarely exceeded one hundred, but street advertising was, without question, vital to cementing the association of Vestiges with religious disbelief.”26

Among reviewers, too, Vestiges was soon cast as forcing readers to choose between piety and unbelief.27 While the North British Review implied, in Secord’s words, that Vestiges was “parading atheism under a Christian banner,” others were outraged, even to the point of inciting violence.28 The Nonconformist condemned the “infidel” book as a “most erroneous and pernicious work.” Even the moderate and Anglican Christian Observer, decrying the book’s “infidel[,] and even atheistic … tendencies,” declared that it ought to be greeted with “a few sentences of vigourous invective” and a clenched fist.29

To these and many other charges, Chambers fought back diligently and calmly. While catching a number of awkward factual mistakes when revising the book for less expensive editions, he also in 1845 published Explanations: A Sequel, which took on his detractors, offered a robust defense of natural law, and argued that science needed to embrace rather than quell discussion about human destiny and its place in nature.

Many of the more outrageous and ill-informed charges against Vestiges began to take, however. One was that it was written by an amateur merely “paving the way” for Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace, Thomas Huxley, and later, more elaborate theories of evolution based on natural selection. It didn’t help that Darwin himself, with some self-interest and some justification, took the same line, arguing that Chambers did “excellent service in this country in calling attention to the subject [of evolution], in removing prejudice, and in thus preparing the ground for the reception of analogous views.”30 However, that relegates Vestiges to a shadow role before On the Origin of Species, when its impact on the general public was immeasurably greater, as Secord proves so emphatically. Even among scientists in the 1840s and 1850s, one senses that their overreaction to sensitive subjects, like species transmutation, was because Chambers had in fact hit his target most successfully.

Alfred Tennyson was fortunate to order his copy of Vestiges just after the first reviews appeared (the first edition sold out quickly). Diary entries by the future laureate show that he was “quite excited” to get his copy; much later, he insisted that he had found “nothing degrading in the theory.”31

Tennyson saw Chambers as advancing “speculations with which I have been familiar for years, and on which I have written more than one poem.” But Vestiges broke with Lyell’s Principles of Geology (the earlier work that Tennyson alludes to here) over species transmutation. Put another way, it is Chambers, not Lyell, who orients the devastating question in Tennyson’s In Memoriam, “Are God and Nature then at strife?”32 Lyell had struggled mightily to argue that they were not.

Tennyson’s lengthy elegy for friend and fellow poet Arthur Hallam shared with Chambers’ Vestiges the distinction of being one of the most read and most talked about works of the century. And though as we’ve seen Tennyson also went on to characterize nature as “red in tooth and claw,” in a bloodied, proto-Darwinian understanding of natural cruelty, the effect of Vestiges on the Victorian poet was to spark a profound crisis over why such cruelty should occur, in such quantity. Tennyson called the crisis and its apparent solution “honest doubt.” As he declared, ventriloquizing the “perplext… faith” of his once-closest friend and possible lover: “There lives more faith in honest doubt, / Believe me, than in half the creeds.” The elegy presents these lines as Hallam’s response to another’s assumption that “doubt is Devil-born,” a Calvinist premise that Tennyson wanted the Victorians to contest.33 To his own bleakly post-Romantic understanding of nature, however, “honest doubt” was the most—perhaps the only—intelligent way of grappling with his talented friend’s death at the age of just twenty-two.

In rescuing doubt from Calvinist accusations of spiritual weakness and the even sterner rebuke that unbelief was a sin, Tennyson helped to imbue the trait with integrity. In his work, as in several others, the result was greater willingness to ask whether religion had enough answers to explain strong evidence of brutality in nature, including against humanity.

Another budding intellectual strongly influenced by Chambers was James Anthony Froude, younger brother to Hurrell (Newman’s closest friend) and the son of an archdeacon, who read Vestiges as a young fellow at Exeter College, Oxford. Like many other Oxford students swinging, as Secord puts it, “toward liberal divinity or outright unbelief,” Froude found that the book “led him to reject miracles in nature … and [the] divine inspiration of Scripture.”34

Although Froude and Tennyson later became friends, it is unlikely that the younger Froude would have known the poet’s exact thoughts on “honest doubt,” published the year after his own Nemesis of Faith appeared. So it is all the more striking that both writers reacted to Vestiges by calling for, and themselves enacting, candid expressions of religious skepticism. These were bolder, more direct, and far-more personal expressions of religious uncertainty than the culture had yet seen. Tennyson also saw such doubts as having “more faith than … half the creeds,” an obvious provocation in itself. But Froude went further, tackling what he called the “savage fanaticism” of various kinds of “rigid Protestantism.”35

His objections were destined for angry rebuke, though few could have anticipated quite the form it would take. For his candor, Froude suffered the shock and insult of seeing his book burned at his own university. He also entered a legal tug-of-war with the university over the possibility of being charged with perjury. Taking orders to be a deacon was not just a theological commitment; it was a binding legal contract.

Like all deacons in training, Froude had pledged to uphold the Anglican Church’s Thirty-Nine Articles, the source of so much contention throughout the 1830s. Froude had followed those debates closely, given his brother’s close ties to Newman. While he studied at Oxford, however, his own relation to the articles soured. As Froude told fellow novelist and friend Charles Kingsley—and made quite clear in The Nemesis of Faith, his second novel—“I hate the Articles.”36 When he seemed to break them by publishing that work of autobiographical fiction, lawyers seriously discussed whether he could be charged with a crime. In the end, they opted for other forms of punishment, more or less demanding that he resign his fellowship.37 Still, Froude was faced with a dilemma and a significant backlash. “I must live somehow,” he explained in the same letter to Kingsley, “and England is not hospitable.”38

Figure 11. Sir George Reid, portrait of James Anthony Froude, novelist and historian, oil on canvas, 1881. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Although occasionally histrionic, the first half of the novel describes how Markham Sutherland, a doubting clergyman, is exiled from the small British community he tries to serve. The trigger is when a village Bible group denounces him for not referring to the book enough times in his sermons.

Some weeks earlier, Sutherland had in fact begun to harbor doubts about the Church and his faith, but he had tried to follow his friend’s sober advice: self-repression. His tongue-tied syntax says it all: “I think I can do what you say is the least I ought to do—subdue my doubts” (NF, 45). For several months, the practice works. After a “religious tea-party” leads to frank, almost confessional talk of the Bible, however, a few villagers use the opportunity to go on the offensive, declaring of their spiritual counselor “in a tone of satiric melancholy: ‘he never preaches the Bible’” (57, 61). Although he disagrees, insisting, “I believe I read it to you twice every day,” the parishioners are upset and declare, quite seriously, “The enemy is among us” (61, 64).

The village boycotts his services. Tensions rise, and the local bishop asks Sutherland to explain himself. He gives Sutherland a careful hearing as well as a paradoxical answer, common at the time: “Only He who is pleased to send such temptation [in doubt] can give you strength to bear it” (NF, 74).

That premise differs greatly from Sutherland’s more secular and psychological insistence that he is simply one who feels “compelled to doubt” (NF, 81). The gap between these perspectives is telling, even predictive of later trends in the country. Indeed, Sutherland eventually views his doubts as merited, as a healthy predisposition. By his lights, then, to threaten punishment and damnation for such a trait is dangerously extreme, an alarming overreaction to natural questioning.

Sutherland and Froude turn doubt into an ethical rather than a theological category. “Acting upon a doubt” becomes not a sin, Froude says, but a “responsibility,” though one that people often “shrink from” (NF, 85). To his protagonist, that is, doubt requires that one engage with faith and belief, rather than pretend that on both counts all questions are answered and nothing is wrong. In this way, the novel strengthened a growing belief in England that doubt was not a source of evil but an integral component of moral and ethical systems.

In Froude’s case, at least initially, the approach backfired—partly because it was indeed viewed theologically, as a sinful failing. Although he tried repeatedly to explain himself, insisting that with Nemesis, “I cut a hole in my heart and wrote with the blood,” those in positions of authority turned a deaf ear, silently justifying his initial complaint.39 He was not given the kind of hearing at Oxford that Sutherland had received from his bishop. Instead, he encountered a larger audience, both hostile and supportive, when newspapers began reporting on the scandal and reviewing the book that had caused it.

“Why is it thought so very wicked to be an unbeliever?” That is one of the key questions troubling Markham Sutherland (NF, 84). His answer, harnessed to psychology, likens dogma to a group reflex: “Because an anathema upon unbelief has been appended as a guardian of the creed,” he states angrily and inelegantly. “It is one way, and doubtless a very politic way, of maintaining the creed, this … anathema.” Such an outcome is also, he can’t help adding, “vulgar” (84).

Similar charges were leveled at Froude—not only for blanket criticisms of the devout but also for his scattershot dismissal of serious, history-drenched concepts such as “sin,” which at one point Sutherland calls “a chimera” (NF, 92). “The Nemesis is certainly an unpleasant book,” insisted Kingsbury Badger in his 1952 essay “The Ordeal of Anthony Froude.” One of his complaints: the book “exposes a mind perplexed by a jumble of biblical criticism.”40

Froude had in fact absorbed large amounts of scholarship documenting the Bible’s inconsistencies. That is one reason his protagonist doubts that the Bible is infallible, asking pointedly of the faith that the devout place in miracles, “But why do they believe it at all? They must say because it is in the Bible” (NF, 20). Such lines help explain why the novel’s publication was a serious blow to his father, given his position as archdeacon. With Froude’s also visualizing a “religious tea-party” so effectively (57), it is not difficult to imagine the scenes between austere father and wayward son that ensued following publication. Not least was the awkwardness, in the 1840s, of one’s youngest publicly dissecting the weaknesses of the Church while pondering the merits of unbelief.

It was hardly the first time that Froude had disappointed his father, though the man was, by all accounts, notoriously hard to please. Partly as a result, the son’s books are shot through with strongly pronounced father complexes. Sometimes, too, that complex turns father-son relations into a religious allegory, with Froude styling himself almost as an angry Job addressing God the Father alongside his own father in God. But other factors motivated Froude to write, including intellectual doubt about the possibility of miracles, growing concern about the articles that he had sworn to uphold, and the problems that he faced trying to reconcile Genesis with the dozens of historical tracts he was studying.

Chambers’ Vestiges had one impact on writers such as Froude and Tennyson but quite another on popular preachers like the Reverend John Cumming, the firebrand Evangelical from Aberdeenshire, who would have been the first to criticize Froude’s Sutherland for not quoting the Bible enough. In The Church before the Flood (1853), in a passage the future George Eliot would call an “exuberance of mendacity,” Cumming declared, “The idea of the author of the Vestiges is,… that if you keep a baboon long enough, it will develop itself into a man.”41

The author of roughly 180 other books, including Apocalyptic Sketches (1849), The Romish Church, a Dumb Church (1853), and The Destiny of Nations as Indicated in Prophecy (1864), the reverend was a highly influential Calvinist preacher. He found evidence for the End Times, two scholars write, in “everything from the French Revolution to the Irish potato famine to the invention of the telegraph and steamship.” He also thought that the “Christian dispensation would come to a glorious end” circa 1867.42 Although Cumming was something of a crank whose ferocious anti-Catholicism was strongly criticized, he preached each Sunday to a congregation numbering between five and six hundred and was a powerful presence in the National Scottish Church in Covent Garden, central London.

Figure 12. Elliott and Fry, portrait of the Reverend John Cumming, minister of the Presbyterian Church of England, albumen print, 1860s. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Evolution and unbelief were among the reverend’s biggest obsessions. One of his many books, Is Christianity from God? or, A Manual of Christian Evidence (1847)—written, his subtitle asserts, for “scripture readers, city missionaries, Sunday school teachers, &c.”—lambasted what he called the “Creed of the Infidel.” Couched as a satire of the Nicene Creed so often used in Christian liturgy, it states:

I believe that there is no God, but that matter is God, and God is matter; and that it is no matter whether there is any God or not. I believe also that the world was not made, but that the world made itself, or that it had no beginning, and that it will last for ever. I believe that man is a beast; that the soul is the body, and that the body is the soul…. I believe not in the evangelists;… I believe not in revelation; I believe in tradition: I believe in the Talmud: I believe in the Koran; I believe not in the Bible. I believe in Socrates; I believe in Confucius; I believe in Mahomet; I believe not in Christ. And lastly, I believe in all unbelief.43

It would be easy to dismiss this fascinating, self-revealing “web of contradictions,” as George Eliot would later call them; unbelief logically rules out belief in the Talmud and the Koran, as well as the Bible. It is also ludicrous to put failure to “believe … in the evangelists” on a par with interest in the teachings and philosophical traditions of Socrates and Confucius (to do so, even implicitly, highlights the reverend’s grandiosity). But refusal to believe in the Bible was his primary concern. Accordingly, Cumming’s caricature of doubters and atheists renders both, in Eliot’s summation of his words, a type of “intellectual and moral monster… who unites much simplicity and imbecility with … Satanic hardihood.”44

Why bother to engage with Cumming, then? Because the claims and fears that he expressed so often and so vehemently resonated with a large cross-section of the Victorian public. He was, “as every one knows, a preacher of immense popularity,” Eliot explained, who found a way to tap deep-seated fears of change, perhaps especially the idea that science could invalidate belief, rendering it null and void.45 That is one reason Cumming denounced Lord Byron, without irony calling one of his poems “an infidel’s brightest thoughts.” Byron had insisted that “the heart is lonely still,” but death will be a return to “the Nothing that I was / Ere born to life and living woe!”46 To Cumming, that was heresy, plain and simple.

In 1855, several years before she adopted the pen name George Eliot, Marian Evans decided to take on the firebrand preacher in the Westminster Review. She didn’t mince her words. In “Evangelical Teaching: Dr Cumming,” a blistering review of his many books, the future novelist condemned his “tawdry” assertions, “vulgar fables,” and “astounding ignorance” (“ET,” 42, 53, 47). The review article was one of Eliot’s first publications, though she would write several more high-profile reviews on agnosticism and free thought for the Review. She was in an excellent position to do so, having translated the work of such key German philosophers and historians of religion as Ludwig Feuerbach and David Friedrich Strauss.

Though she bore the title of assistant editor, Eliot was editor of the Review in all but name, as John Chapman’s chaotic personal and professional life forced her to assume his responsibilities, too. During her two years at the helm of this progressive intellectual journal, she befriended such regular contributors as the sociologist Herbert Spencer, the scholar-writer Francis William Newman (younger brother to John Henry), and the liberal George Henry Lewes, the man with whom she would soon share a home, though he was married and unable to procure a divorce.47

Founded in 1824 by Jeremy Bentham and James Mill (John Stuart Mill’s father), the Westminster Review was not only a leading proponent of liberalism; it also introduced British readers to major Continental thinkers, and gave important backing to evolutionary theory at a time when it had few public defenders. With the biologist Thomas Huxley comanaging its science section and later reviewing Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, the journal was the first to use the term “Darwinism.” The Review was, in short, one of the periodicals that Carlyle’s Teufelsdröckh had in mind when he called journalists “the true Kings and Clergy” governing Britain. Like several other organs, the Review contributed to a fundamental shift in thinking, including by encouraging greater public acceptance of religious doubt and uncertainty.48

Figure 13. Samuel Laurence, portrait of George Eliot [Marian Evans], 1857. © The Mistress and Fellows, Girton College, Cambridge.

In a joint statement with Chapman about the Westminster Review’s editorial position on religion, Eliot wrote that it would “unite a spirit of reverential sympathy for the cherished associations of pure and elevated minds with an uncompromising pursuit of truth. The elements of ecclesiastical authority and of dogma will be fearlessly examined and the results of the most advanced biblical criticism will be discussed without reservation.”49

Her review article on Cumming was similarly “fearless,” though she published it anonymously, as was customary at the time. A portion of her rebuke was probably personal. As biographer Gordon Haight puts it, the reverend “offered Marian ample ammunition for an annihilating account of the beliefs she had held so earnestly in girlhood.”50 Nor did the ironies end there. To Eliot, the reverend’s aggressive certainty looked suspiciously like a way to silence the religious doubts that had in fact beset him at university.

Eliot began her review article by asking, wittily and bitingly, how one might thrive as a “mediocrity,” so that “a smattering of science and learning will pass for profound instruction, … platitudes will be accepted as wisdom, bigoted narrowness as holy zeal, [and] unctuous egoism as God-given piety” (“ET,” 38). “Let such a man become an evangelical preacher,” she urged impishly, especially if his interpretation of scripture is “hard and literal,” his “insisting on the Eternity of punishment… unflinching,” and his “preach[ing] less of Christ than of Antichrist” (38). In that last phrase, one hears an echo of Jane Eyre’s equal irritation, in Brontë’s celebrated novel of eight years earlier, that the Calvinist preacher St. John Rivers aimed more to scold and terrify his congregations than to minister to their emotional needs.

Eliot’s criticism far-surpassed the Reverend Cumming’s spiritual and emotional dryness. She chided his religious assertions as “slippery and lax” (“ET,” 51). Although he viewed focusing on “evidence” as a “symptom of sinful scepticism,” countless others, she insisted, find “doubt… the stamp of a truth-loving mind” (45, 51). Eliot wasn’t alluding to Tennyson only when she echoed his refrain about honest doubt. She followed with a Latin aphorism of her own that translates: “There are some for whom it is an honour not to have believed, and their unbelief is a guarantee of future faith.”51

Eliot was insistent about the need for doubt because she recognized that Cumming’s brand of certainty was designed to mute serious questions of his own. “I was tainted while at the University by the spirit of scepticism,” he states bluntly in Apocalyptic Sketches: “I thought Christianity might not be true.”52 By calling his doubts a “taint” and speaking about them in the past tense, Cumming obviously hoped to show resilience to readers perhaps plagued by questions of their own. But his phrasing was probably more revealing than he intended. His doubts were so intense that apparently they gave him “no peace till [he] had settled” whether the Bible was authentic. “I … read from that day, for fourteen or fifteen years, till this, and now I am convinced,” he explained, a decade later still, “upon the clearest of evidence, that this book is the book of God as that [from which] I now address you.”53

An “ingenuous mind,” Eliot argued, would engage the arguments of Newton, Linnaeus, Werner, Hutton, and others with “a humble, candid, sympathetic attempt to meet the[ir] difficulties” (“ET,” 52, 42, 52). But because Cumming couldn’t permit that, he opted for a “mode of warfare” that distorts and ridicules the position of these and other skeptics (43): “Everywhere he supposes that the doubter is hardened, conceited, consciously shutting his eyes to the light —a fool who is to be answered according to his folly—that is, with ready replies made up of reckless assertions, of apocryphal anecdotes, and, where other resources fail, of vituperative imputations” (“ET,” 52; emphasis mine).

Reading such lines, one cannot help wishing that Anne Brontë had lived long enough to see them. Certainly, they resonate strongly with her own concerns about Calvinism, in “A Word to the ‘Elect.’”54 In her trenchant criticism, Eliot overturns the oft-stated claim by believers that agnosticism implies a refusal to see the light and accept the Word. Instead, she renders doubt a sign of integrity and honest difference. Either impervious to such criticism or steeled by it, the reverend continued regardless. He published dozens more books, most of them featuring his own version of the apocalypse.

In Hutton and especially Lyell we have traced the personal and intellectual doubts of several key scientists, but Eliot exemplifies midcentury humanistic concerns about the nature of belief, religious and otherwise. Among the nineteenth century’s most talented and respected novelists, she was quite forthcoming about her agnosticism, almost two decades before Huxley coined the term in 1869.55 At the same time, she was widely celebrated for cultivating in her novels an ethic of fellow feeling so ardent that, for some readers, it borders on a “religion of humanity.”56 Certainly, no one could accuse Eliot of letting agnosticism relax her moral strictures. Her life story and philosophy upends the commonplace—still heard today—that religion keeps us in check, to stave off amorality.

Devout in her youth, Eliot was raised by an orthodox Anglican who strongly supported the Tory ideals of church and state. By her early teens, she had filled a notebook with religious verses and added a few of her own, including one called “On Being Called a Saint.” It begins: “A Saint! Oh would that I could claim / The privileg’d, the honor’d name.” The poem hints at a form of self-denial that has pleasures of its own. It also claims to envy the saints their role in “judg[ing] the world … / When hell shall ope its jaws of flame / And sinners to their doom be hurl’d.”57

It would be inaccurate and grossly unfair to view the author of Middlemarch and Daniel Deronda through the lens of such juvenilia, but that early writing does capture a strain of zeal in Eliot’s personality that she was among the first to recognize. The same “stern, ascetic views,” she called them, also motivate a few of her characters, including the young Maggie Tulliver in The Mill on the Floss, who for a while is drawn to acute self-denial even as she reads Keble’s Christian Year (1827), a popular book of poems that celebrated the Christian calendar and “the Church’s middle sky, / Half way ’twixt joy and woe.”58 Yet while Keble’s collection feels too much like a “hymn-book” to move Maggie, Thomas à Kempis, the medieval mystic, is said to give her a “strange thrill of awe” in proclaiming: “Love of thyself doth hurt thee more than anything in the world…. Thou must set out courageously, and lay the axe to the root, that thou mayest pluck up and destroy that hidden inordinate inclination to thyself, and unto all private and earthly good.”59

By the time she could include such passages in her novel, and in part from the sentiment that they convey, Eliot had lost her faith. It left her quickly and decisively. We can almost name the day—January 2, 1842—just after she purchased Charles Hennell’s Inquiry Concerning the Origin of Christianity (1838). Hennell had set out to write a positive book about the role of miracles in the gospels. But after two years’ careful research, he concluded that although Jesus was “a noble-minded reformer and sage, martyred by crafty priests and brutal soldiers,” there was insufficient evidence to support such fundamental matters as his supernatural birth, miraculous works, and resurrection.60 Hume had published similar claims decades earlier, but Hennell was forthright in saying to a larger audience that if Christianity were assessed on strictly empirical grounds, one could explain its formations quite easily through natural law.61

That is where faith takes over, many countered, as belief in something that cannot finally be proven. That Christianity and other religions should be held to standards of material proof was also beside the point, and even part of the problem, because faith transcends rationalism.62 For many Christians at the time, however, including Eliot, it mattered greatly that Christianity have strong historical validity. Otherwise, as in her case, belief in its assertions might come to an end.

Biographer Rosemary Ashton notes of Hennell’s book that Eliot’s copy “has her name inscribed on the flyleaf with the date ‘Jany 1st 1842,’—a most suggestive date,” Ashton continues, “since it was the very next day which she chose for her rebellion against church-going.”63 The decision sparked what Eliot called a “Holy War” with her father,64 during which he “withdr[e]w into a cold and sullen rage.”65 And though she may have begun reading another copy of Hennell’s book slightly earlier, it is striking that thereafter she not only formed a strong friendship with him and his wife, Rufa (as well as his free-thinking sister, Cara Bray, and her husband, Charles), but also decided to translate a biography of Jesus by the German biblical critic David Friedrich Strauss, which advanced an argument quite similar to Hennell’s. That biography, The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined, had been published in Germany in 1835, three years before Hennell’s book came out, though it was unknown to him when he began his own study.

That two books with similarly stated doubts about Jesus appeared within a few years of each other is perhaps less surprising when one considers the growth of interest at the time in historical approaches to the Bible, a form of scholarship known as higher criticism.66 The approach had taken off in Germany at the turn of the nineteenth century, largely because of such powerful early practitioners as Johann Gottfried Eichhorn and Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette. It quickly became a branch of theology with considerable clout in Germany, especially in the university town of Tubingen, near Bavaria.

Higher criticism took several decades to reach Britain. But when it did so, as we shall see, it set off a crisis deeper than even Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859. Eliot, therefore, was forward-thinking, when she referred, in her first published review article four years earlier, to such scholars and their peers as “a large body of eminently instructed and earnest men who regard the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures as a series of historical documents, to be dealt with according to the rules of historical criticism” (“ET,” 49). Without her reviews and translations of such philosophers as Feuerbach and Spinoza, it is also fair to add, the impact of higher criticism on Britain would surely have been slower and weaker.

Conversions of any kind can be abrupt and intoxicating, offering black-and-white distinctions on matters that strike others as containing many shades of gray. Eliot reacted to her loss of faith with a zeal that could be described as either making up for lost time or as an equal and opposite reaction to what she previously had held as true. In a review of Robert William Mackay’s Progress of the Intellect, she protested: “Our civilization, and, yet more, our religion, are an anomalous blending of lifeless barbarisms, which have descended to us like so many petrifications from distant ages.”67 For Eliot, religion had become an anachronism that was holding the Victorians back. It was vital to consider what could replace it.

By the time she began writing fiction full-time, in her late thirties, Eliot had refined her intellectual arguments. By 1854, having translated Spinoza’s Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, a critique of religious intolerance that the Dutch philosopher published anonymously in 1670, she had also finished translating Feuerbach’s Essence of Christianity (1841), the powerful philosophical treatise which argues that God is a projection of humanity’s need for recognition, forgiveness, and love. “Religion is human nature reflected, mirrored in itself,” Feuerbach maintained, and thus “God is the mirror of man.”68 In short, religion is man-made.

Although that sounded blasphemous to many ears, Feuerbach noted quite reasonably of all forms of monotheism that “what faith denies on earth it affirms in heaven; what it renounces here it recovers a hundred-fold there.”69 He also insisted that if Church doctrine were returned to its original human scale, the idea that God Is Love would revert to its foundational premise: Love Is God. Eliot’s 1854 translation of Feuerbach’s fascinating treatise is not only still in print but to this day is considered definitive.

It is through Feuerbach, moreover, that we best make sense of Eliot’s intriguing statement in her review of Cumming, one year later: “There are some for whom it is an honour not to have believed, and their unbelief is a guarantee of future faith” (“ET,” 51; emphasis added). In so writing, Eliot did more than join Tennyson and Froude in restoring integrity (“honour”) to doubt and unbelief; she also extended Froude’s interest in the ethical “responsibility” that follows. And though Eliot’s fiction adds a twist to that move by underscoring the challenges of binding doubt to ethics, rather than to morality, it is only through fellow feeling, her novels show, that the ethic has any chance of succeeding.70

In Silas Marner, to give just one example of the fragility of that compromise, the title character is a simple weaver who lives in a small Calvinist community in rural England called Lantern Yard. He suffers periodically from catalepsy, however, and falls into trances during which he becomes oblivious to what is happening around him.

Taking advantage of his friend’s ailment, William Dane decides to steal the church money while Silas is in a trance. He then blames the theft on his friend by planting Silas knife at the scene of the crime. Adding insult to injury, Dane snags Silas’ fiancée, Sarah, before his former friend is excommunicated from the group and faith he once cherished.

For Silas, the false charges are unbearable: the narrator says that he is “stunned by despair.”71 “God will clear me” is his rallying cry, but when he is banished by “those who to him represented God’s people,” his trust in celestial justice is shattered (SM, 12). After hearing his verdict, he tells his accusers: “There is no just God that governs the earth righteously, but a God of lies, that bears witness against the innocent” (14). Ever quick to seize the opportunity, his erstwhile friend uses the statement to confirm Silas’ guilt: “William said meekly, ‘I leave our brethren to judge whether this is the voice of Satan or not” (14).

Already suffering from acute self-doubt, the weaver tries to take “refuge from benumbing unbelief” by working his way through the crisis (SM, 14). He eventually recovers—even thrives financially—in a nearby village. That is, until one of the squire’s sons decides to steal his savings. Deprived again of what he needs and values, his faith in humanity tested to the limit, Silas is forced to reengage with his neighbors by asking them to help him find the culprit. But although the gold eventually turns up, years later, Silas never achieves redress from Lantern Yard. When he decides to return there, thirty years later, still on the off-chance that something may have surfaced to convince his accusers that he was innocent, he finds a grimy factory where the chapel and house once stood.

Confrontation, clarification, apology: Eliot’s novel makes none of these actions entirely feasible. The “hole” created by the Calvinists accusation remains unanswered and unanswerable. The novel finds other ways to console Silas, including through friendship and love for his adopted daughter, Eppie, but the impression left by the false judgment of the Evangelical community is lasting and severe.

Eliot doubtless drew on some personal experience in representing Silas’ traumatic encounter with his community: When she decided to live unmarried with George Henry Lewes, her brother Isaac infamously cut ties with her for the next twenty-five years (and urged their younger sisters to do the same). He restored their bonds only in old age, after Lewes had died and Eliot had remarried. The scandal that swirled around her and Lewes was all the more intense, ironically, because her first published novel, Adam Bede (1859), printed anonymously, generated intense public interest. When her authorship was finally revealed (after a clergyman, no less, had allowed credit for the work to be attributed to him), the novel quickly turned her into a reluctant celebrity.

Eliot’s “religion of humanity,” we might say, was as tested in life as in her fiction, where a gap opens between religious and secular models that is not easily resolved. Properly established after her loss of religious faith, her ensuing attack on Evangelical zeal, and her deep familiarity with philosophies of religion, Eliot’s secular path was quite similar to Froude’s. She congratulated him for writing The Nemesis of Faith and reviewed his book favorably. To both writers, doubt made free thought a possibility. Indeed, it was by wrestling over what could replace religion that Eliot, Froude, and their close associates found it possible to put their faith and abundant intelligence in a culture that might finally try to do without God.