STAYING THE COURSE

STAYING THE COURSE STAYING THE COURSE

STAYING THE COURSEIf you set out to take Vienna, take Vienna.

—Napoleon Bonaparte, Ulm-Austerlitz Campaign, 1805

For District 17, 1931 was a difficult year. Tom Johnson and Harry Jackson had spent most of it in jail, and stress took a heavy toll on them. Increasingly, Johnson was edgy, short-tempered, and dispirited. He questioned his ability to hold the operation together. In July, after spending four weeks in a dirty and dangerous cell, he petitioned New York to send guns: “We must get them at once,” he wrote. “This is no joke, but it might turn out to be a life or death matter to us. . . . We might have to leave town ahead of a lynch mob.”1

In September, two plainclothes policemen attacked Johnson on a Birmingham street, pushed him into a car, and drove to the county line, where they stripped, beat, and abandoned him. They warned him that if he returned to Birmingham he was a dead man.2 This time he believed them. Johnson subsequently suffered a nervous collapse and was sent back north to recover.

Harry Jackson held things together for the rest of that year, but it was impossible for one man to monitor labor organizing and unemployed council operations for three cities; to keep channels open with the Tallapoosa sharecroppers, who were still without a liaison to headquarters; and to keep track of who’d been arrested and where.

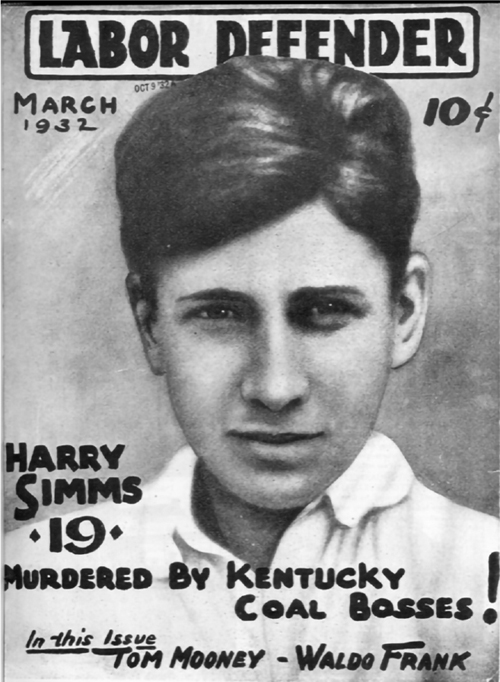

By 1932, so many of Birmingham’s mines, mills, and factories had closed and so many businesses had failed, that a hundred thousand people were out of work and another sixty thousand were employed part-time. The situation was no better in the Black Belt. Mack Coad had gone to Russia for training, and Harry Simms, who’d been working with Tommy Gray’s daughter Eula, had volunteered to go to Kentucky and had gotten himself killed. Eula Gray was a talented organizer in her own right, but she needed help. After the Camp Hill bloodbath, the croppers were becoming increasingly militant.

New York finally stepped in to restructure district 17. They sent thirty-year-old Nat Ross, a Columbia University graduate, to replace Tom Johnson. Harry Jackson introduced Ross to the staff and promised to stay until Ross got himself settled. In the spring of 1932, Jackson left for Pittsburgh to work with the troubled NMU.

Described by one ILD staffer as “a spell binder,” Nat Ross was also a hard worker—he was well organized and a stern disciplinarian.3 Born in Minnesota, he’d learned community organizing working in the Carolinas. Because of the deteriorating economic conditions across the United States, Ross fully expected the revolution to come in his lifetime. He believed that capitalism was experiencing its final crisis, and he would make sure that district 17 was ready for whatever came next. Ross scheduled regular district meetings and was so intense, one comrade said, that his face muscles twitched. He was a respected, if not a beloved leader.

The more laid-back Sid Benson, a twenty-year-old Marxist doctrine specialist, replaced Harry Jackson. Born in Russia, Benson had grown up in New York City. He loved literature, art, and the theater and had a talent for debate and argumentation. Both he and Ross were secular Jews with a lot to learn about black sharecroppers.4

In April 1932 Ross called a one-day conference for Birmingham and Tallapoosa County organizers. He wanted to get the urban and rural comrades talking with one another—some for the very first time. Cropper organizers met with steel and mine worker recruiters, as well as with ILD staff and the unemployed worker council reps. Ross reviewed the district’s new table of organization for them and listed the party’s priorities: interracial organizing, promoting black voter rights, stressing the right to serve on juries and the right of sharecroppers to sell their crops on the open market, and freeing the Scottsboro nine.5

A week later Ross announce formation of an executive committee consisting of himself, Sid Benson, and Lowell Wakefield, and a seven-member operational bureau that included (in addition to the committee members), Hosea Hudson representing the unemployed worker councils and one representative each from the Mine/Mill union, the ore miners, and the steel workers—seven in all: four black and three white comrades. Calling themselves the Political Bureau, they met on Sundays in private homes.6

Ross sent black unit leaders like Hosea Hudson, Henry Winston, Henry Mayfield, Frank Williams, and Al Murphy to the party’s National Training and Worker Schools in New York. Hudson effectively became Ross’s foreman.

On May 1, 1932, the police broke up a crowd preparing to march in the district’s annual May Day parade and followed up with a series of raids. White journalist Blaine Owen and five others were beaten severely and arrested for sedition. At the arraignment, when Owen was asked if he believed in social equality, he assured Judge H. S. Abernathy that he not only believed in it, but that he would rather associate with Negroes than with the police thugs who’d beaten him.7 A spectator in the courtroom shouted “burn them until they turn as black as the niggers they’re so crazy about.”8 After Wakefield arrived with bail, all six were released. This was to be Wakefield’s last official duty in Birmingham. He and his wife Jesse were being sent to Seattle’s district 12 to open an ILD office, and Donald Burke and his wife Alice, who were also white, were coming from Virginia to replace them.

Burke subsequently moved the ILD office to Birmingham to share space. Budgets were tightening. In late May, Ross scheduled another staff meeting to introduce Burke and to review the procedures to follow when comrades got arrested. When Burke returned to his new office, he found it had been trashed. All the files and equipment were destroyed. Don and Alice Burke subsequently sent their infant daughter to stay with Alice’s sister in California, where she remained for three years. Within months, Alice and unemployed worker organizer Wirt Taylor were arrested in Fairfield and spent eight weeks in jail.9 Taylor, a white Alabama native, would later be arrested on an obstructing traffic charge and sentenced to time on a chain gang.

Despite ongoing harassment and violence, Ross, Benson, and Burke kept moving forward. On September 21, they hosted an All Southern Conference on Scottsboro at Birmingham’s Prince Hall (Colored) Masonic Temple. Nearly five hundred delegates filed into the auditorium, and as they were about to begin, police officers entered and ordered everyone to either segregate or disburse. The delegates filed out and regrouped in a nearby vacant lot, where, closely observed by the police, they listened to the speakers. The most popular by far was Viola Montgomery, mother of Olen Montgomery, one of the Scottsboro teens.

In the spring of 1932, Nat Ross had finally appointed a full-time district liaison to the Tallapoosa County Croppers’ and Farm Workers’ Union. Although Eula Gray had been holding the operation together since Coad and Simms left, Ross apparently never considered her for the position. She would continue to organize for the Young Communist League and by 1934 could report to the Central Committee that there were seven functioning YCL units in the county.

Ross had chosen Marcus “Al” Murphy, a black organizer at Birmingham’s Stockholm Pipe and Fitting Company, who’d recently been fired for his Scottsboro advocacy. A year earlier he’d been arrested during the massive manhunt for the killer of two white society women on Shades Mountain. He’d violated the mayor’s curfew and was grilled for hours. When the police demanded the names of his white comrades, Murphy gave up nothing.

He was twenty-five years old, short and stocky, soft-spoken, thoughtful, and very black. Better educated and considerably more militant than Mack Coad, Murphy would work with the Gray family to transform the Croppers’ and Farm Workers’ Union into an underground resistance movement with a new name: the Alabama Share Croppers’ Union (ASCU). This movement would spread beyond Tallapoosa, and by the end of the year locals were operating in Lee, Macon, and Chambers Counties.

Like Harry Haywood, Murphy believed in black self-determination. He divided union members into groups of ten armed men and assigned each unit a coordinating captain. Murphy maintained that he had no problem with eliminating informers. He rationalized that an informer had gotten Ralph Gray killed and others, including a preacher, were responsible for the Camp Hill massacre. There is no evidence, however, that he ever exercised that kind of justice. Merely making his philosophy widely known was apparently effective.10 Camp Hill had clearly marked a turning point. Afterward, no open protests or demonstrations were ever held in Cotton Country. Resistance became the operative term.

Murphy’s greatest challenge was Ross’s dictum to recruit across racial lines. He knew it couldn’t work in the Black Belt. White croppers and tenant farmers had ridden with Sheriff Young’s posse; blacks, not surprisingly, didn’t trust any of them.11 The union’s commitment to racial equality repelled whites, and neither Murphy nor the rank and file were willing to mute it. This commitment was, in fact, one of the chief reasons why black croppers were attracted to the union. Murphy would never agree to soft pedal the party’s social justice demands just to attract white croppers.

Under his guidance, the ASCU expanded into Dallas and Lowndes Counties, into western Georgia, and ultimately into Louisiana. Murphy moved his headquarters from Tallapoosa to Montgomery—to a barbershop on Monroe Street, in the city’s black downtown district. He worked with black party leader John Beans and with Charles Tasker, the black leader of the city’s unemployed worker council movement. Tasker’s wife, Capitola, chaired the Women’s’ Auxiliary. Her “sewing clubs” met over all Montgomery County and built a network for information gathering and distribution.12

The Taskers mimeographed flyers and handbills in the back room of “Al Jackson’s Barbershop.” They updated the black community about the Scottsboro case. Montgomery had been a center for underground organizing ever since the teens’ arrests. Raymond Parks, husband of Rosa, raised money for their defense fund and brought food and clothing to them in Kilby Prison. The Parkses also attended district 17 rallies and helped the Taskers raise bail for jailed croppers.13

Although he remained active in the NAACP, Raymond Parks moved comfortably among radical black circles in Birmingham and Atlanta. Comrades often spent time at his home on South Union Street.14 Rosa recalled armed men sitting around her kitchen table, which was piled high with guns. They talked freely because lookouts were posted at the front and back doors and they all called each other “Larry” to protect their identities.15

In 1932 the Reds were the only activists, black or white, who were willing to work directly with poor blacks. The NAACP focused on pursuing constitutional guarantees through the court system and so worked on behalf of rather than with poor and working-class people. The organization’s initial failure to defend the nine Scottsboro teens had bitterly disappointed Raymond Parks.16

It was likely the Taskers who introduced Al Murphy to the group of white activists in Montgomery who called themselves the Norman Thomas Study Club. It had to be someone who Murphy trusted, and he trusted Charles Tasker. Murphy agreed to meet with them in the summer of 1932 in the basement of Temple Beth Or, across the road from the Montgomery Country Club.

The rabbi, twenty-seven-year-old Benjamin Goldstein, had joined the club in 1931, three years into his tenure at the temple. All the members were pacifists, socialists, or progressives. Bea and Louis Kaufman, who belonged to the Beth Or congregation, led the effort to raise funds for the Scottsboro teens’ appeals.

On March 24, 1932, after the Alabama Supreme Court upheld the Scottsboro convictions and the ILD petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court on the teens’ behalf, Rabbi Goldstein joined Birmingham’s Citizen Scottsboro Aid Committee. Activists coming south to assist the Scottsboro defense found a welcome respite in the homes of the Norman Thomas club members.

They met for weekly discussions ranging from the Scottsboro case and the black sharecroppers’ grievances to the nation’s economic misery and the rise of fascism in Europe. With family and friends living in Germany, some of the Jewish members were concerned about the growing obsession with who “real Germans” were. New German laws defined an individual with three Jewish grandparents as a non-Aryan, and prohibited intermarriage. This echoed the “one-drop-of-blood” criteria used to categorize mulattoes in the South. Adolf Hitler seemed to mirror the South’s obsession with racial purity, its pride in a Lost Cause, and resentment over harsh peace terms.

Those who met with Al Murphy at the temple on March 24 included Louis Kaufman, a wholesale liquor salesman and treasurer of the Schloss and Kahn Grocery Company; Bea Kaufman, president of the local Council of Jewish Women; and Olive Stone, a sociology professor at Montgomery’s Huntingdon College. With the exception of Goldstein, all had been raised in the South. Stone was a member of one of Dadeville’s “first families.” When they asked how they could help, Murphy was clear—he needed bail money.17 They subsequently devised a plan.

Stone would carry envelopes of donated cash to the downtown post office, leave them on a prearranged counter, and wait for Murphy to retrieve them. This was clearly a risk to Murphy’s life and to her continued employment.18 Invariably, as they worked together, Murphy came to trust the professor, the rabbi, and the Kaufmans.

Two years earlier, the Tennessee Valley Authority had awarded Stone a grant to write a social history of the Tallapoosa County sharecroppers. During a stay in Dadeville, she’d met Sid Benson, who was working with union members there. She was charmed by this young man who shared her passions for literature, theater, and politics. They discussed and debated aspects of southern culture and the role of privileged planters (like her late father) who Benson called colonial exploiters.

After Benson brought Stone to a cropper union meeting, she invited him to a study club session.19 When he and Nat Ross came to Montgomery to consult with Murphy, they also attended a club meeting. Afterward, Ross returned to Birmingham, but Benson stayed on to speak with the rabbi. Bea and Louis Kaufman provided him room and board.

After Benson left, the rabbi began speaking more forcefully about the plight of the Tallapoosa sharecroppers. Several of Beth Or’s trustees reminded him that when he was hired he’d agreed to “leave the Negro question alone.” Wasn’t it enough that he’d angered so many in the congregation with his loose talk about the Scottsboro affair?

Most temple members contributed generously and faithfully (if anonymously), to Negro uplift, relief, and humanitarian causes, but they worried about their identities being discovered and their generosity being misunderstood as an endorsement of integration. The enthusiastic rabbi was strongly encouraged to be more circumspect.

In July 1932, the study club welcomed twenty-two-year-old Jane Speed and her mother, Mary Craik (Darlie) Speed. Rabbi Goldstein likely extended the invitations. His neighbor, Dr. Charles Pollard, was Darlie’s brother-in-law. Darlie Speed was a member of Montgomery’s white, wealthy, and progressive Baldwin clan. Martin Baldwin, her grandfather, had presided over the Mobile and Montgomery Railroad, the First National Bank, and the Country Club. Her younger sister, Jean Read, was a popular socialite, and Jean’s husband, Nash, a freelance journalist, was rumored to be a Red. The Nashes hosted garden parties and held formal teas at Hazel Hedge, their twenty-acre estate in the heart of the Cloverdale district.20

Darlie had scandalized the family in 1917 by divorcing her physicist husband, James Buckner Speed, and moving to New York City. Later she took her children Jane and William to live in “Red Vienna.”

In 1931 Darlie and Jane returned to Montgomery and became friendly with Rabbi Goldstein, the only white clergyman who regularly visited the Scottsboro teens.21 He’d managed to convince the warden that he was their spiritual advisor.22

Most of the study club members—the Kaufmans, Dorothy and Bernard Lobman, and Sadie Franks (all from Beth Or), Olive Stone, and several high school teachers and social workers—called themselves pacifists, socialists, or Marxists. Many of the women were also active in the local chapter of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. The Speeds, however, were Communists and didn’t care who knew it.

In September 1932, during Yom Kippur, Rabbi Goldstein assured his congregation that the nine Scottsboro teens were innocent. When his trustees chided him again for introducing politics into the service, especially on the highest of holy days, Goldstein responded that “one could not speak of social justice and then stand on the sidelines when the limits of fairness were being tested.”23 This time they were truly angry, and they weren’t going to warn him again.

Montgomery’s elite, and those who aspired to breathe their rarified air, defended strict racial etiquette. Grover Hall, white editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, while predictably intolerant of disrespect from blacks, made excuses whenever his own black employees lied, stole, or wasted time because he believed that they didn’t know any better. Although he despised the KKK and had won a 1928 Pulitzer Prize for his editorials exposing them, he was adamant about keeping blacks out of the voting booths since they vastly outnumbered whites in the Black Belt.24 Hall was also convinced that the Scottsboro teens had received a fair trial and that sensible white southerners understood that they could take the race issue only so far.

That summer, Hall published letters from readers who were concerned about the persistent rumors that the Tallapoosa croppers were organizing again. Camp Hill apparently hadn’t convinced them to give up their demands for written contracts, cash settlements, and marketing their own crops. Hall maintained that they’d been indoctrinated by the Reds. It had to be the Reds because he was convinced—as was most of white Alabama—that, left to their own devices, blacks had neither the desire nor the capacity to be defiant.25

Hall published those letters the same week that Janie Patterson, mother of Scottsboro defendant Haywood Patterson, addressed a rally in Harlem, New York: “Many have tried to tell me the ILD was low-down whites and Reds . . . but I have faith that they will free [my son] if we all unite behind them. . . . I don’t care whether they are Reds. . . . They are the only ones who put up a fight to save these boys and I am with them to the end.”26

Sharecropper prayer meeting house, Hale County, Alabama, 1936. Photo by Walker Evans. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF342-T01-008149-A.

Sharecropper prayer meeting house, Hale County, Alabama, 1936. Photo by Walker Evans. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF342-T01-008149-A.

Sharecropper cabin, Hale County, Alabama, 1936. Photo by Walker Evans. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF342-T01-008156-A.

Sharecropper cabin, Hale County, Alabama, 1936. Photo by Walker Evans. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF342-T01-008156-A.

Sharecropper family working near Anniston, Alabama, 1936. Photo by Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF34-009325-C.

Sharecropper family working near Anniston, Alabama, 1936. Photo by Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF34-009325-C.

Sharecropper’s children, Montgomery County, Alabama, 1937. Photo by Arthur Rothstein. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF34-025351-D.

Sharecropper’s children, Montgomery County, Alabama, 1937. Photo by Arthur Rothstein. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF34-025351-D.

Al Murphy, Sikeston, Missouri, 1977. Southern Oral History Program Collection, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Al Murphy, Sikeston, Missouri, 1977. Southern Oral History Program Collection, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Angelo Herndon with Robert Minor (front left) and James Ford (front right). From the photo collection held at the Tamiment Library, New York University, by permission of the Communist Party USA.

Angelo Herndon with Robert Minor (front left) and James Ford (front right). From the photo collection held at the Tamiment Library, New York University, by permission of the Communist Party USA.

Bull Connor, Birmingham, Alabama, commissioner of public safety. Courtesy of Birmingham Public Library.

Bull Connor, Birmingham, Alabama, commissioner of public safety. Courtesy of Birmingham Public Library.

Earl Browder, National Secretary, CPUSA, 1934. From the photo collection held at the Tamiment Library, New York University, by permission of the Communist Party USA.

Earl Browder, National Secretary, CPUSA, 1934. From the photo collection held at the Tamiment Library, New York University, by permission of the Communist Party USA.

Alabama Governor Bibb Graves. Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group.

Alabama Governor Bibb Graves. Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group.

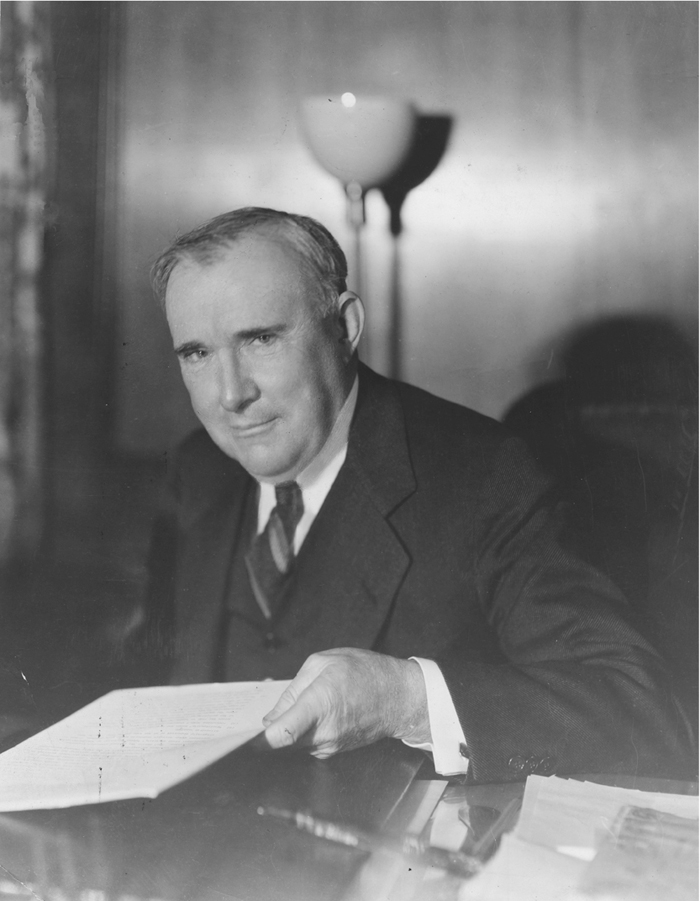

Grover C. Hall Sr. Editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, 1926–1941. Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group.

Grover C. Hall Sr. Editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, 1926–1941. Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group.

Harry Simms, front cover of Labor Defender, March 1932. From the collections of the Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Harry Simms, front cover of Labor Defender, March 1932. From the collections of the Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Hosea Hudson, arrested for vagrancy in Birmingham, 1932. Southern Oral History Program Collection, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Hosea Hudson, arrested for vagrancy in Birmingham, 1932. Southern Oral History Program Collection, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Jane Speed, Puerto Rico, 1954. Courtesy of Aurora Levins Morales.

Jane Speed, Puerto Rico, 1954. Courtesy of Aurora Levins Morales.

Private James Allen, 1942. Courtesy of Jesse Auerbach.

Private James Allen, 1942. Courtesy of Jesse Auerbach.

Rabbi Benjamin Goldstein and daughter Josie, Montgomery, Alabama, 1931. Courtesy of Josie Goldstein Rogers.

Rabbi Benjamin Goldstein and daughter Josie, Montgomery, Alabama, 1931. Courtesy of Josie Goldstein Rogers.

Scottsboro Boys and attorney Samuel Leibowitz. Standing from left to right: Olen Montgomery, Clarence Norris, Willie Roberson (front), Andrew Wright, Ozie Powell, Eugene Williams, Charley Weems, and Roy Wright. Haywood Patterson is sitting next to Samuel Liebowitz. Morgan County Archives, Decatur, Alabama.

Scottsboro Boys and attorney Samuel Leibowitz. Standing from left to right: Olen Montgomery, Clarence Norris, Willie Roberson (front), Andrew Wright, Ozie Powell, Eugene Williams, Charley Weems, and Roy Wright. Haywood Patterson is sitting next to Samuel Liebowitz. Morgan County Archives, Decatur, Alabama.

Ruby Bates testifying at Haywood Patterson trial, March 1933, Decatur, Alabama. Morgan County Archives, Decatur, Alabama.

Ruby Bates testifying at Haywood Patterson trial, March 1933, Decatur, Alabama. Morgan County Archives, Decatur, Alabama.

Victoria Price, Haywood Patterson trial, March 1933, Decatur, Alabama. Morgan County Archives, Decatur, Alabama.

Victoria Price, Haywood Patterson trial, March 1933, Decatur, Alabama. Morgan County Archives, Decatur, Alabama.

Walter F. White, National Secretary NAACP, 1949. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Visual Materials from the NAACP Records, LC-DIG-ds-13132.

Walter F. White, National Secretary NAACP, 1949. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Visual Materials from the NAACP Records, LC-DIG-ds-13132.

Charles Hamilton Houston, NAACP Legal Defense Fund, 1939. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Visual Materials from the NAACP Records, LC-DIG-ds-13133.

Charles Hamilton Houston, NAACP Legal Defense Fund, 1939. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Visual Materials from the NAACP Records, LC-DIG-ds-13133.