11 Making Your Move

The software pioneer Adobe became a global success by selling its offerings under the simplest of models: a plastic disc in a cardboard box. A user paid upfront for a perpetual license to use the company’s software products. By early 2013, Adobe was generating $1 billion in revenue per quarter and earning a net profit margin of 19 percent. Fueled by consistent growth since the Great Recession, Adobe’s stock price stood at a five-and-a-half-year high.1

Under those circumstances, few people would expect senior management to do much tinkering. After all, if the business ain’t broke, why fix it? Rarer still would be to expect senior management to implement a bold plan likely to cause revenue growth to stall and profits to plummet in the short term.

Yet that is precisely what Adobe did. At its MAX conference in May 2013, the company dropped a bombshell. It would cease to sell a host of creative products—including Acrobat, Illustrator, InDesign, and Photoshop—on the basis of a perpetual license and, instead, offer them through a new subscription service it dubbed Creative Cloud. In other words, Adobe would make an immediate and full commitment to a revenue model focused on access rather the traditional one based on outright ownership.

“We believe we are at a key inflection point in the history of digital communications.” This statement in Adobe’s 10-K filing for the 2012 fiscal year hinted at the rationale behind the forthcoming change. David Wadhwani, Adobe’s senior vice president and general manager of digital media, elaborated on the logic for the switch when he said that it would allow the organization to “put innovation in our members’ hands at a much faster pace.” Wadhwani added that, under the new subscription model, customers would receive enhancements on an ongoing basis, have access to the full range of Adobe’s creative tools, and interact online with a community of peers.2

Adobe also recognized that such a bold move would not prosper if it left the market to its own devices. To make the benefits of Creative Cloud clear to potential customers, the organization undertook a broad promotional campaign. It set a goal to have face-to-face meetings with fifty thousand customers at events around the world to win them over. “We understand this is a big change, but we are so focused on the vision we shared for Creative Cloud, and we plan to focus all our new innovation on the Creative Cloud,” explained Wadhwani, adding that “customer satisfaction for users using Creative Cloud has been off the charts.”3 Adobe also reached out to the investing community, stressing the need to be patient. The pitch to investors intended to make clear that Adobe was not adding uncertainty or instability unnecessarily. Rather, the organization was pushing a consistent stream of medium-term revenue into the future in exchange for tighter, longer-lasting relationships with customers. In fact, the more Adobe “lost” in the short term, the more it would earn in the future because it was replacing high, one-off revenue with a potentially perpetual stream of smaller monthly payments.

The abrupt switch to subscription, backed by that critical educational campaign with customers and investors, worked out as planned and ultimately helped Adobe reach new heights. By 2014, the anticipated short-term financial declines took hold, as revenues dropped by 6 percent and net profit by 67 percent from the peaks in 2012. But that period was followed by sustained improvements that would have been inconceivable had the organization clung to its historical pay-to-own model. Between 2014 and 2018, Adobe’s revenue and profits increased at compound annual growth rates of 21 percent (to reach over $9 billion in absolute terms) and 76 percent, respectively. Even more impressive is the change in Adobe’s market capitalization. In late June 2013, around one month after the MAX Conference at which Adobe announced the change to the subscription revenue model, its market capitalization stood at $22.5 billion. By September 2019, it increased by a factor of six to $134.5 billion.

When Innovation Is Wasteful

It seems almost trivial to claim that an organization benefits from introducing innovations that make customers better off. Yet the Ends Game challenges this statement, stressing that satisfying customers does not in itself guarantee success. Rather, an organization improves its chances of profiting from the innovations it brings to market as it adopts a revenue model that addresses the access, consumption, and performance problems that create waste in the exchange. The experience of Adobe and its shift to Creative Cloud supports this idea.

The successful, thirty-year-old software company from San Jose, California, had looked into the crystal ball and recognized that the traditional ownership model would soon become an impediment to its growth. Technological advances had exposed an important limitation of selling ownership in this sector: it is an inefficient, impractical means to make a steady stream of innovative products and services available to customers. Rather than trying to find a way to win within the status quo, Adobe imagined a different future, one in which it would hold itself more—but not fully—accountable for the promises it makes customers. It implemented a revenue model that essentially guarantees access to innovation.

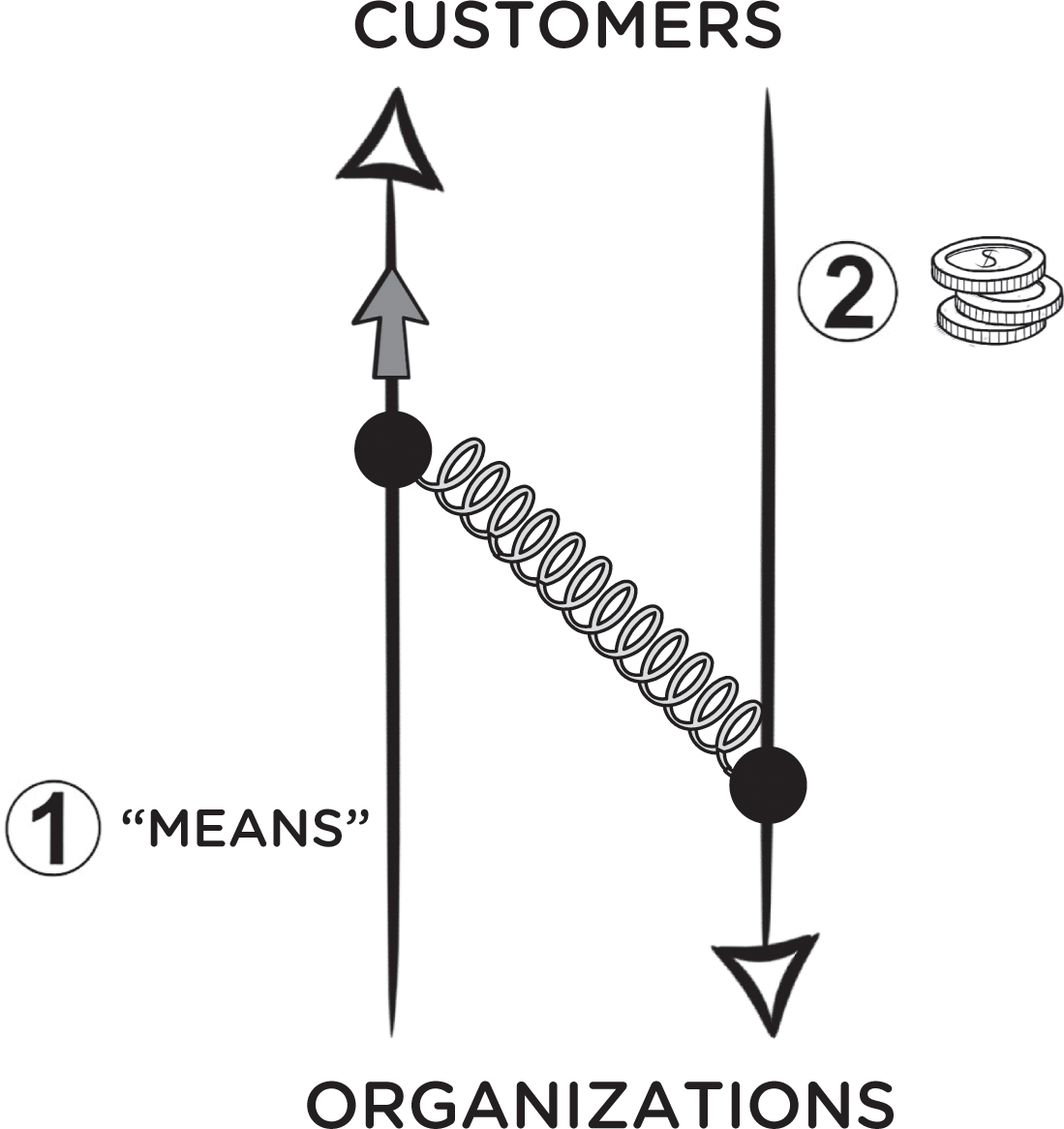

Figure 11.1 illustrates the rationale behind Adobe’s decision. The left line represents the value an organization delivers to customers via its products and services. The point on that line moves up as the organization introduces offerings that are increasingly meaningful to customers. On the other hand, the right line represents the revenue the organization generates from the exchanges with customers. The point on that second line moves up as the organization adopts a revenue model that is more efficient—that is, a revenue model that takes on increasing responsibility for possible access, consumption, and performance problems.

Organizations exist to (1) satisfy customers via their products and services and (2) earn revenue from them. Being closer to customers is great for the first task, but it creates inefficiency if the organization’s revenue model does not follow suit.

The spring connects the two points, and its tension captures the misalignment between the processes. The better a company understands what customers need and want, and the better it engineers their decision journeys, the more value it can theoretically deliver. Translating these insights into actual offerings and commercial actions moves the left part of the spring toward the top. However, if the revenue model does not make the organization accountable to its promise of superior value, the right part of the spring is “stuck” toward the bottom and waste is created. Adobe was in a position to launch such a stream of innovations in 2013, but it could not sell them effectively because the ownership model made them inaccessible.

An organization has two options to relieve the tension in the spring. First, it can cut back on its efforts to please customers—care less about understanding and satisfying their needs and wants or about engineering successful decision journeys. This is clearly a nonstarter. Second, the organization can revisit the revenue model, thinking about the waste created by forcing ownership, and changing the metric accordingly. Adobe ultimately made an aggressive move with objectives well aligned with what we have described in this book. The company believed that “market conditions presented significant opportunities … to rapidly deliver product innovation, access new market segments, increase engagement with our customers, transition our business to promote a recurring revenue model, and accelerate our revenue growth.”4 Access models, thanks to the direct ongoing interaction with customers, can help companies introduce digital innovations faster, beat competitors to the market, and collect more and better feedback from customers sooner.

The misalignment and resulting tension shown in figure 11.1 are what Adobe saw when it looked into the crystal ball. The improvements offered by Creative Cloud, including the connectivity advantages and the flexibility conferred by cloud storage, created so much value for customers that the spring would have come under too much tension. Had Adobe insisted on sticking with the perpetual license model, it would have constrained its own ability to innovate and charge customers for it. It would have also made it virtually impossible for Adobe to bring further innovations to customers in a timely manner.

Adobe demonstrated that playing the Ends Game is worthwhile. But its decision to switch revenue models abruptly is not the only viable approach to relieving tension in the spring. Some companies decide to let old and new revenue models operate in tandem for some time in order to smooth the transition.

A Better Way to Buy Ink

Raise your hand if you have ever run out of ink or toner at work when you urgently needed to print a document. The relationship between a printer and its ink cartridges is structurally the same as the “razor and blades” model pioneered by Gillette we discussed in chapter 4.5 Like the case of Gillette, the custom of selling ink cartridges on a pay-to-own basis creates access waste that leaves customers frustrated and, in the worst cases, without the ability to print what they need, when they need it. Buying ink cartridges historically has been a frustrating and inconvenient process, never mind an expensive one.

Unlike Gillette, however, HP seized the initiative and transformed its own business by launching a subscription program called Instant Ink. Under the Instant Ink program, the printer itself tracks ink levels and reorders cartridges when needed.6 Monthly fees for the various plans are based on the number of pages the user prints per month. The printed pages could be anything the user desires, from black-and-white documents to color pages or photos downloaded from a phone. With respect to photos, HP hoped that easier and more convenient access to ink would help drive consumption. “We believe that many of the photographs taken today are in the digital jail,” HP’s current CEO Enrique Lores was quoted as saying. “You take many, many pictures, but you never take them out again. We want to release them.”7

Instant Ink, which debuted in 2013, shares many elements with programs in other industries designed to broaden access. It has a value proposition that explicitly identifies a frustrating problem and offers a convenient solution. The user no longer needs to worry about when to restock ink, or worry about making emergency runs to an office supply store to pick up a cartridge. Critically, the metric underlying the revenue model is no longer ownership, but time. In fact, because subscribers can carry over unprinted pages from month to month, Instant Ink effectively morphs into a consumption model where the metric is the number of pages printed rather than monthly access.

According to one report, Instant Ink attracted two million subscribers by the end of 2017.8 On the company’s earnings call with analysts in February 2019, Dion Weisler, the then president and CEO of HP, said that the Instant Ink subscriber base “continues to have impressive growth. We have now rolled out the program in 18 countries and continue to see strong adoption rates.”9 But HP, unlike Adobe, did not make a wholesale, sudden switch to Instant Ink. Rather, customers who needed ink could still purchase it the old-fashioned way by visiting a local retailer or going online.

Generally speaking, operating multiple revenue models at the same time raises two important issues. First, when given a choice, existing customers will switch to whatever revenue model makes them better off. This will probably improve retention and ultimately steal share from competitors, but it also implies that the short-term impact on sales to existing customers is negative, which in turn can create friction inside an organization that is caught off guard. For example, although HP decided to maintain the traditional “pay-per-cartridge” model as it introduced Instant Ink, what happens if the subscription program prompts a significant cannibalization of existing sales? This can create animosity between teams, with the established unit responsible for cartridges perhaps doubting the logic of a new revenue model if it implies “shooting oneself in the foot.” Internal politics clearly matter and must be managed, keeping in mind both the short-term consequences of giving customers options and the desired long-term benefits of making the transition to a more efficient revenue model. Equally important is the careful calibration of the prices used under each revenue model, so that cannibalization is not rampant.

Second, assuming that two or more revenue models should not coexist indefinitely because they result in different levels of efficiency, what is the actual transition plan? If the organization thinks only of the efficiency gains that come from aligning the metric by which it earns revenue with the way customers derive value, then the goal is to transition away from ownership as quickly as the size of the opportunity demands. But the organization must also account for the different costs of making this transition—including the actual costs of retiring the old revenue model and introducing the new one, the likely opportunity costs, and so on. The nature of the products (physical vs. digital), the pace of technological change in the market, and beliefs about how long it will take customers to change habits are likely to be important factors in this calculus. Consistent with this idea, HP faces a much different environment than Adobe does. Adobe’s product is a digital one, which made the direct and complete switch to Creative Cloud a reasonable move. But HP sells a tangible, physical good. Adobe also faced a much faster pace of technological change than HP does.

The Many Faces of Internal Resistance

Any organization, regardless of its position in the market, ultimately needs to examine the gap between the value it creates for customers and the way in which it earns revenue for itself. The opportunity to eliminate waste by loosening the tension in the “spring” and gradually bringing the revenue model in line with the outcomes customers desire is universal. However, when it comes to rethinking the revenue model, companies typically face considerable internal resistance—a dangerous mix of inertia, neglect, myopia, and fear of change. The challenge is to identify the root causes, motivate senior leadership to act, and then guide the organization through the transition.

Sir Isaac Newton defined inertia in his first law of motion, when he stated that “every object will remain at rest or on its current trajectory unless compelled to change its state by the action of an external force.”10 If we wanted to convert this statement into Newton’s first law of strategy, then we would need to make two substantial changes: Every company will remain at rest or on its current trajectory unless compelled to change its state by the actions of external and internal forces. In commerce, the external force that often overcomes inertia is technology, which in the context of revenue models is creating the unprecedented opportunities we first described in chapter 2. But this remains little more than untapped potential unless the organization makes a conscious decision to address the inefficiency that currently exists in the exchange with customers, no matter how safe or comfortable the status quo may feel.

Similarly, neglect or outright myopia may also block an organization from taking swift action. These factors can lead a company to focus on improving an existing but inferior process rather than striving to rethink the process altogether. As Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos explained in his 2016 letter to shareholders: “As companies get larger and more complex, there’s a tendency to manage to proxies. This comes in many shapes and sizes, and it’s dangerous, subtle.” This comment relates to the notion of surrogation we cited in chapter 9 to explain the roots of the quality paradox. But Bezos goes a step further than merely talking about how metrics may grow to supersede the underlying goals they are meant to measure, and describes how entire processes can become all-consuming: “If you’re not watchful, the process can become the thing. The process becomes the proxy for the result you want. You stop looking at outcomes and just make sure you’re doing the process right.”11

Finally, common business clichés provide convenient comebacks when people are confronted with the possibility of making a change as major as a shift in the revenue model. They will worry about the risks, because the step appears too much of a departure from “the way we’ve always done things.” For example, the prospect of cannibalization is a recurring argument against acting. Why should the company give customers an opportunity to pay less? Isn’t this a case of that familiar expression “the cure is worse than the sickness”? Especially in the age of viral social media, managers in an organization may worry excessively about how customers will respond and how the changes might affect the investing community. Yet when an organization feels comfortable with processes and patterns of behavior, these are hard to challenge and harder still to change. The resistance is stronger for incumbents, which carry the burden of past decisions, than it is for startups, which are free from any legacy.

Getting It Right

There are many reasons why established organizations are reluctant or hesitant to summon that internal “force” needed to change their revenue model—a move tantamount to changing the very nature of how they make a living in the market. However, as we said in the introduction, accountability is no longer a fashionable marketing slogan. It is a strategic imperative, and an organization’s choice of revenue model determines the extent to which it holds itself to account for the promises it makes to customers.

In our mind, this choice is important and needs to be inspired by the observation that the exchange between organization and customers is at its most efficient when the incentives between the two parties are aligned—that is, when the organization benefits on the same dimension that defines value for customers. Any revenue model that departs from this ideal generates some waste, but this of course may be reasonable if the cost of further efficiency gains outweighs the benefit.

Accordingly, the best place to start for an organization is by reviewing the existing revenue model. Under the current regime, what are the biggest sources of waste in the exchange with customers—access, consumption, or performance? While answering this question, keep in mind that these three sources of waste are interrelated. Indeed, earlier we referred to them as natural checkpoints toward the solutions or outcomes that customers desire. Specifically, while customers clearly cannot derive value from the offerings they find in the market unless these perform as expected, performance is in itself contingent on consumption (customers cannot perceive performance in something they don’t even use), and consumption is in turn contingent on access (customers cannot consume or experience something they don’t even have).

The sequential nature of this relationship is important because it should motivate the organization to aim high. For instance, the shift to access models is a popular course of action today, and it is conceivable that the first move away from ownership eliminates the bulk of the inefficiency in the relationship between organization and customers. Adobe’s bet on Creative Cloud is a good example. But the so-called membership economy comprises only the first stage in the Ends Game, and taking on the responsibility for a higher-order form of waste such as consumption or even performance implies also taking on the responsibility for the waste that may come before it. There is a clear incentive for the organization to continue evolving.

Without much delay, however, the organization also needs to ask itself what business would look like if it dealt with customers on the basis of outcomes. Imagining this scenario requires creativity and the proper perspective. What is the right benchmark when a firm judges a future course of action? Although this is often the case in practice, the point of comparison should not be the status quo—as expressed by current performance in terms of the key financial and commercial indicators. This confers a false sense of security. Rather, the organization should draw a comparison between multiple futures, contrasting the likely consequence of a change in revenue model with the likely consequence of inaction (that is, the decision to maintain the existing revenue model). Moreover, the proper time horizon for this comparison is not the short term. As Adobe demonstrated, a change in revenue model can have negative immediate repercussions as the customer base “adjusts” to the new conditions. In fact, it helps to view any immediate dip on sensitive metrics such as number of customers, revenue, or profitability as an investment in a more sustainable future.

Any company that prides itself on being close to customers and their needs and wants will need to revisit its revenue model at some point if it wants to take this strategy full circle. This happens only when the company takes a step back from its daily routine, pushes back the pressures that come from internal processes, and starts questioning the gap between what it promises customers and what they actually pay for. What type of exchange do we want to be held accountable for moving forward? Similarly, what type of exchange will our customers hold us accountable for in the future?

Notes

1. A. Diallo, “Adobe’s Subscription-Only CC Release Carries Obvious Upside But Big Risk,” Forbes, June 17, 2013, https://www.forbes.com/sites/amadoudiallo/2013/06/17/adobe-cc-subscription-release-big-upside-and-risk/#122d226a19c6; Adobe 10-K report for the fiscal year ended November 30, 2012.

2. “Adobe’s Shift to the Cloud: Is This the Start of a Trend?,” Knowledge@Wharton, May 8, 2013, http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/adobes-shift-to-the-cloud-is-this-the-start-of-a-trend/.

3. D. Wadhwani, as quoted in S. Shankland, “Dislike Adobe’s Creative Cloud Subscriptions? Tough Beans,” cnet, May 28, 2013, https://www.cnet.com/news/dislike-adobes-creative-cloud-subscriptions-tough-beans/.

4. Adobe 10-K report for the fiscal year ended November 30, 2012.

5. Some dispute whether Gillette invented the razor and blades business model or defaulted to it. For an interesting perspective, see https://hbr.org/2010/09/gillettes-strange-history-with.

6. R. Trenholm, “Your Printer Orders Ink for You with New HP Instant Ink Service,” cnet, May 28, 2014, https://www.cnet.com/news/hp-instant-ink/.

7. T. Poletti, “How HP Is Trying to Resuscitate a Declining Business,” MarketWatch, July 3, 2017, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/how-hp-is-trying-to-resuscitate-a-dying-business-2017-06-30.

8. T. Hoffman, “How to Save Money with HP Instant Ink and Other Low-Cost Printer Ink Program,” PCMag, December 12, 2017, https://www.pcmag.com/article/357838/how-to-save-money-with-hp-instant-ink-and-other-low-cost-pri.

9. HP Inc. (HPQ), Q1 2019 Earnings Conference Call Transcript, The Motley Fool, February 27, 2019, https://www.fool.com/earnings/call-transcripts/2019/02/27/hp-inc-hpq-q1-2019-earnings-conference-call-transc.aspx.

10. “Newton’s Laws of Motion,” National Aeronautics and Space Administration, https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/newton.html, accessed April 13, 2020.

11. J. Bezos, as quoted in J. Del Rey, “This Is the Jeff Bezos Playbook for Preventing Amazon’s Demise,” Vox, April 12, 2017, https://www.vox.com/2017/4/12/15274220/jeff-bezos-amazon-shareholders-letter-day-2-disagree-and-commit.