Introduction: From Promises to Proof

Would you rather pay for health care or better health? Would you rather pay for school or education? Groceries or nutrition? A car or transportation? A theater act or entertainment?

Paying by the pill, semester, food item, vehicle, show, and so on is a poor reflection of the value that individual and business customers actually derive from their purchases. Nonetheless, the idea that a company could be compensated for the quality of the outcomes it delivers, rather than the products and services it brings to market, would have been dismissed until recently as utopian academic theory. Reality called for a compromise, one that most organizations have practiced pragmatically for decades: make a living by selling the “means” to customers, and promise that the “ends” they desire will follow.

Recent technological advances are rewriting the rules of commerce by calling this compromise into question. Mobile communication, cloud computing, the Internet of Things, advanced analytics, and microtransactions are making the exchanges between organizations and customers more transparent. By now, most companies have the ability to record consumption events. In some instances, companies can also observe the value customers derive from their purchases rather than infer it at some aggregate level. These developments have empowered customers who struggle to understand what their money buys them to demand accountability rather than accept simple promises. Customers are no longer the passive price takers of yesteryears. Accountability both defines and widens the gap between organizations that can and want to compete on the outcomes that matter to customers, and organizations that are content with perpetuating the status quo.

Some of the firms that earn revenue by selling “means” dismiss this challenge, turning a blind eye and hoping that it is another passing trend. Others scheme to make life even more complicated for customers, making their prices, assortments, and other commercial decisions more ambiguous and thus less comparable across competitors. However, it is hard to justify these approaches as winning plays in the long run. The alternative, of course, is to embrace change and get to work.

The way we see it, accountability is no longer a fashionable marketing slogan. It is a strategic imperative. Progressive firms are collecting and capitalizing on what we call “impact data” in order to better understand when and how customers use their solutions, and how these solutions actually perform. In many sectors, the technology now exists to turn products into seamless services, to record usage occasions, and, significantly, to quantify performance at scale and with precision. These progressive firms are evolving to make commerce far more efficient than it ever was, and in so doing unlocking market potential and positioning themselves to capture the lion’s share of the tangible value that materializes.

The Ends Game prepares firms to win in today’s increasingly transparent markets. Using in-depth case studies from sectors as diverse and consequential as health care, education, media, automotive, aviation, and mining, we map the relentless evolution of sectors to the point where the money of customers flows to proof rather than promises. The innovative revenue models that we describe here are not a phenomenon at the fringes of the economy. They are redefining entire markets and altering public discourse. The Ends Game helps organizations to understand how these shifts affect their futures and how to exploit the resulting opportunities to the fullest. It is a book about the very nature of commerce and the disruption of markets.

Exposing Inefficiency

Commerce starts with customers who seek out organizations that can solve their needs and wants. Individuals may be after a particular sensation, a tangible benefit, or some combination of the two. The same applies to business customers, who typically want to improve their own financial performance, but may also be swayed by less objective considerations.

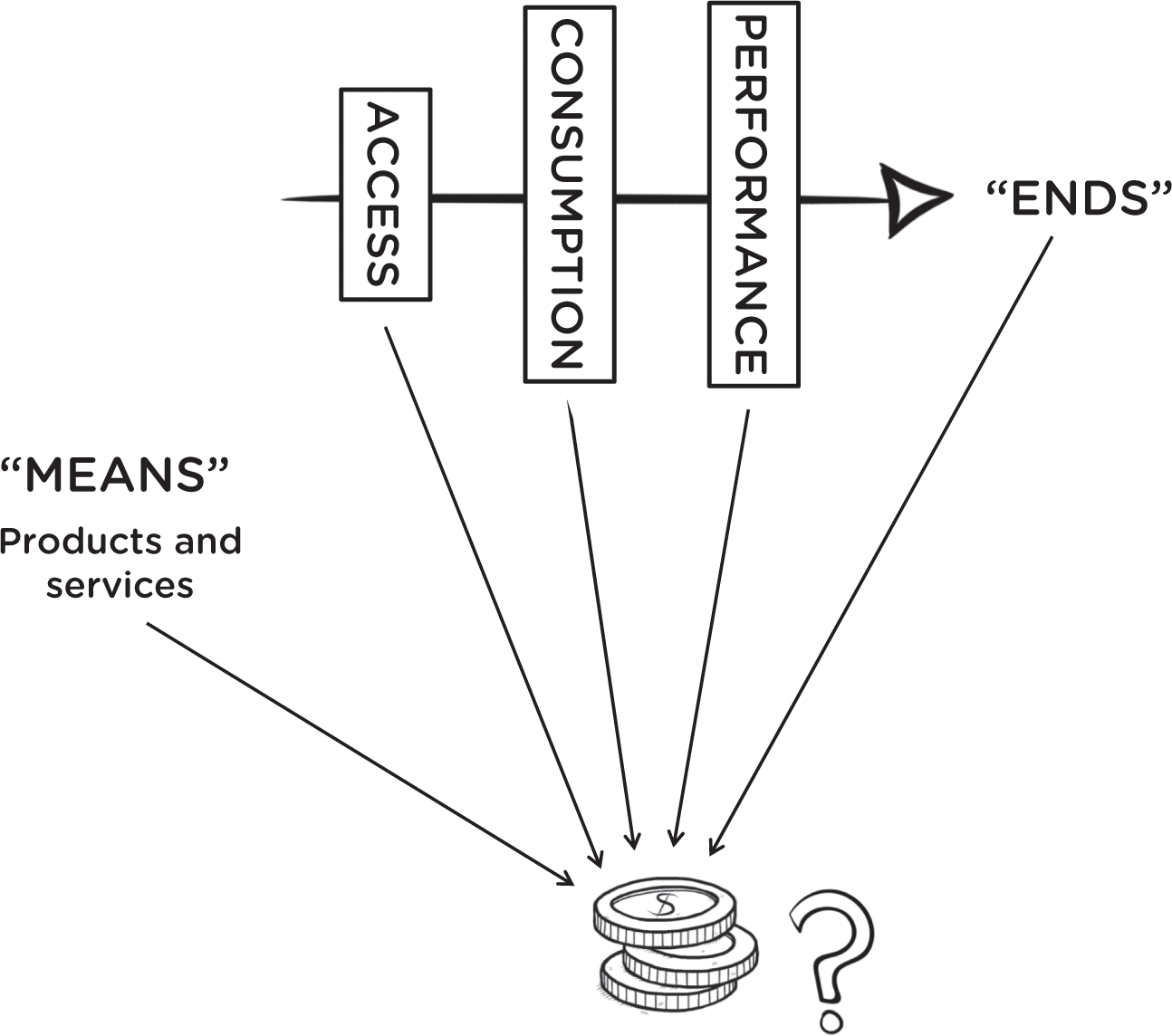

To appreciate whether an exchange between an organization and its customers is efficient, we first have to understand the necessary conditions for customers to derive value. Figure I.1 below represents this. There are three critical checkpoints, if you will. First, customers have to access the solutions that firms bring to market. Clearly, customers cannot derive value if they are blocked, financially or physically, from reaching the products and services that are intended to address their needs and wants. Second, conditional on access, customers have to consume these products and services. Again, customers cannot derive value unless they actually experience or make use of the solution offered by a firm. Third, conditional on access and consumption, the product or service has to perform as customers expect—that is, it has to solve the need or want satisfactorily.

Customers seek solutions to their needs and wants. Access, consumption, and performance are natural checkpoints toward these solutions.

We claim that an exchange is inefficient when customers experience friction at any one or more of these checkpoints. Traditionally, organizations earn revenue by selling what they make, but this can hinder access, distort consumption, and offers no guarantee of performance. Indeed, a revenue model focused on transferring ownership to customers may appear safe and prudent to the organization, yet it shrinks the opportunity in the market by leaving customers to their own devices. Some customers are priced out of the market or choose to forgo a purchase because it is inconvenient. They may also worry that their tastes will change, and therefore perceive ownership as an unnecessary burden and again decide to stay away. Other customers resolve to pay less to account for the possibility that they will not make sufficient use of the product or service, that it will not perform as advertised, or both.

Fortunately, as shown in figure I.2, firms have options. By lowering barriers to entry and shifting the risk burden away from customers, new revenue models help firms hold themselves to account for access, consumption, and ultimately performance. Specifically, revenue models such as subscriptions, memberships, and “anything-as-a-service” anchor payment to time rather than a physical good or service, opening up the market to profitable customers who may otherwise be out of reach. These “pay-per-time” arrangements address different types of access problems. First, customers may not have the ability to visit a point of sale when the need arises, or they lack the foresight to make an additional purchase before running out of stock. Second, customers may not have the capital to own the product or service outright. Finally, there are a host of categories including music, television, fashion, and books where individual items are inexpensive but variety is important, making the overall purchase a significant one.

An organization can earn revenue on what it makes (the “means”), on any one of checkpoints, or on the actual solutions sought by customers (the “ends” themselves).

Next, revenue models based on unbundling, metering, or sharing all link payment to use, not only in order to expand access, but also to track consumption. In the first case, the firm digitalizes its offering and delivers it in a more granular form. Metering means that the firm supplies the product whole, but charges only for its use. A model built on sharing is one where sellers either manage or join a platform to distribute a product or service across many interested users. Such “collaborative consumption” is growing at an impressive rate.

Finally, revenue models that focus on actual outcomes expand access, mirror consumption, and ensure performance. “Pay-by-outcome” agreements have traditionally found success in contexts where performance is objective, quantifiable, and verifiable. However, in recent years similar agreements have taken hold in consumer markets for health, education, insurance, and even live entertainment.

The Ends Game offers guidelines to business leaders who are willing to meet the challenge of accountability. We provide a framework to understand how innovative arrangements from subscriptions and collaborative consumption to outcome-based agreements align with customers’ pursuit of value. We define and clarify the steps to take within and outside the firm, as well as the benefits that accrue from acting.

Clearly, the more an organization aligns the way it earns revenue with the way customers derive value—that is, the more responsibility for the three checkpoints of access, consumption, and performance it takes on—the “leaner” (as in more efficient, less wasteful) the exchange between the two becomes. This is represented in figure I.3, where market potential converts into actual market value as the organization brings its revenue model increasingly into line with the “ends” sought by customers.

As the organization moves to align its revenue model with the “ends” sought by customers, efficiency gains convert market potential into actual market value.

The leanest exchange, then, is one where a company’s fortunes are contingent on delivering value itself. Several firms that are working closely with customers—such as health care providers, universities, leading industrial manufacturers, and many startups—already stake their positioning and future on this metric. They hold themselves accountable for it. Yet an important lesson in The Ends Game is that, while pay-by-outcome may be the final destination, it is not necessarily the next destination. Context certainly matters. First, there are obstacles within the firm: what is the definition of “outcome” that we can agree on? How does our offering stack up against those of competitors on this measure? How can we communicate our superiority in a manner that is unambiguous? What is our plan for making the transition from the current revenue model? Second, customers play an integral role: to what extent are they willing to share information about consumption? How motivated are they to play their part in the achievement of a successful outcome? Third, technology will always mark the pace of change.

Accordingly, we do not claim that a shift to, say, outcome-based agreements is urgent and necessary. This overstates the case at the moment. What we do claim, however, is that revenue models anchored on the ownership of a product or service are patently inferior. When selling ownership is the standard in a market, firms with weaker products can siphon off clients with a good story or a cut-rate price. As some firms adopt better metrics, these inferior firms no longer have a place to hide. In the world of lean exchanges between organizations and customers, money flows to proof, not promises. Today, making the transition to a revenue model anchored on time or use is certainly within reach of most businesses as they study and prepare for bolder moves.

What to Expect from The Ends Game

Part I provides context for the transition to lean commerce. Chapter 1 traces the evolution of customer focus as a management philosophy and explains why, from our perspective, this evolution is incomplete. From production to distribution to communication, companies have learned to put themselves in the shoes of their customers and reimagine each process with their interests at heart. But customer focus has not reached its logical conclusion. The missing and final part is the process by which organizations convert value to the customer into value for the business.

In chapter 2, we describe how recent technological advancements enable firms to take the logic of customer focus full circle by collecting, analyzing, and interpreting information on when and how customers consume products and services, and how well these offerings actually perform—what we call “impact data.” This sets the stage for companies to understand how they can target the various sources of waste—access, consumption, and performance—by choosing a revenue model that is better aligned with how customers derive value from their purchases. Chapter 3 highlights how different revenue models decrease or exacerbate misalignments between how firms create value for customers and how they create value for themselves. Misalignments result in the three interrelated sources of waste that burden so many sectors of our economy and cry out for elimination.

Part II offers a rich set of examples of how companies are already playing the Ends Game, eliminating inefficiencies and making commerce far leaner. Chapter 4 introduces firms that changed their revenue models—or implemented new ones from scratch—to make their products accessible to more customers while minimizing their financial exposure. Chapter 5 shows how firms are unbundling their offerings to make consumption more flexible, tackling access and consumption waste by metering consumption, or activating dormant assets by linking them to the sharing economy. Chapter 6 provides examples of organizations that earn their revenue based on the outcomes they deliver. Firms using these arrangements demonstrate that playing the Ends Game at its highest level changes both the firms’ and customers’ understanding of what an exchange between them can achieve.

Part III is about action. It focuses on the challenges that firms will face. Chapter 7 offers guidance on how to answer what sounds like a deceptively simple question: What are we asking customers to pay for? It provides criteria for defining an outcome that can form the basis for a more efficient revenue model. Chapter 8 explores the reasons why the firms with the greatest chances of success in pursuit of lean commerce are often the most reluctant to play the Ends Game. Several self-imposed obstacles stand in their way.

Chapter 9 explores the issues around impact data, particularly with respect to collection, protection, and use in ways that help customers without endangering their privacy. A company can conceptualize, measure, and charge for an outcome only to the extent that it has access to sufficient, relevant information. Chapter 10 looks at the issues involved in managing customers such that they contribute positively to the quality of an outcome. The elimination of access, consumption, and performance waste often depends on customer motivation and participation, two things that a firm cannot take for granted. It is important to implement mechanisms that ensure customers make positive contributions.

Part III concludes with chapter 11, which examines more of the specific obstacles an established organization faces internally as it starts to play the Ends Game. These include the cultural changes necessary to help the organization overcome its inertia and shift away from tradition. Often it is a newcomer that succeeds in reducing waste by introducing a revenue model conceived to improve access to the market, mirror consumption, or perhaps even guarantee performance. These success stories leave incumbents with a difficult, if not existential challenge that requires an urgent response. If they do not abandon their antiquated practices, they may be forced to abandon their journey as a business entirely.

Prior to the technological breakthroughs of the twenty-first century, lean commerce was not possible on a large scale. There was no practical way to identify and eliminate the billions of dollars of waste that frustrates customers, stifles opportunities, and holds firms back from taking full advantage of their ability to deliver value to customers. Lean commerce is now not only possible, but also a mandate for organizations. The concepts, examples, and suggestions in The Ends Game will empower organizations and help them tackle the rocky road ahead.