One of the fears is that expanded genome profiling will lead to reification of the belief of the biological basis of race. In particular, the use of expanded genome profiling may lend credence to the opinion that criminal activity is associated with a particular genetic make-up prevalent in certain males and/or individuals.

It is well documented that the American criminal justice system is heavily racialized. By this we mean that racial disparities have been identified in all parts of the system, from arrest, trial, and access to legal services to conviction, sentencing, parole, execution, and exoneration. For example, in regard to prison demographics, New York University sociologist Troy Duster reported that “African Americans are currently incarcerated at a rate approximately seven times greater than that of Americans of European descent.”2 Duster’s data show that the disparity in black versus white incarceration has grown significantly in recent years: in the 1930s blacks were incarcerated at a rate that was less than three times that of whites. Explanations that have been provided for this change range from musings on the decline of the moral character of African American males to a society rife with racial prejudice and economic injustice against people of color. Although vigorous controversy remains whether differential criminal involvement or differential criminal justice selection and processing are to blame for racial disparities in the system, most criminologists agree that racial discrimination cannot be dismissed.3 Indeed, a large body of empirical data supports the notion that racial bias plays a key role in driving these disparities.

Will the technology of DNA analysis and DNA data banks exacerbate or improve the racialized criminal justice system? One response suggests that DNA science trumps racial prejudice. DNA testing provides us with a means to identify suspects that—even if not impervious to error—is more objective than, say, eyewitness identification. The claimed neutrality of forensic DNA technology implies that its introduction would shed light on racial disparities and pave the way toward a more just and equitable criminal justice system. Cases where DNA exclusions have exonerated minorities falsely convicted as a result of racial bias support this view. Another response, however, suggests that race trumps science. In this view science and technology must be understood within their broader social context. In a racially polarized society rife with racial disparities, it is a reasonable expectation that DNA testing will be used to reinforce the bias in criminal justice.

In reality the impacts of DNA technology on racial injustices are most likely a complex combination of each of these responses. This chapter examines the ways in which forensic DNA technology offsets, exacerbates, masks, or highlights racial disparities in criminal justice. Answers to the following set of questions will provide some clarity to these issues.

- What is the current racial composition of the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), and how will it be affected by broadening the criteria of inclusion to include arrestees?

- Will disproportionately higher minority representation in CODIS result in racial stigmatization or impose relatively greater civil liberties transgressions on minority communities?

- Will uses, other than identification, be made of the forensic DNA databases, and if so, what implications will those uses have for minority populations?

We begin with a brief overview of the way in which racial disparities operate in the criminal justice system.

Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice System

To understand the nature and persistence of racial disparities in the criminal justice system, one has to begin with the laws that classify and define crimes. For example, for many years the federal system punished those convicted of crack cocaine offenses much more severely than those convicted of powder cocaine offenses, even though studies showed that the difference in the danger of the drugs is minor.4 Crack is far more likely to be sold and used by blacks, while powder cocaine is more likely to be sold and used by whites.5 From 1986 to 1990, the height of the Reagan administration’s “War on Drugs,” the average prison sentence for blacks compared with that for whites for drug offenses rose from 11 to 49 percent.6 But the problem goes well beyond sentencing guidelines. The Justice Policy Institute, citing national survey statistics, reported that in 2002, 24 percent of crack cocaine users were African American and 72 percent were white or Hispanic, but more than 80 percent of defendants sentenced for crack cocaine offenses were African American.7

Part of the explanation of how these gross disparities arise can be found at the place where individuals tend to first come into contact with the criminal justice system—that of detention and arrest. Study after study has demonstrated that people of color are disproportionately arrested for drug offenses, automobile theft, and driving under the influence.

Data reported by sociologist Harry Levine on marijuana-possession arrests shed light on this phenomenon. From 1997 to 2006, on average, 100 people were arrested every day in New York City for marijuana possession. Each year, on average, New York City police arrested approximately 20,000 blacks for marijuana possession, compared with 5,000 whites. Adjusting for population, arrest rates for blacks have been approximately eight times as high as those for whites. This rate would be acceptable if it were true that blacks were eight times as likely as whites to use marijuana. But, in fact, U.S. national survey data have consistently shown that more whites use more marijuana than blacks.8 In other words, “Since Whites use marijuana more than Blacks or Hispanics, and since there are more Whites than Blacks or Hispanics in New York City, on any given day significantly more Whites possess and use marijuana than either of the other two groups. But every day the New York Police Department arrests far more Blacks than Whites, and far more Hispanics than Whites, just for possessing marijuana.”9 This pattern is not true only for New York City, nor does it hold only for marijuana. A study of arrestees in Maryland found that while 28 percent of the population is comprised of African Americans, 68 percent of the arrests for drug abuse are African Americans.10

Some of the disparity in arrest rates might be explained by disparate policing practices—for example, where police focus their efforts on low-income or ethnic-minority neighborhoods.11 Data from the Justice Mapping Center show that more than 50 percent of the men sent to prison from New York are from districts that represent only 17 percent of the adult male residents.12 Pilar Ossorio and Troy Duster observed that the few DNA dragnets carried out in the United States have disproportionately targeted blacks. For example, San Diego police, in search of a serial killer in the early 1990s, identified and genetically profiled 750 African American men on the basis of eyewitness reports that the perpetrator was a black male.13

Some of the disparity in arrest rates might also be explained through racial profiling by individual officers. Michael Risher notes:

Studies have shown that some mixture of unconscious racism, conscious racism, and the middle-ground use of criminal profiles leads law enforcement to focus its attention and authority on people of color. This can include everything from police officers disproportionately selecting people of color to approach, question and ask consent to search, to discriminatory enforcement of traffic laws, and detaining and arresting people of color without sufficient individualized suspicion.14

Police officers have significant discretion in making arrests, particularly when it comes to “victimless” crimes, such as drug use or “public order” crimes, and rarely face any consequences in cases where a person is improperly arrested without probable cause. In a study by Aleksandar Tomic and Jahn Hakes, the authors found that when police had broad discretion in making on-scene arrests, blacks were treated more aggressively than whites:

Our model of racial bias in arrests predicts, and our empirical results suggest, that the policing of blacks has been disproportionately aggressive for crimes associated with high levels of police discretion to make on-scene arrests. . . . The resulting increases in the proportion of Blacks in the criminal justice system can affect the perception of officers in subsequent cases, perpetuating the imbalances even in the absence of racial differences in underlying criminality.15

A similar pattern of racial bias is seen in the makeup of the prison population. According to a 2007 report issued by the Justice Policy Institute, despite similar patterns of drug use, African Americans are far more likely to be incarcerated for drug offenses than whites. As of 2003, twice as many African Americans as whites were incarcerated for drug offenses in state prisons in the United States. African Americans made up 13 percent of the total U.S. population but accounted for 53 percent of sentenced drug offenders in state prisons in 2003. In 2002 African Americans were admitted to prison for drug offenses at 10 times the rate of whites in 198 large-population counties in the United States.16

According to data from the Innocence Project, an organization dedicated to the use of DNA to exonerate falsely convicted persons, racism is also a significant factor in wrongful convictions. African Americans make up 29 percent of people in prison for rape and 64 percent of those who were found to have been wrongfully convicted of rape. This suggests that there are disproportionately more false convictions for rape of blacks than of whites. Also, most sexual assaults nationwide are committed by men of the same race as the female victim. Only 12 percent of sexual assaults are cross-racial. This fact, in conjunction with data that show that two-thirds of African American men exonerated by DNA evidence were wrongfully convicted of raping white women,17 reveals the subtext of racial bias in false conviction. The vestigial fears and prejudice held by whites of black-on-white rapes, whose roots go back to slavery, become expressed in our current society by trumped-up accusations, mistaken identification, and false convictions.

Racial Composition of CODIS

Because of the disproportionately high rates of arrest and incarceration of people of color,18 it can be inferred that the U.S. Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), which, according to the FBI, is not coded by race, is also disproportionately composed of racial minorities. If CODIS, by and large, contains the profiles of past and present incarcerated felons, and minorities are disproportionately represented in prison, then it follows that they will be disproportionately represented in CODIS. Moreover, if Tomic and Hakes’s results are corroborated, the mere appearance of innocent blacks in DNA data banks, even if they are never charged with a crime, will impose a penumbra of bias by law-enforcement officials toward those individuals. If DNA databases are superimposed on traditional racial profiling and other forms of bias toward African Americans, the combination could lead to greater degrees of racial disparity in criminal justice. Troy Duster observes:

Indeed, racial disparities penetrate the whole system and are suffused throughout it, all the way up to and through racial disparities in seeking the death penalty for the same crime. If the DNA database is primarily composed of those who have been touched by the criminal justice system, and that system has provided practices that routinely select more from one group, there will be an obvious skew or bias toward this group.19

In chapter 2 we showed that there has been a rapid expansion of DNA data banks in certain states where the criteria have evolved from violent offenders and felons to arrestees who have not been charged with or convicted of crimes. Let us assume that this policy continues beyond the dozen or so states that have lowered the threshold of inclusion in their forensic DNA data banks, and that “being arrested” becomes the standard within the criminal justice system for requiring a biological sample and a DNA profile. How will that affect the racial composition of CODIS?

To contextualize this question, we first examine the racial composition of those who are serving sentences in federal and state prisons. According to a report published by the Pew Charitable Trusts in 2008, 1 in every 15 black males aged 18 or over, compared with 1 in 106 white males of the same age group, is in prison or jail. The highest rate of incarceration is among young black men. One in 9 black men aged 20 to 34 is behind bars.20 Although African Americans make up 12.8 percent of the U.S. population, they constitute between 41 and 49 percent of the prison population.21 Sixty-two percent of all prisoners incarcerated in the United States are either African American or Latino, but those groups constitute only one-quarter of the nation’s entire population.

There is no published information on the racial and/or ethnic composition of individuals who have DNA profiles contained in CODIS. The FBI does publish annual crime reports broken down into racial categories, but states may upload only names and DNA profiles to CODIS without personal information such as a racial or ethnic identifier. Each state retains the personal information associated with the profiles placed in the national DNA forensic database, but as far as we can tell, that information is not aggregated.

It is reasonable to assume that the racial composition of CODIS mirrors the racial composition of the prison population. The racial composition of CODIS can also be estimated indirectly. Henry Greely and colleagues use a crude measure of felony convictions to estimate the number of African Americans in CODIS, since the vast majority of states currently retain and upload to CODIS DNA from all felons:

African-Americans constitute about thirteen percent of the U.S. population, or about thirty-eight million people. In an average year, over forty percent of people convicted of felonies in the United States are African-American. . . . We assume, based on the felony conviction statistics, that African-Americans make up at least forty percent of the CODIS Offender Index.22

If we assume that the racial composition of CODIS mirrors the current prison population, we arrive at a similar estimate, with African Americans constituting 41 to 49 percent of CODIS.

According to the FBI, the National DNA Index System (NDIS) held 8,201,707 “offender” DNA profiles as of April 2010.23 On the presumption of 40 percent African American entries, they would constitute 3,280,683 entries in CODIS. This means that approximately 8.6 percent of the entire African American population is currently in the database, compared with only 2 percent of the white population.

Suppose that we asked this question: how would the composition of the database change if all states collected DNA profiles of arrestees? If blacks in American society continue to be stopped, searched, arrested, and charged at a rate in excess of nonminorities, and if collecting DNA samples from arrestees becomes the norm, then it would seem that the racial disparity of blacks in CODIS would continue to grow. D. H. Kaye and Michael Smith make the case for strong racial skewing of U.S. DNA data banks as the system currently exists:

There can be no doubt that any database of DNA profiles will be dramatically skewed by race if the sampling and typing of DNA becomes a routine consequence of criminal conviction. Without seismic changes in Americans’ behavior or in the criminal justice system, nearly 30% of black males, but less than 5% of white males will be imprisoned on a felony conviction at some point in their lives. . . . A black American is five times more likely to be in jail than is a white.24

The authors estimate that the profiles of about 90 percent of urban black males would be found in DNA data banks if all states required DNA samples from arrestees. At the same time, they contend that racial disparities would be diminished by expanding the databases to include arrestees because many more whites would be brought into the databases: “Racial skewing of the DNA databases will be reduced somewhat if the legal authority to sample and type offenders’ DNA continues to expand and come to include the multitudes convicted of lesser, but more numerous, felonies and misdemeanors.”25

We can use current FBI arrestee statistics to evaluate the claims about racial disparities in expanding CODIS. According to the 2007 FBI data on national arrests, there were 9,014,180 individuals 18 years or older arrested in the United States; 70.2 percent (6,327,954) were white and 27.7 percent (2,496,928) were black.26 If we use these figures, adding all the arrestees to CODIS would tend to bring down its racial composition from an estimated 40 percent blacks to slightly less because we are diluting what is believed to be a higher relative percentage of blacks with a lower relative percentage. Because DNA profiles might be taken only of arrestees who commit violent crimes, let us consider those figures. The FBI classifies violent crimes as murder or nonnegligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault. In 2007, 376,745 individuals were arrested for violent crimes as defined by these four categories, of whom 63 percent were white and 36 percent were black. If we added these arrestee profiles to CODIS, the percentage of blacks would be reduced slightly from 40 percent. In other words, adding arrestees who had committed violent crimes to CODIS would increase the racial composition of blacks only if their current composition in CODIS were less than 36 percent.

Of the four categories of violent crimes, only two (murder/manslaughter and robbery) have a higher percentage of black arrestees than whites (50 versus 48 and 53 versus 46, respectively). The racial disparity of blacks in CODIS would increase only slightly if arrestees charged with murder/manslaughter and robbery felonies (and then released) were the only violent perpetrators added to the database because of the relatively small numbers of these crimes.

However, we should not be concerned only with the relative proportion of whites and blacks in the database; we should also consider the proportion of the African American population that is in the database compared with the proportion of the white population. As stated earlier, currently 8.5 percent of African Americans are in the database. If we assume that these are predominantly males (approximately 80 percent of individuals arrested for violent crimes are male, for example), then we are approaching a situation where as many as 14 percent of African American males are in the database, even before we have started to upload arrestees to the system. Of the approximately 2.5 million arrests of blacks that occur each year,27 a large proportion of those arrests will not result in conviction. The U.S. Department of Justice reports that 47 percent of the more than 140,000 individuals arrested for a federal felony offense in 2004 were not convicted.28 Similarly, more than 30 percent of the hundreds of thousands of individuals arrested on suspicion of a felony each year in California are never convicted of a crime.29 Conviction rates for lower-level crimes are even lower; a study in California revealed that 64 percent of drug arrests of whites and 92 percent of those of blacks were not sustainable.30 Assuming a 50 percent conviction rate for all arrests, this means that of the 2.5 million blacks arrested each year, half will be added to the database who would not have been added under a system that requires conviction for inclusion in CODIS. In just the first year the percentage of the African American population represented in CODIS, from the addition only of unconvicted blacks, would rise to 11.8 percent of the African American population, or close to 19 percent of the male African American population. In comparison, still only 3 percent of whites would be in the database (or as many as 5 percent of white males, under the same assumptions). Predicting how this would play out over time is difficult because one would have to account for repeat arrests or, alternatively, have an estimate for one’s lifetime risk of being arrested. Such estimates have been reported as 80 to 90 percent for urban black men.31 If we layer on top of this the fact that blacks are inappropriately arrested at higher rates than whites, then blacks who are innocent under the law will also be disproportionately represented in the database. This may be especially true where data banks are expanded to arrests for nonviolent (“victimless”) crimes, where police have significant discretion in making arrests. As stated earlier, a 1993 California study revealed that while 64 percent of drug arrests of whites were not sustainable, a full 92 percent of the black men arrested on drug charges were subsequently released for lack of evidence or inadmissible evidence. There are nearly 2 million drug-abuse arrests annually.32 Furthermore, if the use of controlled substances as a percentage of population is equal to or greater in the white community than in the black community while the arrests are disproportionately higher for the latter, then not only are blacks treated unequally by law-enforcement officials but their DNA makes them and their family objects of continued genetic surveillance.

Because blacks are represented in CODIS and in prisons at a much higher percentage than their relative composition in the general population and at a higher percentage relative to nonminorities, if we expand the use of forensic DNA technology to the existing disparity, it will produce downstream effects that will further exacerbate racial prejudice. This is illustrated by the use of familial searching, as in the case when a close, but not exact, match is made between a crime-scene profile and an individual who has a DNA profile in CODIS. When arrestees who have not been convicted of a crime are added, their families are also brought under the surveillance lens of criminal justice. This conclusion was reached by Greely and colleagues:

Assume that, either using the current CODIS markers or an expansion to roughly twice as many markers, partial matches of crime scene DNA samples to the CODIS Offender Index could generate useful leads from an offender’s first degree relatives—parents, siblings and children. . . . Using some additional sampling assumptions, the percentage of African-Americans who might be identified as suspects through this method would be roughly four to five times as high as the corresponding percentage of U.S. Caucasians. . . . More than four times as much of the African-American population as the U.S. Caucasian population would be “under surveillance” as a result of family forensic DNA and the vast majority of those people would be relatives of offenders, not offenders themselves. . . . African-Americans are disproportionately harmed by crimes committed by other African-Americans.33

In the United Kingdom, England and Wales have the largest per capita forensic DNA data bank in the world. At the end of March 2009 there were 4.8 million DNA profiles in the database, representing about 7 percent of the population in England and Wales, compared with the national DNA data bank in the United States, which contains 2.6 percent of its population. Recent data reveal that more than one-third of black men in the United Kingdom have DNA profiles in the national DNA data bank, which includes three out of four black males between the ages of 15 and 34.34 If the United States were to reach that percentage, CODIS would have 13 million DNA profiles of African American males.

Rounding Up the Usual Suspects

Human DNA is shed continuously in all the environments in which people interact. Our saliva is left on paper cups we discard in a coffee shop or empty soda cans we leave behind at a park. We leave hair fragments in bathrooms of restaurants or on shirts we bring to the cleaners. Swabbing for DNA at a crime scene has become almost as common as screening for fingerprints. Newer techniques allow investigators to retrieve trace DNA samples from touched objects. Obtaining profiles of DNA left at a crime scene may sometimes be useful to investigators, but it also may be irrelevant without other forms of evidence. With massive DNA data banks, every DNA sample found at a crime scene that matches someone in the data bank will become grounds for investigation—for no other reason than that the evidence shows that either the person or his or her discarded objects were once at the place of interest.

Let us suppose that there is a robbery and shooting at a Starbucks coffee shop. An employee at the coffee shop believes that the hooded robber had a cup of coffee before the robbery. Police obtain all the discarded cups for DNA samples on the premises. Once the profiling of the DNA is completed, investigators submit the profiles to the national and state DNA data banks, which by 10 years from today may have more profiles of innocent people, including juveniles, than of convicted felons.

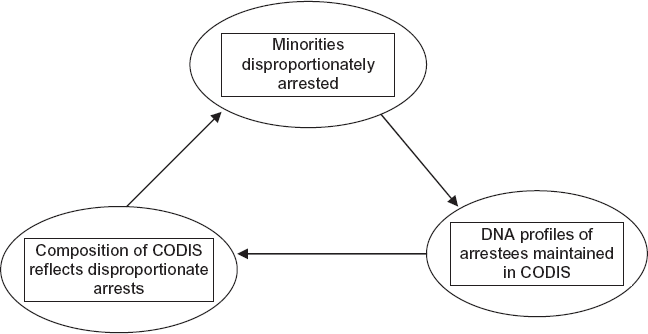

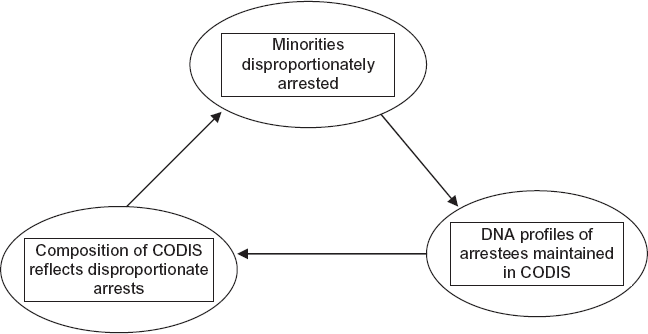

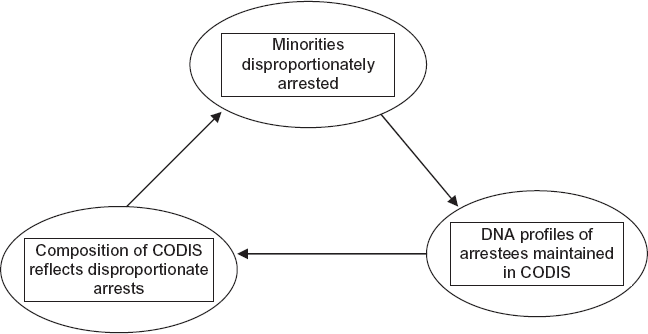

If African Americans are disproportionately overrepresented in CODIS, not because of prior convictions, but because blacks are stopped and arrested more frequently than whites, then they are more likely to become suspects in any crime that involves a DNA sweep (see figure 15.1). An old adage claims that crime-scene investigators will go where the evidence takes them. In this technological era we can say with some degree of confidence that crime-scene investigators will go where the DNA takes them. The greater the disparity in the percentage of African American DNA profiles in CODIS, the greater will be the disparity in suspicion of blacks, false arrests, and false convictions.

FIGURE 15.1. The cycle of racial disparity in DNA data banks. This flowchart depicts the increasing and compounding racialization of CODIS under a system of expanded criteria for collection and retention of DNA profiles in state and federal databases. Minorities, more likely to be arrested, are disproportionately represented on the database. Racial disparities in the criminal justice system are then further exacerbated, since, once in the database, these individuals are more likely to be arrested again in the future. Source: Authors.

In the hypothetical Starbucks shooting, perhaps there were a dozen cups in the trash with sufficient cells for DNA analysis. If only two profiles showed up in CODIS that matched the DNA profiles on the cups, those would be the people the police would investigate, interrogate, and follow around for the reason that one pursues the leads one has even though what the police have became potential evidence because the database used to match “abandoned” DNA to profiles in CODIS was weighted disproportionately toward minorities. Given the racial composition of the data bank it would be no surprise to learn that both of the profiles were from black males.

One can argue that if everyone’s DNA were in CODIS, at least all the cup users would have an equal chance of becoming a suspect, not just the ones whose DNA can be found in CODIS. Similarly, if all immigrants or illegal aliens were profiled for CODIS, members of those groups would become criminal suspects disproportionately to their ethnic representation in the population.

Another implication of racially imbalanced DNA data banks is stigmatization. It is reasonable to assume that police are likely to be biased toward individuals who have had a prior run-in with the law. To use the language of Bayesian statisticians, such information about the past raises one’s prior probability that the individual is guilty. In the future the technology for checking a DNA profile of an individual will assuredly become miniaturized and faster. The digitized profiles can be uploaded to a mainframe computer and accessed with portable devices by police while on patrol.35 If the profile shows up in the database, it may bias the officer’s prior expectation of guilt or innocence. At the very least, an individual may be subject to intensive questioning and treated as a suspect with very little other evidence. As long as the playing field of DNA data banking is not level, where minorities and people of color are overrepresented, for those whose profiles appear in the database, there is a strong probability of stigmatization and the prejudicial use of the information. We should remind ourselves that these consequences will fall on many innocent people, perhaps because they volunteered their DNA in a dragnet, they are part of a minority group that was disproportionately arrested, charged with, or convicted of crimes that they did not commit, or because they entered the country as undocumented immigrants.

Forensic Data Banks in Scientific and Medical Research

Many states have passed laws that give researchers access to DNA information in state data banks. For the time being, scientists cannot learn very much from having access to 13 loci, even if they also have the individual’s phenotypic information, that is, medical records. The loci used in DNA profiling were chosen specifically because they are not correlated with physical attributes of individuals. Nonetheless, at least one of these markers has proved to be closely related to the gene that codes for insulin, which itself relates to diabetes,36 and it is possible that other connections of this sort will occur in time. That said, in order for scientists to acquire extensive knowledge about individuals from the DNA data banks, they will need the entire genome (the biological sample) or at least a portion of it that contains the DNA (functional or coding DNA) that reveals a detectable physical trait. It would also help the research if the scientists had social and medical histories of the individuals.

What type of research is most likely to interest scientists? The prison population consists disproportionately of people of lower socioeconomic status, with poor education, often from broken homes or dysfunctional families, who have committed violent acts, such as child abuse or rape. Historically, researchers have shown an interest in the use of prison populations to study the genetics of aggression, intelligence, and pedophilia. Does someone in prison, who has by law been required to give a biological specimen to a police unit, have any right over potential research uses of his or her DNA profile and/or the original biological sample? Do prisoners retain the right of “informed consent,” a fundamental principle of the “common rule” (federal policy regarding human subjects protection), as subjects of research?37

Prisoners certainly cannot be forced to serve as human subjects for drug testing. For over 25 years it has been the policy of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) that no therapeutic experiments be conducted on prison populations or any populations of incarcerated individuals.38 The principle underlying this policy is that people who are in prison or detained cannot exercise their informed consent as free and autonomous human beings.

The issue of informed consent of prisoners for the use of DNA and/or medical information has not been resolved in U.S. policy. In February 2006 the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued its ethical guidelines on human experiments to test pesticides.39 That policy kept open the possibility that the agency would accept human toxicological data obtained by exposing prisoners to pesticides—in conflict not only with the ACLU’s policy but also with well-established international codes of ethics.40

Let us suppose that a group of researchers wishes to investigate the genetics of pedophilia. There is no reasonable means of acquiring a study population from pedophiles freely moving about society. Even though released sex offenders are known to society because they are required to register in most states, it is doubtful that this group of individuals would freely join a genetic study of pedophilia. If such individuals were willing to participate, researchers would need a DNA sample and a detailed social and medical history of the subject. Researchers would also be required to fulfill their ethical responsibility of informed consent under the “common rule.”

Pedophiles in prison are a captured population whose DNA profiles and biological samples are already on file. It would be far more convenient for researchers to use prisoners for this study than to seek out a study population from individuals living freely, although under public surveillance, in society. But an even easier way to study this population would be to bypass any direct contact with the individuals and instead to go directly to the stored biological samples.

“Criminal” Genes

There is a long tradition in sociology and anthropology and more recently in sociobiology of seeking to discover a biological root cause of criminal behavior or sociopathology in people’s blood, brain, or genes. Hereditarian views of behavior and personality saw a resurgence of interest in the post-Darwinian period up to the Second World War. For a time after the war greater emphasis was placed on environmental and social influences on behavior. However, in the late 1960s there was a resurgence of interest in the hereditarian approach to violence. At the same time, new tools were developed for studying human genetics.41 In a notable case prisoners were chosen to test a theory that an extra Y chromosome in males (XYY males) was a factor in explaining violent behavior.42 The study was criticized for its methodological flaws and was eventually terminated. More recently scientists have found a region of the chromosome where there are variants of a gene that regulates the production of the enzyme monoamine oxidase A (MAOA), which has been proposed as a possible mechanism for a genetic theory of violence (see the “Behavioral Genetics and Profiling” section in chapter 5). In this theory a variant of a gene either overexpresses or underexpresses a chemical that affects a region of the brain.43 More recently a study found that individuals with the gene that results in low MAOA activity were twice as likely to join a gang as those with the high-activity form.44

A persistent interest in the biological—and, more specifically, genetic—underpinnings of human behavior has made forensic DNA data banks a valuable resource for researchers. The data banks could allow those who seek to find genetic explanations for violent crime (not white-collar crime) a means to pursue this research that avoids the ethical and methodological flaws associated with focusing directly on prisoners. Elisa Pieri and Mairi Levitt discuss the return of behavioral genetics as an explanation for criminal activity and the role of DNA data banking in the United Kingdom to support such research:

Children as young as ten that are arrested can now be DNA swabbed and entered (for life) on the National DNA database, even if they are never charged and subsequently acquitted. This database, already used for research into ethnic profiling, may potentially provide the DNA data for future behavioural research into criminality, violence or aggressiveness.45

A report of the Select Committee on Home Affairs of the United Kingdom’s Parliament describes the growing racial disparity of the national DNA data bank (see box 15.1). The availability of a prescreened prisoner database for studying the genetics of human aggression would be highly desirable. However, there are serious methodological as well as ethical concerns with using a forensic data bank for these purposes. DNA samples from convicted felons are not a randomly selected sample. Troy Duster has warned that because African Americans are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system, any behavioral genetics research that relies on this subset of DNA samples will inevitably be skewed toward that population. Genetic markers may very well be found that are more prevalent among this population than another, but whether these markers explain the causes of criminal behavior is another matter. Nonetheless, we are likely to see what Duster refers to as “the inevitable search for genetic markers and seductive ease into genetic explanations of crime.”46

BOX 15.1 DNA of Blacks Is Stored Disproportionately in the British Data Bank

Currently, DNA samples can be taken by the police from anyone arrested and detained in police custody in connection with a recordable offence. This includes most offences other than traffic offences. A U.K. parliamentary committee examining the racial disparities in the criminal justice system reported:

Baroness Scotland confirmed that three-quarters of the young black male population will soon be on the DNA database. Although the Home Office has argued in the past that “persons who do not go on to commit an offence have no reason to fear the retention of this information,” we are concerned about the implications of the presence of so many black young men on the database. It appears that we are moving unwittingly towards a situation where the majority of the black population will have their data stored on the DNA database. A larger proportion of innocent young black people will be held on the database than for other ethnicities given the small number of arrests which lead to convictions and the high arrest rate of young black people relative to young people of other ethnicities. The implications of this development must be explored openly by the Government. It means that young black people who have committed no crime are far more likely to be on the database than young white people. It also means that young white criminals who have never been arrested are more likely to get away with crimes because they are not on the database. It is hard to see how either outcome can be justified on grounds of equity or of public confidence in the criminal justice system.

DNA Profiling for Racial and Ethnic Identification

Crime-scene DNA can now be analyzed by racial-profiling methods. At least, this is the claim. Law-enforcement investigators have an interest in using DNA analysis to develop the physical profile of the perpetrator of a crime from DNA left at the crime scene. To accomplish this, there has to be a correlation that can be made between genetic sequences (genotype) and physical characteristics (phenotype) of an individual. When eyewitnesses provide a profile of a crime suspect, they usually refer to race, height, hair color, weight, or unusual marks on the individual, such as moles or tattoos. What kind of profile of an individual can one’s DNA provide?

On the basis of the discovery that several broad racial/ethnic population groups have common and distinguishable clusters of DNA sequences, ancestral DNA analysis has become a new method for reifying racial distinctions. Because it was established that DNA variation within ancestral groups was greater than that between groups, there was reason to believe that there would not be a correspondence between genotype and racial/ethnic self-definition.47 But recent studies have shown that there are unique genetic clusters that show a high correspondence with racial/ethnic ancestry. Hua Tang and colleagues analyzed a large multiethnic population-based sample of individuals who participated in a study of the genetics of hypertension. The subjects identified themselves as belonging to one of four major racial/ethnic groups (white, African American, East Asian, and Hispanic). The investigators used 326 genetic markers and concluded: “Genetic cluster analyses of the microsatellite markers produced four major clusters, which showed near-perfect correspondence with the four self-reported race/ethnicity categories.”48 The data showed a strong association between a select group of microsatellites and geographical ancestry. But the authors cautioned that “African Americans have a continuous range of European ancestry that would not be detected by cluster analysis but could strongly confound genetic case-control studies.”49

Classification by racial/ethnic geographical origins appears to be catching on as a popular trend for identifying ancestry. There is also evidence that police investigators have sent crime-scene samples to companies that provide ancestry analysis in order to gain some phenotypic information about crime-scene DNA. One of these companies was the now-defunct company DNAPrint Genomics.50 It advertised its product, called DNA Witness, as capable of determining race proportions from crime-scene DNA. A company advertisement claimed:

The new test provides important Forensic Anthropological information relevant for a wide variety of investigative situations. When biological evidence is gathered, an investigative team can use DNA Witness 2.0 to construct a partial physical profile from the DNA and in many cases learn details about the donor’s appearance, essentially permitting a partial reconstruction of their driver’s license photo.51

But given the admixtures in European and African DNA, the results could be quite misleading and result in mistaken profiling. Probabilistic profiling of crime-scene DNA can lead to harassment of innocent individuals who happen to self-identify with a race or ethnic group. Some experts have argued that because there is no definition of race in genetic terms,52 genetic analysis of crime-scene data as a surrogate of a racial phenotype has no basis in science and should not be used in criminal investigations.

In his book Molecular Photofitting: Predicting Ancestry and Phenotype Using DNA, author Tony Frudakis, a principal in DNAPrint Genomics, cited as the goal of his research (and that of his company) “to establish a method for objectively interpreting an ancestry admixture result in order to safely use the indirect method of anthropocentric trait value inference” such that “knowledge of [genetics of ] ancestry can impart information about certain aspects of physical appearance which is what we are after if we are attempting to characterize DNA found at a crime scene.”53 Frudakis’s working definition of “molecular photofitting” is “methods to produce forensically (or biomedically) useful predictions of physical features or phenotypes from an analysis of DNA variations.”54

At first glance, this is an idea backed by extraordinary hubris, namely, that we can translate the genetic code into physical appearance. This has been referred to as “DNA reverse engineering” or “DNA photofit.”55 Those who have attended their thirtieth-anniversary high-school or college reunion understand that there are some individuals whom we cannot currently identify from the picture that was taken at their graduation. Nevertheless, although the facial characteristics, hair color, or body shape of an individual might have changed radically over several decades, there may be some physical characteristics that remain invariant, such as eye color, skin tone, or hair type. If there are invariant phenotypic characteristics, can they be strongly correlated with DNA alleles? That was the project undertaken by Frudakis in DNAPrint Genomics. He argues that some phenotypes are highly heritable, such as skin color. He uses ancestry data where alleles are selected that have been invariant with respect to certain geographically based populations.

Admixture defines the percentage of the selected alleles in an individual’s genome. When there is a strong correlation between a phenotype and the alleles that define ancestry, Frudakis maintains that a prediction of the phenotype from the percentage of the alleles can be made. One trait that lends itself to this analysis is pigmentation. He claims that “pigmentation traits are under the control of a relatively small collection of highly penetrant gene variants.”56 Thus, when an individual can be characterized by greater than 75 percent West African admixture, it can be inferred that the person has a darker skin shade than someone with less than 35 percent West African ancestry. He developed the melanin (M) index, which is a measure of the skin’s melanin content. Frudakis writes: “With individual admixture estimates and M values it was then possible to search for correlation between admixture and pigmentation among individuals.”57 He claims a “significant correlation between constitutive pigmentation and individual ancestry” in a group of admixed samples.58 If these results are validated in larger databases, then one should be able to predict melanin content (and therefore skin pigmentation, an observable trait) from the percentage of a person’s African admixture (a genetic composition of alleles).

What, if anything, would be problematic about developing a set of statistical correlates between a selection of alleles and a physical trait? When the DNA profile of biological material found at the scene of a crime has no match in the database, criminal investigators could benefit from having some clues in the genetic code about the physical traits (red hair, green eyes, light skin) of the person who left his or her DNA at the scene. We have already noted that the rarer a genetic mutation is, the more helpful it might be in criminal investigation.

DNA Witness was not able to garner general scientific support for its methods. Anthropologist Duana Fullwiley wrote: “DNA Witness falls short of legal and scientific standards for trial and admissibility, while it eludes certain legal logics with regard to the use of racial categories in interpreting DNA.”59

CODIS was established on the premise that its value was in the comparison of two sources of DNA and therefore in the concept of “identity.” The alleles used in the STRs for DNA profiles have no significance for a person’s physical characteristics. At best, even with the full DNA of the biological sample, police will have a probability estimate that the DNA found at the crime scene came from a person with red hair and green eyes, or that a DNA sample consisting of 80 percent African and 20 percent European admixture probably came from an individual with a melanin index (a proxy measure of skin color) of 35–50.60

Those who transition from haplotype ancestry maps of geographically isolated populations to techniques for drawing human physical properties from a DNA sample are making many scientifically contested assumptions. They use a process called Ancestry Informative Marker (AIM) technology. According to Fullwiley,

AIMs-based technologies, like DNA Witness, are attempts to model human history from a specifically American perspective to infer present-day humans’ continental origins. Such inferences are based on the extent to which any subject or sample shares a panel of alleles (or variants of alleles) that code for genomic function, such as malaria resistance, UV [ultraviolet] protection, lactose digestion, skin pigmentation, etc. There is a range of such traits that are conserved in, and shared between, different peoples and populations around the globe for evolutionary, adaptive, migratory, and cultural reasons. To assume that people who share, or rather co-possess, these traits can necessarily be “diagnosed” with a specific source ancestry is misleading.61

Without a cold hit in CODIS the police must resort to traditional policing techniques, which certainly would not include rounding up all redheaded persons with green eyes. But if familial searches are used in CODIS to troll for suspects (see chapter 4), then these gene-to-phenotype correlations may, in the minds of criminal investigators, play a role in narrowing the search. Suppose that a familial search yielded 20 current or past prisoners or, in some states, arrestees. If all the partially matched profiles had additional genetic information accessible to police, then the police could troll through the 20 saved biological samples for a person with red hair and green eyes who was a partial match in the familial search. If the technique described by Frudakis shows increasing promise, there will be pressure to maintain biological samples and to transform CODIS from a DNA profile identity database to a data bank for building physical profiles of individuals from their DNA. Fullwiley believes that these techniques are substantiated neither in ancestry testing nor in forensic phenotyping of DNA: “As a forensics market version of the AIMs technology, DNA Witness may offer precise mathematical ancestry percentages, but the accuracy of that precision remains debatable.”62

Because the national forensic DNA databases have a disproportionately high percentage of African Americans, the traits most common to this group will be sought out in developing profiles of suspects. Moreover, there will be pressure to use the sample population of African Americans in CODIS to refine the genotype-to-phenotype correlations. Although the developers of “molecular photofitting” agree that it is not foolproof, they believe that “there is information about M [pigmentation] we gain by knowing an individual’s genomic ancestry and as long as it is communicated responsibly, this information would be more useful for a forensic investigator as a human-assessed measure of skin color would be.”63 In other words, Frudakis claims that this method is more reliable than eyewitness testimony of skin color while also providing data with a very poor correlation between pigmentation and ancestry.64

The forensic DNA data banks in the United States and the United Kingdom contain a disproportionately high number of people of color because of the demographics of crime and criminal arrests. Even if the purpose of DNA data banks remains true to its original mission of matching the identity of samples, the significant racial skewing of the database, combined with a well-established systemic racial bias in the overall system, means that people of color who commit crimes are more likely to be identified in a DNA match, while white individuals will be more likely to escape detection. The expansion of databases to arrestees will worsen this situation, since decisions concerning who is arrested are highly discretionary and therefore especially prone to bias. Since minorities are arrested disproportionately to their contribution to criminal activity, these communities will be placed under greater DNA surveillance and subjected to greater stigmatization.

In an effort to develop “profiles” of perpetrators from DNA left at a crime scene, the criminal justice community will inadvertently reify race as a scientific term, even though it has been widely discredited and undefined scientifically. From this, new consequences of abuse are likely to result. One of these consequences involves picking up the usual minority suspect from weak probabilistic assignments of skin color from DNA through ancestry analysis. Skin pigmentation is a continuous spectrum from albino to dark brown and every shade in between, with no clear breaks. Race, however, is socially constructed as a two-value concept—black or nonblack (white). When DNA is used to determine pigmentation, the outcome, as interpreted by police investigators, will most likely be that the perpetrator was black or nonblack. If the science remains weak, this type of inference can exacerbate the racialization of criminal justice because society still operates under the one-drop rule. If the forensic investigator estimates that a DNA sample from an individual shows 90 percent European and 10 percent African ancestry, does the one-drop rule imply that he or she should be looking for a person of color? Or does the melanin index (with its poor predictive power) trump ancestry? Although the introduction of these techniques in the courtroom is unlikely, there are no restrictions on their use by police in generating suspects. That is where we can see the confluence of expanded data banks of innocent people, disproportionate numbers of minorities in the data banks, and the use of not-ready-for-prime-time science to invade the privacy of people’s lives.