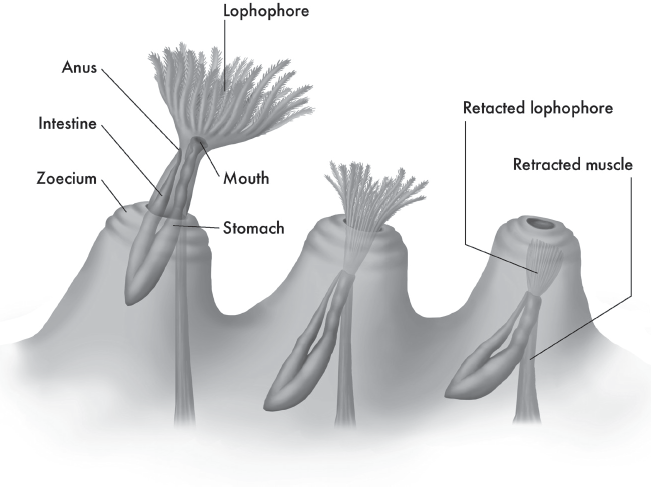

The other living phylum of animals that have lophophores are the bryozoans, or “moss animals.” In contrast to the relatively large brachiopods, bryozoans were tiny creatures similar to the polyps of corals. Like corals, they lived colonially on a massive skeleton of calcite secreted by all of them collectively, and they filter-fed on small food particles from the seawater that passed through their lophophore (fig. 14.1). However, individual bryozoan animals are smaller than even coral polyps. If you are looking at a piece of a colonial fossil and trying to decide if it’s coral or bryozoan, the rule of thumb is this: bryozoans leave pinprick-sized holes, whereas the openings for coral polyps tend to be larger.

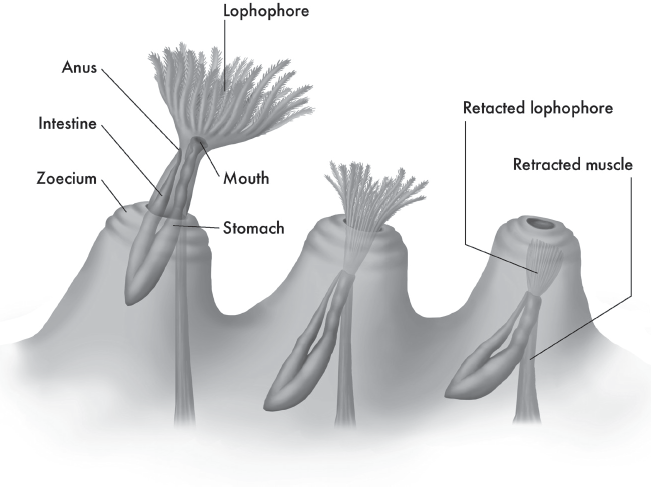

Figure 14.1 ▲

Anatomy of a bryozoan colony, showing the basic structure of the individual animals. (Illustration by Mary Persis Williams)

Bryozoans are still very common in the world’s oceans today, with more than 3,500 living species, and 15,000 or more fossil species as well. They are sometimes known as moss animals because a living bryozoan colony looks like it is covered by a fuzzy coat of moss when all the individual animals are reaching out of their tiny holes and feeding. Despite their incredible living diversity, beachcombers and marine biologists seldom notice them; they are very tiny and are often mistaken for moss or algae.

However, bryozoans are most definitely not built like coral polyps. Instead, they have a large, feathery lophophore that protrudes out of their little hole in the colony when they are feeding. At the base of the lophophore is a U-shaped digestive tract, which takes food brought down from the lophophore and processes it, then excretes it back out the other end through the anus. The individual animals also have simple gonads, excretory systems, and a set of retractor muscles that pull them back into their holes. Most of them have a small lid that closes behind them when they retract, sealing them in their chambers when they are exposed to danger or drying conditions.

Sadly, it is difficult for nonspecialists to identify most bryozoans because their features are extremely tiny, and microscopes and thin sections are required to study them properly. For a book at this level, I won’t try to go into that level of detail. Instead, I will discuss just a few of the more distinctive Paleozoic colonial forms.

MASSIVE AND BRANCHING BRYOZOANS

In the early Paleozoic (especially the Ordovician), there was a great radiation of two groups, the cryptostomes and trepostomes. They are difficult to tell apart without a microscope, so I will just note that they came in a wide variety of body forms. Some, like Prasopora (fig. 14.3A), Rhombopora, and Constellaria (fig. 14.3B), formed massive disk-like colonies that occasionally reached 2 feet across, but most were usually only a few inches long. Others, like Dekayella, Prismopora, Streblotrypa, Leioclema, and Thamniscus, grew into distinctive branching forms, with each branch covered with hundreds of tiny pinprick-sized holes (see fig. 14.2).

Figure 14.2 ▲

Sketches of common fossil bryozoans. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Figure 14.3 ▲

Typical bryozoans: (A) the massive bryozoan Constellaria, which gets its name from the star patterns on its surface; (B) the lumpy bryozoan Prasopora; (C) the lacy bryozoan Archimedes with lacework arranged in a corkscrew spiral around a central stem, which is what usually fossilizes; and (D; color figure 4) restoration of Archimedes in life (see also color plate 2). ([A–C] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [D] illustration by Mary Persis Williams)

In the late Paleozoic (especially the Mississippian), there was a great radiation of another group, known as the fenestrate or fenestrellid bryozoans, such as Fenestella and Fenestrellina (see fig. 14.2). These formed a lacy framework with a grill-like pattern in detail. Their name refers to the window-like openings in the grillwork (fenestra is “window” in Latin). They are very common in Mississippian limestones and shales.

The most distinctive of all the fenestrellids was a genus named Archimedes. This bryozoan colony was built like a large corkscrew in shape, with the lacy fan of grillwork fanning around the spiral (fig. 14.3C–D). Their tiny corkscrew-like central columns are extremely common in some Mississippian shales, and they are a good index fossil of the Mississippian. They were named after the famous Hellenistic Greek inventor, scientist, and mathematician Archimedes. One of his many famous inventions was a water pump known as the “Archimedes screw.” It was built of a long tube with a corkscrew-like set of blades inside. If you plunged one end of the tube into water and turned the corkscrew blades, they lifted water up the tube to a different level. The paleontologist who first named this fossil was inspired by the corkscrew-like shape of the fossil and named it after the famous Greek inventor of that device.

The trepostome, cryptostome, and fenestrate bryozoans dominated the Paleozoic, then all of their huge diversity was wiped out by the great Permian mass extinction, along with most of the brachiopods, the tabulate and rugose corals, and most other common Paleozoic groups. Only a few Paleozoic groups, such as the cyclostomes, managed to survive. During the Mesozoic, bryozoans slowly recovered, but they were dominated by a Jurassic group known as the cheilostomes, which are still the most diverse type of bryozoans in modern oceans. Today, most bryozoans are found encrusting shells of other animals or living in small clumps and clusters on the seafloor.