Everyone loves dinosaurs, and most of us have at least some interest in how vertebrates evolved because we humans are vertebrates (fig. 19.1). However, most vertebrate fossils are extremely rare, and they are not easy to collect or own. The key fossils that tell the story of how vertebrates evolved from one group to another are all in museums, and paleontologists as well as the casual collector can see many of them on display, and sometimes purchase replicas.

Figure 19.1 ▲

Evolutionary radiation of the vertebrates. The first branch point is the jawless fish, followed by the sharks, and then the extinct placoderms. To the left of that are the earliest relatives of advanced fish (the acanthodians), then the huge evolutionary radiation of bony fish. The remaining branches are amphibians, reptiles (with birds branching from dinosaurs), and mammals. (Illustration by Mary Persis Williams)

My approach in this chapter is not to tell the entire story of vertebrate evolution, which is covered in many other books, including my books Bringing Fossils to Life: An Introduction to Paleobiology, The Story of Life in 25 Fossils, and Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why It Matters. Instead, I will briefly describe the major groups that occur in important fossil localities and explain how they can be identified.

JAWLESS FISH

The earliest vertebrates did not have jaws, but they did have bony armor surrounding their bodies that was held up by an internal skeleton made of cartilage (fig. 19.2A). During the Silurian and especially the Devonian, there was a huge evolutionary radiation of these jawless fish (often called by the wastebasket name “agnathans”). These included the bottom-dwelling osteostracans or “ostracoderms,” which had a broad flat-bottomed horseshoe-shaped head shield with upward facing eyes, and a tail like that of a shark, with the lobe bent upward (fig. 19.2B); the tadpole-shaped heterostracans, which had a large head and body shield and a tail with the lobe pointed downward (fig. 19.2C); and the anaspids (fig. 19.2D) and the thelodonts, which were small fish with a slit-like mouth, a downward-pointing lobe on the tail, and were fully covered by a sort of chain mail of small bony plates. All of these Devonian jawless fish vanished in the Late Devonian extinction event.

Figure 19.2 ▲

(A) Three typical examples of jawless fossil fish: the heterostracan Pteraspis (top), which had a streamlined head shield; the osteostracan Hemicyclapsis (middle), with the large horseshoe-shaped, flat-bottomed head shield; and the scaly Birkenia (bottom), with the slit-like mouth, downturned tail fin, and numerous spines. (B) Nearly complete specimens of Hemicyclaspis. (C; color figure 9) Head shield of Pteraspis. (D) Nearly complete fossil of Birkenia. ([A] Redrawn from several sources by Mary Persis Williams; [B–D] courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The only survivors of the radiation of jawless fish are two groups of extremely specialized jawless vertebrates: lampreys and hagfish. The lampreys are adapted to latching onto the side of a fish and sucking on them as parasites. The hagfish lives in the bottom muds, slurping up worms, or eating a fish carcass from the inside. Neither of these fish is typical of their jawless ancestors. They were adapted for their peculiar scavenging lifestyle and have completely lost their bony armor; all that remains is their cartilage skeleton.

Fossils of jawless fish are extremely rare, but certain localities have famous fish beds where these fish are occasionally found by collectors. These sites include the famous fish beds of the Old Red Sandstone in England and Scotland, the Devonian beds of the Catskill Mountains of New York, Devonian beds in Scaumanec (or Escuminac) Bay in the Gaspé Peninsula in Quebec, the Cleveland Shale in Ohio, and a few other Devonian sites. Fossils of jawless fish are on display in many natural history museums, although their small size and incomplete preservation makes them less impressive to see than other fish fossils.

PRIMITIVE JAWED FISH: PLACODERMS, SHARKS, AND THEIR RELATIVES

The evolution of jaws was an important breakthrough in vertebrate evolution. Jawless fish are severely limited by their simple sucker-like mouths. They could only feed on detritus on the sea floor, filter-feed in the plankton, or become scavengers like the hagfish and lamprey. Jaws made it possible for fish to feed on many different types of food (especially larger prey) and to chop it into digestible pieces, but jaws are used by vertebrates in many other ways as well. For example, jaws are used for digging holes, carrying pebbles or vegetation to build nests, grasping mates during courtship or copulation, carrying their young around, and making sounds or speech.

Several groups of early jawed vertebrates are found in the fossil record. The earliest were an extinct group of highly armored fish known as placoderms. Their body was held up by cartilage, and large bony plates covered their head and the front of their bodies. Some of them, such as the Late Devonian monster predator Dunkleosteus (originally known as Dinichthys), were 33 feet (10 meters) long, by far the largest predators on Earth at that time (fig. 19.3A–B). The antiarchs and other smaller fish were armored all the way down to the base of the tail, and their appendages were also armored and resemble crab legs (fig. 19.3C–D). Still others were shaped like rays, or like the Port Jackson shark. The radiation of jawed placoderms dominated the Devonian seas and were particularly abundant in famous Upper Devonian fish beds such as the Old Red Sandstone in Great Britain or the Cleveland Shale in Ohio. Most are not easy to collect, but some are on display in museums around world.

Figure 19.3 ▲

Examples of fossil placoderms: (A; color figure 10) head and body shield of the giant arthrodire Dunkleosteus; (B) reconstruction of Dunkleosteus; (C) head and body shield and armored appendage of the small, bottom-dwelling antiarch Bothriolepis; and (D) a reconstruction of Bothriolepis in life. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The most commonly collected of primitive jawed vertebrates are the sharks, whose abundant teeth can be found in many localities around the world and are easy to collect or purchase. Sharks began to evolve in the Late Devonian side by side with the enormous radiation of jawless fish and placoderms. The latter two groups vanished during the Late Devonian extinction event, but sharks survived and continued to evolve in the late Paleozoic and Mesozoic, and they continue to thrive today. Sharks are highly diverse in the modern oceans, and a lot is known about their biology and evolution.

Sharks have an internal skeleton made of cartilage, which rarely fossilizes. However, they have some bone in the denticles in their skins (giving sharkskin its typical rough texture), in the spines on the front edge of their fins, and especially in their teeth. A shark’s mouth has hundreds of teeth at any given time. Only the teeth at the front of the jaw are in active use. As these teeth become worn down or broken, they are shed and more teeth grow in behind them. This is the reason sharks leave so many teeth in the fossil record, and why they are so easy to collect and own.

The evolution of shark teeth is quite a remarkable story in itself. In the Late Devonian, primitive sharks like Cladoselache (fig. 19.4A–B) were up to 6 feet (2 meters) in length, and they had teeth with a simple conical cusp in the center and small pointed cuspules on each side. Unlike more advanced sharks, their pectoral fins had a rigid broad base, so they could not maneuver in the way more advanced sharks do.

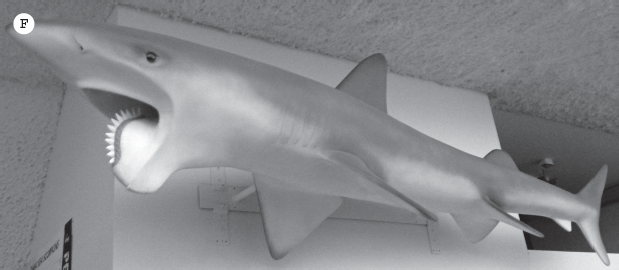

Figure 19.4 ▲

Fossil sharks: (A) the primitive Devonian fossil shark Cladoselache, from the Cleveland Shale and (B) a reconstruction of Cladoselache; (C) the peculiar Carboniferous-Permian xenacanth or pleuracanth sharks and (D) a reconstruction. (E) These weird tooth whorls called Helicoprion were long a mystery. (F) Modern restoration of the shark that carried the tooth whorls. (G) Life-sized reconstruction of the gigantic great white shark Carcharocles megalodon from the Miocene and (H) a typical C. megalodon tooth surrounded by teeth of Isurus, the mako shark. ([A, C, E] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [B, D] courtesy of N. Tamura; [F–G] photographs by the author; [H] courtesy of R. Irmis)

In the late Paleozoic, eel-shaped xenacanth or pleuracanth sharks up to 10 feet (3 meters) long lurked in the oceans and swamps (fig. 19.4C–D). Their teeth have a pair of sharp prongs forming a V-shape. Another weird Paleozoic shark was the maker of the spiral whorls of shark teeth known as Helicoprion (fig. 19.4E). Recent discoveries have revealed the shape of this shark and how it carried its tooth whorl (fig. 19.4F). Later sharks have an even wider variety of shapes and sizes of teeth, and the living sharks still show tremendous variation. Some of the most popular are the huge teeth of Carcharocles megalodon, the gigantic great white sharks that may have reached 82 feet (25 meters) in length (fig.19.4G). Their teeth (fig. 19.4H) are particularly common in the Miocene marine rocks at places like Sharktooth Hill in California, the Calvert Cliffs in Chesapeake Bay in Maryland, or Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina. The distinctive asymmetrical triangles of mako shark (Isurus) teeth are also commonly found in those same beds, as well as the pavement teeth of skates and rays. Collecting fossil shark teeth is popular in many parts of the world, and many different kinds of shark teeth are available for sale on the commercial market.

BONY FISH: OSTEICHTHYES

The skeletons of sharks, placoderms, and jawless fish are mostly made of cartilage; they have bone only in their external armor, their teeth, or spines. The other main branch of fish is the bony fish, or Osteichthyes. Their skeleton is mostly made of bone, and they have additional bones on the surface of their body, on their skull, and elsewhere.

One branch of the osteichthyans is the lobe-finned fishes, or sarcopterygians. They have fleshy and muscular fins and have just a few robust bones that match the bones in our arms and legs. Lobe-finned fish include the fossil and living lungfish, the coelacanths, and an extinct wastebasket group called the “rhipidistians,” which gave rise to amphibians. Nearly all of these fish are rare and hard to collect.

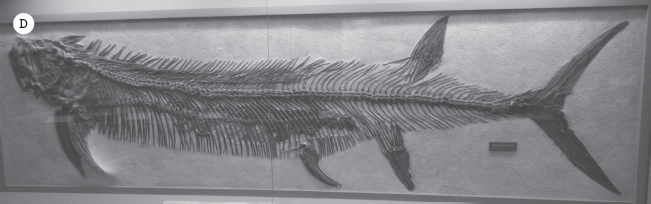

The other main branch of bony fish is the actinopterygians, or ray-finned fish, which includes fish whose fins are supported by many parallel rays of bone. A Devonian group called the palaeoniscoids have the most primitive structures among ray-finned fish (fig. 19.5A–B). The next most advanced fishes in this lineage are represented by the sturgeon, the paddlefish, the bichir, and their extinct relatives from the late Paleozoic, which used to be lumped into a wastebasket group called the “chondrosteans.” These fish have dense areas of bone in their skulls but have a primitive jaw mechanism and primitive fins (especially the tail fin). During the Mesozoic, another great evolutionary radiation of more advanced fish, known by the wastebasket group “holosteans,” were the dominant fish on Earth, but today only a few survive, including the gar fish (fig. 19.5C) and Amia, the bowfin. All of these archaic fish are collected in important Paleozoic and Mesozoic fish localities, and some are also sold on the commercial market as well.

Figure 19.5 ▲

Examples of well-known fossil bony fish: (A) the primitive bony fish from the Permian, Palaeoniscus and (B) a reconstruction of the palaeoniscoid fish Cheirolepis; (C) a large gar Lepisosteus, one of the most primitive living bony fish, from the Green River Formation. (D) This specimen of the gigantic ichthyodectiform Xiphactinus from the Cretaceous chalk beds of western Kansas has swallowed a smaller fish. (E) The herring Knightia is the most common fish from the Eocene Green River Formation; and (F) the larger herring relative Diplomystus is the second most common fish in the Green River Formation. ([A, C, E] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [B] courtesy of N. Tamura; [D, F] photograph by the author)

By far, the largest group of fish is the advanced ray-finned fish, or the teleosts. There are more than 20,000 living species of teleosts; they are as diverse as all other fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds put together. In fact, nearly every familiar fish you find in an aquarium or fish market or anywhere else (except for sharks and the fish just mentioned) is a teleost. Although we are mammal chauvinists and like to call the Cenozoic the Age of Mammals, it could really be called the Age of Fish. In fact, a lot more species of teleosts were evolving in the Cretaceous or Cenozoic than there were dinosaurs or mammals. Among the most primitive teleosts were the giant, impressive fish called Xiphactinus (formerly Portheus), from the Cretaceous seaways of western Kansas; you will find them on display in many places in the world (fig. 19.5D).

Nearly any fish fossil that is easy to collect in the United States or that is available on the open market is a teleost as well. This includes the fossils found in huge deposits of Eocene lake sediments of the Green River Formation in Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado, which have produced thousands of beautiful fish specimens, especially the common small fish Knightia or the larger Diplomystus, which can be found in all the commercial markets (fig. 19.5E–F). A number of other localities around the world produce complete, articulated fish specimens like those of the Green River Shale. Fossil fish can be found in just about any exposure of the Green River Shale, although the best collecting is in commercial fish quarries such as the Ulrich operation, which tends to be clustered around Fossil Butte National Monument in Kemmerer, Wyoming. Other legendary localities for complete teleost fish include the Eocene beds of Monte Bolca in Italy and Messel in Germany. In collecting, however, it is much more typical to find only a partial fish, or a bunch of isolated fish bones. A good fish paleontologist can identify most familiar fishes from just a few isolated bones.

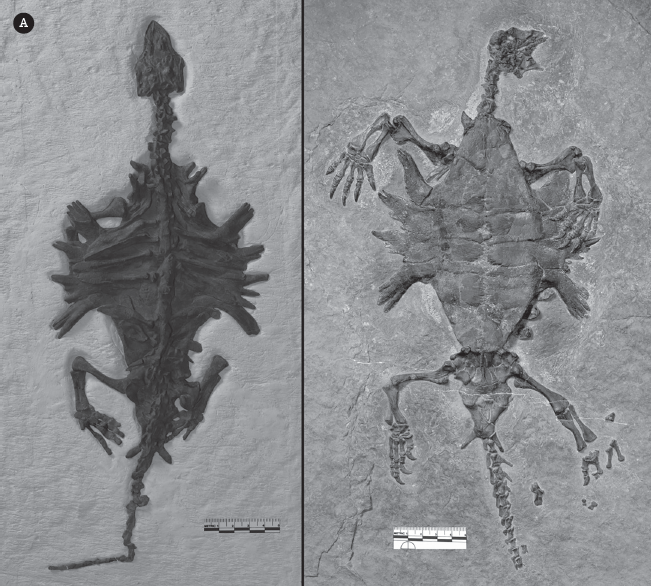

CLASS AMPHIBIA: AMPHIBIANS AND THEIR RELATIVES

During the Late Devonian, one group of lobe-finned fishes known as “rhipidistians” gave rise to the first great radiation of land vertebrates, the four-legged animals, or tetrapods, informally known as the “amphibians.” We now have many fossils that show this transition from lobe-finned fish to tetrapod, including Tiktaalik (see chapter 4) and Ichthyostega and Acanthostega. These more advanced transitional fossils still have fish-like features, such as gill slits and a large fin on the tail, and they have sense organs adapted for water and not land. Although their lobed fins were modified into limbs for crawling, analyses show they probably didn’t crawl on land much but used their limbs for moving along the water bottom, as modern newts do.

By the late Paleozoic, these primitive tetrapods had evolved into three major groups that were among the largest land animals, especially during the Carboniferous and Permian. They were first discovered in Upper Carboniferous mines that were extracting the coal made in ancient swamps where they once lived. In some mines, skulls were found embedded in the mine walls, and others were exposed when coal-rich shales were split open. The best known of these tetrapods come from the Lower Permian red beds around Seymour, Texas, where they can be collected today. One group of tetrapod was the long, flat-bodied crocodile-like temnospondyls (once called “labyrinthodonts”). The biggest ones included Eryops, which reached 6 feet (2 meters) in length, with a big flat skull that was one-fifth its body length (fig.19.6A). An even bigger temnospondyl from the Lower Permian red beds of Texas was Edops, which is known only from a skull, but that skull is quite a bit larger than Eryops. In the Triassic, the temnospondyls were in decline, but huge flat-bodied metoposaurs like Buettneria (fig. 19.6B–C) were still common in the Petrified Forest National Park and in the Painted Desert of Arizona.

Figure 19.6 ▲

Examples of well-known extinct amphibians: (A) the giant Permian temnospondyl Eryops; (B) the flat-bodied Triassic temnospondyl Buettneria and (C) a reconstruction of Buettneria in life; (D) the boomerang-headed lepospondyl Diplocaulus; (E) the reptile-like “anthracosaur” Seymouria; (F) the transitional fossil between frogs and salamanders, Gerobatrachus, nicknamed the “Frogamander”; and (G) the Permian fossil closest to the root of modern amphibians known as Cacops. ([A–E] Photographs by the author; [F] courtesy of J. Anderson; [G] courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

A second radiation of tetrapods in the late Paleozoic was the lepospondyls, which tended to be smaller and more like salamanders. One group, the microsaurs, was extremely lizard-like, with a deep skull, a cylindrical body, and relatively tiny limbs. Another group, the aistopods, secondarily evolved a limbless snake-like body, convergent on many other animals (including not only snakes but also apodan amphibians and amphisbaenid reptiles) that have lost their legs and become snake-like. The most odd-looking lepospondyls from the Lower Permian red beds are nectrideans like Diplocaulus, which had a huge boomerang-shaped head on a salamander-like body (fig. 19.6D).

The third major group of late Paleozoic tetrapods was the anthracosaurs (“coal lizards” in Greek because many early specimens were found in coal deposits). This wastebasket group is actually more closely related to reptiles than it is to amphibians. Like reptiles, they had a deep skull with a short snout (rather than the flat skull with the long snout in temnospondyls), large eyes, strong legs, and a relatively short body and tail, suggesting that they were much less aquatic and more terrestrial than the other two groups. They show many anatomical features of reptiles as well, suggesting that they are transitional forms between amphibians and reptiles. Some, like Seymouria from the Lower Permian red beds near Seymour, Texas, are remarkably reptilian in all but a few features (fig. 19.6E).

All three of these groups of archaic tetrapods were extinct by the end of the Triassic. However, the Lower Permian red beds of Texas also yield fossils such as Gerobatrachus hottoni, the “Frogamander,” a fossil with the head and broad snout of a frog but the body of a salamander (fig. 19.6F). By the Triassic, numerous transitional fossils (such as Triadobatrachus) to frogs had a basically frog-like build but still did not have the specialized spine and hips seen in modern frogs, nor were their legs as long and adapted for leaping. These fossils, as well as all living frogs and salamanders, have a number of distinctive anatomical features (such as teeth on pedestals with a distinctive base) that link them to a group of Permian temnospondyls like Cacops (fig. 19.6G) and Doleserpeton. From these early Mesozoic origins, frogs and salamanders have undergone a huge evolutionary radiation, and 4,000 species are still alive today. Frog and salamander fossils are not common, but complete frog fossils have been collected from the Green River Shale of Wyoming.

CLASS REPTILIA: REPTILES

We are all familiar with the living reptiles, including turtles, snakes, lizards, and crocodilians, but the fossil record of reptiles includes many more groups, especially dinosaurs, plus the flying reptiles (pterosaurs), the marine reptiles such as the dolphin-like ichthyosaurs and the paddling plesiosaurs, and many others (fig. 19.7). Most extinct reptiles, such as dinosaurs, were quite rare compared to invertebrate fossils, and good fossil specimens are normally collected by professional researchers for museums. But many other fossil reptiles are relatively easy to collect, and many people have done so or bought them from rock shops and other dealers.

Figure 19.7 ▲

Family tree of reptiles and other amniotes. The anapsids, the most primitive amniotes known (such as the Carboniferous fossils Westlothiana and Hylonomus), gave rise to two branches: the synapsids and their mammalian descendants and the Reptilia. The most primitive branch of reptiles is the turtles, and the dolphin-like ichthyosaurs and the paddling plesiosaurs are both major groups of Mesozoic marine reptiles. The Lepidosauria include the living sphenodontids (the tuatara and its ancestors) and the squamates, or the lizards and snakes. The Archosauria include the archaic archosaurs (formerly called “thecodonts”), the crocodilian branch, the flying pterosaurs, and the dinosaurs. One branch, the Saurischia, includes the giant sauropods and the predatory theropods, which gave rise to the birds. The ornithischian dinosaurs include mostly herbivorous forms: duckbills, horned dinosaurs, stegosaurs, ankylosaurs, and their kin. (Illustration by Mary Persis Williams)

The living reptiles fall into several groups, which have many more fossil relatives. The most primitive living reptiles are turtles and tortoises (Anapsida), and they have many extinct relatives in the late Paleozoic and Triassic. The remaining reptiles are now lumped into a broadly defined group called the Diaspida. One branch, the Euryapsida, includes the extinct marine reptiles such as the plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs. The other branch (the Sauria) is divided into two main groups: the lizards and snakes (Lepidosauria) and their relatives, and the Archosauria, which includes crocodilians, dinosaurs, birds, and many extinct groups.

ANAPSIDA: TURTLES AND THEIR RELATIVES

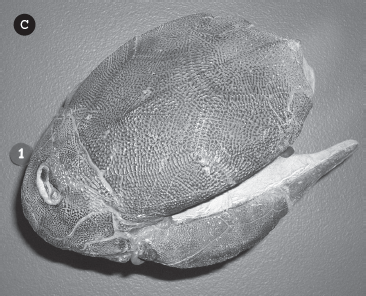

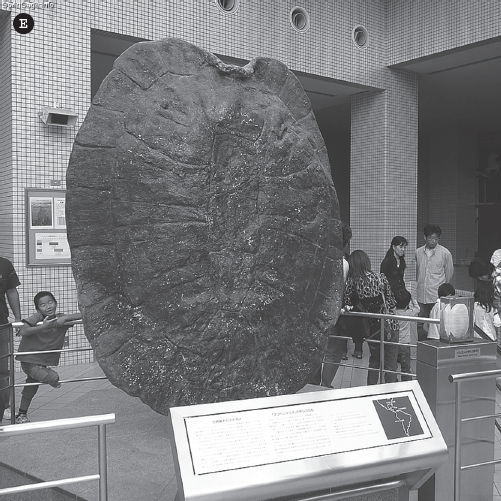

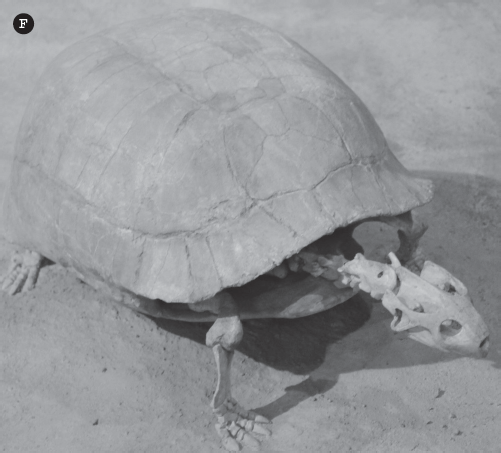

The anapsids include a variety of strange reptiles of the late Paleozoic. The huge pariesaurs were heavily built, thick-limbed hippo-sized herbivores whose dense bony skulls were covered with warts and knobs of bone. Others, such as the procolophonids and captorhinids, were built like medium-sized lizards, but the details of their skulls were very turtle-like. The turtles and tortoises have a very impressive fossil record because they tend to have heavy dense bones and their shells are easily fossilized. The oldest turtle relatives from the Permian include Eunotosaurus from 260 million years ago, which already had broadly flared ribs in the back that were precursors to their back shell (carapace), as well as many other turtle-like features of the skeleton. By 240 million years ago, fossils like Pappochelys (“grandfather turtle” in Greek) had broad flattened ribs on their back and also broad ribs in the belly region called gastralia, which were the precursor to the belly shell (plastron). Even more of a transitional fossil is Odontochelys semitestacea, the “turtle on the half shell” from the Triassic of China (fig. 19.8A–B). Its name literally means “half-shelled toothed turtle” in Greek; it had a shell on its belly but still had only the broad flared ribs on its back, not a carapace. In addition, it was the last turtle known to still have teeth; all later turtles had a toothless beak. By 215 million years ago, in the Late Triassic, we see fossil turtles like Proganochelys (fig. 19.8C), which had a complete carapace, but no teeth. It also had many other advanced turtle features. However, unlike any living group of turtles, Proganochelys could not pull its neck and head into its shell; instead, its head was heavily armored. By the Cretaceous, enormous sea turtles like Archelon, from the chalk beds of western Kansas (fig. 19.8D), were more than 12 feet (3.5 meters) long. In the Cenozoic, the largest of the enormous freshwater turtles was Stupendemys from the Miocene of Brazil (fig. 19.8E). Its shell alone was 11 feet (3.3 meters) long.

Figure 19.8 ▲

Examples of well-known fossil turtles. (A) Odontochelys semitestacea, the Permian turtle with a shell on its belly but not on its back, and still retaining teeth, and (B) a reconstruction showing shell placement. (C) Proganochelys, a Triassic turtle with both shells but no teeth and a nonretractable head covered by armor. (D) The enormous Cretaceous sea turtle Archelon, the largest turtle that ever swam the oceans. (E) The shell of the gigantic Miocene freshwater turtle Stupendemys, the largest turtle on the land. (F) The common tortoise of the early Oligocene of the Big Badlands of South Dakota, Stylemys nebrascensis. ([A–B] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [C–F] courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

During the Mesozoic, the major group of living turtles evolved, and they tended to leave an excellent fossil record because their shell is so thick and durable. In many dinosaur beds around the world, the first fossils found are broken scraps of turtle shell. Although these scraps are hard to identify, they are a good indicator that you’re collecting in the right place. In some fossil beds, such as the Big Badlands of South Dakota, fragments of shell of the tortoise Stylemys nebrascensis (fig. 19.8F) are the most common fossils found, and occasionally a complete turtle shell is found.

EURYAPSIDA: ICHTHYOSAURS AND PLESIOSAURS

During the Mesozoic, the top predators in the oceans included a variety of reptiles. There were enormous sea turtles like Archelon, but the biggest predators were all euryapsids. Two main groups fought for control of the seas: ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs.

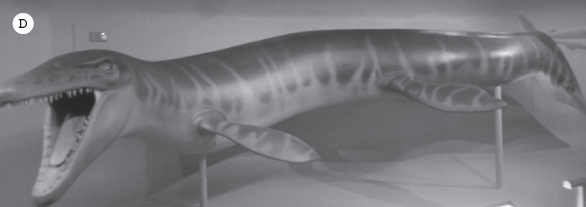

The most specialized were the dolphin-like ichthyosaurs, which had a highly streamlined fish-like body (fig. 19.9A). Their hands and feet were completely modified to flippers, and they had a large dorsal fin, a tail fin, and a long narrow snout full of conical teeth for catching aquatic prey like fish, ammonites, and squid. Most of them had large eyes for seeing in dim murky water. The largest included the huge 49-foot-long whale-sized Shonisaurus (fig. 19.9B). This amazing creature can be seen at Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park near Gabbs, Nevada, and it also is on display in the Nevada State Museum in Las Vegas; it is the official Nevada State Fossil. Many museums display extraordinary complete articulated skeletons of ichthyosaurs that even show the dark film of the outline of their bodies (see fig. 2.4B), typically from the Jurassic Holzmaden Shale of Germany (fig. 19.9C). Ichthyosaurs had short paddles and fish-like bodies, so they could not crawl onto land to lay their eggs as sea turtles do. They must have given live birth in the ocean, as dolphins and whales do. One of the Holzmaden ichthyosaurs was fossilized in the process of giving birth (fig. 19.9D); the baby can be seen emerging from the birth canal.

Figure 19.9 ▲

Ichthyosaurs: (A) reconstruction of a typical Ichthyosaurus from the Jurassic; (B) the largest known ichthyosaur, Shonisaurus, from the Triassic Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Nevada; and (C) two large ichthyosaurs in the Natural History Museum in London. (D) Some of the Holzmaden ichthyosaurs were buried and fossilized at the very moment that they were giving birth. The baby ichthyosaur can be seen emerging tail first from the birth canal. ([A] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [B–D] photographs by the author)

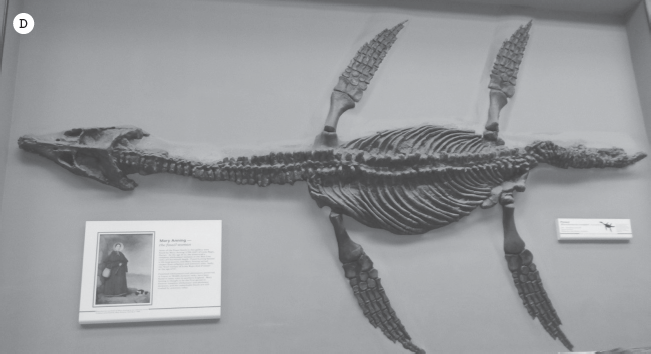

The largest marine reptiles, however, were the plesiosaurs (fig. 19.10A). They had massive bodies with huge paddles on all four limbs to slowly but steadily row through the water. One group (the elasmosaurs) had a long snake-like neck that allowed them to reach prey (fish and squid) far from their rather slow-moving bodies (fig. 19.10B). The largest of these elasmosaurs were up to 33 feet (10 meters) long. But even bigger were the pliosaurs, which had a short neck but a massive head with long jaws. The biggest of these was Kronosaurus from the Cretaceous of Australia, which reached 42 feet (12.8 meters) in length (fig. 19.10C). Popular media has reported that there were even larger plesiosaurs, such as Liopleurodon, which reached 82 feet (25 meters) in length. However, these claims were made from examining incomplete specimens, and there is no strong evidence to back up this assertion. Plesiosaurs have been found in many parts of the world, especially in the Jurassic beds of Europe (fig. 19.10D), and they are particularly common in the Cretaceous beds of the Great Plains. Many elasmosaurs have been found in the chalk beds of Gove County in western Kansas, and others are still found there today.

Figure 19.10 ▲

Plesiosaurs. (A) An 1863 reconstruction of an ichthyosaur battling a plesiosaur in the Jurassic seas of England. (B) Elasmosaurus had the longest neck of any plesiosaur. (C) Pliosaurs were short-necked but long-snouted plesiosaurs. This is Kronosaurus, the largest plesiosaur ever found. (D) Typical Jurassic plesiosaurs had intermediate neck lengths and smaller heads, such as this Rhomaleosaurus from England. ([A–B] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [C] courtesy of Ernst Mayr Library, Harvard University; [D] photograph by the author)

LEPIDOSAURIA: LIZARDS AND SNAKES

Lizards and snakes are the most common and familiar reptiles we see today. More than 6,000 species of lizards and 2,500 species of snakes (compared to only 250 species of turtles and about 25 species of crocodilians) are alive today. The living lepidosaurs are recognized by a number of unique anatomical features, including their forked tongue used to taste the scent in the air, their distinctive scales made of two kinds of keratin protein, and numerous other features. Except for the lizard-like tuatara (a sphenodontid) from the islands of New Zealand, all the remaining lepidosaurs are squamates, with many distinctive anatomical features, including a skull made of bony struts so it is highly flexible and a jaw that can open very wide to eat large prey.

The oldest unquestioned lizard fossils are from the Late Jurassic. They subsequently diversified into dozens of families with over 6,000 species during the Cretaceous and the Cenozoic. Complete lizard fossils are relatively rare and tend to be found only in extraordinary fossil deposits, such as the Eocene Green River Shale of Wyoming (fig. 19.11A) or the Messel beds in Germany. However, if you collect tiny fossils in Mesozoic and Cenozoic beds, individual small bones of lizards can be quite common. Some lizards were truly impressive, such as the gigantic monitor lizard Megalania from the Ice Age beds of Australia. It reached 20 feet (6 meters) in length, twice the size of its close living relatives, the Komodo dragon (fig. 19.11B).

Figure 19.11 ▲

Lizard and snake fossils and their kin. (A) The lizard Saniwa from the Eocene Green River Shale. (B) The giant Komodo dragon Megalania from the Ice Age beds of Australia. (C) The enormous mosasaur Tylosaurus, more than 43 feet (13 meters) long. (D) Reconstruction of a mosasaur swimming in the Cretaceous seas. (E) The Cretaceous fossil snake Tetrapodophis, which still had four tiny vestigial legs. (F) The Eocene Green River boa constrictor Boavus. (G; color figure 11) Reconstruction of the school-bus-sized Paleocene anaconda Titanoboa. ([A–C, E] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [D, F–G] photographs by the author)

The monitor lizards had an important descendant: the marine reptiles known as mosasaurs (fig. 19.11C–D). These were just like Komodo dragons in their basic anatomy, but their hands and feet were modified into flippers, and their long flat tail helped them swim. Mosasaurs became famous when they were featured in the movie Jurassic World. The creature that jumps out of the water in that movie to eat a shark is much larger than any mosasaur ever known. Nevertheless, mosasaurs were one of the dominant marine predators in the Late Cretaceous. Many have been found in the inland sea deposits of Kansas and South Dakota, and their fossils (especially teeth) are still collected there today.

During the Cretaceous, one group of lizards (probably the monitor lizards, or Varanidae) became specialized for burrowing and lost their limbs to become snakes. Numerous fossils of Cretaceous snakes with tiny vestigial front and hind limbs are now known, showing how the transition took place (fig. 19.11E). Complete snake fossils are even more rare, and they only occur in a few unusual deposits such as the Eocene Green River Shale (fig. 19.11F). Their individual vertebrae are often found along with other tiny fossils in Cretaceous and Cenozoic beds in many places. Some of them reached enormous size, such as the Paleocene anaconda from Colombia known as Titanoboa, which was as long as a school bus (fig. 19.11G).

ARCHOSAURIA: CROCODILIANS, PTEROSAURS, DINOSAURS, BIRDS, AND THEIR RELATIVES

Based on many lines of both anatomical and molecular evidence, crocodilians and birds are closely related among all living vertebrates. Together they define a group known as the archosaurs (“ruling reptiles” in Greek), which also includes dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and many other extinct groups. Many unique anatomical features help us recognize all archosaurs, including distinctive features of the skull, lower jaw, braincase, and especially their tendency to have an upright or semi-upright posture, with their limbs beneath their bodies, rather than sprawling on their bellies with their limbs splayed out to the side as lizards do. The living crocodilians and birds have many other anatomical features that do not fossilize, such as the structure of their three-chambered heart, the muscular diaphragm to assist breathing, and a muscular gizzard in their digestive tract to grind up food (very few archosaurs have teeth or jaws that allow much chewing).

During the Triassic, a great radiation of primitive archosaurs dominated all the terrestrial habitats on Earth. Some were herbivores, such as the pig-like rhynchosaurs, which had hooked beaks and short stubby legs (fig. 19.12A). The aetosaurs had backs covered in thick plates of armor, often with spines sticking out of their sides and shoulders, and an upturned snout (fig. 19.12B).

Figure 19.12 ▲

Archosaurs and crocodilians. (A) The Triassic herbivores known as rhynchosaurs had a beak and a long, low-slung body. (B) In Petrified Forest National Park, the erythrosuchids (left) were major predators, and their prey, which included aetosaurs (right), were protected with armored backs fringed with spikes. (C) The crocodile-mimic phytosaurs had a long narrow snout for catching fish, but they were unrelated to crocodilians. (D) The enormous Cretaceous crocodilian Deinosuchus probably preyed on small dinosaurs. (E) The Miocene caiman Purussaurus was almost as large. ([A] Courtesy of N. Tamura; [B–C, E] photographs by the author; [D] courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History)

Most, however, were carnivorous reptiles. The erythrosuchids (“bloody crocodiles” in Greek), also known as the rauisuchids, were the largest predators, with long quadrupedal bodies and deep skulls armored with sharp recurved teeth (fig. 19.12B). The phytosaurs looked very much like large crocodiles, except that they had their nostrils on the top of their heads, not on the tip of the snout as in all crocodilians (fig. 19.12C). The earliest crocodilians can be found in the Late Triassic as well, but they were small, skinny, long-legged creatures with short snouts. They did not begin to become big aquatic long-snouted predators until the phytosaurs vanished and vacated that ecological niche.

During the Jurassic and Cretaceous, there were many now extinct lineages of crocodilians. Some were completely marine with a tail fin (geosaurs), and Sebecus had a tall narrow snout like T. rex. Then there were the huge Cretaceous crocodilians Deinosuchus (“terrible crocodile” in Greek) and Sarcosuchus (“flesh crocodile” in Greek), which were 50 feet (15 meters) long, with a skull over 6 feet (2 meters) long. They were large enough to eat small dinosaurs (fig. 19.12D). In the Miocene of South America, the giant caiman alligator Purussaurus was almost as large (fig. 19.12E).

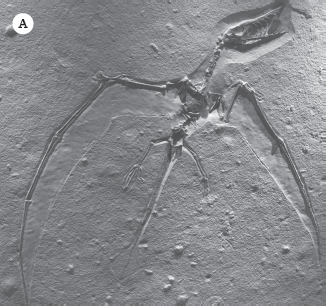

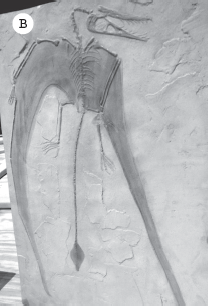

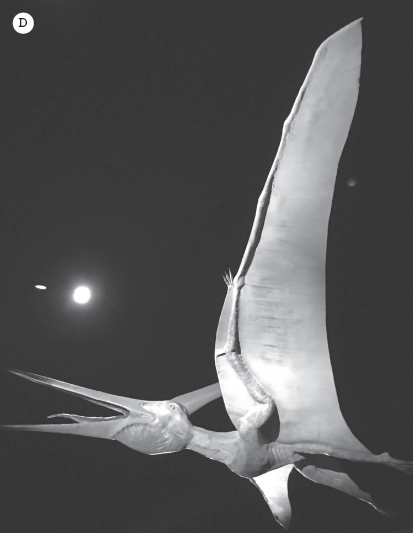

The crocodilian branch of the archosaurs dominated in the Triassic but were extinct by the Jurassic (except for crocodilians) because the other branch of archosaurs, the dinosaurs, arose to crowd them out. This second branch includes the flying reptiles, or pterosaurs, which first appear in the Late Triassic. The earliest pterosaur, Eudimorphodon, had a primitive archosaurian head but fully developed wings and the ability to fly. Through the rest of the Jurassic and the Cretaceous, pterosaurs evolved into an incredible variety of forms, from small crow-sized pterosaurs like Pterodactylus (fig. 19.13A) and the vane-tailed Rhamphorhynchus (fig. 19.13B) to the huge Pteranodon (fig. 19.13C–D) with a wingspan of 22 feet (7 meters). They had a crest on the back their head and long toothless jaws, and they once soared over the seas of Kansas. The biggest of the pterosaurs was the enormous Texas pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus, which was the size of a small airplane (fig. 19.13E).

Figure 19.13 ▲

Pterosaurs were flying archosaurs closely related to dinosaurs but not members of the Dinosauria. (A) The robin-sized Pterodactylus from the Jurassic Solnhofen Limestone. (B) The vane-tailed Rhamphorhynchus from the Solnhofen. (C) A nearly complete skeleton of Pteranodon, showing their huge size. (D) The huge toothless crested Pteranodon sailed over the Cretaceous seas of Kansas. (E) The largest pterosaurs of all were azhdarchids, such as this giant Texas pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus, which was the size of a small airplane. ([A–D] Photographs by the author; [E] courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Dinosaurs are the most popular of all extinct prehistoric creatures, and people have read and heard lots of things about them. However, not every extinct animal is a dinosaur. Many books and packages of plastic toy dinosaurs include animals that are not dinosaurs. For example, saber-toothed cats and mammoths are mammals, not dinosaurs. Pterosaurs are closely related to dinosaurs, but they were not members of Dinosauria, so calling them “flying dinosaurs” is incorrect. Plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs and other marine reptiles are not dinosaurs—in fact, there were no marine dinosaurs. The fin-backed creature called Dimetrodon is related to mammals, and it is not even a reptile. Being extinct or prehistoric does not make something a dinosaur.

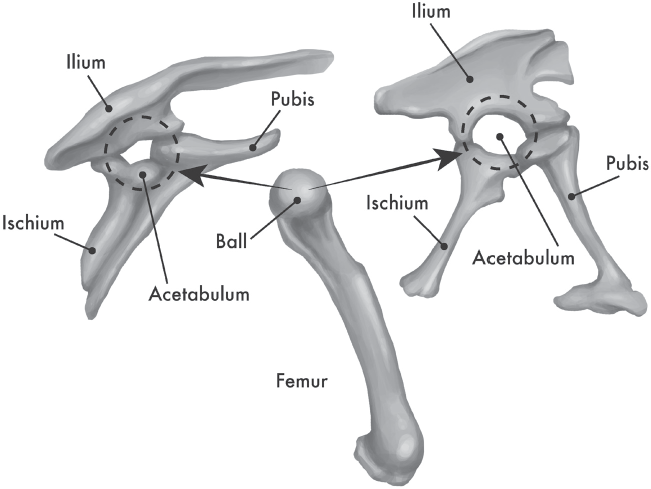

So what makes a dinosaur? Dinosaurs are defined by a very specific set of anatomical features. For example, only dinosaurs have a hip joint that is an open hole and not an enclosed socket like ours (fig. 19.14). Their limbs are held completely vertical beneath their bodies, so the head of the thighbone has a right-angle bend where it inserts into the hip socket. They also walked on the tips of their toes, not on the palms of their hands or soles of their feet. In their hind legs, the joint between the leg bones and the foot occurs not between the shinbone and the first row of ankle bones (as in most vertebrates) but between the first and second row of ankle bones. When you eat the drumstick of a chicken or turkey, the cap of cartilage on the end is actually the first row of ankle bones. In dinosaurs, this first row of ankle bones also has a spur of bone that runs up the front of the shinbone. These and many more unique anatomical features are what make a creature a dinosaur.

Figure 19.14 ▲

The Dinosauria are defined by having an open hole through their hip socket, into which the ball joint of the thighbone (femur) fits. The two major groups are the Saurischia (right), where the pubis points forward only, and the Ornithischia (left), where part or all of the pubis runs backward parallel to the ischium. (Illustration by Mary Persis Williams)

The earliest dinosaurs were turkey-sized bipedal runners like Eoraptor and Herrerasaurus from the Late Triassic of Argentina (fig. 19.15). Soon their descendants split into two main branches: the Saurischia, or “lizard-hipped” dinosaurs, and the Ornithischia, or “bird-hipped” dinosaurs (see fig. 19.14). The Saurischia include two main groups, the long-necked long-tailed huge sauropods, such as “Brontosaurus” and Brachiosaurus, and the predatory theropod dinosaurs (fig. 19.16A–D). Their hip bones have the primitive lizard-like configuration, with the pubic bone in front of the hip socket pointing forward and down.

Figure 19.15 ▲

The most primitive dinosaurs were small, fast-running bipedal predators like Herrerasaurus (the larger one) and Eoraptor (the smaller one), from the Late Triassic of Argentina. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Figure 19.16 ▲

Typical saurischian dinosaurs. (A) The small Late Triassic theropod Coelophysis. (B) Tyrannosaurus rex, the largest land predator in North America. (C) The dinosaur called “Velociraptor” in the Jurassic Park movies is actually Deinonychus; true Velociraptor was the size of a turkey. (D; color figure 12) The giant brachiosaur sauropod Giraffatitan, on display in Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin. ([A–C] Photographs by the author; [D] courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

In the Ornithischia, on the other hand, at least part of the pubic bone points backward. Ornithischians are entirely herbivorous dinosaurs, including duckbills, iguanodonts, stegosaurs, the armored ankylosaurs, the thick-headed pachycephalosaurs, and the horned and frilled ceratopsians (fig. 19.17A–D).

Figure 19.17 ▲

Typical ornithischian dinosaurs. (A) The most common and diverse ornithischians were duck-bill dinosaurs; this is Edmontosaurus. (B) The turtle-like armored ankylosaurs came in a variety of sizes and shapes; this one is Gargoylesaurus. (C) Stegosaurs had armored plates along their spine, tiny heads, and four spikes on their tails. (D) Triceratops and the ceratopsians had frills on the back of their neck and different combinations of horns. (Photographs by the author)

In addition to a better understanding of how dinosaurs are interrelated and how they evolved, we also understand their biology much better. Numerous discoveries of feathers in nonbird dinosaurs have demonstrated that down feathers and body feathers occurred in every branch of the dinosaurs. If you see dinosaurs reconstructed without feathers (as in the Jurassic Park/Jurassic World movie), it is grossly out of date.

Much of what the public thinks about dinosaurs comes from movies and TV shows, but we must keep in mind that how dinosaurs behaved or what they sounded like or what color they were is mostly guesswork. In most cases, we have only the bones, which don’t tell us much about the colors of dinosaurs or how they acted. In a few cases, feathered dinosaurs were preserved with their pigment cells, so we can tell what colors they were, but for most dinosaurs we simply don’t know. The sounds of dinosaurs are pure guesswork, although a few dinosaurs, such as Parasaurolophus, had crests that might have produced a hooting or honking sound. Dinosaur behavior is even harder to determine scientifically. A few trackways have been discovered that show how fast dinosaurs could move and prove that they did not drag their tails but carried them straight out behind them. Dinosaur fossils occasionally show damage from combat between individuals, or tooth marks showing a predator or scavenger eating a carcass. However, the popular scenario of Triceratops fighting a Tyrannosaurus rex is still not proven to have happened (fig. 19.18). These two dinosaurs did live at the same place and time, so they probably did fight. But we have yet to find any T. rex bite marks on a Triceratops indicative of a battle, although bite marks on the body of Triceratops do suggest that they have been scavenged.

Figure 19.18 ▲

The skeletons of Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops, posed for battle. (Photograph by the author)

In addition, there has long been a controversy about dinosaur physiology. Since the 1970s, a number of paleontologists have argued that dinosaurs were “warm blooded.” In other words, like birds and mammals, dinosaurs had endothermy, or body heat generated by their internal metabolism rather than from the environment. Since the late 1970s, most of the evidence for endothermy in all dinosaurs has been shown to be ambiguous or inconclusive. Most paleontologists now agree that the smaller dinosaurs and pterosaurs were very active animals that ran and flew, so they probably were endothermic. These animals have a large surface area relative to their small volume, and they would lose heat at a very rapid rate unless they had some kind of insulating covering, such as fur or feathers.

The largest dinosaurs have the opposite problem. As body size increases, the surface area increases only as a square, but the volume increases as a cube. So large animals have too small a surface area for their volume. For example, large living terrestrial animals (such as elephants) have a problem getting rid of heat. Elephants manage by flapping their ears (which are full of blood vessels and are primarily used for dumping heat) and by bathing frequently. Camels can allow their body temperature to fluctuate throughout the day. They are cold in the morning, take a long time to warm up in the desert, and then slowly cool down at night. This kind of thermal inertia means that large dinosaurs probably had a constant body temperature by virtue of their body size alone (inertial homeothermy or gigantothermy). They would not have needed any special regulatory mechanism or internal source of heat in the warm climates of the Mesozoic. Indeed, if they had been endothermic, they would have had problems getting rid of their excess body heat.

Dinosaur fossils are glamorous and are the highlights of exhibits for many museums today, but they are not easy to collect or to possess. Most dinosaur fossils are found on public land, and you need the proper permits to collect these fossils. Government land management agencies need to know that you are qualified to do the collecting properly before a permit is granted. Fossils are also found on private ranch land, and you need the permission of the owner to collect on this land. Poaching dinosaur fossils and selling them for obscenely high prices has become an issue today, and many ranchers are unwilling to let collectors on their land without receiving a large payment up front.

Fragmentary scraps of dinosaur bone can be found quite easily or bought on the commercial market because they have little scientific value. If you prospect long enough in some of the classic dinosaur beds of the Rocky Mountains, you will find them (along with lots of turtle shell fragments, crocodile teeth, and other scraps). Some of these classic dinosaur beds include the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming; the Lower Cretaceous beds of the Kaiparowits Plateau of southern Utah; the Lance Creek beds near Hat Creek in eastern Wyoming; or the Hell Creek beds near Jordan, Montana. But finding and properly collecting more complete dinosaur remains should be undertaken by professionals and specialists who know how to get them out of the ground in a plaster jacket without destroying them, how to transport and prepare them, and who know how to place them in a proper scientific institution for study. A number of “summer paleontology camps” that advertise online can provide you with this experience without the expense and difficulty of transporting and storing dinosaur fossils.

CLASS AVES: BIRDS

Birds are among the most popular of all wildlife to study, and many people own birds as pets or for a hobby. Today there are over 10,000 known species of birds. Despite their great diversity, their fossil record is relatively poor because birds have delicate hollow bones that are easily broken. Forty-seven of the 155 living families of birds have no fossil record, and most of these 47 living families are known only from the Pleistocene. Most fossil birds are known from fragments of a few key bones. Complete articulated specimens have been found preserved at a only handful of extraordinary localities, such as the Cretaceous beds of Liaoning Province in China or the Eocene Messel lake beds of Germany. Bird fossils are also commonly found in extraordinary deposits such as La Brea tar pits, although the fossils are all jumbled and disarticulated and no two bones can be reliably associated. Bird fossils are not easily collected or owned, and most people have to be content with viewing specimens on display in museums.

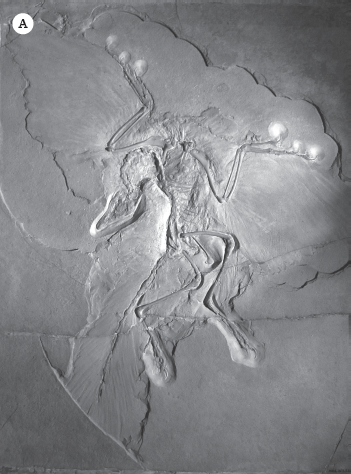

One of the first bird fossils ever found was the extraordinary discovery of Archaeopteryx in the Upper Jurassic Solnhofen Limestone of Germany in 1861 (fig. 19.19A), just two years after Darwin predicted such discoveries in his book On the Origin of Species. Archaeopteryx is an ideal transitional fossil showing how birds evolved from their dinosaurian ancestors, especially dromaeosaur theropod dinosaurs such as Velociraptor and Deinonychus. Even though it had feathers, in almost every other respect Archaeopteryx had a primitive dinosaurian skeleton. It had a dinosaurian skull with peg-like teeth in the jaw (all living birds have a toothless beak), long bony fingers capable of grasping (the hand of living birds is fused into a single bone that supports the shafts of the wing feathers), a long bony tail (living birds have a short bony tail and feather shafts support their tail feathers), wrist bones identical to those found in Velociraptor, and the characteristic ankle joint found only in dinosaurs and pterosaurs. In fact, one specimen with faint feather impressions was mistaken for the small dinosaur called Compsognathus.

Figure 19.19 ▲

Some remarkable fossil birds. (A) The best of the 12 known specimens of Archaeopteryx from the Upper Jurassic Solnhofen Limestone, now on display in the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin. (B) The gigantic flightless moas from New Zealand died out just a few hundred years ago when the Maoris hunted them to extinction. This is Sir Richard Owen, who first described the biggest of the moas, Dinornis. (C) The half-ton “elephant birds” of Madagascar also vanished when humans hunted them to extinction. (D) In the Eocene of North America (Diatryma) and Europe (Gastornis), enormous predatory birds hunted the much smaller mammals. (E) The absence of large mammal predators in South America during the Cenozoic allowed giant predator birds called phorusrhacids to evolve. (F) The enormous Argentavis compared to the largest living flying bird, the Andean condor. ([A–C, E] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [D] photograph by the author; [F] courtesy of N. Tamura)

Since the discovery of Archaeopteryx, many more Mesozoic bird fossils have been found, especially in the Cretaceous deposits of China where they are complete with feather impressions and even their original color. These fossils show the various steps in evolution from birds like dinosaurs to birds with modern features. One group, the Enantiornithes (“opposite birds” in Greek), occupied most of the smaller bird niches in the Cretaceous, but they were extinct by the end of the Mesozoic. Another group, the ornithurines, were related to living birds, but they were overshadowed by the enantiornithines. These included a number of larger mostly marine birds of the Cretaceous, such as the shorebird Gansus from China, plus toothed birds from the western Kansas chalk beds, such the loon-like Hesperornis and the tern-like Ichthyornis. Most of these Mesozoic lineages vanished before the Cretaceous extinctions, leaving only the living branches of birds (Neornithes) to radiate and evolve rapidly in the early Cenozoic.

One of the most primitive living branches of birds are the flightless ratite birds, such as the ostrich of Africa, the rhea of South America, the emu and cassowary of Australia, and the kiwi of New Zealand. In addition, even larger ratites existed, such as the huge flightless moas of New Zealand that were up to 12 feet (3.7 meters) tall; they vanished only 400 years ago when Maoris hunted them to extinction (fig. 19.19B). Madagascar had the largest bird ever found, the “elephant bird” Aepyornis (fig. 19.19C), which weighed about 1,000 pounds (450 kilograms) and laid an egg almost a foot long that had a two-gallon capacity.

The rest of the modern birds (neognath birds) include the bulk of the 10,000 species and 54 families alive today. Among these lineages, there have been some surprising developments. After the large predatory dinosaurs vanished during the great Cretaceous extinction event, there were no large mammalian predators until the middle Eocene, about 40 million years ago. Into this void gigantic predatory birds evolved to reestablish the dinosaurian dominance over mammals. During the early Eocene, North America had Diatryma and Europe had Gastornis, both huge 7-foot-tall (2 meters) carnivorous flightless birds with sharp robust beaks for ripping apart smaller mammalian prey (fig. 19.19D). Likewise, for most of its Cenozoic history, South America had no large predatory mammals other than wolf-sized marsupials. Instead, the dinosaurs ruled the world again with huge 7- to 9.8-foot-tall (2 to 3 meters) predatory birds known as phorusrhacids that had long robust legs and sharp hooked beaks (fig. 19.19E).

Flying birds cannot grow as large as flightless ground birds because they must keep their bones and bodies light enough to fly. Nevertheless, there were some amazing examples of huge flying birds. The largest yet known was the condor-like Argentavis from the Miocene of Argentina (fig. 19.19F). It had a wingspan of 23 feet (7 meters) and weighed about 150 pounds (72 kilograms). It probably soared on the thermal updrafts along the Andes looking for food and carrion just as modern eagles and vultures and condors do. A huge seabird, Pelagornis, was found in the Oligocene beds excavated during the construction of the airport in Charleston, South Carolina. It had a similar wingspan, possibly as long as 24 feet (7.4 meters), but the long narrow wings of an albatross, and it probably only weighed about 88 pounds (40 kilograms).

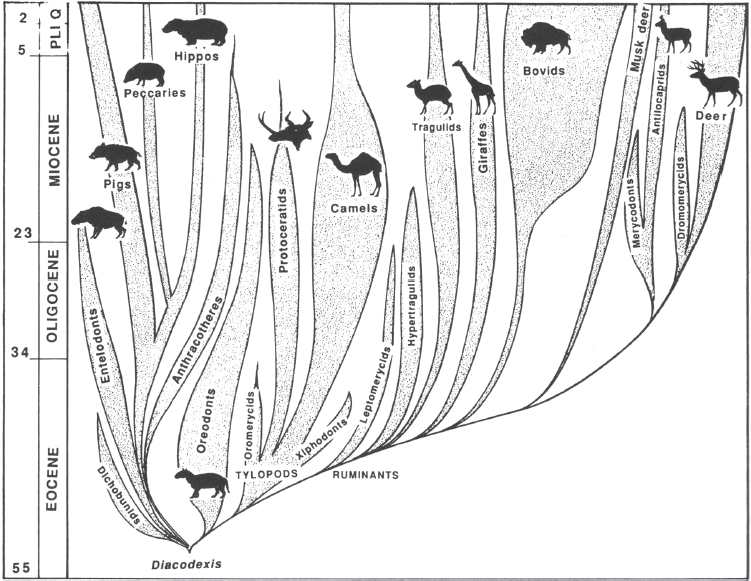

CLASS MAMMALIA: MAMMALS

With about 5,400 living species, mammals are not as diverse as birds (10,000 living species) or bony fish (30,000 species) or insects (millions of species). People sometimes call the last 65 million years the Age of Mammals, but mammals are not the most numerous creatures during that time. Nevertheless, mammals have been the dominant medium and large animals on Earth ever since the extinction of the nonbird dinosaurs 65 million years ago. They include huge beasts like the elephant and the blue whale (the largest animal that ever lived), as well extinct gigantic mammoths and immense hornless rhinoceroses, and many extinct whales. Mammals have also taken over nearly all the important roles on land, from large herbivores to nearly all the predatory niches, to arboreal and digging roles, to ant-eating habitats. Independently of birds and insects, some mammals evolved flight (bats). Mammals (whales, seals, and sea lions) also became the dominant predators in the marine realm. Not only did mammals dominate the large animal niches, but they got small too. Although not as small as insects, the most diverse mammals are the tiny ones, especially rodents, rabbits, and insectivores. Some mammals are truly tiny, especially those that prey on insects. The living Etruscan shrew weighs only 0.07 ounces (2 grams) and is barely over an inch (2.5 centimeters) long. The smallest mammal known was the extinct Batonoides vanhouteni from the early Eocene (53 million years ago) of Wyoming. It weighed only 0.05 ounces (1.3 grams) and was about the size of an eraser on the tip of a pencil.

Living mammals are defined by a large number of features. For example, all living mammals have some kind of hair or fur on their bodies for insulation, even though some (like elephants and rhinoceroses) have lost most of it. All living mammals (except the platypus and echidna) no longer lay eggs but give live birth to their young, and all mammal females have mammary glands to nurse their young once they are born. All mammals are “warm blooded,” or endothermic, using the energy of their food to keep their body temperature warm and relatively constant. They have a four-chambered heart, a diaphragm for pumping air in and out of the lungs, and the most sophisticated and largest brains of the entire animal kingdom, which is equipped with an expanded neocortex. Some mammals (such as humans, apes, elephants, and dolphins) have very complex behaviors as well.

Unfortunately, most of these characteristics are seen as behaviors or occur in soft tissue that does not fossilize well. To trace the origin of mammals in the fossil record, we look for a series of features in the skeletons of the fossils that show the transition from primitive reptile-like creatures (such the middle ear bones, the jaw hinge, the secondary palate in the mouth, specialized teeth, and many others) to true mammals.

These ancestors have long been called “mammal-like reptiles,” but that term is inappropriate because these creatures have nothing to do with the lineage that leads to reptiles. Instead, they should be called “protomammals” or their proper name, Synapsida (fig. 19.20). The earliest synapsids (Protoclepsydrops and Archaeothyris) and true reptiles (Westlothiana) originated side by side in the Early Carboniferous as separate lineages, so at no time were synapsids ever “reptiles.”

Figure 19.20 ▲

Reconstructions of some protomammals or synapsids (formerly but incorrectly called “mammal-like reptiles”). On the right in the background is the finbacked predatory “pelycosaur” Dimetrodon, and on the left is the finbacked herbivorous “pelycosaur” Edaphosaurus. In front on the left is the huge predatory “therapsid” gorgonopsian Gorgonops, and behind it is the herbivorous “therapsid” dinocephalian Moschops. Behind the human is the dinocephalian Estemnosuchus, with the bizarre crests and tusks on its face. In the right front are the wolf-sized predatory cynodont Cynognathus and the cow-sized herbivorous dicynodont “therapsid” Kannemeyeria, with a toothless beak except for canine tusks. (Illustration by Mary Persis Williams)

After the small Carboniferous lizard-like synapsids such as Protoclepsydrops and Archaeothyris, the first great radiation of protomammals occurred in the Early Permian with the familiar “fin-backed” creatures like Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus, originally placed in the wastebasket group “pelycosaurs” (fig. 19.21A–B). These fossils are common in the Lower Permian beds around Seymour, Texas, and are still collected today. The tiger-sized Dimetrodon was the largest land predator the world had seen up to that time. Pelycosaurs vanished in the Late Permian, replaced by an even bigger evolutionary diversification of more advanced synapsids. These included large herbivores like the pig-sized dinocephalians, with thick skulls and weird bumps on their head, and the beaked dicynodonts, as well as bear-sized predators with huge fangs like the fearsome gorgonopsians (fig. 19.21C–D). Most Late Permian protomammals vanished in the great Permian extinction, but several lineages survived, and during the Triassic they evolved into even more mammal-like creatures that had most of the mammalian features of the skeleton (fig. 19.22). Some, such as Thrinaxodon, have bony features and may have had hair and a diaphragm. By the Late Triassic, these advanced protomammals were very similar to true mammals, and it is difficult to decide where the protomammals end and true mammals begin.

Figure 19.21 ▲

(A) The earliest synapsids or “pelycosaurs” included the finbacked Dimetrodon, the dominant predator of the Lower Permian red beds of northern Texas. (B) Fossils of Dimetrodon, attacking the contemporary temnospondyl Eryops. (C) Reconstruction of the gorgonopsians, huge predators of the Late Permian. (D) Skeleton of the huge Late Permian gorgonopsian Gorgonops. (Photographs by the author)

Figure 19.22 ▲

Evolution of the synapsids, from the primitive “pelycosaurs” of the Early Permian, to the “therapsids” of the Late Permian, and finally to the advanced cynodonts and mammals of the Early Triassic. (Redrawn from several sources by Mary Persis Williams)

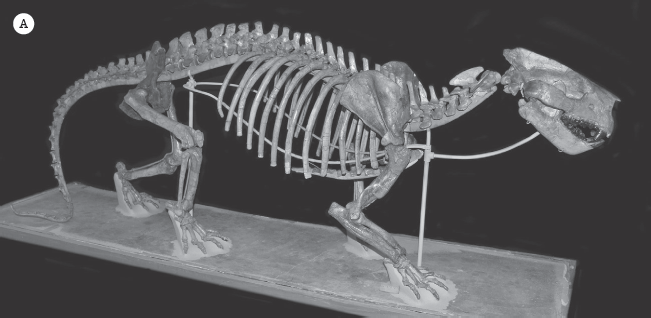

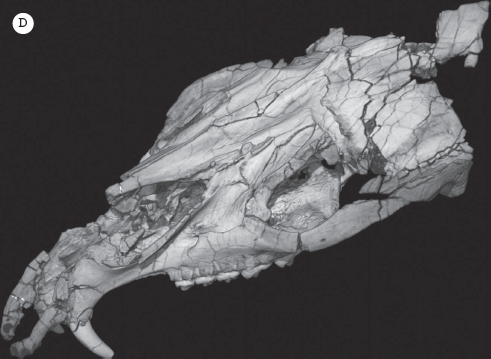

There are several shrew-sized Late Triassic fossils that almost all paleontologists regard as true mammals because they had the mammalian jaw joint and middle ear bones, and their skeletons had all the other advances seen in mammals. From the Triassic through the rest of the Mesozoic (over 130 million years, twice as long as the Cenozoic Age of Mammals), mammals evolved and diversified rapidly in a world dominated by dinosaurs (which also originated in the Late Triassic). They remained small (mostly rat-sized or smaller) and probably hid in the undergrowth and came out mostly at night to escape being eaten by their dinosaurian overlords (fig. 19.23). If not for the great Cretaceous extinction event that wiped out the nonbird dinosaurs, mammals would still be tiny and hiding from dinosaurs, and we would not be here.

Figure 19.23 ▲

Skeleton of the larger Mesozoic mammal Gobiconodon, about the size of cat. Most Mesozoic mammals were the size of a shrew or mouse. (Photograph by the author)

At the dawn of the Cenozoic Age of Mammals, mammals inherited a planet with no larger creatures ruling over them. During the next 15 million years, they underwent a huge evolutionary radiation from a handful of shrew-sized creatures to many different lineages. By the middle Eocene (about 47 million years ago), not only were some of them almost the size of elephants, but early bats were also flying in the skies, primitive whales lived in the oceans, and there were large predators the size of wolves, a wide spectrum of primates in the trees, as well as primitive anteaters and many kinds of burrowing mammals (fig. 19.24A–G).

Figure 19.24 ▲

A spectrum of different mammalian groups that had evolved by the middle Eocene, about 45 million years ago. (A) The lemur-like primate Notharctus. (B; color figure 13) The elephant-sized horned and tusked uintatheres Eobasileus. (C) The transitional whale Ambulocetus, the “walking swimming whale,” which still had four limbs with webbed feet. (D) The primitive rhino-like group known as brontotheres. (E) The earliest elephant relatives were pig-like forms called Moeritherium. (F) Two of the earliest bat fossils, Icaronycteris and Onychonycteris. (G) One of the earliest horses, Protorohippus. (Photographs by the author)

This great evolutionary radiation of Cenozoic mammals produced three main groups that are still alive today. One branch, the monotremes, includes the living platypus plus the echidnas, or “spiny anteaters,” of Australia and New Guinea. These are the only mammals that still lay eggs. The females do not have nipples but they do have mammary glands to nurse their young when they hatch, so the babies must lap up the milk from the mother’s fur.

The second main branch of mammals are the marsupials, or the “pouched mammals,” including opossums, kangaroos, wallabies, koalas, wombats, and many more species (fig. 19.25). Marsupials give live birth to their young, but the newborns are born prematurely as tiny bee-sized creatures with only a functional mouth and front limbs. Once they are born, they must crawl up the belly fur and crawl into their mother’s pouch, where they clamp onto a nipple and finish their development until they can get around on their own.

Figure 19.25 ▲

A spectrum of extinct marsupials. In the foreground is the wolf-like sparassodont Borhyaena. In the extreme right foreground is the saber-toothed sparassodont Thylacosmilus. In the center foreground is the “marsupial lion” Thylacoleo. The giant short-faced kangaroo is Procoptodon. The huge creature behind the human is Diprotodon. The sloth-like creature with the proboscis in the left background is Palorchestes. (Illustration by Mary Persis Williams)

Opossums and similar marsupials have long been successful in the Northern Hemisphere, but their greatest evolutionary success was in the southern continents of Australia and South America. Australia has had a long fossil history of marsupials, including some gigantic kangaroos twice as large as the living species and wombats the size of rhinos. Today nearly all the native mammals of Australia are familiar marsupials such as kangaroos, wallabies, koalas, wombats, and their kin, although many are being driven to extinction by competition from invading mammals (dingoes, rats, rabbits, sheep, goats, cattle) brought by humans and by human destruction of their habitat. Marsupials also dominated South America during most of the Cenozoic when it was an “island continent” isolated from mammals evolving in the rest of the world. Nearly all the large predators of South America were marsupials, including some that looked much like wolves or hyenas, and one pouched predator that was a good mimic of a saber-toothed cat (see fig. 19.25).

But the most diverse groups of mammals since the early Cenozoic are the placental mammals. Unlike marsupials, placental females carry their young to term inside their bodies, so they can be born almost fully functional. Some, like baby zebras or antelopes, must be able to stand and run with the herd within minutes of being born, or predators will get them. Others, like humans, are born relatively defenseless, but at least all of our organs are fully developed and functional even if the baby is not able to do much on its own at first.

I cannot review all 20-plus orders of fossil mammals, which are composed of many hundreds of genera (living and extinct) and thousands of species. Instead, I will focus on a few groups that the collector is likely to encounter in the field. Unlike other vertebrates, for which we must collect most of the skeleton in order to identify and understand them, fossil mammals can usually be recognized and identified by their teeth alone. Teeth are the most durable part of the vertebrate skeleton and have a dense covering of hard enamel that allows the tooth to survive being bashed around in the currents of rivers or the ocean. Unlike the simple peg-like teeth of most reptiles or amphibians (or the toothless birds), mammal teeth are highly specialized. The shape and crown pattern and cusps of the molars and premolars of the cheek teeth, in particular, are highly diagnostic not only of what animal the teeth came from but even what kind of food the animal ate, how old the individual was at the time of death, and what the environmental conditions were like when the mammal lived. A high percentage of mammal species are known only from their teeth and jaws and no other part of the skeleton. I will introduce a few of the better known or commonly collected North American fossil mammals and explain how they are fossilized and identified, including the features of their tooth crowns.

XENARTHRANS: SLOTHS, ARMADILLOS, AND ANTEATERS

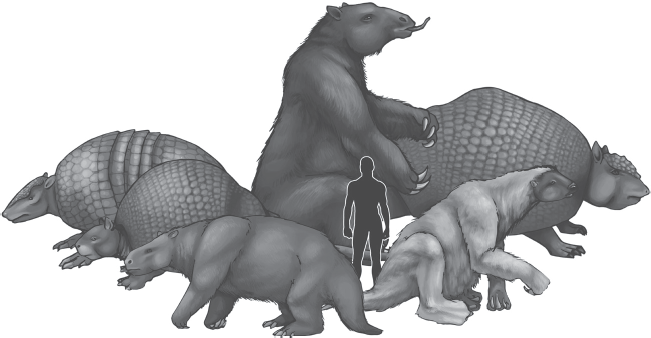

The xenarthrans (formerly called the “edentates” or “toothless ones”) are familiar to us from the living sloths, anteaters, and armadillos (fig. 19.26). They are exceptions to the rule about recognizing mammals by their teeth; sloths and armadillos have simple peg-like teeth with no enamel coating, and anteaters are completely toothless. Xenarthrans are the most primitive group of living placental mammals, branching off during the Mesozoic before most of the other groups. They became isolated in South America and underwent most of their evolution there, before they began to cross Central America to North America in the late Miocene. At that point, huge ground sloths invaded North America, and they left their bones in many places. The biggest were elephant-sized ground sloths in South America that were 20 feet (6 meters) tall and weighed 3 tonnes. North America also had huge sloths that were only slightly smaller. The two living species of tree sloth found in Central and South America are remnants of a huge ground sloth radiation that have shrunk down in size. Each evolved from a different family of ground sloths, so the two-toed sloth is not that closely related to the three-toed sloth.

Figure. 19.26 ▲

Examples of some of the extinct giant xenarthrans. The gigantic sloth (middle) is Megatherium; the sloth (right front) is Megalonyx, and the sloth (left front) is Mylodon. The armored creature (middle left) with the spiky tail is Doedicurus, and the giant armadillo relatives in the back are Glyptodon (right) and Holmesina (left). (Illustration by Mary Persis Williams)

The other major group of xenarthrans are the armadillos (which are still common in the desert Southwest of the United States) and their extinct relatives, the glyptodonts. Glyptodonts and the very similar pampatheres looked like armadillos but were the size of a Smart car, with a domed shell over 6 feet (2 meters) long, and weighing up to 2 tonnes. Some had a spiked tail club, and others had only armor on their tail and over their head. Although complete glyptodonts are rare, the individual pieces of their body armor are easily fossilized and quite often found in Pliocene and Pleistocene fossil beds all over the Americas.

PROBOSCIDEA: MASTODONTS AND MAMMOTHS

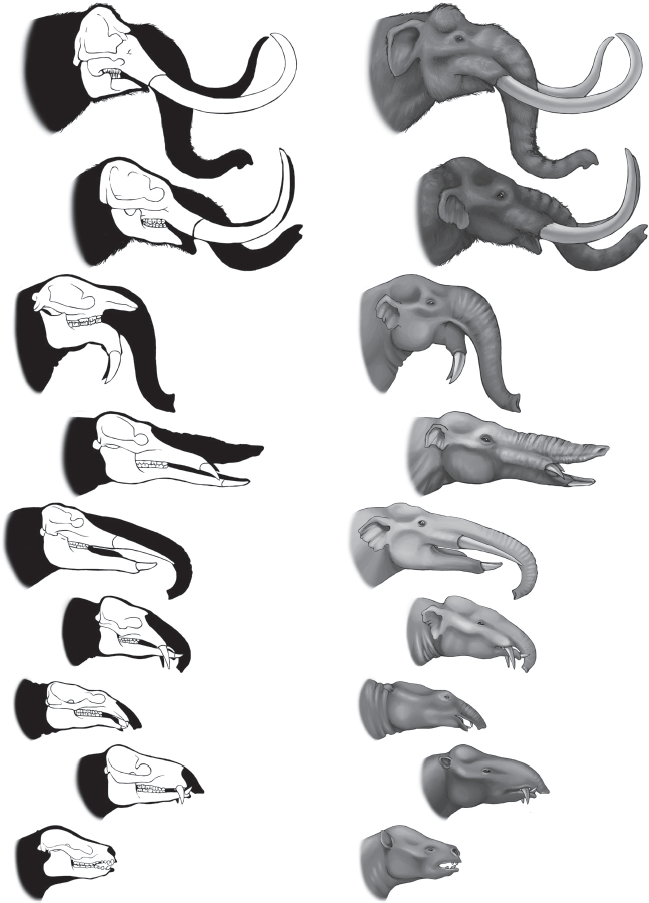

The mastodonts and their ancestors originated in the Paleocene of Africa; they were pig-sized beasts that had only the beginnings of tusks and possibly a short proboscis (fig. 19.27; see also fig. 19.24E). In the early Miocene (about 19 million years ago), they escaped Africa, quickly spreading across Eurasia, and finally across the Bering land bridge to North America. Most important Miocene and Pliocene mammal localities will yield mastodont fossils or fragmentary bone scraps because their bones are large and durable. The majority of the Miocene proboscideans are known as gomphotheres; they had long narrow jaws and straight upper and lower tusks protruding from their jaws. There were also shovel-tusked mastodonts, whose lower tusks were merged into a broad scoop or shovel-like shape. By the Pliocene, more specialized proboscideans appeared in Eurasia and Africa, and some migrated to the Americas. The most familiar of these are the mammoths, which looked much like modern elephants except they tended to be bigger and their tusks had a long inward curve. Numerous species of mammoth roamed North America during the Pleistocene, including the smaller woolly mammoth in the polar regions, and the much larger (but not hairy) imperial mammoth, found in most southern Pleistocene localities, such as at La Brea tar pits.

Figure 19.27 ▲

The evolution of proboscidean skulls from the Eocene to the Pleistocene. At the bottom is Phosphatherium, followed (bottom to top) by Numidotherium, Moeritheriun, Palaeomastodon, Phiomia, Gomphotherium, Deinotherium, Mammut (American mastodon), and at the top, Mammuthus, the mammoth. (Illustration by Mary Persis Williams)

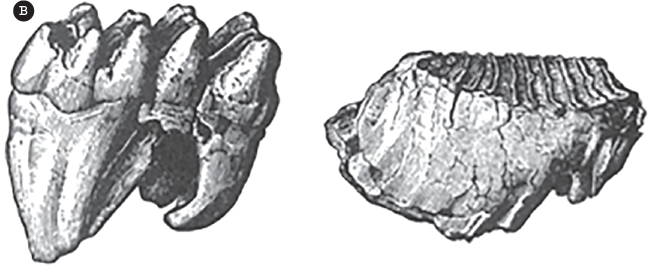

Proboscideans are easily recognized from their teeth alone. Like their close relatives the manatees and other sea cows, proboscideans have what is known as horizontal tooth replacement. Instead of the adult teeth pushing out the baby teeth from below (as in most mammals), the new teeth erupted from the back of the jaw and pushed the old worn teeth off the front (fig. 19.28A). Mastodonts have very distinctive large molars with multiple rounded conical cusps, which occasionally are joined together to form cross-crests (fig. 19.28B). Elephants and mammoths, on the other hand, had huge molars made of tightly folded ridges of enamel and dentin, which wore down to form a ridged grinding surface. Each molar was so large, and the jaw was so short, that an elephant or mammoth had only one tooth (or maybe two) on each side of its upper and lower jaws at any given time. These teeth are easily recognized and identifiable, even when they are broken and no longer attached to the jaw.

Figure 19.28 ▲

All proboscideans have horizontal tooth replacement. One enormous molar on each side of the jaw (and on the upper jaw as well) is in use at a time, and it is pushed forward and breaks off the front as it wears down, only to be replaced by another tooth behind it. (A) Top view of a mammoth jaw, showing one molar tooth in occlusion, and another unworn tooth behind it in the crypt in the back of the jaw. (B) The differences between a mastodon molar (left) with the low rounded cusps, and a mammoth or elephant molar, a solid grinding tooth made of thick bands of enamel separated by softer dentin, creating a grinding surface. ([A] Photograph by author; [B] courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

CARNIVORES: DOGS, CATS, BEARS, AND THEIR RELATIVES

Preying upon other mammals is the order Carnivora, the flesh-eating mammals (fig. 19.29). Today they include dogs, cats, bears, weasels, skunks, raccoons, hyenas, civets, and mongoose, as well as seals, sea lions, and walruses. Most meat-eating mammals have distinctive jaws and teeth, with long sharp canines, for stabbing and tearing into their prey, and cheek teeth that are shaped like slicing blades, for cutting the meat up before they swallow it.

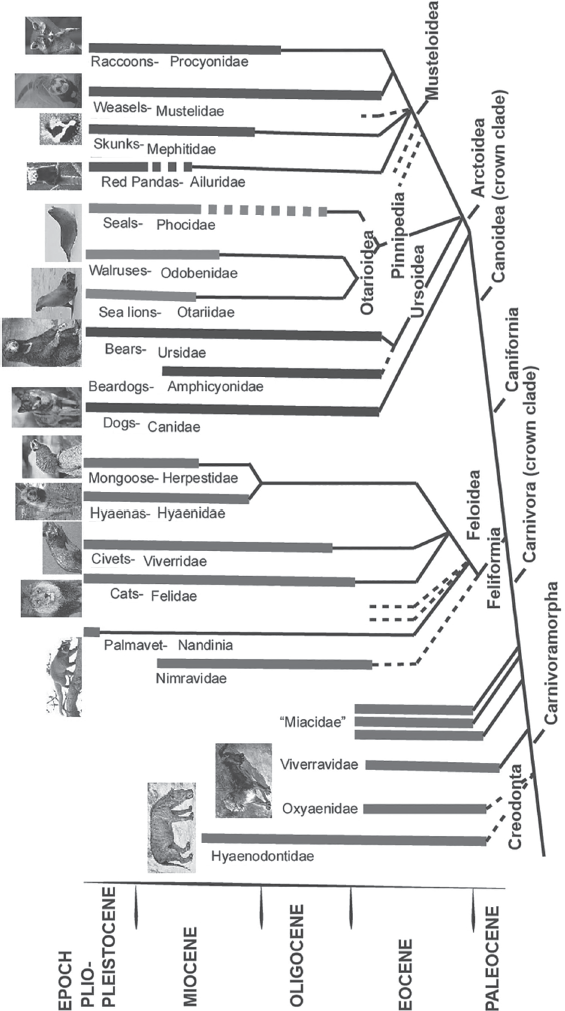

Figure 19.29 ▲

Family tree of the creodonts and carnivorans. (Redrawn from several sources by Mary Persis Williams)

The earliest predators were an extinct group known as creodonts (fig. 19.30A–B), which had a much more primitive combination of teeth, small brains, robust limbs, and were mostly wolf-sized to lion-sized ambush predators. Creodonts were the dominant predators in Paleocene and Eocene beds, but by the middle and late Eocene, members of the living order Carnivora had appeared and began to crowd them out. The earliest dogs from the late Eocene (Hesperocyon) looked more like weasels, and the dog family went through an extensive evolutionary history in North America, with one branch developing hyena-like crushing jaws and teeth for breaking bones and scavenging. Living alongside them in the late Eocene and Oligocene were cat-like creatures known as nimravids, or “false cats” (fig. 19.30C). Although their skulls and teeth are extraordinarily cat-like (like Dinictis), with some even developing saber-like teeth (Hoplophoneus, Nimravus, and Eusmilus), the details of their skull region show that they were not true cats at all, and they even may be more closely related to dogs. Whatever their relationships, they represent a truly extraordinary example of evolutionary convergence. When the nimravids vanished from North America around 26 million years ago, there were no cat-like creatures to replace them. This resulted in a “cat gap,” a total absence of cat-like predators in North America for 7.5 million years in the late Oligocene and early Miocene, until true cats arrived from Eurasia about 18.5 million years ago (fig. 19.30D).

Figure 19.30 ▲

Some examples of extinct carnivorans. (A) The jaguar-sized creodont Patriofelis, one of the earliest large mammalian predators. (B) One of the last of creodonts, the wolf-like Hyaenodon, common from the Eocene through the Miocene around the world. (C) The “false saber-tooth cat” or nimravid Hoplophoneus from the Eocene and Oligocene. (D) The true saber-tooth cat, Smilodon. (E) The bone-crushing borophagine dog, Epicyon. (F) The enormous bear dog Amphicyon. (G; color figure 14) The short-faced bear, one of the largest land predators that ever lived; it is bigger than any living bear. ([A–B] Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; [C–G] photographs by the author)

By the early Miocene, a variety of primitive weasel, bear, and raccoon relatives had evolved, often migrating back and forth between North America and Eurasia across the Bering land bridge. The dog family, on the other hand, remained largely confined to North America until later in their evolution. They spread to South America about 4 million years ago to become the ancestors of the South American dog radiation (including bush dogs and maned wolves), and they spread to Eurasia as well. In North America, one dog family, the borophagines, evolved extremely powerful skulls with bone-crushing teeth and performed the role of predator-scavengers that hyenas occupied in the Old World (fig. 19.30E).

Another important group were the extinct amphicyonids, nicknamed the “bear dogs.” They are distantly related to both bears and dogs but are not members of either living group. Some, like Amphicyon (fig. 19.30F), were gigantic wolf-like predators larger than the largest bear. By the late Miocene, all the archaic predators such as bear dogs and creodonts were completely extinct. Most of the predatory ecological niches were filled by cats, dogs, bears, and their relatives. During the Ice Ages, North America was home to some extraordinary predators, including saber-toothed cats, giant short-faced bears bigger than the largest living bears (fig. 19.30G), huge lion-like cats bigger than any lion, and many different kinds of dogs, including the fearsome dire wolves, which are the most common fossil at places like La Brea tar pits.

ORDER PERISSODACTYLA: ODD-TOED HOOFED MAMMALS

Today, only five species of tapirs, five species of rhinos, and seven species of wild horses, asses, and zebras (fig. 19.31) survive on Earth, but through much of geologic history these were the dominant large hoofed mammals not only in Africa and Eurasia but especially in North America (where none of them are native today). They are members of the order Perissodactyla, or the odd-toed hoofed mammals. They get this name because their hands and feet have only one (horses) or three (rhinos and tapirs) fingers and toes, and the axis of symmetry runs through the middle finger and toe.

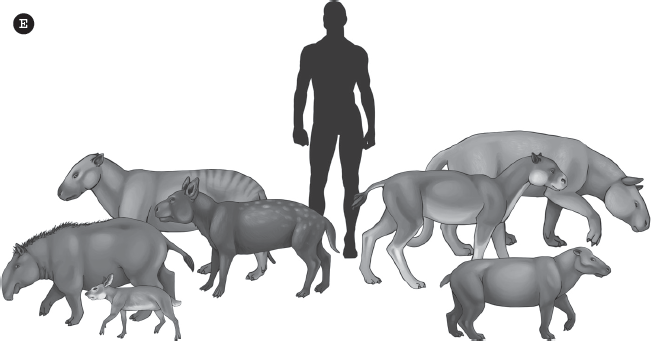

Figure 19.31 ▲

The evolution of horses. Horses began as collie-sized creatures with four fingers on their hands and three toes on their feet (Protorohippus), but by the Oligocene they had become larger and used only three toes. All of these horses ate leaves and other browse (lower branches with leaves in background), as did their descendants, the anchitherine horses (fourth branch from bottom to the right), which reached the size of modern horses but still had low-crowned teeth for eating leaves. The main lineage of horses (upper branches with grasses in background), however, developed high-crowned teeth for grinding tough, gritty grasses, which wears teeth down quickly. There were several branches of three-toed horses in the Miocene, including the merychippines, the hipparionines, the calippines, and others. Like the anchitheres, some of these migrated to the Old World in the middle and late Miocene. All were extinct by the end of the Miocene, leaving only the one-toed horse lineage that was ancestral to modern horses (genus Equus). (Drawing by C. R. Prothero)