Symmetric key algorithms are for the bulk encryption of data or data streams. These algorithms are designed to be very fast and have a large number of possible keys. The best symmetric key algorithms offer excellent secrecy; once data is encrypted with a given key, there is no fast way to decrypt the data without possessing the same key.

Symmetric key algorithms can be divided into two categories: block and stream. Block algorithms encrypt data a block (many bytes) at a time, while stream algorithms encrypt byte-by-byte (or even bit-by-bit).

Different encryption algorithms are not equal. Some systems are not very good at protecting data, allowing encrypted information to be decrypted without knowledge of the requisite key. Others are quite resistant to even the most determined attack. The ability of a cryptographic system to protect information from attack is called its strength. Strength depends on many factors, including:

The secrecy of the key.

The difficulty of guessing the key or trying out all possible keys (a key search). Longer keys are generally more difficult to guess or find.

The difficulty of inverting the encryption algorithm without knowing the encryption key (breaking the encryption algorithm).

The existence (or lack) of back doors , or additional ways by which an encrypted file can be decrypted more easily without knowing the key.

The ability to decrypt an entire encrypted message if you know the way that a portion of it decrypts (called a known plaintext attack ).

The properties of the plaintext and knowledge of those properties by an attacker. For example, a cryptographic system may be vulnerable to attack if all messages encrypted with it begin or end with a known piece of plaintext. These kinds of regularities were used by the Allies to crack the German Enigma cipher during World War II.

In general, cryptographic strength is not proven; it is only disproven. When a new encryption algorithm is proposed, the author of the algorithm almost always believes that the algorithm offers “perfect” security[39]—that is, the author believes there is no way to decrypt an encrypted message without possession of the corresponding key. After all, if the algorithm contained a known flaw, then the author would not propose the algorithm in the first place (or at least would not propose it in good conscience).

As part of proving the strength of an algorithm, a mathematician can show that the algorithm is resistant to specific kinds of attacks that have been previously shown to compromise other algorithms. Unfortunately, even an algorithm that is resistant to every known attack is not necessarily secure, because new attacks are constantly being developed.

From time to time, some individuals or corporations claim that they have invented new symmetric encryption algorithms that are dramatically more secure than existing algorithms. Generally, these algorithms should be avoided. As there are no known attacks against the encryption algorithms that are in wide use today, there is no reason to use new, unproven encryption algorithms—algorithms that might have lurking flaws.

Among those who are not entirely familiar with the mathematics of cryptography, key length is a topic of continuing confusion. As we have seen, short keys can significantly compromise the security of encrypted messages, because an attacker can merely decrypt the message with every possible key so as to decipher the message’s content. But while short keys provide comparatively little security, extremely long keys do not necessarily provide significantly more practical security than keys of moderate length. That is, while keys of 40 or 56 bits are not terribly secure, a key of 256 bits does not offer significantly more real security than a key of 168 bits, or even a key of 128 bits.

To understand this apparent contradiction, it is important to understand what is really meant by the words key length , and how a brute force attack actually works.

Inside a computer, a cryptographic key is represented as a string of binary digits. Each binary digit can be a 0 or a 1. Thus, if a key is 1 bit in length, there are two possible keys: 0 and 1. If a key is 2 bits in length, there are four possible keys: 00, 01, 10, and 11. If a key is 3 bits in length, there are eight possible keys: 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, and 111. In general, each added key bit doubles the number of keys. The mathematical equation that relates the number of possible keys to the number of bits is:

number of keys = 2(number of bits)

If you are attempting to decrypt a message and do not have a copy of the key, the simplest way to decrypt the message is to do a brute force attack . These attacks are also called key search attacks , because they involve trying every possible key to see if that key decrypts the message. If the key is selected at random, then on average, an attacker will need to try half of all the possible keys before finding the actual decryption key.

Fortunately for those of us who depend upon symmetric encryption algorithms, it is a fairly simple matter to use longer keys by adding a few bits. Each time a bit is added; the difficulty for an attacker attempting a brute force attack doubles.

The first widely used encryption algorithm, the Data Encryption Standard (DES), used a key that was 56 bits long. At the time that the DES was adopted, many academics said that 56 bits was not sufficient: they argued for a key that was twice as long. But it appears that the U.S. National Security Agency did not want a cipher with a longer key length widely deployed, most likely because such a secure cipher would significantly complicate its job of international surveillance.[40] To further reduce the impact that the DES would have on its ability to collect international intelligence, U.S. corporations were forbidden from exporting products that implemented the DES algorithm.

In the early 1990s, a growing number of U.S. software publishers demanded the ability to export software that offered at least a modicum of security. As part of a compromise, a deal was brokered between the U.S. Department of Commerce, the National Security Agency, and the Software Publisher’s Association. Under the terms of that agreement, U.S. companies were allowed to export mass-market software that incorporated encryption, provided that the products used a particular encryption algorithm and that the length of the key was limited to 40 bits. At the same time, some U.S. banks started using an algorithm called Triple-DES—basically, a threefold application of the DES algorithm, for encrypting some financial transactions. Triple-DES has a key size of 168 bits. Triple-DES is described in the following section.

In October 2000, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) approved the Rinjdael encryption algorithm as the new U.S. Advanced Encryption Standard. Rinjdael can be used with keys of 128, 192, or 256 bits. The algorithm’s extremely fast speed combined with its status as the government-chosen standard, means that it will likely be used in preference to the DES, Triple-DES, and other algorithms in the future.

So how many bits is enough? That depends on how fast the attacker can try different keys and how long you wish to keep your information secure. As Table 3-1 shows, if an attacker can try only 10 keys per second, then a 40-bit key will protect a message for more than 3,484 years. Of course, today’s computers can try many thousands of keys per second—and with special-purpose hardware and software, they can try hundreds of thousands. Key search speed can be further improved by running the same program on hundreds or thousands of computers at a time. Thus, it’s possible to search a million keys per second or more using today’s technology. If you have the ability to search a million keys per second, you can try all 40-bit keys in only 13 days.

If a key that is 40 bits long is clearly not sufficient to keep information secure, how many bits are necessary? In April 1993, the Clinton Administration introduced the Clipper encryption chip as part of its Escrowed Encryption Initiative (EEI). This chip used a key that was 80 bits long. As Table 3-1 shows, an 80-bit key is more than adequate for many applications. If you could search a billion keys per second, trying all 80-bit keys would still require 38 million years! Clipper was widely criticized not because of the key length, but because the Clipper encryption algorithm was kept secret by the National Security Agency, and because each Clipper chip came with a “back door” that allowed information encrypted by each Clipper chip to be decrypted by the U.S. government in support of law enforcement and intelligence needs.

Table 3-1. Estimated success of brute force attacks (for different numbers of bits in the key and number of keys that can be tried per second)

Length of key | Keys searched per second | Postulated key searching technology[a] | Approximate time to search all possible keys |

|---|---|---|---|

40 bits[b] | 10 | 10-year-old desktop computer | 3,484 years |

40 bits | 1,000 | Typical desktop computer today | 35 years |

40 bits | 1 million | Small network of desktops | 13 days |

40 bits | 1 billion | Medium-sized corporate network | 18 minutes |

56 bits | 1 million | Desktop computer a few years from now | 2,283 years |

56 bits | 1 billion | Medium-sized corporate network | 2.3 years |

56 bits[c] | 100 billion | DES-cracking machine | 8 days |

64 bits | 1 billion | Medium-sized corporate network | 585 years |

80 bits | 1 million | Small network of desktops | 38 billion years |

80 bits | 1 billion | Medium-sized corporate network | 38 million years |

128 bits | 1 billion | Medium-sized corporate network | 1022 years |

128 bits | 1 billion billion (1 x 1018) | Large-scale Internet project in the year 2005 | 10,783 billion years |

128 bits | 1 x 1023 | Special-purpose quantum computer, year 2015? | 108 million years |

192 bits | 1 billion | Medium-sized corporate network | 2 x 1041 years |

192 bits | 1 billion billion | Large-scale Internet project in the year 2005 | 2 x 1032 years |

192 bits | 1 x 1023 | Special-purpose quantum computer, year 2015? | 2 x 1027 years |

256 bits | 1 x 1023 | Special-purpose quantum computer, year 2015? | 3.7 x 1046 years |

256 bits | 1 x 1032 | Special-purpose quantum computer, year 2040? | 3.7 x 1037 years |

[a] Computing speeds assume that a typical desktop computer in the year 2001 can execute approximately 500 million instructions per second. This is roughly the speed of a 500 Mhz Pentium III computer. [b] In 1997, a 40-bit key was cracked in only 3.5 hours. [c] In 2000, a 56-bit key was cracked in less than 4 days. | |||

Increasing the key size from 80 bits to 128 bits dramatically increases the amount of effort to guess the key. As the table shows, if there were a computer that could search a billion keys per second, and if you had a billion of these computers, it would still take 10,783 billion years to search all possible 128-bit keys. As our Sun is likely to become a red giant within the next 4 billion years and, in so doing, destroy the Earth, a 128-bit encryption key should be sufficient for most cryptographic uses, assuming that there are no other weaknesses in the algorithm used.

Lately, there’s been considerable interest in the field of quantum computing. Scientists postulate that it should be possible to create atomic-sized computers specially designed to crack encryption keys. But while quantum computers could rapidly crack 56-bit DES keys, it’s unlikely that a quantum computer could make a dent on a 128-bit encryption key within a reasonable time: even if you could crack 1 x 1023 keys per second, it would still take 108 million years to try all possible 128-bit encryption keys.

It should be pretty clear at this point that there is no need, given the parameters of cryptography and physics as we understand them today, to use key lengths that are larger than 128 bits. Nevertheless, there seems to be a marketing push towards increasingly larger and larger keys. The Rinjdael algorithm can be operated with 128-bit, 192-bit, or 256-bit keys. If it turns out that there is an as-yet hidden flaw in the Rinjdael algorithm that gives away half the key bits, then the use of the longer keys might make sense. Otherwise, why you would want to use those longer key lengths isn’t clear, but if you want them, they are there for you.

There are many symmetric key algorithms in use today. Some of the algorithms that are commonly encountered in the field of web security are summarized in the following list; a more complete list of algorithms is in Figure 3-2.

- DES

The Data Encryption Standard was adopted as a U.S. government standard in 1977 and as an ANSI standard in 1981. The DES is a block cipher that uses a 56-bit key and has several different operating modes depending on the purpose for which it is employed. The DES is a strong algorithm, but today the short key length limits its use. Indeed, in 1998 a special-purpose machine for “cracking DES” was created by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) for under $250,000. In one demonstration, it found the key to an encrypted message in less than a day in conjunction with a coalition of computer users around the world.

- Triple-DES

Triple-DES is a way to make the DES dramatically more secure by using the DES encryption algorithm three times with three different keys, for a total key length of 168 bits. Also called “3DES,” this algorithm has been widely used by financial institutions and by the Secure Shell program (ssh). Simply using the DES twice with two different keys does not improve its security to the extent that one might at first suspect because of a theoretical kind of known plaintext attack called meet-in-the-middle, in which an attacker simultaneously attempts encrypting the plaintext with a single DES operation and decrypting the ciphertext with another single DES operation, until a match is made in the middle.

- Blowfish

Blowfish is a fast, compact, and simple block encryption algorithm invented by Bruce Schneier. The algorithm allows a variable-length key, up to 448 bits, and is optimized for execution on 32- or 64-bit processors. The algorithm is unpatented and has been placed in the public domain. Blowfish is used in the Secure Shell and other programs.

- IDEA

The International Data Encryption Algorithm (IDEA) was developed in Zurich, Switzerland, by James L. Massey and Xuejia Lai and published in 1990. IDEA uses a 128-bit key. IDEA is used by the popular program PGP to encrypt files and electronic mail. Unfortunately, wider use of IDEA has been hampered by a series of software patents on the algorithm, which are currently held by Ascom-Tech AG in Solothurn, Switzerland.[41]

- RC2

This block cipher was originally developed by Ronald Rivest and kept as a trade secret by RSA Data Security. The algorithm was revealed by an anonymous Usenet posting in 1996 and appears to be reasonably strong (although there are some particular keys that are weak). RC2 allows keys between 1 and 2048 bits. The RC2 key length was traditionally limited to 40 bits in software that was sold for export to allow for decryption by the U.S. National Security Agency.[42]

- RC4

This stream cipher was originally developed by Ronald Rivest and kept as a trade secret by RSA Data Security. This algorithm was also revealed by an anonymous Usenet posting in 1994 and appears to be reasonably strong. RC4 allows keys between 1 and 2048 bits. The RC4 key length was traditionally limited to 40 bits in software that was sold for export.

- RC5

This block cipher was developed by Ronald Rivest and published in 1994. RC5 allows a user-defined key length, data block size, and number of encryption rounds.

- Rinjdael (AES)

This block cipher was developed by Joan Daemen and Vincent Rijmen, and chosen in October 2000 by the National Institute of Standards and Technology to be the United State’s new Advanced Encryption Standard. Rinjdael is an extraordinarily fast and compact cipher that can use keys that are 128, 192, or 256 bits long.

Table 3-2. Common symmetric encryption algorithms

Algorithm | Description | Key Length | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|

Blowfish | Block cipher developed by Schneier | 1-448 bits | Λ |

DES | Data Encryption Standard adopted as a U.S. government standard in 1977 | 56 bits | § |

IDEA | Block cipher developed by Massey and Xuejia | 128 bits | Λ |

MARS | AES finalist developed by IBM | 128-256 bits | ⊘ |

RC2 | Block cipher developed by Rivest | 1-2048 bits | Ω |

RC4 | Stream cipher developed by Rivest | 1-2048 bits | Λ |

RC5 | Block cipher developed by Ronald Rivest and published in 1994 | 128-256 bits | ⊘ |

RC6 | AES finalist developed by RSA Labs | 128-256 bits | ⊘ |

Rijndael | NIST selection for AES, developed by Daemen and Rijmen | 128-256 bits | Ω |

Serpent | AES finalist developed by Anderson, Biham, and Knudsen | 128-256 bits | ⊘ |

Triple-DES | A three-fold application of the DES algorithm | 168 bits | Λ |

Twofish | AES candidate developed by Schneier | 128-256 bits | ⊘ |

Key to ratings: Ω) Excellent algorithm. This algorithm is widely used and is believed to be secure, provided that keys of sufficient length are used. Λ) Algorithm appears strong but is being phased out for other algorithms that are faster or thought to be more secure. ⊘) Algorithm appears to be strong but will not be widely deployed because it was not chosen as the AES standard. §) Use of this algorithm is no longer recommended because of short key length or mathematical weaknesses. Data encrypted with this algorithm should be reasonably secure from casual browsing, but would not withstand a determined attack by a moderately-funded attacker. |

If you are going to use cryptography to protect information, then you must assume that people who you do not wish to access your information will be recording the encrypted data and attempting to decrypt it forcibly.[43] To be useful, your cryptographic system must be resistant to this kind of direct attack.

Attacks against encrypted information fall into three main categories. They are:

Key search (brute force) attacks (Section 3.2.4.1)

Cryptanalysis (Section 3.2.4.2)

Systems-bases attacks (Section 3.2.4.3)

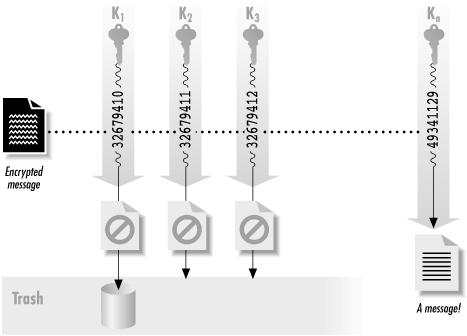

As we saw earlier, the simplest way to attack an encrypted message is simply to attempt to decrypt the message with every possible key. Most attempts will fail, but eventually one of the tries will succeed and either allow the cracker into the system or permit the ciphertext to be decrypted. These attacks, illustrated in Figure 3-3, are called key search or brute force attacks.

There’s no way to defend against a key search attack, because there’s no way to keep an attacker from trying to decrypt your message with every possible key.

Key search attacks are not very efficient. And, as we showed earlier, if the chosen key is long enough, a key search attack is not even feasible: for instance, with a 128-bit key and any conceivable computing technology, life on Earth will cease to exist long before even a single key is likely to be cracked!

On the other hand, many key search attacks are made considerably simpler because most users pick keys based on small passwords with printable characters. For a 128-bit key to be truly secure, all 128 bits must be randomly chosen. That is, there must be 2128 distinct keys that could possibly be used to encrypt the data. If a “128-bit key” is actually derived from a password of four lower-case letters, then even though the key appears to be 128 bits long, there are really only 26 x 26 x 26 x 26, or 456,976 different keys that could actually be used. Instead of a 128-bit key, a key that is chosen from four lower-case letters has an effective key length between 18 bits and 19 bits! (This is because 218 = 262,144, while 219 = 524,288.)

From this simple analysis, it would appear that any of the strong algorithms described earlier with a 128-bit key length should be sufficient for most cryptographic needs—both now and forever more. Unfortunately, there are a number of factors that make this solution technically, legally, or politically unsuitable for many applications, as we’ll see later in this chapter.

If key length were the only factor determining the security of a cipher, everyone interested in exchanging secret messages would simply use codes with 128-bit keys, and all cryptanalysts (people who break codes) would have to find new jobs. Cryptography would be a solved branch of mathematics, similar to simple addition.

What keeps cryptography interesting is the fact that most encryption algorithms do not live up to our expectations. Key search attacks are seldom required to divulge the contents of an encrypted message. Instead, most encryption algorithms can be defeated by using a combination of sophisticated mathematics and computing power. The result is that many encrypted messages can be deciphered without knowing the key. A skillful cryptanalyst can sometimes decipher encrypted text without even knowing the encryption algorithm.

A cryptanalytic attack can have two possible goals. The cryptanalyst might have ciphertext and want to discover the plaintext, or might have ciphertext and want to discover the encryption key that was used to encrypt it. (These goals are similar but not quite the same.) The following attacks are commonly used when the encryption algorithm is known, and these may be applied to traffic on the Web:

- Known plaintext attack

In this type of attack, the cryptanalyst has a block of plaintext and a corresponding block of ciphertext. Although this may seem an unlikely occurrence, it is actually quite common when cryptography is used to protect electronic mail (with standard headers at the beginning of each message), standard forms, or hard disks (with known structures at predetermined locations on the disk). The goal of a known plaintext attack is to determine the cryptographic key (and possibly the algorithm), which can then be used to decrypt other messages.

- Chosen plaintext attack

In this type of attack, the cryptanalyst can have the subject of the attack (unknowingly) encrypt chosen blocks of data, creating a result that the cryptanalyst can then analyze. Chosen plaintext attacks are simpler to carry out than they might appear. (For example, the subject of the attack might be a radio link that encrypts and retransmits messages received by telephone.) The goal of a chosen plaintext attack is to determine the cryptographic key, which can then be used to decrypt other messages.

- Differential cryptanalysis

This attack, which is a form of chosen plaintext attack, involves encrypting many texts that are only slightly different from one another and comparing the results.

- Differential fault analysis

This attack works against cryptographic systems that are built in hardware. The device is subjected to environmental factors (heat, stress, radiation) designed to coax the device into making mistakes during the encryption or decryption operation. These faults can be analyzed and from them the device’s internal state, including the encryption key or algorithm, can possibly be learned.

- Differential power analysis

This is another attack against cryptographic hardware—in particular, smart cards. By observing the power that a smart card uses to encrypt a chosen block of data, it is possible to learn a little bit of information about the structure of the secret key. By subjecting the smart card to a number of specially-chosen data blocks and carefully monitoring the power used, it is possible to determine the secret key.

- Differential timing analysis

This attack is similar to differential power analysis, except that the attacker carefully monitors the time that the smart card takes to perform the requested encryption operations.

The only reliable way to determine if an algorithm is strong is to hire a stable of the world’s best cryptographers and pay them to find a weakness. This is the approach used by the National Security Agency. Unfortunately, this approach is beyond the ability of most cryptographers, who instead settle on an alternative known as peer review.

Peer review is the process by which most mathematical and scientific truths are verified. First, a person comes up with a new idea or proposes a new theory. Next, the inventor attempts to test his idea or theory on his own. If the idea holds up, it is next published in an academic journal or otherwise publicized within a community of experts. If the experts are motivated, they might look at the idea and see if it has any worth. If the idea stands up over the passage of time, especially if many experts try and fail to disprove the idea, it comes to be regarded as truth.

Peer review of cryptographic algorithms and computer security software follows a similar process. As individuals or organizations come up with a new algorithm, the algorithm is published. If the algorithm is sufficiently interesting, cryptographers or other academics might be motivated to find flaws in it. If the algorithm can stand the test of time, it might be secure.

It’s important to realize that simply publishing an algorithm or a piece of software does not guarantee that flaws will be found. The WEP (Wireless Encryption Protocol) encryption algorithm used by the 802.11 networking standard was published for many years before a significant flaw was found in the algorithm—the flaw had been there all along, but no one had bothered to look for it.

The peer review process isn’t perfect, but it’s better than the alternative: no review at all. Do not trust people who say they’ve developed a new encryption algorithm, but also say that they don’t want to disclose how the algorithm works because such disclosure would compromise the strength of the algorithm. In practice, there is no way to keep an algorithm secret: if the algorithm is being used to store information that is valuable, an attacker will purchase (or steal) a copy of a program that implements the algorithm, disassemble the program, and figure out how it works.[44] True cryptographic security lies in openness and peer review, not in algorithmic secrecy.

Another way of breaking a code is to attack the cryptographic system that uses the cryptographic algorithm, without actually attacking the algorithm itself.

One of the most spectacular cases of systems-based attacks was the VC-I video encryption algorithm used for early satellite TV broadcasts. For years, video pirates sold decoder boxes that could intercept the transmissions of keys and use them to decrypt the broadcasts. The VC-I encryption algorithm was sound, but the system as a whole was weak. (This case also demonstrates the fact that when a lot of money is at stake, people will often find the flaws in a weak encryption system and those flaws will be exploited.)

Many of the early attacks against Netscape’s implementation of SSL were actually attacks on Netscape Navigator’s implementation, rather than on the SSL protocol itself. In one published attack, researchers Wagner and Goldberg at the University of California at Berkeley discovered that Navigator’s random number generator was not really random. It was possible for attackers to closely monitor the computer on which Navigator was running, predict the random number generator’s starting configuration, and determine the randomly chosen key using a fairly straightforward method. In another attack, the researchers discovered that they could easily modify the Navigator program itself so that the random number generator would not be executed. This entirely eliminated the need to guess the key.

[39] This is not to be confused with the formal term “perfect secrecy.”

[40] The NSA operates a world-wide intelligence surveillance network. This network relies, to a large extent, on the fact that the majority of the information transmitted electronically is transmitted without encryption. The network is also used for obtaining information about the number of messages exchanged between various destinations, a technique called traffic analysis . Although it is widely assumed that the NSA has sufficient computer power to forcibly decrypt a few encrypted messages, not even the NSA has the computer power to routinely decrypt all of the world’s electronic communications.

[41] Although we are generally in favor of intellectual property protection, we are opposed to the concept of software patents, in part because they hinder the development and use of innovative software by individuals and small companies. Software patents also tend to hinder some forms of experimental research and education.

[42] The 40-bit “exportable” implementation of SSL actually uses a 128-bit RC2 key, in which 88 bits are revealed, producing a “40-bit secret.” Netscape claimed that the 88 bits provided protection against codebook attacks, in which all 240 keys would be precomputed and the resulting encryption patterns stored. Other SSL implementors have suggested that using a 128-bit key in all cases and simply revealing 88 bits of key in exportable versions of Navigator made Netscape’s SSL implementation easier to write.

[43] Whitfield Diffie has pointed out that if your data is not going to be subject to this sort of direct attack, then there is no need to encrypt it.

[44] In the case of the RC2 and RC4 encryption algorithm, the attackers went further and published source code for the reverse-engineered algorithms!