Most filtering software was hurriedly developed in response to a perceived market opportunity and, to a lesser extent, to political need. Access control software was used to explain in courts and legislatures why more direct political limitations on the Internet’s content were unnecessary and unworkable. Because of the rush to market, most of the filtering rules and lists were largely ad hoc, as demonstrated by the example of the blocked ISDN web pages.

The Platform for Internet Content Selection (PICS) is an effort of the World Wide Web Consortium to develop an open Internet infrastructure for the exchange of information about web content and the creation of automated blocking software.

When the PICS project was first launched, it was heralded as a voluntary industry effort that was an alternative to government regulation. When Congress passed the Communications Decency Act, making it a federal crime to put pornography on the Internet where it could be accessed by children,[197] PICS became the subject of courtroom testimony.

PICS was also by far the most controversial project that the W3C pursued during its first five years. Although PICS was designed as an alternative to state regulation and censorship of the Internet, critics argued that PICS could itself become a powerful tool for supporting state-sponsored censorship. That’s because PICS is a general-purpose system that can be used to filter out all sorts of material, from neo-Nazi propaganda to information about clean elections and nonviolent civil disobedience. Critics argued that strong industry support for PICS meant that the tools for censorship would be built into the platform used by billions of people.

Today many of these fears seem overstated, but that is only because the PICS project has largely failed. Although support for PICS is built into Internet Explorer and many proxy servers, the unwillingness of web sites to rate themselves combined with the lack of third-party ratings bureaus has prevented the technology from playing a role in the emerging world of content filtering and control—at least for now.

In the following sections, we’ll provide an overview of how PICS was designed to work. Despite its apparent failure, PICS provides valuable insight into how content controls could work. Detailed information about PICS can be found in Appendix D, and on the Consortium’s web server at http://w3.org/PICS/.

PICS is a general-purpose system for labeling the content of documents that appear on the World Wide Web. PICS labels contain one or more ratings that are issued by a rating service. Those labels are supposed to contain machine-readable information about the content of a web site, allowing software to make decisions about whether or not access to a web site should be allowed.

For example, a PICS label might say that a particular web page contains pornographic images, or that a collection of pages on a web site deals with homosexuality. A PICS label might say that all of the pages at another web site are historically inaccurate.

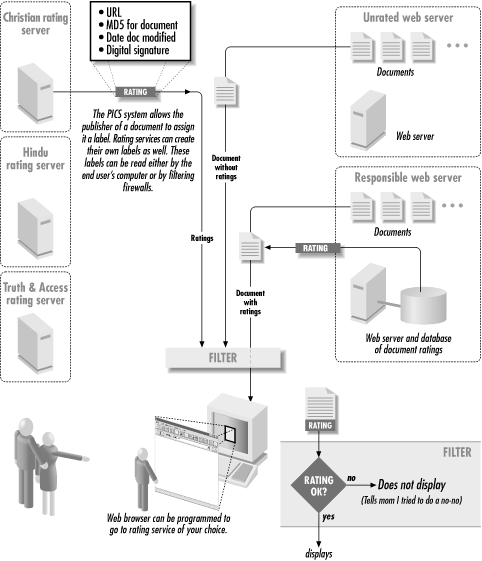

Any document that has a URL can be labeled with PICS. The labels can be distributed directly with the labeled information—for example, in the HTTP header or in the HTML body. Alternatively, PICS labels can be distributed directly by third-party rating services over the Internet or on a CD-ROM. John can rate Jane’s web pages using PICS—with or without her knowledge or permission.PICS labels can apply to multiple URLs, including a subset of files on a site, an entire site, or a collection of sites. A PICS label can also apply to a particular document or even a particular version of a particular document. PICS labels can be digitally signed for added confidence. PICS labels can be ignored, giving the user full access to the Web’s content. Alternatively, labels can be used to block access to objectionable content. Labels can be interpreted by the user’s web browser or operating system. An entire organization or even a country could have a particular PICS-enabled policy enforced through the use of a blocking proxy server located on a firewall. Figure 23-1 depicts a typical PICS system in operation.

Software that implements PICS has a variety of technical advantages over simple blocking software:

PICS allows per-document blocking.

PICS makes it possible to get blocking ratings from more than one source.

Because PICS is a generic framework for rating web-based information, different users can have different access-control rules.

PICS needed this amount of flexibility because it was supposed to be the basis of a worldwide system for content control, and people in different countries have different standards for what sort of information should be blocked. But this flexibility ultimately was one of the reasons for the system’s failure. Instead of delivering a system for blocking pornography, the W3C created a filtering system construction kit, and nobody ever put it together.

PICS can be used for assigning many different kinds of labels to many different kinds of information:

PICS labels can specify the type or amount of sex, nudity, or profane language in a document.

PICS labels can specify the historical accuracy of a document.[198]

PICS labels can specify whether a document is or is not hate speech.

PICS labels can specify the political leanings of a document or its author.

PICS labels can rate whether a photograph is overexposed or underexposed.

PICS labels can indicate the year in which a document was created. They can denote copyright status and any rights that are implicitly granted by the document’s copyright holder.

PICS labels can indicate whether a chat room is moderated or unmoderated.

PICS labels can apply to programs. For example, a label can specify whether or not a program has been tested and approved by a testing laboratory.

Clearly, PICS labels do not need to specify information that is factual. Instead, they are specifically designed to convey a particular person’s or labeling authority’s opinion of a document. Although PICS was developed for keeping kids from pornography, and thus blunting legislative efforts to regulate the Internet, PICS labels aren’t necessarily for kids.

Does PICS promote censorship? In their article describing PICS in Communications of the ACM, Paul Resnick and James Miller discussed at great length how PICS is an open standard that is a substitute for censorship.[199] They have given many examples in their articles and presentations on how voluntary ratings by publishers and third-party rating services can obviate the need for censoring the Internet as a whole.

The PICS anticensorship argument is quite straightforward. According to Resnick and Miller, without a rating service such as PICS, parents who wish to shield their children from objectionable material have only a few crude options at their disposal:

Disallow access to the Internet entirely

Disallow access to any site thought to have the objectionable material

Supervise their children at all times while the children access the Internet

Seek legal solutions (such as the Communications Decency Act)

PICS gave parents another option. Web browsers could be configured so that documents on the Web with objectionable ratings are not displayed. Very intelligent web browsers might even prefetch the ratings for all hypertext links; links for documents with objectionable ratings might not even be displayed as such. Parents have the option of either allowing unrated documents to pass through, or restricting their browser software so that unrated documents cannot be displayed either.

Recognizing that different individuals have differing opinions of what is acceptable, PICS has provisions for multiple ratings services. PICS is an open standard, so practically any dimension that can be quantified can be rated. And realizing that it is impossible for any rating organization to rate all of the content on the World Wide Web, PICS has provisions for publishers to rate their own content. Parents then have the option of deciding whether to accept these self-assigned ratings.

Digital signatures allow labels created by one rating service to be cached or even distributed by the rated web site while minimizing the possibility that the labels will be modified by those distributing them. This would allow, for example, a site that receives millions of hits a day to distribute the ratings of underfunded militant religious organizations that might not have the financial resources to deploy a high-powered Internet server capable of servicing millions of label lookups every day.

Unlike blocking software, which operates at the TCP/IP protocol level to block access to an entire site, PICS can label and therefore control access to content on a document-by-document basis. (The PICS “generic” labels can also be used to label an entire site, should an organization wish to do so.) This is the great advantage of PICS, making the system ideally suited to electronic libraries. With PICS, children can be given access to J. D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey without giving them access to The Catcher in the Rye. Additionally, an online library could rate each chapter of The Catcher in the Rye, giving children access to some chapters but not to others. In fact, PICS makes it possible to restrict access to specific documents in electronic libraries in ways that have never been possible in physical libraries.

Having created such a framework for ratings, Miller and Resnick show how it can be extended to other venues. Businesses, for example, might configure their networks so that recreational sites cannot be accessed during the business day. There have also been discussions as to how PICS can be extended for other purposes, such as rating software quality.

Miller and Resnick argued that PICS didn’t promote censorship, but they must have a different definition for the word “censorship” than we do. The sole purpose of PICS appears to be facilitating the creation of software that blocks access to particular documents on the Web on the basis of their content. For a 15-year-old student in Alabama trying to get information about sexual orientation, censorship is censorship, no matter whether the blocking is at the behest of the student’s parents, teachers, ministers, or elected officials; whether those people have the right to censor what the teenager sees is a separate issue from whether or not the blockage is censorship.

Resnick said that there is an important distinction to be made between official censorship of information at its source by government and “access control,” which he defines as the blocking of what gets received. He argues that confusing “censorship” with “access controls” benefits no one.[200]

It is true that PICS is a technology designed to facilitate access controls. It is a powerful, well thought out, extensible system. Its support for third-party ratings, digital signatures, real-time queries, and labeling of all kinds of documents all but guarantees that it could be a technology of choice for totalitarian regimes that seek to limit their citizens’ access to unapproved information and ideas. Its scalability assures that it would be up to the task.

Whatever the claims of its authors, PICS is a technology that remains well-suited for building censorship software.

Although PICS was designed for blocking software implemented on the user’s own machine, any large-scale deployment of PICS really needs to have the content control in the network itself.

The biggest problem with implementing blocking technology on the user’s computer is that it is easily defeated. Software that runs on unprotected operating systems is vulnerable. It is unreasonable to assume that an inquisitive 10-year-old child is not going to be able to disable software that is running on an unsecure desktop computer running the Windows or Macintosh operating system. (Considering what some 10-year-old children do on computers now when unattended, disabling blocking software is child’s play.)

The only way to make blocking software work in practice is to run it upstream from the end user’s computer. This is why America Online’s “parental controls” feature works: it’s run on the AOL servers, rather than the home computer. Children are given their own logins with their own passwords. Unless they know their parents’ passwords, they can’t change the settings on their own accounts.

[197] The Act was eventually held to violate the First Amendment, and thus unconstitutional. Many members of Congress knew it would be unconstitutional and furthermore could not be enforced against non-U.S. web sites, but voted for it nonetheless so as to appease their constituencies. What is more troubling are the members who either believe that U.S. law governs the whole Internet, or believe that the First Amendment shouldn’t apply to the World Wide Web.

[198] The attention to historical accuracy and hate speech is largely a response to the Simon Wiesenthal Center, which has argued that web sites that promote hate speech or deny the Jewish Holocaust should not be allowed to exist on the Internet.

[199] See “PICS: Internet Access Controls Without Censorship,” October 1996, p. 87. The paper also appears at http://www.w3.org/PICS/iacwcv2.htm.

[200] Personal communication, March 20, 1997.