All I knew was that Phill thought it would be “cool.” It was the fall of 1970, my sophomore year at the University of North Carolina, and my big brother, Phill, a senior at Duke University, suggested, “Let’s fool around with the biofeedback machine.” Biofeedback is a treatment technique that uses electronic monitoring to help you quiet your mind and body. Today these machines are roughly the size of your palm, but in 1970, biofeedback was just developing. This machine, constructed and housed in Duke’s School of Engineering, took up all four walls, floor to ceiling, in a 13 × 20-foot room. That didn’t surprise me. The UNC sociology department’s sole computer was a crude stack of machinery that occupied every inch of a 500-square-foot room (otherwise known as a Manhattan studio apartment). Now, of course, the little computer we can hold in our hands is 100 times more powerful.

The following Saturday, Phill and I spent several hours exploring this electromyography (EMG) phenomenon, attaching electrodes to our foreheads and listening to the feedback, to the rise and fall of sound that alerts us to the tension in our frontalis muscle. Our goal was to deepen the tone, because a deeper tone reflects a muscle with less tension. And as that tone deepens and the frontalis muscle quiets, the rest of the body and mind tend to follow suit.

My most fascinating discovery on that day was that I could “do” things to deepen the tone. By making minute adjustments, like how I was sitting, how I was breathing, what I was focusing on, I could alter the feedback. But to get my mind and body really quiet, I needed to listen to the tone, notice when it deepened, and then invite my mind and body to “keep doing whatever you are doing.” I didn’t know how it was happening; I just tried to catch that wave and ride it. I was quite captivated by the whole experience.

After a few Saturdays in the Engineering lab, electrodes taped to our foreheads, our ability to control that tone became exquisite. And then . . . I got it! My body and mind developed a memory of this state of physical and mental tranquility. I could call it up on cue, simply by taking a calming breath and quieting my thoughts (in addition to some subtle, visceral shifts in my consciousness that I still can’t describe). Today, more than forty years later, I can still return to that peaceful place with about half a minute of attention.

That profound experience was the beginning of my appreciation of the stepping back process, the ability to mentally separate ourselves from the ongoing thoughts and feelings of daily life. By the time I finished college, I was a daily meditator, and I continued that practice for several more years. In the late 1970s I worked as a staff psychologist at the Boston Pain Unit, one of the first in-patient therapeutic communities for chronic pain patients. I witnessed firsthand how biofeedback and relaxation training could enhance a patient’s ability to step back, step away, from suffering. This was true even for those with the most challenging physical ailments.

Here is a little more foreshadowing of the chapters to come. For my doctoral dissertation, I conducted a relatively complex study on the patients of the Boston Pain Unit. I observed the differences between patients who complied with the required components of the treatment versus the patients who asked a staff member for additional treatment opportunities that were available to them, such as an extra counseling session or an additional biofeedback appointment. My hypothesis was that those patients who requested added services did so because they sensed the possibility of positive change, and they were ready to take responsibility for strengthening their minds and bodies. I predicted that that shift in their attitudes would indeed help them get stronger. They were no longer just complying with staff requests and attending the fixed schedule of activities. They were asserting themselves. They were actively engaged in the learning process and motivated to improve.

The results of my research indicated that this was true. Those who were more engaged had significantly less pain perception and a discernibly elevated mood by the end of their treatments. They were stronger and far less depressed. I didn’t know it at the time, but this was the beginning of my belief in the richness of the “I want this” stance. Want it is the topic of the next three chapters.

My work as a clinical psychologist gradually shifted away from helping those with chronic pain and toward treating those with anxiety and panic attacks. In the mid-1980s I began writing about my work, and that became my first book, Don’t Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety Attacks. Within those pages I defined the concept of the Observer, the part of each of us that can detach from our worried, self-critical, or hopeless judgments in order to simply notice what we are thinking and feeling.

The Observer bears similarities to what is now often referred to as mindfulness, a term first introduced in 1979 by Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD, the exceedingly talented scientist and teacher who led a structured eight-week course in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction. If you have been paying attention to advice givers in the physical or mental health circles, you have no doubt heard encouraging words about the benefits of meditation, mindfulness, and formal relaxation. You’ll find numerous studies showing that adding these practices to your skill set can augment treatment for issues as diverse as stress reduction, pain management, heart disease, high blood pressure, infertility, tension headaches, premenstrual syndrome, irritable bowel, insomnia, depression, and, of course, anxiety and panic attacks.

Is It a Signal, or Is It Noise?

I’m not going to teach you all those formal practices (although you can learn about them in Don’t Panic and plenty of other places). Instead, we are going to take all that has been discovered over the last forty years through research and treatment and cull it down to two sets of tasks, both having to do with your ability to mentally step back.

The first task is to activate what we’ve been talking about in these last four chapters. We are going to interrupt your worry to give you some choice in the worry process. You job will be to insert a pause in your worrying—a pause just long enough to declare that you are going to treat that worry as a signal or as noise. Remember, when worries are signals, your job is to problem solve. When they are noise . . . well, they are just repetitious, unproductive, anxiety-producing racket, and you can do anything you want with them other than take them seriously. But you have to declare how you’re going to treat them—as signals or as noise—before you can respond to them. And you can make that decision only by stepping away from your worry long enough to choose.

The Observer

The part of us that can detach from our

worried, self-critical, or hopeless judgments in

order to simply notice what we are

thinking and feeling.

Ah, but there’s a catch. If you are like most people with anxiety, you cannot always determine whether it is a signal or just noise. And if you wait and wait and wait to act until you are certain which it is, you will continue to stall and avoid. The truth is, there will be plenty of times when you will not know for sure whether it is a signal or noise, but you can recognize when you are tangled up in one of your typical noisy, anxious themes. In those instances, your best move is to say, “I don’t know if it’s a signal or just noise, so I am going to act as though it’s noise.” (I mentioned this “act as though” theme in Chapter 6, and I’ll be talking about it several more times before we’re done. Indeed, the concept is so important to our strategy that it will get its very own special attention in Chapter 18.)

A Moment-by-Moment Awareness

of “I Don’t Want This”

The second function of mentally stepping back is to help you become alert to all the ways you resist stepping toward your difficulties. Anytime we begin to reflect on an upcoming threatening situation, that resistant, I-don’t-want-this part of us (which we spoke about in Chapter 3) will move quickly into one of two broad reactions. Each move seems like an extension of our limbic system’s fight, flight, or freeze response. The first resistant move looks similar to our flight or freeze behaviors. When our urge to flee is kindled, we avoid facing the situation by procrastinating, stalling, or simply escaping to a safer place. We behave this way because we don’t want to feel doubt or address the worries that pop up as we begin to move toward the things we fear. When we respond with freeze behaviors, we shut down our feelings, becoming numb or flat. Some people exhibit this freeze response in social situations. They might struggle to come up with the right words when they are called on in class, “blank out” during a test, or forget someone’s name when they run into them.

The second way we tend to resist when we face difficulty or feel threatened is to adopt what might be considered fight strategies within the fight, flight, or freeze response, because we are working harder as opposed to backing away. To feel safe, we over-prepare, gathering more and more information we hope will guarantee that we take the right actions. We review our notes repeatedly. We call on those we think will know the right answers, believing they can reassure us and guard us from harm. We check, check, and recheck “just to be sure.” We take all these actions in service of protecting ourselves from emotional or physical insult or injury. We firmly believe that a “right answer” exists, and if we keep trying to figure it out, we’ll eventually discover that right answer—the answer that will keep us from risking pain or embarrassment or failure. Despite our belief that we are applying positive energy to the problem-solving process, fight strategies are avoidance, too. As long as we are planning, preparing, thinking through all the options, researching to determine the best choices, consulting the latest data, and trying to be smart about our decisions, we aren’t being productive. We are actually stalling, just as we do with our flight or freeze responses. Our perfectionistic tendencies, driven by our need to avoid mistakes, are really procrastination in disguise. Ironically, the more we stall, the more time we have to worry.

When that resisting part of you is in charge, it devotes 100 percent of its attention to actively protecting you. That means it cannot simultaneously look for ways in which you can grow. In fact, it will stifle any potential you might have for creative exploring or learning.

If you want some choice in the direction of your future, it’s essential that you learn to step back from such automatic responses. You have to detach yourself from them long enough to observe them, label them for what they are, and decide if you want to continue standing still in that way. As you anticipate an event, if you can notice a shift in your state of mind and body—a shift toward resistance—then you have the chance to step away from it if you want to. The key task here is noticing. Sometimes it takes a while before any of us can become consciously alert to what we’re doing. But now we have some suspicious clues, based on our fight, flight, or freeze tendencies, as seen below.

Observing the Signs of Resistance

Practice stepping back to notice these tendencies:

- stalling or procrastinating

- becoming numb or feeling flat

- retreating to a safer place

- over-preparing

- continually researching

- continually seeking advice

- checking repeatedly

- seeking the “right answer”

- detailed thinking through of all possible options

- worrying!

A Momentary Stop in the Action

Have you ever been caught in a tangle of briars? You know you have to back away to get unstuck; it’s common sense. When you are caught in a tangle of negative thoughts and defensive actions, you have to back away from that tangle before you can move forward. Quieting skills are the cornerstone of this stepping back process. But, listen up, within our strategy you need to quiet down for only a few moments.

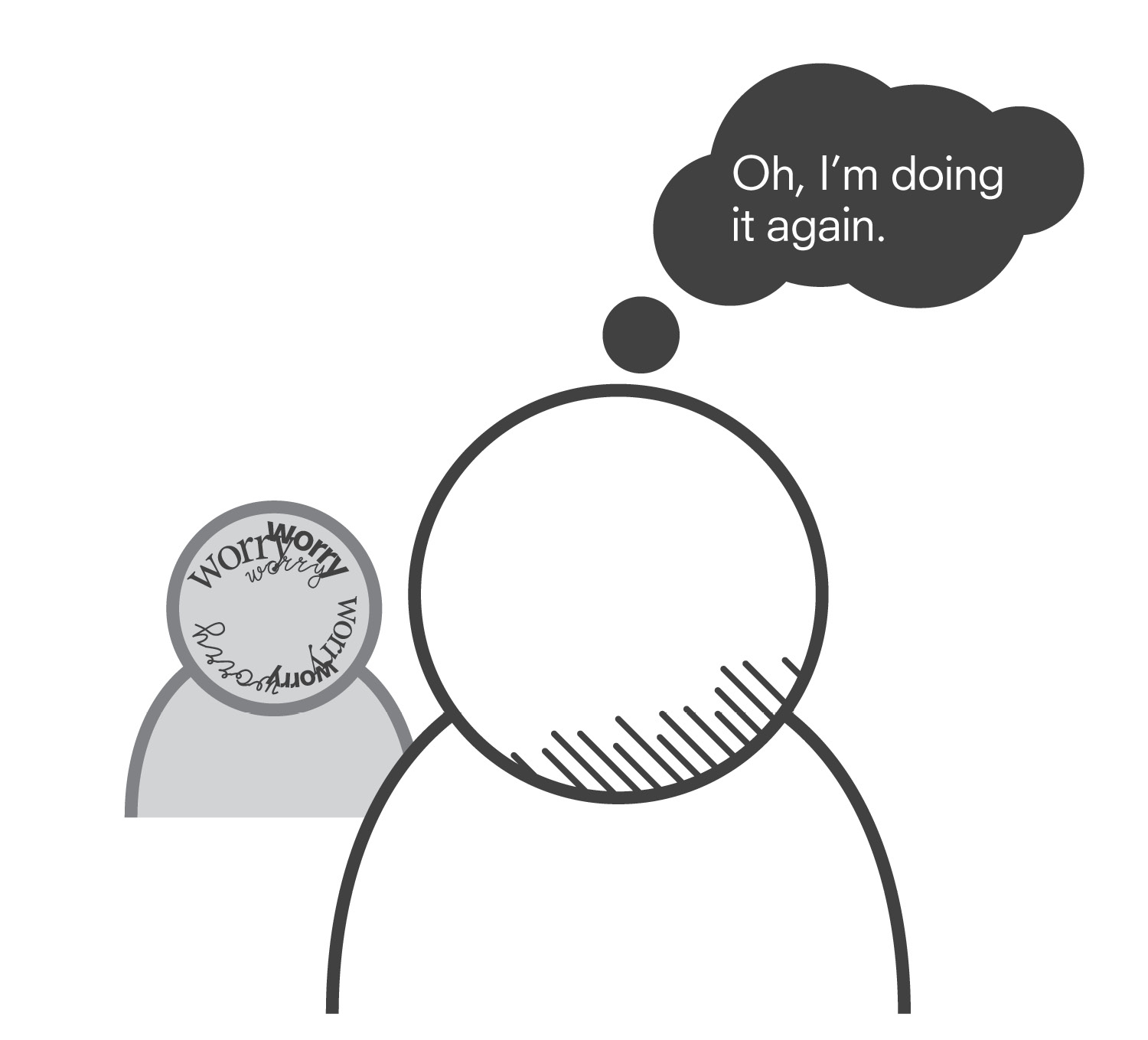

If we want to change an old response pattern, the first task in our strategy is to catch ourselves in that pattern. We have to know when to step back; we need to cue ourselves at that moment; and we have to know how to step back. The “when” is whenever we get tangled up with the old pattern that needs a new response. Cueing ourselves in the moment involves a simple statement such as, “Oh, I’m doing it again,” or “I’m starting to freak out now, and I have an urge to [step away, avoid this, do a compulsion, etc.].”

Figure 3. Step BACK to gain perspective.

The “how” entails a separation from our automatic thoughts, feelings, and actions in order to find our observing self. Quieting down permits you to step away, even if for only a few seconds, so that you can find your Observer and notice what’s going on. When you are worrying or think you might be engaged in some resistant behavior, all you have to do is cue yourself (e.g., “I think I might be stuck again”) and then simply shift into a quiet pause. Loosen the grip of that automatic, negative reaction to the present moment. Let go a bit. If you’d like, you can do it with a breath: take a nice, long inhale and then a gentle, slow exhale. On that exhale you can even gently invite your mind to “quiet” or “let go.” Allow your mind to respond to your invitation. Slacken your jaw. Loosen your shoulders. Relax your eyes. And give yourself even a mere five seconds to feel self-compassion, an added gift.

Allow your emotional and physical arousal to come forward into your arena of observation. When you can clear and quiet your mind, you can then hear these messages independent of your biases (like “get rid of pain immediately” or “don’t approach if uncertain”). Observe them from an objective, supportive, accepting stance. They are not “bad.” They are not “wrong.” Very simply, they are the messages you have been using until this moment. You can now choose to continue in this frame of mind that comes with those messages, or you can offer yourself a new response.

The only thing we are paying attention to right now is how to get you to a place of choice. You need to be capable of pausing the current action if you want the option of changing directions. Mentally step back. Get a perspective on the current moment by disengaging enough to observe it and label it. That’s it. Don’t worry about anything else right now. Don’t worry about your ability to change course right now. Develop this skill, and we will build on it soon enough.

All of this seems straightforward and perfectly feasible on paper, but it can feel pretty threatening during moments of, well, threat. Because when we feel vulnerable, we automatically seek to defend ourselves. We are certainly not inclined to drop our guard. That’s why I want you to understand the logic behind this action. Our intention is to help you move from an automatic, rigid, almost unconscious response to one of choice, to a response based on conscious awareness. You cannot embrace a new point of view until you let go of your current stance. If you can loosen the grip that threat and worry have on you, you can then gather information more relevant to the present moment. You can become curious: “What have I just been thinking? What am I feeling? What is actually going on around me? What’s the truth about this risk?” Answering these questions allows you to move to your next task: “How do I want to respond to what I am learning about my present moment?”

The Art and Gift of the Quiet Moment

- Cue yourself (for instance, “I think I’m stuck again”)

- Shift into a pause of quiet. Loosen the grip of that automatic, negative reaction to the present moment. Let go a bit.

- If you’d like, do it with a breath: a nice long inhale and a slow exhale. On that exhale, gently invite your mind to “quiet” or “let go.” Allow your mind to respond to your invitation.

- Slacken your jaw. Loosen your shoulders. Relax your eyes.

- Give yourself an added gift: a mere five seconds of self-compassion.

If you notice that you are scared or feeling threatened, you have a chance to determine whether or not this fear is a signal about this specific situation. If it is, you can decide how you want to respond to it rather than engaging in some knee-jerk reaction that pops up anytime you feel vulnerable. Perhaps it’s a signal that you are not ready to engage in this activity, or that this activity is truly not safe. In that case, you can choose to back away so you can prepare for next time or so you can escape true danger. In many circumstances that involve the anxiety disorders, instead of defending and protecting yourself or backing up to better prepare, the decision should be to step forward into the situation to learn more. So the choice you need to make is whether to avoid and guard, to back away so you can prepare, or to step forward and explore. We’re going to talk all about how to step forward in a later section of the book, surprisingly titled “Step Forward.”

As you examine the situation, you might decide that all these feelings stem from noise. You’re not about to humiliate yourself, and you can tolerate embarrassment when you stumble during your speech; the obsessive thought you just had doesn’t mean you’re a pedophile; you don’t have to treat this panicky feeling as a heart attack. Despite the strength of your thoughts and the intensity of your distress, they are still not signals of danger, even though you have been treating them as such. In these moments, you need to thwart the power of that anxiety-

provoking worry. When you choose to quiet your mind for a few moments so you can mentally step back, you are driving a little wedge of time into your anxious monologue. And within that little wedge of time, you are briefly shifting your focus of attention and giving yourself a different, concrete task. Up until that moment, you have been caught up in those negative thoughts and feelings. You have been marching to the beat of Anxiety’s drum. And now you are taking only a few moments to step away and then absorb yourself in another assignment: to get quiet. You can afford those few moments, can you not? Especially if it might break the spell that Anxiety has over you.

And we’re pausing not only to get quiet. Look how many tasks I’m asking you to accomplish in that brief little moment: cue yourself by subvocalizing a statement about how you’ve become stuck; maybe initiate a nice, long inhale and a gentle, slow exhale; invite yourself to let go of the other thoughts and feelings; invite your jaw to slacken and your shoulders to loosen; relax your eyes; and perhaps offer a little self-compassion. That’s a lot of stuff to do!

And that’s part of our strategy. The state of momentary dread and anxiety can be so all-consuming. If you want to break free of that pattern for a few moments, I think it’s best to give yourself a task during those moments that requires a significant degree of focused, conscious attention. This is not distraction. You are not trying to block out anything. You are still engaged in the present moment. You are simply shifting the way in which you are engaged.

Oh, hey, before I forget, I need to clue you in on an important point. You can’t do this stuff because I tell you to. The function of this task needs to make logical sense to you. And then you need to purposely and voluntarily choose to turn your attention away from a very compelling narrative of threat. Decide to let go because you decide. And then focus your attention on that process of letting go. Don’t comply with my instructions. Activate your own intention. The only way I’m going to help you here is if my strategy ultimately becomes your strategy.

Figure 4. The mindful stance—stepping BACK with detachment.

So when you create a mindful moment, what happens next? Instead of forging ahead with this anxious worrying or simultaneously fighting against it, you have come to a brief pause in the action by busying yourself with a series of small, quieting tasks. This momentary gap allows you the opportunity to start down a new path of thinking. It enables you a chance to take on a new point of view about what you are experiencing. It’s like a “Choose Your Own Adventure” novel, where you assume the role of the protagonist and make choices that determine your actions and the plot’s outcome. When you quiet your mind in these moments, you come to a fork in the road. Perhaps you have to decide, “Am I taking the path of believing that this is a signal? Or am I choosing to go down the path of treating it as noise?” Or maybe your two choices are between resuming your fight against distress and doubt, or taking the path that allows discomfort and doubt but leads to your positive future.

In Chapter 3, I illustrated how your resistance to feeling uncomfortable or uncertain—your I-don’t-want-this response—has the potential to increase your symptoms, make you more afraid, and strengthen your urge to avoid. It’s as though you are shoving on that pendulum, which adds energy, causing the pendulum to swing back with equal or greater force, and making you experience more discomfort and more uncertainty. Contributing to your own suffering is, of course, exactly what you don’t want.

Now what might happen to that same pendulum if you decide to detach from your urge to push that threat away? Check out Figure 4. What if you do nothing? What if you step back, away from the drama of fear and resistance, and don’t push the feelings of distress and uncertainty away? When you withdraw your energy from the pendulum, then gravity and air friction take over, putting a drag on that pendulum and slowing it down. Shall I say that again? When you do nothing to resist the present moment, it will dissipate. Anxiety requires your involvement. When you detach, you win. That’s what we’re looking for.

Listen, for some people (and you could be one of those people), all they need to do is to learn to step back into a mindful position, and that move alone will be enough to get them stronger. Even if they first need to apply all the other tactics of this book’s strategy, in the end they may need only this simple process of mindful awareness of the moment and they will be set free.

At this point in our work, good reader, all we’re looking for is the opportunity to make a conscious choice instead of running on Anxiety’s autopilot. To give yourself that option, you must learn to step back when you are worrying, stalling, or avoiding. Without this skill, you will likely treat all your worries as signals when some of them are really just noise and can be dropped, ignored, and neglected. Sure, each of us knows how to get comfortable by backing up into a safe routine and avoiding anything new or threatening. But we also need the capacity to step into new territory. If we don’t develop that skill and tolerance, we can never advance. Learn to find that mindfully quiet moment so you can access your Observer. It is a critical tool that will help you gain perspective on a problem and generate new, creative ideas. If you want help in mastering this ability to step back, you have a number of avenues. Look into courses in mindfulness or mindfulness-based stress reduction, meditation training, relaxation training, clinical hypnosis, yoga, and biofeedback.

Getting quiet in the moment is different from calming down and relaxing. You don’t need to become mentally and physically calm. We are not looking for peace and tranquility here. In fact, calming down can be contraindicated during a difficult task. For our purposes, you need to be alert and focused. You need a means of detaching yourself from your ongoing negative interpretation so you can confirm it is called for (i.e., a signal). And you need a means of detaching yourself from your compulsive behaviors when they cause you to avoid the world instead of engage in it. Whether you are obsessing or acting defensively, if you pause long enough to mentally step back, you give yourself a chance to refresh your point of view so that you can step forward. But that doesn’t require you to relax.

The Buddhists refer to the practice of meditation as a means of developing a finely tuned awareness of their own feelings. This awareness allows them to recognize the spark before the flame. And that’s what we want to develop here. By stepping back you can begin to create a gap between the spark and the flame, between your urge to avoid and your avoidant action. And, like the Buddhists, you are going to find that this is an immensely helpful tactic.