Little good news for the Union came out of the Western theaters to offset bad news in Virginia during July and August. Quite the contrary, in fact. The dizzying pace of Union conquests in the Mississippi Valley ended abruptly in June. Late that month the Union gunboat flotilla from upriver and part of Farragut’s fleet from downriver met at Vicksburg. For the next month these two previously unbeatable task forces, supported by 3,000 army soldiers, tried in vain to batter into submission this “Gibraltar of the West,” as Confederates labeled it. Situated on a 200-foot bluff and heavily fortified, Vicksburg could be invested by a land force only from the east. Not until 1863 would a Union commander figure out a way to do that. For several weeks in July 1862 the navy’s two hundred guns and twenty-three mortars pounded Vicksburg and took heavy fire in return. The contest proved a standoff. Northern soldiers tried to dig a bypass canal out of range of Vicksburg’s batteries, but low water in the Mississippi foiled their efforts. More than half of the soldiers and sailors fell sick with various maladies including typhoid, dysentery, and malaria, with several dying every day.

Farragut began to fear that his deep-draft ocean-going vessels would be trapped by the falling river, and prepared to pull out. Before he could leave, however, an intrepid Rebel sea dog gave the Yankees a black eye. The Confederates had been building an ironclad gunboat up the jungle-shrouded Yazoo River. Commanded by Lieutenant Isaac Newton Brown, a thirty-year antebellum veteran of the U.S. Navy, the CSS Arkansas steamed down the Yazoo to take on the whole Union fleet in mid-July. It burst like an apparition on the surprised Union vessels, tied up on either bank with steam down. The Arkansas fired its ten guns, as Brown later wrote, “to every point of the circumference, without the fear of hitting a friend or missing an enemy.”1 To Farragut’s disgust, the Arkansas ran the gauntlet of Union fire and tied up under the protection of Vicksburg’s guns. The Southern press puffed the Arkansas’s exploits into a great victory, and so it appeared when the two Union fleets gave up and separately retreated upriver and down at the end of July.2

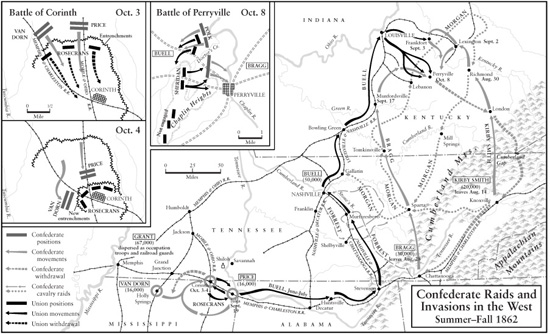

Union forces in Tennessee and northern Mississippi experienced even greater embarrassments. In part the Federals were victims of their own earlier success. After the capture of Corinth (May 30) and Memphis (June 6), the captors needed to divert several combat units to occupation duties in the forty thousand or more square miles they had conquered. Declining river levels in this unusually dry summer made them dependent on railroads for supply, so they had to divert even more troops to protect the rails and bridges from frequent guerrilla and cavalry raids. When Halleck went to Washington to become general in chief in July, Grant assumed command of these occupation forces. For the next three months he had his hands full dealing with guerrillas, contrabands, Northern merchants seeking trading permits, and efforts by two small Confederate armies to recapture Corinth.

Meanwhile Buell took his Army of the Ohio eastward to capture Chattanooga and accomplish Lincoln’s cherished goal of liberating East Tennessee. He failed spectacularly. By late August Buell found himself compelled to abandon this campaign and race northward to prevent the loss of Kentucky as well as central Tennessee. Like McClellan, Buell was a political conservative who believed in a “soft” war to conciliate rather than to coerce Southern civilians back into the Union. He was therefore reluctant to deal harshly with guerrillas who cut his supply lines and harassed his movements with nightly attacks on bridges and outposts.

Worse was yet to come. In early July two of the Confederacy’s ablest and boldest cavalry leaders rode forth on raids deep behind Union lines to wreak havoc and capture supply depots all over central Kentucky and Tennessee. On July 4 John Hunt Morgan left Knoxville with eight hundred troopers, Kentucky rebels to a man. They headed north into their native state where during the next twenty-four days they rode a thousand miles, destroyed several supply depots, captured and paroled twelve hundred prisoners at various Union posts, and returned home with the loss of fewer than ninety men.

Meanwhile Nathan Bedford Forrest rode out of Chattanooga on July 6 at the head of a thousand men. Bluffing the Union garrison of equal size at Murfreesboro into surrendering, Forrest tore up the railroad, captured a million dollars worth of supplies, and then burned three bridges on the line south of Nashville that Buell depended on for supplies. When Union crews finally repaired the damage, Morgan’s merry men struck again, capturing a train and pushing the flaming boxcars into an 800-foot tunnel north of Nashville, causing the timbers to burn and the tunnel to collapse.

All of this was embarrassing enough and convinced Union commanders that to cope with enemy cavalry raids they must develop effective cavalry of their own—something that was a long time in coming. But the damage to the Union cause was more than psychological. The Richmond Enquirer may have exaggerated when it claimed that “Forrest in Tennessee and Morgan in Kentucky have done much to retrieve the disasters that lost us parts of both those States.” But it did not exaggerate much. “Our cavalry is paving the way for me in Middle Tennessee and Kentucky,” wrote General Braxton Bragg in late July.3

Bragg had taken command of the Confederate Army of Tennessee after the evacuation of Corinth. As Buell crawled toward Chattanooga, Bragg moved some 35,000 troops toward that city, mostly by a roundabout rail route, and got there well before Buell approached. In cooperation with General Edmund Kirby Smith, who commanded 18,000 Confederate soldiers in Knoxville, Bragg planned an offensive into central and eastern Kentucky. Smith started first, on August 14, and Bragg departed Chattanooga August 28. In tandem they moved north on parallel routes about a hundred miles apart. On August 30 Kirby Smith captured a Union garrison of 4,000 men (mostly new troops recruited that summer) at Richmond, Kentucky. Smith marched into Lexington and on to Frankfort, the state capital, where he prepared to install a Confederate governor of Kentucky.

Bragg’s army advanced into middle Tennessee, forcing Buell to break off his own campaign against Chattanooga and rush northward to defend Nashville. Bragg bypassed the city and captured another garrison of 4,000 Union soldiers (also mostly new regiments) at Munfordville in Kentucky, only sixty miles south of Louisville. Panic seized Unionists in that city; even Cincinnati declared a state of emergency. Buell’s Army of the Ohio continued north to its namesake river at Louisville, while thousands of contrabands along the 225 miles from which Buell had withdrawn found themselves in Confederate territory and in slavery again. On September 5 Bragg issued a congratulatory order to his troops: “COMRADES: . . . The Enemy is in full retreat, with consternation and demoralization devastating his ranks. . . . Alabamians! your State is redeemed. Tennesseans! . . . You return conquerors. Kentuckians! the first great blow has been struck for your freedom.”4

In the Eastern states, most attention focused on events in Virginia and Maryland. When the New York press could spare a moment for the Western theater, the news seemed “gloomy in the extreme,” for the campaign there “loses to the Union cause more than it gained in the brilliant campaign of last spring.” But the danger to that cause appeared even more serious closer to home. From Washington on August 27 Lieutenant Charles Francis Adams Jr., of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, wrote to his father in London: “The air of this city seems thick with treachery; our army seems in danger of utter demoralization and I have not since the war began felt such a tug on my nerves. . . . Everything is ripe for a terrible panic.”5

How had matters come to such a pass? After the Seven Days the Army of the Potomac licked its wounds and tried to rest and refit at Harrison’s Landing. But malaria, dysentery, and typhoid during this sickly season on the Virginia Peninsula subtracted more men from the ranks than were added by recovered wounded and returning stragglers. Send me reinforcements, McClellan asked the government, and I will resume the offensive even though Lee has 200,000 men. Lincoln’s private response was very much to the point. On July 25 he told Senator Orville Browning that if by some miracle he could send 100,000 men to McClellan, the general would suddenly discover that Lee had 400,000.6

Lincoln’s words were prescient. That same day the new General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck visited McClellan to discuss what to do with his army. With 30,000 reinforcements, said McClellan, he could take Richmond. Only 20,000 were available, said Halleck. If that was not sufficient, the Army of the Potomac would have to be withdrawn from the Peninsula. Alarmed, McClellan agreed to 20,000. As soon as Halleck returned to Washington, however, a telegram from McClellan arrived asking for 50,000. That was the final straw. Halleck ordered McClellan to transfer his army to northern Virginia to reinforce Pope. McClellan had been hoisted by his own petard. If Lee really had 200,000 men holding a position between McClellan’s 90,000 and Pope’s 40,000, Halleck pointed out, the Confederates could use their interior lines to strike Pope and McClellan in turn with superior numbers. Thus it was imperative to combine the two Union armies to shield Washington.7

McClellan bitterly protested these orders, but Halleck, backed by Lincoln, insisted. Convinced that McClellan’s inactive army posed little danger, Lee by early August had already shifted 24,000 troops under Jackson to confront Pope. Rumor magnified this force—Jackson’s reputation was worth several divisions. This perceived threat to Pope convinced Lincoln of the need to transfer McClellan’s army. On August 9 near Culpeper, Jackson clashed with part of Pope’s army—commanded by Jackson’s old victim in the Valley, Nathaniel Banks—and defeated it in the battle of Cedar Mountain. McClellan learned of this outcome with satisfaction. In a letter to his wife, he predicted that Pope “will be badly thrashed within two days . . . very badly whipped he will be & ought to be— such a villain as he is ought to bring defeat upon any cause that employs him.” Then “they will be very glad to turn over the redemption of their affairs to me. I won’t undertake it unless I have full & entire control.”8

These shocking words help explain why McClellan was in no hurry to obey orders to reinforce Pope. He received those orders on August 3; the first units did not leave until August 14; the last troops finally embarked at Fortress Monroe for Washington on September 3. As they left the Peninsula, the mood of many soldiers was sour and depressed. “We have fought more desperately, lost more men, and endured more hardships than any army under the sun, and all for nothing,” wrote Charles Brewster of the 10th Massachusetts. As a New York regiment disembarked in Alexandria after transfer from the Peninsula, one of its officers felt “sorrowful and humiliated when looking back over a year and finding ourselves on the same ground as then. The debris of the Grand Army [has] come back to its starting place with its ranks decimated, its morale failing, while thousands who sleep their last sleep on the Peninsula demand the cause of their sacrifice.”9

McClellan himself departed the Peninsula on August 23, uncertain whether he or Pope would command the combined armies. “I don’t see how I can remain in the service if placed under Pope—it would be too great a disgrace,” he wrote his wife. But if “Pope is beaten,” which McClellan expected, “they may want me to save Washn again.” Once they “suffer a terrible defeat” and Pope is “disposed of . . . I know that with God’s help I can save them.”10

Lee and Jackson were doing their best to see that Pope was “disposed of.” In mid-August Lee left 22,000 men to defend Richmond and moved north with the rest to reinforce Jackson for an attack on Pope before McClellan’s troops could join him. For ten days Lee’s reunited force of 55,000 carried out a campaign of thrust and parry with Pope’s army of equal size. Pope pulled back north of the Rappahannock River but skillfully avoided giving Lee an opportunity to attack. With the first of McClellan’s divisions about to reach Pope in the last week of August, Lee decided on a typically bold but dangerous maneuver. He split his army and sent Jackson with half of it on a wide flanking movement around Pope’s right and rear to sever his supply line.

Pope’s scouts detected Jackson’s march to the northwest on August 25 and reported that he was heading for his old haunts in the Shenandoah Valley. They failed to detect Jackson’s turn eastward on the 26th. Jackson’s foot cavalry logged fifty miles in their two-day march and swarmed like locusts on the huge Union supply depot at Manassas Junction twenty miles in Pope’s rear. The famished rebels feasted on what they could eat and carry, and put the rest to the torch.

Pope had been outgeneralled, but he hoped to turn this embarrassment into an opportunity to “bag Jackson” before the other half of the Army of Northern Virginia could join him. But first he had to find Jackson. The slippery Stonewall had moved his three divisions over separate routes from Manassas Junction to a wooded ridge just west of the Bull Run battlefield of the previous year. Pope’s overworked cavalry reported Jackson to be here, there, and everywhere. From Pope’s headquarters on August 28 poured a series of confusing orders to his own army and to four divisions from the Army of the Potomac plus two from Burnside’s army that had been transferred from North Carolina.

When and if united, these reinforcements would give Pope some 75,000 men (to Lee’s 50,000 when united). But the Union divisions from three different armies had never fought together before, and rivalries and jealousies among some of their generals did not augur well. Commander of two of the Army of the Potomac divisions was McClellan’s protégé Fitz-John Porter, who had called Pope an “Ass” a month earlier and had not changed his mind since. “Pope is a fool,” Porter wrote privately, and the administration that had appointed him was no better. “Would that this army was in Washington to rid us of incumbents ruining our country.”11

Wreckage left by Stonewall Jackson’s troops after they appropriated and destroyed Union supplies at Manassas Junction, Virginia, on August 27, 1862. (Library of Congress)

Just before sunset on August 28 one of Pope’s divisions found Jackson. As this division marched unaware next to the Confederates hiding in the woods, Jackson could not resist the temptation to attack them. A vicious firefight continued until dark with neither side giving an inch. That night a new flurry of orders went out to Federal units, which began to concentrate in front of Jackson at dawn. Thinking that Jackson was retreating to join Longstreet (in reality Longstreet was advancing to join Jackson), Pope hurled his arriving divisions in piecemeal attacks against a strong Confederate position along the cuts and fills of an unfinished railroad. Pope managed to get only 32,000 of his men in action against Jackson’s 22,000 on August 29.

Porter’s troops came up on the Union left in position to move against Jackson’s flank, but having no orders and misled by a dustcloud that Stuart’s cavalry kicked up to convince him that a large body of the enemy was in front of him, Porter did nothing. Later in the day Pope ordered him to attack Jackson’s right flank. By then Longstreet’s corps had arrived and closed up on Jackson’s flank, so Porter declined to obey the order. For this refusal he was, five months later, court-martialed and cashiered from the service. Long after the war Porter received a new trial, which reversed the verdict because of evidence of Longstreet’s presence. Porter was, in part, the victim of the poisonous atmosphere in 1862–1863. But he had not concealed his opinions of Pope, of Republicans and abolitionists, and of Lincoln and Stanton. Moreover, his 10,000 veteran soldiers remained idle on August 29. Longstreet’s presence notwithstanding, this idleness contributed to Pope’s inability to dislodge Jackson.

On August 30 Lee pulled back some units to realign them for another flanking move around Pope. Again misinterpreting these movements as an enemy retreat, Pope remained unaware of Longstreet’s presence and launched a full-scale attack on Jackson’s half of the Army of Northern Virginia. When they were fully engaged, Longstreet counterattacked against Pope’s virtually open left flank. “The slaughter was very heavy,” wrote the twenty-four-year-old Major Walter Taylor, Lee’s adjutant who was all over the battlefield carrying orders from the commander. “On some parts of the field their dead lie in files.”12 Through the long August afternoon the Federals fell back to Henry House Hill, where the heaviest fighting had taken place thirteen months earlier. Here a desperate twilight stand finally halted the Confederates. During the night a dispirited Union army retreated across Bull Run. Instead of following directly, Lee sent Jackson’s tired, hungry men on another flanking march around Pope’s right. During a torrential downpour on September 1, two Union divisions stopped them at Chantilly, only fifteen miles from Washington.

This second battle of Bull Run was a defeat fully as humiliating as the first, with greater potential danger to the Union cause. Angry recriminations flew in all directions. Most of the men in Pope’s Army of Virginia as well as the Army of the Potomac units that had fought there were demoralized, disgusted, and bitter toward Pope, whom they blamed for blunders and mismanagement. Pope in turn blamed Porter and McClellan.

Indeed, McClellan had much to answer for. He was at Alexandria with two corps of the Army of the Potomac during the battle. On August 27 and 28 Halleck repeatedly ordered him to send William B. Franklin’s corps to Pope, to be followed by Edwin V. Sumner’s corps. Back from McClellan came as many telegrams explaining why “neither Franklin’s nor Sumner’s corps is now in condition to move and fight a battle”—because their artillery and cavalry had not arrived. Pope did not need cavalry and could get along without artillery, said Halleck; he needed the infantry of these veteran corps. “There must be no further delay in moving Franklin’s corps toward Manassas,” Halleck wired McClellan on the evening of August 28. McClellan replied that Franklin would march in the morning. But next day he halted Franklin six miles out, in direct disobedience to Halleck’s orders. The general in chief, exhausted from sleepless nights dealing not only with this crisis but also with the simultaneous Confederate invasion of Kentucky, could not budge McClellan. Franklin’s corps stayed where it was and its 10,000 men went into camp within sound of the battle.13

Franklin was another of McClellan’s protégés, and his soldiers took their cue from him. When Pope’s discouraged survivors retreated wearily toward Washington on the night of August 30, they encountered the advance units of Franklin’s corps, which had made it as far as Centreville that day. “Some of the more frank among them,” wrote one of Pope’s men, “expressed their delight at the defeat of Pope and his army. . . . Disgusted and sick at heart, we continued our slow march along.” General Carl Schurz, one of Pope’s division commanders, overheard some of Franklin’s subordinates voice “their pleasure at Pope’s discomfiture without the slightest concealment, and [they] spoke of our government in Washington with an affectation of supercilious contempt.”14

In a telegram to Lincoln on August 29, McClellan revealed his real reason for halting Franklin and not hurrying up Sumner. The best course, suggested McClellan, might be “to leave Pope to get out of his scrape & at once use all our means to make the Capitol perfectly safe.” The president was appalled. McClellan “wanted Pope defeated,” Lincoln told his private secretary. All evidence indicates that Lincoln was right. General Sumner “broke out in hot anger when he learned that McClellan had said his corps was not in a condition for fighting,” according to Lincoln’s secretary. “If I had been ordered to advance right on,” Sumner later testified, “I should have been in that Second Bull Run battle with my whole force.”15

These were dark, dismal days in the North—perhaps the darkest of many such days during the war. “For the first time,” wrote the Washington bureau chief of the New York Tribune on September 1, “I believe it possible . . . that Washington may be taken.”16 With remarkable unanimity, newspapers of various political persuasions agreed that “the Country is in . . . extreme peril. The Rebels seem to be pushing forward their forces all along the border line from the Atlantic to the Missouri.” And, “disguise it as we may, the Union arms have been repeatedly, disgracefully, and decisively beaten.” Unless there was some change, “the Union cause is doomed to a speedy and disastrous overthrow.”17

“Despondency was seen everywhere” on the streets of New York, according to many observers. Among Unionists in Baltimore “the mortification is great and the disappointment so deep that every man seems to carry his feelings in his countenance.”18 George Templeton Strong described September 3 as “a day of depressing malignant dyspepsia. . . . We the people have been in a state of nausea and irritation all day long.” Four days later Strong believed that “the North is rapidly sinking just now, as it has been sinking rapidly for two months and more.” The New York Times reported that many people were asking: “Of what use are all these terrible sacrifices? Shall we have nothing but defeat to show for all our valor?”19

Demoralization on the Northern home front was bad enough. Demoralization in the army was at least as bad—and potentially more deadly. A New Hampshire captain whose regiment had lost heavily at Bull Run declared that “the whole army is disgusted. . . . You need not be surprised if success falls to the rebels with astonishing rapidity.” “Our men are sick of the war,” wrote Washington Roebling, a New Jersey officer and future builder of the Brooklyn Bridge. “They fight without an aim and without enthusiasm; they have no confidence in their leaders.” A New York colonel thought “there is no prospect or hopes of success in this war.”20 A brigade commander who had fought at both Bull Run and Chantilly wrote to his wife on September 4: “I believe that the war is nearly over, for the enemy is an audacious one. . . . I am more despondent than ever before.” Another brigade commander confirmed that “there is a general feeling that the Southern Confederacy will be recognized and that they deserve to be recognized.”21

No one was more acutely aware of the army’s demoralization than Lincoln. And no one had more responsibility for doing something about it. A newspaper reporter who spoke with Lincoln on August 30 had never seen the president so “wrathful” against McClellan. Lincoln seemed to think that McClellan was “a little crazy,” according to his private secretary John Hay, but he agreed with Hay that “envy jealousy and spite are probably a better explanation of his present conduct.”22 Lincoln did not lack advice on what to do about the matter. Secretary of War Stanton wanted McClellan court-martialed; Secretary of the Treasury Chase said he should be shot. Four of Lincoln’s Cabinet members signed a memorandum urging the president to dismiss McClellan. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles did not sign but agreed with the sentiments in the memorandum.23

Lincoln did, too, but he knew that he would have an army mutiny on his hands if he retained Pope in command. He had earlier sounded out Burnside about taking over the army, but that general declined. There seemed no alternative to McClellan. Halleck agreed. At 7:30 A.M. on September 2 Lincoln and Halleck called on McClellan at his home during breakfast and asked him to take command of all the troops as they retreated into the defenses of Washington—Pope’s troops as well as his own. Three days later Lincoln expanded the order to give McClellan command of the merged armies in the field. “Again I have been called upon to save the country,” McClellan wrote his wife. He accepted because “under the circumstances no one else could save the country.”24

At a Cabinet meeting on September 2, Stanton and Chase vigorously opposed Lincoln’s action; Chase feared “it would prove a national calamity.” Two Cabinet members who kept diaries described Lincoln as “extremely distressed” during this meeting. “He seemed wrung by the bitterest anguish—said he felt ready to hang himself.” And the president was not the only one who felt that way. “There was a more disturbed and desponding feeling,” wrote Welles, “than I have ever witnessed in council.” Lincoln agreed that McClellan “had acted badly in this matter.” There was “a design, a purpose, in breaking down Pope, without regard to the consequences to the country,” admitted the president. “It is shocking to see and know this.” But the army was “utterly demoralized” and McClellan was the only man who could “reorganize the army and bring it out of chaos,” said Lincoln. “McClellan has the army with him . . . [and] we must use the tools we have. There is no man . . . who can . . . lick these troops of ours into shape half as well as he. . . . If he can’t fight himself, he excels in making others ready to fight.”25

The memorable response of soldiers to McClellan’s restoration to command confirmed Lincoln’s judgment. The weather on the afternoon of September 2 was “cold and rainy” as Pope’s dispirited men retreated toward Washington, recalled a veteran years later. “Everything had a look of sadness in union with our feelings. . . . Here were stragglers plodding through the mud . . . wagons wrecked and forlorn; half-formed regiments, part of the men with guns and part without . . . while everyone you met . . . looked as if he would like to hide his head somewhere from all the world.” Many soldiers then and later described what happened next. An officer mounted on a black horse with a lone escort met the first of the troops. A startled captain took one look and ran back to his colonel shouting “General McClellan is here. ‘Little Mac’ is on the road.” His men heard the cry. “From extreme sadness we passed in a twinkling to a delirium of delight. A Deliverer had come. . . . Men threw their caps high into the air, and danced and frolicked like schoolboys.” The excitement passed quickly down the line. “Way off in the distance as he passed the different corps we could hear them cheer him. Every one felt happy and jolly. We felt there was some chance. . . . The effect of this man’s presence . . . was electrical, and too wonderful to make it worth while attempting to give a reason for it.”26 The Washington correspondent of the Chicago Tribune, no friend of McClellan, witnessed this demonstration. “I have disbelieved the reports of the army’s affection for McClellan, being entirely unable to account for the phenomenon,” he wrote. “I cannot account for it to my satisfaction now, but I accept it as a fact.”27

McClellan brought order out of chaos and licked the troops into shape in a remarkably short time. Within a few days he had reorganized and amalgamated the disparate armies. This was perhaps his finest hour. He had gotten them ready to fight. Whether he would lead them to victory would soon be determined, for the Army of Northern Virginia had crossed the Potomac into Maryland looking for a fight.

By all the odds, Lee’s victorious but worn-out army should have gone into camp for rest and refitting after Second Manassas. They had been fighting or marching almost without cessation for ten weeks. Thousands were shoeless, their uniforms were rags, and all were hungry. Although beaten, the Union army in its formidable Washington defenses had twice as many men.

But Lee was a commander who habitually defied the odds. He gave almost no thought to retreating behind the Rappahannock or into the Shenandoah Valley where his army could be resupplied. He could not stay where he was in fought-over northern Virginia denuded of supplies at the end of a long and precarious logistical umbilical cord. He had the initiative and was loath to give it up. The best chance for Confederate victory was to strike again while the enemy was “much weakened and demoralized,” as Lee informed Jefferson Davis on September 3. Lee continued to believe that in a long war the greater numbers, resources, and industrial capacity of the North would prevail. Thus the South should try for a knockout punch while its armies had the power to deliver it. That time was now. Just as the Western Confederate armies were on the march in Kentucky, Lee proposed to invade Maryland, a slave state that many in the South believed to be eager to join the Confederacy, “and afford her an opportunity to throw off the oppression to which she is now subject.”28 The army could support itself from the rich, unspoiled Maryland countryside while drawing the enemy out of war-ravaged Virginia during the fall harvest. If all went well, the Army of Northern Virginia might even invade Pennsylvania and destroy the vital railroad bridge over the Susquehanna River.29

Without waiting for a reply to his September 3 letter to Davis, Lee ordered his troops to begin crossing the Potomac forty miles upriver from Washington on September 4. Lee was confident of Davis’s approval. Equally important, as an avid reader of both Southern and Northern newspapers, he was aware of Southern enthusiasm for an invasion as well as of the dejected state of Northern opinion. “Now is the time to strike the telling and decisive blows . . . and to bring the war to a close,” proclaimed the Richmond Dispatch. “The spirit of the army is high, the men . . . eagerly desire to avenge their ravaged country. . . . They exult in a sense of their superiority not only to the Yankees, but to any army that treads the earth.” Although a good many foot-sore soldiers did not share the Dispatch’s sentiments, some certainly did. “If we ever expect to end” the war, wrote a lieutenant in the 4th North Carolina, “we must invade the enemies country & make him feel the evils he is inflicting on us.”30

The North would never give up if the Confederacy remained on the defensive, agreed Southern editors. Nothing could be gained by “attempts at propitiating our enemy,” wrote one. “Gen. Lee understands the Northern character well enough to know that the surest guarantee of an early peace, is the vigorous prosecution of present successes,” declared another, and a third added: “If we ever have an honorable treaty of peace with the United States, it will be signed on the enemy’s territory.”31

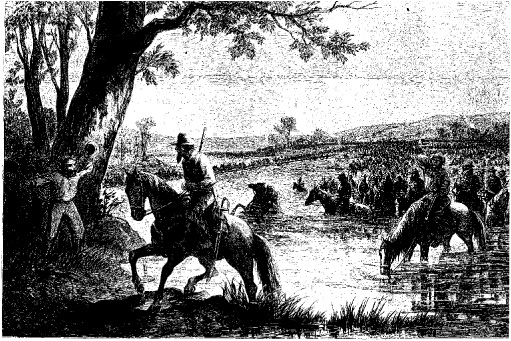

Confederate cavalry leading the Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac into Maryland on the night of September 4–5, 1862. (Harper’s Weekly)

Many Southerners could hardly believe the good news of Lee’s victory at Manassas and the invasion of Maryland. “To think how it has all changed since six months ago,” wrote a young woman in Virginia. “Then, we saw nothing but disaster and destruction before us . . . and I have wondered how we ever struggled through such depths of gloom. . . . How it has all so changed I can’t understand, but surely God has been with us.” The “almost incredible” contrast “with the position the Confederate states occupied three months ago” had a tendency to produce euphoria. “The winter of our discontent is turned to glorious summer,” exclaimed the Richmond Examiner.32 Lieutenant Charles C. Jones Jr. was confident that Maryland as well as “Tennessee and Kentucky will soon be entirely relieved from the Lincoln yoke.” Then “an excellent strategic point for occupation would be Harrisburg,” where “Pennsylvania would furnish abundant supplies for our army, while Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington would be cut off from the West.”33

Lee seemed to share this euphoria. When he learned on September 6 of Kirby Smith’s capture of Richmond, Kentucky, and the occupation of Lexington and Frankfort, Lee issued a general order to his own troops announcing “this great victory” which was “simultaneous with your own at Manassas. Soldiers, press onward! . . . Let the armies of the East and West vie with each other in discipline, bravery, and activity, and our brethren of our sister States will soon be released from tyranny, and our independence be established on a sure and abiding basis.” Two days later Lee issued a proclamation in Frederick “To the People of Maryland” announcing that his army had come “with the deepest sympathy [for] the wrongs that have been inflicted upon the citizens of a commonwealth allied to the States of the South by the strongest social, political, and commercial ties . . . to aid you in throwing off this foreign yoke, to enable you again to enjoy the inalienable rights of freemen.”34

The response of Marylanders in this largely Unionist part of the state was lukewarm. But Lee was aiming even higher, at the people and government of the North. “The present posture of affairs,” he wrote to Davis on September 8, “places it in [our] power . . . to propose [to the Union government] . . . the recognition of our independence.” Such a proposal, coming when “it is in our power to inflict injury on our adversary . . . would enable the people of the United States to determine at their coming elections whether they will support those who favor a prolongation of the war, or those who wish to bring it to a termination.”35

Lee’s reference to “their coming elections” revealed one of the purposes of his invasion: to encourage the election of Peace Democrats to the U. S. Congress. The war had placed Northern Democrats in a difficult position. Their antebellum political power had depended on an alliance with Southern Democrats. They had traditionally sided with the South on slavery and other issues of Southern concern (those who did not had become Republicans). In 1861–62 nearly all Northern Democrats professed support for restoration of the Union. But the party soon divided into “War” and “Peace” Democrats. The former agreed with Republicans that disunion must be suppressed by military means. But they disagreed with the hard-war measures that evolved as Republican policy in 1862. They voted against confiscation and emancipation bills in Congress. They opposed Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus and the military arrest of alleged Confederate sympathizers. They passed angry resolutions against such measures in their state and county conventions during 1862.

Peace Democrats opposed these measures even more vociferously. And by 1862 they also began to speak out against the war itself as a means of restoring the Union—especially the kind of war it was becoming, a war to destroy the Old South and slavery instead of a war to restore “the Union as it was.” That phrase became their slogan; an armistice and peace negotiations became their policy. “Shall This War Ever Cease?” asked the title of a typical editorial in a Newark Democratic newspaper. “The people,” agreed a Cincinnati Democrat, “are depressed by the interminable nature of this war.” Former Governor Thomas Seymour of Connecticut considered the idea that the Union could be restored by war a “monstrous fallacy.” Such convictions became stronger when the war seemed to be going badly, as it was in the late summer of 1862.36

Republicans likened Peace Democrats to the venomous copperhead snake, and the label “Copperhead” stuck. Republicans equated opposition to the war with support for the Confederacy and thus tarnished Copperheads with the taint of treason. They also exaggerated the Copperheads’ influence in the Democratic party and tended to conflate the War Democrats’ opposition to Republican war policies with opposition to the war itself.

But so did many Southern leaders. The Richmond Dispatch believed that in the North “there is a large and powerful body of citizens who are bitterly opposed to the present war.”37 That is why Lee foresaw “their coming elections” as a contest between “those who favor a prolongation of the war” (Republicans) and “those who wish to bring it to a termination” (Democrats). And termination, with Southern armies in Maryland and Kentucky, would mean Confederate independence. Thus the New York Times hit close to the mark when it maintained that the election of a Democratic majority in the next House of Representatives “would be regarded everywhere at the South as a symptom of division in the Northern States—as an indication that public sentiment had turned against the war.”38

It would be so regarded in Europe as well. French officials, in particular, expected the Democrats to win control of the House. The French minister in Washington believed that this outcome would make the Lincoln administration amenable to mediation; he proposed that when the result of the elections became known, the British and French should issue a joint “Manifesto” calling for mediation.39 In England, Foreign Secretary Russell also anticipated that Lincoln would cave in if the Democrats achieved “ascendancy” in November. “I heartily wish them success,” Russell added.40

The news of Second Manassas and of Lee’s invasion accelerated the pace of intervention discussions in London and Paris. Benjamin Moran, secretary of the American legation in London, reported that “the rebels here are elated beyond measure” by tidings of Lee’s victory at Manassas. Moran was disgusted by the “exultation of the British press. . . . I confess to losing my temper when I see my bleeding country wantonly insulted in her hour of disaster.” Further word that Lee had invaded Maryland produced in Moran “a sense of mortification. . . . The effect of this news here, is to make those who were our friends ashamed to own the fact. . . . The Union is regarded as hopelessly gone.”41 The French foreign secretary told the American minister in Paris that these events proved “the undertaking of conquering the South is impossible.” The British chancellor of the exchequer, William Gladstone, said that it was “certain in the opinion of the whole world except one of the parties . . . that the South cannot be conquered. . . . It is our absolute duty to recognise . . . that Southern independence is established.”42

Gladstone was not a new convert to this position. The real danger to Union interests came from the potential conversion of Palmerston, who had blocked a parliamentary resolution favoring mediation two months earlier. After Second Manassas, Palmerston appeared ready to change his mind. The Federals “got a very complete smashing,” he wrote to Russell (who was still abroad with Queen Victoria), “and it seems not altogether unlikely that still greater disasters await them, and that even Washington or Baltimore might fall into the hands of the Confederates.” If something like that happened, “would it not be time for us to consider whether . . . England and France might not address the contending parties and recommend an arrangement on the basis of separation?” Russell needed little persuasion. He concurred, and added that if the North refused to accept mediation, “we ought ourselves to recognise the Southern States as an independent State.”43

On September 24 (before news of Antietam arrived in England) Palmerston informed Gladstone of the plan to hold a Cabinet meeting on the subject when Russell returned in October. The proposal would be made to both sides: “an Armistice and Cessation of the Blockades with a View to Negotiation on the Basis of Separation,” to be followed by diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy.44 But Palmerston and Russell agreed to take no action “till we see a little more into the results of the Southern invasion. . . . If the Federals sustain a great defeat . . . [their] Cause will be manifestly hopeless . . . and the iron should be struck while it is hot. If, on the other hand, they should have the best of it, we may wait a while and see what may follow.”45

Great events therefore awaited the outcome of Lee’s decision to cross the Potomac: victory or defeat; foreign intervention; Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation; Northern elections; the very willingness of the Northern people to keep fighting for the Union. “Just now it does appear as if God was truly with us,” wrote Major Walter Taylor, who was closer to Lee at this time than anyone else. “All along our lines the movement is onward.”46 Destiny awaited those tired, ragged, shoeless, hungry but confident Rebel soldiers on the far side of the Potomac as they forded the river singing “Maryland, My Maryland”: the destiny of the Confederacy, of slavery, of the United States itself as one nation, indivisible.