Spongiotic Dermatitis

Spongiotic dermatitis is one of the key patterns of inflammatory skin disease. The fundamental change is that of intercellular edema, producing a separation between keratinocytes. The term spongiosis is most often applied to changes within the epidermis, but there may also be spongiotic folliculitis, spongiosis resulting from rupture of an apocrine duct, and spongiosis involving the intraepidermal portions of eccrine sweat ducts. In early or limited spongiosis, the microscopic findings may be rather subtle, often consisting of a vertical orientation (“stretching”) of keratinocytes with slightly increased prominence of the spinous processes (Fig. 1-1). With progression, exaggerated spaces between keratinocytes may be evident, even on low-power inspection. With increasing intercellular edema, keratinocytes may separate from one another, producing microvesicles or clinically apparent intraepidermal blisters; the prototype condition showing the latter change is acute allergic contact dermatitis, as seen, for example, in rhus (poison ivy) dermatitis (Fig. 1-2). In chronic forms of spongiotic dermatitis, lesions may demonstrate significant acanthosis, with vertically oriented rete ridges producing a resemblance to psoriasis. At this stage, actual spongiotic changes in a given lesion may be subtle or nonexistent (Fig. 1-3).

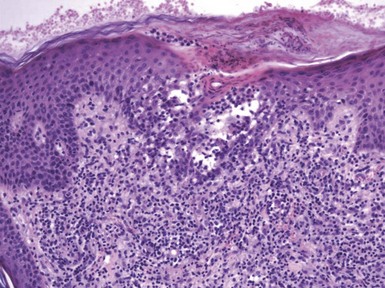

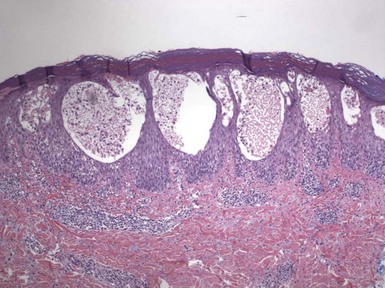

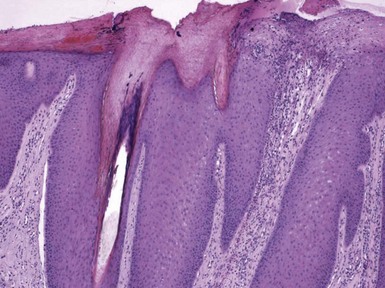

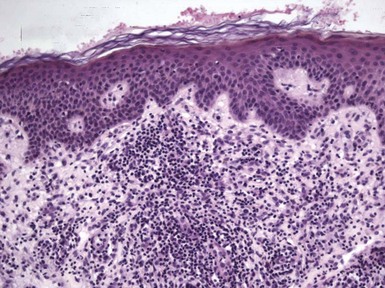

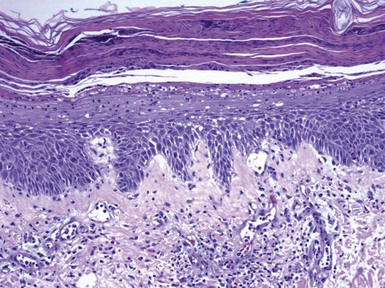

Figure 1-1 Early or mild spongiotic dermatitis.

There is mild intercellular edema, giving a somewhat pale appearance to portions of the epidermis. Slight vertical “stretching” of keratinocytes can also be seen.

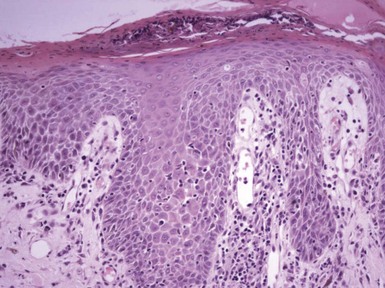

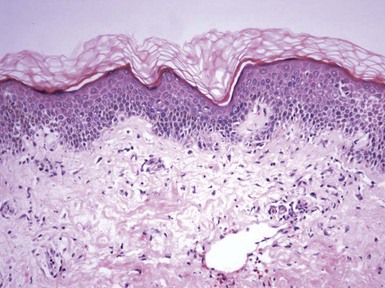

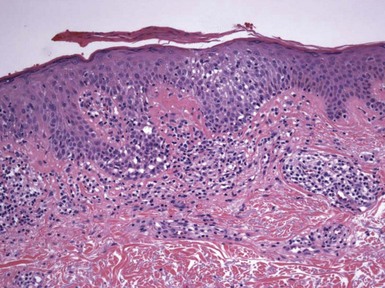

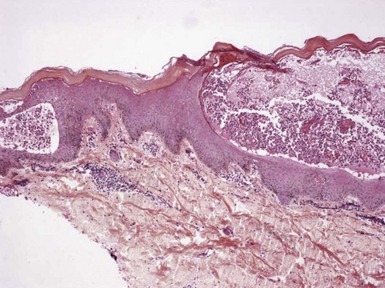

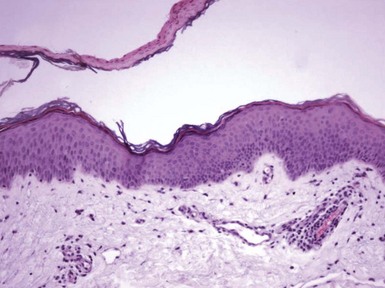

Figure 1-2 Vesicle formation in spongiotic dermatitis.

In this example from a patient with allergic contact dermatitis, marked spongiosis has led to the formation of intraepidermal vesicles that were clinically apparent. There has also been exocytosis of inflammatory cells, which have accumulated within the vesicles.

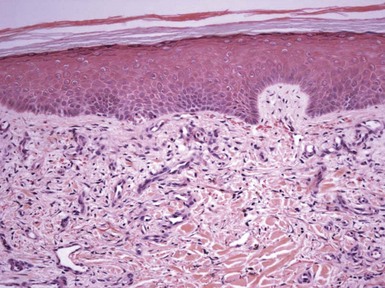

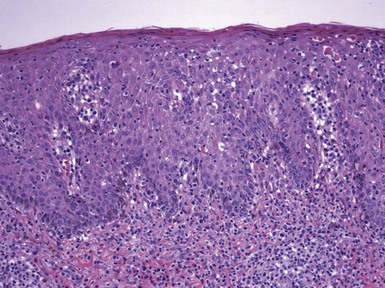

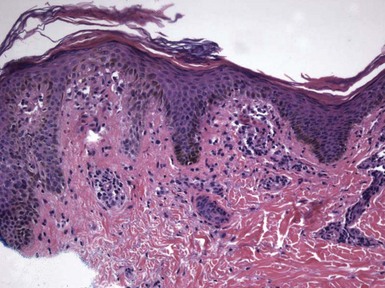

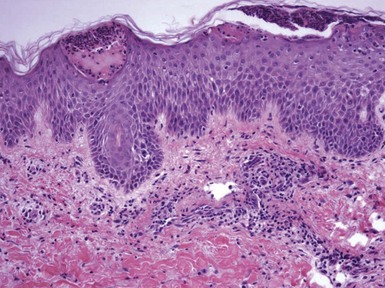

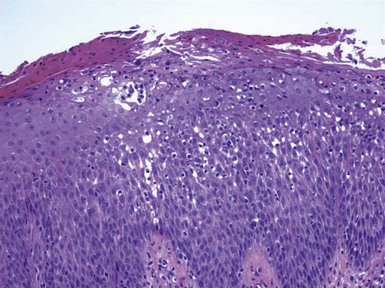

Figure 1-3 Chronic spongiotic dermatitis.

This lesion shows marked acanthosis. There is still evidence of disease activity, as exemplified by the parakeratosis, focal erosion, persistent spongiosis, and exocytosis.

Spongiosis is the hallmark of a category of diseases known as eczematous dermatitis (eczema is derived from a Greek word meaning “boiling over”). Sometimes the term dermatitis alone is used to refer to these disorders, but it has been used for numerous inflammatory skin diseases that may or may not be spongiotic and, therefore, should probably only be used with an appropriate modifier. Clinical conditions in the eczematous category include atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, stasis dermatitis, and some forms of exfoliative dermatitis (erythroderma). Lichen simplex chronicus is often regarded as a chronic form of spongiotic (eczematous) dermatitis. However, spongiosis can be observed to various degrees in a number of other conditions not usually recognized as eczematous dermatoses. Examples include pityriasis rosea, small plaque parapsoriasis, arthropod reactions, miliaria (heat rash), drug reactions, and viral exanthems. In the latter conditions, spongiosis may not be of central importance, and other changes may factor into the diagnosis. This chapter will consider the major forms of spongiotic dermatitis, but spongiosis will be mentioned as a microscopic feature in a number of other conditions, described in other chapters in this book.

Forms of Eczematous Dermatitis

Clinical Features

Contact dermatitis is probably the best understood form of spongiotic (eczematous) dermatitis, mainly because it is the most amenable to controlled studies. It can be experimentally induced and its progress timed rather accurately. Thus, it has served as a model for understanding eczematous processes in general.

Contact dermatitis is divided into two categories: allergic and irritant contact dermatitis. Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV, T-cell–mediated response in an individual who has been sensitized by contact with a particular antigen. These antigens consist of low-molecular-weight substances, called haptens, which combine with host protein to form complete antigens. Epidermal Langerhans cells transport antigen to regional lymph nodes via afferent lymphatics. There, naive T lymphocytes are sensitized, multiply, and circulate through the blood as memory T cells. Later, they may be recruited to the skin via cell surface molecules.1 Cytokines released by lymphocytes largely account for the changes noted clinically and histopathologically.2 There is a significant increase in expression of the cytotoxic granule proteins perforin and granzyme B in dermal infiltrates of allergic contact dermatitis when compared with normal skin and psoriasis.3 A recent study suggests that mast cell production of interleukin-10 may limit the tissue damage associated with contact dermatitis, a finding that is counterintuitive given the known production of proinflammatory mediators by these cells.4

The effects of irritants on the skin are more direct, are not manifestations of cell-mediated immunity, and are more dependent on the type and concentration of the substance involved.5 Generally, skin biopsies are not helpful in distinguishing between irritant and allergic contact dermatitis, because these are typically obtained more than 2 days after the onset of the condition, at which point the microscopic changes are indistinguishable.6,7 However, during the first 24 to 48 hours of response to a contactant, differences between the two reactions may be exploited for purposes of diagnosis under ideal conditions (see later discussion).

In contact dermatitis, pruritus is accompanied by a polymorphous eruption of macules, papules, and/or vesicles. Edema, oozing, and crusting are often present in early lesions. With chronicity, lesions may become dry, scaly, and thickened or lichenified. Moisture and maceration of lesions may be seen in intertriginous areas, and secondary infection sometimes occurs.

Dermatitis produced by irritants is confined to the area exposed to a particular substance, whereas allergic contact dermatitis may involve surfaces not in the immediate area of contact.1 A pattern of dermatitis is sometimes discernible, suggesting the manner in which contact dermatitis occurred and sometimes providing a clue as to the specific etiology. The linear vesicles of rhus (e.g., poison ivy) dermatitis provide one example of this. Chronic forms of contact dermatitis take on the clinical characteristics of lichen simplex chronicus and may be difficult to distinguish from other forms of chronic spongiotic dermatitis. Although topical and systemic corticosteroids are capable of suppressing contact dermatitis reactions and improving existing lesions, identification and removal of the contactant is the key to treating this form of spongiotic dermatitis.

Microscopic Findings

The histopathologic findings of contact dermatitis and, in fact, all the primary forms of spongiotic (eczematous) dermatitis are often subdivided into acute, subacute, and chronic spongiotic stages.8 In the acute phase, intercellular edema within the epidermis results in the development of intraepidermal vesicles and bullae (see Fig. 1-2). Some intracellular edema (ballooning) of keratinocytes is apparent, but this is typically not as pronounced as the intercellular edema and certainly not as striking as in herpesvirus infections, where intracellular edema predominates. Varying degrees of parakeratosis and serous transudation are noted at the epidermal surface. The superficial dermis features edema, vasodilatation, and a perivascular infiltrate comprised mainly of mononucleated cells, especially lymphocytes, but also macrophages and Langerhans cells. Eosinophils are often present but may not be numerous and at times are difficult to demonstrate; the author does not consider their identification necessary to make a diagnosis of contact dermatitis. Lymphocytes extend into the epidermis (exocytosis), and this feature may be particularly pronounced in allergic contact dermatitis (Fig. 1-4). When eosinophils are involved in this process, the term eosinophilic spongiosis is used. The author associates the latter change somewhat more with atopic dermatitis, but it does not have the same diagnostic importance as is the case in immunobullous diseases. In the subacute phase, spongiotic changes are readily apparent but somewhat less pronounced, with formation of microvesicles rather than larger intraepidermal vesicles or bullae. A moderate degree of acanthosis is present, and there may be parakeratosis and a surface crust containing some neutrophils. In the chronic phase, the dermatitis is characterized by marked acanthosis, often associated with hyperkeratosis and hypergranulosis. Thickening of papillary dermal collagen is often noted, with vertical streaking of collagen within the papillae. Spongiosis may be present but is often inconspicuous. Lesions with these features often receive the designation lichen simplex chronicus, a term used for lesions that have been subjected to long-term rubbing or scratching.

It should be pointed out that some authorities do not use the term subacute, preferring to divide the stages of spongiotic dermatitis into acute and chronic types. This results, in part, from the considerable overlap of microscopic findings in dermatitis that has progressed beyond the acute phase.

As discussed previously, a microscopic distinction between irritant and allergic contact dermatitis is usually difficult or impossible—and, certainly, lesions of allergic contact dermatitis can also be irritated! However, some differences between the two may be discerned in biopsies of lesions less than 48 hours old. Strong irritants tend to produce ballooning of superficial keratinocytes, with varying degrees of epidermal necrosis (Fig. 1-5).8,9 According to one study, early biopsies of allergic contact dermatitis were more likely to show follicular spongiosis.10 There may also be differences in dermal fibrin deposition patterns between allergic and irritant contact dermatitis, in that perivascular fibrin deposition in the papillary and reticular dermis is associated with allergic contact dermatitis.11 A new technique called in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy indicates that irritant reactions demonstrate more prominent parakeratosis and greater disruption of the stratum corneum than is the case for allergic reactions.12

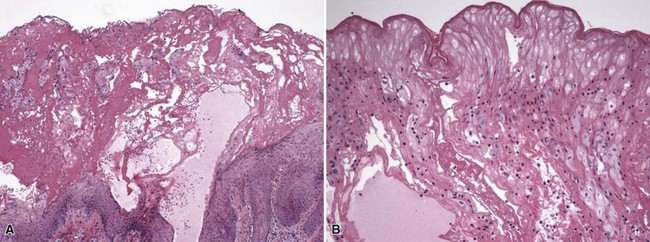

Figure 1-5 Irritant contact dermatitis.

This case occurred from exposure to ethylene oxide. A, Necrotic epidermis forms a surface crust over re-epithelialized epidermis. B, Detail of the necrotic surface, showing “mummified” epidermis that resulted from the ethylene oxide burn. Scattered lymphocytes are also present.

Differential Diagnosis

Contact dermatitis is microscopically difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish from other forms of spongiotic dermatitis, and clinical information is often essential. In working up such cases, special stains for fungal organisms may be useful, in that spongiotic dermatitis is one of the microscopic configurations that accompany dermatophytosis (Fig. 1-6) and candidiasis. Cases with extensive exocytosis may be difficult to separate from mycosis fungoides, particularly because the activated T lymphocytes in chronic contact reactions may demonstrate convoluted nuclei. Aiding in this distinction are the use of published criteria for mycosis fungoides when diagnosing such lesions, such as those proposed by Guitart and colleagues,13 immunohistochemical staining to assess for dropout of selected pan–T-cell antigens, and in some circumstances T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies. However, it must be realized that false-positive gene rearrangement studies may sometimes occur in reactive processes. Forms of chronic spongiotic dermatitis (lichen simplex chronicus) can resemble psoriasis (Fig. 1-7), because the configuration of acanthosis may be quite similar. However, psoriasis is more likely than chronic spongiotic dermatitis to have neutrophilic aggregates in the stratum corneum (Munro microabscesses) or spongiform pustulation in the superficial viable epidermis, thinning of suprapapillary plates, and edematous dermal papillae with tortuous capillaries. In one study comparing nonpustular palmoplantar psoriasis with eczematous dermatitis, the most useful discriminating diagnostic feature favoring psoriasis was the presence of vertically oriented alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis.14

Figure 1-6 Spongiotic dermatitis due to dermatophyte infection.

Numerous hyphae are evident in the stratum corneum.

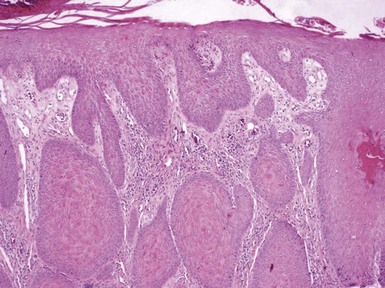

Figure 1-7 Psoriasis with spongiosis.

Spongiotic changes predominate in the lower half of the epidermis. However, there are also confluent parakeratosis with layers of neutrophils, spongiform pustulation of the viable surface epidermis, and dilated papillary dermal vessels—all characteristic features of psoriasis.

Atopic Dermatitis

This form of dermatitis is inherited, although the inheritance pattern is not strictly along mendelian lines. It is often seen in families where there is a history of dermatitis, hay fever, and/or sinusitis. There is clearly an increased risk of atopic dermatitis in children of affected parents, and the majority of cases of atopic dermatitis begin in early childhood.

Criteria for the diagnosis have been developed; among these are the ones reported in a consensus conference on pediatric atopic dermatitis produced by the American Academy of Dermatology.15 Patients must have 3 of 4 major criteria (pruritus, typical morphology and distribution of dermatitis, chronic or chronically relapsing dermatitis, and/or a personal or family history of atopy) and 3 of 22 minor criteria (e.g., elevated serum immunoglobulin E [IgE], early age of onset, Dennie-Morgan infraorbital folds). Erythematous, scaly, papular, and exudative lesions develop over the scalp, neck, and extensor extremities of infants. With advancing age, lesions develop over the face and flexural folds of extremities, and adults often manifest with chronic hand eczema or localized, sometimes coin-shaped lesions (nummular dermatitis). Papular lesions may be folliculocentric. More chronic lesions become thickened with exaggerated skin markings (“lichenified”) and are sometimes designated lichen simplex chronicus. In heavily pigmented patients, lesions may bear a close clinical resemblance to lichen planus.16 Dermatitis is less common in patients who are past middle age. Bacteria, particularly Staphylococcus aureus, may colonize eczematous lesions and contribute to their pathogenesis; some of these strains demonstrate production of exfoliative B toxin.17

Treatments include preventive measures (emollients, avoiding temperature extremes, and sometimes avoidance of selected foods) and therapy with topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors, antihistamines, and short courses of antibiotics. In more severe cases, systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, azathioprine, or phototherapy may be useful.

Microscopic Findings

Biopsy changes in active lesions include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, focal erosions, and surface accumulation of neutrophils with staphylococcal colonization (features associated with infectious eczematoid dermatitis [not confined to atopic individuals]). Follicular spongiosis may also be present. In more chronic lesions, psoriasiform acanthosis, prominent thick-walled dermal vessels, and fibrosis of cutaneous nerves are apparent.18 Hurwitz and DeTrana found that lesions of atopic dermatitis show a characteristic evolution from a perivascular and interstitial spongiotic dermatitis, to a psoriasiform microvesicular configuration, and finally to psoriasiform dermatitis.19 Eosinophils may be present but are usually not prominent. However, the eosinophil product, major basic protein, can be found in lesions and is particularly abundant among those with a history of respiratory atopy.20

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis given for contact dermatitis pertains also to atopic dermatitis. The clinical history, evolution, and distribution of lesions are strongly supportive of the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis. However, this information is not always available, and a microscopic distinction from other forms of spongiotic dermatitis may be difficult or impossible. Nevertheless, atopic dermatitis does differ somewhat from allergic contact dermatitis. In particular, the prominent vesiculation seen in acute allergic contact dermatitis is not generally characteristic of atopic dermatitis, and eosinophils and basophils are more prominent in contact dermatitis.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Clinically, seborrheic dermatitis consists of erythema with yellow, greasy scale, concentrated in the scalp, eyebrows and eyelids, nasolabial folds, and behind the ears. Similar lesions can form in the presternal region, axillae, umbilicus, and groin. It is typical in teenagers and adults, but infants can develop at least two conditions that are considered to be closely related: scalp disease, referred to as cradle cap, and a form of generalized exfoliative dermatitis, referred to as Leiner disease. Seborrheic dermatitis can be particularly severe and show an atypical distribution in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and it can accompany neurologic disorders such as Parkinson disease and stroke.21 Certain drugs, including arsenic, gold, haloperidol, and cimetidine, have been associated with seborrheic dermatitis–like eruptions. A role for Malassezia organisms in the development of seborrheic dermatitis has been postulated, but specific mechanisms have yet to be worked out.

Treatments include topical corticosteroids, antifungal agents, and calcineurin inhibitors.22

Microscopic Findings

Seborrheic dermatitis evolves through the stages of acute, subacute, and chronic spongiotic dermatitis, although the degree of intraepidermal vesiculation seen in acute contact dermatitis is generally not observed. Fully developed lesions tend to display acanthosis that is typically psoriasiform.23 It is possible to identify parakeratosis and scattered neutrophils in the stratum corneum,24 particularly in the vicinity of follicular ostia, as well as spongiosis and lymphocyte exocytosis (Fig. 1-8).

Differential Diagnosis

The chief differential diagnostic problem in seborrheic dermatitis is its distinction from psoriasis. This is not necessarily a difficult task when acanthosis is irregular, suprapapillary plates are not thinned, spongiosis and exocytosis are readily demonstrable, and no spongiform pustules are noted. However, psoriasis that has been traumatized or secondarily eczematized can show considerable histopathologic overlap with seborrheic dermatitis. In such instances, clinical correlation and repeat biopsies may be necessary. Other conditions that can bear a close clinical resemblance to seborrheic dermatitis include dermatophytosis, Norwegian scabies, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the Letterer-Siwi type. However, these can be distinguished microscopically by the finding in tissue sections of fungal hyphae, numerous scabetic organisms, or neoplastic Langerhans cells, respectively.

Stasis Dermatitis

This form of dermatitis appears most often over the lower legs as varying combinations of erythema, induration, scale, and bronze pigmentation. It is particularly prominent medially, superior to the medial malleolus. Presumably, the dermatitis results from a kind of localized nutritional deficiency that results from venous insufficiency. Stasis dermatitis is often complicated by external trauma—rubbing and scratching of pruritic skin—or superimposed allergic contact dermatitis from applications of topical agents. Papular or plaquelike lesions do occur, probably reflecting degrees of vessel proliferation that can be encountered in some cases.

Microscopic Findings

Microscopically, varying stages of spongiotic dermatitis are superimposed on dermal changes that include fibrosis and proliferations of thick-walled vessels throughout the dermis and in the subcutis (Figs. 1-9 and 1-10). Pigment-containing macrophages are readily identified within the dermis; these contain hemosiderin and melanin, as can be demonstrated with stains for iron (Perls, Prussian blue) and melanin (Fontana). Research has recently shown that macrophages can demonstrate nonselective phagocytosis of both hemosiderin and melanin pigments.25

Differential Diagnosis

Stasis dermatitis is distinguished from other forms of spongiotic dermatitis by the vascular and connective tissue changes. Proliferations of thick-walled vessels can predominate to such a degree that there is the suggestion of a vascular tumor (i.e., acroangiodermatitis of the Mali type, so-called pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma).

Other Manifestations of Spongiotic (Eczematous) Dermatitis

This type IV cell-mediated immune reaction is induced by applied substances (photoallergic contact dermatitis) or by systemically administered medications. Examples of the former include sunscreen agents such as benzophenones and certain plants (ragweed), whereas examples of the latter include griseofulvin, sulfonamides, and chlorpromazine. In fact, certain medications can produce both phototoxic and photoallergic reactions. Dermatitis develops in areas of contact with a topical agent that are also exposed to ultraviolet light, or, in the case of systemic agents, in more generalized fashion in all sun-exposed areas. In distinction to phototoxic reactions, photoallergic reactions may spread beyond the area (areas) exposed to ultraviolet light. The lesions themselves are pruritic, sometimes papular, and eczematous. Microscopically, the features are quite similar to those of allergic contact dermatitis, although there may be somewhat deeper dermal extension of the inflammatory infiltrate (see Chapter 12 for further information).26

Pityriasis Alba

This condition consists of hypopigmented, dry patches, often in exposed areas such as the cheeks, shoulders, or upper trunk. This dermatitis is typically more pronounced in dark-skinned individuals. It tends to become more prominent in late summer or fall and may become less pronounced in other seasons of the year. The pigment alteration is a hypopigmenting rather than a depigmenting one, as can be seen with Wood light examination or staining for melanocytes. Lesions often improve with emollients or mild topical corticosteroids. Biopsy changes are often minimal but usually include slight spongiosis, particularly involving hair follicles, a minimal perivascular round cell infiltrate, and occasional lymphocyte exocytosis.27,28 The findings therefore range from slight spongiosis to those of nearly normal skin (Fig. 1-11).

Pompholyx

Pompholyx is typified by the formation of numerous small vesicles that form on the palms, soles, and sides of fingers and toes. Due to the thick stratum corneum in these locations, the vesicles often have a deep-seated appearance, and some observers have likened them to frog spawn or tapioca. Patients may be atopic or have demonstrable contact hypersensitivity, and clinicians have even suspected ingestion of nickel in some cases. Some cases may actually represent autoeczematization (id) reactions (see subsequent discussion). Microscopically, the findings are those of spongiotic dermatitis with intraepidermal vesicle formation. The acrosyringia are not directly involved in the process, as had been implied by the earlier term for this condition—dyshidrosis.29 Later accumulation of neutrophils can produce the changes of pustulosis palmaris and lead to a differential that includes localized forms of pustular psoriasis or dermatophytosis. In the workup of these cases, special staining is advised to exclude the possibility of dermatophyte infection.

Autoeczematization (Id) Reactions

These reactions compose perhaps one of the least understood phenomena in clinical dermatology. In this reactions, papules or vesicles develop in sites distant (sometimes remote) from an area of inflammation or infection. Classic examples are vesicular eruptions on the sides of the fingers in patients with inflammatory tinea pedis and papular or papulovesicular lesions following allergic contact dermatitis superimposed on stasis dermatitis. The author has also observed papular eruptions in patients with extensive rhus contact dermatitis who have been treated with inadequate tapered courses of systemic corticosteroids.

Commonly called id reactions, these lesions are frequently named for the underlying infection or other condition from which they derive; thus, there are dermatophytids, bacterids, pintids, eczematids, and even leukemids. When derived from a distant focus of infection, ids are culture negative (whereas the primary source of infection is positive), have no organisms demonstrable on special staining, and resolve with treatment of the primary infection. Presumably, ids are T-cell–mediated disorders, and some data support this assertion.30 On biopsy, vesicular ids show spongiosis with intraepidermal vesicle formation, thus meeting criteria for acute spongiotic dermatitis (Fig. 1-12).31 Usually a degree of papillary dermal edema and a superficial perivascular round cell infiltrate, composed mainly of lymphocytes, are present. Papular ids typically show a lesser degree of spongiosis, and therefore the microscopic features are rather nonspecific, falling into a differential diagnosis that can range from forms of urticaria to drug reactions, viral exanthems, and arthropod reactions (Fig. 1-13). A purpuric variant also displays extravasated erythrocytes, although without changes of true vasculitis.

Exfoliative Dermatitis (Erythroderma)

Erythroderma and exfoliative dermatitis are terms that are often used interchangeably. Most examples of erythroderma are associated with increased scale and exfoliation, but there are examples of erythroderma in which scale is not a prominent feature, including the “red man syndrome” due to vancomycin or other drugs or sometimes associated with lymphoma. There are also conditions with widespread scaling in which erythema is not pronounced, such as some of the ichthyoses. Exfoliative dermatitis can develop as a systemic response (e.g., to a drug or lymphoma [most noteworthy, in the form of Sézary syndrome]), can be idiopathic, or can result from generalization of a primary cutaneous disease. Thus, psoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, seborrheic dermatitis, or even allergic contact dermatitis have been associated with an exfoliative dermatitis, and congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma is an inherited form of ichthyosis that is virtually by definition an exfoliative dermatitis.

Treatment is directed toward the underlying cause of exfoliation, including, when relevant, the underlying primary dermatosis.

Microscopic Findings

Most cases show a relative hypokeratosis with parakeratosis, a diminished granular layer, acanthosis that is often psoriasiform (even in those cases not due to psoriasis), and some degree of spongiosis. Vasodilatation and a perivascular round cell infiltrate are often observed. This image unfortunately provides few clues as to the specific diagnosis. However, occasionally specific features may point to an underlying dermatosis, such as alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis (pityriasis rubra pilaris), spongiform pustules (psoriasis), or atypical lymphoid cells with epidermotropism or Pautrier microabscesses (Sézary syndrome).32 Unfortunately, eosinophils can be found in exfoliative cases unrelated to drugs (even in some examples of Sézary syndrome). The author has seen lichenoid tissue changes in examples of exfoliative dermatitis, and a number of these cases have proven to be drug-related (see Chapter 3, Psoriasiform and Lichenoid Dermatitis) (Fig. 1-14).33

Differential Diagnosis

As mentioned, the major challenge in these cases is to find a specific primary dermatosis that might underlie the exfoliative dermatitis. Otherwise, the features often resemble other forms of spongiotic (eczematous) dermatitis. Those examples showing a lichenoid tissue reaction can closely resemble erythema multiforme, and therefore clinical data are essential in such cases.

Prurigo Simplex, Lichen Simplex Chronicus, and Prurigo Nodularis

To varying degrees, three conditions represent a cutaneous response to pruritus. Prurigo simplex, the least specific of the three, is manifested by erythematous papules, sometimes papulovesicles, located over the trunk and extensor surfaces of extremities. Often there is an eroded surface, usually the consequence of excoriation. The cause is frequently difficult to determine, but reaction to arthropod or papular forms of spongiotic dermatitis (papular eczema) are among the possibilities. Lichen simplex chronicus is a change that results from chronic rubbing or other forms of irritation to the skin, resulting in thickening of the epidermis and superficial dermis. Clinically, the lesions are often well demarcated and show exaggerations of normal skin markings; hyperpigmentation often accompanies the process. A variety of forms of spongiotic dermatitis may underlie this change. Typical locations include wrists, ankles, and posterior neck. In individuals with atopic dermatitis, lichenification can be found in other flexural areas, such as antecubital fossae, with a degree of bilateral symmetry. Prurigo nodularis is characterized by the development of discrete nodules, sometimes in linear fashion, and particularly over the extremities. Lesions are often hyperpigmented. They are association with paroxysms of pruritus, which can be particularly elicited by stress.

The mainstays of treatment are topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines. Psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy has been used in prurigo simplex and prurigo nodularis, and agents such as cyclosporine and thalidomide have been used in recalcitrant cases of prurigo nodularis.

Microscopic Findings

The histopathology of prurigo simplex is nonspecific, and it includes spongiosis, with or without surface erosion, as well as a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, usually with eosinophils. Follicular and perifollicular spongiosis have predominated in some studies.34 The microscopic features of lichen simplex chronicus include orthokeratosis, often with formation of a stratum lucidum—a horizontal, pale blue zone of stratum corneum immediately above the granular cell layer. This phospholipid-rich zone generally occurs only in the palms and soles, and its appearance elsewhere is a good presumptive clue to lichen simplex chronicus (Fig. 1-15). The granular cell layer is typically prominent. There is vertically oriented acanthosis with exaggeration of the rete ridge pattern, often mimicking psoriasis, although the acanthosis may be quite irregular. Vertically oriented thickening of papillary dermal collagen (“vertical streaking”) is usually observed, and there is a perivascular round cell infiltrate of varying intensity in the superficial dermis.35 Lichen simplex chronicus may be the only finding on biopsy, or it may coexist with another dermatosis, in which case its features may intermingle with or be found adjacent to the lesion. For example, changes of lichen simplex chronicus are often associated with verrucae or squamous cell carcinomas, the latter finding being particularly common on the dorsa of the hands or over the lower legs. Prurigo nodularis displays pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, superficially resembling squamous cell carcinoma but without significant keratinocyte atypia (Fig. 1-16). This may be accompanied by varying degrees of erosion or scale crusting (although only orthokeratosis may be seen in many cases), thickening of papillary dermal collagen, and lymphocytic perivascular inflammation (Fig. 1-17). Changes of lichen simplex chronicus are sometimes identified at the periphery of foci of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Hyperplasia of dermal nerves has been emphasized as an essential feature of prurigo nodularis and can be demonstrated with antibodies to S-100 protein and other neural stains.36,37

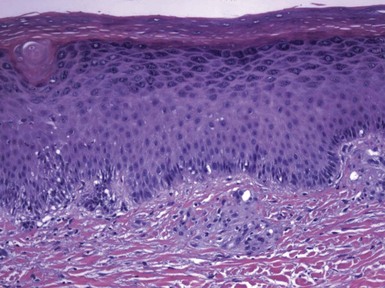

Figure 1-15 Lichen simplex chronicus.

Orthokeratosis is associated with stratum lucidum formation. Hypergranulosis, marked acanthosis, vertical streaking of papillary dermal collagen, and vasodilatation with a perivascular round cell infiltrate are also apparent. This particular example also shows a degree of papillomatosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Prurigo simplex can be readily distinguished from dermatitis herpetiformis (a clinical mimic) by its lack of papillary neutrophilic microabscesses and negative or nonspecific direct immunofluorescence findings. Among other somewhat similar clinical conditions, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) shows combinations of vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer, exocytosis with keratinocyte necrosis, and/or an underlying wedge-shaped dermal inflammatory infiltrate. In addition, Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis) displays epidermal acantholysis, often with the features of focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. The microscopic differential diagnosis of lichen simplex chronicus often includes psoriasis, and at times a distinction can be quite difficult. A typical plaque of psoriasis should show parakeratosis, accumulations of neutrophils in the stratum corneum (Munro microabscesses) or in the superficial spinous layer (spongiform pustules), thinning of suprapapillary plates, and edematous dermal papillae containing “tortuous” capillaries—changes not seen in lichen simplex chronicus. However, biopsied lesions of psoriasis may have been partly treated or become secondarily lichenified, in which case classic changes may be subtle or entirely absent. Pathologists should request that, whenever possible, biopsies to rule out psoriasis be obtained from lesions that show minimal secondary change or are located in hard-to-reach areas. In addition to well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, prurigo nodularis should be distinguished from keratoacanthoma, but the latter lesions have a well-developed keratin-filled crater with a buttressing arrangement of the adjacent epidermis, glassy-appearing cytoplasm, and often intraepidermal neutrophilic abscesses. Other forms of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia that can be mimics include halogen reactions (bromoderma, iododerma), although these often show pronounced dermal edema and a neutrophilic infiltrate that may be folliculocentric, or a group of chronic cutaneous infections, the prototype of which is North American blastomycosis. Lesions that show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia together with suppuration and/or granulomatous inflammation should raise suspicions for infection, and special staining for organisms is in order.

Other Conditions for which Spongiosis Is a Microscopic Hallmark

Clinical Features

Miliaria, the medical term for heat rash, results from obstruction of eccrine sweat ducts at varying levels and to varying degrees. Two forms are of common importance histopathologically: miliaria crystallina and miliaria rubra. In miliaria crystallina, there is either occlusion or disruption of the intracorneal (superficial) portion of the eccrine sweat duct, resulting in the formation of small, clear vesicles near the epidermal surface.38 These particularly arise in the setting of febrile illnesses or following sunburn. Due to the superficial nature of the condition, the vesicles rupture easily, and resolution is quick once the cause has been removed. In miliaria rubra, the occlusion or disruption has occurred in deeper levels of the epidermis, resulting in the formation of itchy red papules; pustules can develop later in these lesions (miliaria pustulosa). Sweating with prolonged occlusion is usually the precipitating cause, and lesions may be seen on the back in truck drivers or under sweat bands.

Microscopic Findings

Biopsies are rarely obtained of these lesions, because the diagnosis is usually apparent clinically. However, sometimes changes of miliaria are found incidentally in biopsies obtained for other reasons. An intracorneal or subcorneal vesicle overlying the intraepidermal sweat duct is evident in miliaria crystallina (Fig. 1-18),39 whereas spongiotic intraepidermal vesicles that, on levels, appear to be associated with deeper portions of intraepidermal sweat ducts are characteristic of miliaria rubra. Exocytosis of inflammatory cells is apparent, especially in pustular lesions (Fig. 1-19).40 Papillary dermal edema and subepidermal vesiculation under these circumstances would indicate a more profound degree of sweat gland occlusion—hence the term miliaria profunda.

Differential Diagnosis

The targeting of acrosyringia in the various forms of miliaria makes the microscopic findings rather distinctive, but when miliaria coexists with other dermatoses, recognizing its changes can be a challenge. Fox-Fordyce disease (apocrine miliaria) differs in that the apocrine duct is part of the primary epithelial germ apparatus, and therefore follicular plugging and spongiosis are often the predominant microscopic features.

Small Plaque Parapsoriasis (Guttate Parapsoriasis, Digitate Dermatosis, Chronic Superficial Dermatitis, Xanthoerythrodermia Perstans)

This is a troublesome diagnostic entity because of the wide variety of clinical terms (reflecting the variability in clinical appearance of the lesions), the nonspecific microscopic changes, and the opinion (held by some) that this may be an abortive or precursor lesion of mycosis fungoides. Clinically, there are discrete, reddish brown to yellow patches, with fine scale distributed over the trunk and proximal extremities. These patches may take the form of drop-shaped (guttate) lesions; small plaques; or elongated, finger-shaped lesions. Researchers have found that they tend to be persistent but relatively asymptomatic and have described the occurrence of spontaneous regression.41 Others have detected T-cell receptor gene rearrangements in some cases, raising the aforementioned possibility of lymphoma,42 and in fact evolution to mycosis fungoides reportedly occurs in lesions termed small plaque parapsoriasis. However, it is not clear whether these cases might have represented parapsoriasis en plaque (a known precursor—or early stage—of mycosis fungoides) with smaller lesions.43 In the author’s view, the ultimate categorization of this group of lesions vis-à-vis lymphoma remains in doubt.

Microscopic Findings

Microscopically, changes are mild and nonspecific but include parakeratosis,44 which may be confluent along the length of the biopsy specimen (Fig. 1-20); mild to moderate acanthosis; spongiosis; and a slight perivascular inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and a few macrophages. These features are difficult to distinguish from other mild forms of spongiotic dermatitis,45 but they are distinct from true psoriasis and do not meet microscopic criteria for mycosis fungoides.

Figure 1-20 Small plaque parapsoriasis (digitate dermatosis).

There is a confluent band of parakeratosis. The underlying epidermis is only slightly acanthotic, and a trace of spongiosis is suggested by vertical orientation of the nuclei in the left side of the figure. There is also a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.

Differential Diagnosis

In the author’s experience, an accurate diagnosis of the “small plaque parapsoriasis” group of disorders relies heavily on clinicopathologic correlation. The microscopic features alone can closely resemble low-grade forms of spongiotic dermatitis or pityriasis rosea (see later discussion).

Pityriasis Rosea

This is a classic dermatologic disease, seen predominantly in younger individuals, with a distinctive clinical presentation and a histopathologic image that is characteristic, if not pathognomonic. It consists of an eruption of oval, salmon-colored, sometimes pruritic patches with “cigarette paper” wrinkling and a collarette of scale, which is usually distributed over the trunk and proximal extremities, although “inverse” distributions are sometimes reported. The eruption often begins with the development of a single lesion that may prove to be larger than subsequent ones, called a herald patch. Lesions last for up to 6 to 8 weeks and then resolve. Uncommonly (in about 2% of patients), there can be recurrences.46 The manner of evolution of this disease has long suggested a viral etiology. This has not yet been proven, although a role for human herpesviruses 6 and 7 has been proposed, and in a recent study 7 of 34 skin specimens were positive for human herpesvirus 8 DNA sequences using polymerase chain reaction methods.47 Pityriasis rosea–like drug eruptions have been reported with agents such as gold, captopril, and clonidine.

Treatments have included emollients and antipruritic lotions and ultraviolet therapy.

Microscopic Findings

The microscopic features include acanthosis that is typically mild to moderate, with focal spongiosis (Fig. 1-21). Uncommonly, spongiotic vesicles can develop, and a rare “vesicular” pityriasis rosea has been reported. Parakeratosis tends to occur in discrete foci, called parakeratotic mounds (Fig. 1-22). There is a mild lymphocytic infiltrate around papillary dermal vessels, and extravasated erythrocytes can be identified in the dermal papillae (Fig. 1-23). Apoptotic keratinocytes are sometimes observed in older lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

A specific diagnosis of pityriasis rosea is sometimes possible, even in the absence of a clinical history, if all the characteristic microscopic features are present, but otherwise the changes could suggest a variety of mild forms of spongiotic dermatitis. The author agrees with the view of Ackerman that the superficial variant of erythema annulare centrifugum can have a close microscopic resemblance to pityriasis rosea, and even a clinical resemblance, at least in terms of the individual lesions. The finding of plasma cells should prompt a consideration of syphilis (a definite clinical mimic), and special staining and/or serologic studies may be advisable.

Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy (Pruritic Urticarial Papules and Plaques of Pregnancy)

Some authors prefer the term polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP) for this and other conditions that historically have been classified separately but share the combination of a pruritic eruption and pregnancy.48 In this disorder, urticarial papules and plaques develop, particularly over the abdomen and proximal lower extremities, and involvement of striae is common. Lesions on distal extremities are not typical but may occur. The eruption begins in the third trimester, most often during the first pregnancy, and only uncommonly recurs. Although it usually resolves with delivery, the author has occasionally seen late-onset disease that has continued several weeks after a pregnancy. The eruption has no adverse long-term effect on mother or fetus, but the pruritus can be extremely troubling, and of course treatment options are limited to antihistamines such as diphenhydramine or antipruritic lotions.

Microscopic Findings

On biopsy, PEP often shows a superficial perivascular infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, macrophages, and usually some eosinophils. There may be minimal if any acanthosis or spongiosis (Fig. 1-24), but occasionally spongiotic changes are sufficiently pronounced to produce clinically apparent vesicles (Fig. 1-25).49,50 Within the context of a pregnancy, this can actually prove to be a reasonably diagnostic constellation of findings.51,52

Differential Diagnosis

The most significant differential diagnostic consideration is pemphigoid gestationis, which tends to occur late in pregnancy; this condition occurs as urticarial lesions and is quite pruritic. However, pemphigoid gestationis begins during the second trimester, often presents with bullae (vesicles may occur in PEP, but these are small and form on the basis of spongiosis), may continue following delivery (the author has seen pemphigoid gestationis continue for up to a year following parturition), and recurs with succeeding pregnancies.

Typically, papillary dermal edema and subepidermal blister formation, along with the spongiosis, also occur. Direct immunofluorescent studies are particularly helpful in this situation, because pemphigoid gestationis shows linear C3 and, sometimes, IgG deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction, whereas the changes in PEP are negative or nonspecific.

References

1. Streit, M, Braathen, LR. Contact dermatitis: clinics and pathology. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:309–314.

2. Krueger, GG. Lymphokines in health and disease. Int J Dermatol. 1977;16:539–551.

3. Yawalkar, N, Hunger, RE, Buri, C, et al. A comparative study of the expression of cytotoxic proteins in allergic contact dermatitis and psoriasis: spongiotic skin lesions in allergic contact dermatitis are highly infiltrated by T cells expressing perforin and granzyme B. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:803–808.

4. Grimbaldeston, MA, Nakae, S, Kalesnikoff, J, et al. Mast cell-derived interleukin 10 limits skin pathology in contact dermatitis and chronic irradiation with ultraviolet B. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1095–1104.

5. Hall, JH, Smith, JG, Jr., Burnett, SC. The lysosome in contact dermatitis: a histochemical study. J Invest Dermatol. 1967;49:590–594.

6. Bauer, A, Rodiger, C, Greif, C, et al. Vulvar dermatoses—irritant and allergic contact dermatitis of the vulva. Dermatology. 2005;210:143–149.

7. Rietschel, R, Fowler, JF, Jr. Histology of contact dermatitis. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis, 4th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1995. [38-40].

8. Taylor, RM. Histopathology of contact dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 1986;4:18–22.

9. Nater, JP, Baar, AJ, Hoedemaeker, PJ. Histological aspects of skin reactions to propylene glycol. Contact Dermatitis. 1977;3:181–185.

10. Vestergaard, L, Clemmensen, OJ, Sorensen, FB, et al. Histological distinction between early allergic and irritant patch test reactions: follicular spongiosis may be characteristic of early allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:207–210.

11. Beutner, EH, Rudzki, E, Chorzelski, TP, et al. Differentiation of allergic from irritant contact dermatitis by dermal fibrin deposition patterns. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;21:198–200.

12. Swindells, K, Burnett, N, Rius-Diaz, F, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy may differentiate acute allergic and irritant contact dermatitis in vivo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:220–228.

13. Guitart, J, Kennedy, J, Ronan, S, et al. Histologic criteria for the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides: proposal for a grading system to standardize pathology reporting. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:174–183.

14. Aydin, O, Engin, B, Oguz, O, et al. Non-pustular palmoplantar psoriasis: is histologic differentiation from eczematous dermatitis possible? J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:169–173.

15. Eichenfield, LF, Hanifin, JM, Luger, TA, et al. Consensus conference on pediatric atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1088–1095.

16. Summey, BT, Bowen, SE, Allen, HB. Lichen planus-like atopic dermatitis: expanding the differential diagnosis of spongiotic dermatitis. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:311–314.

17. Capoluongo, E, Giglio, AA, Lavieri, MM, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated in subjects with atopic dermatitis. Higher prevalence of exfoliative B toxin production in lesional strains and correlation between the markers of disease intensity and colonization density. J Dermatol Sci. 2001;26:145–155.

18. Soter, NA, Mihm, MC, Jr. Morphology of atopic eczema. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1980;92:11–15.

19. Hurwitz, RM, DeTrana, C. The cutaneous pathology of atopic dermatitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:544–551.

20. Leiferman, KM, Ackerman, SJ, Sampson, HA, et al. Dermal deposition of eosinophil-granule major basic protein in atopic dermatitis. Comparison with onchocerciasis. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:282–285.

21. Naldi, L, Rebora, A. Seborrheic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:387–396.

22. Schwartz, RA, Janusz, CA, Janniger, CK. Seborrheic dermatitis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:125–130.

23. Barr, RJ, Young, EM, Jr. Psoriasiform and related papulosquamous disorders. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:412–425.

24. Pinkus, H, Mehregan, AH. The primary histologic lesion of seborrheic dermatitis and psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 1966;46:109–111.

25. Rivera, MR, Ishihara, M, Mihara, M. A case of non-selective phagocytosis of hemosiderin and melanin of dermal histiocytes in stasis dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295:19–23.

26. Willis, I, Kligman, AM. The mechanism of photoallergic contact dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 1968;51:378–384.

27. Vargas-Ocampo, F. Pityriasis alba: a histologic study. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:870–873.

28. In, SI, Yi, SW, Kang, HY, et al. Clinical and histopathological characteristics of pityriasis alba. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:591–597.

29. Kutzner, H, Wurzel, RM, Wolff, HH. Are acrosyringia involved in the pathogenesis of “dyshidrosis”? Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:109–116.

30. Kasteler, JS, Petersen, MJ, Vance, JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795–798.

31. Khanna, M, Qasem, K, Sasseville, D. Allergic contact dermatitis to tea tree oil with erythema multiforme-like id reaction. Am J Contact Dermat. 2000;11:238–242.

32. Nicolis, GD, Helwig, EB. Exfoliative dermatitis. A clinicopathologic study of 135 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:788–797.

33. Patterson, JW, Berry, AD, III., Darwin, BS, et al. Lichenoid histopathologic changes in patients with clinical diagnoses of exfoliative dermatitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:358–364.

34. Uehara, M, Ofuji, S. Primary eruption of prurigo simplex subacuta. Dermatologica. 1976;153:49–56.

35. Kouskoukis, CE, Scher, RK, Ackerman, AB. The problem of features of lichen simplex chronicus complicating the histology of diseases of the nail. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:45–49.

36. Mattila, JO, Vornanen, M, Katila, ML. Histopathological and bacteriological findings in prurigo nodularis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:49–51.

37. Lee, MR, Shumack, S. Prurigo nodularis: a review. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:211–218. [quiz 219-220].

38. Shuster, S. Duct disruption, a new explanation of miliaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:1–3.

39. Shelley, WB, Horvath, PN. Experimental miliaria in man: production of sweat retention anidrosis and miliaria crystallina by various kinds of injury. J Invest Dermatol. 1950;14:9–20. [[illustr]].

40. Holzle, E, Kligman, AM. The pathogenesis of miliaria rubra. Role of the resident microflora. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:117–137.

41. Lambert, WC, Everett, MA. The nosology of parapsoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:373–395.

42. Belousova, IE, Vanecek, T, Samtsov, AV, et al. A patient with clinicopathologic features of small plaque parapsoriasis presenting later with plaque-stage mycosis fungoides: report of a case and comparative retrospective study of 27 cases of “nonprogressive” small plaque parapsoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:474–482.

43. Samman, PD. The natural history of parapsoriasis en plaques (chronic superficial dermatitis) and prereticulotic poikiloderma. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:405–411.

44. Ackerman, AB, Jones, RE, Jr. Making chronic nonspecific dermatitis specific. How to make precise diagnoses of superficial perivascular dermatitides devoid of epidermal involvement. Am J Dermatopathol. 1985;7:307–323.

45. Hu, CH, Winkelmann, RK. Digitate dermatosis. A new look at symmetrical, small plaque parapsoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:65–69.

46. Parsons, JM. Pityriasis rosea update: 1986. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:159–167.

47. Prantsidis, A, Rigopoulos, D, Papatheodorou, G, et al. Detection of human herpesvirus 8 in the skin of patients with pityriasis rosea. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:604–606.

48. Medenica, L, Vesic, S, Sretenovic-Vukicevic, J. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy—new classification and differential diagnosis. Med Pregl. 2008;61:586–590. [[in Serbian]].

49. Faber, WR, van Joost, T, Hausman, R, et al. Late prurigo of pregnancy. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:511–516.

50. High, WA, Hoang, MP, Miller, MD. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy with unusual and extensive palmoplantar involvement. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1261–1264.

51. Lawley, TJ, Hertz, KC, Wade, TR, et al. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. JAMA. 1979;241:1696–1699.

52. Callen, JP, Hanno, R. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP). A clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:401–405.