Cutaneous Appendageal Tumors

TUMORS WITH HAIR FOLLICLE DIFFERENTIATION

Benign Nongerminative Follicular Neoplasms

Dilated Pore of Winer and Pilar Sheath Acanthoma

Tumor of the Follicular Infundibulum

Proliferating Trichilemmal Cyst (Benign Proliferating Trichilemmal Tumor)

Benign Follicular Neoplasms with Germinative-Type Differentiation

Neoplasms with Differentiation Toward Follicular Mesenchyme

Pseudoneoplastic Sebaceous Proliferations

Tumors with Hair Follicle Differentiation

The hair follicle is a microscopically complex structure, and, correspondingly, it is not surprising that classification schemes for lesions showing follicular differentiation are numerous and similarly complex—particularly to students who are approaching the subject for the first time. For the purposes of this chapter, the author will categorize these lesions according to their predominant lines of differentiation: outer root sheath epithelium (nongerminative), germinative epithelium, follicular mesenchyme with or without an epithelial component, and malignant pilar neoplasms. Several nevoid lesions of hair follicles will also be discussed. It will also be seen that varying degrees of differentiation toward follicular epithelium can be observed in the nonmalignant pilar lesions. Thus, the epithelial elements of hair follicle nevi bear a close resemblance to normal follicles, and the same can be said of dilated pore of Winer, trichofolliculoma, and trichogenic trichoblastoma. On the other hand, the epithelial structures in proliferating trichilemmal tumor, pilomatricoma, and trichogerminoma (trichoblastoma) may be barely recognizable as having any association with hair follicles whatsoever. In addition to the better delineated adnexal tumors, there are also benign and malignant neoplasms with mixed differentiation that may show as one element a degree of follicular differentiation. Such tumors are difficult to classify but appear from time to time, especially in a busy consultation practice.

Nevoid Follicular Lesions

Clinical Features: Hair follicle nevi, or congenital vellus hamartomas, are considered malformations rather than neoplasms. They are found most often in young individuals and tend to arise in the head and neck regions.1–4 There are multiple flesh-colored papules that sometimes coalesce, ranging from 1 to 5 mm in diameter. They can be associated with either hypertrichosis or alopecia. Linear lesions are sometimes noted, being distributed along Blaschko lines.5 One example is associated with frontonasal dysplasia.6 Note that the so-called “wooly hair nevus” of the scalp is composed of structurally abnormal hair shafts but otherwise lacks significant histopathologic abnormalities in the underlying skin.7

Microscopic Findings: There are collections of small follicular structures, usually displayed in cross-sectional profiles. They have the usual structural characteristics of vellus follicles, although some may have a slightly immature appearance.1–4 Basement membranes are inconspicuous, and the follicles are surrounded by ordinary-appearing connective tissue.

Differential Diagnosis: Facial biopsies sectioned tangentially, particularly when obtained from younger individuals, may give the impression of increased numbers of small vellus follicles but still be within the range of normal. The observation that some of the follicles in a lesion are developmentally immature should lead to the consideration of a hair follicle nevus. Hamartomas with a hair follicle component, such as the common accessory tragus and the uncommon rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma, have some of the features of hair follicle nevus and may represent part of a spectrum of lesions. However, these also have distinctive connective tissue components. Goldenhar syndrome is an uncommon condition that combines accessory tragi with malar, maxillary, or mandibular hypoplasia; epibulbar dermoids; and numerous other anomalies.8 The epibulbar dermoid is regarded as an example of choristoma—a benign congenital overgrowth of abnormally located tissue. In this case, the tissue composing the epibulbar dermoid is almost a perfect mimic of skin. The microscopic findings of epibulbar dermoid and accessory tragus in the same individual can lead to a reasonably confident diagnosis of Goldenhar syndrome.

Unlike the hair follicle nevus, trichofolliculoma features a central dilated follicle from which branch numerous secondary follicles in a radial arrangement. Nevus comedonicus contains dilated follicles filled with keratin and showing irregular proliferations of their walls; connections to the surface epidermis are readily identified. In earlier texts, pigmented hair nevus, also known as Becker nevus, was sometimes included as a type of hair follicle nevus. Although this lesion features prominent hypertrichosis, the follicles themselves have a mature appearance and are not clustered but widely dispersed within these radially extensive lesions. Furthermore, the epidermis features acanthosis with pointed rete ridges and basilar hypermelanosis, and an association with connective tissue nevus or smooth muscle hamartoma is sometimes demonstrable.

Basaloid Follicular Hamartoma

Clinical Features: Basaloid follicular hamartoma is a pilar-related tumor that has been variously interpreted as a malformation or as a neoplasm. It may be seen in one of four clinical settings: as a sporadic solitary papule, as a plaque on the scalp with associated alopecia, as a group of linear papules, and as a group of generalized papules in patients with autoimmune conditions such as myasthenia gravis and lupus erythematosus.9 Lesions range from 1 to 5 mm in diameter, are flesh colored, and can be encountered in individuals of all ages; multiple lesions in children are usually associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.10,11

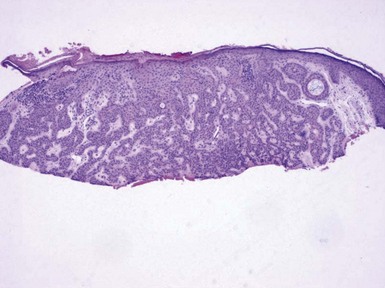

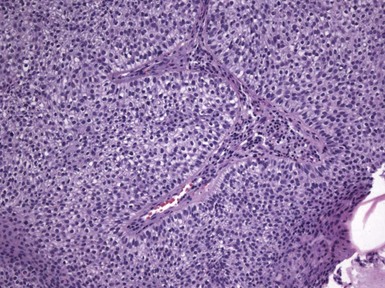

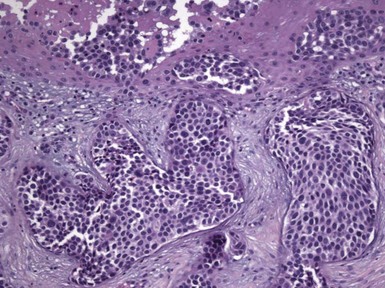

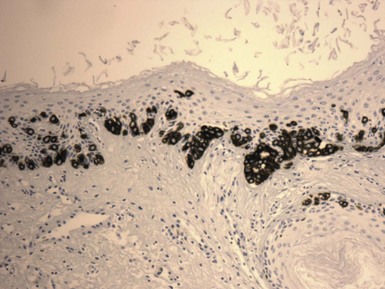

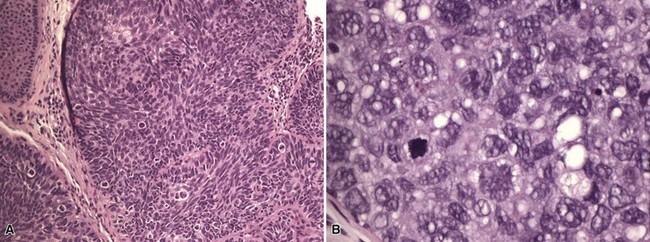

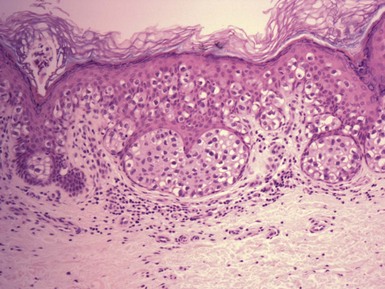

Microscopic Findings: Basaloid follicular hamartomas show anastomosing cords and strands of cytologically bland basaloid or polygonal cells, attached to basilar epidermis or hair follicles12,13 (Fig. 19-1). Apoptosis is uncommon, and mitotic figures are usually absent. Clefting artifact or myxoid stromal changes, as seen in basal cell carcinomas, are not evident. Structures suggesting follicular bulbs and papillary mesenchymal bodies can be observed.14

Differential Diagnosis: The chief differential diagnostic considerations are superficial basal carcinoma with a fronded or reticulated configuration and the infundibulocystic variant of basal cell carcinoma. The latter can also be multifocal and occur as a genodermatosis.15 However, as mentioned previously, mitotic activity, stromal retraction, and mucinous connective tissue are features of basal cell carcinoma that are not seen in basaloid follicular hamartoma. In a recent report, the authors were able to differentiate nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome from basaloid follicular hamartoma genetically, confirming the former by finding a novel PTCH1 germline mutation.16 The view has been expressed that basaloid follicular hamartoma may be a variant of trichoepithelioma.17 The classic form of the latter lesion has a more nodular configuration, and papillary mesenchymal bodies are more readily identified. However, a recent study of CD34, BCL2, and CD10 expression showed similarities among trichoepithelioma, the lesions of generalized basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome, and two other benign lesions—vellus hair hamartoma and neurofollicular hamartoma.18 There is also some resemblance to tumor of the follicular infundibulum. However, that tumor has a more platelike growth beneath the epidermis, although with connections to the epidermal surface, and the constituent cells are more squamoid in appearance.19 With regard to immunohistochemical staining, basaloid follicular hamartomas show CD34 positivity around the epithelial strands and have a low proliferative index via Ki-67 staining, in contrast to basal cell carcinomas.

Benign Nongerminative Follicular Neoplasms

Dilated Pore of Winer and Pilar Sheath Acanthoma

Clinical Features: The dilated pore of Winer presents as a large open comedo on the face or trunk, particularly in elderly individuals.20 These lesions are only of cosmetic concern. An association with nevus comedonicus and other follicular tumors has been reported.21 The pilar sheath acanthoma is usually found on the face, particularly above the upper lip, and presents as a nodule with a central keratin plug. Both lesions are effectively removed by simple excision.

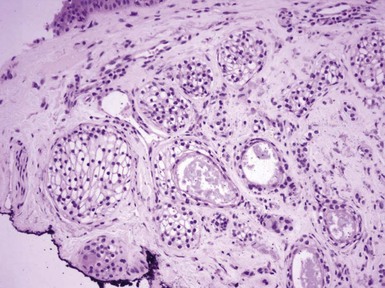

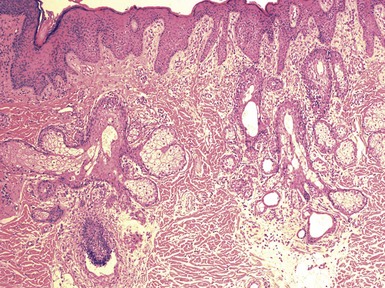

Microscopic Findings: The dilated pore consists of a keratin-filled, epithelial-lined cyst or sinus surrounded by mildly proliferative, budding epithelium. The resemblance to a follicular unit is supported by the occasional presence of sebaceous glands or vellus hairs (Fig. 19-2). Pilar sheath acanthoma shows a cystically dilated, infundibulum-like pore surrounded by markedly proliferative, lobulated epithelium (Fig. 19-3). The constituent cells are either polyhedral, with pale eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm, or basaloid, thereby having a resemblance to outer root sheath epithelium. The findings in these two lesions strongly suggest that they are closely related, probably representing points within the same pathologic spectrum.

Differential Diagnosis: The clinical appearance of pilar sheath acanthoma may suggest a small version of keratoacanthoma, but that is not borne out by the microscopic features. In particular, the epithelium lacks the degree of proliferation, glassy cytoplasm, or the intraepithelial neutrophilic microabscesses characteristic of keratoacanthoma. As indicated previously, the differences between dilated pore and pilar sheath acanthoma are largely ones of degree, with dilated pore displaying a closer resemblance to a mature hair follicle.

Trichoadenoma

Clinical Features: Trichoadenoma was once considered by some to represent a variant of trichoepithelioma—presumably one consisting of mostly horn cysts—but appears to be unique enough to merit a separate designation. It sometimes bears the eponymic name trichoadenoma of Nikolowski.22 It is typically a solitary nodule that develops on the head and neck or occasionally the trunk. Simple excision is effective treatment.

Microscopic Findings: This lesion consists of numerous keratin-filled cysts composed of polyhedral cells with eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm; some of the lining cells display keratohyaline granules. Solid buds of epithelium are also noted, although some of these exhibit cystic spaces on serial sectioning. Basaloid elements are not evident. The surrounding stroma is fibroblastic; attachments to the epidermis are not observed, and hair shafts are not identified in the cystic spaces (Fig. 19-4). Staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), chromogranin A, and CD15 is negative.

Differential Diagnosis: The chief differential considerations include two lesions with similarly appearing horn cysts: trichoepithelioma and microcystic adnexal carcinoma.23,24 However, both of these lesions also feature narrow cords of epithelial cells, with evidence of lumen formation in those of microcystic adnexal carcinoma. In a sufficiently large biopsy/excisional specimen, trichoepitheliomas (particularly the desmoplastic variants) have a sharply demarcated base, whereas microcystic adnexal carcinomas show deep infiltration within the subcutis.24 Calcification within the horn cysts is a typical feature of trichoepithelioma. In contrast to trichoadenomas, desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas are usually positive for EMA and chromogranin, whereas microcystic adnexal carcinomas are positive for CEA and CD15. The findings can also be almost identical in chloracne, a distinctly different clinical picture but one in which horn cysts are prominent and sebaceous lobules inconspicuous.

Trichilemmoma

Clinical Features: Trichilemmoma is primarily a tumor of the head and neck region that is most commonly seen in adults. In most instances, this tumor arises sporadically, with no particular disease association. However, multiple lesions are observed in Cowden syndrome, an autosomal dominant disorder that combines various skin tumors with hamartomatous intestinal polyps and carcinomas of the breast, thyroid gland, and other sites. This syndrome has been linked to a mutation in a tumor suppressor gene known as PTEN on chromosome 10.25 The trichilemmoma is also one of the adnexal tumors that can arise in association with a nevus sebaceus. Simple excision is sufficient for removal.

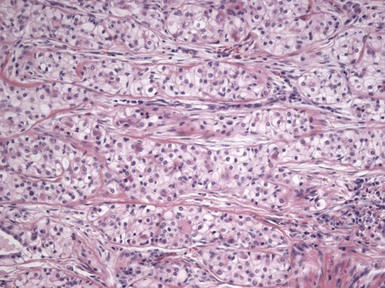

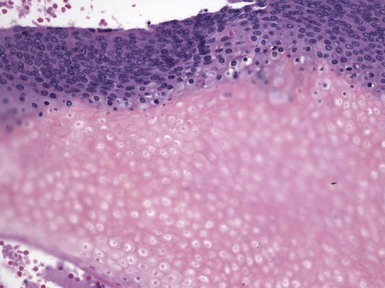

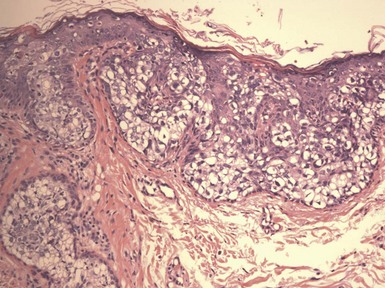

Microscopic Findings: Trichilemmomas are characterized by lobulated, follicle-centered proliferations of bland, uniform polyhedral cells with clear glycogenated cytoplasm (Fig. 19-5). The peripheral basal cells of the lobular proliferations demonstrate striking nuclear palisading, and the lobules are surrounded by a closely applied, cuticular basement membrane (Fig. 19-6). The surface frequently shows papillomatosis, parakeratosis, and scale crusting, with a configuration mimicking that of verruca. The lobules of an ordinary trichilemmoma have rounded contours with “pushing” borders, but the variant of this tumor called desmoplastic trichilemmoma shows a pseudoinfiltrative base, with islands of epithelial cells with somewhat fusiform appearance irregularly interdigitating between fibromyxoid connective tissue (Fig. 19-7). Preservation of the cuticular basement membrane is a useful diagnostic clue, and this structure can be highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), collagen IV, or laminin stains. One study demonstrated CD34 reactivity in all trichilemmoma variants.26

Differential Diagnosis: The differential diagnosis of trichilemmoma includes other tumors with clear cell variants, including basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. The greater degrees of atypia in those two lesions should ordinarily allow distinction, and the CD34 positivity of trichilemmoma may also constitute a distinguishing feature. However, a variant of basal cell carcinoma has been described with thickened basement membrane, capable of mimicking trichilemmoma and other benign tumors.27 In addition, basal cell carcinoma has been reported to arise in association with desmoplastic trichilemmomas.28 Inverted follicular keratosis has an endophytic, lobulated growth arrangement similar to that of trichilemmoma, and in fact the two are often discussed together as benign, lobulated verruciform lesions. However, the inverted follicular keratosis has a closer resemblance to the irritated seborrheic keratosis and is often considered an endophytic variant of that lesion. Accordingly, there are usually horn cysts and some degree of intercellular edema (spongiosis), while the distinctive peripheral palisading and cuticular basement membrane of trichilemmoma are not apparent. Although the distinction between the two benign lesions ordinarily would not be crucial, recognizing that a lesion represents trichilemmoma could be important because of the condition’s known association with Cowden disease. Neither trichilemmoma nor inverted follicular keratosis has been shown to contain the DNA of human papillomavirus.29,30

Tumor of the Follicular Infundibulum

Clinical Features: Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is an uncommon lesion with a predilection for middle-aged or elderly women. It typically presents as a solitary papule or nodule measuring less than 1 cm in diameter. Multiple or eruptive lesions have been reported but are less common. As is the case for trichilemmoma, these lesions have been reported in Cowden syndrome,19 although they have also been identified in the Schöpf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome, a rare autosomal dominant disorder that also includes keratoderma, apocrine hidrocystomas, hypotrichosis, and nail and tooth abnormalities.31

Microscopic Findings: There is a subepidermal epithelial growth with a platelike configuration and multiple connections with the surface epidermis. Exaggerated nuclear palisading of peripheral basal cells is evident, together with a prominent surrounding basement membrane, and the constituent keratinocytes have a glycogenated appearance, resembling that of the outer root sheath (trichilemmal sheath)19,32,33 (Fig. 19-8). Cytologic atypia and mitotic activity are not observed in the lesion. These are not hair-producing tumors, although follicles, sebaceous glands, or sweat glands may be present within the lesion. Deposits of elastic tissue have been found in the dermis immediately beneath the lesion.19

Differential Diagnosis: These lesions have a rather unique configuration. Some microscopic details—glycogenated cells, distinctly palisaded basilar cells, prominent basement membrane—are also seen in trichilemmoma, which is a closely related tumor and shares an association with Cowden syndrome. There is some resemblance to islands of superficial basal cell carcinoma, which can occasionally display cells with clear cytoplasm. However, in contrast to basal cell carcinoma, tumor of the follicular infundibulum is negative for BerEp4.

Proliferating Trichilemmal Cyst (Benign Proliferating Trichilemmal Tumor)

See Chapter 18, Epidermal Cysts and Tumors.

Benign Follicular Neoplasms with Germinative-Type Differentiation

In contrast to the previously discussed tumors, this group of neoplasms features one or more of the germinative components of the follicular unit, including matrical cells, cortical cells, and cells of the inner root sheath. They can show evidence of hair formation to varying degrees, ranging from the keratinization and “shadow cell” formation of pilomatricomas to the actual formation of hair shafts seen in trichofolliculoma.

Trichofolliculoma

Clinical Features: This lesion presents as a solitary, flesh-colored nodule developing in the head and neck region.34–36 A unique feature is the tuft of (often) white, vellus hairs emerging from the central portion of the lesion. Trichofolliculomas are removed by simple excision.

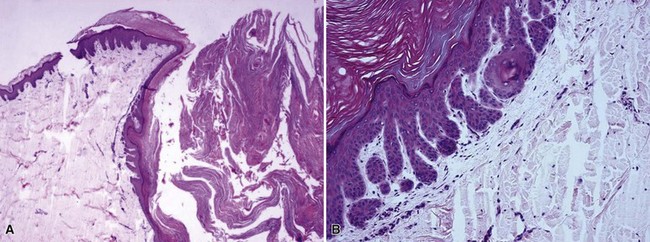

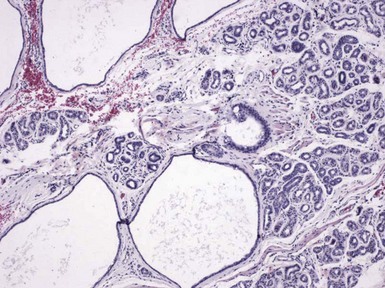

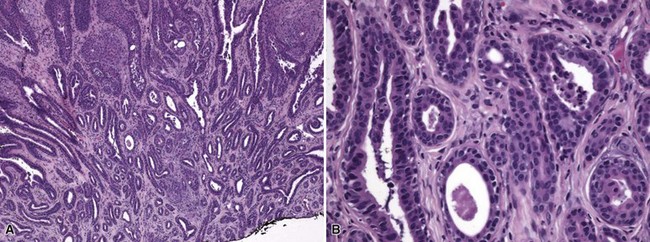

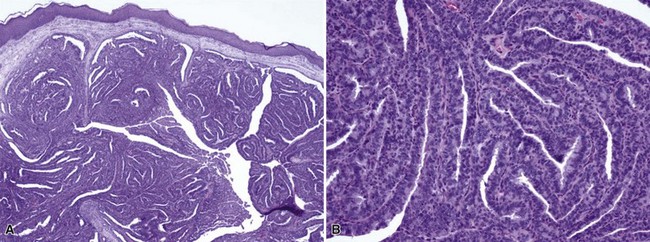

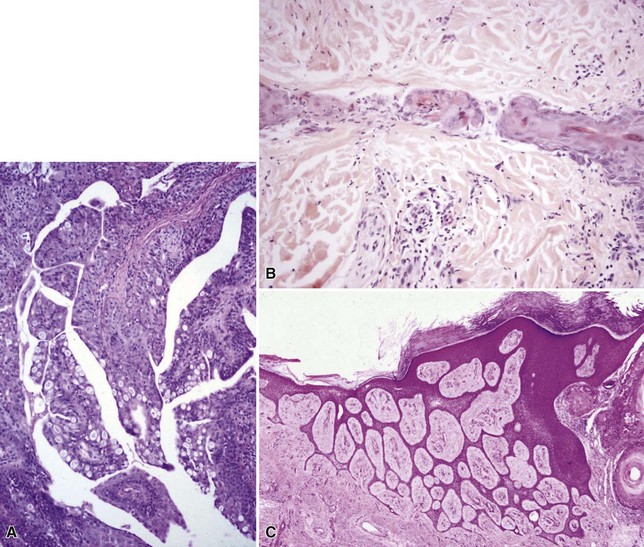

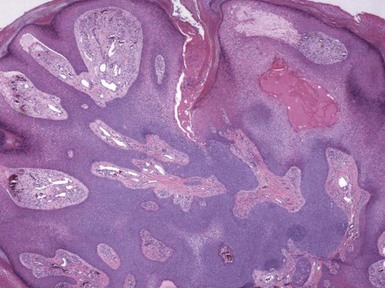

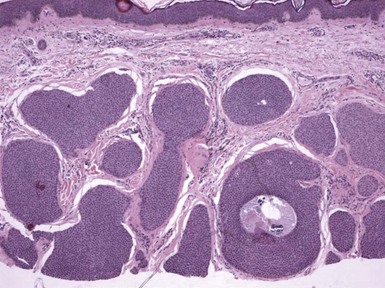

Microscopic Findings: There is a central, dilated primary follicle opening to the skin surface and lined by epithelium characteristic of the follicular infundibulum or isthmus. Secondary follicles bud from this primary follicle in a centrifugal configuration (Fig. 19-9), and depending on sectioning display either germinative epithelial differentiation or formation of mature hairs, and their cells possess isthmic or outer root sheath characteristics (Fig. 19-10). Sebaceous differentiation within the secondary follicles has been termed sebaceous trichofolliculoma.37 These epithelial features are present within a densely collagenous matrix.

Differential Diagnosis: Trichofolliculoma is occasionally confused with trichoepithelioma, but this is mainly related to the similarity of the terms. The tumor of trichoepithelioma appears more primitive and consists mainly of nests and cords of basaloid cells; horn cysts are present, but hair production is not observed. Similar considerations help distinguish trichofolliculoma from basal cell carcinoma with pilar differentiation; in addition, the stroma of basal cell carcinomas most often is of fibromyxoid type. Another lesion that bears a close resemblance to trichofolliculoma is the folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma (see “Sebaceous Tumors”), which typically has a more cystic configuration and a stroma that may include neural, vascular, and adipocytic components. It has been proposed that these two lesions represent part of a spectrum,38 or that folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma represents the late stage of a trichofolliculoma,39 but not all authors agree that these tumors have a pathogenetic relationship.40

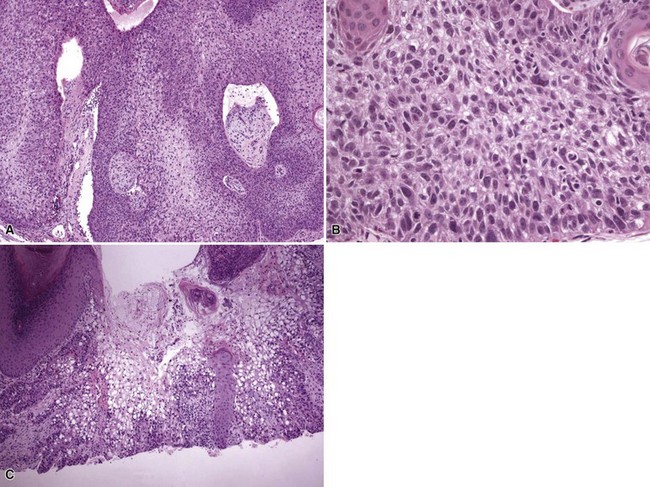

Trichoepithelioma

Clinical Features: There are two major variants of this follicular tumor: classic trichoepithelioma and desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Classic trichoepithelioma usually appears as a single, slowly growing, flesh-colored nodule on facial skin. It often appears in children41,42 but occasionally is first noted in older adults. It can reach a large size and appear on other body sites, although some experts would categorize the latter lesions among the trichoblastic tumors (see later discussion). Multiple trichoepitheliomas, arising usually in the head and neck region but occasionally elsewhere, are inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and are termed epithelioma adenoides cysticum or Brooke tumors. Multiple trichoepitheliomas sometimes coexist with multiple cylindromas (“turban tumors”), spiradenomas, salivary gland dermal analog tumors, trichilemmomas, or basal cell carcinomas.43,44 Associations of trichoepitheliomas with more generalized or systemic disorders are seen in Rombo syndrome (including milia, hypotrichosis, atrophoderma, basal cell carcinoma, and vasodilatation with cyanosis) or with systemic lupus erythematosus or myasthenia gravis.45

Molecular studies have shown that, when presenting in the context of a syndrome, trichoepithelioma is linked to genes with tumor suppressor characteristics that reside on chromosomes 9p21 and 16q12q13.46–48 In fact, multiple germline mutations in the CYLD gene (mapped to chromosome 16q12q13) have been found in families with multiple trichoepitheliomas, multiple cylindromas, or the Brooke-Spiegler syndrome (multiple trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, or spiradenomas).49 On the other hand, sporadic trichoepithelioma and basal cell carcinoma share a loss of heterozygosity and chromosomal deletions at 9q22.3, the patched gene,50 as well as overexpression of the Gli1 transcription factor.51 These findings suggest a close relationship between these two tumors and raise the possibility that sporadic trichoepithelioma might be a variant form of basal cell carcinoma.

Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma often appears as a flesh-colored plaque in the central facial region of young or middle-aged women.52 It is typical for these lesions to have an elevated border and a somewhat depressed, sclerotic center. Although patients usually present with solitary lesions,17 the author has seen desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas in the setting of multiple tumors, some of which were of the classic type. Both lesions show indolent biologic behavior and are cured by simple excision; even partial excision may be sufficient in many cases.

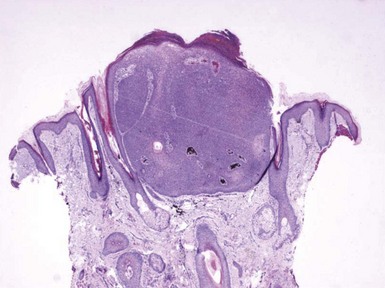

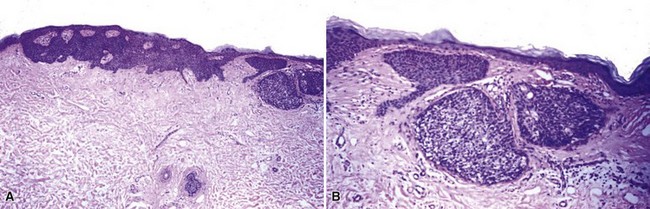

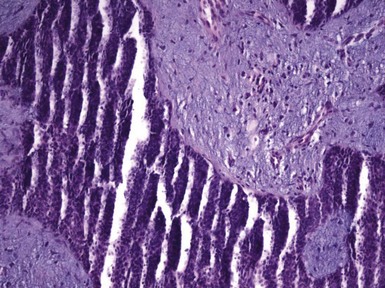

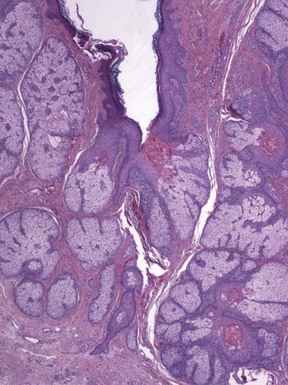

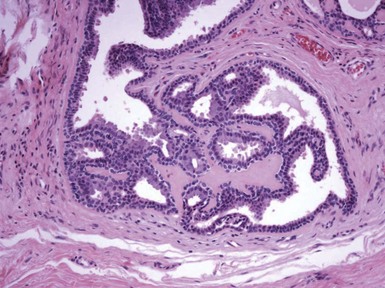

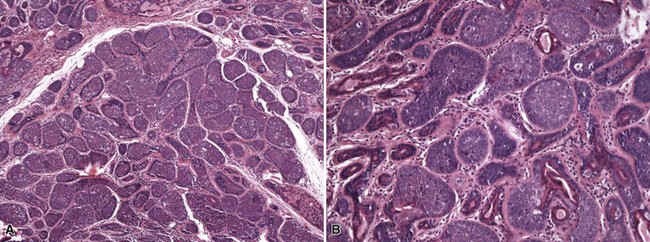

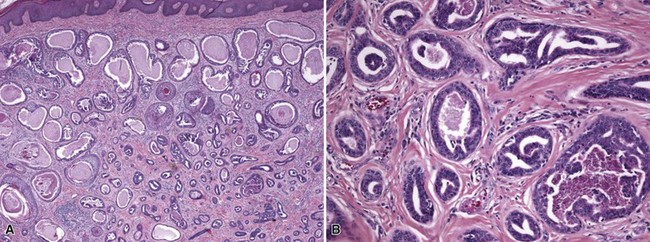

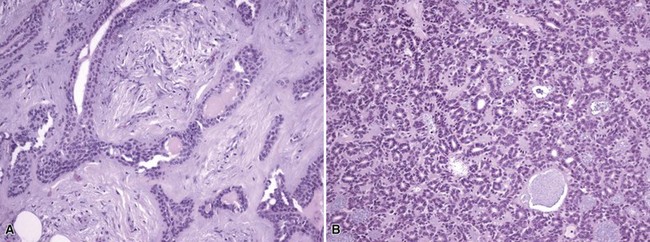

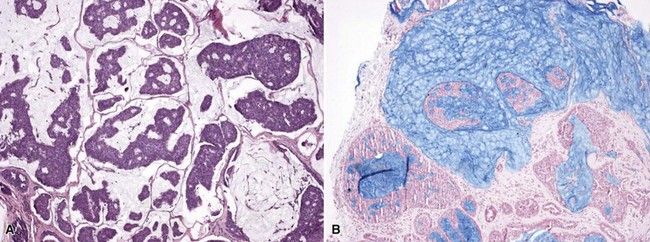

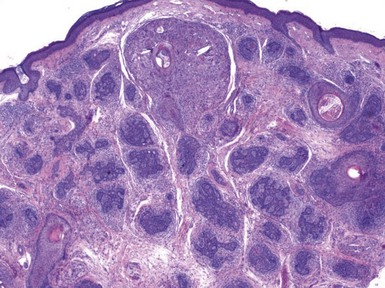

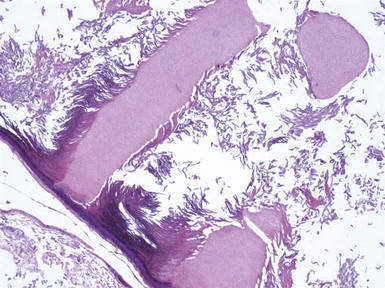

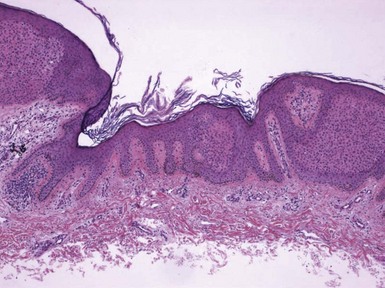

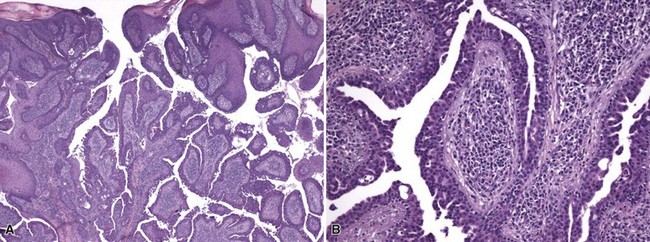

Microscopic Findings: Classic trichoepitheliomas show lobular dermal aggregates of uniform basaloid cells, separated by a mature, collagenized and sometimes hypercellular matrix. The lobules often display a fronted configuration and may interconnect by narrow cords of cells. Some contain keratinous cysts that are composed of cells with infundibular or isthmic differentiation (Fig. 19-11). Calcification within these cysts is occasionally seen. Another demonstration of the close association between epithelium and stroma in these tumors is the formation of papillary mesenchymal bodies—aggregates of fibroblast-like cells that are believed to represent attempts to form the dermal hair papillae responsible for induction of normal follicular units.53 These can be seen in close approximation to epithelial islands and sometimes appear within an epithelial invagination or in proximity to structures resembling hair bulbs (Fig. 19-12). Recognition of papillary mesenchymal bodies can be of substantial diagnostic importance (see subsequent discussion).

Figure 19-11 Trichoepithelioma. This is an example of a “classic” lesion, showing lobular aggregates of fronded basaloid cells within a cellular fibrotic matrix. Horn cysts can be identified, one of which has a surrounding granulomatous infiltrate.

Figure 19-12 Trichoepithelioma: papillary mesenchymal body. A cluster of mesenchymal cells invaginates an island of basaloid cells.

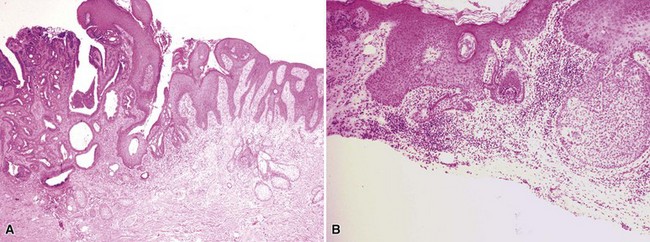

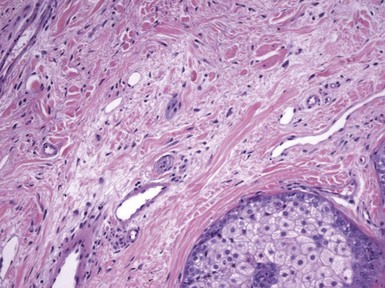

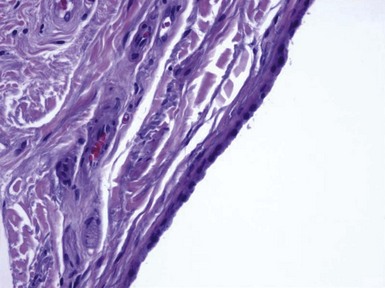

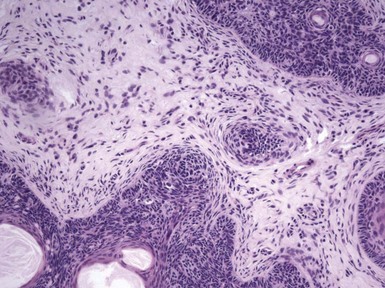

In desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, low-power microscopic examination shows a disk-shaped dermal lesion (wider than it is deep) with sharply demarcated lateral margins. Narrow cords of compact polygonal epithelial cells are identified, without a palisaded basaloid component. Keratinous microcysts are evident, and these may display calcification or, rarely, metaplastic ossification (Fig. 19-13). The epithelial elements are again found within a dense and collagenous stroma, with variable cellularity. When biopsies are sufficiently deep, it is apparent that the base of the lesion is also well demarcated, the depth often limited to the midreticular dermis (Fig. 19-14). Deep subcutaneous infiltration is not observed, and perineural invasion is not a feature. An association with intradermal nevi has been reported on several occasions; when this occurs, nevus cell aggregates are found to reside within cords of epithelial cells in an intimate admixture that would not be expected in a “collision” tumor.54–56

Figure 19-13 Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Cords of epithelial cells and microcysts are identified within a collagenous, cellular stroma.

Special stains, including immunohistochemical methods, are chiefly used to distinguish trichoepitheliomas from basal cell carcinoma and other adnexal tumors. Therefore, these are considered in “Differential Diagnosis.”

Differential Diagnosis: The chief differential diagnostic consideration when evaluating for possible trichoepithelioma is basal cell carcinoma. In contrast to trichoepithelioma, basal cell carcinoma is more apt to feature a fibromyxoid stroma, clefting artifact separating tumor islands from this adjacent stroma, and apoptotic foci in the presence of melanin deposition. In contrast, trichoepitheliomas more often feature papillary mesenchymal bodies,53 although these can be seen occasionally in basal cell carcinomas with follicular differentiation (“keratotic” basal cell carcinomas). Numerous studies have endeavored to find ways to distinguish trichoepithelioma from basal cell carcinomas using special stains and immunohistochemical methods. Thus, basal cell carcinomas are said to contain more elastic fibers than trichoepithelioma.57 CD34 positivity in peritumoral stroma is a feature of trichoepithelioma.58 Basal cell carcinomas typically stain strongly and uniformly for BerEp4 and BCL2, whereas trichoepitheliomas may show peripheral or more variable staining of tumor islands with these markers.59,60 Other markers that have been tried include the matrix metalloproteinase, stromelysin-3 (positive in the fibroblastic cells surrounding islands of morpheaform basal cell carcinoma but not in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma),61 CD10 (positive mainly in peritumoral stroma of trichoepitheliomas, in basaloid cells of basal cell carcinoma),62 and keratin 15 (peripheral localization is most typical for trichoepithelioma).57 A panel of stains consisting of keratin 20 (positive in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma but not in morpheaform basal cell carcinoma) and androgen receptor (less frequent in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma than in morpheaform basal cell carcinoma) has been recommended by Katona and colleagues.63 However, none of these stains, either in isolation or in combination, has proven to be completely reliable in distinguishing between these two lesions.60,64 This fact, combined with the often close morphologic resemblances and genetic similarities described earlier, leads to the conclusion that trichoepithelioma and basal cell carcinoma are part of a continuum. From a practical standpoint, trichoepitheliomas should be removed completely wherever possible, or at least subjected to close clinical surveillance.

Two other adnexal tumors that bear a passing resemblance to classic trichoepithelioma include cylindroma and spiradenoma, both thought to display sweat gland differentiation. Both of these lesions show much more intercellular basement membrane material. Cylindroma features mucin-filled cylinders of cells, whereas spiradenoma shows internal dispersion of mature lymphocytes and prominent lymphatic spaces. Trichoblastic tumors also bear a close resemblance to trichoepithelioma, and in fact, some authorities regard the former lesions as variants of trichoepithelioma. See “Trichoblastic Tumors” for a more detailed discussion of these tumors. In contrast to morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, the desmoplastic trichoepithelioma is better circumscribed both laterally and at its base, lacks a fibromucinous stroma or retraction artifact, and is not composed of truly basaloid elements.65 The distinction of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma from microcystic adnexal carcinoma can be quite difficult or impossible when superficial shave biopsies are submitted for evaluation. However, the latter consists of more tubular cell nests, and deeper biopsy shows that infiltrating cellular islands permeate deeply into the subcutaneous tissue and are prone to perineural infiltration.

Pilomatricoma

Clinical Features: Pilomatricoma, also termed calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, is a tumor that displays differentiation toward the follicular matrix. It has a bimodal age distribution, with the greatest peak in children and young adults and a second peak in individuals older than 50 years of age. It presents as a deep, slow-growing, cystic nodule that is firm and sometimes rock hard on palpation. It most often arises on the head and neck but is sometimes found in other locations.66–69 Surface erosion is occasionally evident. Multiple pilomatricomas may be seen in myotonic dystrophy,70 and, as mentioned elsewhere, cysts showing features of pilomatricoma are identified in patients with Gardner syndrome.71 A possible association with Turner syndrome is less clear.72

Changes suggesting an intermediate-grade lesion (atypical or proliferating pilomatricoma) can be seen (see microscopic description). There is also a pilomatrix carcinoma, which is discussed in a later section. Occasionally, the deep location of a pilomatricoma may create a resemblance to an enlarged lymph node, prompting the use of fine needle aspiration biopsy. Diagnosis can be made with this technique,73 although the cytologic atypia often seen in specimens obtained by this method may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma. Local excision is the recommended therapy for these lesions.

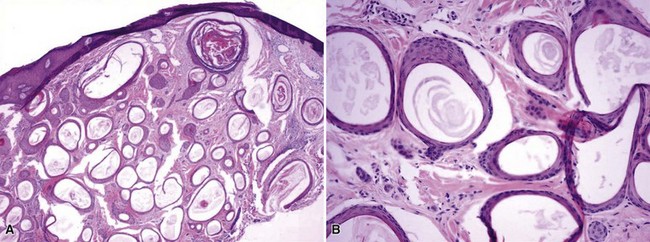

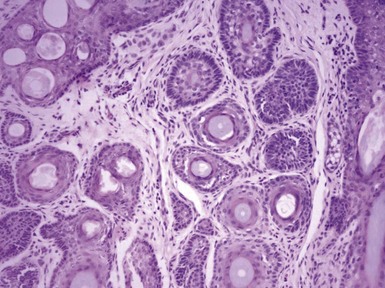

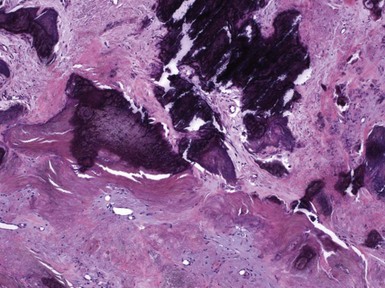

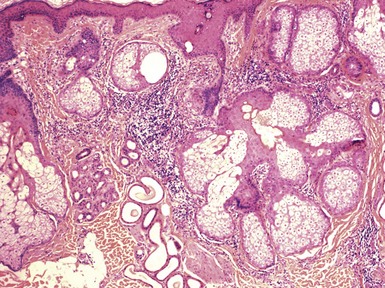

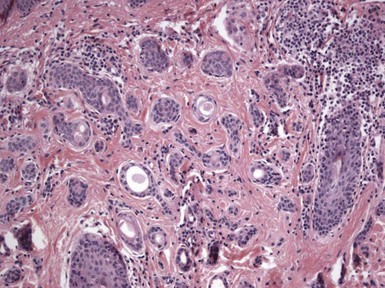

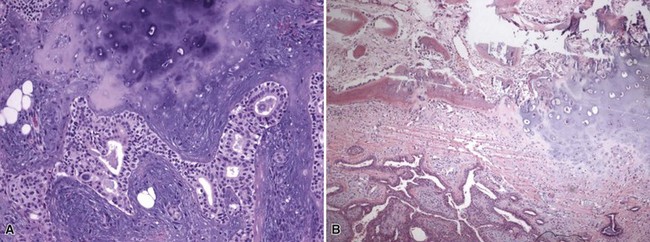

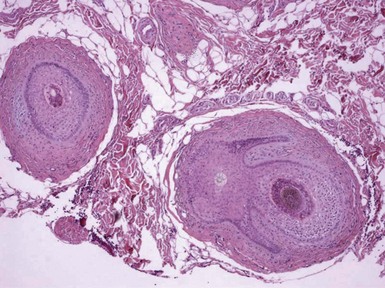

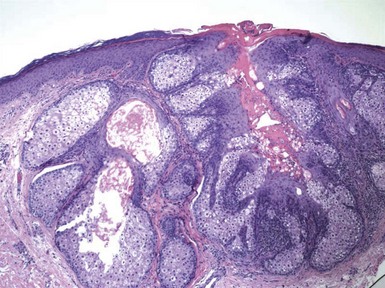

Microscopic Findings: It has been proposed that pilomatricoma begins as a cystic lesion lined by infundibular epithelium and basaloid, germinative matrical cells.74 This idea is supported by the finding of cysts with pilomatrical components in patients with Gardner syndrome71,75 (Fig. 19-15). However, in actual practice, a cystic configuration is only occasionally identified in biopsies of pilomatricoma—and then only in a portion of the lesion. Instead, there are two major components of these lesions organized with respect to one another, although sometimes appearing to be distributed through the lesion in a random arrangement: (1) aggregates of basaloid cells with monotonous round nuclei, dark chromatin, small nucleoli, and scattered mitotic figures, and (2) eosinophilic, keratinous material (Fig. 19-16). The basaloid cells tend to be aggregated at the periphery and show transition into an intermediate zone in which nuclei take on a washed-out appearance and are found within an amorphous, eosinophilic matrix; these are the so-called shadow cells (Fig. 19-17). Shadow cells exclusively occupy the central portion of these formations. Dystrophic calcification may be found in these keratinized zones; hence the other name for this tumor (calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) (Fig. 19-18). Over time, the basaloid cells are replaced by keratinized shadow cells, associated with calcification and occasionally metaplastic ossification. The exposed keratinous material often elicits a vigorous, partly granulomatous inflammatory reaction.74 Foci of ossification occasionally show intratumoral extramedullary hematopoiesis.76

Figure 19-15 Pilomatricoma changes in cyst of Gardner syndrome. Arising in the wall of an epidermal cyst are columns of shadow cells. A few basaloid cells are seen between the two columns; these are elements of pilomatricoma.

Figure 19-17 Pilomatricoma. The transition from basaloid cells to shadow cells can be seen in this image.

Microscopic variants of pilomatricoma include pilomatricoma with anetoderma, probably the result of elastophagocytosis by the granulomatous reaction that is frequently present77; perforating pilomatricoma, with extrusion of keratinous material through a disrupted epithelial surface78,79; and pigmented pilomatricoma.80 In another form of pilomatricoma, budding groups of tumor cells infiltrate into the surrounding tissue and elicit a desmoplastic reaction. These have been designated atypical, invasive, proliferating, or aggressive pilomatricomas, and unlike ordinary pilomatricomas, they are prone to local recurrence.81,82

Differential Diagnosis: Samples that show predominantly basaloid cells can be confused with conventional basal cell carcinoma, but the latter tumor usually shows peripheral palisading and clefting artifact that separates tumor islands from adjacent fibromucinous matrix, features not seen in pilomatricoma. Basal cell carcinomas with pilar differentiation may rarely show matrical differentiation, but other more typical features of basal cell carcinoma usually allow distinction. Pilomatricomas subjected to fine needle aspiration cytology can be confused with metastatic carcinoma; recognition of shadow cells in aspirates can then be a key to making the correct diagnosis.83 Shadow cells in general have been considered to be a clue to follicular differentiation; in addition to pilomatricoma and pilar basal cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation, they have been seen in hair shafts in some alopecias,84 the horn cysts of conventional and desmoplastic trichoepithelioma as well as microcystic adnexal carcinoma,84,85 mixed tumor of skin,84 proliferating trichilemmal tumor,86 and even intracranial dermoid cyst.87 Other features of these lesions should permit ready differentiation from pilomatricoma.

Trichoblastic Tumors

Clinical Features: In 1976, Headington proposed a grouping of hair follicle tumors that show features comparable to the odontogenic tumors; he called these trichoblastic tumors.88,89 They are classified microscopically according to degrees of differentiation and proportions of epithelial and mesenchymal components. Lesions present as nodules that range from 1 to 2 cm in diameter, may be deep-seated, and can be seen in virtually any location with the exception of the distal extremities. These generally benign lesions are managed by simple excision. One exception, a trichogerminoma reported by Sau and associates, metastasized.90

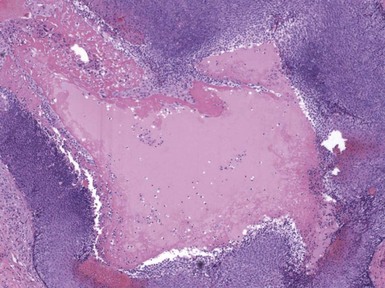

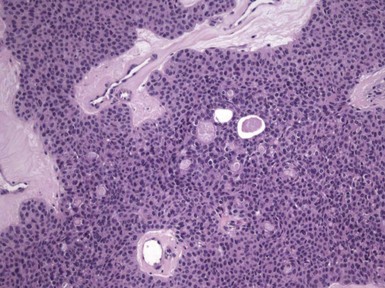

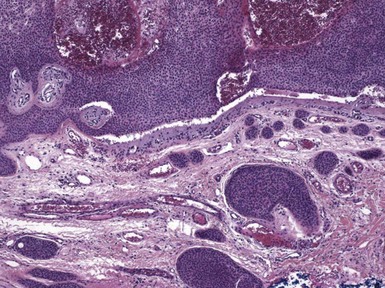

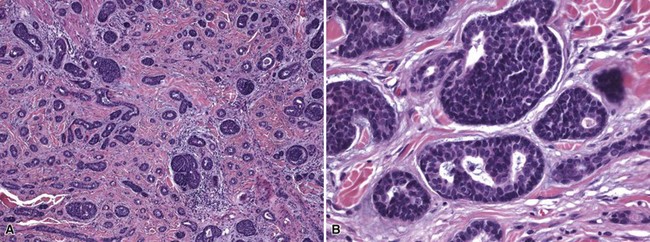

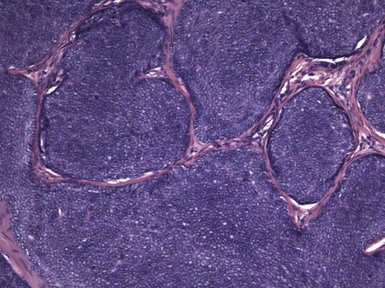

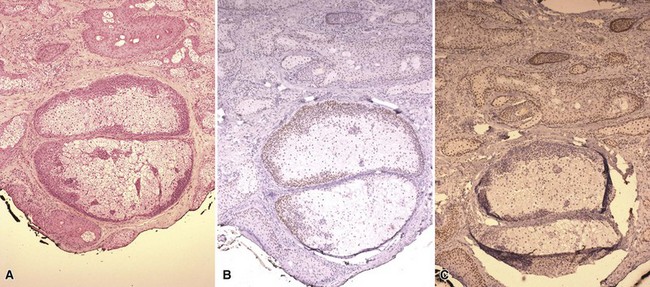

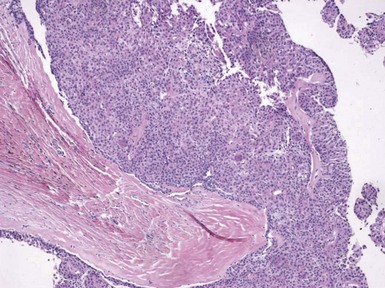

Microscopic Findings: The most primitive tumor in this group is known as trichoblastoma or trichogerminoma. It is a well-demarcated lesion, centered in the deep dermis, composed of relatively uniform basaloid cells with dispersed chromatin, small nucleoli, and mitotic activity. Tumor islands are separated from one another by a cellular, collagenous to fibromucinous stroma. The characteristic feature is the formation of cellular “balls” within the larger tumor aggregates: these are small nodular groupings that have a concentric arrangement suggestive of hair bulbs (Fig. 19-19). Other features include nuclear palisading, PAS-positive membranes surrounding the larger tumor islands, microcysts, and apoptotic bodies. The trichoblastic fibroma is often regarded as the most common of the trichoblastic tumors. It consists of interconnecting cords of basaloid cells, two to three cells in thickness, separated by a cellular stroma91 (Fig. 19-20). A hyaline membrane surrounds the cords of cells. A rippled pattern trichoblastoma has been described.92 Small cystlike structures can be seen, and there are often basilar buds invaginated by stromal cells, recapitulating the hair bulb and primitive dermal hair papilla. Pigmented93 and multinodular94 subtypes have been reported. Lesions with a cellular, mucinous stroma have been termed trichoblastic myxoma, a tumor presumably analogous to the odontogenic myxoma88,92 (Fig. 19-21). In the uncommon trichogenic trichoblastoma, there is advanced follicular differentiation. There tends to be a centrifugal organization of the tumor, in which hair bulbs are arranged at the periphery of tumor islands and hairs are arranged centrally, found within small keratinizing cysts89 (Fig. 19-22). In the case of Requena and coworkers, advanced differentiation was demonstrated by dermal papilla-like structures and inner root sheath differentiation, although hair shaft formation could not be demonstrated.95

Figure 19-19 Trichoblastoma (trichogerminoma). Basaloid tumor islands show cellular “balls” with a vague suggestion of hair bulbs.

Figure 19-20 Trichoblastic fibroma. There are interconnecting cords of basaloid cells within a cellular stroma.

Figure 19-22 Trichogenic trichoblastoma. Advanced follicular differentiation is present. This view shows follicular units oriented toward a central point.

A feature often seen in trichoblastic tumors, particularly the trichoblastic fibroma, is adamantinoid change, resembling the odontogenic tumor ameloblastoma. This consists of tumor islands with palisades of basaloid cells surrounding loosely arranged cells in an edematous background, mimicking the stellate reticulum of the enamel organ. A lesion called cutaneous lymphadenoma probably represents an adamantinoid trichoblastoma, with the additional finding of prominent lymphocytic infiltration of the tumor islands.96,97 This relationship is further supported by a recent study by McNiff and colleagues, in which staining for CK20 (Merkel cells), BCL2, CD34, S-100, and CD1a produced similar results for lymphadenomas and trichoblastomas.98

Differential Diagnosis: The cellular “balls” in trichoblastoma (trichogerminoma) are probably sufficiently distinctive to distinguish this tumor from basal cell carcinoma or trichoepithelioma. Differentiation of trichoblastic fibroma from basaloid follicular hamartoma can be challenging because the latter also shows single-file cords of cells and a close association of epithelium and stroma. However, embryonic hair follicle–like structures are not as commonly seen in basaloid follicular hamartoma as they are in trichoblastoma. Trichogenic trichoblastomas that produce hair could have some features in common with trichofolliculomas, but the former are larger tumors that are less differentiated and do not show the organization of small but mature secondary follicles entering on a central, cystically dilated follicle. Some have suggested that trichoblastic tumors are simply variants of trichoepithelioma. However, the former often appear quite different clinically (larger lesions, often in locations other than the head and neck) and have much more variable histopathology with, in some cases, more advanced follicular differentiation. In several immunohistochemical studies of small nodular and rippled pattern trichoblastomas, Yamamoto and associates found similar keratin profiles for the two trichoblastic tumors, including expression of CK 7, which is not found in trichoepithelioma.92,99 CD10 may have some use in separating basal cell carcinoma from trichoblastoma; trichoblastomas show only peritumoral stromal staining for CD10, whereas basal cell carcinomas typically show intraepithelial staining. A combination of both epithelial and peritumoral stromal staining is seen in basal cell carcinomas with follicular differentiation.100

Neoplasms with Differentiation toward Follicular Mesenchyme

Several lesions have been described that have as a distinctive feature perifollicular stromal differentiation. Lesions with features of trichodiscoma, fibrofolliculoma, and perifollicular fibroma have been associated with the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. It now appears that the findings these terms describe may actually represent variations on the same theme and that apparent differences among them are, in fact, effects of tissue sectioning.101 For that reason, these three findings will be discussed together.

Trichodiscoma, Fibrofolliculoma, and Perifollicular Fibroma

Clinical Features: The trichodiscoma has been proposed to represent differentiation toward the hair disc or haarscheibe.102 The hair disc is a receptor complex, including nerve ends and a fibrovascular stroma, associated with overlying epidermal Merkel cells.103,104 Trichodiscomas often present as a group of small, painless papules or small nodules in the head and neck region. They may be associated with other follicular neoplasms, particularly fibrofolliculomas. Simple excision is reported to be curative. The clinical presentation of fibrofolliculoma is similar. These lesions can be multiple, “associated” with trichodiscomas as part of the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, but they can also be solitary and nonhereditary. Lesions described as perifollicular fibroma are sometimes grouped with fibrous papule. As such, they can also occur as solitary or multiple lesions.105 It has been suggested that “perifollicular fibroma” is actually a microscopic feature rather than a clinicopathologic entity and that it can be seen in a variety of guises—as a component of the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, as a fibrous papule, in an angiofibroma, or as a kind of connective tissue nevus.

Microscopic Findings: In trichodiscoma, there is a superficial, ill-defined “disc” composed of hypocellular fibrovascular tissue that contains nerve twigs, the latter requiring special staining techniques for identification. Mucin and elastin are present in the stroma. Follicular units are seen at the periphery of these connective tissue changes, and it sometimes appears that follicles are “pushed aside” by the stroma102 (Fig. 19-23). Fibrofolliculoma shows a distorted, dilated, centrally located follicle with branching cords of epithelium that penetrate a surrounding fibrous mantle106 (Fig. 19-24). This feature has been termed an epithelial net,107 although it may imply a more complex network of epithelium than is usually observed. In perifollicular fibroma, there is lamellar fibrosis concentrated around hair follicles (Fig. 19-25). Similar changes can be seen around dermal vessels,108 an image closely resembling fibrous papule105 and angiofibroma.109 In fact, multiple lesions with features of angiofibroma can occur in the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome as well as in tuberous sclerosis and multiple endocrine neoplasia type I.109

Figure 19-23 Trichodiscoma. A “disc” composed of fibrovascular tissue appears to “push aside” a follicular unit.

Figure 19-24 Fibrofolliculoma. There is a centrally located, distorted follicular unit with branching cords of epithelium that penetrate the surrounding connective tissue.

Figure 19-25 Perifollicular fibroma. Lamellar fibrosis surrounds two cross-sectional profiles of hair follicles. One of these also shows small branching epithelial cords.

The Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder that links the cutaneous lesions described above with other abnormalities, including renal tumors (oncocytoma, papillary renal cell carcinoma, chromophobe renal carcinoma),110 pulmonary cysts with spontaneous pneumothorax,111,112 multiple lipomas, angiolipomas, parathyroid adenomas,113 and flecked chorioretinopathy.114 The association of multiple skin lesions with features of fibrofolliculoma, familial polyposis, and colorectal carcinoma had been designated the Hornstein-Knickenberg syndrome, but these features are now considered part of the spectrum of the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome.115 Much genetic research has linked the Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome to abnormalities in chromosome 17p12-q11.2,112,116 in an area known as the BHD locus, or FLCN. This region codes for a protein called folliculin, which may have a tumor suppressor function. Multiple different mutations have been identified in this coding region.117

The skin lesions most closely associated with this syndrome have been traditionally designated trichodiscoma, fibrofolliculomas, and acrochordons. However, the acrochordons of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome actually have microscopic features consistent with the trichodiscoma-fibrofolliculoma spectrum,118 and careful studies suggest that all of these lesions represent fibrofolliculomas.101,119

Differential Diagnosis: It is apparent that careful orientation and multiple levels are needed to correctly classify these lesions, because many or most of them may show branching cords of follicular epithelium or laminated perifollicular fibrosis. Fibromyxoid changes resembling those of trichodiscoma are seen in superficial angiomyxoma120 and were also reported in fibromyxoid tumors of the adventitial dermis in tissues surrounding a meningomyelocele scar.121 These lesions appear quite different clinically from the usual trichodiscoma of facial skin, but an argument could be made that they are histogenetically related lesions. The microscopic features of fibrofolliculoma are rather unique, whereas, as noted above, changes of perifollicular fibroma may be found in forms of angiofibroma or connective tissue nevi.

Malignant Pilar Neoplasms

There are several well-delineated and specific malignant pilar neoplasms, which will be described below. In addition, carcinomas with pilar differentiation that are otherwise difficult to classify are encountered not infrequently in consultation material. Many of these show several lines of differentiation, including sweat gland and sebaceous as well as pilar. The author’s approach is to designate such lesions as adnexal carcinomas with divergent differentiation rather than to devise unnecessarily complex diagnostic terminology.122,123

Trichilemmal Carcinoma

Clinical Features: Trichilemmal carcinoma was first described by Headington in 1976.88 Since then, several published series support its designation as a distinct entity.124,125 This lesion commonly occurs in older adults, and frequent locations include the face, scalp, and ears. It presents as a single, hyperkeratotic, smooth-surfaced or ulcerated nodule or plaque, although multiple concurrent lesions have also been reported.126 The initial clinical diagnosis is often actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma. A linkage with Cowden syndrome has not been reported.127

Microscopic Findings: Trichilemmal carcinoma is a lobulated, follicular-based lesion that appears to replace the sheath of one or several follicular units. Tumor cells replace both the involved follicles and the perifollicular epidermis, separated by uninvolved adjacent epithelium. There is irregular infiltration of the dermis, associated with surrounding fibroplasia and chronic inflammation. Peripheral palisading may be demonstrated in tumor lobules. Some tumor cells possess clear cytoplasm due to the presence of glycogen (PAS-positive, diastase-sensitive cells) (Fig. 19-26). Foci of trichilemmal keratinization can be seen, and tumors may be accompanied by pagetoid intraepidermal proliferation and intravascular or perineural invasion.125

Differential Diagnosis: The differential diagnosis chiefly includes those tumors characterized by clear cell change, including clear cell variants of squamous cell, basal cell, sebaceous, and eccrine carcinomas. Also included are metastatic clear cell adenocarcinoma and melanomas with clear cell change. Knowledge of the clinical features and close attention to the microscopic findings, especially to the relationship of tumor with follicular units, should permit an accurate diagnosis of trichilemmal carcinoma. PAS staining is useful in establishing the presence of glycogen in clear cells, and immunostaining for selected keratins (such as the pilar-related keratins AE13 and AE14, or keratins 1, 10, 14 and 17) can provide further diagnostic support.125,128

Malignant Proliferating Trichilemmal Tumor

Clinical Features: The clinical setting of malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor is quite similar to that of benign proliferating trichilemmal tumor (see Chapter 18). In fact, some of these tumors arise through transformation of proliferating trichilemmal tumors, in which case signs of malignancy include rapid enlargement or ulceration of existing lesions.129,130

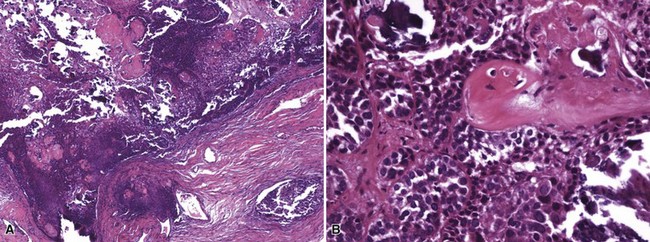

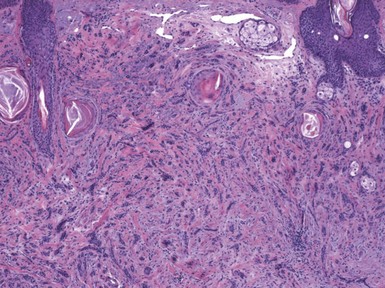

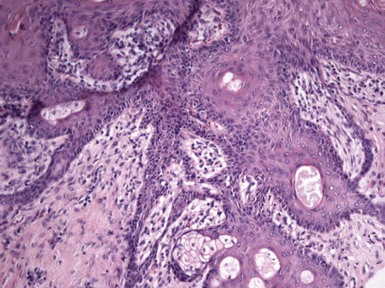

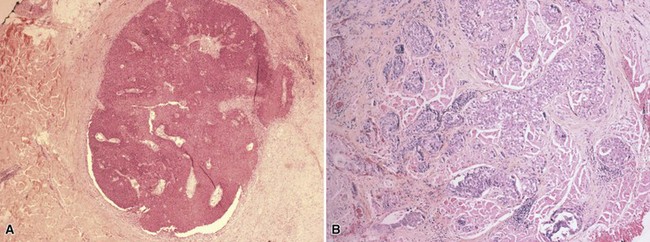

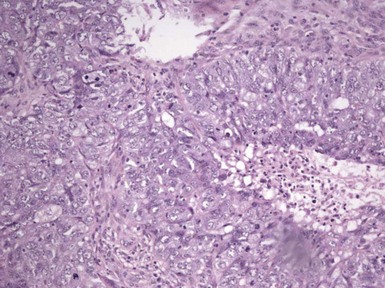

Microscopic Findings: There are two forms of malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor. The first, a low-grade variant, closely resembles the benign lesion but shows irregularly shaped cords or “buds” of neoplastic cells that invade adjacent connective tissue. The second, a high-grade lesion, lacks the lobulated configuration of the benign variant and shows geographic necrosis, marked nuclear pleomorphism, atypical mitotic figures, and sometimes spindle cell features129,131 (Fig. 19-27). Low-grade tumors tend to recur locally, but high-grade tumors are capable of distant metastasis.129

Differential Diagnosis: The chief consideration in the differential diagnosis is primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, but in contrast to the usual examples of the former lesion, malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors lack connections with the epidermis and show foci of trichilemmal keratinization. Anaplastic ductal eccrine adenocarcinoma shows some evidence of gland formation. Metastatic carcinoma with squamous characteristics does not show areas of trichilemmal keratinization, and the clinical presentation is generally quite different, because there are often multifocal and rapidly evolving lesions.

Pilomatrix Carcinoma

Clinical Features: The pilomatrix carcinoma is a rare tumor that most commonly arises in older adults132 but has been reported during the first two decades of life.81 Although pilomatricomas are more common in females, pilomatrix carcinomas arise more commonly in males.133 They are often reported to develop from preexisting pilomatricomas.81,134 Most commonly noted in the head and neck region,135 they have been reported on the trunk and extremities.134 Clinically they may resemble calcified cysts133 and can be quite large and ulcerated.136 Treatment is surgical excision,81,137 and there is a report of a case managed with Mohs surgery.138 Metastases to lymph nodes or viscera have been reported in 10% of cases.134,139

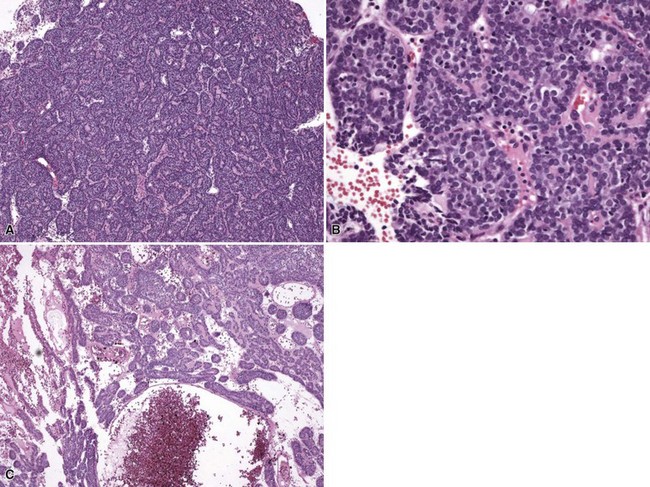

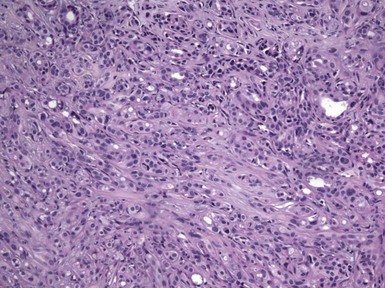

Microscopic Findings: As noted previously, and analogous to the low-grade malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors, there is an intermediate pilomatrical lesion, termed proliferating pilomatricoma, that is mainly characterized by irregular cellular growth into adjacent tissue. In contrast to true pilomatrix carcinoma, these lesions do not appear to have metastatic potential, although they can recur locally. Pilomatrix carcinoma shows zones of geographic necrosis, invasive growth, and marked cytologic atypia, consisting of cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, vesicular chromatin, and prominent nucleoli.132,136,140,141 The finding of shadow cells is the distinctive feature that marks the tumor as matrical in nature (Fig. 19-28). Immunohistochemistry has generally not been helpful in distinguishing between benign and malignant pilomatrical tumors, and therefore morphologic assessment is the principal means of establishing the diagnosis of pilomatrix carcinoma.140

Differential Diagnosis: β-Catenin, a protein involved in signal transduction, is recognized as an oncogene in colon cancer and melanoma. Several recent studies have investigated the expression of β-catenin in the basaloid cells of pilomatricoma, because its expression has been found to correlate with mutations in its encoding gene CTNNB1. Both pilomatricomas and pilomatrix carcinomas show nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin, indicating two things: (1) its expression does not explain the differences in biologic behavior of these two tumors, and (2) staining for β-catenin cannot be exploited in differentiating between them.142,143 However, the findings lend support to the idea that pilomatrix carcinomas from time to time may indeed arise from preexisting pilomatricomas.143 Small samples of pilomatrix carcinomas may create confusion with lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma144 or undifferentiated metastatic carcinoma. At present, the best means for ruling out these two neoplasms are through clinical history and the demonstration of matrical differentiation by identifying shadow cells in pilomatrix carcinoma.

Sebaceous Tumors

Benign sebaceous tumors are relatively common, and they therefore frequently come into play when contemplating the diagnosis of a nonmelanocytic cutaneous lesion. On the other hand, it is perhaps a fortunate circumstance that the number and variety of sebaceous tumors is limited. This section will consider the classification and diagnostic approach to this group of lesions. Several other general considerations regarding sebaceous tumors should be mentioned here. First, it should be recalled that sebaceous glands constitute a component of the primary epithelial germ, and therefore it should not be surprising that there are composite adnexal tumors, difficult to classify, that may have follicular and/or apocrine as well as sebaceous elements. Second, a diagnostic dilemma is often encountered when confronting tumors composed of clear cells, especially in the case of carcinomas, because well-defined sebaceous cells with compact nuclei and multivacuolated cytoplasm may not be easily recognized in some sebaceous carcinomas. Third, the existence of sebaceous adenomas, sebaceomas, or sebaceous carcinomas may raise the possibility of Muir-Torre syndrome, prompting the use of immunohistochemistry for assessment of the products of mismatch repair genes.

Pseudoneoplastic Sebaceous Proliferations

Clinical Features: Hyperplasia is the most common sebaceous proliferation. It is most commonly encountered in middle-aged to elderly individuals. Sebaceous hyperplasia most often presents as umbilicated yellow-orange, telangiectatic papules of the face and eyelids, although it may also be found in the areola of the breasts, lips, or genitalia. Coalescence of lesions to form plaques is not uncommon.145 The umbilication and telangiectasias associated with this lesion can create the appearance of basal cell carcinoma, which is frequently considered in the clinical differential diagnosis. A causal relationship has been suggested between sebaceous hyperplasia and some immunosuppressive medications.146–148 Familial sebaceous hyperplasia is an uncommonly encountered, autosomal dominant condition that begins early in life.149,150

Microscopic Findings: Several sebaceous lobules are grouped around a common, dilated duct that opens on the epidermal surface. A vellus hair can sometimes be found in the vicinity. The lobules are composed of mature sebocytes and lined by a thin layer, or several layers, of basaloid cells151 (Fig. 19-29). Plaquelike lesions show several such structures immediately adjacent to one another.

Differential Diagnosis: The major differential diagnostic consideration is sebaceous adenoma, which structurally can appear to be quite similar, but has a more prominent component of basaloid cells. The clustering of sebaceous lobules around ducts and overall sharp lesional demarcation of sebaceous hyperplasia differ from rhinophyma or other manifestations of glandular hyperplastic rosacea, in which sebaceous lobules are not as well organized. Nevus sebaceus lesions tend to lack the sharp demarcation and grouping of lobules about a common dilated duct, while they show verruciform surface changes and/or an underlying apocrine nevus (especially in adults).

Nevus Sebaceus (Organoid Nevus)

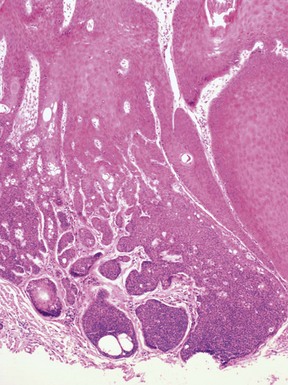

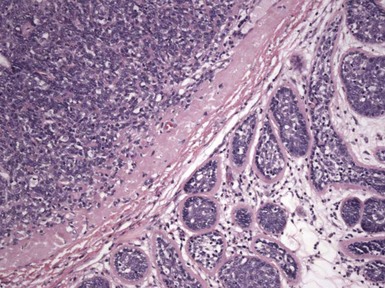

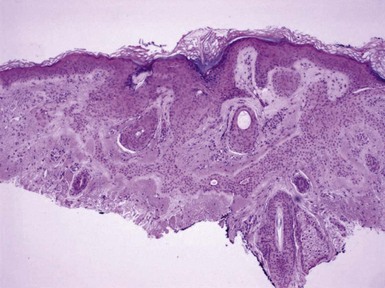

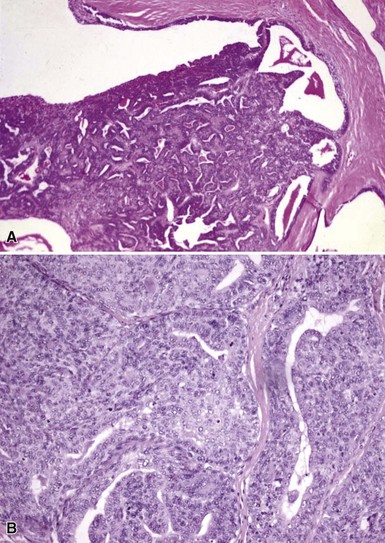

Clinical Features: Nevus sebaceus is a hamartoma that is most often found on the head and neck; most cases involve the scalp.152 It is occasionally inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. The condition is sometimes regarded as a phakomatosis (neurocutaneous syndrome), because extensive linear lesions have been associated with seizures, mental retardation, skeletal abnormalities, pigmentary changes, ocular lesions, and renal hamartomas.153 The lesions themselves most often present in early life as hairless, yellow or tan plaques of up to several centimeters in diameter. At puberty, these lesions can become distinctly verrucoid. This is a feature shared with epidermal nevus. Recently, epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated and genital mucosal human papillomavirus (HPV; especially HPV 16) DNA has been found with high frequency in lesions of nevus sebaceus; the author suggests that this finding implies maternal transmission of HPV and infection of ectodermal stem cells, resulting in altered skin development along Blaschko lines154 (Fig. 19-30). Importantly, secondary neoplasms may develop in these lesions, including basal cell carcinomas (some of which in reality may be basaloid hyperplasias155 and a variety of other epithelial and appendageal tumors, including trichilemmoma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum, and trichoblastic tumors156,157 (Fig. 19-31). Adnexal carcinomas can also arise in nevus sebaceus; apocrine, pilar, and complex carcinomas have been described, some of which are capable of regional or generalized metastases.158 It has recently been shown that tissues from lesions of nevus sebaceus show deletions in the PTCH gene on chromosome 9q22.3.159 The same locus is aberrant in basal cell carcinomas, possibly explaining the frequent development of basal cell carcinomas (and perhaps other tumors) in nevus sebaceus.

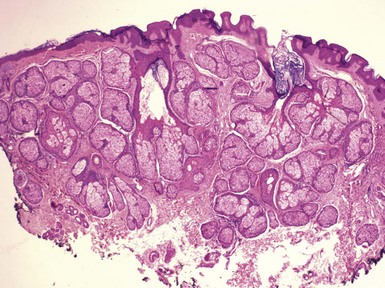

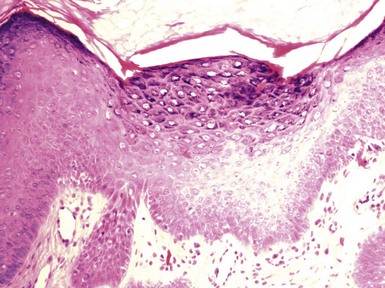

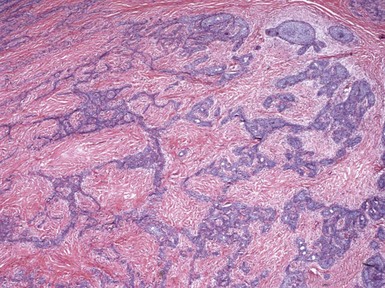

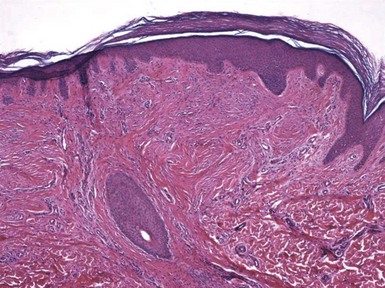

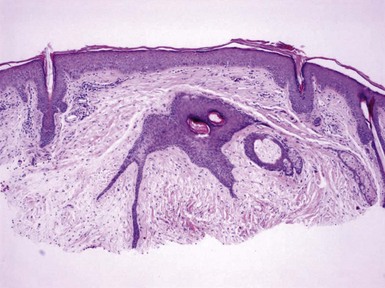

Microscopic Findings: The microscopic appearance of nevus sebaceus varies depending largely on the patient’s age.156 In infants and younger children, there appear to be immature and malformed follicular units with small sebaceous lobules (the latter being found especially after the first 3 months of life, with the diminished influence of maternal androgens), mainly occupying the superficial dermis (Fig. 19-32). After puberty, there is usually marked acanthosis with papillomatosis, having at times a distinctly verruciform configuration (Fig. 19-33). The sebaceous glands become enlarged, and there are proliferations of apocrine elements, dilatation of apocrine ducts, and, sometimes, increased numbers of eccrine sweat glands (Fig. 19-34). Sebaceous glands appear to attach directly to the overlying epidermis via a dilated duct or incompletely formed follicular unit (see Fig. 19-33) with an occasional vellus hair. There may also be disorder in the orientation of dermal collagen bundles, hypercellularity, and alteration in the density of neurovascular structures. This constellation of findings explains why many prefer the term organoid nevus for these lesions.

Figure 19-32 Nevus sebaceus in a 9-month-old child. Note immature, malformed follicular units with small sebaceous lobules in the superficial dermis.

Differential Diagnosis: Small biopsies, submitted without a clinical history, may generate a rather broad differential diagnosis. The surface changes can resemble those of epidermal nevus (without the other features of nevus sebaceus), verruca vulgaris, seborrheic keratosis, or even well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The enlarged sebaceous glands encountered following puberty may suggest sebaceous hyperplasia, the sebaceous gland enlargement often seen in adult facial skin (particularly in individuals with glandular hyperplastic rosacea), or the sebaceous lobules sometimes seen overlying dermatofibromas as a manifestation of “stromal induction.” Biopsies that are focused on a secondary neoplasm developing in a nevus sebaceus (e.g., a basal cell carcinoma), may not show sufficient surrounding changes to indicate the lesion of origin. Knowing that one of these adnexal tumors has arisen on the scalp of a relatively young individual, within a preexisting lifelong lesion, can prompt consideration of the diagnosis and lead to a determination of the most appropriate therapy.

Folliculosebaceous Cystic Hamartoma

Clinical Features: The folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma, a recently described condition,160 presents most often as a papule or nodule located in the central part of the face. Rarely, the lesion has been found elsewhere on the body surface,161 and a giant lesion has been reported.162 Rarely diagnosed clinically, it is a slow-growing lesion with a benign clinical course.

Microscopic Findings: There is an infundibulocystic structure in the dermis, to which are attached sebaceous lobules in radial array (Fig. 19-35). A characteristic stroma surrounding this epithelial structure appears to be sharply demarcated from the surrounding normal connective tissue; the stroma contains fibrous and adipose tissues, along with vessels and nerve bundles (Fig. 19-36). Immunohistochemistry demonstrates CD34 and factor XIIIa positivity within this surrounding tissue.163 In their immunohistochemical study, Toyoda and Morohashi found that nerve bundles were reactive for PGP 9.5 (a general neuronal marker protein gene product) but not for a variety of neuropeptides that are contained in normal cutaneous nerves. This finding was interpreted as supporting the concept that folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma is a tumor-like malformation with overgrowth of normal skin components.164

Differential Diagnosis: The unique constellation of features usually allows distinction of folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma from other sebaceous neoplasms. However, as noted earlier, there is some resemblance between this lesion and trichofolliculoma, particularly the sebaceous variant. Although it has been proposed that these two lesions represent part of a spectrum,38 or that folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma represents the late stage of a trichofolliculoma,39 not all authors agree.40 Misago and coworkers suggest that the up-regulation of nestin expression in lesions of folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma may explain the unique mesenchymal changes in these lesions that are not appreciated in trichofolliculomas.165 Nestin is an intermediate filament protein expressed in follicle stem cells in the bulge region of the hair follicle, and its actions may result in the production of various mesenchymal and neural tissues.

Benign Sebaceous Neoplasms

Clinical Features: Sebaceous adenoma is a slowly enlarging facial nodule with a yellowish appearance, seen most often in individuals older than 50 years of age. Occasionally, this tumor may arise in unusual sites such as the oral cavity, ear canal, or salivary gland.145,166 It measures up to several centimeters in diameter. Clinical confusion of sebaceous adenoma with basal cell carcinoma is common. This lesion and other sebaceous tumors, including sebaceomas, sebaceous carcinomas, and keratoacanthomas (some of which may contain sebaceous elements) have been associated with the Muir-Torre syndrome, together with visceral malignancies.167,168 This complex of clinical features is associated with microsatellite instability, resulting from inactivating germline mutations in various DNA mismatch repair genes, particularly MSH-2 and MLH-1.169 Microsatellite instability is found in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndromes, including the Muir-Torre syndrome. The internal neoplasms in patients with Muir-Torre syndrome are usually laryngeal, mammary, or gastrointestinal carcinomas, but other types may be seen as well, including malignant lymphoma.168,170

Microscopic Findings: In sebaceous adenoma, there is a circumscribed proliferation of enlarged sebaceous lobules, composed of mature sebocytes. The tumor often appears to compress or thin the overlying epidermis and is surrounded by a fibrous pseudocapsule in some cases. The latter feature, as well as an occasional appendageal collarette, reflects the slow growth of sebaceous adenoma. The tumor lobules may show focal ductlike differentiation and holocrine secretion, which potentially results in the formation of microcysts; lesions with this feature have been termed sebocrine adenomas.171,172 There is a prominent basaloid component, representing germinative cells, although mature sebaceous cells predominate (Fig. 19-37). Despite the presence of small nucleoli, significant nuclear atypia or mitotic activity is absent. Forms of sebaceous adenoma in patients with Muir-Torre syndrome are not as well demarcated from the adjacent dermis, and some tumors include larger numbers of basaloid, germinative epithelial cells at their periphery. Rutten and colleagues have also found that cystic change in cutaneous sebaceous tumors is more frequent in patients with Muir-Torre syndrome, and this is compatible with the author’s experience.173

Figure 19-37 Sebaceous adenoma. This is a lobulated tumor having some architectural similarities to sebaceous hyperplasia but with a more prominent basaloid component.

With regard to special staining, Hassanein and associates have suggested that staining for Thomsen-Friedenreich antigen, a glycoprotein found on epithelial cells, can separate (trifluoroacetic acid [TFA]-positive) sebaceous carcinoma from other tumors with sebaceous differentiation.174 The author does not have personal experience with the use of this antibody; however, another paper suggests that TFA staining is also positive in a variety of other skin cancers.175 The other useful procedure is immunohistochemical staining for mismatch repair proteins, especially MSH-2 and MLH-1. A lack of nuclear staining for one of these markers within the tumor is evidence of a germline mutation of the corresponding gene, and in the particular context of a sebaceous tumor supports the diagnosis of Muir-Torre syndrome. The value of this procedure has been documented in a number of studies169,176,177 (Fig. 19-38). Recently, it has been reported that mutation of MSH-6 can also be found in patients with Muir-Torre syndrome, and in fact was the mismatch repair protein most commonly lost in one study.178 This determination can be important in prompting surveillance for internal neoplasms as well as in genetic counseling.

Figure 19-38 Sebaceous adenoma with immunohistochemical staining for mismatch repair proteins. This sebaceous adenoma has been identified at the base of a keratoacanthoma-like lesion. A, Findings on H&E-stained sections. B, Positive staining of nuclei for MLH-1. C, Negative staining of nuclei for MSH-2, in the face of positive staining of nuclei in adjacent epithelium and normal sebaceous lobules.

Differential Diagnosis: The differential diagnosis of sebaceous adenoma includes other sebaceous tumors and tumor-like proliferations, basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation, and sebaceous carcinoma. Sebaceous hyperplasia can have a low-power configuration that is quite similar to that of sebaceous adenoma, but the latter has a more prominent basal cell population, and lesions associated with the Muir-Torre syndrome show a degree of disorganization not encountered in sebaceous hyperplasia. Sebaceoma (see subsequent discussion) has a greater proportion of basaloid cells and in addition may show some features in common with trichoepithelioma, dermal duct tumor, cylindroma, and trichilemmoma. Basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation can show considerable histopathologic overlap with sebaceous adenoma, but shows a higher proportion of basaloid cells (>50% of the total cell population), a fibromyxoid stroma, and clefting artifact separating tumor lobules from the adjacent stroma. Sebaceous adenomas lack the degree of cytologic atypia and infiltrative growth pattern frequently observed in sebaceous carcinomas (although there may be circumscription and even peripheral palisading in tumor islands of the basaloid variant of sebaceous carcinoma).

Superficial Epithelioma with Sebaceous Differentiation

This is a rarely encountered neoplasm with sebaceous cells, described as a slow-growing papule or verrucoid nodule on the face, trunk, or proximal extremities; multiple lesions have been reported. Microscopic descriptions in various reports consistently describe a multilobular, platelike proliferation of tumor cells in the upper dermis with multiple broad connections to the overlying epidermis. The tumor cells are basaloid and feature single or aggregated sebocytes, with more lobulated arrangements in lower portions of the tumor179–183 (Fig. 19-39). Ductlike structures with eosinophilic luminal cuticles are frequently present, and squamous eddies can be observed. The image has features particularly reminiscent of tumor of the follicular infundibulum with sebaceous elements. Thus far, there has been no reported association with the Muir-Torre syndrome.183

Sebaceoma

Sebaceoma, a term proposed by Troy and Ackerman,184 has largely supplanted the older term sebaceous epithelioma, and this newer name probably encompasses a wider variety of microscopic changes. This condition presents as a circumscribed nodular lesion that is rarely diagnosed clinically. Microscopically, these lesions present as lobulated tumors in the upper to mid-dermis, composed predominantly of basaloid cells with a minority of sebocytes, singly dispersed and in clusters. Ductlike structures and areas of trichilemmal keratinization can also be observed184,185 (Fig. 19-40). Examples of sebaceoma with rippled,186 cribriform-reticulated,187 or carcinoid-like188 configurations have been reported. Sebaceoma can usually be distinguished from the more organized sebaceous adenoma, which usually has a less prominent basaloid component. However, overlapping features of the two can occur, particularly in some of the sebaceous neoplasms of patients with the Muir-Torre syndrome. A “rippled” configuration can occur in a variety of other tumors, including trichoblastoma.188 Such tumors can usually be distinguished from sebaceoma, but there could be confusion with one variant form that has been termed rippled-pattern sebaceous trichoblastoma.188

Malignant Sebaceous Neoplasms

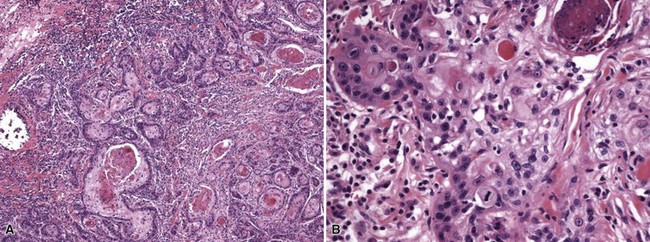

Clinical Features: Although sebaceous carcinomas have traditionally been grouped into two categories, ocular and extraocular, partly because ocular lesions were said to be associated with a worse prognosis, a review of the literature shows that ocular and extraocular tumors actually have similar risks for local recurrence, distant metastases, and tumor-related mortality.189–191 However, ocular involvement (eyelids or adnexa) is more common than extraocular involvement. Sebaceous carcinoma usually arises in middle-aged or elderly patients. Tumors of the eyelids also occur in relation to radiation therapy or secondarily following treatment of a primary malignancy of another type.192 Ocular lesions present as painless masses of lid margins or conjunctiva, and commonly resemble blepharitis, chalazion, or conjunctivitis.193 Multifocal involvement can occur. Lesions can also develop elsewhere in the head and neck region or on the trunk or extremities, where they may be typified by rapid growth, pain, or ulceration. As previously noted, sebaceous carcinoma can be a manifestation of the Muir-Torre syndrome.194 Overall, these tumors have shown a high rate of recurrence and metastasis.195

Microscopic Findings: Sebaceous carcinomas are graded based on growth patterns rather than cytologic features.196 Basically, grade I lesions are comprised of rounded, well-demarcated cellular aggregates (Fig. 19-41A), grade III lesions show infiltrative cords of tumor cells or sheetlike arrangements (see Fig. 19-41B), and grade II lesions show combinations of these growth patterns. In general, most examples consist of lobulated groups of atypical, polygonal cells within a fibrovascular stroma (Fig. 19-42A). Central areas of the cellular islands frequently show necrosis with the configuration of “comedo necrosis.” As might be expected, well-differentiated variants show reasonably numerous cells with vacuolated cytoplasm and oval, vesicular nuclei, whereas more atypical lesions show greater nuclear pleomorphism, high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, more numerous (and atypical) mitoses, and cytoplasm that is not as obviously vacuolated (see Fig. 19-42B).

Figure 19-41 Sebaceous carcinoma. A, A grade I lesion shows a well-demarcated cellular aggregate. B, A grade III lesion has infiltrative cords of tumor cells.

Figure 19-42 Sebaceous carcinoma. A, This lobulated tumor has nuclear pleomorphism. A few sebaceous cells can be identified. B, This atypical tumor shows substantial nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity.

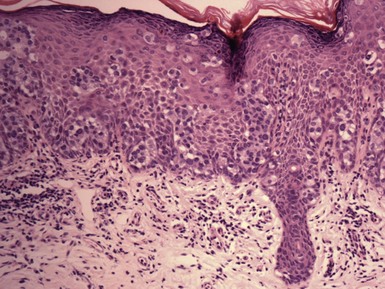

Several microscopic features or subtypes are important in diagnosing sebaceous carcinoma. An association with intraepithelial Paget disease–like change sometimes occurs,197 and examples of intraepithelial sebaceous carcinoma without underlying tumor have been reported198 (Fig. 19-43). Basaloid sebaceous carcinomas are composed of small cells with relatively high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios and peripheral palisading, but there may be significant stromal infiltration, marked nuclear atypia, and scattered clear to vacuolated cells that only vaguely suggest sebaceous differentiation. Other variants include sebaceous carcinomas with squamous metaplasia and a sarcomatoid form composed of spindled cells.

Figure 19-43 Pagetoid sebaceous carcinoma in situ. This is an intraepithelial tumor without invasion of the underlying connective tissue.

Special staining can be useful in recognizing that a particular tumor shows sebaceous differentiation. Lipid stains, including Oil Red O or Sudan IV, can be used, but they require frozen sections that may be formalin-fixed but not paraffin-embedded. Among immunohistochemical stains, neoplastic sebaceous cells are often positive for EMA,199 and they may label for androgen receptor protein,200 BRST-1,199 and cellular adhesion molecule 5.2.199 Adipophilin is a monoclonal antibody directed against adipose differentiation-related protein, which is located on the surface of intracellular lipid droplets. This stain is positive in most sebaceous tumors, including sebaceous carcinomas.201 As is also the case for sebaceous adenoma and sebaceoma, staining for DNA mismatch repair gene products can be useful in establishing a relationship to the Muir-Torre syndrome.202

Differential Diagnosis: The histopathologic differential diagnosis of sebaceous carcinoma is broad and particularly includes other malignant (and some benign) clear cell tumors of skin.203 Particular entities that should be considered are squamous cell carcinoma with clear cell features; clear cell basal cell carcinoma; trichilemmal carcinoma; balloon cell melanoma; clear cell sarcoma extending into the dermis; and metastatic clear cell carcinomas from other sites, particularly metastatic renal cell carcinoma (one of the metastatic tumors that can appear in skin before detection of the primary lesion).

Among these tumors, only balloon cell melanoma has the distinctive vacuolization expected in a sebaceous tumor; however, as previously noted, poorly differentiated sebaceous carcinoma may display only rudimentary sebaceous differentiation, and cytoplasmic vacuolization may therefore be difficult to discern. EMA can be helpful in identifying intracytoplasmic vesicles in some cases. Sebaceous carcinomas also lack several protein products that are identified in sweat gland tumors or metastatic carcinomas, including carcinoembryonic antigen, S-100 protein, gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 (GCDFP-15), cancer antigen 125 (CA-125), CA-19-9, or the renal cell carcinoma marker. A possible pitfall in diagnosis can result from the use of adipophilin, which stains cells of renal cell carcinoma as well as sebaceous carcinoma.201,204 However, the staining pattern in nonsebaceous tumors tends to be granular rather than membranous-vesicular.201 Basal cell carcinoma could potentially be confused with basaloid sebaceous carcinoma. However, basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation tends to show a higher degree of sebaceous differentiation than is the case in sebaceous carcinoma. Other basal cell carcinomas may also show clear cell change. However, the nuclei of basal cell carcinomas are not as vesicular as those in sebaceous carcinomas. In contrast to sebaceous carcinoma, the stroma of basal cell carcinoma is fibromyxoid in type. Both tumors can express BerEp4, but EMA staining is negative in basal cell carcinoma except for any areas that might show clear-cut sebaceous differentiation. Another problem that arises is the distinction between sebaceous carcinoma with squamoid features and conventional squamous cell carcinoma. Here, BerEp4 can be helpful, in that sebaceous carcinoma is positive for this marker, whereas squamous cell carcinoma is negative. Sarcomatoid sebaceous carcinoma can be distinguished from true sarcoma by its keratin positivity, but it may be difficult to recognize the tumor as specifically sebaceous if sebocytic differentiation cannot be recognized. Sebaceous differentiation can sometimes be encountered in other malignancies, including microcystic adnexal carcinoma,205 lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma,206 and the difficult-to-classify adnexal carcinoma with divergent differentiation,122 but the mere finding of sebaceous cells in these circumstances should not lead to a diagnosis of sebaceous carcinoma in the absence of other attributes of that tumor.

Sweat Gland Tumors

The following section will consider the sweat gland tumors of both eccrine and apocrine differentiation. These are organized according to degrees of differentiation. Pseudoneoplastic lesions of sweat glands are either hamartomas or reactive sweat gland changes, and these conditions include eccrine and apocrine nevi, eccrine and apocrine hidrocystomas, apocrine cystadenomas, and syringometaplasias. The well-known (to dermatologists and dermatopathologists) benign adnexal tumors include eccrine lesions (syringoma, cylindroma, spiradenoma, poroma and variants, syringofibroadenoma, papillary eccrine adenoma, acrospiroma) and apocrine lesions (syringocystadenoma papilliferum, tubular apocrine adenoma, and hidradenoma papilliferum). Mixed tumors of skin also show mixed forms of differentiation, although the majority of these appear to be apocrine. The reader should note that the classification of these tumors as either eccrine or apocrine is controversial and seemingly ever changing. Currently, apocrine derivation is in the ascendancy; thus, most hidrocystomas are believed to be apocrine, acrospiromas (with few exceptions) are now widely considered to show apocrine differentiation (although they are grouped with the eccrine tumors here), and there is believed to be an apocrine variant of poroma. The precise categorization of these tumors may be the subject of debate, but fortunately, this controversy is not critical in the recognition of these tumors or their management.