Epidermal Cysts and Tumors

Epidermal Cyst (Infundibular Cyst) and Milium

Human Papillomavirus–Associated Cyst (“Verrucous Cyst”)

Epithelial Cysts in Gardner Syndrome

Trichilemmal Cyst (Pilar Cyst, Isthmus-Catagen Cyst)

Proliferating Trichilemmal Cyst (Proliferating Trichilemmal Tumor, Pilar Tumor, Proliferating Pilar Tumor)

Benign Epidermal Tumors or Malformations

The term tumor here is used in its loosest sense: an “abnormal mass of tissue that may be benign or malignant.” It is not meant to necessarily imply malignancy or the precise size of a lesion; therefore, some entities are considered in this chapter that would ordinarily be classified as papules or nodules according to size. In fact, a few of the lesions to be discussed (e.g., actinic keratosis, porokeratosis, most examples of Bowen disease), can hardly be considered “masses” and actually have clinical characteristics of patches or plaques but still represent stages of keratinocyte neoplasia.

Tumors and cysts of epidermal origin or differentiation are among the most common lesions that arise in skin. In fact, just a few of them—seborrheic keratosis, epidermal cyst, actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma—constitute a substantial proportion of any dermatopathology practice. This situation is likely to continue, particularly considering the aging, ultraviolet-exposed population. There are many other malformations, cysts, and less common or rare tumors, both benign and malignant, of which the pathologist needs to be aware, and even among the five common entities mentioned above, there are histopathologic variants that can create considerable diagnostic confusion. In this chapter, lesions are grouped into three broad categories: (1) epithelial cysts, (2) benign epidermal tumors, and (3) premalignant and malignant epidermal tumors.

Epithelial Cysts

Epidermal Cyst (Infundibular Cyst) and Milium

Clinical Features: Epidermal cysts most often appear as smooth, dome-shaped, freely movable, somewhat fluctuant subcutaneous swellings, sometimes attached to the skin with a central pore. These lesions are common on the face, neck, and trunk but can occur in almost any anatomic location. These cysts may rupture, either spontaneously or due to trauma, with resultant inflammation and tenderness. Epidermal cysts are sometimes associated with other anomalies, such as nevus comedonicus or the Favre-Racouchot syndrome. They also represent one of the cutaneous manifestations of Gardner syndrome. It is likely that some, and perhaps most, epidermal cysts represent a developmental anomaly of the follicular infundibulum, although in other instances “traumatic implantation” is probably also a cause (the so-called “epidermal inclusion cyst”).

Milia (singular milium) are smaller versions of epidermal cysts, measuring from 1 to 4 mm in diameter. They may derive from the outer root sheath of vellus follicles. Milia are frequently multiple and tend to develop in areas of trauma (e.g., following abrasive injuries). They are particularly common in the infraorbital regions, and they also accompany several bullous disorders, notably porphyria cutanea tarda and dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

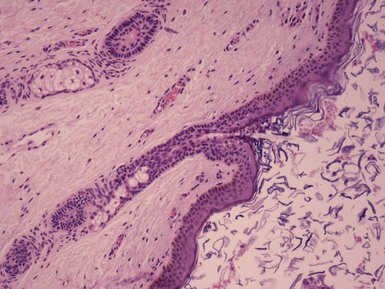

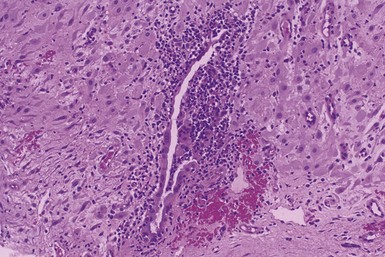

Microscopic Findings: Epidermal cysts are lined by stratified squamous epithelium resembling epidermis or follicular infundibulum. Therefore, a granular cell layer is found adjacent to the keratin-containing cyst lumen. The cyst wall may be thinned or acanthotic, with a smooth-contoured base or with irregular budding. The keratin contents are usually loosely woven, typically more so than the overlying epidermis (Fig. 18-1). Rupture is accompanied by neutrophilic and/or granulomatous inflammation, and scar is found adjacent to older inflamed lesions. The cyst epithelium may respond to such events with marked acanthosis, but in other instances the cyst wall may be obliterated or replaced by granuloma. In such instances, identifying flakes of keratin surrounded by granuloma or within multinucleated giant cells provides a clue to the diagnosis of a ruptured cyst (Fig. 18-2). Milia are smaller, thin-walled epidermal cysts that are located in the superficial dermis. There have been rare reports of Bowen disease, basal cell carcinoma (BCC), or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arising in epidermal cysts. SCCs that have been partly biopsied or treated can occasionally form cystlike configurations without apparent connections to the overlying epidermis.

Differential Diagnosis: Although epidermal cysts and milia are among the most readily diagnosable lesions in dermatopathology, occasional problems can arise. Superficial shave biopsies showing changes suggestive of epidermal cysts may miss deeper foci that would point to a different diagnosis; examples include warty dyskeratoma, branchial cleft cyst, or syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Pilar cysts (trichilemmal cysts) are usually easily recognized by their distinctly palisaded basilar layer; swollen periluminal keratinocytes with sparse or absent keratohyalin granules; and homogeneous, eosinophilic keratin. Occasional hybrid cysts are encountered that show areas resembling both epidermal and pilar cysts. The presence of both infundibular and trichilemmal keratinization provides additional supporting evidence of a follicular origin for this group of epithelial cysts. Markedly inflamed lesions may be difficult to distinguish from foreign body or infectious granulomas. In such instances, careful search for cyst wall fragments or keratin flakes can be decisive. Milialike formations can also be observed in the periphery of keratoacanthomas, and a partial biopsy of the edge of such a lesion can create confusion. A clinical history of a rapidly advancing keratotic lesion may then raise suspicion of keratoacanthoma and prompt more complete sampling of the tumor.

Human Papillomavirus–Associated Cyst (“Verrucous Cyst”)

Clinical Features: This type of epidermal cyst has microscopic features consistent with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. These cysts most commonly arise in the plantar areas of the foot,1 although similar lesions have been reported on the scalp, face, back, and extremities.2 Clinically, the lesions resemble conventional cysts or suggest dermatofibroma or BCC.2

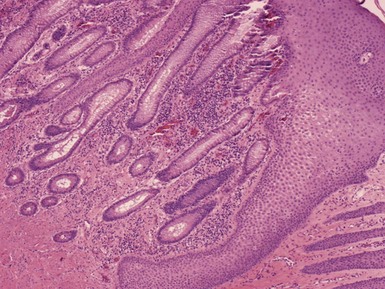

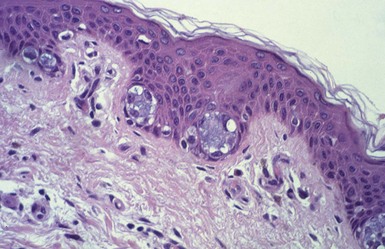

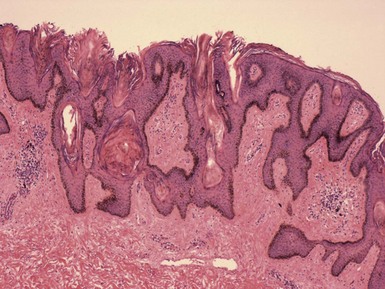

Microscopic Findings: These cysts are of the infundibular type and feature varying degrees of papillomatosis, hypergranulosis, parakeratosis, and squamous eddy formation (Fig. 18-3). Koilocytic changes with large keratohyalin granules are noted, and the presence of HPV has been documented by immunohistochemistry, hybridization studies, and by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods for detection of HPV DNA sequences.3 To date, both HPV types 57 and 60 have been detected in these cysts. There is currently uncertainty concerning whether these lesions result from traumatic implantation of verrucae or from secondary infection of preexisting epidermal cysts.

Proliferating Epidermal Cyst

Clinical Features: Although the proliferating trichilemmal cyst is a well-established entity (see later discussion), it is not as widely recognized that there is a similar proliferative, cystic lesion characterized by infundibular keratinization, with formation of a granular cell layer and laminated keratin.4 This proliferating epidermal cyst has now been well documented by Sau and colleagues.5,6 In contrast to proliferating trichilemmal cysts, these lesions show a male predominance, and most occur in locations other than the scalp. They usually have a cystlike clinical appearance.

Microscopic Findings: Several patterns have been described, including papillomatous and acanthotic epithelium with squamous eddy formation and connection to the surface through a narrow opening; inverted follicular keratosis-like changes; a multiloculated cystic pattern lined by basaloid epithelium with peripheral palisading of nuclei (Fig. 18-4); pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the cyst lining; anastomosing bands reminiscent of proliferating trichilemmal cysts; conglomerations of numerous microcysts; and verrucous projections of lining epithelium into the cyst lumen, reminiscent of HPV-induced cysts.6 Most of these lesions show at least focal portions of a cyst wall resembling that of a typical epidermal cyst. An example of a proliferating tumor that showed both trichilemmal and infundibular keratinization has also been described.7 Seven of the 33 tumors reported by Sau and colleagues showed carcinomatous histopathologic features, and lesions with these changes were particularly prone to local aggressiveness (recurrence), although their series reported no metastases.6

Pigmented Follicular Cyst

Clinical Features: Mehregan and associates first described this unusual cyst in 1982.8 It usually presents as a solitary lesion in the head and neck region of adult men.9 A case with multiple lesions has been reported, in which lesions were present on the chest and abdomen.10 Clinically, these cysts have a distinctly blue appearance, reminiscent of blue nevus.

Microscopic Findings: These are typically cysts of infundibular type. The cyst lining maintains a rete ridge pattern. Within the lumen of the cyst are multiple pigmented hair shafts (Fig. 18-5), and hair follicles or sebaceous lobules may attach to the cyst wall.8,10 Some of these lesions appear to be hybrid cysts, showing both infundibular and trichilemmal keratinization.10

Cutaneous Keratocyst

Clinical Features: Barr and coworkers discovered that two of four cutaneous cysts removed from patients with the basal cell nevus syndrome had features resembling those of the odontogenic keratocysts that characteristically occur in that syndrome.11 Subsequently, Baselga and colleagues reported a similar lesion.12

Microscopic Findings: These cysts have a festooned configuration, are lined by two to five squamous cell layers, and keratinize without the formation of a granular cell layer (Fig. 18-6). One of the cysts of Barr and coworkers also showed a small follicular bud and contained lanugo hairs, features reminiscent of steatocystoma, although sebaceous glands were absent. The authors have observed an additional example of this cyst that arose on the foot of a child with basal cell nevus syndrome. However, there have been several recent reports of cutaneous keratocysts not associated with the basal cell nevus syndrome.13,14

Epithelial Cysts in Gardner Syndrome

Clinical Features: Gardner syndrome is a dominantly inherited disorder consisting of premalignant colonic polyps, fibromas and desmoid tumors, osteomatosis, and cutaneous cysts. The cutaneous cysts mainly have the microscopic characteristics of epidermal cysts, but pilomatrixoma-like changes have been described in a number of them.15,16

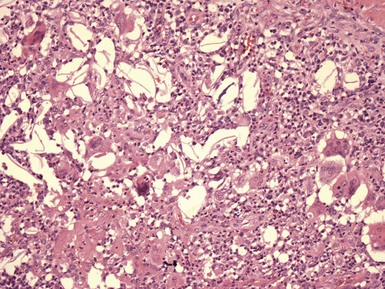

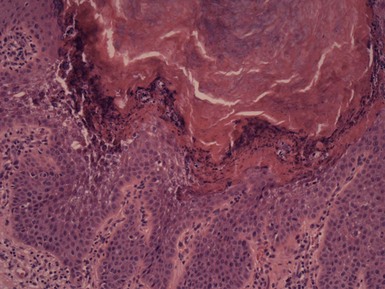

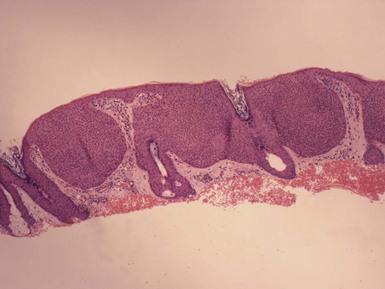

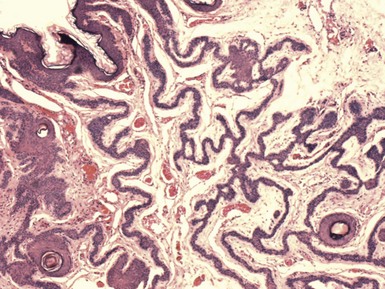

Microscopic Findings: There are aggregates of shadow cells that are arranged as columns projecting into cyst lumina, lie free within the lumina, or are present within pericystic connective tissue and associated with granuloma formation.15 When arranged as columns, the shadow cells appear to arise from basaloid, hair matrix-like cells within the cyst lining15 (Fig. 18-7). Narisawa and Kohda have also reported trichilemmal keratinization, sebaceous glands attached to the cyst wall, and epithelial islands that are positive for keratin 19 and contain keratin 20–positive Merkel cells. The latter changes are consistent with the “bulge” area of follicular epithelia and suggest that these cysts could arise from stem cells within the bulge region.17

Trichilemmal Cyst (Pilar Cyst, Isthmus-Catagen Cyst)

Clinical Features: Trichilemmal, or pilar, cysts commonly arise on the scalp, although they may also develop on the face, trunk, or extremities. Multiple cysts are not uncommon, particularly on the scalp, and the development of these cysts may be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Chromosomal mosaicism has been detected in a case of epidermal nevi associated with trichilemmal cysts.18 The microscopic appearance of trichilemmal cysts suggests that they originate from the midportion, or isthmus, of the hair follicle, the zone located between the follicular entry of the sebaceous duct and the insertion of the arrector pili muscle. In addition, ultrastructural studies by Kimura indicate a close resemblance between these cysts and the trichilemmal sac surrounding catagen follicles,19 hence the alternative name isthmus-catagen cyst. These cysts are also distinguishable from most epidermal cysts because of the relative ease of their surgical enucleation.

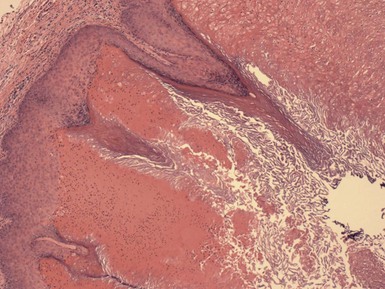

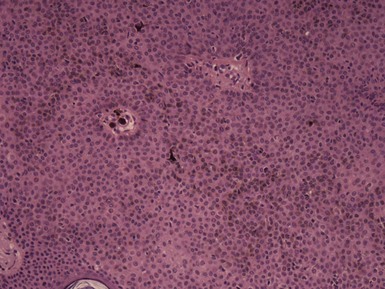

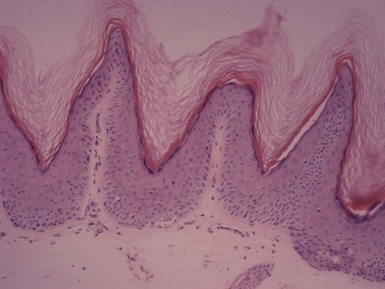

Microscopic Findings: Trichilemmal cysts are noteworthy because of the keratinization of their walls without the formation of a granular cell layer (although a few keratohyaline granules can occasionally be identified). Instead, cells progress from a distinctly palisaded basilar layer to a swollen, pale cell layer adjacent to the cyst lumen that contains homogeneous, eosinophilic keratin material (Fig. 18-8). As previously pointed out, this configuration closely resembles that of the follicular isthmus. Hybrid cysts also occur that can have mixed features of trichilemmal and epidermal (infundibular) cysts.20 Foci of calcification can be identified within the cyst lumen in about 25% of cases. Rupture of the cyst wall is occasionally observed, associated with a granulomatous response to cyst contents. Cyst rupture can be followed by repair of the defect, by marsupialization to the epidermis, with partial or complete resolution of the cyst, or by proliferation of the cyst wall (Fig. 18-9). The latter change may account for the proliferating trichilemmal cyst (proliferating trichilemmal tumor).21 There is a case report of a verrucous trichilemmal cyst containing HPV.22 Two recent reports of Merkel cell carcinomas associated with trichilemmal cysts suggest that this tumor may arise from the cyst wall; this is of interest because Merkel cells are frequently present in the isthmus region of follicular units.23,24

Proliferating Trichilemmal Cyst (Proliferating Trichilemmal Tumor, Pilar Tumor, Proliferating Pilar Tumor)

Clinical Features: Proliferating trichilemmal cysts are usually solitary tumors that most often occur on the scalp, particularly in middle-aged or elderly women. However, there can be multiple lesions25; they can arise in locations such as the trunk,6 arm,26 or hand27; they can occasionally be encountered in young individuals26; and they may occur in men (about 30% of cases).6 Proliferating trichilemmal cysts present as subcutaneous nodules or lobulated masses that may ulcerate or “marsupialize.” As the name implies, it is widely believed that these lesions result from repeated episodes of rupture and re-epithelialization of trichilemmal (pilar) cysts.21 Massive cutaneous horns of the scalp have also been reported to arise from proliferating trichilemmal tumors.28

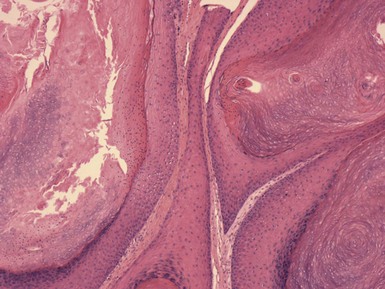

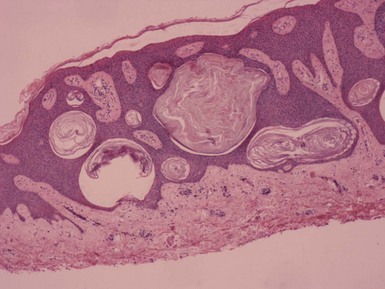

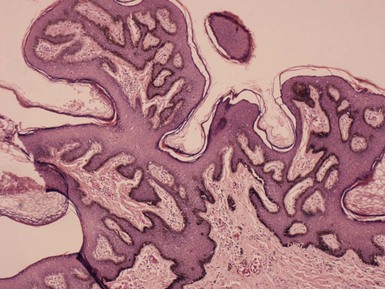

Microscopic Findings: There are lobules of squamous epithelium of varying sizes, some of which demonstrate peripheral palisading and distinct surrounding basement membrane material (see Fig. 18-9). Sometimes, these changes can be demonstrated to have arisen in the wall of a trichilemmal cyst.29 The islands of squamous epithelium demonstrate formation of amorphous eosinophilic keratin without the interposition of a granular cell layer, the characteristic feature of trichilemmal keratinization. Occasionally, keratinization of the infundibular type can also be identified, resulting in the configuration of a “hybrid” proliferating cyst.7 Other findings include apocrine or sebaceous (primary epithelial germ) differentiation,30 squamous eddy formation, calcification, and foci of clear cell change that demonstrate differentiation toward outer root sheath epithelium. A degree of nuclear pleomorphism can be identified, along with a mitotic rate of up to one per high-power field (hpf) and/or small foci of stromal infiltration. Such findings do occur in lesions that otherwise show benign biologic behavior. Recurrences have been reported; therefore, complete excision is indicated for these lesions.

Differential Diagnosis: Proliferating trichilemmal tumors can be mistaken for SCC, and in the past some of these cases may have accounted for reports of SCCs arising in pilar cysts. Foci of trichilemmal keratinization, an adjacent pilar cyst, and limited cytologic atypia or mitotic activity are all features that tend to support a diagnosis of proliferating trichilemmal tumor.

The malignant proliferating trichilemmal (pilar) tumor (giant hair matrix tumor, trichochlamydocarcinoma) shows considerable clinical overlap with the proliferating trichilemmal cyst, although it is most common in older women and averages 4 cm in diameter or greater. There is a histopathologic resemblance to the proliferating trichilemmal cyst, or evidence that it has arisen in a proliferating trichilemmal cyst, but the malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor has several characteristic features that set it apart: namely, squamoid or basaloid cells showing little tendency toward pilar differentiation, conspicuous nuclear atypia, high mitotic activity (four to five per hpf), dyskeratotic cells, foci of necrosis, and stromal invasion31 (see Chapter 19, Fig. 19-27A and B). One metastasizing tumor showed areas of transition from proliferating trichilemmal cyst to spindle cell carcinoma.32 Recognition of these tumors is important, because they are capable of regional lymph node metastasis or visceral spread, and therefore wide local excision and close clinical follow-up are indicated.

Studies have demonstrated p53 positivity in a proliferating trichilemmal cyst as well as in a malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor.33 Nondiploid DNA content has been detected by flow cytometry in two of four proliferating trichilemmal cysts, and these results appeared to correlate with higher mitotic counts and increased staining with the Ki-67 monoclonal antibody.34 Takata and associates used PCR-based microsatellite loss of heterozygosity analysis to demonstrate complete loss of the wild type p53 in a trichilemmal carcinoma arising from a proliferating trichilemmal cyst.35 These types of analyses may eventually permit early identification of those histologically borderline proliferating trichilemmal tumors that are capable of greater biologic aggressiveness.

Steatocystoma

Clinical Features: In steatocystoma, there are one or more cystic papules or nodules measuring 1 to 3 cm in diameter. The multiple form, steatocystoma multiplex, can be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. These lesions arise most often on the trunk, scalp, face, and arms, tend to manifest during adolescence or early adult life, and occur equally in both sexes. They are generally flesh-colored, and on incision, they discharge an oily fluid. An association with pachyonychia congenita has repeatedly been described,36–38 and recently missense mutations in keratin 17 have been linked to both pachyonychia congenita type 2 and steatocystoma multiplex.39–41

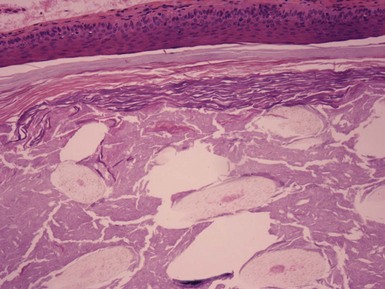

Microscopic Findings: The steatocystoma often has folded or undulating contours. The lesion has a lining composed of several layers of epithelial cells, and a distinct, eosinophilic cuticular layer lines the luminal surface. Small, flattened sebaceous lobules are demonstrated along the outer layer of the cyst wall (Fig. 18-10). Pale-staining, flocculent material is present within the cyst lumen, and occasionally small hair shafts are also observed. These features in aggregate suggest differentiation toward sebaceous ductal epithelium.42

Differential Diagnosis: As a rule, steatocystomas are easily distinguished microscopically from epidermal (infundibular) or trichilemmal cysts. The steatocystoma does have some resemblance to the dermoid cyst (see subsequent discussion). However, dermoid cysts are larger, tend to occur along embryonic lines of closure, have thicker walls, lack the thick cuticular luminal border, and contain prominent pilosebaceous or other adnexal elements. Eruptive vellus hair cysts (see later discussion) can clinically resemble steatocystoma multiplex but clearly have a structural relationship to the vellus follicle. Coexistence of vellus hair cysts and steatocystomas,43,44 and even hybrids of the two,45,46 have been described. A relationship between the two cysts seems reasonable, given the primary epithelial germ derivation of both hair follicle and sebaceous duct. This is further supported by the reported patterns of keratin expression for these cysts (keratin 17 for eruptive vellus hair cysts, keratins 10 and 17 for steatocystoma).47

Dermoid Cyst

Clinical Features: Dermoid cysts are subcutaneous cysts of ectodermal origin that arise along embryonic lines of closure. They are believed to be congenital lesions, but they may not become apparent until the second or third decades of life, resulting from episodes of rapid growth, inflammation, or trauma. They are most common in the head and neck region, particularly the supraorbital region, brow, upper eyelid, glabella, and scalp. They constitute the most common cause of periorbital mass lesions in infants and children.48 Dermoid cysts are more common in males than females. Sequestration of cutaneous epithelium during embryonic life is widely believed to explain the origin of these cysts; this may occur by several mechanisms, depending in part on the location of the cyst.49,50 These cysts present as subcutaneous swellings with either intact overlying epidermis or a depression connecting to a draining sinus tract. A collar of tufted hairs may surround scalp lesions. Cysts may be bound down due to attachment to periosteum, and those that rest on the dura or extend intracranially may fluctuate when a child cries. Infection, including bacterial meningitis, may be a complication, depending on the location of the cyst and its associated sinus tracts.

Microscopic Findings: On gross inspection, the dermoid cyst presents as a firm, tan cystic mass with protruding hair shafts and containing a yellow, oily material. Microscopic features include a cyst lined by stratified squamous epithelium, into which are inserted a number of small hair follicles (Fig. 18-11). The cyst lumen contains keratin debris and hair shaft fragments. Sebaceous glands are associated with the follicles and are usually not flattened against the cyst wall, as is the case in steatocystoma. Sweat glands, both eccrine and apocrine, can be identified in the vicinity of the cyst, and smooth muscle is present in up to one third of cases. This constellation of findings usually allows distinction from steatocystoma (see earlier discussion).

Differential Diagnosis: In addition to steatocystoma, the dermoid cyst should be distinguished from the recently described folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma. That tumor is more superficially located in the dermis, is less cystic, has more prominent sebaceous glands, and is not otherwise associated with hair follicles or other adnexal structures.42 The cystic teratoma is sometimes casually called a dermoid, but the latter lesion is rare in skin51,52 and has tissues derived from all three germ layers. Dermoid cysts also differ from the corneal and epibulbar dermoids that are associated with a variety of syndromes, such as the Goldenhar syndrome; these lesions consist mainly of dense, hyalinized connective tissue that may contain pilosebaceous units.

(Eruptive) Vellus Hair Cyst

Clinical Features: Esterly and coworkers first reported the condition eruptive vellus hair cysts in 1977.53 It is characterized by an eruption of yellow to brownish papules over the chest and proximal extremities in children and young adults. Lesions may be localized to the face, and there is a report of a solitary lesion that was associated with a melanocytic nevus and a conventional epidermal cyst.54 Spontaneous clearing after several years has been reported. The condition may be inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder.55

Microscopic Findings: There is an epithelial-lined cyst that contains keratin material and sections of vellus hairs.56 In addition to these vellus hairs, evidence of follicular origin includes invagination of the cyst wall by follicle-like elements or portions of a telogen follicle or arrectores pilorum muscle that may be observed to extend beneath the cyst. The cysts may communicate with the skin surface, discharging their contents, and granulomatous inflammation may be detected (Fig. 18-12); the latter changes may explain the crusting that is associated with some lesions.57 The microscopic findings suggest a developmental anomaly involving vellus follicles, with occlusion and cystic dilatation.53,58

Cutaneous Cysts and Related Structures That May Be Ciliated

There is a group of cysts or related structures that uncommonly occur in the skin and may feature ciliated epithelium. These include structures of possible müllerian or urogenital sinus origin (endometriosis, endosalpingiosis, mucinous and ciliated vulvar cysts, and cutaneous ciliated cysts), bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts, branchial cleft cysts, and thymic cysts. Median raphe cysts of the penis have also been rarely reported to contain cilia. Despite their differing modes or origin, these conditions are discussed here collectively because of this commonly held microscopic feature (see separate later discussion of the median raphe cyst).

Cilia have a characteristic cross-sectional appearance on ultrastructural examination, consisting of two central fibrils surrounded by nine double fibrils. This “9 + 2” arrangement is constant in cilia throughout the plant and animal kingdoms.59,60 However, cilia are not normal constituents of cutaneous epithelia, and their presence in the skin is distinctly unusual. There are several possible explanations for such a finding. Sequestration and migration during embryogenesis have been invoked as explanations for the “cutaneous ciliated cyst,” which often arises in the lower extremities, and for cutaneous bronchogenic cysts. “Cutaneous ciliated cysts” are believed by some to be of müllerian origin, as are the fallopian tubes, uterus, and upper one third of the vagina. Their appearance in the lower extremities may be explained by the common coelomic wall origin of limb buds and müllerian ducts during embryogenesis, with later migration of these müllerian elements within the developing limb,61 although other explanations have also been proposed. In the case of bronchogenic cysts, bronchial epithelium is known to derive from the ventral portion of the primitive foregut, and sequestrations from the foregut may migrate into the developing skin or be pinched off by subsequent fusing of sternal bars. Failure of regression of embryonic structures could play a role in the formation of some ciliated cysts. Dysontogenesis, or defective embryonic development, is theoretically possible. Embryonic sweat ducts and glands feature cilia at 16 weeks’ gestation,62 and therefore arrested sweat gland development could theoretically result in persistence of ciliated epithelia. Prosoplasia, or abnormal development resulting in a “higher” state of organization, has been suggested as an explanation for vaginal adenosis, the appearance of ciliated glandular epithelium in the vagina or vulva.63 Transplantation of tissue could occur following surgical procedures, via either direct inoculation or lymphatic or hematogenous metastasis. This mechanism has been proposed for cutaneous endometriosis. Finally, metaplasia of pluripotential cells to form ciliated epithelia is a theoretical explanation that has been proposed for endometriosis64 and for ciliated odontogenic keratocysts,65 although hard evidence for its role in producing ciliated cysts in skin is lacking.

Clinical Features: First described in the latter part of the 19th century, endometriosis occasionally arises in skin. Locations include the umbilicus, lower abdomen, inguinal region, labia, and perineum. Lesions are often present within surgical scars (especially cesarean section or laparotomy scars). They are typically papules to small nodules (approximately 5 mm in diameter) and brownish in color, although they may appear bluish-black due to cyclical bleeding. A statistical association between a history of endometriosis and risk of melanoma has been reported in a recent study.66

Microscopic Findings: Microscopically, there are combinations of glands and stroma, the former showing the characteristic features of uterine endometrium expected during proliferative, secretory, or menstruation phases of the menstrual cycle (Fig. 18-13). Cilia may sometimes be identified. However, one study has shown a poor correlation between the histologic features of these lesions and the actual stage of the menstrual cycle.67 Estrogen and progesterone receptor and CD10 positivity support the diagnosis.68

Differential Diagnosis: Decidualized changes can sometimes be encountered, particularly in lesions detected during pregnancy, and such lesions have occasionally been confused with malignancy69 (Fig. 18-14). Similar problems can arise when fine needle aspiration biopsies are performed.70

Endosalpingiosis

This rare condition is characterized by the development of brown papules (apparently resembling nonhemorrhagic lesions of cutaneous endometriosis) in a periumbilical distribution following salpingectomy. Abdominal pain has been associated with this lesion.71 Microscopically, there is a cyst lined by columnar epithelial cells, some of which are ciliated. Papillary projections are present within the lumen. These features resemble fallopian tube as well as the “cutaneous ciliated cyst” (see subsequent discussion).72

Mucinous and Ciliated Vulvar Cyst

Mucinous and ciliated cysts occur in the vulvar region. Their origin has been the subject of debate. Robboy and colleagues found small mucinous glands in 53% of vulvas examined at autopsy, and in addition, they encountered 11 cysts in clinical practice that featured varying combinations of mucinous and/or ciliated epithelium. These researchers suggested that glands lined by mucinous or ciliated epithelium are normal vulvar constituents and that cysts develop due to inflammation and obstruction of their outlets.63 They and others73 have favored origin from entoderm of the urogenital sinus, although müllerian origin or metaplasia of apocrine glands have also been considered.74 These cysts are lined by cuboidal to tall columnar or pseudostratified columnar epithelium with variable amounts of mucin and/or cilia (Fig. 18-15). Squamous metaplasia and neutrophilic infiltration of cyst walls have also been reported.63,73,74

Cutaneous Ciliated Cyst

Hess first reported this type of ciliated cyst in 1890,75 and Farmer and Helwig later defined it as a distinct entity.76 These cysts usually present as solitary lesions on the lower extremities and most commonly occur in women. Similar lesions have been reported on the sole of the foot, finger, knee, buttock, umbilicus, inguinal area, scrotum, scapular area, and scalp, and there have been at least three reported cases in men.77,78 The cysts may extend to several centimeters in diameter, are unilocular or multilocular, and on incision contain a clear or serous fluid. Microscopically, the cyst is lined by cuboidal or columnar ciliated epithelium, arranged in folds or papillary projections (Fig. 18-16). Mucinous cells are usually not observed but have been reported.79 The lining resembles that of a fallopian tube. Immunohistochemical staining is positive for epithelial membrane antigen, CAM 5.2, and AE1/AE3, and is negative for carcinoembryonic antigen, similar to the results seen in normal fallopian tube; positive staining for estrogen or progesterone receptors has been reported.80 As previously discussed, müllerian origin for these cysts has been favored; immunohistochemically, they appear to be unrelated to eccrine sweat glands.81

Bronchogenic Cyst

Bronchogenic cysts occur in both males and females and are usually first recognized early in life. They usually occur as solitary dermal or subcutaneous nodules over the suprasternal notch or manubrium sterni; however, other locations have been reported, including the scapular area, shoulder,82 chin,83 and back.84 These lesions have firm cyst walls that contain a clear fluid. Bronchogenic cysts are lined by cuboidal to columnar ciliated epithelia that may be pseudostratified. The lining epithelium may form folds or papillary projections into the lumen. Goblet cells are usually present (Fig. 18-17), and the stroma may include smooth muscle, mucous glands, or cartilage. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate is sometimes present.85

Thyroglossal Duct Cyst, Branchial Cleft Cyst, and Thymic Cyst

These cysts do not generally fall within the purview of the dermatologist or dermatopathologist, but they occasionally have cutaneous manifestations and each may contain cilia. The thyroglossal duct cyst arises from embryonic remnants of the duct that remain after the descent of the developing thyroid gland. It is usually located near the hyoid bone, and infection or formation of a cutaneous fistula brings it to the attention of the patient and physician. These cysts may be associated with thyroid follicles and lack smooth muscle or cartilage in their walls86 (Fig. 18-18A). Branchial cleft cysts typically occur on the lateral neck, are lined by stratified squamous and/or columnar epithelium, and have walls containing lymphoid tissue87 (see Fig. 18-18B). Thymic cysts are believed to arise from embryonic remnants of the thymopharyngeal duct and may be present in the neck. They bear a microscopic resemblance to the bronchogenic cyst but lack goblet cells and contain thymic tissue and cholesterol granulomas in the surrounding stroma88 (see Fig. 18-18C).

Figure 18-18 Thyroglossal duct cyst, branchial cleft cyst, and thymic cyst. A, Thyroglossal duct cyst—thyroid follicles can be seen to the right. B, Branchial cleft cyst—this portion shows a stratified squamous epithelial lining and surrounding lymphoid tissue. C, Thymic cyst—dense lymphoid tissue and a Hassall corpuscle can be seen.

Other Cutaneous Cysts

These lesions most often arise in areas subjected to surgical or other types of trauma, although one reported case was associated with a BCC with no trauma history.89 Other associations may include chronic inflammatory states such as rheumatoid arthritis90 or heritable disorders of connective tissue such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.91 Recurrence following excision has been reported.92 Microscopically, the changes are identified at varying levels of the dermis and may connect to the cutaneous surface. They consist of cystic structures with villous protrusions within the lumina, lined by a thin fibrinous exudate. The connective tissue cores consist of loosely organized connective tissue, prominent vessels, and spindled to epithelioid cells (Fig. 18-19). These changes bear a close resemblance to hyperplastic synovium. Immunohistochemical staining is generally negative except for vimentin positivity among lining and stromal cells. Although some lesions bear a slight resemblance to digital mucous cyst, the constellation of features is relatively distinctive.

Median Raphe Cyst

Median raphe cysts are most often encountered in young men but can present in boys or older men as well. They typically occur along the ventral portion of the penis, particularly in the region of the glans, but can arise anywhere along the median raphe, including the perianal region.93 They are usually solitary, but multiple lesions can occur.94 The presenting complaint is usually of a mass or distortion of penile contour. Histologically, these cysts are lined by pseudostratified columnar epithelium that variably contains mucous cells95,96 (Fig. 18-20). Cilia have also been reported.97 Thus, these cysts have a urothelial lining, a conclusion supported by positive staining for keratin 13.98 Serotonin-containing cells have also been reported in these cysts.99 Theories of their origin have included failure of closure of the median raphe or derivation from the periurethral glands of Littre. Sequestration of ectopic urethral mucosa during embryonic development seems a reasonable explanation.96

Omphalomesenteric Duct Polyp

During early embryonic development, the omphalomesenteric duct communicates between the midgut and the yolk sac. It typically disappears during the seventh week of development, but persistence results in polyp, sinus, or cyst formation. This may present as a red umbilical polyp that is usually noted soon after birth or in early childhood. A central depression indicates an underlying sinus or cyst. Pyogenic granuloma is sometimes suspected clinically, although bleeding and exudation are not typical features.100 Histologically, the polyp contains branching epithelium that may have the appearance of gastric or small or large intestinal mucosa, sometimes with connections to the epidermal surface (Fig. 18-21). Aberrant pancreatic tissue has been reported in one case.101 Other findings include smooth muscle, lymphoid nodules,102 varying degrees of erosion, acanthosis, inflammation, and vascular proliferation.103 Definitive removal of these lesions should be preceded by studies to rule out associated anomalies, such as enteric fistulae or Meckel diverticulum.100,104 There has also been a rare report of an umbilical polyp associated with urachal rather than omphalomesenteric remnants.105

Benign Epidermal Tumors or Malformations

Clinical Features: Epidermal nevi generally manifest as verrucous papules that are either present at birth or develop during early childhood, although adult onset has been documented. Papules may be solitary or arranged in clusters that often assume a linear configuration. Extensive linear lesions are said to follow Blaschko lines. Several names have been applied to clinical variants, including nevus unius lateris for unilateral lesions and ichthyosis hystrix for bilateral systematized lesions. An epidermal nevus syndrome has been proposed, linking extensive epidermal nevi with abnormalities of the central nervous and cardiovascular systems, eyes, and skeleton. Some of these patients also have other cutaneous findings, including nevocellular nevi, café au lait spots, and hemangiomas. This syndrome may be congenital or show autosomal dominant inheritance.106,107 However, Happle disputes the concept of a single epidermal nevus syndrome, because several different birth defects can be associated with epidermal nevi.108

Variants of epidermal nevi include nevoid hyperkeratosis of the nipple, nevus comedonicus, and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN). In nevoid hyperkeratosis of the nipple, verrucous change resembling epidermal nevus involves one or both areolae.109,110 In nevus comedonicus, there are linear arrangements of comedones, sometimes with small cysts, abscesses, or fistulae that tend to form on the trunk. An association with other stigmata of the epidermal nevus syndrome has been reported. In ILVEN, lesions commonly occur on the lower extremities of females but can be seen in other locations and in males. These lesions are typically inflamed and pruritic, and they have a clinical appearance suggesting linear psoriasis.

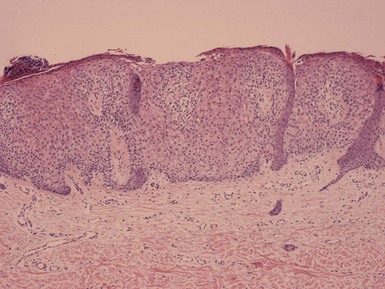

Microscopic Findings: The most typical microscopic features of epidermal nevi include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis. The papillomatosis may be irregular, and flattening of the surfaces of the papillary projections (the “mesa” sign) is sometimes encountered (Fig. 18-22). Regular, “church-spired” papillomatosis such as encountered in acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf or stucco keratosis can sometimes be observed. Changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis are sometimes present, especially in the clinical variant known as ichthyosis hystrix. Less commonly, there are changes of acantholytic dyskeratosis resembling Darier disease. These include suprabasilar acantholysis and formation of dyskeratotic keratinocytes.111,112 Such lesions have sometimes been designated acantholytic, dyskeratotic epidermal nevus. In a study by Submoke, 62% of epidermal nevi had the typical hyperkeratosis-papillomatosis-acanthosis configuration, whereas 16% showed changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.113 Nevoid hyperkeratosis of the nipple also shows varying degrees of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis (Fig. 18-23). In nevus comedonicus, there are dilated follicles filled with keratin in the manner of comedones, sometimes with milia formation or proliferations of the lining epithelium (Fig. 18-24). Changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis have also been reported in these lesions.114 Lesions of ILVEN show psoriasiform acanthosis with an underlying perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Spongiosis may be present. A characteristic feature of these lesions is the presence of alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis. Parakeratosis is associated with papillary projections of epidermis and absence of a granular layer, whereas orthokeratosis is found in adjacent epidermal invaginations, accompanied by hypergranulosis (Fig. 18-25). With immunohistochemical staining, there is increased involucrin expression in areas of orthokeratosis and negative expression in areas of parakeratosis.115

Figure 18-22 Epidermal nevus. This lesion is papillomatous and also features flattening of the papillary projections. Basilar hypermelanosis is present.

Differential Diagnosis: Differential considerations include verrucae, seborrheic keratoses, and other papillomatous lesions such as acanthosis nigricans and confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud. Old verrucae may lack the typical viropathic changes or the “in-bowing” of epithelial margins seen in well-developed viral lesions, and the papillomatosis displayed by these lesions can closely mimic that of epidermal nevi. Changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis can also superficially mimic the viropathic changes of HPV infection. However, in such cases, the absence of characteristic koilocytic cells with “raisenoid” nuclei and possible extension of vacuolated changes deep within the epidermis favor epidermal nevus. The close-set basaloid cells and pseudohorn cysts of seborrheic keratosis are usually characteristic, but hyperkeratotic varieties with marked papillomatosis and lacking horn cysts can certainly resemble epidermal nevi. In fact, some regard the seborrheic keratosis as a kind of “tardive” epidermal nevus. Nevertheless, a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis should not be made in children and only with caution in young adults; most lesions in these groups probably represent either epidermal nevi or verrucae. Acanthosis nigricans as well as confluent and reticulated papillomatosis have lesser degrees of hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis than ordinarily encountered in epidermal nevi, and in any event the clinical features should help exclude these diagnoses in most instances. Nevoid hyperkeratosis of the nipple can mimic one of the distribution patterns of acanthosis nigricans; greater degrees of epidermal change and lack of involvement in other locations tend to exclude acanthosis nigricans in such cases. ILVEN can resemble psoriasis microscopically as well as clinically. However, the presence of alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis is not typical of psoriasis, and the pattern of involucrin expression differs as well, because in psoriasis, most suprabasilar keratinocytes are positive for involucrin.116

Acantholytic Acanthoma

Clinical Features: Acantholytic acanthoma is an uncommon lesion that presents as a papule or small nodule. It is often a solitary lesion, but multiple lesions have also been reported. Multiple lesions have occurred in the genital region. Not surprisingly, the precise diagnosis is rarely made clinically.

Microscopic Findings: Acantholytic changes are observed that can mimic pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus foliaceus, or Hailey-Hailey disease (familial benign chronic pemphigus). Changes of acantholytic dyskeratosis, as seen in Darier disease, were not emphasized in original reports but definitely occur and may even be common.117 Thus, this lesion can show a spectrum of changes analogous to those of transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease). In fact, the acantholytic acanthoma may be part of a spectrum of lesions that show varying combinations of acanthosis, acantholysis, or dyskeratosis (Fig. 18-26). The following list of entities demonstrates the variety of histopathologic features that can be seen in not dissimilar clinical lesions:

Differential Diagnosis: The clinical presentation of one or a few discrete lesions usually allows distinction from the other acantholytic dermatoses listed previously (see “Microscopic Findings”). One possible exception is the form of pemphigus foliaceus that resembles eruptive seborrheic keratoses.120 Direct immunofluorescence may be helpful in such cases, because positive intercellular fluorescence is found in pemphigus, whereas negative immunofluorescence is expected in acantholytic acanthoma and its variants.121–123

Epidermolytic Acanthoma

Clinical Features: Epidermolytic acanthoma is usually a solitary lesion less than 1.0 cm in diameter. There may be a few lesions or, rarely, disseminated small, flat brown papules located over the trunk. Slight atrophy has been reported, and the lesions may clinically resemble seborrheic keratoses.124,125

Microscopic Findings: The changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis are observed: hyperkeratosis and vacuolization of cells of the granular and suprabasilar layers of epidermis with formation of large and/or irregularly shaped keratohyalin granules (Fig. 18-27). These microscopic changes are characteristic of the dominantly inherited form of ichthyosis, which is also known as epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (formerly, bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma). They can also be observed in some epidermal nevi (see earlier discussion), forms of hyperkeratosis of palms and soles, or in skin biopsy specimens as an incidental finding. One immunohistochemical study showed reduced keratin K1 and K10 staining but expression of hyperproliferative keratins, such as K16, in both lesions and perilesional normal skin.126 The lesions have been negative for HPV DNA.127

Differential Diagnosis: The clinical presentation of the lesion rules out other disorders that show changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Microscopically, verrucae have similar features, but unlike verrucae, the epidermolytic acanthoma typically lacks parakeratosis and may show vacuolization that extends close to the basilar layer.124,128

Warty Dyskeratoma

Clinical Features: The lesion presents as a papule or small nodule with associated crust and a central keratotic plug. It most commonly arises on the face, neck, scalp, or in the axilla.129 Oral mucosal lesions have also been frequently described in the literature,130 and a subungual lesion has also been reported.131 Although the warty dyskeratoma is most often solitary, multiple lesions can occur.132,133

Microscopic Features: Microscopically, there is a cup-shaped invagination of the epidermis filled with keratin. The epithelial lining shows suprabasilar acantholysis with formation of villi and dyskeratotic cells along its surface134,135 (Fig. 18-28A and B). The two best-known forms of dyskeratosis are the corps ronds and the grains. Corps ronds feature a pyknotic nucleus surrounded either by a clear halo or by dense eosinophilic material. Grains resemble plump parakeratotic nuclei. Both cell types are typical of lesions characterized by acantholytic dyskeratosis, including (in addition to warty dyskeratoma) the prototype genodermatosis, Darier disease (keratosis follicularis); Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis); certain epidermal nevi (acantholytic, dyskeratotic epidermal nevi); and acantholytic, dyskeratotic acanthoma. Focal acantholytic dyskeratosis can also be encountered as an incidental finding in biopsy specimens obtained for unrelated reasons.

Differential Diagnosis: The characteristic cystic invagination of epidermis, combined with acantholytic and dyskeratotic changes, gives the warty dyskeratoma a unique diagnostic appearance. However, shallow lesions may resemble, or in fact be examples of, acantholytic dyskeratotic acanthoma, whereas a cystic invagination of proliferative epidermis without acantholytic or dyskeratotic changes may actually represent dilated pore or pilar sheath acanthoma.

Seborrheic Keratosis and Its Variants

Clinical Features: Seborrheic keratoses are extremely common lesions among adults. They are benign lesions that are often removed, even by nonsurgical means, such as cryotherapy, for cosmetic reasons. However, they can clinically mimic both premalignant and malignant lesions. In addition, they can sometimes show histopathologic features that raise concerns about malignancy, and occasionally malignant cutaneous tumors (e.g., SCC, malignant melanoma) actually do arise in association with seborrheic keratoses. These facts underscore the importance of a familiarity with the microscopic appearance of the seborrheic keratosis and its variants.

Seborrheic keratoses are rough-surfaced papules, nodules, or plaques that occur especially on the trunk but can involve virtually any cutaneous surface except the palms and soles. These lesions typically begin to develop during the fourth or fifth decades and may become quite numerous. Although they usually do not exceed 3 cm in diameter, they can occasionally form annular plaques that are considerably larger. Seborrheic keratoses arise de novo or in preexisting lentigines. Increased numbers of keratoses may develop, even in an eruptive fashion, in association with weight gain or exfoliative erythroderma. The sign of Leser-Trélat is the rapid appearance of pruritic seborrheic keratoses in association with internal malignancy, most often adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract; this sign is also often associated with acanthosis nigricans.136 There is some dispute about whether this sign results from a true increase in seborrheic keratoses or from a host inflammatory response to existing but (in some cases) subtle seborrheic keratoses, giving the impression of a rapid increase in numbers of lesions.

Several clinical variants of seborrheic keratoses have been described. Often heavily pigmented, taglike seborrheic keratoses are common in the malar regions of African-American individuals and are termed dermatosis papulosa nigra. Multiple small, slightly elevated, flesh-colored papules termed stucco keratoses are frequently observed over the distal extremities. Other variants of seborrheic keratoses are partly defined by their unique histopathologic features; these include irritated seborrheic keratosis, inverted follicular keratosis, “clonal” or nested seborrheic keratosis, and melanoacanthoma.

Microscopic Findings: Seborrheic keratoses show varying combinations of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis. The involved epidermis is often sharply demarcated at its base, forming a straight line that is continuous with the adjacent, uninvolved epidermis; this is a reflection of the exophytic nature of most of these lesions. Characteristically, seborrheic keratoses are composed of close-set basaloid cells and pseudohorn cysts. The latter are cystic invaginations of the epithelium filled with surface keratin, which in a given microscopic section may be cut in cross-section, thereby appearing as “cysts” within the involved epidermis.

Seborrheic keratoses are often divided into three major types: hyperkeratotic, acanthotic, and reticulated. Hyperkeratotic seborrheic keratoses show pronounced papillomatosis, which may be of the digitate or “church-spired” type, the latter showing regular, pointed epidermal projections (Fig. 18-29). Acanthotic lesions are mainly characterized by marked epidermal thickening (Fig. 18-30). Reticulated types show down-growth of interconnecting narrow epidermal tracts (Fig. 18-31). The latter type can often be demonstrated to arise in association with solar lentigines. As might be expected, mixtures of these three configurations can occur.

Figure 18-29 Seborrheic keratosis, hyperkeratotic type. This lesion shows hyperkeratosis and pronounced, “church-spired” papillomatosis. Stucco keratoses have similar features.

Figure 18-30 Seborrheic keratosis, acanthotic type. Features include marked acanthosis, composed of close-set basaloid cells and pseudohorn cysts.

Figure 18-31 Seborrheic keratosis, reticulated type. This lesion features downgrowth of interconnecting narrow cords of epithelial cells.

The lesions of dermatosis papulosa nigra combine features of seborrheic keratosis and fibroepithelial polyp, with basilar hypermelanosis (Fig. 18-32). Stucco keratoses feature regular, “church-spired” papillomatosis, thereby qualifying as hyperkeratotic seborrheic keratosis variants. Seborrheic keratoses sometimes become inflamed or irritated. Hemorrhagic scale-crust formation, surface neutrophilic accumulation (sometimes producing spongiform pustulation), erosion or ulceration, and dermal inflammation with exocytosis are often encountered. Other lesions may have minimal inflammation but show marked spongiosis, sometimes sufficient to result in mild acantholysis, and “squamous eddies,” consisting of whorls of flattened keratinocytes with a superficial resemblance to the horn pearls of SCC. Lesions with the latter changes are known as irritated seborrheic keratoses (Fig. 18-33). A distinction has been made between “inflamed” and “irritated” seborrheic keratoses, because lesions with spongiosis and squamous eddies can be produced by experimental irritation in the absence of inflammation. The inverted follicular keratosis also features spongiosis and squamous eddy formation, with a distinctly endophytic growth pattern that can be arranged around a central, keratin-filled invagination. This endophytic configuration is a reasonably unique feature of these lesions, although some authors consider it simply a variant of “irritated seborrheic keratosis”137 (Fig. 18-34). Nested (“clonal”) seborrheic keratosis contains discrete clusters of keratinocytes, an example of the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon. Some authors prefer the modifier “nested” to “clonal,” because there is no evidence that the keratinocyte nests represent true “clones” of cells in the genetic sense (Fig. 18-35). Melanoacanthomas are seborrheic keratoses that contain numerous dendritic melanocytes, accentuated by their melanin content. Melanosomes fill the cytoplasm and dendritic processes of melanocytes, but there is incomplete transfer of pigment to surrounding keratinocytes (the “constipated melanocyte”) (Fig. 18-36); this can be nicely demonstrated with the Fontana-Masson stain.138 A similar process occurs in a variety of other clinical settings (e.g., as a mucous membrane lesion, in clear cell acanthomas (see subsequent discussion), or as a manifestation of the hypopigmentation in sarcoidosis); therefore, it may be best to regard “melanoacanthoma-type” change as a phenomenon rather than a specific clinicopathologic entity.

Figure 18-32 Dermatosis papulosa nigra. The lesion combines features of seborrheic keratosis, with basilar hypermelanosis, and fibroepithelial polyp.

Figure 18-33 Irritated seborrheic keratosis. Findings include neutrophilic scale-crust, marked spongiosis with mild acantholysis, and formation of squamous eddies.

Figure 18-34 Inverted follicular keratosis. The lesion has features of irritated seborrheic keratosis but with a distinctly endophytic configuration.

Differential Diagnosis: The majority of seborrheic keratoses are readily diagnosable, but there are differential diagnostic considerations, some of which are relatively trivial, but a few of which are of greater diagnostic import. The lesions of acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, a dominantly inherited condition characterized by verrucous papules on distal extremities, typically show “church-spired” papillomatosis that is virtually indistinguishable from hyperkeratotic forms of seborrheic keratosis, especially stucco keratosis. Occasionally, foci of acantholysis can be identified in these lesions. In addition, clinical history is important here, in that lesions of acrokeratosis verruciformis begin at birth, during childhood, or at puberty, whereas seborrheic keratoses have a much later time of onset. Flegel disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans) consists of flat, hyperkeratotic papules that commonly arise on the lower legs and feet.139 Autosomal dominant transmission has been reported. Microscopically, these again may closely resemble hyperkeratotic seborrheic keratoses. Lesions showing compact orthokeratosis, flattening of the underlying epidermis, and acanthosis or papillomatosis at their margins are reasonably characteristic of Flegel disease. There may also be a dense lichenoid infiltrate in the upper dermis. In addition, a family history may be of some diagnostic help. The inverted follicular keratosis has an architectural resemblance to trichilemmoma, another lobulated, endophytic epithelial tumor that may be arranged about a central follicular structure. However, the latter tumors feature clear cells (due to the presence of glycogen), a distinctly palisaded basilar layer, and a surrounding cuticular basement membrane. Although a distinction between these two lesions per se is not a crucial one, recognition of trichilemmoma may be important because of its association with the cancer-associated syndrome, Cowden disease.

Many of the seborrheic keratosis variants can resemble verrucae, particularly because the latter do not always possess easily recognizable viral inclusions or other viropathic changes. As an example of this dilemma, studies of seborrheic keratoses of the genital region have revealed the presence of HPV in these lesions.140 On the other hand, similar investigations of inverted follicular keratoses have generally been negative. In the absence of supporting data, it is probably best to acknowledge the possibility of verrucae when faced with borderline lesions. Seborrheic keratosis–like lesions in children are more likely to be either verrucae or epidermal nevi (see “Epidermal Nevi”).

Dermatopathologists frequently encounter hyperkeratotic lesions that are more squamoid than basaloid; that lack pseudohorn cysts; and may have varying degrees of irregular papillomatosis, acanthosis, or scale-crust formation. These less than diagnostic lesions are often signed out as seborrheic keratoses, verrucae, or simply as “acanthomas.” This would seem to be a reasonable approach in the absence of clinical data to the contrary. Of greater concern are those seborrheic keratoses that mimic premalignant or malignant epidermal tumors. Acanthotic seborrheic keratoses comprised of close-set basaloid cells can resemble the variant of Bowen disease that displays minimal keratinocyte pleomorphism. In such instances, careful evaluation of lesional keratinocytes is crucial: subtle loss of maturation, variability of nuclear size, formation of multinucleate cells, and frequent mitotic figures at all levels of the epidermis would be clues pointing towards Bowen disease as the correct diagnosis. Nested seborrheic keratoses resemble other lesions typified by the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, especially benign or malignant hidroacanthoma or Bowen disease with a nested configuration. Hidroacanthomas are basically intraepidermal poromas. The nests are composed of close-set cells with small nuclei that contain glycogen, which is not the case in seborrheic keratoses. Special staining sometimes demonstrates sweat gland differentiation in these tumors. Significant pleomorphism and atypia among nested cells may indicate malignant hidroacanthoma, whereas Bowen disease with nesting often shows foci of more typical, non-nested Bowen disease in other portions of the lesion.

Another concern is the problem of the irritated seborrheic keratosis and its differentiation from hypertrophic actinic keratosis or SCC. Occasionally, a lesion with scale-crusting, squamous eddy formation, and spongiosis also shows degrees of keratinocyte atypia, mostly manifested by nuclear hyperchromasia, variation in nuclear size, and scattered mitotic figures. In such instances, distinction from SCC can be problematic. In the authors’ experience, this situation arises most often (but not invariably) in elderly individuals. These lesions require particularly close attention to architectural and cytologic details. Irritated seborrheic keratoses show limited pleomorphism, absence of atypical mitoses, and lack of significant atypia in lower epidermal layers and basilar keratinocytes. On the other hand, significant nuclear enlargement, atypical mitoses, acantholytic changes not associated with obvious spongiosis, and basilar keratinocyte atypia favor SCC. Most often, the diagnosis can be established with confidence using these guidelines, but there are occasional lesions that defy accurate classification. This often occurs in the case of shaved lesions, where the entire base cannot be visualized. In these instances, it is probably best to identify the lesion as an irritated seborrheic keratosis with atypical features, and assurance of complete removal should be recommended. As further support for this conservative approach, malignancies have been reported to arise within, or adjacent to, seborrheic keratoses, including BCCs, Bowen disease, well-differentiated SCCs, and malignant melanomas.141–144

Large-Cell Acanthoma

Clinical Features: Large-cell acanthomas are relatively common lesions of middle-aged to older adults. Lesions are flat to slightly elevated, hyperpigmented patches with sharply demarcated borders, measuring less than 1.0 cm in diameter.145 One or several146 lesions may be present, typically arising on the head and neck, trunk, and extremities. Conjunctival involvement has also been reported.147 There is some controversy regarding the histogenesis of these lesions. Some authors regard them as variants of solar lentigines,148 whereas others believe they reflect a degree of keratinocyte atypia analogous to actinic (solar) keratoses.149 Image analysis cytometry by Argenyi and associates showed significant aneuploidy in large-cell acanthomas, but there was a lack of evidence of significant proliferation by immunohistochemistry, with a mean DNA index between those of actinic keratosis and Bowen disease. These authors concluded that the results do not resolve the classification controversy regarding large-cell acanthomas.150

Microscopic Findings: Large-cell acanthomas show basket-woven hyperkeratosis and a prominent granular cell layer. Lesions may be papillomatous and have plump rete ridges, or they may be relatively flat both at the surface and along the dermal-epidermal interface.145 A key feature is the presence of both nuclear and cytoplasmic enlargement of involved keratinocytes (Fig. 18-37), sharply demarcated from normal adnexa (follicular infundibula and acrosyringia) and adjacent epidermis. Slightly increased basilar pigmentation may be encountered.

Clear Cell Acanthoma

Clinical Features: Degos first described the entity known as clear cell acanthoma, or pale cell acanthoma (an alternative and probably more accurate designation).151 The lesions usually occur in adults older than 40 years of age. They manifest as circumscribed red nodules with peripheral scale, measuring about 1.0 cm in diameter, presenting as slowly growing, asymptomatic lesions on the leg. Other sites of involvement include the abdomen, umbilicus152 and scrotum. Clear cell acanthomas are often solitary, but several, or multiple, lesions can occur,153,154 and an eruptive form has been described.155 The red, exudative surface with collarette of scale produces a clinical resemblance to pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma).156 Although usually classified as a tumor, they have some psoriasis-like pathogenetic features, including increased levels of keratinocyte growth factor and down-regulation of the high-affinity tyrosine kinase receptor for keratinocyte growth factor; this indicates that clear cell acanthoma has some characteristics of a hyperproliferative inflammatory process.157

Microscopic Findings: There is acanthotic epithelium composed of cells with pale-staining cytoplasm. Prominently pigmented melanocytic dendrites may be present, a finding indicative of the “melanoacanthoma” phenomenon.158 The configuration of the involved epidermis may be acanthotic, exophytic, or psoriasiform.159 The involved epithelium is particularly sharply demarcated from adjacent normal epidermis and from adnexal epithelium, a feature of significant diagnostic importance (Fig. 18-38). At the surface there may be parakeratosis or erosion, and collections of neutrophils may be evident.160 The dermis features vasodilatation and a lymphocytic infiltrate of variable intensity. The keratinocytes of clear cell acanthoma contain glycogen and show absence or diminished content of respiratory enzymes such as phosphorylase, cytochrome oxidase, and succinic dehydrogenase.161 More recent studies showing positive involucrin162 and negative carcinoembryonic antigen163 staining argue against a sweat gland origin for this tumor, whereas lectin-binding sites are similar to those of normal epidermis.164

Differential Diagnosis: The microscopic features of clear cell acanthoma are unique. Lesions can closely resemble psoriasis, but the sharp demarcation from adjacent epidermis and adnexal sparing are features not encountered in psoriasis. Seborrheic keratoses lack pale-appearing keratinocytes, possess pseudohorn cysts, and are often hyperkeratotic and hypergranulotic; furthermore, they do not show the sharp demarcation that is the hallmark of clear cell acanthoma. Eccrine poroma can have similar clinical features, including a location on the distal extremities, and microscopically, sharp demarcation of tumor from adjacent epidermis is also a characteristic of poromas. However, in contrast to clear cell acanthoma, these lesions are typically composed of small, close-set, cuboidal cells.

Clear Cell Papulosis

Clinical Features: Only a few cases of this unusual lesion have been reported; it is described mainly in children in Taiwan.165–167 Whitish papules develop along the milk lines, over the abdomen and pubis. Lesions of the lumbar areas and buttocks have also been reported. Clear cell papulosis lesions are asymptomatic, and many of them regress over a period of years.168

Microscopic Findings: The lesions are comprised of pagetoid clear cells within the basilar layer of the epidermis, associated with hypomelanosis (Fig. 18-39). The clear cells stain positively for mucin, and on immunohistochemical staining are found to express AE1/AE3, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and gross cystic disease fluid protein-15,165,169 thereby having the characteristics of Paget disease cells and of Toker clear cells of the nipple.169 It has been suggested that these cells could serve as precursors for mammary and extramammary Paget disease.167 Melanocytes are reported to be normal, although a lack of melanosomes has been noted in superficial portions of the epidermis.167

Pseudoepitheliomatous Hyperplasia

Clinical Features: Non-neoplastic proliferation of epidermis, with extension deep into the dermis, can be sufficiently pronounced to raise concerns about a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. This phenomenon is termed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Such extensive epidermal proliferation can be encountered as a manifestation of halogen ingestion (halogenoderma, including bromoderma and iododerma) or in association with infectious diseases. The prototypical infection showing pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia is North American blastomycosis, but virtually identical changes can occur in other deep fungal infections (South American blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, coccidioidomycosis, chromomycosis, sporotrichosis) as well as infections due to bacteria (blastomycosis-like pyoderma, atypical mycobacterial infection) or achloric alga (protothecosis). Other lesions showing pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia include hidradenitis suppurativa, skin adjacent to chronic ulcers, prurigo nodularis, and tumors such as Spitz nevi, BCC, and granular cell tumors. Marked acanthosis and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia can also accompany true SCCs; such changes are often observed in lesions from acral sites, such as the dorsa of the hands or lower legs.

Microscopic Findings: There is marked proliferation of the epidermis, the base of which may have irregular, jagged contours (see Figs. 1-16 and 1-17). Horn pearls are sometimes present, and mitotic figures may be numerous. Infiltration of involved epidermis by neutrophils and/or eosinophils, sometimes with intraepidermal microabscess formation, is a feature that favors pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia; this is especially common in those cases caused by infectious agents or drugs. Accompanying granulomatous inflammation also favors infection; this finding is characteristic of North American blastomycosis and related infectious diseases.

Differential Diagnosis: The presence of unexplained pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia should prompt a search for associated tumors, such as granular cell tumor. True SCCs accompanied by pseudoepitheliomatous change can easily be missed, especially in a superficial shave biopsy. Careful search may reveal narrow cords of atypical keratinocytes, sometimes arising at the angle of intersection of proliferative epidermis and acanthotic follicular epithelium. Verrucous carcinoma can be particularly difficult to distinguish from pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, but the former can be suspected when the lesion is exophytic as well as endophytic; contains deeply extending crypts filled with neutrophils and keratinous debris; and shows bulbous, “pushing” deep margins.