Melanocytic Tumors

More than most categories of cutaneous disease, the melanocytic tumors are especially dominated by one condition: melanoma. Virtually every melanocytic lesion is accompanied by the specter of melanoma. Although in some cases this possibility is remote, in others it is a more immediate concern. In short, melanoma is the diagnosis against which almost all other melanocytic lesions are judged. This chapter considers the constellation of melanocytic lesions; the histopathologic features that make them unique; and those microscopic changes that overlap, mimic, or can be mimicked by the variants of melanoma.

Non-neoplastic Hyperpigmented Lesions

Clinical Features: Ephelides (singular ephelis, although it is sometimes given as ephelid) is a small hyperpigmented spot typically measuring less than 4 mm in diameter. The epidermal surface is otherwise normal, essentially the same as adjacent uninvolved skin. The spots tend to be light tan in color but may darken with sun exposure. Typically, ephelides are seen in individuals with skin types that burn readily but tan poorly with sun exposure, such as those with Celtic background.1

Microscopic Findings: Biopsy changes are subtle, consisting of a circumscribed area of basilar hyperpigmentation that differs only slightly from the pigmentation of adjacent, uninvolved skin. No discernible melanocytic proliferation is seen; down-growths of rete ridges are not observed; and the melanocytes lack significant morphologic abnormalities, showing only increased amounts of coarse pigment granules. In fact, the numbers of melanocytes per unit area are the same or slightly decreased compared with those in the adjacent epidermis.2

Differential Diagnosis: Lentigines frequently (but not invariably) show slightly exaggerated down-growth of rete ridges and a greater density of basilar pigmentation. In contrast to ephelides, there are increased numbers of melanocytes per unit area in lentigines, which can be nicely demonstrated with techniques such as Melan-A staining. Distinction between the naturally brown melanin pigment and positive immunohistochemical staining can be achieved by using a counterstain for melanin, such as azure B, or by using a chromogen other than the brown-staining diaminobenzidine (e.g., aminoethyl carbazole—a red stain). Café-au-lait macules may have similar degrees of pigmentation but are much larger than ephelides. Giant melanosomes can be found in these macules—a feature not generally described in ephelides.

Mucosal Melanosis

Clinical Features: This condition encompasses an array of variably named lesions that share similar, if not identical, clinical and histopathologic features. These are irregularly shaped, well-demarcated pigmented macules on mucosal surfaces, including the lip (labial melanotic macule), portions of the oral cavity (oral melanosis), and genitalia (penile/vulvar melanosis or genital lentiginosis).3,4 These asymptomatic lesions can cause significant concern for mucosal melanoma in patients and clinicians.

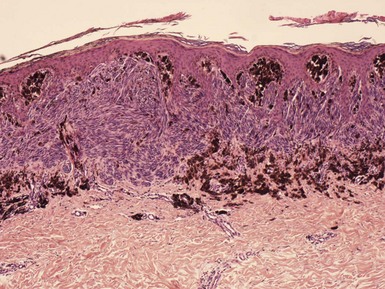

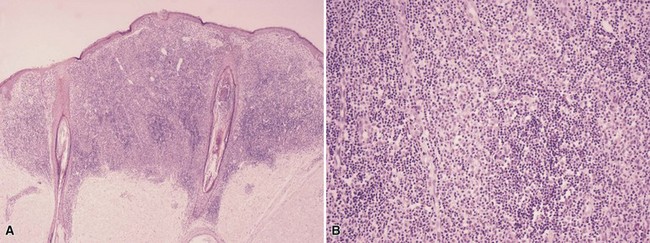

Microscopic Findings: All of these forms of mucosal melanosis show prominent basilar hyperpigmentation with accentuation at the tips of rete ridges (Fig. 28-1A and B). Melanophages are usually found in the papillary dermis/lamina propria of oral lesions and virtually always in genital lesions. The numbers of melanocytes are normal, and there is no nesting of these cells. Significant cytologic atypia is not observed, and no mitoses are identified.3–5

Differential Diagnosis: Many of these lesions display evenly distributed basilar hypermelanosis across a broad front of epidermis, with well-demarcated lateral borders; confluence of junctional melanocytes as seen in lentiginous melanoma is not observed. Exaggerated down-growths of rete ridges as seen in lentigines and (in a more extreme manner) reticulated pigment anomalies are not truly features of these lesions, and based on this difference, some authors prefer to make a distinction between mucosal lentiginosis and mucosal melanosis. Melanoacanthoma is probably a phenomenon rather than a distinct clinicopathologic entity; in contrast to melanotic macules, dendritic melanocytes are found scattered within suprabasilar epidermis, with poor pigment transfer to adjacent keratinocytes.6 Forms of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation can resemble melanotic macules with prominent melanophages in the papillary dermis or lamina propria. However, the discrete nature and sharp demarcation of melanotic macules and lack of significant inflammation argues against hyperpigmentation arising in an inflammatory dermatosis.

Café-au-Lait Macules and Nevus Spilus

Clinical Features: Café-au-lait macules are homogeneously colored, light to dark brown macules or patches. They can arise anywhere on the body surface except for mucous membranes and are actually quite common, with solitary lesions being found in 10% to 20% of the population. Café-au-lait macules can serve as markers for various syndromes, particularly neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2, but also the McCune-Albright syndrome and Watson syndrome.7 Nevus spilus, or speckled lentiginous nevus, features a grouping of small, pigmented macules and papules on a light tan macule. This is a not uncommon incidental finding but can be associated with several types of phakomatosis (defined as a hereditary syndromes with involvement of eye, skin, and brain). The macular form of nevus spilus features hyperpigmented macules that are evenly distributed on a light tan background; it is associated with phakomatosis spilorosea, a combination of nevus spilus and a telangiectatic nevus with a distinctive pale pink, salmon color.8 The papular form of nevus spilus shows uneven distribution of the papules; it is associated with phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica, a combination of nevus spilus and a nonepidermolytic epidermal nevus.9 Spitz nevi may develop in either type of speckled lentiginous nevus, but melanoma has developed much more frequently in the macular form of nevus spilus.10 Blue nevi (including cellular blue nevi) have also occurred in nevus spilus.

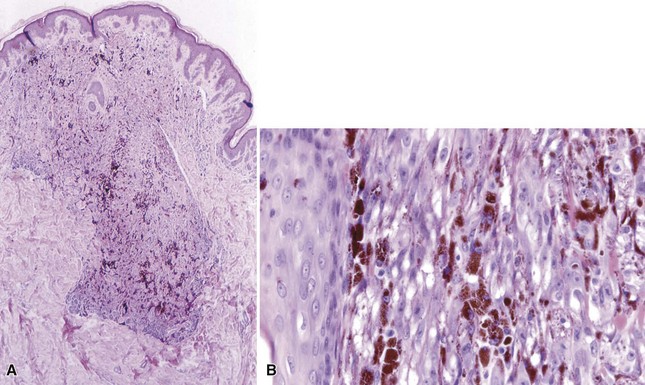

Microscopic Findings: In café-au-lait macules, there is an increase in melanin in melanocytes and basilar keratinocytes. Therefore, the findings are similar to those in ephelides. However, increased numbers of melanocytes per square millimeter have been found when the dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) reaction has been applied to skin sections.11,12 Giant melanosomes are sometimes observed in these lesions and are not restricted to those associated with neurofibromatosis. These can be seen on routine examination as rounded, evenly pigmented bodies that are larger than normal melanin granules (ranging in size up to 5 µ in diameter) in basal keratinocytes as well as melanocytes (Fig. 28-2A and B).13 The background tan macule of nevus spilus shows mild junctional melanocytic hyperplasia and, sometimes, exaggerated down-growth of pigmented rete ridges—a feature of lentigo.14–16 The speckles within nevus spilus usually show features of junctional or compound nevi.16 In the macular form the speckles consist of junctional lentiginous nevi, whereas in the papular form these lesions are compound or intradermal nevi.10 As noted, Spitz nevi can be found in either the macular or papular variants. Blue nevi, including those with changes of cellular blue nevi, can also be found in the context of a nevus spilus.17

Differential Diagnosis: Café-au-lait macules can resemble ephelides, lentigo simplex, or solar lentigo but can be differentiated on clinical grounds. In contrast to ephelides, increased numbers of melanocytes per unit area of epidermis can be demonstrated. Although giant melanosomes are features of some café-au-lait macules, they are not always observed in these lesions, even in those associated with neurofibromatosis.18 At the same time, they are not uncommonly found in otherwise conventional lentigines or junctional lentiginous nevi; in fact, on a percentage basis, most of the lesions with giant melanosomes fall within this category. The background tan macules of nevus spilus most often have the microscopic features of lentigo. Other hyperpigmented lesions, such as melasma, could be confused with café-au-lait macules or the background macules of nevus spilus, but they are quite different clinically; the intensity and depth of dermal pigment associated with melasma is the most significant consideration, particularly from a therapeutic standpoint.

Becker Nevus

Clinical Features: Becker nevi are typically unilateral, large (2 to 15 cm in diameter), hyperpigmented patches and plaques located often on the trunk, although they may be found virtually anywhere on the body surface.19 They are usually noted in the second or third decade of life and are more common in males. Hypertrichosis may be noted within the lesion, and although well demarcated, the borders are often irregular. Becker nevi have been associated with a variety of developmental anomalies.20,21 An association with smooth muscle hamartoma has been described in some cases.22,23

Microscopic Findings: The epidermis often shows hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis. Elongation of the rete ridges is frequently present, and in many cases the ridges are tapered rather than flattened at their tips (Fig. 28-3). There is increased melanin in basal keratinocytes, and the numbers of melanocytes along the basilar layer are normal to slightly increased. Pigment incontinence with ingestion by macrophages is frequently observed. Increased numbers of hair follicles and sebaceous glands may be noted, particularly when compared to normal for the particular anatomic location; however, horizontal sections may be necessary to appreciate the degree of hypertrichosis noted clinically. In examples associated with smooth muscle hamartoma, irregularly distributed, well-differentiated smooth muscle bundles are observed within the dermis.23 If necessary, these can be well demonstrated with trichrome stain or with immunohistochemical methods (actin, desmin).

Differential Diagnosis: The slight papillomatosis and elongation of rete ridges could be confused with epidermal nevus, although usually these changes are milder than seen in the majority of epidermal nevi. Increased numbers or prominence of follicles or sebaceous glands (compared to normal for the anatomic site) may also serve as a clue to Becker nevus. When a smooth muscle hamartoma is present, it may be the predominating feature, and then there are several considerations. First, careful evaluation of the epidermis should be carried out to determine the possible coexistence of Becker nevus. Second, piloleiomyoma should be ruled out. However, the latter usually features a large aggregate of smooth muscle, whereas smooth muscle hamartomas feature scattered smooth muscle bundles within the dermis.

Benign Melanocytic Tumors

Lentigo Simplex and Solar Lentigo

Clinical Features: Lentigo simplex is a brown to black, well-defined, typically uniformly pigmented macule. It often arises in children and young adults with no relationship to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, thereby distinguishing it from solar lentigo. Lentigo simplex lesions can occur anywhere on the body surface. In contrast to ephelides, these lesions do not darken with sun exposure.24 The absence of BRAF, FGFR3, and PIK3CA mutations is a characteristic of lentigo simplex that distinguishes it from solar lentigo as well as melanocytic nevus.25

Solar lentigo is a UV-induced, tan- to dark-brown macule exclusively found on sun-exposed surfaces, especially the face, dorsal hands and arms, and shoulders.26 Often oval-shaped and homogeneous, the macules can also be irregularly defined and mottled in appearance. Solar lentigines occur in middle aged to elderly patients, most commonly in Caucasians. Their incidence increases with age. A clinical variant termed “ink spot” lentigo is characterized by its black color and irregular outline, mimicking a spot of ink on the skin.27

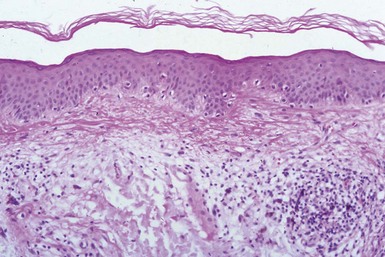

Microscopic Findings: In lentigo simplex, there is an increase in the number of single basilar melanocytes, leading to basilar keratinocyte hyperpigmentation. Mild elongation of rete ridges is noted (Fig. 28-4). Solar lentigo is a benign condition with both keratinocyte and melanocyte proliferative changes. It shows acanthosis with elongation of the rete ridges and characteristic club-shaped or bud-like extensions. There are increased basal layer pigmentation, accentuated along the sides and tips of rete ridges, and an increased number of non-nested melanocytes (Fig. 28-5).28,29 Facial solar lentigines frequently lack rete ridge hyperplasia.28 Solar elastosis can be identified in the underlying dermis.

Differential Diagnosis: Lentigo simplex is distinguished from junctional nevus by the presence of junctional melanocytic nests in the latter. Frequently, lesions are encountered that have predominant features of lentigo but a rare small nest can also be identified. Some authors have preferred to designate the latter lesion “jentigo.”30 The freckle, or ephelis, shows slight basilar hypermelanosis compared to adjacent uninvolved epidermis, but lacks down-growth of rete ridges, and the numbers of melanocytes per unit area are normal or slightly decreased.

Solar lentigo certainly resembles lentigo simplex in some respects, but acanthosis and/or down-growth of rete ridges is often more extensive than in the latter lesion, and changes of solar elastosis are observable in the underlying dermis. The proliferative rete ridges of solar lentigo are sometimes quite pronounced, and small horn cysts, resembling the changes of pigmented, reticulated seborrheic keratosis, can also be identified. As mentioned earlier, a subset of solar lentigines shows loss of the rete ridge pattern; this change is particularly but not exclusively seen in the head and neck region. Some of these lesions also feature enlargement of both keratinocyte nuclei and cytoplasm; such lesions are sometimes called large-cell acanthoma (see discussion in Chapter 18).

Melanocytic Nevi and Variants

Clinical Features: Acquired melanocytic nevi are composed of modified melanocytes (nevomelanocytes). These extremely common skin lesions usually appear during childhood or young adulthood. They are typically well-circumscribed, symmetrical, round to ovoid lesions, generally measuring between 2 and 6 mm in diameter. They are believed to begin as junctional nevi, confined to the epidermis. Later, melanocytes migrate into the dermis, forming compound nevi. Ultimately, all of the cells migrate into the dermis, forming intradermal nevi. The junctional nevus is a brown-black, macular lesion, whereas compound and intradermal nevi display varying degrees of elevation and generally range from brown to flesh-colored. Melanocytic nevi may have papillomatous or verrucous features and can be accompanied by coarse or dark hair. There is evidence that numerous nevi on skin represent a marker for increased risk of cutaneous melanoma. Both nevi and melanoma appear to be induced by intermittent exposure to sunlight.

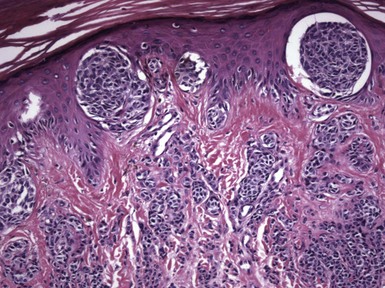

Microscopic Findings: Junctional nevi, which in pure form are relatively uncommon, feature discrete nests of melanocytes along the dermal-epidermal junction without evidence of confluence and with good cohesion among melanocytes within the nests (Fig. 28-6A). In compound nevi, nests of melanocytes are present both at the dermal-epidermal junction and within the dermis (see Fig. 28-6B), whereas in intradermal nevi, nests, cords, or other groupings of melanocytes are located exclusively within the dermis (see Fig. 28-6C). Many junctional and compound nevi also have changes associated with lentigo: exaggerated down-growth of hyperpigmented rete ridges. Intradermal nevi are sometimes classified into two groups: Unna nevi, in which nevomelanocytes are confined to the papillary and perifollicular dermis, and Miescher nevi, in which nevomelanocytes that diffusely infiltrate adventitial and reticular dermis assume a wedge-shaped configuration.31 Compound and intradermal nevi often show an arrangement of three types of nevus cells: larger, pigmented, type A nevus cells near the junctional zone and in the superficial dermis; a deeper focus of smaller, rounded, nonpigmented type B nevus cells; and spindled type C nevus cells at the base of the lesion. This arrangement, in which superficial nests of larger cells evolve to smaller, more singly dispersed cells in the deeper portion of the specimen, is referred to as maturation descent, a characteristic feature of nevi that is lost or poorly demonstrated in melanomas. Furthermore, nevus cells are separated from one another by a delicate network of reticulin (type III collagen), whereas melanomas tend to show organization of cells as sheets or large aggregates with no intervening reticulin between the cells. Expansile nests or tumor nodules are not observed in nevi, with the exception of some congenital nevi (see later discussion).32 Mitotic figures are rare in conventional melanocytic nevi but can be observed from time to time.33 They were found in 4% of one series of 157 nevi.34 The role of trauma in the induction of mitotic activity in nevus cells is questionable, and in one study of 92 traumatized nevi, only one mitotic figure was identified.35 Type C nevus cells may be arranged to form neuroid structures resembling Wagner-Meissner bodies; this change is sometimes termed neurotization. In some examples of intradermal nevi, type C spindle cells may predominate, creating a resemblance to neurofibroma. It is possible that many isolated “neurofibromas” identified in middle-aged to older adults may actually represent completely neurotized nevi. In fact, type C nevus cells show immunohistochemical as well as morphologic evidence of schwannian differentiation.36 However, lentiginous melanocytic nevi can be identified overlying neurofibromas in type 1 neurofibromatosis.37 Other cytologic features seen in banal melanocytic nevi include sporadic cells with enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei or intranuclear vacuolization, considered a variant of “ancient” change that can be seen in a variety of tumors in addition to melanocytic nevi. Some compound and intradermal nevi can feature associated epithelial or mesenchymal abnormalities. Thus, nevi can have an associated epidermal cyst, and sometimes rupture of the cyst produces changes that prompt a biopsy of the lesion. Melanocytic nevi sometimes have prominent vessels. However, this should not be confused with pseudovascular changes within a nevus; this results from clefts that form between columns of nevus cells. Immunostaining of such cases demonstrates that the clefts are lined by melanocytes and not endothelial cells.38 Fat cells are commonly seen in melanocytic nevi, although it was shown in one study that these cells do not contain S-100 protein.39,40 Some nevi show “balloon cells,” singly or in aggregates, and lesions composed predominantly of “balloon cells” also exist. The cytoplasm of these cells is finely vacuolated and may compress the nuclei, giving them a scalloped configuration (Fig. 28-7A and B). The change is said to result from a defect in the process of melanogenesis.

Figure 28-6 Common types of melanocytic nevi. A, Junctional nevus. B, Compound nevus. C, Intradermal nevus.

Figure 28-7 “Balloon cell” nevus. This lesion was composed predominantly of “balloon cells.” A, Quick low-power inspection can raise the possibility of other clear cell tumors. B, On higher magnification, it can be seen that the cytoplasm is finely vacuolated and that some of the nuclei have scalloped borders.

Differential Diagnosis: An old saying is that nevus cells (nevomelanocytes) are best recognized by the company they keep; they tend to be arranged in nests, cords, and aggregates of various kinds. When nevus cells are arranged in single units within the dermis, especially when intermingled with lymphocytes or macrophages, they can be quite difficult to identify without special stains, and in some instances, on low-power examination, small-cell nevi can be difficult to distinguish from inflammatory infiltrates. Even then, these cells often tend to aggregate in pairs or small clusters. Their readily recognizable cytoplasm and somewhat larger nuclei allow distinction from lymphocytes in most instances. Type C nevus cells closely resemble those of neurofibroma, and when all cells in a lesion have this appearance, distinction from neurofibroma may be impossible. This usually has little clinical import, unless determination of a form of neurofibromatosis hinges on the distinction. Staining for factor XIIIa or myelin basic protein can be helpful, because these can be demonstrated in neurofibroma but not in neurotized nevi.41 In a case of pigmented plexiform neurofibroma, polygonal pigmented melanocytes in the superficial dermis and within neurofibromatous tissue stained for Melan-A and PNL2, whereas glial fibrillary acidic protein and leu7 (CD57) stained only the slender spindled cells in plexiform foci.42 Nevi with pseudovascular change should be distinguished from hemangiomas, although a more common problem is the distinction of coexisting nevus and hemangioma from pseudovascular nevus. Ordinarily, examination of pseudovascular nevi shows that the cells lining spaces within the dermis are identical to the more obvious nevus cell elements elsewhere in the specimen, but if necessary, differential staining can be carried out, for example using S-100 or Melan-A and endothelial markers such as CD31. Distinction between melanocytic nevi of the common type and melanoma is usually not difficult, and some of the criteria have already been pointed out: maturation descent is demonstrable in nevi but not in melanomas; nevus cells are separated from one another by delicate reticulin, whereas melanomas are arranged in sheets or nodules with no intervening reticulin; expansile nests or tumor nodules are features of melanoma but not of conventional nevi; and mitotic figures are rare in ordinary nevi but common in melanoma. A more challenging problem is the recognition of nevoid melanoma, a subtype of melanoma that can have a close morphologic resemblance to nevus, particularly at low magnification. That distinction is explored in more detail in a later section.

Halo Nevus

Clinical Features: The halo nevus is clinically described as a centrally located pigmented melanocytic nevus surrounded by a depigmented zone.43 These lesions undergo four stages of evolution: (1) appearance of the halo; (2) loss of pigment within the centrally located nevus; (3) disappearance of the nevus; and (4) disappearance of the halo, with return of the patient’s normal pigment. These are solitary or multiple lesions, often occurring on the trunk of young adults. Halo nevi are associated with vitiligo in some cases and can also occur in patients with melanoma.44 Halo nevi represent an immunologic response, with both cell-mediated and humoral elements, to antigens expressed on nevomelanocytes.45 Halo nevi can also develop in the setting of melanoma, including occult melanoma.46

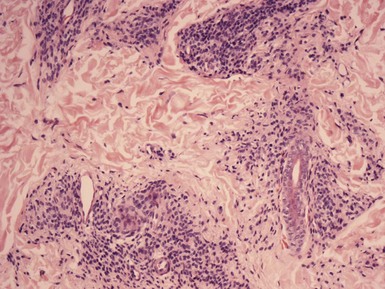

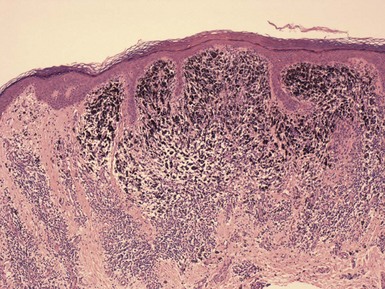

Microscopic Findings: Fully evolved halo nevi are characterized by a dense, diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding and infiltrating melanocytes at the junctional zone and/or in the dermis. The infiltrate is typically well demarcated both laterally and at its base. It is often so dense that it largely obscures the melanocytes (Fig. 28-8A), but clusters of melanocytes can often be identified in the midst of the field of lymphocytes (see Fig. 28-8B), and they can also be identified with special stains such as S-100 and Melan-A. The latter is preferred, in that the infiltrate may contain prominent S-100–positive Langerhans cells. The number of nevus cells depends on the stage at which the biopsy was taken, and they may appear swollen, variable in size, and demonstrate mild to moderate and, sometimes, severe cytologic atypia.47 Occasional mitotic figures can be found. If the specimen is of sufficient size, it may be possible to demonstrate an absence of junctional melanocytes adjacent to the lesion with stains such as Melan-A. However, it should be noted that there is often discordance between the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate and the clinical appearance of a halo. Thus, there may be microscopic inflammatory change without a clinical halo (so-called “halo nevus without halo”),48 or a clinical halo without inflammation.49 The former is the more frequent finding.

Figure 28-8 Halo nevus. A, There is a dense inflammatory infiltrate, sharply demarcated laterally and at its base, that partly obscures dermal melanocytes. B, On higher magnification, clusters of somewhat larger, paler cells can be identified; these are nevus cells, and their melanocytic origin can be confirmed with special staining.

Differential Diagnosis: White rings have been found around a variety of lesions, including dermatofibroma50 and basal cell carcinoma,51 and “halo dermatitis” or “eczema” has been noted to surround a variety of lesions, including seborrheic keratoses, keloids, lentigines, arthropod bites, and basal and squamous cell carcinomas as well as melanocytic nevi. However, this “halo dermatitis” is clinically distinct from a white halo and more closely resembles the Meyerson phenomenon (see subsequent discussion). It is not clear that the white rings around such lesions as dermatofibroma and basal cell carcinoma represent the same mechanism as associated with a true halo nevus—that is, a temporary loss of junctional melanocytes. One possible explanation could be vasoconstriction due to the application of topical corticosteroids. Another could be a phenomenon related to Woronoff ring, a white ring around psoriatic plaques that frequently follows coal tar and UV therapy. That ring has been shown to result from a local inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis not found in normal skin.52 Halo nevi must also be distinguished from melanoma, particularly with early regressive change. This can be a difficult task, but diagnosis should depend on a careful assessment of the melanocytic lesion that underlies the inflammation, with attention being paid to features such as degree of symmetry, junctional melanocytic confluence, presence or absence of pagetoid intraepidermal change, and cytologic atypia, with particular reference to maturation with descent (see “Melanoma—Differential Diagnosis”). In contrast to halo nevus, regression in melanoma is generally accompanied by coarse fibrosis. The reasons for this difference are not entirely clear, but halo nevi have been found to have higher tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression than melanoma; this cytokine is known to have antifibrotic properties.53

Meyerson Nevus

Clinical Features: In 1971, Meyerson reported two cases of what he described as “a peculiar papulosquamous eruption” involving pigmented nevi.54 Since that time, there have been a number of reports of melanocytic nevi surrounded by a rim of spongiotic (eczematous) dermatitis.55,56 The condition has been observed frequently in young adults but has also been described in children.57 Although generally associated with acquired melanocytic nevi, it has been found to occur in congenital nevi as well.57,58 Lesions are prone to develop over the trunk and proximal upper extremities. The eczematous changes eventually resolve, either spontaneously or with topical corticosteroid therapy. Unlike halo nevi, the nevi involved by eczematous changes do not appear to involute.59 However, transition to a halo nevus has been reported,60 as has coexistence with halo nevi.61 The Meyerson phenomenon has been associated with dysplastic nevi62,63 and melanoma lesions.59,62,64 In one case, a patient developed multiple Meyerson nevi, one of which involved what proved to be melanoma; following excision of the melanoma, the Meyerson phenomenon subsided.59

Microscopic Findings: In the typical case, a junctional or compound nevus is associated with spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and varying numbers of eosinophils (Fig. 28-9).65 The infiltrate is composed mainly of CD3+ lymphocytes, the majority of which are CD4+, although there are also CD8+ cells.65,66 Limited upward epidermal migration of melanocytes is observed, even in otherwise nondysplastic nevi.62 It has been suggested that interaction of CD4+-lymphocytes with increased epidermal expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) might explain some of the changes.66

Differential Diagnosis: In the absence of a clinical history, Meyerson nevus is difficult to distinguish from a nevus that has simply been secondarily eczematized or is present in the midst of an eczematous dermatitis that has developed for other reasons (e.g., atopic or allergic contact dermatitis). Eczematous changes have also been described within or around other types of lesions, including molluscum contagiosum, dermatofibroma, seborrheic keratosis, nevus flammeus, and smooth muscle hamartoma.67–70 However, these should be distinguishable from Meyerson nevi either clinically or microscopically.

“Special Site” Nevi

Clinical Features: Over the years, it has been recognized that melanocytic nevi from certain anatomic sites share particular histopathologic features, some of which may be regarded as “atypical” and raise concerns for malignancy. This has led to the alternate designation “nevi with site-related atypia.” Nevertheless, these nevi appear to be biologically bland and do not signify an increased risk of melanoma. The reasons for the distinctive features of special site nevi are not entirely clear and cannot be explained simply by anatomy or mechanical factors, because most nevi that occur in these sites have conventional characteristics indistinguishable from those arising anywhere on the cutaneous surface.71

Few unique clinical characteristics are associated with these nevi. Acral lesions often show irregular borders with uniform pigmentation and have a distinctive dermoscopic pattern in which pigment is distributed along the sulci of ridges constituting the dermatoglyphics of the palms and soles.72 Atypical genital nevi in women are more apt to occur in mucosal sites as opposed to traditional, architecturally disordered nevi, which mainly occur in hair-bearing areas.73 A subset of nevi along the milk line have polypoid features.74 The following microscopic descriptions emphasize the key features in each of these special site nevi.

Microscopic Findings: The microscopic characteristics of “special site” nevi have been well described in a highly useful review by Hosler and colleagues.71 Acral nevi often show significant upward epidermal migration of melanocytes (Fig. 28-10), a finding that has earned the acronym MANIAC, or melanocytic acral nevus with intraepidermal ascent of cells.75 Other features include bridging of rete ridges, fibroplasia, significant inflammation, pigment in the stratum corneum, and nested melanocytes in the dermis with “skip areas” and syringotropism.71,76

Genital (particularly, vulvar) nevi can be large, nodular lesions with variability of size and shapes of nests along the rete ridges (not always at the tips) and in the dermis, loss of cohesion of melanocytes within nests, sometimes severe atypia on the basis of cellular enlargement but with a preserved nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and rare mitoses.71,73 Upward epidermal migration of melanocytes and adnexal involvement are sometimes observed,77 and the stromal changes tend to be nonspecific,78 although diffuse fibrosis can sometimes be seen, especially in polypoid lesions (Fig. 28-11A-C).71 Symmetry and preservation of maturation descent are features that further support the diagnosis of nevus in these lesions.

Figure 28-11 Genital nevus. This example shows several characteristic features of this type of nevus. A, There is loss of cohesion within melanocytic nests. B, Adnexal involvement is frequently observed. C, A rare mitosis is identified in the dermis.

Nevi from the breast have similar features in men and women, and the characteristic findings tend to be more prevalent in young adults.71 Findings include a garland-like arrangement of junctional nests, enlarged but uniform melanocytes with preservation of normal nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios and generous amounts of clear to dusty cytoplasm, and maturation with descent in the form of more bland-appearing cells arranged singly and in smaller aggregates.71 Rongioletti and associates found suprabasilar melanocytes, cytologic atypia, and papillary dermal fibroplasia.79

Rongioletti and associates also performed a study of flexural nevi. They found that about 50% of patients displayed confluence of large nests, varying in size, shape, and location along the junctional zone, as well as loss of cohesion of melanocytes within nests. These changes are similar to the ones in genital nevi.80

Nevi of the scalp often display changes associated with other “special site” nevi,81 including large nests of different sizes, distributed at varying sites along the junctional zone (not always at tips of rete ridges), loss of cohesion within nests, adnexal involvement, suprabasilar melanocytes, and inconspicuous stromal changes. Cytologic atypia is often observed.71

Lesions of the ears are often considered “special site” nevi and share some features with such nevi in other anatomic sites. Lazova and coworkers described several particularly common findings among these lesions: “shouldering” of the junctional component, poor lateral circumscription, elongated rete ridges with bridging, dermal lymphocytic infiltration, and cytologic atypia.82 Saad and colleagues also found poor lateral circumscription and cytologic atypia in their cases, and in addition noted suprabasilar melanocytes (Fig. 28-12).83

Figure 28-12 Nevus from the ear. These lesions show poor lateral circumscription, occasional suprabasilar melanocytes, and a degree of cytologic atypia.

Conjunctival nevi may create diagnostic problems because of the common highly cellular dermal components of these lesions and recognizable cytologic atypia. Clues to the location of these lesions include goblet cells and epithelial-related cystic and pseudoglandular spaces intermingled with melanocytes (Fig. 28-13). Symmetry, circumscription, and pigment stratification with descent tend to support a benign interpretation.

Differential Diagnosis: When confronted with diagnosing a lesion from a “special site,” one has the dual task of not overinterpreting the findings as melanoma while not underinterpreting a lesion as benign in view of the potentially dire consequences of missing a melanoma. In particular, this is the case with lesions of the genitalia or the ears; in these locations, melanomas can be particularly aggressive. Finding some of the common features among “special site” nevi can be reassuring about the benign nature of a lesion, but several of these—particularly, upward epidermal migration of cells, loss of cohesion within nests, and cytologic atypia—can be troubling. Findings that should be present in nevi are overall symmetry and circumscription, a lack of atypia (at least, a lack of cells with abnormal nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios), and an absence of atypical or deep mitoses. Any upward epidermal migration of melanocytes should consist of cells without atypia, limited to the central portion of the lesion. Caution also should be exercised when the submitted lesion represents only a partial biopsy, and lentiginous changes extend to the specimen margin. This raises the possibility that there might be features of melanoma extending beyond the site of the tissue sample; re-excision should be recommended in such circumstances.71

Deep Penetrating Nevus and Plexiform Spindle Cell Nevus

Clinical Features: In 1989, Seab and Graham reported a group of lesions that they termed deep penetrating nevus (DPN). These typically present as well-circumscribed, hyperpigmented nodules of the face, upper trunk, or proximal extremities in young persons (in the range of 10 to 30 years). Their microscopic findings can create concern because of the depth of dermal involvement and frequent lack of maturation with descent, leading to an erroneous diagnosis of melanoma. Several years later, Barnhill and associates from the Massachusetts General Hospital reported a group of cases that they described as plexiform spindle cell nevus (PSCN).84 These lesions are also described as bluish or black and occur most commonly on the shoulders or back of young adults—characteristics that are similar to those described for DPN. These lesions have microscopic changes that can create problems with interpretation, and although recurrences or metastases typically do not occur, rare examples of lymph node metastasis have been reported.85

Microscopic Findings: DPN are generally well circumscribed. They may show junctional nesting. The dermal component of the lesion displays a wedge-shaped configuration, with the “point” of the wedge (which may actually be rounded) extending into the deep dermis or subcutis.86 Pigmented spindled cells are more loosely organized superficially and are grouped into nests or fascicles in the deep dermis, often distributed along neurovascular structures or adnexal epithelia.87 Melanophages frequently accompany the lesion. Maturation with descent is often not convincingly demonstrated, and cytologic atypia can be observed in the form of enlarged nuclei or prominent nucleoli (Fig. 28-14A and B). Mitotic figures can occasionally be found88; they are usually not atypical or found in deeper portions of the lesion. The findings in PSCN are similar, except that the predominant feature is the tracking along neurovascular plexuses and adnexal structures in a plexiform configuration (Fig. 28-15A and B).84 The general trend is to regard these as microscopic variants of the same lesion.89

Figure 28-14 Deep penetrating nevus. A, The dermal component displays a wedge-shaped configuration, with extension deep into the dermis. B, Deeper dermal cells adjacent to a follicular unit. Note that maturation descent is not convincingly demonstrated, and cytologic atypia is observed in this portion of the lesion.

Figure 28-15 Plexiform spindle cell nevus and “clonal” nevus. A, The lesion shows deep extension but has a distinctly plexiform configuration. B, Cells proliferate along neurovascular plexuses. C, An example of a combined, or “clonal” nevus, with superficial features of conventional compound nevus and a deep component resembling deep penetrating or plexiform spindle cell nevus.

An association of these changes with conventional melanocytic nevus is common.89 In addition, it has been recognized for some time that aggregates of pigmented, epithelioid to fusiform cells resembling those of DPN or PSCN can be confined to the superficial dermis in association with conventional compound or congenital-type nevi. Such lesions have been variously termed “clonal” or “combined” melanocytic nevi or “nevus with focal atypical epithelioid component” (see Fig. 28-15C).90 These lesions also have a favorable outcome and may well represent variant forms of DPN or PSCN.

Differential Diagnosis: DPN and PSCN share some microscopic features with Spitz nevus and cellular blue nevus. Although they can generally be distinguished from the latter nevi by their typical clinical presentation and wedge-shaped or plexiform microscopic arrangements, they may be within the same family of disorders because of overlapping cytologic characteristics. Differentiation from melanoma is the most important consideration. Features arguing against melanoma include smaller size, high degree of symmetry, sharp circumscription, generally low-grade cytologic atypia, and low-to-absent mitotic activity.

Persistent/Recurrent Melanocytic Nevus

Clinical Features: Persistent/recurrent melanocytic nevi occur after an incomplete sampling of a nevus, especially following a shave biopsy.91 Clinically, these lesions often develop within 6 months of the surgical procedure and show pigmentation arising within the scar; this pigment is macular and often irregularly distributed. In fact, the changes may be such that they violate the usual “ABCD” role of dermoscopic examination: namely, asymmetry, irregularity of borders, color variation, and differential dermoscopic structures (pigment streaks, dots and globules), thereby creating concerns for melanoma.92 The back is a common site, and the phenomenon is more frequently observed in young women.91,93 Despite the unusual clinical features and the microscopic difficulties created by this phenomenon, recurrent nevi are benign lesions amenable to complete excision.93

Microscopic Findings: Typically, the epidermis is effaced, and there is junctional melanocytic proliferation, in a singly dispersed or lentiginous configuration, confined to the region overlying a dermal scar. Residual intradermal nevomelanocytes can sometimes be identified deep to the scar (Fig. 28-16A). It is believed that the junctional melanocytes result from proliferation of melanocytes left behind within the epidermis or adnexal epithelia following the previous biopsy procedure (see Fig. 28-16B).94,95 King and coworkers described four different microscopic images associated with persistent/recurrent nevi, all associated with dermal scar: junctional and compound melanocytic hyperplasia with effacement of rete ridges, and junctional and compound melanocytic hyperplasia associated with lentiginous down-growth of rete ridges.96 Pagetoid upward migration of melanocytes through the epidermis is sometimes noted.97 Melanocytes at the junction are variably pigmented and show mild to moderate cytologic atypia in terms of nuclear size and appearance of nucleoli. Although this is the “classic” image of persistent/recurrent nevus, recurrent blue nevi are known to extend beyond the scarred site,98,99 and recurrent Spitz nevi may display nodular or sclerotic (desmoplastic) features.100,101 Persistent/recurrent nevi with dermal components show maturation with descent and “stratification” of HMB-45 or tyrosinase staining (i.e., decreasing with depth in the dermis) and a low proliferative index using Ki-67 staining.102

Figure 28-16 Persistent/recurrent melanocytic nevus. A, There are rete ridge effacement, underlying dermal scar, and patchy chronic inflammation. Clusters of residual intradermal melanocytes can be seen on the right side of the figure. B, Junctional melanocytes may result, in part, from proliferation of remaining melanocytes from within adnexal epithelia.

Differential Diagnosis: The differential diagnosis includes atypical nevus with stromal fibroplasia, melanoma with regressive changes, and recurrent melanoma. A history of a recent surgical procedure at the site, confinement of the lesion to a zone overlying the dermal scar, and careful assessment of the cytologic features should lead to a correct diagnosis. However, caution should be advised, especially when assessing a possible recurrent blue nevus or Spitz nevus, because these do not always “obey the rules” (i.e., extension beyond the confines of the scar or nodular recurrences). Significant problems can also arise when attempting to distinguish recurrent nevus from recurrent melanoma.100 Confirmation of prior biopsy, evaluation of the initial biopsy specimen when possible, and assurance of complete removal of the recurrent lesion are therefore recommended.

Other Variants of Acquired Nevi

The ancient melanocytic nevus is often a dome-shaped lesion that features a population of cells with large pleomorphic nuclei and occasional mitoses, among other, smaller cells with an arrangement suggesting a conventional or congenital nevus. Lesions are often strictly intradermal, but a junctional component is sometimes present. The large cells resemble those of epithelioid Spitz nevus (see later discussion). Stromal degenerative changes are also identified, including hemorrhage, fibrosis, or mucin deposition. Despite the atypical features, these nevi show a low proliferative index with Ki-67 staining. Recurrences or metastases have not been reported.103–105

The neurotized nevus consists of type C spindled nevus cells, sometimes with organization into Wagner-Meissner–like bodies (Fig. 28-17A).106 Typically, these changes occur in the setting of an otherwise conventional melanocytic nevus or congenital nevus, but occasionally they may be the predominating feature and therefore difficult to distinguish from neurofibroma (see Fig. 28-17B). In such circumstances, immunohistochemical staining may be helpful. Factor XIIIa staining is strongly positive in neurofibromas but negative in neurotized nevi,107 and the neurotized areas of melanocytic nevi in one study were uniformly positive for Melan-A, in contrast to the negative staining for this marker in neurofibromas.108

Figure 28-17 Neurotized melanocytic nevus. A, This example shows structures resembling Wagner-Meissner bodies. B, Nevus cells can also take on an appearance closely resembling neurofibroma.

About 10% of benign melanocytic nevi show pseudovascular spaces, suggesting on initial inspection a vascular lesion.109 Erythrocytes can sometimes be found in these spaces. However, they appear to be lined by nevus cells and not by endothelium, and basement membrane material is not identified (Fig. 28-18). Immunohistochemical staining shows that the lining cells are in fact melanocytes and not endothelial cells.38,110 It is generally assumed that this change is an artifact resulting from the mechanical stress of the biopsy procedure and/or subsequent tissue processing.

Spindle and Epithelioid Cell Nevus (Spitz Nevus)

Clinical Features: The spindle and epithelioid cell nevus is a benign melanocytic lesion that is most commonly encountered in children and young adults. Its chief importance is its microscopic resemblance to melanoma. In fact, the 1948 paper by Sophie Spitz set apart a group of “melanomas of childhood” that shared certain histopathologic features but had a better than expected clinical outcome. An interesting facet of this study, and one that is pertinent to current diagnostic issues regarding Spitz nevi, is that one of the 13 reported cases had an aggressive clinical course resulting in death of a patient. Spitz postulated that a histopathologic feature allowing distinction of “juvenile melanoma” from true melanoma was the presence of giant cells in the former.111 Since that time, there have been refinements in the diagnostic criteria for this category of nevus,112 and molecular analysis holds the promise of more reliable distinction of Spitz nevus from melanoma.

As mentioned, Spitz nevus is most frequently a lesion encountered in young persons and may present as a congenital lesion,113 but examples in adults have also been reported with varying frequencies.112,114,115 There are reports of patients with Spitz nevi in the eighth decade of life,115 but certainly, caution must be advised in making this diagnosis in older adults. Most often, the Spitz nevus presents as a solitary, dome-shaped, flesh-colored to pink nodule, although pigmented variants definitely occur.116 Abrupt onset or rapid growth is frequently described. Groupings of these lesions, called agminate Spitz nevi, can also occur,117,118 sometimes following biopsy of a solitary Spitz nevus, and a rare disseminated variant has also been reported.119,120 These are typically benign lesions, but atypical variants occur that are biologically aggressive.121 In particular, a group of childhood lesions bearing resemblances to Spitz nevus involve regional lymph nodes but appear to have a favorable clinical course.122 Some examples of spitzoid tumors defy accurate categorization on histopathologic grounds alone, and widespread metastases have occasionally been reported in recurrent Spitz nevi.123 For these reasons, it has been recommended that all Spitz nevi be completely excised.124

An important variant of Spitz nevus is the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. The authors’ group refers to this lesion as sclerotic Spitz nevus, both to avoid confusion with desmoplastic melanoma and to diffuse the inevitable criticism that the term might be used as an evasion in difficult diagnostic circumstances. These lesions manifest as firm papules or nodules and frequently occur on the extremities.112,125 However, it is clear that not all desmoplastic nevi have cytologic characteristics of Spitz nevi.125,126 Desmoplastic Spitz nevi are reported most often in young adults, although children can also present with these lesions. The authors have encountered a number of them in patients in the fifth to sixth decades of life—significantly more often than is the case for conventional Spitz nevi. A subtype of desmoplastic Spitz nevus has prominent vasculature and has been designated angiomatoid Spitz nevus.127,128 These lesions have a favorable outcome following complete excision.

Microscopic Findings: There is a constellation of characteristic findings in Spitz nevi, but variations occur that can make accurate diagnosis particularly challenging. Typically, the lesions are sharply circumscribed and symmetrical, dome-shaped nodules. The epidermis is often acanthotic. The majority of Spitz nevi are compound, but junctional or intradermal types are also seen.129 The constituent cells are either spindled or epithelioid in type, and sometimes a mixture of both types is seen. It has been suggested that Spitz nevi in older adults are spindled rather than epithelioid in type. Junctional nests tend to be sharply demarcated from the adjacent epidermis, and spindled forms are oriented perpendicularly to the epidermis. Transepidermal elimination of nests does occur, resulting in the finding of nests in upper levels of the epidermis (Fig. 28-19A and B); pagetoid migration of single melanocytes through upper portions of the epidermis is not common but does occur in some examples.130,131 In Spitz nevi with a dermal component, maturation descent can often be demonstrated; this does not always include diminution of cell and nuclear size but may instead show mainly progression from nesting in the superficial dermis to single dispersion of cells in the deeper dermis (Fig. 28-20). Mitoses are uncommon but can be identified in these nevi. When present, they lack atypical characteristics and are usually not found in the lower third of the lesion. Accompanying stromal changes include papillary dermal edema and telangiectasia. Kamino bodies are pale pink globules that are found at the base of the epidermis in many Spitz nevi, often at the juncture of epidermis and melanocytic nests (see Fig. 28-19B).132 They are composed of basement membrane components and do not represent cellular apoptosis.133,134 Although Kamino bodies can be found in both melanomas and conventional melanocytic nevi,135 they tend to be more prominent in Spitz nevi; however, they may be missed if only a single section is examined.135 Desmoplastic Spitz nevi also have a dome-shaped configuration on low power, although they are sometimes plaquelike. The epidermis may be either acanthotic or effaced, and junctional involvement is often absent or limited in extent (Fig. 28-21A). Plump spindled to epithelioid cells tend to be organized into groupings, or nests, in the superficial dermis but are dispersed singly between thickened collagen bundles in the deeper dermis (see Fig. 28-21B). Nucleoli are variable in size but tend to be less conspicuous in the deeper dermis, and mitotic figures are uncommon. Small vessels are prominent in those cases classified as angiomatoid Spitz nevi.127,128 Lymphocytic inflammation is patchy and perivascular or diffuse and symmetrical; it tends to be inconspicuous in desmoplastic Spitz nevi.

Figure 28-19 Spitz nevus. A, This example is mainly junctional. Note irregular acanthosis, sharp demarcation of nests with a “raining down” configuration of some spindle cells within nests, and transepidermal elimination of nests. B, Transepidermal elimination of a melanocytic nest. Note the pale pink globule (Kamino body) at the juncture of the nest and the epidermis.

Figure 28-20 Spitz nevus. Maturation descent of dermal melanocytes is demonstrated by the transition from larger nests in the more superficial dermis (top) to smaller groups of cells and, sometimes, singly dispersed cells in the deeper dermis.

Figure 28-21 Desmoplastic Spitz nevus. A, There is an acanthotic epidermis with aggregates of spindled to epithelioid cells in a sclerotic matrix. Note absence of junctional involvement in this example. B, Nevus cells are singly dispersed within thickened collagen of the deeper dermis.

Problematic are those cases designated “atypical Spitz nevus” or “atypical Spitz tumor.”121,136 Histopathologic features of these lesions have varied, but some of the most important are ulceration, asymmetry and poor lateral circumscription, disordered intraepidermal melanocytic proliferation, expansile dermal proliferation of “back-to-back” cells, numerous and/or atypical mitoses, cell necrosis, and patchy dermal lymphocytic inflammation with a plasma cell component.

Immunohistochemistry has two major uses: to distinguish the occasional Spitz nevus that lacks obvious nesting from other lesions with epithelioid features (Spitz nevi are positive for S-100 and often for MART-1/Melan-A, in contrast to true epithelial or “histiocytic” lesions) and to aid in the distinction of Spitz nevi from melanomas with Spitz-like features. Spitz nevi show stratification of HMB-45 staining (reduced expression toward the lesional base)137 and reduced Ki-67 staining compared with melanoma.138 Positivity for p16 has also been found to distinguish desmoplastic Spitz nevi from desmoplastic melanomas, which are either negative or only weakly positive for this marker.139

Differential Diagnosis: As noted previously, nesting of cells (particularly at the dermal-epidermal junction) and, if present, pigment production, can allow the distinction of Spitz nevi from other lesions composed of epithelioid cells, including squamous cell carcinomas and “histiocytic” lesions (e.g., xanthogranuloma, reticulohistiocytoma, epithelioid cell histiocytoma). When the typical morphology of a melanocytic lesion is not present, differential immunostaining can be performed, using melanocytic markers (S-100, Melan-A) and other pertinent stains such as keratin, CD68, and factor XIIIa (realizing, however, that melanocytes can sometimes express CD68). However, the major diagnostic difficulty is clearly the distinction between some Spitz nevi, particularly atypical Spitz tumors, from melanoma. As mentioned, immunostaining can be of help here, in that, in contrast to melanomas, Spitz nevi show diminished HMB-45 staining toward the lesional base, decreased Ki-67 expression (indicating diminished proliferative capacity), and usually p16 positivity. It is well known, however, that some spitzoid tumors defy accurate morphologic classification. In this case, molecular analysis may prove helpful. For example, using comparative genomic hybridization, a subset of Spitz nevi shows gains of chromosome 11p, whereas melanomas are prone to feature chromosome 9 deletion.140

Pigmented Spindle Cell Nevus of Reed

Clinical Features: This nevus typically presents as a well-demarcated, darkly pigmented papule or plaque on the proximal lower extremity of young adult women.141,142 It is seen in other locations, such as the back, and does occur in men.143 Lesions are about 3 to 6 mm in diameter. It is thought by some that this nevus may represent a pigmented variant of Spitz nevus, but it has such a characteristic clinical and microscopic appearance that a specific diagnosis can usually be made. The rapid onset of these lesions raises concerns about melanoma, but they are benign lesions that respond well to complete excision.

Microscopic Findings: Pigmented spindle cell nevi are typically well demarcated and have a somewhat flat, platelike low-power configuration. The thickness of the epidermal component of the lesion is quite uniform. Melanocytic proliferation is mainly junctional (although there may be cell aggregates within the papillary dermis). This is composed of elongated spindled cells, arranged in nests that tend to lack sharp demarcation from the adjacent epidermis and often blend imperceptibly with bordering keratinocytes. Heavy pigmentation, of course, defines the entity. When melanocytes are present in the dermis, maturation descent can usually be demonstrated (Fig. 28-22). Cytologic atypia is minimal and nucleoli are usually inconspicuous, but mitoses can be identified among junctional melanocytes.142,143 Kamino bodies can be found. Although they were common in one study,144 they may not be seen in a given section and therefore additional levels are often necessary to find them. Atypical variants of pigmented spindle cell nevus have been described. These are characterized by such changes as lateral extension of junctional melanocytic hyperplasia, pagetoid spread to a midepidermal level, and/or bridged or horizontally confluent nests.145,146 Nevertheless, these lesions maintain overall symmetry and display limited cytologic atypia.

Differential Diagnosis: Pigmented spindle cell nevi are sometimes considered variants of Spitz nevi but differ from most Spitz nevi by the usual epidermocentric profile, abundance of pigment, and the slender appearance of the spindled cells. In contrast to pigmented spindle cell nevi, atypical (“dysplastic”) nevi are more prone to have lateral spread or “shouldering” of melanocytic proliferation along the junctional zone beyond the main body of the lesion, elongation of the rete ridges, stromal fibroplasia, mixed cell types (i.e., epithelioid or conventional-appearing melanocytes in addition to, or instead of, spindled forms), and horizontally bridged nests,147 although there may be a greater degree of overlap with atypical variants of pigmented spindle cell nevus. Pigmented spindle cell nevi differ from melanoma in that they are generally smaller, more symmetrical, show nests that are prone to be oriented perpendicularly to the epidermis, have limited pagetoid change (which, when present, tends to reach only to a midepidermal level), demonstrate maturation with descent, and (in contrast to some invasive melanomas) lack infiltration into the reticular dermis.

Blue Nevus and Variants

Clinical Features: The common blue nevus is a well-circumscribed, blue or blue-black macule or dome-shaped papule, usually less than 5 mm in diameter. It is most commonly located on acral surfaces, face, and scalp but can be found in virtually any location.148 The lesions are said to most commonly arise in childhood or adolescence, but biopsies of blue nevi are also frequently obtained from older adults. Multiple and agminated blue nevi have been described,149,150 and there is a rare association with nevus spilus.17,151

The cellular blue nevus is larger than the common blue nevus, generally 1 to 3 cm in diameter, and typically located on the buttocks, sacrococcygeal area, scalp,152 and distal extremities. These lesions can present at any age, although adults younger than 40 years of age are most commonly affected.153

The epithelioid blue nevus was first described in patients with the Carney complex. The latter term refers to a group of autosomal dominant conditions that include myxomas of heart and skin, endocrine dysfunction, schwannomas, and varying types of pigmented cutaneous lesions, including ephelides and lentigines. One variant, the LAMB syndrome (lentigines, atrial myxoma, mucocutaneous myxomas, blue nevi) also includes blue nevi with microscopic features of epithelioid blue nevi.154 However, this type of blue nevus has also been seen in patients who do not have evidence for the Carney complex.155 Clinical descriptions indicate that these present as darkly pigmented nodules or plaques that may range between 1 and 2 cm in diameter.155 Epithelioid blue nevi have a favorable clinical course, but “metastasis” to regional lymph nodes has been reported.156,157 For that reason, it has been proposed that epithelioid blue nevi be grouped with so-called “animal type” melanoma under the rubric “pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma,” which is believed to better characterize the intermediate biologic activity that both of these tumors possess152 (see subsequent discussion).

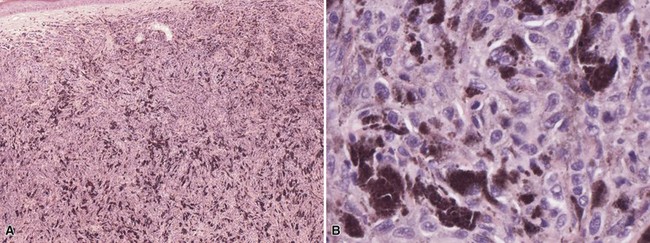

Microscopic Findings: The common blue nevus is composed of circumscribed aggregates of spindled to dendritic intradermal melanocytes containing fine granules of melanin (Fig. 28-23). Although pigmentation of these lesions is usually obvious, a hypopigmented to amelanotic variant of common blue nevus has been described (Fig. 28-24A and B).158,159 Junctional aggregates of dendritic melanocytes have also been reported, although this is distinctly uncommon.160 The melanocytes show a slender, branching network of dendritic processes with small, elongated, and hyperchromatic nuclei without significant atypia or mitotic figures.152 Melanophages and sclerosis of collagen are often present. The dendritic melanocytes of blue nevus stain positively for S-100, HMB-45, and MART-1/Melan-A,161,162 although one study found that HMB-45 staining was negative or weakly positive in a group of amelanotic blue nevi.158

Figure 28-23 Blue nevus. This is a conventional blue nevus, composed of circumscribed aggregates of heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes.

Figure 28-24 Hypopigmented blue nevus. A, At low magnification, there appears to be a proliferation of small, bland-appearing cells that could be confused with neurofibroma or dermatofibroma. B, On higher magnification, it can be seen that the dendritic cells contain small amounts of melanin. This can be confirmed with Fontana-Masson stain or with melanocytic immunohistochemical markers.

The cellular blue nevus demonstrates a biphasic appearance with classic areas of common blue nevus and distinctly cellular areas densely packed with spindled to oval melanocytes with clear or finely pigmented cytoplasm (Fig. 28-25A-C).163 Cytologic atypia is minimal, cell necrosis is not observed, and mitoses only rarely encountered. An “ancient” form of cellular blue nevus does possess pleomorphic melanocytes, but there are also degenerative changes, including edema, myxoid change, hyalinization of stroma, and “angiomatous” features.164 There is also an atypical blue nevus, characterized by asymmetry, infiltrative margins, and/or cytologic atypia with mitotic activity; these lesions tended to show a higher proliferative index using proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and Ki-67 but demonstrated a similar natural history to that of conventional cellular blue nevus.165

Figure 28-25 Cellular blue nevus. A, The superficial portion of this lesion resembles a common blue nevus, whereas the deeper portion is composed of cellular islands that contain spindled to oval melanocytes. B, In this example, the deeper cellular islands have dispersed following removal and processing. C, Often, the deep component of a cellular blue nevus displays a well-demarcated, rounded or “pushing” border.

The epithelioid blue nevus is a darkly pigmented, symmetrical dermal melanocytic proliferation. There are three cell types: dendritic, pigmented polygonal, and large epithelioid. The latter cells are also polygonal, and they have generous amounts of cytoplasm and centrally located, rounded, vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Maturation descent is not convincingly displayed in these lesions.154,155

Differential Diagnosis: Common blue nevi are usually not difficult to recognize. However, two particular problems can occur. First, cutaneous melanoma metastases can resemble blue nevi of either conventional or epithelioid type. An example is provided in a report of such lesions in a patient with ocular melanoma.166 Confirmation of the diagnosis in that case was aided by the findings of nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity. Fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis can also be helpful, in that significant, differentiating chromosomal aberrations can be found in metastatic melanoma lesions, particularly related to gains in 6p25 relative to centromere 6.167 The hypomelanotic common blue nevus should be distinguished from other benign spindle cell tumors, such as dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, or dermal scar. Fontana-Masson staining may reveal subtle melanin pigment not seen on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, and the cells stain for other melanocytic markers, including S-100, HMB-45, and Mel-5.158,159,163 Sclerotic lesions could be confused with desmoplastic melanoma, but significant nuclear pleomorphism or mitotic activity is not observed and HMB-45 staining is not usually seen in desmoplastic melanoma. Cellular blue nevi should be distinguished from the so-called malignant blue nevus, probably better designated melanoma arising in or resembling a blue nevus.168 In contrast to cellular blue nevus, melanomas arising in or resembling blue nevus are larger and more asymmetrical, irregularly lobulated, and hypercellular, and have greater degrees of cytologic atypia, tumor necrosis, and mitotic activity.169 A more difficult problem is the separation of atypical cellular blue nevi from these forms of melanoma, where the differences are largely a matter of degree.165,170 Both lesions require complete excision and close clinical follow-up.

Other Dermal Melanocytoses

Clinical Features: The term dermal melanocytosis is most often applied to lesions that are macular, bluish in color, and show widely scattered pigment-containing melanocytes in the reticular dermis with few other abnormalities. The entities included in this group are lumbosacral melanocytosis, also termed Mongolian spot; nevus of Ota (nevus fuscoceruleus ophthalmomaxillaris); nevus of Ito (nevus fuscoceruleus acromiodeltoideus); and acquired dermal melanocytosis. Most are congenital or begin in early childhood (with the exception of acquired dermal melanocytosis). Each of these presents as bluish macules in the corresponding anatomic locations; acquired dermal melanocytosis frequently occurs over the face and extremities.171 Nevus of Ota corresponds to the distribution of the trigeminal nerve and often involves the ipsilateral sclera; bilateral examples have been described.172 There is also a rare report of bilateral nevus of Ito.173 Dermal melanocytoses are most commonly, but not exclusively, encountered in dark-skinned individuals.174 Nevus of Ota is much more common in women than in men.175 Although these are generally considered benign lesions, melanoma has been reported to arise in association with nevus of Ota, variously developing in ocular tissues, skin, and meninges.176–178 Melanoma has only rarely occurred within a nevus of Ito179 or in acquired dermal melanocytosis associated with a nevus spilus.180 Lasers and/or pulsed light systems have been used to treat uncomplicated dermal melanocytoses.181,182

Microscopic Findings: Each of the dermal melanocytoses features widely scattered cells with delicate dendritic process within the reticular dermis. These contain melanin granules, although they are not necessarily heavily pigmented.183 In nevus of Ota and nevus of Ito, melanocytes tend to be more numerous and may be found in the papillary as well as the reticular dermis184,185 and around appendages (Fig. 28-26A and B).186 The more superficial location of these cells may account for the shades of brown pigment sometimes seen clinically in these lesions. Nodular foci display more concentrated dendritic melanocytes, thereby closely resembling blue nevi.187 Acquired dermal melanocytosis features melanocytes within the upper to mid-dermis, and there appears to be no significant difference in distribution of these cells between acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules and other forms of acquired dermal melanocytosis.188

Figure 28-26 Dermal melanocytosis (nevus of Ito). A, The low-power view shows minimal abnormality, although this example did display basilar hypermelanosis with pigment incontinence, creating a focally brown appearance of the clinical lesion. B, Occasional dendritic melanocytes in the deep dermis show cytoplasmic pigment.

Differential Diagnosis: In lesions with few dermal melanocytes that are widely distributed and only lightly pigmented, it may be difficult to make a diagnosis of dermal melanocytosis in the absence of a strong index of suspicion or clinical guidance. This is particularly the case for Mongolian spots. Therefore, dermal melanocytosis should be included as one of the potential “invisible dermatoses.” Blue nevus differs by having more concentrated aggregates of pigmented dendritic melanocytes, although again, occasional nodular foci within dermal melanocytoses can be virtually indistinguishable from blue nevi.

Neurocristic Hamartoma

Clinical Features: Neurocristic cutaneous hamartomas are rare pigmented skin lesions that may be congenital or acquired. Although some are based in the deep subcutaneous tissue, a variant termed “pilar neurocristic hamartoma” is more superficial and perifollicular in location. These hamartomas are believed to result from aberrant development of the neuromesenchyme. In addition to a dermal/subcutaneous melanocytic component, they can also contain neurosustentacular and neuromesenchymal elements and can undergo malignant transformation. Some lesions present as bluish macules and can have a widespread distribution,189 whereas others are plaquelike.190 Pilar neurocristic hamartoma can present as a patch composed of perifollicular papules.191 Melanoma can arise in neurocristic hamartoma,192 but the risks of occurrence and degree of biologic aggressiveness are not predictable. It does appear that melanomas arising in these lesions are biologically distinct from more common cutaneous melanomas in that, whereas they demonstrate local invasion, distant metastasis is often a late event.192,193

Microscopic Findings: Neurocristic hamartomas show intermingling of nests of cuboidal cells, fascicles of spindled cells, and heavily pigmented, dendritic cells. Perivascular pseudorosettes demonstrate nuclear palisading of the pigmented cells. Mixtures of Schwann cells and neuromesenchyme are also seen, but not invariably. Much of this process is seen within the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 28-27A-D),189 although the perifollicular distribution of pilar neurocristic hamartoma is distinctive.191 Immunohistochemical staining is positive for S-100, HMB-45 (variably), and Melan-A.189 Some foci are positive for S-100 and leu7 and negative for HMB-45, sometimes surrounded by spindled cells positive for epithelial membrane antigen; this suggests neural differentiation.

Figure 28-27 Neurocristic hamartoma. This is an unusually extensive example of subcutaneous pigmentation. A, Epithelioid to fusiform cells with extensive surrounding pigment. B, Higher power view showing cellular detail. C, A discrete subcutaneous nodule, found on positron emission tomography, is composed of bland-appearing, small cuboidal cells with relatively sparse pigmentation. D, Ki-67 activity is sparse within this nodule.

Differential Diagnosis: Neurocristic hamartomas have many features in common with variants of blue nevus, including cellular blue nevi, and with some congenital nevi. Yet the distribution of cells and depth and extent of involvement are quite different from most examples of those lesions.194

Congenital Nevus

Clinical Features: Congenital nevi are often classified by size and can be divided into three groups: giant (20 cm or more in greatest diameter), intermediate (1.5 to 19.9 cm in greatest diameter), and small (<1.5 cm in greatest diameter). The uncommon giant variety, as the name implies, appears at birth and particularly involves areas of the trunk such as the chest, back, shoulders, sacrum, and buttocks (hence the term “bathing trunk nevus”), but lesions can involve other areas as well, such as the scalp or hand. Leptomeningeal involvement occurs with some large or extensive congenital nevi.195 These nevi are frequently elevated, may be verrucous, and sometimes possess considerable amounts of hair. Smaller satellite lesions also occur, representing café-au-lait spots, connective tissue nevi, or smaller versions of congenital nevus. Incidence estimates range between 0.2% and 6% overall (0.0005% for giant congenital nevi.97,196,197 Smaller congenital nevi can appear virtually identical to acquired melanocytic nevi; they are usually round to ovoid, symmetric, and well delineated. Additional features of congenital nevi can include perifollicular hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation, papular or rugose texture, asymmetry, and color variation.198 Major clinical issues with congenital nevi are cosmetic disfigurement (particularly with larger nevi) and the potential risks of the development of melanoma. Current studies suggest that there is minimal risk of melanoma arising in small-sized or intermediate-sized congenital nevi—probably about the same risk as that for acquired nevi.199,200 The risks of melanoma arising in giant congenital nevi vary depending on the study, and higher percentages are no doubt often influenced by referral biases; however, the lifetime risk has been estimated to be about 6.3%.201 Excision is recommended for small, changing lesions, and staged excisions are often carried out for the larger congenital nevi, along with close and long-term clinical follow-up.

Microscopic Findings: Intermediate and giant congenital nevi demonstrate considerable radial extent and depth of involvement, sometimes involving the subcutis and fascia. There is often a grenz zone separating diffusely distributed dermal nevus cells from the overlying epidermis, which may appear almost normal or show lentiginous changes. At times, more superficial dermal melanocytes are pigmented, whereas there may be diminution or absence of pigment in deeper portions of the lesion (Fig. 28-28). Nevus cells appear to splay the dermal collagen bundles and surround, or be found within, adnexal epithelia, nerves, and vessels. Spindled cells are found, particularly at the base of some lesions, and neuroid elements can sometimes be identified.202 Although all of these features taken together clearly indicate a congenital nevus, there appears to be no one completely pathognomonic change that ensures that a particular lesion is congenital, with the possible exception of nevus cell aggregates within sebaceous lobules (Fig. 28-29).203–205 Pagetoid changes can be seen within the epidermis in some congenital nevi in childhood; cytologic atypia tends to be minimal.203 Proliferative nodules are sometimes observed, particularly in giant congenital nevi but occasionally in smaller lesions as well. These consist of one or more cellular aggregates that are composed of spindled or epithelioid cells and are variably pigmented. Features indicating that these nodules are benign include limited cytologic atypia, coarse pigmentation (as opposed to finely divided pigmentation), a lack of cell necrosis or mitotic activity, and evidence that the cells within the nodule blend with surrounding melanocytes at the periphery (Fig. 28-30A and B).186,203 Smaller congenital nevi may be indistinguishable from common acquired nevi. Splaying of the collagen by nevus cells that also surround adnexal structures is considered suggestive of congenital nevus but not specific (Fig. 28-31),204,206 whereas the finding of nevus cells with adnexal epithelia or vessels in deeper portions of a lesion is stronger evidence of congenital origin.207

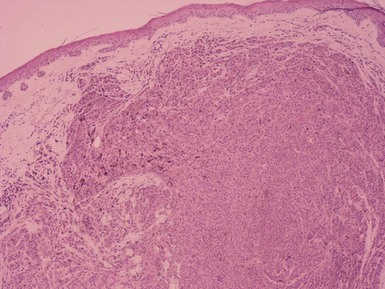

Figure 28-28 Giant congenital nevus. Virtually all the cells seen in the dermis in this specimen are melanocytes. The superficial dermal melanocytes are heavily pigmented. In this example, there is a grenz zone separating the dermal melanocytes from the overlying epidermis.

Figure 28-29 Giant congenital nevus. Involvement of a sebaceus gland is considered by some to be a pathognomonic finding of congenital nevus.

Figure 28-30 Proliferative nodule in a giant congenital nevus. A, This rather large nodule blended with the surrounding melanocytes. It is composed of small, monotonous cells with minimal pigmentation. B, Detail of the cells within the nodule, showing a lack of significant cytologic atypia, cell necrosis, or mitotic activity.

Differential Diagnosis: The most important diagnostic issue in congenital nevus is ruling in (or out) the development of melanoma in these lesions. As noted earlier, pagetoid change can occur in congenital nevi, but in contrast to melanoma, the upwardly migrating cells do not reach the epidermal surface and display a limited degree of atypia. Melanomas arising in giant congenital melanocytic nevi are found in the dermis and are composed of epithelioid, spindled, or small round cells that should display pleomorphism, necrosis, and mitotic activity.193,208,209 Melanoma tumor nodules also have a sharp margin at their interface with the surrounding nevus; in contrast, the benign proliferative nodules tend to be smaller and blend with the surrounding nevus cells.186

Dysplastic Nevus (Atypical Nevus; Architecturally Disordered Nevus with or without Cytologic Atypia)

Clinical Features: For some years it has been recognized that there is a group of melanocytic lesions having similar microscopic characteristics that deviate to varying degrees from what are considered to be ordinary, banal melanocytic nevi. Lesions with these histopathologic features can be seen in the dysplastic nevus syndrome, which has largely been defined by a particular clinical phenotype and a familial history. Over the years, there have been objections to use of the term “dysplastic nevus,” partly on etymologic grounds and partly because lesions with the set of microscopic features to be described below are not uniquely associated with the dysplastic nevus syndrome. Thus, in 1989, Clark stated that the preferred diagnosis is “nevus with melanocytic dysplasia of the type which may be seen in the dysplastic nevus syndrome.”210 As a result, there have been several efforts to come up with alternative terms for this particular type of nevus. One has been to use eponymic designations (i.e., Clark nevus in place of dysplastic nevus, along with Unna nevus for exophytic, papillomatous nevi, Miescher nevus for dome-shaped lesions with wedge-shaped extension into the reticular dermis, and Spitz nevus for lesions with the microscopic features described earlier in this chapter).211 Another has been to replace dysplastic nevus with “atypical nevus” or “architecturally disordered nevus, with or without cytologic atypia.” With those caveats, the author uses “atypical nevus” in this section, not to take sides in the controversy but mainly as a matter of convenience.