ON SEPTEMBER 25, 1949, ROUGHLY five thousand residents of Los Angeles huddled together downtown beneath a massive “canvas cathedral tent” at the corner of Washington and Hill. They had come to this place, in the shadow of the metropolitan courthouse, to hear an evangelical preacher tell them about a judgment that would be handed down by God rather than man. Only thirty years old and still largely unknown, Billy Graham nevertheless made a commanding impression as he strode onto the stage. Dressed sharply in a trim double-breasted suit with his wavy blond hair swept back, he set his square jaw and locked his eyes on the crowd. Drawing on the biblical story of Sodom and Gomorrah, the preacher told them that their so-called City of Angels shared many of the “wicked ways” of those infamous cities—sexual promiscuity, addictions to drink and “dope,” teenage delinquency, rampant crime—and it would inevitably share their fate of destruction unless its citizens repented and reformed. In many ways, Graham’s sermon that day was a preacher’s perennial, a warning of God’s wrath and a call for penitence. But his message took on unusual urgency because of an event then dominating the news. Just two days earlier, Americans had learned that the Soviet Union now had the atomic bomb.1

The energetic young Graham seized on the headlines to make the Armageddon foretold in the New Testament seem imminent. “Communism,” he thundered, “has decided against God, against Christ, against the Bible, and against all religion. Communism is not only an economic interpretation of life—communism is a religion that is inspired, directed, and motivated by the Devil himself who has declared war against Almighty God.” He urged his audience to get religion not simply for their own salvation but for the salvation of their city and country. Without “an old-fashioned revival,” he warned, “we cannot last!” A virtual unknown when he began this “Christ for Greater Los Angeles” evangelistic campaign, the charismatic preacher rode the rising wave of nuclear anxiety to national prominence. Initial reports in the Hearst papers and wire services were soon followed by longer, glowing stories in Time, Life, and Newsweek. With crowds soon swarming to the outdoor revival, Graham had to extend his stay from the original three weeks to eight in all. When the Los Angeles revival finally came to a close in November 1949, organizers reported that a total of 350,000 people had attended. And Billy Graham had transformed himself into a rising star: a servant of God ready to fight the Cold War.2

In the conventional historical narrative, Graham’s dramatic debut on the national stage has been presented as part of a broader story of action and reaction: the Soviet Union discovered the bomb, and the United States rediscovered God. There are, to be sure, some grounds for the argument that the tensions of the early Cold War era helped fuel the religious revival of midcentury America.3 As Americans confronted the reality that nuclear war might destroy the nation, countless people were certainly driven to prayer. But the spiritual revival of the postwar era was much more than fallout from the nuclear age. Its roots predated the Cold War, and its importance and impact stretched well beyond the concerns of that conflict. Despite all the attention Graham gave foreign threats in his “canvas cathedral” debut, his public ministry—especially in these early years—was much more concerned with domestic matters. He was not alone. Three important movements in the 1940s and early 1950s—the prayer breakfast meetings of Abraham Vereide, Graham’s evangelical revivals, and the presidential campaign of Dwight D. Eisenhower—encouraged the spread of public prayer as a political development whose means and motives were distinct from the drama of the Cold War. Working in lockstep to advance Christian libertarianism, these three movements effectively harnessed Cold War anxieties for an already established campaign against the New Deal.

Just as Spiritual Mobilization used faith to defend free enterprise, these movements called for a return to prayer to advance the same ends. Graham was the most prominent of the new Christian libertarians, a charismatic figure who spread the ideas of forerunners such as Fifield to even broader audiences. In 1954, Graham offered his thoughts on the relationship between Christianity and capitalism in Nation’s Business, the magazine of the US Chamber of Commerce. “We have the suggestion from Scripture itself that faith and business, properly blended, can be a happy, wholesome, and even profitable mixture,” he observed. “Wise men are finding out that the words of the Nazarene: ‘Seek ye first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things shall be added unto you’ were more than the mere rantings of a popular mystic; they embodied a practical, workable philosophy which actually pays off in happiness and peace of mind. . . . Thousands of businessmen have discovered the satisfaction of having God as a working partner.”4

Billy Graham partnered with a number of businessmen himself. Following the lead of Methodist minister Abraham Vereide, Graham helped introduce captains of industry to the incredible power of prayer. In his hands, prayer was not simply a means of personal salvation but also, and just as important, a tool to improve the public image of their companies. In 1951, for instance, the Chicago & Southern Airline invited him to preach a dedicatory sermon aboard a four-engine airplane that had been outfitted with a pulpit and an electric pump organ. As the crew and congregation circled above Memphis, Graham led them in a solemn prayer that “the great C&S Airline may be blessed as never before.” Years later, the minister would touch down in Memphis again to speak before a convention of hotel owners, where he furnished a similar sort of benediction. “God bless you and thank you,” Graham said earnestly, “and God bless the Holiday Inns.”5

Graham’s warm embrace of business contrasted sharply with the cold shoulder he gave organized labor. The Garden of Eden, he told a rally in 1952, was a paradise with “no union dues, no labor leaders, no snakes, no disease.” The minister insisted that a truly Christian worker “would not stoop to take unfair advantage” of his employer by ganging up against him in a union. Strikes, in his mind, were inherently selfish and sinful. In 1950, he worried that a “coal strike may paralyze the nation”; two years later, he warned that a looming steel stoppage would hurt American troops fighting in Korea. If workers wanted salvation, they needed to put aside such thoughts and devote themselves to their employers. “The type of revival I’m calling for,” Graham told a Pittsburgh reporter in 1952, “calls for an employee to put in a full eight hours of work.” On Labor Day that same year, he warned that “certain labor leaders would like to outlaw religion, disregard God, the church, and the Bible,” and he suggested that their rank and file were wholly composed of the unchurched. “I believe that organized labor unions are one of the greatest mission fields in America today,” he said. “Wouldn’t it be great if, as we celebrate Labor Day, our labor leaders would lead the laboring man in America in repentance and faith in Jesus Christ?”6

His hostility to organized labor was matched by his dislike of government involvement in the economy, which he invariably condemned as “socialism.” Graham warned that “government restrictions” in the realm of free enterprise threatened “freedom of opportunity” in America. In April 1952, he stood outside the Texas state capitol and insisted, “We must have a revolt against the tranquil attitude to communism, socialism, and dictatorship in this country.” The next month, Graham spoke at a businessmen’s luncheon in Houston, warning that socialism was on the march around the world as well. “Within five years we can say good-by to England,” he insisted. “Japan could go communist within two years. The United States is being isolated.” Two years later, Graham’s thoughts on the dangers of socialism became a bit of an international scandal after the Billy Graham Evangelical Association sent followers a free calendar. A page on England noted that “when the war ended a sense of frustration and disillusionment gripped England and what Hitler’s bombs could not do, socialism with its accompanying evils shortly accomplished. England’s historic faith faltered. The churches still standing were gradually emptied.” Learning of the slight, a columnist for the London Daily Herald denounced Graham with a new nickname: “the Big Business evangelist.”7

As preachers like Billy Graham helped to popularize public prayer, they thus managed to politicize it as well. They shared the Christian libertarian sensibilities of Spiritual Mobilization but were able to spread that gospel in much subtler—and much more effective—ways than that organization ever could. At the same time, their work helped to democratize the phenomenon of public prayer. Spiritual Mobilization focused its attention largely on ministers, but these contemporaneous campaigns attracted a much broader swath of laypeople. Though they tended to target the rich and powerful, the changes they instituted ultimately made the movement more accessible to ordinary Americans and thereby set the stage for a larger revival to come. In the political ascendancy of Dwight D. Eisenhower, the prayers of Christian libertarians were finally answered.

FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S FIRST INAUGURAL address had been filled with scriptural references, but in his second inaugural in January 1937 religion was even more pronounced. Reflecting on the record of progressive legislation and economic progress in the first four years of his administration, the president portrayed himself, rather unsubtly, as a modern-day Moses leading his people out of the wilderness. “Shall we pause now and turn our back upon the road that lies ahead? Shall we call this the promised land?” he asked rhetorically. “Or shall we continue on our way?” There was still much to be done, he warned, but the nation would soon reach “our happy valley” if it stayed on the present path. The Exodus theme of the inaugural address, speechwriters insisted, had come entirely from Roosevelt. But others still sought credit. In February 1937, Abraham Vereide sent the president a letter reminding him of a meeting they had had more than four years earlier, when Roosevelt was still governor of New York. “You may recall,” the Seattle minister wrote, “that I reminded you about the story of Moses and the Israelites, stating that you were our Moses and we were Israel who needed to be led out of the bondage of Egypt, into the Promised Land. You may recall your own statement at that time and your pledge. Your efforts have been true to that pledge.”8

While Vereide’s praise for the president’s religious rhetoric was sincere, his claim that he saw Roosevelt as a modern-day Moses most certainly was not. The Methodist clergyman was thoroughly conservative in his politics and, by the time of his letter, had long abandoned any belief in the worth of either private charity or public welfare. A deeply pious Norwegian, he had immigrated to America in 1905 and, a decade later, begun work as a minister in Seattle. During the 1920s, he ran Goodwill Industries’ operation in the city with efficiency, organizing forty-nine thousand housewives into thirty-seven districts to collect used goods for the needy. While his approach to running the charity was businesslike, so too was his attitude toward the underlying idea. “Promiscuous charity pauperizes,” he insisted in 1927, “and the average person seeking aid . . . does not want to work for it.” Nevertheless, his success in Seattle led to promotions at Goodwill and, ultimately, consideration by Roosevelt for a role leading the federal relief effort, consideration that led to their 1933 meeting in Albany. But as Vereide became more involved with charity work, he became less sure of its worth. “In conference with heads of governments and unemployment committees in New England and New York,” he later remembered, “I became convinced that [the] depression was moral and spiritual as well as material. The country needed a spiritual awakening as the only foundation for economic stability.” In 1934, Vereide resigned from Goodwill and began searching for a new career.9

Nearly fifty at the time, with trim white hair and a perpetually serious gaze, Vereide found the turmoil of his professional life mirrored in the nation. When the Methodist minister returned to the West Coast, he found businessmen and labor unions embroiled in an epic struggle that helped give him a new sense of purpose. First he spent three months in San Francisco, where the Industrial Association had recently retaliated against a dockworkers’ strike by assembling a private army to open the port by force, killing two strikers in the process. In response, the longshoremen convinced the rest of the city’s unions to join them in a general strike that effectively shut down San Francisco for days. Highways were blockaded, shipments of food and fuel turned away. As the city’s elite holed up in the posh Pacific Union Club, debating how to handle the largest labor uprising they had ever seen, Vereide ministered to them in regular prayer meetings.10

When the clergyman returned to Seattle soon after, he found it in a similar state of chaos. The city’s stevedores went on strike, and the Waterfront Employers Association prepared for a massive struggle. They put three ships in port to serve as barracks for an army of strikebreakers recruited from wherever they could be found, including fraternities at the University of Washington. Strikers kept control of the port, leaving dozens of ships idling in the harbor. Local newspapers gave voice to the worries of the business community. “Strike Costing City a Million a Day!” screamed the Seattle Times. The Post-Intelligencer grumbled that “a mob of striking longshoremen” had “paralyzed Seattle shipping.” As pressure mounted, the mayor personally led three hundred policemen, armed with tear gas and submachine guns, down to the docks to break the strike. In the ensuing struggle, both sides suffered serious injuries before calling an uneasy truce. The next spring, in April 1935, union leaders from all over the West Coast descended on Seattle to make plans for an even greater wave of strikes that summer.11

That same month, Vereide had an important meeting of his own. On a downtown street corner he ran into Walter Douglass, a former Army major and a prominent local developer. The two soon began commiserating about how the entire country was, in Douglass’s words, “going to the bow-wows.” “The worst of it is you fellows aren’t doing anything about it!” he snapped at the minister. “Here you have your churches and services and a merry-go-round of activities, but as far as any actual impact and strategy for turning the tide is concerned, you’re not making a dent.” The wealthy developer said clergymen needed to “get after fellows like me” and motivate them to get involved. He offered Vereide a suite of offices in the downtown Douglass Building and “a check to grubstake you” if only he would take the job. Vereide readily accepted. The two men immediately made their way to the offices of William St. Clair, president of Frederick and Nelson, the largest department store in the Pacific Northwest, and one of the richest men in Seattle. “He made a list of nineteen executives of the city then and there,” Vereide later remembered, and invited them for breakfast at the Washington Athletic Club. The men at that first prayer meeting included the presidents of a gas company, a railroad, a lumber company, a hardware chain, and a candy manufacturer, as well as two future mayors of Seattle. Only one belonged to a church at the time, but even he had little use for religion, joking that the others knew him only as a gambler, a drinker, and a golfer—someone who swore so much “the grass burns when I spit.” But like the others, he rallied to Vereide’s call and joined what became a regular prayer breakfast for businessmen called the City Chapel. Their services were nondenominational, but the message that came from their meetings was one that called for a return to what they saw as basic biblical principles.12

That summer, the City Chapel held a retreat for Seattle’s elite at the Canyon Creek Lodge in the Cascade Mountains. With labor unrest still simmering on the city’s docks, the business leaders were worried. “Subversive forces had taken over,” Vereide recalled. “What could we do?” After a great deal of prayer, city councilman Arthur Langlie rose from his knees and announced, “I am ready to let God use me.” Others were ready to use him as well. The president of a securities corporation immediately offered financial support for a Langlie mayoral campaign, and others soon followed. On his first run for the office in 1936, the Republican came up short. His opponent secured the backing of the city’s powerful unions and ominously warned voters about Langlie’s affiliation with “a secret society,” by which he meant not the City Chapel but a right-wing organization called the New Order of Cincinnatus. In 1938, however, labor split evenly between two competing candidates, allowing Langlie to win in what was understood nationally as a major coup for conservatism. “Seattle Deals Radicals Blow,” read the headline in the Los Angeles Times; “Left-Wing Nominees Decisively Beaten in Mayoralty Election.” The New York Times likewise called Langlie’s election “a sweeping victory for conservatism,” while the Wall Street Journal argued that the victory of the candidate who “promised industrial peace” had helped boost the market value of Seattle’s municipal bonds considerably. From the mayor’s office, Langlie’s star continued to rise. Only two years later, he won election as governor of Washington, ultimately serving three terms, first from 1941 to 1945 and then again from 1949 to 1957. Now a nationally prominent Republican, Langlie made the short list for Dwight Eisenhower’s running mate in the 1952 presidential campaign and then delivered the keynote address at the 1956 Republican National Convention.13

After establishing the breakfast group in Seattle, Vereide looked to expand his efforts to the rest of the nation. “Business and social leaders throughout the country are recognizing that economic reconstruction must begin with an individual recovery from within,” he noted in 1935. “They are beginning to realize that we cannot solve all the problems of our present-day civilization by our wits, but must rely on a higher power to help. They hope to revive the spiritual life in commerce, to aid the churches and to get back to a real American home life.” Accordingly, when they filed articles of incorporation, the founders of City Chapel announced their intention “to foster and promote the advancement of Christianity and develop a Christian nation.” As the Seattle group flourished, businessmen in other communities reached out to Vereide in hopes of starting ones of their own. The minister informed them that the organization followed “a non-political and non-denominational” program, but quickly added a line that suggested a political leaning akin to that of Spiritual Mobilization. “We believe with William Penn: ‘Men must either be governed by God or ruled by tyrants,’” he said. Through personal visits and correspondence, Vereide created a network of prayer groups across the nation. In San Francisco, a former secretary of the navy established one at the Olympic Club. The head of a wool trading business started another at the Boston City Club. A set of businessmen convened at the Lake Shore Club in Chicago to begin their own group, while an oilman did likewise with associates in Los Angeles. In New York City, Republican mayor Fiorello LaGuardia was so taken with the idea he sought Vereide’s assistance in getting a group started there too. The minister traveled tirelessly around the country to organize and mobilize new meetings. In a letter home that seemed routine for these years, Vereide noted in passing that he had “just returned from a visit with some of these groups in St. Paul, Minneapolis, Chicago, St. Louis, Miami, Palm Beach and Daytona Beach, and before that at Philadelphia and Baltimore.”14

Of all the cities enamored by the prayer breakfasts, none was more important than Washington, D.C. Vereide had not only national ambitions from the beginning but political ones as well. Even though businessmen had taken the lead in forming the City Chapel in Seattle, their meetings quickly became an important political rite of passage. A typical session in January 1942, for instance, attracted more than sixty business and civic leaders, including a national director of J. C. Penney, the president of the Seattle Gas Company, a railroad executive, a municipal court judge, and two naval officers. Notably, representatives of both political parties were on hand and, despite their different partisan affiliations, showed unanimity when it came to the rites of public prayer. A Democratic contender for the governor’s office gave the opening prayer, with the brother of the incumbent Republican offering comments; the closing prayer, meanwhile, came from the Republican candidate for the US Senate. The same month as that gathering in Washington State, Vereide held an organizational meeting for new breakfast groups in Washington, D.C. In the midst of a massive blizzard, he brought together seventy-four prominent men—mostly congressmen, but with a few business and civic leaders as well—for a luncheon at the Willard Hotel. They heard testimonials to his work from Howard B. Coonley, the far-right leader of the National Association of Manufacturers, and Francis Sayre, former high commissioner to the Philippines and Woodrow Wilson’s son-in-law. “I told the story of the Breakfast Groups,” Vereide remembered, “and suggested to members of Congress that they begin to meet in a similar fashion and set the pace for our national life, in order that we might be a God-directed and God-controlled nation.” The next week, the House of Representatives breakfast group began with Thursday morning meetings held in the Speaker’s dining room; a regular Senate group soon met as well, on Wednesday mornings in a private room in that chamber’s restaurant.15

These congressional breakfast meetings quickly became a fixture on Capitol Hill. Each month, Vereide printed a program to guide the groups in their morning meditations, offering specific readings from Scripture and providing questions for discussion. The groups were officially nonpartisan, welcoming Republicans and Democrats alike, but that was not to say they were apolitical. Most of the Democratic members of the House breakfast group, for instance, were conservative southerners who held federal power and the activism of the New Deal state in as much contempt as the average Republican did.16 Political overtones were lightly drawn but present nonetheless. “The domestic and the world conflict is the physical expression of a perverted mental, moral and spiritual condition,” noted a program for a House session. “We need to repent from our unworkable way and pray.” The congressional prayer meetings gave Vereide immediate access to the nation’s political elite. In January 1943, just a year after his introductory meeting at the Willard Hotel, the minister marveled to his wife how he was not simply mingling with important political figures but actively enlisting them in his crusade. “My what a full and busy day!” he began. “The Vice President brought me to the Capitol and counseled with me regarding the program and plans, and then introduced me to Senator Brewster, who in turn [introduced me] to Senator Burton—then planned further the program and enlisted their cooperation,” he continued. “Then to the Supreme Court for visits with some of them, and secured their presence and participation—then back to the Senate, House—and lunch with Chaplain Montgomery.” The rest of the day, and the ones that followed, were packed with meetings, but Vereide pressed ahead. “The hand of the Lord is upon me,” he noted in closing. “He is leading.”17

Having won over political leaders in Washington, D.C., Vereide used their influence to establish even more breakfast groups across the nation. Businessmen in Cleveland had been interested in forming a regular prayer meeting, for instance, but they told Vereide that there was “a class of men we have not been reaching” and asked for help. “I am told that our own Senator Harold Burton is a member of one of your groups in Washington,” wrote an organizer. “He is very favorably known in Cleveland as a church man and we are just wondering whether an invitation or other promotion material might carry considerable more weight if it could go out over his name as an honorary chairman or some such title.” Vereide arranged for an immediate meeting with the Republican senator and secured his support. The very next day, Burton sent the organizers a list of prominent Clevelanders whom they should recruit. “You perhaps might also wish to quote some portion of this letter as indicating my interest in the movement,” the senator volunteered. “It is important that there be deep-seated, moral convictions which shall form the basis for our daily decisions in business and in government.”18

The contacts Vereide made in congressional prayer groups also gave him access to corporate leaders across the country. NAM president Howard Coonley had helped launch the breakfast meetings, and by 1943, both the past president and the current president of the US Chamber of Commerce were regular participants at the Senate sessions. Corporate titans followed their lead, inviting Vereide to join them for private meetings in their offices or small dinners with fellow executives. “The big men and real leaders in New York and Chicago,” he wrote his wife, “look up to me in an embarrassing way.” In Manhattan, Thomas Watson of IBM gathered together “a few of New York’s top men” for a luncheon at the Bankers Club to meet Vereide and hear about his work. J. C. Penney took the minister to lunch at New York’s Union League Club, arranged for a meeting with Norman Vincent Peale, and then promised to set up “a retreat for key business executives” soon after. In Chicago, Vereide lunched at its Union League Club with “fifteen top leaders,” including Hughston McBain, president of the Marshall Field department store chain. Other corporate titans sought more intimate audiences. The head of Quaker Oats spent an hour with Vereide in his Chicago office, while the president of Chevrolet spent more than three with him in Detroit. Given his travels, Vereide inevitably won support from the Pew family as well. While James Fifield had found a patron in J. Howard Pew, Vereide won support from his brother Joseph Newton Pew Jr., head of the massive Sun Shipbuilding Company and a powerful force in the Republican Party in Pennsylvania. As the minister shuttled back and forth between the private and public sectors of power in America, his success quickly became a self-fulfilling prophecy. The more politically connected he became, the more leading businessmen sought time with him. And the more backing he secured from corporate titans, the more eager politicians were to count themselves as his friend. Vereide believed he was bringing these influential people closer to God—but he was also bringing them closer to one another, and in a forum that seemed as pure and patriotic as possible.19

During the war, Vereide brought together his newfound political and corporate supporters to serve on the board of directors for the new national version of City Chapel, which he called the National Council for Christian Leadership (NCCL). By 1946, the forty-five members of the board represented an impressive range of public and private power in America. From the political arena, its number included eight members of the US Senate and ten representatives in the US House. Drawn in equal numbers from the Republican and Democratic parties, the congressmen were almost universally conservative in their politics. (Former senator Harold Burton, by then appointed to the Supreme Court, still served on the board with his former congressional colleagues.) These political leaders were joined by a number of prominent businessmen, including NAM president Coonley, timber titan F. K. Weyerhauser, earthmoving equipment manufacturer R. G. LeTourneau, and steel magnate Roy Ingersoll. The National Council for Christian Leadership made its headquarters in Washington, D.C., where Vereide had relocated during the war. In November 1945, with considerable help from a wealthy patron, the organization had bought a four-story mansion on Embassy Row, which became its official base of operations. “This,” Vereide announced with pride, “is God’s Embassy in Washington.”20

Despite the seeming hyperbole, Vereide’s organization did reach into the highest levels of politics. In 1946, for instance, when President Truman appointed treasury secretary Fred Vinson to become the new chief justice of the United States, Vereide invited Vinson to join the Senate breakfast group for a “dedication” of his new position on the Supreme Court. A devout Methodist, Vinson readily accepted and brought along attorney general Tom Clark. Before a gathering of twenty-eight senators, the Presbyterian attorney general offered his own religious testimony, and then the new chief justice followed suit. As Vereide remembered, Vinson spoke warmly about the influence the Bible had not just on his own life but on all of American government and law. After a silent prayer, Missouri senator Forest Donnell led the dedicatory prayer, “invoking God’s blessing on the Chief Justice and dedicating him in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit to his exalted and important position.” Afterward, Vinson told Vereide that he wished the morning meeting had been “broadcast to all the American people, for he felt that it would do more than anything else to restore the confidence of the people in their government and to unite the nation in a common faith.”21

The “consecration” of the chief justice of the United States was not an aberration. Indeed, when Tom Clark and Sherman Minton were appointed to the Supreme Court in late 1949, Vereide arranged for another ceremony dedicating their new roles as well. The two new justices joined Chief Justice Vinson and a bipartisan set of senators for a special ceremony in early 1950. Virginia senator A. Willis Robertson, father of the evangelist Pat Robertson, led the group in an opening prayer, after which they polished off plates of toast and eggs. In the discussion that followed, these leaders from the judicial and legislative branches reflected on the role of prayer in political life. Senator John Stennis, a Mississippi Democrat, spoke of how America often focused on material issues, but “we must balance our planning with spirituality.” Chief Justice Vinson agreed. “I am not a preacher or even the son of a preacher,” he reflected. “But I know we must adhere to the ideals of Christianity.” Past civilizations, Vinson warned darkly, had crumbled from within as decadence removed them from their founding principles. Justice Clark wholeheartedly agreed. “No country or civilization can last,” he said, “unless it is founded on Christian values.”22

At the end of his “dedication” ceremony, Justice Sherman Minton urged those gathered to work for a closer brotherhood with the people of Europe. But Vereide had already begun just such an effort. In 1947, he unveiled a new International Council for Christian Leadership (ICCL). In theory, the ICCL was simply an extension of the NCCL, working alongside it in a common effort directed both at home and abroad. But in practice, many of Vereide’s allies worried it meant that foreign issues would take priority over domestic ones. Republican congressman John Phillips, a member of the NCCL board of directors, sent Vereide an impassioned letter in August 1948 reminding him that he had “repeatedly been told by your executive committee that there must be no connection between the two movements until the home-grown movement is stronger on its feet.” Phillips felt so strongly about the matter that he resigned from the board and asked that his name be removed from the group’s literature and letterhead. Responding with deep regret, Vereide insisted that he had never neglected their domestic priorities. “I have given myself unstintingly for the development in our nation of an appreciation for the protection of our form of government and private enterprise,” he asserted. Furthermore, the minister reasoned, any program to protect capitalism at home had to protect capitalism everywhere. “Our own economy will crack without the right relationship to [the] world economy,” Vereide argued, “and that whole structure is built on moral foundations.” The minister pressed ahead in his drive to give the organization an international presence, with quick success. Within a few years, Christian Leadership breakfast groups were meeting regularly in thirty-one foreign countries. England, France, West Germany, the Netherlands, and Finland represented the bulk of the initial growth of the group, but the ICCL made its presence felt in nations as varied as China, South Africa, and Canada, with isolated operations in localities such as Havana and Mexico City as well.23

Vereide recognized that the tensions of the Cold War could be exploited to win more converts to his cause. “The Time is Now!” he wrote members of the House breakfast group in August 1949. “On all sides today we hear people speaking fearfully of the spread of atheistic communism. Is there really anything we can do about it? Yes!” He urged the congressmen to stand up to communism in three ways—by maintaining their personal relationship with Jesus Christ; by “cultivating ‘intensive fellowships,’ i.e. the spread of small groups or cells,” back in their congressional districts patterned on their breakfast group in Congress; and by working with like-minded Christians across the country to present “a united front against the forces of the anti-Christ.” “The choice,” he insisted, “boils down to this: ‘Christ or Communism.’ There is really no other. Those in between—playing neutral—are literally playing into the hands of the enemy.”24

Just two weeks later, Americans learned that the Soviet Union now had nuclear weapons. The paranoia over the dangers posed by “godless communism” increased dramatically in the coming months and years, and so too would the campaign to Christianize America. Abraham Vereide and his associates worked tirelessly to win more converts to their cause, moving on to ever greater successes over the course of the coming decade. They would not be alone.

IN BOTH MEANS AND MOTIVES, Billy Graham’s ministry represented a continuation of Abraham Vereide’s. Fresh from his success in Los Angeles in late 1949, the sensational young preacher toured the country in a series of revivals that seemed, in the words of one biographer, “like a long Palm Sunday procession of celebration and arrival.” He began in 1950 in Boston. There, a single, lightly advertised New Year’s Eve service at Mechanics Hall attracted a crowd of more than six thousand, forcing stunned organizers to throw together a series of additional revivals at the opera house, the Park Street Church, Symphony Hall, and finally Boston Garden, where more than twenty-five thousand tried to get in. That spring, Graham held his first “crusade” in Columbia, South Carolina. Governor Strom Thurmond made regular appearances onstage at the services, as did Senator Olin Johnston and Supreme Court justice James Byrnes. Henry Luce, a devout missionary’s son who had become publisher of Time Inc., came to see Graham preach to a record crowd at the University of South Carolina football stadium. Deeply impressed, he afterward returned with Graham to the governor’s mansion, where the two stayed up late into the night discussing their faith. In the summer, the crusade came to Portland, Oregon. Frustrated by seating shortages in the earlier revivals, Graham convinced local organizers to craft a special “tabernacle” of wood and aluminum that would seat twelve thousand worshipers. Nearly twice as many tried to get into the opening night’s service; a half million more came over the next six weeks. Graham ended the year with a similar six-week revival in Atlanta, where organizers converted the Ponce de Leon baseball park to seat twenty-five thousand, ultimately drawing in another half-million worshipers. Between these extended crusades in 1950, Graham scheduled one-off revivals wherever he could, ranging from an overflow audience of twenty-five hundred at the State Auditorium in Providence, Rhode Island, to an estimated one hundred thousand at the Rose Bowl in Los Angeles. In early 1951, Billy Graham’s travels took him to Fort Worth, Texas. The four-week crusade there was an unqualified success, with a total attendance of nearly 336,000, making it the largest evangelistic campaign in the history of the state or, for that matter, the entire Southwest.25

Of Graham’s legion of admirers during the Fort Worth crusade, Sid Richardson stood out. A crusty, barrel-chested oilman, Richardson was by then one of the wealthiest men in the entire nation, if not the wealthiest. Not even the reclusive Richardson knew for sure; much of his immense fortune was buried underneath the Texas soil in his vast oil fields. Still, the journalist Theodore White declared him “far and away the richest American” in a 1954 article, suggesting that fellow Texas oilman H. L. Hunt might be “his only rival in the billion-dollar bracket.” In one of the earliest attempts to rank America’s wealthiest citizens, Ladies’ Home Journal gave Richardson the top honors in its inaugural 1957 list, estimating his overall net worth at $700 million. For his part, Richardson wore his wealth uncomfortably, like the rumpled suits that had to be custom-made for his stocky frame. For most of the year, the “billionaire bachelor” lived in two modest rooms at the downtown Fort Worth Club. But he also owned a private island in the Gulf of Mexico, a twenty-eight-mile-long retreat he purchased for a million dollars and then adorned with a luxurious hunting lodge.26

The oilman was a collector of sorts. He had started purchasing pieces of art from the American West at an associate’s suggestion, soon amassing an unrivaled array of Remingtons and Russells. He also collected political clients. By 1951, he was already a generous backer of both Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn and Senator Lyndon B. Johnson. That year, he hired John Connally as his executive secretary, launching the career of another talented young politician. Believing Graham had similar potential, Richardson befriended the evangelist, introducing him to other leaders in the state and offering help whenever he could. Graham, for his part, adored the oilman, whom he always called “Mr. Sid.” When the preacher started his film production company, the first two features seemed to be tributes to Richardson, or men like him. Filmed during the Fort Worth crusade, Mr. Texas (1951) chronicled the conversion of a hard-drinking rodeo rider; Oiltown, U.S.A. (1954) told a similar tale about an oil tycoon from Houston who made his way to Christ. The second film cost $100,000 to produce and was advertised as “the story of the free-enterprise system of America, the story of the development and use of God-given natural resources by men who have built a great new empire.” Years later, when Richardson passed away, Billy Graham flew down to his private island to preside over the funeral. The preacher offered the highest praise he could imagine for his longtime patron: “He was willing to go to any end to see that our American way of life was maintained.”27

The earthy Richardson had little use for Graham’s religion, but the two shared a common faith in free enterprise. “When Graham speaks of ‘the American way of life,’” an early biographer noted, “he has in mind the same combination of economic and political freedom that the National Association of Manufacturers, the United States Chamber of Commerce, and the Wall Street Journal do when they use the phrase.” Indeed, during the early years of his ministry, Graham devoted himself to spreading the gospel of free enterprise. In his 1951 crusade in Greensboro, North Carolina, he spoke at length about the “dangers that face capitalistic America.” The nation was no longer “devoted to the individualism that made America great,” he warned the crowd. If it hoped to survive, it needed to embrace once again “the rugged individualism that Christ brought” to mankind. Not surprisingly, Graham saw that individualistic spirit in self-made millionaires such as Richardson and, therefore, made no apologies for ministering to him and men like him. “Whether the story of Christ is told in a huge stadium, across the desk of some powerful leader, or shared with a golfing companion,” the preacher reasoned, “it satisfies a common hunger.”28

Much like his patron, and much like Abraham Vereide and James Fifield, the preacher hungered to make his presence felt in Washington, D.C. His network of political contacts gave him easy access to the Capitol, where he led a congressional prayer service in April 1950. “Our Father, we give thee thanks for the greatest nation in the world,” he offered. “We thank thee for the highest standard of living in the world.” Although Graham was delighted to make new friends in the legislature, he had a bigger target. During the Boston crusade, he told a reporter that his real ambition was “to get President Truman’s ear for thirty minutes, to get a little help.” He peppered the president with letters and telegrams for months but had no luck winning an invitation until House majority leader John McCormack intervened. To Graham’s lasting embarrassment, their July 1950 meeting was an utter disaster. He and his three associates arrived at the Oval Office wearing brightly colored suits, hand-painted silk ties, and new white suede shoes. They looked, Graham remembered with a grimace, like a “traveling vaudeville team.” The president received them politely. A devout but reserved Baptist who was wary of public displays of piety, he held the foursome at some distance. When Graham asked if he could offer a prayer, Truman shrugged and said, “I don’t suppose it could do any harm.” The preacher wrapped his arm around the president, clutching him uncomfortably close. As he called down God’s blessing, an associate punctuated the prayer with cries of “Amen!” and “Tell it!”29

After their visit, reporters pressed Graham’s group to divulge details while a row of photographers shouted at them to kneel down for a photo on the White House lawn. To their later regret, they agreed to both requests. In sharing details with the press and posing for the picture, Graham had made a significant, if innocent, mistake. The president now viewed the preacher with suspicion, dismissing him as “one of those counterfeits” only interested in “getting his name in the paper.” Feeling used and furious as a result, Truman instructed his staff that Graham would never be welcome at the White House again as long as he was president, a decision leaked to the public by political columnist Drew Pearson. Graham continued to send unrequited letters to Truman, but he sensed that he had overstepped his bounds. “It began to dawn on me a few days later,” he wrote, “how we had abused the privilege of seeing the president. National coverage of our visit was definitely not to our advantage.”30

While Graham was dismayed at how the meeting went, Truman’s coldness toward him made it much easier for him to express his true feelings about the president. “Harry is doing the best he can,” he joked at one revival. “The trouble is that he just can’t do any better.” In a more serious tone, Graham soon ventured to criticize the administration from the pulpit. In January 1951, he warned that “the vultures are now encircling our debt-ridden inflationary economy with its fifteen-year record of deficit finance and with its staggering national debt, to close in for the kill.” He chided Democrats for wasting money on the welfare state at home and the Marshall Plan abroad. “The whole Western world is begging for more dollars,” he noted that fall, but “the barrel is almost empty. When it is empty—what then?” He insisted that the poor in other nations, like those in his own, needed no government assistance. “Their greatest need is not more money, food, or even medicine; it is Christ,” he said. “Give them the Gospel of love and grace first and they will clean themselves up, educate themselves, and better their economic conditions.”31

In January 1952, Graham returned to Washington, determined to make a better impression than he had two years before. This time, his team planned a five-week revival in the capital. The focus of the Washington crusade was a series of regular meetings at the National Guard Armory, but it also featured daily local broadcasts on both radio and television, weekly coast-to-coast broadcasts of his Hour of Decision TV show on Sunday nights, and a network of prayer services coordinated over the radio. Graham led prayer meetings all over town, including daily sessions in the Pentagon auditorium. On Monday mornings, he held “Pastor’s Workshops” with local clergymen; on Tuesdays, there were luncheons at the Hotel Statler to discuss religion with “the men who have so much a part in shaping the destiny of the Capital of Western Civilization: the business men of Washington.” Graham courted congressmen as well, of course. When he first announced the crusade, he did so with a senator and ten representatives standing alongside him. Abraham Vereide, who had helped conceive the Washington crusade and served on its executive committee, invited members of his congressional prayer breakfast groups to attend a special luncheon with Graham for “a discussion on ‘The Choice Before Us.’” Despite the rift between them, Graham hoped to convince President Truman to attend the first service and, if possible, offer some opening remarks. Truman steered clear. A staff memo noted the president “said very decisively that he did not wish to endorse Billy Graham’s Washington revival, and particularly, he said, he did not want to receive him at the White House. You remember what a show of himself Billy Graham made the last time he was here. The President does not want it repeated.”32

As the Washington crusade began in January 1952, Graham made clear his intent to influence national politics. If Congress and the White House “would take the lead in a spiritual and moral awakening,” he said, “it would affect the country more than anything in a long time.” Those who supported the revival were given cards to place in their Bibles, reminding them to pray daily “for the message of [the] Crusade to reach into every Government office, that many in Government will be won for Christ.” Although the president remained aloof, many congressmen embraced Graham. Virginia senator A. Willis Robertson secured unanimous Senate approval of the crusade, as well as a prayer that “God may guide and protect our nation and preserve the peace of the world.” Several congressmen took roles in the revival, including four who regularly served as ushers. Many more attended, with roughly one-third of all senators and one-fourth of all representatives requesting special allotments of seats to the Armory services. “As near as I can tell,” Graham bragged to a reporter, “we averaged between 25 and 40 Congressmen and about five Senators a night.” Congressional attendance was noteworthy, but so too was the overall turnout. Despite the Armory’s official seating capacity of 5,310, more than 13,000 people packed the venue on opening night, with crowds exceeding 7,000 allowed on subsequent evenings. Even with such limitations, the total attendance for the Washington crusade ultimately reached a half million. As Vice President Alben Barkley marveled to Graham, “You’re certainly rockin’ the old Capitol.”33

Interest proved to be so high that Graham soon staged a huge rally at the Capitol itself. At first, the idea seemed impossible. But a call to his patron Sid Richardson—who, in turn, called Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn—prompted Congress to push through a special measure authorizing the first religious service ever to be held on the steps of the Capitol Building. “This country needs a revival,” Rayburn explained, “and I believe Billy Graham is bringing it to us.” Even though it took place in a cold drizzling rain, the February service drew a crowd estimated to be as large as forty-five thousand. (The gathering, the House sergeant at arms noted, was larger than the one for Truman’s inauguration.) Graham reveled in the turnout, taking off his tan coat to address them in a powder-blue double-breasted suit with a polka-dot tie. To those assembled, and to the millions more listening over the ABC radio network, he called for Congress to set aside a national day of prayer as a “day of confession of sin, humiliation, repentance, and turning to God at this hour.” The minister noted that a formal return to God would benefit not just the American people but also the political representatives who had the faith to make such a cause their own. “If I would run for President of the United States today on a platform of calling people back to God, back to Christ, back to the Bible, I’d be elected,” Graham insisted. “There is a hunger for God today.”34

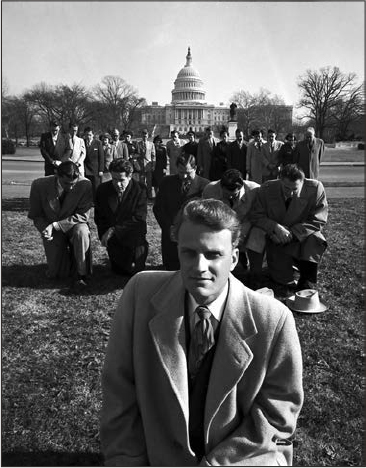

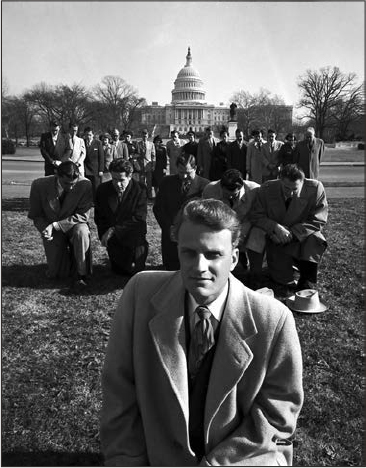

In January 1952, Reverend Billy Graham launched the Washington crusade, staging religious revivals at the National Armory and, in a first for the city, on the steps of the Capitol Building itself. If Congress and the White House “would take the lead in a spiritual and moral awakening,” he said, “it would affect the country more than anything in a long time.” Mark Kauffman, The LIFE Premium Collection, Getty Images.

The proposal for a national day of prayer was nothing new; several presidents, including Abraham Lincoln, had called for similar religious observances in the past. Graham himself had tried to convince Truman of the need for a national day of prayer during their July 1950 meeting. The idea generated considerable interest at the time, as ministers across the nation picked up Graham’s proposal and urged Americans, in sermons delivered in their own churches and over the radio, to lobby the president. Thousands did. “The minds of the people must be directed more toward spiritual values,” a Cincinnati woman wrote. “The time is NOW for spiritual mobilization.”35 Despite the outpouring of public pressure, Truman had not been swayed. The second time around, however, the president gave in. He still had reservations about public displays of prayer—in his diary that month, he noted that he abided by “the V, VI, & VIIth chapters of the Gospel according to St. Matthew,” which were often cited for their injunctions against the practice—but he read the national mood and decided to acquiesce.36 As Congress took up the proposal in February 1952, House majority leader John McCormack let it be known that Truman now supported the plan.37

Congress resolved, by the unanimous consent of both House and Senate, “that the President shall set aside and proclaim a day each year, other than a Sunday, as a National Day of Prayer, on which the people of the United States may turn to God in prayer and meditation.” The language of the legislation was significant, as all previous congressional proclamations for days of prayer “requested” that the president designate a day, while this one alone “required” him to do so. Truman was thus bound by the law, just as every one of his successors in the White House has been to this day. In an apparent nod to the previous year’s “Freedom Under God” observance, which was set to be repeated in 1952, Truman selected the Fourth of July as the date for the first National Day of Prayer. The choice, he explained, was intended to coincide “with the anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, which published to the world this Nation’s ‘firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence.’” In the official proclamation, Truman encouraged all Americans to ask God for strength and wisdom and to offer thanks in return “for His constant watchfulness over us in every hour of national prosperity and national peril.” For his own part, the president observed the day of prayer by taking in a doubleheader between the Washington Senators and the New York Yankees. His critics noted with satisfaction that the Yankees beat the home team in both games and that Truman had to leave early when the second was called on account of rain.38

While Billy Graham welcomed the adoption of the National Day of Prayer, he saw it as merely the beginning of the political and moral transformation needed to save the nation. In late 1951, he insisted that “the Christian people of America will not sit idly by during the 1952 presidential campaign. [They] are going to vote as a bloc for the man with the strongest moral and spiritual platform, regardless of his views on other matters.” By that time, Graham believed he had already found the man who fit the description: General Dwight D. Eisenhower.39

EISENHOWER SEEMED AN UNLIKELY CANDIDATE to lead the nation to spiritual reawakening. For decades he had remained distant from religion and could not even claim a specific denominational affiliation. During his childhood, however, his family had been deeply devout. His grandfather had been a minister for the River Brethren, an offshoot of the Mennonites, and his father maintained that faith. His mother traveled a more circuitous spiritual path: born and raised a Lutheran, she joined the River Brethren at marriage but was later baptized as a Jehovah’s Witness when Dwight was eight years old. While denominations may have varied, the family’s commitment to a literal reading of the Bible remained constant, and a constant presence in their lives. In their white clapboard home in Abilene, Kansas, the Bible was a source of inspiration read each morning in prayers and a source of authority to be quoted again and again. “All the Eisenhowers,” one of Dwight’s brothers later explained, “are fundamentalists.”40

Dwight Eisenhower certainly bore the imprint of this upbringing—he had been named after Dwight Moody, a popular nineteenth-century evangelist who was, in essence, a forerunner of Billy Graham—but for much of his adult life he showed little of it publicly. The River Brethren required strict observance of the Sabbath, but Eisenhower rarely attended services during his military career. The Brethren demanded abstinence from tobacco, but he became a heavy smoker, going through four packs of Camels a day during the climax of the Second World War. The Brethren were also strongly committed to pacifism on religious grounds; Eisenhower’s mother condemned war as “the devil’s business” and believed those waging it were sinners. While most members of the River Brethren and the Witnesses sought to secure a conscientious-objector exemption from military service during times of war, Eisenhower actively pursued a military career during a time of peace, leaving home in 1911 to enroll at West Point and then rising through the ranks over the course of two global conflicts.41

In spite of his outward indifference to the faith of his family, Eisenhower insisted that its lessons still resonated with him. “While my brothers and I have always been a little bit ‘non-conformist’ in the business of actual membership of a particular sect or denomination,” he wrote a friend in 1952, “we are all very earnestly and very seriously religious. We could not help being so considering our upbringing.” Indeed, while he lacked ties to any specific denomination, Eisenhower remained firmly committed to the Bible itself. Like his parents, he considered it an unparalleled resource. One of his aides during the Second World War remembered that Eisenhower could “quote Scripture by the yard,” using it to punctuate points made at staff meetings. After the war, his sense of religion’s importance only grew stronger. In an interview before he assumed the presidency of Columbia University in 1948, Eisenhower declared himself “the most intensely religious man I know.” Faith, he believed, was important not just for him personally but also for the entire country. “A democracy cannot exist without a religious base,” he told reporters. “I believe in democracy.”42

Comments such as these led Billy Graham—and many other Americans—to believe that their democracy needed Dwight Eisenhower. In a letter to Sid Richardson in late 1951, Graham wrote that “the American people have come to the point where they want a man with honesty, integrity, and spiritual power. I believe the General has it. I hope you can persuade him to put his hat in the ring.” Richardson had been friendly with Eisenhower since just after the attack on Pearl Harbor, when they met by chance on a train trip through Texas. He urged Graham to “write General Eisenhower some good reasons why he ought to run for the presidency.” “Mr. Sid, I can’t get involved in politics,” Graham demurred. But his patron was set on the idea. “There’s no politics,” he insisted. “Don’t you think any American ought to run if millions of people want him to?” When Graham replied, “Yes, Mr. Sid, I agree he should—” the oilman cut him off with a brusque “Well, then, say that in a letter!” Doing as instructed, the minister exhorted Eisenhower to run. During the crusade in the capital, Graham related, a district court judge had “confided in me that if Washington were not cleaned out in the next two or three years, we were going to enter a period of chaos or downfall.” The stakes were high. “Upon this decision,” he concluded, “could well rest the destiny of the Western World.” Eisenhower told Richardson that it was “the damnedest letter I ever got. Who is this young fellow?”43

Richardson arranged for the two to meet, sending Graham to the general’s offices in Paris shortly after the Washington crusade. Eisenhower made a powerful impression on the preacher. “Although he was in uniform,” Graham later remembered, “his office looked like that of a corporate executive, with walnut-paneled walls, a walnut desk, and green carpeting to match his chair.” The two began talking about their mutual friend, but much of the two-hour meeting served as a chance for Graham to make his case for an Eisenhower candidacy. The minister would later downplay the importance of his visit in the ultimate decision, aware that other Americans—including a congressional delegation led by Senator Frank Carlson of Kansas, a close ally of Abraham Vereide—had likewise made the pilgrimage to Paris. But Graham’s spiritual support was surely influential in the general’s decision, as was the financial support Richardson promised. Once Eisenhower announced his intentions, the oilman put his vast fortune to work for him. Richardson’s direct contribution to the campaign was reportedly $1 million, but he also paid for roughly $200,000 in expenses at the Commodore Hotel in New York, where the general had established offices after returning home, and then covered most of his expenditures during the Republican National Convention in Chicago as well.44

In June 1952, Eisenhower launched his campaign for the presidency in Abilene. The town staged a massive parade in his honor, with a series of floats depicting events in his life, ending with one carrying a replica of the White House with him inside. His parents had long since passed away, but the candidate made an appearance at their old clapboard home, using it as a shorthand for his humble upbringing, his family, and his faith. In his comments, he condemned a set of “evils which can ultimately throttle free government,” which he identified as labor unrest, runaway inflation, “excessive taxation,” and the “ceaseless expansion” of the federal government. These were commonplace conservative positions, but Eisenhower presented them in religious language that elevated them for his audience. Scotty Reston of the New York Times was reminded of William Jennings Bryan, the great evangelist for old-time religion and plain-folks politics. “He appealed to the virtues of a simpler era that this town symbolizes,” Reston wrote. “He appealed not to the mind but to the heart, and his language was filled with the noble words of the old revivalists: frugality, austerity, honesty, economy, simplicity, integrity.” Referring to Eisenhower’s memoirs of the war, the journalist noted, “His ‘Crusade in Europe’ over, he opened up a second front here as if he intended to start a second crusade in America.”45

Eisenhower encouraged the perception that his candidacy was a religious cause. In his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention, he declared the coming presidential campaign to be “a great crusade for freedom in America and freedom in the world.” He appropriated not only Graham’s “crusade” brand but also Graham himself. Shortly after Eisenhower secured the nomination in July 1952, the preacher received an urgent call from Senator Carlson, whom he had met months earlier during the Washington crusade, asking him to come to Eisenhower’s hotel in Chicago. There the candidate asked if Graham might be able to “contribute a religious note” to some of his speeches for the election season. “Of course, I want to do anything I can for you,” Graham agreed, with the caveat that “I have to be careful not to publicly disclose my preferences or become embroiled in partisan politics.” Soon after, the minister spent a few days with the campaign staff at the Brown Palace Hotel in Denver, offering scriptural references and spiritual observations that could be used to sanctify the secular positions of the candidate. Before leaving, Graham gave Eisenhower a gift of a silk-sewn red-leather Bible—red because, as one of his associates liked to joke, “a Bible should be read”—which the preacher had painstakingly annotated with his interpretations. Eisenhower treasured the gift, keeping it close at hand during the campaign and placing it on his bedside table at the White House. He seemed to value sincerely Graham’s advice, but he also understood the political benefit of his public association with the popular preacher. In a letter to Governor Arthur Langlie, who had been propelled to prominence in large part by Vereide’s breakfast groups and had served as cochairman of Graham’s 1951 Seattle crusade, Eisenhower noted with delight that the minister had praised the Republican “crusade for honesty in government” before his radio audience of millions. But Eisenhower wanted more if possible. “Since all pastors must necessarily take a nonpartisan approach,” he acknowledged, “it would be difficult to form any formal organization of religious leaders to work on our behalf. However, this might be done in an informal way.”46

While Graham insisted he could never reveal his political leanings, he spent much of the campaign dropping what seemed to be considerable hints. On domestic matters, Graham had long been sounding Republican themes of rolling back the welfare state and liberating business leaders to operate on their own. But on foreign policy too, Graham closely followed the Republican script for those issues, summed up by South Dakota senator Karl Mundt as the “K1C2” formula for its component elements of “Korea, communism, and corruption.” “The Korean War is being fought,” he told a Houston congregation in May, “because the nation’s leaders blundered on foreign policy in the Far East.” He called the Truman administration “cowardly” for not following the advice of General Douglas MacArthur and pursuing “this half-hearted war” rather than unleashing the full powers of the American military. On domestic issues, meanwhile, Graham condemned the “tranquil attitude to communism” in the country, warning that “Communists and left-wingers” posed a danger to the nation and that there already might be “a fifth column in our midst.” As for corruption, Graham pressed the issue early and often, so much so that his comments became indistinguishable from the official Republican slogans. The GOP insisted, “We must clean up the mess in Washington”; at the same time, Graham asserted, “We all seem to agree there’s a mess in Washington.” Time and time again, the preacher made a clear political attack from the pulpit, only to walk it back slightly with a shrug and a smile. Once, for example, he made a disparaging comment about Truman, only to cut himself short: “I won’t say anything more about that. Except,” he immediately added, “that I have found that after my car has run for a long time, it needs a change of oil. That’s the strongest political statement I’m going to make, now.”47

Though the Eisenhower campaign made use of Graham as much as possible, the campaign of his Democratic rival, Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson, refused to conduct religious outreach of its own. There were plenty of opportunities. In 1951, a group of leading clergymen formed Christian Action, which intended “to draw together Protestants on the non-communist left for the implementation of the implications of the Gospel in social, economic, and political affairs.”48 It was, in essence, a liberal counterpart to James Fifield’s Spiritual Mobilization. The theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, who frequently traded barbs with Fifield in the press, served as one of its two national cochairmen.49 In a response to Graham’s involvement in the Eisenhower campaign, Niebuhr suggested that Christian Action could counter his work by assembling “an inter-faith committee of ministers for Stevenson.” The group lined up 124 Protestant religious leaders and drafted a statement announcing their support for Stevenson as the candidate who could best lead “the free world in resisting the dread peril of communism.” The Stevenson campaign was divided on the proposal, but ultimately chose not to pursue it due to fears of a negative reaction in the press. Billy Graham had no such reservations. A few days before the election, he announced that he had conducted his own personal survey of 220 religious editors and clergymen and found that they favored Eisenhower over Stevenson by an overwhelming margin of six to one. Graham still insisted that, personally, he was neutral in the race. “I believe, however, it is the duty of everyone who calls himself a Christian to go to the polls and vote,” he asserted. “Every Christian should be in much prayer that God will have his way.”50

While Graham’s support was influential, Eisenhower’s campaign received similar endorsements from other Christian libertarian leaders. During the Republican National Convention in Chicago, for instance, Vereide’s International Council for Christian Leadership held a special breakfast meeting for nearly a hundred convention delegates at the Board of Trade Building. They prayed for the success of the Republican convention and, moreover, “for God’s man to be elected this fall, praying that America may become aroused and led by God in the coming election and that God’s grace and power may rest upon our country, preparing it for service at home and abroad as a nation under God.” In September 1952, Vereide sent a mass mailing to his national network of more than two hundred breakfast groups. He urged the members of the business and civic elite who participated to devote all their energies to the cause of raising “alertness to the right choice and vote in the November elections.”51

Likewise, Spiritual Mobilization’s Faith and Freedom published a manifesto, titled “The Christian’s Political Responsibility,” in its September 1952 issue. Advancing arguments that would later be made by the religious right, the magazine sought to convince Christian voters that they had a duty to bring their religious convictions to bear in the ballot box. “The Christian may keep aloof from politics because it is ‘dirty,’” the magazine’s editor observed. “In that event, he may be sure the non-Christian cynic will take full advantage of his apathy. Politics will then be ‘played’ not according to the principles of Christ, but according to the principles of the anti-Christ. This is precisely what happened in our country to an extent that has shaken the foundations of our Republic. Action must be taken, and now.” Faith and Freedom followed the lead of Graham and Vereide, claiming it would never endorse one party or the other. But it offered a “political checklist for Christians” that nudged readers rather strongly toward the Republicans. When considering the Christian merits of a particular candidate, party, or law, the editor noted, readers should ask themselves a series of questions: “If it proposes to take the property or income of some for the special benefit of others, does it violate the Commandment: ‘Thou shalt not steal’? If it appeals to the voting power of special interest groups, or to those who have less than others, does it violate the Commandment: ‘Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house’?” As Spiritual Mobilization made the case for Eisenhower, others noted the connections between them as well. “America isn’t just a land of the free in Eisenhower’s conception,” journalist John Temple Graves observed that same month. “It is a land of freedom under God.”52

In the end, Eisenhower’s “great crusade” for the presidency proved to be every bit as popular as Graham’s own crusades. He took more than 55 percent of the popular vote, with even more impressive margins in the Electoral College, where he won 442 to 89. Stevenson only managed to win nine states, all in the still solidly Democratic South, but even there Eisenhower made historic inroads by taking Texas, Tennessee, Virginia, and Florida. Outside the region, he won every single state west of Arkansas and virtually every state north of it, including his opponent’s home state, Illinois. “Earthquake, landslide, tidal wave,” marveled Marquis Childs in the Washington Post, “whatever it was it worked with the overpowering completeness resembling a natural force.” The famous columnist Walter Lippmann agreed, asserting that the president-elect’s “mandate from the people is one of the greatest given in modern times.”53

Reflecting on the election returns, Eisenhower resolved to put that mandate in the service of a national religious revival. He asked Graham to meet with him in the suite Sid Richardson had provided at the Commodore Hotel in New York, to discuss plans for his inauguration and beyond. “I think one of the reasons I was elected was to help lead this country spiritually,” the president-elect confided. “We need a spiritual renewal.” Graham, moved nearly to tears, responded with an excited exclamation: “General, you can do more to inspire the American people to a more spiritual way of life than any other man alive!” For the next eight years, Eisenhower would attempt to do precisely that. Working with Graham, Vereide, and countless others both inside and outside his administration, the new president endeavored to lead the nation back to what he understood to be its religious roots. In doing so, however, he would actually transform America into something altogether new.54